Chapter 3: Educators and Learners

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.03

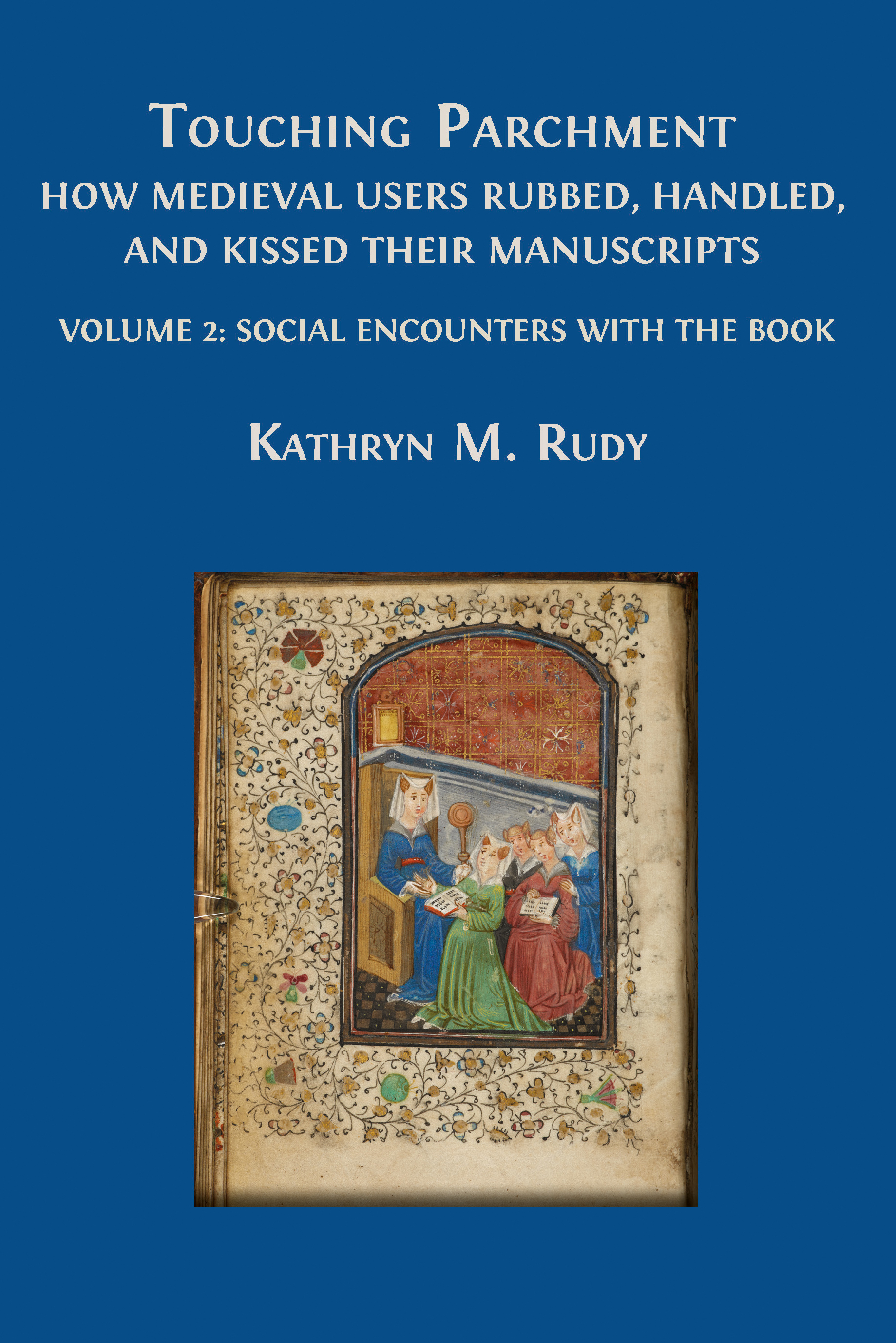

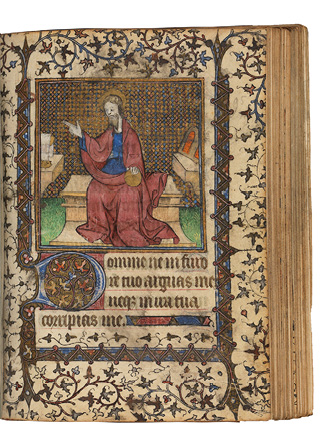

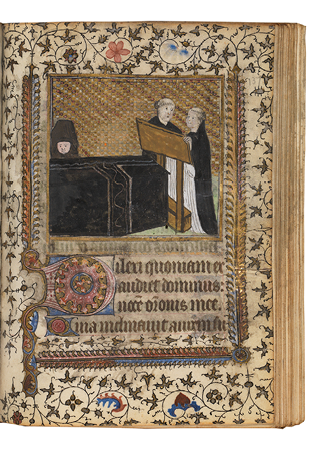

An image made for a private prayer book constructed for a family in the Southern Netherlands around 1460 shows Christ teaching the apostles how to pray (Fig. 69). The apostles gather around Jesus, whom they see as a teacher and leader. He presents a book that serves as both his source of authority and his prop. He turns the book to his audience and draws them into it. Positioned at the center of the painting, the open book mediates between teacher and students. The book’s size ensures that the students cluster around it, forming a tight social circle of learning.

Fig. 69 Opening in a Book of Hours illuminated by the Masters of the Gold Scrolls, depicting Jesus teaching the Apostles to pray. Ghent or Bruges, ca. 1460. LBL, Add. Ms 39638, fols 34v–35

Over the past century, manuscript scholars have investigated the intricacies of copying, by which they usually mean tracing an artist’s pictorial models or investigating how an artist translates visual models from one context to another. Some of these studies have brilliantly explicated aspects of the working processes of medieval illuminators.1 They have all concentrated on the production of manuscript copying, whereas I aim to steer the conversation to its reception. How did medieval people learn to handle their books and emulate others’ behaviors? This shift in focus underlines the importance of understanding the lived experiences of medieval readers.

In learning contexts, whether for young students or adults, a master would often engage with learners through a performative demonstration using a book. In this study I do not analyze scholars’ manuscripts, in which learned readers left notes for themselves and for future readers in the margins as glosses or commentary, in what is in effect asynchronous learning. Others have thoroughly covered that topic.2 Instead I will consider learning situations structured as live performances around a book: young children learning to read, older children learning tenets of the faith, and a duke learning his catechism. These situations transferred book-touching behaviors from educator to student.

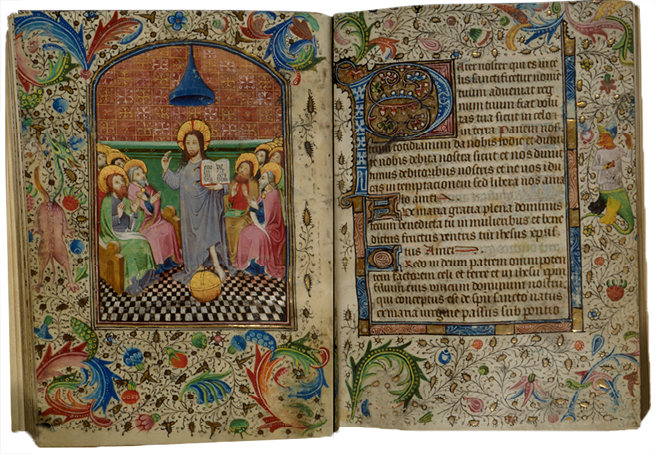

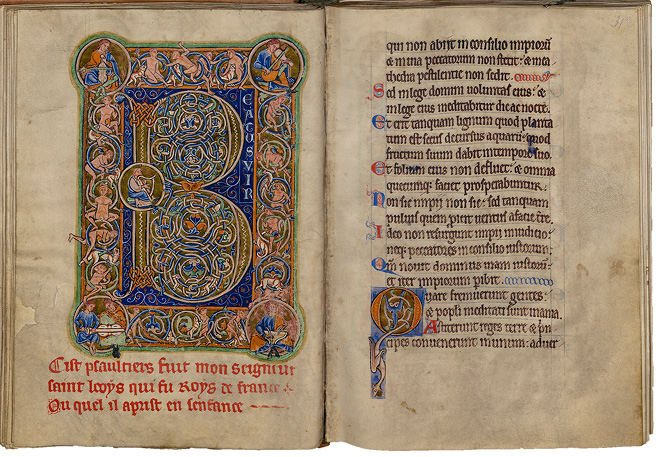

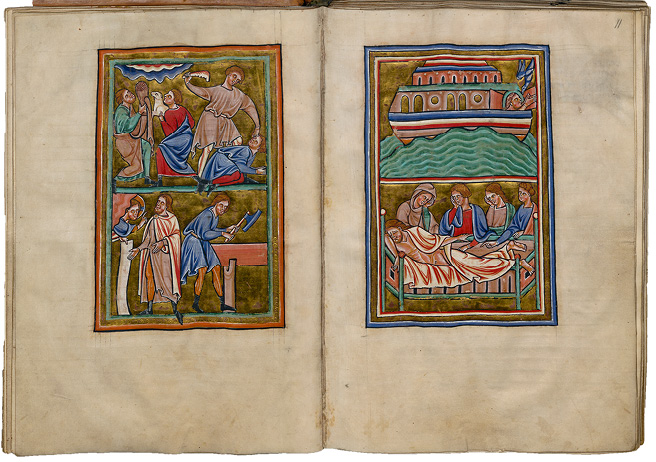

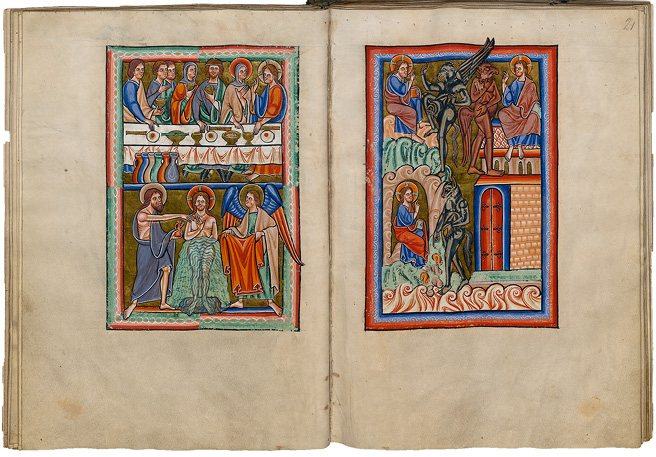

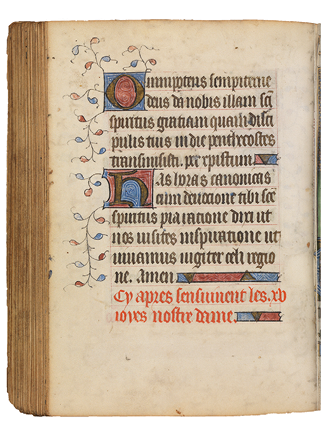

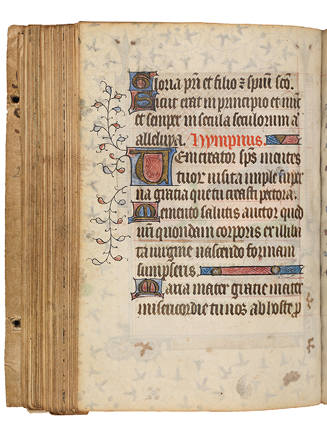

Before ca. 1400, the Psalter served as the predominant educational tool for children. For example, the childhood Psalter of Louis IX (1214–1270), preserved in Leiden, has an inscription at the foot of the Beatus page indicating its use in teaching Louis to read (Fig. 70).3 The Psalter opens with a calendar and a series of full-page miniatures, each bisected into two registers, showing the major stories from the Old and New Testaments. These include an opening with stories featuring Cain and Abel on the left, and stories of Noah on the right (a raven returning to the ark, and Noah’s death at the age of 950 years, surrounded by his three sons) (Fig. 71). The extensive and colorful picture cycle would have appealed to the young boy and would have contributed to his education as king and eventually saint. The pictures are still in quite good condition, except for the image depicting devils tempting Jesus in the desert (Fig. 72), on which a user has rubbed out the devils, particularly targeting their heads. It is possible that Louis’s teacher gestured angrily at these devils to offer a moral component to the recounting of the story. The tangible interactions with this psalter offer a glimpse into the emotional and instructional practices of medieval learning.

Fig. 70 Beatus page and opening of the Psalter text in the Psalter of St Louis. Paris, ca. 1220. Leiden, UL, BPL 76A, fol. 30v–31r

Fig. 71 Manuscript opening with the murder of Abel by Cain, and Noah’s ark in the Psalter of St Louis. Paris, ca. 1220. Leiden, UL, Ms. BPL 76A, fols 10v–11r

Fig. 72 Manuscript opening with the Last Supper, Baptism, and Temptation of Christ in the Psalter of St Louis. Paris, ca. 1220. Leiden, UL, Ms. BPL 76A, fols 20v–21r

While Louis’s Psalter is precious, gilded, exclusive, and based on an adult book type, in the later Middle Ages the possibilities of manuscript types for children expanded as people realized that colorful images and easier texts served as effective entrées into the world of letters. Better pedagogy created a virtuous circle with increased literacy, where the two spiraled upward in tandem. They were but two of many forces that helped to create a new wave of readers who, in the 1450s, would demand the printing press to feed their bookish needs.

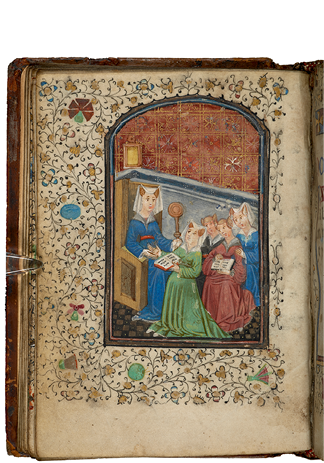

Manuscripts crafted or adapted for children often incorporated alphabets, accessible texts, and captivating imagery—either portraying children in learning situations or featuring elements appealing to a young audience (with bright colors, shapes, animals).4 Learning to read involved shaping a child’s body in the presence of a book and adopting certain didactic gestures—such as crossing oneself before reciting the alphabet. One children’s manuscript has a full-page miniature showing girls holding out their books to read aloud to a teacher (London, BL, Harley 3828; Fig. 73). This image is all about reading aloud with an audience, but the roles are reversed: usually, the seated authority would wield the book and read aloud, but here the kneeling underlings do the reading, while the “audience” is seated, older, and authoritative. Although this image shows a fiction, both the image and the manuscript containing it (which has an alphabet and easy-to-read, highly illustrated texts) suggest that elite children possessed manuscripts made specifically for their needs, and that learning involved a set of codified gestures.

Fig. 73 Opening in a prayer book with a full-page miniature painted by the Masters of the Gold Scrolls depicting girls learning to read, with an alphabet on the facing folio. Ghent or Bruges, ca. 1445. LBL, Harley Ms 3828, fols 27v–28r

Examining the wear patterns of Harley 3828 reveals certain interactions between its young users and the content. The opening is in general well-worn and grubby (with inadvertent wear). It also brandishes damage from targeted wear. Specifically, several areas of the image have been touched with a wet finger, most notably, the green dress of the first kneeling girl. The kneeling figure in blue has also been touched; did the book’s user consider this to represent the teacher again, this time in the guise of a patient, encouraging helper? One can imagine that the young female owner would have read the book together with her teacher (or mother), and that the instructor would have shown her young charge how to “look at” the pictures by touching them, while identifying the various figures, especially the “student” and the “teacher.” Another area of the opening that may have been touched with a wet finger is the cross that initiates the alphabet, as well as the capital letters. The blue paint, which does not adhere well, has been reconstituted and has stuck to the opposite side of the opening, thereby dappling the background of the miniature with blue. Perhaps the teacher also taught the student to wet-touch the cross, and then to follow the alphabet with her fingers.

Other gestures associated with learning include holding books open and pointing to specific passages within them. This is what is happening in a panel painting showing the twelve-year-old Jesus instructing the doctors of the temple, which was made in 1482 for a church in Biertan, Transylvania (Fig. 74).5 Jesus, elevated in the position of enthroned teacher makes points by gesturing with his fingers. At the upper left, the doctors of temple point to a passage in the open book, as if to acknowledge their conversion. At the upper right, the crowned doctor holds his open, brandished book over his head. This gesture recalls one described by William Durand, in which a Gospel manuscript is raised above the head of a newly installed bishop to demonstrate that the bishop is under the jurisdiction of the holy writ. In the painting, too, the temple doctor marks his conversion to Christianity by demonstrating his subordinate position to the book. Only the figure at the bottom of the frame, occupying a position as if at the bottom of Fortuna’s wheel, has yet to be convinced, and he therefore tears violently at the pages of his book. The thesis of the painting seems to be that how the figures handle their books communicates their moral and intellectual level. Touching open books, pointing at specific items within them, gesturing with them in an animated way—all of these gestures belong to a social culture mediated by books.

Fig. 74 Jesus instructing the doctors of the temple. Painting on panel, ca. 1480. Siebenbürger Church, Biertan, Transylvania.

While early learners might primarily be children, some people continued learning with the aid of a book and a teacher throughout their lives. The lessons became more difficult, the sentences more complex, and the relationship between teacher and student shifted. This chapter explores the reading environment of several manuscripts, each brandishing signs of wear that may have been inflicted during didactic exchanges with a teacher interacting with a student in the presence of a book.

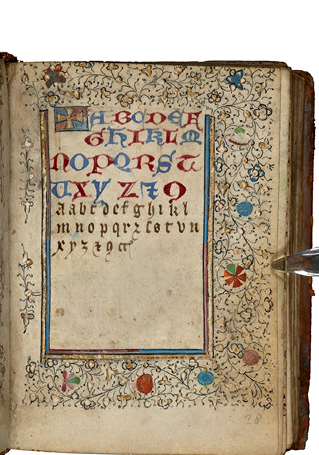

I. Teaching children how to read with manuscripts

What kinds of books stood at the center of micro-learning environments of the late Middle Ages? We have seen that Louis IX received a manuscript prefaced by a series of large miniatures devoid of text in order to introduce him to visualized accounts of basic Bible stories. Other kinds of books contain so-called picture Bibles as prefatory cycles and may have been shown to children as a step toward teaching them to read and write. One manuscript that contains signs that it has been used this way is MJRUL, Ms. French 5, a thin volume made in France or in Francophone England in the first half of the thirteenth century, whose 48 extant folios contain nothing but full-page pictures drawn from the Old Testament. The series opens with God creating the world (Fig. 75).6 Some of the folios have gone missing, which attests to its hard use: the images were of such interest that someone dismembered the book to isolate and own some of them, which is a strong testament to their enthusiastic reception. In this section, I consider this manuscript’s content and potential use.

Fig. 75 Full-page miniature depicting God creating the world. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 1v

A shiny, colorful world

Scholars have had difficulty categorizing these and related autonomous booklets of images, with the two most frequent categories for these items being either “historiated Bible” or “preface to a now-missing Psalter.”7 These categories reflect the cataloguer’s urge to file manuscripts into existing categories, and to emphasize the primacy of text (rather than images) as a manuscript’s defining feature. In fact, that primacy is already coded in the word “manuscript” itself, which after all means “hand-written.” But rethinking such picture cycles as stand-alone booklets opens up new possibilities for their use.8 Namely, they form part of an oral rather than a written culture, one that is marked by an interlocutor who explains the images.

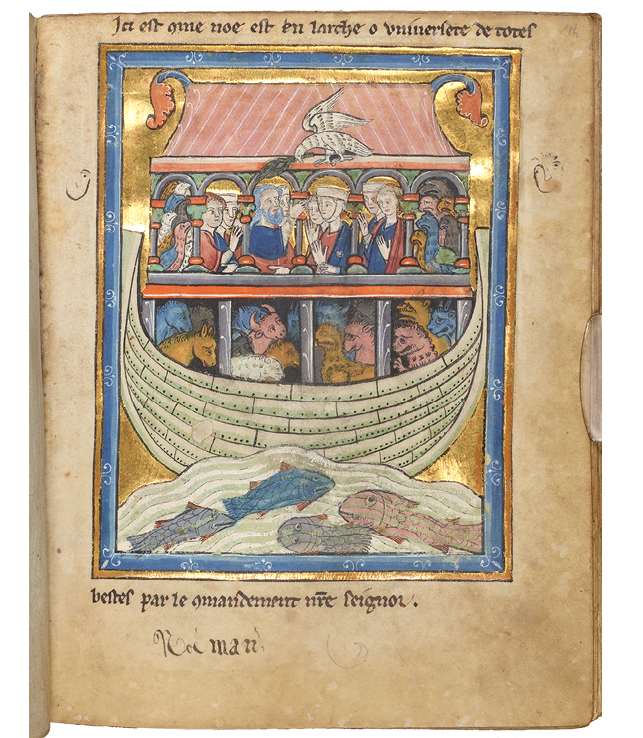

One can imagine that in French 5 the images have been selected for maximum appeal to children—with large figures, colorful elements, gilt backgrounds. Noah’s Ark, a perennial children’s favorite, has been laid out according to simple principles and divisions: the fish at the bottom denote water and thereby set the stage (Fig. 76). The ark is divided into four chambers, which would lend themselves to a discussion with the child about the behavior of herbivores and carnivores. The figures on deck are shown pious and praying, and finally the dove is neatly silhouetted against the canopy as it returns to the ark with an olive branch. The images in MJRUL French 5 are not dissimilar from the prefatory cycle in the Psalter of St Louis, which also contains an image of Noah’s Ark. The Psalter of St Louis provides evidence that dense, Biblical picture cycles were given to children to introduce them to books and stories. It is reasonable to assume that the picture cycles were made in a separate atelier than the textual parts of the manuscript, and that the image cycle could have functionality outside of a text-oriented environment. It was perhaps a child who added small drawings to the lateral margins, which seem to depict the dove returning with the olive branch, in an unrefined and highly stylized way.9

Fig. 76 Full-page miniature depicting Noah’s Ark. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 14r

The individual images have small, simple labels written on them, which describe the scenes.10 These are not instructions to the illuminator, but didactic labels designed to remind the teacher to explain the stories, to teach children to read simple sentences that match the colorful pictures they are looking at. These tituli would be unnecessary in a book for an adult already steeped in Biblical knowledge. They are consistent with the use of the book as a mediator between teacher and student, whereby the teacher uses the book together with the student, in order to identify its narrative.

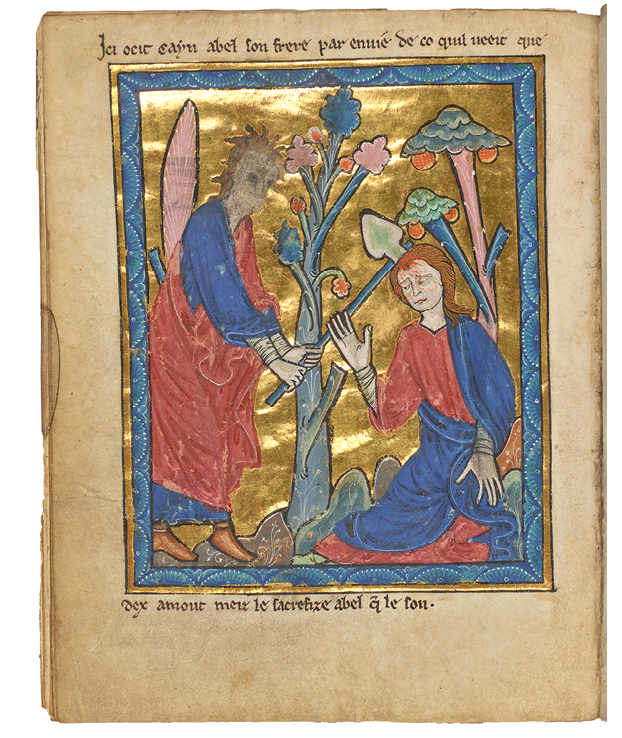

Signs of wear in the book indicate its use as a didactic and moralizing aid. Specifically, ways in which the figures have been rubbed might have stemmed from demonstrating a moral stance toward them. For example, charged lessons have left their marks in the stories of Cain (a farmer) and Abel (a shepherd) offering their produce (Fig. 77), and then Cain killing his brother (Fig. 78). Plausibly, the teacher enacted the stories by animating the images, conveying the narrative action through physical action. In the first image, God favors Abel’s sacrifice, a lamb. The user has rubbed the face of Abel, the face of the angel, and the space between the two (where the gold leaf is abraded down to the red-colored glue), as if drawing and redrawing the connection between Abel and God’s heavenly messenger. In the murder scene, the teacher has rubbed out the face of Cain and has even pitted Cain’s eyes out until they are dark blanks bored into the parchment surface.

Fig. 77 Full-page miniature depicting Cain and Abel making their offerings. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 8r

Fig. 78 Full-page miniature depicting Cain killing his brother. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 9v

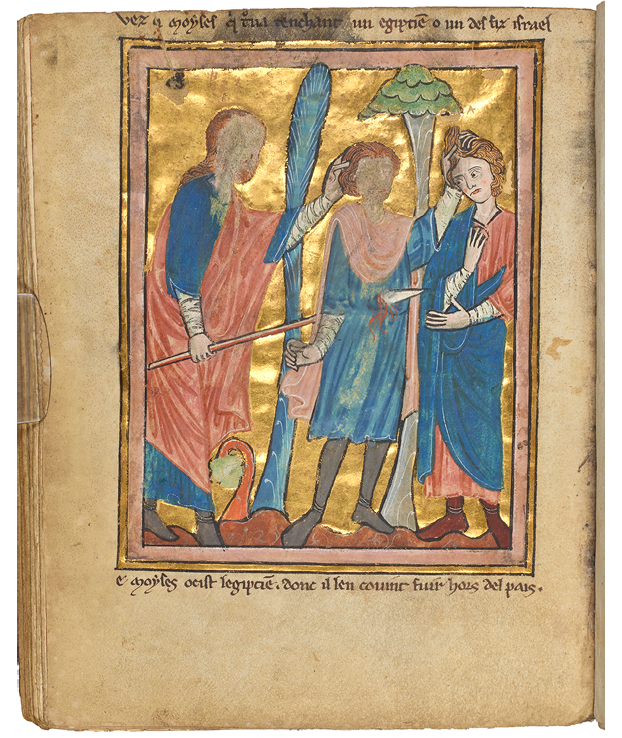

In the scene where Moses kills the Egyptians and spares the Israelites, the teacher has heavily touched various elements in the picture (Fig. 79). The Egyptian is pulling the Israelite’s hair, and the teacher/reader has noted this gesture by touching the hair-pulling hand and smearing the black ink. With even more gusto, the reader/teacher has participated in plunging the lance through the Egyptian’s gut by fingering the bleeding wound at the center of the image. As if to negate this figure after the murder, the reader/teacher has rubbed out the Egyptian’s face, indicating his death. Finally, one can imagine that the teacher—explaining that Moses was also disobedient for committing murder—rubbed the face of Moses too, as if to punish him.

Fig. 79 Full-page miniature depicting Moses killing the Egyptians and sparing the Israelites. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 47v

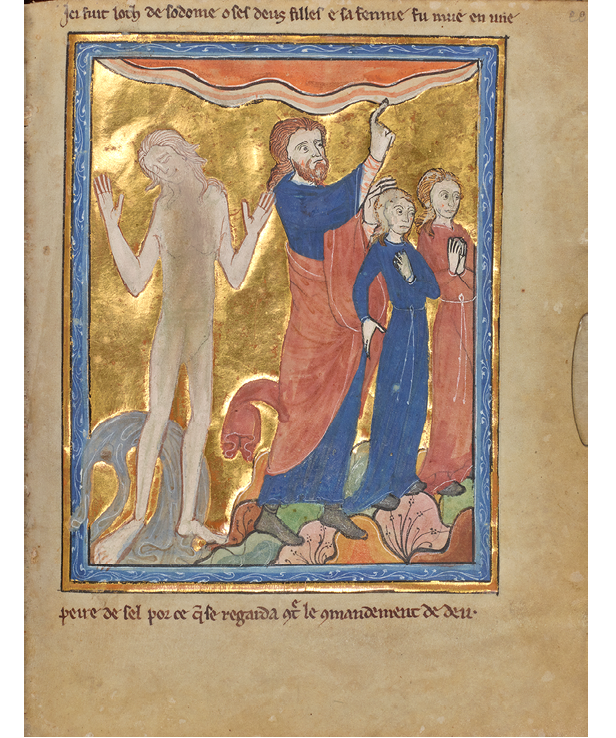

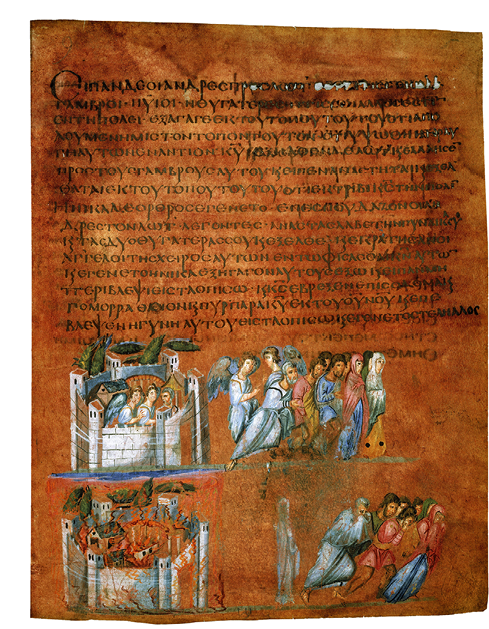

The miniature on folio 20r depicts Lot and his family fleeing Sodom, and his wife turning into a pillar of salt (Fig. 80). When she was turned into a pillar, apparently her clothes fell off her, as her discarded dress lies in a heap at her feet, as if in a swoon. Her pale body against the burnished background became the pictorial element that commanded viewers’ attention: her figure has been rubbed along the entire torso, but the act does not seem to have been motivated by iconoclasm or, more specifically, in order to punish Lot’s wife, as her face has not been attacked. Rather, someone has wet-touched up and down her torso, as if trying to taste the salt. Again, this way of interacting with this subject may have been longstanding and widespread. In the Vienna Genesis, written and painted in the sixth century, the image of the same subject has been rubbed in an analogous way—with a wet finger, as if trying to taste the veracity of the story (Fig. 81).

Fig. 80 Full-page miniature depicting Lot and his family fleeing Sodom. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 20r

Fig. 81 Lot and his family fleeing Sodom, from the Vienna Genesis. Syria, sixth century. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Theol. gr. 31, fol. 5r

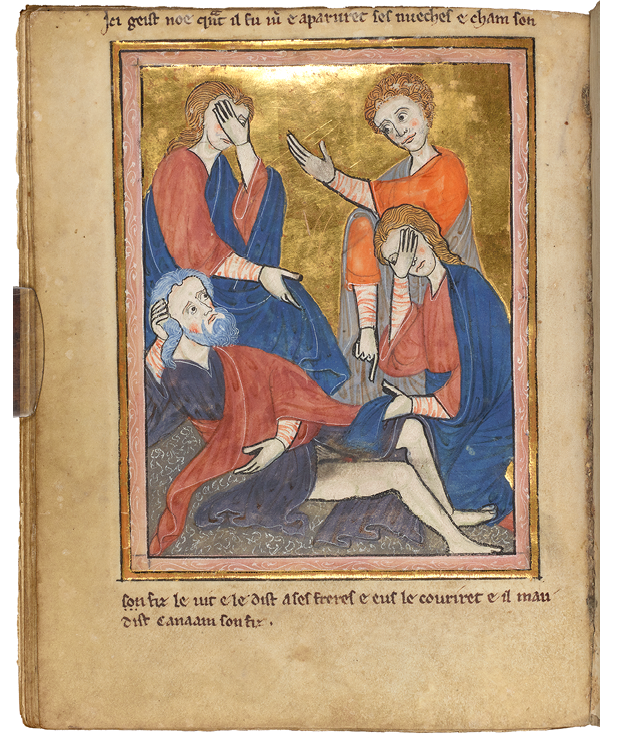

A different motivation, but just as telling, appears at the story of the Drunkenness of Noah in MJRUL French 5: someone (the teacher?) has rubbed out the drunken father’s genitals, as if to ensure that the young reader would not gaze at them as the depicted figures are furtively doing (Fig. 82). All these features—the large images, the short descriptive tituli, the targeted handling—point to a scenario in which this manuscript formed the focus for a series of early childhood reading lessons. Other picture books of the same ilk bear similar marks of use, which suggests a widespread use of books as mediators between teachers and learners.

Fig. 82 Full-page miniature depicting the Drunkenness of Noah. France or England, ca. 1200–1250. MJRUL, Ms. French 5, fol. 15v

A similar scene was rubbed in a twelfth-century Bible from the Northern French Abbey of Saint-Sauveur d’Anchin (Douai, BM, Ms. 2), suggesting that images in different types of manuscripts were also used to mediate between a learner and a teacher. The page-high letter I (In principio) in the Bible contains vignettes from the Old Testament, with Cain and Abel making their offerings, and then Cain killing Abel (Fig. 83).11 With repeated targeted attacks, a user has rubbed out Cain’s face, making it smeary and indistinct. Although the exact conditions under which this damage took place are unknowable, the possibility exists that this illumination served as the locus of a moral lesson between a teacher and a student.

Fig. 83 Incipit of Genesis (In principio), with scenes from the Old Testament, in a Bible. Northern France, twelfth century. Douai, Bibliothèque Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, formerly the Bibliothèque municipal, Ms. 2, fol. 7r, and detail

Learning to read with the fingers

In the fifteenth century, scribes and illuminators increasingly produced books for children. Following precedent in manuscripts such as the Psalter of Louix IX and MJRUL Ms. French 5, child-centered books offered young readers dazzling cycles of full-page illuminations, where the only text was that added by the teacher. One example, the Bolton/Blackburn Hours (York Minster Add. Ms. 2), made in York in the second decade of the fifteenth century, contains an extensive picture cycle (Fig. 84). Although the manuscript has now been rebound and re-organized, the picture cycle formerly prefaced a graded children’s reader and comprised a separate volume.12 Other image-rich manuscripts, which have been hiding in plain sight, indicate that they, too were in fact made for children.

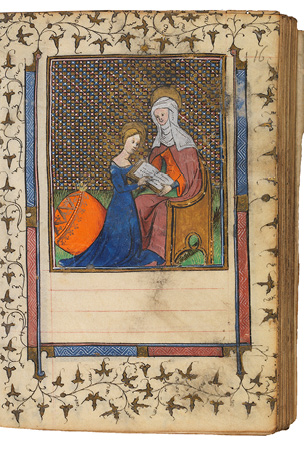

Fig. 84 Opening in the Bolton/Blackburn Hours, with the Arrest of Christ, and St Anne teaching Mary to read. York, ca. 1415. York Minster Library, Add. Ms. 2, fols 34v-35r

One example, examined here in depth, is a Book of Hours made for the Use of Paris, made in the first decade of the fifteenth century (HKB, Ms. 76 F 21).13 This manuscript has some unusual features, which suggest that it was made for teaching a child. Roger Wieck and Kathryn Smith have discussed the programs of texts and images, incorporated into Books of Hours, that were developed for teaching children to read.14 These include the alphabet, Pater Noster, Ave Maria, Credo, and the “grace before meals.” HKB, Ms. 76 F 21 lacks most of these features and stands apart from other manuscripts made for children, yet other features, including the ways in which it has been handled, convince me that it too was used to instruct and engage children. In fact, manuscripts made for children were few and far between, and it is difficult to say that they conform to a particular mold.

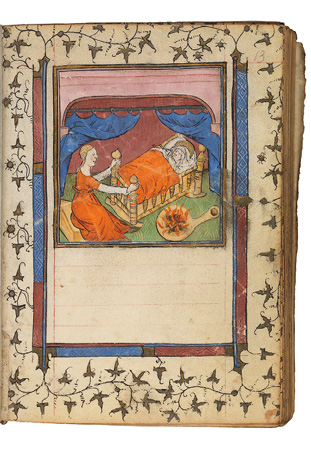

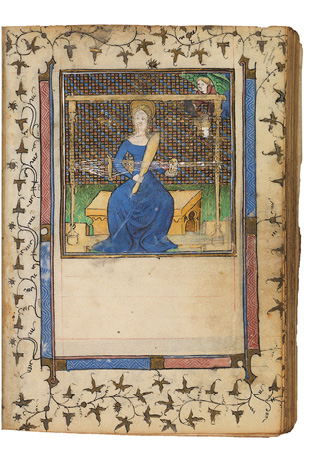

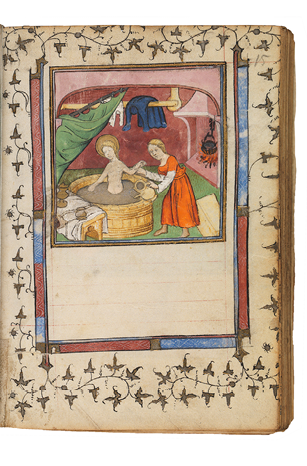

HKB, Ms. 76 F 21 has a lively program of illumination with several images that emphasize children and learning. It opens with a cycle of illuminations depicting the infancy of the Virgin. In one of them, a nurse rocks the nimbed child in a cozy cradle next to a brazier (Fig. 85). The illuminator has conveyed its warmth by showing flames licking upward. In the next one, with a thin waist and careful upright posture, the young Mary learns to weave on a band loom under the instruction of an angel (Fig. 86). In the third, the nurse gives the young Mary a bath (Fig. 87). Although this presents a rare scene of the Virgin’s nudity, it is fully innocent. Next come two scenes of learning. First Mary receives instruction from her mother, St Anne (Fig. 88), and then she receives instruction from an angel, who stands by patiently while Mary points to words and sounds them out (Fig. 89).15

Fig. 85 Opening in a prayer book, with a nurse rocking the infant Mary. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 12v–13r

Fig. 86 Opening in a prayer book, with the Virgin weaving. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 13v-14r

Fig. 87 Opening in a prayer book, with a nurse bathing Mary as a child. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 14v-15r

Fig. 88 Opening in a prayer book, with St Anne teaching Mary to read. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 15v-16r

Fig. 89 Opening in a prayer book, with an angel teaching Mary to read. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 16v-17r

Several aspects of these images are unusual, beginning with their existence at all. They are highly unusual subjects, especially the bath scene and the angel teaching Mary to read. They emphasize tender quotidian moments. Secondly, they lack text. Although their respective pages are ruled for text, they were never filled in, and the user apparently deemed them operational sans text. In this way, they conform to the cycles of pictures given to children, discussed above. Thirdly, they have been handled extensively. To a lesser degree, the rest of the miniatures in the book, which follow a more standard program of images and texts, have also been handled. In what follows, I will analyze the conditions of handling and hypothesize what kinds of rituals and actions would have led to the specific forms of degradation in this book.

In the rocking scene (Fig. 85), someone has rubbed the inner frame near the brazier. Was this person tucking in the Virgin? In the bath scene, someone has rubbed the inner frame near the bench with the towel, possibly with a wet finger, and smudged the paint around. Was this person helping to dry Mary off? Someone has also touched the area near the fire, perhaps to imagine feeling its heat. A different kind of touching occurred at the scene with Mary learning to weave. Here the user has wet-touched the hem of her blue gown several times, perhaps dragging it along the lower part of the image toward the loom. That is consistent with the undisciplined movements of a child. Someone has also touched the gifts (skeins of yarn?) the airborne angel delivers to its enthusiastic recipient. The area of the background below the angel and between the angel and Mary has been so pawed that chunks of the thick paint have flaked off, and the surface decoration of the painted diaper background has worn off. In the image with Mary receiving a reading lesson from the angel, the user wet-touched the blue gown, and touched the diaper pattern in the background.

The most vigorous and sustained touching takes place in the image with St Anne. Photographing the image with transmitted light more fully illuminates the extent and position of the wear (Fig. 90).16 There the user has touched the Virgin’s gown in several places, leaving the blue fabric pocked and the lower margin smudged. The user has also touched the Virgin’s finger as it touches the book. By moving her finger along the page to concentrate the attention on one group of letters at a time, the figure in the image enacts how to interact with the book. I argue that this depicted behavior is also prescriptive, shaping the young user’s performance. One can imagine that the book’s young user would have had a guide—a mother or teacher—helping the child navigate through the book, first using the picture cycle at the beginning to introduce the child to the concept of books holding images, words, and information, containing interpretable memes. In this case, the guide has helped the child see herself in the person of Mary, who is also a young girl struggling to learn to use a book. This guide is also helping the young charge learn two more lessons. One is about curiosity: feel the bath! Feel the heat from the brazier! Feel the pattern of gold and painted squares in the background of the image! The other kind of lesson is about how to interact with books: demonstrate your love for the Virgin by kissing her hem! Help the angel give Mary the skeins of yarn!

Fig. 90 Miniature depicting St Anne teaching Mary to read. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fol. 16r, detail of Fig. 88, photographed with transmitted light

The most likely destinaris for this manuscript, with this particular imagery, is a young girl. Of course, it is possible that some other interested party—a pedophile or someone with a Peter Pan complex—would have felt a particular affinity to this imagery, but I am going to assume that the simplest and most innocent solution is probably the correct one. The rest of the manuscript contains standard images and texts, although the scribe seems to be catering to his young audience by avoiding abbreviations that could cause the new reader to stumble. For example, on fol. 79r the text is laid out in large, neat letters, and words such as “filiorum” and “dominum” are written out entirely, without abbreviations, as if aiding a freshly minted reader.

In the image representing God enthroned, which prefaces the Seven Penitential Psalms, the entire background behind God’s head, chest, and gesturing finger has been rubbed and smeared, with the ink that outlines the gold bar frame having been pulled into the upper margin (Fig. 91). Furthermore, the initial has also been stroked. At the image of the Annunciation, the diaper background has been thoroughly touched, apparently with a wet finger, since the moisture left a stain on the facing folio (Fig. 92). But in the image of the enthroned God, God’s face and head are relatively fresh, and in the Annunciation, Mary’s face is intact. How can this be? Because both faces have been repainted, which also explains why the eyes are too low. Other miniatures in the manuscript have similarly been repainted, most notably the one depicting St Anne teaching Mary to read, probably because deliberate touching had corraded the faces, which prompted a later user to take corrective action.

Fig. 91 Opening in a prayer book at the incipit of the Seven Penitential Psalms, with a miniature depicting God enthroned. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 94v-95r

Fig. 92 Opening in a prayer book at the incipit of the Hours of the Virgin, with a miniature depicting the Annunciation (Mary’s eyes repainted). Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 34v–35r

Users touched images elsewhere in the book. At the image of the Crucifixion, the user has wet-touched several places: the Virgin’s blue garment has at least 20 distinct wet-touched places on it (Fig. 93). The user further touched the bottom of the cross, Christ’s shins, John’s clasped hands, and multiple places in the diaper background, as well as the frame and the initial, some of which have deposited offsets on the facing text page. Notably, the user has touched the line ending at bottom of the verso page: is it possible that the teacher encouraged the child to touch the book, but to aim for non-figurative imagery to prevent further damage?

Fig. 93 Opening in a prayer book at the incipit of the Hours of the Cross, with a miniature depicting the Crucifixion. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 116v-117r

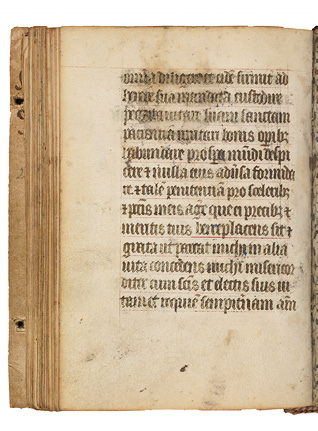

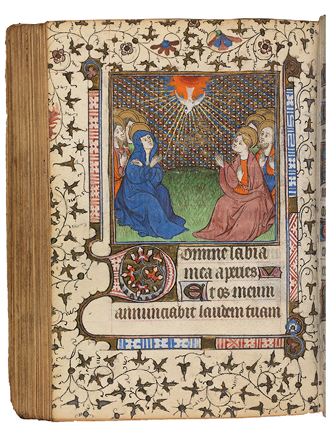

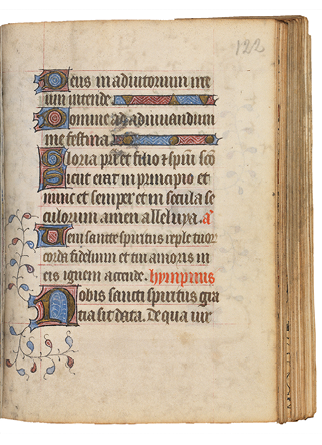

While some images seem to have been touched out of veneration, others have been touched out of a desire to participate in the narrative. For example, at the image of Pentecost, prefacing the Hours of the Holy Spirit, the user has touched the rays of light emanating from the body of the holy dove, as if to trace their trajectory from the dove to the apostles below (Fig. 94). The user has also touched the red and blue swirl of Heaven near the top of the picture. Likewise, the user has stroked Mary’s hair (and along with it, the background behind her head) in the image of the Virgin and Child enthroned (Fig. 95). These traces suggest a reader/user who became tangibly involved with the events from sacred history.

Fig. 94 Opening in a prayer book at the incipit of the Hours of the Holy Spirit, with a miniature depicting Pentecost. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 121v-122r

Fig. 95 Opening in a prayer book at the incipit of the Fifteen Joys of the Virgin, with a miniature depicting the Virgin and Child enthroned. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 125v-126r

A different, and moister, kind of attention has degraded the opening at the incipit of the Vigil for the Dead (Fig. 96). This image has been thoroughly pawed. In particular, someone has repeatedly touched the black-draped coffin, and a large swath of the background has lost its painted detail. (This way of touching recalls how images of the dead were touched in the Grand Obituary of Notre Dame, discussed in Volume 1, Chapter 6.) The face of the hooded monk has been repainted with an inexpressive economy of means. But most notably, there is a significant amount of wet damage that corresponds to the left-side border of the image, and the facing folio. This wet damage is not typical of seepage (for if water had seeped into the book during storage, one would expect that it would have affected multiple folios and would have a brownish leading edge). One possible explanation for this damage is that the teacher taught the young learner to pray for a dead family member, such as a grandparent, and that the moisture resulted from the girl rubbing her saliva, or even her tears, into the book. While this solution makes contextual sense, it must remain a hypothesis.

Fig. 96 Opening in a prayer book at the incipit of the Vigil for the Dead, with a miniature depicting the Mass for the Dead. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 136v-137r

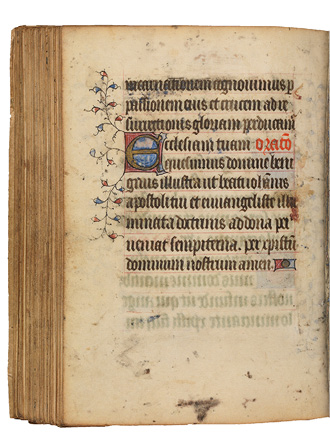

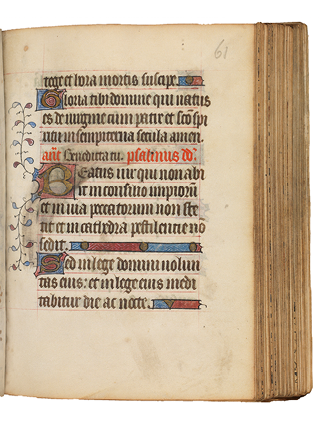

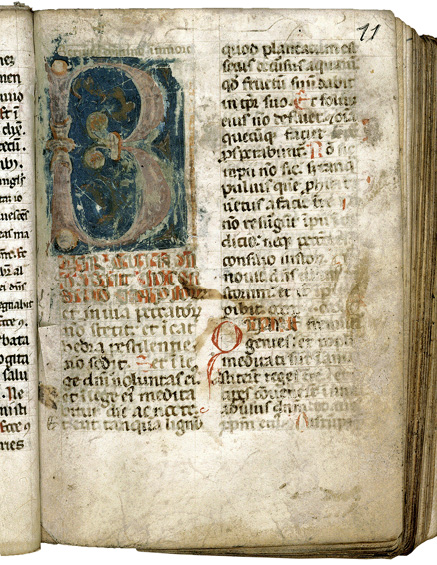

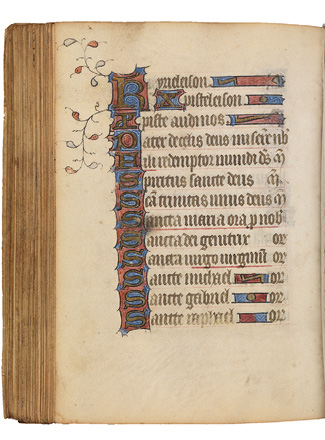

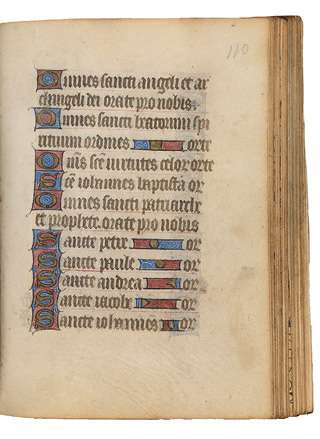

One further way of touching the manuscript becomes clear on certain text pages. At the recitation of Psalm 1 within Prime of the Hours of the Virgin, the user has wet-touched the initial B for Beatus vir (Blessed is the man) (Fig. 97). These are of course the opening words of the Psalter, as with the Saint Louis Psalter, mentioned above. As the initial of the Ur-devotional text in Christendom, this letter B was charged with meaning, and frequently targeted in this way. A large number of Psalters and manuscripts containing snippets of Psalms have had their initials handled. For example, a fourteenth-century Franciscan breviary incorporating Psalms has had its Beatus vir page so heavily damaged through handling that a subsequent user has had to re-inscribe some of the obliterated letters (Fig. 98).17 By analyzing the B smeared in the child’s manuscript, one can hypothesize that touching this letter was part of one’s devotional lessons from a young age. Children would have then applied this behavior to other initials in different book contexts, including but not limited to Beatus initials. The young user of HKB, Ms. 76 F 21 has also touched the initial for Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis within the litany (Fig. 99). Of all the saints listed, only Mary’s initial is touched. Given the physical attention paid to images of Mary throughout the volume—with her blue gown wet-touched innumerable times—this plea to Mary for her prayers can be considered an extension of the mariolatry with which the young learned was inculcated.

Fig. 97 Opening in a prayer book within the Hours of the Virgin. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 60v–61r

Fig. 98 Incipit of the Psalms in a Franciscan breviary. France, fourteenth century. Marseille, BM, Ms. 118, fol. 11r

Fig. 99 Opening at the beginning of the Litany. Paris, ca. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 76 F 21, fols 109v–110r

The following scenario explains why elements of the manuscript were abraded. It was commissioned for a child in France, somewhere in the vicinity of Paris (given that St Geneviève is rubricated in the calendar), around 1400. A teacher, represented as a mother, grandmother, or nurse figure who appears in several of the images, used the book to teach the child the rudiments of Christianity, first by showing her the images at the front of the book, which are oriented toward the domestic world of a wealthy child living in a cold climate. The images forged a connection between the young learner and Mary. In the graduated series of images, the child was first indoctrinated with cozy images of bath time and angelic visitations, which lulled her into blissful domestic comfort, before she confronted the image of God and eventually the potentially terrifying bleeding savior. The teacher also drilled the child in reading by practicing with the Psalms and other texts in the manuscript, which were inscribed with deliberately large letters and minimum abbreviations. Finally, that person encouraged the child to absorb the lessons by making the book and its messages tangible, teaching the child to touch the pages in specific ways: to kiss her finger and transport the kiss to the images; to trace the rays of the Holy Spirit as they shone on the characters from sacred history below; and even to touch the most ineffable character of them all—God.

I dwell on this because such examples provide an explanation for how people learned to handle their books. The learner joined a social-devotional culture that was also an embodied world in which certain cultural techniques, including touching images with a wet finger, were modeled. These lessons encouraged exploration with the fingers, while using the fingers and mouth to interact with the images. It is possible that some of the advanced lessons motivated the child to touch the decoration, or to touch near the venerable figure, which is why the hems and backgrounds are so often wet-fingered. Once we, as modern viewers, develop lenses to see this medieval form of veneration, we will find hundreds of examples of votaries leaving wet fingerprints near objects of affection. For example, in a Book of Hours made in 1411, possibly for Jeanne de La Tour-Landry, the female patron wearing a dress of her coat of arms kneels before the Virgin and Child (Fig. 100).18 Someone, perhaps the patron, perhaps one of her children, has planted a wet finger on the diaper background, just next to the head of Jesus. The figure of Jesus, in turn, points at the spot, as if his finger and the user’s finger had briefly made contact. Ostensibly, the book was at the center of this world, but actually, it was people, not books, that the child wanted to please and whom she imitated. These were lessons she carried into adulthood.

Fig. 100 Female donor kneeling before the Virgin and Child, in a Book of Hours made in 1411 possibly for Jeanne de La Tour-Landry. Lyon, BM, Ms. 574, fol. 55v

II. Teaching morals

Ci nous dist

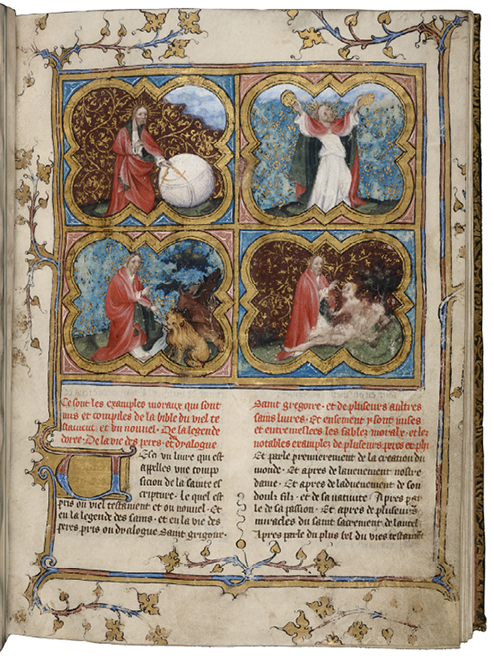

A didactic text first compiled in France around 1320, Ci nous dist contains all the religious knowledge that a child would need to know. As its first rubric announces, it calls itself a book of “moral examples” taken from the Bible, the Golden Legend, the Church Fathers, the Dialogues of St Gregory, as well as Virgil, Plato, Seneca, and Socrates. Copies were written in the vernacular and were often illustrated, although the illustration program was never standardized; one now in Chantilly, made around 1340, contains the most miniatures (812 of them) distributed across its 781 chapters.19 Christian Heck argues that illustrated text served as a “moralized encyclopedia for the laity.”20 In fact, the audience for the book may have been a subset of the laity: each short lesson begins with the words Ci nous dist, “It is said to us,” or “We are told that,” which is the rhetoric of teaching children. The book was popular at court, and it may have been used for instructing courtly children.

The text is organized into six major sections: 1. An overview of salvation history; 2. Moral lessons, written as stories and fables; 3. A guide to humility and confession; 4. Instructions on how to attend Mass; 5. Examples from saints’ lives; 6. How to understand the Final Judgment. The content and aim of the Ci nous dist is therefore similar to that of the Tafel vanden kersten ghelove (Table of Christian Belief) discussed below, as both are didactic texts that imply guidance by a teacher through a graduated catechism. The copy in Chantilly includes visual subjects that seem calculated to appeal to children—stories with characters that are wild, domestic, or mythical animals, and miracles performed by Jesus as a child.21

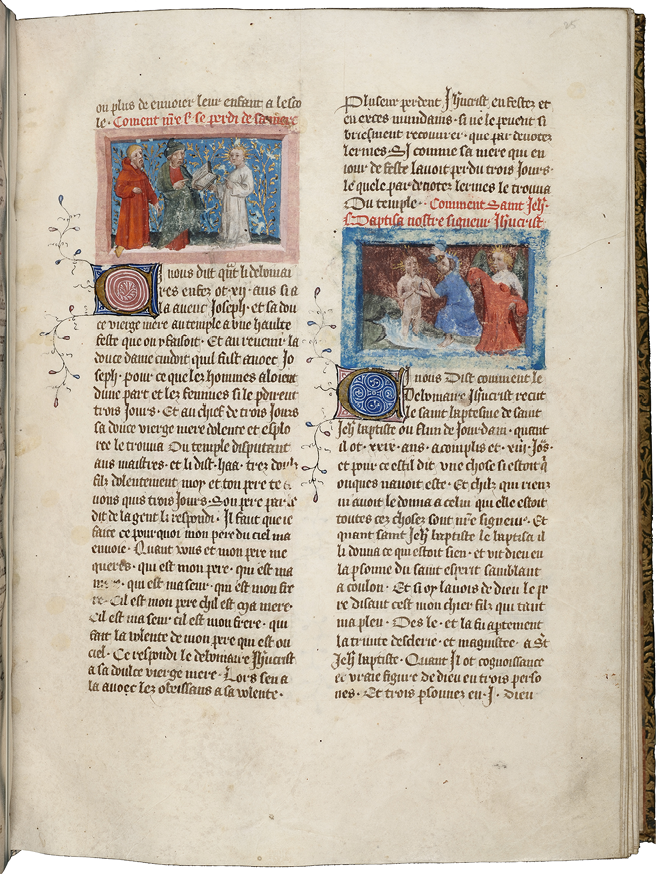

A copy of the Ci nous dist, written and illuminated shortly before 1400 in Ghent or Bruges (BKB, Ms. II 7831) has a column-wide illumination at each section, after a page-wide frontispiece (Fig. 101).22 Many of the images in the manuscript, including those in the frontispiece, have been touched, as if a teacher had pointed out their features to a student and moralized them along the way. Analyzing which parts of the images are rubbed and how they have been rubbed provides some clues about the setting for learning.

Fig. 101 Full-page miniature with four scenes from the creation of the world. Frontispiece in a Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 17r

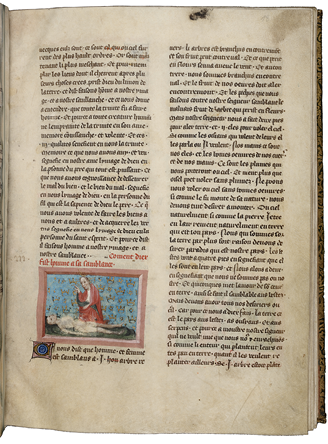

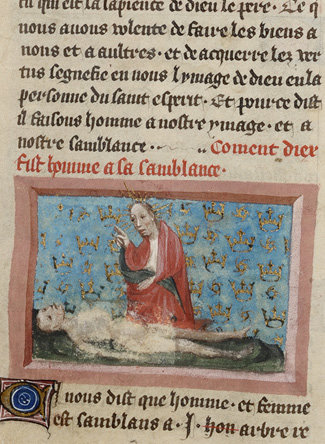

In the opening section of the book, images of the naked bodies of Adam and Eve were particular targets of attention. Most have been rubbed until the anatomical details became illegible. This occurred in the frontispiece, as well as at a lesson about God creating Adam, accompanying a miniature (Fig. 102). The entire midriff of the comatose Adam has been rubbed down to the parchment, either because the teacher was pointing at the creation vigorously, or because he was obscuring the naked man’s genitals and taking a wide aim. That teacher continued the lesson in corporeal squeamishness at the Creation of Eve (Fig. 103). Here, the teacher has obscured the skin-on-skin contact but carefully left Eve, wearing a large smudge, facing her creator. The moral lessons that can be deduced from this gesture mirror that of the story itself: like Eve, a child/learner only becomes aware of his or her shame through loss of innocence. It is as if the process of learning to read and becoming inculcated in Christianity were akin to learning shame. Adam and Eve demonstrate that lesson, while the teacher provides extra moral didacticism by making sure that the child/learner understands that displaying one’s genitals is a cause for shame. The teacher instructed the child to feel this shame by obscuring the genitals in the manuscript.

Fig. 102 Folio with a column-wide miniature depicting God creating Adam. Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 18r, and detail

Fig. 103 Folio with a column-wide miniature depicting God creating Eve. Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 18v, and detail

At the banishment of the couple from Paradise, one detects the presence of an abrading wet finger as the instrument that sanitized the image (Fig. 104). If Adam and Eve were suddenly aware of their nakedness, that awareness was double for the learner, since partially destroying the image drew more attention to it. God may have created Adam and Eve in the previous frames, but teachers destroyed their sex in this one. Living in the post-lapsarian world, the teacher made the student feel that world by touching it and shifting its paint around. These lessons were continuous with moralizing and constituted an interpretative act. Enacting these morals, externalizing them, not only made them more palpable, but it also left traces on the page for future students. In this way, the cultural techniques bridged teacher and student, and also bridged generations, imposing a conservatism in religious thought.

Fig. 104 Folio with a column-wide miniature depicting Adam and Eve being driven from Paradise. Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 19r, and detail

These lessons take another turn later in the manuscript in the story of a certain St Guillaume (Fig. 105). Here the readers (a teacher and student?) have rubbed the body of the devil, especially his hairy torso. The abrasion has also affected the blue background, but mostly the body itself, where someone might have even used a sharp instrument or a fingernail to chip off the paint. In the image the devil kneels before a priest carrying the host, while a man rings a hand bell to signal the presence of the body of Christ. Other images in the book have survived either in pristine condition, without any loss of the flaky blue paint that is eager to throw itself off the page, or with other patterns of handling, such as touching the frame or the nearby initial. This suggests that the book was used episodically, and that the teacher/student dipped into it for particular lessons, rather than reading it from cover to cover. It shows that different stories and their images demanded different responses because they had different moral messages that the teacher wanted to draw out.

Fig. 105 Folio with a column-wide miniature depicting the devil kneeling before a priest carrying the host. Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 49r, and detail

The teacher modeled different ways of touching the images. For example, at the image of the Three Magi, the teacher has concentrated on the frame around the image, as well as the initial C[i nous dist] (Fig. 106). It appears that he or she has wet-touched these areas, and one can imagine a scenario in which the teacher used the image in order to reproduce the drama of the Three Magi offering their gifts to the Christ Child, one in which wet-touching the frame was tantamount to offering a gift. The gift on offer is a kiss. A similar wet response has taken place at the image of the Baptism (Fig. 107). A user has again touched the blue frame and smeared it beyond its original boundaries. The bottom of the frame has been particularly targeted. Did the blue frame “stand for” the river, so that by touching it, the user dipped into the Jordan?

Fig. 106 Folio with a column-wide miniature depicting the Three Magi. Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 23r, and detail

Fig. 107 Folio with column-wide miniatures depicting Christ in the temple as a twelve-year-old, and the Baptism of Christ. Ci nous dist. Ghent or Bruges, 1390s. BKB, Ms. II 7831, fol. 25r

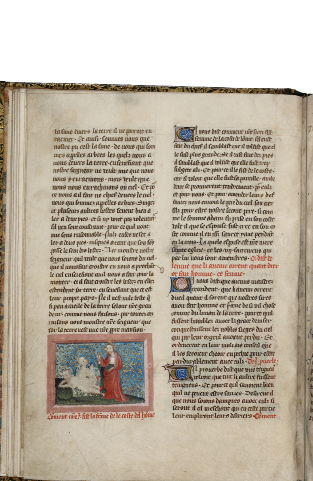

It is worth noting that this folio (25r) also presents an image-cum-story about Mary and Joseph finding their twelve-year-old son in the temple after looking for him for three days. The accompanying image depicts Jesus as a boy instructing the scholars of the temple, as they are all gathered around, and pointing at, an open book. In other words, this image models the kind of arrangement that operated around this very volume, with a teacher (played by Jesus) pointing at items in a book to an audience of learners (played by the scholars of the temple). Of course, this image is interesting because the child becomes the teacher, and the scholars become the learners, in a fundamental reversal. The image itself has been heavily touched, with particular damage to the scholar holding the book, and to the background behind Jesus. The frequent handling and evident wear on this image suggest its profound significance to and resonance with past readers, underscoring the dynamic power of visual storytelling and tactile reading in moralizing texts.

Table of Christian belief

These childhood lessons became codified in moralizing adult entertainment. Children did not outgrow the hierarchical structures of learning when they came of age; rather, the teachers changed. Confessors instructed adults, even powerful ones. A scene depicting adults as students appears in a copy of Jean Golein’s French translation of the Liber de informatione principum, made, according to the colophon, in Paris in 1453 for Giovanni Arnolfini (d. 1470) (HKB, Ms. 76 E 20).23 Arnolfini, a socially-climbing merchant from Lucca who traded in Bruges, emulated court style so closely that he even commissioned Jan van Eyck to paint the famous marital portrait (but that is a different story). The miniature in his manuscript about statecraft shows St Thomas Aquinas teaching an emperor, a king, a chancellor, and three noblemen (HKB, Ms. 76 E 20, Fig. 108). Public figures, such as members of the nobility, would willingly submit to religious instruction to conform to social expectations and to provide an example to their subjects, as well as a testament to their moral rectitude to be broadcast to their associates.

Fig. 108 Frontispiece in Liber de informatione principum, with a miniature depicting St Thomas Aquinas teaching an emperor, a king, a chancellor, and three noblemen. Paris, 1453. HKB, Ms. 76 E 20, fol. 6r

In addition to imitating the behavior of social superiors, nobles sought instruction from private confessors, who may have directed how their charges prayed. Dirc van Delf (ca. 1365–1404), the court chaplain and confessor to Duke Albert (Albrecht) of Bavaria from 1389 until the duke’s death in 1404, not only instructed the duke and coordinated his spiritual reading, but even wrote a textbook for him. Duke Albert and his second wife, Margaret of Cleves (d. 1411), resided in The Hague, where they held court in the decade flanking the year 1400.24 Under Albert and Margaret, the arts flourished, especially rhyming Dutch literature produced in exquisite illuminated volumes. Although the court was in The Hague, the artists working in the court style were based in Utrecht. Even though the court sat in The Hague, the seat of the bishop, most of the convents, and a good deal of the cultural life was based in Utrecht. As will be discussed below in Chapter 4, the courtly audience had a taste for vernacular literature, especially rhyming literature, and members of the court in The Hague would have gathered to hear recitals of the newest texts being produced in Utrecht.25

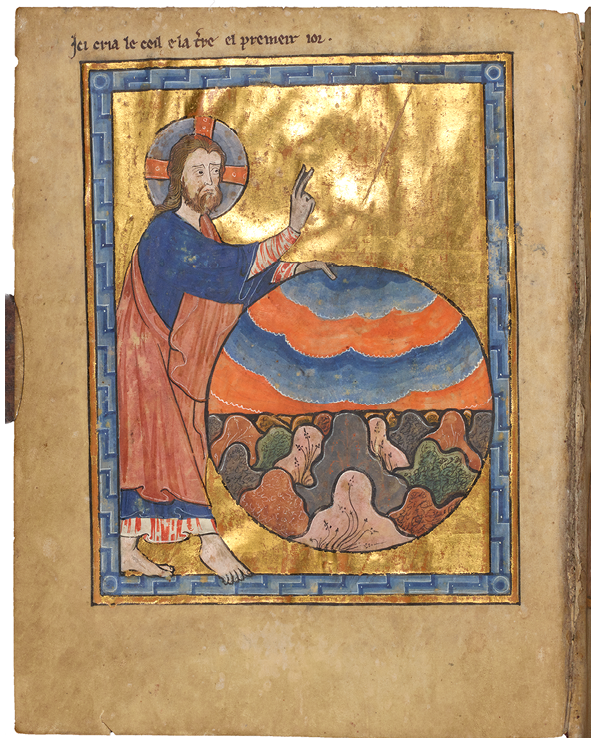

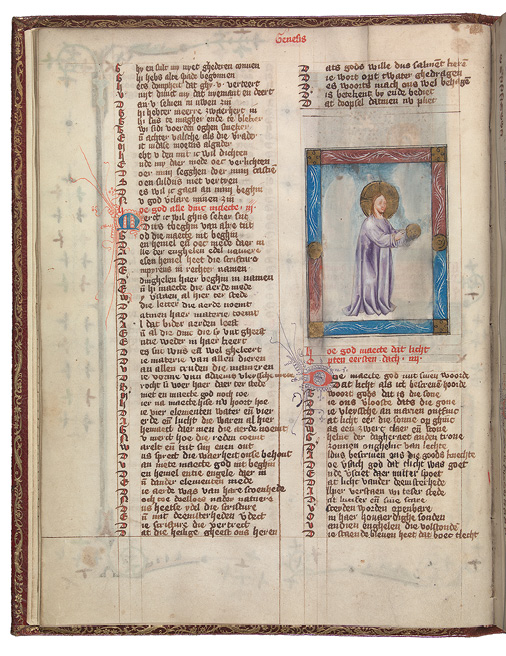

Around 1400 Utrecht bookmakers produced an illuminated copy of a Rijmbijbel by Jacob van Maerlant, a poet born in the 1230s in Bruges. Jacob van Maerlant had spent the early part of his career translating romances into Middle Dutch, and his Rijmbijbel, a rhyming Bible in Middle Dutch, is a selective translation of the Historia scholastica by Petrus Comestor. To this, the poet added another rhyming text called Die Destructie van Jerusalem (The Destruction of Jerusalem), which is his verse translation of a text by Josephus. The two texts, which fill a large and ornate volume, begin with the creation of the universe in seven days, accompanied by a column-wide miniature depicting God creating a glowing orb of light (HKB, Ms. KA 18, fol. 12v; Fig. 109). With folios measuring 315 × 240 mm, and a text block of 250 × 184 mm, the manuscript was sized for public performance, and it would have been large enough for six to eight people to view simultaneously.

Fig. 109 Folio in Jacob van Maerlant’s Rijmbijbel, with a column-wide miniature depicting God creating light from darkness. Utrecht, ca. 1400. HKB, Ms. KA 18, fol. 12v.

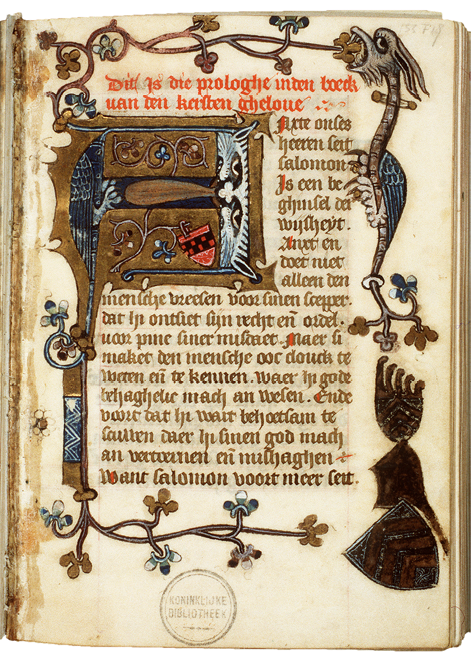

Courts provided nodes between which new ideas easily passed, and they often developed new devotions, systems, and tastes, which others in the periphery then followed. Albert’s court produced several copies of the Sachsenspiegel which, like the duke himself, had come from Germany. He multiplied this text because he was eager to roll out the new legal code in his Dutch-speaking territories, and the contents of that code could best be disseminated by book (see Vol. 1, Chapter 5).26 The court in The Hague also produced didactic literature, namely a religious compendium called the Tafel vanden kersten ghelove (Table of Christian Belief).27 Its author, Dirc van Delf, was a Dominican based at the priory in Utrecht, and his book was a scholastic theology for laymen. Attachés such as Dirc van Delf mediated between the court and the non-court urban milieu. As Frits van Oostrom has argued, the primary audience for this text was the duke himself. From its courtly origins, the text flowed to other audiences.28

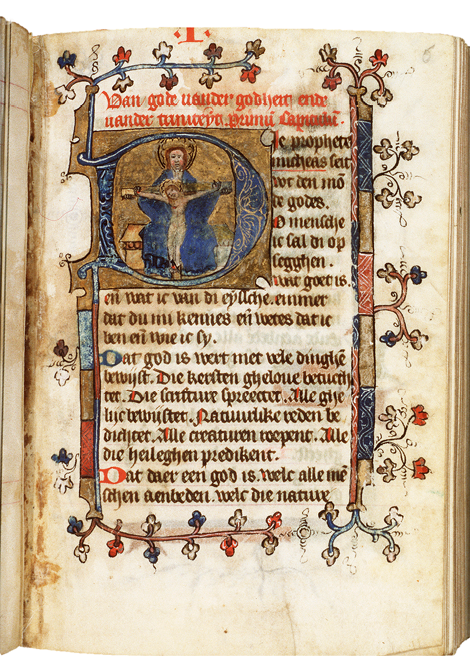

A surviving two-volume copy of the Tafel was produced for the duke in 1400–04. Volume I, which contains the Prologue, bears the duke’s coat of arms on the first recto (HKB, Ms. 133 F 18, fol. 1r; Fig. 110).29 That is followed by 39 chapters on topics such as the roles of students, teachers, bishops, clergy, and leaders; expositions of difficult concepts such as the Trinity, the sacraments, the Ten Commandments, the Works of Mercy, the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit, the Seven Deadly Sins, and the meaning of confession. This manual packages its author’s encyclopedic knowledge of the Christian faith into a palatable form for the laity. It is divided into neat, short sections that may have formed the lessons that the confessor conducted privately with his charge.

Fig. 110 Tafel van den kersten ghelove, incipit of the prologue. Utrecht or Delft, ca. 1400–04. HKB, Ms. 133 F 18, fol. 1r

It is conceivable that Dirc van Delf would have used this very copy during the lessons that the confessor prepared for the duke. Dirc would have taught his charge how to read the book and understand its teachings. Thus, it may have been Dirc who instructed the duke to touch the image of the Trinity at the beginning of the manuscript to initiate his lessons (Fig. 111). The historiated initial is severely abraded from repeated contact. There are no other figurative images in the manuscript, which is part of the reason that the rest of the manuscript has not been touched in this way, but rather bears the marks of regular wear. Albert’s confessor may have encouraged the duke to make physical contact with the image of the Trinity on the page, as a ritualized preamble to learning his catechism. Ultimately, it relates to the priest touching or kissing the body of Christ before performing the Canon of the Mass.

Fig. 111 Tafel van den kersten ghelove, incipit of the main text (summer part). Utrecht or Delft, ca. 1400–04. HKB, Ms. 133 F 18, fol. 6r

In fact, another image from this courtly milieu also appears to have been touched: that showing God creating light in the Rijmbijbel (see Fig. 112). Someone has repeatedly touched the orb that God holds and did so in imitation of God’s gesture. In this miniature, fingers have probed the black ink outline around the gold orb, thereby spreading smudges into the clean white area. One can imagine the performer touching the golden disc by way of dramatizing his reading, as if switching on a light in the darkness. Such gestures would have been directed toward the audience attending the recitation.

Fig. 112 Miniature in Jacob van Maerlant’s Rijmbijbel, depicting God creating light from darkness. God doesn’t play dice, but he does bowl. Utrecht, ca. 1400. HKB, Ms. KA 18, fol. 12v (detail of Fig. 105).

Book of the Antichrist

One could also teach morals through fear, which is the central idea behind the Book of the Antichrist. This story, in circulation since the fifth century, formed part of an eschatological and apocalyptic tradition that resurged around the year 1000, and then again in the later Middle Ages. Although the illustrated text is better known in its blockbook form called the Puch von dem Entkrist, the blockbook was based on an earlier manuscript tradition in Germany.30 This section considers a particular manuscript copy of the text, now preserved in Berlin (Berlin, SB, Ms. germ. fol. 733).31 This image-centered book—or Bilderbuch—could have had multiple audiences, including a small teaching group. Signs of wear suggest that this volume was used in a didactic context, where the images amplified the terse messages, and a teacher or interlocutor extended the message in theatrical retellings.

The manuscript is large enough to be seen by approximately eight people simultaneously. The signs of wear in the manuscript are numerous and have multiple origins. They tell a story of the book being handled extensively and also held up for demonstration purposes. Unlike the Parisian Book of Hours (HKB, Ms. 76 F 21), discussed earlier, this book lacks the features one would associate with an easy reader for children: rather than presenting large, unabbreviated script, and easy-to-read texts, it has tiny, loopy script rife with ligatures and abbreviations. However, like MJRUL French 5 and the Parisian Book of Hours, it does have enormous colorful images that augment the message. The book is not for teaching someone to read, but rather instructing them about what to think. In that way, it is less like MJRUL French 5 and the Parisian Book of Hours, and more like the Ci nous dist and the Table of Christian Belief.

Berlin, SB, Ms. germ. fol. 733 was copied around 1440. It comprises three distinct but related texts: The Book of the Antichrist (Vom Antichrist, fols 1r–10v); The Fifteen Signs before the Last Judgement (Die Fünfzehn Zeichen vor dem jüngsten Gericht, fols 11r–12v); and The Last Judgement (Vom jüngsten Gericht, fols 13r–13v). The respective beginning folios of the Book of the Antichrist and The Fifteen Signs are missing, and the first and last surviving folios are abraded, which suggests that this manuscript was out of its binding for some time before receiving its current boards in the nineteenth century. Only 13 folios survive from what may have originally comprised 16 folios. An overview of the complete book shows how worn it is, especially at the beginning and end (Fig. 113).

Fig. 113 Screen shot showing a tile view of all the folios in Vom Antichrist (https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN726683248&PHYSID=PHYS_0009&DMDID=DMDLOG_0001). Germany, ca. 1440. Berlin, SB, Ms. germ. fol. 733

The story of Antichrist is styled as a saint’s vita, where Antichrist appears as a nimbed figure. The difference between his representation and that of a saint is the presence of a wiry black devil that hovers above his hands or head in nearly every scene. Besides that, his story follows the lines of a saintly vita, beginning with his diabolical birth and continuing through his adulthood.32 When he appears during the Apocalypse, Antichrist’s goal is to deceive and confuse people. To do this, he masquerades as Jesus, pronouncing the words from Matthew 24:5, “Ego sum Christus,” the ultimate blasphemy.

The legends of the Antichrist, told as vignettes, dwell on his miracles. Antichrist performs miracles that are either pointless or that invert Christ’s. Instead of turning water into wine, he makes water run uphill (1r). The point of his miracles is showmanship and entertainment, not humanitarian relief. Antichrist hatches a giant from an egg, he suspends a castle by a thread from the sky, and he calls forth a stag from a rock. These three miracles, which lack any narrative precedents, appear in one vignette (Fig. 114). Tina Boyer explains them as reversals of nature.33 A castle, for example, usually stands for safety and impenetrability, but when it dangles above the earth from a weak fiber, it provides no more security than a tree house in a willow bush.

Fig. 114 Folio depicting multiple events in Vom Antichrist. Germany, ca. 1440. Berlin, SB, Ms. germ. fol. 733, fol. 1v

Although the book has been damaged inadvertently due to poor storage, especially on its first and last folios, it has also received targeted wear on several of the miniatures, offering some clues about how the reader might have presented the stories to the audience. Each folio in The Book of the Antichrist is divided horizontally into two registers containing a framed narrative image and a short descriptive text in German. The text blocks have not been ruled, and consequently the text meanders. Clearly the book has been conceptualized foremost as a picture book, and the texts inscribed as an afterthought. One can imagine a charismatic person in the mid-fifteenth century, someone keenly guarding the morals of young people, who tells stories of a clever devil and recounts the signs of the end of the world, pointing at the images in the book and enthralling his audience. The somewhat simple drawings, with their bright washes, do not so much represent these events as present a springboard from which the raconteur can launch his performance to ignite the audience members’ imagination.

Audience is crucial to the stories. As Boyer points out about the motivations of Antichrist: “His goal is to blind and seduce [audience members] so that they believe his lies and deceit.”34 The images in Berlin 733 show Antichrist performing these miracles before audiences, and it is possible that these depicted audiences reflect the intended audience for the book itself: not a solitary reader, but a group of listeners who reinforce each other’s reception of the text, where each gasp and tut ripples through the group.

The Book of the Antichrist accompanies the Fifteen Signs before the Last Judgement, both in its manuscript and its blockbook traditions. The signs are as follows, in abbreviated form: 1) the sea rises above the mountains; 2) the sea recedes, and the earth withers; 3) the fish in the sea lament to heaven; 4) the sea and all the waters burn up; 5) trees sweat blood; birds assemble on the fields and refuse food; 6) buildings collapse and trees fall down; 7) stones fly up and smash each other; people hide in caves; 8) earthquakes; 9) all mountains are leveled; 10) people return from the mountains and go about as if they are senseless and unwilling to speak to each other; 11) the dead rise; 12) the stars fall from heaven and emit fire; 13) the living die so that they can rise with the dead; 14) heaven and earth are consumed by fire, 15) but will be renewed, and all humankind shall rise together.35 Some of the startling series of preternatural events form an antithesis to the Biblical stories. Instead of God separating the land from the waters, here the waters engulf the land. Instead of creatures multiplying, here they starve and wither. The final events concern humanity, which will die to be reborn and undergo a collective apotheosis.

One can see how the Fifteen Signs could have riveted an audience. This text comprises a list, sometimes illustrated, which is often incorporated into other texts, which frame and contextualize it. For example, in the Berlin manuscript, it depends on the apocalyptic context of the Book of the Antichrist. Christoph Gerhardt and Nigel F. Palmer identified the text in 68 German and Middle Dutch manuscripts.36 Many of them can be categorized as didactic manuscripts, such as Buch von geistlicher Lehre and Dirc van Delf’s Tafel van den kersten ghelove, discussed above.

Each folio presents three signs. Because the first folio of the text is missing, the series begins with the fourth sign (Fig. 115). Immediately apparent is the degree to which this section of the book has been handled. The edge is darkened with fingerprints from hands turning the folios. Because the book is large (measuring 290 × 210 mm) and the parchment heavy, the leaves lie open now and may have also done so when the book was new around 1440. It was not held in the hand, like an octavo-sized book, but rather it lay flat on a table. Besides the fingerprinting at the edges, suggesting just how often the pages were turned, the surface also has some stains from dripped liquid, possibly candle wax. One can imagine a group of about six people gathered around a small table where the manuscript lay open, its graphic images illuminated by candlelight: wax has dripped onto folio 6v.

Fig. 115 Folio depicting three of the Fifteen Signs before the Last Judgement, in Vom Antichrist. Germany, ca. 1440. Berlin, SB, Ms. germ. fol. 733, fol. 11r

Various authors have considered the audience for blockbooks in general, and the Book of the Antichrist in particular. Even if that audience can be identified, the blockbook audience may have differed from the manuscript audience. As the text was written entirely in German, it could have had a wider reach than comparable picture books with text, such as the Biblia Pauperum, which were written in Latin. As Boyer argues, the Antichrist and the Fifteen Signs were used in an educational environment, in a monastic or urban setting.37 One can easily imagine this manuscript at the center of a gripping lesson with a charismatic teacher guiding pairs of wide eyes through the apocalyptic parchment-scape.

Coda

Manuscripts treated in this chapter have images and texts that suggest they were used in teaching settings, where a teacher plus one or more students would gather around the book, and the teacher would draw the students’ attention to the items on the page through gesture. All of the books discussed above have been touched in vigorous and specific ways that have left traces, allowing us to reverse-engineer these actions.

I have dwelt upon the social actions around teaching and learning because they would have been highly influential in creating norms of book-handling. The children who used the books discussed above would have been members of courts or of wealthy, book-owning families. Such families and courts were trendsetters and tastemakers, both in terms of manuscript content and style.38 The direct way in which teachers normalized book-touching behavior among their charges was an influential vertical method of transmission, which would have shaped how those children handled other manuscripts when they came of age and acquired more books.

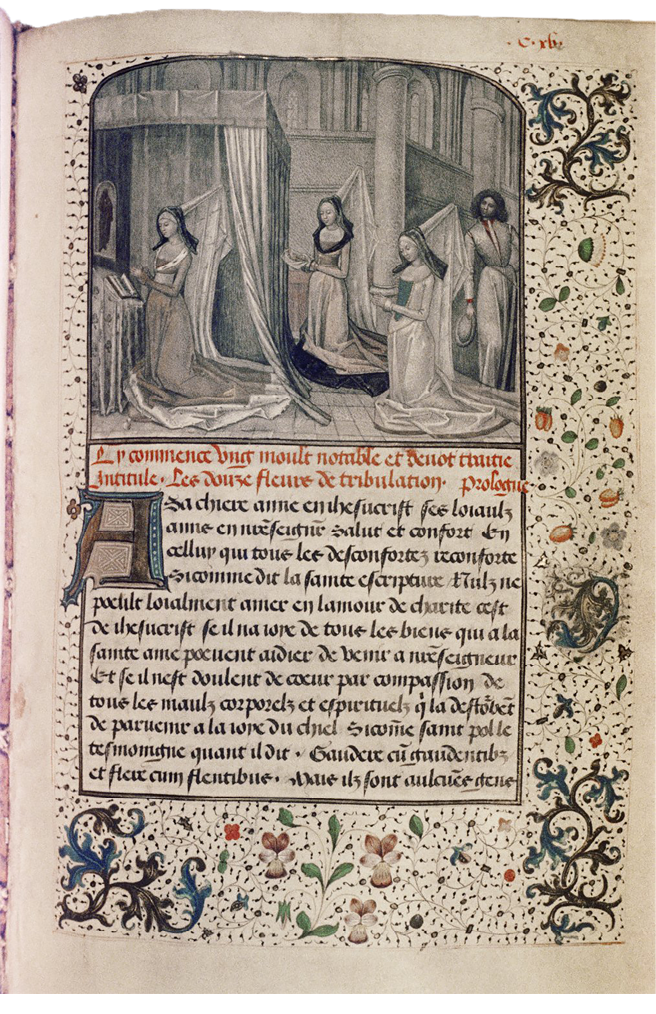

Likewise, European courts were places where horizontal and vertical lines of transmission encouraged the spread of objects, tastes, and ideas. Those who witnessed Duke Albert touching his books may have copied his behavior. It is clear that nobles at various courts around Europe made dramatic displays of their piety and that doing so may have been a pre-condition for social acceptance in courts headed by leaders who vehemently displayed their piety. One need only turn to a depiction of Margaret of York in prayer, with her ladies-in-waiting behind her, to see how devotional performance would have been transmitted to the immediate audience of one’s underlings (Oxford BL, Ms. Douce 365, fol. 115r; Fig. 116). Social performances with manuscripts at court will be taken up in the next chapter.

Fig. 116 Margaret of York in prayer before an image, with her ladies-in-waiting behind her. Ghent, 1475. OBL, Ms Douce 365, fol. 115r

1 J. J. G. (Jonathan James Graham) Alexander, “Facsimiles, Copies, and Variations: The Relationship to the Model in Medieval and Renaissance European Illuminated Manuscripts,” Studies in the History of Art, 20 (1989), pp. 61–72; idem, Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work (Yale University Press, 1992); Ilya Dines, “The Copying and Imitation of Images in Medieval Bestiaries,” Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 167(1) (September 1, 2014), pp. 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1179/0068128814Z.00000000026; Vibeke Olson, “The Significance of Sameness: An Overview of Standardization and Imitation in Medieval Art,” Visual Resources, 20(2–3) (March 1, 2004), pp. 161–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/0197376042000207543

2 Irene O’Daly, Irene van Renswoude, and Mariken Teeuwen conducted a project at the Huygens Institute in Amsterdam from 2016–2020, which resulted in a thoughtful website, “The Art of Reasoning in Medieval Manuscripts,” a valuable resource on medieval didactic manuscripts, with examples and many further references: https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/about.html. See also the essays in Mariken Teeuwen and Irene van Renswoude (eds), The Annotated Book in the Early Middle Ages: Practices of Reading and Writing, Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy, 38 (Brepols, 2018).

3 Leiden, University Library, BPL 76A https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/1611724

4 Kathryn M. Rudy, “An Illustrated Mid-Fifteenth-Century Primer for a Flemish Girl: British Library, Harley Ms 3828,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 69 (2006), pp. 51–94.

5 The date is inscribed within the book that the crowned figure holds above his head. For this painting in its Transylvanian context, see Harald Krasser,

“Zur siebenbürgischen Nachfolge des Schottenmeisters. Die Birthälmer Altartafeln,” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst und Denkmalpflege, Vol. 27 (1973), pp. 109–121.6 I first presented the ideas in this section at a lecture I gave at the John Rylands Library in Manchester on 20 October 2016. This was followed by a manuscript handling session I led with MJRUL, Ms. French 5, in which I hypothesized its function as a didactic aid for teaching children in light of its traces of use. As I go to press, a new article about this manuscript has appeared; it proffers ideas close to those I presented in 2016, although the author was apparently unaware of my lecture: Molly Lewis, “Sinful, Sexual, Sacred: Locating a Thirteenth-Century Visuality through the Selective Erasures in Rylands MS French 5,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 99.2 (2023): 1–24. < https://doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.99.2.1> (published on the Web 14 Jan. 2024). Previously, two studies concentrated on this manuscript: Caroline S. Hull, “Rylands Ms French 5: The Form and Function of a Medieval Bible Picture Book,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 77(2) (1995), pp. 3–24; Robert Fawtier, La Bible Historiée toute Figurée de la John Rylands Library (Pour les Trustees et gouverneurs de la John Rylands library, 1924).

7 As was typical with twentieth-century scholarship, Fawtier 1924 is concerned with questions of style and production, but not of use or reception; however, following M. Delisle, he does ask whether the booklet of images once formed part of a Psalter or a Bible (pp. 33ff).

8 Martin Kauffmann, “Seeing and Reading the Matthew Paris Saints’ Lives,” in Illuminating the Middle Ages: Tributes to Prof. John Lowden from His Students, Friends and Colleagues, Laura Cleaver, Alixe Bovey and Lucy Donkin (eds) (Brill, 2019), analyzes a related case, with inscriptions on image cycles that resemble “school exercises.”

9 On identifying children’s drawings in medieval manuscripts, see Deborah Ellen Thorpe, “Young Hands, Old Books: Drawings by Children in a Fourteenth-Century Manuscript, LJS MS. 361,” Peter Stanley Fosl (ed.), Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1) (December 31, 2016), 1196864. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.1196864

10 Fawtier, La Bible Historiée, pp. 3–6, transcribes the tituli in the context of his thorough description of the manuscript.

11 For images, see http://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/consult/consult.php?reproductionId=10679. For an updated bibliography, see https://portail.biblissima.fr/en/ark:/43093/mdata24fa2b3214b6ef030e91bcef23cb1eb05eea3244

12 Kathryn M. Rudy, “The Bolton/Blackburn Hours (York Minster Add. Ms. 2): A New Solution to its Text-Image Disjunctions using a Structural Model,” Tributes to Paul Binski. Medieval Gothic: Art, Architecture & Ideas, ed. Julian Luxford (Brepols, 2021), pp 272-285. On fol. 35r, reproduced here, the teacher was wrong: the image does not represent “the meeting and mourning of the Maries,” but rather shows St Anne teaching Mary and two other nimbed girls to read.

13 Anne S. Korteweg et al., Splendour, Gravity & Emotion: French Medieval Manuscripts in Dutch Collections (Waanders, 2004), p. 175.

14 For children’s manuscripts, see Roger S. Wieck, “Special Children’s Books of Hours in the Walters Art Museum,” in Als Ich Can: Liber Amicorum in Memory of Professor Dr. Maurits Smeyers, Bert Cardon et al. (eds) (Corpus of Illuminated Manuscripts = Corpus van Verluchte Handschriften) (Peeters, 2002), pp. 1629–39; and Kathryn A. Smith, “The Neville of Hornby Hours and the Design of Literate Devotion,” The Art Bulletin, 81(1) (1999), pp. 72–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/3051287

15 On St Anne and children’s literacy in the late Middle Ages, see Michael Clanchy, “Did Mothers Teach their Children to Read?,” in Motherhood, Religion, and Society in Medieval Europe, 400–1400: Essays Presented to Henrietta Leyser, Conrad Leyser and Lesley Smith (eds) (Ashgate, 2011), pp. 129–53; Wendy Scase, “St. Anne and the Education of the Virgin,” in England in the Fourteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1991 Harlaxton Symposium, Nicholas Rogers (ed.) (Paul Watkins, 1993), pp. 81–98.

16 Photographing manuscripts with backlighting (transmitted light) has been in the toolbox of book conservators but not of book historians. See, for example, Nancy K. Turner, “Beyond Repair: Reflections on Late Medieval Parchment Scarf-Joined Repairs,” Journal of Paper Conservation, 22(1–4) (October 2, 2021), pp. 131–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/18680860.2021.2007040

17 For a rudimentary description of this manuscript, see http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/codex/2772

18 For a description and a link to the images, see http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/codex/2431

19 Christian Heck, Le Ci nous dit: L’image médiévale et la culture des laïcs au XIVe siècle: les enluminures du manuscrit de Chantilly (Brepols, 2011), treats a richly illuminated copy (Chantilly, Musée Condé, Ms. 26-27 [1078-1079]). Like the copy examined here, now in Brussels, the Chantilly copy has also been heavily touched, as if a teacher were enacting moral lessons with the images.

20 Heck, Le Ci nous dit, p. 15.

21 This is comparable to subjects in the Neville of Hornby Hours, which Kathryn Smith convincingly argues was made for instructing a child. See Kathryn A. Smith, “The Neville of Hornby Hours and the Design of Literate Devotion,” The Art Bulletin, 81(1) (1999), pp. 72–92.

22 Maurits Smeyers, Vlaamse Miniaturen voor van Eyck, ca. 1380-ca. 1420. Catalogus: Cultureel Centrum Romaanse Poort, Leuven, 7 September-7 November 1993, Corpus of Illuminated Manuscripts = Corpus van Verluchte Handschriften (Peeters, 1993), cat. 52.

23 See Anne S. Korteweg et al., Splendour, Gravity & Emotion: French Medieval Manuscripts in Dutch Collections (Waanders, 2004), no. 51, color figs. 94, 95.

24 Although they ordered many books, including the Sachsenspiegel discussed above in Vol. 1, Chapter 5, and must have patronized numerous writers and painters in their midst, the names of these artists have not come down to us, and we refer to them by the name of the patron of the most distinctive examples of their work. One of the miniaturists who made leaps in style is known as the Master of Margaret of Cleves for having made the duchess an exquisite Book of Hours: Lisbon, Museum Calouste Gulbenkian, Ms. LA 148, for which see James H. Marrow, As Horas de Margarida de Cleves = The Hours of Margaret of Cleves (Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, 1995).

25 F. P. van Oostrom, Stemmen op Schrift: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Literatuur vanaf het Begin tot 1300 (Bakker, 2013), pp. 531–547.

26 In addition to the Middle Dutch copy of the Sachsenspiegel (HKB, Ms. 75 G 47) discussed in Vol. 1, Chapter 5, another is now in Cologny-Geneva (Switzerland), cod. Bodmer 61 (https://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/description/fmb/cb-0061/).

27 C. G. N. de Vooys, “Iets over Dirc van Delf en zijn ‘Tafel Vanden Kersten Ghelove,’” Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsche taal- en letterkunde, 22 (1903), pp. 1–67, provides an overview of the text.

28 Frits Pieter van Oostrom, “Dirc van Delft en zijn lezers,” in Het woord aan de lezer: zeven literatuurhistorische verkenningen, W. van den Berg, Hanna Stouten, and P. J. Buijnsters (eds) (Wolters-Noordhoff, 1987), pp. 49–71.

29 Volume II (the winter part) is now in Baltimore, Walters Ar Museum, Ms. W.171. For a description and images, see https://www.thedigitalwalters.org/

30 Literature on blockbooks is vast, part of which deals with the Puch von dem Entkrist. Several facsimile editions have been produced: Das Puch von dem Entkrist: Faksimile des Originals der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, ed. Kurt Pfister (Insel, 1925); and Der Antichrist und die Fünfzehn Zeichen: Faksimile Ausgabe des einzig erhaltenen chiroxylographischen Blockbuches, Vol. 1, Heinrich Theodor Musper (ed.) (Prestel, 1970); Der Antichrist und die Fünfzehn Zeichen vor dem jüngsten Gericht: Faksimile der ersten typographischen Ausgabe. Inkunabe der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main. Inc. Fol. 116, Vol. 1, Karin Boveland, Christoph Peter Burger, and Ruth Steffen (eds) (Buijten & Schipperheijn, 1979). For an overview the literature about the Book of the Antichrist (which centers around the blockbook tradition, although this is also relevant for the earlier manuscript tradition), see: Tina Boyer, “The Miracles of the Antichrist,” in E. Hintz & S. Pincikowski (eds), The End-Times in Medieval German Literature: Sin, Evil, and the Apocalypse (Boydell & Brewer, 2019), pp. 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787445024.012; and Anneliese Schmitt, “Der Bild-Text des ‘Antichrist’ im 15. Jahrhundert. Zum Abhängigkeitsverhältnis der Handschriften, Blockbücher und Drucke und zu einer möglichen antiburgundischen Tendenz,” E codicibus impressisque. Opstellen over het boek in de Lage Landen voor Elly Cockx-Indestege. 3 vols., Frans Hendrickx and Josef M. M. Herrmans (eds) (Peeters, 2004); Miscellanea Neerlandica 18–20, Bd. 1: Bio-bibliografie, handschriften, incunabelen, kalligrafie, pp. 405–430.

31 The manuscript has been digitized: https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN726683248&PHYSID=PHYS_0009&DMDID=DMDLOG_0001

32 For a detailed analysis of all of the images in the Berlin manuscript, cross-referenced with the image cycles in other copies of the story, see Hella Frühmorgen-Voss and Norbert H. Ott, Katalog der deutschsprachigen illustrierten Handschriften des Mittelalters Band 7, 59. Historienbibeln-70. Kräuterbücher (Beck, 2017), pp. 264–274; for an overview of the Berlin manuscript, see pp. 274–276.

33 Tina Boyer, “The Miracles of the Antichrist,” in E. Hintz and S. Pincikowski (eds), The End-Times in Medieval German Literature: Sin, Evil, and the Apocalypse (Boydell & Brewer, 2019), pp. 238–254.

34 Boyer, “The Miracles of the Antichrist,” p. 238.

35 The list comes from Boyer, p. 248, n. 2. See also Manfred von Arnim, “The Chiroxylographic Antichrist and the Fifteen Signs: English Summary,” in Musper, Der Antichrist und die Fünfzehn Zeichen, 2; Petra Simon, Die Fünfzehn Zeichen in der Handschrift Nr. 215 der Gräflich von Schönborn’schen Bibliothek zu Pommersfelden (Ph.D. Diss., 1978), pp. 173–176.

36 Christoph Gerhardt and Nigel F. Palmer, “Die ‘Fünfzehn Zeichen vor dem jüngsten Gericht’ in deutscher und niederländischer Überlieferung,” Katalog (18. Juni 2000). https://handschriftencensus.de/forschungsliteratur/pdf/4224

37 Boyer, “The Miracles of the Antichrist,” p. 239.

38 On this point, see Joyce Coleman, “Reading the Evidence in Text and Image: How History Was Read in Late Medieval France,” in Imagining the Past in France: History in Manuscript Painting, 1250–1500, Elizabeth Morrison and Anne D. Hedeman (eds) (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2010), pp. 53–67, with further bibliography.