3. The New Museum of Medieval Icons

©2024 Oleg Tarasov, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0378.03

Primitives stepped into the shoes of the High Renaissance artists.

—Aleksei Grishchenko (1883–1977)96

In his 1831 short story Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu [The Unknown Masterpiece], Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) attempted to convince the reader of the impossibility of creating an absolute masterpiece. A masterpiece is an unattainable ideal, sought by the mind of the artist. At the beginning of the twentieth century, however, the concept of the masterpiece changed. Suddenly, far more works were deemed masterpieces, and an entirely new link between the collected object and the personal, aesthetic experience of the individual art lover became of primary importance. The new collector ‘discovers’ a masterpiece, and simultaneously aims to attract attention to it both as a researcher and as a representative of the art market. Moreover, with the rampant rise of capitalism and the swift concentration of capital within the narrow sector of the new bourgeoisie, the market began to extend its reach into the process of sacralizing the masterpiece. It greatly influenced the ‘discovery’ of new artists and the production of counterfeits; it put ownership of masterpieces beyond the reach of the ordinary person, while better quality colour illustrations, advertisements and exhibitions imprinted these masterpieces on the public eye. In other words, significant developments were taking place concerning the masterpiece, its interpretation and its increasing prominence in the art and antiquities market. New art critics were not alone in their concern for the expression and quality of artistic form, and for the early Russian icon’s national style and individuality – the new collectors were also worried. The conception of early Russian icons (and Italian ‘primitives’) as masterpieces of painting became a sensitive subject amongst the new collectors precisely in the era of the Belle Époque (c. 1871–1914).

The Artist’s Gaze: A New Masterpiece of Painting

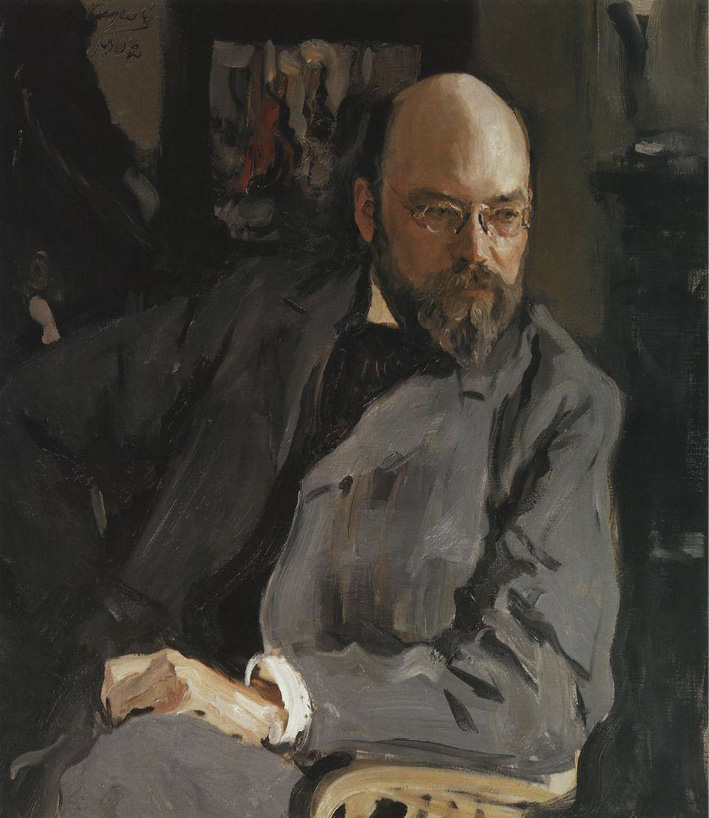

Ilya Ostroukhov (1858–1929) occupied a special place in this dynamic, as an artist and collector, academician of art and trustee of the Tretyakov Gallery, and as the founder of the best private collection of medieval Russian art in Russia (see Fig. 3.1). Ostroukhov may also be considered the founder of the new private museum, in which Russian medieval icons were displayed as masterpieces of painting in special halls.97 Initially, the icons were arranged in Ostroukhov’s private residence amongst works by Russian and Western European painters such as Ilya Repin (1844–1930), Valentin Serov (1865–1919), Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and Édouard Manet (1832–83). However, we know that in 1910, or thereabouts, Ostroukhov planned a special exhibition space for the icons; this may be discerned from sketches preserved in his archive that show a carefully worked out display of the items he had collected. It is clear that the stylized forms of Russian wooden architecture provided the starting point for this space, as did the characteristic elements of the icon walls in Old Believer prayer houses (free of the strict system that governs the iconostasis). This display is the genesis of the icon’s emancipation from the context of religious and ecclesiastical practice. It follows a fundamentally different theory and is intended for Kantian, ‘disinterested’ contemplation. Revealing the universal nature of creativity, the frame of the exhibition essentially articulates the possibility of positioning the icon alongside any work of art and permits the eye to focus on each icon as an individual art object. This reception of the icon as pure art at the same time introduced the secular aura of a national museum, which was characteristic of that era.

Fig. 3.1 Valentin Serov (1865–1919), Portrait of the Artist Ilya Ostroukhov (1902), oil on canvas, 87.5 x 78.2 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Wikimedia, public domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_the_Artist_Ilya_Ostroukhov.jpg

The museum was open to specialists and art lovers around 1911, but its masterpieces were soon accessible to all. By 1917, it housed 125 icons and over 600 items of ecclesiastical plate; 237 pictures by Russian artists and around 40 works by Western European masters, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), Degas, Auguste Rodin (1840–1970) and Manet; 20 sculptures and around 100 examples of art from Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, China and Japan. The museum also had an extremely rich library, with around 15,000 Russian and foreign publications on art, in addition to art magazines and a multitude of books on history, aesthetics and philosophy.98 The museum was nationalized after the 1917 October Revolution, and, in 1920, was named ‘The I. S. Ostroukhov Museum of Icons and Paintings’. By an irony of fate, its former owner was appointed the director. After the collector’s death, the museum was dissolved (1929), its contents dispersed around various collections, and its interiors vanished into the glittering mists of Russia’s cultural past. Such is the brief history of this unique place, which offers a glimpse of the fascinating historical and cultural realities of the very start of the new collecting of Russian medieval painting.

Born into a merchant family and highly educated, Ostroukhov first gained prominence as a talented artist. He was drawn to art by a close relationship with Savva Mamontov’s (1841–1918) family in Abramtsevo, where he took painting lessons with the landscape artist Aleksandr Kiselev (1838–1911). Thanks to his unique abilities he soon garnered extraordinary success. His Siverko painting (1890, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) was purchased by Pavel Tretiakov (1832–98), and lauded by all (most notably by Isaac Levitan (1860–1900), Repin and Serov) as a masterpiece of Russian landscape painting. In 1891, Ostroukhov joined the Society of Wandering Art Exhibitions; in 1903, he entered the Union of Russian Artists; and, in 1906, he became a full member of the Imperial Academy of Arts. He was not, however, attracted by a career as a landscape artist. After his 1889 marriage to N. P. Botkina (the daughter of Piotr Botkin (1831–1907), a prominent tea-merchant), Ostroukhov devoted more time to collecting Russian and foreign art. The contents of his diverse collection were shaped by his natural talent and taste. It included a fairly large number of Russian and foreign artists of secondary importance, a substantial collection of studies, sketches and watercolours, and a limited number of the large, finished paintings that wealthy collectors always sought to secure. It should be noted, however, that all works were of markedly high artistic quality, which testifies to the good taste of this strict aesthete. According to Baron Nikolai Vrangel (1880–1915), the prominent art critic, Ostroukhov’s museum presented such striking examples of work by second-rank artists that they looked like ‘entirely new and unknown masters’.99

Ostroukhov opposed the collection of icons long after his associates had taken up the practice with enthusiasm. Significant early enthusiasts included the scholar-archaeologists Nikodim Kondakov (1844–1925) and Nikolai Likhachev (1862–1936), the entrepreneur Pavel Kharitonenko (1852–1914), as well as those Old Believer collectors from prominent merchant families – the Riabushinskiis, the Morozovs, the Saldatenkovs and others. One of the founders of European Byzantine studies, Kondakov, although not a ‘professional’ collector like Wilhelm von Bode (1845–1929), for example, owned a collection of icons – small but nonetheless interesting in its own way. Kondakov acquired icons – mainly of Italo-Greek style – from time to time on his many travels around the Mediterranean and Near East. Apparently, they aided in the scholar’s understanding of the evolution of Byzantine and post-Byzantine painting, and they inspired him when writing Ikonografiia Bogomateri. Sviazi grecheskoi I russkoi ikonopisi s ital’ianskoi zhivopis’iu rannego Vozrozhdeniia [Iconography of the Mother of God. Greek and Russian Icons and Their Connections with Early Italian Renaissance Painting] (1911). He also collected Russian icons and, in particular, works from those renowned centres of Russian folk icon-painting, Palekh, Mstera and Kholui. A letter of thanks dated 6 December 1909, from Grand Prince Georgii Mikhailovich (1863–1919) to Kondakov, records how, in 1909, the scholar – already then eminent – gave his collection to the Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III (now the State Russian Museum) in St Petersburg: ‘A colleague of mine at Emperor Alexander III’s Russian Museum, which I direct’, the Prince wrote, ‘has brought to my attention the fact that you have donated a systematically assembled collection of early Russian icons and examples of peasant handicrafts made in the Vladimir region villages of Mstera, Kholui and Palekh to the Russian Museum. I consider it a pleasant task to convey to Your Excellency my sincere and deep gratitude for such a valuable and rare academic offering to the treasury of native icon-painting. With sincere respect, Georgii’.100

Academician Likhachev, who amassed one of the biggest collections in Europe of medieval Russian, Byzantine and fifteenth- to seventeenth-century Italo-Greek icons, undoubtedly stands out here. Likhachev’s icon collection (totalling around 1,500 examples) was exhibited in several halls of his own St Petersburg mansion, built especially to house his huge collection. This scholar’s interests encompassed not only medieval works of art, but also examples of material culture which served as sources for his numerous academic works in the most diverse spheres of knowledge – art history, archaeology and sphragistics. His collection therefore included Eastern and Western European manuscripts, eleventh- to sixteenth-century Byzantine and Russian seals, Antique coins and a great deal more besides the Byzantine, medieval Russian and Italo-Greek icons. Embarking on research in palaeography in 1894, Likhachev first became interested in the inscriptions on icons as historical sources; by 1895, however, he had already decided to engage in original research on Russian iconography. His primary focus was the mutual connections between the Russian icon and Byzantine painting, Italian ‘primitives’ and Italo-Greek icons. His travels in Western Europe, Greece, Constantinople and Athos were accompanied by active collecting. In sum, Likhachev was one of the first who strove to demonstrate how icon-painting developed in the Eastern Mediterranean, and he was practically the first to reveal the historical, cultural and artistic value of post-Byzantine art. We know that Italy, and, above all, Venice – which by the second half of the nineteenth century was already becoming the chief centre for trade in medieval icons – played a special role in Likhachev’s collecting. He made major purchases from Rome’s antiquarians too, and in Florence, Naples, Milan and Bari. Italian academic colleagues also helped him. Thanks to the director of the Museo Trivigiano (the Treviso town museum), Luigi Bailo (1835–1932), his collection was enriched with several outstanding examples of Italian ‘primitives’, in particular the Master of Imola Triptych of the Madonna and Child with Saints, from the 1430s, and also Italo-Greek icons of the Mother of God. This active collecting and research bore fruit in the two-volume atlas Materialy dlia istorii russkago ikonopisaniia [Materials for a History of Russian Icon-Painting] (one volume of which presented Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons), published in 1906, and Istoricheskoe znachenie italo-grecheskoi ikonopisi. Izobrazhenie Bogomateri v proizvedeniiakh italo-grecheskikh ikonopistsev I ikh vliianie na kompozitsii nekotorykh proslavlennykh russkikh ikon [The Historical Significance of Italo-Greek Icon-Painting. Images of the Mother of God in the Works of Italo-Greek Iconographers and Their Influence on the Composition of Some Renowned Russian Icons], published in 1911. Emperor Nicholas II (1868–1918) acquired the entire collection in 1913, and thus laid the foundations for the Russian Medieval Painting section of the Russian Museum in St Petersburg.101

Finally, Stepan Riabushinskii (1874–1942), who continued the Old Believer tradition of collecting, was one of the first to perceive the icon as a work of high art as well as a holy object.102 Small, medieval icons for personal devotions predominated in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Old Believer oratories. Riabushinskii began to collect large-format icons, which reminded his contemporaries of early Italian artists’ altarpieces painted on boards, and he was also the first to realize the need to uncover the original paint layer of early works. Old icons decorated the oratory and several rooms of his mansion on Malaya Nikitskaya Street in Moscow, built in 1900–03 by Fyodor Schechtel (1859–1926), one of the most famous architects of Russian Art Nouveau. Today, with the help of the surviving oratory wall paintings and a drawing of the iconostasis, we may only imagine the originality and bravery of combining bright, Art Nouveau-style ornamentation with the exquisite silhouettes of medieval icons. The elegant iconostasis was set in an alcove, along the edges of which ran a stylized ornamental grapevine; large icons of Christ and the Mother of God were supplemented by smaller, personal devotional images, and the Holy Doors of the iconostasis incorporated a netlike ornamentation which clearly came from Scottish Art Nouveau – the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) was popular at that time. A distinctive pageantry arose, therefore, at the junction of various epochs and arts. Gazing upon the decorated walls and ornamental icon settings, the religious experience of encountering old icons was overshadowed by the aesthetic experience. The medieval icons found themselves in a religious and philosophical-symbolic context typical of Art Nouveau, reflecting the personality of one of the first connoisseurs of medieval Russian painting’s authentic beauty.

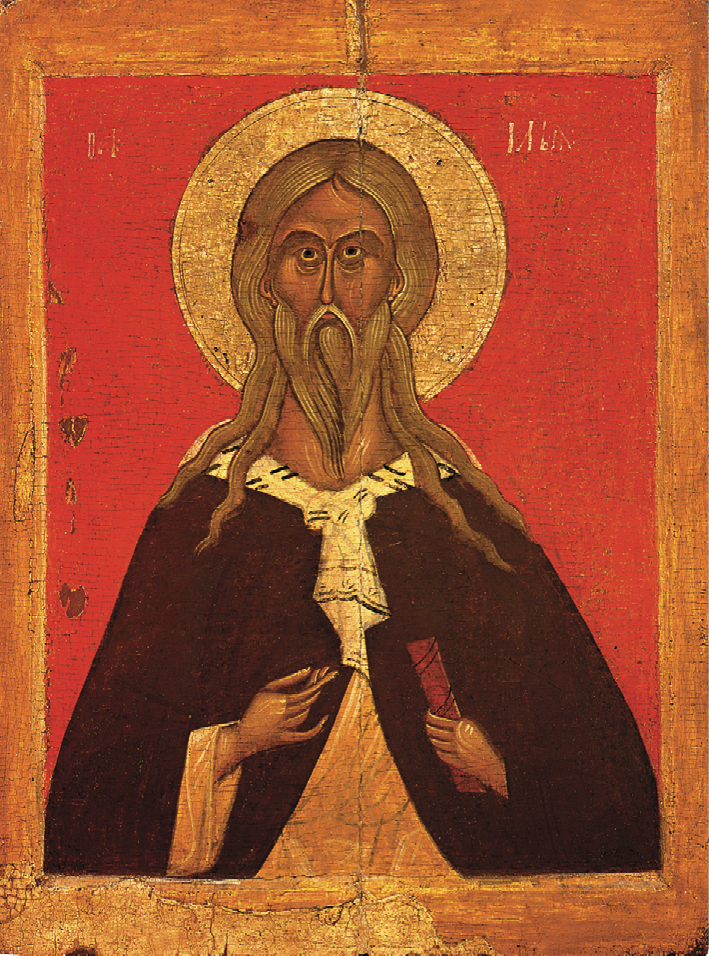

Meanwhile, in 1909, Ostroukhov – by then already prominent as an artist, philanthropist and collector – bought the fifteenth-century Novgorodian icon Elijah the Prophet (in Russian, Ilya Prorok, Ostroukhov’s namesake) (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) on his name day (see Fig. 3.2). This was the start of his famous collection of early Russian painting.103 From this point, he practically abandoned collecting canvases and entirely dedicated himself to medieval icons, spending huge amounts by the standards of the day to acquire them for his collection. Ostroukhov’s genuine passion to discover this still mysterious sector of European art was observed by many of his contemporaries: ‘It became his overriding passion’, Prince Sergei Shcherbatov (1874–1962) wrote about Ostroukhov’s fascination with icons:

He didn’t buy anything else, only at times the odd, rare publication or book which was added to his fine library. Paintings no longer interested him, although earlier he had collected them, and indeed almost nothing else existed for him – everything had been swallowed up by a burning passion that was adolescent-like, almost manic. Of course he valued […] external aspects, too: he loved to dominate in Moscow as the authoritative, refined expert, the foremost patron in a field which was then still new and therefore had excited public interest not only amongst Russians but also among foreigners, who visited the Ostroukhov museum like a sort of landmark.104

Fig. 3.2 Novgorod School, Elijah the Prophet (fifteenth century), tempera on wood, 75 x 57 cm. From the collection of Ilya Ostroukhov in Moscow. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Reproduced as a color illustration in Nikolai Punin’s article ‘Ellinizm i Vostok v ikonopisi’ [‘Hellenism and the East in icon painting’], Russkaia ikona (1914), 3. Photograph by the author (2023), public domain.

It seems possible that the 1908 preparations for a Starye gody [Bygone Years] exhibition in St Petersburg had some influence on Ostroukhov’s turn to icon-collecting. A fifteenth-century Netherlandish Mater Dolorosa from his collection was loaned to the exhibition. Within a few years, Ostroukhov had not only begun collecting icons himself, but had also inspired a wider group of art enthusiasts in Moscow to join in the pursuit of collecting these works. An article on the exhibition, published in the journal Starye gody, stressed that the work of European ‘primitives’ clearly represents aesthetic value, since it manifests ‘the transition from the Gothic, constrained by spiritual bonds, to consciously free creativity’. Moreover, the meaning of the term ‘primitive’ was also explained to a wide circle of readers: ‘The conventionality of this term, which entered the international jargon of art scholarship via French enthusiasts’, the author noted, ‘impedes thorough investigation of the essential aspect of Northern Renaissance painting, which was by no means distinguished by simplicity but, on the contrary, was distinguished rather by the complexity of ideas somehow intrinsic to all transitionary eras in the history of art’.105

The Antiquities Market: Some Parallels

That Ostroukhov unexpectedly began to collect icons in 1909, exactly when we see the greatest demand for Italian ‘primitives’ in the European art market, is significant in this regard. Specialists have observed that the periods 1908–09 and 1920–21 saw the biggest price rises for Italian ‘primitives’ in Europe. As may be recalled, from the second half of the nineteenth century, this market was actively shaped by writers, collectors and enthusiasts of Italy. Major collectors, such as John Leader (1810–1903), Frederick Stibbert (1838–1906) and Herbert Horne (1864–1916), entered the market, turning their homes in Florence into private museums of art history and the daily life of the Italian Renaissance. The formation of major American collections also contributed to market demand for ‘primitives’ during the Belle Époque, which was, in turn, greatly facilitated by Bernard Berenson’s (1865–1959) new methods of attribution, discussed in Chapter Two.106 It was further significant that the fact that the fullest collection of Italian ‘primitives’ in Russia (seventy works) was donated to Emperor Alexander III’s Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow precisely in 1909. This superb collection, gifted to the museum while it was still under construction, was amassed by the Russian Consul General in Trieste, Mikhail Sergeevich Shchekin (1871–1920), mentioned in Chapter One. The museum’s opening was intended to be an important event in Moscow’s cultural life. The newspaper Russkoe slovo [Russian Word] wrote about the extremely rare, genuine works in this collection. Among the exhibits, the work of Jacobello del Fiore (c. 1370–1439) clearly stood out. The Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist and Carmelite monks (c. 1405) was presented on a red background which resembled the red background of Novgorod icons of the fifteenth century.107 In that same year of 1909, the journal Starye gody published an extensive article by Vrangel and Aleksandr Trubnikov (1882–1966) on the Roman collection of Count Grigorii Stroganov (1823–1910), mentioned in Chapter One, which contained reproductions of early Italian painting such as Duccio’s (c. 1255/60–c. 1318/19) Madonna and Child (c. 1300, Metropolitan Museum, New York), Simone Martini’s (c. 1284–1344) Madonna from the Annunciation Scene (1333, State Hermitage, St Petersburg), and the Stroganov Tabernacle (c. 1425–30, State Hermitage, St Petersburg) painted by Fra Angelico (c. 1395–1455) – in other words, works by those artists who would, a little later, be compared with the medieval Russian masters of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by Pavel Muratov (1881–1950).108 One cannot with certainty assert that all this directly prompted the new direction in collecting by an individual already then famous for collecting Russian and foreign art, but, unquestionably, Ostroukhov knew the European art market well, was familiar with the new wave of collecting Italian and Flemish ‘primitives’, and travelled Western Europe exploring museums and galleries of antiquities often and for extended periods.109 Ideas about the genuine rediscovery of the early Italian masters’ artistic value, which the new generation of Western European scholars, headed by Berenson, so effectively portrayed as world class, were clearly circulating in the wider intellectual milieu.

The history of the Moscow collectors’ ‘unexpected insight’ into the artistic value of medieval Russian painting was revived by the new discovery and re-evaluation of the ‘primitives’ in the European culture of the Belle Époque. It reinforced Ostroukhov’s view of medieval Russian icons as typologically equal to the Italian masters of the Trecento and Quattrocento, and more than that, his recognition of their great beauty and value. It is no coincidence that in one of the letters he sent to the Trustee of the Russian Museum, Grand Prince Georgii Mikhailovich, he pointedly observed that ‘our medieval Russian icon-painting is beginning to qualify as the greatest world art […], more significant […] than the great primitives of Italy’.110

The major European exhibitions of Italian, Flemish, Catalonian and French ‘primitives’, which acquainted the wider public with this new type of art for the first time, were of great importance here.111 Museums and private collectors from Russia took part in several of them; in particular, the State Hermitage’s Madonna and Child (1434–36) painted by Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) was shown at the Exposition des Primitifs flamands et d’Art ancient [Flemish Primitives and Early Art] exhibition in Bruges (1902). That same year, an exhibition of Catalonian ‘primitives’ was organized in Barcelona, and, within two years, there had been a whole series of exhibitions dedicated to medieval and pre-Renaissance art. An exhibition of German Medieval Painting was held in Dusseldorf in 1904. In turn, a grassroots audience learned that painting ‘on gold backgrounds’ existed in France, thanks to an exhibition of ‘French primitives’: the ‘suspicion’ of these works, that had taken hold in the era of Classicism, began to disperse. Until then, a fair number of old boards bearing the faces of saints ‘served as shelves in farms’, in the words of Germain Bazin (1901–90).112 Finally, the most remarkable of these exhibitions was the one of Early Sienese Painting, held in Siena from April to August 1904, at which a number of early Italian masterpieces from Stroganov’s Roman collection – including the abovementioned Madonna and Child by Duccio – were presented.113 The catalogue that accompanied this exhibition was luxurious by the standards of the day, including reproductions by the Alinari firm and conveying a sense of the grand scale of this breath-taking exhibition.114 The exhibition was arrayed over forty rooms in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico, and included paintings and works of decorative and applied arts from museum and private collections, and also from functioning churches in Siena and its environs. Paintings were displayed in special venues, with drawings exhibited in glass cases. Large-scale works were exhibited separately, and works by ‘the old masters of Siena’ were displayed alongside icons in the maniera bizantina [Byzantine style], in room number thirty-six. Works by the fifteenth-century artist Stefano di Giovanni (c. 1392–1450), also known as Sassetta, and the Sienese Madonnas by Duccio, Lippo Memmi (c. 1291–1356) and Matteo di Giovanni (1430–95), evoked such genuine rapture in an international public that within several months the exhibition had been shown in London at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, and the English edition of the catalogue was furnished with coloured illustrations and a foreword by the famous British art critic, Robert Langton Douglas (1864–1951).115 An exhibition of Italo-Greek art held in 1905–06 in the Greek monastery of Grottaferrata near Rome is also worthy of note. This was the first exhibition in Italy dedicated exclusively to medieval art. In particular, items from the Roman collection of Giulio Sterbini (d. 1911) and also from the collections of Count Grigorii Stroganov, the Russian Ambassador in Rome Aleksander Nelidov (1835–1910) and the Chair of the Moscow Archaeological Society Countess Praskovia Uvarova (1840–1924), were displayed to a wide audience.116

The first international exhibitions at which medieval Russian icons were shown, held at the beginning of the twentieth century, should also be mentioned here. Even before icons made an appearance amongst works by Serov, Degas, and Manet in Ostroukhov’s Moscow mansion, they were exhibited in Paris by the famous theatre and art impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929), together with paintings by the Russian artists Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910), Repin, Filipp Malyavin (1869–1940) and Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962). Alive to all things new, Diaghilev included icons from Likhachev’s collection in his first exhibition project, Deux Siècles de peinture et de sculpture russes [Two Centuries of Russian Painting and Sculpture], under the auspices of the Salon d’Automne in Paris (1906). ‘The exhibition was not restricted to a display of the creativity of artists from the “World of Art”’, Alexandre Benois (1870–1960) later recalled, but ‘with a fullness unusual for the time, medieval Russian icons were presented’.117 Artist Leon Bakst (1866–1924), who designed the display for the Le Primitive Russe [Russian Primitives] exhibit, presented the ‘Russian primitives’ on gold brocade, perhaps thereby drawing parallels between the medieval Russian icons and early Italian painting ‘on golden backgrounds’.118 According to the press, the Russian section of the exhibition was a huge success, and its icon display was shaped by the 1902 and 1904 exhibitions of ‘primitives’. It should be stressed that this was the first exhibition in which medieval Russian icons were shown together with the works of modern Russian artists. The following year, Princess Maria Tenisheva (1858–1928) organized an exhibition of works from her own collection in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, entitled Objets d’Art Russes Anciens [Artworks of Medieval Russia], in which ‘medieval Russian primitives’ featured prominently. Icons such as the sixteenth-century Mother of God of Smolensk, the fifteenth-century Saviour not Made by Hands and the sixteenth-century Protecting Veil were amongst those exhibited. The now famous Madonna and Child Enthroned, with Scenes from the Life of Mary (1275–80, Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow) by a Tuscan master was also included in the display.119

The ‘primitives’ were finally established in the art and antiquities markets of Western Europe and the United States of America in this same period. Here, yet again, we recall Berenson – not simply as a scholar and expert, but as a collector and intermediary involved in significant antiquarian deals, who elevated the collecting of early Italian painting to a truly global scale. Moreover, he not only helped shape the celebrated American collections of Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), John G. Johnson (1841–1917), Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919) and many others, but also amassed a wonderful collection of Italian ‘primitives’ at his own Villa I Tatti in Settignano, including works by Sassetta, Matteo di Giovanni, Taddeo Gaddi (c. 1290–1366) and other Trecento and Quattrocento masters.120 And while Berenson did not pursue Byzantine art, to this day, several fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italo-Greek icons are found within his collection; evidently the eminent scholar felt that the inclusion of such artworks in no way marred the overall aesthetic impression of the collection, and housing them within a single, indoor environment was entirely appropriate. Furthermore, a whole string of books on medieval Russian painting can be found in his library at I Tatti – testimony that the medieval Russian icon had gradually secured an international audience. These were the works of Muratov, Likhachev, Kondakov, Oskar Wulff (1864–1946) and Mikhail Alpatov (1902–86), as well as three issues of the 1914 publication Russkaia ikona [The Russian Icon] and several others. Berenson was acquainted with Muratov’s book on Ostroukhov’s collection (the library had a luxurious Art-Nouveau style copy), and also with Muratov’s works published in the 1920s in Italian, French and English – La pittura russa antica [Ancient Russian Painting], Les icones russes [Russian Icons], La pittura bizantina [Byzantine Painting] and his monograph on Fra Angelico.121

Meanwhile, if Berenson played a key role in the rediscovery of Italian ‘primitives’ in Western Europe, the collector-artist Ostroukhov played a key role in Moscow’s rediscovery of medieval Russian painting. This points to yet another shared characteristic of the relationships between collecting, scholarly research and the art market in evidence in Russian and Western Europe during the Belle Époque. In London, Florence and Moscow, people directly involved in the fine arts – artists and art critics, rather than academics – began to play an important role in the re-evaluation of medieval ‘primitives’. In addition to collecting ‘primitives’ in London and Florence, Horne (an architect by education) engaged in the graphic arts and designed for the English Burlington Magazine, which he founded together with Berenson and the artist Roger Fry (1866–1934) in 1905.122 A special issue of the Moscow journal Sredi kollektsionerov [Among Collectors], celebrating forty years of Ostroukhov’s collecting, also testifies to the part artists played in revealing the aesthetic importance of the ‘primitives’. Ostroukhov’s efforts as an art connoisseur were summarized with the aid of concepts such as ‘intuition’ and ‘artistic vision’ in articles by Muratov, Igor Grabar (1871–1960), Nikolai Shchekotov (1884–1945) and Abram Efros (1888–1954). His collection taught one to look with precision. In an article entitled ‘Novoe sobiratel’stvo’ [‘The New Collecting’], Muratov discussed Ostroukhov as a ‘participant’ in the creativity of the medieval artist, via his intuitive penetration of the early icon’s artistic form.123 Grabar also wrote about Ostroukhov’s ‘inner vision’ in his article ‘Glaz’ [‘The Eye’], according to which many contemporaries were able to perceive the medieval Russian icon as a work of pure art solely due to the Moscow collector’s keen ability to discern value and beauty.124 Finally, Efros noted, in his article ‘Peterburgskoe i moskovskoe sobiratel’stvo’ [‘Petersburg and Moscow Collecting’] that Ostroukhov’s collection continued a tradition of Moscow collecting in which the masterpiece was often ‘discovered’ by the collector himself and only then confirmed by art criticism.125 In other words, Ostroukhov rediscovered and collected masterpieces of medieval Russian painting during a period of fundamental change in tastes of and knowledge about art.

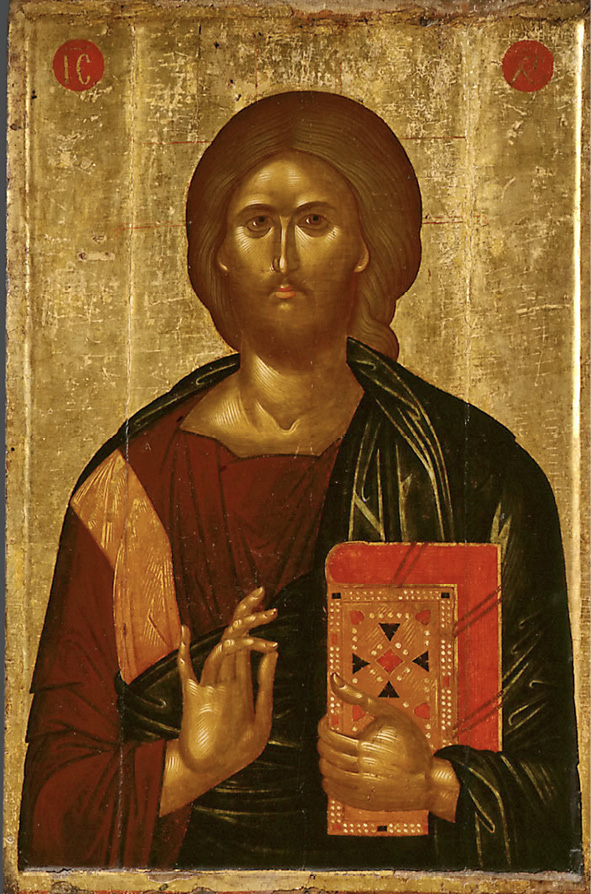

But how, and by which paths, did this new collecting develop? Ostroukhov’s position in Moscow’s art and antiquities circles largely facilitated the successful development of his museum’s icon collection. By 1909, he was already a renowned collector and, moreover, served as a trustee of the Tretyakov Gallery, actively contributing to the expansion of the holdings of this major museum. Constantly surrounded by a stack of catalogues, Ostroukhov knew practically all the major Moscow antique dealers, whose galleries were then concentrated in the Sukharev tower region, in the Hotel ‘Slavianskii bazaar’, Lavrushinskii Lane and the Arbat. These were relatively large spaces, owned by Mikhail Savostin (1860–1924), Sergei Bol’shakov (1842–1906), Ivan Silin (d. 1899) and several others. Ostroukhov had a particularly close relationship with Savostin, who owned antique shops in both St Petersburg and Moscow. A few Greek icons in Ostroukhov’s collection came from Savostin, who travelled to Constantinople in 1914 and brought back a large selection of Byzantine and Italo-Greek icons. One of these, notably, was the famous Byzantine icon of Christ Pantocrator (Constantinople, first half of the fifteenth century, State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow) which specialists today sometimes associate with the Cretan master Angelos Akotantos (1390–1457) (see Fig. 3.3).126 That same year, near Hadrianopolis (now Edirne), Ostroukhov himself obtained a Greek icon of Saint Panteleimon from the second half of the fifteenth century.127 The juxtaposition of Greek and Russian icons in Ostroukhov’s collection was intended to clearly show the unbroken development of the Byzantine tradition in Rus’.

Fig. 3.3 Constantinople School, Christ Pantocrator (first half of the fifteenth century), tempera on wood. From the collection of Ilya Ostroukhov in Moscow. The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Wikimedia, public domain,

Since the issue of the original painted surface is key in the discovery of a masterpiece of Russian medieval painting, Ostroukhov established a workshop in his mansion for his personal icon painter and restorer Evgenii Briagin (1888–1949). In contrast to the majority of Italian ‘primitives’, medieval Russian icons were overpainted many times. The whole impact of the discovery of an early icon lay in the master restorer’s success in layer-by-layer cleaning, which removed each repeated repainting of the original work. This was the case for the restoration of medieval icons in Riabushinskii’s collection, which Aleksei Tiulin (d. 1918) and Aleksandr Tiulin (1883–1920) worked on. The Tiulins were icon painters and restorers, migrants from the village of Mstera, and had long been involved in the trading and restoration of old icons.128 Riabushinskii, notably, had used the new method of cleaning earlier. This is confirmed by the Ascension of Christ icon from the beginning of the fifteenth century – according to Aleksei Tiulin, one of the first and most important in Riabushinskii’s famous collection (see Fig. 3.4). Riabushinskii was also one of the first to witness the original paint layer of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Novgorodian icons being revealed, when he actively participated in the construction of new Old Believer churches after Emperor Nicholas II’s (1868–1918) 17 April 1905 edict of religious toleration. He was the first, too, to set up a restoration workshop at his personal mansion on Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street in Moscow. There, he came to fundamentally revise the Old Believer tradition of restoration work, and his observations are laid out in his article ‘O restavratsii I sokhranenii drevnikh sviatykh ikon’ [‘On the Restoration and Preservation of Early Holy Icons’]. This article concluded, for the first time, the necessity of preserving the authentic painted foundations.129 In Old Believer circles, the restoration of early icons, in essence, meant updating the painted surface. Old icons were cleaned and then repainted.130 Now, in the era of Belle Époque aestheticism, the new cleaning techniques were almost equated with devotion. The original medieval painting acquired especial worth. The icon’s aura as a devotional image seamlessly merged with experiencing it as an authentic aesthetic object. It is therefore entirely appropriate to call the new restoration process an aesthetic one.

Fig. 3.4 Andrei Rublev (1360–1428) School, The Ascension of Christ (1410–20s), tempera on wood, 71 x 59 cm. From the collection of Stepan Riabushinskii in Moscow. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Wikimedia, public domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ascension_(1410-20s,_GTG).jpg

In other words, old icons were being swiftly transformed from objects of ecclesiastical antiquity into priceless masterpieces of medieval painting. The Belle Époque was clearly a golden age of icon collecting, according to the memoirs of many contemporaries. The fashion for medieval icons reached the Russian aristocracy and members of the imperial family. Literally within a few years, interest in Russian icons had gripped a new circle of wealthy individuals; ladies of the highest society, including the extravagant Princess Maria Tenisheva and Varvara Khanenko (1852–1922), as well as scholars, architects, poets and artists, were captivated by icons. Among their ranks was one of the brightest lights of the Russian avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova, whose ‘primitivist’ works were so clearly influenced by the language of the icons and lubki [traditional woodcut prints] she collected. ‘A more serious and loving relationship with the elements of painting’, wrote the artist Grishchenko in this period, ‘naturally engendered in us an artistic interest in, and attraction to, the medieval icon. It was an echo of the French artists’ striving to primitivism in both the sphere of painting generally, and in sculpture. Primitives stepped into the shoes of the artists of the High Renaissance’.131 In other words, there was an altogether new fascination with Primitivism: in this period, the canvases of Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and Paul Gaugin (1848–1903) displayed characteristics in common with the aesthetic value of medieval icons and works of Western European painting ‘on golden backgrounds’. The famous Moscow collector of Impressionists and Modernists, Sergei Shchukin (1854–1936), ordered Matisse’s paintings Dance (1910, State Hermitage) and Music (1910, State Hermitage) for his Moscow mansion, and persuaded Ostroukhov of the value of these works. He did so, precisely, by citing the opinion of the main specialist on Italian ‘primitives’, Berenson: ‘I would like to convince you’, he wrote to Ostroukhov in 1909, ‘that my fascination for Matisse is shared by people who are genuinely devoted to art. In Paris I managed to speak with Berenson, one of the best experts on early art. He called Matisse “the artist of the era”’.132 Incidentally, Berenson is known to have met Matisse in 1908 (through Maurice Denis (1873–1945) and the Steins (Leo and Gertrude)) and even acquired a landscape from him which, within two years, was shown in London in the Manet and Postimpressionism exhibition (1910) organized by British artist and critic Fry.133 There is a photograph of the first version of Dance, which Matisse was working on from March 1909 and which Berenson, in time, reviewed very favourably, preserved in Berenson’s archive at the Villa I Tatti.134 We may also recall here Matisse’s own rapturous response to the medieval Russian icons in Ostroukhov’s museum, which he saw when visiting Moscow in October 1911 on the invitation of Shchukin: ‘I am familiar with the ecclesiastical creativity of various countries’, Matisse said to the correspondent of the Moscow newspaper Utro Rossii [Russia’s Morning] ‘and nowhere else have I seen such feeling laid bare, mystical mood, on occasion religious awe […] I’ve already managed to see Mr Ostroukhov’s collection of early icons, to visit the Dormition and Annunciation cathedrals, the Patriarch’s sacristy in Moscow. And everywhere that same brightness and manifestation of great strength of feeling’.135 During this visit, Matisse supervised the hanging of his Dance and Music paintings in the hall of the grand staircase in Shchukin’s mansion on Znamenskii Lane. In the archive of the Tretyakov Gallery we find an interesting letter from Ostroukhov to Shchukin concerning Matisse’s Moscow visit, which reveals how the two Moscow collectors spent time with the famous French artist: ‘Dear Sergei Ivanovich’, Ostroukhov wrote,

kindly let Matisse know the following programme [of activities] (with me). There’s no concert tomorrow, and I’m not coming over. 29th [October] Saturday. At 11am I’m calling for you both, and we will go to Novodevichy monastery, and from there perhaps breakfast at Kharitonenko’s (he wants to sketch a view of the Kremlin, and they have several interesting icons). 30th [October] Sunday. I’m coming to you by car at around 1–1:30, so we can go to the Rogozhskoe cemetery and the Edinoverie monastery [famous centres of Old Belief with collections of old icons]. 1st [November] Tuesday. I’m calling by at 3 o’clock so we can go to a synodal choir concert put on especially for you […] That’s [what is planned] for the next few days […] I’m sending a parcel with Kondakov’s book; please give it to him from me as a souvenir of the icons. Your I. Ostroukhov. P.S. If tomorrow, Friday, Matisse is free in the evening, then I’d be delighted if you would both drop in on us.136

There are grounds, therefore, for suggesting that Ostroukhov discovered the artistic significance of the medieval Russian icon while the renowned collectors Shchukin and Ivan Morozov (1871–1921) were still acquiring Impressionist and Modernist works.137 Indeed, the collections of Modernist works played a crucial role in shaping a new frame of reference in Moscow, in which intuition about the potential of a work, as well as a keen eye, provided the courage needed to make a judgement. Ostroukhov’s merits and success should be seen, then, in the fact that he clearly was one of the first to discern the significance of the medieval Russian icon in the context of the collecting of Italian ‘primitives’, being able to bring together the expertise of Old Believer collectors and icon-painting antiquarians with his personal aesthetic experience as an artist and collector.

I have already written about the customs and language of the pedlars of antiquities and wandering traders in medieval icons. The Russian North and Volga region were interlaced with trade routes used for the sale of antiquities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.138 It was this efficient trading system that facilitated the huge flow of medieval icons into the Moscow market after the opening of Old Believer churches in 1905, and which allowed Riabushinskii, Ostroukhov, Aleksei Morozov (1867–1934) and others to establish their extraordinary collections of medieval Russian painting in such a short space of time. (The main icon collection in Ostroukhov’s museum, for example, was assembled between 1909 and 1914.) Moreover, if the earlier trade in old icons was confined to a narrow circle of Old Believers, it now reached the wider circle of aesthetes and art lovers. It led to the appearance of a new type of antiquarian and icon painter-restorer. A good example is Grigorii Chirikov (1891–1936), from a family of icon painters in the village of Mstera. The Chirikov brothers’ workshop in Moscow had been set up back in the 1880s. However, on the wave of this new collecting of medieval icons their workshop gained prominence and began to play a role somewhat similar to that of Italy’s antiquarian restoration establishments, such as Stefano Bardini’s (1836–1922) and Elia Volpi’s (1858–1938) in Florence. Chirikov uniquely navigated the new and evolving relationships between collectors, researchers and antiquarians. He acquired and supplied things for the most eminent collectors; many holy objects and masterpieces of Old Russian painting, including the Mother of God of Vladimir (first quarter of the twelfth century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), the Donskoi Mother of God (1382–95, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), and Rublev’s Trinity (1411 or 1425–27, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), were restored by him; he served on numerous committees and academic commissions; he published about restoration work; and he played an active part in important exhibitions of Vystavka drevne-russkogo iskusstva [Old Russian Art] held in St Petersburg in 1911, and in Moscow in 1913. In doing so, he (together with other commissioners) forged fresh ties with the spheres of advertising and the art and antiquities market. It was through his workshop that, in 1907, Likhachev obtained the pearl of his collection – the fourteenth-century Saints Boris and Gleb icon, which subsequently graced the walls of the Russian Museum (see Fig. 3.5). Thanks to Chirikov, a whole series of masterpieces enriched Ostroukhov’s collection, above all the Descent from the Cross and Deposition in the Tomb icons from the end of the fifteenth century, which evoked genuine rapture amongst art critics of the time, and to this day are considered among the Tretyakov Gallery’s finest exhibits.139

Fig. 3.5 Novgorod School, St Boris and St Gleb (mid-fourteenth century), tempera on wood, 142.5 x 95.4 cm. From the collection of Nikolai Likhachev. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Wikimedia, public domain,

The Grigorii and Mikhail Chirikov brothers’ workshop also painted copies and imitations. It is not impossible that some of these were intended to be substituted for medieval icons in certain old Novgorodian churches. The practice of substituting old icons with copies had existed amongst Old Believers since at least the eighteenth century. In the context of religious rivalry, stealing old icons from the official Russian church was framed as ‘saving the faith’ by Old Believers.140 However, during the ‘icon craze’ of the 1910s, this practice lost its religious colouring and began to flourish in entirely different soil. Grabar – an active participant in the cultural life of those years – testifies to this:

Pedlars wandered the North, bartering new icons for old with priests and church wardens […] The old icons were usually lying around in belltowers […] thrown there as decrepit fifty years earlier. But sometimes it was necessary to steal them away from the iconostases of working churches, too, swapping copies for the originals, [a task] for which restorers from Mstera were called upon. In such instances the latter would make a close copy of the old icon, with all its cracks and other marks, under the pretence of restoration, and put it in the place of the valuable original – which would end up in one of the Moscow collections. During the revolution I came across more than a few of these counterfeit icons while on various expeditions to the North. This was how the provenance of many famous works of art was clarified.141

At the same time, firms accorded the name ‘purveyors to the court’ – that of the Chirikovs, of Mikhail Dikarev (d. after 1917), Nikolai Emel’ianov (1871–1958) and Vasilii Gur’ianov (1866–1920) – copied numerous old icons to decorate Old Believer prayer houses, as well as official churches and the churches of the Russian imperial court. Icons from Emil’ianov’s workshop, for example, graced the Feodorovskii Icon Cathedral in Tsarskoe Selo (1909–12, architect Vladimir Pokrovskii (1871–1931)). Mastering the new techniques of restoration, pastiche and reconstruction, Moscow workshops repaired a whole raft of new specimens of ‘old’ icon-painting. The main aim of such aesthetic restoration was not only to create an effect of the original’s well-preserved state, but to make it attractive, and often according to the tastes of Belle Époque culture. Riabushinskii’s icon Saints Boris and Gleb with Scenes from Their Lives (fifteenth century, with later restoration, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) is a good example of this: its central panel is set in a seventeenth-century frame with hagiographical scenes, and most likely dates to the period when the Novgorodian painting from the fifteenth century underwent repainting – in other words, likely in the early 1900s. Interest in the bright colours and refined outlines of the modern era, and in the picturesque effect of the icon as a whole, prompted additions to the original layer, the erasure of unsuitable elements, changing the background, and so on. And what is interesting is that researchers observe the same practices in the restoration of Italian ‘primitives’. The activities of the Moscow workshops and those of the antiques restoration establishments in Italy therefore have much in common.

As demand for fifteenth-century Novgorodian icons burgeoned in Moscow during the 1910s, in Florence and Siena the antiquities and restoration establishments of Bardini and Volpi likewise flourished, driven by the great interest in the Sienese Madonnas of the Trecento and Quattrocento.142 It is notable that the first issue of the Italian magazine L’antiquario [The Antiquarian], founded in 1908 to promote the profession’s interests, opened with a substantial article about Bardini, and also reproduced an anonymous Italian ‘primitive’, a Madonna and Child of the Italo-Byzantine School. This, apparently, was no coincidence, since in Bardini’s house-museum in Florence, a separate installation was dedicated to small altarpieces of the Madonna, many of which – incontrovertibly – underwent the same aesthetic restoration that medieval Russian icons were subjected to in famous Moscow workshops. ‘Bardini made himself an expert in a variety of restoration techniques’, Anita Fiderer Moskowitz notes, ‘and demonstrated enormous skill in transforming ruined works of art into marketable items’.143 The private museum of antiquarian and former artist Volpi in the Palazzo Davanzati also attracted particular attention in Florence; it conveyed the ‘very spirit’ of the Florentine way of life in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and often served as a venue for significant art deals. Its neo-Renaissance interiors were subsequently mirrored in the Florida and Cap Ferret villas of American and European millionaires. These were, of course, decorated with Sienese Madonnas.

The huge success of Italian ‘primitives’ on the international market generated numerous forgeries, which flowed from Florence and Siena to the galleries of London and New York. Researchers have observed that forgeries and imitations with older elements began to appear once British and American collectors began to actively seek out works by Duccio, Pietro Lorenzetti (c. 1280–1348), Sano di Pietro (1405–81), Matteo di Giovanni, Benvenuto di Giovanni (1436–c. 1518) and other Tuscan painters of the Trecento and Quattrocento. At the same time, sarcastic pieces about Giovanni Morelli’s (1816–1891) attribution method began to be published increasingly often, and, in addition to Berenson, von Bode, Max Friedländer (1867–1958), Frederick Mason Perkins (1874–1955), Harold Parsons (1882–1967) and others joined the new circle of influential experts.144 The Sienese Madonnas of Duccio, Benvenuto, Matteo, Lorenzetti and Sano were counterfeited most often. Famous experts in the restoration, copying and forgery of thirteenth- to fourteenth-century ‘primitives’ such as Icilio Federico Joni (1866–1946), Bruno Marzi (1908–81) and Umberto Giunti (1886–1970) were working in Italy during this period. At the same time, the master Alceo Dossena (1878–1937) was flooding the international market with counterfeit works by the famous thirteenth-century sculptor Nicola Pisano (c. 1220/25–c. 1284).145 Joni, who worked in Giovacchino Corsi’s (1866–1930) Sienese antiquities and restoration studio, later wrote an autobiography with the fairly ironic title Le memorie di un pittore di quadri antichi [Memoirs of an Artist of Old Paintings], which was published in Italian in 1932. Within four years it was translated into English and released by Faber and Faber.146 Joni reveals many of the secrets of the copying and falsification of Italian ‘primitives’ in his memoirs. He describes in detail, for instance, how the Madonna’s missing clothes were filled in on a painting by a fifteenth-century Florentine artist, how a copy of a Benvenuto triptych was made for a Sienese antique dealer and how frescos were removed from old church walls. Finally, he recounts in depth the methods of ageing paintings to look like Trecento and Quattrocento works.147 Joni, well connected with antiquities dealers and Anglo-American collectors, including Berenson, also sold imitations and early paintings.148 The unprecedented demand for masterpieces of early Italian painting led to new developments in restoration methods and to new discoveries of the techniques used by old masters. During the Belle Époque, concepts such as original, imitation and forgery become commonplace not only in the Moscow market, but in Florence, Venice and Siena. Italian specialists, like Russian experts restoring medieval icons, removed the soot from works from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, touched up the missing parts of the image, and (not infrequently) completely repainted poorly preserved images on boards and ‘golden backgrounds’, giving them a complete and finished look. They might also make an exact copy of the original on an old board. The Russian restorer, artist and copyist Nikolai Lokhov (1872–1948) stands out amongst such specialists in Florence. Lokhov lived in Florence from 1907, copying Renaissance frescos and paintings by Tuscan artists for the Alexander III Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.149 Since knowledge of the characteristic stylistic elements of Old Italian masters reached new heights precisely at the beginning of the twentieth century, the production of imitations and forgeries was similarly elevated. These entered the Florentine and Sienese antiquities market in great quantities, through the hands of cunning dealers, just as better imitations and forgeries of the ‘Old Novgorodian style’ began to circulate in the markets of Moscow and St Petersburg. As an anonymous contributor to Starye gody acutely observed in 1909, ‘The market in forged medieval icons is as yet almost entirely unstudied, but there can be no doubt that it exists – and rather successfully too’.150

The Popularization of a Masterpiece

The popularization of a new masterpiece, its promotion and entry into academic circulation, became a vitally important constituent of the new relationships between collectors, critics and antiquarians. The masterpiece acquired a new life, taking on a celebrity status, propelled by monographs, numerous advertisements and exhibitions. Muratov’s Drevnerusskaia zhivopis’ v sobranii I. S. Ostroukhova [Medieval Russian Icon-Painting in the Collection of I. S. Ostroukhov], is particularly interesting in this regard. This was, in essence, the first book about the collector and a new type of medieval Russian icon collection, which the author presented in the context of the history of icon collection in Russia. Written in striking prose and containing around eighty phototype pictures of the Ostroukhov collection’s core masterpieces, it was read like a captivating novel in its day, especially compared to the rather dry articles included in the catalogues of other collections. According to the author, only a gifted individual could recognize a masterpiece. This encapsulates the essence of Ostroukhov’s characterization as an educated European collector and artist. Able to grasp the ‘unmediated nuance of creativity’ in medieval Russian icons, Ostroukhov became the first to elevate them to the ranks of world art treasures – in other words, to create that ‘astonishing collection of genuine masterpieces’ in which both the tradition of Hellenistic painting and the tradition of the great Italian masters of the Early Renaissance was resurrected.151 Muratov’s book breathed new life into icon collecting and clearly accords with his essay for volume six of Grabar’s Istoriia russkogo iskusstva [History of Russian Art] (1914), which included, as noted in Chapter Two, a huge number of pictures of Ostroukhov’s icons. Ostroukhov’s icons thus provided the basis for a new history of medieval Russian art, and were compared with the most famous monuments of medieval Russian culture at that time. Since Muratov’s text was not ‘specialist’ and was aimed at a wide readership, the new wave of collectors could fully appreciate the description of one of the best icon collections and the book had significant impact.152

The book’s wide circulation also facilitated a close and amicable connection between the art critic and the collector. Italy as ‘an image of beauty and joy in life’ occupied a special place in this relationship, as numerous documents, postcards and letters testify.153 It may be that Ostroukhov’s acquaintance with the catalogues of Italian collections and exhibitions crystallized the idea of creating, with Muratov’s help, a catalogue of his own collection. Since Ostroukhov was planning to travel to Rome in the autumn of 1912, Muratov wrote to him from Italy about what was worth seeing in connection with their shared interest in icons and ‘primitives’. The Roman collection of Pope Leo XIII’s (1810–1903) financial advisor, Sterbini, which Muratov tracked down at Ostroukhov’s request but did not manage to view, could have been of particular interest. At that point in time, Sterbini’s collection was kept at the palazzo on via del Banco di Santo Spirito in Rome, and included ‘Greek icons’ and works by Tuscan masters of the Trecento. Many of these had been exhibited at the above mentioned 1905–06 exhibition of Italo-Greek art in Grottaferrata – notably the so-called Sterbini Diptych with images of the Mother of God, the Crucifixion and Saint Louis of Toulouse (after 1317, Palazzo Venezia, Rome).154 Berenson also bought a number of works by Sienese masters from this collection. Since Sterbini’s collection was famous for its works in the maniera bizantina, we may assume that Ostroukhov – who, at this point, had also developed an interest in Byzantine icons – set off to Rome in order to make a number of acquisitions.

Muratov’s letter suggests that this was not easy. ‘Dear Ilya Semenovich’, Muratov wrote,

I embarked upon a search for Sterbini on receiving your letter, and delayed answering you in the expectation of visiting Sterbini and viewing his collection. I still haven’t managed to achieve that. My acquaintance, the well-known local professor Antonio Muñoz, passed on a letter to Sterbini but the latter has still not given me any reply. I have dropped by three times and not once managed to catch him in. I’m ready to give it up as a bad job or, more accurately, to pass all the information on to you in the hope that you will be luckier than me [this] autumn. So, Sterbini – the elder and the collector – died recently. He leaves behind three sons, one of whom – A. Niccolò Sterbini – is in charge of the collection. They all live in a magnificent old house (their own) – a little palazzo with a marble cherub on the façade and a beautiful courtyard, on the corner of Banchi Vecchi and Banco di Santo Spirito streets, near the Ponte St Angelo. Their name is ‘d’un certaine consideration’ in Rome, and Muñoz was vague when questioned about the possibility of purchases…

The same letter talks about Antonio Muñoz (1884–1960) preparing a catalogue of icons in the Vatican Library’s Museum of Religious Art (Museo Sacro della Biblioteca Vaticana). At the same time, Muñoz authored the second volume of a catalogue of a hundred masterpieces from Count Grigorii Stroganov’s collection. Muratov strongly recommended Ostroukhov to take a careful look at the Count’s collection, which had made a great impression on him: ‘It is a whole museum […] You absolutely must see the Stroganov house on via Sistina [this] autumn’.155 Ostroukhov stayed in the Hotel Hassler, near the Palazzo Stroganov, during his trip to Rome in October of that same year, and clearly had the opportunity to compare his own collection of medieval Russian icons with the Italian ‘primitives’ and Byzantine icons of the Stroganov collection, and – above all – with the aforementioned Madonna and Child by Duccio. It is most likely that the Moscow collector also knew about the exhibition held that same year (1912) in Siena, dedicated to Duccio and his School.156 While in Rome, Ostroukhov received an open letter from his young friend. In it, Muratov recounted his trip to the Russian North and his visit to Ferapontov Monastery, where he had acquired a rare ‘Stroganov style’ icon of the Trinity.157

Surviving documents and Muratov’s correspondence with Ostroukhov and Berenson reveal that collecting and participation in the art and antiquities market became an integral part of the creative biographies of the new generation of Russian critics and historians of art, just as they did for Berenson or Perkins in Italy.158 Muratov’s collection (which was not large, and was amassed before he emigrated in 1922) included not only medieval icons, but also engravings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–78) (about whom he was preparing to write a book), Japanese woodblock prints and Antique cameos. As discussed, Muratov advised Ostroukhov on art in Italy, and also helped his Yaroslavl publisher Konstantin Nekrasov (1873–1940) to assemble a collection of medieval icons. This is evidenced by an open letter he sent Nekrasov from Venice, in October 1914: ‘Dear Konstantin Feodorovich’, Muratov wrote, ‘I have made one further (final) purchase – I bought a large icon of the Mother of God with two medallions for 190 francs. In my opinion it’s an interesting piece from the fourteenth century. If I’m not mistaken, the outstanding specimens of the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries will be connected specifically with Venice’.159 We discover that Muratov took an expert interest in Byzantine artefacts and Italo-Greek icons in 1914 from one of his letters to Ostroukhov, in which he recounted his plans to go to Venice and hunt for Byzantine icons which Likhachev and Kondakov ‘might pass’, as he put it.160 Among the new generation of Russian art critics and colleagues of Muratov and Ostroukhov, it is worth recalling Alexander Anisimov (1877–1937), who undoubtedly owned one of the most interesting collections of icons at that time. During the wave of new collecting, the young scholar and expert managed to discover and acquire valuable examples of twelfth- to sixteenth-century medieval Russian icon-painting. Amongst these were genuine masterpieces, which today grace the displays of key museums and exhibitions abroad. These include the two-sided icon the Mother of God of the Sign and Saint Juliana (twelfth to thirteenth century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), the Saviour Enthroned (fourteenth century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), the Prophets Daniel, David and Solomon (fifteenth century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), Saint Paraskeva Piatnitsa (sixteenth century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). After graduating from Moscow University’s history and philology faculty in 1904, Anisimov became interested in medieval Russian art while working in Novgorod region. Just as Perkins surveyed the churches of Tuscany and organized exhibitions in 1904 and 1912 in Siena while collecting ‘primitives’, in 1910 and 1911 Anisimov surveyed medieval Novgorodian churches and collected examples of medieval icon-painting which were shown at the exhibition of medieval art in Novgorod, organized as part of the Fifteenth Russia-wide Archaeological Congress in 1911.161 In the same period, Anisimov also helped create the Museum of the Novgorod Diocese, to which he transferred part of his collection. Muratov recalled a visit to Novgorod in the winter of 1912, when he was preparing his essay on medieval Russian painting for the abovementioned History of Russian Art:

I was hosted by A. I. Anisimov while he was still living in a teacher training college in Novgorod region. It was winter. The town itself, and all the surrounding area, crisscrossed by rivers, was covered by astonishingly deep, pure and even snow. For days on end Alexander Ivanovich and I travelled from church to church and from monastery to monastery on little sledges. There was an enormous wealth of art […] with pounding hearts Anisimov and I stood before the most wonderful and ancient icons, sometimes huge in size, sometimes even not completely repainted but simply very blackened by the old, spoiled oil varnish that was so easy to remove.162

Meanwhile, large-scale circulation publications were particularly significant in promoting Ostroukhov’s Museum of Medieval Russian Painting in the 1910s. Information about the museum percolates through the newspapers and magazines Utro Rossii, Tserkov’ [Church], Apollon [Apollo], Starye gody, Khudozhestvennye sokrovishcha Rossii [Artistic Treasures of Russia] and many others. And, of course, along with Muratov’s Sofiia [Sophia], the periodical Russkaia ikona played a special role. This luxurious art publication was issued under the auspices of the Society for the Study of Medieval Russian Icon-Painting, with financial support from Riabushinskii, Ostroukhov, Bogdan Khanenko (1848–1917), Varvara Khanenko (1852–1922) and several others. In a review of this new publication, the journal Sofiia noted that it was conceived ‘as a masterpiece in typographical art’, and its aim was to introduce private collections of medieval Russian icons, one by one, to academic circles.163 Russkaia ikona was connected with the antiquities market: the publication was targeted at the affluent collector, had a limited print-run, and its advertisement declared that ’50 sets are printed on Dutch paper, and – reflecting the desires of our subscribers, are numbered’. The inclusion of Shchekotov’s polemical article in the second issue is significant. In ‘Ikonopis’ kak iskusstvo. Po povodu sobraniia ikon I. S. Ostroukhova i S. P. Riabushinskogo’ [‘Icon-Painting as Art. On I. S. Ostroukhov’s and S. P. Riabushkinskii’s Icon Collections’], Shchekotov called into question academic methods of studying the form of medieval Russian painting. Masterpieces owned by Moscow’s two most renowned collectors were presented by the author as a new type of art that testified to the ‘original artistic achievements’ of pre-Petrine Rus’. Moreover, it was Ostroukhov’s icons, specifically, that Shchekotov considered of revolutionary import for academia: ‘Just as the frescos of Mistra’s churches and the mosaics of Constantinople’s Chora monastery provided the first reliable evidence of the rich artistic life that nourished Byzantine art’, Shchekotov wrote, ‘the icons in I. S. Ostroukhov’s collection call for a complete turnaround in the study of [Russia’s] medieval painting’. As a talented artist himself, Ostroukhov was the first collector of icons to be ‘governed primarily by artistic sense’.164

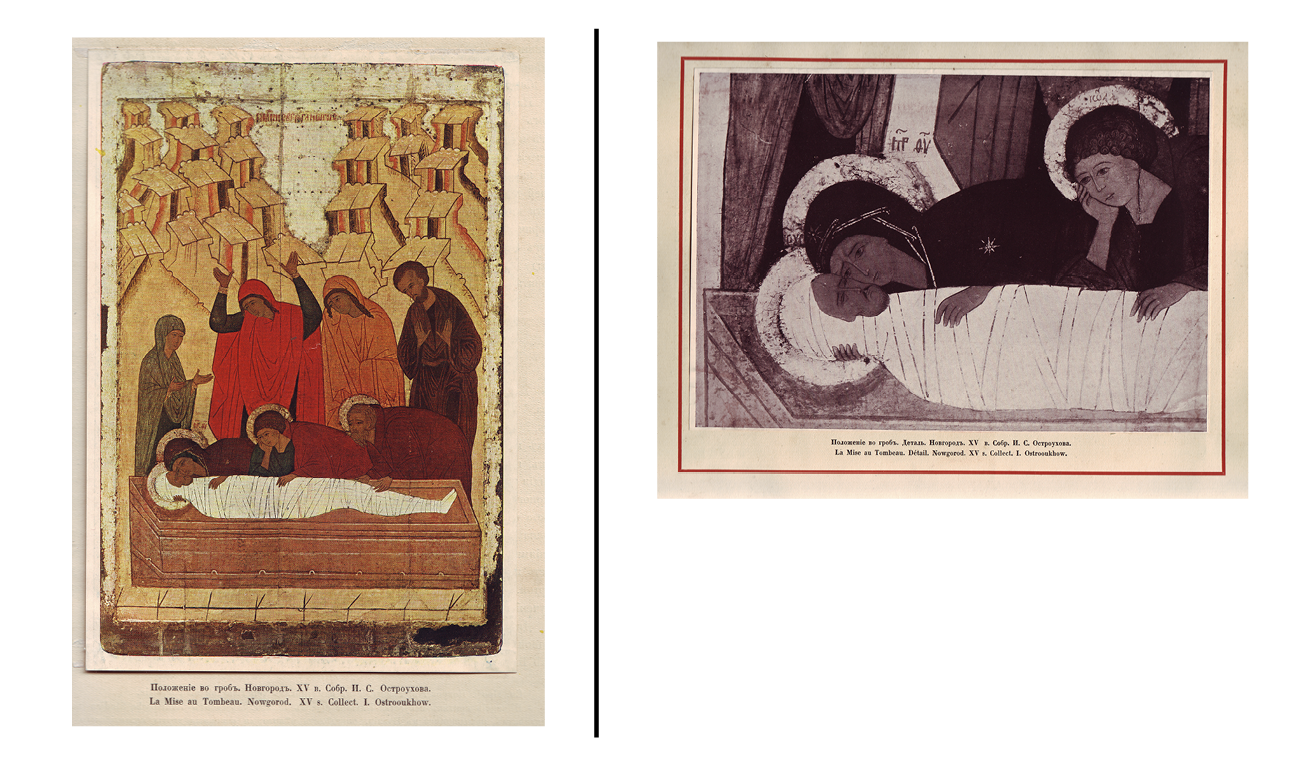

Figs. 3.6a–3.6b Novgorod School, The Entombment of Christ (late fifteenth century), tempera on wood, 90 x 63 cm. From the collection of Ilya Ostroukhov in Moscow. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Reproduced as a color inset in Nikolai Shchekotov’s article ‘Ikonopis’ kak iskusstvo’ [‘Icon Painting as Art’], Russkaia ikona (1914), 2. Photographs by the author (2019), public domain.

A new kind of reproduction, intended to penetrate the very essence of art, also accompanied the Russkaia ikona anthology. Reading the icon as a masterpiece of painting required analysis of form rather than commentary on content, and it therefore became more important to show rather than to tell. Especial skill and attention were given to framing the shot, and also to fragments of silhouettes and faces conveying nuances of emotion. The new illustration educated the eye, taught it to see nuances of form; the new illustration, then, conveyed that the ‘inner’ vision (which Berenson and Muratov had pondered) had nothing in common with an ordinary reflection of the surrounding world but was the result of strenuous spiritual labour (see Figs. 3.6a and 3.6b). Improved colour reproduction, halftone etching and the fine detail of heliographic engraving (photographic illustration) shaped the conviction that a reproduction could adequately stand in for the original. As the reader turned to Russkaia ikona’s high-quality illustrations (the work of one of the finest firms of the day, the R. Golike and A. Vilborg company), they seemed to ‘attain’ the masterpieces. The emotional tone and literary worth of the individual articles made these masterpieces accessible and understandable to a wide readership. Special publications dedicated to the most important works also facilitated this access.

The journal Starye gody is also relevant here. This luxurious art publication ‘for the lover of art and olden times’, was published from 1907 until 1916. Right from the beginning, the journal introduced works of medieval Russian painting in the context of the art and antiquities market in Russia and Western Europe, and of world art collecting. Periodically, the journal included a column headed ‘On Auctions and Sales’, which published information about the most interesting acquisitions, including Italian, Flemish and German ‘primitives’. Famous Russian and foreign researchers – Kondakov, Benois, Adolfo Venturi (1856–1941), Friedländer, von Bode and many others – collaborated with the journal. Essays on medieval Russian icons and frescos were often placed alongside articles on Western European art, and showed icons in the context of collections and exhibitions of early Italian and Flemish painting. In the reader’s mind, then, research on Italian Madonnas illustrated by the works of Duccio and Martini was combined with Russian authors’ reflections on the perspectives of new collectors such as Ostroukhov, Riabushinskii, Morozov and others.165 Since the journal’s aesthetic stance (like that of Sofiia and Russkaia ikona) was that art history should be studied via the very best examples, the masterpiece – whether that be a Persian miniature, an Italian ‘primitive’ or a medieval Russian icon – was consistently defined on its pages as a work of exceptional quality. Finally, it was the Starye gody journal that published two of the most important reviews of the celebrated Old Russian Art exhibition held in Moscow in May 1913, as part of the Romanov tercentenary festivities. These were Muratov’s ‘Vystavka drevnerusskogo iskusstva v Moskve’ [‘The Eras of Medieval Russian Icon-Painting’] and Shchekotov’s ‘Nekotorye cherty stiliia russkikh ikon XV veka’ [‘Some Stylistic Traits of Russia’s Fifteenth-century Icons’], which clearly reflect the connection between the ‘new collecting’ and the new methods of reading the language of medieval Russian art.166

According to the memoirs and observations of contemporaries, large numbers of cleaned, medieval icons from private collections were first viewed by the general public at two major exhibitions. In St Petersburg, this was the 1911–12 exhibition in the Imperial Academy of Arts, and in Moscow the 1913 exhibition in Delovoi dvor [‘Business precinct’], organized by the Nicholas II Moscow Archaeological Institute. Comparing these two exhibitions, moreover, allows us to appreciate the genuinely innovative way of displaying medieval Russian icons employed by Ostroukhov in his museum, and in the organization of the 1913 exhibition in Moscow. In the 1911–12 exhibition, the icons from the collections of the artist Viktor Vasnetsov (1848–1926), Likhachev, Kharitonenko and others were displayed together with crosses, ecclesiastical plate and embroidery. The inclusion of Italo-Greek icons from Likhachev’s collection likely aimed to highlight the Italian influences on Russian icons through the ‘Italo-Cretan School’. The catalogue’s introductory article and a review of the exhibition, both by the art historian Vasilii Georgievskii (1861–1923), convincingly demonstrated that the exhibition was still operating with the traditional understanding of the icon as a work of ecclesiastical culture.167 Moreover, the icons were exhibited in the halls of the Academy of Arts in St Petersburg, which attracted a special kind of audience, closely associated with academic and artistic circles.

What was innovative about the 1913 Moscow exhibition was, firstly, that large-scale medieval Russian icons were hung in a separate display; in other words, they were exhibited in a way that – until then – had been reserved for the paintings of named Russian and foreign artists. Secondly, because the exhibition was part of the Romanov festivities, celebrating three hundred years of the Romanov dynasty, the icon was presented as pure art for the first time to the general public. The exhibition had such an unexpected and deep impact on this broad audience that many refused to believe the exhibited works were genuine. Stripped of their religious and ordinary church context, the general public was asked to view icons for the first time as vivid works of medieval Russian painting: ‘the primary significance of the Moscow exhibition of medieval Russian art’, Muratov wrote in his summary, ‘is the extraordinary power of the artistic impression conveyed by the examples of Old Russian painting brought together in it. For many, almost for all, this impression is one of surprise. An enormous new field of art has opened up before us so suddenly […] it is strange that no one in the West has yet seen these strong, gentle colours, these skilful lines and animated faces’.168 Time and again, Muratov returned to Likhachev’s and Kondakov’s theory about Italian influence on the Russian icon, and to the innate Byzantine and Russian ability to bring Antiquity back to life, as if contesting the way the Academy of Art’s 1911 exhibition was conceived. His brilliant prose and emotional engagement with the topic convinced the viewer, time and again, that what was before them were genuine masterpieces, each reflecting the individual style of a medieval Russian master-painter.

Fig. 3.7 Novgorod School, Mother of God of Tenderness (fifteenth century), tempera on wood, 54 x 42 cm. From the collection of Ilya Ostroukhov in Moscow. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Wikimedia, public domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mary_Mother_of_jesus1.jpg

Fig. 3.8 Novgorod School, St George and the Dragon (end of the fifteenth century), tempera on wood, 82 x 63 cm. From the collection of Ilya Ostroukhov in Moscow. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Wikimedia, public domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Georges_icon.jpg

Fig. 3.9 Novgorod School, Archangel Michael (fourteenth century), tempera on wood, 86 x 63 cm. From the collection of Stepan Riabushinskii in Moscow. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_archangle_Michael_(Novgorod).jpg

For his part, Shchekotov drew out the common characteristics of those works included in the exhibition through formal analysis. Ornamentality, rhythmic repetitions and ‘musicality’ of composition were observed in the most vivid examples, and revealed Shchekotov’s efforts to employ a fundamentally new, contemporary framework for understanding the artistic forms of these works.169 Both authors especially admired the fifteenth-century Novgorodian icons that had such a prominent place in the exhibition. According to Muratov, icons such as the Mother of God of Tenderness (see Fig. 3.7), Descent from the Cross and St George and the Dragon (see Fig. 3.8) from Ostroukhov’s collection, and the Archangel Michael (see Fig. 3.9) and the Ascension of Christ from Riabushinskii’s collection, could be compared with the greatest works of Early Renaissance painting. Muratov was especially captivated by the Descent from the Cross icon, which reminded him of Duccio’s work and prompted discussion of the historical conundrum of the ‘Russo-Byzantine Renaissance’. Given the painterly methods borrowed from monumental art in these specific works (and in the Ascension and Archangel Michael icons from Riabushinskii’s collection), Muratov detected in them a close connection with Palaiologan art. He also observed a lightness and purity of style that distinguished the Russian icon not only from the icon-painting of other nations, but also from Italian Trecento painting: ‘There is much in an icon as beautiful as the “Entry into Jerusalem” that calls to mind Duccio’, wrote Muratov, ‘but this of course is evidence only that Duccio was practically a Byzantine master, and that Berenson was not far wrong when he suggested that he had studied in Constantinople. In Italy and even in Siena Duccio is […] an exception, and not long after him Simone Martini is already a master of Gothic. In contrast, Ostroukhov’s “Entry into Jerusalem” sits naturally amongst other Russian icons of the fifteenth century…’.170

Almost all commentators on the Moscow exhibition observed the participation of collectors of the new wave – art lovers and collectors of the most diverse types of art. It is worth recalling that other famous individuals besides Ostroukhov owned major art collections before they began collecting icons; Aleksei Morozov, for example, was considered one of Russia’s leading collectors of porcelain, while Kharitonenko and the Khanenkos possessed significant collections of Russian and Western European painting. That they all valued this new collectible as a new type of art, just like Western European collectors appreciated early Italian paintings on ‘gold backgrounds’, is without doubt. ‘The native Russian art of the icon’, recalled Shcherbatov, ‘immediately joined the ranks of Ravenna’s sublime, internationally significant artworks, the best frescos of Italian cathedrals, the best primitives, moreover a special Russian tenderness, combined with gravity and festive, joyous colours, distinguished them from all that was familiar to us in religious painting’.171 In this regard, the close connection between the Moscow exhibition of 1913 and the new realities of collecting and investing in antiquities was mentioned more than once in the newspapers: ‘It will not be long’, wrote the Utro Rossii correspondent, ‘before foreign collectors and connoisseurs turn their attention to this unexpected discovery […] Russian icon-painting’s turn to be the Parisian art market’s object of desire will come...’.172 Such sentiments were only reinforced by icons from Ostroukhov’s and Riabushinskii’s collections featuring on the pages of the Parisian journal L’Art decoratif [Decorative Art].173

Finally, the particular significance of the exhibition for the development of the very latest trends in Russian painting featured in many commentaries and reviews. Benois summed up his impressions in the newspaper Rech’ [Speech], generalizing about the exhibition’s impact in the context of the artistic reflection characteristic of the Belle Époque: ‘Even ten years ago’, he wrote,

the ‘Pompei of icons’ would not have made any kind of impression on the art world […] It wouldn’t have entered anyone’s head to ‘learn’ from the icon, to view it as a salvific lesson amid public disorientation. Now things are viewed entirely differently, and it seems as though one would have to be blind not to believe in the salvation offered by the icon’s artistic impact, by its enormous power of agency in contemporary art and by its unexpected proximity to our times. Moreover, some fourteenth-century ‘Nicholas the Wonderworker’ or ‘Nativity of the Mother of God’ helps us understand Matisse, Picasso, Le Fauconnier or Goncharova. And, in turn, through Matisse, Picasso, Le Fauconnier and Goncharova we are able to better feel the enormous beauty of these ‘Byzantine’ paintings…174