Chapter 1: Professing Obedience

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.01

In the European Middle Ages rituals were developed for building social ties, defining groups, and establishing hierarchies. The rituals often involved saying words aloud, doing something with the hands, and handling a charter or book in a prescribed way. Within the church, ecclesiastical officials—bishops and abbots—professed obedience to their superiors, the archbishops. The rituals, which maintained hierarchies, were adapted from the eighth to the fifteenth century to encompass an ever-larger circle of people, including a variety of religious and civic organizations. Earlier (eighth-century) rituals drew upon the legal language and gestures of charters, but this changed, so that the later medieval rituals drew on the visual language and gestures of the Mass: they benefited from the authority of the Gospels and co-opted the legitimacy of the Mass. What had begun in ecclesiastical contexts as professions of obedience morphed into vows, which were more formulaic. These then developed into something resembling labor contracts. All of these forms of social engineering involved uttering words, making particular hand gestures, and leaving marks on parchment in charter, roll, and codex form.

This chapter ranges from eighth-century England to the sixteenth-century Low Countries to chart the way rituals—involving hand, mouth, and document—helped create social stability. Seen through another lens, they promoted conservatism and enshrined subjugation. The theme of books as tools for social control lingers just beyond my analysis. In this period, we can find an ever-widening circle of rituals, which begin in the Church with the upper levels of clergy and expand to include the lowliest nuns and, eventually, laypeople. To tell this story, I will depart from interpreting only written sources to also consider signs of use and marks of wear in documents in a variety of forms.

I. From professions to vows

This section considers the transition from oral to written professions of obedience in Southern England, focusing on their evolution from the eighth century onwards. I will examine the form and significance of these professions, the rituals associated with them, and their broader impact on ecclesiastical community formation. Before the eighth century, bishops’ professions of obedience in Southern England were probably only given orally, but from the eighth century onward, suffragan bishops submitted written professions of obedience to the archbishop of Canterbury. In other words, the ritual changed from an oral one to one that involved oral performance in addition to a written material witness.1

Michael Richter has edited the 301 surviving professions of obedience made by bishops throughout England, who submitted their written statement to the archbishop of Canterbury.2 Of these, 30 date before the Norman invasion, while the bulk of them date from 1070–1420.3 The pre-Norman English examples are the earliest that survive in Europe. In this period abbots also began producing similar professions in the south of England within the diocese of Kent (specifically, the abbeys of Faversham, Bradsole, St Austin’s, Langdon, and Cumbwell), and at Chertsey, Glastonbury, and Malmesbury further afield.4

The professions are important for understanding the sense of self-formation and group-belonging that operated in various later ecclesiastical brother- and sisterhoods, as the form of the written profession morphed and adapted. This section will survey some of those changes in order to think about how the parchment sheet and the body were implicated in group formation in a number of different contexts.

Canterbury’s role and the influence of Lanfranc

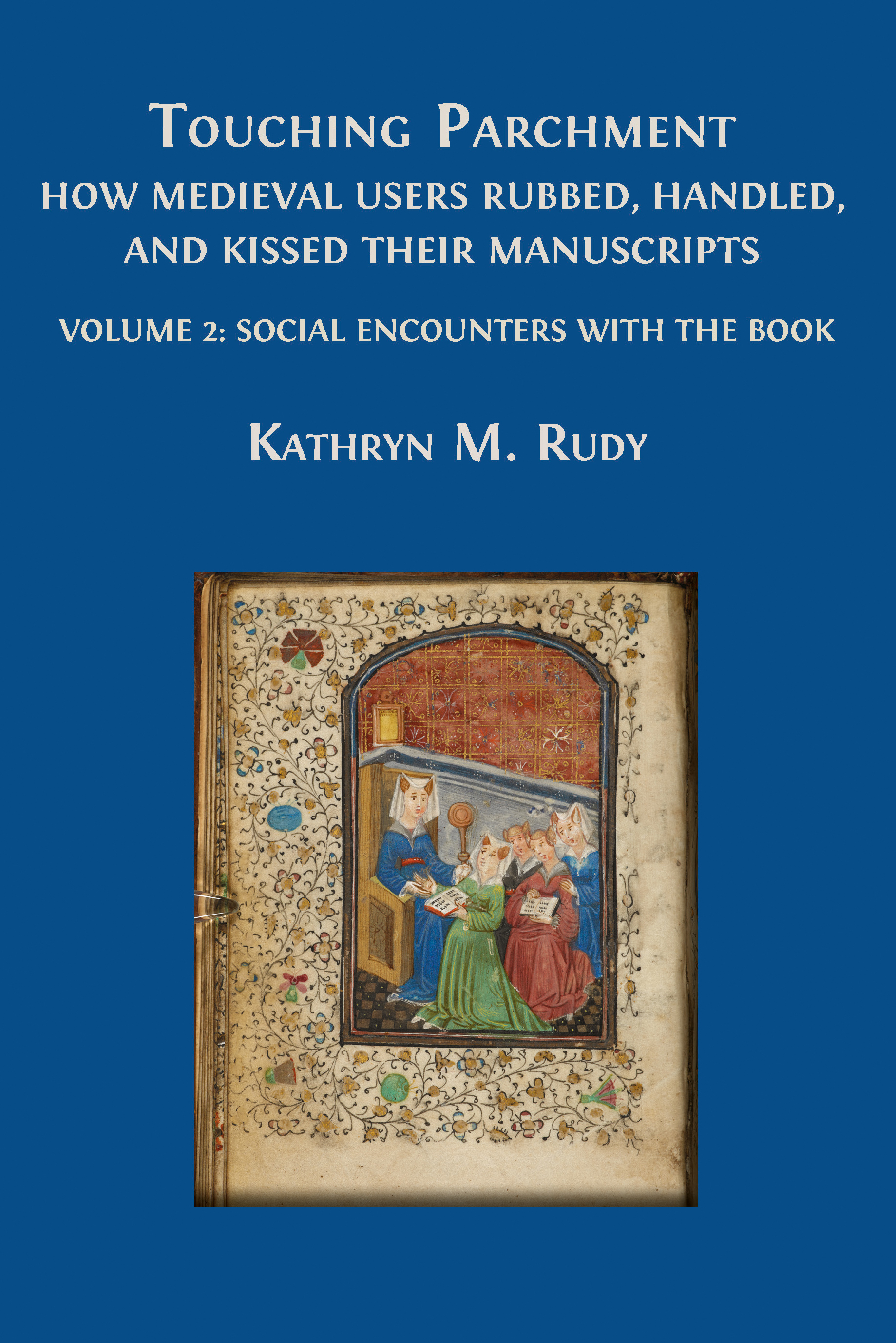

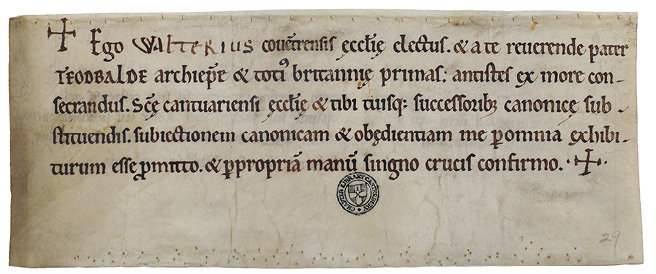

The Canterbury professions take the form of small rectangles of parchment, or charters, inscribed in the first person, which loosely follow one of several formulae (Fig. 12).5 They were produced at Canterbury Cathedral, beginning in the eighth century, but they were not made systematically until the archbishopric of Lanfranc (d. 1089). Lanfranc—famed teacher, feisty defender of the doctrine of transubstantiation, and political mastermind—lived in a Benedictine monastery in Normandy before crossing the English Channel. After the Norman Invasion of 1066, William the Conqueror selected him as archbishop of Canterbury, a position he held from 29 August 1070 until his death in 1089. Lanfranc quickly replaced many of the Englishmen in positions of power with Normans. To ensure loyalty, he rejuvenated the practice of extracting professions of obedience from all abbots and bishops. Even other archbishops professed obedience to Lanfranc, including Thomas of Bayeux, archbishop of York (1072), and Patrick, archbishop-elect of Dublin (1074).6 With Canterbury and York serving as the only two archdioceses in England, Lanfranc and subsequent archbishops of Canterbury wanted to solidify their position and maintain power by having bishops profess obedience to them. They attempted to compel all abbots and bishops to travel from their monasteries across England to Canterbury to undergo an impressive ceremony, and thereby impose a single, unified community of ecclesiastical leaders across Britain, under a single head.

Fig. 12 Briefs of profession of obedience, mounted in the nineteenth century on a card. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, DDc/ChAnt/A41, sheet contains nos 3–10.

Language in the professions reveals aspects of the ceremony. For example, Maurice, elect of London, offered a long and flowery profession, which I translate in part:

…He unjustly demands obedience from his subjects, who disdains to present it to his superior. Therefore, venerable Father Lanfranc, Archbishop of the holy Church of Canterbury and Primate of the whole British Isles, I, Maurice, elect of the Church of London, promise to obey you and your successors according to the canons and institutions of the holy fathers. Of my obedience, I hand over and extend my profession to you in your hand. [The merciful almighty God] deigns to sanctify me by coming through your hands with his Holy Spirit.7 (Emphasis mine)

The text mentions hands thrice: first as a verb to state that the subject is handing over the charter of profession; second as a noun, referring to Lanfranc’s hand that receives the document, a gesture that is apparently essential to the ritual; and third as a metaphor, to state that Lanfranc’s hands are a conduit for the Holy Spirit. These gestures, together with the uttered words and parchment-as-prop, sealed the contract.

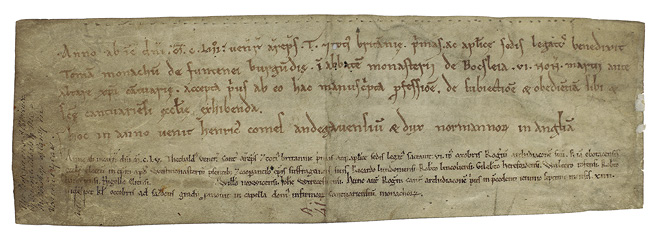

Another aspect of the ceremony can be inferred from an abbot elect who made his profession on 2 March 1154:

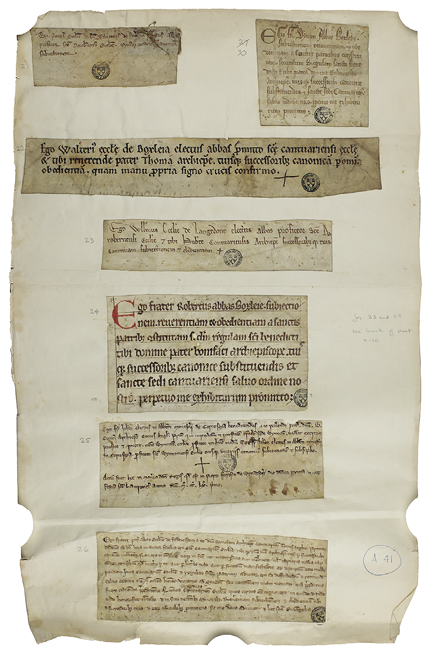

I, Thomas, the elected Abbot of the Church of Boxley, promise canonical obedience to the Holy Church of Canterbury and to you, Reverend Father Theobald, Archbishop and Primate of all Britain, and to the legates of the apostolic see, and to your successors. I confirm this obedience with my own hand, signing with the sign of the cross: + (Fig. 13)8

Fig. 13 Brief of profession of obedience of Abbot Thomas. Canterbury, 1154. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, DDc/ChAnt/A41, no. 2

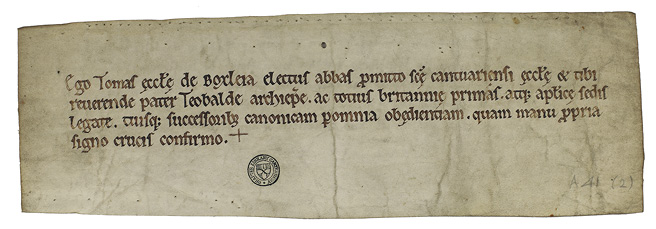

Fig. 14 Reverse of profession of obedience of Abbot Thomas. Canterbury, 1154. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, DDc/ChAnt/A41, no. 2

As is clear from the language, signing with one’s own hand was essential to meaning-making. The verso of Abbot Thomas’s charter bears an inscription that sheds more light on the ritual of profession (Fig. 14). It indicates that, on 2 March 1154 at the high altar of the Cathedral, Archbishop Theobald blessed the new abbot Thomas, who had been a monk of Fontenay in Burgundy.9 This endorsement, describing how the ritual took place at the high altar at Canterbury Cathedral, is corroborated by a medieval description of a ritual of profession:

One by one, they shall approach the altar and read their profession. After they have finished reading, they shall place the profession on the altar and make the sign of the cross with ink on the document. Let their master ensure that there is ink and a pen there. Once they have made the cross on the document, they shall hand the documents into the hands of the abbot and kiss his hands on bended knees. Then the abbot shall hand the documents to the sacristan.10

Although the ritual took place at the high altar, there is no mention of subjects placing their hands on a Gospel manuscript while uttering the inscribed words. Instead, the aspirant would complete two acts with his hands: he would inscribe the cross on the charter with his own hand, and he would place the charter in the abbot’s hands. The signed charters served as a proxy for the individual, so that the act of placing the charter in the hands of the master can be likened to that of a vassal placing his hands within the clasp of an overlord during a ritual of fealty (see Fig. 6).

Profession vs. oath

A profession (professio) is similar to but distinct from an oath (iuramentum), as the latter involves a binding statement made with supernatural authority while touching a relic or sacred book. Breaking the terms of a profession is called a lie (mendacium), while breaking an oath is called perjury (periurium). The punishment for the former is excommunication, and for the latter it is the more severe deposition.11 However, pronouncing professions, as we will see below, takes on many of the trappings of swearing oaths, especially after ca. 1200, when words and objects (particularly, a Gospel manuscript) were used to invoke the deity.

When aspirants signed with a cross, they made their promise more oath-like, but more importantly, they participated with their own hands, since they (normally) did not inscribe the letters. Consider the profession of Thomas of Boxley, for example. Even though the words, inscribed in a neat textualis, are written in the first person, they have not been inscribed by Thomas, but rather by a professional scribe, probably in the scriptorium at Christ Church priory, Canterbury, which employed a bevy of scribes.12 On the other hand, the cross at the end of the statement has been made with a different quill, one apparently wielded by the aspirant Thomas; even though the cross comprises only two strokes, one can see that it is significantly less confident than are the words above it. Thomas has only added the cross at the end, by way of acceding to its promise by making the sign with his own hand.

The subscription “confirmed with my own hand” (propria manu confirmo) has parallels with the language of charters, and clearly professions borrow administrative language from this legal convention, which provides a form of authentication. The phrase appears regularly in all of the professions from the eighth and ninth centuries. However, under the archbishops Lanfranc (1070–1089), Anselm (1093–1109), Ralph d’Escures (1114–1122), and William of Corbeil (1123–1136), very few of the bishops-elect used this formula: theirs were truly professions and not oaths.

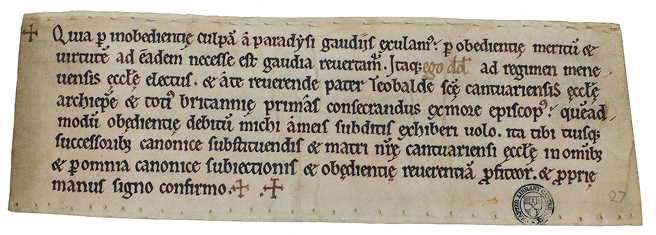

Fig. 15 Profession of Walter Durdent, elect of Coventry (2 October 1149) under Theobald. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, ChAnt-C-115 / 29

Under the archbishopric of Theobald of Bec (1139–1161), two things changed: aspirants added the cross and they wrote their own names. For example, Walter added a cross to the beginning and end of the charter and filled his name into the blank with the best capital letters he could muster (Fig. 15).13 David was even more enthusiastic, adding three crosses to his charter in brown ink, alongside an abbreviation of his name (Fig. 16). Later in the twelfth century, with archbishops Thomas Becket (1162–1170) and Richard of Dover (1174–1184), most charters ended with the propria manu confirmo phrase, plus a cross inscribed by the aspirant. This twelfth-century interest in employing this theatrical gesture, which also makes a mark on the page, corresponds to the period in which priests and bishops kissed an ever-larger cross at the Canon of the Mass.14 Whereas the addition of the crossing gesture referred to legal language in the eighth- and ninth-century professions, the gesture in the thirteenth century may be more immediately drawing on the theatricality of the Mass.

Fig. 16 Profession of David fitzGerald, elect of St David’s (19 December 1148), under Theobald. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, ChAnt-C-115 / 27

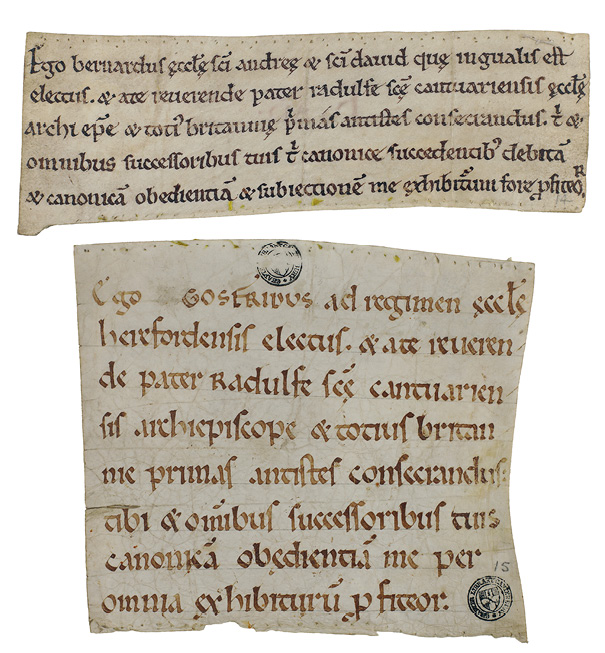

Archival structure: Sewing the charters

The Canterbury professions have needle holes, top and tail. The documents have now been disassembled to be stored singly or mounted on cards; however, when they were first made, each was sewn with a needle and thread to the end of a roll of similar charters. Some yellow thrums still adhere to two of the charters (Fig. 17). The curved shapes of the two pieces of parchment match, suggesting that these two charters were once stitched end-to-end with yellow thread.15 This served not only as a storage method, but even more importantly, presented a visible and continuous legacy of ecclesiastical authority.

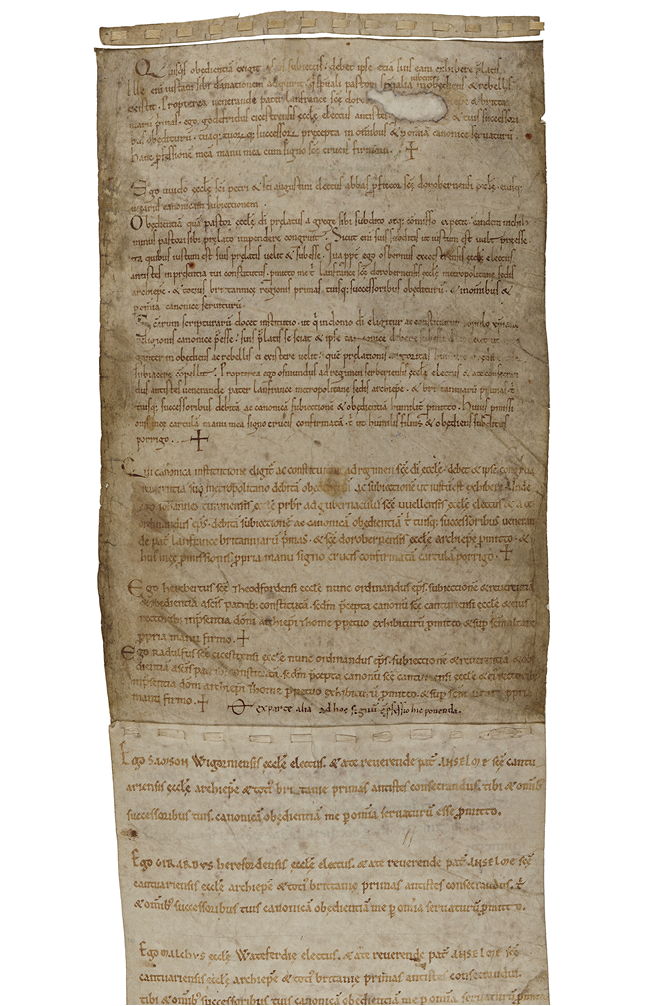

Fig. 17 Profession of Bernard, elect of St David’s (19 September 1115) and profession of Geoffrey de Clive, elect of Hereford (26 December 1115), with remnants of yellow thread that once connected them. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, ChAnt-C-115 / 14 and ChAnt-C-115 / 15

With each profession representing one man, the charters joined up to create a diachronic community, stitched together through time. Even some of the cartulary versions of profession charters—that is, early transcriptions—were produced in roll format, with the membranes laced together with thin parchment strips, which foreshadowed the possibility of endless accretions in a Christian continuity that would last until Christ’s second coming (Fig. 18). Their connected form was integral to their function as documents that stretched forward and back into time.

Fig. 18 Briefs of profession of obedience, recopied in the Middle Ages. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, ChAnt-C-117, membrane 1 and part of membrane 2

II. Professions in later centuries and broader

social contexts

A. From charters to codices

Written professions became more prevalent in the fourteenth century and encompassed a widening circle of religious. For example, in an illuminated English Pontifical made around 1400, with additions made about a decade later (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Ms. 79), one finds a series of illuminations depicting the ordination and confirmation of deacons, priests, bishops, abbots and abbesses, and the coronation of kings and queens, among other rituals.16 One of these illuminations depicts a nun handing her profession of obedience to a bishop at an altar as he blesses her. The profession is depicted oversized, as a scroll, to distinguish it from a codex (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19 Folio in a Pontifical showing a nun submitting her profession of obedience. England, ca. 1400. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Ms. 79, fol. 92r

These examples show that the charters of profession imposed a community with a particular hierarchical structure upon religious leaders in England, involved a ritual that took place at the altar, choreographed symbolic use of the hands, and sometimes made use of the sign of the cross that was borrowed from administrative parlance. The idea of inscribing professions of obedience seems to have originated in Canterbury but would have easily spread across England, since all bishops had to travel to Canterbury to partake in the practice. When their scope broadened, their medium changed, too. When professions were no longer made on individual sheets that could be signed, handled, handed over, and stitched together, all of these ritual actions shifted or disappeared.

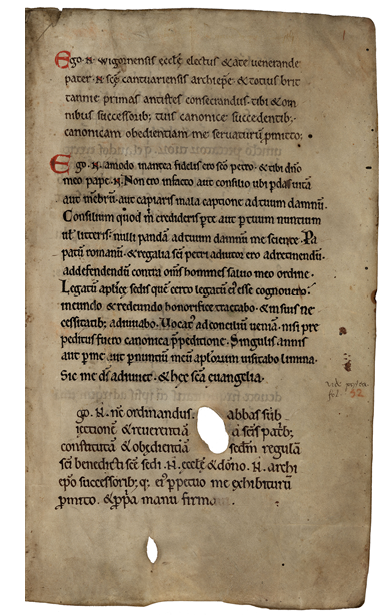

The Samson Pontifical is so called because it contains formulae for professing obedience to Samson, bishop of Worcester (1096–1112).17 The core of the manuscript, now in the Parker Library (Cambridge), was made in the early eleventh century, and it then received many additions, including the formulae for professions, which were added to the front of the manuscript when it was nearly a hundred years old (Fig. 20).18 The first text—an episcopal profession to Canterbury from the early twelfth century—looks similar to those produced in Canterbury, with several important differences. In the Samson Pontifical, the text is a generalized formula, so that the name is given as “N,” to be replaced with a candidate’s actual name. One can imagine the candidate either reading the text aloud, or having it read aloud, and repeating it back. In either case, it would not be appropriate for him to make a cross at the bottom of the formula. If everyone did so, the margin would soon be cluttered with crosses.

Fig. 20 Profession formulae added to the Samson Pontifical in the early twelfth century. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 146, p. 1

The second text in the Samson Pontifical is an oath of fidelity to the pope, also from the early twelfth century, but written in a different script. It too presents a generalized formula: “Ego N. amodo in antea fidelis ero sancto Petro et tibi, domino meo pape N…” (I [state name] will be faithful to Saint Peter and to you, my master, Pope N…). The ending, however, presents something new. It reads: “sic me deus adiuvet et hec sancta evangelia” (so may God help me and by these holy Gospels). The statement assumes the presence of a new prop: a Gospel manuscript. This prop takes the place of an inscribed cross. With the shift from individual profession charters to a general one written in a manuscript, the manner of acceding to the terms of the profession shifts from signing with a cross to acknowledging the presence of the Gospel.

The next generation of forms of professions appears in another book type: the Register of Henry of Eastry, prior of Christ Church, Canterbury (1285–1331). Henry kept meticulous notes about running the Cathedral. His resulting manuscript, written ca. 1310–1331, is now preserved in the British Library (Cotton Ms. Galba E. iv).19 It contains, inter alia, the forms for a bishop to profess his obedience to the archbishop of Canterbury. The wording has developed from that of the previous generation. It begins: “In Dei nominee, amen” (In the name of God, amen), and it ends with the subscription: “Sic me Deus adiuvet et sancta Dei evangelia. Et predicta omnia subscribendo propria manu confirmo. + ” (So may God help me and by these holy Gospels of God. And I confirm everything written above by signing with my own hand). By the early fourteenth century, signing “with my own hand” and mentioning the Gospels had become de rigueur. Including a Gospel manuscript in the ritual made it even more theatrical, and also made it more like an oath than a profession and gave it more of the trappings of a Mass than of a legal deposition.

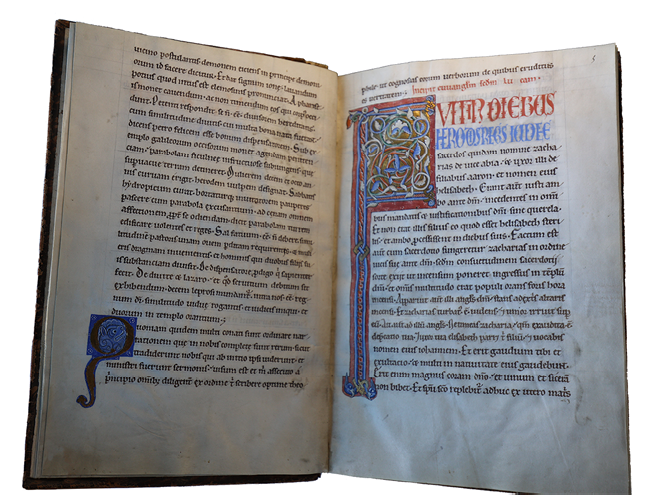

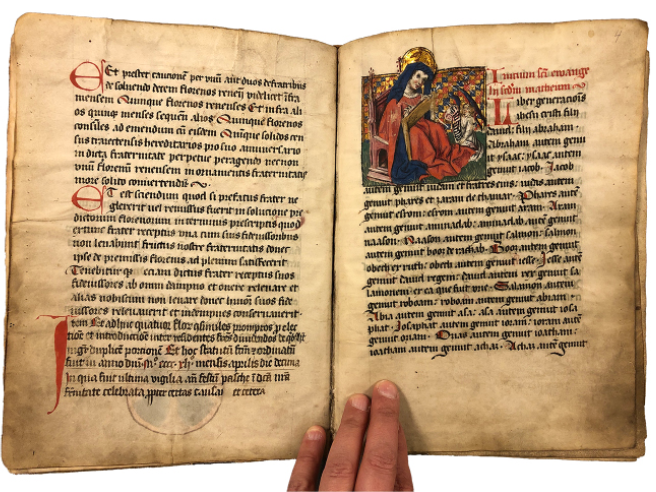

B. Continental translations

In the course of the fourteenth century, the ritual continued to become more elaborate, as illustrated by the Arenberg Gospels (New York, Morgan Library and Museum, Ms. M. 869).20 Like the Samson Pontifical, the Arenberg Gospels were used for decades, or in this case, centuries, before the formulae were added, demonstrating that the core manuscript was still in use but also took on additional functions. The manuscript’s antiquity, foreignness, and colorful decoration may have contributed to its function as a prop in ritual spectacles.

Produced in Canterbury around 1000–1020, the Arenberg Gospels were in Cologne by the 1070s as attested by a note on one of the blank folios indicating that Pope Gregory VII had canonized Archbishop Heribert of Cologne (ca. 970–1021). Heribert’s elevation to sainthood took place between 1073 and 1075. The manuscript adopted a new role beginning in the fourteenth century, when officials at the Church of St Severin in Cologne began writing professions of obedience in the Canterbury manuscript. The professions are similar to those written in Canterbury, but with several important differences:

- Each abbot or monk in England had his own profession inscribed separately; each was personalized, and the individual charters were kept by the cathedral in Canterbury, where they formed a continuous record. By contrast, the professions in the Arenberg Gospels were inscribed directly into the existing manuscript, on the blank leaves found from fols 1–9. Instead of being individualized (as the Canterbury professions are), those in the Arenberg Gospels are generalized—that is, written for the office rather than for the person. Therefore, instead of saying, “I, Richard, bishop-elect…”, they read, “I, N,” where the N stands for nomen, or “insert your name here.” Because the professions in the Arenberg Gospels are generalized, the resulting document does not keep a running list of the various abbots, bishops, and clergy. This is also a function of the format, whereby a roll can be infinitely expanded by sewing more membranes to it, but a codex can only be expanded with the considerable labor and expense of rebinding.

- Because on the Continent the resulting document was a codex (and not a roll), it played a different role in the ritual. The candidate using the formulae in the Arenberg Gospels would neither write his name nor inscribe a cross. Nor would he hand the manuscript to the officiant as part of the ritual. Instead, the use-wear evidence showed that a different ritual took place: the Arenberg Gospels were fitted with a full-page Crucifixion, which many (hundreds?) of hands have touched. Those reciting the words inscribed in the manuscript would apparently touch the image while making their pronouncements. In other words, scribes were not using the Arenberg Gospels as an exemplar to make individual charters, but rather, the aspirants were making their professions with their hands directly on the manuscript. Instead of inscribing a small cross “with my own hand,” each aspirant laid his own hand on one enormous cross in the manuscript.

- Whereas the bishops and abbots only handled the Canterbury charters, the various people making professions in Cologne using the Arenberg Gospels touched the image in the manuscript (the Crucifixion). The candidates were also, de facto, touching a Gospel manuscript which, as we have seen earlier, stood as a proxy for Christ and raised the ritual to the level of one witnessed by the divine. What they were doing was no longer a profession, but an oath.

- In the century after the Norman Invasion, the professions in Canterbury covered bishops and abbots. What is most surprising is the degree to which usership widened even further in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In this period, the number of roles utilizing such professions expanded considerably, to include vicars, canons, and the petty-aristocratic castle-lords.

C. An expanded role for the Pontifical

When the practice of making professions crossed the Channel, for the most part it changed into a different material form—from charter/roll to codex. The new Continental form therefore implies a new set of book-handling gestures. The other shift that professions underwent is that they became more oath-like, relying not only on the cross but also on the Gospel to give them credibility. The substrate could be a Gospel manuscript—as with the repurposed Arenberg Gospels—but it could be any liturgical manuscript that normally belonged at the altar. The earliest surviving Continental manuscript containing a profession is Paris, BnF, Ms. Lat. 12052, a sacramentary written in the second half of the tenth century by the order of Ratoldus, Abbot of Corbie, with the profession (generalized, whereby the candidate fills in his own name at the blanks with his voice, not with a pen) appearing at fols 14v–15v.21

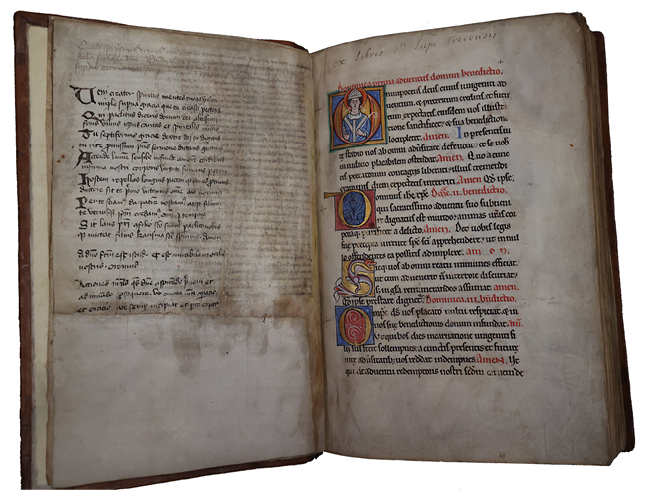

Fig. 21 Incipit for the first Sunday in Advent, Pontifical of St Loup, ca. 1150–1200. Troyes, Cathedral treasury, Ms. 4, fols Bv-1r

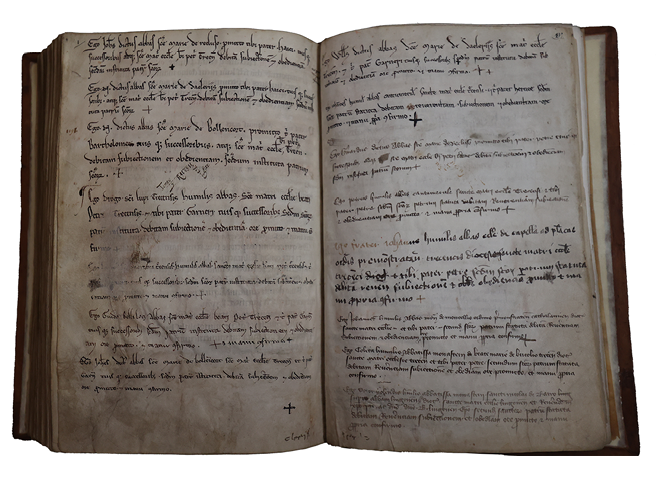

Or the substrate could be a Pontifical, such as the Pontifical of St Loup, written and illuminated in the twelfth century (Fig. 21).22 The Abbey of St Loup, an Augustinian foundation in Troyes, was destroyed during the French Revolution, but many of its books have survived. Like all Pontificals, this one contains the instructions and words to be uttered for a bishop to perform various rites. Noteworthy about this one is that various important information has been added to the beginning and end of the book, with papal bulls and a poem about a devastating flood in the front matter, and professions in the back. The Pontifical itself fills 174 folios. The final verso was blank, and onto this blank space professions of obedience were inscribed, so that they would be in the bishop’s manuscript and written straight into the institutional history (Fig. 22). When this folio was filled, a bifolium (fols 175–176) was added to the end so that professions of obedience could continue to be inscribed into the book itself. These were individuated (similar to the Canterbury professions), not generalized (such as those in the Arenberg Gospels). When these folios were filled, a quire of six leaves (fols 177–182) was added, and then a singleton (fol. 183), and finally another bifolium (fols 184–185). These bits of added parchment were not high-quality, but rather tawny scraps added to meet an urgent need, so that 113 professions of obedience could be successively inscribed between 1191 and ca. 1531.

Fig. 22 Professions of obedience added after 1191 to the Pontifical of St Loup.Troyes, Cathedral treasury, Ms. 4, 174v–175r

These professions in the Pontifical of St Loup vary little and follow this formula:

I, N, humble abbot of {monastery of X}, {of the order X, of the diocese of Troyes}, to the holy mother Church of Saint Peter of Troyes and to you, Father N, and to your successors, according to the institutions of the holy Fathers, promise the due subjection and obedience, which by my word and with my own hand, I confirm.23

As with the professions from Canterbury, the texts were inscribed by professional scribes, and the aspirant merely added the cross. Making his mark in the physical book, which presumably lay on the altar as it received his ink, was an essential part of the ritual. With two small strokes, he left his indelible sign in the historical record.

Hundreds of years of precedent created an undeniable weight of historical gravitas to later signatories. Nevertheless, several things changed in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. First, abbesses of Troyes began signing the record in 1384, using the same strokes of the cross as their male counterparts. Then, around 1400, the male monastics began signing their own names (Fig. 23). This undoubtedly reflects an increased literacy among the brothers, namely an ability to wield the pen and not just to read the resulting words: reading and writing were distinct skills. Their undisciplined handwriting is nearly indecipherable but does the important job of letting each man make his distinctive mark on the page. The women followed about 50 years later.

Fig. 23 Professions, witten in the fifteenth century, added to the Pontifical of St Loup. Troyes, Cathedral treasury, Ms. 4, fols 178v–179r

The Pontifical of St Loup is exceptional because the abbots and abbesses had their professions individually written into the manuscript. This situation is unusual, because most codices (such as the Arenberg Gospels) containing professions only include blank formulae for communal use. Normally, the official could read it aloud so that the candidate could repeat it back phrase by phrase and fill in the personal details on the fly. Contrariwise, the Pontifical of St Loup forms a living, written record of the people comprising its social network.

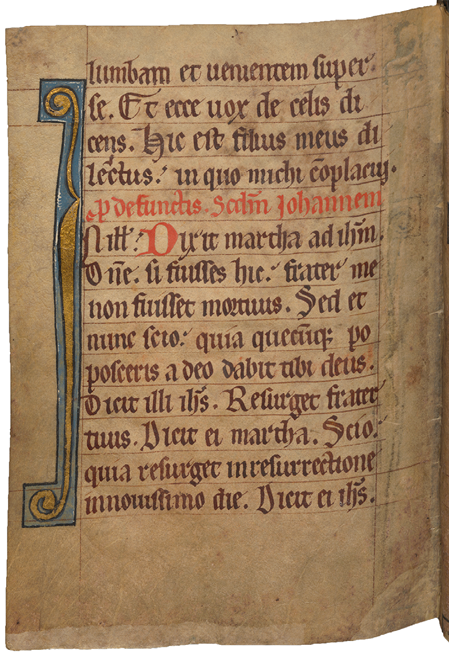

In fact, the Abbey of St Loup did move to blank formulae, but not until the fifteenth century. To see this change, one must turn to a different manuscript: the Gospels of St Loup. The manuscript was given to the Abbey of St Loup during the abbacy of Guitherus (1153–1197) by Henri the Liberal in honor of his son Henri (born after 1164). The main part of this manuscript, which is preserved in a fragmented state, therefore dates from second half of the twelfth century, and it, like the Pontifical of St Loup, has boldly painted initials (Fig. 24). The final folio (85) is an added singleton of thick parchment inscribed with professions in a bâtarde of ca. 1500 (Troyes, BM, Ms. 2275, fol. 85r; Fig. 25; see Appendix 1 for a transcription and translation of the text).

Fig. 24 Opening at the Book of Luke, Gospels of St Loup, ca. 1164–1197. Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2275, fols 4v–5r

Fig. 25 Folio added to the Gospels of St Loup, with an oath written ca. 1500 (and partially rewritten later). Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2275, fol. 85r

This added sheet within the Gospels of St Loup sharply departs from the professions of faith in the abbey’s Pontifical. The text in the Gospels is an oath, not a profession. It is anonymous: that is, each aspirant must supply his own name. It is to be read aloud, and not signed. To indicate his assent, instead of writing his name in the abbey’s Pontifical, he probably laid his hand on the Gospel, as suggested by the final sentence on the folio, “So help me God and by these holy Gospels of God.” This, however, cannot be definitely ascertained, as the swearing page has not survived within the manuscript, which now only contains the Books of Luke and John, with many folios cut out. Also telling is that part of the oath has been squeezed in by another hand (in italics in my transcription). This part specifies that the abbot also owes his allegiance to the pope and the kings of France. It may have been inscribed shortly after the Concordat of Bologna (1516)—an agreement between King Francis I of France and Pope Leo X, which allowed the king to appoint bishops to the French dioceses. This arrangement gave the French monarch a significant influence over the French clergy. More broadly, the squeezed-in passage demonstrates how the oath culture could be continuously adapted as the political climate changed.

Like the added texts in the Samson Pontifical and the Arenberg Gospels, the text added to the Gospels of St Loup suggests that the respective liturgical manuscript ripened the space for the oath to take place. The gestures have moved from physical mark-making to ephemeral gesturing, where the repeated touching of the Gospel manuscript may have registered cumulative abrasion that connoted tradition.

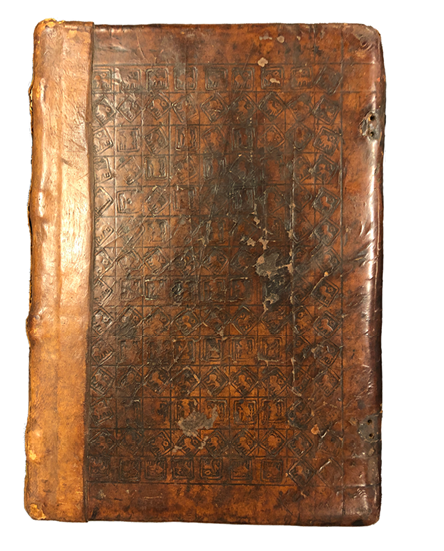

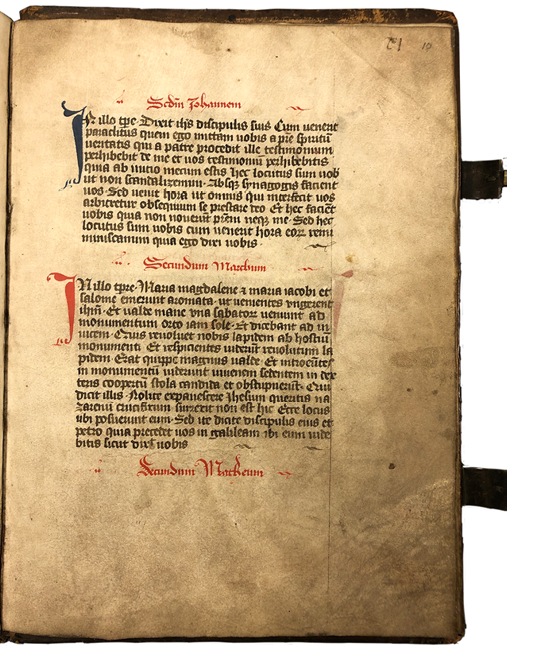

III. Expanding oath-taking: Confraternities in churches

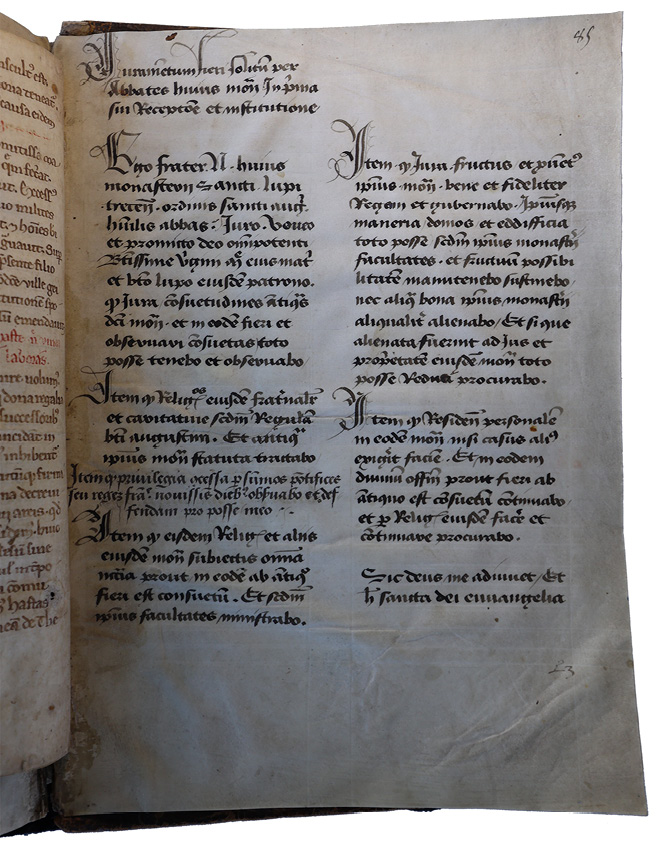

As the reach of religious influence extended beyond the confines of the monastery, in the thirteenth century derivative forms of oath-swearing took root in confraternities associated with particular churches. These oaths served as solemn commitments, binding members to their religious communities, doctrines, and responsibilities. When a man entered the priesthood or became a canon in the Chapter of St Servaas (Latin: Servatius) at the domkerk in Maastricht, he had to swear an oath to the Chapter of St Servaas, one of the most powerful organizations in the region of Limburg. The chapter may have formed as early as the ninth century to serve the needs of secular canons; it lasted until the end of the ancien régime in 1797.24 Canons, or secular priests, were distinct from monks in that they could own property, although like a monastery, the chapter provided apartments and communal meals for its members. Priests within a chapter formed a confraternity, or brotherhood, to whom they owed allegiance. Four manuscripts from the Chapter of St Servaas survive; these would have belonged to the group and not to individuals.25 The contents of, and marks of use in, its book of statutes reveal aspects of the priests’ rules and rituals, suggesting that the group was highly regulated but formed close bonds (HKB, Ms. 132 G 35).26 This book was made around 1430–50. Instead of writing the oaths in the blank interstices of a Gospel manuscript, as the canons of Cologne had done with the Arenberg Gospels (Morgan M.869), the canons in Maastricht created a new manuscript for this part of their public-facing administration. They bound their book in a red leather cover (like the books of privileges discussed in Vol. 1), possibly to distinguish it as an official oath-swearing manuscript. The blind-tooled leather is original, although the red dye has faded, the spine has been re-backed, and the clasps have fallen off (Fig. 26). The choice of red leather suggests that the makers of this book drew upon conventions of civic legal manuscripts to lend additional authority to their compilation of statutes.

Fig. 26 Front cover of the Statutes and Regulations of the Chapter of St Servaas in Maastricht. Tooled leather, fifteenth century. HKB, Ms. 132 G 35.

Books of statutes invariably contain legitimizing structures, such as an image of Christ Crucified with an osculatory target, or excerpts from Gospel manuscripts. The Maastricht book of statutes has an oath inscribed near the front of the manuscript, in the center of folio 3r (Fig. 27). Here, the text was arranged so that it could be headed by an image of the Crucifixion and tailed by an osculatory target painted at the bottom. The loose image of the Crucifixion, which has been pasted in, can be localized and dated on stylistic grounds to Utrecht ca. 1430, shortly before the main body of the manuscript was inscribed in Maastricht. The image was therefore not commissioned for this book, but its availability solved a problem for the scribe, who wanted to introduce an appropriately gilded and crafted image into the opening, so that Christ’s presence would form an umbrella of divine authority over the oath.27 The shape of the cross painted at the bottom of the page resembles consecration crosses inscribed or painted on the interiors and exteriors of churches, which were used in ceremonies including processions. The shape constitutes a call to corporeal action.The text reads:

Fig. 27 Opening of the Statutes and Regulations of the Chapter of St Servaas in Maastricht (Maastricht, fifteenth century), with an oath and a parchment painting (ca. 1430, Utrecht) depicting the Crucifixion pasted to the top. HKB, Ms. 132 G 35, fols 2v–3r.

Oath of the brother:

I, N, promise by my publicly offered faith, and I swear on these holy Gospels of God, physically touched with my right hand, that from this hour onward I will be faithful to the fraternity of priests of the Church of Saint Servaas of Maastricht. I will inviolably observe the Charter of Statutes of this brotherhood and all its statutes, whether ordered or yet to be ordered, which have not been changed, revoked, or removed, to the best of my ability. And in the affairs or business of the said brotherhood, I will not side against the brotherhood, and I will not reveal the secrets of the same brotherhood. So help me God and by these holy Gospels of God.28

The oath is intricately scripted as a speech act. It directs a ceremonial performance for the person to physically engage with this book, specifically touching it with his right hand. Bountiful fingerprints, concentrated in the lower lateral margin, suggest that many people touched the page while swearing the oath inscribed on it, apparently with their respective right hands.

Even though “these holy Gospels” are in fact a book of statutes, it apparently counts as “holy Gospels,” and the users have touched it as though it carried that weight. To some degree, it did: the scribe, to invoke the evangelists, has written the incipits of the Books of Matthew (fol. 4r), Mark (fol. 5r), Luke (fol. 5v), and John (fol. 6v) into the book immediately after the oath. These have also been furnished with author portraits of the evangelists. Users deliberately laid their hands on the lower corners of these openings, as the patterns of wear indicate. The lower corner of Matthew is especially smudged with fingerprints, and I suspect that this is so because Matthew is the first of the Gospel fragments after the oath (Fig. 28).29 Smudgy, darkened corners are consistent with a scenario in which the initiate, who was fully literate and therefore able to read his own oath on fol. 3r, would place his finger on the corner of the next folio (fol. 4r), and thereby make contact with “these holy Gospels” while still being able to read the relevant text. This situation contrasts with manuscripts stained at the top margin, which imply the presence of an initiate or oath-swearer to whom the book is proffered, and who is having the formula read to him rather than reading it himself. If my hypothesis is correct, this would also explain why there is also some darkening on fol. 3v, which would have rested on top of the initiate’s hand and brushed the tops of his fingers while he deliberately touched fol. 4r with the finger pads of his right hand. In the photographs, my hand not only holds the book open, but provides a sense of scale for the activities described here.

Fig. 28 Opening in the Statutes and Regulations of the Chapter of St Servaas in Maastricht, with the incipit of the Book of Matthew, with an author portrait, ca. 1450, Maastricht. HKB, Ms. 132 G 35, fol. 3v–4r

A late fifteenth-century hand has copied a second oath onto the otherwise blank space at the bottom of fol. 2v, opposite the repurposed Crucifixion image. This time, however, the oath is for a “Master of the Fraternity of Priests” (magistrum Fraternitatis sacerdotum), and to take this oath, the swearer would once again physically touch the statutes with his right hand, or one of the Gospel texts on the following pages. Once again, the initiate can read one page while touching another. Someone has inscribed a manicula, or “little hand,” which not only draws attention to the added oath, but also introduces another right hand to the proceedings.30

The folios of HKB, Ms. 132 G 35 measure 260 × 190 mm with a text block of 170x 130 mm. By choosing such a large format, the scribe has unburdened the initiate by providing him with large clear letters surrounded by plenty of space. He has also disambiguated the text by writing it with few abbreviations, which could be easily seen and pronounced aloud. The patterns of wear reveal further details about the audience and the context of the ceremony. Clearly the users could read the oath aloud themselves while standing at the bottom of the manuscript: it was not read to them. As they were joining the brotherhood of priests of the church or becoming the leader (magister) of the group, the audience for this manuscript was presumably literate.

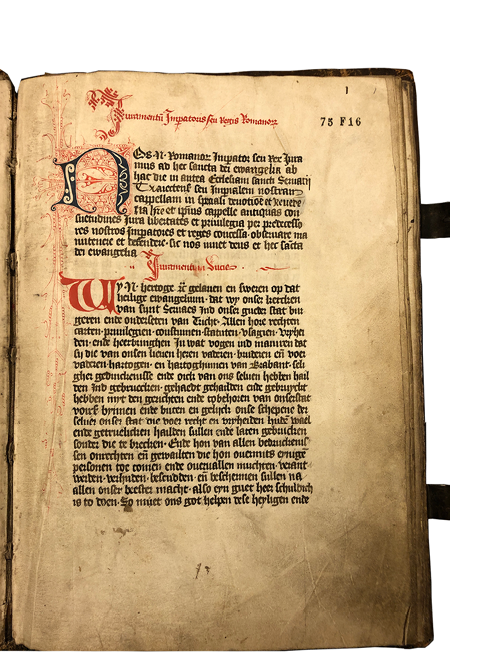

Fig. 29 First folio in the oath book of the Chapter of St Servaas, Maastricht. HKB, Ms. 75 F 16, fol. 1r

Fig. 30 Fore-edge and upper clasp of the oath book of the Chapter of St Servaas, Maastricht. HKB, Ms. 75 F 16

The Chapter also owned a manuscript containing dozens of other oaths (without statutes), for all those besides priests who owed loyalty to the Church of St Servaas (HKB, Ms. 75 F 16; Fig. 29).31 This manuscript has functional similarities with the example from the Chapter of St John in Utrecht, to be discussed in the next section. The function of HKB, Ms. 75 F 16 is conveyed by its size and appearance: this large manuscript contains only 13 folios but is bound in thick wooden boards with bosses and a decorated clasp (Fig. 30). In its unnecessarily heavy and ornate binding, it was used purely for ceremonial purposes: for publicly pronouncing oaths. Considering its function, it is surprisingly modestly decorated. The manuscript begins with oaths for emperors (in Latin) and dukes (in the vernacular, Middle Dutch), and also contains oaths for, inter alia, deacons, cantors, teachers (scholastici), treasurers (thesaurarij), canons, cellarers, chaplains, guardians of the relics, and roydregeren (rooidragers in modern Dutch), who played a ceremonial role in processions and feasts, and preceptors of feasts and anniversaries. Some of the oaths are in Latin and some in Middle Dutch, depending on the audience, and all require the subject to “lay his right hand on these holy Gospels,” except one: the roydregeren have to put their hands on a cross to say their oaths (rub: Tunc ponat manus ad crucem et dicat, fol. 7r). Apparently, those fulfilling this important ceremonial role brandished an additional layer of spectacle that distinguished their inaugurations: for them, a crucifix served as the prop sealing the speech act. The master of ceremonies enjoyed the greatest ceremony of all. The final folio of the original, fifteenth-century text, like other manuscripts designed for official purposes, has abbreviated copies of the Gospels (Fig. 31). Once again, their presence infuses the inert matter with the divine, thereby turning the manuscript into one charged for oath-swearing.

Fig. 31 Final original folio of the oath book of the Chapter of St Servaas, Maastricht, with abbreviated texts from the Gospels. HKB, Ms. 75 F 16, fol. 10r

Comparing the two oath-taking manuscripts from the Chapter of St Servaas reveals much about the brotherhood. Whereas HKB, Ms. 75 F 16 accentuates adherence to a structured hierarchy, HKB, Ms. 132 G 35 incorporates both hierarchical submission and allegiance to the fraternity. The brother pledged both vertical and horizontal bonds.

HKB, Ms. 75 F 16 can also be compared with the Arenberg Gospels used by the church in Cologne, discussed in Volume 1, Chapter 3, and above in this chapter. The Maastricht manuscript contains the same kinds of oaths as the Arenberg Gospels, but in fact the two churches have approached the project from opposite tenets. In Cologne, the leadership began with an eye-catching, centuries-old, colorful imported Gospel manuscript, and then filled in the empty spaces with oaths to be read while touching the Crucifixion miniature, the prop that sealed the speech acts. In the Maastricht manuscript, the scribe started from scratch, creating a new manuscript rather than repurposing an existing one. Simply including the Gospel texts made this manuscript a worthy prop.

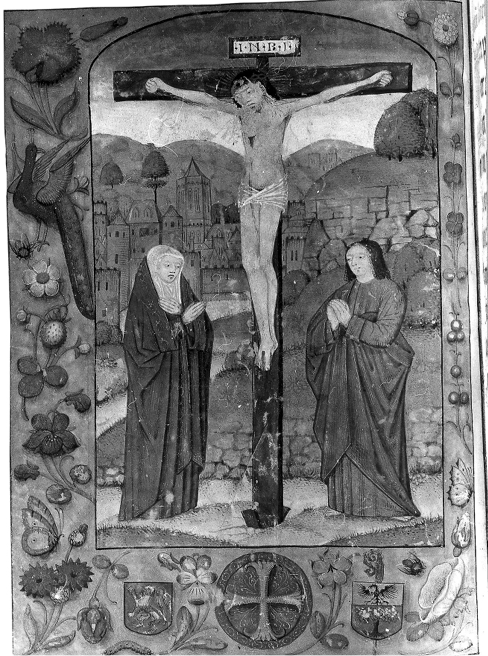

There are as many solutions to the problem of how to publicly forge meaningful cohesion between group members and adherence to regulations as there are manuscripts produced for this purpose. Such manuscripts have not previously been studied as a group, and a Europe-wide systemic survey of oath manuscripts would certainly reveal patterns over time and across space, which is beyond the scope of this project. However, I will consider a final example in this category, a manuscript made in the sixteenth century that contains statutes as well as formulas for oaths for members of the Abbey of St Bavo in Ghent. Here the brothers have chosen a strategy we have seen before for instilling the book with a sufficient supernatural numen: they have inserted a Crucifixion page of the sort made for missals (Fig. 32). Signs of wear on the represented wood of the cross, and on the torso of Christ, indicate that it was touched, although not heavily. Oath-swearers could lay a hand on the full-page Crucifixion miniature, or they may have also laid their hands on the coats of arms that flank the osculatory target at the lower margin. Considering that they have not dampened or dislodged the paint, they apparently did not kiss or wet-touch it.

Fig. 32 Crucifixion miniature, mounted in a book of oath fomulas, statutes, and lists of names from the Church of St Bavo, Ghent, sixteenth century. Ghent, Church of St Bavo. KIK nr 88571

What is telling in this manuscript, however, is that members had their names listed in the book following their oath-taking ceremonies. Not only did the rituals and the ritual objects transform the people who participated in them, but those people also indelibly changed the ritual objects. They left their hand- and fingerprints in the manuscript and changed the text by adding their names. They became co-creators of the manuscript surface.

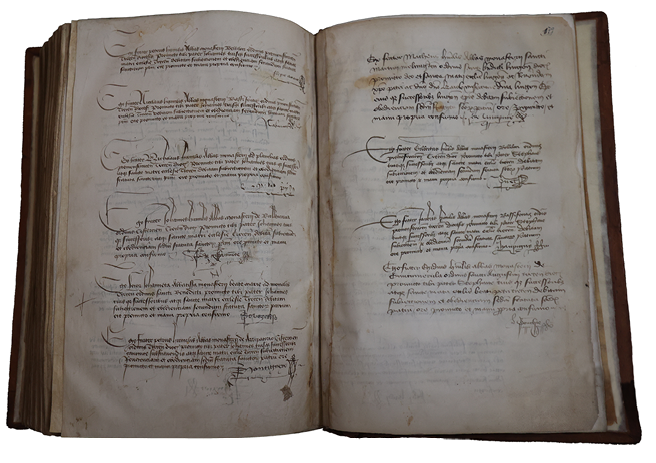

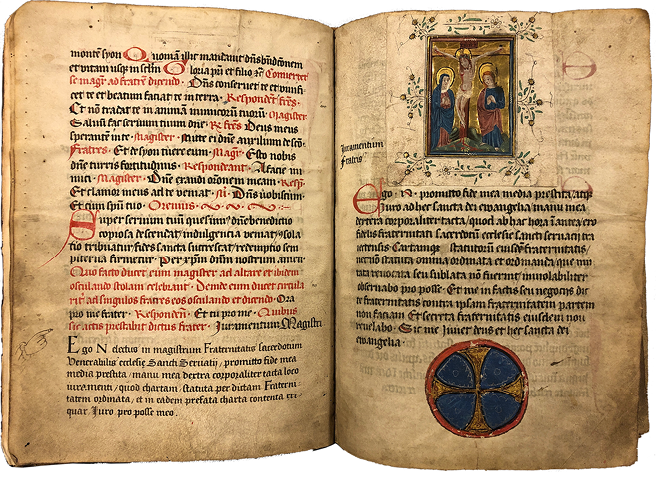

IV. Out of the church and into the castle

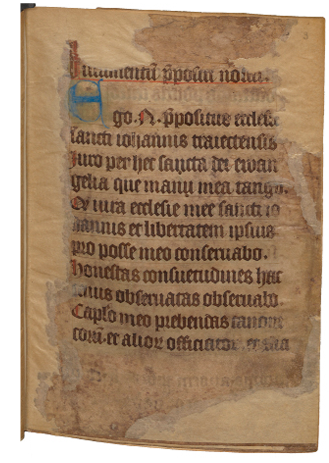

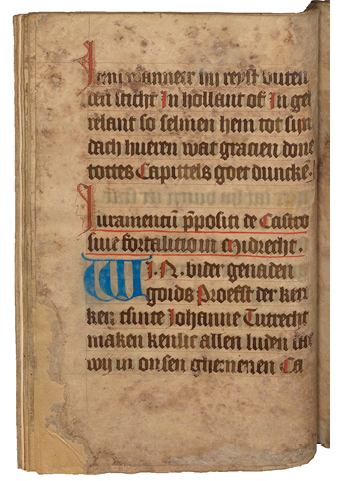

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, laypeople—and not just aspirants of confraternities—increasingly took oaths of the sort formerly designed for clergy, where the oaths would create a class of members with special privileges and obligations. A material witness survives in the form of an enhanced Gospel manuscript used by the Deaconate (Chapter) of St John in Utrecht (UUB, Ms. 1590; Fig. 33 and Fig. 34).32 This manuscript contains a carefully tailored selection of oaths for religious and laypeople and reveals some of the inner workings and power dynamics operating among clergy, nobles, and courtly attachés.

Fig. 33 Folio with an oath in Latin for the provost of the Chapter of St John, added in the fifteenth century to an (incomplete) Evangelistary from the thirteenth century. Utrecht, UB, Ms. 1590, fol. 3r

Fig. 34 Folio with an oath in Middle Dutch for the governor of the castle to pledge to the Chapter of St John, added in the fifteenth century to an (incomplete) Evangelistary from the thirteenth century. Utrecht, UB, Ms. 1590, fol. 21v

Conrad, the bishop of Utrecht from 1076–1099, had granted to the Chapter of St John several parishes located between Utrecht and Amsterdam. These parishes paid rents and were beholden to the Chapter. As a result, the Chapter controlled various castles, including the Kasteel de Haar outside Mijdrecht. (This castle, which now hosts glamorous celebrities, burned in the fifteenth century and was largely rebuilt in the sixteenth and again in the nineteenth.) Some of the added texts in UUB 1590 relate to the governance of castles, for which specific oaths were drawn up. The oaths require physical interaction with this manuscript, alongside certain hand gestures and utterances.

UUB 1590, like the Arenberg Gospels, was made in multiple campaigns of work, demonstrating that it was in use for several centuries. The core (fols 32–101r) dates from the thirteenth century and contains an incomplete Evangelistary (Fig. 35).33 In the fifteenth century, the function of the manuscript changed. What had been an Evangelistary, to be used by a priest while performing Mass, became an oath-swearing manuscript for use by members of the Chapter and laypeople in its orbit. It is possible that a 200-year-old Gospel manuscript was chosen for this purpose because it—like the Arenberg Gospels when they changed function—burgeoned with several hundred years of history and was illuminated. In other words, it fit the bill.

Fig. 35 Folio from the base manuscript, a thirteenth-century Evangelistary. Utrecht, UB, Ms. 1590, fol. 98v

To give it a new function as an oath-taking prop, several quires were added to the front of the manuscript, now comprising fols 3–31. These new folios received the oaths, listed in a clear hierarchical order, beginning with one for the provost of the church. (The oaths are transcribed and translated in Appendix 2.) The fifteenth-century scribe made an effort to duplicate the page design from the thirteenth-century core. Namely, he ruled the folios for 15.6 × 11 cm, and then filled them with 14 equally spaced horizontal lines. However, because the thirteenth-century scribe wrote on the top line, while the later scribe followed the newer habit of avoiding the top line, the old section has 14 lines per folio and the later section only has 13. The later scribe therefore maintained the large size of the letters from the original core but could not escape the scribal habits of his age. Furthermore, the later scribe also tried to duplicate the older script as best he could, with a textualis that floats about 1 mm above the ruling. It is as if the later scribe were trying to create a tradition as old as the core of the book, as if both the Evangelistary and the oaths reached deep into history and formed a long, legitimating tradition.

Appended to the oath for the provost is a long statute further detailing the responsibilities of the office. Three features of the text are important to the current discussion: first, that the candidate mentions in a meta-textual moment “these holy Gospels that I touch with my hand.” In so doing, he is referring to a gesture he makes while reading his oath: that of touching this very manuscript. In this way, the function of UUB 1590 is like that of the Arenberg Gospels. Unfortunately, Utrecht 1590 is severely damaged, and has been restored in a heavy-handed way, so that all of the frayed margins have been filled in with modern paper. One can speculate that oath-swearers touched and darkened the lower margins, but one cannot be certain.

Second, this and the other oath texts are appended to the front of the Gospel manuscript, meaning that during swearing, the Gospel manuscript would also be physically underneath the candidate’s hand, so that he would not only be touching the oath, but also the Word of God. Third, this manuscript is in terrible condition. It has undergone some water damage, but that only explains part of the degradation: it has also been handled so vigorously that it is now in tatters. The manuscript has been rebound and now contains several blanks. It is possible that it, like the Arenberg Gospels, once contained a Crucifixion page.

After the oath for the provost (prepositus), next in the hierarchy is an oath for the canons of the Church of St John (11v–13r); then the oath for the vicars, or episcopal deputies (13r–15v); for the notaries (15v–16r); for the rector of the school (iuramentum rectoris scolarium) (16v–18r); for the messenger (iuramentum nuncii suie sculteti nostril) (18r–21v); for the provost of the castle or fortress in Mijdrecht (iuramentum prepositi de castro sive fortalitio in Midrecht) (21v–23r); and for the castellani in Mijdrecht (23v–25v). These are the petty-aristocratic castle-lords, who take the oath collectively.34

The oaths for the messenger, the governors, and castle-lords are written in the vernacular—Middle Dutch—rather than in the Latin of the other oaths, underscoring their departure from the norm. The oath for the provosts of the castle at Mijdrecht is given in the plural, “we,” rather than the singular “I.” This grammatical choice suggests they were to take their oaths in unison, and the text specifies that they put their hands on their chests (instead of touching the book) as they swear to safeguard the castle and ensure no harm comes to it. The final oath in this group, apparently read aloud to “the castellani,” is addressed to “Everyone who shall see this brief, or hear it read” (fol. 23v). These people swear to protect the castle, and state “I have laid my hand on this brief, and I swear by my life with my hand, with mouth, and with upheld fingers.” Here there is no mention of touching the Gospel manuscript; instead, their own breast takes the place of the book. For the more secular roles within the castle, the various officials swear their allegiance to the Chapter of St John but do so with the written and wax-sealed charter, rather than with the Gospel manuscript.35 Reflecting a meticulous order, these oaths are organized hierarchically, beginning with the individuals who were to read their oaths in Latin while touching the book, to singular individuals reading in the vernacular, to groups of people having the oath read to them, who do not necessarily have access to the manuscript.

Yet another addition was made to the front of the manuscript (fols 1–2) to accommodate an oath for the provost and archdeacon, added in the sixteenth century. This new role must have superseded the role of provost, or perhaps the role of provost was expanded to encompass the tasks of the archdeacon, as well. Around that time, the oath for “our deacon” was added to fol. 25v, where there had been some blank space. These additions demonstrate that the manuscript was in constant use, and that it needed to be updated to reflect mutations within the Chapter of St John. Where was this manuscript used during its long tenure? It probably stayed in the Chapter of St John most of the time, and perhaps was brought to Mijdrecht so that the oaths from the various officials working in the castle could be taken. Transporting the manuscript safely from the city to the castle would have been one errand the deacon assigned to the messenger, whose duties are so clearly laid out in the document.

With the copying of oaths directly into existing liturgical books, several things shifted. Each candidate no longer made (or commissioned) a singular professional charter; the charters could therefore no longer be collected, sewn together, and brandished as a history of an institution’s leadership. The formulae to be recited became standardized, since the anonymized form was not mutable. The context changed, from a ceremony in which the candidate signed his cross at the bottom of a charter, to one in which he interacted physically with a liturgical book, sometimes a Pontifical but usually a Gospel manuscript, which was by default present. The ritual morphed from a profession to an oath, from an individualized into a collective experience, and from active to passive mark-making.

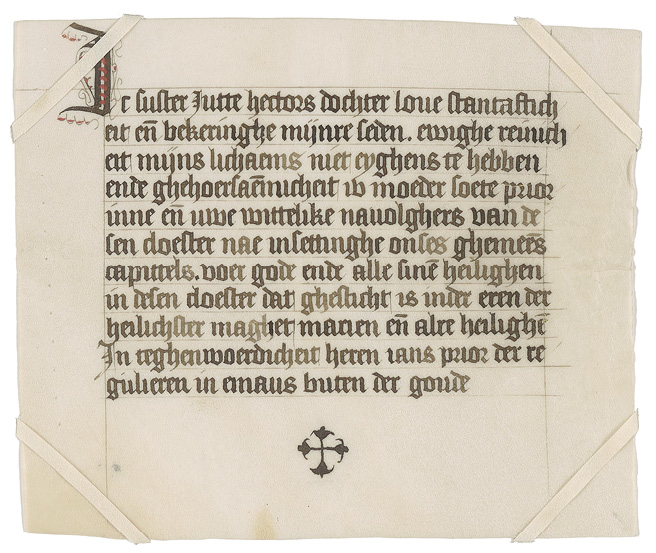

V. Testaments in Mariënpoel

The habit of writing individual, named professions of obedience had begun in eighth-century England, had an upsurgence after the Norman Conquest, and was largely replaced in England and on continental Europe by communal oaths sworn from books containing formulae. In the fifteenth century, the practice of producing individual named professions of obedience returned, this time in a different context. Sisters in a convent in Mariënpol outside Leiden (Klooster Mariënpoel te Oegstgeest) wrote professions of obedience in such a way, I believe, that their very writing formed part of their meaning. These documents, written individually on small sheets of parchment, testified to their profession when they entered the convent. A significant number of them—54 in total—survives from this convent, from the mid-fifteenth through the mid-sixteenth century.36 Although most of them are undated, Ed van der Vlist has sequenced them chronologically based on other records from this convent, and I rely on his findings.37 Most were penned by girls who were 11 to 14 years old. The earliest surviving testament is from Jutte Hectorsdochter [uten Leen] (1416–1501) (Fig. 36), whose testament reads:

I, sister Jutte Hectorsdochter, pledge stabilitas loci and to convert my limbs, to keep my body pure in perpetuity, to forsake possessions, and I pledge obedience to you, sweet mother prioress and your white underlings from this convent, which was founded in honor of the most holy virgin Mary and all the saints, in the presence of lord Jan, prior of the regular canons in Emmaus outside Gouda.38

Fig. 36 Profession of obedience of Jutte Hectorsdochter. Leiden, ca. 1428. Leiden Archive (RAL Kloosters 885), blad 9b

The term “white underlings” probably refers to the white woolen gowns the sisters wore. One can see the resemblance between this profession and those made by the bishops and abbots pledging allegiance to Canterbury from the ninth through twelfth centuries and beyond. However, there are some important differences. Jutte Hectorsdochter made this profession ca. 1430 when she was about 14 years old, not when she was in her full adulthood entering the upper tiers of ecclesiastical management. It is likely that she copied the profession herself, in slow and careful textualis script. Her inconsistent ink saturation documents her struggle. She decorated the initial in the same dark brown ink, with a small amount of red. She may have entered the convent some months before she made this vow and learned to write during the interim. The testament would therefore not only be a solemn vow, but also a demonstration of her ability to read and write, and to work in the scriptorium.

The wording in the 54 surviving testaments is similar to that of the oath taken by members of the Chapter of St Servaas (discussed above). And in both cases, a cross with decorated finials, similar to an osculatory target on the Canon page in a missal, punctuates the bottom of the sheet containing the oath. There are several very important differences in the Mariënpol and Maastricht oaths, however: the former comprises loose sheets, each produced individually by a single sister, who swore her profession on the sheet she made herself, with her own name listed at the top; the latter comprises a communal volume, in which each brother in Maastricht replaced the word “nomen” with his own name during an oral performance. Clearly the sisters’ act of penning the sheets was an essential part of their declaration. In this way, the sisters at Mariënpol exceeded the efforts of the male abbots- and bishops-elect from Canterbury, who had had their professions written by professional scribes, and then merely filled in their names and crosses. For the Netherlandish women, the charters documented their ability to write, to make complex layouts, and to execute elaborate flourishes.

One can imagine that the ceremony of profession for the sisters at Mariënpol would have involved writing the testament, dressing in a new white habit, pronouncing the testament in the presence of the convent’s prioress and the supervising male prior, and then sealing the vow by touching the cross. These were far too complex to inscribe during the ceremony, as the Canterbury bishops had done. The position of the cross on the page was borrowed from the layout of the earlier professions of obedience, but the cross also takes on the qualities of an osculatory target on a Canon page, where the marginal cross is often highly ornate, especially in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries (Fig. 37). Concomitant with the borrowing of the formal qualities of the osculatory target, the ritual may have also borrowed a kissing gesture from the liturgy. These symbols and gestures would have given the girls’ performance gravitas and legitimacy steeped in Christian liturgical ritual.

Fig. 37 Opening of a missal at the Canon, missal of the Nijmegen Bakers’ Guild, 1482–83. Nijmegen, Museum Het Valkhof, Ms. CIA 2, fols 125v–126r.

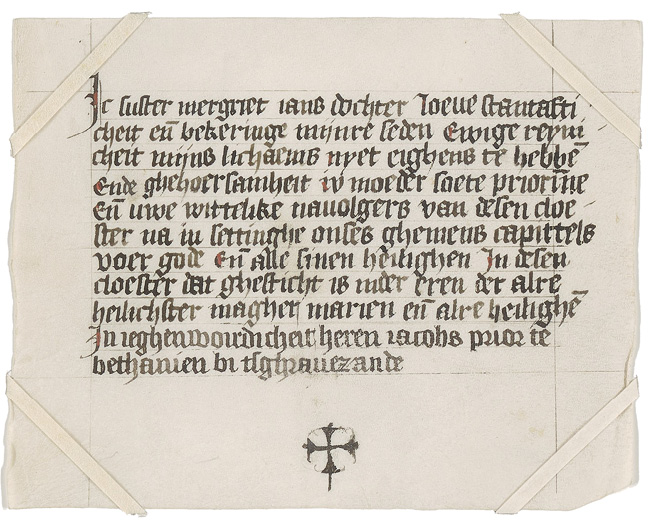

Across the ten decades of these briefs, the girls’ testaments follow a similar formula, although they are not copied precisely from a standard exemplar. The next oldest testament, from Mergriet Jansdochter (d.1504), was written ca. 1430 (Fig. 38). This time, the girl struggled with her penmanship, especially with pen angle and letter spacing, and she reduced the decoration to just a few strokes of red. What she produced was a testament to her writing abilities as well as to her faith. What remained constant was the decorated osculation target at the bottom of the age, the symbol for ratifying the vow.

Fig. 38 Profession of obedience of Mergriet Jansdochter, Leiden, ca. 1428. Leiden Archive (RAL Kloosters 885), blad 10a

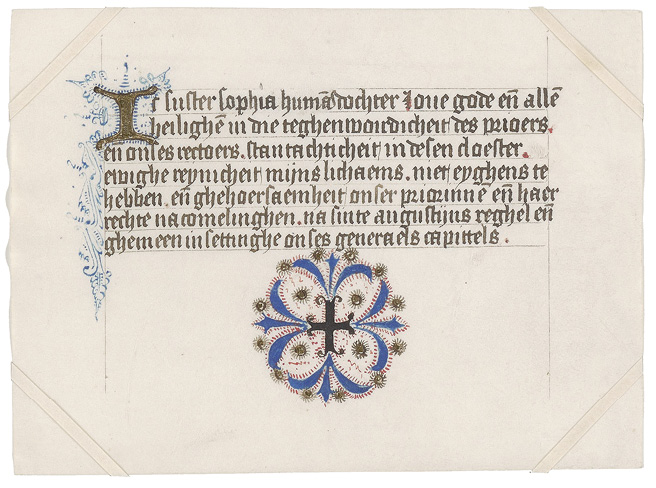

Later in the fifteenth century the charters became more decorous. Barbara, meyster Philips Wielantsdochter (d.1506), penned one in the 1490s where she has heaped layer upon layer of festooning red and blue scrollwork onto the osculatory target so that it has become a dizzying abstract design (Fig. 39). It is impossible to know whether this florid attention to the object to be touched also accompanied a more flamboyant, theatrical performance of touching it. What is clear is that the crosses on all 54 sheets look fresh and pristine. This is presumably because each has only been touched a maximum of one time by one girl during one ritual of profession. These sheets fulfill a role similar to the osculatory target represented in the manuscript for the Chapter of St Servaas, but here each girl has her own sheet rather than swearing on the group’s collective manuscript. Distributing the crosses fulfills a number of desiderata: it means that each girl must demonstrate her proficiency in writing before she can profess, and it generates a personalized memento for each newly minted sister.

Fig. 39 Profession of obedience of Barbara meyster Philips Wielantsdochter. Leiden, 1490s. Leiden Archive (RAL Kloosters 885), blad 19a

Exceptions to this pattern occur in a few of the testaments, including that of Sophia, Humansdochter (1543 - after 1589), who re-used a charter made in the 1510s (Fig. 40). The words “Sophia Humans” constitute a palimpsest. She erased the previous name with a knife and scraped the ruling along with the letters. She left the word “dochter” (daughter) on the page so that she would not have to rewrite it. By erasing one of the other sister’s names, was she committing damnatio memoriae? Perhaps she was merely demonstrating some continuity with the past while saving herself some labor.

Fig. 40 Profession of obedience re-used by Sophia Humansdochter. Leiden, 1510s, with additions. Leiden Archive (RAL Kloosters 885), blad 25a

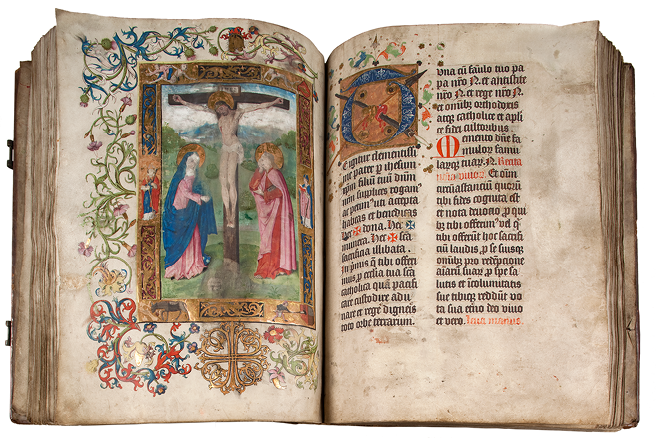

While the Augustinian sisters at Mariënpol showed evidence of having made their testaments themselves, an Augustinian canoness in the nearby convent of St Anna in Delft eschewed the homespun and apparently commissioned an elaborate note of profession, which she then stored in a breviary (Fig. 41). Her full name is given in the accompanying oath: “I, sister Willem Lord Jan van Egmont’s daughter” (Ic suster willem heer Jan van egmonts dochter). She was the daughter of Jan III van Egmont (1438–1516).39 With its strewn-flower borders distributed across panels, its gold ground, and its intense colors, the sheet may have been painted by the Masters of the Dark Eyes, a group of artists who supplied the painting for Books of Hours and prayer books throughout the region now called South Holland.40

![Ornate profession of obedience of Sister Willem, “Lord Jan van Egmont’s daughter,” incorporated into a breviary, suggesting that wealthy women might have hired scribes and illuminators to produce their professions of obedience. Delft, Prinsenhof, [no number], fols 1v–2r.](image/Rudy_041_Prinsenhof_Brevier_van_Wilhelmina_van_Egmond_03_copy.jpg)

Fig. 41 Profession of obedience of Sister Willem, “Lord Jan van Egmont’s daughter.” Parchment painting (after 1468) in its current manuscript context, bound into a breviary made at the convent of St Agnes in Delft, ca.1440–60. Amsterdam University Library, Ms XXX E 117, fols 1v–2r

Each of these testaments appears fresh (except for those whose owner’s name has been written over an erasure). The osculatory targets all appear fresh. They have probably only been used once each, at the moment of publicly declaring the profession. Each girl or woman has her own target, emblazoned on her own personal charter, ratifying her own personalized vow. In this case, these are objects each touched one time by one person (as opposed to objects touched once each by many people, as in the case of Gospel pages on which multiple people swore, or objects touched multiple times by the same person, as in the case of certain images touched daily out of habit and/or devotion).

The sisters were not only copying an exemplar when they penned their own sheets: they were also forming themselves. They did this not only by shaping their bodies and hands to wield a pen in order to write, but also by molding their emotions and sensibilities to become one of a group. Their formation was partly defined by penning their profession charters. They then shaped their bodies in another way as they underwent a ritual involving the charter, which would have required making physical contact with the area of the charter centered in the lower margin and decorated with the best, most symmetrical, neatest penwork they could muster. The testaments of the Mariënpol sisters derived their significance contextually—solely for the girls crafting them, within the specific convent they were about to join. That the girls made the sheets themselves would have demonstrated their complicity in this arrangement and their willingness to be bound to the convent for life.

VI. Hinged thinking: A civic context

Manuscripts that needed to project authority, group membership, or obligation could draw on the structures of two kinds of manuscript at the center of ecclesiastical authority—the Gospel and the Missal—to lend gravitas to texts and rituals. Moreover, such books could contain oaths, privileges, and other obligations ratified under the dominant cultural symbol for justice. These borrowed the language and written structures of secular contracts. Such practices formed the social glue building group membership, keeping promises, and minimizing uncertainty.

Rituals were crucial in establishing social relationships, especially those centered around trust and protection. I have sketched a progression over time, from oral statements to professions, then from vows to formulas. This chapter has spotlighted manuscripts that helped to impose obedience within bishoprics, chapters, and convents through specific handling practices. The types of manuscript-objects have been unusual, because particular social settings compel their utility.

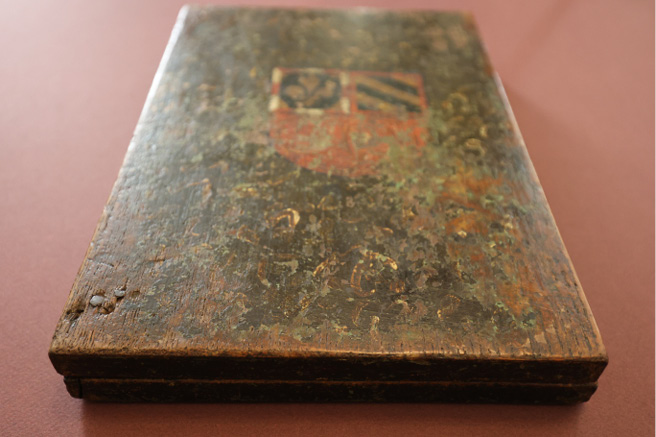

Each of the examples in this chapter tells of a local solution to the problem of ensuring a less uncertain future by adding gravitas and a perceived supernatural presence to speech acts. This gravitas could be achieved by repurposing an older Gospel manuscript that effused the gravitas of antiquity for swearers to touch. Some achieved this by inventing elaborate rituals involving signing parchment letters at an altar. The city of Dijon achieved this in a novel way by commissioning a swearing object: a diptych that looks like a book in its closed state (Fig. 42). Like the swearing manuscript that belonged to the Church of St Servaas in Maastricht discussed above (HKB, Ms. 75 F 16), the Dijon diptych is more binding than book. Made in 1488, the diptych is painted marbled green to turn the wooden boards into marble, thereby lending the object the valor and antiquity associated with carved stone. An escutcheon at the center of the faux marble slab presents the arms of the city. Hands opening and closing the diptych for centuries have worn the paint away. It was used in an annual ceremony when the mayor of Dijon pronounced his oath in front of the Church of St Philibert, a twelfth-century building that was also home to the informal guild of grape-stompers (or “purple asses”). This spot is in the former cemetery of the Cathedral of St Bénigne and is now a parking lot (Fig. 43). This oath-swearing practice continued until the French Revolution.

Fig. 42 Evangélière of Dijon, 1488; closed state. Painted wooden boards, hinged. Archives municipales de Dijon, lay. 5,72 (B 18)

Fig. 43 Site where the Mayor of Dijon swore his oath until the French Revolution

Opening the diptych reveals parchment sheets, each with an image: Christ Crucified on the left, and the Pietà on the right, with the first fourteen lines of the Book of John inscribed around them (Fig. 44). The object, when closed, measures 314 mm high, 220 mm wide, and 38 mm thick in its closed state. At 444 mm wide in its open state, it would have been easily visible from a distance of four or five meters in the public space in front of the Church of St Philibert. The modern archival box in which the object is now kept—in the Archives municipales, not far from the Church of St Philibert—does not have the item’s number but is inscribed with the word “Evangélière.” In other words, it is known as a Gospel, even thought it does not contain the full Gospel texts but only the beginning of John. It is similar to the oath book of the Church of St Servaas (HKB, Ms. 75 F 16) discussed above, in that a giant binding frames only a brief document; moreover, in both cases, a highly abbreviated Gospel text suffices as “these holy Gospels” on which to swear. Just a snippet of the Gospels is sufficient to call something a “Gospel” for ceremonial use.

The Dijon Evangélière functioned the way a Gospel manuscript functioned: for lending gravitas to oaths in the secular context of local government. Accordingly, the arms of the city of Dijon appear four times, twice on the exterior of the object, and twice inside. Anyone using, holding, or opening the object can hardly avoid touching the coat of arms of the city. The civic ritual borrows from the ecclesiastic one by heaping the civic symbols on a simplified Gospel form.

Fig. 44 Evangélière of Dijon, 1488; open state. Inscribed and painted parchment sheets mounted to wooden boards, hinged Archives municipales de Dijon, lay. 5,72 (B 18). Photo: author

Not only the exterior of the diptych, but also its interior has signs of having been touched. Specifically, the images on the interior are shiny, having been burnished with dry fingers. There is no evidence that they were wet-touched. I have photographed them from an oblique angle to capture their hand-polished sheen (Fig. 45). Like other items in this chapter, this object crosses the boundary between charter and book, opening in a hinged way like a codex but presenting two small pieces of parchment.

Fig. 45 Evangélière of Dijon, open state, photographed in raking light. Archives municipales de Dijon, lay. 5,72 (B 18)

As these examples have shown, the oaths, often documented in intricately crafted manuscripts, were not just words. They were physical, tangible affirmations of faith and allegiance. They had a (semi-)public role. The very act of placing one’s hand on a page, the palpable feel of the parchment, and the intentional touch on images or words all played a role in making the oath a sensory experience. This chapter has shown that witnessed promissory statements permeated medieval culture but were reinvented continuously to reflect specific needs. These statements used an oath and gesture formula, whereby the swearing objects shifted across multiple permeable conceptual membranes: from public to private, from charter to codex, single use to multiple use, religious to civic. Many medieval rituals of bondage not only borrowed features from earlier practices but also sought legitimacy from the tangible presence of the Gospel and the enduring nature of parchment. These qualities, including the perceived durability of the physical substrate of parchment, continue to play a role in oaths as they grow to encompass other social groups and brotherhoods.

1 Michael T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307, 2nd ed. (Blackwell, 1993), makes this argument, finding evidence in many domains of European culture.

2 Michael Richter, Canterbury Professions (Devonshire Press, 1973).

3 The practice of episcopal professions to archbishops ended in 1596 when Pope Clement VIII required bishops to profess obedience exclusively to the pope. See Richter (1973, p. xi).

4 For the professions of abbots, see C. Eveleigh Woodruff, “Some Early Professions of Canonical Obedience to the See of Canterbury by Heads of Religious Houses,” Archaeologia Cantiana, 37 (1925), pp. 53–72. https://kentarchaeology.org.uk/node/10461; however, his transcriptions and facts should be treated cautiously.

5 Richter (1973) edited all of the surviving profession charters in England. Many of them survive in the Canterbury Cathedral Archives, in addition to one manuscript in the British Library, Cotton Ms. Cleopatra E i (transcribed in the twelfth century). The classification marks Richter mentions are no longer valid. Since his study, the CCA has reorganized the professions of obedience, so that the 29 charters of abbots appear in approximate chronological order from 1148–1289 under the classification mark “Chartae Antiquae A/41.” The 170 charters of bishops-elect, dating from 1086–1289, are under the classification mark “Chartae Antiquae C/115.” Enrolled copies of professions of obedience, copied in contemporary hands from 1086–1160 (plus one dated 1420), are still stitched together, and bear the classification mark “Chartae Antiquae C/117.” These documents also include professions of obedience not represented among the loose charters, and they also contain other records. Based on palaeographic evidence, Neil Ker, English Manuscripts in the Century after the Norman Conquest (Clarendon Press, 1960), considered the enrolments to have been transcribed shortly after the bishops’ consecrations.

6 Richter (1973, pp. 28–29) transcribes these professions of obedience; they are preserved in LBL, Cotton Ms. Cleopatra E I, fol. 49r, and fol. 28r–28v, respectively.

7 Transcribed in Latin in Richter (1973, p. 32).

8 “Ego Thomas ecclesie de Boxleia electus Abbas promitto sancte Cantuariensi ecclesie et tibi reuerende pater Teobalde Archiepiscope ac totius britannie primas, atque apostolice sedis legate tuisque successoribus canonicam obedientiam quam manu propria signo crucis confirm o +” (Canterbury Cathedral Archive Collection, Chartae Antiquae A 41/2).

9 Woodruff (1925, p. 55) mistranscribes the date as 1153.

10 “Unus post alium eat ad altare et legant professionem. Postquam perlegerint, ponant professionem super altare et faciant crucem cum incausto super cedulam. Uideat magister eorum ut habeat ibi incaustum et pennam. Postquam fecerint crucem in cedula, tradant cedulas in manus abbatis et osculentur manus eius genibus flexis. Tunc tradet abbas cedulas sacriste.“ From LBL, Cotton Ms. Claudius C. ix, fol. 186r, “Forma professionis noviciorum in monasterio Abendonensi,” quoted in Richter (p. xxi), where it is erroneously given as fol. 118r). This text, for the Abbey of Abbington, dates from the late thirteenth century.

11 Richter (1973, p. xix).

12 See Richard Gameson, The Earliest Books of Canterbury Cathedral: Manuscripts and Fragments to c.1200 (British Library Board, in association with the British Library and the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury, 2008).

13 Richter (1973, pp. 46–47).

14 See Volume 1, Chapter 4.

15 For the Profession of Bernard, elect of St David’s (19 September 1115) and the profession of Geoffrey de Clive, elect of Hereford (26 December 1115), see Richter (1973), pp. 37–38.

16 For a bibliographical survey of English Pontificals, including a history of their development from the eleventh century onward, see J. Brückmann, “Latin Manuscript Pontificals and Benedictionals in England and Wales,” Traditio, 29 (1973), pp. 391–458.

17 Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 146. Images and updated bibliography can be found here: https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/catalog/wy783rb3141. The manuscript is paginated, not foliated.

18 Richter (1973, p. 109) transcribes them.

19 For images and bibliography, see https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=cotton_ms_galba_e_iv_f001r

20 I discuss this manuscript more fully in Vol. 1, Chapter 3.

21 See https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc734105. It is nearly identical to the profession of Herewine, written in Canterbury in 814 or 816 (Richter, 1973, no. 9), demonstrating a strong exchange between English and Continental practice, with the example from Canterbury providing the model for the one at Corbie a century later.

22 Pontifical of St Loup, twelfth century with later additions. Troyes, Trésor de la Cathédral, Ms. 4. See Françoise Bibolet, “Serments d’obéissance des abbés et abbesses a l’Évêque de Troyes (1191–1531),” Bulletin philologique et historique (1959), pp. 333–343. V. Leroquais also notes the professions in Les Pontificaux manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques de France, Vol. II (1937), pp. 396–402.

23 Ego N, humilis abbas [monasterii de X], [ordinis X, Trecensis diocesis], sancta matri ecclesie Beati Petri Trecensis et tibi, pater N tuisque successoribus, secundum sanctorum Patrum instituta, debitam, subjectionem et obedientiam ore promitto et manu propria confirmo.

24 In the nineteenth century, religious brotherhoods were founded in various cities of the Catholic parts of the Netherlands, including Maastricht and Hasselt, and they produced books of statutes modeled on medieval precedents, which were printed as Broederschap der gedurige aanbidding van het allerheiligste sacrament der autaars, opgerigt in 1768, in de parochiale kerk van S. Jacob en thans berustende in de hoofd-parochiale kerk van den H. Servatius, te Maastricht (Leiter-Nypels, 1845); Broederschap der gedurige aanbidding van het allerheiligste sacrament: opgericht door Zijne Hoogheid Carolus, Prins Bisschop van Luik…, en opgericht te Hasselt (Overijssel) op Pinxterdag 1833 (J. W. Robijns, 1835).

25 P.J.H. Vermeeren, “Handschriften van het kapittel van Sint Servaas,” Miscellanea Trajectensia (1962, pp. 181–192), identified four extant manuscripts beloning to this chapter: a fourteenth-century Bible in a chemise binding (HKB, Ms. 78 A 29); a missal with a calendar for Limburg (HKB, Ms. 78 D 44); Statuta et ordinationes fraternitatis sacerdotum ecclesie S.Servatii Traiectensis Leodiensis diocesis (HKB, Ms. 132 G 35); and a book of oaths in Middle Dutch and Latin (HKB, Ms. 75 F 16, discussed below).

26 HKB, Ms. 132 G 35. For a description and bibliography, see https://bnm-i.huygens.knaw.nl/tekstdragers/TDRA000000003597

27 For a discussion of this Crucifixion as a loose image, see Rudy, Postcards on Parchment (p. 288).

28 Iuramentum fratris. Ego N. promitto fide mea media prestita atque juro ad hec sancta Dei ewangelia manu mea dextera corporaliter tacta quod ab hac hora in antea ero fidelis fraternitati sacerdotum ecclesie sancti servacii trajectensis cartamque statutorum eiusdem fraternitatis necnon statuta omnia ordinata et ordinanda que mutata revocata seu sublata non fuerint inviolabiliter observabo pro posse. Et me in factis seu negocijs dicte fraternitatis contra ipsam fraternitatem partem non faciam et secreta fraternitatis eiusdem non revelabo. Sic me juuet deus et hec sancta dei ewangelia (HKB, Ms. 132 G 35, fol. 3r).

29 I make a similar argument about prayerbooks that contain parts of Gospel texts: these could also be used for oath-swearing. See Kathryn M. Rudy, “Targeted Wear in Manuscript Prayerbooks in the Context of Oath-Swearing,” Models of Change in Medieval Textual Culture, Jonatan Pettersson and Anna Blennow (eds) (forthcoming, 2024).

30 For a lively discussion of manicules, see Erik Kwakkel, “Helping Hands on the Medieval Page,” medievalbooks blog (13 March 2015). https://medievalbooks.nl/tag/manicula/

31 For a description and bibliography, see https://bnm-i.huygens.knaw.nl/tekstdragers/TDRA000000003598

32 I thank Irene van Renswoude for bringing this manuscript to my attention. Old signature: 6 K 16, sometimes written 6.K.16. The nineteenth-century cataloguer refers to the manuscript as Liber iuramentorum ecclesiae S. Johannis. That is a descriptive label not given in the manuscript itself. Images and bibliography can be found here: https://objects.library.uu.nl/reader/index.php?obj=1874-339303&lan=en#page//44/90/50/44905082442839785202757785567081520258.jpg/mode/1up

33 In the fourteenth century, someone added two quires to the end in order to supplement the Gospel readings (fols 101r–109).