8. Breakdown

©2024 Barbara Fisher, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0377.08

I can see Trix as she holds herself rigidly together, sitting with her mother in the drawing room that had been hastily engaged for her at the Royal Palace Hotel. The towering red-brick pile in Kensington was far less grand than its name promised, but Trix didn’t notice or care where she was. She sat in stony silence, as her mother tried to cajole her into tasting food or sipping water. She didn’t want to answer her mother’s nagging questions—What was the matter? How did this start? What could she do? She didn’t want to take the sips of tea and spoons of broth that her mother kept trying to force between her tight lips. She didn’t want to talk, or eat, or even be where she was.

Trix had been sent from the Fleming home in Edinburgh to the London hotel at her mother’s insistence. The Flemings had been alarmed by Trix’s odd and disturbing behaviour while she and Jack had been visiting with them in the fall of 1898. Trix had seemed fine when she arrived, but soon she was restless and anxious, pacing about the floor and twisting her hands in nervous motions. Then, as the weather grew cooler, Trix became angrier and angrier, marching back and forth and talking furiously and uncontrollably. Unable to stay still, Trix moved nervously about. When at rest, she sat motionless, staring into space. The Flemings were shocked by these inexplicable and violent changes. They had never encountered anything like this and felt helpless to do anything about it. The Kiplings, when they were alerted to Trix’s behaviour, were equally stunned, but they were ready to take control of the situation

.Alice, fiercely protective of her child, asserted her maternal authority, assumed responsibility, and demanded that her child be removed to her care. Jack and his sisters, who had been horrified by Trix’s behaviour and scandalized by her speech, were relieved to send her away. Trix was swiftly transferred to her mother in London, arriving like a hastily dispatched parcel, at the doorstep of the Royal Palace Hotel.

Alice was confident that Trix would recover once in her mother’s care, but Trix remained deeply distressed. Alice repeatedly tried to calm and console Trix, but her improvised efforts made little difference. Eventually, Alice was forced to admit that Trix needed help. Insisting that there was nothing seriously wrong with Trix, Alice refused to consult a medical expert. Instead, she called in Dr Robert F. Colenso, neither a trained physician nor a mental health expert, to diagnose and dose the patient. Dr Colenso believed in the healing power of diet and massage, a gentle treatment that was reassuring to Alice. Eager to placate the worried mother, he agreed that the patient was suffering from a mild temporary malady, and Alice, eager to believe this generous diagnosis, trusted to time and patience. Trix continued to alternate between stony silence and wild raving. Sensitive doctors treating these kinds of symptoms were accustomed to assign benign diagnoses—hysteria or neurasthenia—and to prescribe gentle treatment.

But in the winter, when Rudyard heard the details of Trix’s condition, he stepped in to take charge of the situation. After confirming the reports he had heard of Alice’s resistance to professional care, he insisted that proper diagnosis and treatment be found for his sister. He enlisted the help of Alfred Baldwin and other relatives, who had had some personal experience with mental disorders. When he finally visited Trix at the hotel, he found her, to his horror, sitting in a rigid posture, staring icily into the distance. While Alice fretted and fussed to no constructive end, Rudyard tried to find out what was going on in Trix’s troubled mind. Alice and Rudyard sensed from Trix’s repetitive gestures and mumbled words and sounds that there was one fixed idea whirling around and around in her restless mind. But neither one could discover what this fixed idea was.

Rudyard’s alarm at Trix’s condition was compounded by his frustration with Alice, who denied and dismissed all suggestions that Trix was seriously ill. She remained implacable and obstructive to finding proper medical help, insisting that she could care for her daughter alone. Although Rudyard recognized that Alice’s stubborn denials were endangering Trix, he also recognized that he could not disregard her opinions. He needed her cooperation. He was enraged that he had to use his energies to pacify his mother, while his sister was in real peril. Rudyard advised the doctors that ‘the main point is not to flutter the mother’.1 Rudyard’s own diagnosis was no different from the doctors’—melancholia and depression.

Trix expressed one constant emotion—fierce anger at Jack. She refused to see or speak to him and insisted that she be allowed to remain separate from him. When she was informed that he was planning to visit, she became agitated and anxious. Trix’s rage at Jack and her barely intelligible mutterings about Jack suggest that he had betrayed her and perhaps replaced her. Jack remained a tall, strikingly good-looking man, especially in uniform. He spent a fair amount of time separated from his wife in places where infidelity was common and grass widows abundant. Jack may well have found other objects for his affections. Or Trix may have felt abandoned or in immediate danger of being replaced. Trix, who had been abandoned in the past, feared this eventuality more than anything else, and having it in front of her as a real or imagined possibility could well have precipitated her collapse. She was unwavering in her fury at Jack and her absolute refusal to see or speak to him.

With her family’s intervention and some medical advice but without any legal formulation, Trix was allowed to separate from her husband.

With Alice in charge, in the beginning of December 1898, Trix was treated at a London Clinic again by Dr Colenso. Despite his own dubious qualifications, he called in a respected mental specialist, Dr George Savage, President of the Medico-Psychological Association of the Neurological Society, the editor of the Journal of Mental Science, and author of Insanity and Allied Neurosis (published in 1884).2 Dr Savage’s medically approved treatment hardly differed from Dr Colenso’s—rest, quiet, and not too much sedation. Dr Savage found Trix deep into melancholia and depression and recommended quiet and isolation. She was obstinately refusing to respond when spoken to, show her tongue when asked to, or take food when offered it, and thus she was forced to eat, to take milk and medicine. This was the standard cure of the time—being fed, massaged, and kept quiet. Dr Colenso feared her becoming ‘noisy or listless’, either of which might require committing her or moving her into a private asylum where she could be discreetly looked after. However, as she became calmer and more obedient, she was allowed to remain where she was. Noisiness meant not simply constant chattering but chattering that had an unseemly perhaps obscene character to it. Trix’s wildly shifting moods continued to move from rigidity and mutism to restlessness and constant uncensored talk. After a few weeks, Dr Colenso reported to Jack Fleming that his wife was getting better, that she was sleeping and napping as required. Although she had been forced to take food and would not speak when addressed, she had for the first time given the doctor her pulse. She still refused to show her tongue. Dr Colenso reassured Fleming that he would not put Trix in an asylum unless she had ‘acute mania’.

At the end of December, Trix was slightly better. She ate her meals and took pleasure in her walks. Although she felt less apathetic and more animated, she told Dr Colenso that she did not think she would ever feel the same again. The sympathetic doctor supported Trix’s adamant refusals to see Jack. He responded to Jack’s repeated requests to have his wife restored to him by tactfully recommending patience and restraint. He advised Jack that neglecting his wife altogether for a while would be more likely to bring about a return in her affections than insisting on visiting her. Dr Colenso allowed that Trix might soon be well enough to travel abroad, but suggested her father, not her husband, as her travel companion. But other crises erased the possibility of foreign travel.

In early February, while Trix was in a clinic in London, news arrived that Rudyard and his six-year-old daughter Josephine were both gravely ill with lung inflammations or pneumonia in New York. Alice, anxious about Trix, now had Rudyard and her granddaughter, Josephine, to be concerned about. She sent Lockwood to London to fetch Trix home to Tisbury, and together the three waited for word about the two patients. On 6 March, Josephine died. Rudyard, kept ignorant of his favourite child’s death until his own health was restored, was devastated when he finally learned of his loss. Trix was well enough to understand the tragedy that had just befallen Rudyard and wept when she heard of her niece’s death.

The grieving grandparents settled their ailing daughter into The Gables, their modest grey stone and red-tiled house. Alice encouraged Trix to eat, to walk about the garden, and to sit at the bay window and look out at the cornfield in the distance. Trix continued to vacillate between mutism and ‘almost constant talk—and oh—my dear—nearly all nonsense,’ reported Alice. When Trix returned to her own bright self, as she did during parts of the day, Alice felt hopeful. But Trix would suddenly change and ‘drift away into a world of her own, always a sad one’.3 Trix’s moods continued to shift as a new doctor—Dr N. R. Gowers, another respected specialist in nervous diseases—was called in.

Dr Gowers arranged a lady companion for Trix, Miss Ross. But, as before, Alice protested, jealously guarding her role as Trix’s sole caretaker and protector. When Dr Gowers suggested that Trix go away with Miss Ross, ‘Mrs Kipling was on the verge of frenzy at any suggestion of such a thing—Mr K. yielded to his wife’s excitement, although he was agreeable’.4 Dr Gowers noted that Trix displayed extreme mental excitement or rather intellectual activity, which those who knew her considered excessive in degree, even for her.

Miss Ross stayed for two months at Tisbury, after which she left, persuaded that Trix could do just as well without her. Alice was keen to see her go. Alice, who became nervous and agitated when parted from Trix, was determined not to be separated from her. When the two were left undisturbed, they both calmed.

In returning to her parents’ home, Trix was doubly blessed. She distanced herself from her immediate marital suspicions by separating from Jack. And she was returned to the childhood she had never had. This was her chance to satisfy her ‘mother want’, to compel her mother to take care of her. Some combination of fragility and strategy brought her to Tisbury. It was a situation that both mother and daughter accepted, welcomed, and, in fact, prolonged. It was the treatment designed by Trix and Alice together, and it was the perfect treatment for Trix.

Shortly before her breakdown, in mid-1898 when she was slipping into depression, Trix had been working on a story she eventually entitled ‘Her Brother’s Keeper’.5 She referred to it as her ‘loony story’. The plot focused on Mrs Mary Addison, a middle-aged English woman living in India who confronts, disarms, and calms a violent madman. He is also English, her countryman, the ‘Brother’ of the title. By the end of the story, Mrs Addison has talked the dangerous madman back into calmness, cleverly drugged him so that he can be restored by sleep, and returned him to the prospect of sanity. She deserves the praise of the doctor who credits her with having surely averted murder and mayhem. While Trix was working on the story in Scotland, she complained to Maud that it was ‘bald & dull’ and was undecided about its title, considering ‘The Beginning of a Friendship’ and ‘The Strength of her Weakness’.6 The story, written more than six months before her own breakdown, described the treatment Trix believed most salutary for controlling madness—compassionate maternal care. Amazingly, Trix prescribed the treatment for her own disease—Alice’s tender care—months before she required and received it. Recovering at The Gables, Trix reworked her loony story, deciding on the title ‘Her Brother’s Keeper’. The title tantalizes with a promise of revelations about her actual brother Rudyard but does not in any way deliver. When she was satisfied with the story, she submitted it to Longman’s Magazine, where it was published in June 1902.

The treatment that Trix received was the standard practice of the day. It was also standard for doctors to address all important communication and correspondence to Jack or Rudyard. Trix herself was always spoken of as a person without rights, without a voice in her own diagnosis and treatment.

At the time, there was no effective treatment, proper diagnosis, or even name for what ailed Trix: fluctuating states of manic activity and deep depression. The standard cure for these ills—established by Dr Silas Weir Mitchell, the pre-eminent American specialist in nervous diseases, and adopted in England—was enforced passivity, infantilizing rest, and a fattening regime. Dr Weir Mitchell believed in removing the patient from familiar surroundings, enforcing rest, and reducing outside stimulation.7 This regimen suited Trix, who was happy to be removed from India, Jack, and the constant socializing of Anglo-Indian life. Trix was always described as suffering from a disease of the nervous system. Terms like manic, catatonic, or insane were never used in describing her condition. The doctors were very tactful in their language when speaking or writing to Jack and Rudyard. When communicating with Alice, they were even more circumspect.

From November 1898 to June 1899, and from April 1900 to September of that same year, Trix was a complete invalid, without the ability or the desire to read or write. But during the interim periods and later, she was decidedly well and remarkably productive, writing dialogues, stories, and poems. She worked on two sustained projects in this period—a group of poems conceived and composed in concert with her mother and eventually published as Hand in Hand8, and one hundred pages of comic dialogue featuring a married couple named George and Mabel.9 The poems were often sad, lamenting the loss of love in marriage, while the dialogues were hilarious, presenting a comedy of marital miscommunication and incompatibility. Trix’s poetry from this period featured several clever and devilish parodies, which were not included in Hand in Hand. The dialogues and the parodies were especially brilliant, Trix at her very best. When her mood was good, it was very, very good.

Trix’s poems in Hand in Hand, twice as many as her mother’s, were grouped under various headings: Verses, Sonnets, Indian Verses, Pieces of Eight: A Garden Series, A Thoughts Series, and Echoes of Roumanian Folk Songs. One of Trix’s poems, ‘Where Hugli Flows’, expresses affection and even nostalgia for Calcutta, where she had lived with Jack. These are the first and last stanzas of that poem:

WHERE HUGLI FLOWS

Where Hugli flows, her city’s banks beside,

White domes and towers rise on glittering plain

The strong, bright sailing ships at anchor ride,

Waiting to float their cargoes to the main,

Where Hugli flows.

Yet years hence, when the steamer’s screw shall beat

The homeward track, for us without return,

Our bitter bread, by custom almost sweet,

We shall look back, perhaps through tears that burn

Where Hugli flows.

Among the daughter’s verses were many sweet lyrics and one good sonnet, called ‘Love’s Murderer’. The poem described the loss of love between a husband and wife. As in most of her novels and stories, Trix placed the blame for the lack of love on her heroine. Reading her poetry as autobiography, which is difficult not to do, she blames herself for the problems in her marriage. If Jack had strayed and caused her to fear abandonment, she took responsibility for it. She had never loved him as she should have. She had trusted his love to sustain them both, as he had promised when he proposed. This may have been the final blow for Trix—that Jack, whose reassurance she had relied on, had betrayed her.

LOVE’S MURDERER

Since Love is dead, stretched here between us, dead,

Let us be sorry for the quiet clay:

Hope and offence alike have passed away.

The glory long had left his vanquished head,

Poor shadowed glory of a distant day!

But can you give no pity in its stead?

I see your hard eyes have no tears to shed,

But has your heart no kindly word to say?

Were you his murderer, or was it I?

I do not care to ask, there is no need.

Since gone is gone, and dead is dead indeed,

What use to wrangle of the how and why?

I take all blame, I take it. Draw not nigh!

Ah, do not touch him, lest Love’s corpse should bleed!

‘Love’s Derelict’ takes up the same subject, but it puts the blame squarely on the husband (Jack)—the master who has cast her out, alone and forgotten.

LOVE’S DERELICT

I who was once full freighted for the sea,

Strong timbered, with my ivory canvas gleaming,

Now drift a battered hulk, all aimlessly,

Sun-shrivelled waveworn, useless tackle streaming.

The water washes, like dull sobs in dreaming,

Across the soaked planks that were the deck of me;

I keep no course, who steered so faithfully,

And bear no cargo, who had riches teeming.

Love’s Derelict am I, Love’s Derelict,

Wrecked by his hand, by him flung to disaster;

Drifting alone, through merciless edict,

Alone, cast out, forgotten of my master.

Strong prows of purpose pity as ye pass

‘Memory’ suggests not only abandonment but infidelity, another woman who stole her husband’s love. It also contains a recurring element in Trix’s verse and prose—the death of a child.

MEMORY

I am she who forgets not,

The other women forget, and so they can be happy,

But I am always wretched, because I must remember,

And Memory is so sad.

I had a dream of Memory,

Her two hands held two sorrows;

One sorrow was a sword,

A sword to pierce my heartstrings,

The memory of my daughter, the little one who died.

One sorrow was a snake,

A snake to sting my bosom,

The memory of the woman, who stole my husband’s love.

I am she who forgets not,

And Memory is so sad!

During the period when Trix was writing these sad lyrics, she was also composing a long (100 pages) series of humorous dialogues, featuring a husband not unlike Jack Fleming—remote, rigid, and inaccessible—and a wife somewhat like herself—talkative and busily engaged in vapid domestic chores.10 The dialogues, similar to the Mr and Mrs Brown sketches that appeared in the Pioneer years earlier, were written as comedy. Trix’s actual married life with Jack had ceased to be a comedy and had become a near tragedy of reciprocal incomprehension. The fictional wife, Mabel, was a silly, self-deluded, chattering fool, while George, the husband, was a silent, sulking critic. Using only dialogue, Trix created a portrait of a dry, dull, dissatisfying, and often contentious marriage.

The misalliance between George and Mabel resembled the implacable division between the talkative and effusive Trix and the silent, suffering Jack. If Jack had married Trix in the hope that her vivacity and chatter would energize and entertain him, he had found instead that those traits irked and irritated him. Her lively talk did not revive and revitalize him, as he had hoped, but simply overwhelmed and oppressed him. Similarly, if Trix had married Jack in the belief that his calming influence would balance her volatile moods, she was deceived and disappointed. He was not calm; he was remote.

Over time, Trix recognized that Jack’s stalwart and hearty demeanour and his stolid silence were not strength and calm but a show of strength to mask depression and physical frailty. Her own ebullience, her ancient defence against being overlooked and abandoned, only caused Jack to retreat further into depression. Jack’s silence and unresponsiveness led Trix to feel ignored and alone. These dissatisfactions, while never directly mentioned in the dialogues, form its unspoken background.

Trix mined her own experience as a married woman living in India to paint a clear picture of the occupations available to a proper English wife. Mabel does needlework, writes letters, and attempts to keep a diary. She is busy with the social calendar, attending dinners and weddings, buying gifts, and sending Christmas cards. She drinks tea with friends, where she gossips about other friends—their clothes, their manners, their lovers, and their indiscretions. She plays golf and rides. She borrows books from the library. She attends tennis matches, horse races, and dances. She has her photographic portrait done. She is a member of the Amusement Club. She spends time ordering, reworking, and arranging her hats, her dresses, and her jewels. She goes to visit friends at hill stations in the hot weather without her husband. She travels with her husband on the survey, staying in rustic camps. Her life is an endless round of ordering dinners, keeping the servants up to the mark, and going to the club with her husband.

But Mabel is a fictional creation. She is talkative, indiscreet, envious, and mean. She is utterly insensitive to her effect on others and totally unaware of their feelings towards her. She treats her one friend, Amy, with disdain and derision. She hardly notices her husband or his attitude towards her. He is, for the most part, completely out of patience with her. While she chatters endlessly, he hardly attends, and when he does, it is with criticism, correction, and irritation. She constantly upbraids him, usually about things that are her own fault, accusing him of her failings and mistakes. George, she complains, is always ‘grumbling and fault-finding and making things uncomfortable’.11

Trix assigned to Mabel a few of her own experiences and traits. Mabel tells Amy Forbes, her one friend, that all through her first season she was called ‘Rose in June’. She claims to have mesmeric power. She passed an ambulance course in Simla ages ago and is competent to render First Aid to the Injured. But this is not a self-portrait; no one ever described Trix as selfish and insensitive, although many, including herself, described her as a chatterer.

Trix’s portrait of George, the silent and suffering husband, is deftly created from what he does not say and from what Mabel says in response to him. Throughout the first sixteen dialogues, which are actually monologues, George says nothing, although his remarks can be inferred from Mabel’s replies. Mabel refers to his funny teasing ways, which she makes light of and dismisses. She accuses him of just sitting there, looking cross, and sulking, while she does all the work. When she dismisses George’s complaints without a thought, she is making a mistake. He is not teasing her or joking with her. He is in a state of constant annoyance and irritation with her. He may in fact be in a state of impotent, explosive rage. He mostly smoulders.

In ‘Keeping a Diary’, Mabel laments that George wouldn’t be interested in reading her diary if she kept one. ‘You never take an interest in anything I do, George, and it is so disheartening!’12 ‘A Cheerful Giver’ presents more of Mabel’s carping about her husband’s poor temper: ‘I never knew anyone like you for saying a pleasant thing disagreeably, and it is a habit you should fight against, dear, for it makes the people round you very unhappy’. She continues, ‘It’s no pleasure to me to talk to a man in a raging temper, very much the reverse, I don’t wish ever to speak to you again’. At the end, she says, ‘I’m simply worn out making suggestions for you to carp at’.13 He has not raged or been in a temper; he has simply disagreed, repeatedly and reasonably.

When her friend Amy excitedly discloses that she is engaged to be married, Mabel all but ignores this important news. She is busily intent on sorting through her own dresses. After hardly allowing the giddy girl to speak, Mabel concludes, ‘It’s been so sweet to hear you pouring out all that is in your heart, and you know how lovingly I sympathize. Do come to lunch to-morrow, there’s a dear, and we’ll really settle about the pink satin’.14

In ‘Character Delineated’, Mabel visits a palm reader who reports that she is ‘very talkative’. Mabel objects to this, insisting that she is much too thoughtful to be talkative.

In ‘The Joys of Camp’, Mabel describes, in happy anticipation, the pleasures of roughing it and the welcome change from the usual round of silly social obligations. When she is actually in camp, she complains about sleeping out in the open, rising and dressing in the cold before dawn, and the general boredom and discomfort of rustic living.

In the final monologue, ‘The Pleasure of his Company’, George finally speaks. Sounding very like Mabel, George complains to his wife as they prepare to attend a party at the home of a friend. He criticizes her too youthful dress, her too bejewelled and ornamented person, her lack of a proper shawl, her elaborate and frizzy hair ‘fringe’, her slowness, and lateness. He blames her for not knowing the proper address and for arriving first too early, then too late at the party. He warns her not to sing, prolong the party, or keep him up late. He is unhappy with the food, the drink, and the cheap cheroots he will have to smoke. In general, he is almost as unpleasant as she.

While Trix was writing these dialogues, she was also working on ‘A Christmas Minstrel’—a story in which an unsympathetic husband and wife barely tolerate each other’s company. As the husband sits and composes a holiday poem, the wife sits across from him and knits. When he reads out his lines, she invariably and unenthusiastically approves. He views her handiwork ‘with indulgent scorn’. She finds his verses tiresome, while he concludes, ‘Who would believe the amount of time and trouble you women spend over trifles!’15 Throughout the dialogues, husband and wife ignore or denigrate the occupation of the other.

Another story from the same time, ‘A Sympathetic Woman’16, takes place on shipboard. Mrs Seymour, a sought-after young woman, engages in conversation with a number of her fellow passengers who easily confide in her. Mrs Seymour, without distinguishing one speaker from another, makes only one reply to everything she is told—’I know’. She is perceived as the most caring, compassionate and sympathetic companion by all, although she speaks only these same two words.

Trix submitted several other stories to publishers, but they did not meet with success. The long series of George and Mabel monologues may have been submitted for publication to The Pioneer, where Trix’s earlier Mr and Mrs Brown dialogues had been published. A long, connected series of humorous pieces, they would have been difficult to place. They were never published.

Trix was especially comfortable and confident writing dialogue. It seemed to flow out of her with great ease. She was particularly deft at allowing a character to damn herself with her own words, displaying an almost absurd lack of self-knowledge. Repeatedly in her stories, she portrays one character who chatters heedlessly on about one inconsequential thing or another. The chatterer has no regard for her audience, rushing on impetuously with details. The listener rarely listens, but is preoccupied with his own concerns, out of patience or out of sorts with the chatterer and her silliness. Rarely did Trix create conversation that actually portrayed two people trying to communicate with each other. On the contrary, Trix presented talk as standing in the way of communication, one person stringing words together while the other person tries not to be bothered by the noise.

When Trix was feeling strong, she was able to concentrate and work steadily and productively. Alice allowed her the time and space to write in private.

Intent on keeping Trix close, Alice stayed home with her when she was indisposed or tired. When the two were together at home, they happily cooked meals and baked sweets to entertain friends. Both Alice and Trix were comfortable in the kitchen and delighted in foreign recipes and new kitchen devices. After purchasing a new griddle, they experimented together making waffles and potato cakes. While they both enjoyed creating food, neither one was particularly interested in eating it.

When Trix felt well, Alice encouraged her to visit with friends she and Lockwood had made in the neighbourhood. With a fine understanding of her daughter’s tastes, Alice suggested an introduction to William and Evelyn de Morgan, a distinguished artistic couple, he a ceramicist and novelist and she a painter working in the Pre-Raphaelite style. Trix was agreeable when Alice arranged a visit with Evelyn de Morgan. At first, Alice accompanied Trix when she ventured out to meet Evelyn, but soon Trix was able to go alone to make visits to Evelyn’s studio, where her many large and colourful canvases hung high up on the walls. After a while, Trix felt comfortable walking about the studio, studying the paintings at her leisure. Evelyn walked beside her, describing the allegorical sources and meanings of the crowded and colourful paintings. When Trix asked for complete explanations of paintings that especially attracted her, Evelyn generously showed her verses she had written to accompany some of her allegorical and mythological works. And, to Trix’s surprise, Evelyn confided that the verses had been written in something of a trance. Evelyn, like Trix, harboured a hidden enthusiasm for spiritualism. Although Evelyn’s husband William supported and shared her interest in the spiritual world, Evelyn found it easier to keep her spiritual interests private. Trix understood and sympathized with this deception. She had kept her interest in automatic writing and crystal gazing to herself. Here was Evelyn, an educated and artistic woman who, like herself, responded to poetry, painting, and spirits. Evelyn, she discovered, was a perfect friend.

Trix went again and again to Evelyn’s studio, drawn to both the painter and to the paintings. Evelyn’s art spoke to her, actually called forth poems from her. When Trix entered Evelyn’s studio, she looked at the paintings on view in the studio, paintings in progress or recently completed paintings leaning up against the walls. When she found a painting or sculpture that moved her, she allowed herself to gaze steadily at it and to fall into a trance-like state. In this state, Trix produced verses. She was inspired by Evelyn’s bust of ‘Medusa’ to write a brief poetic response. Its short and simple structure suggests that it was written automatically—quickly and while in an altered state.

Is there no period set: Is pain

eternal?

Still through the eons must her

vipers sting?

For all Eternity the anguish burn?

An endless circle, endless

suffering!

Beauty has lit heaven, shut deep

in Hell.17

While Trix was recovering in Tisbury, Evelyn painted ‘The Thorny Path’ (1897), ‘The Valley of Shadows’ (1899), ‘Love’s Piping’ (1900), and ‘Victoria Dolorosa’ (1900). These are the paintings Trix saw in the studio and was drawn to. Evelyn’s painting ‘The Valley of Shadows’ presented allegorically the fate of the soul at death. The painting provoked Trix to write these lines:

Dark is the Valley—the Valley of Shadows

Weary of heart and of life is the King—

He sits among ruins, and thorny the meadows,

The meadows unfruitful, forgotten the Spring.

A green snake is keeping the Palace’s portal,

The lizard is warder of the desolate halls,

And wine has no savour, and Love the Immortal

Seems fading at even, as fast as the light falls.

O, Dark is the Valley, the Valley at even,

The King’s brow is clouded, the King’s heart is black,

His down-gazing eyes give no glance to the Heaven,

Where angels are winging their homeward-bound track—

Sure in this dark hour at brink of the grave

The Slave seems the Monarch, the Monarch the Slave18

Alice kept Trix close, protected her, and provided space and privacy for her. Trix was calmed by her mother’s care and once calmed, was able to create serious poetry and humorous prose. Alice located an appropriate friend for Trix, and Trix was able to make a close connection to an exceptionally talented woman. While maintaining her reputation as emotionally fragile, and thus sustaining her position as a daughter in need of maternal attention, Trix was remarkably productive in her work—writing verses and dialogues—and remarkably successful in her personal life, making an important new friend.

At the end of December 1900, Trix was considered well enough to take a trip. It was recommended that she travel to Italy with her parents. Travelling with her husband was not considered. Arrangements were made for Trix and her parents to tour Genoa and Florence. Protected and guided by her mother, Trix toured art galleries and churches. She went to concerts and the opera and visited with her parents’ acquaintances. When meeting new people or familiar friends, Trix was her old performing self. She recited, did imitations, flirted, and flattered.

While she was in Florence, she was introduced to Lady Walburga Paget, wife of the British Ambassador to Florence and later to Rome. In 1893, when her husband retired to Britain, Lady Paget bought the Torre di Bellosguardo—a beautiful villa perched above the city, south of Florence. She was living there when she heard about Trix, a beautiful young woman who, she was told, shared her interest in psychic matters. She invited Trix to visit her at the splendid villa, high above the domes and towers of Florence. Trix accepted the invitation and made her way up a perilous hill to meet the titled lady. The gracious older woman eagerly told Trix about her adventures in the spirit world, and, bringing forth her own crystal ball, demonstrated her skill in discovering visions in the crystal. When Trix described her automatic writing, Lady Paget sympathetically encouraged her to continue with it or to return to it, if she had sworn off it. The generous words of this older aristocratic lady, like the friendship of Evelyn de Morgan, were a comfort to Trix. Her own family was distressed by her interest in the world of spirits and made it known that they feared it was a bad influence on her mental health.

One evening in Florence, while dining out with her parents, Trix was introduced to Mrs William James, wife of the famous American philosopher. Mrs James seemed to know who Trix was. Although the Kiplings were only vaguely aware that Trix was the subject of gossip, they uneasily gleaned from Mrs James’s conversation that Trix’s fame had spread. Mrs James had heard of Trix as an exceptional young woman traveling with her parents. She understood that Trix was in the process of getting a divorce, a piece of information that was apparently generally known.

The grounds for the divorce were unclear, but Mrs James believed that the strong support of her parents indicated that the grounds were serious. Mrs James speculated that Trix, who had been separated from her husband for two and a half years, had sufficient cause to undertake this serious step and also had the encouragement of her father, who had apparently never liked the husband, and the approval of her mother, who had recently grown suspicious of him. The Kiplings learned that many others in their circle had heard the rumours Mrs James reported. They were chagrined to learn that their daughter was the subject of talk, especially since the talk was untrue. At this time, no divorce proceedings had been initiated or were even being seriously considered.

Trix returned from the Italian tour feeling triumphant. She settled back into her routine with her parents at the Gables, feeling not simply well but frisky. She was eager to return to her poetry writing. Britain was abuzz with the upcoming coronation of King Edward VII, and Trix imagined the patriotic drivel that might appear from the country’s poets. With her ear for verse and her spirit of play, she composed a series of witty and sly parodies. Published as ‘Odes for the Coronation’ in The Pall Mall Magazine of May 1902, these light verses were deliciously daring.19 She poked fun at William Butler Yeats with a parody of his ‘Lake Isle of Innisfree’, titled ‘The Pavement Stand of Westminstree’. This is the opening stanza:

I will arise and go now, and go to Westminstree

And a campstool take there, that’s very strongly made:

My gold watch will I doff me, for fear of pickpocketry,

And meet with my fellows unafraid.

Disagreeing with Rudyard’s stance on the Boer War, Trix aimed her critical barbs at her brother’s war poems, especially at his ‘The Islanders’. Her poem, ‘The Milenders’, mocks his exalted tone. These are the last four lines of the poem:

Till the Eve of the last great Battle, till the Dawn of the first great

Peace

Neither corn nor the freight nor the cattle, neither import nor

export cease,

And the strong calm School of Nations, full fed, full feeding,

fulfilled,

Takes the Rule of its Obligations as the Powers have surely

willed!20

While the parody of Rudyard is clever, it is not cruel. Trix had a perfect ear for her brother’s verse. No one else knew as well as she how to imitate his voice.

In a more sympathetic tone, Trix wrote this parody of Rudyard’s beloved poem ‘If’, which he had written in 1895. Trix’s parody dates from the period of the Boer War 1899–1902, while she was in Tisbury with her parents.

IF

‘O god, why ain’t it a man?’ –RK

(To a young C. O. now enjoying complete exemption)

If you keep your job when all about you

Are losing theirs, because they’re soldiers now;

If no Tribunal of C.O.s can flout you,

Or tilt the self-set halo from your brow;

If you hold forth, demand your soul’s pre-emption,

And play up conscience more than it is worth,

You’ll win your case, enjoy ‘complete exemption’,

And—at the usual price—possess the earth.

If you can take from college and from city

Culture and comfort all your conscious days,

Take all and render nothing, more’s the pity,

But cunning preachments of self-love, self-praise;

Exempt you are, forsooth, and safely nested,

Above your priceless pate a plume of white,

Protected by this symbol all detested,

Your worst foe—self—is all you need to fight.

If you can claim to follow Christ as Master

(Tell us when he shirked service or grim death),

How dare you plead for freedom from disaster,

And, wrapped in cotton-wool, draw easy breath?

If you evade—not touching with a finger –

The heavy burdens other young men bear,

We dare not breathe the ugly word ‘malinger’

For fear, perchance, your craven soul we scare.

If girls in uniform do not distress you,

If you can smile at verbal sneers made plain,

If you don’t wince when soldier friends address you,

Proffer bath chairs, and greet you as ‘Aunt Jane’,

Then rhino hide is nothing to the human,

Holier than they are, grudge ye not their fun,

But, laddie, realise the average woman

Gives heartfelt thanks that you are not her son.21

When not imitating other peoples’ verse, Trix worked hard to find a publisher for Hand in Hand, the volume of verse she had written with Alice. Writing to Elkins Mathews in February of 1902, Trix enquired politely if he would be interested in publishing a volume of verse by a mother and daughter, not mentioning at first that they were the mother and sister of Rudyard Kipling. When he agreed to publish the book, Trix continued to correspond with him about the work in progress. She had suggestions about all aspects of the book—its length, size, paper, margins, and typeface. On her own, she arranged to have the book published in America by Doubleday at the same time that she was negotiating with Mathews in London. And finally, she proposed that Lockwood should design a drawing for the volume. She pursued this project with great determination, responding immediately to every request from her publisher. Her correspondence with Mathews, written with respect and care, is in every way sane and sensible.

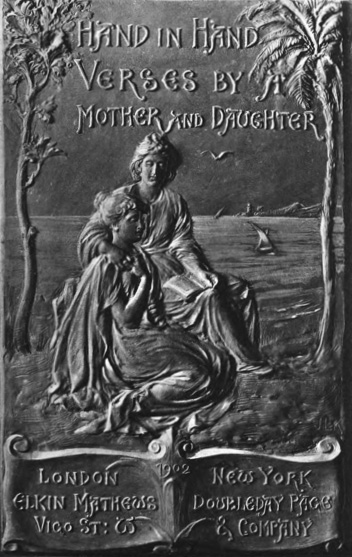

Fig. 26 The front cover of Hand in Hand.

Hand in Hand: Verses by a Mother and Daughter was published anonymously and printed in London by Elkin Mathews in 1902.22 The slender volume contains 31 poems by Alice Kipling, ‘To My Daughter’, and 63 poems ‘To My Mother’ by Alice Macdonald Fleming. The little book bears all the earmarks of a labour of love. A frontispiece illustration in a photogravure by Lockwood Kipling was the father’s contribution to the family collaboration. Lockwood’s illustration depicts a seated woman in classical draperies, her right hand lightly resting on the shoulder of a girl who kneels beside her. It was an open secret that the authors were near relatives of Rudyard Kipling, but the critics agreed that the poems stood on their own merits and needed no outside help.

During the period referred to as Trix’s breakdown, from the late fall of 1898 to the early fall of 1902, Trix was not at all times in a state of mental collapse. In fact, for much of this period, she was calm and content. Once she recovered from the initial shock of Jack’s suspected infidelity, was allowed to separate from him, and settled into a domestic routine with her mother, she was unusually productive. Alice fussed over Trix during this period and was nervously protective of her. Although Alice’s tardy attention could never fully repair the damage of her earlier neglect, it did prove useful. Alice provided Trix with a safe place to recover, where she could be free of whatever anguish and distress Jack was causing and whatever demands he was making. Alice successfully calmed and quieted Trix, allowing her to concentrate and write. Trix rarely wrote this much and would rarely write anything for publication again.

In the early months of 1901, Trix’s doctors as well as her brother reported that she was quite sane. When she travelled to Europe with her parents in the spring of 1901, she charmed everyone she met. When she corresponded with Elkins Mathews in 1902, she was in full command of her faculties.

Thus, in 1902, Trix was faced with a choice. She could pursue permanent separation or divorce and remain in England under the protection of her parents, or she could return to married life with Jack in India.

Although she had been mostly content in the care of her parents, she did not wish to maintain the fiction of madness, which would have allowed her to remain with them. She was not insane. Permanent separation or divorce, which would bring public shame and scandal not only on her but on her family, also troubled her. She was loath to cause her family even more distress. Trix was always quick to accuse herself of wilfulness and ingratitude, and she was afraid not only of public censure but also of her own self-recriminations. Added to all of this was her suspicion that, after four years, Alice was growing weary of tending to her. And finally, Trix recognized that she was growing weary of Alice’s anxious care.

Jack offered another possible future—domestic life back in India. Jack had been constant in his desire to have Trix return to the marriage. He had not abandoned her but, on the contrary, had badgered her to return. In response to Jack’s pressure, Trix, more than once, had made plans to return to India, then cancelled the arrangements and remained in England. She had put off for as long as she could what she knew was inevitable—the return to Jack and India. The alternatives were not possible. She was not mad and she would not pursue divorce.

After four years, Trix had somewhat recovered from the sting of Jack’s perfidy. His repeated insistence that she belonged back in India with him assured her of his continuing attachment. Thus, in September of 1902, Trix relented and complied with Jack’s wishes. After more than two years of good health, good spirits, and a clear mind, she agreed to leave her parents in Tisbury, return to Calcutta, and resume her married life.

With Alice’s cooperation and encouragement, Trix had given herself almost four years of what was essentially a separation from Jack.

1 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Alfred Baldwin, 18 November 1898. Dalhousie University; also in Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. II, p. 353.

2 Dr George Savage was consulted by the Stephen family to treat Virginia Woolf in 1904.

3 Alice M. Kipling, letter to Georgiana Burnes-Jones, 6 March 1899. University of Sussex.

4 N. R. Gowers, letter to Jack Fleming, 15 November 1899. University of Sussex.

5 Alice Fleming, ‘Her Brother’s Keeper’, Longman’s Magazine, June (1902).

6 Trix Kipling, letter to Maud Diver, 28 June 1897.

7 Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s story ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ describes the dire effects of this infantilizing treatment on a young female patient.

8 Hand in Hand: Verses by a Mother and Daughter (London: Elkin Mathews, 1902).

9 Trix, unpublished George and Mabel dialogues, in Lorna Lee, pp. 171–266.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., p. 204.

12 Ibid., p. 234.

13 Ibid., p. 236.

14 Ibid., p. 219.

15 Alice Fleming, ‘A Christmas Minstrel’, in Lorna Lee, p. 287.

16 Alice Fleming, ‘A Sympathetic Woman’, in Lorna Lee, pp. 288–96.

17 Alice Fleming, unpublished manuscript in the archives of the De Morgan Centre, Wandsworth.

18 Alice Fleming, in Evelyn de Morgan: Oil Paintings, ed. by Catherine Gordon (London: De Morgan Centre, 1996).

19 Alice Fleming, ‘Odes for the Coronation’, Pall Mall Magazine, May (1902), pp. 29–34.

20 Alice Fleming, ‘The Milenders’, in ‘Odes for the Coronation’, Pall Mall Magazine, May (1902) pp. 32–33.

21 Alice Fleming, ‘If’ (1902).

22 Hand in Hand: Verses by a Mother and Daughter (London: Elkin Mathews, 1902).