8. The Secrets:

Connections Across Divides

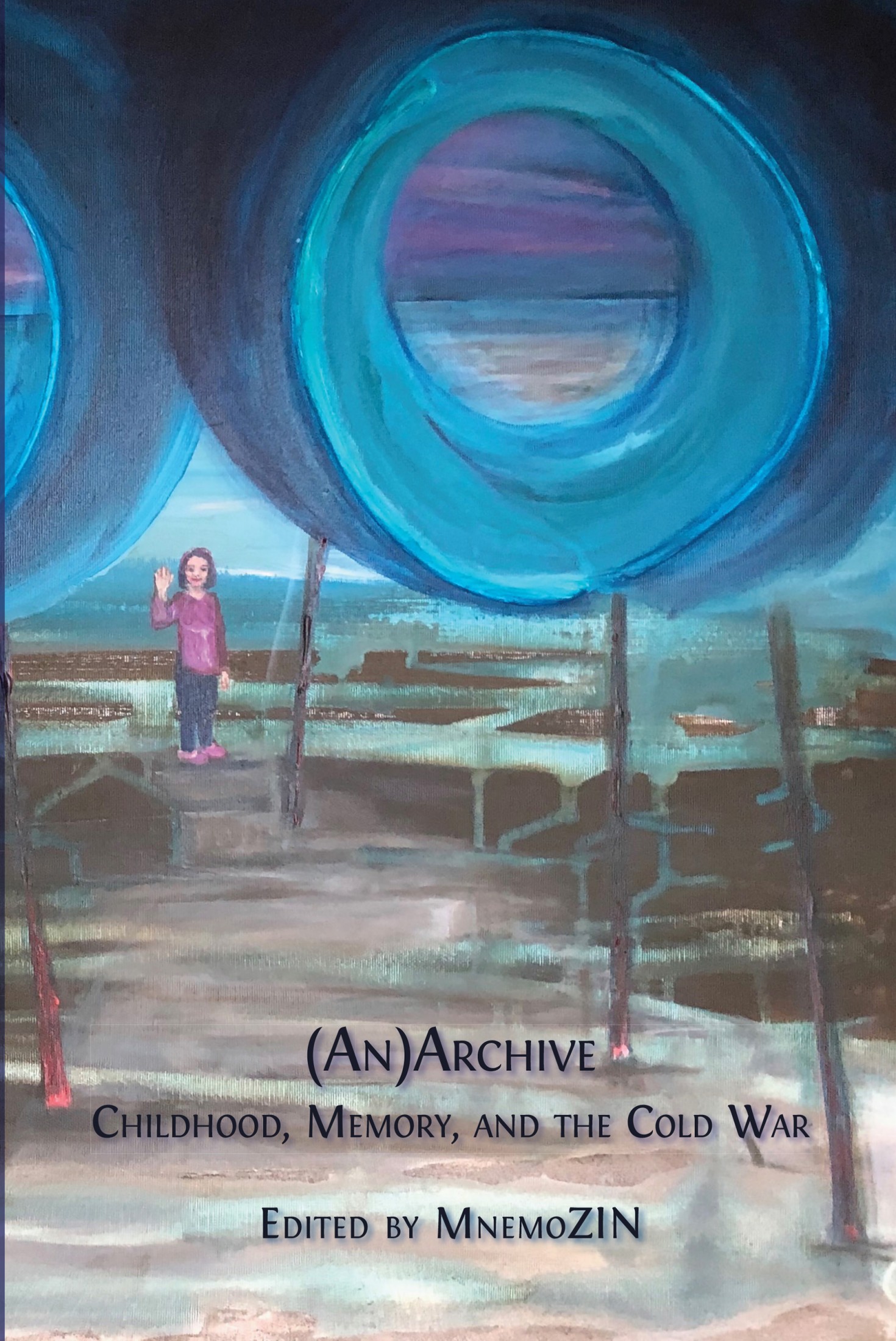

© 2024 Irena Kašparová et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.08

Childhood memories are filled with secrets. Secrets have a potency to connect, to cross, or to create a divide between people, generations, places, ideologies, borders, and geopolitical relations. They are agents of movement and action, despite the fact that they may be locked away in a person’s mind, heart, or body. A slight hint—a sensual intake, a word, or a shared memory may trigger the re/emergence of a secret. The ethnodrama presented in this chapter is created from memories shared during a collective memory workshop in Berlin in 2019 and is embellished with fictional characters, additions, and dramatisation to allow the reader to engage, make sense, or affectively connect to childhood secrets of the Cold War.

Secrets! We all accumulate them throughout our lives. Some of them last only for a short while, bursting into the open rather quickly. Others remain buried, permeating our lives in their embodied entrails and contributing to our becoming. Private and intimate, they must be watched over and protected. No secrets are, however, either forgotten or inactive. They spice up the reservoir of our feelings and can act spontaneously when we least expect them to. In this chapter, we aim to capture the life of childhood secrets during the Cold War, especially as these connect, cross, or create divides between people, generations, places, ideologies, borders, and geopolitical relations. We do this by dramatising and adding fictional elements to our childhood memories in an ethnodrama.

We, the authors of this chapter, first met in September 2019 in Berlin, as part of the collective memory workshop of the Reconnect/Recollect project. During the workshop, we shared our childhood memories from the Cold-War period. These memories recounted events that spanned the former state-socialist countries in East-Central Europe. To our surprise, secrets appeared in many memories, including accounts of very private bodily experiences and, at perhaps the opposite extreme, of participation in political activism. These memories, embedded in secrets, not only tell about singular, individual, or culturally specific experiences; they resonated across the participants´ recollections, connecting their bodily sensations and evoking different facets of their lived experiences, including the emotions and tensions that surrounded them.

We were fascinated by the power of secrets to connect people across time and space. This chapter is an attempt to share our fascination with the reader. We want to draw readers into the bridging and bonding potency of secrets and hope that, by sharing childhood secrets in a dramatic form, we will also trigger the emergence of readers’ childhood memories. First, however, we present a short exploration of public-private secret dynamisms from a theoretical perspective. For this, we brought together reflections from the fields of sociology, anthropology, history, and childhood studies. This theoretical framing is followed by the introduction of childhood memories, including the way we gathered and analysed them to create an ethnodrama, which constitutes the final part of our contribution. The plot of the script is a fiction, comprising childhood memories of secrets and imaginative elements. The combination aims to foreground the mechanics of secrets and the tensions these create.

Theoretical Anchor

Secret is a multisensory phenomenon, expressed across a plurality of domains, such as everyday talk, folklore, semiotic spaces, journalism, humour, and many others (Jones 2014). Charged with social tension, a secret creates, mediates, and controls social relations and colours their nature by modulating the ratio of knowledge to ignorance (Simmel 1906). A palpable aura of risk emerges from secrets. If a secret is not private, those who know it may understand its meanings differently—a situation that leads to tensions. Revealing a secret can also have consequences. As such, it becomes an active agent. The secret shapes understandings and acts without one’s control; it may even act without one’s knowledge or without knowledge of what others might do upon learning the secret.

A secret itself can be considered as an affair that occurs in a liminal or bordered space of existence. It happens when boundaries or norms are crossed, reality is split open, and emotions are stricken. Admitting the existence of any such fissure could lead to undesired or feared changes (for example, a mother does not confront the children who stole flowers from people’s gardens for her). To prevent a change taking place and to hold onto the foregone reality, a secret is born. The secret functions as a hanging bridge, uncertain and shaky, operating as a connection or an uncrossable division. With a secret’s coming into being, the former consistency of the self is interrupted as life starts to deviate from its original course.

Secrets are also paradoxical, in at least two ways. The first paradox resides in the individual or collective nature of a secret. A secret’s existence, while often concealed from all but one individual, emerges and is sustained through relations. One cannot keep a secret from him or herself but only from others. Thus, every secret, even when held by a single individual, is nevertheless relational because it exists only in relation to others from whom the secret is kept.

The second paradox intertwines two notions: that secrets are constitutive of one’s life and, at the same time, that one’s life (in modern societies) is transparent or holds no secrets. First, a secret can be a decisive and constitutive moment in one’s life. It shapes the emerging individual while, at the same time, shaping society and its norms, hierarchies, categories, relations, and materialities. As such, a secret has creative and productive agency over the trajectory of every human life (Birchall 2016). Each child, for instance, needs a secret hiding place, a ‘space of shelter and safety, where one can withdraw from the outside world’ (Van Manen and Levering 1996, p. 23). The secret place can be a space of contemplation, ‘an asylum in which the child can withdraw to experiment with a growing sense of self-awareness affecting growth of the inner, spiritual life’ (ibid.). In our memories, listening in on radio channels from Western European countries, such as Radio Free Europe; playing with the body of a deceased person before the funeral in a Church; entering someone else’s room and playing with others’ possession; or smoking or drinking in secret are examples of such personal secrets.

Second, as Simmel (1906) was already arguing over a century ago, Europe has a moral distaste for secrecy. With the collapse of the feudal world order and the emergence of socialism and early capitalism, transparency became a virtue. The absence of secrets was associated with religious and/or intellectual rebirth and purity that few could fail to praise. As members of societies espousing this moral code, children are taught about the undesirability of secrets. Yet, they are also taught that some secrets need to be kept. These can refer to the private life of a family or community or be public secrets. Sometimes secrets become embedded in the culture and show themselves in language conventions. For instance, the longstanding notion that some secrets carry sinister connotations is enshrined in proverbs such as the Czech ´Co je šeptem, to je čertem´ [what is whispered becomes the Devil himself] (Gable 1997). In such cases, shared norms regulate a secret’s open existence, meaning that, while a secret may be known by a group of people, it may not be pronounced publicly. A veil is drawn over the secret. If whispering to preserve a secret is publicly detected, whispering is also publicly condemned as sinister behaviour that prevents transparency and supports conspiracy. The social norm that publicly condemns secrets may also be expressed as ridicule through jokes and humour, as folklore, or in games (Jones 2014). Its expression is learned by children from an early age together with its norms. Such secrets in our childhood memories emerged as we were made to smuggle money and goods across the East-West borders; as we kept Western goods hidden (Kent cigarettes, Bravo or French fashion magazines, French scarves), hid a disagreement with the socialist ideology; or we knew that only the façade of buildings was refurbished leaving the building otherwise in ruins.

Our childhood memories recount personal and public secrets, including even those secrets that must be kept forever as they would mean incarceration for those involved. Personal secrets were known by friends of family; the latter were sometimes not really secrets since they were known by many people but were, nevertheless, kept as secrets. These public secrets were often related to norms accepted by society such as, say, stealing from socialist cooperatives or cheating in exams. If cheating happened in secret but with the knowledge of the teacher who pretended not to notice, for example, the facade of the norm was maintained despite being (unofficially) broken. As children, we had to come to terms with this kind of duality: not having personal secrets yet knowing how to uphold public secrets. This type often involved some kind of disrespect for the regime, which led to corruption as a form of resistance, such as when employees stole raw materials or end-products from state-run factories. During the communist Czechoslovak times, there was even a popular saying ´Whoever is not stealing from the state is stealing from their family´, which appeared in public discourse in the same way as popular wisdom and proverbs. A public secret involves the risk of public acknowledgement and consequential punishment for breaking the norm (Taussig 1999). Consequently, a public secret occupies the squeezed middle in political arenas:

On one side it is challenged by calls for transparency and openness; on the other it is trumped, in moral terms, by privacy […]. Citizens are commonly said to have a ‘right to privacy’ but not exactly a ‘right to secrecy’. (Birchall 2011, p. 8)

If private lives become inspected for secrets, that is where a totalitarian space begins (Derrida and Ferraris 2001). Our childhood memories of socialism demonstrate similar paradoxes.

Under socialist reality, transparency was associated with the possibility of all citizens taking part in running the country economically, politically, and ideologically. Transparency was theoretically assured by concentrating power in the hands of people, who were encouraged and rewarded for watching over each other. Snitching, once merely an expedient obtrusion, became a necessary group-protective activity. As such, it became a symbol of regime-collaboration and was despised by those who opposed its repression (Van Manen and Levering 1996). Despite this focus on exposure, secrecy was vital in socialist regimes (Fitzpatrick 1999). The obsession with secrecy, which had its origins in communist parties’ experiences as illegal and persecuted movements before they took power, invaded government and party practice. It led to the development of a culture of secrecy and of political organisations characterised by what they did not share (Verdery 2014). This also had an impact on people’s everyday lives. In a society where people could be arrested for loose tongues (their own or those of people around them), where ‘the walls have ears’, families turned inwards. They kept, sometimes even from their own children, information, opinions, beliefs, values, or modes of existence that clashed with public norms. From a very early age, children learned the importance of secrets for the survival of their families, and secrecy became an intrinsic part of their lives (Figes 2007).

Debates about transparency and secrecy are ongoing in the social sciences. This chapter aims to contribute to such discourse by recognising the plurality of and paradoxes inflicted by the presence of secrets. It explores secrets in childhood memories as social agents from a relational perspective, while paying attention to the time-spaces and socio-material entanglements that enabled secrets to bond people together across socialist borders.

Creating an Ethnodrama

We have gathered all memories about secrets that were produced in the collective-biography workshops (Davies and Gannon 2006) and included in the archive on the project website. Our final selection included twenty-two memories that portray personal, group, or public secrets. We each read them carefully, over and over again, afterwards making inferences about the memory and responding to the following questions: What is the nature of the secret in the memory? How does it create / draw on relations? How does it operate in the memory? What does the memory reveal about a secret? After several collective discussions about our responses to these questions, thinking through the variety of Cold-War contexts across the region these memories recounted, and reading across multidisciplinary literature in anthropology, education, history, and childhood studies, we arrived at the conclusion that we would like to highlight the ways in which secrets relate to, create, maintain, and disrupt different divisions. We understand division in multiple ways, including age, gender, generation, family, place, Cold War, borders, ideologies. We also wished to bring into our analysis the emotional and affective aspects of secrets, as we felt that, even from the temporal distance of the present, looking back on the secrets still produced visceral reactions within our bodies.

We took childhood memories of the Cold War from the narratives of adults in which they make sense of remembered fragments, feelings, sensations, and dialogues but do not recreate the events that took place. In other words, memories are not historical truths, even though they refer to historical events and conditions. Memory stories mix imagination with the above-listed narrative elements (Keightley 2010), and they are written by adults with the intention of intimating a child’s way of being in the world (Millei et al. 2019). In some ways, memories and secrets operate similarly. Both lie dormant, helping to orient the person in everyday life without taking full shape and intensity, until there is an intention or necessity to revive them. Then, they move the memory- or secret-teller and the listener with an affective force, creating relations, emotions, visceral reactions, and bringing to the fore other memories.

How, we wondered, could we capture in our writing the moment of the emergence of affect in the most expressive way? We wanted to show readers the secrets’ dynamism and real-world effects with all their consequences, including the sparking of emotions, curiosity, doubt, fascination, and anxiety. To fulfil these intentions, we turned to ethnodrama—a methodology that fuses research of participants’ experiences, including the emotive elements of the stories (data), with the artistic techniques of theatre (Saldaña 2011). Ethnodrama is a mode of exploration that recounts the insights gained through analysis in a written script for a dramatic play that can be performed by actors. Like the memory stories, an ethnodrama is not a direct representation of the world (Richardson 1997). Nonetheless, its techniques allow for the creation of engagements with an audience that are similar to how a secret operates.

The plot of our ethnodrama, entitled Secrets, is based on several memories. Fictional elements, borrowed from other memories in the archive, provided the missing glue that allowed us to build our characters and to develop tensions. We fused the narrators of these different memories into five characters, switching their genders, and giving them names typically used across East-Central Europe. While writing their storyline, we paid special attention to how secrets facilitate both conflict and reconciliation. As the ethnodrama incorporates analysis of the memories, we do not offer further analytical remarks or discussion to conclude the chapter. We wish, instead, to leave the readers to be affected by the story as though by a secret—with intrigue, tension, and emotions.

Secrets

Characters

HANNA: a thirteen-year-old girl from the East (socialist country) who is cheeky, street smart, and brainy. She is the cousin of JÖRG.

MARIA: her friend, a thirteen-year-old girl from the East who is timid at home but wild in public and has her own views.

JÖRG: a fourteen-year-old boy from the West (Western European non-socialist country). HANNA’s cousin, he feels superior to her because he thinks he knows the world better than she does. He dresses well and loves to play Nintendo.

MOTHER: the mother of HANNA and aunt of JÖRG. An exhausted, busy person, she trusts her daughter but is an authority and demands respect. She is from the East.

AUNT: the mother of JÖRG and aunt of HANNA. She is from the West.

RADIO HOST: male voice.

Act 1.

A flat in an apartment block, somewhere in the East: Radio Free Europe

In the back of the stage positioned in the middle, a white sheet hangs dividing the two parts of the stage diagonally. Posters from Bravo Magazine of Sinéad O’Connor and Enya are projected upon it, as if pinned above the bed. Evening. O’Connor’s song ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ is playing. On the left side of the stage, the light goes on, revealing cupboards across from the bed.

HANNA and MARIA (sing in chorus as they search in the cupboard for cigarettes). Noooothing compaaaaaares…. PU-IUUUUU.

MARIA. Where does your mother keep them?

MARIA (finding a pack). They will notice we took one, look it is not even open!

HANNA. Do you think they will be mad? I am so scared, we shouldn’t do this.

MARIA (lighting the cigarette). They said these are better than the Carpati. But they taste horrible!

HANNA. Grandpa smokes Carpati. He loves Kent, he says it is better quality. You know, from the West.

MARIA. I was so embarrassed last week when my mom slid it into the doctor’s pocket. I would never be able to do that

(Girls put the cigarettes under the mattress and continue smoking.’Take Five’ by Dave Brubeck starts to play.)

RADIO HOST. Dave Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’—the importance of this band can’t be stressed enough… (voice fades out).

Act 2.

Somewhere in the West

Right side of the stage lights up where there is a family in the living room listening to the radio. On the white sheet a journey across the border is projected. The radio plays pop music.

AUNT. Did you hear that Dave Brubeck visited East Germany and Poland?

HANNA. Mommy, who is Dave Brubeck?

JÖRG. Gosh, how can you be so dumb?

AUNT. A famous US jazz player. Do you know his saying: ‘No dictatorship can tolerate jazz?’ (Switches off radio and moves to turntable.) Let me put the vinyl on… Dave Brubeck band, Jazz fights communism.

(Music starts.)

HANNA. I know this song! They played it on the West German Radio!

AUNT. Amazing, right?

MOTHER (mumbles to herself). Don´t you put such ideas into her head, jazz and stuff. (Out loud:) But anyway, let’s finish packing now.

(MOTHER spreads bills of Western Marks into the fake bottom of the suitcase. HANNA hands her mother two copies of Bravo magazine.)

AUNT (fastening an antique medallion around HANNA´s neck). Let me put this on you. It belonged to your great grandmother, it is yours now, Jörg will not wear it. Family treasure.

HANNA (puzzled). Thank you.

MOTHER (wiping away tears). Here, Hanna, put these two pairs of jeans on, they are too skinny for me to wear. First your pair and then the one for Olga that is bigger.

HANNA (pulls off her old trousers and is not concerned about JÖRG staring at her and then pulls on the two pairs of jeans). It looks ridiculous. I look ridiculous!

JÖRG. Yeah, you look like an elephant.

HANNA. I don’t care, I just want the jeans.

MOTHER. Act normal at the border. They won’t search a child.

HANNA. I’m not a child. I don’t look like a child.

MOTHER (looks at the fake bottom of the suitcase, to herself). It’s still visible, they will find it.

AUNT hands over a vinyl with Madonna to HANNA, she receives it with great joy. They add it and some cans of pineapple, chocolate, and coffee into the suitcase. MOTHER finishes packing and closes the suitcase.

MOTHER. So, see you Jörg in the summer at Balaton.

MOTHER and HANNA walk behind the curtain.

Act 3.

MOTHER’s and HANNA’s flat.

The left side of the stage is lit up. MARIA and HANNA sit at the dining table. They are drinking lemonade out of the bottle.

MOTHER. Did you do your homework?

HANNA. Yes, we had to write an assignment about building socialism. I’ve written three and a half pages!

MOTHER. Really? What did you write about? Show me! (Taking the paper that HANNA hands over, reads:) ‘When I am older… we will all be free from imperialist oppression… Nelson Mandela is free… We have cars for everyone… I will love jazz, the music based on improvisation so that socialism does not become a dictatorship.’

Are you crazy, Hanna?! You can’t write this! Your father will lose his job!

MARIA. Why?

(MOTHER rips out the pages from the book.)

MOTHER. Arghhh, I am late … I’ll be back in a couple of hours. Go sunbathing, or swimming. The weather looks lovely. Don´t sit in front of the TV, there’s nothing on…

HANNA. Mom, where did you put those French fashion magazines?

(MOTHER leaves the stage. Girls look for the magazine and find some scarves.)

HANNA. Wow! I’ve never seen them. So beautiful!

MARIA. I wish we could take them to the Balaton.

HANNA. I think they make these in France.

MARIA. Is it next week that your cousin is coming?

HANNA. Yes, they’re going to stay with us for almost a month. Can you imagine? My mother wants to spend more time with her sister since grandma died, I guess. They could have left Jörg at home.

MARIA. What´s he like? Does he smoke?

HANNA. Jörg? No, he’s a weirdo. He doesn’t speak much, you know, the kind who thinks he knows everything better. He’s in his room all the time, just playing Nintendo.

MARIA. Do you have a picture of him?

HANNA. Why are you interested? He is not a boyfriend material?

MARIA. Don’t be stupid. Show me.

HANNA. You will have plenty of time with him at the Balaton. They have rented a fancy house for all of us to fit there.

MARIA. Awesome!

HANNA. I’m glad you are coming along, it will be fun, you’ll see.

(Light dims.)

Act 4.

Lake Balaton

Light comes up on the left side. JÖRG is frantically looking for the girls in front of a solid fence. HANNA and MARIA are behind the fence.

HANNA (crouched). Get down! He can see us!

MARIA. Ok, we lost him.

HANNA. Let’s go see the bike race! Maybe we will be on TV!

MARIA. Whaaaat! Is the TV crew there?

HANNA. Yes! How could we get to the very front?

MARIA. Easy! You saw how they painted the front of the houses? We could get around there, backyards are always open. To get to the front, we will run around the back. The foreign delegations will be in the front too.

HANNA. They did a bit of lift up for sure, this street used to look like a dump…. Well, it is still a dump from the back. Yack!

MARIA. Wait, my leg got stuck in this shit. What is this? Hell. What a mess.

HANNA. Some paint. Careful, there is some broken glass there and rubbish that looks suspicious.

MARIA. Yeah, the same paint they used for the front of this house, look.

HANNA. Bright and shiny on one side and dirty, stinky, and full of rubbish on the other side. What a shitty place, huh?

MARIA. Hey look, Jörg is coming…

HANNA. Shit, he saw us. Let’s hide in the church.

(Lights go off for a moment. The church interior is projected on the sheet.)

HANNA. Come on, I have something to show you. Now you have a chance to sniff and touch a corpse.

MARIA. That is disgusting, I will never do that.

HANNA. It’s not a big deal. I’ve done it many times. Come and see! (they walk over to a corpse laid out on a table) Look at the face, how clean and beautifully prepared he is, smells like perfume!

MARIA. The flowers are nice. Are they from wax paper? I would love to have one of these…

HANNA. Touch, here, just the face, it is OK.

MARIA. It freaks me out.

HANNA. How about a hide-and-seek? The corpse is the base.

(The lights go off and on. The girls run into JÖRG on the town bridge. It is raining. An old Bravo magazine wet on the pavement.)

MARIA. Look! A new Bravo! Oh—look—Sinéad O’Connor’s new album on the cover!

JÖRG. This place looks familiar. I have seen it somewhere already… Was it not on TV?

(HANNA picks up the wet magazine and it falls apart.)

HANNA. Such a pity! All ripped up! Damn!

MARIA. This is the bridge that….

HANNA. Shhhhsss

JÖRG. What is the story?

HANNA. Oh, we can’t tell you, sorry, no way! Maybe in a hundred years.

Act 5.

On the Beach

Lights off. Behind the sheet only silhouettes are visible. Balaton beach is projected on the sheet. Murmurs in German, Hungarian, Czech, Romanian, and Polish merge with the sound of children screaming and splashing water. Naked people on the beach on projection.

HANNA. It’s sooooo hot. I’m dying. Can’t wait to get into the water.

MARIA. Race you.

(The girls and MOTHER start to undress, giggling.)

JÖRG. What are you doing?

HANNA. What do you mean? Why are you shouting?

JÖRG. Why are you taking all your clothes off?

MARIA. Huh?

HANNA. What do you mean?

JÖRG. Don’t you have bathing suits?

HANNA. Why would I need it? Nobody’s wearing them.

AUNT. Oh. Sorry Jörg, I forgot about you. This is a nudist beach. We used to come here with our parents. You and I can keep our bathing suits on. It’s no problem.

JÖRG. But… But…

HANNA. Weirdo.

MARIA. Yeah. Such a weirdo…

JÖRG. Whatever!

MARIA. Do you wanna come with us? In the water?

(The girls run off.)

JÖRG (to MOTHER). Auntie, I have something to tell you. The girls are really strange. Could you please tell them to behave normally? Aren’t you worried?

MOTHER: What do you mean?

(Lights off.)

Act 6.

In the Balaton House

Light comes up, girls are in Jörg’s room playing Nintendo.

MARIA. This is so cool! One more round? We are getting really good at this! I bet we would beat Jörg!

HANNA. Yeah—if ever. He would kill us if he found out.

MARIA. Why is he so annoying? He is your cousin after all.

HANNA. He is so protective of his stuff, so careful about his Nintendo, his clothes, his hair, his majesty. He is boring. No fun at all.

MARIA. But he smells really nice.

HANNA. Yes, it is his cologne, Aramis. Dad says perfumes are for girls. But I like it too. I wish men here would use it too. I hate their smell.

MARIA. I hate him, he snitched on us and now we’re grounded here at home for the day! He will be at the party for sure tonight.

HANNA. Would your mom let you go to the party? My mom is so strict, she thinks I am a baby.

JÖRG (appearing at the door). What the fuck are you doing? Get out!

Act 7.

The Balaton Party

An opened window is projected upon the white sheet.

MARIA. Make sure the knot is really tight, I do not want to fall down into the bushes!

HANNA. Yeah, yeah, don´t worry… He’s such an ass to go without us.

MARIA. He wanted to go alone. Fair enough.

HANNA. Why are you defending him? Do you love him or what?

MARIA. I’d give him a chance. He has nice clothes and smells nice and we would look cool with him.

HANNA. Did you bring the cigarettes?

MARIA. Yeah, sure. You look so nice with the scarf!

HANNA. French, it can’t look bad.

MARIA. Did you see how cute he looked when he came into the room and shouted at us? It was nice that he did not snitch on us again…

HANNA. He looked like Boris Becker.

MARIA. Oh I love him!

HANNA. Ok, let’s go to the beach. Jörg will be so surprised!

MARIA. Do you think he will wear his perfume?

HANNA. He better do…

(Lights go off, the three youths are behind the curtain smoking together, girls acting drunk, hugging each other, picking some flowers on the way home. They pick up the Bravo magazine.)

(Light comes up in front of curtain. MOTHER comes into the kitchen and picks up the flowers left on the table and smiles. Silence. Light dims slowly.)

THE END

References

Birchall, C. (2011). ‘Introduction to “Secrecy and Transparency”: The Politics of Opacity and Openness’. Theory, Culture and Society, 28(7–8), 7–25, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276411427744

—— (2016). ‘Managing Secrecy’. International Journal of Communication, 10, 152–63, http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4399/1528

Davies, B., and Gannon, S. (eds). (2006). Doing Collective Biography: Investigating the Production of Subjectivity. Open University Press

Derrida, J. and M. Ferraris (2001). A Taste for the Secret, trans. by G. Donis. Polity Press (Original work published 1997)

Figes, O. (2007). The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin’s Russia. Macmillan

Fitzpatrick, S. (1999). Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s. Oxford University Press

Gable, E. (1997). ‘A Secret Shared: Fieldwork and the Sinister in a West African Village’. Cultural Anthropology, 12(2), 213–33, https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1997.12.2.213

Jones, G. M. (2014). ‘Secrecy’. Annual Review of Anthropology, 43, 53–69, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-030058

Keightley, E. (2010). ‘Remembering Research: Memory and Methodology in the Social Sciences’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(1), 55–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570802605440

Millei, Z., Silova, I., and Gannon, S. (2022). ‘Thinking Through Memories of Childhood in (Post) Socialist Spaces: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times. Children’s Geographies, 20(3), 324–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1648759

Richardson, L. (1997). Fields of Play: Constructing an Academic Life. Rutgers University Press

Saldaña, J. (2011). Ethnotheatre: Research from Page to Stage. Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315428932

Simmel, G. (1906). ‘The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies’. American Journal of Sociology, 11(4), 441–98

Taussig, M. T. (1999). Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford University Press

Van Manen, M., and Levering, B. (1996). Childhood’s Secrets: Intimacy, Privacy, and the Self Reconsidered. Teachers College Press

Verdery, K. (2014). Secrets and Truths: Ethnography in the Archive of Romania’s Secret Police. Central European University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9789633860519