16. Re-membering Ceremonies:

Childhood Memories of Our Relationships with Plants

© 2024 Jieyu Jiang et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.16

Drawing on collective biography, memory work, and diffractive analysis, this chapter examines childhood memories of our entanglements with plants. By approaching research as a ceremony, our goal is to reanimate the relationships we have shared with plants and places, illuminating multiple intra-actions and weaving different worlds together. Our collective ceremony of re-membering brings into focus how plants called us forward, evoked our gratitude and reciprocity, shared knowledge, and offered comfort, companionship, love, belongingness, and understanding throughout life. The process of our collective re-membering and writing has turned into a series of ceremonial gatherings and practices, bringing forth vivid memories, poetic expressions, and creative drawings. As humans, we have often (re)acted to plants’ generous gifts in meaningful gestures and communications that have co-created and made visible our deeply felt inter-species love and care.

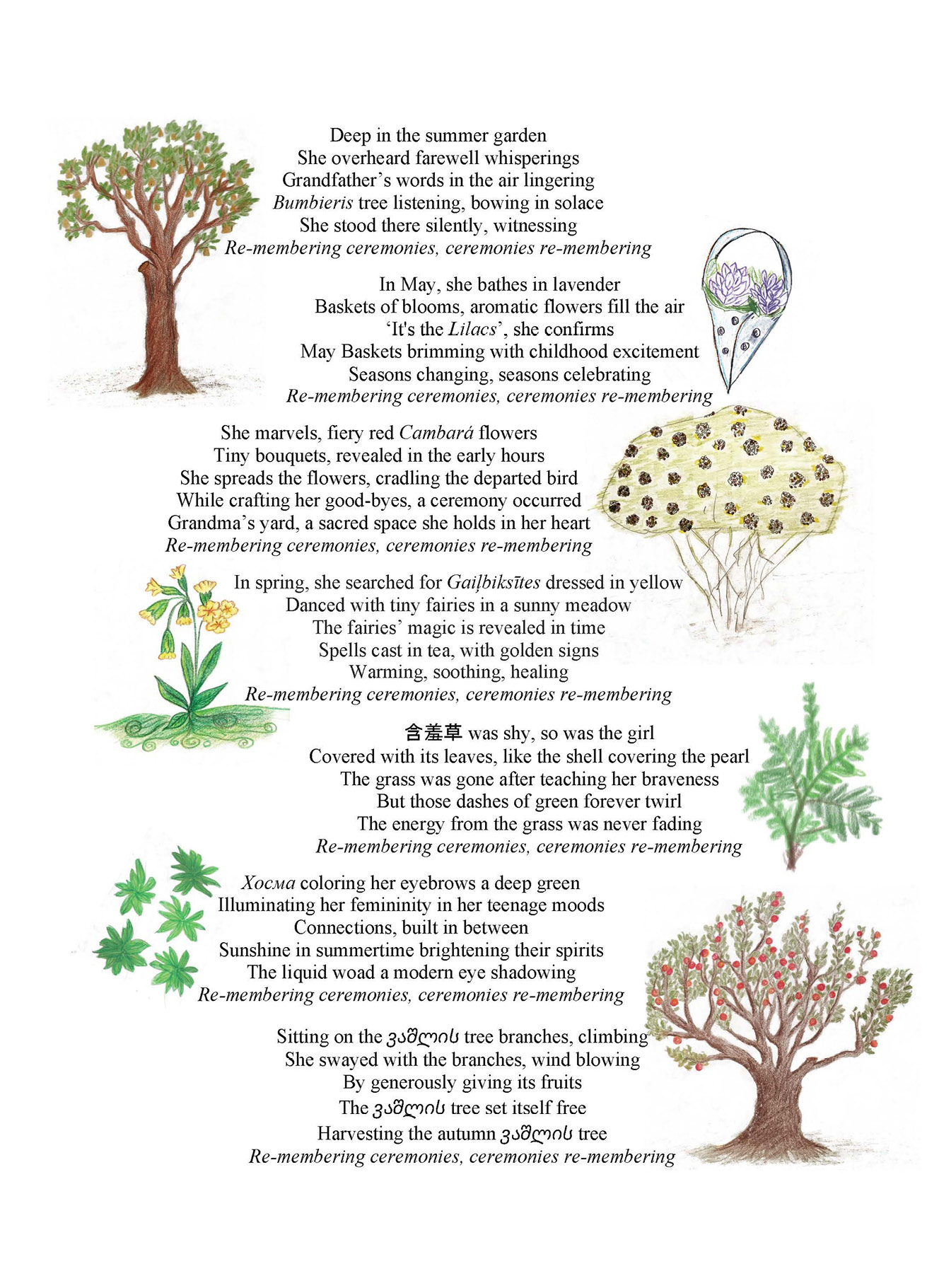

Fig. 16.1 Authors’ drawings and invocation: a ceremony of re-membering our relationships with plants. Jiang, Pretti, Tsotniashvili, Anayatova, Nielsen, Silova, 2023.

Weaving together our childhood memories across space and time, this poem is our collective invocation that marks a ceremony of re-membering our relationships with plants (Figure 16.1). Both personal and shared, it is a belated message of gratitude to our plant companions—flowers, shrubs, herbs, and trees—for inviting us into more-than-human relationships decades ago. It is also a humble gesture of reciprocity to honour and rekindle these special relationships despite modern pressure and expectation to distance ourselves from the living world. Our intention is to reconnect with our plant companions through childhood memories, rebuilding ‘the connections and relationships that are us, our world, our existence’ (Wilson 2008, p. 137), and in this process, remind ourselves and our readers that ‘the world could well be otherwise’ (Kimmerer 2013, p. 189)—more connected, interdependent, and reciprocal.

In the anthropocentric age where life is dominated by institutions of modernity, whether socialist or capitalist, the beat of ‘progress’ undermines our capacity to pause and notice the infinite ways of being in the animate world. At the same time, hierarchical binaries that dominate western culture—nature/culture, female/male, matter/mind—hyper-separate humans from the ecological communities we inhabit, while relegating the non-human ‘other’ to oppositional subordination (Plumwood 2009). As children, we speak with plants and animals as if they are our kin. But as we grow older, we are quickly retrained to abandon and forget these relationships. As Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013) explains, when we tell children that ‘the tree is not a who, but an it, we make that maple an object; we put a barrier between us, absolving ourselves of moral responsibility and opening the door to exploitation’ (p. 57, emphasis in original). And yet, even as ‘the language of animacy teeters on extinction’, Kimmerer (2013) reminds us that ‘the animacy of the world is something we already know’ (p. 57), even if we may be forgetting some of its grammar. It is always already part of us, quietly kept in our memories, carried in our bodies.

In this chapter, we invoke our plant companions from childhood and beyond, zooming out of the Cold-War era and bringing into focus multi-species relationships with a longer history and future than the Cold War. On both sides of the Iron Curtain, our plant companions taught us to stay present in the moment, paying attention to ‘here’ and ‘now’ rather than worrying about the past and the future. Cambará, an inexpensive ornamental bush commonly known as ‘lantana’, bloomed by a grandmother’s yard wall in a working-class home in urban Brazil, embracing and enchanting little girls. 含羞草 (pronounced as Han Xiu Cao in Chinese and identified as mimosa pudica in Latin) grew by the school gates in southern China and was known for its special ability to close leaves like a book, ‘with a shy look’ (‘含羞’ or Han Xiu), if anyone touched it. An apple orchard in Georgia was fondly re-membered as ვაშლის ბაღი (pronounced as vashlis baghi in Georgian) for bringing families together for the ceremonial act of apple harvesting. A bumbieris (‘pear’ in English) tree stood tall in a grandmother’s garden and a delicate primrose, or gaiļbiksīte in Latvian grew in the meadow by the river, next to the tall apartment buildings and sometimes on the edge of the forest across Latvia. Хосма (or ‘woad’ in English), a native to the steppe of Central Asia, was known for its indigo ink used for crafts, beauty, and medicine in Uighur culture. And lilacs were popular in the United States among little girls for their distinct floral scent emanating from precious ‘scratch-n-sniff’ Barbie stickers and May Basket arrangements.

By inviting our childhood plant companions into co-presence, we enter this research as ‘a ceremony that brings relationships together’ (Wilson 2008, p. 8). Turning to our childhood memories, we can hear again the quiet echo of trees whispering in our grandparents’ gardens, breeze in the scent of lilacs in May baskets and Barbie ‘scratch-n-sniff’ stickers, feel the sensation of a cold dye from a ceremonial plant on our eyebrows, and sense the love and care emanating from the delicate flowers growing by the of side of the road or in the hidden corner of a garden. And then we start to re-member things we did not know we have forgotten. In this chapter, we pick up the scattered threads and fractured glimpses of our fading childhood memories and weave them together in ritual practices to reconnect with our plant companions as kin in a more-than-human world. By coming together to share our childhood memories, the relationships between us and our plant companions—as well as the connections between our different ‘selves’ across time and space, and among each of us across different contexts and cultures—become clearer and clearer, closer and closer.

Memory Research as Ceremony

When we share our memories

We celebrate them as ceremonies

Re-membering

Sharing the wisdom of indigenous elders, Kimmerer (2013) says that ‘ceremonies are the way we “remember to remember”’ (p. 5). Whether activated through official ceremonies or everyday ritual practices, memory plays a vital role not only in sharing knowledge and experience across space and time but also in connecting human beings to both their pasts and their futures, as well as to other human and more-than-human beings. Thus, in this research, we approach working with memory from a broader ecological and Indigenous perspective, as ecomemory, where the process of re-membering links human and nonhuman beings and their entangled histories into ‘an extended multispecies frame of remembrance’ (Kennedy 2017, p. 268). From this perspective, memory—and the process of re-membering—becomes a form of connection and solidarity between humans and non-humans that enables us to re-member and re-make worlds together.

As we prepared the shared spaces and ways for ‘remembering to remember’, it seemed only fitting to approach our memory research as a ceremony itself. Wilson (2008) writes that approaching ‘research as ceremony’ helps to raise our consciousness, bring relationships together, and bridge spaces between humans and nature. In this process, not only the ‘doing’ of research is a ceremony, but our writing, too, acquires ceremonial effects—from gathering together to share our memories to inviting our plant companions to join us in re-membering our mutual relationships, to making space for multispecies awareness and ‘arts of noticing’ (Tsing 2015), to expressing gratitude for our more-than-human entanglements, to reconnecting and learning from and with our plant-kin, to creating a manuscript that can be read (and felt) as a ceremony.

Inspired by the evocative methods of collective memory work (Haug et al. 1987), collective biography (Davies and Gannon 2006, 2012; Pretti et al. 2022; Silova et al. 2018), and diffractive analysis (Barad 2007; Davies and Gannon 2012; Mazzei 2014), we start with the assumption that other ways of relating and knowing are possible, but they require that we ‘revitalize the arts of noticing’ in our research and practice (Tsing 2015, p. 37). Noticing brings the awareness of the existence of multispecies worlds and realities that we all inhabit, helping us recognise the deep and entangled histories of multispecies being and becoming, while moving us away from a binary hierarchy of othering and opposition against other species (Bozalek and Fullzgar 2022; Van Dooren et al. 2016). According to Van Dooren et al. (2016), such a multispecies approach enables research to get immersed in the ‘multitudes of lively agents that bring one another into being through entangled relations that include, but always also exceed, dynamics of predator and prey, parasite and host, researcher and researched, symbiotic partner, or indifferent neighbor’ (p. 3).

In an effort to further attune to the arts of noticing and the acts of re-membering these multispecies common worlds we inhibit(ed) (Common Worlds Research Collective 2020), we rely on the ‘sensibility of all our embodied faculties’ (Taguchi 2012, p. 272) to engage with memories that dwell in our minds and bodies, as well as material objects and natural landscapes. Our collective process of re-membering entails several processes of engagement: (i) re-membering our relationships with plants and sharing our memory stories with each other; (ii) carefully listening, reading, and re-reading each other’s memory stories to bring more details into focus; (iii) noticing the interferences and threads running through each other’s memory stories; and (iv) weaving the different memories together by reading memory stories through one another. Instead of reflecting on our experiences, we engaged in a diffractive analysis of memory stories (Barad 2007) by attentively reading memories through one another, recognising differences and similarities, while paying attention to our entangled relationships with other species. In the process of reading and re-reading each other’s memories diffractively, we recognised the deep interconnectedness of our childhood memory stories that transpired across four different continents and six countries.

Across different contexts and time periods, our plant companions often invited us into ceremonial acts and rituals during our different life transitions, our teaching and learning processes, and our personal and collective growth. Kimmerer (2013) explains that ‘ceremonies large and small have the power to focus attention to a way of living awake in the world. The visible becomes invisible’ (p. 36). Our childhood ceremonies with plants were simple acts that helped us focus our attention on the (sometimes) invisible multiplicity of life in the world. Through the processes of collective memory work—what we call here, the ceremonies of re-membering—we have become aware of how the barriers between us and plants began to disappear, revealing the coexistence of deeply entangled multispecies worlds, which we have always already belonged to. In our intra-active research process, we thus became writers and readers of/with the memory stories (Haraway 2016). In the sections below we share our childhood memory stories, highlighting through our ceremonies of re-membering how we communicated, learned, and bonded with our plant companions and the land we shared. We illustrate how plants have inspired us to express gratitude and practice reciprocity, taught us to communicate with a more-than-human world, shared lessons beyond binaries and categories, and helped us reconnect with the multiple worlds we have inhabited in our lifetimes.

Ceremonies of Gratitude and Reciprocity

When we recall our memories

Our hearts fill with appreciation

With gratitude for old friends

Thankful for otherworldly connections

Ceremonies can be performed both as single acts, and as well as a broader way of being in the world—a gratitude-based way of living—that focuses human attention on an ethical relationality in/with other species (Kimmerer 2013). Gestures of appreciation and gratitude for the land are ceremonial acts that occur through ‘ritual(s) of respect: the translation of reverence and intention into action’ (ibid., p. 35). Additionally, Moore and Miller (2018) detail how gratitude connects us to the earth and strengthens human relationship to the natural world. Thus, the expression of gratitude between humans and non-humans can be a form of ceremonial practice that builds and strengthens connection, and establishes a relationship of care and reciprocity, while recognising mutual interdependence (Kimmerer 2013; Moore and Miller 2018).

The ceremonies we witnessed and participated in as children enmeshed us in plantworlds, attuning us to the characters, doings, and movements of plants. They helped us recognise invisible qualities of plants by channelling our attention to the many possibilities of intra-acting with each of them (Barad 2007). In our childhood memories, ceremonial acts of gratitude for the land and for plants were abundant, human and non-human beings showed appreciation and reverence towards one another in gentle ceremonial intra-actions that connected them through very deep bonds. In the company of our elders, both human and vegetal, we observed and experimented with our arts of noticing, performing our own playful ceremonies, plucking flowers to make wishes, extracting tint to wear as ceremonial makeup, listening to the sounds of morning greetings and afternoon goodbyes. These plants entered our worlds and invited us to enter theirs by our mutual openness in reciprocal more-than-human relationships.

Kimmerer (2013) explains that attentive engagement in/with plant worlds is accessible through remembering. As adults immersed in modernity, we may have forgotten how to communicate and engage in ceremonial acts with plants, but the ability to attune to other worlds, including plant worlds, is available to us as we re-member past encounters (Pretti et al. 2022). Thus, re-membering our childhood ceremonies, such as memories of accepting an apple tree’s invitation to climb it or of talking to a shy plant, is a path to re-member how to engage with plants as kin and, moreover, to be re-minded that an attuned, gratitude-based existence is not something to be learned (or re-learned) but something to re-member.

Ceremonial expressions of gratitude were abundant in our memories. In one recollection, a girl showed delicate awareness and care for her grandfather’s ვაშლის ბაღი (apple orchard) in rural Georgia by joining her family in the yearly apple-picking season, and attentively accepting an apple tree’s invitation to climb it and gently relieve the trees of their heavy fruits:

It is apple picking season, everyone is trying to make it to the village for the weekend to help grandparents with harvesting. The girl is the youngest, and she starts climbing the tree with her bucket and picking the apples. The trees are about 8–10 meters high. She knows that she can reach the branches that others cannot. She feels it is risky to go on higher and thinner branches, especially when the wind is shaking the branches on which she stands or holds on. To reach the apples, she pulls down a branch with one hand and picks the apples with the other. As the branch gets free from the fruit and she lets it go, the branch jumps higher and the girl feels that she is liberating the branches from the heavyweight. She gets more enthusiastic to reach the thinner branches that might be broken if they cannot hold the fruit weight. She also enjoys taking breaks by sitting on the convenient branch and eating apples. Although she gets tired and feels pain in her feet, she wants to relieve the trees from the burden and moves from one branch to another and then to another tree.

In this memory the girl re-members her agility and familiarity with apple trees, gently using her body to reach the fruits and relieve the trees’ branches, preventing them from breaking. She is happy to join in the ritual of apple picking, she is gentle and careful, enjoying the trees’ company and fruits while working with her human and more-than-human family.

Examples of such connection and care emerged in other memories as well. In a quiet backyard in Brazil, another girl regularly visited grandma’s Cambará plant to admire and confide in her vegetal friend, exchanging awe and tenderness with the delicate flowers. In another memory, across the world, a young girl in China used only her heart to speak to a shy plant in order to avoid disturbing such a sensitive being. These simple acts of tenderness and respect were all constituted of ritual visits and ceremonial gestures of appreciation and care for those plants.

While sharing memories and following the many sprouts that emerged from plant ceremonies, we noticed that once we practised our gestures of gratitude towards the land and the plants, we were immediately recognised and reciprocated by the plant world. ‘The land knows you, even when you are lost’, Kimmerer (2013) explains. Similarly, Moore and Miller (2018) affirm that ‘as soon as you give thanks to something it gives thanks back’ (p. 5). As expected, the girl in the apple orchard receives the tree’s recognition and gratitude in return. The girl re-members how the trees’ branches jumped with relief when their apples were harvested, and how she was delicately held by the tree even when climbing the thinner branches:

The girl has been climbing on the trees for as long as she re-members herself, she can sense how much pressure she can put on and distribute on the branches so that they don’t break, and she trusts that the branches will also hold her.

Similarly, in Kazakhstan, a girl’s grandmother showed respect for the Хосма [woad] plant by seeding it every spring and picking only a small amount of leaves in the summer. By respecting the plant’s life cycle and nurturing its growth and regeneration, the girl’s family and Хосма developed a ritual of care and affection. In reciprocity for the generous contribution to its regeneration, Хосма helped the girls in the family transition from childhood to adulthood through the ritual of painting the eyebrows and eyelids. In this intergenerational interspecies relationship of mutual care, Хосма mediated an important transition in the lives of all women in the family and in the village:

Хосма is my grandmother’s favorite plant. She seeds it every spring in small quantities, and in summer, the grandmother is ready to use. My cousin goes and harvests a handful of leaves after. I squeeze woad’s leaves with the help of my hands. Here we go. There is a dark green liquid that is put on brows. I was eight or ten when I knew I wanted to have dark and beautiful eyebrows. Another important thing was putting the liquid on the eyelids as a modern eye shadow. Nevertheless, only older girls can do it, so we, as eight-ten-year-olds, were jealous of our older girls putting them on. We wanted to be older, and we wanted to be beautiful like them. I remember my cousin or aunt or mom painting my eyebrows. This event was fascinating to all of us—sitting in the circle, talking about different things, laughing was an integral part of painting woad liquid on our faces.

These multispecies exchanges of care, trust, gratitude, and reciprocity strengthened the bonds between the plants and humans, revealing wisdoms that can be accessed and created by the entanglements between humans, non-humans, landscapes, ceremonies, and memories (Basso 1996; Moore and Miller 2018).

Ceremonies of Communicating with Plants

When we recall our memories

Each season invites us to participate

In weaving our bodies together

Our childhood memories of entanglements with plant worlds tell about our attunement to the rhythms, cycles, and doings of more-than-human others. Some of our plant companions blended into landscapes, going mostly unnoticed, while others grew seasonally, appearing at certain times of the year, letting us know of changes about to come. Taking cues and listening to how and when plants grew, reproduced, and withered, we learned the language of plants, and learned how to communicate back with them through words, actions, emotions, touch, and thoughts. In these reciprocal cycles of communication, we were ‘linked in a co-evolutionary cycle’ (Kimmerer 2013, p. 124), wherein humans and plants benefitted from our spoken and unspoken communications. Plants communicated with us by their growth, their strength in holding us, their comfort in moments of grief and sadness, and their assistance in life’s transitions. They were part of our own ceremonies and invited us into their rituals and cycles, being constant companions across our memories. While ceremonies and rituals are typically studied through the lens of human culture, they are also part of non-human worlds. We noted that the ceremonies and rituals across our memories communicated local traditions and shared knowledge as a ‘crystallization of the collective wisdom’ (Zheng 2018, p. 817). An example can be seen in the memory of the girl who used Cambará flowers in a funeral ceremony for her deceased bird. The memory communicated how the girl went to her plant friend to find strength, peace, and joy in a time of sorrow.

In our memories, we often became part of plant ceremonies and rituals already underway. The cyclical arrival of warmer weather, blossoms, and plants bearing fruit were direct communications from the plant world that it was time for seasonal ceremonies and local rituals such as apple picking or eye shadowing. In these instances, ceremonies and rituals ‘married the mundane to the sacred’ (Kimmerer 2013, p. 37), mediating the intersection of plant and human rituals. For example, the arrival of the spring season communicated the arrival of the May Day celebration where children gathered flowers in May basket arrangements to hang on neighbours’ doors. In this memory, May baskets marked a seasonal ritual shared within the local community.

After they talked about a May Pole and the May Day Celebration at school, the girl came home from school and made May Baskets for her neighbor. Her mom gave her some chocolate candies to put inside and she went outside to pick some flowers from the front yard. She didn’t really have many flowers in her front yard so she wandered around the houses close to hers and found some flowers from a neighbor’s yard. They were little lavender flowers, the kind that smelled just like the Barbie stickers she loved. The basket was loaded with flowers and chocolates and smelled of a sweet spring. She was ready for delivery when the sun was beginning to set; the spring weather was warming up and the low sun cast a golden hue to everything as it neared time to deliver the May basket.

In this memory, ordinary flowers found in yards and gardens were transformed into ceremonial symbols of love and friendship, which were shared with neighbours and friends during our ceremonies. Kimmerer (2013) describes how gardens (and flowers) reflect both spiritual and material matterings, the May-Day flowers symbolised the relationality of being ‘loving and being loved in return’ (Kimmerer 2013, p. 123).

In another memory, a girl learned to communicate directly with plants by secretly observing her grandfather’s farewell to his plant companions in the garden before an unexpected surgery. In this memory, the girl remembers her grandfather’s vulnerability when he was communicating with the plants:

The girl spent most of her summers in the family summer garden, which was located close to the small town where they lived in an apartment building. But one day something unusual happened. The girl was surprised and curious to see her Grandfather alone in the garden. She kept very quiet and pretended not to notice him, digging a hole way deeper than she intended and hoping that she would hear snippets of the conversation between her Grandfather and the plants. The wind was blowing quietly through the garden and it felt very warm on her skin. The wind carried only some words to the girl, but she knew that her Grandfather was saying goodbye to the garden—apple trees, pear trees, the currant bushes, the peas weaving on the fence around the yard. He paused for a long time next to the bumbieris (pear) tree, which was bowing low, her branches full of fruit and close to breaking from the heavyweight she had to carry. The tree seemed to bow even lower after the conversation with the Grandfather. It was a day before her grandfather went to a hospital for a surgery, leaving the small town in the countryside to go to the capital city.

The girl was fascinated by how the grandfather took time to speak with each plant, ‘gently touching the leaves of the berry bushes and the bark on the trunks of the fruit trees, she suddenly realised the significance of the upcoming surgery and the significance of the garden in his life, and her life too’. In this memory, it is not only the vulnerable connection between the grandfather and the plants that is striking but also the connection that was created between the girl and her grandfather through the plants. The narrator of this memory later noted, ‘It was special that he shared this moment with me. [We] both knew that we were in each other’s presence at that moment, but neither one spoke about it at that time or afterwards’. The grandfather allowed the girl to witness his conversation with plants so that she could see how they were important members of the family. As he communicated his goodbyes, the grandfather modelled for the young girl his knowledge that ‘each place was inspirited, was home to others before we arrived and long after we left’ (ibid., p. 34). Communicating with plants through whispered prayers and good-byes was ritual in itself (Siragusa et al. 2020) and, as the young girl witnessed, she learned that she too could trust her plant companions in the gardens. Grandfather’s goodbye ceremony reminds us how plants are natural listeners and can help us in the transition between worlds. In this sense, our plant ceremonies served as a channel for us to better understand how we were connected to our worlds, our families (both living and ancestral), our cultures, and our lands.

Ceremonies of Teaching and Learning

When we recall our memories

We celebrate the wisdom of nature’s teachers

Humbled by ancient pedagogies

We learn to live together, live in love

Kimmerer (2013) tells a story about Skywoman leaving plants behind as our teachers. Across our memories, we commonly see plants as teachers, noting how their teachings are distinct from regular lessons at school. In mainstream Western school pedagogies, we learn about plants in a scientific way, reducing plants to their classifications and biological qualities (Kimmerer 2013). Fundamentally, modern schools inculcate and discipline us to learn one hegemonic way of relating to plants, that of scientific knowledge-making, relegating plants to a place of separation, ‘othering’—framed as exploitable objects to be grown, used, and destroyed by humans (Haraway 2016)—rather than companions or ‘teachers’, able to link us in and through learning processes as a ‘connective tissue’ between different worlds (Warner 2007, p. 17, see also Silova 2020). Along with the ‘knowledge’ about plants, our learning at school was limited to ‘scientific descriptions’ and pictures of pressed specimens in textbooks and labs. In this process, we lost opportunities of building intimate connections with plants, experiencing emotions together, gently touching each other’s vivid lives, as well as learning from each other through warm and comfortable connections (Kimmerer 2013). From the scientific learning process to the scientific knowledge per se, modern schools give full expression to human arrogance and human-centric ontology (Silova et al. 2020; Stengers 2012), while closing the doors to other worlds.

In our childhood memories, however, we re-member a different kind of pedagogy by learning with and from the plants (not only about them), transforming and expanding learning from solely mental and cognitive processes to our bodily, emotional, and spiritual learning. The relational learning between the girls and the plants reveals ‘the matter that matters’ (Barad 2007, p. 210) in each moment uncovering possibilities to notice, learn, and re-member through movements, fragrances, pigmentation, taste, and our physical and emotional connection with the plant world. Our childhood memories with plants suggest that teaching happens in every ceremonial moment when beings express mutual aspiration and initiate reciprocal understanding of each other, regardless of categories of beings, educational settings, and the hierarchies of knowledge. In other words, plants could be our teachers, teaching and inspiring us in a more ceremonial way, about how to connect and live sympoietically in more-than-human worlds. In one memory, for example, the girl communicated with 含羞草 (the Mimosa pudica) about the sensitivity, cowardice, and bashfulness in her personality, while the flower provided the girl with courage and bonded understanding. At that ceremonial moment, the plant taught her to be brave and confident in acknowledging and accepting the true but different self when being with others:

Every time after school when she walked along the rows of 含羞草 (mimosa pudica), she would stop and look at them quietly. She did not talk to or touch them, but only squatted down, looked at them, observed them, and said ‘hi’ in her heart to them. She thought that even talking loudly would make them close their leaves. ‘I don’t want to bother them. They prefer to hide themselves because they are too shy.’ She said to herself, ‘it is not a big deal, see, the plants are sensitive, too, and there are specific sensitive plants. It is the same for people like me. I am not strange. It is okay to be shy.’ She thought with hope and thrill, and suddenly she felt the energy of the plant, because they were not plants anymore—they were similar kinds of beings with similar characteristics. They are her close friends, even though they never had conversations out loud. Every time she quietly walked past them, they seemed to be talking to her: ‘Be strong and be yourself—we are all quiet and it is okay to act like that in school.

As we noticed similar ceremonial moments of learning from plants in our childhood memories, we began weaving our memory stories together. We regard our childhood memories and interactions with plants as ceremonial teaching and learning experiences for three reasons, each of which highlights an aspect of difference from mainstream pedagogies. First, the processes of teaching and learning in our memories with plants were not linear or progressive, unlike those typically found in schools. Rather, the girls’ memories describe the so-called teaching and learning experiences that happened in our connections and communications with the respective plant companions naturally, iteratively, and periodically. In other words, there was neither an established route and procedure for successfully achieving pedagogical aims, nor prescribed scientific steps and schedule to realise the illusion of making educational progress.

We re-membered and experienced diverse types of relationships with plants, which were filled with emotion, love, and sincerity, and which emerged again and again in our lives. For example, in the family garden where the girl spent most of her time during the summer, she learned about different types of garden work, meeting different berry bushes, and learning to make friends with the garden plants through multiple communications and visits. More importantly, at a deeper level, when she saw her grandfather stopping and saying goodbye to the bushes and trees, and when those plants responded to her grandfather and comforted his fear of separation by offering their quiet company, the garden plants became her teachers in facing life’s difficult moments. These ‘teacher-student’ relationships were built upon the girl’s periodical and iterative intra-actions with plants in the garden over several summers. Those subtle moments of communication transformed into emotional ceremonies, during which plants and bushes taught the girl about the reluctance of farewells, the comfort of companionship, and the mood of optimism when facing bumps in life.

Another important distinction is the relatively equal positions of teachers and learners. In the girls’ memories, we were in contact with the plants who could be regarded as teachers, in the capacity as children with our simplicity, kindness, and careful attempt. From the girls’ perspectives, although we were born and grew up in the group of human beings, there was no prejudice and arrogance in a sense of knowing and interacting with other species, including plants. From a learners’ view, the botanic ‘teachers’ for us were not as unapproachable as the teachers in formal classrooms. Plants were unable to talk, but they taught through generous companionship, comfort, and patience. For instance, in the memory of harvesting apples, the girl felt the branches of the tree supporting her, bouncing and playing together, and generously sharing the fruit. In another memory of a teenage girl, the squeezed leaves of the woad plant produced a dark green liquid, which then transformed into a natural eyebrow dye, teaching her the feeling of beauty, the wish of growing up, and the joy of practising in the ceremony together with her peers. In our childhood memories of teaching and learning, the plants and us were equally different, and the bonding between us was woven based on an equal relationship of knowing each other. In this sense, the regular mode of teacher-centred or student-centred learning was challenged and changed. Instead, the relationships of interdependence and reciprocity constituted ceremonies where every being—human and more-than-human—was included and warmly affected.

Furthermore, the content of our teaching and learning with plants was different compared to modern schools which define knowledge in narrow, fragmented, and programmed ways. The girls’ memories talk about learning as a ceremony filled with love, relief, displays of natural emotions, and unique bondings. For example, the cyclical elapse of time was taught by the plants in May, and so it was re-membered by the girl in a beautiful and ceremonial way for life. By preparing her May basket, the purple lilacs and their ‘sweet spring’ fragrance helped the girl experience and re-member the May-Day celebration, her lovely friendship, and the passing of time in a sensory as well as natural way. What the lilacs shared with the girl was the cyclical nature of time, the ritual of enjoying friendship, and celebrating holidays and seasons in the lapsing time.

Finally, the unique teaching and learning experiences with plants were always intimate encounters that favoured exploring multiple worlds and building connections and relationships with more-than-human beings. An example happened in a memory with the Cambará bush, when the girl is being called by the flowers. She attends to the call, touches the flowers, picking only a few and arranging them in her hair, while visiting the private and quiet place under the bush again and again. These experiences formed a special bond between the girl and Cambará, in childhood and beyond. Cambará was not a regular or common bush anymore but a dedicated companion that helped the girl to understand and experience connections with different beings.

Ceremonies of Reconnecting with the More-than-Human World

When we share our memories, we intertwine

In rhizomatic relationships, silent connections

The fibers link ritually between multiple worlds

Maintaining connections through devout affections

Every connection we made with plants and every ceremony of re-membering took us back in time and in space, opening up possibilities to explore our connections to plants, to places, and to our (multiple) selves. Attachment to and rootedness in place is reinforced in memory work (Lewicka 2013), which can be seen in the girls’ memories as they re-membered past and current houses, villages, cities, and, in most of them, their countries. Moreover, relationships with plants created an emotional belonging to a particular place, ‘anchoring emotions of attachment, feelings of belonging, willingness to stay close, and a wish to come back when away’ (Lewicka 2013, p. 66). Working with memories of close relationships with plants, we are able to restore intimate attachments to the plants and reconnect our ties to the land.

In talking about home and land, Kimmerer (2013) describes how plants, or memories about plants, have the ability to re-connect us with our ‘home’. She writes that plants are ‘integral to reweaving the connection between land and people. A place becomes a home when it sustains you when it feeds you in the body as well as spirit. To recreate a home, the plants must also return’ (p. 259). In one example of our memories, the gaiļbiksīte (primrose) flower comes back into the girl’s life again and again across many years, reminding the girl of knowledge she had forgotten and rekindling their relationship:

There was a small yellow flower, which would appear in a girl’s life in most expected and unexpected times. It bloomed in late spring, usually in May and early June, when the days were becoming longer and warmer in Latvia, and the sun would not set until way after the girl’s bed time. The flower would appear in the meadow by the river, next to the apartment building where the girl lived, and sometimes on the edge of the forest nearby. It was a delicate light green stem crowned by a cluster of small yellow flowers, which had a soft sweet fragrance. To the little girl, who was about 5 or 6 years old at that time, they looked like fairy princesses, so small you could hardly notice the beautiful yellow and green lace on their dresses. When the girl grew a little older, around 10–11 years old, the fairy princesses showed up at school. In a botany lesson, she saw them in her textbook. She learned that the flower was called Primula Veris in Latin. Several years later, when the girl was 15 or 16 years old, she was at home, drinking herbal tea on one late winter day. She had a cold and her mom made a special tea from a mixture of several different herbs. The tea was soothing and sweet. The girl recognised a special fragrance of the yellow fairy princesses as she drank it. The smell took her into the yellow fields by the edge of the forest that day. The sun was high in the sky and it made her warm. Many years passed by. The girl did not think about the yellow princesses for a long time. But one day she went to an exhibition in a capital city, far away from her home. It was in a building of the former biology department of the university, which was converted to a museum. She entered one of the rooms, which had glass cabinets on each wall. Behind the glass were lots and lots of dry flowers and grasses. Each one had a tag with a Latin name and a scientific description. Little princesses were there, too. ‘Primula Veris’, the tag said.

Connection with home and land is one of the vital aspects of childhood memories, and thus, present in all of our memories. At Oma’s garden in Latvia, where grandfather said goodbye to the plants, by the Cambará bush in another grandmother’s garden in Brazil, and in the Kazakhstan village where the woad was seeded every spring, the girls developed deep emotional and physical connections to the plants and the land through meaningful ceremonies, and they were relived those decades later, with the help of memories. According to Kohn (2013), ‘there is something about our everyday engagements with other kinds of creatures that can open new kinds of possibilities for relating and understanding’ (p. 7, see also Haraway 2008). These deep connections and communications with plants rooted in familiar land were ceremonial entries into multi-species relationships in girls’ stories. These common worlding ceremonies strengthened a deep intimate relationship with plants and places, making it possible for the girls to re-member important knowledges, connections, and possibilities of relating to non-human beings (Pretti et al. 2022). For example, a place is ‘comforting and comfortable’ in the grandfather’s goodbye memory. Similarly, a little girl finds comfort in the presence of the Cambará bush, which became a ‘private sacred place of communion with loss, and a place to connect with her own feelings and with the plants in grandma’s yard’:

The girl was about five years old, and she spent a lot of time at her grandmother’s house. Her family lived on the same street as Grandma, and very early in the mornings, the girl’s grandmother would go out to the yard to water her garden and tend to the plants. The girl always followed Grandma. The girl wandered into the darker colder area of the yard by the wall and found a flat spot where there was a Cambará bush. The tiny multi-coloured bouquet-like flowers enchanted the girl, and the bouquets were so full that the girl could pick several flowers without her aunt noticing much damage to the plant. The girl started to visit her Cambará bush alone when her cousins were not around, and delicately touched the flowers before picking them to play love me, love me not, or arrange them in her hair as she explored the garden with grandma before the day began. Grandma didn’t mind, instead, she looked over from time to time, in between talking to her own favorite plants. Soon after, when the girl’s bird died, she wanted to bury it next to the Cambará bush. Her older brother got a small cardboard box, and they filled the box with Cambará flowers around the green parakeet’s body. It gave the girl some comfort that the flowers that she knew and loved would keep her bird company, and it also gave her comfort to know that she could visit the Cambará bush later, and be with them both.

These multispecies ceremonial acts in our memories blur the western unidirectional lines of agency, profoundly re-minding us of our already ongoing connections with our more-than-human companions. The girls were growing in kinship with the land, bonding deeply with their non-human friends and teachers, with no categorisations or hierarchies between them in girls’ memories. Wynter’s (1984) concept of We/I as ‘natural beings’ mirrors this dynamic in re-membering the girls’ intra-actions with plants by showing how the boundary-maintaining system becomes subversively blurred and reconfigured through memory. Re-membering and re-connecting with plants thus reconfigures our relationships to the land—the places we inhabited in the past, and the places where we live now.

In Lieu of Conclusion: Re-membering Ceremonies, Reconnecting Across Worlds

Memories dwell in most common, but often unexpected, places. They root in our physical bodies, material objects, and natural environments. They intersect personal histories, social orders, and geological landscapes. They encompass cognitive processes and affective dimensions. And most definitely, they do not exclusively belong to the human domain (Pretti et al. 2022). Therefore, it is not only the single dimension or aspect of reality that exists in re-membering, but the fuzzy, marginalised, and fluid details across the boundaries among multiple worlds are also embedded in our memories. Memories build bridges between worlds and species by connecting us with each other. In a reiterative, cyclical, and community-oriented process, working with memories invites more memories from various worlds: ‘You hear one memory, you tell one’ (see introductory chapter by Mnemo ZIN).

In the process of our collective-biography research, we have noticed that the memory research itself has ceremonial effects, unexpectedly forming a ritual of collectively coming together to share memory stories and connecting memories and relationships across time and space. Whether meeting physically or virtually, our research gatherings involved elements commonly present in more formal rituals and ceremonies: from sharing space and taking turns to share memory stories, to purposefully seeking links to the past and creating a communal experience where everyone participates not only intellectually but also intensely emotionally. While our childhood memories were shared, heard, and written in our gatherings again and again, we felt that this research process and writing was ‘the climax of the ceremony’ for ‘it all comes together and all those connections are made’ (Wilson 2008, p. 122). At this climax of the research, we wove together our scattered memories from distant childhoods, strengthening the connections with each other—memories, plants, and us—and transforming them into a spiritual and creative composition.

Our ceremonial re-membering of the relationships with plants awoke our attentiveness, enabling us to experience how the ‘arts of noticing’ extended our ways of being and knowing to the multispecies world, reminding us about the frames of our daily lives and that the ‘making worlds is not limited to humans’ (Tsing 2015, p. 22). In the collective process of re-membering, we helped each other to delve into the physical, sensorial, and emotional layers of our memories, which opened up the space to re-connect with the more-than-human worlds and to notice what had gone unnoticed in our daily lives in the anthropocene. Therefore, through our ceremonial research we re-membered not only the stories of our relationships with the plants, but we also retrieved and revived our noticing abilities from our childhood that had been fading throughout our life course shaped by the concept of modernity and mainstream western pedagogy. We re-membered the textures, smells, and colours through our bodily and sensory memories; we re-membered dazzlingly intimate emotional relationships with the plants that enabled us to become vulnerable and feel reciprocal trust, love, care, and gratitude; we re-membered experiencing the healing power of plants. Memories of such intimate relationships with plants created space for us to explore, experience, and re-learn ways of being and knowing without fear, helping us to once again ‘come into coexistence with others’ (Malone and Fullagar 2022, p. 116).

While re-learning the ability to engage in a collective re-membering ceremony with the multispecies world, we were also reminded that ours was never a unidirectional relationship with plants. It was always a reciprocal ceremony accomplished by the connected and collective ‘us’. We would like to close with the poetic expression of love and gratitude to our plant companions:

Re-membering with gratitude and reciprocity

Rekindled care through ceremonial memory

Mutually communicating with plants

Hearing the wind and flowers chant

Plantcestors as our life teachers

Learning from all nature’s creatures

Reconnecting with more-than-humans

We cross the worlds through ceremonies

References

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv12101zq

Basso, K. H. (1996). Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. University of New Mexico Press

Bozalek, V. and Fullagar, S. (2022). ‘Noticing’, in A Glossary for Doing Postqualitative, New Materialist and Critical Posthumanist Research across Disciplines, ed. by K. Murris. (pp. 94–95). Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003041153

Common Worlds Research Collective. (2020). Learning to Become with the World: Education for Future Survival. Paper commissioned for the UNESCO Futures of Education report, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374032

Davies, B., and Gannon, S. (eds). (2006). Doing Collective Biography: Investigating the Production of Subjectivity. Open University Press

—— (2012). ‘Collective Biography and the Entangled Enlivening of Being’. International Review of Qualitative Research, 5(4), 357–76, https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2012.5.4.357

Haraway, D. (2008). When Species Meet. University of Minnesota Press.

—— (2016). Manifestly Haraway. University of Minnesota Press, https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816650477.001.0001

Haug, F.; Andresen, S.; Bünz-Elfferding, A.; Hauser, C.; Lang, U.; Laudan, M.; Lüdermann, M.; and Meir, U. (1987). Female Sexualization: A Collective Work of Memory, trans. by E. Carter. Verso

Kennedy, R. (2017). ‘Multidirectional Eco-memory in an Era of Extinction: Colonial Whaling and Indigenous Dispossession in Kim Scott’s That Deadman Dance’, in The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, ed. by U. K. Heise, J. Christensen, and M. Niemann (pp. 268–77). Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315766355

Kimmerer, R. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed editions

Kohn, E. (2013). How Forests Think. University of California Press, https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520276109.001.0001

Lewicka, M. (2013). ‘In Search of Roots: Memory as Enabler of Place Attachment’, in Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, ed. by L.C. Manzon and P. Devine-Wright. (pp. 49–60). Routledge

Malone, K. and Fullagar, S. (2022). ‘Sensorial’, in A Glossary for Doing Postqualitative, New Materialist and Critical Posthumanist Research across Disciplines, ed. by K. Murris. (pp. 116–17). Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003041153-58

Mazzei, L. A. (2014). ‘Beyond an Easy Sense: A Diffractive Analysis’. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 742–46, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530257

Mooer, K. P. and Miller, T. F. (2018). ‘Gratitude as Ceremony: A Practical Guide to Decolonisation’. Journal of Sustainability Education, 18

Plumwood V. (2009). ‘Nature in the Active Voice’. Australian Humanities Review, (46), 113–29, https://doi.org/10.22459/ahr.46.2009.10

Pretti, E. L.; Jiang, J.; Nielsen, A.; Goebel, J.; and Silova, I. (2022). ‘Memories of a Girl Between Worlds: Speculative Common Worldings. Journal of Childhood Studies, 47(1), 14–28, https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs202219957

Silova, I., Piattoeva, N., and Millei, Z. (eds). (2018). Childhood and Schooling in Post/Socialist Societies: Memories of Everyday Life. Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62791-5

Silova, I. (2020). ‘Anticipating Other Worlds, Animating Our Selves: An Invitation to Comparative Education’. ECNU Review of Education, 3(1), 138–59, https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120904246

Silova, I.; Rappleye, J.; and You, Y. (2020). ‘Beyond the Western Horizon in Educational Research: Toward a Deeper Dialogue about our Interdependent Futures’. ECNU Review of Education, 3(1), 3–19, https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120905195

Siragusa, L.; Westman, C. N.; and Moritz, S. C. (2020). ‘Shared Breath: Human and Nonhuman Copresence through Ritualized Words and Beyond’. Current Anthropology, 61(4), 471–94, https://doi.org/10.1086/710139

Stengers, I. (2012). ‘Reclaiming Animism’. E-flux Journal, (36), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/36/61245/reclaiming-animism/

Taguchi, H. L. (2012). ‘A Diffractive and Deleuzian Approach to Analysing Interview Data’. Feminist Theory, 13(3), 265–81, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700112456001

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873548

Van Dooren, T.; Kirksey, E.; and Münster, U. (2016). ‘Multispecies Studies: Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness’. Environmental Humanities, 8(1), 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527695

Warner, M. (2007). Fantastical Metamorphoses, Other Worlds: Ways of Telling the Self. Oxford University Press

Wynter, S. (1984). ‘The Ceremony Must be Found: After Humanism’. Boundary, 2, 19–70

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing

Zheng, D. (2018). ‘Study on Red Yao Wedding Ceremony under the Perspective of Communication Ceremony’ [Conference Presentation] 4th International Conference on Education and Training, Management and Humanities Science