Conclusion

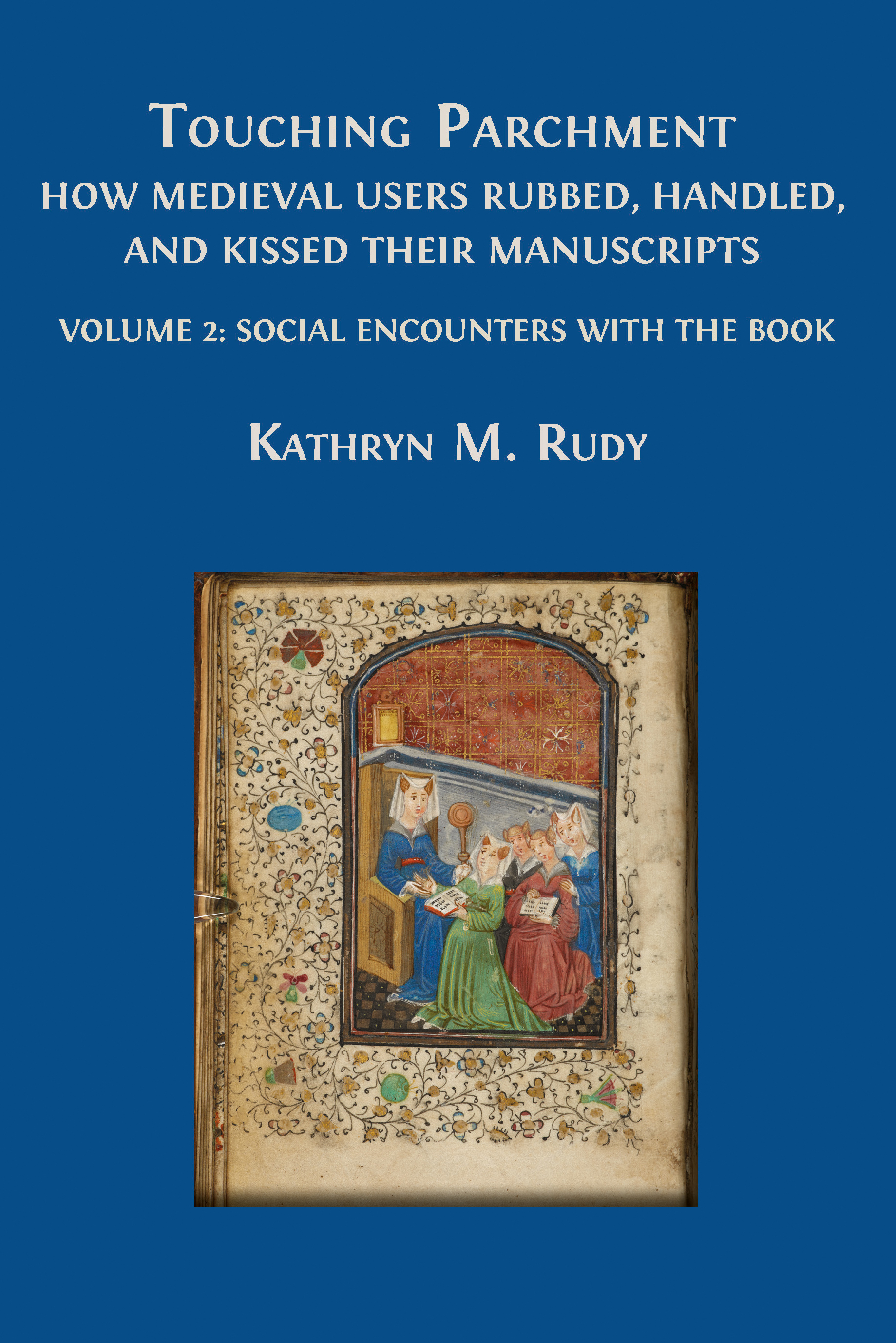

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.06

I. Models of transmitting gestures

Manuscripts discussed in this volume each contributed in some way to forging social bonds through gestures of touching the parchment page. To step back and gain a clearer overview of the ways that book touching created bonds, I want to reflect on the five models for transmission introduced in the first volume, which operate throughout this multi-volume study:

- Someone is required, by the script of the ritual, to carry out particular actions (vertical)

- A person in authority models behavior that others follow (vertical)

- A person in authority (for example, a teacher or confessor) actively shapes the behavior of others through instruction (vertical)

- Individuals apply haptic habits from one realm into another (horizontal)

- Peer groups forge and copy behavior as a route to group formation (horizontal)

To this list, I add another model of transmission:

- The demands of the physical object require a particular physical interaction (structural)

About this sixth category: many of the manuscripts discussed in this study were designed with blanks to be filled in. This includes calendars with obituaries to be added; mortuary rolls, with promises for prayers to be added on the ever-growing tail; lists of confraternity members who entrust their souls to the future living members; lists of lands, rents, and properties whose residual profit covers the costs of praying for dead abbesses. All of these book types require future interaction. When the book is being properly used, it is recording the past and future. Every new inscription implies a living continuity.

All six models of transmission permeate this volume. As is clear from the many references to Volume 1, I have argued that manhandling certain categories of manuscripts (Gospels, missals, books of legal code), which persons in authority did to carry out public rituals, conveyed techniques of book-handling that trickled into less formal and more inclusive rituals. Witnesses to those rituals sometimes carried these newly legitimated forms of book handling into new arenas and treated their own manuscripts in similarly physical ways. For example, bishops who professed obedience to the archbishop of Canterbury then imposed similar rituals on the clergy below them on the hierarchy. Such rituals expanded to include laypeople, such as the castle governors who took oaths to ecclesiastical deacons. When this happened, some of the trappings of earlier profession rituals stayed in place (such as making an utterance in formal language at an altar), while other aspects of the ritual changed (so that the text of the profession was no longer copied out for each individual, but rather written in a formulaic way in a Gospel manuscript, and in the vernacular instead of Latin). Some of the trappings of these rituals were adopted by religious, and eventually, lay confraternities. The ritual spread downward to include many more kinds of promises and even re-emerged as a form of courtly entertainment, on oaths taken on exquisite birds and on representations of those birds in manuscripts, around which prelectors and audiences gathered.

Laypeople were copying what Marcel Mauss would call a “technique of the body,” that is, a particular culturally learned corporeal behavior.1 Mauss argued that techniques of the body were passed from persons of authority downward, to those who imitated and copied them. Applying this concept to book handling, I have argued that those in control of the culture’s authoritative legal and religious books modeled the behavior of others, who applied techniques of the body in order to attain status or solidify group identity. When those techniques of the body include roughly handling books and deliberately touching images, they leave traces. Central to this study is the idea that marks of wear help to determine how medieval books were used. Therefore, my methods have expanded the kinds of evidence that can be used to write history and the kinds of questions that can be asked, by reverse-engineering the handling techniques based on the use-wear evidence.

Book-handling behaviors were shaped in childhood during reading lessons, which by their nature were social and book-oriented. Signs of wear in books made for juvenile audiences reveal that the reading lessons had a physical component. Teachers actively taught with their hands, mouths, and fingers what their charges were to do with books. Such demonstrations could continue into adolescence and adulthood, when preachers and confessors replaced mothers and teachers as the ones teaching reading, comprehension, and visual skills while also making morals manifest.

No one made morals manifest with more bombast than did the courtly prelectors who used their hands and fingers in dramatic ways as they read stories aloud. Their audiences clamored for vernacularized tales. By the evidence presented above, prelectors gave them a show. Signs of wear in manuscripts made for French, English and Spanish courts reveal that some readers not only looked at the pictures, but they used them as springboards for dramatically engaging their audiences. Part of the reason to enact gestures was to magnify the images for the benefit of a listening public. In the service of drawing their listeners into the events and helping to position their moral reception, prelectors partially destroyed the miniatures.

When I have discussed these acts of targeted destruction in front of twenty-first-century audiences, they have protested: the purpose of the images in the book was to add prestige and value, and early owners would never have willfully destroyed their precious manuscripts! But prestige only accounts for part of the motivation for illuminating manuscripts. Doing so had several other purposes: to locate particular passages in the book; to aiding the imagination; to add color; to interpret the stories; to buttress the social function of reading. While adding prestige played some role, what greater display of prestige is there than to casually consume something of great monetary value?

How, exactly, original audiences thought about damaging their books requires a complicated response. The abrasion visible to us a half millennium later suggests that the original audiences, too, were able to see the abrasion caused by these gestures. That osculatory targets were invented suggests that painters lamented the damage to their work. It is apparent that users wanted to preserve their images by sewing curtains over images (a topic to be explored in greater detail in the next volume). In keeping with this preservationist mindset, they (occasionally) confined their touching to border decoration or only touched the edges of initials and images. (I am reminded of being told, as a child, to handle photographs by the edges so as not to fingerprint them.)

But the situation was more complicated, and some some book owners welcomed the signs of wear. Users might have believe that old or worn images conferred tradition and solemnity. That appears to have motivated the officials in Utrecht to have selected Gospel manuscripts that were several hundred years old to repurpose as oath-swearing objects. The mob bosses of Chicago likewise chose very old books for oath swearing, to confer antiquity upon a borrowed tradition. Rubbed folios with mangled images could also attest to an audience’s affection for a given manuscript and its stories, just as smeared images in the Douce Vows of the Peacock could have given elderly courtiers a sentimental sigh. A well-worn children’s manuscript could attest to lessons learned, just as a well-thumbed confraternity manual could attest to (new) traditions maintained.

It is not always clear whether the traces of touching point to a private event or one witnessed by an audience. I have tried to point to evidence for public rituals, when it exists. I have also concentrated on manuscripts made on parchment, partly because parchment was expensive and durable, able to withstand considerable mechanical stress. Its expense meant that owners had a strong motivation to keep parchment books in circulation, even if the images were degraded from wear. In fact, if they were, then the prelector had all the more reason to explain what was happening in the now-murky images. Without an explicator, the images in the Douce Vows of the Peacock would be all but unintelligible: the more they were explained, the more they needed to be explained.

One idea that operates across these volumes is that imagery in books elicits behavior in readers, and some of that behavior reiterates the action taking place in representations. That includes representations in miniatures showing figures physically interacting with books, which then inspired real-world, physical interactions with books. But there’s a catch: the mirrored behavior might be translated into a micro-gesture involving a finger rather than an entire body. For example, the first miniature in an illuminated French manuscript made in the first decade of the fifteenth century shows Simon de Hesdin presenting his French translation of the Facta et dicta memorabilia by Valerius Maximus to Charles V, king of France (Fig. 190).2 The image has been touched in a specific way: most tellingly, the image of the book, which the translator is passing to the king, has been touched. Three depicted hands make contact with the book, which is represented in a red binding with two black clasps. This may in fact represent, self-referentially, the very volume in which the miniature has been painted—HKB, Ms. 71 E 68—although this volume was rebound in the fifteenth century in a white binding, so it is not clear whether the illuminator was aiming for verisimilitude.3 It is also not clear whether the first or a subsequent owner was responsible for the damage. What is clear is that a user has added his hand to the depicted hands and touched the site of the exchange in the open book. The depicted hand beckoned the physical one. Perhaps the same reader has also touched the now pock-marked hem of the translator’s black mantle, as if he were a venerable figure. This image of a book is the site of celebrating the book, and the reader has identified with the figure offering the tome. The presence of represented hands in the image invites a physical hand to the page. The image both reflects and shapes a set of social gestures centered upon handling the book.

Fig. 190 Opening folio of Facta et dicta memorabilia by Valerius Maximus, with a miniature depicting Simon de Hesdin presenting his translation to the king. France, c. 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. 71 E 68, fol. 1r, and detail

To stay with the Facta et dicta memorabilia, a reader has also touched, quite possibly with a moistened finger, the baguettes in the borders. This gesture is especially noticeable because of the way in which medieval manuscripts were made: areas of burnished gold were usually outlined in black ink in order to make the gold “pop.” The ink is relatively water soluble, and it has weak adherence to non-porous surfaces such as burnished gold. Where the small amount of ink overlaps the gold area, it is especially vulnerable. When a moist finger comes in contact with an ink-gold combination, the ink is easily smeared away, but then is “feathered” onto the more porous parchment surface.

Considering the qualities of the smears and their locations on the page can help to point to the rituals and emotions behind their genesis. The areas of a manuscript that are most often dry-touched are the lower corners (for folio-turning) and images for oath-swearing (often depicting the Crucifixion, the Last Judgment, Mary, St Christopher, or a group’s mascot-saint). Those areas of the book that are most often wet-touched are different:

- Frontispieces

- Opening miniatures (and within them: faces, hems, images of books, representations of hands, coats of arms)

- Initials

- Frames around miniatures

- Diaper backgrounds

- Baguette decorations

The first three categories all relate to the beginnings of texts, which suggests that touching these areas relates to initiating the act of reading. It is a hic et nunc gesture, a setting of the body toward the constructed world of the text. The oral performance of certain manuscripts led to the repeated handling of a particular category of paratext: the initial.

II. Touching beginnings

In The Name of the Rose, essayist, medievalist, and fiction author Umberto Eco writes a mystery set in a medieval monastic library, where a series of deaths and murders takes place. The protagonist, an itinerant monk and sleuth played by Sean Connery in the movie version, discovers that the instrument of death is a manuscript containing ideas so dangerous that its keepers are willing to booby-trap it. They do so by spreading poison on the book’s margins, so that the poison is transferred to readers’ mouths as they moisten their fingers to turn the folios. The victims present with swollen, blackened tongues before breathing their last. However, anyone who has handled medieval manuscripts on parchment will know that wetting the finger would not improve the reader’s grip: this is a page-turning gesture suitable only for books printed on fine, thin paper, especially when the book block has been guillotined. In such a book it can be difficult to isolate just the top sheet, and licking the finger can help. Licking the finger is not a gesture that would help someone turning a parchment folio: the gesture depicted in the film is a backdated projection of the gesture of licking the finger to turn a paper page. Instead of the fictive scenario from The Name of the Rose, I propose an alternative: the gesture that does involve connecting the mouth with the parchment manuscript through the hand is that of wet-touching the initial, not the corner of the page.

Touching initials is one habit of reading that bridges many of the different book types. I have argued above that prelectors touched images — including historiated initials — in order to draw the audience’s attention to the imagery and to heighten drama by animating the action with a finger. However, prelectors and other performative public readers also wet-touched initials that were not historiated. For example, the Battle of Woeringen, a manuscript introduced earlier, has a touched initial (HKB, Ms. 76 E 23, fol. 9v; Fig. 117). The ten-line letter that initiates the text “Vrouwe Margriete van Inghelant…” [Lady Margaret of England…], is filled with an abstract linear design, not a figurative one.4 Careful inspection with an unaided eye reveals that this initial has been touched multiple times with a wet finger, with several touch points across the grid. Since the initial is not figurative, the reader could not have been trying to honor or attack a represented figure, nor would it make sense to turn the manuscript toward the audience to look at an abstract design.

The small number of wet-touched initials presented in this book is not commensurate with the vast number I have encountered in 25 years of studying medieval manuscripts. Currently my file of “wet-touched initials and decoration” burgeons with some 600 items. So pervasive are smeared initials that they deserve an explanation: not all can be stray marks. This topic will return in the next volume, which treats prayer books, but I am discussing it here because I believe the gesture belongs to social formations around the book. With this in mind, and in advance of further development in the next volume, I cautiously put forward four proposals.

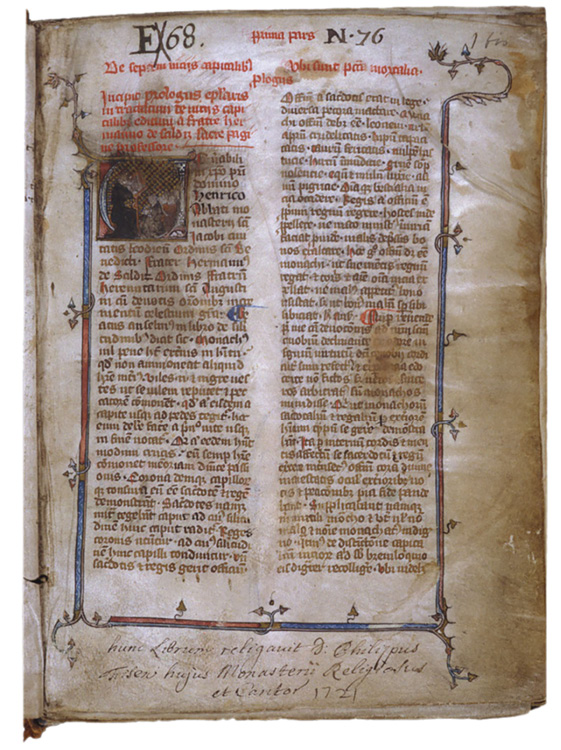

First, prelectors touched historiated initials in the same way they touched images: to draw the audience in while animating the figures. As I have touched upon throughout this book, some of the most emphatic book-handling practices took place in front of an audience. Prelectors’ activities were not limited to courtly reading, and historiated initials damaged by wet-touching appear in both secular and sacred manuscripts, such as at the opening of a copy of Tractatus de septem vitiis capitalibus duplex, written by Hermannus de Schildesche and copied by a Benedictine monk at the monastery of St James in Liège some time between 1316 and 1342 (Fig. 191).5 The opening initial depicts a teacher in monastic robes reading from a book to a group of students on the floor in front of him. The initial has been repeatedly touched and smeared, as if touching the initial belonged to the process of prelection, as depicted in the image.

Fig. 191 Incipit of Tractatus de septem vitiis capitalibus duplex by Hermannus de Schildesche. France, 1316–1342. Tilburg, TF, Ms. Haaren 13, fol. 1bis recto

Second, prelectors even touched initials that lacked figurative imagery in order to mark the beginning of a session of reading. A twentieth-century equivalent, from the era before teleprompters, occurred on the nightly news, when the newsreader would tap a sheaf of typescript papers to square them up. In my lifetime, when all newspapers were physically larger, people would often flick the center of the open newspaper with the middle fingernail before beginning to read. These are medium-specific conventions of initiating reading.

Third, prelectors would touch their tongues and then smear the opening initial as a gesture which brought the voice of the text into contact with the tongue of the reader. This culturally pervasive gesture was shared by religious and lay people alike. The tongue-to-initial gesture forged an intimate bond between the words written on the page and the words uttered from the lips of the reader.

A fourth reason late-medieval readers may have touched initials was by way of testament: perhaps they were taking a casual oath promising to stay true to the words on the page and not to deviate from the script. This is an extension of the book-centered gestures individuals made when they swore oaths to a leader, group, or office. In the current context, perhaps they swore to be true to the text. In our current screen-based culture, public readers (including, for example, newscasters) put textual evidence on the screen and read the words verbatim, as a way of demonstrating that their oral performance is true to the text they are reading.

I suspect that in the printed age, by some means of social transmission, that gesture of wet-touching initials morphed into wetting the finger for the purpose of gripping the paper page (especially one with a guillotined edge) more effectively. In other words, the gesture of touching the tongue may have changed meaning with the new substrate of paper. I leave it to a historian of early-modern public reading practices to confirm or debunk this hypothesis. Because my purview stops at the edge of the handwritten parchment world, I only seek an explanatory model for this pervasive gesture that left its tracks in manuscripts.

The gesture of wet-touching initials not only occurs across genres of manuscripts, but also across the stretch of Western Europe. Most of the examples I have given in these volumes have come from Northern Europe, but in fact wet-touching initials also occurred in the British Isles as well as in Southern Europe. I will provide some examples, which supplement those discussed above. The topic will return in the next two volumes.

III. Touching initials across Europe

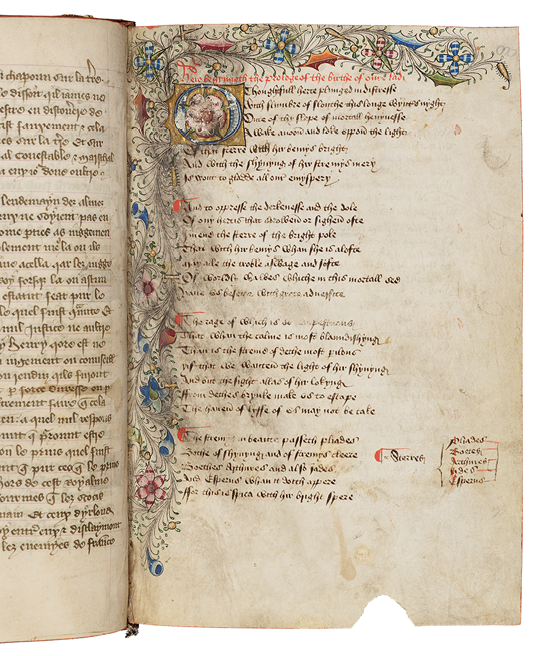

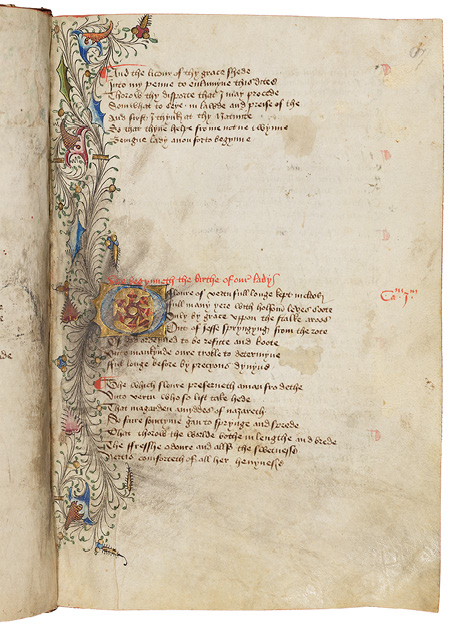

The social scene around initial-touching is corroborated in many manuscripts that have a social function. The effects of this gesture appear, for example, in numerous English courtly manuscripts, such as a copy of John Lydgate’s poem called the Lyfe of our Lady (Oxford BL, Ms. Bodley 596; Fig. 192).6 Since the text is written in rhyming verse, one can assume its aurality. The initial O, which opens a prayer “O thoughtfull herte plonged in distresse,” has been severely wet-touched. The reader has also stroked the border decoration, as if it were long tresses tumbling down the spine of the stanzas. In particular, the reader has targeted the red rose at the center of the letter.7 Furthermore, the other initials within the text have been similarly rubbed. The stanza detailing the “Birthe of our Lady” has been heavily wet-touched. The ritualized action has lifted the blue paint around the initial and liquefied the black ink outlining the gold (Fig. 193). Subsequent internal initials display evidence of similar treatment, where the reader has brought his moist breath to the page time and again.

Fig. 192 Folio in a compiliation volume, at the incipit of John Lydgate’s Lyfe of our Lady. England, ca. 1450–1475. Oxford, BL, Ms. Bodley 596, fol. 86r

Fig. 193 Folio in a compiliation volume, at the incipit of John Lydgate’s Birth of Our Lady. England, ca. 1450–1475. Oxford, BL, Ms. Bodley 596, fol. 87r

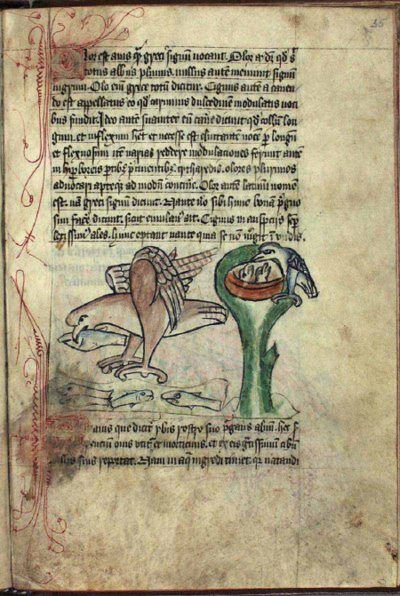

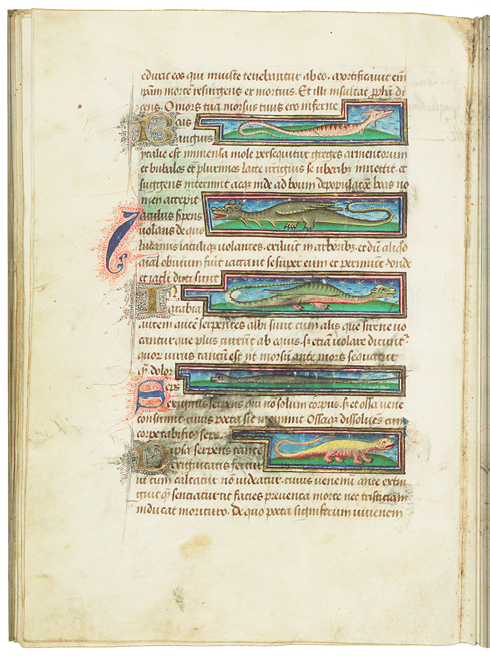

Texts not written in verse, but nevertheless charismatic with potential public appeal, often have wet-touched initials, as if a prelector were performing with the manuscript. Such is the case with the Bestiary of Anne Walshe (Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek Gl. kgl. Saml. 1633 4˚), an English manuscript of the early fifteenth century.8 Although the manuscript has some water damage, that does not explain the targeted touching that has obliterated selected initials (Fig. 194). The reader touched a subset of the initials, possibly corresponding to the beginning of a session of reading. She or he did not touch the images. In a French bestiary made around 1450 with overlapping content, one of the readers has ignored the initials but has traced the length of one of the serpents, as if re-iterating what the illuminator had already communicated with the frame: that the beast is extraordinarily long and skinny (Fig. 195).9 Even though the texts are similar in the two manuscripts, the patterns of wear speak to two different emphases in reading, one involving reciting the words, and the other, collective looking.

Fig. 194 Folio from a bestiary with an entry on the eagle. England, ca. 1400–1425. Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek Gl. kgl. Saml. 1633 4˚, fol. 70v

Fig. 195 Folio from a bestiary depicting snakes and salamanders. France, ca. 1450. HvhB, Ms. 10 B 25, fol. 42v

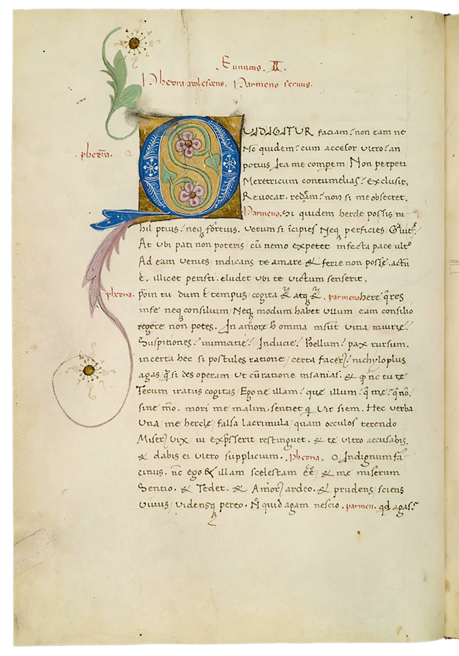

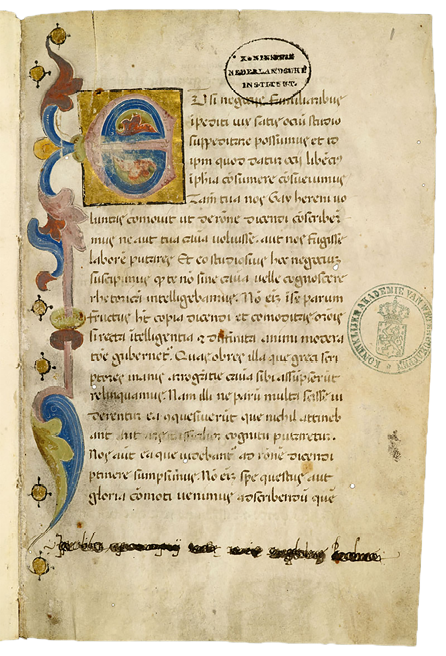

Stage plays and dialogues imply a spoken performance, so it is not surprising to find wet-touched initials in a copy of the Comedies of Terence, made in Northern Italy ca. 1440–60 (HKB, Ms. 128 E 8). This manuscript has delicate humanist script executed with a narrow nib and is decorated with painted and gilt initials (Fig. 196). Other texts with obvious aurality also have wet-touched initials. For example, a copy of the Rhetorica ad Herennium—a text wrongly attributed to Cicero in the Middle Ages—was made in Italy c. 1400–1410: it has an opening initial that has unmistakably been touched with a wet finger (Fig. 197). This book would have been read by those who wanted to improve their performance as rhetoricians, to give convincing oral arguments. The book has other signs of wear, including inscriptions at the bottom of the first folio, and various stains, suggesting that an early user considered it a utilitarian object. Its readers have smeared text and dripped wax.

Fig. 196 Folio from the Comedies of Terence. Northern Italy, ca. 1440–60. HKB, Ms. 128 E 8, fol. 23v

Fig. 197 Opening folio of Pseudo-Cicero, Rhetorica ad Herennium. Italy, 1400–1410. HKB, Ms. KA 1, fol. 1r

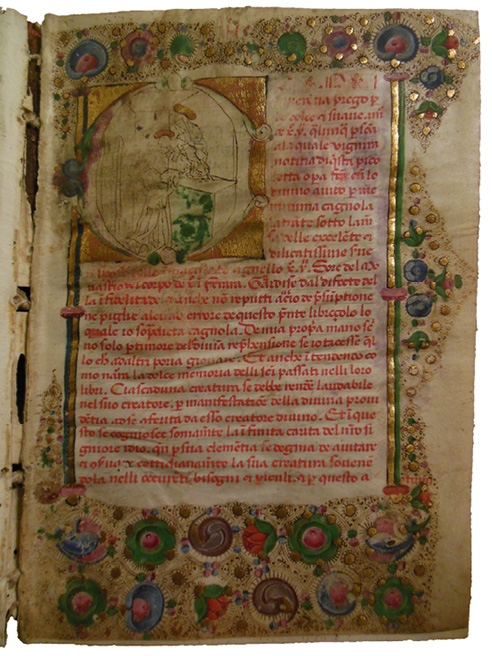

Ritually wet-touching initials could also contain a gesture of collective veneration. That seems to be the case at the convent of Corpus Domini in Ferrara, where the sisters began venerating Caterina Vigri da Bologna shortly after her death in 1463, when it was discovered that her body was uncorrupted.10 Caterina, an Observant Franciscan nun, had experienced visions, which she then described in texts by her own hand. The nuns who survived her produced some 20 copies of her book Le sette armi spirituali (The Seven Spiritual Weapons) for their own use and for the use of Clarissan convents in the region. One of these is now preserved in Ferrara (Biblioteca Comunale Ariostea, MS Cl. 1.354, fol. Lr; Fig. 198). Overall, the opening folio is moderately worn, with light fingerprints in the lower corner. Dramatically, however, the initial has been repeatedly touched, which has abraded the upper and lower right corner, as well as the green paint that was on the altar. The initial C represents Caterina as a nun in Ferrara, experiencing a vision that appeared to her on Christmas Eve when she was praying at an altar: the Christ Child embraced her, and she smelled his sweet scent. The desire to touch this initial could have had complex motivations: a desire to touch the words that Caterina wrote, where the initial stands as a synecdoche for the whole; a desire to touch Jesus as Caterina had; a desire to touch the beatified Caterina herself; a desire to involve the body in reading, just as Caterina involved her tactile and olfactory senses when she held the Christ Child in her vision; a desire to engage listeners with a theatrical gesture as a preamble to reading a Christmas story aloud.11 Whatever the desire, the impact on the paint was severe.

Fig. 198 Initial C with the Christmas Eve Vision, in Caterina da Bologna, Le sette armi spirituali. Ferrara, after 1463. Ferrara, Biblioteca Comunale Ariostea, MS Cl. 1.354, fol. Lr

It is difficult to know whether the middle of the initial was originally fully painted, or whether it originally consisted only of a pen drawing with a green altar cloth and gilded haloes. Certainly, the letter itself was magenta and green but is now the color of parchment. The image shows a sculpture depicting Mary and Jesus on an altar, where the Christ Child lunges toward Caterina da Bologna who kneels before the altar to receive him. Perhaps the image was never completed, but the manuscript was deemed so urgent that the sisters began using it in its half-finished state.

What is clear is that users have touched the initial with a wet finger, dislodging the detail of Caterina’s face, abrading the other colors in the letter, and causing the gold leaf to flake off and reveal the red primer. One or more readers wet-touched the initial many times. Some of that activity was directed at the four gilt corners of the letter; this has smeared paint nearby, including all rubrication in the vicinity of the initial. Some of the touching was directed at the halo of Catherine, and the area just behind her head in the image, as if the reader consciously avoided destroying the image. What is most telling is that the entire folio is buckled, as if the wetness has caused that part of the page to shrink and stiffen, with textural consequences across the expanse. I took the photograph reproduced here and purposely shot it in raking light in order to reveal the wrinkles in the parchment, caused by introducing moisture, probably in the form of a saliva-wetted finger.

I strongly suspect that wet-touching initials is a culturally-formed habit that initiates the reading process and has different valences in different contexts: with this gesture, readers can announce their intention to read; show respect for the page, the image, or the letter; make physical contact with the author of a text (which, in certain Christian contexts, conveys divinity); respond to the subject of a figurative initial; draw listeners’ or choral members’ attention to the beginning of a text; or leave a mark in order to announce that reading has occurred. I wonder whether this gesture has survived in the way that some readers (especially older people) lick their fingers before turning pages. This cultural habit may be dying out now, not just because screens have overtaken printed paper, but also because fingerprint recognition systems will not recognize a wet finger.

My perennial and unanswerable question is: did people wet-touch initials without an audience? Did they do so while reading privately and silently? If licking the finger is a cultural habit, then the answer leans toward yes. But if touching the initial is a form of demonstration, then no: the gesture lacks meaning outside a social context. And how much reading took place alone and silently? This is difficult to know. The term “private devotion” is probably overused and may not reflect social practice effectively. There may have been a significant amount of silent reading alone in certain monasteries, but the microcultures of such reading are difficult to gauge. I will take up this thread in the next volume.

By way of closing, I acknowledge that users transferred some of these practices onto printed paper, although I leave it up to others to investigate the flavor and extent of such practices, as, with the introduction of the printing press, the sheer number of books swelled and the range of their subjects shifted and soared. Thanks to the work of David Areford, Suzanne Karr Schmidt, and Kimberly Nichols, we know something about how practices of handling translated to the early print.12 There is more to learn in this arena by deploying use-wear analysis.

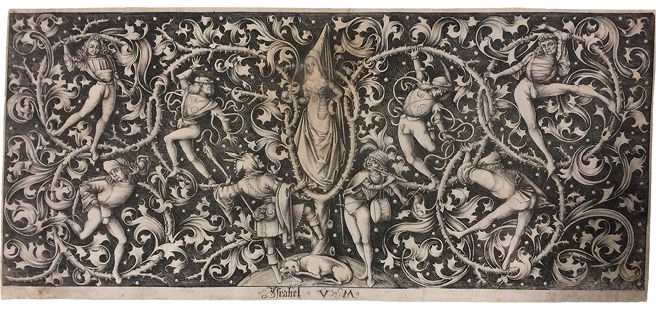

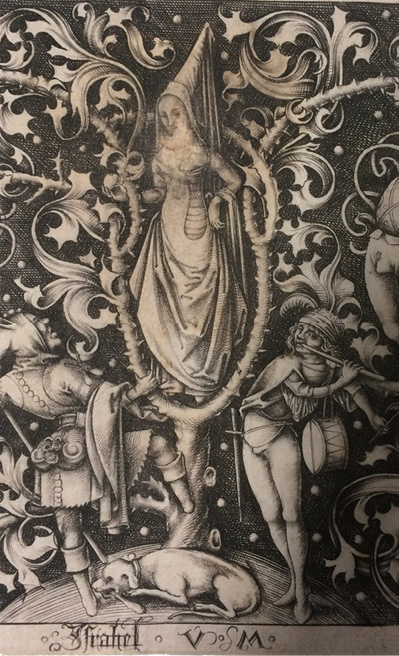

Fig. 199 Israel van Meckenem, Horny, thorny dance moves in a curvilinear structure of acanthus, with a woman at the center. Print on paper made from an engraved copper plate, Middle Rhine, before 1503. Bologna, Print Cabinet. PN21342, and detail

Consider an engraving signed by Israel van Meckenem depicting leggy men in tights making music and dancing around a woman who has hooked up her skirt slightly to prevent herself from tripping as she dances (Fig. 199). It presents a fantasy of joyous reverie. The male dancers cavort gingerly, for each is confined to a thorned hoop, a structure which taunts: touch if you dare! The print would have originally had larger margins, but these have been trimmed down to the quick, as is the case for most of the fifteenth-century prints in the collection. It is in excellent condition, except for one visibly abraded area: the woman’s chest. Whatever the feelings that the songs, dances, and costumes have engendered, they have resulted in the beholders’ reaching into the picture to fondle female flesh. Whatever prurient interests users of parchment manuscripts might have had, I leave it to others to investigate the role of sexuality in touching printed material in the early modern age and beyond. The subject is too racy for me, and in the next volume, I will return to piety to consider ways in which people expressed devotion by touching their manuscripts.

Public activities involving codices in the late Middle Ages all attempt to make religious devotion, social belonging in the context of brotherhoods, civic duties, and group entertainment more experiential. In so doing, they leave marks—often cumulative marks—in the books that provided their authoritative structures. Participation in religious and civic life makes tangible marks on history. Users of books become agents in the formation of the images and texts. By wearing them down in specific ways, they mold their own books to reflect their own use-history. They become part of the making process, one stroke and kiss at a time.

Afterword: The recent past

I have presented a few dozen examples and could present hundreds more. My goal in these volumes continues to be to offer new tools for thinking through the early reception of manuscripts, and therefore to better understand users’ emotions and motivations. May these ideas provoke a discussion!

In thinking about the legacy of book-touching behaviors in the twenty-first century, one can consider the real sense of loss that readers feel when they handle digital books instead of their paper counterparts. Book reading formerly took place on trains, in waiting rooms, living rooms, and libraries. These spaces are increasingly harboring only digital reading of a much different sort than the sustained reading of full books. Digital reading is both more social (because of its potential for connectivity) and more solitary (as those immersed in screens are often absent from the people in their immediate sphere). Certain social functions of the book persist, but they are negligible: writing comments in guest books comes to mind.

As I finish writing this book, a story about swearing an oath on a book has made the news: Makenzie Lystrup was appointed Director of Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. When she took her oath of office, she eschewed the Bible traditionally used for this ceremony but rather placed her hand on a copy of Carl Sagan’s 1994 book, Pale Blue Dot. One could say her oath-prop had historical continuity: it was written by an enlightened being, Carl Sagan, and concerns a world beyond earth. In this way, she updated the medieval procedure but fully adapted it to the secular space age. The idea of performing rituals on a book has survived from the Middle Ages, even if the credulity in the supernatural content of the text has been questioned, at least in some arenas.

1 Marcel Mauss, “Techniques of the Body,” in Incorporations, Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter (eds) (New York, 1992), pp. 455–477.

2 All the miniatures were cut out but later glued back in with paper tabs.

3 In the fifteenth century, the coats of arms were added to the initials; this heraldry belongs to the Berlaimont family, who may be the book’s second owner. This may be the party who rebound the volume in white.

4 Recent scholars have considered the complexity of abstraction. See the essays in Elina Gertsman (ed.), Abstraction in Medieval Art: Beyond the Ornament (Amsterdam University Press, 2021).

5 For a description of this manuscript, see https://bnm-i.huygens.knaw.nl/tekstdragers/TDRA000000001226

6 See The History of English Poetry from the Close of the Eleventh to …, Volume 2 (1840), pp. 386–388. Heather Blatt, Participatory Reading in Late-Medieval England (Manchester University Press, 2018), discusses “haptic visuality, in which the eyes facilitate touch” (p. 267) in terms of the manuscripts of John Lydgate, but this approach owes more to the theories of Gilles Deleuze than to the close examination of the parchment manuscript.

7 There is no corresponding offset on the facing page, which indicates that these pages did not originally face each other.

8 The manuscript has been digitized: http://www5.kb.dk/permalink/2006/manus/221/eng/Binding+%28front%29/?var=For this bestiary in its manuscript context, see Elizabeth Morrison, Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019).

9 The Hague, Museum van het Boek, Ms. 10 B 25; contains: Bestiarium, Herbarius, Anatomia corporis humani; and Lapidarius by Marbodus Redonensis. Only the images for the bestiary have been completed: space for the miniatures was not reserved after fol. 43v. See Anne S. Korteweg et al., Splendour, Gravity & Emotion: French Medieval Manuscripts in Dutch Collections (Waanders, 2004), cat. 25.

10 Serena Spanò Martinelli and Irene Graziani, “Caterina Vigri between Gender and Image: La Santa in Text and Iconography,” in The Saint between Manuscript and Print in Italy, 1400–1600, Alison K. Frazier (ed.) (Toronto Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2015), pp. 351–378, argue that the cult of Caterina was growing just as printing entered Italy; consequently, two different audiences venerated the saint, one through the medium of print and the other through manuscript.

11 Theresa Zammit Lupi, “Books as Multisensory Experience,” Tracing Written Heritage in a Digital Age, Ephrem Ishac, Thomas Casandy and Theresa Zammit Lupi (eds) (Harrassowitz, 2021), pp. 21–31, carefully considers the impact of the physical book on the user’s senses, including the sense of smell. Henrike Lähnemann considers how the sisters at the Cistercian convent of Medingen enhance their devotions with the physical qualities of the book; see Henrike Lähnemann, “The Materiality of Medieval Manuscripts,” Oxford German Studies, 45(2) (April 2, 2016), pp. 121–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00787191.2016.1156853

12 David S. Areford, The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe: Visual Culture in Early Modernity (Routledge, 2017); Suzanne Kathleen Karr Schmidt and Kimberly Nichols, Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life (Art Institute of Chicago; distributed by Yale University Press, 2011).