Chapter 5: Touching Death

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.05

Given the nature of Christianity—a religion of the book with a strong emphasis on death and resurrection—book-centered rituals, which mediated between the living and the dead, abounded. Because Christianity promised life after death, religious practitioners considered death a portal to a better world. The focus was not only on the death and resurrection of Jesus, but also on their own deaths. According to late medieval belief, the blessed (or elect) would go to heaven, some egregious sinners would go to hell, but most souls would go to Purgatory, which was like hell but had a terminus. As Jacques Le Goff showed in The Birth of Purgatory, this third place arose to provide believers with the comfort of knowing that the torture could come to an end.1 In Purgatory, the soul would be refined in the furnace so that the impurities could run off. The future of the soul was modeled on a metallurgical metaphor. According to medieval Christian belief, the dead could not pray, so they relied on the living to pray on their behalf to help release them from the cleansing fires. To create networks in which the living agreed to pray for the dead, brotherhoods formed, such as the brotherhoods of St Nicholas and St Sebastian, discussed in Chapter 2.

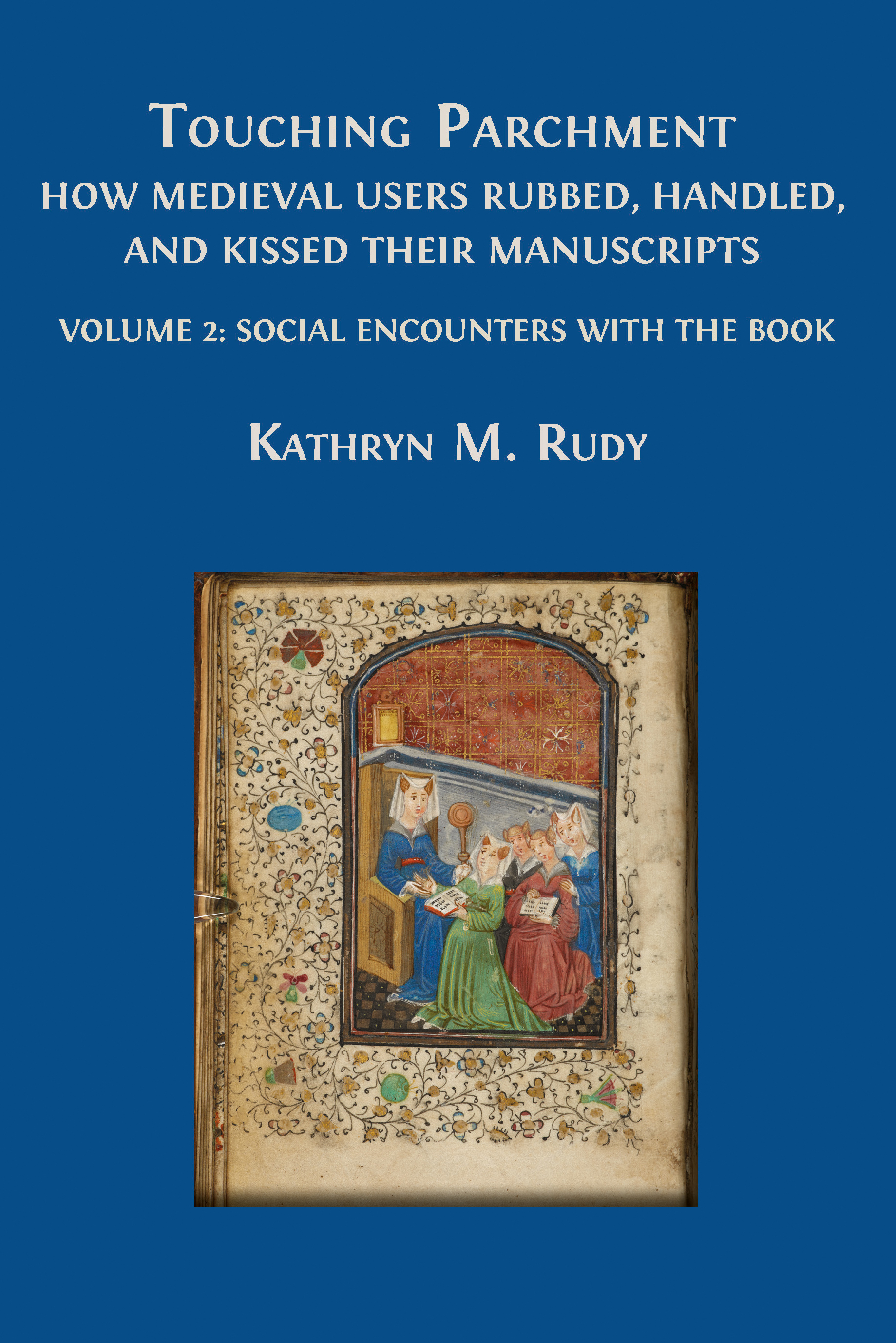

Families could also outsource this duty to monks or nuns, who could be considered professional intermediaries. For example, the Spes Nostra painting in the Rijksmuseum depicts Augustinian canons in the foreground praying on behalf of the dead (Fig. 169).2 The decomposing corpse in the foreground represents those for whom the canons are praying. This is not a specific person, but rather a generalized corpse that has been buried for some time, and whose corresponding soul has spent concomitant time being cleansed in Purgatory. The success of the canons’ prayers will determine whether the soul will reach Paradise, which is depicted in the background.

Fig. 169 Four canons and various saints by an open grave (The Spes Nostra). Oil on panel, Northern Netherlands, ca. 1500. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

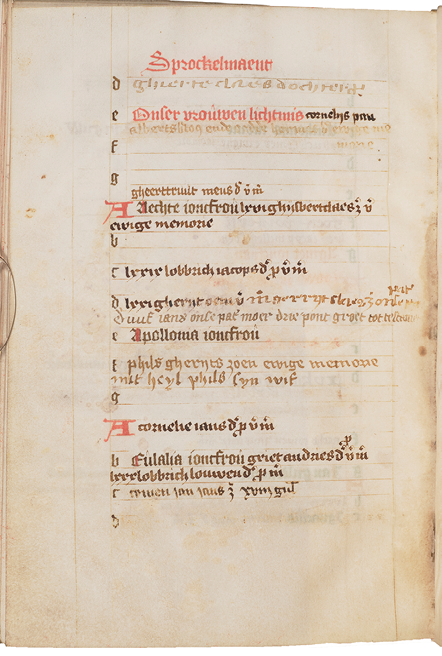

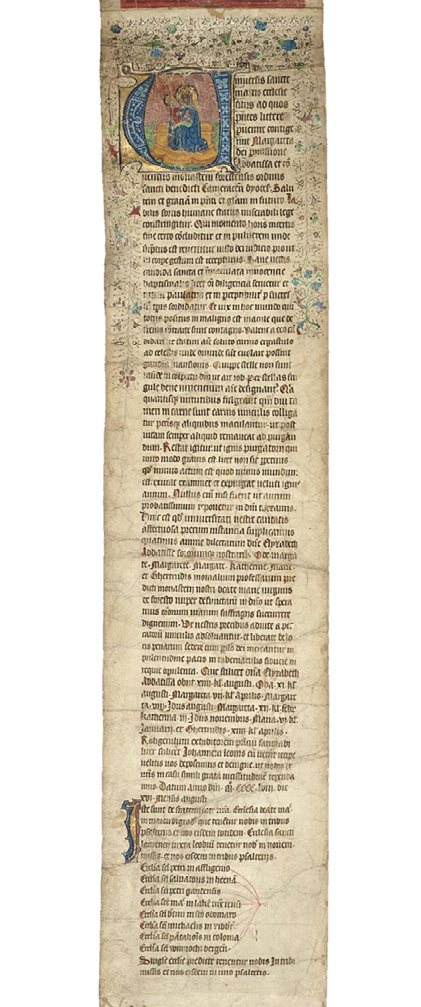

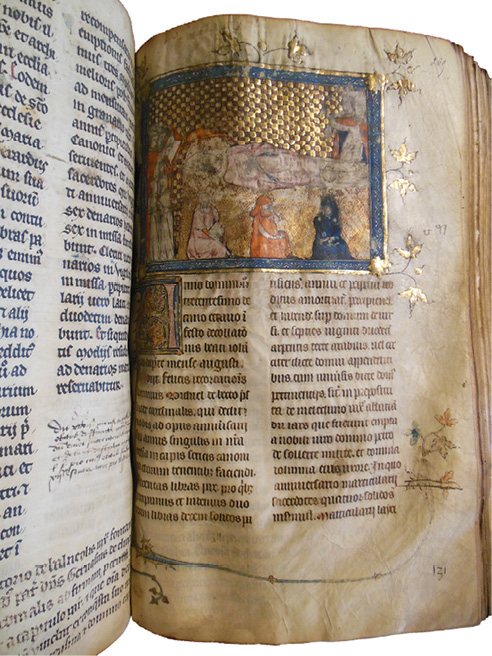

Both male and female monastics prayed for the dead, including laypeople, their own conventual brothers and sisters, their own families, and patrons who supplied them with material benefits in exchange for their prayers. All of this spiritual economy had to be recorded in necrologies, such as one owned and probably written by the Tertiaries of the Convent of St Lucy in Amsterdam (Manchester, JRUL, Ms Dutch 10).3 The manuscript contains two main texts: Usuard’s Martyrology, an account of lives of the saints organized around the calendar, beginning with the Feast of the Circumcision on the first day of January (fols 1r–102r); and a necrology in the form of a perpetual calendar with extra-large spaces, so that the deaths of sisters and patrons could be recorded (fols 102v–114r; Fig. 170).4 In this second section, while the standard feast days are written either in black or red ink in a neat textualis by a single scribe, the names of the recently dead are written in a variety of scripts, often with their year of death.

Fig. 170 Folio in a manuscript owned by the tertiaries of the Convent of St Lucy in Amsterdam, with an obituary calendar for the first half of February (Sprockelmaent). MJRUL, Ms Dutch 10, fol. 103v

Filling in the blanks of the calendar, a cumulative task fulfilled by numerous hands over time, requires a particular form of enduring interaction; in this way, it is not dissimilar from the accumulated abrasion of an image by multiple people. Scores of scribes left their marks in the book and co-created its content. Nuns and religious women (such as Franciscan tertiaries) prayed for deceased members of their communities, as well as for their parents and the donors to their religious houses on the anniversaries of their deaths. To use the manuscript, the sisters of St Lucy would have read the relevant saint’s vita from the first part of the manuscript, and then turned to the necrology in the second part to remember those who had died on that day. Sometimes such books were kept on the altar, so that the names could be mentioned as Masses were said in their honor on the anniversaries of their deaths.

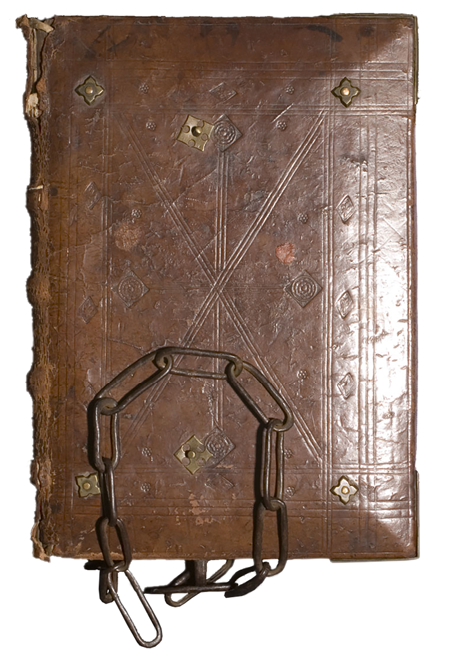

Fig. 171 Chained binding of the necrology of the canonesses regular of St Vitus in Elten. Eastern Netherlands, fifteenth century (after 1453). ’s-Heerenberg, The Netherlands, Collection Dr. J. H. van Heek, Huis Bergh Foundation, Ms. 31

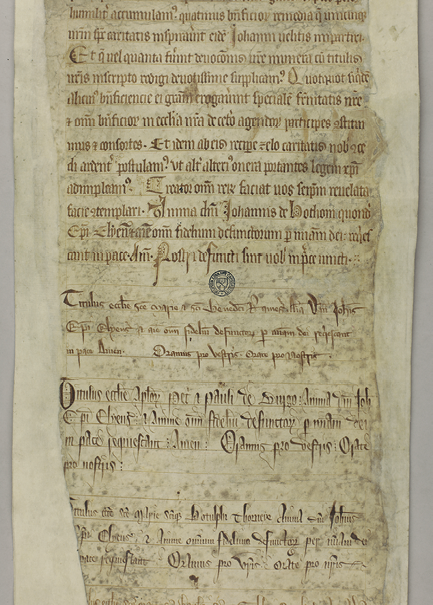

Necrologies often had special forms of handling built into them, and one example, for a different female convent, had to be kept on the altar, because it was chained to it (‘s-Heerenberg, Huisberghe, Ms. 31; Fig. 171). This necrological codex was begun around 1453 in Elten (on the modern-day Dutch-German border) for the canonesses regular of St Vitus. Its original binding consists of fifteenth-century tooled leather over boards, and a chain that was used to secure it within the monastery, so that it could be visible and in a public space, not secreted away in a book cupboard. As a necrology, it would have been used daily.

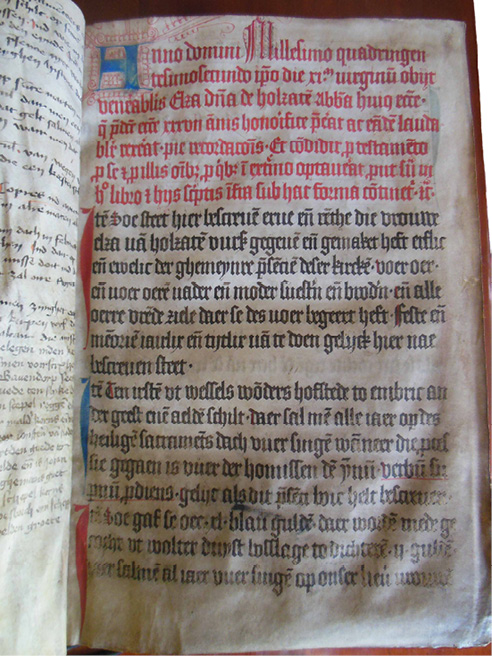

Fig. 172 Testament of Abbess Elza, Lady of Holzaten, in the necrology of the canonesses regular of St Vitus in Elten. Eastern Netherlands, fifteenth century (after 1453). ’s-Heerenberg, The Netherlands, Collection Dr. J. H. van Heek, Huis Bergh Foundation, Ms. 31, fol. 2r

The original campaign of work begins with an explanation of its contents on fol. 2r (Fig. 172). Some of the language in the book is in Latin, which lends it gravity, and some in Middle Dutch, heavily tinged with Germanic features typical of the Duchy of Cleves, where Elten was located. (The text begins on fol. 2r and is transcribed and translated in Appendix 6.) The text specifies the actions and rituals that must be performed in memory of the deceased Abbess Elza, Lady of Holzaten, following her death in 1402. As the text specifies:

- Lady Elza established a hereditary and perpetual endowment for the maintenance of the church, so that she and her family would be celebrated with annual feasts and memorials.

- She gave money to Wessel’s farmstead in Embric (Emmerich) and requested that on the feast day of the Holy Sacrament each year, the hymn Verbum supernum prodiens be sung before the procession and the homily.

- She bequeathed 40 “blue” guilders, with which a yield of two guilders per year is to be used to sing the hymn Ave maris stella on Candlemas after the procession and before the Mass.

- She donated two hundred Rhenish guilders, invested in Johannes’s estate at Woirt in Hamersche and another small property in Veele. The income from these is to finance the singing of the Mass in honor of the Holy Cross every Friday, with proceeds distributed among the nuns and priests participating, in addition to two sextons and the schoolmaster.

- Lady Elza provided property in Beke to Master Werner Boeskale’s prebendary. In exchange, prayers for her soul are to be said each Sunday at vespers. If Master Werner and his descendants fail to pay for the prayers, the property will be transferred to the nuns and priests.

- She gifted a portion of a felling forest to the altar of Saint Urban, with the requirement that the vicar pray for her and her family’s souls during Mass.

- She left two properties, in Velthusen and Lobede, to the nuns and priests for holding two weekly memorial services in her and her family’s honor, with provisions determined annually by the output of these properties.

- On her anniversary, following the Feast of the Eleven Thousand Virgins, specific rituals involving candles and offerings were to be conducted at her grave.

- Land rent from the Velthusen property was to be collected every eight years and distributed annually to religious participants, excluding those who neglected their duties.

- She gave small properties in Lobric to the canons, with the condition that one canon recite the Miserere plus another prayer at her grave daily. If neglected, the properties revert to the nuns and priests for the continuation of the prayers, and the canons would lose their rights to the property.

This will clearly expresses Lady Elza’s wishes for the ongoing remembrance of herself and her family, as well as the financial support for religious services and the upkeep of the church. The opening of the manuscript therefore presents the reader with the deeds of the pious abbess who spent her entire working life in the service of the monastery where the book was chained. The abbess donated money for the church’s upkeep. The text reminds the reader that she made these donations with the expectation of a counter-gift, namely that prayers would be said for her soul and for the souls of her family and friends. Although the abbess died in 1402, this manuscript was not written until well after her death in the 1460s, in a situation similar to the construction of the mortuary rolls discussed above: it is not the deceased, but her survivors, who care for her soul, which is tantamount to maintaining her memory.

Maintaining her memory would not occur if the list of deeds, promises, and arrangements were kept in a dark archive. Two structural facts prevented this from being the case. First, the manuscript was to be physically chained in a semi-public place, not in an archive. Second, the will of Lady Elza is bound together with a necrology (similar to that of the Tertiaries of the Convent of St Lucy in Amsterdam), which was in constant use, as testified by the layers of additions it received until 1772. Those who wanted to keep Lady Elza’s memory alive (and continue enjoying the rents on the parcels of land she had negotiated) stitched her will to the beginning of a book that they knew would be in use for centuries to come, and then they chained it to an accessible place, thereby ensuring its centrality in the social life of the convent. Members of groups that rely on survivors to pray for their souls use a chain—either physical metal links, or stitched/glued sheets—to create a chain of memory that will stretch into the future. Stitches, chains, laces, and glues to preserve one’s memory for the future.

Another book form—the mortuary roll—circulated from one religious house to the next to announce the death of a bishop, abbot, abbess, or other important religious leader. For this reason, church records sometimes refer to these rolls as circulars. This chapter will look at three surviving examples to examine how such manuscripts were handled and how they fostered relationships between religious communities. Mortuary rolls are similar to nuns’ professional briefs in their collective production and public function. Like nuns’ professional briefs, some of their elements are highly conventional, and other elements necessarily personalized. Both are forms unique to conventual settings. While a nun constructed her professional brief at the beginning of her enclosure, an abbess’s successor would organize the construction of a mortuary roll after her death. The latter object is both more intricate and more public. It required a particular kind of handling that could be characterized as diachronically social.

The efficacy of the mortuary roll was predicated upon dozens or hundreds of people handling it and making their own mark on it. This book form calls into question basic facts about medieval manuscripts: who is the producer and who the recipient? Who is the scribe and who is the reader? What is appropriate: a display script or a book hand? When can a manuscript be considered finished?5 These questions about the physical book arise in the context of the memorial culture, especially strong among late medieval religious.

I. A Benedictine abbess

Above we encountered the Abbey at Forest (Forêt, Vorst), a Benedictine priory for women, which administered the confraternity of St Sebastian in Linkebeek. When their abbess Elisabeth ’sConincs died in 1458 after having been in post since 1431, a written notice was dispatched to all of the religious institutions in the region to announce her death. Representatives from each religious house along the way appended a standardized promise to pray for the departed abbess in exchange for reciprocal prayers. The parchment membranes were rolled on a wooden spindle and the object may have originally been safeguarded in a box or bag (Fig. 173). Despite the limited number of surviving mortuary rolls, thousands were produced in Northern Europe and the British Isles from the ninth through the fifteenth centuries. Extant rolls are often preserved in archives and churches rather than in museums or libraries and have therefore received short shrift by historians of art and culture, since they followed a different route of historic preservation.6

Fig. 173 Top of the mortuary roll of abbess Elisabeth ’sConincs, with spindle. Southern Netherlands, 1458. MJRUL, Ms. Lat. 114.

Cumulative construction

Mortuary rolls contain two mandatory components: an encyclical, or letter authored by a representative of the house of the deceased, introducing the roll bearer, describing the deceased person’s deeds, giving her death date, and soliciting prayers; and tituli, which affirm those requests. These are promises of prayer offered by the institutions that sequentially received the mortuary roll. Many mortuary rolls also incorporated a third component: a depiction of the deceased. The roll bearer was a particular kind of messenger—known variously in accounts as a brevigerulus, brevetarius, rotulifer, or rolliger—tasked with carrying the mortuary roll from one religious house to the next in order to announce the death and solicit prayers for the soul of the deceased. For Elisabeth ’sConincs’s roll, the brevigerulus was Johannes Leonis, his name given at the end of the encyclical. He specialized in this niche service, and when he finished collecting the tituli for Elisabeth ’sConincs, he would have sought another similar gig. Given that deaths of abbots, abbesses, and other esteemed monastery members were announced this way, an efficient brevigerulus like Johannes Leonis would have had ample work.

He set off to collect tituli very soon after the abbess died in 1458. Each institution inscribed its titulus, typically filling two to ten lines, at the end of the roll. If there was insufficient space, the brevigerulus stitched on an additional membrane. As Stacy Boldrick has convincingly shown, Johannes had neither the frontispiece nor the illuminated encyclical in roll form when he set off to visit all of the churches, hermitages, and monasteries in the region. Rather, he probably carried a version of the encyclical in the form of a single sheet with a seal, which he could have brandished at each port of call along his itinerary in the Dutch-speaking region.

Up to four times a day for nearly a year, Johannes presented this letter of introduction:

We earnestly beseech you that you may wish to receive the bearer of the present roll, favorably and kindly, namely Johannes Leonis, when he comes, so that we may reciprocate our gratitude to you and yours in similar circumstances.7

This sheet no longer survives. While he was touring, the encyclical now attached to the roll was being professionally copied and illuminated so that it could become membrane 2 of MJRUL Lat. 114. This implies that the religious houses were not the audience for the lavish decoration of Elisabeth ’sConincs’s roll.

During his travels from 6 September 1458 to 8 July 1459, Johannes collected 390 tituli, but he also amassed reciprocal obligations for prayer that the Benedictine nuns at Forest were bound to honor. In essence, those institutions in a fraternal relationship with Forest (mainly other Benedictine houses) consented to pray for the abbess’s soul on the condition that the Forest nuns pray for theirs. These mutual obligations are itemized as Mass counts and Psalter recitations. The roll served as a tangible record of this spiritual reciprocity.

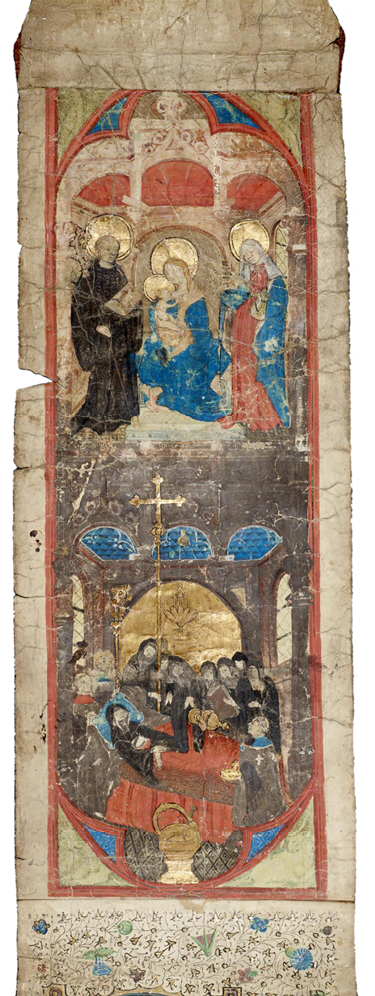

Fig. 174 Miniature with two pictorial registers, the upper one depicting the enthroned Virgin and Child flanked by Sts Benedict and Elisabeth, and the lower one depicting the death of abbess Elisabeth ’sConincs. Southern Netherlands, 1458. MJRUL, Ms. Lat. 114

Many mortuary rolls, including that of Elisabeth ’sConincs, begin with a frontispiece showing an image of the deceased. In her roll, the frontispiece occupies the first membrane (Fig. 174); the encyclical, the second membrane (Fig. 175); and the tituli, the subsequent membranes (Fig. 176). Boldrick revealed through her research that a mere ten days before the first anniversary of the abbess’s death, Johannes Leonis returned to the abbey at Forest with 17 membranes teeming with tituli.8 These tituli (now membranes 3–19) were then affixed to the illuminated encyclical (membrane 2) and to the ornate frontispiece (membrane 1), which a professional scribe and illuminator had had nearly a year to craft. Given this order of operations, those inscribing the tituli would not have seen the frontispiece. That was only readied in time for the ritual on the anniversary of the abbess’s death, in the church in Forest, which took place on 19 July 1459. Those present at the ceremony would have seen the final roll, filling 19 membranes that stretched 1296 centimeters in length.

Fig. 175 Encyclical of the mortuary roll of abbess Elisabeth ’sConincs, with an illuminated initial. Southern Netherlands, 1458. MJRUL, Ms. Lat. 114.

Fig. 176 Selection of tituli, written on unlined parchment forming part of the mortuary roll of abbess Elisabeth ’sConincs. Southern Netherlands, 1458. Manchester, Rylands Library, Ms. Lat. 114.

Even viewing the roll from a distance, the lengthy object would have been impressive. One could see, even from about three meters away, that the roll comprised the scribal contributions of hundreds of different people. And that was the point of the roll: as opposed to a codex, where only one opening is visible at a time, the entire roll can be comprehended at once. Which is to say that the meaning was consistent with the form of the message: a cumulatively made object implies community, and the size and grandeur of that community is commensurate with the astounding length of the object. By contributing to the writing, each house formed the cumulative first viewers and handlers of the roll.

Although the scribes of all the tituli would not have seen the illuminated front matter that was eventually sewn to the top of the roll, they would have seen Johannes’s travelling encyclical, as well as the tituli from the other houses. These tituli are written in a variety of scripts, including textualis, hybrida, and bookhands, often without ruling. While the script and ruling of the tituli were rather higgledy-piggledy, their words were quite formulaic, as the scribes would have modeled their respective texts on what was visible before them, unfurling it to see what company their own titulus was about to keep. Formalities around death were scripted.

The scribes of these tituli were both the producers and the users of the roll. With every use, they added specific marks, thereby co-producing the text with the members of the other houses visited, past and future. Like the oaths of profession, the texts themselves were not particularly original, but rather comprised copies with variations. Each scribe who added to it would have handled the roll in a performative way while the document grew in length.

The mortuary roll of the abbess of Forest created a permanent record of mutual obligations with neighboring institutions within the spiritual economy: those 390 institutions handled the object in order to add their hand-inscribed pledges. Moreover, the object would have been handled with particular techniques of the body, to use Marcel Mauss’s term, wherein the unusual roll format must have played a role: it required a particular set of gestures while presenting a spectacle for those present at the abbess’s anniversary Mass(es). The size of the gestures used to display the role were commensurate with the abbess’s reputation.

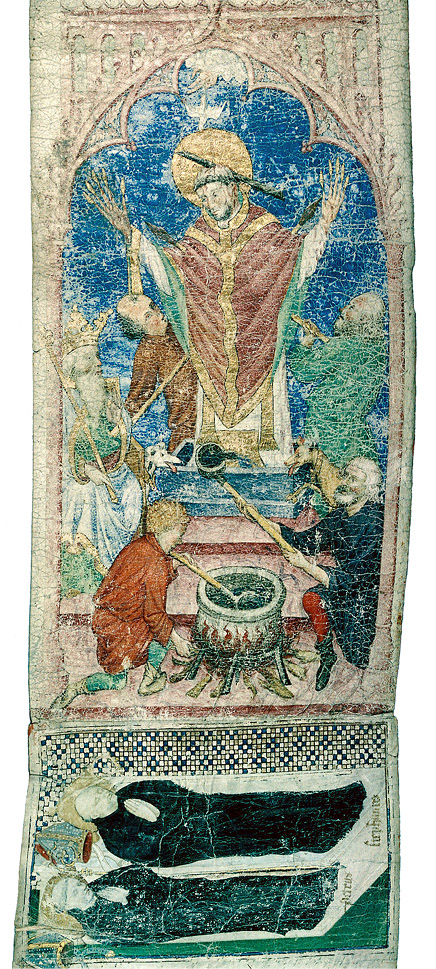

Imagery on the roll

The frontispiece at top of the roll has a miniature arranged in two registers to take advantage of the tall, thin format necessitated by the constraining, narrow form. These registers set out a clear hierarchy, with the enthroned Virgin and Child flanked by Sts Benedict and Elisabeth at the top, and the death of Elisabeth ’sConincs at the bottom. The Virgin Mary provides a model for the abbess, who will, with the help of the prayers offered by the neighboring institutions, rise up to the upper echelons to meet Mary. The promised prayers in the tituli will help ensure that the abbess passes from the lower, earthly realm to the upper heavenly one.9

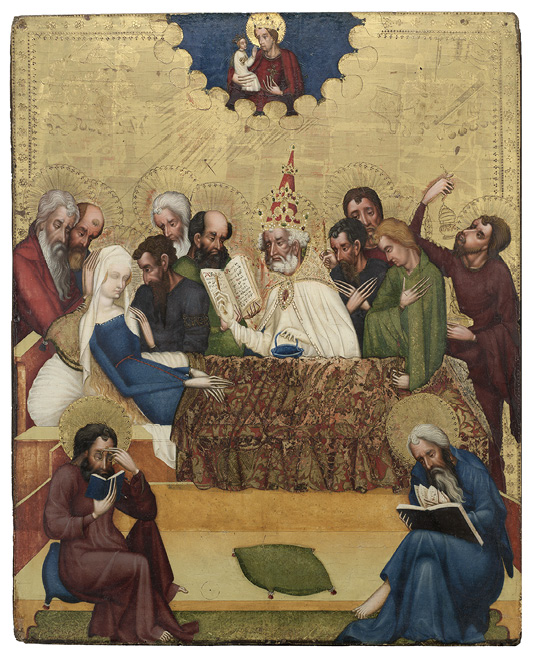

The lower scene, set in an ecclesiastical interior, recalls images depicting the death of the Virgin, as in a panel made ca. 1400 for a convent in central Europe (Fig. 177). In the roll, Elisabeth ’sConincs occupies the position of the Virgin Mary in the scene, while her Benedictine nuns, who pray over her dying body and read from large tomes, take on the roles of the Apostles. A priest swinging a censor adopts the role of St Peter in the panel, while one of the nuns, reading from a large volume, becomes the mediator between the book and the breath.

Fig. 177 Master of Heiligenkreuz (Bohemian?), Death of the Virgin, ca. 1400–1401. Tempera and oil with gold on panel. Cleveland Museum of Art

Given the nature of the promises of mutual prayer, the mortuary roll functions as a binding legal document, cementing the relationships of all the 390 institutions promising prayers, and further stipulating mutual prayer bonds among the houses in Forest’s confraternity. The format of the manuscript—a roll rather than a codex—may underscore this function, considering the connotation that rolls had with legal authority.10 With this in mind, one could read other aspects of this imagery in terms of an authoritative function. Specifically, the spandrels in the corners contain the symbols for the four Evangelists: these convey the presence of the Gospel writers and their respective Gospels, which ripens the atmosphere so that vows and other sacred acts can take place in the presence of the divine.

The signs of wear on the roll reveal aspects of how it was handled after its assembly, once it was mounted into its spindle. First, the top was more subject to wear than the bottom, since the top has to be handled every time the roll was opened, whereas the bottom only had to be handled by those who unfurled the entire item. The very top of the miniature was trimmed away, probably because it was so frazzled with handling. The miniature has been heavily damaged, with numerous horizontal cracks caused by rolling and unrolling it. It is also possible that the image has incurred some damage from holy water, flung from a golden bucket with an asperge like the one pictured in the foreground. One can imagine that it was partially unrolled, to reveal the first membrane with the large illumination, and displayed on the altar during the Mass said for the abbess. Exposed, it would have been vulnerable to holy water.

The faces of the figures in the deathbed scene have also been severely damaged, but the cause of this damage is ambiguous. The faces of most of the nuns have been damaged, but this may be due to a horizontal stroke inadvertently made across the sheet, rather than targeted touching. However, the face of Elisabeth ’sConincs is below the isocephalic band of nuns, and the damage to her face may have instead been targeted. Her face, and the blue pillow that frames it, have been abraded.

In thinking about how the roll may have been used, one could compare it with how the Grand Obituary of Notre Dame was used (according to my analysis in Volume 1). There I suggested that the patterns of targeted wear on the images of the deceased may have been incurred during anniversary Masses, when those in the living memory of the deceased would have touched the image as a tangible gesture of remembrance. For example, the image of the funeral of Cardinal Michel du Bec (Paris, BnF, Ms. Lat. 5185CC, fol. 265r; Fig. 178) has been repeatedly and systematically touched. The book’s users particularly targeted the face and body of the cardinal.

Fig. 178 Funeral of Cardinal Michel du Bec, on an added folio in the Grand Obituary, entry for August 22, 1318. Paris, BnF, Ms. lat. 5185 CC, fol. 265r

It is possible that the top of the roll was displayed on an altar in Forest during the annual Masses said on the anniversary of Elisabeth ’sConincs’s death. Some might have touched the image of her face, or the faces of the other nuns. Some might have touched the image of the Virgin and Child in the initial of the encyclical, for this has also been abraded and crumpled. The ceremonies would have presented moments to reflect on the state of their former abbess’s soul, to remember her funeral, and to help push her from the lower register to the higher eschatological register, to join Mary, St Benedict, and her name saint, Elizabeth. During these ceremonies, holy water and wax may have spilled on the roll. The mortuary roll was a band of text and imagery that literally unfurled and tied communities together, spatially and temporally, connecting the past, present, and future.

II. Remembering John Hotham, bishop of Ely

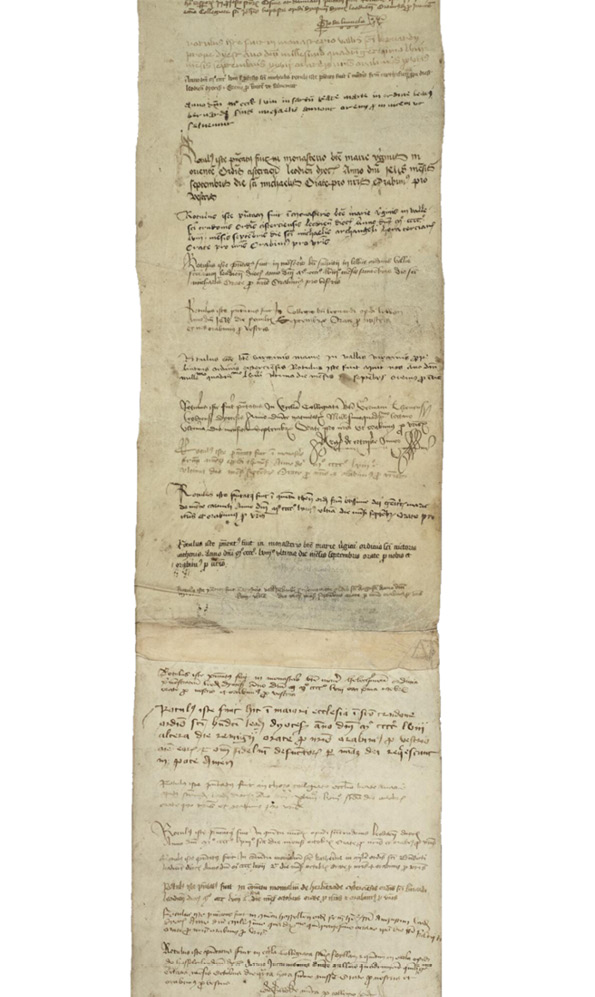

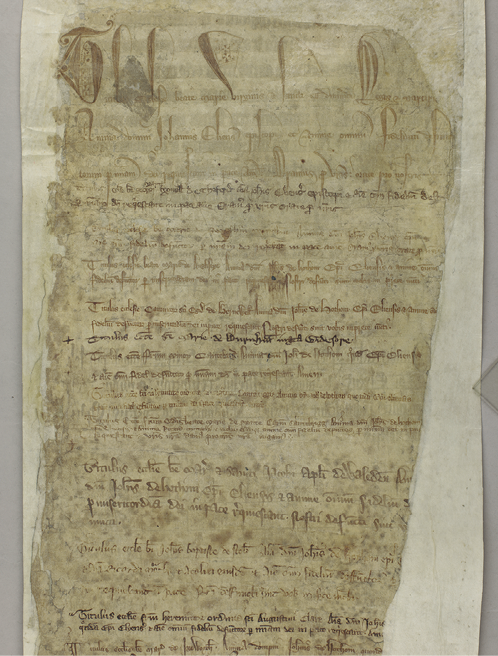

When John Hotham, the bishop of Ely, breathed his last on 7 Jan 1337, his surviving brethren wrote an encyclical to announce his death and request prayers for the repose of his soul (Canterbury, Cathedral Archives, ChAnt E 191).11 As was the tradition, the mortuary roll comprises multiple parchment membranes, stitched end-to-end. Unlike Elisabeth ’sConincs’s roll, this one has only three membranes, and it has received heavy-handed repairs (Fig. 179). The brevigerulus of John Hotham’s roll was neither as talented nor as conscientious as Johannes Leonis: he did not add more sheets when the third membrane was full, and instead the subscribers had to turn the roll over and write on the back.

Although mortuary rolls, as we saw in the previous section, always have a eulogy and a series of tituli, and often have an image depicting the deceased, the forms for these individual components could vary, and the three examples examined in this chapter each present the deceased differently. For John Hotham’s roll, the illuminator depicted the subject not as a corpse on a bier (as with the mortuary images in the Grand Obituary of Notre Dame, as discussed in Volume 1), but as a commanding figure in the prime of life. What passes for a “portrait” of John Hotham fills the initial U: a rather generalized man in bishop’s garb, making the sign of benediction. The image is damaged, but it is not clear whether it was touched specifically, or whether the abrasion is an extension of the overall damage the roll incurred.

Fig. 179 Composite digital image showing the entire recto of the mortuary roll of John Hotham, and detail showing the historiated initial U framing the image of the bishop. Ely, 1337. Canterbury, Cathedral Archives, ChAnt E

The initial marks the beginning of a eulogy, an essential (and usually second) component of a mortuary roll. John de Crauden (or John Crauden), prior of Ely Cathedral Priory, who wrote the encomium for John Hotham, had enough praise for the bishop to fill two membranes with 1180 words. Crauden has remembered the bishop in terms that are both intimate and role-specific, offering a spiritual biography of the bishop with a list of his virtues. The surviving John wrote of the deceased John: “He was angelic in the church, splendid in the court, bountiful at the table, strict in the chapter, reproving, admonishing, and beseeching subjects with all patience and teaching; devout to his superiors, gracious to his juniors, affable and kind to all, greatly circumspect in spiritual and temporal matters.” (See Appendix 7 for a full transcription and translation.)

The audience for this eulogy was both the current and future denizens of Ely Cathedral Priory, as well as members of the religious houses elsewhere in East Anglia who may not have known John Hotham personally but were agreeing nonetheless to pray for him. As it reached these far-flung audiences, the content of the third membrane grew, although not on the scale of Elisabeth ’sConincs’s mortuary roll: to wit, John Hotham’s roll preserves only 24 tituli, each consisting of the name of the house and its order, a prayer for the bishop, and a request for prayers in return.

Because mortuary rolls have a phased genesis, they can reveal medieval itineraries and aspects of medieval travel. Lynda Rollason studied another mortuary roll—the Ebchester-Burnby roll produced by Durham Cathedral Priory in Durham—to do just that. Specifically, the tituli in the Durham roll list some 623 names of the institutions the brevigerulus visited, and these can be mapped to understand the trajectory of the roll and its carrier.12 At over 11 meters long, the Ebchester-Burnby roll lists hundreds of stops along a journey lasting several months. John Hotham’s roll, likewise, presents place names, and its trajectory can be reconstructed, although its journey and its physical length are at a more modest scale, and its 24 tituli are not dated (Fig. 180).

Fig. 180 Beginning of the tituli from the mortuary roll of John Hotham. Ely, 1337. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, ChAnt E, membrane 3 recto

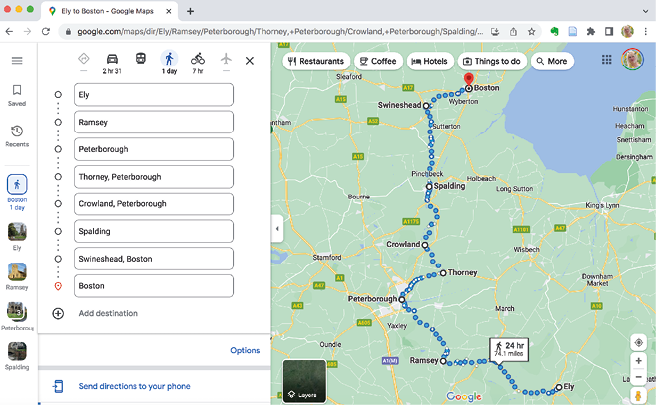

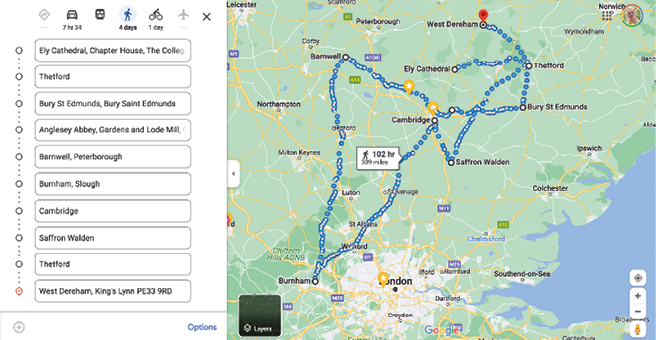

The first group of tituli on John’s roll, inscribed on the recto, show that the brevigerulus set out to the north and walked (or rode on horseback) for several days. Departing from Ely, he went first went to Ramsey and then continued northward to Peterborough, Thorney, Crowland, Spalding, and Swineshead, before arriving at Boston. A modern Google map of this journey indicates that it would have taken about 24 hours on foot (Fig. 181).

Fig. 181 Google map approximating the first journey of the brevigerulus, from

Ely to Boston.

John’s roll is opisthographic, meaning that it is inscribed on both recto and verso. The verso of the roll is more difficult to interpret, and the tituli less orderly (Fig. 182). The locations on the verso of the roll lie south of Ely, and he may have returned to Ely before continuing on this south-bound leg; however, when the places are mapped in order of appearance, they create an illogical route. If he actually followed the route as recorded on the sheet, his trajectory would have been a jumble, beginning with a jaunt to the east to Thetford, south to Bury St Edmunds, the richest monastery in East Anglia, and then west to Thetford (again), then west to the Priory of Swaffham Bulbeck, a Benedictine nunnery, then south-west for 13 on-foot hours to the Augustinian priory of Anglesey, followed by another thirteen-hour walk, north-west, to Barnwell to seek prayers from the Augustinian canons of St Giles. After a 25-hour walk due south to the Church of Saint Mary of Burnham near Windsor, he would have returned to Cambridge, and then revisited Thetford, before ending with West Dereham Abbey in Norfolk (Fig. 183). Clearly, this route would be inefficient. The sequence of tituli on the roll may not be the same as the sequence in which the brevigerulus visited them, since several of the tituli appear to be squeezed into gaps.

Fig. 182 Tituli on the mortuary roll of John Hotham beginning with Bury St Edmunds. England, ca. 1337. Canterbury Cathedral Archives, ChAnt E, membrane 3 verso

Fig. 183 Google map of the locations listed on the verso of the roll, from Ely to Westerham

To explain this state of affairs, I submit the following: while the rectos of all three membranes of the roll were ruled by the original scribe who then carefully copied the eulogy and left some space at the bottom of the third membrane for the tituli, the verso of the roll was not systematically ruled, and it was filled in unsystematically. The brevigerulus should not have allowed representatives from the religious houses to write on the verso; instead, he should have stitched—or commissioned a parchmentier to stitch—a fourth membrane to the roll, but he failed to do this. As a result, scribes from the institutions south of Ely turned the roll over and wrote on the bottom of the roll. When it came time for Bury St Edmunds to add its titulus, its scribe moved further toward the head of the roll, where he found sufficient space to add enormous, florid, and performative script. When there was little space left, the other houses on the verso abbreviated their tituli, sometimes using only a single line of text.

These facts lead to a few different kinds of analysis. First, the brevigerulus was interested in both the quantity and quality of the tituli he assembled. He picked the low-hanging fruit around East Anglia and nearly went door-to-door in Thetford. But he also obtained the promise of prayers from the Church of Saint Mary of Burnham near Windsor, not far from London. Perhaps he did not travel there at all, but rather encountered a representative from this church during his travels. In that case, he opportunistically obtained that traveler’s textual contribution. If we assume that he did not travel south 110 miles to Burnham, and that he only visited Thetford once, then his route looks much more rational (Fig. 184).

Fig. 184 Google map of the locations listed on the verso of the roll, from Ely to Westerham, but rationalized to omit Burnham

The roll’s intended purpose was to convey the promised prayers of far-flung religious houses back to the home institution of the deceased, with the ultimate purpose of strengthening shared bonds among the various churches and monasteries. However, the disparity in the size and boldness of the handwriting in the various tituli points to a secondary function for the roll. Namely, the houses jockeyed to show their dominance within the East Anglian network. The monks at Bury St Edmunds, the famous and wealthy Benedictine monastery that boasted the relics of St Edmund, reflected their self-importance in the size, style, and placement of their script.

Even though the bottom of the roll is damaged, it is unlikely that it was originally longer — since, as the analysis above shows — the tituli were crammed in and abbreviated because of lack of space. This presents an interesting state of affairs: writers of the later tituli had to handle the roll, study it, see others’ solutions to the space problem, and make adjustments to their contributions so that they would fit properly. Doing so required more interaction with the previous scribes’ tituli. All of the scribes had to handle the roll intensely, and to make their respective marks on the lower part of the final (third) membrane. This roll already has always had three membranes; unlike the abbess’s roll, the image was not added as a separate membrane to the top. And also unlike the abbess’s roll, more sheets were not added to the bottom to accommodate tituli. This means that each of the 24 signatories has handled the roll, seen the image of the bishop, delighted in the fine calligraphy of the encomium, and measured up how he (or she) would make a mark for posterity.

III. Retouching, reusing, and restitching elements

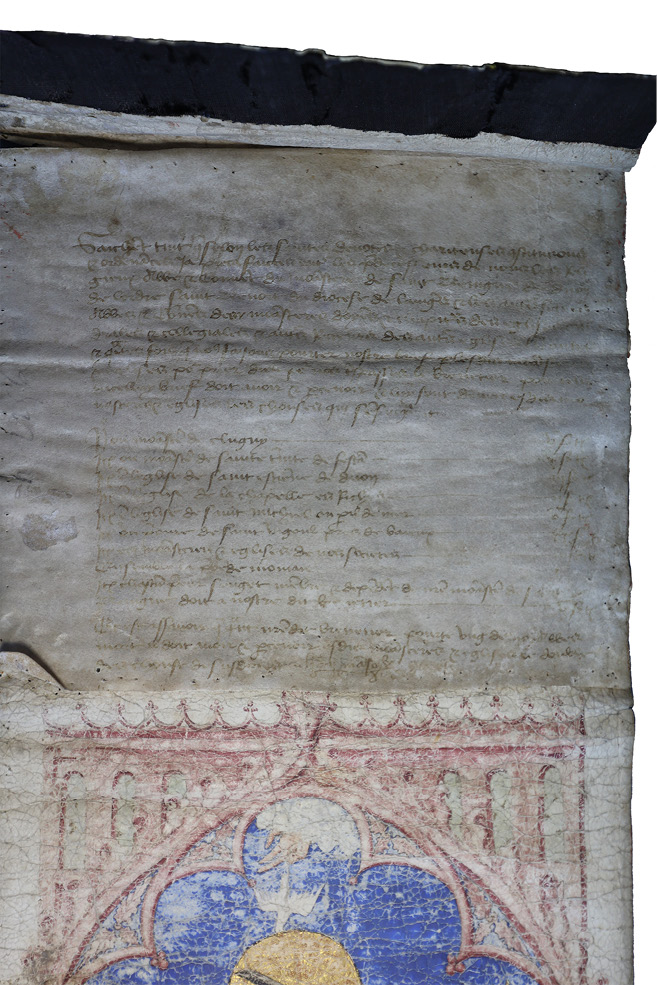

A mortuary roll made to commemorate abbots from the Abbey of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon reveals another set of handling practices (Fig. 185).13 The obverse of the roll collects prayers dated 1439–1441 for the abbots Etienne de La Feuillé (1430–1434) and Pierre Brenot (1435–1438) and therefore circulated shortly after the death of the latter. The roll has a two-tiered frontispiece that depicts the martyrdom of St Bénigne in the upper register and the two abbots in the lower. As was the convention, the dead are laid out on something that has features of both a deathbed and a monumental tomb. Close inspection reveals that the imagery was pieced together from several campaigns of work, with the martyrdom scene having little in common stylistically with the depiction of the recumbent abbots, and the text sections having surprising origins.

Fig. 185 Two painted membranes in the mortuary roll circulated in 1439–1441 for abbots Etienne de La Feuillé (1430–1434) and Pierre Brenot (1435–1438) of the Abbey of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon. Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2256

In thinking about how the Dijon roll was assembled, it helps to consider Rollason’s analysis of the Ebchester-Burnby roll, which underscores a practical approach to the physical handling of mortuary rolls by medieval scribes and ecclesiastical users.14 She points out that elements of the rolls, particularly the pictorial membranes, were carefully disassembled and reassembled, indicating a tactile interaction that went beyond mere writing or reading. The frequent restitching and adaptation of these materials for reuse demonstrate a tangible, hands-on aspect of monastic work, where the reconfiguration of earlier rolls into new ones was a common practice, highlighting a resourceful and physical engagement with these objects. Rollason suggests that medieval mortuary rolls, like the Ebchester-Burnby roll, often survived in fragmented forms, their components repurposed for new uses. The rolls’ pictorial and textual elements, seen as creative investments, were sometimes salvaged and incorporated into later works, as indicated by recurring stitch holes and stylistic discrepancies. This practice reflects a broader pattern of resourcefulness within monastic scriptoria, where the recycling of materials, such as the reapplication of a picture membrane from an older roll for new requests for prayers, was not uncommon.

The physical substrates of all mortuary rolls (with a few exceptions such as John Hotham’s, discussed above) are built over time. The Dijon roll is unusual in that not only are several of the membranes anopisthographic, but that the text on the versos of membranes 2 and 3 (which are the two membranes containing the illuminations) concerns the death of an earlier abbot from the Abbey of Bénigne de Dijon.15 The tituli on the backs of these membranes are dated from 1420–1422; therefore, these parts of the roll circulated during the abbacy of Jean V de la Marche (who served from September 18, 1417, to September 22, 1421). These tituli must therefore concern his predecessor, Alexander of Montaigu (1379–1417). Because these tituli from the 1420s are inscribed on the backs of the images, we can deduce that the images circulated with the growing roll at that time.

Fig. 186 Two recumbent abbots, begun before 1420, with additions ca. 1439. Mortuary roll circulated in 1439–1441 for abbots Etienne de La Feuillé (1430–1434) and Pierre Brenot (1435–1438) of the Abbey of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon. Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2256

The membranes that circulated in the 1420s to remember Jean V de la Marche contain two distinct images on separate membranes. One of these depicts a pair of recumbent abbots, with the two figures labelled at their feet: Stephanus and Petrus (Fig. 186). The image has in fact been repurposed to depict two abbots, when originally, it had depicted only one: the one now labeled Stephanus (i.e., Etienne de La Feuillé). When it circulated in the 1420s, this figure was apparently understood to represent Jean V de la Marche. Although previous art historians have studied this roll, none has pointed out that the illuminator who repurposed the membrane in 1439 added a second dead abbot to the picture and called the fresh figure Pierre Brenot. Pierre’s black-clad body was painted atop the white ground that formed the marble plinth, which a single abbot had previously occupied alone. To change the image, the second artist extended the plinth, and—like M.C. Escher—turned the vertical surface of the plinth’s side to a horizontal one. Onto this ambiguous platform, the painter has squeezed in Pierre Brenot’s narrowed body and then used the abbot’s miter to hide the awkward corner of the composition. Adding the second body prompted the painter to disambiguate their identities by labelling them Stephanus and Petrus. The stratigraphy of the image explains why Petrus looks more damaged than Stephanus: because Petrus was painted over a white marble ground, the white lead paint is seeping through his black-clad body.

In fact, the abbot in the superior position cycled through multiple identities. The figure may have originally bben meant to depict an even earlier abbot than Jean V de la Marche, as the blue and gold diaper background typifies an era earlierthan the 1420s. Alexander of Montaigu (1379–1417) may have commissioned the image (and the core of the roll) around 1379 to commemorate his predecessor. Successive abbots then used the “portrait” of the abbot to memorialize their respective predecessors, until Pierre Brenot’s successor turned parts of the roll into a double memorial, one that would collect prayers for both Etienne de La Feuillé (1430–1434) and Pierre Brenot (1435–1438). That enterprising and corner-cutting abbot was Hugo III de Mosson, who was elected head of the Abbey of St Bénigne on January 14, 1439. Shortly after his election, he sent the roll on its journey to collect tituli that would fill 824 cm of parchment. He was able to act quickly because he repurposed as much of the old roll as he could, namely, the 126 cm of the roll’s total length that contained the painstaking images.

Not only did Hugo III de Mosson repurpose the older roll for its images, but he also adapted the older encyclical, which begins:

Universis Sancte Matris Ecclesie fidelibus illis precipue qui sub regulari habitu Domino famulantur frater Hugo permissione divina abbas humilis et meus conventus ecclesie Sancti Benigni Divionensis ordinis sancti Benedicti Lingonensis dyocesis salutem cum augmento continuo celestium graciarum…16

[To all faithful of the Holy Mother Church, especially those who serve the Lord under a regular habit, brother Hugo by divine permission, humble abbot, and my convent of the Church of St Bénigne of Dijon of the order of Saint Benedict of the diocese of Langres, greetings with an increase of continuous heavenly graces…]. [emphasis mine]

Fig. 187 The name Hugo written over an erasure. Encyclical from the mortuary roll of the Abbey of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon, circulated in 1439–1441. Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2256 [image made from a microfilm]

The word “Hugo” is written over an erasure. To update the found text, Hugo has simply scraped out his predecessor’s name and inscribed his own instead (Fig. 187). The audiences for this encyclical—representatives from religious houses across Burgundy and beyond—would have heard from the brevigerulus that Abbot Hugo was exhorting them to offer prayers for the dead of St Bénigne’s Abbey.

Fig. 188 Account of debts inscribed on the first membrane of the mortuary roll of the Abbey of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon, circulated in 1439–1441. Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2256

Hugo made his mark on the roll in another way, as well: he added a message to the very top of the roll, one titled “Debts owed by the visited churches to the brevigerulus” (Sommes dues par les eglises visitees au porte-rouleau; Fig. 188).17 In other words, each time the roll, which requests prayers for the deceased, was carried to these institutions, the brevigerulus was entitled to specific payments , as established by historical agreements. Cluny Abbey, for example, would owe 5 sols tournois, the Holy Trinity Monastery at Fécamp (in Normandy) would owe 10, Saint-Stephen of Dijon 3, the priory of Saint-Vigoul near Bayeux 20, the Church of Mont Saint-Michele, or “maritime peril,” 5, with additional monasteries and churches owing other amounts. Additionally, there was a prebend for those near death, and each subordinate institution of Saint-Bénigne’s monastery would owe 5 sols tournois. If the deceased were an abbot, the payment would be doubled. Hugo III de Mosson signed this opening section, which is the first item audience members would encounter. These dues reflect the roll’s function in mediating the spiritual—and financial—economy between monasteries, supporting prayer for the dead, sustaining religious community networks, and making known Hugo’s name across a wide swathe of France.

The sheet with Hugo’s price list also serves as a protective wrapping for the two images. Hugo’s name appears just above the martyrdom of St Bénigne. The image with St Bénigne did not co-originate with that depicting the recumbent abbots. The dramatic martyr’s image, made in a much brighter palette with no fussy diaper patterns, shows the saint withstanding multiple tortures. St Bénigne, who lived in the second century CE, was said to have Christianized the region around Dijon until he was persecuted and killed under the reign of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE). According to his hagiographers, he was beaten with beef tendons, bludgeoned on the head with a metal rod, thrown in jail with hungry dogs, and subjected to molten lead poured over his feet. In the image, Marcus Aurelius, with his crown and scepter, oversees these tortures.

The most visible of these tortures, however, appears at the saint’s hands: they have been stretched, so that the distal phalanges hover above the hand, connected to the middle phalanges by a thin peninsula of tortured skin (Fig. 189). Frozen in the orans position, his unnaturally elongated fingers stand boldly silhouetted against the blue background. His partially severed fingertips are the sensory organs for the sense of touch, the very digits one must apply with dexterity to unroll the eight-meter-long roll. It is impossible to empathize with the saint’s pain without becoming aware of one’s own hands and fingers. To unfurl this image is to cause the saint’s body, bones, and paint to crack even further. Even when the roll was new, its handlers realized that it needed to be protected, as a matter of conservation. Hugo III de Mosson died on February 22, 1468. If his successor circulated a mortuary roll for him, it has not survived. Hugo was the last in a series of abbots to redeploy the cracked and broken images of the dead abbot(s) and St Bénigne.

Fig. 189 Detail of Saint-Bénigne, on the mortuary roll of the Abbey of Saint-Bénigne in Dijon, circulated in 1439–1441. Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, Ms. 2256

Coda

In the mortuary rolls discussed in this chapter, each followed a different set of steps for its construction, which in turn were predicated on different forms of handling. For the mortuary roll of the Abbess of Forest, the various elements—prefatory image, encyclical, and tituli—each had a separate genesis and were stitched together later. John Hotham’s roll, on the other hand, was made as one unit and sent around to collect its tituli. This created a problem, because no extra membranes were stitched to the roll, and the surface of the verso, which should not have been inscribed, became a disorganized mess. In the Dijon abbots’ roll, the pictorial elements were made separately, recycled, adjusted, and reused, so that their current state represents their final context. The reassembly and reuse of the elements destabilizes the fixedness of the object, while also calling into question who the maker, user, and audience is. Their roles shift as they co-create the object.

Moreover, the size and style of the added tituli call into question whom or what a mortuary roll memorializes. On the mortuary roll of John Hotham, the scribe from Bury St Edmunds who dominated the dorse with his enormous ascenders was peacocking to the scribes down the road. Sure enough, 687 years later, we do indeed hold Bury St Edmunds more vividly in our collective memory than we do John Hotham. Like the prelectors of courtly literature, the scribes of tituli on mortuary rolls conducted performances in the moment but also diachronically.

There is a strong relationship between the kind of cumulative authorship of the mortuary rolls and the letters of profession discussed in Chapter 1. In both cases people are making marks on parchment as a form of speech act. This is a different form of writing from authorship and relies on producing formulaic words. In both cases, the operation of stitching enhances the meaning of the respective objects, since as a stitched unity the individual parts play a role that buttresses concepts such as historical continuity, widespread esteem, and institutional strength.

We can compare necrological codices, discussed earlier, with mortuary rolls. Whereas the necrology from the Franciscan convent of St Lucy stayed in the convent and recorded the deaths of many people, a mortuary roll, such as that of Elisabeth ’sConincs, travelled outside the conventual walls and only recorded the death of one person. Both objects have a memorial function, which is about ensuring that prayers be recited on behalf of the deceased. In the case of the necrology, the assurance is temporal: the Franciscan sisters of the future will continue to recite prayers on the death dates of those inscribed. In the case of the mortuary roll, the assurance is spatial and temporal: institutions from a broad geographical swath around the Benedictine convent will offer their prayers. In both cases, the objects only function when they are handled in specific ways. Like all manuscripts, they have to be opened and read to be used, but these manuscripts are special in that they also have to be cumulatively inscribed to make meaning. In both cases, the manuscript is collectively written and regularly used to organize memory as a social affair.

That each titulus in a mortuary roll is written in a different hand testifies to the willingness of these individuals, acting on behalf of their respective institutions, to pray for the subject. Each scribe leaves a clear sign of wear—a legible testimony—to his promise. In this way, the tituli are similar to the signs of the cross, “made with my own hand,” inscribed on the professions of obedience. They bear weight because the hand that has inscribed them is the extension of a speech act, a promise that strengthens invisible social ties.

The way that memorial books were made testifies to the collective forces they exerted, but so do the ways in which they were handled. The spindles at the cores of the mortuary rolls protected them (by forming a rigid support, and in some cases, a protective hilt), and they also orchestrated a particular set of gestures for someone who wanted to operate the book. The rolls imply a long table (perhaps an altar), multiple people, some ceremonious unfurling. When that unfurling takes place, what is exposed is not only the extraordinary length of the roll, which is commensurate with the number of prayers being recited for the deceased subject, but also the variety of scripts on display. Each script represents a voice in the collective agreement to pray for the deceased. The medium (of multiple hands) is very much the message to the roll’s future users. Whereas a codex can be opened at any folio, every inch of a roll has to be touched in order to see and read it. To read a column of text is to handle it.

In Lady Elza’s necrology, one more detail suggests the text was read: the blue initial A (for Anno domini) that opens her testament has been deliberately touched. In particular, the thick vertical of the letter bears the marks of multiple, indistinct fingerprints. These, I believe, were left by readers as a gesture to initiate reading, as I will argue in the next (and final) chapter.

1 Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Scolar Press, 1984).

2 Mathias Ubl has written convincingly that the presence of Mary and Elizabeth refers to the Magnificat, a joyous prayer read at vespers. See Mathias Ubl, “The Office of the Dead’: A New Interpretation of the Spes Nostra Painting,” Rijksmuseum Bulletin (January 2013), pp. 322–337. For a full bibliography and high-resolution images, see https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/researchand-library/early-netherlandish-paintings; J.P. Filedt Kok, “Meester van Spes Nostra. Vier kanunniken bij een graf,” in Vroege Hollanders. Schilderkunst van de late Middeleeuwen, F. Lammertse and J. Giltay (eds), exh. cat. Rotterdam (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2008), pp. 286–90.

3 Ker 1969–1992, III, p. 396. Fol. 115r: “Item dit boec is ghescreven int iaer ons heren m cccc ende lxxij ende hoert toe den susteren van sinte Lucien.”

4 The manuscript can be compared with HKB, Ms. 70 H 53, which is also a copy of Usuard’s Martyrology used as a convental necrology; this manuscript has penwork associated with Haarlem ca. 1460 and was also used by the convent of tertiaries dedicated to St Catherine’s in Haarlem. See Overgaauw (1993, pp. 446–450), which is the publication of his dissertation: E.A. Overgaauw Martyrologes manuscrits des anciens diocèses d’Utrecht et de Liège. Étude sur le développement de la diffusion du Martyrologe d’Usuard (Diss.) (University of Leiden, 1990).

5 For an overview of mortuary rolls, see Léopold Delisle, Rouleaux des morts du IXe au XVe siècle, recueillis et pub. pour la Société de l’histoire de France (Mme. Ve. J. Renouard, 1866), p. 485; at that time, the roll under discussion here was in Ashburnham Palace. It is now in the Rylands Library. Stacy Boldrick notes the slippage between maker and user in “An Encounter between Death and an Abbess: The Mortuary Roll of Elisabeth ’sConincs, Abbess of Forest (Manchester, John Rylands Library, Latin MS 114),” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 82(1) (2000), pp. 29–48, and ibid, “Speculations on the Visibility and Display of a Mortuary Roll,” in Continuous Page, Scrolls and Scrolling from Papyrus to Hypertext, Jack Hartnell (ed.) (Courtauld Books Online, 2020), pp. 101–121. Images are available at https://luna.manchester.ac.uk/luna/

6 Examples of mortuary rolls survive in England and in Northern Europe. For an overview for these and other rolls, see the Medieval Scrolls Digital Archive based at Harvard University, which also includes a searchable database of known rolls/scrolls: https://medievalscrolls.com/. Studies of individual rolls, or groups of rolls, include Léopold Delisle, Rouleaux des Morts du IXe au XVe Siècle / Recueillis et Pub. pour la Société de l’Histoire de France par Léopold Delisle (Mme. Ve. J. Renouard, 1866); Jean Dufour, Recueil des rouleaux des morts: (VIIIe Siècle-Vers 1536), 5 vols (Diffusion de Boccard, 2005–2013); Jean Dufour, Les Rouleaux des Morts (Monumenta Palaeographica Medii Aevi. Series Gallica) (Brepols, 2009), 3 vols. Léopold Delisle, Rouleau Mortuaire du b. Vital, Abbé de Savigni, Contenant 207 Titres Écrits en 1122–1123 dans différentes Églises de France et d’Angleterre / Édition Phototypique avec Introduction par Leopold Delisle (Phototypie Berthaud fræeres, 1909); this item, which concerns a roll from the Manche Abbaye de Savigny (France), is noteworthy because the eulogy was written by a certain Héloïse (ca. 1095–1163/4), and because the tituli were added in both France and England. For English mortuary rolls, see Matthew Payne, “The Islip Roll Re-Examined,” The Antiquaries Journal, 97 (2017), pp. 231–60, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581517000245, with further bibliography.

7 The translation is published in Boldrick (2000, p. 39), where the original Latin is also given.

8 See Boldrick (2000) and Boldrick (2020).

9 Boldrick (2000, p. 38).

10 Michael Clanchy makes this point, echoed by Boldrick (2020, p. 110).

11 W.P. Blore, “Notes on the Mortuary Roll of John Hotham, Bishop of Ely, in the Cathedral Library, Canterbury (Chartae Antiquae E.191),” Friends of Canterbury Cathedral 10th Annual Report (1937), pp. 28–31; Albert Way, “Mortuary Roll Sent Forth by the Prior and Convent of Ely, on the Death of John de Hothom, Bishop of Ely, Deceased January, A.D. 1336–7,” Cambridge Antiquarian Society Antiquarian Communications, 1 (1859), pp. 125–39, where the roll is transcribed. I have corrected it and included a translation in the appendix below.

12 Lynda Rollason, “Medieval Mortuary Rolls: Prayers for the Dead and Travel in Medieval England,” Northern History (2011), pp. 187–223. https://doi.org/10.1179/007817211X13061632130449

13 The roll is now in BM de Troyes, Ms. 2256. See Léopold Delisle, Rouleaux des Morts du IXe au XVe siècle (Historical Press, 1866), pp. 477–84; Lucien Morel-Payen and Emile Dacier (eds), Les plus beaux manuscrits et les plus belles reliures de la Bibliothèque de Troyes (Paton, 1935), pp. 152–153; “Troyes, BM, 2256,” Initiale: Catalogue des manuscrits enluminés (http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/codex/4969). The tituli are transcribed in Jean Dufour, Recueil des rouleaux des morts: (VIIIe Siècle-Vers 1536), 5 vols (Diffusion de Boccard, 2005–2013); Vol. 3, no. 317, pp. 442–445 (for the sections written from 1420–22); and Vol. 3, no. 333, pp. 614–658 (for the sections written from 1439–1441).

14 Lynda Rollason, “Medieval Mortuary Rolls: Prayers for the Dead and Travel in Medieval England,” Northern History (2011), pp. 187–223.

15 See Dufour (Vol. 3, no. 317, pp. 442–445), which concerns the sections written from 1420–22; and Vol. 3, no. 333, pp. 614–658 for the sections written from 1439–1441. When I studied the roll in Troyes, I was not able to unroll it because of its fragile condition. I was only able to study the top of the roll, containing the illuminations. The rest of the roll I studied via digital proxy, with thanks to Hanno Wijsman for providing a full set of images, kept by the IRHT; these images, however, were overexposed and only partially legible. Based on my limited first-hand study, I take issue with the way in which Dufour has numbered the membranes. What he counts as “membrane 1,” I see as two pieces of parchment, and likewise for his “membrane 2.” His numbering system is nevertheless adopted here, with the caveat that it needs to be revisited when the roll’s state of conservation allows.

16 The encyclical is transcribed in Dufour (Vol. 3, pp. 619–621).

17 Hugo’s introductory letter about debts is transcribed in Dufour (Vol. 3, pp. 618–619).