Chapter 4: Performing at Court

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.04

Members of royal and ducal courts entertained themselves by holding jousts, hunting, feasting, watching pageants, and reading literature. To satisfy the demand for reading, courtiers commissioned new literature, including historical, religious, and didactic works, splendid, legitimizing histories, and chronicles of recent events. They also sought romances, such as the stories of the Knights of the Round Table, which presented idealized images of the courtier that mirrored their audience in a rose-tinted glass. Courtiers owned the largest libraries in late-medieval Europe and had a penchant for rhyming texts in vernacular languages.1

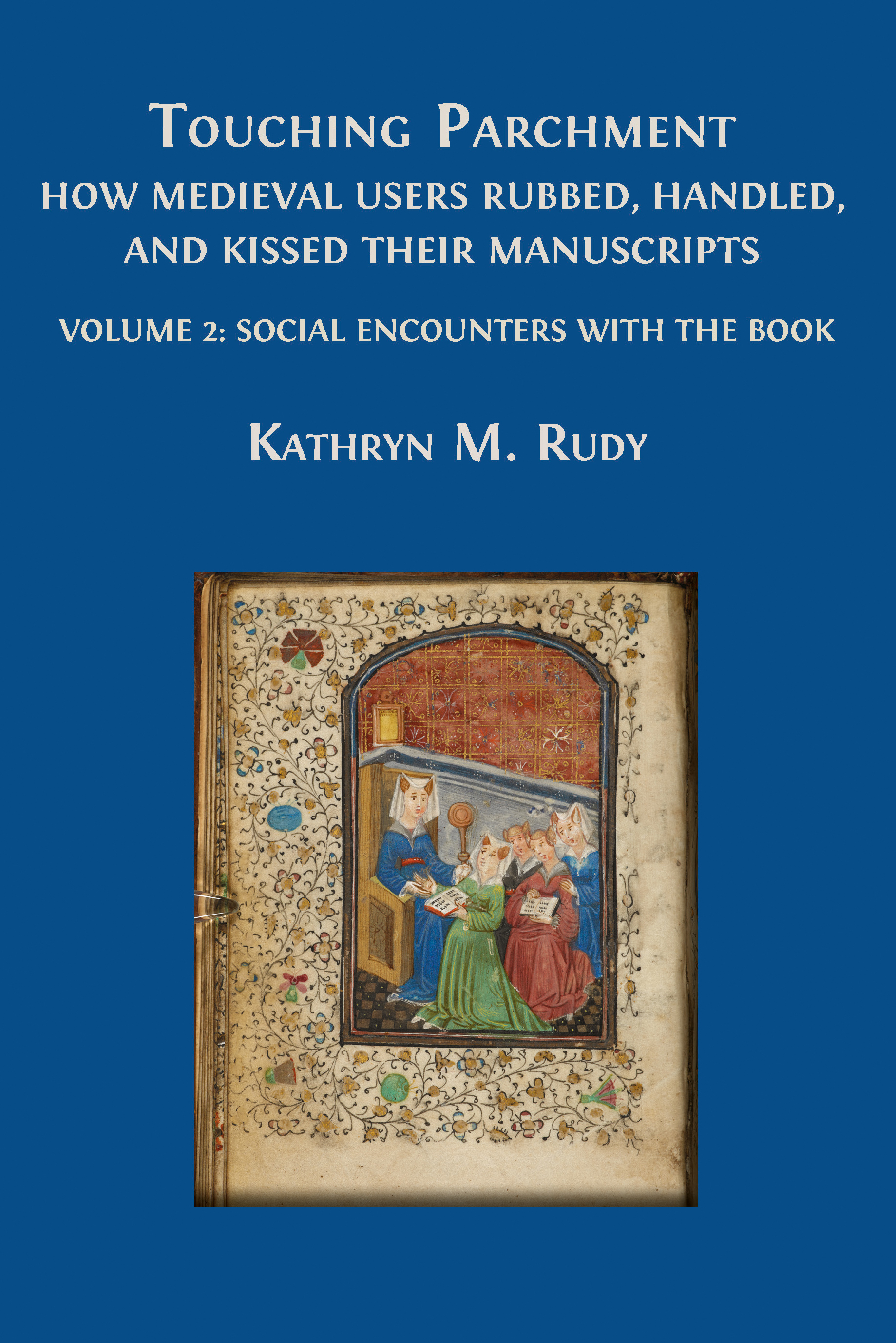

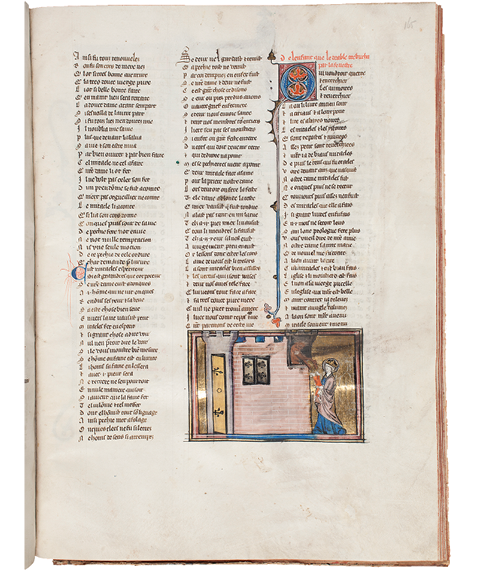

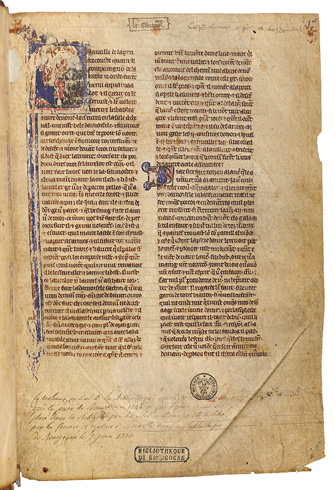

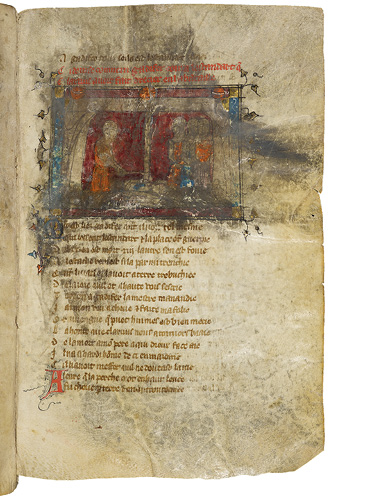

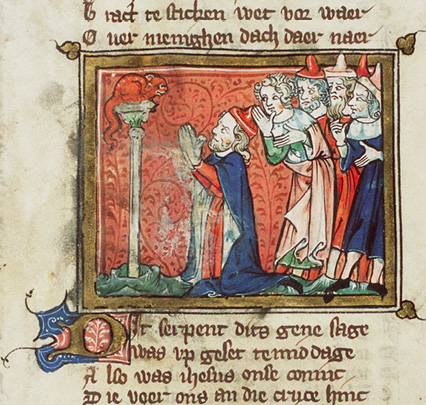

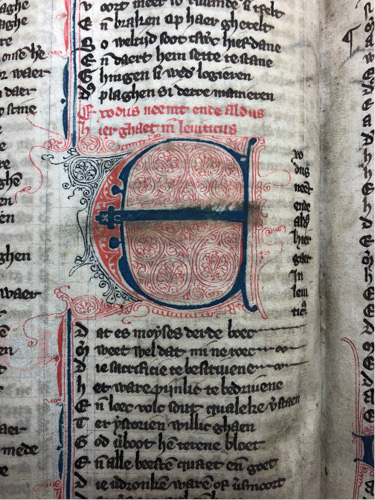

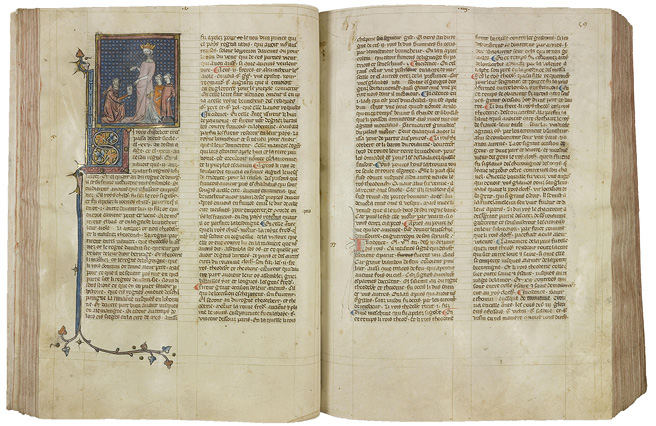

Fig. 117 Folio in Jan van Heelu, De slag bij Woeringen. Brussels, ca. 1440. HKB, Ms. 76 E 23, fol. 9v, and detail of the initial

Writers and translators scurried to meet this demand. For example, knight and writer Jan van Heelu penned the Battle of Woeringen (De slag bij Woeringen) in 1288 after he took part in it. As a witness to this battle between Reinoud I of Guelders and Jan I, Duke of Brabant, he memorialized the event in rhyming verse. Around 1440, a copy was made for the city of Brussels, where it was kept in the town hall for 200 years (HKB, Ms. 76 E 23, fol. 9v; Fig. 117). In other words, it was the kind of book contextualized alongside a city’s privileges, such as the Rood Privilegieboek discussed in Volume 1, where, as we have seen, courtly life spilled into civic life with the joyous entries of Brabantine dukes, and the deeds of the ruling class were memorialized in town halls. Damage to the opening initial—multiple finger-tip-sized areas of paint loss aimed at the center of the letter—point to physical, performative gestures of reading. These cultural techniques around public reading took hold in European courts, and their effects left traces in manuscripts of a variety of genres.

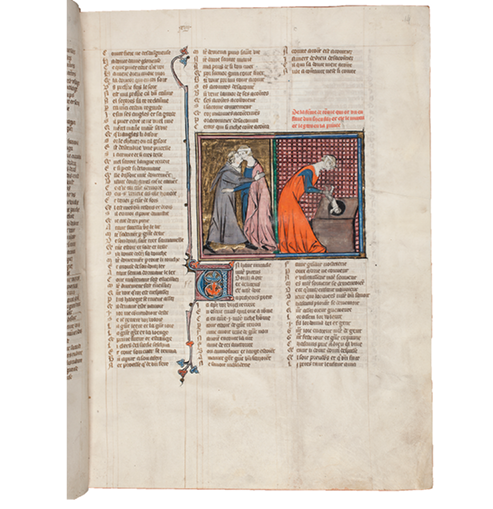

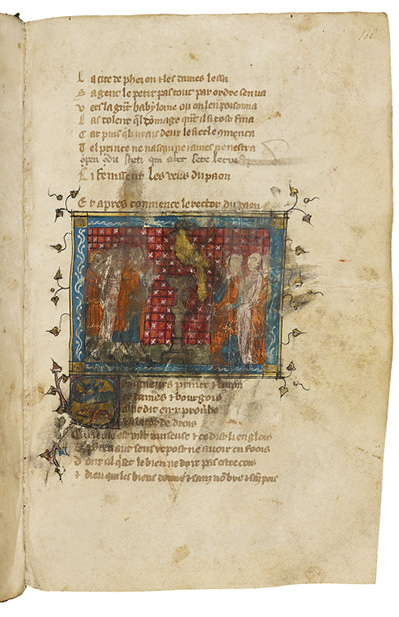

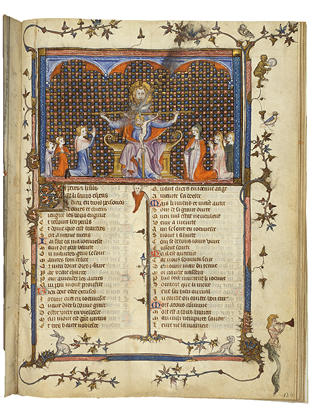

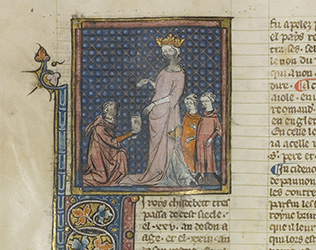

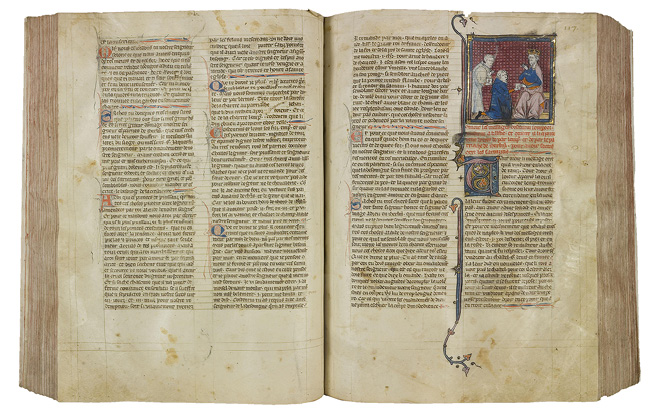

Didactic works patronized by courtiers and socially aspiring merchants included many titles in the “Mirror for Princes” genre, which were how-to volumes about statecraft. One of these, the anonymously authored Liber de informatione principum, was translated into French by Jean Golein. A copy, illuminated in Paris in 1453, was made for Giovanni Arnolfini (d. 1470), the lucchese merchant who lived in Bruges and Rouen (HKB, Ms. 76 E 20).2 The prefatory miniature shows a courtier on bent knee presenting the manuscript to a knight of the Golden Fleece (Fig. 118). The knight acknowledges the gift by looking at it while laying his hand on it. The image attests to the centrality of literature and book-gifting culture among the most powerful men of late-medieval Europe.

Fig. 118 Opening folio of Jean Golein’s translation of Liber de informatione principum, illuminated in Paris by the Master of êtienne Sanderat de Bourgogne in 1453. HKB, Ms. 76 E 20, fol. 1r

The fourteenth century witnessed a push to translate large amounts of literature from Latin into the various European vernaculars, and also to write new literature in those languages. The manuscripts featured in this chapter testify to this trend, which also points to more widespread literacy, and to increased use of manuscripts beyond ecclesiastical or administrative purposes. A related trend was to versify prose texts, including prayers. Doing so both conformed to courtly tastes and made texts more entertaining to read aloud. Versified texts included romances, chronicles, prayers, and retellings of the Bible. Chaucer, Jean de Meun, Dante, and Jacob van Maerlant supplied new versified texts in English, French, Italian, and Dutch, respectively. Versifying and translating texts implies turning them from scholarly, monastic, or study texts into texts performed aloud for an audience.

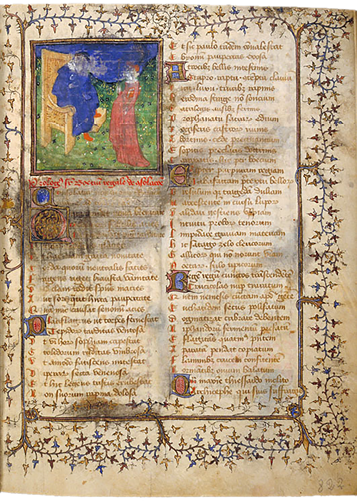

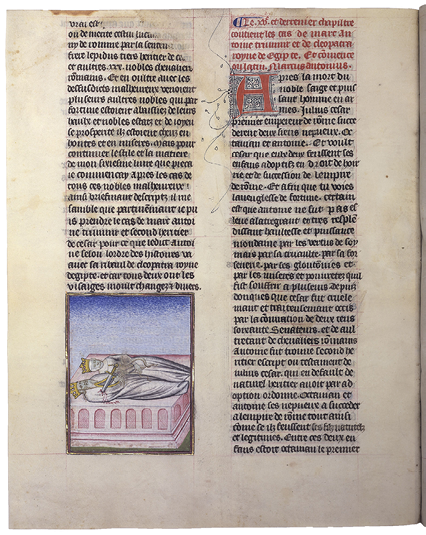

Fig. 119 Opening folio of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. Paris, ca. 1400–1425. BM de Toulouse. Ms. 822, fol. 1r, and detail

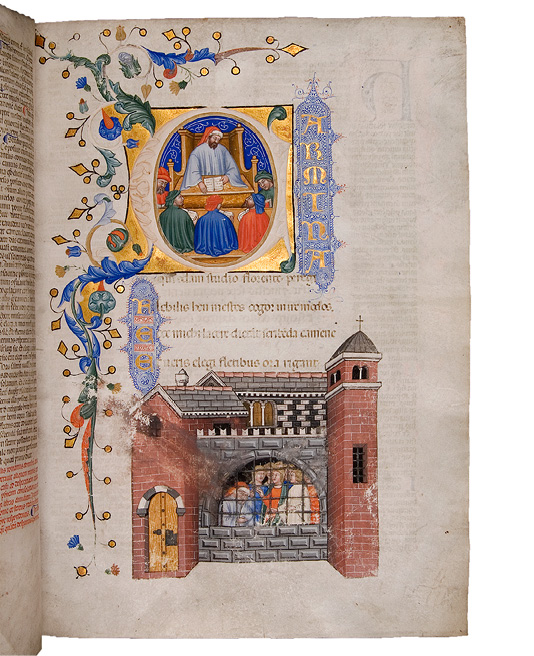

Fig. 120 Opening folio of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. Genoa(?), 1385. Glasgow UL, Hunter Ms. 374, fol. 4r

There was even a versified translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy (BM de Toulouse, Ms. 822, fol. 1r; Fig. 119).3 Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (ca. 480–584) wrote the text in prison before his execution. It opens with Boethius bewailing his miserable state, and Dame Philosophy instructing Boethius on the nature of Fortune. The message proved influential throughout the Middle Ages, when melancholic noblemen and imprisoned knights waiting to be ransomed took comfort from its teachings. More than 400 medieval copies of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy survive. The copy now in Toulouse, which was written and illuminated with courtly magnificence in Paris in the first quarter of the fifteenth century, has column-wide miniatures and initials that have been touched and rubbed repeatedly.

This leads to an important question: how did people read at court? Two camps of literary historians answer that question differently. One, led by Paul Saenger, believes that medieval people read silently and alone.4 His evidence is that after the eleventh or twelfth century, books came to be made with clearer spaces between words, which allowed faster reading. He argues that silent reading was necessary for the development of personal identity, as well as such literary forms as irony. Scholars in the other camp, led by Joyce Coleman, argue that much of the written word was experienced aurally, and that books continued to be read aloud well into the late Middle Ages. Of course, multiple kinds of reading on a continuum from private to public and from silent to voiced can coexist. Coleman has shown that public reading aloud persisted well into the early modern period as a form of literary entertainment.5 With that in mind, I would like to suggest that in the Boethius example, a prelector—a professional reader, who recited texts aloud—touched the figures in the miniature depicting Boethius speaking with Philosophy. The prelector particularly targeted their faces, as if he were enacting their conversation. As I argue in this chapter, reading aloud embodied gestures that would help the prelector to interpret the text and magnify the images in order to draw listeners in.

I would like to take Joyce Coleman’s well-argued ideas a step further to ask how images might have functioned in the context of aurality (that is, in listening to texts being read and performed). And what was the role of the prelector in shaping the audience’s reception of the images? To begin addressing these questions, let me turn to another image from an illuminated Boethius, this one in an exquisite Italian manuscript (Fig. 120).6 The copyist signed his name “Brother Amadeus,” and the illuminator “Gregory of Genoa,” and they dated the work 1385. In the image Boethius languishes behind the bars of a Romanesque prison. A user has rubbed the building’s façade. Was he striking out against the fortress that imprisoned the great thinker? Pointing to it in order to draw his audience’s attention to the figure of Boethius? The exact ethical motivation behind the gesture is difficult to recover in this case. What is clearer is the scene in the historiated initial, C[arina] at the top of the folio. There is Boethius, dressed as he is in prison, but this time depicted as a teacher, showing his students a book. Two things are noteworthy about this image. The first is that the illuminator, apparently Gregory of Genoa, has carefully depicted Boethius’s book so that its pages are visible to his immediate audience gathered around him, and to us, outside the picture plane. The second is that the five figures gathered around Boethius sit close enough to be able to see the book. It is this arrangement of masters and students, or prelectors and audience members, that I would like to imagine throughout this study: audiences that can see the images in illuminated manuscripts, which are being read—and performed—by a prelector who moralizes the contents and shapes his audience’s reception of the text by showing the images, pointing to them, touching them, and animating them. The arrangement of prelector to his audience is closer than, say, the arrangement of a preacher delivering a sermon from a pulpit to his audience. The reading situation I am imagining is still hierarchical and moralizing, but much more intimate. The audience members would have been able to touch each other, smell each other, hear each other breathe, and would have craned their necks to see the images.

Although private silent reading was aided by such codicological developments as smaller books, spaces between words, and devotional literature apparently designed to be read alone and silently, public reading continued to entertain audiences.7 Indeed, literature written in verse form may well have been vocalized to make the most of rhythm and rhyme, which come alive during audible performance. How did the illuminations in manuscripts of courtly literature function in the context of oral performance? In some images of prelection, the reader faces his gathered audience, with his book on a lectern, so that the book would be visible to the reader but invisible to the listeners. In this set-up, the audience may not be able to see the images. There might be reasons to include expensive illuminations in manuscripts even if an audience is not going to see them, such as the prestige of owning luxury items, especially at the royal court. However, not all illuminated courtly manuscripts were made with the highest-quality materials nor made by the most prestigious illuminators, and not all would fulfill the requirements of a luxury manuscript. Moreover, other arrangements with the prelector, book, and audience are possible. I know from having been a curator for a number of years, and from having shown dozens of medieval manuscripts to hundreds of people, that the best way for the audience to see the manuscript is for a small group to gather around it, so that the prelector/demonstrator either forms part of this group or stands at the top of the manuscript. In the second scenario, at least six sets of eyes can look at the manuscript simultaneously. A medieval prelector in an analogous arrangement could have drawn the viewers’ attention to areas of the illuminations by touching them or tracing the visual narrative.

Use-wear evidence suggests that prelectors used illuminations as visual aids that gave form to the characters from the stories they were reading. Prelectors literally pointed these out with their fingers, and in so doing, made abrasive contact with the images. Secondly, they used images to animate the plot twists by pointing to figures while dramatizing the figures’ actions with their hands. Thirdly,—and I suggest this more speculatively—they used the images for rituals of reading that might have resembled those used by people taking oaths. These rituals referred to events in the texts and physically engaged their audiences (as in the case of the Vows of the Peacock, which I discuss later). My chief evidence to support these hypotheses is the patterns of wear in the manuscripts themselves.

I. Interacting with images of the Virgin

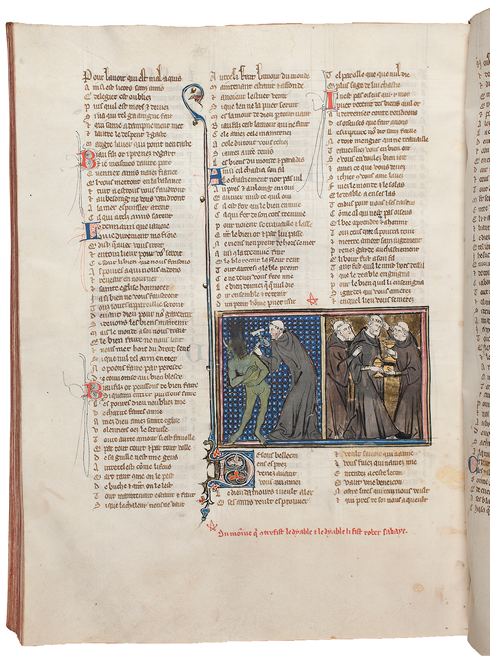

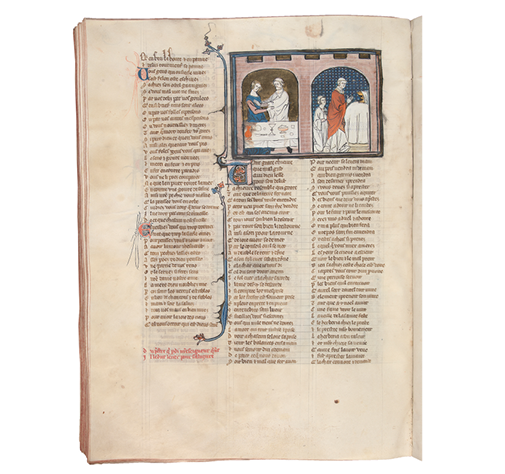

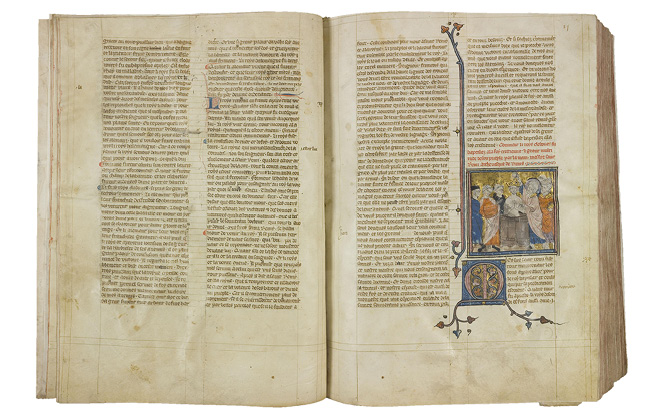

The Benedictine monk Gautier de Coinci (ca. 1177–1236) wrote Miracles of Our Lady, a collection of stories in praise of Mary. The stories demonstrate that venerating the Virgin yielded real-life results. Mary caught babies who fell out of windows, produced rose bushes on the graves of believers, squirted breath-freshening milk into the mouths of those with halitosis, and prevented wayward nuns from being caught and punished. Her interventions could be perceived in the physical world. Gautier set his text, the Miracles of Our Lady, to music; this meant that the poems had at least two outlets as forms of entertainment—as songs or as stories told aloud.8 Here I consider how a particular copy of the Miracles of Our Lady was read aloud (HKB, Ms. 71 A 24). I chose this volume because its provenance is known with some certainty and its early user exploited the images during recitations.9

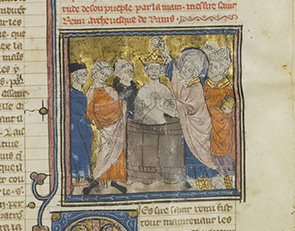

Male members of the high nobility were particularly keen to acquire a copy of his book.10 The copy under scrutiny here, HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, was ordered in 1327 by Charles IV of France (d. 1328), from the Parisian stationer Thomas de Maubeuge.11 As this manuscript eventually passed down to Charles V (d. 1380) and then to his son Charles VI (d. 1422), it touched the lives of at least three French kings. I argue that this book was read aloud in (semi-)public performances in which the prelector animated the images by touching them in order to amplify the stories’ messages. In this process, the prelector broadcast a legitimated, physical way of interacting with the images. Audience members were not only edified and entertained by the stories, but they also learned new, acceptable ways of handling the images in their books.

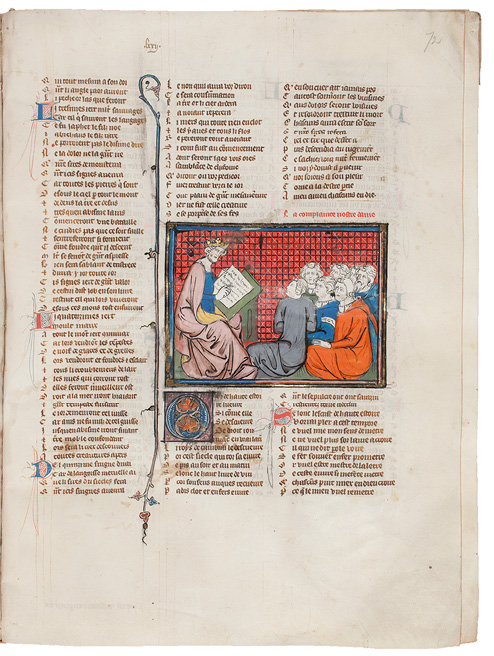

A miniature within HKB, Ms. 71 A 24 presents an image—albeit idealized—of how books at court were read publicly, which vindicates Coleman’s position (Fig. 121). One image, which accompanies the legend of the king reading a Marian story, depicts a king moving his finger along the text while reading from the inscribed page. His audience is single sex, which may reflect reality for some such courtly readings (but not all, as I will argue).12 As the image refers to precisely the kind of public reading that the Miracles of Our Lady anticipates, it is self-referential; normally, however, the king would not have performed the reading aloud, but would have delegated it to a professional prelector. This image presents a meta-narrative—a story read aloud about a story being read aloud. In addition to the signs of wear in the volume itself, this image attests that the Miracles of the Virgin was the kind of book that would have been read aloud at court as a form of entertainment. The acts of public reading detailed in this chapter would have taken place in castles, in rooms such as the great hall, where entertainments were staged.

Fig. 121 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the king reading. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 72r

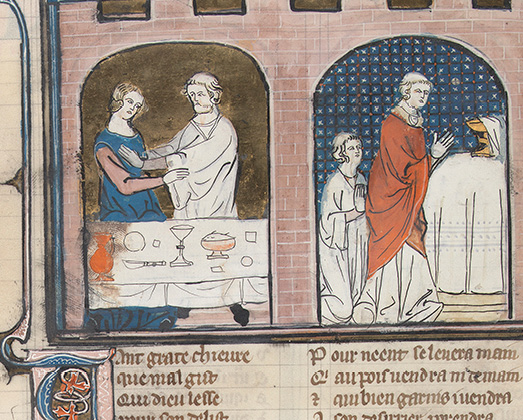

Bite-sized stories in rhyming French made for entertaining listening at court. Many of the stories describe images that have come alive and recount physical encounters with Mary and demons. There is a sense of yearning for the effects of prayer to be made manifest in the real world. The moralizing, episodic miracle stories tell of Mary intervening in sinners’ lives, often in the form of her sculpted image, and confirm the efficacy of interacting with a sculpted Marian object. For example, the opening sequence tells the story of Theophilus who has sold his soul to the Devil. He repents by praying to an image of the Virgin (Fig. 122). In the accompanying miniature, the sculpture has come to life: Mary makes eye contact with Theophilus, and Jesus reaches out toward him. In the next scene, she has sprung from her throne to do battle with the Devil, poking him in the teeth with a crucifix while simultaneously grabbing the contract for Theophilus’s soul (Fig. 123). She vanquishes the smooth-talking Devil by wielding her cross as a weapon and bludgeoning him in the mouth, the body part with which he had seduced Theophilus. She bodily destroys her foe. As I show below, the reader has imitated Mary by repeatedly attacking the Devil, or at least images of him, often focusing attention on the body parts that do the misdeeds. This turn of events—praying to an image of the Virgin in order to gain a physical benefit from an animate Mary—conditioned believers’ expectations that interacting with such images yielded real-world results. Rubrics and prayers throughout the book assume that images of the Virgin come to life, intervene, have opinions, and respond vocally to hearing prayers that praise them. Stories such as these shaped votaries’ behavior in front of (sculpted) images, while the actual performance of this particular manuscript shaped their behavior toward painted images.

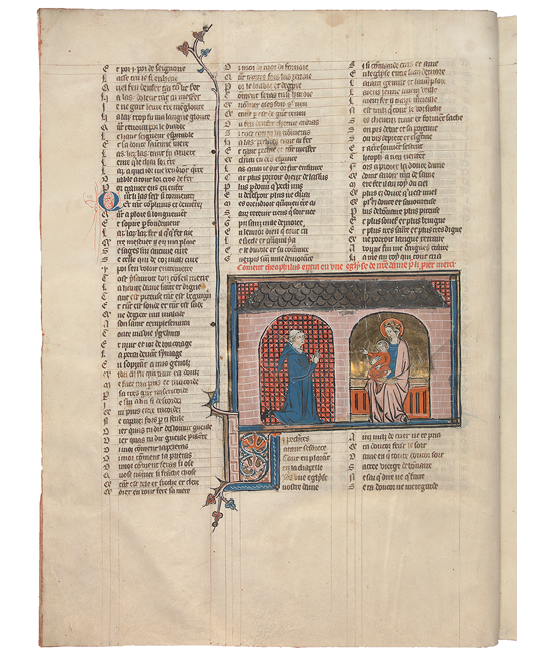

Fig. 122 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting Theophilus praying to an image of the Virgin. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 5v.

Fig. 123 Miniature depicting the Virgin battling the devil for Theophilus’s soul, from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 6v

Therefore, the hero is Mary, who rescues Theophilus from his plight by intervening at the eleventh hour. The villains are the devils and the Jews. As we will see, Gautier was fiercely misogynistic and anti-Semitic, qualities that may have appealed to Charles IV, who had expelled the Jews from France in 1323. The plots in Gautier’s stories concern the Virgin rescuing people, but not just anyone: her favorites are rascals, heretics, thieves, adulterers, pregnant nuns, and converts.

Unlike the story of Theophilus, which serves as a frontispiece and receives six individual scenes, the other stories each receive only a miniature, two columns wide, and are concomitantly limited in the complexity of the stories they can tell. Most of these are divided into two vignettes, which show a before and an after. Many of the images are about characters externalizing their guilt. One miniature, for example, shows the legend of the Burgundian pilgrim Girard; he is possessed by the Devil, has an illicit sexual affair, and then cuts off his own genitals (Fig. 124). The Devil, who is possessing the pilgrim Girard, points to the knife with which the pilgrim makes the irreversible cut. One can imagine a public recitation in front of a group of courtly men, who would shift uncomfortably in their seats as their bodies reacted to a story of malevolent orchiectomy. In order to raise the drama, but also to dispel some of the tension through humor, the reader turned the book toward the audience and attacked the Devil’s face, as if to reprimand and denature him. The prelector did this by drawing his finger across the image. With his audience tightly drawn in, they would have heard the prelector’s fingers launching granules of pigment from the parchment. In other words, erasure formed part of the public performance.

Fig. 124 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the pilgrim Girard. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 24v

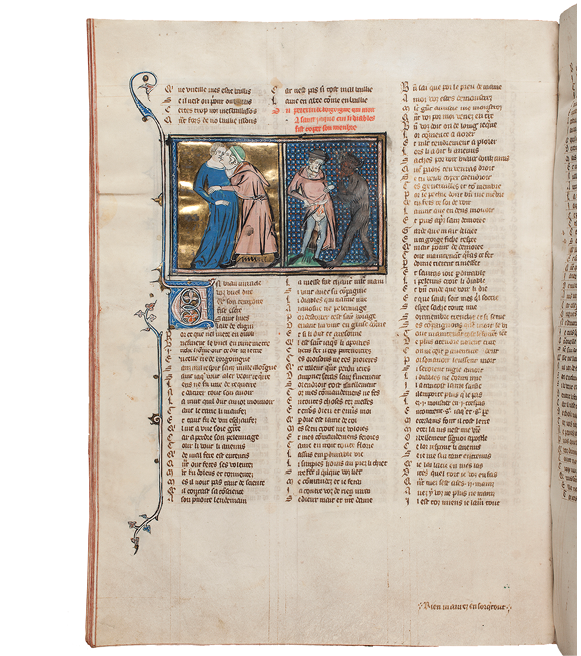

Many of the images themselves are about touching images; their very themes normalize such acts to the book’s original users, thereby making the touching of images in books a related, and equally normalized, aspect of interacting with them. In one vignette, devils carry a monk away like a sack of potatoes while St Peter pleads with the Virgin (Fig. 125). He does this by bending in humility and placing his hand on her abdomen, as if appealing to the fruit it once held within. Once again, the image depicts an occurrence in which someone is using physical contact to try to effect a change. St Peter is touching the standing Virgin in order to convince her to intervene.

Fig. 125 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the monk adoring St Peter. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 23v

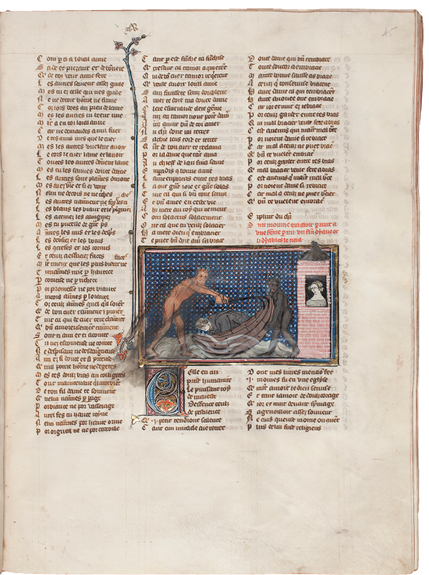

The stories recounting the travails of monks who had sexual affairs apparently amused courtly audiences. In one story, a monk is sailing toward his lover, who eagerly anticipates his arrival (Fig. 126). However, exteriorizing his guilt, devils (who both urge his transgression and torment him for it) begin shaking his boat to and fro, which makes the monk vomit over the side. In reciting the story, the reader has not only attacked the devils’ faces, jabbing at the light brown one with particular rancor, but has also made a large, moist gesture, through the monk’s head and then into the sea. One can see that the gesture involved not just a wet finger but a wet hand: the black line adjacent to the gold frame has been smeared far into the margin, and the gold frame itself has been worn down, as by the effects of many repeated gestures, not just one. Was the prelector dramatizing the monk’s sickness by wiping his wet hand from the monk to the margin, as if to trace the trajectory of the vomit?

Fig. 126 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the monk who visited his lover by boat. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 45r, and detail

One story tells the legend of the monk making an image of the Devil and then robbing his abbey (Fig. 127). This story and its accompanying image form a twist of the Pygmalion myth. The monk may not fall in love with the object of his creation, but at least is so deeply affected by it that he turns into a thief, as if the Devil made him do it. What is particularly fascinating is that the illuminator has shown the artist-monk sculpting the face of the nearly life-size image, thereby giving final expressive form to his creation. But as swiftly as the sculptor can make the object, the reader blots it out: the reader has wiped the Devil’s face to oblivion through repeated touching.

Fig. 127 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the monk making an image of the devil and then robbing his abbey. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 101v

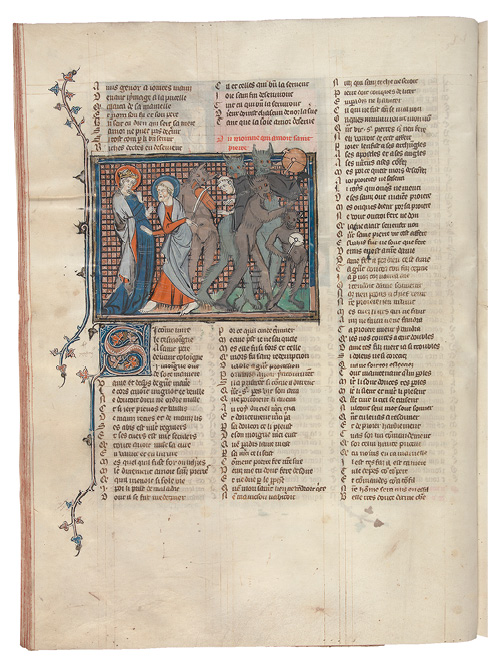

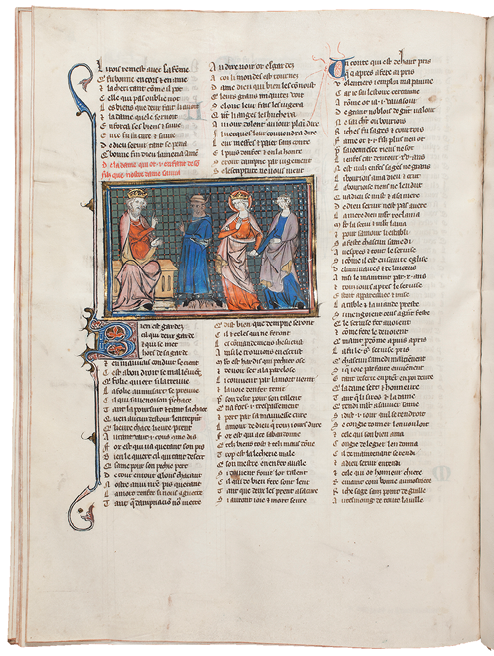

Likewise, in the legend of the woman having a child by her son, the illuminator has identified the transgressive son by giving him demonic horns (Fig. 128). An enthroned king shakes his finger at the man, and the Virgin shelters the impregnated woman, representing her before the king as if the Virgin were an attorney. The reader has demonstrated his moral stance on incest by inflicting a further humiliation on the man, by rubbing out his face. This is the ultimate badge of dishonor, one that is indelible. The illuminator distinguishes between those who are possessed by the Devil (such as the man who had committed the Oedipal act with his mother) and those who are controlled externally by a physical, diabolical force. Examples include the legend of the cursing child, in which a cacodemonic puppeteer operates a young boy’s face and jaw (Fig. 129). The book’s prelector has attacked the devil but not the young boy, as if condemning the boy’s behavior without erasing him altogether. In the legend of the hermit who saw a good and a bad soul ascending from two dead men, the structure of the miniature pits the two dead men against each other, with the devils on the left (or sinister) side of the divider (Fig. 130). As the two souls are lifted from their respective bodies, the one lifted by an angel is spirited away symmetrically and peacefully and only needs a single escort, while the soul destined for hell pitches and flails, and is ferried by two hairy heavies. The prelector has annihilated the devils’ faces here, leaving only one red tongue in a sea of black blur. One can imagine the audience cheering as the prelector defaced the antagonists.

Fig. 128 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the woman having a child by her son. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 145v

Fig. 129 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the cursing boy. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 150v

Fig. 130 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the hermit who saw a good and a bad soul ascending from two dead men. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 157r

Not all the devils have been attacked. For example, the illumination on folio 23v, which visualizes the legend of the monk adoring St Peter, has not been rubbed. This suggests that the person who inflicted the damage was not a silent reader who slavishly went through the entire manuscript to destroy devils, but rather that the damage occurred during performance, and that the public reader simply skipped over some stories but told other favorite ones several times. Perhaps the audience was more interested in hearing about the man who, possessed by the Devil, cuts off his own privates, than about the man who worships St Peter rather than Mary and is tortured for his choice. In fact, the prelector has largely ignored the stories concerning women protagonists. For example, the legend of the woman recovering her sight (folio 166r) remains in pristine condition. Likewise, the prelector either skipped or did not feel the need to animate the legend of the nun chased away from the cloister for burning the Devil (folio 25v). The illuminator, rendering his work in strong gestural language, gave his subject—a nun in a habit—large hands athletically outstretched in prayer as she tries to defend herself against a pit of barking monsters. Her plight, however, did not attract the performer, and there are no traces on the page to indicate that he animated this one before a live audience. The prelector was both selecting and interpreting the stories and making meaning of the images for the audience. In short, he was curating the manuscript’s public reception.

In addition to rubbing out devils, the prelector directed attacks against non-diabolic figures, and other body parts and objects. On folio 119v the image illustrates the legend of the priest who lost a place in heaven for committing lechery (Fig. 131), which rests upon the idea of touching: the lecherous priest is reaching out with both hands to grope the woman at the table. The left side of the image—where the priest’s touching is taking place—has been smeared, and there is a visible fingerprint on the tablecloth, as if the prelector were also groping the woman and reaching approximately for her knees.

Fig. 131 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the priest who lost a place in heaven for committing lechery. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 119v, and detail

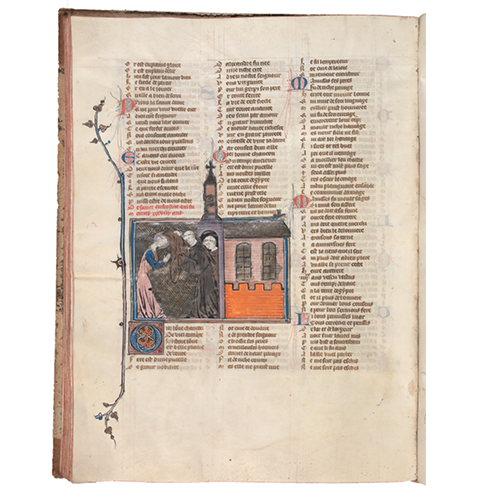

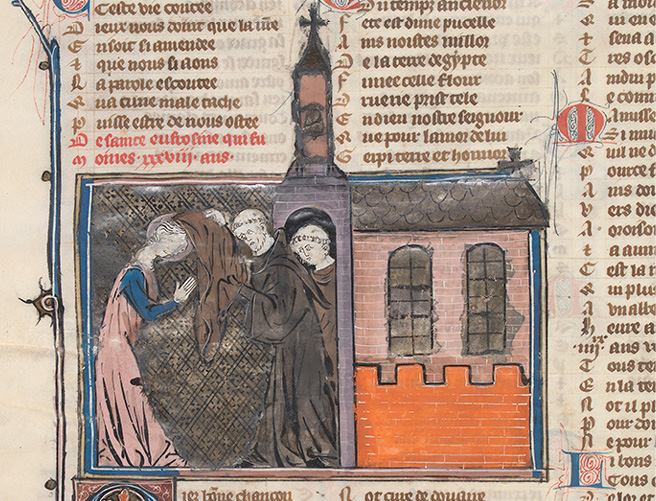

Folio 61v depicts the discovery of the real sex of St Euphrosyne: when she was unveiled, her uncloaked body revealed her sex. The prelector has wiped out her face, even though she is a saint. More important for him and his audience was the fact that she dressed as a man (Fig. 132).13 Her long slender neck—the most feminine feature that the illuminator gives her—has been annihilated. When she is uncloaked, both her accusers and the storyteller attack her femininity. This pattern of wear shows that the prelector did not want to attack the character’s face but was more meticulous in his choices.14

Fig. 132 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the discovery of the real sex of St Euphrosyne. Paris, 1327.HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 61v, and detail

Likewise, in the story of the Devil defenestrating a child, the reader has attacked the antagonist in specific ways in order to nuance the performance (Fig. 133). The story takes place in Laon, a place of pilgrimage especially for the blind. A boy called Gaubert has travelled there and is staying in a hotel several storeys tall. The Devil, disguised as a man, pushes him out of a window. The fall breaks all the bones in the child’s body. The shattered boy calls upon Mary, who sets him on his feet. One can imagine that the prelector—upon arriving at the story’s climax—turned the open manuscript toward the audience, reached toward the miniature, and rubbed the hairy brown monster with a gesture of contemptuous negation. Signs of deliberate damage, still visible on the page, show that the prelector attacked the face of the Devil but also targeted his arms, which were the body parts the Devil used to perform his diabolical deed. Indeed, the Devil’s shoulder has been rubbed all the way down to the parchment. Perhaps the prelector punctuated his theatrical gesture with a disdainful grunt. Rewarded by the audience for eliciting their engagement, the prelector used the same attention-grabbing gesture every time e revisited this story. The abrasion is clearly the result of several retellings.

Fig. 133 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the legend of the child defenestrated by the Devil and caught by Mary. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 165r, and detail

Traces of wear reveal a similar performance in the story of the illicit love child: a woman is impregnated by a cleric and then throws the baby into a toilet (Fig. 134). The prelector’s attack is even more pointed here. He condemns the woman by striking at her hands, as they are the agents perpetrating the infanticide. By licking his thumb and attacking the book, the prelector further dramatizes his performance, adding rhetorical flourish as if exorcising the woman’s sin. One can imagine the audience booing when she is about to drop the baby and cheering when the reader condemns the act. In showing his disapproval with an iconoclastic gesture, the prelector once again condemns not the woman per se, but her behavior, by rubbing out the hand that is casting the child to its mucky death.

Fig. 134 Folio from Gautier de Coinci, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, with a miniature depicting the story of the illicit love child thrown in the toilet. Paris, 1327. HKB, Ms. 71 A 24, fol. 14r, and detail

Later in the book, when the prelector reaches folio 176r, he tells his audience the story of the woman who has three children by her uncle. He shows his audience the illumination during the part of the story when one of the seductions takes place, but he does not touch the picture: a man at the French court would hardly be in a position to condemn infractions of consanguinity or extramarital sexuality.

I have shown how the illuminator anticipated the audience for the volume of Gautier de Coinci’s miracles and that the damage to the miniatures reveals how the manuscript might have been used, not just as a substrate for the text, but as a prop in the narration of the tales. The attitude toward pregnancy and childhood is sanitized, aimed at a courtly male audience, and its imagery therefore contrasts sharply with that in manuscripts made for women’s private devotion. Like the image of Mary represented in the frontispiece miniature, the prelector can command the book and vanquish the illuminated Devil. Consequently, the late medieval reader and the audience he entrances fight alongside Mary and thereby become heroic players in the narrative.

I have argued that the prelector animates the images by physically interacting with them in front of his audience. Those audience members therefore witnessed a way of interacting with books that gave the image utmost relevance. The prelector will return the book to its shelf in the library. When a subsequent reader opens its pages, he will encounter the rubbed-out devils, the dramatic censure, the animated vomit, the bare elbows of the nefarious defenestrator, and other traces of the former performance. Through this encounter with the used book, the reader would learn a new way of reading and integrating outrage at the antagonists—by striking their images. Having become a prop in a dramatic performance, the book shapes the subsequent reception of its images.

II. Political touching

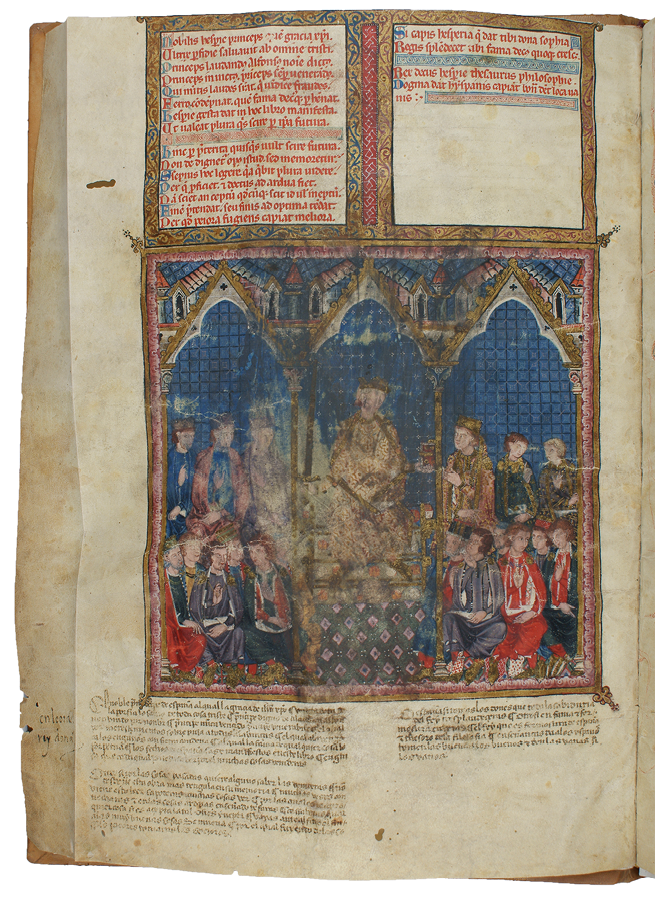

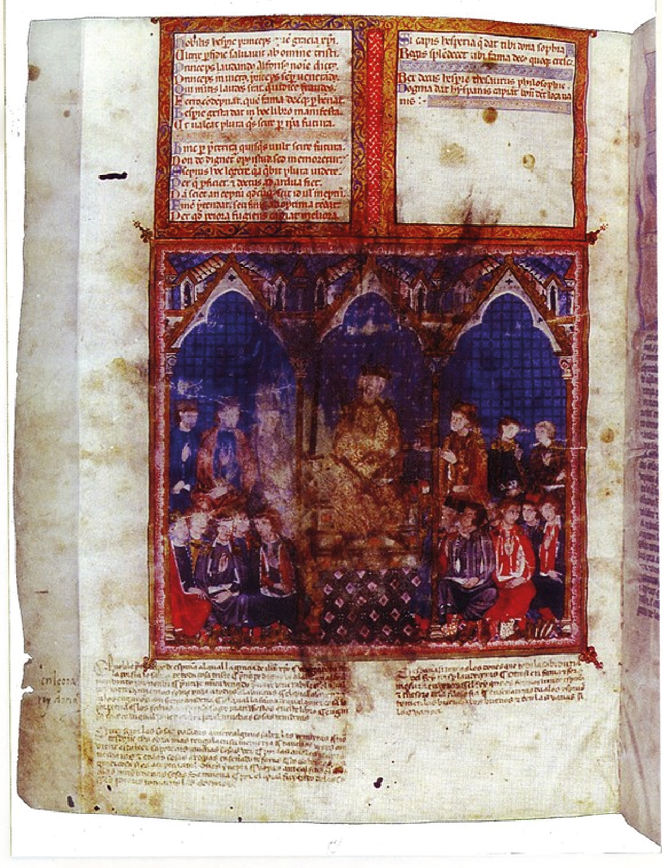

Just as tactile gestures between nobles were used to establish hierarchies or to publicly display amicability, touching also had political significance in certain illuminated manuscripts. The Estoria de Espanna, started for Alfonso X (1221–1284) around 1272–74, contains an account of Spain’s history from Noah to Alfonso II of Asturias. The elaborated painted first folio did not co-originate with the rest of the manuscript (Ms. Escorial Y.I.2, fol. 1v; Fig. 135). It depicts Alfonso X, the Learned King, presenting a copy of the work to his heir, surrounded by members of the Castillian royalty in the upper tier, and lesser courtiers in the lower. The top of the sheet contains a laudatory poem in Latin about the virtues of Alfonso X, composed in a commemorative tone and written in a red display script, with decorated uncials and decorative line fillers between the stanzas: it is written in the language of ritual recitation, distinguished from the quotidian prose in dark brown ink in the rest of the manuscript. At the bottom of the folio, a later hand has inscribed a loose translation of the Latin poem into Castilian. Laura Fernández suggests that the vernacular translation was inscribed in the fourteenth century, during the reign of Alfonso XI.15 Just as the selection of his heir was controversial in the thirteenth century, so too has the identity of the figures in the image been debated by scholars. Alfonso’s oldest son, Ferdinand de la Cerda, died at the age of 20 in 1275, and the next in line for the crown should have been Ferdinand’s son, also called Alfonso. However, Ferdinand’s brother, Sancho, built allies among the nobles and had himself declared King of Castile, León, and Galicia in 1284. He ruled as Sancho IV until his death in 1295. A powerful minority contested Sancho IV’s legitimacy, but the new king cemented power by executing those who wanted to restore Alfonso de la Cerda, the son of Ferdinand, to power. In the image, whether the figure next to Alfonso X represents Ferdinand de la Cerda, Sancho IV, or Manuel, the youngest brother of Alfonso X, who later played a role in the dynastic conflicts against Alfonso, depends on the date of the leaf. Relevant to the context of the current book, the image has been heavily and deliberately touched.

Fig. 135 Folio painted after 1284 (?) depicting Alfonso X flanked by courtiers, inserted into the Estoria de Espanna, made ca. 1272–74. Madrid, El Escorial, Ms. Y.I.2, fol. 1v (photographed after restoration)

Both Laura Fernández Fernández and Rosa Maria Rodriguez Porto have interpreted the image based on the signs of wear on the frontispiece miniature.16 Two of the figures have been smeared to oblivion: Alfonso X and the figure seated to his right (the one apparently receiving the sword of rule). The latter’s identity is uncertain because the exact type of hat he wears has been obscured by abrasion, but it is probably a short cap like those of the others at his hierarchical level. Alfonso is presenting a book to a man standing to his left, richly dressed in silk trimmed with gold. Following Ramón Menendez Pidal, who published the Estoria de Espanna in 1906, Rodriguez Porto considers this figure to be Alfonso’s heir, Ferdinand de la Cerda (1255-1275). This would suggest that the folio was made before 1275, but such an early dating is far from certain. Although Ferdinand de la Cerda died at the age of 20, he managed to have two sons first. Perhaps the gold-clad figure represents Ferdinand’s son, Alfonso de la Cerda (d. 1284), who was next in line for the crown. If so, then a date for the sheet between 1275 and 1284 is likely. Both Fernández and Porto see the smearing as hostile defacement, with Porto reading the miniature as one wiped with a wet cloth, a “criminal instrument,” in what amounted to an iconoclastic act. In short, they see an image attacked and effaced as a result of political upheaval. In their interpretations, Sancho IV or someone in his court committed the deed, wiping away and thereby mutilating his foe, Alfonso de la Cerda.

Fig. 136 The same folio (Madrid, El Escorial, Ms. Y.I.2, fol. 1v), as printed in Diego Catalán, De la silva textual al taller historiográfico alfonsí (Madrid, Fundación Ramón Menéndez Pidal, 1997), Pl. 1 (photographed before restoration)

Some time between 1997 and 2010, the Escorial cleaned the frontispiece in the name of restoration (Fig. 136). Significant smearing is evident in the pre-restoration image, whose comet-tails have been erased during restoration. Whereas the excess paint smeared onto raw parchment was swabbed away in a conservation studio, the paint losses on the figures have not been filled in or repainted (as would be the convention for a panel painting). Therefore, the restored image clearly reveals the losses, but mitigates the smears. However, when we are looking for motive for the damage, its shape, which indexes the causal gesture, is more important than its extent. In the pre-restoration photograph, it is clear that several gestures were in play, and that multiple people inflicted the damage. Some members of the Castilian court deliberately touched figures, and others hesitantly touched the architecture. Damaging gestures included those directed at Alfonso X’s head, torso, feet, and at the area above his head; those directed at the two figures at Alfonso’s right hand; and those directed at the architecture; as well as brushing strokes that extended beyond the frame in all directions, toward the upper, lower, and lateral margins. To my mind, these marks are consistent with multiple people each reaching into the proffered book to touch the folio out of veneration, not out of spite. To touch a figure’s feet is to demonstrate humility and submission. (For an example, see Vol. 1, Fig. 29.) These gestures were enacted over a series of occasions, performed by multiple members of a courtly circle each touching the image in turn.

The damaging gestures may have accompanied an act of oath-taking, as the smears resemble those seen in the Vows of the Peacock manuscripts (to be discussed below), for which, I propose, French courtly audience members took turns ritualistically touching images with gestures related to pronouncing a public testimony. The fact that the trails extend in several directions can be explained when one imagines the events: multiple courtiers arranged around the book (not unlike the arrangement depicted in the image itself), and each person reached his hand toward the image to touch it. The multiple incidents created a diffuse pattern, since each person touched the folio in a slightly different way and from a different angle. When the courtiers withdrew their hands, some left trails of loosened pigment. These trails point in the direction in which each participant stood around the open book. In this scenario, the damage was not made by a wet cloth, since wet cloths swipe a broader swathe and introduce significant moisture, which would cause the parchment to buckle. (See Fig. 9 above.) Furthermore, cloths remove pigment, yet I see pigment that has been smeared and rearranged, but not removed from the page in significant quantities. What Fernández and Rodriguez Porto regard as a single act of violence, I see as multiple acts of veneration. This alone is telling: love and hate can result in nearly indistinguishable forms of destruction.

I do agree with Rodriguez Porto that certain other manuscripts in circulation at the Spanish court were indeed touched in such a way as to deliberately obliterate particular figures; for example, someone has purposely attacked a figure in the thirteenth-century copy of Las Cantigas de Santa María, a compilation of Marian miracles set to music that was commissioned during the reign of Alfonso X. In his will, he stipulated that the manuscripts he commissioned be kept in the church where he was to be buried, and that the songs in the Cantigas be performed on the Virgin’s feast days. This confirms, as their content suggests, that the songs were designed to be sung in performance which, of course, could have involved animating the illuminations with physical gesture. Las Cantigas, which are now in the Escorial library (Ms. B.I.2), contain many illuminations depicting musicians, usually two per frame. One of these shows two lutists, a dark-skinned Moor and a light-skinned European, whose racial identities are reiterated in their contrasting dress. In modern times this miniature has been used in innumerable books and websites to demonstrate the religious and racial tolerance of Andalusia, where Jews, Muslims, and Christians worked, played chess, and made music together. What no one has noted, however, is that the face of the Muslim has been rubbed in a violent manner. Specifically, his eyes have been gouged with a sharp instrument in a back-and-forth gesture of erasure or negation. Given that many of the songs within Las Cantigas emphasize the Muslims’ failure to worship Mary, this anti-Islamic sentiment could have prompted the audience’s negative response to the image. The way in which the figure of the Muslim has been handled (rubbed in short, quick gestures, and gouged, in what may be a singular attack) contrasts starkly with the way in which the figure of Alfonso has been abraded (with long gestures performed over multiple occurrences). Given the strong contrast in handling of the two images, the readers of the Estoria de Espanna were probably praising Alfonso, not symbolically destroying him.

Moreover, other contextual clues, plus close attention to the patterns of wear on the frontispiece, reveal the positive motivation behind the damage. Whereas Rodriguez Porto suggests that the instrument of smearing was a wet cloth, I envision it as several wet and/or dry fingers, and the emotion behind the actions as exaltation, not wrath. Whereas deliberate destruction of a painted image often involves a vigorous side-to-side motion targeting the face, causing destruction in a single event, the gestures here are vertical, move through the entire face and body, and are the result of cumulative events. Those who touched the image also touched the architectural towers, part of the framing device around Alfonso. Touching decoration seems to accompany acts of reverence, not of destruction: participants wanted to make their mark on the page, as it were, but some opted to touch the frame rather than the figure. It is as if the person touching the image wanted to deflect some of his attention onto the decoration in order to preserve the image, in the same way that an osculatory target in a missal deflects wear away from the figure and onto an abstract shape instead. Essential to this act of touching was to demonstrate and register one’s group belonging.

Given that the frontispiece of the Estoria de Espanna has different ruling, text block, and script from the rest of the book, and that it was painted on a singleton folio by a different illuminator from that of the other illuminations in the manuscript, there is no reason to assume that the folio was made during the same campaign of work as the manuscript it prefaces. Laura Fernández Fernández, calling attention to these codicological features, also points out that the architectural frame—the very one that has been touched—does not appear elsewhere in the Alphonsian repertoire. This image therefore departs from the large body of work—which includes Las Cantigas and the histories—made during Alfonso X’s lifetime (1221-1284). I will not contribute to the debate about the dating of the leaf or the identities of the figures in the top row. However, I would like to revisit the chronology of the damage.

I suggest that performance involving the leaf encompassed an oral recitation of the laudatory Latin poem to a gathered courtly audience, followed by the more easily graspable vernacular version, together with ritual touching of the image, as if to praise the memory of Alfonso X. But when did this take place? A scribe in the fourteenth century added the vernacular translation of the laudatory poem at the bottom of the page. Because Rodriguez Porto argues that smudging occurred in the thirteenth century, during the reign of Sancho IV’s, she therefore must argue that the fourteenth-century scribe wrote on top of the smears. However, this cannot be the correct order of events. First, a scribe would not write over darkened, damaged parchment; instead, he would have avoided the marred areas. Moreover, the ink from the poem is also smeared, as the pre-restoration photograph shows. Therefore, the vernacular poem was inscribed on clean parchment, before the folio was ritualistically touched in the fourteenth century. The touching therefore postdated the vernacular poem. It did not condemn Alfonso, advance Sancho IV’s legitimacy, or even take place during Sancho IV’s reign. Instead, the touching post-dated the inscription of the vernacular poem in the fourteenth century and may have taken place during the reign of Alfonso XI (1311-1350). If the users had wanted to mutilate Alfonso X, they would have attacked the encomiastic poem, and they would not have bothered to translate it into the vernacular to make it more accessible. Rather, the courtiers handled the image glorifying Alfonso X in a manner consistent with the other fourteenth-century examples discussed in this volume: with gestures cementing group identity around a book. As an analogue, one can turn to the image depicting knights swearing an oath to King Louis of Taranto (Fig. 47 above).

Those who “conserved” the leaf in the twentieth century — by cleaning its grime and removing its smudges — obscured the use-history of this leaf. Dirt, dust, mutilations, fingerprints, gobs of wax, and trails from targeted touching all provide clues to a manuscript’s biography. To clean a manuscript is to make its history less knowable.

III. Rubbing romances

Medieval courtly audiences sought entertainment and moral education from literature that would have been read aloud. A significant number of surviving manuscripts have signs of targeted wear, apparently incurred during public performances of the sort described above. Populating the court were writers and translators including Laurent de Premierfait (c. 1370 – 1418), who wrote Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes, an enlarged translation of De casibus virorum illustrium by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375). At least one copy, written and illuminated in Paris around 1412, has been rubbed in a particular way, at the story of Anthony and Cleopatra (Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. Ser. n. 12766, fol. 236r; Fig. 137). The illuminator has shown the couple lying on a plinth, something between a bed and a tomb, to illustrate their double death. When Cleopatra saw that Anthony had stabbed himself, she held an adder to her breast to receive its venomous bite. The prelector has acted out this dramatic demise by striking at her breast as if his finger were the adder.17 In so doing, he has heightened the drama of his performance. This gesture points to a large number of similar gestures, whose tracks can be found in courtly manuscripts.

Fig. 137 Folio with the story of Anthony and Cleopatra, in Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes. Paris, ca. 1412. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Ser. n. 12766, fol. 236r, and detail

When considering the image of Anthony and Cleopatra in the context of its book, one can think about how the book was handled during performance. The miniature fills the width of a column on a page which is quite large: the manuscript is folio-sized. The miniaturist has omitted extraneous details, simplifying the image to its salient components: two dead people on a plinth, languishing under their respective instruments of death. One can imagine the reader, pronouncing the words aloud, and when reaching the climax of the story, drawing the audience’s attention to the image and enacting Cleopatra’s death, to make it palpable.

A. Performing dramatically

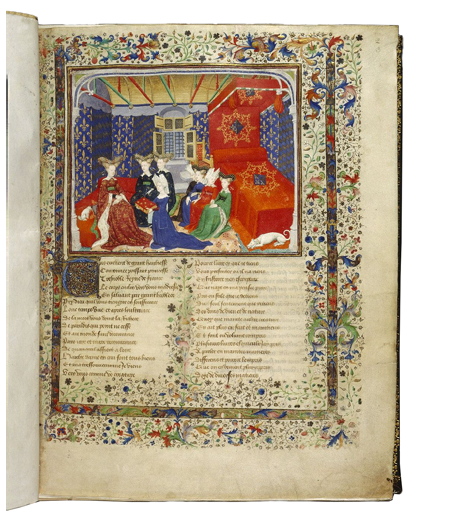

In most images—especially those made at court—that depict aurality, the audiences listening to a prelector are single sex. Images in a copy of the collected works by Christine de Pisan depict an all-female audience gathered around a book, not having it read to them, but witnessing its presentation (LBL, Harley Ms 4431; Fig. 138). The image shows Christine de Pisan presenting the book to Isabeau of Bavaria, queen consort of Charles VI of France, who receives the manuscript while framed by elegant furnishings. The manuscript also has a written dedication to queen Isabeau. She also receives the attention of all of the women in the room. Some of its images have been rubbed as if in the service of a dramatic performance, possibly to a female audience.18

Fig. 138 Folio from the collected works by Christine de Pisan with a miniature depicting Christine de Pisan presenting her book to Isabeau of Bavaria. Paris, ca. 1410–14. LBL, Harley Ms 4431, fol. 3r

Some of the stories in the manuscript, including the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, are retellings of Greek myths that were also included in Christine de Pisan’s L’Epître d’Othéa (Fig. 139). Late in life, King Peleus captured Thetis, a sea nymph, who tried to escape his clutches by transforming into various forces of nature. Eventually, however, Peleus caught and married her. They invited all the gods to their wedding except Eris, the goddess of the “twist,” who crashed the party anyway. The accompanying miniature shows the wedding banquet, where the goddesses wear crowns. At the top table, King Peleus sits among other men, apparently Zeus and Poseidon, who had both competed for Thetis’s hand in marriage (but backed off when it was prophesized that she would bear a son greater than his father).

The women who sit at the lower two tables converse rather than eat. Eris sows discord by gifting the wedding couple a golden apple, inscribed with the words “To the fairest.” This eventually becomes the prize in the judgment of Paris, the event which will catalyze the Trojan War. In the image, Thetis is seated at the lower table, with her faithful dog at her feet. Several of the other goddesses fuss over her belly, as she is pregnant with Achilles. More goddesses and well-dressed women sit at the second table, where a smug, crowned figure dominates the middle. This is Eris. She is the only figure who stares out of the picture plane. The represented women, as well as the live audience, are keenly aware of haughty Eris at the center.

Fig. 139 Folio from the collected works by Christine de Pisan with a miniature depicting the Wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Paris, ca. 1410–14. LBL, Harley Ms. 4431, fol. 122v, and detail

A reader or prelector has drawn attention to Eris by touching the miniature. In particular she (or he) has pointed out the goddess of discord by repeatedly touching her face and neck, with a back-and-forth gesture, as if acting out “discord” with a finger, while at the same time negating or punishing Eris.19 The reader has also targeted the golden object in front of Eris and has smeared the black ink that had visually rendered the gold disc into a three-dimensional plate. Perhaps the reader has, in drawing listeners into this image, attacked this item so that it plays the role of “golden apple” in an animated retelling of the story.

The reader has also touched the men at the top table, particularly the one in blue. This is apparently Zeus (aka Jupiter), who obtained the golden apple. As if telling the story of the apple’s peregrinations, the reader has traced the apple’s trajectory from Eris to Zeus, who is pointing to it in the image, just as the reader was pointing to it in lived reality. Zeus would then give the apple to Hermes and instruct the winged messenger to deliver it to Paris. What happened after that was war and chaos.

In the absence of a guide, this image is difficult to parse. The numerous figures are not labelled, it is not clear who the women are, the men also look alike and have few distinguishing features, and the actions (eating and gossiping) are not particularly dramatic. However, one can imagine that having a storyteller re-tell the story of Thetis’s wedding while pointing at the figures in the image and distinguishing them would make the re-telling vivid and immediate. In other words, the book’s reader dramatically portrayed the prophetic events on the page with a finger to give clarity to a complex narrative, while also making a somewhat static image more tantalizing.

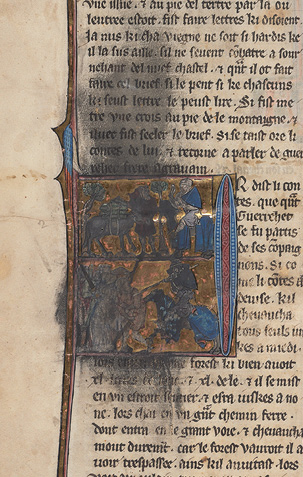

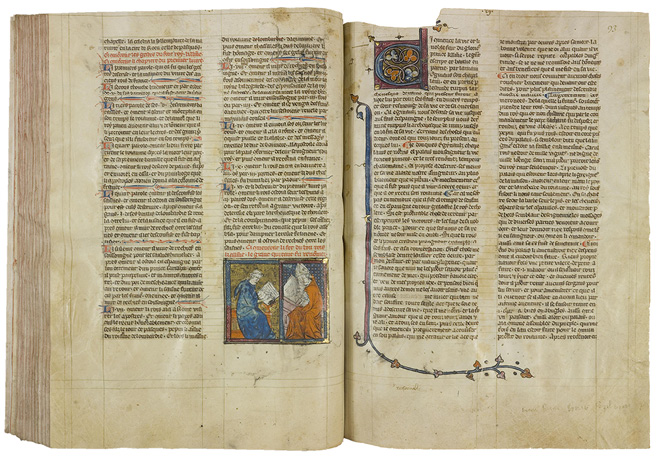

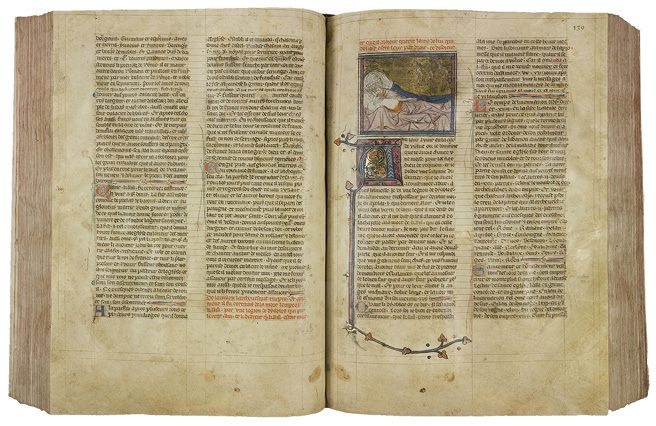

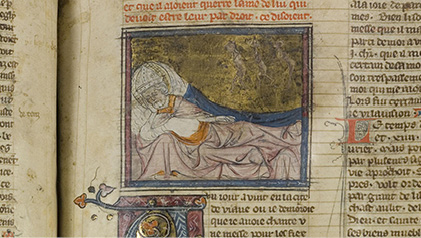

Similar signs of wear—which may signal dramatic performances that enhanced the vocalization—appear in manuscripts containing a variety of genres read and used at court, including Arthurian romances.20 In surviving illuminated medieval romances, the amount of wear is often extreme (yet unstated by catalogues and commentators). For example, a manuscript made in Northern France in the 1260s, which contains the Quest for the Holy Grail and the Death of King Arthur,21 has both inadvertent wear (brown crud in the lower and outer margins) and dramatic targeted wear (concentrated in the initial) (BKB Ms. 9627–28; Fig. 140). It opens with a historiated initial whose paint has flaked off to the point of near-illegibility. It may represent King Arthur and his knights taking leave from Queen Guinevere. The page, and indeed the entire manuscript, has been well-read and handled, but the degree of wear on the margins does not match that of the initial, in which about half of the paint has been worn off. This degree of pigment loss is consistent with the result of many readers who systematically touched the initial.

Fig. 140 Opening folio in the Quest for the Holy Grail, with an illuminated initial. Northern France, 1260s. BKB, Ms. 9627–28, fol. 1r, and detail

There are two major reasons for readers to touch an initial in this way. First: reader-performers touched images, including historiated initials, to draw the audience into the book and to animate the stories, as discussed earlier in this chapter.22 Second: readers touched initials to mark the beginning of a session of reading. The topic of touching initials will be taken up again below.

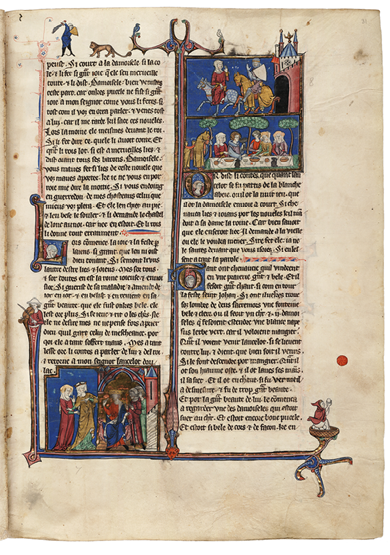

Many Lancelot cycles—including Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Douce 199—contain images heavily worn through deliberate touch. Made in France, ca. 1425–50, the manuscript measures 352 × 246 mm (with a text block of 238 × 132 mm) and comprises 324 parchment folios. It is large enough that between ten and twelve people could have gathered around to see the images with ease. Its mediocre parchment contains repairs from the time of production, as if the book had been designed for utility rather than as a showpiece. Fingerprints, smudges, darkened areas, and dripped liquid mar its interior, attesting to intense social activity around the manuscript.

The painted and gilt initials and illuminations that announce each new story in Douce 199 have been intensely rubbed (Fig. 141). The first miniature depicts Lancelot’s encounter with the knight Agravain, with the upper register showing Lancelot approaching a camp on horseback; the lower shows Agravain and a damsel, and Lancelot and Agravain again, this time at a tournament.23 The young Agravain had been warned to stay away from Lancelot, but he does the opposite and challenges the famous knight. In this uneven combat, Agravain breaks his lance, which lies in pieces on the ground. After that, the two fight on horseback. Lancelot (who moves from left to right, the direction of strength in most Western narratives) charges Agravain and wounds him grievously. The prelector has dramatized this duel by severely rubbing Agravain and even jabbing several times with a sharp instrument, a miniature sword brought to bear on the parchment. In other words, the reader himself embodies the protagonist by physically attacking representations of his foe.

Fig. 141 Folio in a Lancelot manuscript, with Lancelot’s encounter with Agravain. France, ca. 1425–50. OBL, Ms. Douce 199, fol. 1r, and detail

The dramatic and physical reading continues. In the next scene, Agravain’s brother Guerrehet, infuriated, attacks Lancelot and is thrown from his horse. The illuminator has shown Guerrehet at the center of the miniature, small, horseless, and defeated. If my hypothesis is correct, then to underscore the brother’s defeat, the prelector has rubbed Guerrehet’s face and hands to dust. The reader has dramatized other illuminations in the manuscript, but none so vigorously as this series of decisive combats.

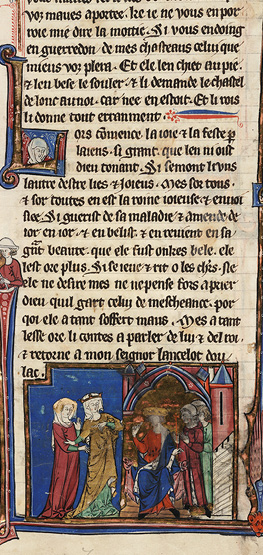

Traces of such performative reading behavior appear in a wide array of Lancelot manuscripts, including Beinecke 229 (New Haven, Yale University).24 This manuscript contains conspicuous stains and fingerprints—inadvertent wear—indicating that it was put to use, as well as showing signs of targeted wear. Among the touched miniatures is one within the story of Guerrehet (Fig. 142). It has been so damaged that the subject is difficult to discern from the abraded imagery and the story can only be gleaned from the text: Guerrehet encounters a woman whose husband has forced her to live as a chambermaid. In the top register of the image, another knight, Sagremor, arrives, and both knights are invited to lodge; however, the woman’s husband becomes suspicious of the two knights and surrounds himself with bodyguards. The bottom register shows the main action of the story: when the husband strikes his wife, Guerrehet and Sagremor kill the husband, his brother, and nephews.

Fig. 142 Folio in a manuscript with Arthurian romances, with the Story of Guerrehet and Sagremor depicted in a historiated initial. France, 1290–1300. New Haven, Beinecke Library Ms. 229, fol. 3v, and detail

Patterns of wear in both the upper and lower registers suggest that the prelector has acted out the results of this attack by striking the image of the wife (whose figure is now nearly illegible), as if to enact the vile deed that launched the ensuing bloodbath. Then the prelector has rubbed out the vanquished knights, thereby violently rehearsing the combat and their demise. This act, performed with the prelector’s body and voice, must have raised the dramatic tension of the story, as he recounted the mêlée with his finger on the painted page. One can imagine that the audience loved it, and demanded this story repeatedly, and that each time he did this, his dramatizations further damaged the book. This, at least, is a plausible explanation for the extensive damage, which has left the figures blurry and indistinct. The reader’s gestures have amplified the mayhem of the story.

Other figures in the Beinecke manuscript have been touched deliberately, such as the figure of Lancelot on fol. 31r (Fig. 143). In that image, Lancelot is seated among other characters, and only Lancelot’s face has been rubbed, as if the prelector were drawing the audience’s attention into the book and to the hero’s face in particular. The gesture has changed from the previous example, where the prelector must have moved his finger vigorously to act out the mêlée. Here he has a different purpose—to point out Lancelot—and the gesture is slower and more precise. The reader’s gestures aim to intensify the experience of the audience members and draw them into the stories. The marginal decoration reiterates this intention, with numerous images of figures blowing horns (such as on fol. 14r). The whole decorative program elevates the act of listening, by blowing the content of the book off the page and beyond!

Fig. 143 Folio in a manuscript with Arthurian romances, with a historiated initial depicting Lancelot enthroned and flanked by attendants. France, 1290–1300. New Haven, Beinecke Library Ms. 229, fol. 31r, and detail

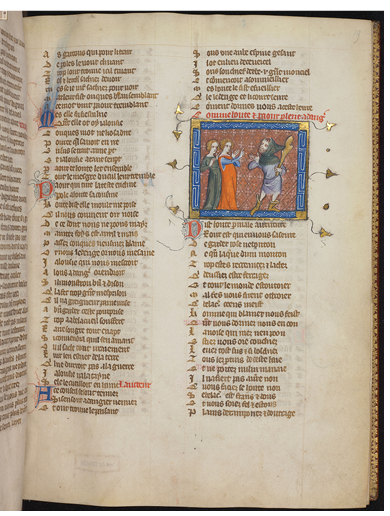

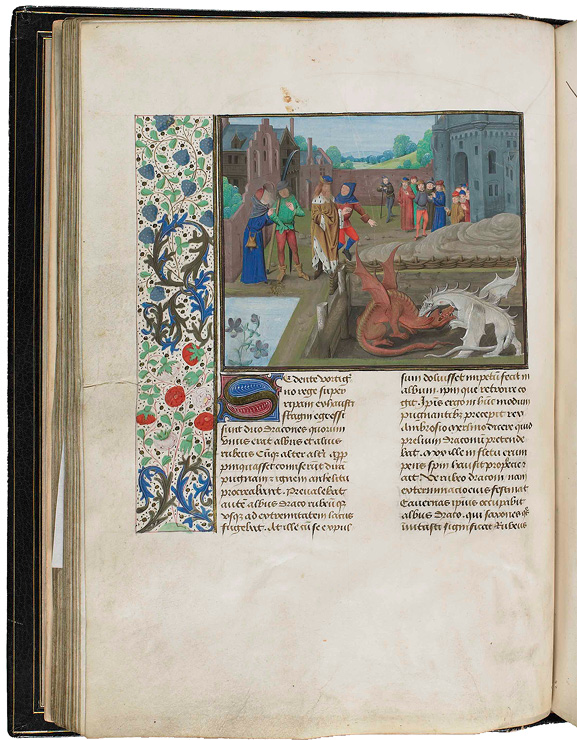

B. Taking oaths on birds

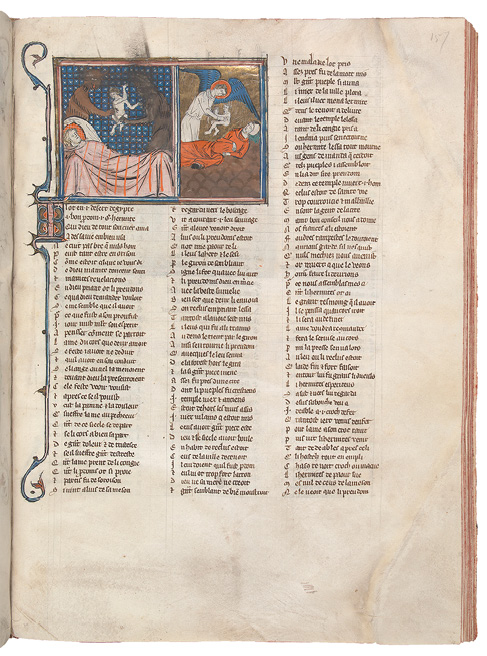

A large range of courtly romances exhibit signs of targeted wear, and perhaps the most dramatic destruction of images appears in several manuscripts containing the long poems Les Voeux du Paon (The Vows of the Peacock) and Le Restor du Paon (The Restoration of the Peacock)—a pair of chansons de geste written in 1312.25 Like other stories in this genre, the text was read aloud so that its audience could enjoy the performance of this particularly ribald tale in rhyming French verse. Full of sex and violence, the story forms part of an Alexander the Great cycle.26 Central to the plot is a ceremony that cropped up at various medieval European courts: namely, that knights would make vows on birds. Such a ceremony occurred, for example, at the Feast of the Swans that Edward I in England organized on 22 May 1306, on the occasion of his son’s dubbing ceremony, when his entire court took vows on a pair of swans.27 Even more famously, at the Feast of the Pheasant on 17 February 1454, Philip the Good of Burgundy had his courtiers swear on a pheasant that they would take back Constantinople from the Turks.28 Les Voeux du Paon presents a cultural ménage à trois: it marries a courtly practice (prelection) with a literary genre (romance) and a legal procedure (oath-swearing).

As the story opens, Clarus, the evil king of Ind, is trying to make Fesonas, the sister of Gadifer, marry him, so Clarus besieges the castle where Fesonas and other knights and ladies reside. While waiting out the siege, the nobles entertain themselves with sophomoric pranks. As a casualty of these, Fesonas’s peacock is killed. They make the best of the situation: the peacock is made the object of vows, upon which various knights and ladies swear to perform chivalrous acts, to marry, and to resurrect the peacock in gold. The book’s subject, therefore, is courtly entertainment and oaths, and these themes have been played out in the most physical way: several of the miniatures depict the vows, but rough handling — resulting from acting out the scene from the text — has rendered them nearly illegible.

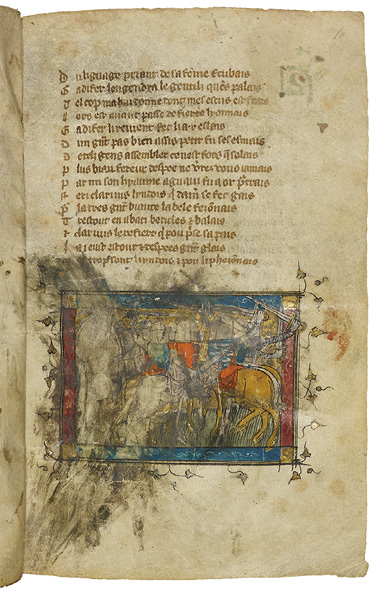

Douce 165 (Oxford, Bodleian), which contains The Vows and Restoration of the Peacock, has images that are rubbed all over. Virtually all of the miniatures have been damaged, yet the book has no pervasive water damage: neither rain nor flood could have caused this mutilation. Nor can the degree of wear be explained by regular hard use; rather the defacement most probably resulted from some form of ritualistic practice. This copy was made in Paris around 1340, and its illuminations preface the major narrative breaks. For example, the opening folio, which originally represented Alexander meeting Cassamus (the father of Fesonas and the enemy of Clarus), is heavily worn; its image has received targeted wear which demonstrates that this manuscript must have been handled in a ritualized and dramatizing way (Fig. 144).

Fig. 144 Opening folio in Vows of the Peacock, with a miniature representing Alexander and Cassamus. France, ca. 1340. OBL, Ms Douce 165, fol. 1r

Many people have laid their hands on the miniature and at the top of the open book. This is obvious because the paint has not just flaked off, but has been spread around, beyond the frame, and the marginal area at the outer top corner has become shiny with repeated touching. Is it possible that the prelector proffered the manuscript to members of the audience, each of whom touched the image? Did they imagine standing with Alexander as he pledged to fight alongside Cassamus? This stage trick of physically swearing would draw the audience into the book (literally) as the prelector read the text aloud. Each person touching the book once would explain this diffuse pattern of wear. Indeed, the bottom of the folio is also discolored, where the reader would have held the book to extend it to the audience. Given this physical evidence, it is plausible that the ritual surrounding this manuscript combined elements of oath-swearing and courtly entertainment, and that the audience’s participation reiterated themes in the story.

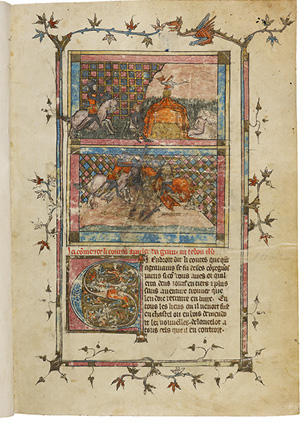

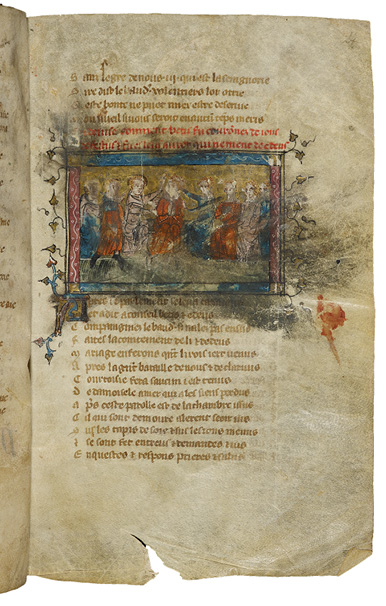

The image on folio 10r may depict Gadifer and Clarus fighting on horseback with swords and shields (Fig. 145). Which figure represents the hero remains unclear, but what is clear is that the reader touched the left half of the image violently and repeatedly but left the right half relatively unscathed. I suspect that this is because the audience identified with Gadifer and took him to be the figure on the left. The prelector therefore touched him not in order to rub him out (as a loser), but in order to carry out his oath to fight Clarus. With his finger, the prelector made Gadifer the active party who charges across the page to destroy his foe. In this way, the pattern of wear is not erratic, but reinforces the messages of the text.

Fig. 145 Folio in Vows of the Peacock, with a miniature depicting Clarus and Gadifer fighting. France, ca. 1340. OBL, Ms Douce 165, fol. 10r

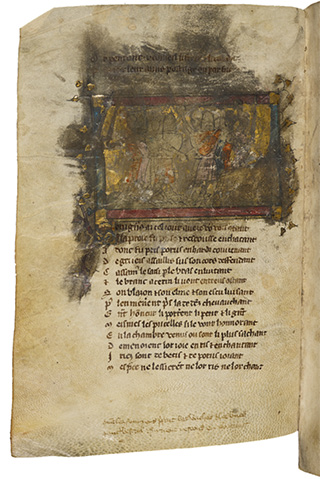

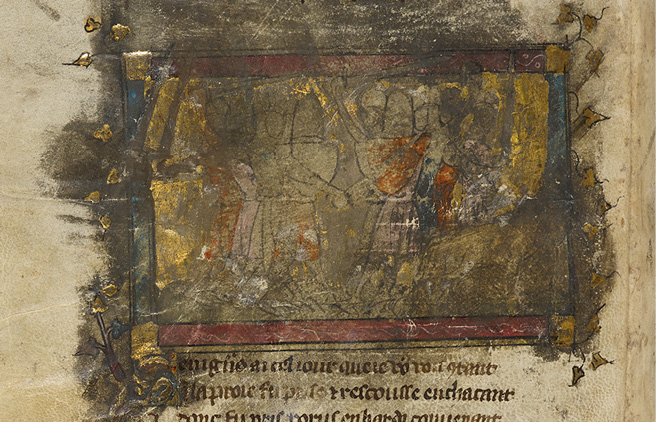

Later in the same manuscript an image depicts Betis being crowned “soothfast king” during the festivities in Venus’s chamber (Fig. 146). Again, the image is smeared beyond the frame. Plausibly, the prelector may have invited his audience members to symbolically crown the figure of Betis by placing a hand on the miniature. That most of the streaks extend into the right margin with paint that originated within the frame suggests that the touchers stood at the side of the book while the prelector stood at the bottom of the book, from which position he could continue to read. This has resulted in a diffuse pattern of wear, suggesting multiple people touching it, in a ritual of performance that played upon gestures of oath-swearing and king-crowning, and might have even involved an element of codified flirtation; there is no reason to envision a single-sex audience for this text. Participating in this smearing ritual could have formed part of the entertainment itself, as the audience enacted a coronation (such as that described in the coronation book of Charles V), with mirth and mock pomp.

Fig. 146 Folio in Vows of the Peacock, with a miniature depicting Betis being crowned soothfast king during the festivities in Venus’s chamber. France, ca. 1340. OBL, Ms Douce 165, fol. 24r, and detail

While the manuscript presents scenes of oath-taking, lovemaking, and chess-playing, it also includes several mêlées, for example on folios 53v (on horseback) and 58v (with hand-to-hand combat, Fig. 147). The wear on 58v is heavy, with the paint rubbed down to the underdrawing. The touching epicenter lies at the face-off, where the finger has scrambled the figures and traced the trajectories of the swords. I can imagine an event, or series of events, in which the prelector enacted the mêlée in the image by making his finger dance over the picture, to which the crowd responded with whoops of appreciation, egging him on. If the book’s destruction was part of the entertainment of the event, this would explain why it was produced on low-quality parchment full of holes, repairs, and stitches.29 The parchment itself is yellowish, brittle, and particularly variable between thick and thin, which is a marker of low-grade material. It was designed to be obliterated.

Fig. 147 Folio in Vows of the Peacock, with a miniature depicting hand-to-hand combat, possibly the capture of Porrus and Betis, in Vows of the Peacock. France, ca. 1340. OBL, Ms Douce 165, fol. 58v, and detail

Another miniature in the same manuscript depicts Gadifer cutting down the standard of Clarus’s army (Fig. 148). How this miniature was handled is typical for most of the other illuminations—with extreme gestures, but not sharp instruments. This seems to have been carried out using a dry technique, which has disproportionately dislodged the blue paint from the surface. (Blue pigment powder grains often have a large diameter, a small surface area to volume ratio, and poor adhesion.30) The gesture may have involved audience members taking quick jabs at the miniature, as if to help Gadifer topple the standard. Again, one can imagine the reader offering the book to the audience to participate in ritualized image-touching, a jocular parody of oath-swearing.

Fig. 148 Folio in Vows of the Peacock, with a miniature depicting Gadifer cutting down the standard of Clarus’s army. France, ca. 1340. OBL, Ms Douce 165, fol. 113r, and detail

On folio 138r the pattern of wear is different; the page marks the beginning of the second poem in the book, Le Restor du Paon. The miniature depicts men standing on the left and women on the right of a peacock on a pedestal, which has been “restored” as a golden statue (Fig. 149). Here the wear is more localized than in other miniatures. It appears that some readers dry-touched the men, and some dry-touched the women, and some the peacock. Therefore, it is possible that members of the audience identified with either the men or the women in the scene and touched just the appropriate figures, perhaps making their own oaths while identifying with the characters. One can imagine that the narrative, read aloud, created a situation in which the listeners enacted the deeds of the characters by playing out the oaths on the manuscript itself. These stories invited audience participation.

Fig. 149 Folio in Vows of the Peacock, with a miniature depicting men and women flanking a golden peacock on a pedestal. France, ca. 1340. OBL, Ms Douce 165, fol. 138r, and detail

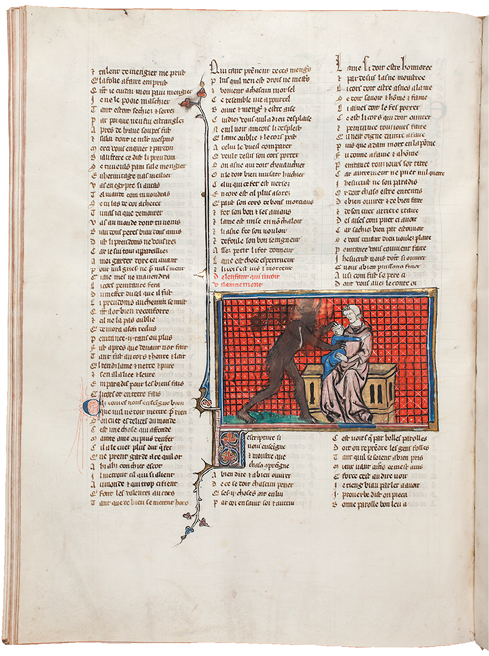

C. Curiosity

A similar pattern of wear appears across many manuscripts read aloud at court, and such reading behavior extends beyond the Vows of the Peacock. Guillaume de Lorris wrote Le Roman de la Rose in French verse around 1230 entirely to entertain and instruct courtly audiences. He died before he could finish the project, and Jean de Meun (ca. 1240-ca. 1305) completed it by adding some 17,000 lines around 1275.31 Despite being condemned by reformer and theologian Jean Gerson (1363–1429) as too salacious, the text survives in some 300 manuscripts, many of which date from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, indicating that the poem received sustained interest and continued to be recited over three centuries.32

In the text, the Lover (Amant) recounts a dream, in which he enters a walled garden, where he is attracted to a particular rose that represents the female beloved and her sexuality. Characters including Joy (Liesse), Beauty (Beauté), Wealth (Richesse), and Generosity (Largesse) appear in the garden, which belongs to Delight (Déduit). The rules of courtly love are laid out through interactions with these allegorical characters. For example, when the Lover tries to steal a kiss from the rose, he cannot; instead, he finds that the rose is suddenly ensconced in impenetrable fortifications. Jean de Meun’s contribution recounts innumerable antagonists for the Lover, who is blocked from the rose by Hatred (Haine), Iniquity (Vilenie), Lawlessness (Feloniye), Greed (Avarice), Envy (Envie), and Jealousy (Jalousie), among others. Moreover, Reason (Raison) discourages the lover. Nature alone eggs him on: Nature, who encourages human procreation, is the Lover’s greatest ally.

Many manuscript copies of the text were illuminated, including one made in Paris in the 1350s (HvhB, Ms. 10 B 29).33 The manuscript brandishes many signs of use, including dripped wax, presumably from a candle, and wet-touched initials (Fig. 150). Several of the images have been touched, including one depicting Nature as a smith (Fig. 151). In some manuscripts, Nature forges babies, and in this one she has inserted and withdrawn a phallic piece of metal into and out of a furnace and is banging it with a hammer on an anvil.34 If this lump of metal is to become a baby, it will require considerably more hammering. Fortunately, the book’s reader seems eager to help. Performed in front of an audience, the prelector’s actions could have animated the image or made the content more libidinous: whack! whack! whack!

Fig. 150 Folio in Roman de la Rose, by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun., with a miniature depicting Shame and Fear chasing Danger, and a wet-touched initial. Paris, ca. 1350–1360. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 29, fol. 19r, and detail

Fig. 151 Nature at her forge, in Roman de la Rose, by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun. Paris, ca. 1350–1360. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 29, fol. 89r

The figure is represented against a diaper background of blue and gold, in which each blue diamond contains the fleur-de-lis. The diaper background has been rubbed repeatedly (like that of the death portrait of Michel du Bec, discussed in Vol. 1, Chapter 6), to the point where the neat, geometric rectangles of gold have become globular organic shapes, and the black ink circumscribing them has been redistributed. Was the reader driven by the content of the story to touch the metal for him- or herself, up and down, several times? Was the reader acting out of curiosity about the textured surface of convex metallic squares interspersed with matte-finished high-friction blue and red ones? Did the reader achieve a micro-thrill of tactility when he or she stroked the patterned background up and down? The reader seems to be reenacting the process of forging, prompted by the subtle knobs in the surface of the painting, and has chosen to do so at the left side of the image, probably because that is where the longest run of uninterrupted textured shapes lies. Or perhaps a private reader was acting out a ritual of personal fertility. Or perhaps a prelector invited the audience members to touch the image and give in to their curiosity, and thereby extend the meaning of Nature. As Aristotle said, all humans by their nature are curious.

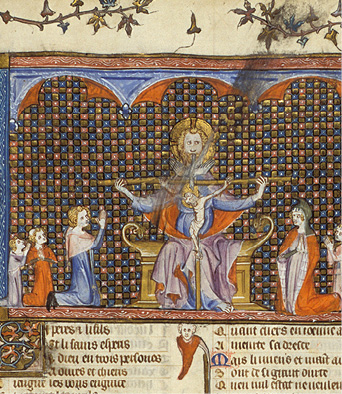

IV. Versified religion and history

The same volume with Le Roman de la Rose contains a second, lesser-known poem penned by Jean de Meun called the Testament (HvhB, Ms. 10 B 29, fols 124r–148r). The two texts were frequent co-travelers. The Testament, written in quatrains, begins by evoking the Trinity (Fig. 152). The illuminator has depicted the subject in the form of a Mercy Seat, flanked by male and female votaries. Marginal figures echo the voiced nature of the recitation: the long-eared rabbit and the hound listen attentively, while a monkey and a hybrid man bang a drum and blast a horn. They all reinforce the aural experience of the poem. One can imagine that the prelector turned the book toward the audience, who mirrored the kneeling votaries in the miniature, and that he traced the path of the Holy Spirit from the area beyond the upper margin of the page, down to the represented dove. After doing so, he then touched the decorated initial that represents the inspired words—inspired from the same stem as spirit—before beginning his own recitation. This and many other manuscripts read aloud at court have smeared initials, indicating that touching the initial publicly was a widespread gesture of the prelector.

Fig. 152 Incipit of Jean de Meun’s Testament, with a Mercy Seat framed by worshippers. Paris, ca. 1350–1360. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 29, fol. 124r, and detail

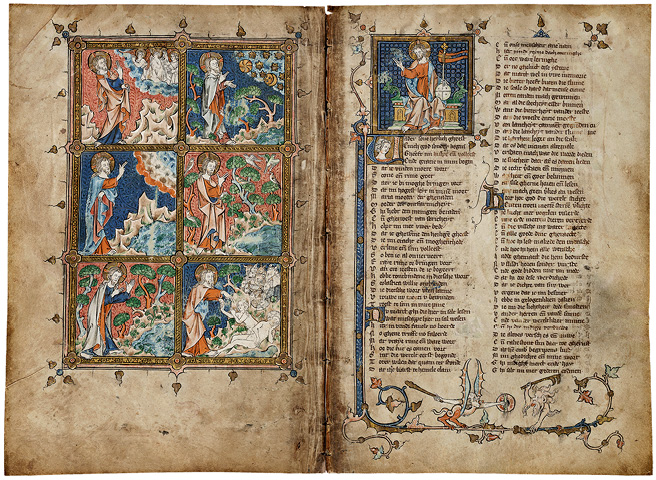

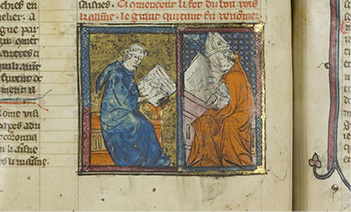

The same wet-touching techniques were practiced at Dutch-language courts with manuscripts authored by Jacob van Marlaent. Among his versified translations was the Rhimebible (rhyming Bible). One copy was written in Utrecht in 1332 and then illuminated by Michiel van der Borch (HvhB, Ms. 10 B 21).35 Its repeated hard use has left signs of inadvertent wear in the lower corners. Its reader has also targeted some of the images in specific ways. Like many readers of all kinds of performative literature, he has touched the first initial (Fig. 153). In this case, the image depicts Christ as Salvator Mundi, with his orb and bannered cross staff, as he glances across the fold to acknowledge God creating the world. The reader has touched the background behind Christ with a wet finger several times, near the sign of blessing, as if encountering the depicted gesture with a physical one. Deeper in the manuscript, the reader has enacted additional relevant gestures. For example, at the image depicting Jacob obtaining the blessing of his father Isaac in the presence of Rebecca, the reader has touched Isaac’s mouth which pronounces the blessing, and also his fingers formed into the sign of benediction (Fig. 154). It is as if the prelector were acknowledging the character’s speech act and tracing its constituent parts.

Fig. 153 Prefatory image and opening of Jacob van Maerlant, Rhimebible. Utrecht, 1332. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 21, fols 1v–2r, and detail

Fig. 154 Image depicting Jacob obtaining the blessing of his father Isaac in the presence of Rebecca, in Jacob van Maerlant, Rhimebible. Utrecht, 1332. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 21, fol. 15r

At the image of Moses and the burning bush, the reader has stroked Moses’s ankle and foot downward, as if playing the role of the prophet removing his shoes out of respect before the wondrous sight (Fig. 155). The reader has used a different stroke when encountering the image depicting the Israelites looking at and venerating the brazen serpent as a cure for snake bites (Fig. 156). Here he has jabbed at the page, making a twisting, negating motion upon contact. He has attacked the kneeling Israelite, and particularly targeted his folded hands that signify the man’s veneration of the serpent, in order to register his moral stance against the threatening idolatry. Many of the images in this manuscript have not been deliberately touched, but those that have attest to a lively and charged interaction with the images that bring them into a heightened state of moral relevance to the audience members.

Fig. 155 Opening in Jacob van Maerlant, Rhimebible, with a miniature depicting Moses before the burning bush. Utrecht, 1332. HvhB, Ms., 10 B 21, fols 22v–23r, and detail

Fig. 156 Miniature depicting the Israelites venerating the brazen serpent, Jacob van Maerlant, Rhimebible. Utrecht, 1332. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 21, fol. 35r

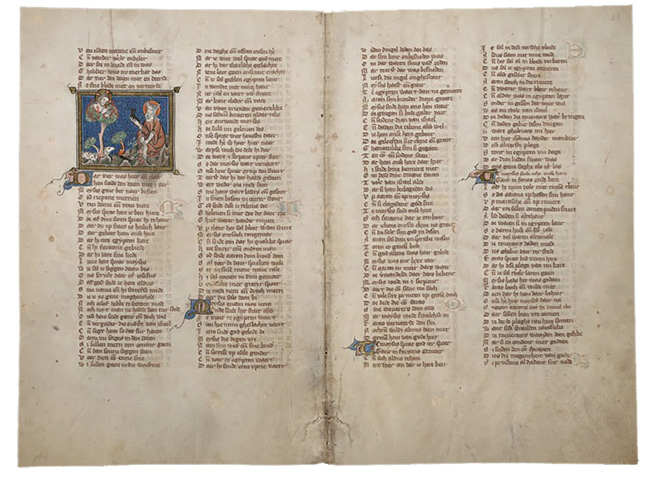

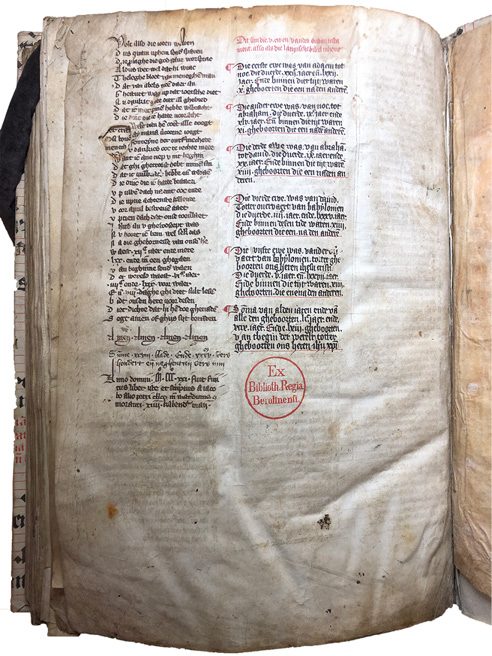

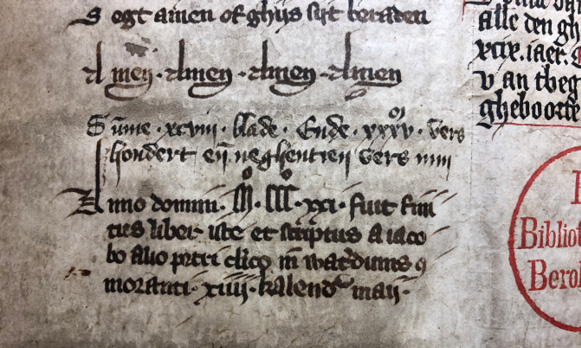

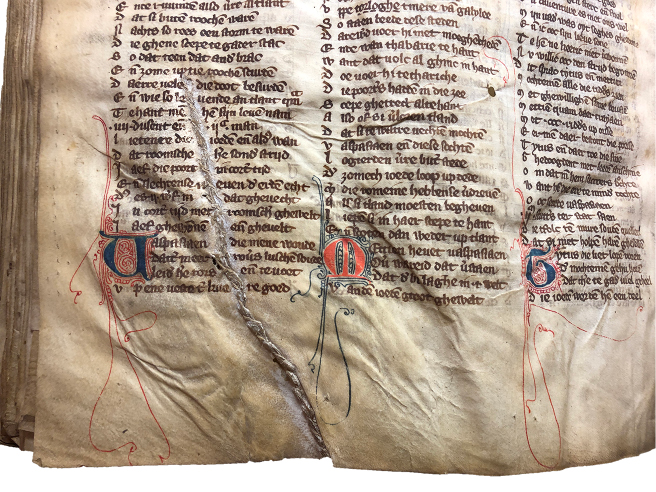

Another copy of Jacob van Marlaent’s Rhimebible (now Berlin, SBB-PK, Germ. fol. 622) was both produced with different parameters and used differently from the copy in The Hague.36 Berlin Germ. fol. 622 was made in Utrecht in 1321, as indicated by a colophon at the end of the manuscript: “Anno domini .M°. CCC°. xxi. fuit finitus liber iste et scriptus a iacobo filio petri clerico in waterdunis commoranti .xiiii. kalend mai” (On the 14th kalends of May in the year of our Lord 1321, this book was finished, and it was written by Jacob, the son of Peter the cleric, in Waterduinen; fol. 98v; Fig. 157). The volume contains historiated initials and Utrecht penwork (Fig. 158). The current binding, applied by H. Hoffmann von Fallersleben, who owned the volume in 1821, consists of medieval parchment cover that was once part of a late fifteenth-century illuminated music manuscript (Fig. 159). Handling this manuscript means de facto touching the miniature.

Fig. 157 Final folio in a Rhimebible containing the colophon and calculations of the manuscript’s line count. Utrecht, 1321. Berlin, SBB-PK, Germ. fol. 622, fol. 98v, and detail

Fig. 158 Folio in a Rhimebible with miniatures depicting the final days of Creation. Utrecht in 1321. Berlin, SBB-PK, Germ. fol. 622, fol. 2r

Fig. 159 Binding of a Rhimebible made in Utrecht in 1321, made in the nineteenth century from a medieval illuminated and noted manuscript folio. Berlin, SBB-PK, Germ. fol. 622, front cover