Introduction

© 2024 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0379.00

There are two kinds of readers: preservationists who handle books gingerly and protect them from all manner of contagions, including fingerprints, and users who treat books as utilitarian objects. Manuscripts owned by the former have been overrepresented in exhibitions and canonical histories. Touching Parchment focuses on manuscripts owned by the latter. Since the 2010s, such manuscripts have increasingly entered the scholarly discourse. Before that period, most exhibitions and monographs that showcased manuscripts only featured luxurious, pristine examples with celebrity provenance. I consider it a sign of progress that scholars increasingly pay attention to images and manuscripts that are marred, tattered, anonymous, and filthy.

This multi-volume study analyzes touched books in late medieval Europe, a time and place when touching had a charged meaning. Curative touching was implicated in the pervasive culture of touching relics, objects with an aura of holiness whose efficacy depended on propinquity and belief. Relics populated every altar. In the Christian West, the earliest and most famed cures with relics occurred with the True Cross, with which St Helen revived a corpse. Splinters of the True Cross populated thousands of altars across Europe; touching this object, as well as representations of it, channeled supernatural forces.

Fig. 1 Folio from the Life of St Edward the Confessor, with a miniature showing pilgrims climbing into the saint’s shrine through apertures. Cambridge, UL Ms. ee.3.59, fol. 29v

Saintly remains also effected cures, and medieval Christians actively sought to touch them. Some saintly tombs were even designed so that the afflicted could climb bodily through apertures in reliquary cases in order to be surrounded, and in maximum physical contact with, the healing objects (Fig. 1).1 The twelfth-century German monk Thiofrid asserted that contact relics were formed when “divine power works through things that have been consecrated by […] contact with […][a saint’s] hands.”2 Contact relics could be endlessly produced at the shrines; they often constituted objects—especially cloths, lengths of string, and other items made from humble materials—which had merely come in contact with the saint.3 For example, at the shrine of St Hubert in the Ardennes, pilgrims suffering from rabies would undergo a ritual involving a piece of fabric that had touched the shrine. A priest would slice the afflicted person’s forehead open, insert the shrine-touched fabric into the incision, and bind it together with a bandage. A painting in a manuscript containing the Life of St Hubert shows afflicted pilgrims lining up to have their bandages removed; when they do, they are restored to full health at the foot of the saint’s altar (Fig. 2). In this way, touching was a conduit to cure, connecting saints with believers.

Fig. 2 Pilgrims receiving treatment at the shrine of St Hubert in the Ardennes. Bruges, 1463. HKB, Ms. 76 F 10, fol. 25v.

The healing powers of touch extended from the realm of saints to that of royalty: the king was able to cure his subjects of their scrofula—an inflammation due to tuberculosis—merely by touching them. As Marc Bloch described in his masterful book of 1924, Les Rois Thaumaturges, both French and English kings exercised this practice because performing this limited miracle demonstrated their divine ordination.4 Sufferers made a sometimes-arduous journey to receive the royal touch. Each pilgrim reaffirmed his belief in the monarch, just as each person who employed a Gospel manuscript in a ritual reaffirmed the power of sacred writ.5

Steeped in a culture that elevated the therapeutic touch of holy relics, medieval believers carried these habits and expectations to another class of objects which were likewise divinely touched. Manuscripts, particularly Gospel manuscripts, often contain images depicting the saints themselves touching books. Such manuscripts were conduits to the hands, pens, and very breath of their putative authors. It is therefore not surprising that these objects were heaped with numinous value and, in turn, were touched reverently by medieval believers, who expected great things from rubbing, kissing, and performatively handling them.

When I have talked publicly about how deliberate and charged touching also extended to books, members of the audience have often exclaimed, “I simply cannot believe that medieval people would mishandle their books in ways that would damage the expensive miniatures!” Our notions of art and preservation corset our modern imagination. Since the post-war era every child who has been permitted (or forced) to go to the great national museums has been told to “look but don’t touch.” We have embodied a collective message about how to engage with art objects, but if one defines “art” as an object of beauty with no practical utility, then this simply cannot be a correct designation for most medieval manuscripts. Liturgical and devotional manuscripts had utility. Even many highly illuminated courtly manuscripts, which had an immediate value as display objects, were heavily pawed during public recitations and during rituals. Books played utilitarian roles in social settings in the European late Middle Ages, and signs of wear within those books can help reveal how books were handled. Sometimes that touching was thaumaturgic, but often the activity formed a social glue, marked a rite of passage, or allowed audience members to feel like part of a group. That is the central idea in this book.

I. Ideas from Volume 1

The previous volume focused on manuscripts in ecclesiastical and legal settings, where they were central to various rituals. Two big ideas about the use of books in Christian ceremonies emerged in the previous volume.

A. Book as divine

The first was that the book-object itself was divine, a manifestation of God’s Word made flesh. As the Gospel of John asserts, “In the beginning was the word.” Because of this, touching a Gospel manuscript was tantamount to touching God, and for certain applications, such as touching a holy object while swearing an oath or swearing to the truth of a testimony, touching a Gospel manuscript was an appropriate ersatz for touching relics. The four Gospels were the operative portal to the divine. Certain manuscripts, especially Gospels and other manuscripts used at an altar, borrowed the status of relics. Swearing rituals, which were discussed in the first volume, operate with this set of assumptions. In the current volume, powerful book-objects, when touched by group members, help to create group identity.

B. Ritual as template

The second big idea from Volume 1 is this: the words spoken by the priest at the Mass during the rite of the Consecration, which were centered around an image of Christ Crucified, motivated the use of the manuscript in other Christian rituals. In other words, some of the gestures around the Mass were reappropriated for other rituals. This is especially true from the twelfth century onwards, when instructions for performing the Mass, which amounted to “stage directions” in the form of rubrics, began to be codified in a book type known as the missal.6 (Prior to the twelfth century, a priest would have referred to multiple book types in the course of fulfilling his duties.) A shift toward grander gestures occurred as the Mass was becoming more theatrical. Central to this theater was the moment during which the priest kissed the book, specifically the image of Christ Crucified. The sacrifice centered on the image, re-enacting the consecration of the Eucharist at every Mass. This required an appropriate official to utter prescribed words over a disc of bread. For supernatural functions, images of Christ Crucified ripened the ritual space, as did the Gospels themselves. Images and gestures from the Mass were redeployed in other kinds of rituals that demanded gravitas.

Whereas Volume 1 considered manuscripts handled by persons in authority who touched books as a means to lend divine endorsement to particular rituals, this volume brings a different group of manuscripts into focus: those that exerted a force of social cohesion on their users. The books discussed in this volume were used by multiple people at once. Those people included teachers and students, public readers (or “prelectors”) and their audiences, members of confraternities, and coreligionists in a monastery. Many other social groups existed, but the choices here represent a selection. Books served as a social adhesive, uniting individuals in confraternities; courtly audiences; catechism students; ecclesiastical officials within their hierarchies; monastic communities who prayed for the dead; and religiously defined social groups who rehearsed their collective commitment by retelling Biblical narratives. This could include the knowledge of Christianity or stories of Exodus, in the case of the Passover feast.

Members of faiths other than Christianity had particular touching practices, too. For example, Muslims touched the Great Kabba while circumambulating it, and Jews touched prayer shawls while actively avoiding touching the Torah with their fingers.7 However, the current study is not comparative: it is largely restricted to the European late Middle Ages in a Christian context.

II. Taxonomy for touching

Types of damage to the manuscript can be organized into a taxonomy, which helps to categorize them around intentions and emotions. (See the visualization “Taxonomy of ways of touching manuscripts,” with a QR link). Below I will recount the list but selectively, emphasizing those causes of damage relevant to the present volume. As the diagram makes plain, damage is divided into two large categories: inadvertent wear and targeted wear. All books are subject to the former. As a rule, I’m not interested in damage caused by faulty storage (such as leaks and insect damage), because passive neglect is not interpretable the way active use is, since it lacks intention and emotion. I am, however, interested in damage that has resulted from use—even normal, expected, and sanctioned use—including regular handling, wax stains, holy water, or other specific stains (i.e., inadvertent wear), because these stains reveal the conditions of handling.8

This volume considers manuscripts used in social contexts, encompassing learning spaces, courts for public readings, private residences’ communal rooms, church altars, and monasteries. Except for a few brief excursions, I have to set aside study of annotations and deliberate additions, not because they fail to fascinate, but because including them would make the subject swell beyond manageability, and other scholars have treated these subjects with great success. In the social contexts explored here, the act of kissing the book is rarer than in contexts involving figures in authority. Instead, another operation reigns: moistening the finger with a kiss before touching the book. So important and pervasive is this action that I have dedicated a chapter to it. Book users treated images, initials, and decoration with this action. The gesture creates a moment of intimate physical contact between the reader and the word, as symbolized by an initial. In doing so, it forges a physical link between the breath of the author and that of the reader. That gesture returns in a wide variety of manuscripts, with many examples used for reading aloud in social settings.

A. Themes

This volume has three major themes. First, public speakers used images to animate and illustrate their presentations, to engage the audience, and to improve their performance skills. In thinking about touched and damaged initials, images, and decoration, my goal is to build possible scenarios that explain the patterns of wear.

Second, the prelector assumes a moralizing role. She—or more likely, he—touches images in manuscripts in front of small audiences with the goal not just of transmitting the narrative told in the accompanying text, but also of demonstrating an appropriate moral stance toward the characters represented in the images.

Third, hands are pivotal in fostering community through books. The terminology used in this book—manuscript, handling, holding, touching, manipulate—forms a constellation of topics involving books and hands. Even closed books (i.e., their bindings) were touched. Folios and elements inscribed on folios (words, images) were touched. Paratextual elements (decoration, margins, bookmarkers, curtains, tabs) were touched.9 These activities, which all involve the hands, are tangential to reading but essential to demonstrating the status of the book and the person operating it. Christianity was, as these gestures remind their audiences, a religion of the book, and books need to be handled in order to divulge their contents and to fulfill their roles as actors in ceremonies.

These three themes will re-emerge in this volume and throughout the study.

B. Ways of touching manuscripts

One basic premise motivates this study: people leave traces in their manuscripts when they handle them. By studying these traces, one can hypothesize how the user touched the book, and consequently build a scenario that helps to recreate the feelings, habits, and emotions of people from the past. Such traces fall into two large categories: inadvertent handling and targeted touching. Nuanced sub-categories fall beneath these two large umbrellas. Below I provide an overview of each type of wear, as I did in the Introduction of Vol. 1, but this time concentrating on the categories that particularly operate in the current volume—that is, in social contexts.

1. Inadvertent wear

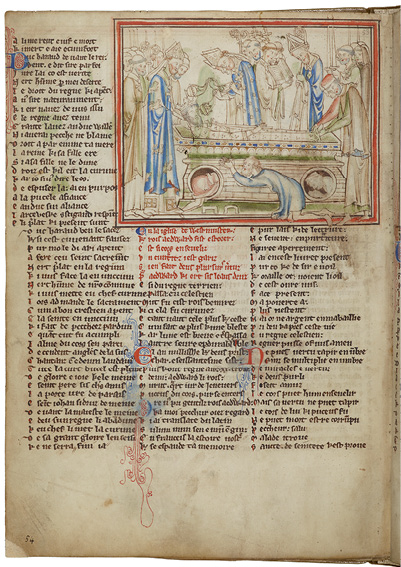

Stains reflect the contexts in which manuscripts were handled. For example, many Haggadot undoubtedly trap traces of food—unleavened breadcrumbs and ritualistic wine—from the Passover meals they helped to choreograph. The Haggadah with its scripts and stories stood at the center of the social event. For example, the Lombard Haggadah (made around 1400) contains stains from red liquid precisely at the opening describing the drinking of wine and depicting figures doing just that (Fig. 3).10 More broadly, one should not be surprised to find contextually appropriate stains in utilitarian manuscripts, such as splashes from flasks in alchemists’ books, or grease marks in cookbooks.

Fig. 3 Opening in the Lombard Haggadah, fols 28v–29r. Milan, ca. 1400. Private Collection (formerly: Les Enluminures).

More generally, inadvertent wear includes fingerprints in the margins left by readers who were simply handling the book in the intended way—opening the book and turning its folios. A user inevitably touches the clasp, binding, and folios to operate the codex, or the flap, membranes, and spindle to operate a roll. While inadvertent wear undeniably forms the basis for understanding the intensity with which a book was read and handled, it is not the main form of wear treated in this study. This brings us to the other form of wear.

2. Targeted wear

While inadvertent wear occurs as a result of opening the book and reading it, targeted wear results from deliberately interacting with the marks on the page (words, images, and decoration). There are at least ten distinctive ways of touching books with a finger, and even more ways involving other body parts, such as the whole hand. This is summarized in the diagram (linked with a QR code above). In asking why the image looks the way it does, one should consider that different ways of handling yield different forms of abrasion. One can touch the depicted hem of a beloved saint with a kissed finger, alighting just once, and lift a circle of paint that has been reconstituted by the saliva carried on the finger. Or, with a dry finger, one can trace the trajectory of the Holy Spirit coming down from the firmament. The second act of touching differs significantly from the first, as it is dry and moves across the surface. This comparison reveals that different kinds of volitional touching can leave quite different traces. I contend that these traces can be differentiated. Those that play a role in this volume are as follows.

Wet-touching

I have invented the term “wet-touch,” which is shorthand for “touching something with a finger that has been moistened with saliva.” There are two motivations for this action: to transport a kiss to the image, or to transport the paint to the lips. This will be one of the most important terms in play in this volume.

Touching images with power

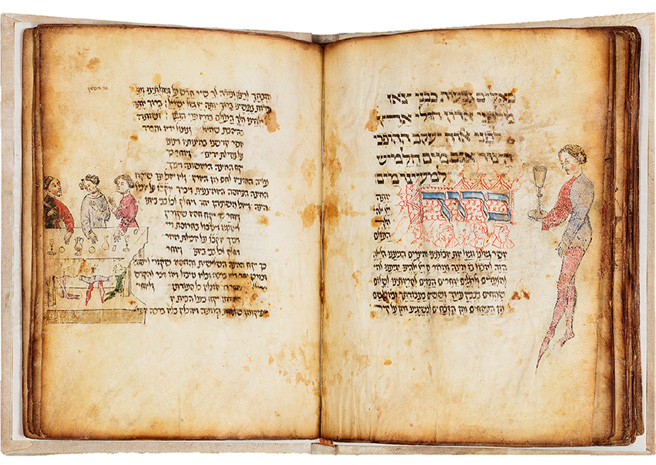

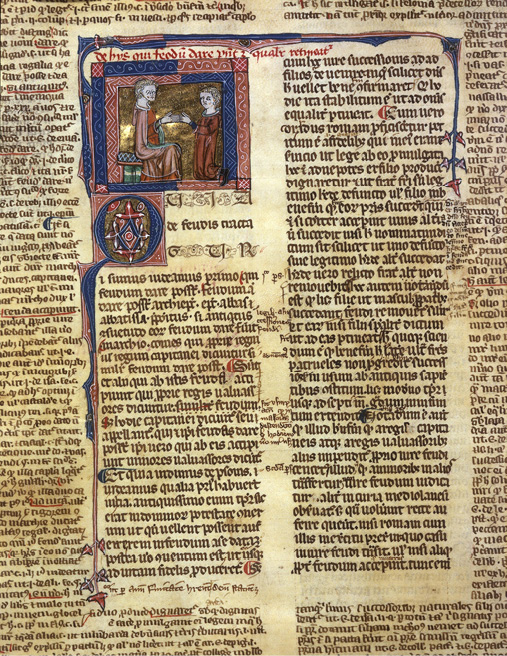

Like a Gospel text, an image could likewise be charged with power, and touching it could be tantamount to making contact with the divine. Touching, generally with a dry hand, could signify deep respect, reverence, or even playful mimicry. One can consider a Book of Hours from Southern France, possibly Montpellier (Ms. Rawl. liturg. f. 16; Fig. 4). It contains tables for calculating the date of Easter beginning in 1473, which suggests that the book was made in that year. Facing the Easter tables is a shield, which van Dijk describes as “azure portcullised argent upon which a fess or.”11 The binding is still intact (Fig. 5). Relevant for the current discussion is the way in which the image of the two hands is damaged: it has been repeatedly touched by someone laying a finger over the hands and dragging the finger across the image, as if joining the represented hands with a slight up-and-down shake. The handclasp was a highly charged gesture in the late Middle Ages: during the ritual of fealty, a lord enveloped a vassal’s hand in a visible and intimate gesture that also signified the lord’s protection (Fig. 6). In a different context, couples clasped hands to outwardly demonstrate their marital vows. Even when the gesture morphed into the modern handshake, it retained the connotations of social bondage. By touching the image, the engaged beholder was joining in on the act that the handshake symbolized: the peaceful joining of two families through a marital oath. A coat of arms with a handshake on it turns an ephemeral gesture into a permanent symbol.

Fig. 4 Frontispiece from a Book of Hours, with a hand-clasp gesture. Southern France, 1473? OBL, Ms. Rawl. liturg. f. 16, fol. 3r

Fig. 5 Binding from a Book of Hours, tooled and gilt leather. Southern France, 1473? OBL, Ms. Rawl. liturg. f. 16, binding.

Fig. 6 Incipit of the Constitutiones feudorum cum glossis. France, 14th century. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 2262, fol. 174v.

Treating the book as symbol

To ritualistically touch the closed book with a dry hand, without reading it, is to acknowledge the symbolic value of the book. The previous volume presented many examples of people touching a page because it contained a Gospel text, which Christians considered a relic of God (the Word made Flesh). Some individuals, in a ritual setting, demonstrated their belonging to a group by touching particular books, usually liturgical manuscripts or those containing Gospel excerpts.

Dramatic touching with a finger

Performers, such as raconteurs or prelectors, might point at images while reading aloud from an illuminated manuscript; however, they might also add more dynamism to the pointing gesture to animate the images. Gestures added for dramatic effect while reading aloud showcased a desire to animate and vivify the narratives, emphasizing the liveliness of tales and histories. The specific gesture depended on the narrative context. For example, it could involve tracing the journey of a horse and rider into battle in an illuminated romance or chronicle. This action would result in dry smears. One gesture conducted during a single event might suffice to effect a change on the picture’s surface. Such gestures are often directed at depictions of dramatic action, at figures’ faces, hands, or other localized parts of the image in order to enliven the narrative. Here, quick excitement drives the activity: the book’s handler not only explains the passage, but also conveys some of its significance through dramatic gestures.

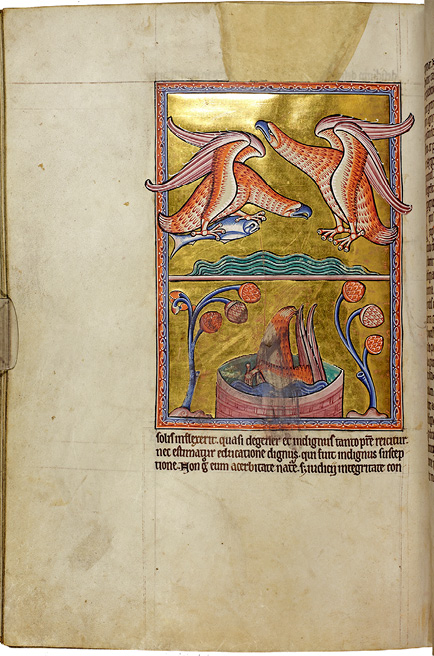

Fig. 7 Folio from the Aberdeen Bestiary with the eagle. England ca. 1200. Aberdeen UL, Ms. 24, fol. 61v

Readers and performers could adopt these gestures for a wide variety of manuscripts. In the Aberdeen Bestiary, for example, someone has physically reenacted the eagle diving into the water to catch a fish (Fig. 7).12 It appears that the reader wetted a finger first, as if to add liquid verisimilitude to the splash. Accordingly, the bestiary could have been read aloud to an audience: it was the nature documentary of its time. For the current volume—unpacking the role of the book in social interactions—touching the image in the service of dramatizing its contents plays an outsized role.

Aggressive poking

When book users attacked figures, they often targeted the eyes.13 Many employed sharp instruments to help them pinpoint this facial detail. Deliberate defacing of certain figures, particularly their eyes, reflects active engagement, possibly a form of moral or personal disagreement. Users attempted to reverse the narrative by attacking the depictions of attackers, thereby helping heroic characters vanquish their enemies. One example can be found in a tenth-century hagiographic manuscript containing an illustrated Passion of St Agatha (Paris, Bibl. Nat., MS lat. 5594), where a user has attacked selected figures.14 In the scene depicting Agatha resisting corruption at a brothel, the user has rubbed out the faces of the brothel manager Aphrodisia and her nine daughters and then gouged out their eyes with a needle or an awl, leaving them “blinded”: only the Christian Agatha can see.15 The reader’s micro-destructions are most evident when the page is viewed with transmitted light (Fig. 8). If this needling took place in a communal setting—during a public reading at a shrine, for example—it could have served to help audiences to rally around the lives of female virgin martyrs, and to prompt the listening community to join in and appreciate the destruction.16 The prelector’s actions could thereby shape the moral attitude of the audience.

Fig. 8 St Agatha resists temptation in a brothel, from the Passion of St Agatha. Paris, BnF, Ms. lat. 5594, fol. 67v, photographed with backlighting, and detail

Wiping with a damp cloth

This action conveys both reverence and rejection, depending on context. As with scraping, the technique of wiping an image with a damp cloth could be used to loosen paint in order to ingest it. Inversely, such an action could also be used to obliterate sections of text (for example, during the early years of the Reformation) or images (such as a previous owner’s coat of arms).

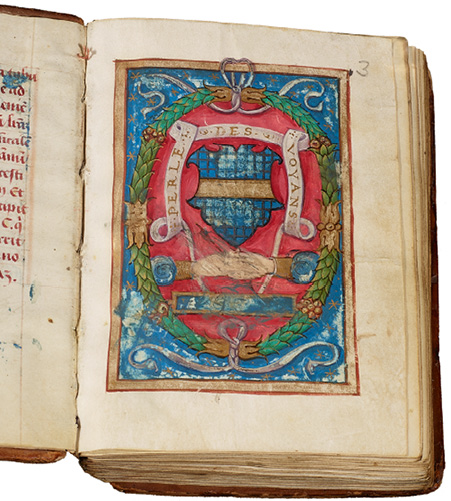

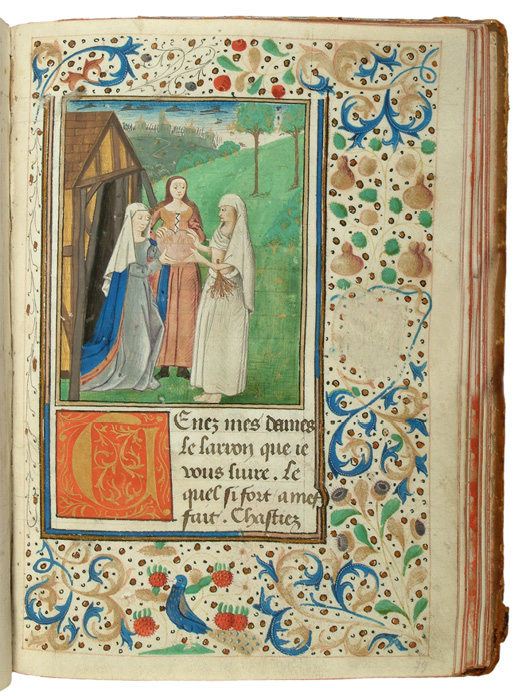

Fig. 9 King René presenting his work, Mortifiement de vaine plaisance (The Mortification of Vain Pleasure), to the archbishop of Tours. France, last quarter of the fifteenth century. Séminaire de Tournai, Ms. 42, fol. 1r

One motivation was damnatio memoriae—that is, expunging someone from the record so that future generations would not remember him. While most of the examples in this volume relate to social groups reading a manuscript simultaneously, damnatio memoriae implies a diachronic aspect: it implies control over individuals in the future. The owner of a copy of the Mortifiement de vaine plaisance (The Mortification of Vain Pleasure), a text written in 1455 by René d’Anjou (Séminaire de Tournai, Ms. 42; Fig. 9), may have been the object of damnatio memoriae. René d’Anjou was not only a king of Sicily but also an accomplished painter and author, whose writings were consumed by fellow members of the court. He completed another book two years later, Le livre du cueur d’amours espris (The Book of the Love-Smitten Heart).17 The first image in this manuscript depicts, or rather, depicted, King René offering his creation to the archbishop of Tours. Someone has deliberately sponged off the coat of arms in the lower border, and the decorated initial, which may have also contained a coat of arms. King René offers an allegorical story, built around illustrated vignettes, in which the soul encounters various challenges. In one episode, the soul surrenders her heart to fear and contrition (Fig. 10). As on the first folio, the coat of arms has been removed from the margin, this time with a blade. As is clear from these actions, someone wanted to obscure the identity of the manuscript’s original owner. It is especially difficult to locate such destructive acts in time.

Fig. 10 Image from Le livre du cueur d’amours espris (The Book of the Love-Smitten Heart), depicting the soul encountering fear and contrition. France, last quarter of the fifteenth century. Séminaire de Tournai, Ms. 42, fol. 79r

Tactile curiosity18

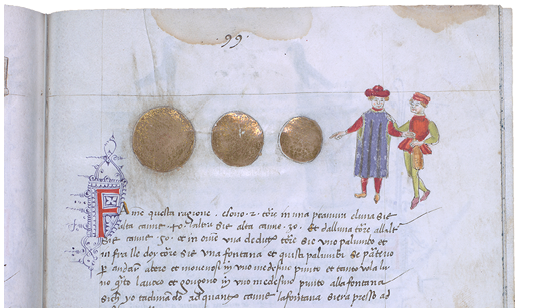

Touching certain areas of the manuscript, especially those with contrasting textures, points toward human curiosity, a desire to physically explore intriguing elements.19 Areas of burnished gold and fields of patterned relief invite tactile exploration. Evidence from use wear reveals that people were drawn to touching the gold that often appeared in initials and in decorations emanating from them. An amalgam of devotion and material pleasure motivated this touch. While some wanted to touch the word of God out of devotion, others may have caressed the gold-encrusted letters out of fascination for their metallic surface texture. An Italian treatise of the fifteenth century, which presents practical math problems, may have been touched out of curiosity (Fig. 11).20 The problem set out in this opening concerns the masses of three gold balls (pale d’oro), where the trick is to cube (not square) the radius of each, since they are volumetric (not planar). A user has rubbed the largest of the balls, abrading the foil surface and feathering the pigment into the void.21 Did this person have a magpie’s fascination with shiny objects? Was he calling forth riches? Or was he simply curious about the contrasting textures?

Fig. 11 Folio from an illustrated treatise on commercial and practical arithmetic with a problem about the volume of spheres. Italian, fifteenth century. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Library, Schoenberg Ms. 27, fol 99r

Speech acts

Inscriptions, ownership notes, and signatures reveal a manuscript’s role as a vessel of identity, authority, and contract. Book owners frequently added a note of ownership, asserting “This book belongs to me.” They could also sign documents to add the weight of their authority, sometimes signaling “This was signed by my own hand.” In the case of contracts, they could make a mark to signify a promise, such as a pledge to pray for the deceased (as with mortuary rolls), or a profession of obedience. All of these forms of language constitute “speech acts,” as philosopher J.L. Austin formulated them.22 These are forms of language that (purport to) change the world by their very utterance. Such acts of inscription are meant to be indelible and form part of a visible contract.

Each of the activities outlined above results in distinct forms of wear. By naming and distinguishing these patterns of destruction, we can better understand the physical role books played in forming social bonds. In short, the method practiced here considers operations performed on books as cultural techniques that left traces.23 Treating them in this way opens up the possibility of analyzing manuscripts, folios, images, texts, and decoration in the context of socially-coded performances.

1 Life of St Edward the Confessor (MS Ee.3.59). For a description and images, see https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-EE-00003-00059/64

2 Robert Bartlett, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? Saints and Worshippers from the Martyrs to the Reformation (Princeton University Press, 2013), p. 244.

3 Rebecca Browett argues that some institutions created contact relics because they hesitated to allow pilgrims to touch primary relics. See Rebecca Browett, “Touching the Holy: The Rise of Contact Relics in Medieval England,” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 68(3) (2017), pp. 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022046916001494

4 See Marc Bloch, The Royal Touch: Sacred Monarchy and Scrofula in England and France, trans. J. E Anderson (Routledge, 2020).

5 Three important studies on the use of Gospel manuscripts are: Eyal Poleg, “The Bible as Talisman: Textus and Oath-Books,” Approaching the Bible in Medieval England (Manchester Medieval Studies) (Manchester University Press, 2013), pp. 59–107; and David Ganz, “Touching Books, Touching Art: Tactile Dimensions of Sacred Books in the Medieval West,” Postscripts, 8(1–2) (2017), pp. 81–113; David Ganz, “Der Eid auf das Buch. Körperliche, materielle und ikonische Dimensionen eines Buchrituals,” Das Buch als Handlungsangebot: soziale, kulturelle und symbolische Praktiken jenseits des Lesens, eds. Ursula Rautenberg & Ute Schneider (Anton Hiersemann Verlag, 2023), pp. 446–469

6 For a late fourteenth-century Italian missal with images illustrating the priest’s rituals (New York, Morgan Library and Museum, Ms. G.16), see Roger S. Wieck, Illuminating Faith: The Eucharist in Medieval Life and Art (Morgan Library & Museum, 2014), cat. 17.

7 For a thoughtful perspective on Islamic and other traditions, see Christiane Gruber, “In Defense and Devotion: Affective Practices in Early Modern Turco-Persian Manuscript Paintings,” in Affect, Emotion, and Subjectivity in Early Modern Muslim Empires: New Studies in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Art and Culture, Kishwar Rizvi (ed.) (Brill, 2017), pp. 95–123.

8 In making this emphatically materialist argument, I am not arguing that medieval reader/users maintained awareness of the sources of their books’ skins, or even of its animal nature. Although they may have noticed the difference between crisp bovine parchment and much floppier ovine parchment, my approach does not rest on their cognition of a distinction between these materials. My method therefore departs from that of Sarah Kay, which she first discussed in “Original Skin: Flaying, Reading, and Thinking in the Legend of Saint Bartholomew and Other Works,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 36, no. 1 (2006): 35-74, and fully worked up in Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries (University of Chicago Press, 2017). My thinking is closer to that of Nancy K. Turner, “The Materiality of Medieval Parchment: A Response to ‘The Animal Turn,’” Revista Hispánica Moderna 71, no. 1 (2018): 39-67.

9 Literary theorist Gérard Genette coined the term to refer to all the material and marks that surround the text. See his Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (University of Cambridge, 1997).

10 For a thorough discussion of this manuscript, see Milvia Bollati, Flora Cassen and Marc Michael Epstein, with an introduction by Christopher de Hamel, The Lombard Haggadah (Les Enluminures, 2019). Comparable stains appear in the fifteenth-century Hileq and Bileq Haggadah (Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333), for which see Adam Cohen’s essay: https://smarthistory.org/the-hileq-and-bileq-haggadah/ Gertsman, Elina, and Reed O’Mara, in “Wrathful Rites: Performing Shefokh ḥamatkha in the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah” Religions 15 (2024), no. 4: 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040451, discuss this manuscript in its performative context.

11 Van Dijk also transcribes the motto, “Perla des voyans” (which may be repeated on the binding as PDVA). See S.J.P. Van Dijk, Handlist of Latin Liturgical Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, 8 vols. (typescript created 1957–60), Vol. 4: Books of Hours, p. 214.

12 The Aberdeen Bestiary, made in England around 1200, has been fully digitized: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/. For the manuscript in its European context, see Elizabeth Morrison with Larisa Grollemond, Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019).

13 David Freedberg, “The Fear of Art: How Censorship Becomes Iconoclasm,” Social Research, 83(1) (2016), pp. 67–99, esp. pp. 74–76. Those who attack figurative images in other media, such as sculpture or monumental painting, likewise often attack the eyes. Freedberg touches upon these ideas in The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (University of Chicago Press, 1989).

14 Magdalena Elizabeth Carrasco, An Early Illustrated Manuscript of the Passion of St. Agatha (Bibl. Nat, Ms Lat. 5594), Gesta, 24(1) (1985), pp. 19–32 discusses this manuscript and notes its intentional damage.

15 This situation is comparable to one described in Michael Camille, “Obscenity Under Erasure: Censorship in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts,” in Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages (1998), pp. 139–54, here p. 143.

16 A vita of St Margaret, in which the saint’s tormenters have been abraded, may have also been used at a shrine in a similar way (LBL, Egerton 877). See John Lowden’s keynote address at the conference Treasures Known and Unknown, held at the British Library Conference Centre, 2–3 July 2007, http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/TourKnownA.asp, unpaginated.

17 Dominique Vanwijnsberghe, “Séminaire de Tournai: Histoire, Bâtiments, Collections,” Monique Maillard-Luypaert (ed.), Institut royal du patrimoine artistique (Peeters, 2008), pp. 124–126.

18 James Hall, “Desire and Disgust: Touching Artworks from 1500 to 1800,” in Presence: The Inherence of the Prototype within Images and Other Objects, Robert Maniura and Rupert Shepard (eds) (Ashgate, 2006), pp. 145–60, also acknowledges curiosity as a motivation to touch images.

19 Modern viewers of manuscripts, including those who primarily encounter them through a digital proxy, miss the tactile experience that contributes to the encounter. As a result of this, research groups have tried to recreate the tactilily of the manuscript artificially. See Kristen Gallant and Juan Denzer, “Experiencing Medieval Manuscripts Using Touch Technology,” College & Undergraduate Libraries, 24(2–4) (October 2, 2017), pp. 203–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2017.1341358

20 Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Library, Schoenberg Ms. 27. I thank Larry and Barbara Schoenberg for letting me study this manuscript in their home in 2007. Their collection is now housed at the University of Pennsylvania. For a transcription of the text, see Pietro Paolo Muscarello and Giorgio Chiarini, Algorismus. Trattato di aritmetica pratica e mercantile del secolo XV, 2 vols (Banca Commerciale Italiana, 1972), Vol. II, p. 227.

21 The water damage at the top of this folio is separate from the abrasion of the ball.

22 J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words (The William James Lectures) (Clarendon Press, 1962).

23 In using this term, I pay homage to Bernhard Siegert and my time at the IKKM. See Bernhard Siegert, Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (Fordham University Press, 2015). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt14jxrmf.