6. Wife of Jack

©2024 Barbara Fisher, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0377.06

I can see Trix, dressed in her most modest but still softly pretty clothes, sitting in the dimly lit Fleming drawing room. As the cold Edinburgh rain falls steadily outside, she tries to make herself comfortable on her hard chair. This is her first introduction to the Fleming family. She had been warned that the Flemings were serious and severe, but she hoped to charm them. Despite the Flemings’ cool greetings and prim postures, Trix chatters on about her recent rough voyage from India. Her descriptions of the roiling seas, the rocking ship, and the retching passengers are met with discouraging silences and barely polite nods. The dour and stiff Flemings in their dull tweeds and sensible brogues assess Trix’s brightly coloured clothes and her many necklaces and are confirmed in their earlier long-distance judgment of her as a vain, silly Bohemian. They know she has the habit of scribbling stuff and publishing it, and they find no delight in her clever remarks, sprinkled, as usual, with quotations. To the stolid and unsmiling Flemings, Trix seems frivolous and flighty, interested in poetry, drama, and other useless things, for which they have only disdain. Trix is surprised and hurt by this cool reception. She is used to being liked, even admired, and feels that she is failing with her in-laws. Even worse, she begins to recognize that she will always fail, that the Flemings will always judge her harshly. Jack offers her little comfort or reassurance.

Fig. 18 Trix (far right) and Jack (far left) early in their marriage.

When Trix and Jack had arrived in England four days earlier, on 10 February 1890, their marriage, just eight months old, was already tense and troubled. Jack was ill, uncomfortable, and full of complaint. Trix was vexed that the fever he had developed in Burma hung on so persistently. She knew it was her job to get Jack speedily to Edinburgh where he could be looked after by his family, but she longed to stay in London to spend a little time with Rudyard, who was now living there.

The day after she arrived in London, Trix insisted that she pay a visit to Rudyard at his Embankment chambers. When she arrived at his modest apartment, she was shocked to find him miserably depressed. He was suffering from the gloom of the London winter but also from the end of his short-lived engagement to Carrie Taylor. He poured out his sorrows to Trix, but she kept her troubles to herself. Had his spirits been better, she might have shared her sorrows, but Rudyard seemed barely able to carry his own load of grief. Trix begged Jack to allow her to remain with Rudyard in London a few days longer, but Jack was determined to reach Scotland as soon as possible. After just four days in London, Jack and Trix proceeded to his family’s home in Edinburgh. There, on 14 February, Trix had her first encounter with the Fleming family.

Two days after her initial appearance in the Fleming drawing room, on another damp, raw, drizzling Edinburgh day, Trix walked to church with the family. As she sat in the dim, high-vaulted space, surrounded by unsympathetic and uncongenial Flemings, she considered how foreign this family was, how different they were from her own eccentric, artistic, and dramatic people. At the end of the service, as she tried to rise, she felt light-headed and dizzy. Suddenly, her strength gave way, and she fell to the ground. Faint and frightened, she was helped to her feet, led from the church, and carried home. Two days with the Flemings had literally brought her to her knees.

Fig. 19 Photograph of Trix early in her marriage to Jack.

Fig. 20 Photograph of Trix early in her marriage to Jack.

After her collapse in church, she rallied. She was determined to carry on as was required. She attended dinner parties, viewed the International Exhibition of Science, Art and Industry in Edinburgh, travelled to Aberdeen, and accompanied Jack on his many golfing trips. While in Edinburgh, which she soon likened to ‘a beautiful woman with a bad temper’,1 she made a few more attempts to impress the dull Flemings. Staying with Jack’s family, she longed to be with her own extraordinary relatives—the Macdonald sisters, Burne-Joneses, Poynters, and Baldwins—in Southern England, or with Rudyard in London. When she was given leave to visit her family, she worried she was neglecting and possibly offending Jack’s people. Pulled in opposite directions, she was comfortable nowhere. Struggling just to stay on her feet, she had no time or space to write, or even to think about writing.

Fig. 21 Photograph of Trix early in her marriage to Jack.

Fig. 22 Photograph of Trix early in her marriage to Jack.

Despite Jack’s discouragement and displeasure, Trix travelled alone to London in May to be with her unhappy brother. He had been so depressed that he had asked his parents for help, and they had made the long trip from Lahore to London in response to his extraordinary call. With Trix’s arrival, the Family Square was briefly reunited. Rudyard’s fame, newly but firmly established, had worn him down. Having recovered from his broken engagement, he had been flirting again with his first love, Flo Garrard, who had, by chance, appeared on the scene. The affair with Flo, like the engagement to Caroline Taylor, had ended badly. With so many disappointments, Rudyard was grateful to have his family around him. Although anxious about herself, Trix was happy to be with her family and to be, even for a few weeks, a part of the old Family Square.

She continued to keep her own worries to herself. She did not want to burden her parents, already concerned about Rudyard, with her own distress. Embarrassed and ashamed, she did not want to tell them of her growing discontent with Jack. She was grateful to be mercifully removed from her husband, who was irritating her more and more. She and Jack were already quarrelling and having frequent ‘royal rows’.2

After less than a month in London, Trix returned to Scotland to be with Jack on their first anniversary, her twenty-second birthday, 11 June. While Jack pursued his passion for golf at St. Andrew’s and other courses, Trix tagged along. Despite bad weather, he often played two rounds a day. And despite all the exercise and fresh air, he slept badly and was often ill. Trix did not feel well either and had a second dramatic fainting spell in church. Both frequently took to their beds with colds, flu, and other complaints. When Jack and Trix made a trip to York, they fought so bitterly that they visited the York Minster separately. By this time, their fighting had become a habit. Trix reported that they were ‘fighting as usual’,3 as if it were a regular part of the marriage, just one year on.

In the spring of 1891, hoping to find some relief from their continuing health problems, Trix and Jack travelled to Europe, to spas in Nuremberg and Carlsbad. They consulted doctors, took the waters, and went for long walks, but they improved little. In the end, they concluded that the waters were useless. In the autumn of 1891, Trix returned to London and had some time to be with her parents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, followed by a few days’ visit with the Baldwins at Wilden. But soon she was required to go to Scotland and spent the new year 1892 visiting Jack’s sister Moona Richardson at Gattonside House in Melrose, a small town in the Scottish Borders. Moving from the intellectual excitement of her own family in London to the dull world of the Flemings in small-town Scotland, Trix once again measured the vast gulf between her family and his.

After one year with Jack, Trix had few illusions about her marriage. She and Jack had incompatible and unalterable temperaments. Jack was naturally self-contained, undemonstrative, often dour, while Trix was extroverted and effusive. Trix, who spoke with speed and verve, became more and more annoyed by her husband’s slow, monotonous voice, which often made her clasp her hands together in silent, intense irritation. Trix had married Jack to make him happy, and she wanted assurances from him that his happiness was now complete. But it seemed to her that marriage had made very little difference to him. In fact, he had been ill and ailing almost from the start. And her feelings, which had always been cool, had not grown warmer, as Jack had promised they would. She had initially been attracted to Jack’s reassuring solidity and certainty, but she now recognized his strength as rigidity and withdrawal. Similarly, Jack, who had married Trix to bring spirit and sparkle into his life, soon recognized that his wife’s constant chatter and nervous energy annoyed and agitated him. They had both discovered that the traits that had initially attracted them to each other were exactly the traits that now most irritated and repelled them. The marriage, which was meant to provide support, if not love or passion, failed even at that.

In 1892, Rudyard married Caroline Balestier, a wife displeasing to Trix as well as the Kipling parents. Caroline, always called Carrie, was, in the most negative assessment, hard, bossy, interfering, and opinionated. From a more positive point of view, she appeared forceful, intense, and courageous. Rudyard had been an extremely close companion and collaborator with her charming brother Wolcott, who had come from America to London with bold literary ambitions. Rudyard’s friendship with Wolcott lasted only a few years. Wolcott died suddenly of typhoid at the age of thirty. At Wolcott’s death, Rudyard was impressed by Carrie, who competently took charge of his affairs. Although Rudyard was uncertain about Carrie and unready for marriage, he proposed to her very shortly after Wolcott’s untimely death.

Soon after meeting Carrie, Alice recognized her forceful character and her decided intentions towards Rudyard. She immediately and unhappily sensed that Carrie was going to hustle Rudyard into marriage and that the Balastiers were going to replace the Family Square and become Rudyard’s chosen intimates. She was fully justified in her fears, as Rudyard precipitously married Carrie and moved with her to the Balastier family home in Brattleboro, Vermont.

The first two years of Trix’s marriage were not ideal—a rushed honeymoon followed by an unexpected separation and darkened by Jack’s steep and sudden decline from good health to illness. Traveling to meet the Flemings in Scotland, then to spas on the continent to regain their health, they were almost constantly on the move.4 Trix had had no chance to be a proper wife, run a household, or establish a routine. She also had had no privacy or leisure to write.

Then, in early 1892, after almost two years of home leave in England, Scotland, and on the continent, Trix and Jack returned to India to begin their married life together. Trix was ready to start again as the new bride of an officer under the Raj. She knew the requirements and restrictions of this position. She had been brought up to respect the rules of class, caste, precedence, and power and to love, cherish, and obey her husband.

Home was Calcutta, the capital as well as the commercial and industrial centre of India.

Jack was stationed here in his position with the Great Survey. The sprawling, busy city was crammed with an endless, ceaseless stream of people, causing a constant bustle and din. Warehouses, factories, and offices lined the docks on one side of the Hooghly River, while, on the banks of the other side, the wide lawns of grand mansions sloped down to the river’s edge. Monumental buildings of various designs—Grecian, Indo-Gothic, Italian, Egyptian, Turkish—with columns, cupolas, and domes sprang up in unlikely profusion in the sky above the city. The centre of the city was a jumble of wide avenues, dingy lanes, rows of dark shops and offices, stalls selling garlands of flowers, woven baskets, pottery images of the gods, small gated temples, open pumps with crowds washing, and always beggars clambering and pleading.

Used to the relative calm of Lahore, Trix was unprepared for the noise, stench, heat, dust, and squalor of the city. But she was rarely required to visit the poorest, shabbiest, and dingiest parts of the city, as she and Jack lived in the well-ordered ‘White Town’, where the streets were set out on a regular grid. Here, the spacious bungalows of the British were set apart from the dilapidated shacks and huts of the Indians. The British lived in large houses surrounded by expansive lawns and elaborate gardens, decorated with potted plants, and perfumed with jasmine. Nearby were the beautiful, lushly planted Eden Gardens, where Trix walked in the leafy shade to avoid the mid-day heat. In the evening, she and Jack strolled on the Strand beside the beautiful Hooghly River, where brass bands often played.

Trix was familiar with the Indian climate and the British seasonal changes of residence. In April, following the usual pattern, Trix often visited Lahore. From May to November, she retreated from the heat to the hill stations of Mussoorie or Simla. In the cool weather she resided in Calcutta, her primary residence.

After two years of marriage, Trix finally had the responsibility of setting up and running a household. She had wanted to take on these wifely duties for a long time and undertook them with enthusiasm—choosing furniture, fabrics, and paint colours. Although she was not responsible for cooking or cleaning, she busied herself with minor household chores—mending, tidying, and folding and airing the clothes, cushions, and napkins. She wanted to show Jack that she could make things neat and comfortable. Jack was very particular about his surroundings and had an eagle eye for the details of both décor and dress. Trix was pleased that Jack took an interest in the order of the house and the smartness of her dress, but it took time and trouble to keep up to his mark.

Although Trix understood the complicated caste system, she had never before had to operate in it as a memsahib, literally ‘the master’s woman’. The Indian caste system, more complicated even than the British class system, organized her interactions with Indians—mistress to servants. The simple household machinery was run by a multitude of servants—to cook, to clean, to wait at table, to attend to ladies’ dress, hair, and toilette. Like most of the English memsahibs, Trix expected her servants to understand and adjust to English ways without herself adjusting to Indian manners and habits. She learned to speak some small bits of their language in order to have her household run smoothly.

Occasionally, Trix ventured into the bustling open markets, where she shopped among a profusion of stalls selling an eccentric assortment goods—cotton, silks, jewels, slippers, necklaces, and spices. Shop after shop displayed brightly coloured saris, hanging like banners. Trix was never comfortable among the running porters, pushing crowds, and beggars with crutches, bandages, and missing limbs and eyes. Scrawny dogs with open sores, chickens, goats, and buffaloes made it dangerous to walk from stall to stall. She feared losing her way among the jumble of bicycles, rickshaws, oxcarts, and carriages. Filthy piles of bundles and baskets impeded her steps. On most days, Trix stayed home and sent her servants to the closed Hogg Market to buy supplies for the house. She became a clever hostess, improvising meals and entertainments for the unexpected guests Jack often brought home. When she was not obliged to host parties, she attended with good grace and good cheer an endless round of garden, tea, tennis, and dinner parties.

This domestic routine was interrupted by long trips to the jungle, where Jack was required to go for his work on the Survey. Trix accompanied him and stayed in several jungle camps for months at a time. Sleeping under a canvas tent, she found camp life mostly delightful. The conditions were hardly primitive. There were cane chairs, tables with starched cloths, silver and china, makeshift chests and dressing tables, and always an abundance of servants to cook, clean, set up, and replenish stores of food. In camp, Trix was happy to be excused from attending social events and from maintaining the house up to Jack’s standards. In the early mornings, she took horseback rides through the lush green mango groves. She relaxed under the stars in the beautiful cool of the evenings. During the many idle hours of the day, when Jack was occupied with his surveying duties, Trix had uninterrupted leisure. At last, Trix was able to resume her writing. She had the time, the privacy, and the energy. She did not attempt another novel but returned with spirit and verve to short, mostly satiric pieces.

During one long period in camp, Trix produced a series of dialogues, which were published anonymously in The Pioneer, the Allahabad-based sister paper to The Civil and Military Gazette. These brief sketches, which ran from April to December 1892, while never attributed to Trix, unmistakably bear her mark.5 Trix’s collected unpublished writings include a series of strikingly similar dialogues (written years later) featuring a married couple named George and Mabel.6 That unpublished series and these sketches for The Pioneer present marriage as a comedy of miscommunication between a mismatched husband and wife. The Pioneer pieces are signed alternately John Brown and Mrs John Brown, obvious pen names.

In the first piece, titled ‘Wife in Office’ and published on 28 April 1892, a husband complains of his wife having invaded his office. She defends herself with stubborn self-righteousness. They are an evenly matched pair of selfish whiners.

In the second, titled ‘My Sister-in-law’s Alarms’ and published on 12 May 1892, signed by John Brown, the put-upon husband complains again—this time about a visit from his sister-in-law, who is a nervous, selfish, disagreeable guest. John’s wife naturally defends her sister. (Mrs Brown is named Winnie, the name Trix used later for the heroine of her novel A Pinchbeck Goddess.)

The third in the series, published on 19 May 1892, is signed by Mrs John Brown and is titled ‘Mrs John Brown Protests’. The title accurately describes the intention, but the effect is self-serving carping and complaining. Mrs Brown reveals herself to be as silly as her husband has portrayed her.

The fourth, ‘Hunter on Marriage’, published on 22 June 1892, contains more marital friction and fault-finding. In the fifth, ‘My Aunt-in-Law’s House’, published on 7 September 1892, John dutifully agrees with every foolish thing Aunt Hetty says about her house. The sixth, ‘Casual Leave’, published on 27 October 1892, describes a shopping spree where a long-suffering husband accompanies his wife as she buys a dress, gloves, and hat. The seventh, ‘The Judge’s Whist’, published on 24 November 1892, ends with the teaser ‘but that, as Kipling says, is another story’. It catalogues the annoying habits of a card player. The last of the series, published on 1 December 1892, ‘In Shadowy Thoroughfares of Thought’, is a dialogue in which Mrs Brown continually interrupts her husband. He is, as usual, long-suffering and silent. She is insufferable and unstoppable.

All of the dialogues begin with a literary quotation, and most are dotted throughout with many more—from Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson, and Rabelais. Constant quotation was Trix’s hallmark, in writing and speech.

Also signed by John Brown is ‘Our Own Correspondent’, published on 2 January 1892. In this essay, Mr Brown gives a lesson in how to write boring clichés. He recommends reporting at length on the weather and on the most trivial local doings. He remarks that only the author bothers to read the ‘turn-overs’. These short pieces were the continuation of a story begun at the front of the paper. ‘Plain Tales from the Hills’, written by Rudyard and Trix five years earlier, were the most popular and best known turn-overs published and read by the British in India. Thus, this is a reverse compliment and an inside joke from Trix to Rudyard.

John Brown also signed a piece titled ‘In the Blues’ (published on 7 May 1892), where he, as an undersecretary, describes in tedious detail the need for systematically colour-coding files.

These pieces, like many in The Pioneer, appeared anonymously. They have never been positively attributed to Trix, but the Winnie and John Brown exchanges sound very much like Trix’s later George and Mabel dialogues, and they bear Trix’s signature use—perhaps overuse—of quotation. In all of them, the speaker or writer damns him or herself with his or her own words. Trix was especially adept in the use of this narrative device.

The Flemings had been married three years when these pieces appeared, enough time for Trix to know well the shape and sound of marital discord. She had also had enough time and enough art to transform spousal disagreement, dissatisfaction, and resignation into a brilliant comic routine. She easily mimicked both parts—the silly jabbering wife and the silent suffering husband. With great exuberance and confidence, Trix turned her possibly tragic marriage into delicious, dark comedy.

Trix did publish one story under her own name, a short and slight tragic love story titled ‘At a Christmas Ball’, in the Christmas edition of Black and White in December 1892.7 At a club ball, a handsome artillery officer promises a fair, pretty girl that he will return in a year to claim three dances from her. She waits longingly for his return but learns, after six months, that he has died of cholera. When she sadly attends the next annual club ball, she sees his ghost… perhaps.

Although Trix was productive and content in camp for a while, after months of living in tents at Purunpur, she longed to return to Calcutta to get her house put to rights. She dreamed of curtains and cushions and all the little details of framing pictures, hemming napkins, and shining silver. Returning to Calcutta meant returning to social life with Jack’s fellow officers and their often new, young wives. Trix, by now, had accepted her role as social hostess and guest, and had learned to accommodate herself to the company of silly, simpering women.

Trix was not like these women who became the wives of army officers under the Raj. The young women who went to India to seek or meet a husband, in what were called ‘fishing fleets’, were not the best-educated or best-connected girls. If they could have, they would have married men back home in England. Conventional behaviour was expected of them. They had been educated to be proper wives of the most desirable men they could attract. They practiced on the piano, rode, and played golf and tennis. They could make up a fourth hand at bridge. Sewing and sketching were their preferred hobbies. Drawing or flower arranging were acceptable enthusiasms. They could dance and make superficial conversation at parties. They were educated but decidedly not overeducated.

They were taught to remain British, not to let down the race, the Raj, or the British Empire. The worst bad form was ‘going native’, knowing or caring too much about India.

Encouraged to ignore India, cling to the ideas of home, and establish a community that reminded them of what was familiar, British women found Indian ways uncivilized, Indian music unpleasant, and Indian paintings garish. Indians were considered useful only as servants, and as servants were constantly found to be inadequate. Few English women learned the language apart from a few words of kitchen Hindustani or knew anything about the culture.

These women were expected to support their husbands, to further their husbands’ careers, and be useful to their husbands’ advancement. Anglo-Indian society was especially backward in granting women any other role. There were few opportunities in India to take nursing classes, attend lectures, or visit hospitals and bring flowers or relief to the old or the sick. Volunteering or performing good works was viewed with suspicion, and young women, who needed to defer to their elders, could not undertake a service if the older memsahib in their area had no interest in the project.

Most of the young women who came out to India met the challenges of life in India—boredom, loneliness, homesickness, dirt, disease, and dangers of various kinds—with courage and good humour, but many others grew depressed and were sooner or later defeated.

Trix was obviously more intelligent, more cultured, and more broad-minded than most of these women, who accepted without question the prevailing culture, which discouraged curiosity, individuality, or originality. But she was not completely unlike them. She was not overly intellectual, had no excessive enthusiasms, was not careless or faithless, did not get too involved in Indian culture, or go native. Like them, Trix had little curiosity about the strange people among whom she was living—Sikhs, Moslems, Hindus, Parsees, as well as the many castes within these groups.

Trix was obliged to socialize with these women when she was with Jack and his fellow officers. But, on her own, Trix found a small group of like-minded women friends who met regularly for tea and talk. These women, including Nettie Webb, an old school fellow from Notting Hill, Sibyl Healey, and Violet Marshall, appreciated Trix’s lively conversation and were curious about the stories she wrote for publication. They approved of her ambitions to succeed as a novelist. Trix confined her conversations about novels and poetry to this chosen group.

Maud Marshall—sister of Violet, and Trix’s friend from her first voyage home and from her teenage years in Dalhousie and Simla—was initially a central part of this literary group. Like Trix, she dreamed of becoming a novelist. Soon after her marriage to Thomas Diver in 1890, Maud moved to Ceylon, abandoning India and her group of friends there. Trix felt her loss deeply. From a distance, Maud remained Trix’s dearest friend and the strongest supporter of her literary hopes.

Maud and Trix were constant correspondents, sharing personal and literary news. They recommended books to each other, quoted favourite lines of poetry, explained their narrative likes and dislikes, and, most importantly, exchanged and edited each other’s manuscripts. Maud was disciplined and productive, sending Trix many pages to approve or amend. Trix envied and admired Maud’s industry, while always chastising herself for laziness. Over the years, Trix and Maud suggested plots and characters for each other, sent their stories to the same magazines, dealt with the same editors, and complained of the same publishing problems and payment delays. Maud was crucial to Trix’s self-confidence and development as a writer during the early years of her marriage in Calcutta.

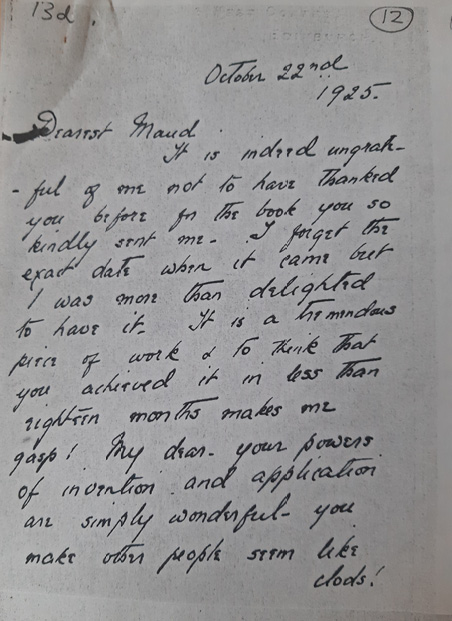

Fig. 23 A letter from 1925 from Trix to Maud Diver (part 1).

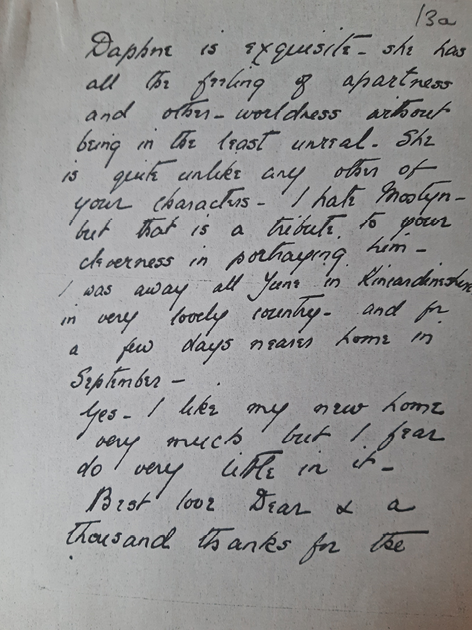

Fig. 24 A letter from 1925 from Trix to Maud Diver (part 2).

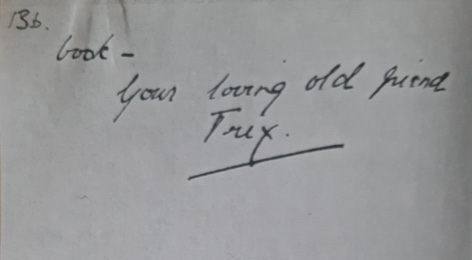

Fig. 25 A letter from 1925 from Trix to Maud Diver (part 3).

Two years after marrying Thomas Diver, Maud gave birth to her first and only child, Cyril. Maud and Trix had married at about the same time. Maud quickly fulfilled her wifely duty by producing a son and heir. Trix did not have a child early in her marriage as was the norm, and this was a great personal sadness as well as a great failing in the eyes of her society. Motherhood was expected of British wives everywhere but especially in India, where children represented a stake in the community and a consciousness that the ruling caste would endure. A childless wife was considered not simply unfortunate, but unpatriotic. In the first year of her marriage, instead of producing a child, Trix wrote and published a novel. While her childlessness was painful to her, she never explained it and rarely referred to it. Trix’s early experiences—abandonment by her parents, possible abuse by Harry, lack of privacy, and invasion of her personal space by Mrs Holloway—may all have contributed to making sexual life problematic for her. Her childlessness was a continual sadness to her, although she never revealed how deep the sadness nor its source. She was devoted to the children of her friends and to her nieces and nephews. She entertained them with stories and magic tricks, sent them presents of books and pictures, and proudly displayed their photographs. In her fiction, Trix imagined children making a great difference in the fate of a marriage, but, having none herself, she could not know how they might have affected her own marriage. Nor could she know how motherhood might have changed her.

If she could not produce a child, she could be a proper wife, a competent hostess, a charming guest, and a published author.

1 Lorna Lee, p. 78.

2 Trix Kipling, letter to Maud Diver, 16 March 1898.

3 Ibid.

4 Trix’s fan reproduced in Lorna Lee, pp. 118–19. The fan, now in the Kipling Collection at Yale University, shows Trix traveling constantly in the fall of 1891 back and forth between Edinburgh, London, St. Andrew’s, Wilden, and Blanefield before returning to India.

5 ‘Wife in Office’, The Pioneer, 2 January 1892; ‘My Sister-in-Law’s Alarms’, The Pioneer, 28 April 1892; ‘Mrs John Brown Protests’, The Pioneer, 7 May 1892; ‘Hunter on Marriage’, The Pioneer, 12 May 1892; ‘My Aunt-in-Law’s House’, The Pioneer, 19 May 1892; ‘Casual Love’, The Pioneer, 22 June 1892; ‘The Judge’s Whist’, The Pioneer, 7 September 1892; ‘In Shadowy Thoroughfares of Thought’, The Pioneer, 27 October 1892; ‘Our Own Correspondent’, The Pioneer, 24 November 1892; ‘In the Blues’, The Pioneer, 1 December 1892.

6 ‘Prose of Trix Kipling’, in Lorna Lee, pp. 170–266.

7 Alice M. Kipling, ‘At a Christmas Ball’, Black and White, December (1892). This is a ghostly version of the story Trix liked to tell of a handsome officer who pledged himself to her and then died in battle six months later. See page 64.