7. Growing up in Cold-War Argentina:

Working through the (An)archives of Childhood Memories

© 2024 Inés Dussel, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.07

This chapter sets out to present some exercises on childhood memories from Cold-War Argentina. Combining written texts with drawings and pictures, it seeks to navigate the tensions between an ‘I’ of personal memories and a ‘we’ emerging in the collective-biography workshops. It invites a journey through an (an)archive of childhood memories produced in the interstitial space between memory and forgetting, not looking for healing but trying to ‘excavate a wound’. What does one remember from one’s childhood? Where or when does a childhood start and end? Do traumatic events cast their ominous shadows on every recollection of the past? Do these memories speak about the past or about the present in which they emerge? Memory seems to be a tricky lane, which morphs as one moves. The text aims to work through these memory exercises and materials to discuss how we connect with children’s memories and experiences.

It all started at a conference: a casual discussion over some German beers about the worst thing our parents had done to us when we were children. I am not sure who suggested that topic or whether my old ‘let’s-not-talk-about-this-issue’ reflex might have been there, but the warmth and the beer must have helped me to move beyond it. Talking about our childhoods turned out to be a good ice-breaker for strangers coming from post-socialist and South American countries who did not otherwise seem to have much in common except for being of a similar age and having jobs at universities. We soon realised that there were many connections among our experiences of juggling with repressive regimes and the upbringings our parents managed to perform amid those circumstances. For the record, I think I won the contest for the worst parenting experience when I told my new friends that my sister and I had been left alone when we were eight and six years old. Our parents had departed after telling us not to worry if they did not come back that night: they were going to a demonstration and might be jailed; but, at any rate, they would return the next day (a confidence that soon turned out to be a gross miscalculation).

That night of German beers, I immediately felt that this new group could be part of an imaginary community I founded with some Argentinian friends: the club of those permanently damaged by progressive parenting. We were little fighters or pioneers, having been taught autonomy and self-sufficiency since we were very young. We shared similar stories of early internationalisms and solidarity, a sense of feeling responsible for the world. We also shared an awareness of a certain gravity or solemnity in our demeanours, which, though we had learned to laugh about it, still caught us from time to time. The effects of these early marks on our adult life were not discussed there, but none of us seemed to cling onto some grievance against our parents, with whom we could now relate to as adults who had gone through quite difficult times themselves.

Sharing our memories, we could see that our childhoods were punctuated by a pressure to conform or, if not, to be ready to pay the price for the deviation. Consequently, they were also marked by several clandestine rites. Our parents had imbued us, through subtle yet sharp training, with an ability to read situations and decide what could be said where, or what could be shown to whom. True, this distancing and calculation is not exclusive to growing up in repressive regimes. Migrant children experience some of these feelings, as do children whose identities make them feel marginalised and who learn very quickly to deal with the visible and invisible borders that make them stand out. All these experiences or ‘scenes of instruction’, as Veena Das (2015, p. 61) calls them, are ways in which children learn about the politics of the world, about their place in it, about what is just or unjust, about the boundaries of the sayable and the visible in their communities, and about the role of secrets and silences.

Reconnecting and recollecting children’s memories is a way to make these learnings visible and audible, to reflect on the political ontology of childhood, and to try to inscribe these experiences in collective memory exercises. The notion of an (an)archive is, with all its confusions (Ernst 2017), appropriate for these kinds of recollections, as this new archive does not intend to organise a historical narrative in a sequence of events but rather to decentre history and to discuss the forms in which memory emerges or is called out. Its ways of operation are more related to montage and resonance than to the order of the librarian.

This project is, as the reader might have noticed, intensely personal, and this text is an exploratory exercise on how to inscribe our (my) own memories to nurture a collective (an)archive about children’s experiences. It builds on previous experiences, particularly on the writings done by children of the disappeared and of exile (Alcoba 2014; Arfuch 2018; Blejmar 2016; Pérez 2021; Robles 2013; among many others) but also on exhibits such as ‘Hijxs. Poéticas de la Memoria’ (Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno 2021), organised by the National Library in Argentina in 2021. In particular, this exhibit dealt with a multiplicity of records to produce a multimedia digital repository of voices, images, and texts related to the political collective H.I.J.O.S.1 The exhibition, which united works by photographers, writers, filmmakers, and painters, sought to pose questions that could act as gateways for new aesthetic and political memory practices and could define new territories for memories: the everyday and the banal, the street, the space between past and present.

Following their lead, this writing experiment attempts to navigate the tensions between an ‘I’ of my personal memories and a ‘we’ that speaks of the workshops of collective biography in which these texts were produced. As William E. Connolly (2022) says in his writing about his adventures as an academic from the working class, ‘the “I” can become quite a crowd’ (p. 5), full of intertextual dialogues and echoes from other people’s memories. The ‘I’ understood in this way is never an individual but a singular perspective or point of utterance. This remark is important because, when it is considered as a self-sufficient, self-contained person, the ‘I’ can obscure the many folds within which memory emerges and takes shape, becoming the support of a de-politicised and reified version of the past and of a historiography that is only concerned with the intimate sphere, without problematising and historicising it (Traverso 2020).

And yet, this text wants to experiment with an ‘I’ that presents a recollection of memories, one deeply defined by a singular history that happens to be my own. I am aware of the risks such an experiment entails but also hopeful of the new paths it can open for historical and pedagogical inquiries. I grew up in Argentina during the 1970s and 1980s, under one of the worst military dictatorships of that era—although that ranking is hard to make. Firmly aligned with the Western rhetoric and practices of the Cold War, the Argentinian Junta performed a brutal repression of leftist activists that closely followed the playbook of the counterinsurgency developed in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Important to the Cold-War context for Argentina is that US foreign policy towards Latin America was to actively support military juntas and right-wing governments that violently repressed left-wing political parties. As is well-known in the cases of Brazil, Chile, and Argentina, the US actively helped right-wing governments come to power and hold on to it through dictatorships in order to forge strong alliances against the communist world.

In Argentina, the brutal persecution of dissidents rested on a clandestine repressive network of detention centres and extermination machines that created a new figure: ‘the disappeared’ (Pérez 2022, p. 19). People thus named were neither alive nor dead; they were names split from bodies, spectres who haunt the living (Gatti 2014; Pérez 2022). Culturally, the dictatorship was conservative and traditionalist. In the name of Christianity, it banned modern mathematics because of its set theory and meetings larger than three persons. Authorities also prohibited long hair for boys and blue jeans for everybody in schools, kisses on the street, and anything that had a scent of the 1960s (Pineau et al. 2006).

My family was a target of this repression, first from the paramilitary groups that threatened leftist activists and paved the way for the military coup, and, after 1976, from the dictatorship. We went into hiding for almost two years, during which time my father got ill and died, and my uncle and his family had to flee into exile. My grandparents’ house and my own were assaulted by military troops in search of my father and my uncle. As part of our clandestine life, we had to move frequently, and my sister and I had to change schools to avoid being traced. Once we got into a relatively stable safe house, we were told to walk home from school by different routes in order to avoid being followed by the secret police. From a distance, it seems incredibly naïve and risky to trust the safety of a family to an eight-year-old girl, but that is how many families and their children lived in those days (Oberti 2015).

Not surprisingly, I repressed my memories of the repression for a long time, despite years of psychoanalytic therapy and involvement in political movements for democracy and human rights. I struggled, I still struggle, with how to talk or write about these memories—in which tone, in which format—and ask myself whether more memories are needed in the collective anarchive, and how my personal recollections relate to broader politics of memory. These have been ongoing questions for many years, much earlier than the talk about bad parenting that opens this text. While writing a secondary school textbook on human rights in 1996, I read an interview with a survivor from a concentration camp in Buenos Aires who said that he didn’t want to be defined solely by his experience in a clandestine jail; he wanted to move on, be a physicist (as my father was), be like anyone else, because otherwise the repressors would have won. I connected instantly with this feeling that one should not be defined by ‘them’. I felt that, however much we seemed to have no choice in deciding which experiences shaped us, he and I and so many others had to struggle to make room for a choice, to make room for another option in the way we define ourselves. Looking at this interview again now, it still amazes me the extent to which the language of winning or being defeated permeates so many daily actions and positionalities for those of us who were directly touched by these events and who were the targets of the brutal repression.

Indeed, in these memory exercises, my own positionality is implicated, but is this not always the case? I have not yet been able to feel comfortable about sharing these memories; there is always an annoying internal voice that prevents me from doing it: you will sound too selfish, too confessional, too victimised. Maybe what has made me take a further step here is that this chapter is part of a collective project—one that forced me to think again, to think otherwise, about memory and forgetting, about childhood and memory, and to see myself in the mirror of other childhoods, different yet at the same time connected to mine. When writing these pages, I found a quote by Maurice Blanchot (2002): ‘Whoever wants to remember himself must entrust himself to forgetfulness, to the risk that absolute forgetfulness is, and to the beautiful chance that memory then becomes’ (p. 263). Perhaps this is my beautiful chance to give a form to my memories in the company of others to whom I can entrust myself.

Childhood is a Foreign Country

What does one remember from one’s childhood? Where or when does a childhood start and end? Do traumatic events cast their ominous shadows on every recollection one might have of that past? Do these memories speak about the past or about the present in which they emerge? Memory seems to be a tricky lane, which morphs as one moves. As I walk that path, I keep in mind Benjamin’s ‘Excavation and Memory,’ a short piece from 1932, in which he sees memory ‘not [as] an instrument for exploring the past, but rather a medium’ in that quest (Benjamin 2005, p. 576). He uses an analogy of archeology: one who wants to excavate the past through memory should always ‘mark, quite precisely, the site where he gained possession of them’ and give ‘an account of the strata which first had to be broken through’ (ibid.).

Hannah Arendt, in her introduction to Benjamin’s Illuminations (1968), also refers to excavation but uses the metaphor of the pearl diver to talk about memory work. Conferring on them a materiality, she describes memories as things that sink into the depth of the sea, dissolve themselves, ‘“suffer a sea-change” and survive in new crystallised forms and shapes’ (p. 50). The diver ‘bring[s] them up into the world of the living as “thought fragments”, as something “rich and strange”’ (ibid.), thus the image of pearls.

Rereading these takes on memory, I would say that ‘thought fragments’ is a pretentious name for my memory exercises and yet, at the same time, fits with their episodic quality and the invitation they extend to think through or along them. What definitely does not feel right is the metaphor of the pearl diver. One undertaking memory work, as Pérez (2022) analyses, is more of a ghost-buster, someone who has to deal with the marks of a biopolitics that produced spectres or phantoms (such as the disappeared), that operated in the dark a clandestine repressive apparatus, and that confined many of us to secrecy, hiding, lying, masking. In this kind of search, the diver might have the impression of swimming in a viscous substance full of detritus rather than a pristine sea (but which sea is pristine?). Can pearls be found in that detritus? Are pearls the best metaphor for thinking about memories, which are more fragmentary and episodic than the complete image of a found pearl? What I would like to retain from this metaphor, however, is the possibility of finding beauty in memories forged in an era of terror, cruelty, and long-lasting trauma. The work done by H.I.J.O.S. gives me some hope that something poetic, something that carries a sense of justice and love, can emerge out of it.

As to the strata in which my memories emerge, I would say they are made up of layers and layers of politics of memory and forgetting, of scenes of justice and impunity, of melancholy and joy. In Argentina, there was a boom of memory studies and memory narratives after the dictatorship, in the 1980s and 1990s. It was, at first, mostly dominated by writing from a generation of activists and militants who had suffered jail, kidnapping, and torture (Jelín 2002), linked more or less loosely to a more general obsession with memory (Huyssen 1995) and to the age of testimony in Latin America (Beverley 1996). Memories from the next generation, their children born in the late 1960s and the 1970, emerged afterwards, in the mid-1990s. This wave was related to the work done by H.I.J.O.S., which was organised in 1994, and involved contributions from children of the disappeared as well as of victims of repression both in Argentina and abroad.

Moving from the mothers of the disappeared to their children was a generational relay, but it also brought other shifts in the politics of memory in Argentina, the effects of which have become more visible in recent years. After years of silence and shame, after years of seeing their parents demonised and repressed, these children-become-adults overturned the silence by getting together and speaking out, doing research on their disappeared parents and making their stories visible and heard. They also started to articulate their own observations of the earlier time and to talk about their own position, their own wounds, their own claims. Many of them have used a playful tone and have experimented with different genres (films, photography, theatre, novels, blogs, animated movies, video games) to produce a new take on Argentina’s traumatic past (Blejmar 2016).

Certainly, it was a mostly urban, highly educated, psychoanalysed group that actively engaged in H.I.J.O.S.; however, their quest to ‘reverse the mark of the sign’ (Pérez 2021, p. 126) is an important one for all families affected by the repression because it involved working through mourning and melancholy and being able to produce a different encounter with the past. Perhaps more importantly, their work poses several questions about identity and memory, about childhoods lost and regained (can they be regained?), and about what is achieved in the process of reconstituting one’s identity after facing the traumatic past. Memory and forgetting are not mutually exclusive opposites; there are ‘muddier gray zones of partial recognition […that are] harder to trace’ (Stoler 2022, p. 117). For Stoler, one needs to look at ‘the space in between’, that is, the ‘interstitial space [that] is shaped by what form knowledge takes, neither wholly remembered nor forgotten’ (p. 126).

Looking for this interstitial space, without fully wanting to unveil some hidden truth or to shed light on others but with the gut feeling that the journey is valuable if done collectively and pensively, I embark on my exercises of memory. Here, I consider four memories that I wrote in the third-person voice during the collective-biography workshops organised by Mnemo ZIN that are discussed at length in other chapters of this book. I put these texts together with pictures and drawings from that earlier time as a way of accounting for the tensions present in the ‘translations of the visual to verbal, from the visual act of witnessing to the stench, to the screech, to the silent and unseen and unheard’ (Stoler 2022, p. 136). My aim is to work through (a verb to which I will later return) these materials to see if something else can be grasped about children’s memories of traumatic events and particularly of my own trajectory. Mariana Eva Pérez (2021) says that ‘all hijis2 are fans of the past’ (p. 23); maybe my historiographical passions can also be included in that category.

Fig. 7.1 Photograph of Claudia, Diana, Fabiana, me, and two unrecognised friends at my place, Buenos Aires, circa 1978. From Nano Belvedere’s personal archive.

I start with a photograph sent to me a couple of years ago by Nano, a primary school classmate (Figure 7.1). I like that it is blurred and grayish: the qualities align well with the texture of my memories, which I am afraid will appear sharper and more clear-cut than they actually are as a result of translating them into writing and of my own clumsiness in that process. The photograph shows me and some girlfriends on the balcony of the apartment in which my family lived. From the light and the clothes, I deduce that it was taken in summer. We are smiling and this is an important sign: not everything in my childhood was gloomy and sad. It may have been the end of our time together at primary school, from a year in which we felt grown-up because we were going into secondary school. We were happy but also sad because the transition meant we would be parting ways.

The memory that follows is from an earlier date and is related to the drawing I made in 1975 of a colourful boat that sails on the sea (Figure 7.2)—the sea of pearls, maybe? I have written mar [sea] three times, twice on the sails and once on the ship’s hull. This repetition suggests that words needed to be inscribed and remembered.

Fig. 7.2 Inés Dussel, untitled drawing of a sailboat, 1975.

Sailing Away

She might have been eight. The flat was on the first floor in an orange-brick, unpretentious building in the corner of a busy avenue. It was a small two-bedroom apartment, but felt like paradise after several months of constantly shifting places, sometimes every two weeks. Her parents decided to go into hiding after receiving several death threats, and while they continued working and her sister and herself kept going to school, everybody was under big stress.

She had to change schools and was told to be extra careful on her way home, checking out if she was followed by the secret police (which, not too secretly, used to wander around in green Ford Falcons and donned dark sunglasses and almost mandatory moustache). She felt it was hard but she knew there was no room for complaints.

This flat was supposed to become more permanent. They had to keep the window shades three-quarters down all the time, so as not to be seen from the outside. Her family spent most of the time in the kitchen, which looked to the inside of the building. It was there where they had breakfast, maybe coffee and mate,3 dined, and listened to the radio (Radio Colonia, a Uruguayan station that supposedly had less censorship). The kitchen felt like the only cozy place in this apartment.

She decided the living room was to be her playground. This room had a tiled floor and the dark shades were scarcely interrupted by electric lights; all in all, it felt cold, but she tried to make it her own place. The play she remembers more vividly was when she put her toys in the sofa and pretended she was sailing away with all her beloved ones. She could spend hours doing this after she came back from school. She would play with the toys, particularly a pair of elephants (Babar and Celeste, from one of her favorite children’s books). She imagined that she was the captain of the boat, steering the wheel and sailing towards distant lands.

Another play she recalls is making a tent above the dining table. She is unsure of why she preferred to produce it above and not under the table. She put two or three chairs up the table, which she remembers as involving some challenge, and then covered them with sheets or blankets. She climbed on the table and brought her toys. She remembers an orange bed sheet that created a warm light inside her tent. She thinks she kept this particular construction for a couple of days, and her mom was not too happy but let it be, as they used to be in the kitchen. Her memories are of her alone, but her sister might have joined her in the tent too. It was her space, where she felt at home.

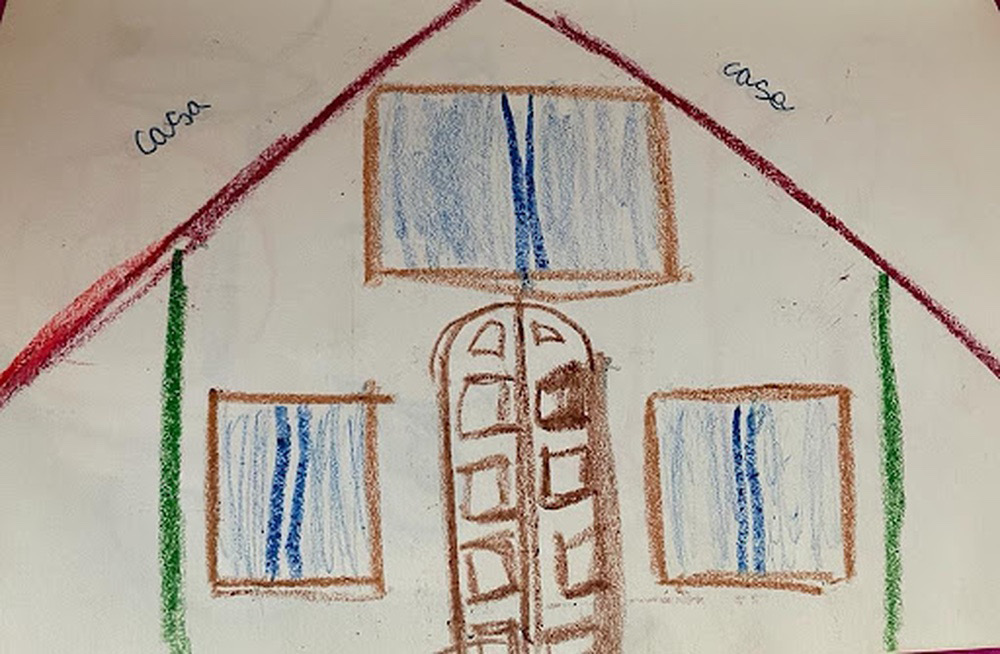

Here is another drawing of a house/home [casa in Spanish] (Figure 7.3) that I found in the same notebook as the previous drawing. The house does not resemble any of the places where we lived during those years. Its windows are adorned with what seem to be closed curtains, and the two-panel wooden door is also closed. The word ‘casa’ is repeated on both panels of the roof, as if she needed to make sure this was it.

Fig. 7.3 Inés Dussel, untitled drawing of a house with a gabled roof, 1975.

Radio Talk

As far as she can remember, her father loved three things: physics, politics, and music. He listened to classical music most of the time, and also folklore. Her mother also liked music, but she brought other tunes: protest singers like Joan Baez, Nana Mouskouri or Mercedes Sosa, and Nacha Guevara, an Argentinean cabaret singer who was quite provocative. The mother used to play one of her songs to her daughters, which made them laugh a lot: ‘Don’t you marry girls’, a funny, fast tune that advised young women to prefer good sex, short flings, and economic independence to the boring, depressing prospect of a fat and old husband (she later discovered the lyrics were from Boris Vian).

Among her father’s possessions, there was a tape recorder, a big-sized, reel-to-reel, high fidelity device. The tapes were mostly music, but from time to time he recorded some sounds at home. She remembers being interviewed by her father when she was four or five, but she recalls just his voice making questions and not their content. Was he interested in how she felt, or what she thought, or what she knew? No way to ask him now.

At some point her sister figured out how to handle the tape recorder and started playing with it. She felt lucky to be invited in. As the radio was always on, the girls were familiar with the style of the programs. They used to pretend to be radio anchors, sang songs, made silly comments, imitated the ads and the chants they heard in the street demonstrations. They could play for hours, re-recording the tapes if needed. She had lots of fun.

One particular piece delighted the family. In it the girls pretended to interview the president, the first woman to be named president after her husband, Juan Domingo Perón, passed away in July 1974. Isabelita Perón—that was her name—was a lousy president, very weak, and her term saw the growth of the paramilitary violence against popular movements, and soon after there was a military coup. Isabelita’s tenure was the time when her family went into hiding because of threats from the far right. The tape-recorder came with them to their safe house and was a good source of joy, particularly when they pretended they interviewed people. Her sister, two years older, decided who played which character each time. In the interview with Isabel Perón, the older sister took the mic (the girl remembers it as a small, quite modern device) and pretended to be the journalist; the little girl had no option but to be the lousy, weak President. Both girls had a long conversation about what the President was doing, the journalist being always on the offensive and the weak President becoming almost speechless. The girls knew the names of several ministers of the cabinet and brought them into the conversation. One question of the smart journalist still hangs in her memory: ‘President Isabelita, tell me, why are you sooo bad?’ At that point of the interview, everybody laughed. She doesn’t remember what she answered, but she was happy to participate in the plot, even if she played the villain. She felt so proud that the family enjoyed it, and that her parents knew that she was on their side.

When I read this text to my stepdaughters, they were surprised to hear that I was so politicised at a young age and that I knew the names of the cabinet ministers by heart. Such experience seemed quite unlike their own childhoods, but politics was always present when I was growing up, for better or worse, for as long as I can recall. We listened to the radio and read the newspapers every day, and we were taken to street demonstrations and to political meetings, where I remember I had no trouble falling asleep. I never questioned it: that is how it was. We were trained to be pequeñas combatientes, ‘little fighters’ (Robles 2013), learning skills that would become crucial in the years that followed.

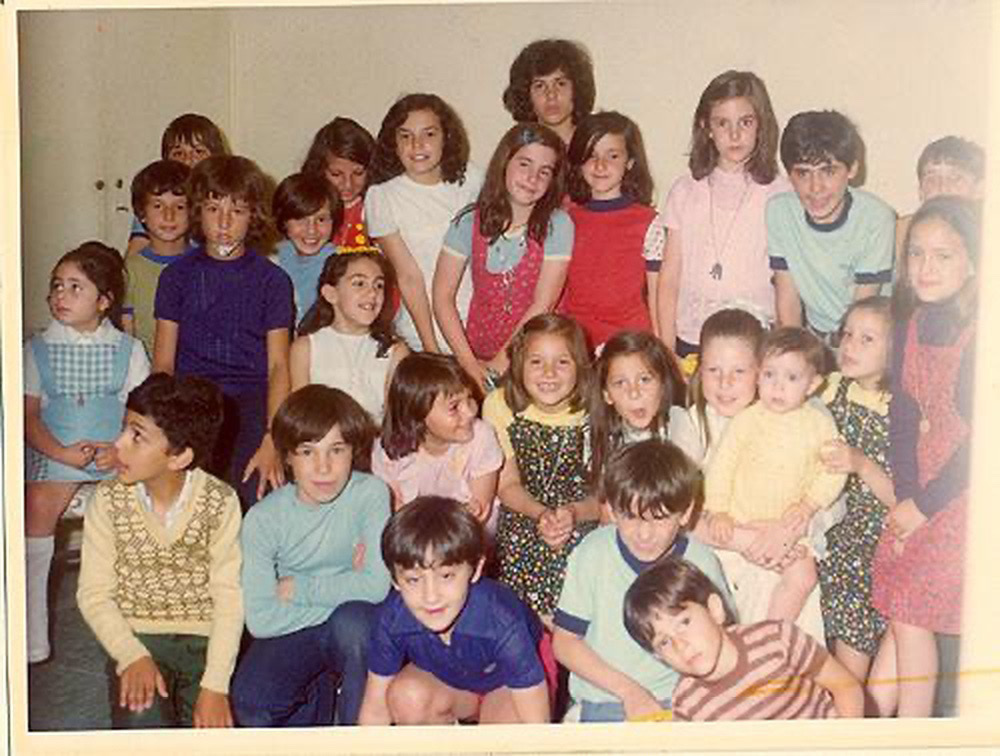

Maybe what went unnoticed by my stepdaughters is the fact that I wanted to be on and by my parents’ side, but that solidarity came at a high price. Here is a photograph from what I think might be one year later, when we were already hiding from paramilitary threats (see Figure 7.4). We had recently started to attend this school, so I am surprised to find myself in the centre of the scene [wearing a dotted red jumper pink and blue], together with my older sister [the tall person behind me in red], who came with me as we had to stick together most of the time (probably for safety reasons?). My smile seems a bit forced, and my sister is definitely not smiling.

The event was one of my classmates’ first communion, a Roman Catholic rite of passage very commonly observed by families in my generation. I am not a Catholic and was always pointed at by my teachers because of it. One of the questions we were asked at the beginning of every school year, which I assume was related to bureaucratic form-filling, was about our religion. Throughout primary school, I was the only person in my age group to declare herself an atheist—an immediate marker to the school that something was very wrong with my family. Yet, maybe for that very reason, I was perceived as exotic by my classmates. I remember that they came to ask me ‘how children were made’, assuming that my modern, hippy-looking, fan-of-Boris Vian mother would talk about such issues with me. They were right: she did. ‘Don’t you marry, girls, don’t you marry. Have sex and have fun.’

Fig. 7.4 Photograph of a Catholic friend’s celebration of communion, Buenos Aires, 1975. Author’s family archive.

Compañeros

She was in her 6th grade in a primary school. They had brought a TV on the last stages of her father’s cancer, which left him deaf and extremely weak. Her father died in June 1976 but the TV stayed with them, and she spent most afternoons watching soap operas. She even watched adult soap operas with serious drama that played at night prime time; her classmates, whose parents were much stricter, envied her freedom to do as she wished.

At that time, she spent a lot of time writing short stories that imitated what she saw on TV. She remembers one particular story about a murder in a hotel, which she signed with the name of the male writer of a soap opera she followed. She liked to give sophisticated names to her characters, with less common first names and patrician surnames. She was not particularly proud of her stories; she knew something was not quite right in them, but she liked to try out new words and imagining farfetched plots.

It was May, and at school it was time to celebrate the 1810 revolution that led to independence from Spanish rule, as was done every year. She decided she would write a theater piece for that date, and that she would give it to her teacher to see if it could be played as part of the school’s civic ceremony. She had a brief and unusual moment of total confidence. She sat down and wrote a four-page text in which she portrayed the actions of the leaders of independence. She imagined clandestine meetings in the Jabonería de Vieytes—the place where ‘the patriots’ supposedly met—to conspire against the Spanish oppressors; she narrated what happened in popular assemblies in which the revolutionary leaders would address other people as ‘compañeros’ (comrades) and speak about revolution and making this a better world. The piece ended with the masses marching towards victory in the Plaza de Mayo, Buenos Aires’ central square. She was beaming with happiness.

Her mom came from work, and the girl must have sensed that something was not quite right because she decided to show it before handing it to the teacher. Her mother smiled at the beginning, but her face soon turned serious and worried. What would her teacher think if she spoke about revolution? Moreover, all the joy about people marching in the Plaza and the compañeros: how would it sound in those dark days? The mother did not need to give an order. The girl folded the pages, took them to her room, and hid them in a drawer.

Self-discipline was essential for clandestine lives. In fact, several militants were caught by the military when they broke the code by visiting relatives or by sharing too much information with the wrong people. Historian Alejandra Oberti (2015) has studied the affective life of female militants who joined the guerrilla movements. She found that these movements had published behavioural codes and rules, and that there were cases in which militants were put on trial and punished because they had broken them with queries about maintaining their family and sexual life while in hiding.

One such code for militants, issued in 1972, specifies that ‘the children of the revolutionary’ should share all aspects of their parents’ lives, including running their risks. ‘Special protection to children should be sought as long as it doesn’t get in conflict with the superior interests of revolution’ (Ortolani, cited in Oberti 2015, p. 41). An image of a Vietnamese mother breast-feeding her baby with a rifle by her side is praised as beautiful and as ‘a symbol of this new revolutionary attitude towards our offspring’ (ibid.).

It is not easy for me to read these rules, to picture myself in these images. Yet, it helps me to understand the seemingly unquestionable order of priorities with which I can connect. Mariana Eva Pérez, whose parents were kidnapped and disappeared when she was fifteen months old, calls such offspring ‘princesas montoneras’ [revolutionary princesses] and writes a poem that plays with a well-known children’s rhyme, Arroz con Leche:

these girls

knew how to sew and embroider

but the part of going out to play, they owe you that

because they were to be responsible for everything too soon

for what they remembered and for what they had forgotten

O cursed spite!

Princesses from the wrong tale

(Pérez 2021, pp. 21–2, my translation, emphasis in the original (a quote from Hamlet)).

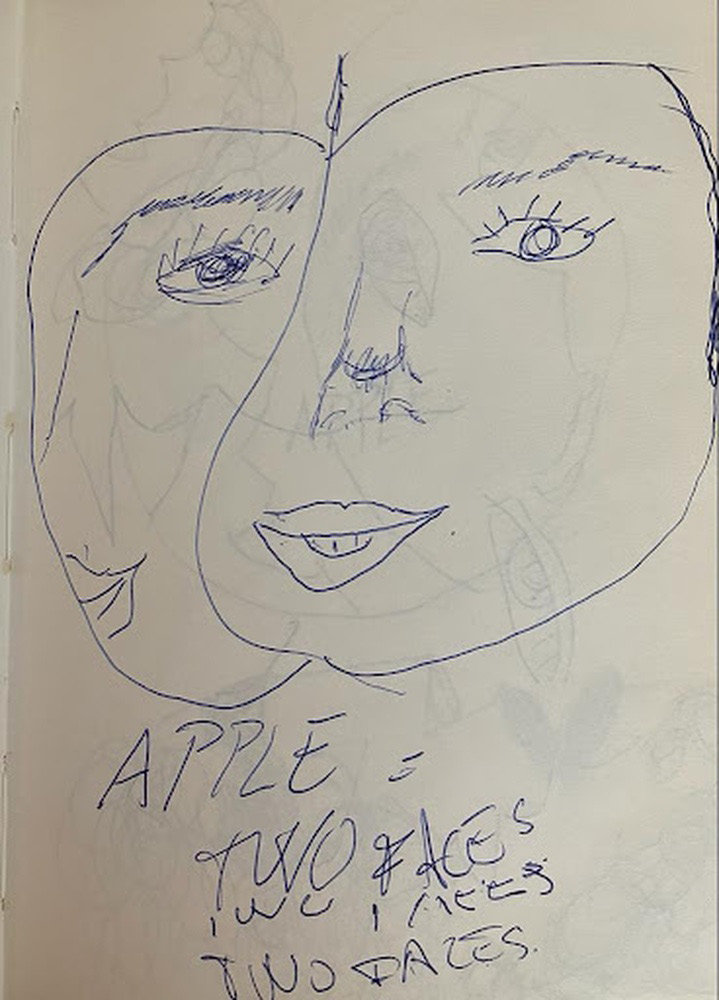

I found a drawing from those years in which I sketched a two-faced apple (Figure 7.5).

Fig. 7.5 Inés Dussel, Apple = Two Faces, drawing, 1977.

I always struggled with noses in my drawings, and this doodle shows it. The image, however, tells of the duplicity I was forced to endure, of the double life I felt I was living. One eye seems shy and alert; the other one, the one that seems to hide behind the first one, is more vivid and bright, and it is accompanied by what seems to be a smile. I am surprised that the writing is in English, a language that I did not feel comfortable with at that time. Maybe language was also a way of hiding who I was. The line ‘two faces’ is repeated three times, the second one cut in half, the third one blurred. It seems that I tended to repeat words; maybe the fear of forgetting or getting lost was always there, or maybe I was not able to work through my wounds, a topic to which I return in the final section of this chapter. Compared to ‘mar’ and ‘casa’, the verbal repetitions in this drawing introduce some changes: I must have felt the need to write about the duplicity and at the same time to deny it, to erase it.

More on Compañeros

It was the year of the military coup; she knows it because she remembers Miss (Señorita) Susana was her 5th grade teacher, and that was 1976. ‘La señorita Susana’ was nice, warm, and seemed to know her way around the class; she must have been in her 40s or 50s, as she had grown-up children. Her husband was involved in a football club that the girl liked, and that made the girl feel close to her teacher.

The class was usually quite participatory. Miss Susana asked children about their opinion and made them write a lot, which the girl liked. The atmosphere was relaxed, and children wandered around the space freely and noisily.

The girl sat in the first rows of the classroom, perhaps because she wanted to be a good student, but it also might have been related to her shortsightedness, as she later discovered. One day, she heard two boys fighting behind her back. One of them was the son of a military officer, and the other boy’s father was a journalist who worked at a popular newspaper. The boys were shouting at each other, but nobody seemed to care. At one point, the son of the officer cried: ‘Your father is a Peronist!’, referring to the political party that had been overthrown by the military coup and that was proscribed at that time. The son of the journalist replied, quite annoyed: ‘No, my father is not a Peronist, he is a Montonero!’. The class went silent. Montoneros was a group from the Peronist left which had moved into a guerrilla group (‘armed struggle’, it was called those days) and was considered a terrorist group by the military (‘los subversivos’). The girl knew that because her father had belonged to that group, and for a moment she stopped breathing. She realised that it had caused a similar effect on everyone: the class was unusually silent and they were all frozen.

Miss Susana also stopped doing whatever she was doing, but reacted quickly and talked to the whole class: ‘Hey, all of you, this boy is talking nonsense. Don’t you worry, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Please go on with your work.’ The son of the officer insisted: ‘He said his father is Montonero!’ And the teacher silenced him at once: ‘He is a boy. He doesn’t know a thing. Stop it.’ The girl looked down to her notebook. It was not easy to continue working, but she tried. She loved Miss Susana even more than before.

The next year, the son of the journalist did not come back to school. The girl feared the worst. Thirty years later she met him at a school reunion and asked him about his father: he had survived the dictatorship.

In Argentina, teachers are called ‘señorita’ or ‘miss’, no matter how long they have been married and how many children they have. Their sexuality and personal lives are forever trapped in a figure that is always young, single, and chaste (Fernández 1998). But Miss Susana inhabited that figure in her own way. I think about her gesture, her reassurance that we were just children and not little fighters (as some of our parents were convinced), and I am still moved today. In that context, being ‘just’ boys and girls produced a different space that protected us.

Those minor gestures of solidarity and care were not unusual, and maybe it is in them that flashes of hope can be found. Around 2006, I shared a panel with one of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo,4 who worked as a teacher when her pregnant daughter was kidnapped. She told us that, when she got news of the abduction, she was at the school and could barely stand still. The school principal, who was married to a member of the police, told her to come to the schoolyard and raise the national flag, as a sort of act of humiliation and a sign of defeat to the ‘national’ forces. The soon-to-be Grandmother of Plaza de Mayo felt as if the floor beneath her was opening. A colleague of hers stood up and told the principal that she would take her place. It took great courage to confront the school principal and, by proxy, the police, and to show solidarity; most people looked down and pretended not to see or hear. Thirty years later, the Grandmother could still remember the scene.

Here is Señorita Susana with the whole class (Figure 7.6). Again, I find myself centre-stage in the photograph, and I continue to be surprised by that, since I remember myself hiding and trying to go unnoticed. Memory is indeed a tricky and confusing lane. Miss Susana is in the upper-right corner.

Fig. 7.6 Photograph of the author’s fifth-grade class in Primary school, Buenos Aires, 1976. Author’s family archive.

Working Through Memories

I feel a little dizzy writing these memories, maybe because I have this old reflex of not exposing myself, not showing or saying much about those years. But now it is done. I want to think that my journey through this interstitial space between memory and forgetting is not looking for healing but, maybe, excavating a wound (Hartman 2007), with the hope that, in the end, there will be an ‘elsewhere’ where my generation can stop being ‘the orphaned princesses / of revolution and defeat / in the eternal exile of childhood’ (Pérez 2021, p. 22).

To be honest, I do not feel eternally exiled into childhood, and my history differs from those of several H.I.J.O.S. whose parents disappeared when they were toddlers. I was lucky that I could grow up with my mom and, some years later, also with a stepdad. Instead of permanent exile, I think of my childhood as having been cut short by traumatic events that required me to act as an adult from very early on. But what the Reconnect/Recollect project has implied all along is that childhood is not a fixed category; we cannot assume that childhood is an unburdened, free-of-rules time in which children wander happily. Childhood is so much more than that, as this book attests: it is so complex and multi-layered, so much part of a common human experience and, yet, so singular. As said before, children are not passive receptors of the world but inhabit it and take part in it with their words, views, and actions. In that respect, my childhood was not different from, and in a way was even more privileged than, many other childhoods that take place in diverse contexts. Making sense of the world, deciphering it, placing oneself in it, blending in or standing out, showing or not showing, are dilemmas that each child has to walk through, to work through.

A final comment on this verb I repeated throughout these pages. I borrow it from psychoanalysis, where it is used to refer to the elaboration of a trauma. In a short piece called ‘Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through’, Freud (1950) proposed that the analyst should help the patient to process and interpret his or her memories in a way that connects, reorganises, and rearticulates the remembrance into the ego or self. ‘Working through’ means giving time to converse about memories and also organising an intermediate region, maybe something similar to the interstitial space between memory and forgetting to which Stoler (2022) refers.

Memories demand work. They are not immediate pathways to the past and will never be. If there are any pearls, they will have to be dug and sought with passion and interest, with time and patience. Memories are not mirrors in which we can recognise ourselves, or mental places where we are able to grasp the past ‘as it really happened’, as historians following the Rankean tradition would assume if they considered memories a relevant source. Recollecting memories does not have to provide the stage for an unbounded ego that replaces the transcendental modern collective subject with an individual one. Instead, the process can be a way to account for the ways in which our histories, while deeply personal, are entangled with other human and non-human beings, with tape recorders, writing pads, photos, spaces, and voices.

Moreover, as the work done by some H.I.J.O.S. in Argentina shows, if memories are worked-through, they may open up a different relationship with the past, perhaps making ‘room for other realities, other narratives’ and even ‘for subscribing to other regimes of truth’ (Stoler 2022, p. 136). The past is not out there to be recognised as a single causal line that determines our present. Instead, the past might be more productively approached as ‘a contemporaneity […] vital and potent in this present’ (ibid.). In that respect, childhood memories, even if they are blurred images or distorted mirrors, can be very helpful in understanding the vitality and potency of that past among us. If worked through, if taken pensively, if connected with other fragments and inscribed in different series, these memories can make some room for an ‘elsewhere’ that allows us, collectively, to elaborate our traumatic pasts.

Without Whom…

I borrowed the title of this section from a book by Ann Laura Stoler (2022), whose work on archives and racialised pasts has accompanied me throughout the years. ‘Without whom’ seems so much more appropriate than ‘acknowledgements’ to allow me to recognise and give back to the intellectual and affective networks that make memory exercises possible. This experiment would not have been possible without Zsuzsa, who took me by the hand and made me laugh and think, and stayed with me when tears came and also when they went away, and without the Mnemo ZIN collective, whose creative energy took me on the ride. Without Leonor Arfuch, my dear friend who recently passed away, who read a preliminary version of some of these texts and urged me to write more and work through my memories: this text owes more to her than I can verbally account for, and for many reasons I wish she was still here to read it and critique it. Without the H.I.J.O.S. and without all those who try to deal with traumatic childhoods through writing and art, particularly my friend Julia but also other ‘hijis’ (Pérez 2021) whom I have scarcely or never met: Mariana Eva, Raquel, Laura, Verónica, Albertina, María, Lucila, Félix, Julián, María Inés, and so many others. Without Verónica, my sister, who endured me through childhood and cared for me even when she was as fearful and scared as I was. Without my mom and stepdad, who were there to lift me up and help me go places. Without Pato and Ale, my friends who listened, asked questions, criticised, and listened again. Without the Seminaria Fuera de Lugar at my department, where we also started writing and thinking about academic work and life through collective exercises of memory. Without Norma, another experienced listener and guide in the workings on memory and the self. Without Antonio, whose love, joy, and optimism gave me the platform, the earth, the sea in which and from which I could dare to excavate. Without Ana, Mariana, and Amalia, who also make part of that earth, my world, and who taught me about childhoods in more ways than I could have ever imagined. To all of them, gracias totales.

References

Alcoba, L. (2014). La Casa de los Conejos. Edhasa

Arendt, H. (1968). ‘Introduction’, in W. Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections Schocken Books, pp. 1–51

Arfuch, L. (2018). La Vida Narrada. Memoria, Subjetividad y Política. EDUVIM, https://doi.org/10.7774/cevr.2016.5.1.19

Benjamin, W. (2005). ‘Excavation and Memory’, in Selected Writings, Vol. 2: 1930–1934, ed. and trans. by M. Jennings, H. Eiland, and G. Smith. Harvard University Press, p. 576

Beverley, J. (1996). ‘The Real Thing’, in The Real Thing: Testimonial Discourse and Latin America, ed. by G. M. Gugelberg. Duke University Press, pp. 266–86

Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno (2021). Hijxs. Poéticas de la Memoria. Biblioteca Nacional

Blanchot, M. (2002). The Book to Come, trans. by C. Mandell. Stanford University Press http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=1459

Blejmar, J. (2016). Playful Memories: The Autofictional Turn in Post-Dictatorship Argentina. Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40964-1

Connolly, W. E. (2022). Resounding Events. Adventures of an Academic from the Working Class. Fordham University Press, https://doi.org/10.5422/fordham/9781531500221.001.0001

Coria, J. (2006). ‘El Sentido de la Historia’. El Monitor de la Educación Común, 6, Quinta Época, 30–8

Das, V. (2015). Affliction: Health, Disease, Poverty. Fordham University Press, https://doi.org/10.5422/fordham/9780823261802.001.0001

Ernst, W. (2017, May 17). ‘Good-Bye “Archive”: Towards a Media Theory of Dynamic Storage’. [Lecture at Lusitanean University Lisbon]. Museum of Contemporary Art, https://www.musikundmedien.hu-berlin.de/de/medienwissenschaft/medientheorien/ernst-in-english/pdfs/archive-good-bye.pdf

Fernández, A. (1998). ‘La Sexualidad Atrapada de la Señorita Maestra: Una Lectura Psicopedagógica del ser Mujer, la Corporeidad y el Aprendizaje’. Ediciones Nueva Visión.

Freud, S. (1950). ‘Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Hogarth Press, vol. 12, pp. 147–57

Gatti, G. (2014). Surviving Forced Disappearance in Argentina and Uruguay: Identity and Meaning. Palgrave Macmillan

Hartman, S. (2007). Lose Your Mother. A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route. Macmillan

Huyssen, A. (1995). Twilight Memories. Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203610213

Jelín, E. (2002). Los Trabajos de la Memoria. Siglo XXI de Argentina Editores

Oberti, A. (2015). Las Revolucionarias: Militancia, Vida Cotidiana y Afectividad en los Setenta. Edhasa

Pérez, M. E. (2021). Diario de una Princesa Montonera: 110% Verdad. Planeta

—— (2022). Fantasmas en Escena: Teatro y Desaparición. Paidós

Pineau, P., Mariño, M., Arata, N., and Mercado, B. (2006). El Principio del Fin: Políticas y Memorias de la Educación en la Última Dictadura Militar (1976–1983). Ediciones Colihue

Robles, R. (2013). Pequeños Combatientes. Alfaguara

Stoler, A. L. (2022). Interior Frontiers: Essays on the Entrails of Inequality. Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190076375.001.0001

Traverso, E. (2020). Passés Singuliers: Le ‘Je’ dans l´écriture de l’Histoire. Lux Éditeurs

1 ‘H.I.J.O.S.’ literally means offspring, or someone’s children, in Spanish, and it is an acronym for Hijos por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio [Children for Identity and Justice and against Forgetting and Silence]. This association was founded in 1994 by children of the disappeared, jailed, or sent into exile by the dictatorship. At that time, H.I.J.O.S. organised successful demonstrations and artistic gatherings in front of the homes of the perpetrators. It put up signs along the road reading ‘Beware, a committer of genocide lives nearby’ and sprayed on the walls of their houses graffiti—called ‘escraches’—thereby outing the offenders. The emergence of this collective on the public scene renewed the participation of young people in human-rights demonstrations in the late 1990s, after years of declining numbers. With the introduction of laws against amnesty and impunity and the reopening of the trials against the perpetrators, its role changed (for a chronicle, see Pérez 2021). Remarkably, the collective includes a significant group of artists: photographers, writers, playwrights, filmmakers, and painters.

2 Pérez refers to H.I.J.O.S., the collective of which she was a part, as hijis—a pun that denotes a deconstructive play with language (Arfuch, 2018).

3 Mate (yerba mate) is an Argentinean drink that one sips with a straw.

4 The ‘Abuelas’ [Grandmothers] is a civil association that was founded in 1977 by relatives of disappeared people in order to search for kidnapped children who were given up for adoption and had their identities stolen during the dictatorship. So far, the group has found 137 children, but hundreds more are still missing. See: https://abuelas.org.ar/idiomas/english/history.htm