7. Colour, Taste and Food

©2025 Bregt Lameris, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0380.10

Colour and Taste

Technicolor for Industrial Films was not the first film to emphasise the sensuous effect of colour on the representation of food. In 1939 Buster Keaton recalled the way Adventures of Robin Hood depicted ‘roast meats in the forest banquet’, giving him visions ‘in insomniac hours’ of the ‘suckling pig turning on the spit’ (Higgins, 2007b: 2). Even Rudolf Arnheim (1956 [1954]: 273), who had not always spoken in favour of mimetic colours in film, believed food looked better in colour than in black and white. As a result, filmic representations of food in colour were (and are) believed to have an increased cross-modal effect. In her book Tiger in the Smoke (2017) Linda Nead explains that during the 1950s colour and food became a much-used combination in printed media advertisements. She connects the appetite for food in colour to the ending of fourteen years of food rationing due to the war. As a result: ‘food and colour became, in equal measure, symbols of abundance and of the end of austerity and self-denial’ (142). Imagining the taste of food when one is hungry makes it easier to understand the impact of coloured representations of food in a period following a time of food scarcity and hunger.

The importance of colour in stimulating appetite was something the ‘colour influencer’ of the period, Faber Birren, also noted in his 1945 Selling with Color, in which he explained which colours were regarded as the most ‘edible’ and therefore the best for restaurants to use. These were ‘warm red, orange, a pale yellow, peach, a light green, tan, and brown’ (Birren, 1945: 125). In 1950 he wrote something similar in Color Therapy and Color Psychology, this time calling these colours the ‘true appetite colors’, adding that everyone is sensitive to the colour of food, which has an almost direct effect on appetite. He reiterated this belief in the 1963 version of the book, stating: ‘Color is forever a part of food, a visual element to which human eyes, minds, emotions, and palates are mighty sensitive’ (186).

This implies that a monochrome representation of food indicates a lack of sensuousness, of feeling. The film Sedmikrásky (Daisies) (1966, Chytilová), which tells the story of the subversive adventures of two young women (both called Marie), occasionally shifts from a mimetic colour scheme to a monochrome one, playing with various layers of cross-modal effects. This technique creates the surprise of a sudden change in colour scheme, as discussed in Part I. For example, a sudden shift from black and white to mimetic colour during a scene at the end of the film indicates a heightened sensuousness and an increase in cross-modal transfer. The Maries find themselves in an empty room where a large buffet sits unattended. First, we see them, in black and white, carefully exploring the room and all the dishes on the table with little cries of awe and joy, sniffing, tasting and caressing the food. Gradually, they start to pick up and nibble tiny pieces of food, warning each other to ensure no one will notice. By the end of the black and white part of this scene, however, they have thrown caution to the winds and started to feast on the banquet before them. As soon as the Maries decide to serve themselves heaped plates of food, the scene seems to demand colour. And indeed, the moment that one of the girls knocks a glass over, with a shattering sound that resonates around the room, the scene turns from monochrome to colour. Immediately after this switch, a brief sequence of shots pans over the colourful dishes of food at a fast-edited pace, presenting the audience with the full banquet in all its sensuous glory. Before the real gastronomic orgy begins, one Marie asks the other if she has already eaten something green, emphasising the shift to colour and its importance to the rest of the scene [Figs 7.1–7.2].

Figs 7.1 and 7.2 Buffet scene in Sedmikrásky (ČSSR 1966, Vera Chytilová) shifts from black and white to colour. DVD: 2012 Criterion.

|

|

|

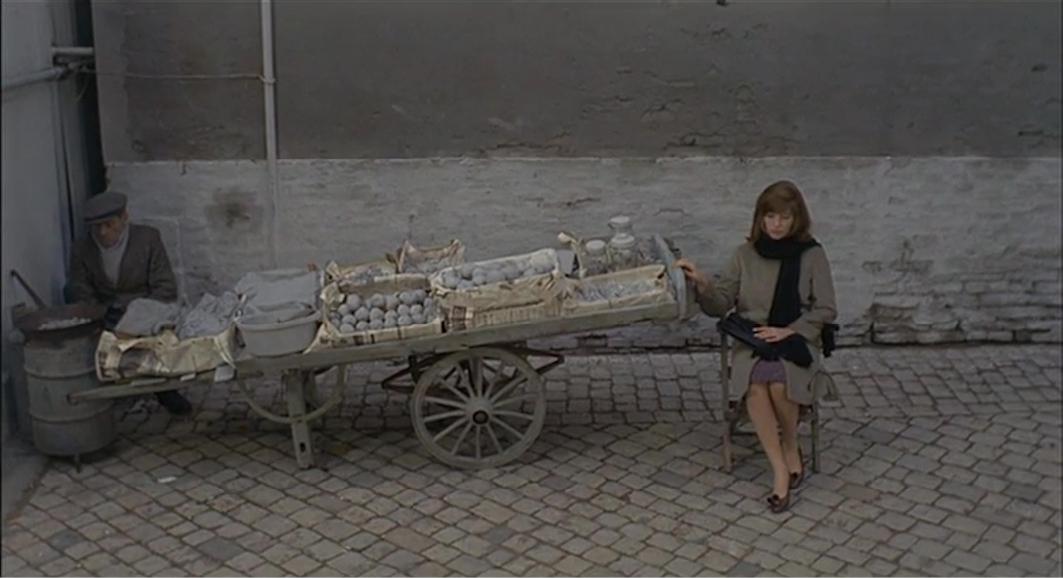

In the black and white part of the scene, by contrast, the food is presented in a rather neutral way; its visual representation lacks any cross-modal appeal. During the first half of the twentieth century, health and hygiene were conventionally associated with the colour white, as seen in the white uniforms of nurses and street cleaners, sterile white lab coats, and white foodstuffs such as milk, crackers and bread. Of course, the food industry used whitening products to create this ‘healthy’ appearance, which therefore was not that healthy. This aesthetics of the ‘simple supper’ was related to ‘the Protestant ethic of monochrome clothing and minimal sensory stimulation’ (Ross, 2014: 158) that not only found its way into fascist discourses of purity, but also into the modernist aesthetics of simplicity and clarity. The minimal sensory stimulation of colourless food was also used by Michelangelo Antonioni in Il deserto rosso (1964) to visualise the main character Giuliana’s disengagement from the world. When she is shown sitting next to a stand of vegetables painted white, it becomes clear that she can no longer experience the sensuousness of life. In this case, the film’s use of minimal sensory stimulation (the white vegetables) does not represent hygiene but reflects instead Giuliana’s low sensory potential, the emotional impotence caused by her descent into depression [Fig. 7.3].

Fig. 7.3 Black and white food as a subjective reference to Giuliana’s emotional numbness in

Il deserto rosso (ITA / FRA 1964, Michelangelo Antonioni). DVD: 2010 The Criterion Collection

The Fraught History of Food Dyes

Colourful food, then, was associated with high sensory appeal (Ross, 2014: 157), and the idea that food and colour are strongly connected is confirmed by the long-lasting tradition of food dyes. Adam Burrows elaborates on this history in his article ‘Palette or palates’ (2009), in which he claims that although food dyes can help increase appetite and inform the sensation of taste, they can also produce quite the opposite effect. In an interview with Judy Hevrdejs, Nicki Engeseth, an expert in food science and human nutrition, comments on the important role that sight plays in the imagination of taste:

People are strongly influenced by perception based on sight. […] If you put yellow food coloring in vanilla pudding, before they even taste it, they will think it will be lemon or banana. They will tell you it is lemon or banana even after tasting it because they are so strongly perceiving it as lemon or banana. (Engeseth in Hevrdejs, 2000)

This is indeed one of the cross-modal reactions that an infant’s neural system develops during the first year of its life. Object recognition starts when a child acquires the ability to combine various types of information—in this case, colour and taste.

The general hypothesis is that food colouring started around 1500 BCE with the use of saffron, paprika, turmeric, beet and flower petals as colourants. As the ingredients were rare and of relatively weak potency (meaning large quantities were necessary), coloured food was mostly a luxury for the rich. At the beginning of the Renaissance, colour indicated that food was nutritious and healthy—since medieval times, chalk, lime or crushed bones had been used to make bread appear fresh, while butter was coloured yellow to make it look rich. These practices, however, were occasionally regarded as criminal activities, since they were in fact used to deceive customers. In the late eighteenth century, the first chemical dyes emerged, and these were also applied to food. In 1820 many of these dyes were recorded in a publication called A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, written by an English chemist, Friedrich Christian Accum. Especially shocking is Accum’s exposition of the everyday use of poisonous substances such as copper to dye pickles green and other colourants containing mercury, lead, copper and arsenic to produce coloured sweets for children (Burrows, 2009: 395). The first Food Adultery Act in the UK dates from 1860, and was followed over the years by similar laws, including a new Food and Drugs Act. In the US, legislation only came into force in 1906 with the Wiley Act, which banned toxic colourants in food and regulated (with a very light touch) the use of coal-tar dyes such as aniline (396).

When hundreds of children were hospitalised in the USA in the early 1950s after eating Halloween candy and popcorn containing FD&C Orange #1, which at the time was deemed safe to consume, the event ushered in a new era of debate over the safety of food dyes. During the 1950s and 1960s, the use of coal-tar dyes as food colourants was subject to investigation, and they were occasionally taken off the list of safe colourants. The discussion became more vehement when cancer became part of the debate (Burrows, 2009: 401–03; ‘The history of food colour additives’, ca. 2008), coinciding with an increase in criticism over the use of convenience foods such as frozen dinners, fast food and processed food with artificial flavours and colours (Howes, 2019 [2014]: 17). This counterreaction emerged from the hippy culture of the second half of the 1960s:

[There was a] desire for a more ‘spiritual,’ ‘natural,’ ‘environmentally sound,’ and ‘ethical’ diet. Synthetic, industrially produced foods were rejected (at least in theory) in favor of natural or organic foods, which were touted as both healthier and more flavorful (Howes, 2019 [2014]: 8).

In all, brightly and especially unnaturally coloured food such as candy was increasingly viewed with suspicion. This might explain the emphasis on colour in Birren’s discourse on how food should be displayed for sale, or in the voice-over commentary on the film Technicolor for Industrial Films which underlined the importance of using ‘natural’ colours when filming food.

Burrows (2009) describes those colours rarely found in natural food, such as blue, as far less appetising, even to the point of causing a loss of appetite. We need only recall the blue leek soup in the film Bridget Jones’s Diary (UK 2001, Sharon Maguire); this would not be such a successful joke if blue was not considered inedible. Birren also saw blue as particularly unappetising: he stated that it was not a good colour for food, confirming that the aversion to blue food was also prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s. According to Burrows (2009: 394), however, colours that were considered unfit for ‘normal’ or ‘healthy’ food could be found in ‘fun’ food, such as candy, cake, chocolate, chewing gum and fizzy drinks. This was confirmed by Birren (1950: 167; 1963: 190), who writes that tints of blue and pink are ‘sweet’, and that sweets and candies could therefore be any colour.

It is this aspect of colourful food in film that Scott Higgins discusses in his article ‘Technicolor confections’ (2007). Focusing on the 1930s, he argues that—with the exception of Adventures of Robin Hood’s roasted meat that so appealed to Keaton’s palate—it was precisely the artificial colouring of sweets, cakes and cookies (which began during this period) that found its way into cinema. He mentions two short animated films in Walt Disney’s ‘Silly symphonies’ series called The Cookie Carnival (USA 1935, Ben Sharpsteen, Technicolor IV), and Funny Little Bunnies (USA 1934, Wilfred Jackson, Technicolor IV) as examples. He also analyses Technicolor scenes in other black and white films such as the final scene of Kid Millions (USA 1934, Roy Del Ruth, Technicolor IV), which is a feast of coloured candy, and the party with the pink cake in The Little Colonel (USA 1935, David Butler). Taking up the sweet theme of these films (and adopting Tom Gunning’s ideas on colour in early film), Higgins calls their colours ‘eye candy’, a ‘superadded quality’ that increases ‘sensual intensity’ (Higgins, 2007: 275). He connects this to Gunning’s concept of the ‘cinema of attractions’, which was characterised by its direct address to the viewer’s senses through movement, beauty, thrills, fear, and other attributes. In these films, Technicolor used colour for the potency of its attraction through the gustatory senses.

In the films of the early 1950s, such examples of ‘chemical’ and sweet colours mainly appear in relation to cakes. For example, in The Long, Long Trailer (USA 1953, Vincente Minnelli, Ansco Color), we see a very pink wedding cake, and in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), Kathy jumps out of a huge pink-and-green cake. The pink dresses of Kathy and the girls in her chorus, as well as the green dress Lina is wearing, perfectly match the colours of the cake, indicating that the cake and the dresses might have been coloured with the same (coal-tar?) colourants. As a result, the film links enjoyable food with the sensuality of female bodies, using colour as a signifier [Fig. 7.4].

Moving into the 1960s, we encounter other, more ironic representations of food and artificial colours. For example, in Pierrot le fou (1965), Jean-Luc Godard comments on the artificial colours of filmic cake. Early in the film, the main character Ferdinand lingers around at his wife’s birthday party, whose strange atmosphere is emphasised by monochrome lighting. The way people appear to be talking in advertorial catchphrases serves to underline the sterility of his married life, controlled as it is by the urge to earn money and partake in the consumer culture that Godard was known for criticising.1

By the end of the scene, he moves towards a group of people who seem to be gazing at something in awe, pushing the crowd aside to expose what they are looking at: a huge birthday cake out of which a woman bursts. Ferdinand reacts by grabbing a handful of the cake and throwing the creamy substance in his wife’s face, an action that is immediately followed by a burst of fireworks. What is interesting about the cake scene is the way multicoloured lights play over the crowd. Clearly, a different light source was used for each separate colour, and the light itself comes from multiple directions, projecting colourful shadows on the wall behind [Fig. 7.5]. The colours created by this lighting lend the scene an air of hyper-gaudy artificiality, which—in combination with the cake with the woman hidden inside—cannot be anything but a reference to the overly sweet fakery of the entertainment industry and consumer culture that was already referenced in the texts during the preceding sequence. Ferdinand, by destroying this token of consumer and entertainment culture, announces that he is breaking free from this emotionless life tied to keeping up appearances.

As mentioned above, during the 1950s and the 1960s the legal response to food colourants entered a new era. Among other things, this meant that both Europe and the USA saw a centralisation of legislation and regulation. In 1962 the six founding countries of the European Community—Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany—released the first Directive on Food Colours, which listed the colour additives deemed safe to use in food (Lüdzow, 2006). Meanwhile, the USA Congress passed the Color Additive Amendments on 12 July 1960, which gave the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) control over all colour additives. These changes directly affected daily practice by listing colour additives that were considered safe for human consumption, automatically excluding all colourants that were not mentioned in the list. The European Directive allowed 36 colours, of which 20 were natural colours and 16 synthetic (‘History of food colour’, ca. 2008). And across the Atlantic, the FDA began a comprehensive round of approval or rejection of all colourants on the market. Of around 200 dyes placed on a provisional list, the FDA declared only 90 safe to consume (Burrows, 2009: 401).

Not only did these laws intervene in daily practices related to food, they also produced a certain discourse of fear around synthetic food colourants. Forbidding the use of some as unfit for human consumption gave people a sense of security, but it also reminded them of the fact that food dyes can be poisonous, and because of their chemical origin, artificial—even in modern times. This direct link between chemistry and colour is a trope that we see in various cultural forms, especially as dyes were produced from coal. This is visualised, for example, in To Spring (USA 1936, Hugh Harman; Rudolf Ising, Technicolor IV), where the colours of the new spring are extracted from mined stones in an underground laboratory. After the stones have been processed into dyes, they are sent up to the surface through a system of test tubes that also resemble a colour organ.

We can see this theme of chemical colours in the film Lover, Come Back (1961), which we have already discussed in relation to colour control (and loss of control) in Chapter Five. The colours in the film are also shown in the process of creation: just as in To Spring, the chemist’s basement laboratory is full of test tubes and glass jars containing coloured fluids, with occasional small explosions producing clouds of coloured smoke. The chemist finally develops brightly coloured candies that have a similar effect on people as alcohol or drugs. The bright colours of this chemically produced food have connotations of artificiality, entertainment and consumerism, similar to those of the cake in Godard’s movie. Both examples push the colours of candy and cake more towards the extreme than the earlier examples of films from the 1950s. On the one hand, this was possibly due to the fact that these films were released after food colour legislation was centralised (and professionalised) in the USA and Europe, re-emphasising that the colourants used in food could be poisonous and needed to be regulated, strengthening the negative discourse on dyed food. On the other hand, colour culture had begun to take a psychedelic turn, symbolised by the use of even stronger, brighter and more gaudy colours than before. As such, the production of VIP might be an implicit reference to the chemically produced drug LSD, which unleashed the potential of colour perception within the mind. The almost hallucinatory display of colourful candies mirrors the effects of LSD and the colour culture associated with it, as I discuss in the last chapter. Besides, LSD was already well known in Hollywood in the early 1960s due to its therapeutic use in medical contexts, including in clinics that were frequented by famous actors such as Cary Grant.

Colour Change and Decay

In a scene in Playtime (1967), Jacques Tati plays with the way coloured lighting changes the appearance of food. The setting is a bar located next to a pharmacy that advertises its presence with a large green neon cross (as is the norm in France), and Tati’s joke is built on the way the neon sign sheds its greenish light on the bar’s display of prepared dishes, transforming them into something that is not immediately recognisable as food. Arguably, as pharmacies are one of the main signposts of the chemical industry in society, the colour the sign radiates could be a reference to the chemical colourants that not only turn food into something playful and ‘fun’, but also into a substance that can be poisonous, even lethal. In this case, the change in the food’s colour also diminishes its appeal; it is no longer appetising. This is confirmed by M. Hulot’s reaction—he looks at the food in perplexity, leaning in close to smell it to make sure it has not gone bad. Clearly, the strange green colour gives it the appearance of rot and decay. The look on his face reveals to the audience that the colour of the food has turned it into a suspicious entity, something that could very well be disgusting [Figs 7.6–7.7].

Figs 7.6 and 7.7 Green coloured light turns the food in Playtime (FRA 1967, Jacques Tati) into something rather undesirable. DVD: 2001 The Criterion Collection.

|

|

|

Time code: 01:17:18 |

For a better understanding of food colour and decay, it is worth visiting Eugenie Brinkema’s ingenious analysis of the film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (GBR 1989). Director Peter Greenaway’s use of colour very cleverly gives the impression of decay, degeneration and putrescence. Brinkema (2014) points out that the dress ‘Georgina the Wife’ is wearing changes colour according to the different decor and spaces of the film’s diegesis, and links the instability of dress colour to the notion of decay, referring to Aurel Kolnai’s 1929 theories on the sensation of disgust. One of Kolnai’s main conclusions was that disgust is provoked by objects in the process of deterioration or putrescence, which is indicated by a change in quality such as a ‘variation in coloration, often glaring, as in the greening spread of mold’ (Brinkema, 2014: 170). It is the changing state of an object—the transformation in its ‘Sosein’ (or ‘so-being’) as Kolnai calls it—that turns it into something that we find ‘disgusting’. This ‘so-being’ is, among other things, connected to the object’s colour: when green-coloured light grazes the food in Tati’s Playtime, changing its appearance, it also changes its ‘so-being’, turning it into a strange object that is probably not good to eat. Greenaway in The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover gives food such as poultry, vegetables and fruits a similar greenish tinge, lending it an unappetising appearance. This effect is strengthened by the complementary contrast with the red of the background [Fig 7.8].2

Fig. 7.8 A similar combination of green light and food can be found in The Cook, the Thief, his Wife and her Lover (GBR 1989, Peter Greenaway). DVD: 2003 Universal Studios. Time code: 00:12:51

If we take into account the correlation between colour, food and disgust, it is not so surprising that in 1957 filmmakers were advised to avoid using coloured light on food:

Except for intentionally bizarre effects, colored light is seldom used on faces or food, since most people are especially critical of the color rendition of such subjects. A green face or a purple slice of bread, for example, is almost intolerable. (Holm, 1957: 76)

This advice, however, was increasingly ignored during the 1960s. In contrast, although Sedmikrásky directly confronts us with food that is indeed in a state of decay, the first time our attention is drawn to the rotting food is through the rendition of the sense of smell as we watch one of the Maries walking around the banqueting room sniffing the dishes, rapidly followed by an image of sour milk, eggshells, half-empty glasses, wine bottles and other detritus. Later in the film we are presented with images of watermelons, whose fresh pink colour has been replaced by whitish-grey mould [Figs 7.9–7.10].

Figs 7.9 and 7.10 The fresh pink of the watermelons is replaced by whitish-grey mould in Sedmikrásky (ČSSR 1966, Vera Chytilová). DVD: The Criterion Collection 2012.

|

|

|

|

Time code: 00:39:58 |

Time code: 00:55:13 |

Sedmikrásky indicates decay in its simple, unvarnished, unappealing form without the use of coloured light or dyes; the food actually loses its colour as it rots, creating a parallel to the colourless food shot in black and white earlier in the film.

Controlled Food Compositions

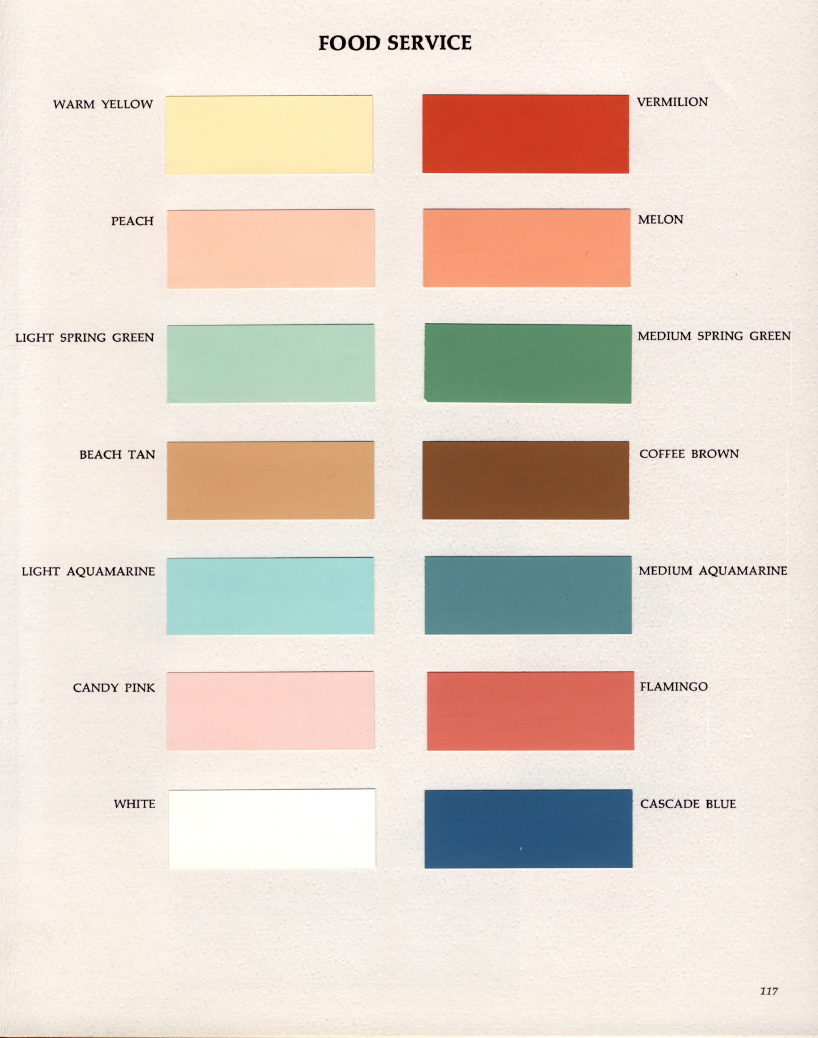

In Color Therapy and Color Psychology (1950), Birren focused on composition and particularly on which colours to use as a backdrop for a harmonious and attractive food display: for example, he considered blue to be the perfect background colour. He returned to the subject in 1963 with the publication of a colour chart laying out the colours suited to backgrounds or accents in spaces where food was sold or served. True to form, he claimed that this advice was based on research into the psychological associations between food and colour—without supplying any scientifically sound references (Birren, 1963: 116) [Fig 7.11]. Aquamarine, he tells the reader, will, ‘by direct visual complementation, give meats a pinker and more appetizing look’. And, he continues, sometimes coloured lighting such as pink for meat and green for vegetables can be used to illuminate the food sections in supermarkets to emphasise the natural colours of the products. Finally, he lists the colours that are supposed to be poor for the representation of food: ‘purplish reds, purple, violet, yellow-green, greenish yellow, orange-yellow, gray and most olive and mustardy tones’ (190).

Fig. 7.11 Colour advices for the presentation of food in Birren’s Color for interiors (1963: 116).

As we have seen, one of the places Birren targeted with his colour advice was the food store or supermarket: the right use of colour, he claimed, would put the customer at ease and help increase sales. Around this time, suburbs were emerging across the US, complete with standardised shopping malls, creating a visual predictability. These controlled spaces generated an atmosphere intended to entice housewives into buying and consuming; women, it was believed, were emotionally attracted to the sensuous, and thus could be seduced by smells, tastes and textures. Occasionally, this atmosphere even entered the realm of the sexual, ‘providing female shoppers an intimate private-like experience in a public space’ (Mack, 2014: 90). For instance, the grocery store Casanovas (the clue is in the name) used romantic lighting and music to sell its products, and its display of fruit and vegetables had strong sexual overtones, particularly in the way they were described as ‘plump’, ‘juicy’, ‘ripe’ or ‘ready-to-use’ (88–91). It seems that these sensualised ways of displaying food became normalised during the 1950s and 1960s, and so it is no surprise that some of these formulas combining food and colour found their ways into cinema.

In Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (USA 1968, Eastmancolor), the kitchen in the main character’s apartment is partially coloured and styled in the ‘warm yellow’ recommended by Birren’s colour chart. When Rosemary fries and eats a steak, this colour forms the background to the scene, which, according to Birren, should make the meat appear more appetising. Later in the film, the table is filled with seafood and other ingredients that stand out against the ‘warm yellow’ decor [Fig. 7.12]. These moments in the film show great care in the composition of the food and the way it combines or contrasts with the background colours. In a similar way, Les parapluies de Cherbourg (FRA 1964, Jacques Demy, Eastmancolor) pays close attention to the colour composition throughout the film, including the colour of food. At one point in the scene in which Geneviève has dinner with her mother in a salon wallpapered in pink and grey, we see her in a close-up with a lettuce leaf in her hand, its green forming a complementary contrast with the pink of her cardigan and of the wallpaper behind her—a perfect example of the film’s underlying aesthetic [Fig. 7.13]. Food in this film is mainly used as an element in the overall style of the apartment’s decor and the costumes of its inhabitants. Other scenes containing food simply display it in a decorative way without directly focusing on the act of eating.

|

|

|

Fig. 7.12 Birren’s ‘warm yellow’ as a background for food in Rosemary’s Baby (USA 1968, Roman Polanski). DVD: 2012 The Citerion Collection. |

Fig. 7.13 Green lettuce contrasts with pink walls in Les parapluies de Cherbourg (FRA 1964, Jacques Demy). DVD: |

Food as a decorative and compositional element has a long tradition in Western art and culture. Fruit bowls, for instance, are a reoccurring trope throughout the history of Western visual representation, and can be found in manifold paintings and drawings. We also find them in the earlier forms of colour film: one of the test films Gaumont made to display its three-colour system, Chronochrome, shows fruit and vegetables in still-life compositions [Figs 7.14–7.15]. Another early example is a Prizma II film housed at the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. Many of the decoratively set tables we encounter in films feature a carefully arranged bowl of colourful fruit.

Figs 7.14 and 7.15 Fruits were a fine topic to show off early film colour systems as we see here in Fruits (FRA 1912, Anonymous), https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=YvRPJvvcNtg

|

|

Figs 7.16 and 7.17 In Goldfinger (GBR 1964, Guy Hamilton) the camera pans from the beautiful display of food to the bed where Bond and a young woman make love. DVD: 2012 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios.

|

|

|

|

Time code: 00:13:45 |

Goldfinger (GBR 1964, Guy Hamilton, Technicolor V) contains just such a carefully composed display of food in James Bond’s hotel room: a nicely set table with a plate of salmon in pink and green, with red and orange details in the foreground, is flanked by a bouquet of flowers in perfectly matching shades of white, green and salmon pink. A fruit bowl forms the finishing touch. This image could in itself be used as an advertisement for a food provider of some kind [Fig. 7.16]. The plate of salmon, however, will not be eaten: when the camera pans from the beautiful display of food to the bed, it first reveals bare feet, then legs, and finally Bond and a young woman making love [Fig. 7.17]. Here, food and sex are linked—another topos of Western culture that enables implicit references to sex through the meeting of taste and touch.3 However, the 1960s Bond was sexual and seductive in a calm, composed way, never losing control, never sweaty or smelly.4 The composition of food as a visual rather than a haptic pleasure reflects the rational, synthetic, almost artificial creature that Bond is, as though he were a magazine cut-out.

In contrast, Sedmikrásky appears to mock the artificiality of 1960s advertising culture that Goldfinger mirrors, particularly in the scene in which the Maries start cutting up sausages, eggs and pickles with scissors, and then cutting photographs of food out of a magazine. These actions begin to merge when one of the Maries cuts up a real banana, holding it in such a way that it looks like an image from a magazine, and the other Marie starts eating the coloured images of food with an expression of delight, as if she can really taste the food in the photographs; however, watching her eat printed magazine paper produces in us not a similar delight but a cross-modal effect of touching and tasting ink and paper [Figs 7.18–7.19]. As a result, this scene not only overturns all conventions regarding table manners and the consumption of food, but also creates a moment of self-reflection, illustrating the power of photographic representation to create cross-modal transfer, while at the same time breaking the illusion and potential cross-modal effect of hunger or disgust (either is possible in this scene).

Figs 7.18 and 7.19 The Maries cutting (images of) food in Sedmikrásky (ČSSR 1966, Vera Chytilová). DVD: 2012 The Criterion Collection.

|

|

|

Time code: 00:35:02 |

Time code: 00:35:42 |

Presenting food in a balanced composition using the right colours and colour combinations is also closely connected to class distinctions. In 1939 Norbert Elias published a groundbreaking book, Über den Prozess der Zivilisation, a history of manners from the early modern times onwards. When it was later translated into English in 1969 under the title The Civilizing Process, Vol. 1: The History of Manners, the work gained widespread renown. Elias analysed the ‘increasing levels of self-restraint and self-control, especially with regards to violence, sexual behaviour, bodily functions, table-manners and forms of speech’ (Hailwood, 2015). A large part of his work focused on table manners and the sort of behaviour that was expected when eating in company, explaining how members of the higher social classes used these rules and regulations to elevate themselves above the rest of society. Simply put, the rich and educated tended to use table manners as a distinguishing characteristic to mark themselves out from the poor and uneducated.

This idea is in many ways connected to Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’, a concept we have already encountered in relation to the history of emotions. Habitus refers to the way we internalise the norms of our particular society or social group to the extent that they become automatic and embodied forms of reaction, behaviour and feelings. Thus, customary ways of handling food, for example, can be markers of social difference. Bourdieu illustrates this in Distinction (1996 [1984]: 195–96), explaining that working-class people handle their food with a freedom the bourgeoisie deem unacceptable.5

A film that contrasts upper-class with lower-class habits is Jacques Tati’s Mon oncle (1958). The film vividly exposes the differences between a popular part of Paris and a modernist, exclusive residential area inhabited by the rich. In the poorer area, food is sold in the street, and the rubbish and garbage bins attract stray dogs. Meanwhile, little Gérard lives with his parents in the modernist environment, and we see how artificial and boring his life is. This is encapsulated in the image of him eating his breakfast (an egg and a sandwich wrapped in plastic) by himself in an overly sterile white kitchen. In contrast, when he visits his uncle’s neighbourhood, he strolls around with a group of street boys. When they are hungry, they simply buy sandwiches at a food stall and sit down to eat them in the street [Figs 7.20–7.21].

Figs 7.20 and 7.21 Contrasting ways of food consumption in Mon oncle (FRA 1958, Jacques Tati). DVD: 2001 The Criterion Collection

|

|

|

Time code: 00:41:22 |

Time code: 00:47:57 |

Whereas Tati implicitly connects the consumption of food to class differences, table manners and class differences are literally thematised in Gigi (1958). Gigi, who is meant to become a high-class courtesan like her aunt and grandmother before her, visits her aunt Alicia once a week for lunch. While they eat, Alicia teaches Gigi table manners to facilitate her entry into the domain of the rich: she needs to learn how to deport herself and control her embodied reflexes if she is to become a rich man’s mistress. Every time they practise these table manners, the food is almost absent from view, concealed by a bouquet of flowers. The lesson includes instructions on how to cut up a quail without making a sound, and how to eat it without anyone noticing. By contrast, in Gigi’s home, food is touched, prepared, cooked, smelt and tasted, not only by Gigi and her mother, but also by Gigi’s future (rich) husband [Figs 7.22–7.23]. And yet all this earthly pleasure in food does not appear to tarnish the man’s upper-class status, whereas Gigi in this context remains a girl of working-class origins, without any real chance of entry into a higher class. Added to this, the fact that all the lower-class characters trying to climb the social ladder are female, while the higher classes are represented by men, indicates the particular way inequality impacts issues of gender.

Figs 7.22 and 7.23 In Gigi (USA 1958, Vincente Minnelli) the girl is taught table manners by her aunt, whilst her future husband eats from the pan at her mother’s kitchen.

|

|

|

Time code: 01:06:47 |

The visual representation of food in film, following the stylistic rules related to the traditions of painting and colour control, can thus be linked to class distinctions, implying that one of the marks of belonging to a higher social class is the ability to disconnect from your embodied self. When you eat, you should not draw attention to the fact; food should be presented in the right colour combinations and in tasteful compositions; and, finally, food should never be touched.

Subversion, Food and Touch

A number of films, however, offer scenes that directly contrast with the well-composed, stylised presentation of food in ‘tasteful’, non-sensuous ways. For example, when the pregnant Rosemary (Mia Farrow) in Rosemary’s Baby is eating raw, bloody liver in the kitchen, the scene is the polar opposite of the one showing seafood ingredients. Rosemary picks up the slippery, slimy liver with her bare hands and starts eating it with the relish of a hungry animal, a disturbing image. It produces several cross-modal effects, first seeing her touch the liver creates a haptic sense of touching this raw, cold and slimy substance. When she starts eating, a similar effect is created for the inside of the mouth, accompanied by a cross-modal experience of the metallic taste and smell of blood and liver. Indeed, when she glances up and sees herself mirrored in the toaster, her delight is replaced by disgust: she becomes the spectator of her own spectacle. The cross-modal effect created within Rosemary when she catches the reflection of herself eating the raw, red liver immediately dissipates her animalistic joy. At the same time, this action stimulates an alignment between the viewer and the character as both are physically affected by the act of looking: Rosemary exhibits all the characteristics of a physical reaction of disgust, producing a similar feeling in the viewer through contagion. The filmic strategies of visual representation induce in the audience a strong embodied reaction that is related to Rosemary’s devilish pregnancy that ‘forces’ her to eat raw liver in this disgusting way [Figs 7.24–7.25].

Figs 7.24 and 7.25 Rosemary disgusting herself when eating raw liver in Rosemary’s Baby (USA 1968, Roman Polanski). DVD: 2012 The Citerion Collection.

|

|

In addition, this fragment of film also shows us that red is not always appetising, as Birren (1950: 166–67) claimed; in the context of raw meat, it becomes disgusting. On the one hand, this indicates that cross-modal perceptions of colour and food are not part of our biological hardware; rather, they are incorporated reactions to the gradually evolving cultural connotations of a particular colour, combined with the rapidly changing context in which it appears. On the other hand, the way the monochrome surface of the meat is highlighted by a hard white light influences the way we perceive its colour (red) as moist and slimy, and therefore repellent.

During the 1950s, food was not often shown in such a tangible, haptic fashion in colour films. An exception is To Catch a Thief (1955), where eggs are treated in a way food is not supposed to be handled. First, an egg is thrown against a window as an act of aggression, and then the Hitchcockian mother figure stubs out a cigarette in the yoke of a fried egg left over from the hotel breakfast. In both situations the eggs’ slippery, unappetising aspect is emphasised to create a somewhat comical effect [Figs 7.26–7.27].

Figs 7.26 and 7.27 Eggs’ slippery, unappetizing aspect is emphasized to create a somewhat comical effect in To Catch a Thief (USA 1955, Alfred Hitchcock). DVD: 2012 Paramount.

Time code: 00:11:26

Time code: 00:40:47

Such actions, however, are small details in a film that otherwise treats sensuous moments implicitly (e.g. the fireworks symbolising sexual activity). Throwing food is of course a common theme in cinematic comedy: pushing a cake into someone’s face is part of slapstick tradition, which we also encounter in the 1950s in, for example, Singin’ in the Rain from 1952.

The second scene in the tale of Giulietta from the film The Tales of Hoffmann (GBR 1951, Michael Powell; Emeric Pressburger, Technicolor IV) is a remarkable exception to the limited hapticity of images of food in 1950s cinema. The scene takes place in the Venice palazzo of Giulietta the Courtesan, and drops the spectator right into the sensuousness of carnal pleasure that is associated with a brothel. While Hoffmann sings a song about how he could never be seduced into partaking in such pleasures, he walks into an orgy scene that combines food and sex, taste and touch in a particularly colourful way. The first thing Hoffmann does is position himself at the centre of a table loaded with food and drink—the food once again mimics the generic still-life fruit bowl, indicating that this is actually a high-class event. There are beds shaped like pieces of cake, arranged around the central dish, on which men and women are eating and having sex in very physical, sensuous, but also balletic and stylised ways. They wear extremely colourful make-up and their hair is dyed in an array of unnatural colours—green, red, blue and orange and pink—also giving them a resemblance to slices of cake [Figs 7.28–7.29].

Figs 7.28 and 7.29 Orgy scene in The Tales of Hoffmann (GBR 1951, Michael Powell; Emeric Pressburger) that combines food and sex, taste and touch in a particularly colourful way. DVD: 2005 The Criterion Collection.

|

|

This mixture of colours, food and bodies increases the sensuality and confusion of the scene, which could be interpreted as a representation of cross-modal transfer from taste to touch, and back again. It is interesting to note the difference with the earlier example from Goldfinger, in which sex and food are juxtaposed rather than merging and blurring as in the Hoffmann film. The scene passed the censors without any problems, even though on closer inspection it appears very physical and orgiastic. This might be due to the film’s allusion to high art, since it is adapted from the celebrated opera of the same name, or to the fact that Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger were filmmakers of high repute.

The way Hoffmann was treated by the authorities was very different to the fate of Sedmikrásky. Its female director, Vera Chytilovà, had studied philosophy and architecture, worked as a model and held many different jobs in filmmaking before attending the FAMU film school in Prague. With Sedmikrásky, she wanted to make a film that would allow her to get the very best from film language, to sweep aside its conventions and use it to express what otherwise could not be expressed. This resulted in a film that experiments with discontinuous spatiality and colour aesthetics. In 1967, however, the film was banned because, as the Czechoslovak National Assembly stated, it had ‘nothing in common with our Republic, socialism, and the ideals of communism’, and Chytilovà was barred from making another film for a full six years (Lim, 2001: 37–38).6 The film was classified as a celebration of bad behaviour, and it was believed that it might exert a harmful influence on women and children (Lim, 2001: 44).

One of the film’s main themes is the consumption of food. The two Maries are shown stuffing themselves with all kinds of dishes, fruit and snacks throughout the film. They also prepare food in unconventional ways: for example, setting their room on fire to grill sausages, producing the imaginary smell of smoke, which they then eat sitting on the bed; using forks to prick each other in the stomach, creating a cold and prickly sensation in the spectator’s belly; cutting up food with scissors; eating pickles out of a jar filled with green water (i.e. poisonous food dye) resulting in audience’s disgust; and bathing in soft, silky milk. All the conventions related to food are turned upside down, creating a cross-modal cacophony in a perfectly choreographed mess [Figs 7.30–7.32].

Figs 7.30, 7.31 and 7.32 In Sedmikrásky (ČSSR 1966, Vera Chytilová) food conventions are turned upside down. DVD: 2012 The Criterion Collection.

|

|

|

The climax of all this destruction comes in the aforementioned scene in which the Maries gatecrash a buffet prepared for some wealthy guests. After the scene turns from black and white into colour, they begin a gastronomic tour of the long table, filling up their plates, and mashing, eating, gorging, throwing and destroying the carefully prepared dishes of food. Their carousal ends with the trope of the cake fight, leaving them covered in cream and crumbs, after which they climb on top of the table and use it as a catwalk, sashaying through the devastation [Fig. 7.33].

Fig. 7.33 By the end of the film the Maries gatecrash a buffet prepared for some wealthy guests.

The fact that the Maries are shown trampling and crushing food brings us to another reason the deputy of the National Assembly Jaroslav Pružinec gave for banning the film. He attacked the depiction of ‘food orgies’ at a time when ‘our farmers with great difficulties are trying to overcome the problems of our agricultural production’ (cited in Lim, 2001: 43). However, it was precisely the food shortages that the scene is referring to as part of its overall critique of the political system in Czechoslovakia: the banquet the Maries destroy at the end is clearly prepared for rich, probably highly placed officials in the Communist Party. Film audiences would no doubt be experiencing hunger, and watching the two girls (one of whom is in her underwear) dancing on top of the food, they might indeed have interpreted the scene as a subversive act.

Sedmikrásky’s strong sensuous and cross-modal effects are described by film critic Guido Rohm, who nevertheless dismisses the social critique that has been read into the film:

[The film] is mostly beautiful, and jumps from behind a tree in front of our feet like a young girl, and invites us to follow her, so she can show us the Seeing and Tasting, the Smelling and Touching before it is too late.7 (Rohm, 2012, my translation)

This begs the question of why its critical message should have to be dismissed before the film can be interpreted as one that submerges us in an avalanche of sensations. Is it not precisely the sensuousness of the film that enhances its critical message? Is it not the way the female protagonists display their bodies, defying convention, that highlights the hypocrisy of ‘good table manners’ at a time of hunger and political crisis? They eat in bed in their underwear, stuff their faces with chunks of meat, drink like Cossacks, dance on the table, crushing the food under their feet, bathe in milk and cover themselves with cream and pie. All these actions evoke sensations of disgust, hunger or thirst through cross-modal transfer while emphasising the joyful physicality of the young women’s bodies in a way that violated the contemporary social norms of female behaviour and decency.

Sedmikrásky not only tells the story of two bored young women who want to subvert the inhibiting values of their restrictive society, but also displays their actions in an extremely sensuous, haptic way, making them resonate cross-modally with the audience. Hence, critics have claimed the film as a critical perspective on the world of male dominance, one that encouraged its audience to fight for the right to experience life in the fullest, most sensuous way possible.8 The two Maries’ disdain for the ‘acceptable’ way of handling food could be seen as a demonstration of female resistance against these behavioural rules and regulations. Even though Chytilovà declared it was not intended as such, Sedmikrásky could indeed be called a feminist manifesto, comparable to the work of other female artists and directors of the time such as Valie Export.

Chytilovà’s film fitted within an emerging movement of female artists who, during the 1960s, used representations of female bodies and food to create scandals. Three years earlier, on the other side of the former ‘Iron Curtain’, experimental filmmaker and performance artist Carolee Schneemann created a performance piece called Meat Joy in which she combined sexuality and food. Taking up Antonin Artaud’s concept of the ‘Theatre of Cruelty’, she aimed to agitate the audience by bombarding their senses, enveloping and immersing them, blurring the borders between life and theatre (Middleman, 2018: 46–47). Eight performers, wearing only underwear and bikinis, moved or crawled around the stage, interacting with each other: painting each other’s bodies, wrestling, lying on the ground cuddling, and playing with raw food, such as fish, meat and poultry. Jill Johnston, a dance critic, wrote in The Village Voice of 26 November 1964:

The point of the meat and fish and paint was to demonstrate the sensual and scatological pleasure of slimy contact with materials that the culture consumes at a safe distance with knife and fork and several yards away in a gallery or museum. […] Schneemann sought to challenge standards of appropriate behavior for women and decorum in art. (Johnston in Middleman, 2018: 47–48)

And, indeed, Meat Joy did provoke radical reactions amongst the audience. In New York, someone vomited, and in Paris a man was so enraged by the event that he tried to strangle Schneemann. These responses indicate that her art had the intended effect of challenging women’s position in society. Sedmikrásky appears to have had a similar effect on the Czechoslovakian government. In the end, irrespective of Chytilovà’s possible intentions, the way the film was received clearly shows that it was interpreted as a critique of patriarchal society (Lim, 2001: 41), giving her an international reputation as a feminist filmmaker.

1 In her article ‘Colour and the critique of advertising’ (2020), Sarah Street analyses how the aesthetics of glossy surfaces, superficiality, and performance in advertising are used to critique this practice in similar ways to Godard.

2 The deviant use of colour and the grotesque representation of the human body in the film seems to partly fit the 1980s and 1990s phenomenon of ‘Abject Art’. Similarities occur, for example, with the work of photographer Cindy Sherman, who also used coloured light to render disgusting objects even more so. ‘Abject Art’ was one of the practices that grew out of Julia Kristeva’s 1982 interpretation of the concept ‘abjection’. (For more on this see: Arya and Chare, 2016).

3 Death comes a few minutes later, when Bond finds the woman on the bed, suffocated, covered in gold paint, creating a sense of shock and maybe even awe at the surprising way the murder was carried out

4 This connection between sex and food in film probably found its climax in the scene in 9 ½ Weeks (USA 1986, Adrian Lyne) in which Kim Basinger keeps her eyes shut as she is fed all kinds of food in a variety of colours, spilling over her face and body.

5 First published in France as La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement by Les Éditions de Minuit in 1979.

6 This line of argument that was used to ban the film from the screens and bar Chytilovà from working is reminiscent of the obscenity ruling in the Roth v. United States case in 1957. In this instance, the Supreme Court defined ‘hard-core porn’ as those depictions of sex that it considered to be ‘utterly without redeeming social importance’ (Williams, 1989: 87).

7 ‘[...] diesem Film, der vor allem schön ist, der wie ein junges wildes Mädchen von einem Baum vor unsere Füße springt und uns auffordert, ihr zu folgen, damit sie uns das Sehen und Schmecken, das Riechen und Fühlen zeigen kann, bevor es zu spät ist.’

8 ‘Er bringt antiautoritäre und feministische Gesellschaftskritik auf verfremdende und urkomische Weise in diese verdorbene Welt der Herrschaft, in der wir für die Selbstverständlichkeit einer erfüllten Existenz für alle kämpfen sollten, die einen Drang danach haben, ihr Leben voll und ganz zu spüren und auszukosten’ (https://www.xn--untergrund-blttle-2qb.ch/kultur/film/tausendschoenchen-film-2003.html).