13. Anarchive and Arts-Based Research:

Upcycling Rediscovered Memories

and Materials

© 2024 Raisa Foster, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.13

Humans living in postindustrial societies have slowly realised that the ecological crisis is a crisis of our culture. Therefore, to address the ecocrisis, we need to understand our place as humans in a radically new way. We cannot continue to elevate ourselves above the rest of nature and exploit other lives in pursuing just our own interests. Archiving is one example of the human tendency to conquer and control culture and knowledge. Anarchiving has been thus suggested as a counteract that welcomes transformation and reciprocal knowledge-creation in multiple complex relations between different times and spaces and between people and the more-than-human world. In this chapter, I ask how arts-based research can be understood as a practice of anarchiving that challenges the assumptions of novelty and originality in art and in life. By applying contemporary art’s philosophy of (un)doing the existing unsustainable structures and values, it is possible to imagine more sustainable art-making processes and to adopt sustainable orientations towards life more generally. As example, in this chapter, I describe how I upcycled rediscovered materials in my art (drawings, videos, and sound artworks) instead of starting from mental (genius) ideas and raw (virgin) materials—an approach that allows for complex meanings to emerge in-between the materials and memories.

Floods in Australia, drought in Somalia, microplastic found in human blood—news stories worldwide are telling apocalyptic narratives of the ecocrisis. Humans living in postindustrial societies have slowly realised that the ecological crisis is a crisis of our culture (Plumwood 2005). Therefore, we must fundamentally rethink how we consume, build, and move around. It is evident that even if quick, sustainable solutions to the escalating environmental catastrophe are implemented, small changes are not enough. Innovations in recycling and green energy are more than welcome, but what is desperately needed is a transformation comparable to a spiritual awakening (Vadén 2016). We must critically reflect on and rearticulate our values and the concepts of human and reality. The illusion of the world in which things are hyper-separated and humans are in total control of reality and truth must be radically rethought.

Archiving is one example of the human tendency to conquer and control culture and knowledge (Derrida 1995; Trouillot 2015). Its selective practices ignore subjects that are, for example, racialised and indigenous (Ware 2017), disabled (Britton et al. 2006), and other-than-humans (Miller 2021). Archives are also based on the idea of time as linear and space as stable (Brothman 2001). In acknowledging the hegemonic power structures of archiving, some critical scholars and artists have introduced ‘counter-archiving as a method of interrogating what constitutes an archive and the selective practices that continuously erase particular subjects’ (Springgay et al. 2020, p. 897, emphasis in original). ‘Anarchiving’ (Massumi 2016; Springgay et al. 2020) has thus been suggested as a counteract that welcomes transformation and reciprocal knowledge-creation in multiple and complex relations between different times and spaces and between people and the more-than-human world.

In this chapter, I ask how arts-based research can be understood as a practice of anarchiving that challenges specifically the assumptions of novelty and originality in art and in life. After introducing the concept of upcycling used in design and art, I will briefly outline the idea of anarchiving as a research-creation method (Springgay et al. 2020). I will then discuss my artistic process that started from childhood memories collected in the Reconnect/Recollect project. The artistic practice generated drawings, videos, and sound artworks in which the collected memory stories were combined with my personal experiences and transformed into poetic and metaphorical representations. I created the works by repurposing video footage and life drawings that already existed in my personal archives.

Upcycling in Art

The green shift in production means more emphasis is put on reusing something considered waste (Hole and Hole 2019). Things destined to be destroyed are transformed into something else for environmental purposes in the recycling process. Recycling materials saves landfill space (Tam 2008), and it also takes part in resource conservation by reusing discarded instead of new materials (Reijnders 2000). Transforming existing things into new products also means that far less energy and water are used in production than the process that starts from raw materials (Del Ponte et al. 2017). However, the traditional idea of recycling can be described as ‘downcycling’ if materials are transformed into something with less value than the original thing (Geyer 2016). ‘Upcycling’, by contrast, adds more value to the materials. Upcycling is thus a specific concept in design that describes a process of transforming waste materials into new products of higher value (Bridgens et al. 2018).

In the arts field, too, using recycled materials is a growing—but not a new—trend. For example, Pablo Picasso’s collage work created from newsprints and other pieces of paper or Marcel Duchamp’s and Robert Rauschenberg’s repurposing of objects such as bicycle tires and street signs are some early examples of upcycling of materials for artistic purposes (Somerville 2017). Likewise, sustainable art composed from plastic bags, pieces of clothing, glass bottles, or other waste that would end up filling landfills or floating in rivers and oceans may delight with its creativity (Odoh et al. 2014). It must be noted, though, that upcycled art can also play a role in capitalist production as a form of ‘aesthetic economy’ (Böhme 2003) if the waste is transformed into an aesthetic form only to satisfy art buyers’ desires for beauty and playfulness. In such cases, the central aim for upcycling in art may simply be profit-making. However, contemporary art can be a powerful tool to criticise capitalist production or push audiences to reflect on postindustrial societies’ modernist belief in continuous progress and consumerism (Foster 2019; Martusewicz et al. 2015; Mears 2018). For example, the meaning of installations and performance art must often be understood beyond monetary value, in the relations they create (Foster and Martusewicz 2019; Mears 2018).

Upcycling can also be reflected in how artistic practice can challenge the assumption of novelty and originality in arts. How can new artworks be created from ideas and materials that the artist already has instead of starting from scratch? Originally a dance practitioner, I have been troubled by the short life-cycle of stage performances in the freelance field of performing arts. A lot of effort and resources are put into making an artwork that only gets a few showings. My perhaps unconscious response was to form a habit of repurposing in new works not only props and costumes but also ideas, images, and movement sequences from my older works. This practice of ‘recycling old materials’ has been a way of continuing my artistic process instead of thinking of my artworks as end products, which should not be touched after their completion (see also Foster 2019). For example, in 2012, I created a stage work entitled ‘Ketjureaktio’ (Foster 2012) or ‘Chain Reaction’ in English. Then, in 2016, I transformed the choreography into a dance film ‘Sounds of Grey’ (Foster 2016). I also repurposed some of the leftover footage from the film in three of my video works (see ‘Lupina’ 2018). In these works (see Figure 13.1), I did not only recycle ideas and movements from my previous works but also props such as cardboard boxes, business cards, and feathers. The continuous artistic process generated not only new artworks as static products but as an ongoing and messy entanglement of expressions, relations, sensations, and layers of interpretations and meanings in constant flux.

Fig. 13.1 Raisa Foster, artworks made from upcycled material and mental resources: [top] ‘Ketjureaktio’, a stage performance, 2012; [middle] ‘Sounds of Grey’, a dance film, 2016; [bottom] ‘Lupina’, a video work, 2016. Photographs by Mikko Korkiakangas (2012) and Raisa Foster and Mika Peltomaa (2016).

In short, the idea of upcycling in arts can be understood from a very concrete point of view of repurposing materials in a way that adds value to them. For example, installations and sculptures in visual arts and props and costumes in performing arts can be made from discarded materials, or the upcycling can happen by simply framing an everyday object such as a porcelain urinal as an artwork, like Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ (1917). However, upcycling can also be a more conceptual practice of exploring what is meant by originality, creativity, and novelty in arts in order to move beyond the modern assumptions that materials and ideas, objects and subjects, are static and disconnected from each other.

Anarchiving

The word ‘archive’ has its origin in the Latin archīa. Also, in Greek, archeîa means ‘public records’ and archeîon ‘town hall, public office’. In today’s use of English, the noun ‘archive’ refers to a collection of records or historical documents of or about an institution, family, person, or nation. It also names the place where such records are kept. The verb ‘archiving’ refers to the action of storing documents, data, or things in a repository. It could be said that archives are based on the idea of time as linear: the archive consists of past events and historical objects and documents. The idea of space in archiving is stable: the archived things are stored in a particular physical or digital site to be kept intact. The archive, both a collection of data and a place, is thus assumed to be objective and static (Brothman 2001), similarly to the conservative idea of an artwork as a consumable product to be preserved in bubble wrap in museums. Still, as it is impossible to store all knowledge and each culture in archives, archives always represent partial truths (Trouillot 2015). The selective practices in archiving enforce power and control (Derrida 1995; Springgay et al. 2020): whose stories are worth keeping? Who decides how the culture is stored and how the collected data is used?

Unlike the idea of the archive as linear, stable, and static, the anarchive is understood as responsible, reciprocal, and in constant flux (Springgay et al. 2020). The anarchive is not a repository of the past but a springboard for the now and the future. It is not a thing but a process (Springgay et al. 2020). Furthermore, anarchiving is not about storing and searching for the ‘truth’ but asking about what new thoughts, emotions, and sensations it opens (Deleuze and Guattari 2004), similarly to the recycling and upcycling in art that reopens the process for new meanings, feelings, and experiences.

Brian Massumi (2016) describes the anarchive as ‘a repertory of traces’ which carry the potential to initiate something new. The idea of a trace suggests the existence of some documentation, an object, a memory story, or something else, from which the traces originate. So, the anarchive continues the idea of the archive but allows it to turn in new directions. Massumi (2016) stresses that an anarchive is not contained in an object as a documentation of the past, instead, it is ‘a feed-forward mechanism’ that lures for further meaning creation. In this way, it is just like a piece of contemporary art that, at first, may seem odd and meaningless but, later, may evoke multiple emotions and interpretations (Foster 2019). The anarchive is activated between the various archival forms it may take and the verbal and material expressions and interactions it further generates. Thus, anarchiving is a practice of creating collaborative encounters (Massumi 2016).

Anarchiving can be seen as countering hegemonic structures and colonial knowledge (Springgay et al. 2020). It brings forward voices from the margins and notions of the unknown. More importantly, the meanings in an anarchive arise in multiple relationalities of past and future, of here and there, and of people and the more-than-human world. Anarchiving recognises the value in the transformation of things, in instability, and in unknownness.

Arts-Based Research with Memory Stories

I started to work in the Reconnect/Recollect project in October 2020. At that point, many memory stories were already archived on the project website. My first task was to read through all the memories. I looked specifically at the memories related to the moments when children participated in and with the more-than-human world. I read stories about lives in the countryside, about harvesting, and about humans interacting with other-than-human animals. I was captivated by the memory vignettes expressing children’s experiences of being curious and fascinated about all of the lives and deaths they encountered in the day to day.

The archived memories evoked my personal memories of childhood and from more recent moments in my life. I started to discuss the memories through academic writing but also by practicing art. The practices of artmaking and more traditional academic research informed each other in ways that could not be described as straightforward; it became impossible to draw a clear line between these activities. Presenting and discussing the memories, ideas, and artworks at conferences (see, e.g., ZIN et al. 2021) played a major part in developing my artistic practice and interpreting it. Drawing and working on video and sound editing, coupled with the collaborative reading of memories with a group of multidisciplinary researchers, helped me to further conceptualise, for example, the phenomenon of ecosocialisation (Keto and Foster 2021; Foster et al. 2022b), imagination and metaphor (Foster et al. 2022a), and the paradox of tragedy in art (Foster 2023). Also vice versa, various theories greatly influenced my artistic practice. See, for example, video artworks ‘The Body’ (Foster 2021a) and ‘Tiny Creatures’ (Foster 2021b) as well as the sound artworks ‘63 Windows’ (Foster 2021c) and ‘Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?’ (Foster 2021d).

The starting point of my multidisciplinary art practice is the human’s bodily relation to the world. We live in and engage with the world not just through our thinking minds but primarily as emotional and sensing bodies (Merleau-Ponty 2008). However, this is something that humans tend to forget (Keto and Foster 2021). The illusion of human separation from the rest of the living world causes ecological problems, which are, in fact, the problems of our culture (Plumwood 2005): modern humans have failed to adapt their culture to the planetary boundaries (Steffen et al. 2015). We live in the world as if we were ‘pure’ conscious beings without a body and without relation to our environment or other living beings (Varto 2008).

Arts-based research (Barone and Eisner 2011; Knowles and Cole 2008; Leavy 2015; 2019) shifts between intuitive and analytical ways of knowing (see also Kallio 2010). The sensory, emotional, and cognitive dimensions are inextricably intertwined in artistic, embodied ways of knowing. This kind of experiential knowledge is often multifaceted and thus difficult to discuss (Parviainen 1998). However, this should not be seen as a weakness in arts-based research because one of its central values is its ability to bring out momentary and partial knowledge and, at the same time, perhaps capture the essence of humanity and reality (Kallio 2010). The difficulty of verbalising an experience with clarity does not mean that the phenomenon did not exist or could not be studied. In contrast, the phenomenon must be studied—but through new methods such as art-based ones. Artistic inquiry can be used to address something that escapes verbal definitions. With arts-based research, it is also possible to reach a wider audience than traditional academic research because art touches the recipient emotionally and not just cognitively (Leavy 2015).

I presented my artistic research based on the Reconnect/Recollect memory archive in my solo exhibition entitled More than Human (Foster 2021) in June 2021 in Tampere, Finland. The exhibition consisted of charcoal, chalk, and ink drawings but also sound and video art. I explored memories that describe childhood experiences in different environments and interactions with other living beings. Through my artworks, I looked at how humans are in direct contact with the world precisely through their sensuous bodies. Through bodily perceptions, it is also possible to understand how the world is in us, as we carry sensations, emotions, and memories in our living bodies (Merleau-Ponty 2008; Parviainen 1998).

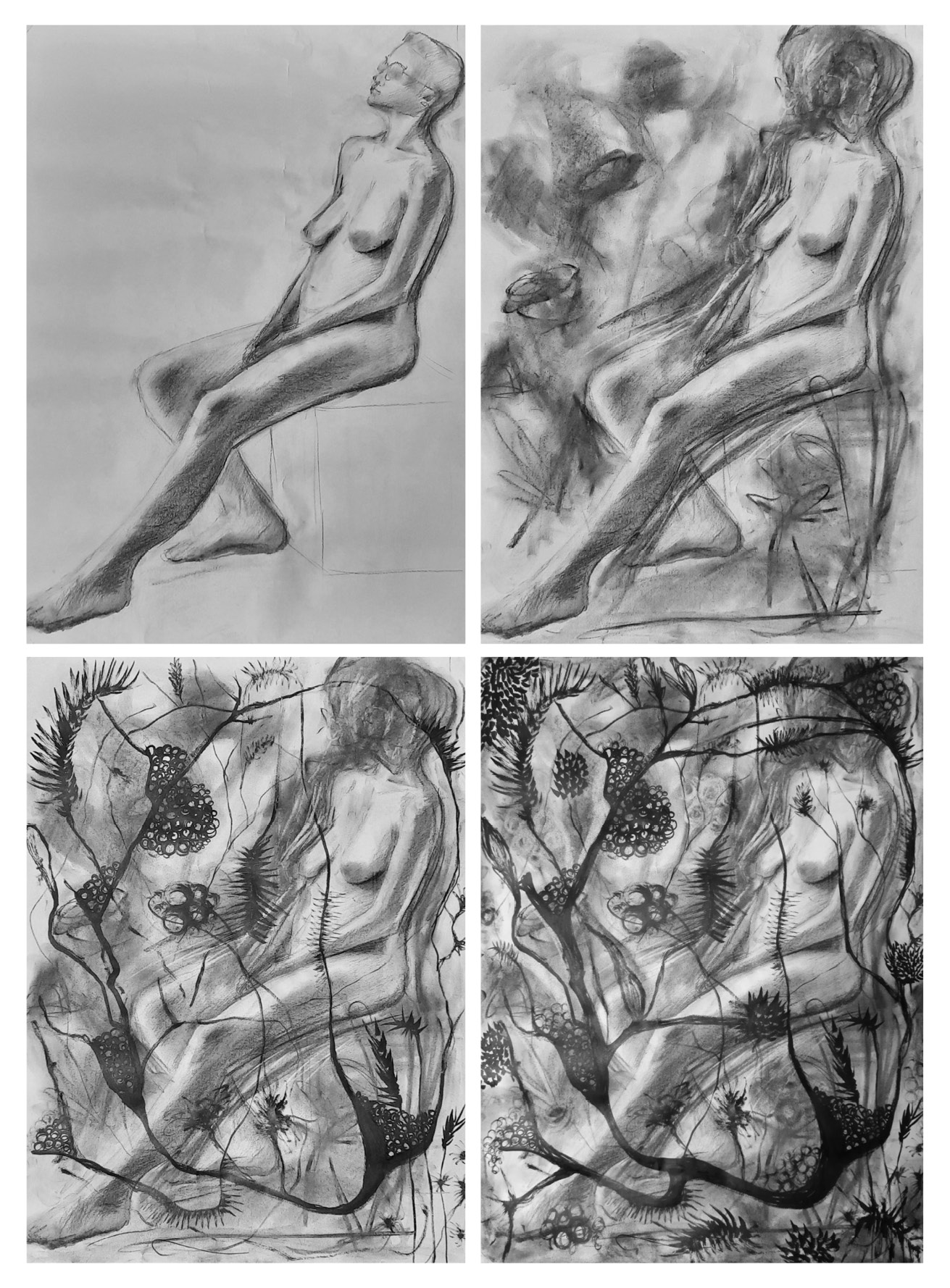

The collected memory stories were combined with my personal experiences and were transformed into poetic and metaphorical narratives in the video and sound artworks. The works were created from repurposing video footage that I already had in my personal archives. The drawings were also created by upcycling, continuing my previous drawings by editing, erasing, covering, and otherwise destabilising them. The sensuous body was, thus, not only the topic of my drawings but also the process of drawing itself was a strongly embodied experience.

Rediscovering Memories and Materials

The modern assumption of artmaking is that the artist first has an idea, then presents it in the form of art, as a painting, theatre or dance piece, musical composition, or some other medium (Foster 2019). From this perspective, the artist’s job is to produce novel creations from their original—and often described as ‘genius’—ideas (Montuori and Purser 1995). Similarly, in the context of the memory project, one may expect that the artist has illustrated the collected childhood memories as such. This understanding of art is seen in some audience responses, too. For example, the recipient of an artwork may try to figure out the artist’s intention or the memory that inspired it. So, one looking at art may expect to find a singular, coherent story, message, or meaning in that work (Landau et al. 2006).

Contemporary art practice often challenges modern assumptions, such as rationalism, individualism, instrumentalism, consumerism, mechanism, the idea of continuous progress, and centric thinking (Foster 2019). It does so not just with its content but also through its form and methods. For example, a collectively created multidisciplinary art project can problematise the overpowering effects of rationalism and individualism and help us grow towards a more holistic or community-oriented worldview. When art is approached as an immaterial process rather than a material product, consumerism is questioned. Similarly, instrumentalism is challenged when focus is placed on the intrinsic value of art and the relationalities of things. The meaning of contemporary art lies in its capacity to invite practitioners and audiences into the unknown and to initiate multiple interpretations. It thereby undermines the idea of mechanical production and the belief in continuous progress. Contemporary artworks can help people value diversity and mutuality in both people and the natural environment, which awakens criticality towards anthropocentrism, androcentrism, and ethnocentrism (see Foster 2019).

In short, the potentiality of contemporary art education lies in the alternative models of thinking and the practice of undoing to build sustainable life orientation. To be clear, in contrast to the idea of ‘sustainable development’, which focuses only on ‘greening’ the continuous growth (see OECD 2011), ‘sustainable life orientation’ refers to the pursuit of life as an integral and meaningful part of the more-than-human world (Foster et al. 2019). Contemporary art practice, which helps to recognise the intertwinement and intrinsic value of all life forms, can accelerate the debate to resolve planetary crises and strengthen hope for the future (Foster et al. 2022c).

In the memory project, one of my artistic practices was drawing, which built on my previous life-drawing studies. Life drawing, the drawing of a human model, has been a pillar of general art education since the Renaissance (Skaarup 2017). The roots of this tradition stem from ideals of European culture in which the man is a measure of everything and specifically his body as a significant mediator of beauty, goodness, and truth (Sawday 2013). However, as a practice, life drawing can challenge such ways of seeing. In life drawing, one must forget the rational idea of a human figure and settle down to genuinely perceive the model as it is and to recognise the lights and shadows, space, rhythm, continuums, and contrasts. So, the practice requires close observations. One must draw what is seen through the eyes rather than what is known by the mind about a human figure. In that sense, life drawing can be taken fundamentally as a practice of the ‘phenomenology of perception’ (Merleau-Ponty 2008). It is not about copying a pre-existing—concrete or imagined—object but instead ‘laying down of being’ in the act of drawing itself (ibid., p. xxii).

When creating the drawings for the More than Human exhibition, I did not start with a clear idea, an ‘imagined object’, or a ‘mental vision’ but with materials that I found in my personal archives. I started to add other layers on top of these drawings, allowing multiple relations to emerge in the image. Trusting the embodied process, I engaged with these drawings intuitively rather than intellectually (Foster 2019; Kallio 2010). Each addition, deletion, line, and rubbing-out sought to bring back to life drawings that were once discarded. Moment by moment and stroke by stroke, I witnessed the ‘miracle of related experiences’ that emerged in my drawing (see also Merleau-Ponty 2008, xxiii). I made careful observations and selections but also embraced coincidences and improvisations (see also Kallio 2010) with the aim of doing and undoing an image that would breathe again and invite observers, too, to live with the work. The resulting image was a surprise for me. My original drawing, one that had been just a practice study of a human figure, was ‘upcycled’ into an artwork via this artistic process (Figure 13.2.).

Fig. 13.2 Raisa Foster, untitled life-drawing study that was upcycled by adding layers and framing it as an artwork, 2021. Photograph by Raisa Foster, 2021.

All of the drawings I presented in the More than Human exhibition were created from pre-existing materials. The ideas, interpretations, and meanings of the artworks only came later. Therefore, it could be said that I did not produce the works but, instead, rediscovered them. After forgetting them, as one might do with memories, I found these drawings again and found something more in this creative process. Even though my drawings were not explicitly connected to the stories of the project or my own childhood memories, together with other works, they formed the overall experience of the exhibition, in which the memory stories’ themes of body and sensibility, life and death, and the intertwining of humanity and the rest of life were communicated through different artistic means, reinforcing further relations and meanings in between each other.

The video works I presented in the exhibition were created similarly by upcycling old materials. For example, the video work, ‘Tiny Creatures’ (Foster 2021b), was created from the footage of two videos that I found on my computer. First, I read the memory ‘Water Lilies’ (n.d.), which tells the story of a child spending a lazy summer day by a pond (Foster et al. 2022b). The child is observing an orchestra of bugs, bees, and flies. She is fascinated by this miniature world, so tiny in size but so rich in sound and visual details.

Fig. 13.3 Raisa Foster, still from a video artwork ‘Tiny Creatures’, 2021.

While I was reading this memory story, I remembered being on holiday in Malta a couple of years ago. I was amazed by ants running across the concrete paving in front of an abandoned hotel complex. I found the video footage of these ants in my personal digital archive. Rewatching this, I then remembered another video that I had filmed on top of the Oslo Opera House. The second film clip pictured tiny humans walking along a shore. I superimposed these two pieces of footage together with a narrative composed from the memory, and that is how the video art piece, ´Tiny Creatures’ was born (see Figure 13.3). Again, it could be said that I discovered the work rather than produced it. Upcycled art was created in this process of rediscovering the video materials and recollecting my personal memories similar to the memory story. The memory archive was also turned into an anarchive by making new connections through this artistic engagement with memories and materials.

I did similar upcycling with my sound installation. The sound work ‘Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?’ (Foster 2021d) tells a memory-story of a child visiting a chicken farm that was operated by her father in Hungary (Foster et al. 2022b). When I read the child’s memory of being afraid of stepping on the hundreds of tiny chicks on the barn floor, I remembered the hundreds of empty eggshells stored in my attic. I had used these eggs in a stage performance in 2006 and another in 2010, but I had not had any use for them for ten years afterwards. The child’s memory of the chicken farm asked for these eggs to be recycled in this sound work. The sound art installation involved the eggs being scattered around a plinth to give the audience a similar feeling of risk that they, too, might step on the fragile chicks (Figure 13.4). Again, the memory archive was transformed into an anarchive: the memory and the eggs together work as traces that carry the potential to evoke new relations and meanings in between the installation and a person experiencing it.

Fig. 13.4 Raisa Foster, ‘Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?’, sound art installation, 2021. Artist’s photograph.

Conclusion

For me, art is not ‘just art’ but a transformative action at its best. To address the ecocrisis, we need to understand our place as humans in a radically new way. We cannot continue to elevate ourselves above the rest of nature and exploit other lives in pursuing just our own interests. We need to understand that there are no humans without well-functioning ecosystems. However, adopting a sustainable life orientation does not have to mean scarcity and suffering. On the contrary, as we connect with others—human and more-than-human—we can find our lives enriched through and in these rediscovered, significant relationships.

I hope the examples of my arts-based research have shown that the idealisation of an artist’s—or a human—task to produce novel and original works (of art) from ‘pure’ ideas or materials can and should be challenged. Furthermore, with contemporary art’s philosophy of (un)doing the existing unsustainable structures and values, it is also possible to imagine more sustainable art-making processes. As example, in this chapter, I described how I have upcycled rediscovered materials in my art instead of starting from mental (genius) ideas and raw (virgin) materials, which allowed for complex meanings to emerge in-between the materials and memories.

We can look at the conservative idea of artistic production as an archive that aims to capture and preserve the artist’s original and novel ideas. In relation to the childhood memory project, one may assume that the artist has aimed to illustrate the archived memory stories as such. However, in this project I have approached artmaking as a creation of new connections, an ‘anarchiving’ that aims to generate continuous relations between diverse memories and materials. I hope that this generative process initiated by the artistic engagement does not stop in my ‘finished’ artworks. As I and others revisit my drawings, videos, and sound works, they will function as a repertory of traces that keep stimulating new, unexpected responses and contribute to an ongoing anarchiving of childhood memories.

References

Barone, T., and Eisner, E. W. (2011). Arts Based Research. Sage, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230627

Bridgens, B., Powell, M., Farmer, G., Walsh, C., Reed, E., Royapoor, M., Gosling, P., Hall, J. and Heidrich, O. (2018). ‘Creative Upcycling: Reconnecting People, Materials and Place through Making’. Journal of Cleaner Production, 189, 145–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.317

Britton, D. F., Floyd, B., and Murphy, P. A. (2006). ‘Overcoming Another Obstacle: Archiving a Community’s Disabled History’. Radical History Review, 2006 (94), 212–27, https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2006-94-212

Brothman, B. (2001, January 1). ‘The Past that Archives Keep: Memory, History, and the Preservation of Archival Records’. Archivaria, 51, https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12794

Böhme, G. (2003). ‘Contribution to the Critique of the Aesthetic Economy’. Thesis Eleven, 73(1), 71–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513603073001005

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. (2004). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. by B. Massumi. Continuum. (Original work published 1988)

Del Ponte, K., Madras Natarajan, B., Pakes Ahlman, A., Baker, A., Elliott, E., and Edil, T. B. (2017). ‘Life-Cycle Benefits of Recycled Material in Highway Construction’. Transportation Research Record, 2628(1), 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3141/2628-01

Derrida, J. (1995). ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’. Diacritics, 25(2), 9–63, https://doi.org/10.2307/465144

Foster, Raisa (2012). ‘Ketjureaktio’ [Video]. YouTube, uploaded by Raisa Foster, 18 April 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SImOapepywY

—— (2016). ‘Sounds of Grey’ [Video]. YouTube, uploaded by Raisa Foster, 3 March 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Q4HmCghWjY

—— (2018). ‘Lupina’ [Video]. YouTube, uploaded by Raisa Foster, 16 May 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XTZAUk5EGU

—— (2019). ‘Visual Art Campaigns’, in The Oxford Handbook of Methods for Public Scholarship, ed. by P. Leavy. (pp. 383–418). Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274481.013.12

—— (2021a). ‘Raisa Foster: The Body (a viewing copy)’ [Video]. YouTube, uploaded by Raisa Foster, 12 April 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RTC-jm9iCQs

—— (2021b). ‘Raisa Foster: Tiny creatures (a viewing copy)’ [Video]. YouTube, uploaded by Raisa Foster, 1 September 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_2QXbHGT1eU

—— (2021c). ‘63 Windows’ [Mp3 track], https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HGO2xTT920BgNIQulUdusV1PROp19-5P/view

—— (2021d). ‘Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg?’ [Mp3 track], https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vyES4UZWuOd-auUyNjyFoHN6Fi-hM8jW/view

—— ‘Raisa Foster: More than Human’. (2021, July). [Blogpost], Memories of Everyday Childhoods: De-colonial and De-Cold War Dialogues in Childhood and Schooling, https://coldwarchildhoods.org/blog/raisa-foster-more-than-human/

—— (2022). Raisa Foster. Artist portfolio, https://www.raisafoster.com/

—— (2023). ‘The Living Dying Body: Arriving at the Awareness of All Life’s Interdependencies through a Video Artwork’. Research in Arts and Education, 2023(1), 31–42, https://doi.org/10.54916/rae.126189

Foster, R. and Martusewicz, R. (2019). ‘Introduction: Contemporary art as Critical, Revitalizing, and Imaginative Practice toward Sustainable Communities’, in Art, EcoJustice, and Education. Intersecting Theories and Practices, ed. by R. Foster, J. Mäkelä and R. Martusewicz. (pp. 1–9). Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315188447

Foster, R., Salonen, A. O. and Keto, S. (2019). ‘Kestävyystietoinen elämänorientaatio pedagogisena päämääränä’ [Sustainable Life Orientation as a Pedagogical Aim], in Opetussuunnitelmatutkimus—ajan merkkejä ja siirtymiä, ed. by T. Autio, L. Hakala, and T. Kujala. (pp. 121–43). Tampere University Press, https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/118706/kestavyystietoinen_elamanorientaatio_pedagogisena_paamaarana.pdf

Foster, R., Törmä, T., Hokkanen, L., and ZIN, M. (2022a). ‘63 Windows: Generating Relationality Through Poetic and Metaphorical Engagement’. Research in Arts and Education, 2022(2), 56–67, https://doi.org/10.54916/rae.122974

Foster, R., ZIN, M., Keto, S. and Pulkki, J. (2022b). ‘Recognising Ecosocialization in Childhood Memories’. Educational Studies, 58(4), 560–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2022.2051031

Foster, R., Salonen, A. O. and Sutela, K. (2022c). ‘Taidekasvatuksen ekososiaalinen kehys: Kohti kestävyystietoista elämänorientaatiota’ [The Ecosocial Framework for Art Education: Towards Sustainable Life Orientation]. Kasvatus, 53(2), 118–29, https://doi.org/10.33348/kvt.115918

Geyer, R., Kuczenski, B., Zink, T., and Henderson, A. (2016). ‘Common Misconceptions about Recycling’. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 20(5), 1010–017, https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12355

Hole, G., and Hole, A. S. (2019). ‘Recycling as the Way to Greener Production: A Mini Review’. Journal of Cleaner Production, 212, 910–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.080

Kallio, M. (2010). ‘Taideperustainen tutkimusparadigma taidekasvatuksen sosiokullttuurisia ulottuvuuksia rakentamassa’ [Art-based Research Paradigm Building the Socio-Cultural Dimensions of Art Education]. Research in Arts and Education, 2010(4), 15–25, https://doi.org/10.54916/rae.118716

Keto, S., and Foster, R. (2021). ‘Ecosocialization—An Ecological Turn in the Process of Socialization’. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 30(1–2), 34–52, https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2020.1854826

Knowles, J. G., and Cole, A. L. (eds). (2008). Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. Sage publications

Landau, M. J., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., and Martens, A. (2006). ‘Windows into Nothingness: Terror Management, Meaninglessness, and Negative Reactions to Modern Art’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(6), 879–92, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.879

Leavy, P. (2015). Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice (2nd edn.). Guilford

Martusewicz, R., Edmundson, J. and Lupinacci, J. (2015). EcoJustice Education. Toward Diverse, Democratic, and Sustainable Communities (2nd edn.). Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315779492

Massumi, B. (2016). ‘Working Principles’, in The Go-To How To Book of Anarchiving, ed. by A. Murphie. (pp. 6–8). The SenseLab, http://senselab.ca/wp2/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Go-To-How-To-Book-of-Anarchiving-Portrait-Digital-Distribution.pdf

Mears, E. (2018). ‘Recycling as Creativity: An Environmental Approach to Twentieth-Century American Art’. American Studies Journal, 64(5), https://doi.org/10.18422/64-05

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2008). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge Classics

Miller, S. E., Jernigan, C. M., Legan, A. W., Miller, C. H., Tumulty, J. P., Walton, A., and Sheehan, M. J. (2021). ‘Animal Behaviour Missing from Data Archives’. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 36(11), 960–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.07.008

Montuori, A., and Purser, R. E. (1995). ‘Deconstructing the Lone Genius Myth: Toward a Contextual View of Creativity’. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 35(3), 69–112, https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678950353005

Odoh, G. C., Odoh, N. S., and Anikpe, E. A. (2014). ‘Waste and Found Objects as Potent Creative Resources a Review of the Art-Is-Everywhere Project’. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(6), 1–14

Parviainen, J. (1998). Bodies Moving and Moved: A Phenomenological Analysis of the Dancing Subject and the Cognitive and Ethical Values of Dance Art. Tampere University Press

Plumwood, V. (2005). Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. Routledge

Reijnders, L. (2000). ‘A Normative Strategy for Sustainable Resource Choice and Recycling’. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 28(1–2), 121–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-3449(99)00037-3

Sawday, J. (2013). The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture. Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315887753

Skaarup, B. O. (2017). ‘Applied Science in the Renaissance Art Academy’, in Art, Technology and Nature: Renaissance to Postmodernity, ed. by C.S. Paldam and J. Wamberg. (pp. 105–16). Routledge

Somerville, K. (2017). ‘Trash to Treasure: The Art of Found Materials. The Missouri Review, 40(3), 49–67, https://doi.org/10.1353/mis.2017.0040

Springgay, S., Truman, A., and MacLean, S. (2020). ‘Socially Engaged Art, Experimental Pedagogies, and Anarchiving as Research-Creation’. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(7), 897–907, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419884964

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., De Vries, W., De Wit, C. A., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, J. M., Persson, L. M., Ramanathan, V., and Sörlin, S. (2015). ‘Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet’. Science, 347(6223), https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408215600602a

Tam, V. W. (2008). ‘Economic Comparison of Concrete Recycling: A Case Study Approach’. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 52(5), 821–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2007.12.001

Trouillot, M. R. (2015). Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press

Vadén, T. (2016). ‘Modernin yksilön harhat ja ympäristötaidekasvatus’ [The Biases of the Modern Individual and Environmental Art Education], in Taidekasvatus ympäristöhuolen aikakaudella—avauksia, suuntia, mahdollisuuksia, ed. by A. Suominen. (pp. 134–42). Aalto ARTS Books

Varto, J. (2008). The Art and Craft of Beauty. Helsinki: University of Art and Design

Ware, S. M. (2017). ‘All Power to All People? Black LGBTTI2QQ Activism, Remembrance, and Archiving in Toronto’. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 4(2), 170–80, https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3814961

ZIN, M., Albarran, E. J., and Foster, R. (2021). Tentacular Anarchive: Memories of Childhood through Scholarly, Pedagogical, and Artistic Engagements [Online transmission of hub opening session]. ‘Spinning the Sticky Threads of Childhood Memories: From Cold War to Anthropocene’, https://events.tuni.fi/recollectreconnect2021/