15. Connecting Across Divides:

A Case Study in Public History of the (E-)Motion Comic ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West-Berlin’

© 2024 Sarah Fichtner and Anja Werner, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.15

In this chapter, we describe the process of—and reflect on our experiences with—creating the collaborative, international motion comic ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West Berlin’, which is based on memories that we shared in a Reconnect/Recollect project workshop. During this workshop, Sarah Fichtner shared her West Berliner childhood memory of accidentally riding an underground train through ‘ghost stations’ of East Berlin. In turn, Anja Werner recalled a scene from her East German childhood of when she actually heard such ‘ghost trains’ rumbling underneath an apartment in East Berlin. From the experience with our motion comic, we gather that motion comics, because they are pieces of art, can add additional layers to history work. They do so by working with and addressing emotions, thus becoming (e-)motion comics as they connect people through memories across divides, time, and space.

In collective-biography work, memories may connect persons, themes, and material things or objects. Objects referenced in memories connect people through their materialities, such as a bed that one person sleeps in and another one makes, or a train that one travels on and the other hears going by. It is almost as if, through these objects, one person becomes a participant in another’s memory and, thus, earlier life. The memories complement one another, thus allowing remembering participants to come to terms with them by encountering another person’s recollections of the same objects or events.

This effect is not limited to the two people sharing their memories but also transfers to those who are listening to the memories or watching the outcome in the form of a motion comic. Authors and audiences may enter into each other’s experiences through tangible means, thanks to an ‘absent presence’ (Mazzei 2003, p. 27). They thus create connections even across divides, time, and space, deepening our understanding of situated perspectives through shared memories.

In working with shared memories, visual media—in contrast to texts—offer different representational possibilities and modes of impact: They directly draw us into the story, make interconnections tangible and give ‘data’—in our case, memory—a face, a voice, and a feeling. Visual media thereby present an easily accessible form of knowledge transfer that is far from being unidirectional.

In this chapter, we describe the process of—and reflect on our experiences with—creating a collaborative, international motion comic ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West Berlin’ (Fichtner and Werner et al. 2020). In four sub-sections, which are devoted to the processes of connecting, transforming, collecting, and transferring, as well as a concluding section of reflecting, we address the following questions: How is a connection created through a remembered material thing, here, the train? How does your own story become the story of others when it is translated into pictures and different languages? What happens as it takes on a life of its own? What kind of reactions does this trigger in recipients from near and far and across generations? Last but not least, what potential does this experience offer us for educational memory work—a form of Public History—across and about divides, allowing viewers to grasp the absent presence of others in all our lives?

Connecting Through Remembered Things in Shared Memories: How it All Started

The motion comic ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West Berlin’ is based on childhood memories that we shared in September 2019 in Berlin during a workshop organised by the Reconnect/Recollect project.1 Sarah Fichtner shared her West Berliner childhood memory of accidentally riding the underground train through ‘ghost stations’ of East Berlin when she was trying out a different and unknown way home from school. Here is a snippet of her memory story:

At Kurt Schumacher Platz in the West, the girl enters the U6 with her friends. For the first few stations she enjoys the ride. She feels independent and grown up. But her joyful and proud laughter stops abruptly when the train does not stop anymore. It passes through numerous, dimly lit, dark and empty ‘ghost stations’ that look like construction sights. Passing through those stations the train slows down. It does not stop. In the tunnel it regains speed. The girl panics. She realises that they are in the East: Even more disturbing: They are underneath the East. One of her friends starts to cry, wondering if they will ever get back to their parents. Is the train really taking them to their home destinations? Will they have to stay in the East? There are other passengers, but this does not prevent the children from feeling lost and alone.

When she had finished her story, a woman whom she had not known prior to this workshop, Anja Werner, recalled a scene from her East German childhood. Here is a snippet from Anja’s memory story—with her family, she is visiting friends in East Berlin and finds herself alone in a room:

There’s another one of those white Mohair rugs on the floor in front of the desk. She yawns. Why not lie down now?

As she’s lying on the floor, she can suddenly hear a sort of rumble coming from below. Just a short rumble—and gone. Silence. She holds her breath, waits… there it is again. She doesn’t know what that rumble is. Is she scared? No, just wondering. There it is again. And another. Always a brief interval of silence in between. The girl darts to her feet and runs to the living room. What’s this rumbling noise? It’s a short rumble, then it stops, and after a while there’s another one. What is it?

During the workshop, we juxtaposed our two memories, so that the audience learned simultaneously what the two girls inside and above the train felt and thought.

It was fascinating to experience how our two memories joined together, how we became part of each other’s memory by telling them jointly from two situated perspectives, from two sides of the Berlin Wall, and focusing on the same ‘thing’: the underground train. This train in its Western materiality can be understood to symbolise mobility as well as adventure but, with it, also the fear of border crossing. The absent presence of the train(s) in the East simultaneously stands for structural immobility that is being confronted with the powerful imagination of children and, thus, is resolved in a soothing way. Anja remembers:

I was very much surprised and delighted to hear Sarah’s story. So, I got up to talk about my mirroring memory of when I actually heard such ‘ghost trains’ rumbling underneath an apartment in East Berlin. Having both stories side by side felt like finally seeing the complete picture, and that to me personally felt soothing in some ways. It was like truly re-uniting the country by uniting our memories and making sense of them as a whole.

Intuitively, we both knew that this had to be captured in the form of a joint story. It was equally clear that this story needed a livelier and more emotional medium than the plain text. So, the idea was born to make a motion comic—or an (e-)motion comic as we like to call it—as this medium helps us both to transport and to deal with different kinds of emotions, such as fear and joy paired with excitement and curiosity, while also evoking such feelings in the viewer. We will come back to this later.

Transforming Memories: An International, Collaborative, and Creative Adventure

Motion comics are digital, moving-picture stories with text and sound that can easily be shared on the internet (Smith 2015). They allow us to tell a story-in-motion through images but are less complicated and less expensive to make than a cartoon or animated film, as fewer images are needed to make them work. Motion comics, consequently, are an effective and practical way to turn a written story into an animated video.

To transform our childhood memories into a motion comic, we called upon the illustration duo Azam Aghalouie and Hassan Tavakoli, originally from Iran. Sarah knew them from an earlier project, the Encounters Media Workshop (Medienwerkstatt Encounters). Azam and Hassan arrived in Berlin in 2017 and have remained fascinated with the extraordinary history of the city ever since. They listened to our story and were captivated.

We had initially written our two stories as two individual texts using the third- person perspective, following the advice of Susanne Gannon, who introduced us to the method of collective biography during the Reconnect/Recollect workshop (see Davies and Gannon 2006). We observed the reactions of our fellow participants and carefully considered their requests that we provide more or different details of almost-forgotten aspects. The basic idea of the memory sharing during that workshop was to explore experiences of childhood in the context of the Cold War. How did children live through everyday life in a divided world? Which moments did they memorise as ‘special’? In short, how did children make sense of growing up in the Cold War? How has this affected the adults into which the children grew?

The outcome was surprising. The memory sharing created a type of community across time and space that included not just those who told memories on their own or as a group, but also those who listened and watched. As the Reconnect/Recollect project and workshop organisers Silova, Piattoeva, and Millei observed already in 2018, ‘we felt a very personal connection during storytelling—almost as if we were related’, and like them, we too ‘were curious to explore these connections further’ (Silova et al. 2018, p. v).

Our initial thought was to see what happened if we joined an East- and a West-German perspective of a memory involving an object like the train. In the process, our shared memory took on a life of its own, creating something new as we went along. It also gained from the addition of perspectives from another cultural context thanks to the involvement of our Iranian friends. This transnational approach to German public history became an important aspect of our work as we embarked on a follow-up project.

In the following, let us explore our experiences in more detail, starting with a step-by-step look at the creative process behind ‘Ghost Train’. As a first step, we had to shorten both texts and merge them into one script with different chapters, applying a consistent narrative style. For instance, we chose to introduce both little girls with a similar phrase about the year in which they were born. In Anja’s case:

The girl was born in February 1976 in a strange little country whose leaders once upon a time had decided to build a big wall around it so that no bad people could get in, or so they claimed. But the little girl already knew only too well: No one could get out, either. Her life was one of longing to see what lay beyond that wall. Was there anything at all?

And in Sarah’s case:

She was born in April 1979 on what she perceived as an artificial island called West Berlin. She grew up in an apartment facing the train rails that connected ‘her’ island with the ‘rest’ of West Germany. Being surrounded by ‘the East’ and having people refer to places in the South as ‘West Germany’ definitely messed up her geographic sense of orientation.

We also had to smooth over or omit some details, such as references to the day of the week and time, in order to create a coherent narrative that was not openly self-contradictory.

Our motion comic raises questions about realism in artwork just as it touches on discourses about representations of the past that are central to historiography. This became obvious in the creative process. When we asked artists Azam and Hassan if they could transform this shared story into a motion comic, they read the text carefully and asked us to provide visual material, such as photographs of ourselves as children at the age we are in the story. This was necessary because our memories are based on actual events that can be located in time and space. Then again, as we will show below, the motion comic took on a life on its own—one that is, ultimately, fictional. We helped it on its way, perhaps, as we also took some liberties with the ‘facts’.

To grasp a sense and a feeling of the 1980s in the divided Berlin, the artists asked us for visual references to specific elements that we mentioned in our story, such as a school backpack, a toy police car, the furniture in the East Berlin apartment, the mohair rug, the radio. We provided them with photographs, taken at around the time of our story, of the divided Berlin, the bus, and the underground as they looked back then. We found some relevant images among our personal photograph collections, including those shared with Azam and Hassan in preparation of the motion comic (see Figures 15.1, 15.2, and 15.3).

Fig. 15.1 Anja at age six, around the time the ‘Ghost Trains’ incident happened. Photograph by Klaus Becker, Naumburg (Saale), 1982.

Fig. 15.2 Sarah at around age eight or nine. Photograph by Barbara Fichtner, Schwege, 1987.

Fig. 15.3 Sarah’s school backpack. Photograph by Barbara Fichtner, Berlin, 1985.

We also researched representative images on the internet that reflected the shape and look of things in our memories or simply represented the time and place in question. Already at that point we found a few ‘mistakes’. That is to say, we found examples of how our personal memories differed from the reality that others had captured in photographs. For instance, Anja remembered the Berlin Wall passing right through the Brandenburg Gate because that is how she perceived it at the age of six during a walk on the day of her memory. The research for the motion comic revealed that—seen from the East Berlin side—the Wall actually ran ‘behind’ the Brandenburg Gate. Eventually, we dropped the Brandenburg Gate from the visuals because it would have complicated the narrative structure. We did keep other critical points, though, such as the question of what the Berlin metro trains looked like in the 1980s. How much liberty could we take in depicting them? Moreover, Sarah and Anja disagreed over the title of the motion comic. While Sarah rode on only one train, Anja heard several. Should it be ‘Ghost Train’ or ‘Ghost Trains’? We wondered if it was possible to alternate, since the motion comic could be found on the internet no matter which version is searched? Was there a way to reflect both of our perceptions of the number of trains?

Dealing with such discrepancies raised the question of how authentic the visuals needed to be. They needed to provide a sense of the different time and space, but would they have to be authentic replicas, historically ‘correct’? Is it even possible to create authenticity in retrospect? After all, memories can be faulty or change over time, an idea that we felt should somehow be incorporated into the motion comic by including ‘visual inaccuracies’. In the end, our goal was not so much to reconstruct past events as a form of oral history but to focus on how children made sense of such events and what they took from it into adulthood, which also included changing images and shifting perspectives.

Based on the visuals we provided, Azam and Hassan created their first drawings with pencil as thumbnails and transformed our story into forty-nine images that they showed to us to get feedback (see Figure 15.4). We realised at this point that some pictures needed more or different details, that our story was inaccurate in some aspects and needed to be adjusted, or that Azam and Hassan had a really interesting perspective on some scenes that we had not seen before. The motion comic thus became a collaborative adventure. This was an important step in bringing the story to life, in turning two individual memories into a collaboratively created image of a specific time period in the past.

Fig. 15.4 Thumbnails: forty-nine images for the ‘Ghost Train’ story. Illustrations ©Azam Aghalouie und Hassan Tavakoli. Photograph by Sarah Fichtner, 2020.

At this point in our creative process, the Covid-19 pandemic started, and we did almost all our work together online. While we had not planned on collaborating through the internet, being suddenly forced to do so highlighted the potential of this particular medium for our project: our memories might not only cross divides but be available to audiences online. We would return to this idea when, after the release of the ‘Ghost Train’ motion comic, we started thinking about a follow-up project. But back to the creative process.

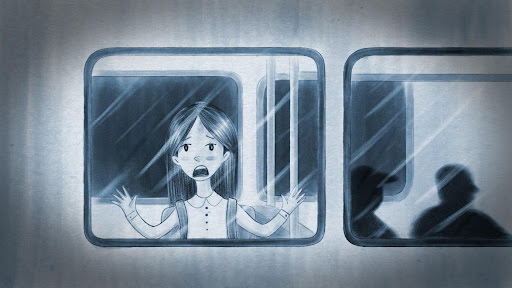

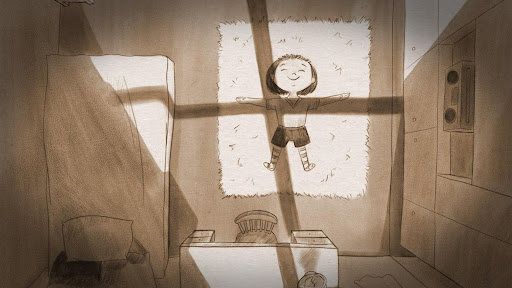

We decided to have two different colour schemes for the different narrators, and Azam and Hassan experimented with different shades to get the right mood. They then prepared the first actual sketches (Figure 15.5 and Figure 15.6).

Fig. 15.5 Sample illustration from Sarah’s part of the story. © Azam Aghalouie und Hassan Tavakoli, 2020.

Fig. 15.6 Sample illustration from Anja’s part of the story. © Azam Aghalouie und Hassan Tavakoli, 2020.

On the basis of these drawings, Azam and Hassan prepared a first video. Meanwhile, we recorded our stories in German and English. The original plan had been to meet and record it together in one session. But, because of the pandemic, we had to record the narration each on our own. It took some experimenting with our personal equipment until we had recordings that matched in quality and tone. As a finishing touch, we added some music.

The motion comic ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West Berlin’ was released on 9 November 2020, the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. It stands for encounters on multiple levels: memory meets memory, East meets West, two German stories meet the imaginative force of Iranian artists, illustration turns into motion picture. The ten-minute motion comic is available on YouTube in English and in German.2

Collecting Reactions: Shared Memories–Shared Analysis

After its online premiere in 2020 and after each public screening, we asked the audience to share with us anything that the motion comic might have triggered.3 It was like ‘spinning the sticky threads of childhood memories’ even further (‘Spinning the Sticky Threads of Childhood Memories’ 2021). We had reactions from people from diverse generations and backgrounds that reached us via comments and personal messages on social media, through email, in direct oral feedback after screenings, and on conference message boards. Viewers’ responses ranged from overall appreciation and observations of how the motion comic ‘touched’ them to the sharing of additional childhood memories related to ghost trains in Berlin and to the fall of the Berlin Wall. These memories connected with ours mainly on an emotional level, which is why we came to think of our motion comic as an (e-)motion comic. For example, one such contributor wrote,

This is the heart-warming story of two children and their family and friends in East- and in West-Berlin before the Wall came down. It‘s timely, the Wall came down 31 years ago, today! Although I didn‘t live in Berlin during that time, this post-War period affected me greatly and now this cine-cartoon and its underlying story touches me deeply. Hope that all will enjoy watching it and think how we can learn from the past. …

Viewers were reminded of their own childhood experiences of the Cold War; they said they were transported back in time. One person described it as follows:

I remember the time I was an 8-year-old girl in San Diego consciously watching the news for the first time. I remember the excitement of watching people tearing down a wall, celebrating, crying, hugging each other. All that visible emotion and there was a strong sense of hope that came out of a place called Berlin. Little did I know, I have grown to call that place home for over a decade now. Another memory of the divide was when I was hospitalized a few years ago. One older woman in the bed next to me was from the former West and another older woman on the left of my bed was from the former East. That one week stay was memorable for the stories they told me; how their lives and relationships took very different turns, and the conversations between family members with me in the middle.

Another person wrote:

I just watched your little piece of art and was immediately put back into my childhood. I can share every word of what you said about travelling through ghost stations. I did so many times as line 6 was my line into ‘the world’ (I lived near Tempelhof Airport then). So, thank you for this reminder of times long past (I just turned 60).

As mentioned before, the processing of memory also raised questions of authenticity. Right after the screening of the video at a conference, one person from the audience stood up and said:

This triggered a lot of memories. I grew up in West Germany but spent a lot of time in East Germany. And—I know this is a very geeky detail, but as a child I was very fascinated by trains. So not only did I always want to ride the U6 and U8 when I was in West Berlin visiting my uncle, I also enjoyed listening to the rumble of the U6 and U8 when I was in East Berlin. And one even more geeky bit of information: The train in the film is a post-revolutionary version. At that time they had these handles that you could hardly move, they didn’t have buttons, but that’s maybe too much information… (laughing)

In-depth analyses of the symbolic meaning of underground trains were also among the feedback we received:

I think for children, any means of transport is a symbol of adventure. So taking anything, a car, a train, an airplane, is a promise of something new, of something adventurous. And I think that especially subways and airplanes amplify this much more, since they move either underneath the ground or above the ground. And feeling or knowing about a subway which is not existable for you or which brings you into a totally different world, it just emphasizes this difference and the possibility of entering a different world. So I think it’s some kind of symbol or metaphor for those interconnected but strictly divided Berlins.

Another person shared the following insights with us:

It triggers the awareness that we are and were indeed connected through everyday experiences and major political processes despite our differences. It also promotes perspective-taking: an event (underground ride) is experienced in different ways by two children living in very different contexts. For both, however, the experience is disturbing in a human way. I therefore think that the project has also a high didactic value, e.g. for history or politics lessons. Thank you for sharing this wonderful work!

Yet another person revealed that she had been following the ‘Ghost Train’ story since its ‘inception,’ which led her to a remarkable analysis on the topic of movement and immobility that she published on a conference message board:

I was there when Anja and Sarah told their memories at the memory workshop back in 2019 and I was from the beginning drawn to them. I was mesmerized by the multiple layers of connectedness between the two stories. It never ceases to amaze me how hearing these entangled stories again and again brings up different feelings every time! As I saw the motion comic now, it became clear to me that there is also a story of movement/mobility vs. impossibility of movement/immobility. The ‘ghosts’ encountered by each girl are the ghosts of the ‘other side’ which can be both frightening and alluring at the same time. The ghost station is a symbol of immobility. It is static, caught in a state of permanence. For the observer, it is primarily a visual experience, a glimpse of the other side magnified by the presence of others sharing the same visions (i.e. the other girls on the train). What was originally an act of freedom (i.e. taking the unknown route home) became a state of feeling ‘trapped’ and a fear of being ‘stuck’ in the East. The ghost train, on the other hand, is a symbol of constant movement. In a rhythmic cadence, it embodies the cyclical movement between worlds, and reveals the mirage of mobility. It is primarily a sensory experience, a gut feeling, a sound leading to an imagination, amplified by the authoritative voice of the parents. What was originally a feeling of fear (i.e. hearing the rumble below and not knowing what it is) became an act of freedom, curiosity, and awe. I am drawn to reflect on what these movements mean in the different contexts, on what it means that movements may cut across times and spaces and go beyond physical and non-physical spaces, on how we may move while standing still and how we may not move while being fully mobile.

We were both touched and surprised by the thoughtful feedback of viewers that brought many new details to our attention and has the potential to inspire future investigations—for example, into trains as symbols of movement (or its absence) in this specific past. Most of all, we realised how emotional it can be to deal with the past when moving pictures are involved. Moreover, such emotions are not restricted to those who create the motion comic on the basis of personal memories; they also extend to those who watch it and relate to it through their own memories.

We did not get any feedback regarding a possibly disturbing or difficult emotion. We assume that the soothing message of our motion comic, which was to a significant degree inspired by the fact that we chose the perspective of innocent children, created a specific mood that touched viewers and evoked similar emotions in them. Memory work as an artistic process can, thus, produce almost therapeutic effects: it is not simply a means to deal with personal questions but a way of bringing about the realisation that we all might connect through our memories. A complex picture emerges of a creative process, historical research, and the uses and effects of public media that needs to be studied much more thoroughly in the future.

Transferring the Experience: Motion Comics as a Tool for Memory Work with Young People

When our motion comic was released and our memories started travelling around the world, provoking other people to share their reactions with us, Anja had the idea to use our experience as a tool for educational—and transcultural—memory work with young people. The basic underlying idea was to multiply and extend what we had learned in the process of creating and releasing our own motion comic. We wanted to engage young people as both producers and viewers of motion comics. Moreover, we wanted to include youths from families with migration experiences to open up paths to connect the various types of experience and thereby broaden our understanding of the history of the German division.

Our plan was to bring together the histories of the German division and of multicultural Germany by talking about border crossings within as well as to and from Germany during the Cold War and beyond. Together with the Marienborn Memorial to Divided Germany, which is a well-known former inner-German border crossing between Helmstedt in the West and Magdeburg in the East, we designed a project called ‘MoCom: Motion Comics as Memory Work: A Project by and for Young People in West and East Germany with and without Migration Experience’ (MoCom n.d.). It was financed by the federal program ‘Youth Remembers/ Jugend erinnert’, which is managed by the Federal Foundation for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Eastern Germany (a government-sponsored agency that focuses on critical public history about the German division). It was co-financed by the Foundation for Memorials of Saxony Anhalt, the federal state where the Marienborn Memorial is located.4

The project aimed to get young people interested in recent German history by drawing on and establishing links between different experiences with borders, dictatorships, and migration movements. Between the summer of 2021 and the end of 2023, we convened four groups of about three to six young people mainly between fifteen and twenty-five years of age from across Germany. With each group, we explored one of four different themes that address aspects of borders in a broad sense, namely: border crossings, escape and departure, shared (hi)stories, and arriving in a foreign country. We intertwined memories of the inner-German border with memories of border crossings, escape, and arrival in other contexts to create personal, transgenerational, transnational, and transcultural connections through shared memories.

Each group met regularly online to develop a concept and share their own memories as well as memories they collected in conversations with, among others, family members and friends. In addition to collecting memories in form of stories and interviews, participants collected objects, photos, pictures, songs, and sounds to be built into a written script for a collective motion comic. The scripts were developed conceptually and visually, together with professional artists, to create four motion comics of about ten minutes length in both English and German that could be easily shared online. The four motion comics are accessible on our project website and on YouTube. They are: ‘Border Crossings’, ‘The Density of Freedom’, ‘Friendship Beyond Borders’, and ‘Wandering Roots’.

Besides the online meetings, participants got together in two on-site workshops at the Marienborn memorial to experience the historic site in person. The first meeting was designed to help the group members to get to know each other, meet the artists, gather historical contexts, and exchange initial ideas about the project. The second workshop was a public premiere to present the motion comic to the German-speaking public. An online premiere shortly thereafter served to release the English-language version. Each motion comic was published with accompanying pedagogical material to be used in schools and other educational settings.

The ‘Ghost Train’ motion comic inspired us to initiate the ‘MoCom’ project and to get young people from diverse backgrounds involved in exploring their own and others’ shared memories. By producing stimulating educational material for themselves and their peers, these young people became actively involved in public history—about and across divides.

Reflecting the Experience: In Lieu of a Conclusion

What exactly did we create with our ‘Ghost Train’ motion comic? It is not a documentation of history, but it certainly engages people in historical discourses. Academics are only beginning to assess the potential of motion comics for history education (Hashim and Idris 2016; Morton 2015). From the experience with our motion comic, we gather that motion comics, because they are pieces of art, can add additional layers to history work. They do so by working with and addressing emotions, thus becoming (e-)motion comics in the process of connecting people across divides, time, and space.

As a form of oral history, motion comics stress emotions in historical work by engaging the producers as well as the viewers with a theme from history by way of personal memories. The collage of different memories allows those who are involved to create a multi-layered vision of an historical instance as a shared group experience (in contrast to a personal experience) in a liberating, artistic fashion. In this process, the participating individuals add their personal perspectives to create something new that keeps growing as people continue to join the process by watching and commenting, thus establishing a dialogue across divides, time, and space.

As a piece of artwork—and of course, the lines are not clearly drawn between the historical and the artistic aspects; rather, they are blurred and sometimes hardly distinguishable—the motion comic addresses the senses. It evokes emotions that may have a soothing or even a healing effect. At least, this is our experience with this particular motion comic. The result is a multi-faceted dialogue that draws on aesthetic values as much as on memories of actual historical events.

For its ability to engage viewers emotionally, the (e-)motion comic as a concept deserves further application in public history education. It has the potential to draw people into historical reappraisals who might not do so otherwise. The medium of the (e-)motion comic offers a low threshold for bringing history to life, providing information, offering connecting points to unleash related personal memories, and, thus, nudging people to ask questions or simply to think about what is—or was—happening.

We would like to invite you, too, to share what came to your mind while watching our memory story. Were you reminded of a similar experience, of an emotion, a smell, a sound, a scene from your childhood? Are you irritated by ‘inaccurate’ details (as we suggested above, there are some; our memories are able to transform the past, and, after all, the motion comic is also a form of art)? Could such ‘inaccuracies’ have a productive effect on your memory work? Please share your reaction to the ‘Ghost Train’ motion comic and become part of the ‘Cold War Childhoods’ memory archive.5

References

Davies, B., and Gannon, S. (eds). (2006). Doing Collective Biography: Investigating the Production of Subjectivity. Open University Press

Fichtner, S., Werner, A., Aghalouie, A., Tavakoli, H. (2020). ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West Berlin’. YouTube, uploaded by Medienwerkstatt Encounters, 8–9 November 2020, English version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvoAOMDLszk

German version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6NaKHmVRac8

Hashim, M. E. A. H. B., and Idris, M. Z. (2016). ‘Theoretical Framework and Development Motion Comic Instrument as Teaching Method for History Subject’. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6(11), 249–60, https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v6-i11/2394

Mazzei, L. A. (2003). ‘Inhabited Silences: In Pursuit of a Muffled Subtext’. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(3), 355–68, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800403009003002

‘MoCom—Motion Comics as Memory Work’, https://mocom-memories.de/en/home/

Morton, D. (2015). ‘The Unfortunates: Towards a History and Definition of the Motion Comic’. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 6(4), 347–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2015.1039142

‘Spinning the Sticky Threads of Childhood Memories: From Cold War to Anthropocene’. (2021). Tampere University, https://events.tuni.fi/recollectreconnect2021/

Silova, I.; Piattoeva, N.; Millei, Z. (eds). (2018). Childhood and Schooling in (Post)Socialist Societies: Memories of Everyday Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62791-5

Smith, C. (2015). ‘Motion Comics: The Emergence of a Hybrid Medium’. Writing Visual Culture, 7, https://www.herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/100791/wvc-dc7-smith.pdf

1 The motion comic was realised thanks to the generous support of the Kone Foundation, Finland, which financed the Reconnect/Recollect project.

2 Sarah Fichtner, Anja Werner, Azam Aghalouie, Hassan Tavakoli (2020). ‘Ghost Train—Memories of Ghost Trains and Ghost Stations in Former East and West Berlin’. YouTube, uploaded by Medienwerkstatt Encounters, 8–9 November 2020, English version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvoAOMDLszk

German version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6NaKHmVRac8

3 We would like to thank all the people who got in touch with us sharing their experiences, memories, and emotions as they watched this motion comic.

4 For more information on the ‘MoCom’ project, see https://mocom-memories.de/en/home/

5 Please use this template, indicating that your comments are connected to the ‘Ghost Train’ motion comic: https://coldwarchildhoods.org/sharing-memories/