Chapter 2: Confraternities of Laypeople

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.02

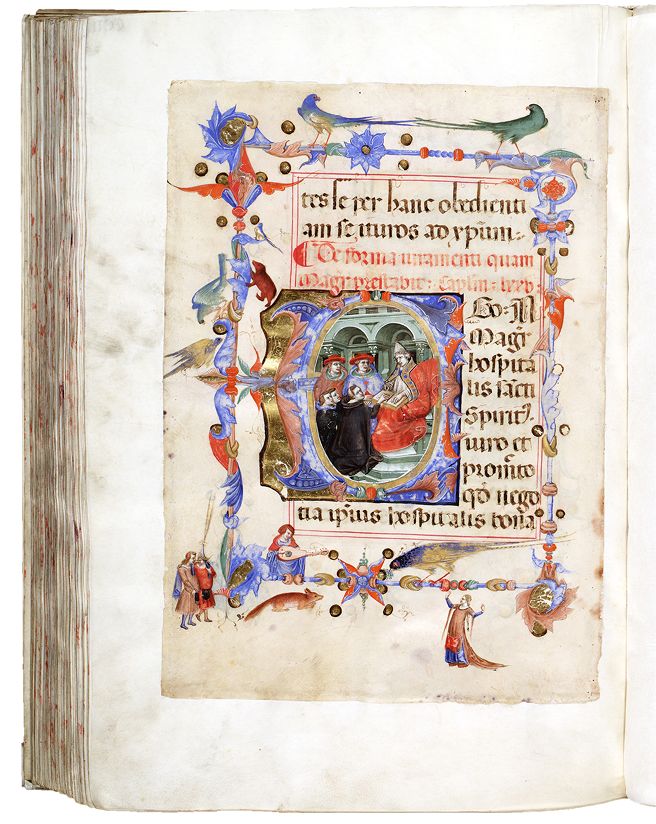

Civic institutions borrowed from the word-gesture-prop formula that operated in ecclesiastical rituals. Manuscripts made for confraternities can disclose aspects of their membership ceremonies, since signs of wear in the relevant books reveal how the ceremonies were locally inflected and adjusted.1 Swearing allegiance to a religious order required making a public statement and placing one’s hand on a document, such as the order’s Rule. The Liber Regulae of the Order of the Holy Spirit, the first non-military hospital order, exists in a highly illuminated copy made in the mid-fourteenth century for the Hospital of Santo Spirito in Sassia, situated in Rome just east of Vatican City (Rome, Fondo dell’Ospedale di Santo Spirito, Ms. 3193, fol. 202v; Fig. 46).2 A historiated initial marks the beginning of chapter LXXV, “De forma iuramenti, quam magister prestabit” (Concerning the form of the oath, which the master will proffer). The image represents a brother professing his obedience to the rule by placing his hand on the open book proffered to him by the pope in the presence of two cardinals. The pope himself places his left hand on the open book, while the brother places his right hand on the facing page, and the two men lock gazes. The book therefore acts as a conduit between papal authority and brotherly submission, and the gesture takes place in front of four witnesses. Both the public nature of the event and the ritual involving authorized words and gestures are required to seal the oath, as Austin’s speech-act theory would have it.3 Several of the manuscripts featured in this study have patterns of wear consistent with the manner of handling shown in this image. With this gesture, instead of placing his hands within those of the overlord, as is pictured in the vassalage ceremony discussed above (see Fig. 6), here the subject places his hands inside a book, as if the enveloping structure of the book, with its symbolism of authority, takes the place of the hands of the overlord.

Fig. 46 Folio in the Liber Regulae of the Order of the Holy Spirit (disbound and mounted in an album), with a historiated initial depicting members of the Brotherhood taking an oath on a book. Rome, Fondo dell’Ospedale di Santo Spirito, Ms 3193, fol. 202v

Knightly orders, such as the Orders of the Golden Fleece, Saint Michael, and the Garter, likewise adopted ceremonies for swearing on manuscripts to assert hierarchical bonds. For example, in 1352 Louis of Taranto, King of Naples, founded the Order of the Holy Spirit with Noble Desire, which was also called the Order of the Knot (L’Ordre du Saint-Esprit au Droit Désir, or the Ordre du Noeud). He commissioned a manuscript, filling nine elaborately-painted folios, that presented the order’s statutes (Paris, BnF, Ms. fr. 4274).4 The statutes detailed the obligations of the members of the order, including the specific garments—robes, mantles, and colored sashes—that they were compelled to wear during ceremonies. Knightly members also had to perform warlike feats to gain the ultimate distinction of wearing the untied knot, which distinguished the bravest knights from their more cowardly comrades, who brandished pretzel-shaped knots. The knights also had to perform charitable acts and to commemorate their dead. A miniature in the manuscript shows a group of knights, each with the insignia of the golden knot on his shoulder, kneeling before the king to swear an oath of loyalty (Fig. 47). The knights place their hands on the open book proffered by the king. Whereas members of the Order of the Holy Spirit (in the previous example) pledged their oaths to the pope, the members of the Order of the Holy Spirit with Noble Desire pledged theirs to King Louis. In these two examples, one can see how what had been an ecclesiastical ritual, set in a church with cardinals and the pope, morphed into a secular one staged around a royal throne. Re-staging the ceremony in this way helped to assert the divine right of the king and to enforce the solemnity of the ritual, which borrowed its prestige from ecclesiastical precedents.

Fig. 47 Folio in the Statuts de l’ordre du Saint-Esprit au droit désir, with an image depicting knights swearing an oath to King Louis of Taranto. Naples, 1352-1353. Paris, BnF, Ms. fr. 4274, fol. 3v, and detail

As urbanization intensified in Europe and England, the culture of oath-taking continued to expand beyond the church and the court into the new civic organizations that people — primarily men — formed to create bonds of trust. In a Europe still deeply steeped in Christian culture, these bonds continued to be endorsed under the auspices of the Word. In the fourteenth century, various trade organizations, or guilds, were founded in cities across Europe. These guilds established rules around labor and product quality, enforced protectionist trade regulations, prayed for the souls of deceased members, and paid for Masses. Although primarily trade organizations, they leveraged Christian values around labor and ethics.

Manuscripts commissioned by the guilds preserving their statutes and their matriculation registers. Guilds in the city of Bologna were particularly active in this area. Surviving manuscripts, largely preserved in the Archivio di Stato of Bologna, include the statutes of the sword makers (1285 and 1378), of the notaries (1336 and 1382), of the blacksmiths (1366), of the silk workers (1372, 1381, 1398, 1410, 1424), of the salt sellers (1376), of the barbers (1376), of the saddlers (1378, 1422), of the drapers (1346), of the carpenters (1377), of the goldsmiths (1383), of the tailors (1379-1466). The rise of these new urban trade organizations coincided with a new government in 1376, free from papal control. Even the new government commissioned a manuscript, the Statutes of the Municipality (1376). Additionally, matriculation registers survive, including the register of the apothecaries’ guild (1318), of the haberdashers’ guild (1328), of the shoemakers’ guild (ca. 1386), and of the creditors of the Monte di Pietà (in five volumes, from the 1390s, discussed below). This partial list shows that illuminated corporate manuscripts were de rigueur for these new guilds and professional societies.5

Since the genre of illuminated secular statutes and registers was new, illuminators experimented with programs of imagery, which largely took the form of elaborate frontispieces. Due to treasure-seekers mutilating many of the volumes in the nineteenth century, many frontispieces now reside in collections across Europe and North America. As Alessandra Gardin points out, the imagery in these manuscripts is largely religious, despite the commercial and secular nature of the manuscripts.6 This is because the texts themselves begin with an invocation to Christ, Mary, and patron saints. Gardin also notes that guild rules required members to observe religious holidays, celebrate the feast of the patron saint, and they penalized members who worked on Sundays and holidays. Members were also required to attend Masses celebrated for the guild or deceased members.

Although the imagery was not standardized, patterns emerge across the group. Some of the statute volumes feature an image of Christ Crucified between Mary and John, as one would expect to find in a missal. According to Patrick de Winter, a cutting depicting Christ Crucified, now in Cleveland, had been thought to come from a Missal belonging to the Duke of Anjou, but in fact, came from the Statutes of the Apothecaries (Fig. 48).7 The leaf bears the signature of Nicolò di Giacomo, also known in the literature as Niccolò da Bologna. As the official illuminator for the city of Bologna at the end of the fourteenth century, he illuminated many books of statutes and guild registers. The mutilator trimmed off most of the coat of arms below the frame, so that it could be interpreted as a prestigious Anjou commission. However, as de Winter points out, there were three shields below the Crucifixion, with one larger shield in the upper field depicting France ancien and a six-pendant label of gules. De Winter clarifies that these heraldic elements correspond to the city of Bologna, not the Anjou family, as previously asserted. The two lateral escutcheons probably represented the Corporation of the Apothecaries, identifiable by the ends of two pestles in gold mortars on a field of azur, the motif on this guild’s shield.8 In other words, Nicolò di Giacomo used Crucifixion imagery in the apothecaries’ manuscript to give their statutes the gravitas of a Missal.

Fig. 48 Nicolò di Giacomo, Crucifixion, ca. 1390, cutting probably from the Statutes of the Apothecaries of Bologna. Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. 24.1013

Nicolò di Giacomo produced a different iconographic program for the five volumes he painted for the creditors of the Monte di Pietà, an innovative public loan fund established in the late 14th century. This system was designed to stabilize the city’s finances by recording loans made by citizens to the city, which promised repayment with interest. The frontispiece from one of the volumes is now in the Morgan Library (Ms. M.1056).9 The recto shows two rows of standing saints, identified at their feet as St Petronius, St Paul, St Ambrose, St Dominic, St Francis, and St Florian (Fig. 49). The presence of these saints, who oversaw the loans, helped instill confidence in the lending process, as long as both parties believed that saints could wield power.

Fig. 49 Nicolò di Giacomo, Six Standing Saints, 1394-95, frontispiece cut from a volume of the register of the creditors of the Monte di Pietà of Bologna. New York, Morgan Library and Museum, Ms M.1056r

The verso of MS M.1056 has a bipartite miniature (Fig. 50). The left side depicts St Peter, the patron saint of the district of Porta San Pietro in Bologna. The volume from which this image was cut may have come from that district. He holds his attribute, the key, and an open book, as if he were overseeing this very register. When Bologna established its new government in 1376, the city began minting its own coinage, the gold bolognino d’oro, which had the same imagery — St Peter with a key and book — stamped onto its obverse. Thus, St Peter was closely associated with the new coins, which also appear on the right half of the image, where a goldbeater is at work, surrounded by sacks and piles of coins.

Fig. 50 Nicolò di Giacomo, St Peter and man beating gold, 1394-95, headpiece cut from a volume of the register of the creditors of the Monte di Pietà of Bologna. New York, Morgan Library and Museum, Ms M.1056v

Two details, which appear outside the frame and have often been trimmed off when this image has been reproduced, provide some clues about how this folio might have been handled. Although the rest of the leaf is in excellent condition, the historiated initial A shows Christ raising his hand in benediction. This initiates the invocation to Christ, Mary, and the saints on the recto. Although the other figures on the leaf are undamaged, the Christ initial has been deliberately touched, to the point where much of the paint on the figure’s torso is missing, and the gold leaf has flaked off, revealing the pink ground. The beginning of the invocation is also damaged, as if those uttering the invocation purposely touched Christ when doing so. Two other areas of the leaf are also damaged: at least one person who touched the pile of coins then wiped his finger into the nearest margin. Although this touching of the coins might be written off as a stray accident, the fact that the pile of coins depicted in another volume of the Monte di Pietà registers has also been touched in a similar way raises the possibility that the gesture belonged to a ritual designed to secure the fiduciary arrangement.10

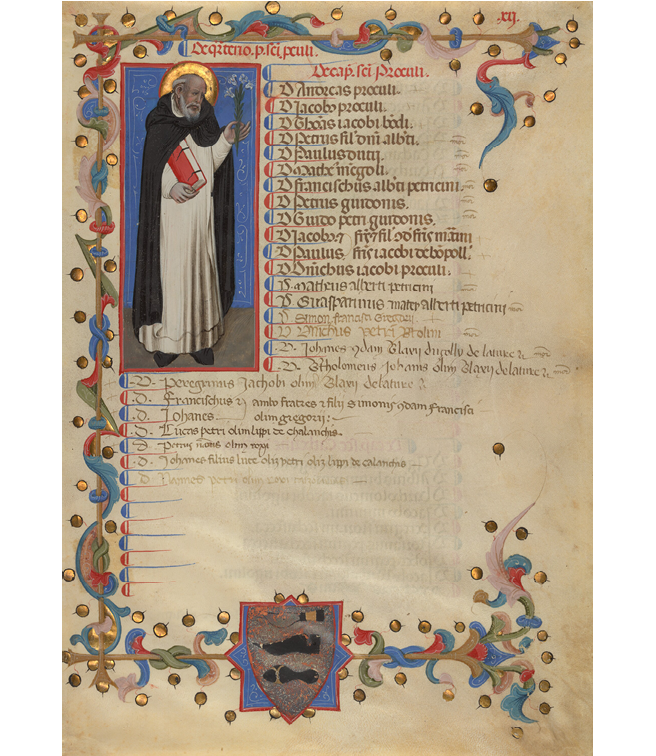

It is the nature of registers that their content changes with use, since text is continually added to them, similar to necrologies, another book genre from which the scribes and illuminators borrowed design ideas. (This theme will be taken up again in Chapter 5, below.) In particular, registers were designed to contain blank parchment that will eventually be filled in with members’ names. For example, a folio from the register of the Bologna shoemakers’ guild, made around 1386, is now a cutting in the Getty Museum (Fig. 51).11 Nicolò di Giacomo illuminated the leaf with an imposing image of St Dominic, whose church was in the shoemakers’ quarter. The leaf lists the names of the members of the shoemakers’ guild, inscribed over time by a series of hands. A simple cross or the designation “mor” (mortem) is written next to the names of deceased members. Living members were obliged to pray for them. Just as the shield for the apothecaries’ guild featured a mortar and pestle, the shield for the shoemakers’ guild features a knife, shoe, and sandal. Indeed, throughout this body of manuscripts, the shields are the main secular imagery, as they stand for the goods or services provided by the guild members. In the shoemakers’ guild register, it appears that the shield of shoes has been touched, and the paint is smeared and chipped. In other manuscripts from the group, the shields have similarly been touched, revealing that a shield-touching gesture may have also formed part of the book-centered rituals among the guilds.

Fig. 51 Nicolò di Giacomo, folio from the register of the Bologna shoemakers’ guild, ca. 1386. Los Angeles, Getty Museum, Ms. 82 (2003.113)

Guilds in other cities, too, commissioned manuscripts to formalize social networks among professionals and to maintain standards of quality. For example, the Oxford company of tailors had an oath book, which was begun in the fifteenth century but was used by masters of the company until the eighteenth century.12 Such manuscripts helped to form strong bonds among cohorts of simultaneous members as well as cohorts over time. Gospel pericopes were copied near the beginning of the manuscript so that when members swore their oaths, they were doing so in the presence of the Gospels. The hand of God thereby exerted control over civic and professional groups.

The manuscripts discussed above have distinctive patterns of wear indicating that their respective ceremonies differed. Horizontally organized groups—such as those with non-hereditary members who were equals—fell into several institutional contexts. In satisfying the demand for the human need to feel a sense of belonging, various kinds of confraternities formed in the late Middle Ages that gave members opportunities for horizontal connections both on earth, and—equally importantly—in the afterlife.13

Members of ecclesiastical chapters swore oaths to attain their offices, and to join brotherhoods, as the previous section showed. When laypeople likewise formed groups, often under the aegis of a religious establishment, the entrance procedures resembled those of their religious counterparts. They used books as props and uttered ceremonial words. Swearing into a confraternity also resembled vassalage ceremonies. Initiates adapted gestures to express their loyalty to certain saints, especially those associated with the military class who dressed as soldiers (including Sts Sebastian, Adrian, and George). Just as overlords promised protection to vassals in exchange for fealty, money, and service, so could military saints step into the role of overlord and thereby extract devotion, service, and money from believers. For the remainder of the chapter, I analyze manuscripts made for three confraternities, two of them dedicated to St Sebastian. The cult of this military saint played a role in reforming the behavior of crusading knights: Alan de Lille, in the late twelfth century, urged soldiers to behave less brutally by following the Christian example set by St Sebastian.14 In the period after the Black Death, the saint was strongly associated with bodily protection, since the arrow wounds he incurred during his execution resembled the buboes of plague victims. For the brotherhood who gathered under his name, he was venerated as a knight, as a prophylactic against disease, and as a patron of shooting.

The evolution of confraternities reflects the shifting patterns of religious practices and affiliations. Confraternities of prayer had begun in a Benedictine monastic environment, with the purpose of maintaining memoria of members and donors. Membership in these early monastic confraternities was usually open to laymen who made a substantial one-time donation. After ca. 1200, such confraternities moved away from monastic administration, and toward a system of annual membership fees, and they welcomed both male and female members. Although confraternities first formed in the early twelfth century in France, the number of such organizations multiplied after the Black Plague when desperate Christians turned to collective prayer to protect themselves from disease. Unlike Psalters or missals, manuscripts for brotherhoods had no fixed form, and it is therefore difficult to make generalizations about them, other than this: signs of wear in their pages often reveal aspects of membership rituals and of collective prayer for their deceased members.

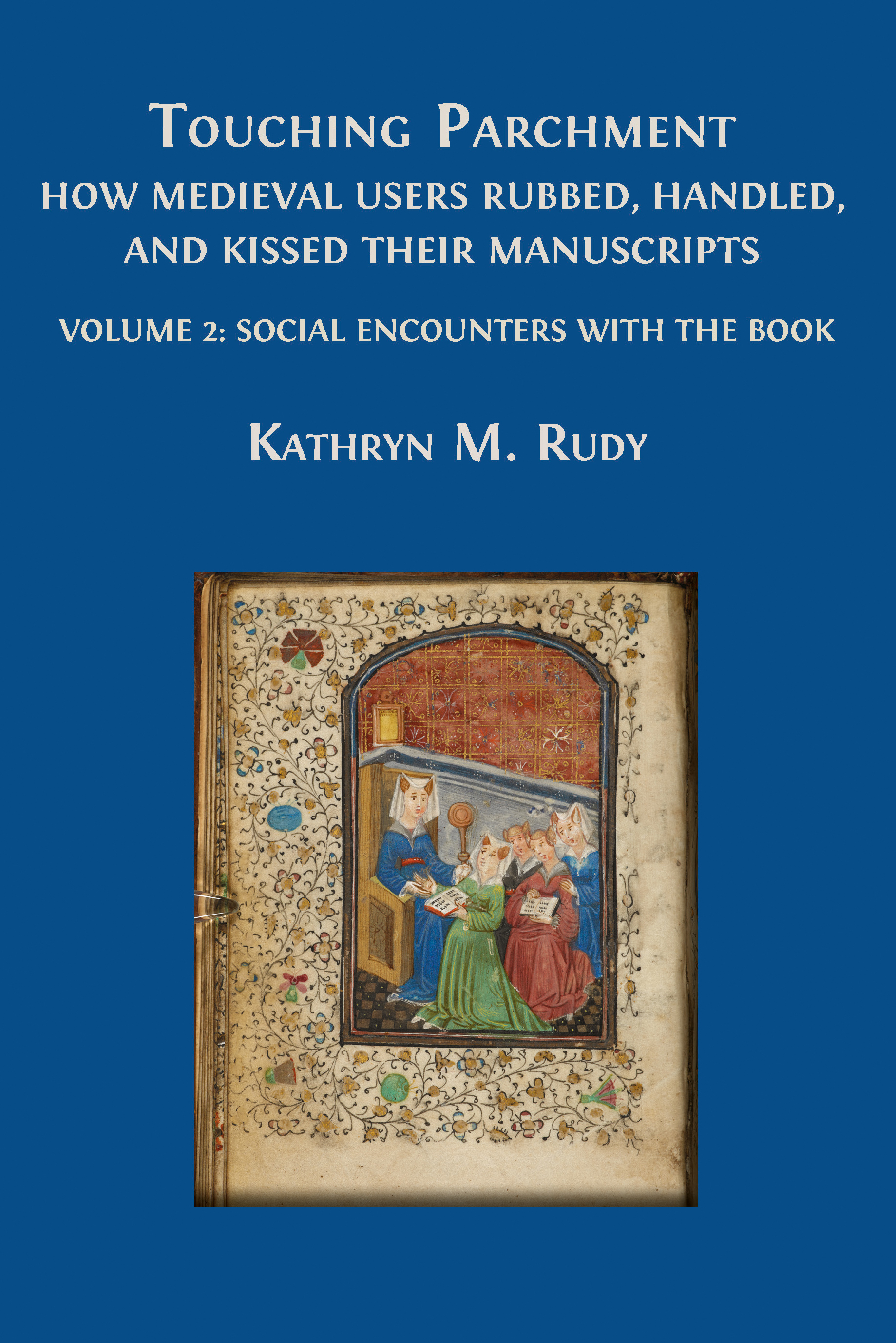

I. The colorful confraternity of St Nicholas

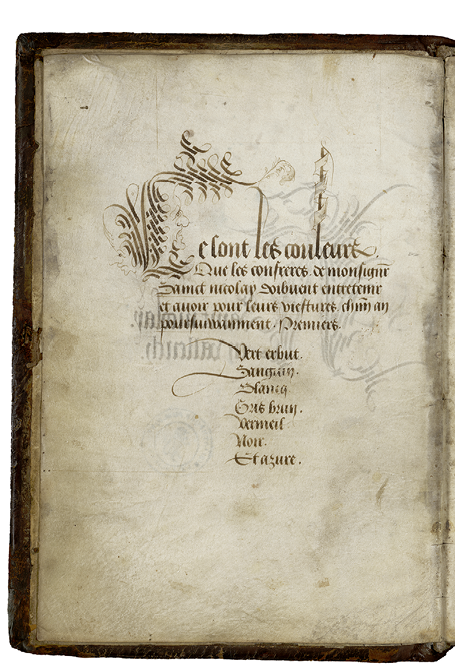

In 1423 in the town of Valenciennes, a group of men formed a confraternity to honor the relics of St Nicholas, to pray for each other upon death, and most importantly, to form a robust all-male social club. This confraternity mandated such activities as dressing smartly, feasting, drinking, and processing with a reliquary holding the bones of its patron saint. While the original statutes from 1423 do not survive, a copy from the end of the fifteenth century does.15 The manuscript (now Valenciennes, BM, Ms 536) was undoubtedly made for the confraternity, possibly to replace the 60-year-old exemplar in tatters. The scribe produced the confraternity manuscript in a legible bâtarde script, the norm for vernacular administrative documents of the fifteenth century.16 (A transcription and a translation of the entire manuscript appear in Appendix 3.) This copy exhibits many signs of use, with marks from both inadvertent and targeted wear. The textual contents, numerous images, and evident wear in the Valenciennes manuscript provide a sense of what the confraternity meant to its members.

It is clear that their participation in the confraternity was thoroughly embodied. Membership was highly selective and limited to 50, chosen among current and former clergy. (This confraternity therefore bridges ecclesiastical confraternities, discussed in the previous chapter, and emphatically lay ones.) Being elected to this body was no mere sinecure or civic prize. Confrères committed to taking care of the reliquary of St Nicholas, which they regularly processed through the streets of Valenciennes. They are depicted doing so in several of the miniatures. Furthermore, the brothers convened to sing and pray, and also to ante up their dues. Finally, members had to attend Masses, including requiem Masses for the deceased brothers. They marked their election to the brotherhood by taking a solemn oath, signifying their commitment to these activities. The brotherhood demanded members’ full participation, once they were initiated with an oath and ceremony. Those who failed to participate in the frequent specified activities were penalized with fines: fines for missing the annual dinner; fines for failing to carry the reliquary correctly; fines for paying the annual dues late; fines for talking during the procession. Most of these would be paid in cash to the confraternity’s coffers or to the fund for the building maintenance, but some of the fines were to be paid to the reliquary itself, in the currency of wax. The wax would be turned into candles to illuminate and honor the object of their attentions. Maintaining, handling, carrying, processing, and guarding the reliquary were central to confrères’ activities.

Within the brief written space of 28 folios, the book’s 11 images depict the journey of a member from his initiation to his demise. The imagery, however, only shows the brothers as members of the group, never as individuals. The manuscript begins by specifying the seven colors of clothing that the brothers may wear, and in fact, must wear (Fig. 52). So important is this information that it is given an entire folio, decorated with elaborate pen flourishes. To ensure that the brothers have uniform-colored garments, each is given a fabric swatch to hand to his respective tailor. A section of the manuscript is dedicated to the construction of these coats, in all their intricacies, including their embroidery (fols 19r–20r, transcribed in Appendix 3). In this respect, the manuscript, with its textual and visual attention to ceremonial garments, can be compared with the Statutes of the Order of the Holy Spirit with Noble Desire, discussed earlier. Members demonstrated their group cohesion through distinctive dress.

Fig. 52 Folio in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, outlining the colors that confrères must wear. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 1v

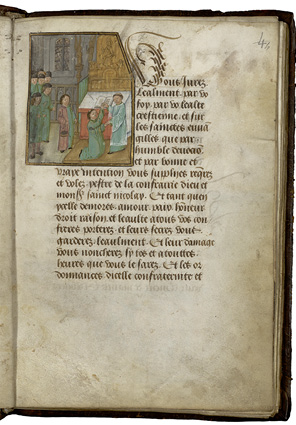

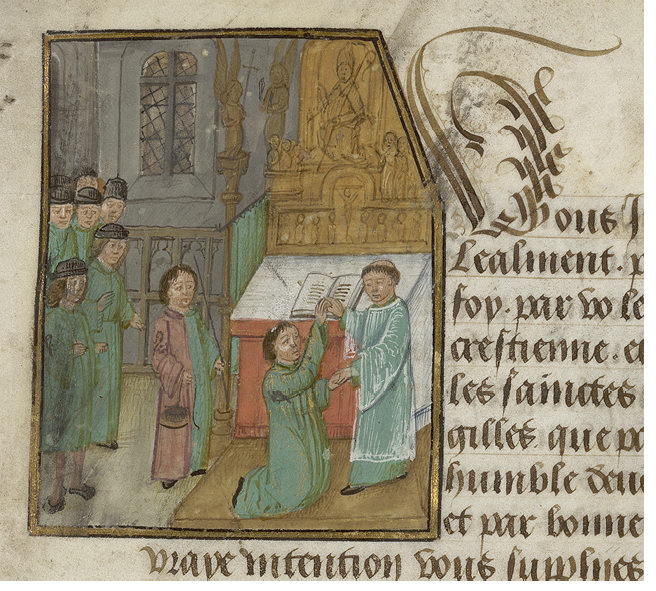

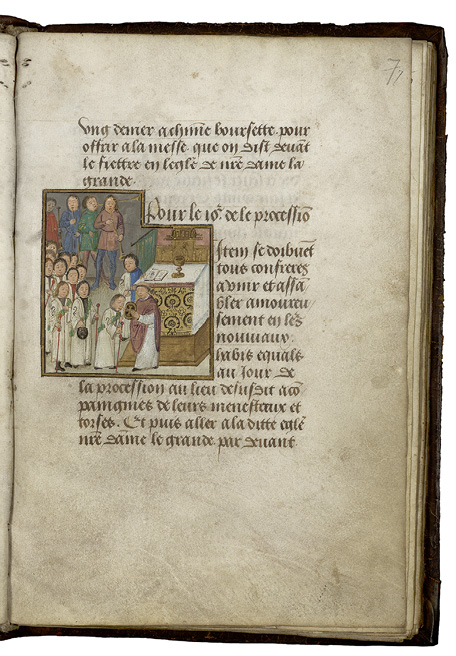

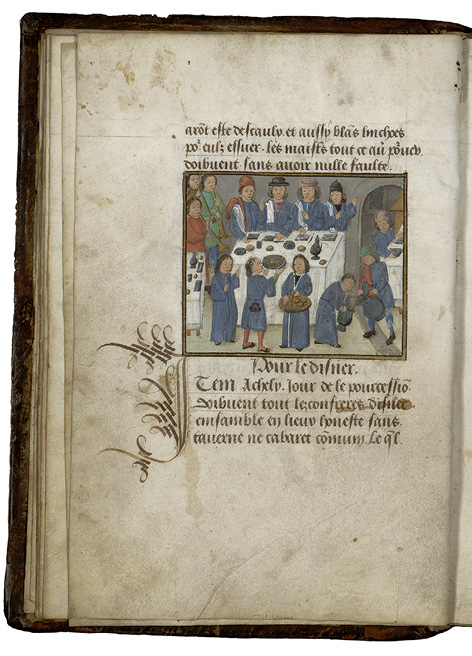

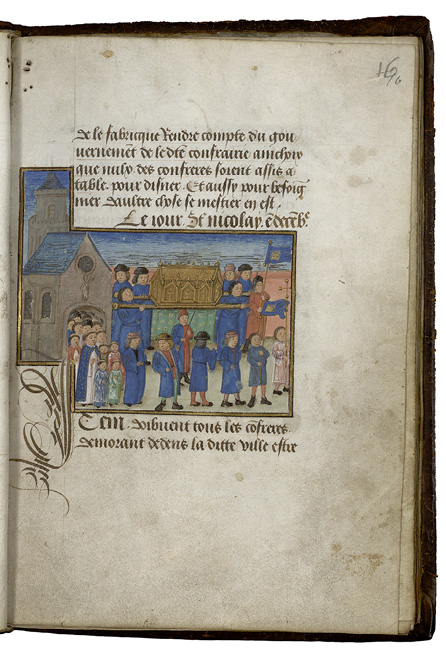

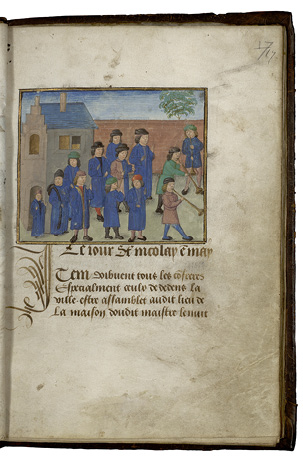

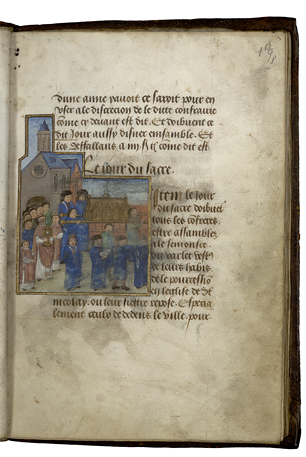

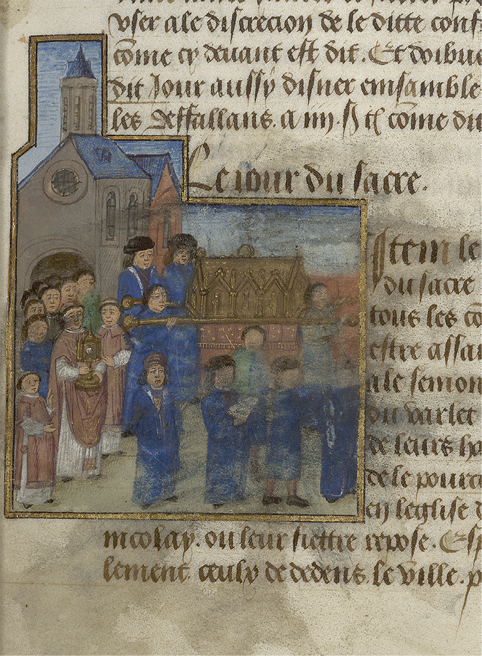

Across the Valenciennes manuscript, the illuminator depicts confrères wearing the full spectrum of outfits. For the oath of a new brother, the brothers wear green (fol. 4r; Fig. 53). At the procession for the feast of the Birth of Mary on 8 September, they wear their blood-red coats (fol. 5r). For the Mass of the brotherhood on the day of the procession, they wear white floor-length robes (fol. 7r; Fig. 54). They are coordinated in grey at their annual banquet (fol. 9v; Fig. 55), wear vermillion when they elect new masters (fol. 12r), and appear in their black gowns the day they pay their annual dues (fol. 14v). They wear blue when they process the relics of St Nicholas on his feast day in December (fol. 16r; Fig. 56), and keep the same blue attire when they gather for the translation of St Nicholas in May (fol. 17r; Fig. 57). They wear blue again for the procession of the relics of St Nicholas on consecration day (fol. 18r; Fig. 58). They wear blood-red to bury a brother (fol. 21v) and also to attend vespers and requiem Masses (fol. 23r). From these activities, we can perceive what the brothers valued about the group: it provided a regulated social environment, meals and sociability, a visible monument paid for collectively. It organized pious activity, and it ensured that surviving members would pray for deceased ones, giving them a sense of color-coordinated belonging.

Fig. 53 Folio in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, with an image depicting the oath of a new brother. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 4r, and detail

Fig. 54 Folio in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, with an image depicting the Mass of the brotherhood. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 7r

Fig. 55 Folio in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, with an image depicting the brothers at their annual banquet. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 9v

Fig. 56 Folio in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, with an image depicting the procession of the relics of Saint Nicholas on his feast day in December. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 16r

Fig. 57 Opening in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, with an image depicting the gathering of the brotherhood on the feast of St Nicholas in May. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 16v–17r

Fig. 58 Opening in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes, with an image depicting the procession of the relics of Saint Nicholas. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fols 17v–18r

Both the text and images in Valenciennes 536 show that several of the rituals involved codified words and gestures. At the Mass celebration on the day of the procession (fol. 7r), they walk with staffs, wear sashes, and kiss an enormous pax proffered by the priest near the altar. When the new recruit takes his oath (fol. 4r), he and the tonsured priest clasp left hands while they both place their right hands on a book. While it is clear from the description of the oath-taking that the ceremonial book used at the altar (pictured on fol. 4r) was a Gospel manuscript, not the brotherhood’s statutes, the brothers also interacted with Valenciennes 536 in ritualized ways.

The large amount of grime on the opening folios of the manuscript, especially on the opening at the front of the book, means that the possibility of the brothers touching this book ceremonially during their oath-taking ceremonies cannot be ruled out. The opening describing the ceremony of oath-taking (fols 3v–4r) has handprints all around the margin, including the upper margin, which one does not usually touch in order to turn the leaf. This dirt may indicate that the manuscript was used for touching, just as the book in the illumination (fol. 4r) is depicted being touched.

Other marks of wear indicate that confraternity members interacted with images of themselves socializing, perhaps re-living intense experiences in January through May when the confraternity’s physical activities were in a lull. At the banquet scene (fol. 9v), someone has touched the face of the brother who is receiving wine in his ewer. Was he recalling drinking at the meal? In the first procession image, someone seems to have wet-touched the blue hem of one of the brothers (fol. 16r). In isolation, that could be written off as a stray touch, but similar abrasion appears on the figures in the May festival. The damage is extreme in the second procession image (fol. 18r; Fig. 59), where the hems and faces of several members have been thoroughly abraded. The image may have been splashed with drink at one of the annual dinners; if so, that indicates that the manuscript was present at the gala feast. Furthermore, at the folio where the brothers are shown participating in a requiem Mass (fol. 22r), a user has wet-touched the top of the image and the headline. Whether this manuscript was used in actual ceremonies or formed a keepsake for one of the enthusiastic members, it prescribed various bodily rituals and also preserved their rehearsal. That several of the images within the manuscript have been deliberately touched suggests that this manuscript had active utility.

Fig. 59 Miniature in the Confraternity Book of St Nicholas of Valenciennes depicting the procession of the relics of St Nicholas. Northern France (Valenciennes?), ca. 1490. Valenciennes, BM, Ms. 536, fol. 18r (detail)

Since the interactions take place according to highly structured and codified rules, it makes sense that the brothers would have referred to the manuscript frequently for instruction. The text even specifies the food to be served during their feasts, down to the types of roast, the accompanying sauces, and the kinds of suitable restaurants where the feasts can take place (not in a cabaret!). These feasts had strict gender rules, with the text explicitly stipulating that no women should serve at these events.

Besides dinners, many of the other structured events took place around the reliquary, which was retrieved from the Church of Our Lady, processed, and returned to the chapel dedicated to St Nicholas within the Marian church. The group was more dedicated to the reliquary than to St Nicholas himself, whose vita is never mentioned in the manuscript. Nor were the confrères interested in patterning themselves after the charity for which their patron saint was famed. Instead of supporting orphans or providing dowries for destitute girls, they spent their disposable income on lavish, brightly colored clothing for themselves in which they made frequent, loud, public appearances. The sounds of their gatherings can be inferred from the minstrels and trumpeters specifically mentioned in the text. These hired extras would have heralded the colorful brotherhood, making their public appearances even more performative and noisy. Group members were on display, engaged, and highly visible. Even if their confraternity had only been founded in 1423, the text- and image-based, rule-bound interactions would have projected a sense of tradition. However, theirs was an invented tradition.

The confraternity of St Nicholas testifies to medieval communal practices, and the survival of its book of statutes offers a rare and vivid insight into the values and ceremonial intricacies of such groups. Bearing signs of wear and deliberate touch, the manuscript serves as an artifact of lived experiences. Its folios bear witness to the importance of shared rituals, to the ways in which these medieval men related to their world and each other. The intertwining of the tangible (the manuscript) and the intangible (the deep human connectivity) corroborates the layering of ritual with emotion. It contrasts sharply with a confraternity manuscript made slightly earlier just outside Brussels, the subject of the next section.

II. Ducal patronage at Linkebeek

In 1110 Godfrey the Bearded, Count of Louvain (ca. 1074–1139), founded an oratory dedicated to St Sebastian in the town of Linkebeek, a village west of Brussels, setting into motion a series of events that would generate a pilgrimage church, a confraternity, and an ornate and intensely used manuscript.17 Godfrey likely selected St Sebastian, the protector of archers, due to his own knighthood. Sebastian, once a Roman soldier who survived a barrage of arrows, earned the reputation of answering the calls of soldiers, military campaigners, plague victims, and those dreading the plague. After the Black Death, Linkebeek welcomed an influx of pilgrims who sought cures for mortal diseases and who wanted to shield themselves from the bubonic plague, which had swept through Europe first in 1347–1349, and then revisited towns in subsequent decades.18 Arrows connoted the plague sent by an angry God, because arrow wounds, such as those incurred by St Sebastian, resembled the buboes caused by the disease. Linkebeek and St Sebastian thereby became closely intertwined, with the saint’s veneration playing a pivotal role in the village’s development.

The legend

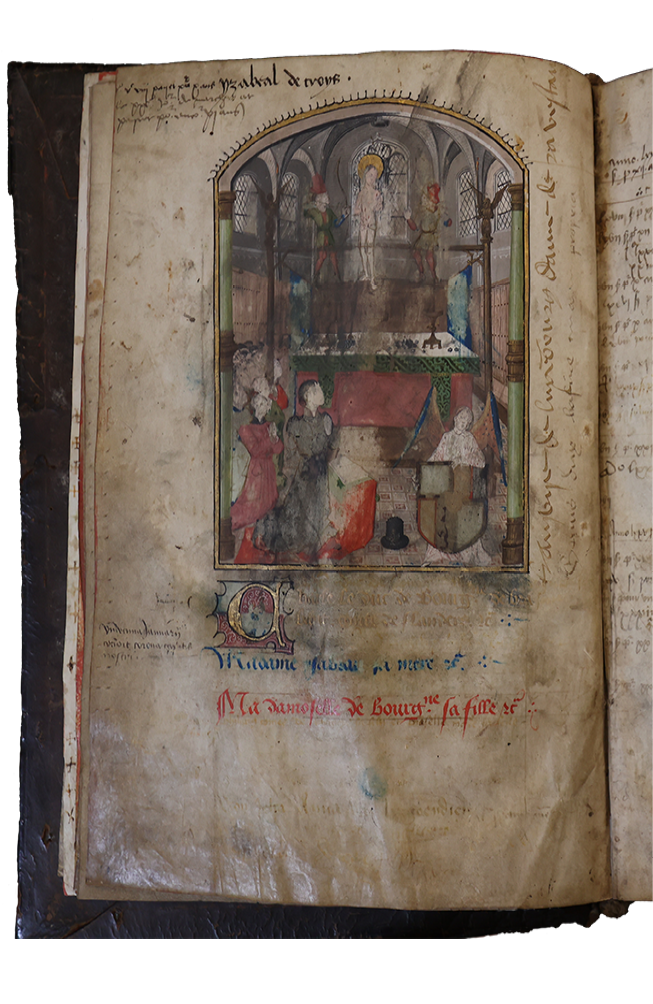

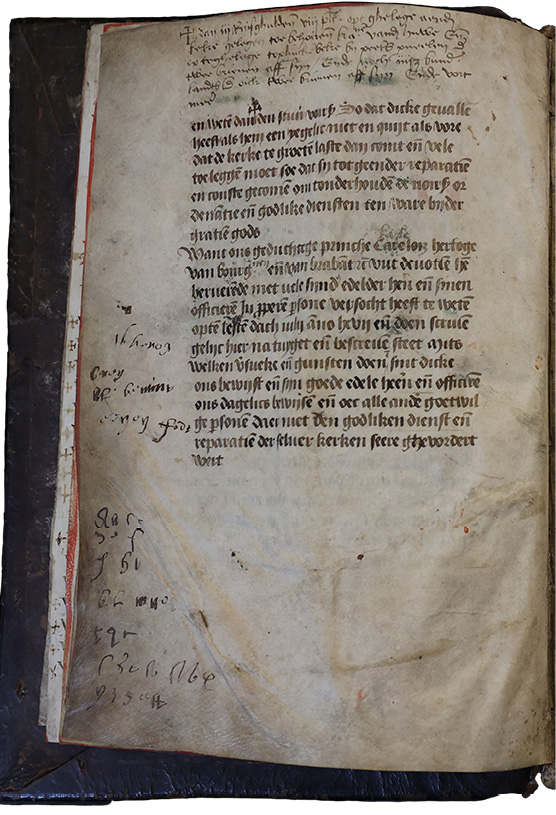

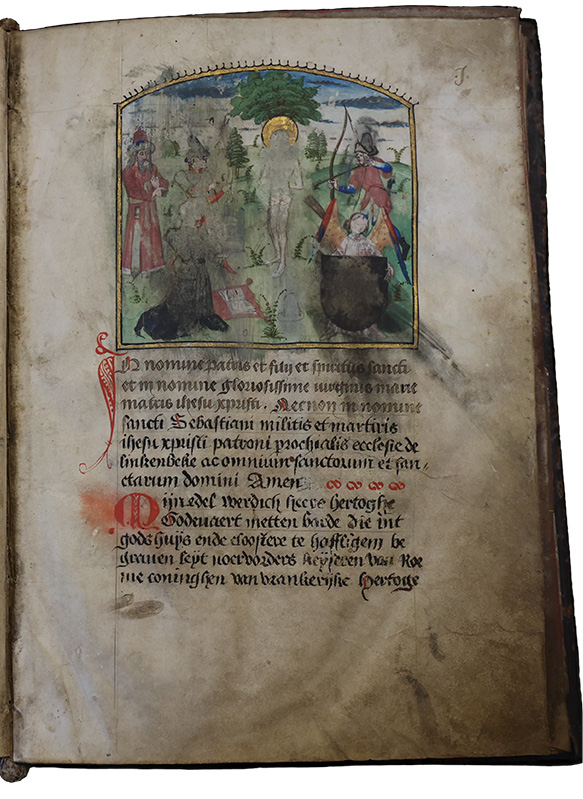

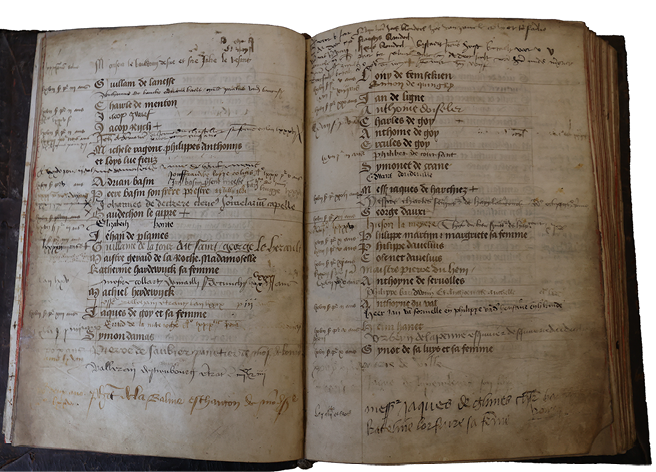

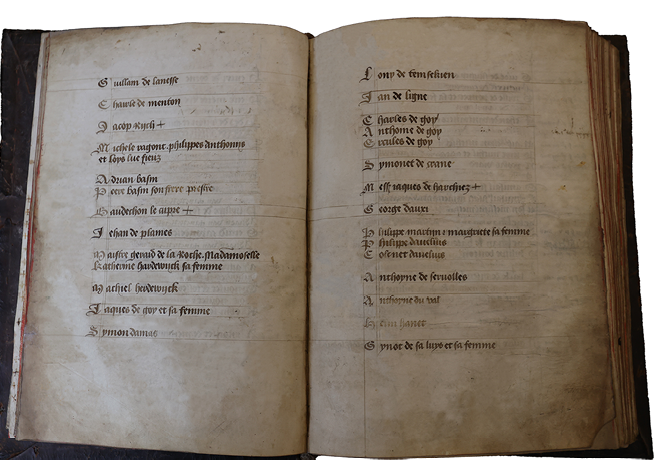

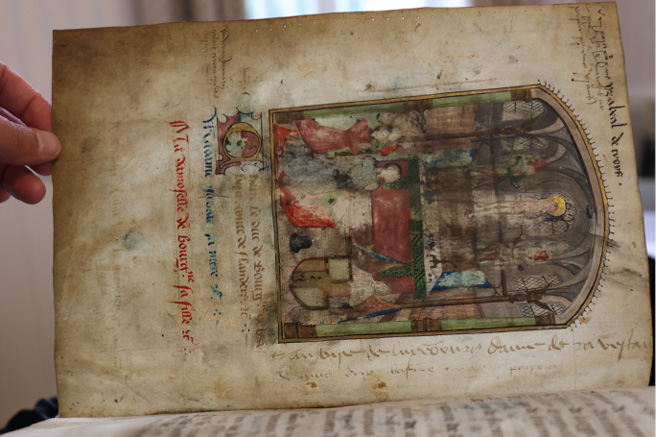

After Charles the Bold (1433–1477, Duke of Burgundy 1467–1477) attributed a miraculous cure he experienced to the workings of St Sebastian, he made multiple gestures of gratitude. He took a pilgrimage to St Sebastian’s shrine in Linkebeek. He also founded a confraternity dedicated to St Sebastian, to be based in Linkebeek. As an accoutrement of the confraternity, he commissioned a manuscript, which calls itself the Guldenboek (or “Golden book;” Fig. 60).19 Made beginning in 1467, the manuscript, which is still in Linkebeek, is very brief and contains only two short texts and two miniatures (fols 1r and 2v) in a single quire: a legendary story about Charles the Bold’s miraculous healing at the hands of St Sebastian (fol. A verso), and a descriptive foundational text (fol. B recto-verso). After the two texts, which I will discuss shortly, the majority of the quires consisted of blank, ruled parchment, now populated with hundreds of confraternity members’ names, in nearly as many hands.20 Charles had, in effect, given the people of Linkebeek a visitors’ book. By the evidence of the number of names inscribed in the decades before 1500, the confraternity was exceedingly popular throughout the duke’s lifetime and within his living memory.

Fig. 60 Folio in the Linkebeek Guldenboek with an image depicting Charles the Bold before an altar dedicated to St Sebastian, Brussels, 1467. Linkebeek, Parish Church, unnumbered manuscript, fols 2v

In 1477, a text was added to the Guldenboek (fol. A verso) that recounts an event from ten years earlier and elucidates the reasons for the confraternity’s establishment (Fig. 61; for a transcription and translation, see Appendix 4A). As is clear from the red smear at the top of the folio—an offset from the rubric on the facing page that the scribe has avoided—this text was inscribed later, on what had been a blank sheet. It narrates an episode that allegedly took place in July 1467: during his stay at the palace of Louis of Bourbon in Liège, Charles the Bold fell ill at the dinner table, suffering from a “pestilence in his armpits.” (Swollen glands at the groin and armpit symptomized the bubonic plague and usually spelled death.) The duke excused himself to the oratory to pray to Jesus, Mary, and St Sebastian, “our patron saint at Linkebeek,” for a cure. His prayers were answered, and he lived another ten years. Later he visited Linkebeek with his entourage. Although these dates cannot be accurate (Charles’s itinerary does not place him in Liège in July 1467, and he actually visited Linkebeek in November 1468 after his conquest of Liège on his way back to Brussels), this is how the miraculous cure is remembered. The purpose of the text added in 1477 was to recount the miracle and thereby demonstrate the efficacy of the shrine, and to explain Charles’s reason for founding the confraternity.21

Fig. 61 Opening of the Linkebeek Guldenboek. Linkebeek, written in 1477 and 1467. Linkebeek, Parish Church, unnumbered manuscript, fols Av–Br.

Furthermore, the text added in 1477 provides some additional information about the ducal patronage of the shrine. First, the added text mentions a magnificent object in the church in Linkebeek: a golden statuette.22 According to the text, Charles gave the shrine a “guldene man” and a “man van waesse”: that is, a figure made of gold and a figure made of wax. These votive figures, given as thanks for his miraculous cure, do not survive, although accounts of their purchase do. Gérard Loyet, goldsmith at the court of Charles the Bold, made a stock of images depicting the duke’s likeness, which the duke then distributed to shrines around the territory he commanded (Fig. 62). Such spectacular and lavish gifts created a permanent presence for the itinerant duke. Loyet produced silver busts of Charles in a kneeling position for the shrines at Our Lady of Scheut near Brussels and Our Lady of Aardenburg, and he made busts representing the duke for the Church of St Sebastian in Linkebeek and for the Church of St Adrian in Geraardsbergen. To accompany these gifts, according to a payment record of 1470, Charles paid for Masses to be said at De Lier on Thursdays, at Geraardsbergen on Fridays, at Our Lady of Scheut on Saturdays, and at Linkebeek on Tuesdays.23 For these four images, Loyet received payment in 1477, the same year that the text mentioning the golden gift was added to the Linkebeek manuscript. This image was delivered only after the duke had died in the Battle of Nancy on 5 January 1477. The text added in 1477 also mentions that the duke’s daughter Mary of Burgundy commissioned daily Masses for her father’s soul. These Masses were “performed by the bishop of Cambrai in the Church of Saint Sebastian at Linkebeek,” according to the added text.

Fig. 62 Gerard Loyet, Reliquary of Charles the Bold, 1467-1471. Liège, Cathedral of St Paul

Gerard Loyet, who helped to create the duke’s public image and reputation, was in fact one of the many confraternity members listed in the Guldenboek, indicating that he was a member of the court in addition to serving as the duke’s goldsmith. Charles did live to see the delivery of one of Loyet’s other creations: a kneeling image of the duke for the Cathedral of Our Lady and of St Lambert in Liège, which is the only one that survives.24 In his exquisite sculpture made in 1467, the duke appears with St George, another military saint. Containing about 500 grams of gold, the Liège votive provides a sense of the scale and level of craftsmanship of this group of exquisite sculptures, which also functioned as votives. The text in the Linkebeek manuscript serves as a testament to the miraculous impact of the shrine and Charles’s subsequent gratitude.

Charles also commissioned numerous images of himself in wax, with Linkebeek numbering among those who received one. These figures would have been turned into candles so that the burning figure could illuminate the altar. (Recall the economy of wax that also operated within the Confraternity of St Nicholas in Valenciennes.) We can imagine the altar in the Church of St Sebastian as one populated by nobles and well-stocked with candles.

Directly facing the text describing Charles’s miracle, a text from the original campaign of work—from 1467—proclaims in vibrant red letters: “This is the Guldenboek of the confraternity of my lord St Sebastian, patron of the parish church in Linkebeek, protector from sudden pestilence and from unforeseen death” (Fol. Br; for a transcription and translation, see Appendix 4B). The text enumerates membership regulations. Contrasting with the confraternity of St Nicholas (discussed in the preceding section), the confraternity of St Sebastian welcomed members of any religious background (lay or clerical), marital status, or sex: anyone could pay, join, and invoke the saint’s protection. Like the Valenciennes confraternity, members paid a fee upon entrance (in this case, one stuiver), and then paid annually, in the form of dues.25 These funds were allocated for building maintenance and to pay for three sung Masses per week: one to honor the Virgin Mary on Saturdays, one for St Sebastian on Thursdays, and on Mondays a requiem Mass for all souls, especially those of members of the confraternity who had died. Failing to pay the dues would jeopardize the sung Masses and threaten the very fabric of the building, which required regular maintenance. While the confraternity guaranteed spiritual safeguarding, it also demanded collective accountability.

Ducal legitimacy

The second text in the Guldenboek states that Godfrey the Bearded founded the oratory at Linkebeek and ensured its financial viability by bestowing upon it “houses, farms and fields, forests, land, duties and rents,” so that the churchwardens could use the income generated from these properties to maintain the oratory (Guldenboek, fols 1r–2v; for a transcription and translation, see Appendix 4C). Additionally, he gave the oratory a relic, namely a piece of the True Cross, which would have assured the supernatural efficacy of the shrine.

These texts also show that Linkebeek played a role in a network of institutions in the neighborhood west of Brussels, some of which also received ducal patronage. For example, Godfrey found his final resting place at Affligem Abbey, a Benedictine monastery not far from Linkebeek. While he did not establish the abbey, he was one of its early protectors. When Charles the Bold established the confraternity of St Sebastian in Linkebeek in 1467, he placed it under the administration of the abbey at Forest (Forêt, Vorst), a Benedictine priory for women, which had been established in 1239. This abbey had considerable power, reputation, and reach.

The text confirms the legitimacy of the current duke, tracing his lineage back to Godfrey the Bearded, and reminds readers (or listeners, if this text was read aloud) how instrumental the ruling lineage had been in constructing and maintaining the shrine. By emphasizing the lineage and contributions of the dukes, the text in the Linkebeek manuscript stresses the noble foundation and the importance of preserving the shrine’s legacy. Finally, the text specifies that new members’ full names (family name and forename) must be inscribed in the book, and in fact the rest of the manuscript contains just that: hundreds of names of members. When they were inscribed into the register, as per the instructions, they would have seen the two bold images at the beginning of the manuscript: the one depicting Godfrey, and one depicting Charles the Bold before the altar at Linkebeek. The Master of Johannes Gielemans, who was active in Brussels in the 1450s and 1460s, executed the two miniatures.26

A large image depicting the martyrdom of St Sebastian in a landscape prefaces the text about Godfrey (Fig. 63). Although severely rubbed and therefore difficult to make out, the image seems to refer to the text it prefaces. The figure on the left, kneeling and with his prayerbook on a pillow in front of him, is probably meant to represent Godfrey the Bearded. His face is so abraded that it is impossible to determine whether he in fact has a beard. (Perhaps users adamantly touched his face as if stroking his eponymous facial hair.) An angel holds up a shield, which may have displayed Godfrey’s coat of arms but is now rubbed beyond recognition. (Although the crest is not identifiable, it is clearly not quartered and therefore cannot be the same crest as the one depicted on the next folio, to be discussed shortly.) The painter has given the figure black attire, which was the color reserved for the Burgundian dukes, as if indicating that the kneeling man belonged to that lineage. If the figure does in fact represent Godfrey, then the landscape may not only serve as a setting for Sebastian’s shooting, but it may also represent the lands whose rents and benefits were granted to the parish church.27

Fig. 63 Opening of the Linkebeek Guldenboek with an image depicting Godfrey the Bearded witnessing the Martyrdom of St Sebastian. Linkebeek, Parish Church, unnumbered manuscript, fols Bv (above) - 1r (opposite)

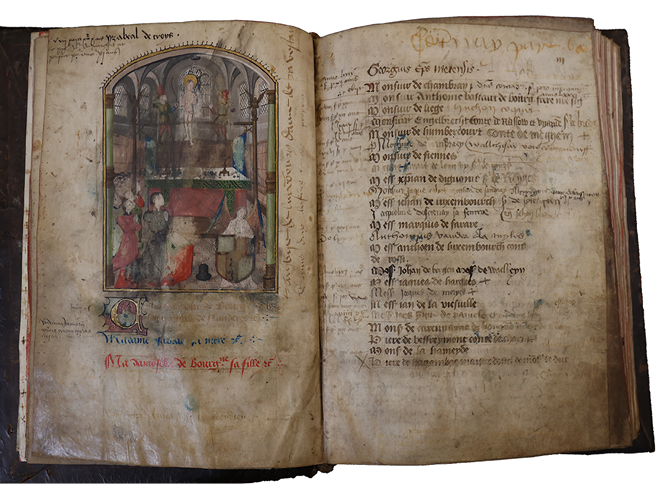

This second image again depicts St Sebastian being shot, but this time in a different setting. Here he appears above an altar in a church (fol. 2v, Fig. 60 as above). At the foot of the altar is a man wearing black, kneeling at a prie-dieu, with many men kneeling behind him, imitating his pose but smaller in size. On the altar are two tapers in elaborate holders, and a pile of silver coins, which may refer to members’ entrance fees. Although here, too, sections of the image are so abraded that the faces and details are indistinct, one can see that the coat of arms is quartered, and its overall layout is consistent with that of Charles the Bold, which has blue fields in one and four and vertical subdivisions in two and three.28 The arms, together with the contextual clues in the text, and the fact that the figure is wearing black, balance the evidence in favor of his identity as Charles the Bold. Given the context, the image shows Charles the Bold visiting the chapel in Linkebeek with his entourage, apparently to convene the confraternity’s inaugural assembly.

Members’ names

Charles the Bold must have radiated charisma, because members of his court rushed to join the confraternity when he founded it in 1467. By appealing to St Sebastian, members tapped into both the saint’s military and medicinal roles, and also paid homage to its ducal founder. St Sebastian promised protection for all the people under his jurisdiction from the most likely sources of death—war and disease. The manuscript lists the names of the hundreds of men and women who joined the confraternity upon its foundation and in the following decades and centuries.

The very first names (on fol. 2v) are those of the duke and his immediate family:

Charles le duc de Bourgne et Brabant, conte de flanders etc.

Madame Isabaul sa mere etc

Madamoselle de bourgne sa fille etc

These names identify Charles the Bold (1433–1477) in gold script; Isabella of Bourbon (1436–1465) in blue; and their daughter Mary of Burgundy (1457–1482) in red. The gold script of the duke’s name may be why the manuscript is known as the Guldenboek.29 These names set a terminus post quem and a terminus ante quem: the manuscript must have been begun between 15 June 1467, when Charles became duke, and 3 July 1468, when Charles married Margaret of York. In fact, however, Charles must have founded the confraternity in 1467, because in that year, many members of his entourage joined it, as is clear from the marginal notes, discussed below. The entries for Charles, Isabelle, and Mary appear to be written in the same Burgundian bâtarde as the rest of the original campaign of writing.

Their names head up the extensive list of members’ names. Although the page has layer upon layer of scribal additions, with some analysis one can see that the first names written were on fol. 3r and began with these:

Monsieur de Chambray

Monsieur de Liège

Monsieur de Humbercourt

Monsieur de Fiennes

Monsieur Christian de Diguome

Monsieur Rehan de Luxembourg

Monsieur Marquis de Farare

Monsieur Anthoen de Luxembourg, Comte de Rossi

Monsieur Ian de La Viesville

Monsieur de Careny

Pierre de Beffremont, Comte de Charny

Monsieur de La Hameyde

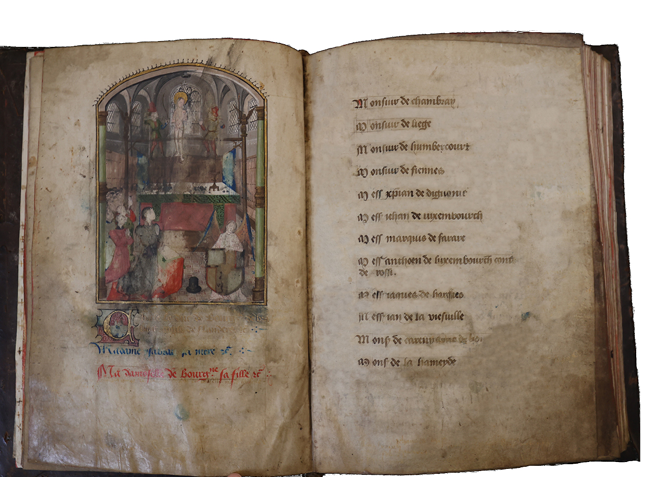

These are members of the ducal entourage, several with the rank of count. The scribe reflected their social standing by inscribing their names in a particular way, which is now obfuscated by later inscriptions made by many hands. A digital reconstruction of the opening when it was first inscribed in 1467 reveals that a single scribe has written their names in a precise bâtarde, leaving one blank line between each name, as if to underscore the real estate they controlled, on land and on parchment (Fig. 64). (In this reconstruction, no effort has been made to restore the image to its fresh state.) This sparse page layout exuded dignity and exclusivity.

Fig. 64 Opening of the Linkebeek Guldenboek with an image depicting Charles the Bold before an altar dedicated to St Sebastian, Brussels, 1467 and later. Linkebeek, Parish Church, unnumbered manuscript, fols 2v–3r. Above: unprocessed photo; below: digitally masked photo to show only the original inscriptions from 1467

This way of inscribing names, skipping a line between individuals or family groups, went on for several more folios (until fol. 6r), as a further digital reconstruction shows. (Fig. 65 shows an opening with members’ names, and a digitally masked version of the same opening.) This way of inscribing members’ names preserved the sparse dignity of the page, emphasizing large margins, luxurious in their wastefulness.30 It suggested that members formed part of an exclusive club, whose foremost member was Charles the Bold.

Fig. 65 Opening of the Linkebeek Guldenboek with members’ names, Brussels, 1467 and later. Linkebeek, Parish Church, unnumbered manuscript, fols 4v–5r. Above: unprocessed photo; below: digitally masked photo to show only the original inscriptions from 1467

After a few folios, the scribe abandoned this way of listing names and slid into a more compact method, without skipping a line between each. Reviewing the first opening with names again (fols 2v–3r), we can see that after the inaugural wave of inscriptions in 1467, more members of the ducal entourage joined the confraternity. Instead of having their names inscribed on the blank sheets at the end, they had their names squeezed into the front, in the spaces that had deliberately been left blank. These added names begin with Monsieur Anthoine bâtard de Bourg, frère notre seigneur, that is, Anthony, Grand Bastard of Burgundy (1421 - 5 May 1504), illegitimate son of Philip III and his mistress Jeanne de Presle. Because he was the half-brother of Charles the Bold, he is designated as “frère.” The two boys grew up together then remained close. Anthony, a member of the duke’s inner circle, sat for a portrait painted by Rogier van der Weyden wearing his insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece. As friend, ally, and brother of the duke, Anthony’s name was inscribed in the very first open space. He and the other confrères vied to be as close to St Sebastian, Charles, Isabelle, and Mary as possible—similar to the way that the most important people would be buried in churches, as close to the saint’s relics as possible—as if proximity would work some sympathetic magic. Where one’s name touched the page reflected the person’s status.

This analysis shows that the initial scribe attempted to position the names of the duke’s entourage in a distinguished way, with plenty of space around them, but that the next wave of members sought to “jump the queue,” as it were, and gain a privileged position as close to the front as possible. It is unlikely that the original scribe himself took the initiative to fill in the blank lines, since he had deliberately left them blank as part of the page design. Instead, it is more likely that the new confrères would have cajoled a later scribe into placing their names close to Charles the Bold’s. This also implies that the new confrères would have seen the manuscript and witnessed their own names being added to it. Some also took this desire to be close to the duke to an extreme, by having their names added to the folio with the image of the kneeling duke, even turning the book sideways if necessary.

Annotations in the margin next to the names provide further clues about the nobles’ participation in this club. For example, next to the second original name at the top of fol. 3r, Monsieur de Liège, a note reads “lxvij stuivers pour xij ans,” which indicates that in 1467, he paid 12 years’ worth of dues. In the same year—that is, the year Charles the Bold founded the confraternity—Monsieur de Humbercourt and Monsieur de Fiennes each paid ten years’ worth of dues, Monsieur Christian de Diguome paid 11 years’ worth, Monsieur Rehan de Luxembourg paid some amount (but the annotation is too abraded to read), and Monsieur Marquis de Farare paid an impressive 21 years’ worth. In light of these inscriptions, the significance of the note opposite the first original name at the top of fol. 3r, Monsieur de Chambray, becomes clear: it reads “obijt,” indicating that he died before he could pay his dues.

Touching images

The patterns of wear on the two images, which provide some clues about how they were handled, suggest two scenarios. First, an officiant might have read the text aloud to gathered confrères on Sebastian’s feast day and pointed out pictorial elements of the images to those gathered, thereby drawing the audience’s attention in to the image. And second, we saw above that confrères expressed opinions about where their names should appear, which presumes that they had access to the book. It is possible that hundreds of confrères touched the manuscript. In fact, close observation reveals that it was touched in specific and targeted ways. I will treat the two images in turn.

In the first image (fol. 1r), user(s) touched specific areas of the image: Godfrey’s face (signifying his identity), his coat of arms (signifying his nobility), and his book on the red pillow (signifying either his devotion or self-referring to this very manuscript); the naked torso of St Sebastian (who protected believers from the bubonic plague); the longbowman at the left (who holds the tool of the knight and soldier). In other words, users targeted symbols associated with divinity, authority, and knighthood. This shows users’ interaction with both the depicted book and the actual book.

Some of this touching involved a wet finger. The effects are visible on the letter M that initiates the phrase “My noble lord duke Godfrey…” Moreover, the image of the book and the coat of arms have been touched with a wet finger. Someone with a finger-full of black paint has wiped at the lower border, suggesting one or more performances, in which someone made dramatic, mark-making gestures. Except for the wet-touched letter (which, I believe, resulted from a gesture associated with reading), it is difficult to say whether these marks were primarily caused by an official or by confrères. One can imagine that an official would read the text, with its official-sounding prose in Latin and Dutch, to a group of confrères during an annual celebration. One can also imagine that that same official would turn the book to the gathered audience to point out elements of the image, which left finger tracks behind, and that individual confrères would have asserted their status and sense of entitlement by making a mark in the book, in addition to their inscribed names. The conditions for this mark-making on the page therefore remain nebulous.

The second image (fol. 2v) likewise depicts the martyrdom of St Sebastian, but this time set in a church interior. A backlighted photo of the second image reveals that this one, too, was heavily touched (Fig. 66). These are the precise marks of targeted fingers, not the wider strokes of blur caused by entire hands. The handlers avoided some areas, which remain clean, namely the architectural frame and the duke’s hat placed on the floor. It can be deduced that the book was not proffered head-first to new members for oath-taking, for there is no cumulative smearing at the top margins. Rather, individuals have used careful fingers to touch details in the image.

Fig. 66 Folio of the Linkebeek Guldenboek with an image depicting Charles the Bold before an altar dedicated to St Sebastian, Brussels, 1467. Linkebeek, Parish Church, unnumbered manuscript, fol. 2v, photographed with transmitted light

For this interior image, users have targeted the face of Charles the Bold, his entire body, his book, his coat of arms, the faces of the retinue, the body of St Sebastian, the altar below the saint, and the two blue altar cloths, which may have brandished coats of arms. But who touched these areas of the image? One heavily touched detail is telling: users have carefully, and nearly surgically, touched the faces of the duke’s retinue. Although it is conceivable that an officiant would have done this, it is more likely that confrères themselves touched these faces, seeing themselves in the representations. If this hypothesis is correct, then the damage resulted from multiple acts of tactile self-identification. In this scenario, just as some members sought to have their names close to the duke’s, others expressed this wish by touching the duke’s representation, leading to its significant damage. In the same vein, users have also touched the painted and gilt initial at Charles the Bold’s name, to the point where 90% of the blue paint in the initial, and much of the gold on the burnished letters, has been rubbed off. It is as if the letters comprising the duke’s name were apotropaic.

Whereas the first image depicted events from centuries earlier (Sebastian was executed around the start of the fourth century, and Godfrey was born in the eleventh), the second one represents the very recent past, with Charles the Bold venerating St Sebastian and founding the confraternity. Rather than taking place in a landscape, this time the martyrdom appears in a different ontological level: clumsily represented perching on an altarpiece above an altar. Of course, the miniature does not document the event with any mimetic exactitude, but it is tempting to wonder whether the duke, together with the founding members of the confraternity represented behind him, did perform a ceremony at the altar in the oratory at Linkebeek, which by that time had grown into a parish church, to establish the confraternity.

Although the exact nature of the membership ritual is not described in the text—only that members should have their fore- and family names inscribed in the book and pay a stuiver—one can imagine an event, possibly on St Sebastian’s feast day, in which an official would read the confraternity’s history, and then a scribe would add the names of new members into the book. If the image of the altar is any indication, then the ceremony occurred at the St Sebastian altar, and if the patterns of inscriptions and the marks of wear are any indication, then members would have had access to the manuscript and treated it with ceremonial physicality.

In the image, members of the brotherhood appear next to the altar as Charles the Bold founds the organization. The book’s users have deliberately touched his represented entourage, perhaps because they stood for the new members. They also touched the coat of arms and the represented book and wanted to have their names squeezed as close as possible to the represented altar. They have filled in the blank lines that the first scribe left empty and have also added entries in the margins around the text page. They have even gone so far as to turn the book sideways to inscribe their names in the margin next to the miniature. This situation is akin to nobles who wanted to be buried with the greatest possible proximity to the high altar and its relics. By making indelible marks in the book, members reinforced their bonds with the confraternity, its origin, and its revered symbols. This manuscript was anything but static, playing a central role in a club of elites who considered themselves worthy of handling a precious object roughly, and quite literally making their mark in history alongside some of the most famous names in the Burgundian realm. The ritual was a demonstration of entitlement.

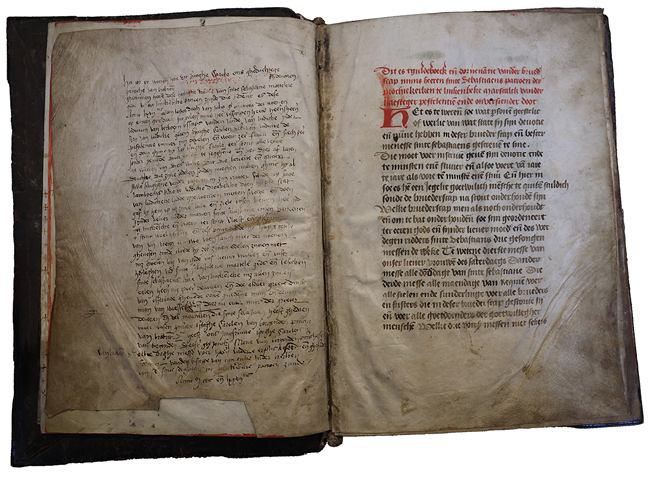

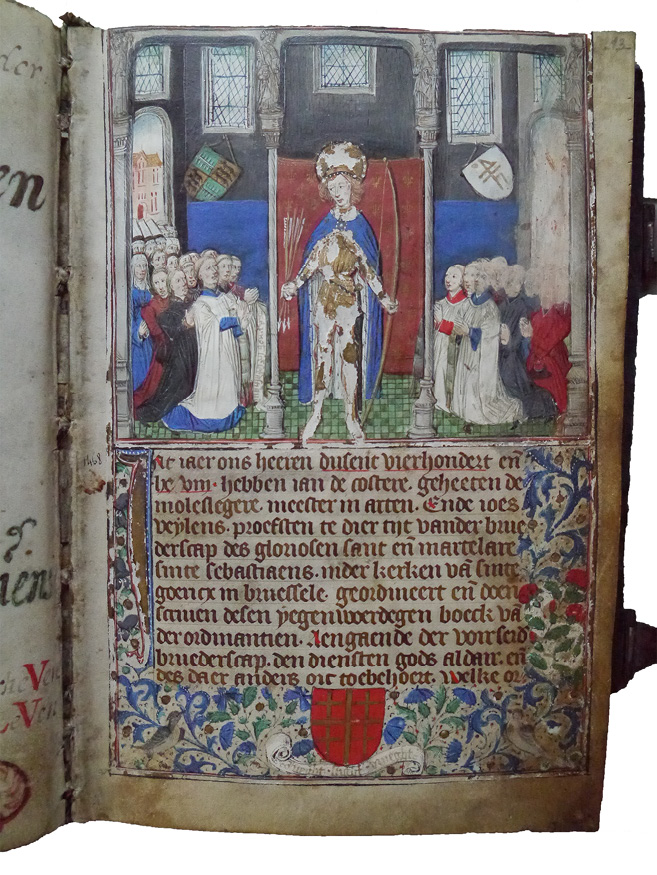

III. St Sebastian at St Gorik’s

Surveying the landscape of confraternity manuscripts, one observes a lack of uniformity in their contents. Remco Sleiderink brought attention to a distinctive manuscript in 2012, which he later placed in the City Archives of Brussels (now identified as “Private Archive 852”).31 The manuscript presents a wealth of historical data and provides insights into the social, artistic, and religious milieu of Brussels. It encapsulates the confraternity’s rules, lists esteemed members such as painter Bernard van Orley, sculptor Jan Borreman, and the printer Thomas van der Noot. It also records an inventory of possessions spanning from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

The confraternity began as a society honoring St Sebastian, with a focus on archery contests, and which was affiliated with St Gorik’s Church in Brussels (known as Gaugericus in Latin and Gory in French). After its foundation, part of the confraternity morphed into a rhetoricians’ guild (rederijkerskamer) called De Corenbloem (Cornflower, or Bluet).32 As noted by Anne-Laure Van Bruaene, De Corenbloem was the only rhetoricians’ guild that originated from a shooting club.33 Their manuscript lists regular members, organized alphabetically. Around 1515, someone appended a list of members of De Corenbloem to the end of the manuscript. (All of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century texts in the manuscript are transcribed and translated below in Appendix 5).

The St Gorik manuscript begins with a page-wide miniature, painted by the Master of Gerard Brilis, which introduces the text chronicling the confraternity’s foundation and regulations (Fig. 67).34 The confraternity at St Gorik’s was founded in 1468, just a year after Linkebeek’s foundation. This manuscript aligns closely with those from Linkebeek and Valenciennes, both thematically and chronologically, as all three portray early group portraits and are dedicated to particular saints. Like the Linkebeek manuscript, it depicts St Sebastian in an interior, flanked by two rows of priests, men, and women, symbolizing the confraternity members. Despite the absence of an oath for members within the manuscript, it is clear that the confraternity’s identity was expressed through other significant means, with the artists and craftsmen listed among its members playing a pivotal role in its cultural and social fabric.

Fig. 67 Folio in the members’ book from the Confraternity of St Gorik’s Church in Brussels, with an image painted by the Master of Gerard Brilis, depicting the members of the confraternity. Brussels, 1468. City Archives of Brussels, Privéarchief 852, fol. 13r. Photo: Remco Sleiderink

All three confraternities, including St Gorik’s, financed regular Masses, with St Gorik’s conducting services every Tuesday at the altar dedicated to St Sebastian. They also had structured systems for collecting membership fees. The row of priests recalls the description from Valenciennes, emphasizing clergy, purses, and money. In the St Gorik image, a prominent purse hangs from the belt of the figure wearing red. The collective figures represent members of the confraternity and form a corporate portrait. Their identity is coded in their garments.35 The act of touching the image of St Sebastian might have been a ritualistic gesture, symbolizing veneration and commitment to the confraternity. This act reinforced the collective identity of the group and the individual’s connection to the patron saint.

The manuscript contains detailed rules and statutes governing the brotherhood’s functions, such as their annual dinner before St Sebastian’s feast day and the structured payment of membership dues. It specifies the nature of Masses to be conducted for members and outlines the financial support available to members’ families upon their death, essentially acting as an early form of insurance. The document also instructs members on how to gain an indulgence at the altar of St Sebastian.

At the manuscript’s conclusion, like the Linkebeek manuscript, there is a list of members’ names, categorized into individual men, couples, and separate lists for widows and single women. This list includes prominent individuals like the painter Bernard van Orley and tapestry weaver Lyoen de Smet. These names not only represent the confraternity’s membership but also highlight the social standing and the high esteem of crafts and trades within the broader context of Brussels society in the decades flanking 1500.

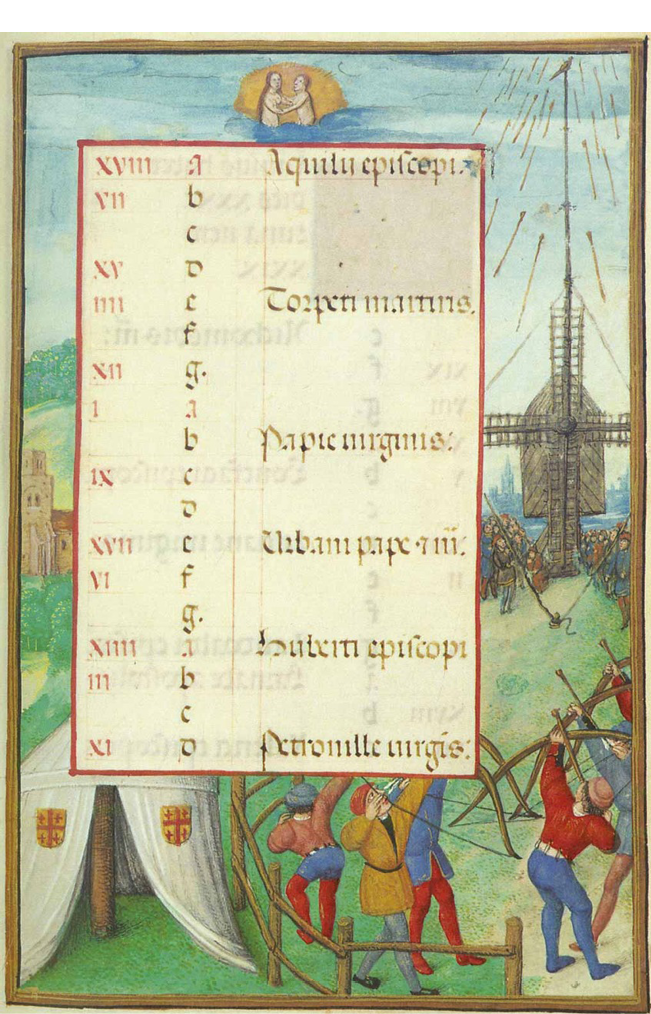

To gain a sense of the confraternity as a social club for shooting, one could consider the representation on a calendar page of the Croy Hours, made in the Southern Netherlands, which shows a shooting club having a match (Fig. 68).36 Participants take aim at a stuffed bird on a pole as a form of competitive theater. They also signal their group belonging by dressing alike (such as the confraternity members of Valenciennes). Male members of St Gorik’s confraternity did more than feed the poor, pay for Masses, and hold banquets: they also engaged in ceremonious social activities around military play and demonstrations of masculinity.

Fig. 68 Calendar page in the Croy Hours, with a shooting contest in the margin, ca. 1500–1520, Southern Netherlands. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 1858

Coda

Signs of wear in manuscripts for confraternities reveal different and specific micro-cultures for individual groups, yet they share common functions. Some confraternity manuscripts have a strong memorial function, since their raison d’être was to ensure prayers for deceased members’ souls, and the inscribed names within them—which then become part of the text—share characteristics with necrologies. The ritualistic significance of having one’s name recorded in such books was particularly pronounced in the Linkebeek and St Gorik’s confraternities.

Linkebeek had a clear connection with the court, St Gorik’s with patrician families, and Valenciennes with men wealthy enough to afford seven ceremonial outfits. Linkebeek and Valenciennes were written in bâtarde script, associated with the French and Burgundian courts. Linkebeek and St Gorik’s, which featured registers of members’ names within their respective manuscripts, included both men and women, in contrast to Valenciennes, which welcomed only men. St Gorik’s emphasized support for widows, the elderly, and charitable acts. Valenciennes, which focused on the procession of relics, was also characterized by its numerous rules regarding attire and the maintenance of standard colors.

The following chart presents a summary of the three manuscripts’ contrasting features:

Of course, these three confraternities, which all had books at their respective centers, represent but a fraction of the confraternities that existed throughout Europe. Contrasting them reveals some of the diversity among their purposes, reflected in diverse patterns of use across their respective manuscripts.

Images in both the Linkebeek and St Gorik manuscripts depict groups of people flanking a saint—in both cases, Sebastian. In each of these manuscripts, images had a role in creating group identity: members physically interacted with the images in ways that reinforced their social cohesion. New members adopted certain visible gestures with the book that would seal their identities as confrères. The role of the book expanded: it was both prescriptive and descriptive, and it formed an object around which group identity could be established with authority. These rituals were performed for members and their new peers and helped to forge horizontal bonds.

Several trends have emerged from these investigations. First, the pattern of wear in a communally used manuscript is diffuse when multiple people each touch the book (or an image within the book) one time. Second, that groups of people imitate their forerunners by touching in approximately the same place and manner. This is related to conscious conformity that smooths social bonding. Third, that rituals of joining groups involve making large, visible gestures that firmly assert one’s fealty to a saint and a group which that saint represents. A fourth trend relates to constructing invented traditions. To do this, a group might emphasize its backstory (as in the case of Linkebeek), or build a ritual around an old manuscript (as in the case of the Chapter of St John writing oaths into a 200-year-old manuscript, as discussed in the previous chapter). One of the most striking examples of this tactic occurred in twentieth-century Chicago, when gangsters purportedly took oaths on a ninth- or tenth-century lectionary written in Greek. The “Gangster’s Lectionary” is now in the University of Chicago Library.37 The use of a ceremonial, millennium-old book written in a language from “old Europe” underscored the gravity of the mobsters’ “blood oath,” their deference to religion, family, and tradition, and the life-or-death strength of their bond to the mob boss.

1 Paul Trio, “Confraternities as Such, and as a Template for Guilds in the Low Countries during the Medieval and the Early Modern Period,” in Konrad Eisenbichler (ed.), A Companion to Medieval and Early Modern Confraternities (Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition, 83) (Brill, 2019), pp. 23–44, argues for the distinction of the terms confraternity (broederschap, brotherhood), guild (gilde), and company (gezelschap). In the manuscript under discussion here, the terms broederschap and gildeboeck are both used. In the same volume, see also Konrad Eisenbichler’s overview of confraternities in his introduction. See Gervase Rosser’s essay for the meaning of the term “confraternal,” referring to the ideal of Christian brotherhood that was intended to establish a relationship among the members.

2 Gisela Drossbach and Gerhard Wolf (eds), Caritas im Schatten von Sankt Peter: der Liber Regulae des Hospitals Santo Spirito in Sassia: Eine Prachthandschrift des 14. Jahrhunderts (Verlag Friedrich Pustet, 2015); and Gisela Drossbach, “The Roman Hospital of Santo Spirito in Sassia and the Cult of the Vera Icon,” in The European Fortune of the Roman Veronica in the Middle Ages Amanda Murphy et al. (eds) (Convivium Supplementum) (Brepols, 2017), pp. 158–67, with further references. The folios of the Sassia manuscript have been cut apart and mounted onto paper blanks. It is possible that this was done because the manuscript was so worn at the bottom from being proffered that it required urgent and heavy-handed conservation.

3 J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words (The William James Lectures) (Clarendon Press, 1962).

4 For images and bibliography of the manuscript, see https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc50635h. Additionally, Agnès Bos, “Le livre des évangiles de l’ordre du Saint-Esprit. Redécouverte d’un manuscrit,” Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France (2022), pp. 34-58, has shown how such rituals and manuscripts continued to operate into the sixteenth century and beyond.

5 Until these manuscripts are restored and digitized, they are difficult to consult or study. For now, see Massimo Medica, Haec Sunt Statuta. Le corporazioni medievali nelle miniature bolognesi (Rocca di Vignola, with Franco Cosimo Panini, 1999).

6 Alessandra Gardin, “Presenza di Immagini Religiose in Codici Laici,” Il codice miniato: rapporti tra codice, testo e figurazione, Melania Ceccanti and Maria Cristina Castelli (eds), Storia della miniatura: studi e documenti 7 (Leo S. Olschki, 1992), pp. 375-385.

7 Patrick M. de Winter, “Bolognese Miniatures at the Cleveland Museum,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 70, 8 (1983), pp. 314–51. De Winter notes that the same arrangement of three coats of arms appears below a miniature depicting Our Lady of Mercy in a frontispiece from the Register of the Corporation of the Apothecaries, also painted in the late fourteenth century, but cut out and redeployed in a register of 1481, also in the Bologna Archives. Both miniatures were created around the same time and for the same guild. Analagous motifs (Christ crucified, above three shields, including two referring to the guild) appear in the Statutes of the Silk Workers for 1424-1589 (Bologna, Archivio di Stato, Ms. 59), and the Statutes of the Salt Sellers for 1376-1403 (Bologna, Archivio di Stato, Ms. 15).

8 The same heraldic elements appear in the Register of the Apothecaries of Bologna of 1481-1759 (Bologna, Archivio di Stato, Ms. 44).

9 Diane Wolfthal connects this leaf with the new financial culture of Bologna after 1376, and contextualizes it with oaths of office for coiners and minters. See Wolfthal et al., Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality (Morgan Library, 2023), pp. 165-168.

10 Bologna, Archivio di Stato, Ms. 27. C, fol. 1v, reproduced in Gardin, p. 382

11 For a description and bibliography, see https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/1095S9

12 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Morrell 25, Liber jurament⟨i⟩ magistri wardorum et fraternitatis sutorum vestiariorum. See Summary catalogue of manuscripts in the Bodleian Library relating to the city, county and University of Oxford; accessions from 1916 to 1962, ed. P. S. Spokes (1964), p. 144.

13 Guilds also formed, but membership for these was based on a shared trade and had a different form of entrance procedure; guilds fall outside the current discussion.

14 James B. MacGregor, “Negotiating Knightly Piety: The Cult of the Warrior-Saints in the West, ca. 1070-ca. 1200,” Church History, 73(2) (2004), pp. 317–45.

15 On Valenciennes, BM, Ms 536, fol. 28r (the final folio of the written text), there is an added note, possibly from the sixteenth century, indicating that the current manuscript is a copy of one from 1423. The earlier manuscript does not survive or has not been identified.

16 Auguste Molinier, Catalogue général des manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques de France. Départements—Tome XXV. Valenciennes (Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1894), cat. 536. Dominique Vanwijnsberghe briefly mentions the manuscript in “La miniature à Valenciennes, Etat des sources et aperçu chronologique de la production (fin XIVe—1480),” Valenciennes aux XIVe et XVe siècles. Art et histoire, Valenciennes, Presses universitaires de Valenciennes, 1996, pp. 181–200, here: p. 193, fn. 57. See also Lucie Laumonier, “Medieval Confraternities: Prayers, Feasts, and Fees,” Medievalists.net. https://www.medievalists.net/2021/11/medieval-confraternities-prayers-feasts-and-fees/. The manuscript is fully digitized at https://patrimoine-numerique.ville-valenciennes.fr/ark:/29755/B_596066101_MS_0536.locale=fr

17 The oratory burned in 1546, but its Romanesque baptismal font survived, for which see Jean-Claude Ghislain, “La cuve baptismale romane de style Ardennais de Linkebeek (Brabant),” Annales du cercle historique et folklorique de Braine-le-Château, Tubize et des régions voisines, Vol. VIII (1988–1993), pp. 153–175, who shows that it is one of about a hundred surviving baptismal fonts made in the Ardennes for export. The object was conserved in 1947–1948, when it received its current stone pedestal and copper lid.

18 Not all the pilgrims came of their own volition. According to a record of the archers’ guild in Mechelen, in 1433 it was decreed that any member who had gambled would be required to make a pilgrimage to Linkebeek and to give a pound of wax and eight stuivers to the shrine. See Hugo van der Velden, The Donor’s Image: Gerard Loyet and the Votive Portraits of Charles the Bold, trans. Beverley Jackson (Brepols, 2000), p. 183, n. 104.

19 Linkebeek, parish church, unnumbered manuscript. The manuscript was confusingly foliated in multiple campaigns. See Appendix 4 for a codicological overview. For an art historical analysis of the manuscript, see Dominique Vanwijnsberghe, “Charles le Téméraire et le Livre d’or de la confrérie Saint-Sébastien de Linkebeek”, in Quand flamboyait la Toison d’Or: le Bon, le Téméraire et le chancelier, exh. cat. (Beaune, 2021), pp. 243–245. See also Denis Coekelberghs, ed. Catalogue de l’Exposition Trésors d’Art des Eglises de Bruxelles, vol. 56, 1979 (Brussels: Société Royale d’Archéologie), no. 31.

20 The manuscript attests to the great popularity of the confraternity, from the late fifteenth century until 1732, which is the last date entered in the book. According to undated internal documents at the parish church at Linkebeek, written by Marguerite Berghmans and Alex Geysels, Humbertus Precipiano, the archbishop of Mechelen, gave 40 days’ indulgence in 1702 to those who venerated St Sebastian in Linkebeek. Pope Gregory XVI also gave an indulgence to the shrine’s pilgrims, according to written records in 1833 and 1834, possibly in response to the cholera epidemic that began in 1831. E.H. Nijs, the pastor at Linkebeek from 1953–1973, encouraged the confraternity.

21 It is possible that the story of Charles’s miraculous cure was apocryphal, and that in fact, he patronized the oratory because St Sebastian was patron of archers. Charles fancied himself a proficient bowman.

22 For an extensive discussion of this statuette in the context of Gerard Loyet’s work, see van der Velden (2000), pp. 61, 155, 178, 182–184, and 323–24 (doc. 75).

23 van der Velden (2000, p. 182).

24 See van der Velden (2000, passim).

25 A range of coins circulated in the late medieval Europe, because of the various regional and national authorities that minted currencies. The relationship between these units varied across time and over the region. The stuiver, mentioned in this text, circulated in the Low Countries. It was worth 16 penning or pennies. The florin, or the gold florin, was first minted in Florence in 1252. It was adopted broadly because of its consistent gold content and weight. Sols, which circulated in France and other regions, originally referred to the solidus coin of the late Roman Empire. In the late Middle Ages in France, a sol was worth 12 deniers. The relationship between the florin, stuiver, and sol would have depended on the exchange rate. For an exhaustive study on this topic, see the 20+ volumes of Medieval European Coinage published by Cambridge University Press.

26 Dominique Vanwijnsberghe made this attribution. For the Master of Johannes Gielemans, see James Marrow’s discussion of the moral and didactic treatises illuminated by this artist, now in the New York Public Library, Spencer 17, in Alexander et al. (2005), cat. 96, pp. 407–412.

27 According to his vita, Sebastian survived the shooting by arrows (ordered by Diocletian) and was martyred some time later after he stood up to Diocletian, who then had Sebastian clubbed to death. Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints / Jacobus de Voragine., Eamon Duffy (ed.), trans. William Granger Ryan (Princeton University Press, 2012), Chapter 23.

28 The arms of Charles the Bold (which appear in his portrait on a round panel, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, SK-A-3836) are as follows: quartered, 1 and 4, three gold fleurs-de-lis on a blue field; 2, divided vertically, i, three diagonal gold bands on a blue field, ii, a gold lion rampant on a black field; 3, divided vertically, i, three diagonal gold bands on a blue field, ii, a red lion rampant with gold claws on a silver field; an inescutcheon with a black lion rampant with red tongue and claws on a gold field. See https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-3836/catalogue-entry

29 Alternatively, the book may have originally been in a golden binding or one covered in gold-shot cloth, just as the “red books” discussed in Vol. 1 were originally in red bindings.

30 Catherine Reynolds, “The Undecorated Margin: The Fashion for Luxury Books without Borders,” in Flemish Manuscript Painting in Context, Thomas Kren and Elizabeth Morrison (eds) J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006), pp. 9–26.

31 Remco Sleiderink, “Sebastiaan en Swa. De zoektocht naar het cultureel erfgoed van de Brusselse handboogschutters,” Madoc: Tijdschrift over de Middeleeuwen, 27 (2013), pp. 142–53.

32 Remco Sleiderink, “De schandaleuze spelen van 1559 en de leden van De Corenbloem. Het socioprofessionele, literaire en religieuze profiel van de Brusselse rederijkerskamer,” Revue Belge de Philologie et d’Histoire / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis, 92 (2014), pp. 847–875.

33 Anne-Laure van Bruaene, Om beters wille: Rederijkerskamers en de stedelijke cultuur in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden (1400–1650) (Amsterdam University Press, 2008), p. 47. Jean-Dominique Delle Luche, in Des amitiés ciblées: Concours de tir et diplomatie urbaine dans le Saint-Empire, XVe-XVIe siècle. Studies in European Urban History (Brepols, 2021), analyzes urban shooting contests in the fifteenth and sixteenth-centuries. Competitive shooting began in the 1430s and continues today. Delle Luchedescribes them as friendship clubs and “laboratories of masculinity.” He does not discuss the manuscript from St Gorik’s.

34 Hanno Wijsman and Dominique van Wijnsberghe have made this attribution. For this artist, see James H. Marrow, “The Master of Gerard Brilis,” in Quand la Peinture Était dans les Livres: Mélanges en l’Honneur de François Avril, Mara Hofmann and Caroline Zöhl (eds) (Brepols, 2007), pp. 168–191.

35 The illumination can therefore be seen in relation to certain Netherlandish panel paintings with similar themes, for which see Ingrid Falque, “Visualising Cohesion, Identity and Piety: Altarpieces of Guilds and Brotherhoods in Early Netherlandish Painting (1400–1550),” in Material Culture: Präsenz und Sichtbarkeit von Künstlern, Zünftenund Bruderschaften in der Vormoderne. Presence and Visibility of Artists, Guilds and Brotherhoods in the Pre-Modern Era, Andreas Tacke, Birgit Ulrike Münch, and Wolfgang Augustyn (eds) (Artifex. Quellen und Studien zur Künstlersozialgeschichte / Sources and Studies in the Social History of the Artist) (Michael Imhof Verlag, 2018), pp. 190–209.

36 Otto Mazal and Dagmar Thoss, Das Buch der Drolerien: (Croy Gebetbuch); Fabelhafte Welt in Miniaturen (Faksimile Verlag, 1993).