Introduction

The Anarchive of Memories:

Restor(y)ing Cold-War Childhoods

© 2024 Mnemo ZIN, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.00

How can we curate a collection of childhood memories to highlight multiple and multilayered stories beyond the fixed thematic organisation of a traditional archive? How can we archive memories in ways that offer audiences an opportunity to make their own interpretations and create new connections across memory stories, while inviting them to share memories in return? How can an archive be reflexive of its own creation, growth, and transformation, continuously arranging and rearranging, adding and affirming, disrupting and challenging the memories kept there? These questions guided the creation of this book, challenging not only ways of archiving ‘data’ but also the idea of memory as witness to history and complicating interpretations of childhoods lived during the Cold War. This chapter introduces readers to the anarchive, an evolving assemblage of childhood memories, artworks, scholarly articles, pedagogical frameworks, and methodological interventions that came out of our project ‘Reconnect/Recollect: Crossing the Divides through Memories of Cold War Childhoods’. It explains connections between memory work, collective biography, childhood studies, and the Cold War, and it offers some suggestions for engaging with the anarchive, including multiple thematic, artistic, and affective threads that we have found interesting, insightful, or surprising. This chapter is an invitation to enter and explore the memory anarchive.

Even in a world where data of all kinds are constantly collected, sorted, exhibited, and archived, there is still a lot of ‘missing’ data. Mimi Onuoha’s multimedia installation ‘The Library of Missing Datasets’ (2016) draws attention to these blank spots in the otherwise data-saturated world. By calling these datasets ‘missing’, she points to the ways in which the colonial matrix of domination is reflected in and relies on particular approaches to data collection and knowledge production. She explains on the project’s website, ‘That which we ignore reveals more than what we give our attention to. […] Spots that we’ve left blank reveal our hidden social biases and indifferences’. Indeed, when libraries and archives draw upon predefined categories to institute a particular imaginary of society, cultural memory, and global (dis)connections, they leave parts of the population—women, children, or minoritised ‘others’—unable to shape the archived content even when this content relates to and impacts their immediate lives and possible futures (Mbembe 2002; Vierke 2015).

Our book assembles some of these ‘missing’ data by restor(y)ing childhood memories from both sides of the Cold-War divide and sharing these memories (and their interpretations) in academic and artistic forms. It gathers those memory stories that were either erased or forgotten, delegitimised or essentialised, or, at best, reinterpreted nostalgically within continuing and rearticulated Cold-War power hierarchies, as well as public and scientific frameworks. It talks about silences that hid family secrets before 1989 as well as struggles and opportunities that accompanied geopolitical changes after 1989—from the economic turmoil and disintegration of the societal fabric to the new freedoms and expectations that unlocked promising possibilities for some people and hollowed out possible futures for many others. Our book brings into focus the colonial matrix of power that continues to shape people’s lives after the Cold War by replacing the socialist version of modernity with the western capitalist one, that is, by merely reproducing the historical and existing divides. It offers a glimpse into what it felt like to wake up to the erased past and face ‘a new reality of multiple dependencies and increased mental, if not economic and social, un-freedom, invisibility to the wider world and the continued forms of silencing and trivialisation by the dominant discourses of neoliberal modernity’ (Tlostanova 2017, p. 2).

This book approaches the Cold War as a period in time characterised by intensified political and military conflicts between two alleged superpowers—the US and the USSR—which resonated in children’s lives directly or indirectly across the globe. Often it unequivocally shaped their political points of views or offered civilisational frameworks, shaped adult-child relations, disciplined embodiment, mounted secrets and concerns for children, and materialised in their everyday life circumstances. At other times, the omnipresence of the Cold War faded, such as in children’s free time or in their engagements with/in nature. Although the legacies of the Cold War continue to shape life trajectories in post-socialist contexts, many memories associated with this historical period either remain muted or become highly politicised. When memories of everyday childhood experiences are exhibited in museums—often alongside toys and other paraphernalia—they may attract tourists, but they can further alienate or add to the anxiety, disillusionment, and frustration felt by many people who struggle to find answers to their pasts and uncertain futures in spaces that continue to live with the enduring legacies of Cold-War divides. Art resurfaces to question and (re)form and (re)frame identities and relations in intergenerational spaces. Among many examples are Dasha Fursey’s paintings of pioneer girls that challenge assumptions about the devotion of youth-organisation’s members to communist heroes and ideologies (see Yurchak 2008).

By (re)connecting people with their pasts, presents, and futures through collective memory work, our book is an attempt to (re)collect and restor(y)e childhood memories shared by those who have been historically denied subjecthood—all those so-called ‘others’ who live/d in socialist and post-socialist societies. It foregrounds varied and contextually diverse children’s experiences of everyday life which by nature perhaps are less structured by state institutions and ideological discourses, and have many similarities with children’s experiences in the capitalist countries. Collectively, these memories multiply histories and complicate interpretations of childhoods lived during the Cold War.

We explore children’s lives ‘through memories’ (Millei, Silova, and Gannon 2019) in which children exhibit agency, making sense of and purposefully acting in the world, following their own interests, and skillfully reading and negotiating intergenerational power relations. We understand memories as stories that tell about the past in the situated present with a view of the future and in which the past events are reconstructed from memory fragments with the help of imagination (Keightley and Pickering 2012). Therefore, we do not claim that they are true representations of historical events; rather, they are created in situations in which the memory sharers are being affected by prompts or events occurring in their lifetime.

Some of the memory stories assembled in this book come from memory workshops, while others spring from memory books, diaries, old photographs, and dusty boxes containing family archives. Unlike methodically organised records kept in traditional archives, the memory stories assembled here take you on a journey that is at once infinite and intricate, constantly shifting, branching, entangling, and perhaps even disorienting—a spider web of sorts. These memories spin ‘data threads’ that resist ordering, weave stories that question and complicate official historical narratives, and carry emotions that exceed any archival categories. Becoming a spider, its prey, or a part of the thread, you are about to join this journey, too.

Welcome to the Anarchive

An anarchive may be best defined by what it is not. First and foremost, it is not a physical and static archive in the traditional sense; it does not function to control and shape knowledge through the selective storage and classification of material, nor to regulate access to data. Neither is it ‘a site of knowledge retrieval’ that relies on data ‘mining’ without paying attention to their particular placement and form (Stoler 2002, p. 90). Refusing to separate (or extract) the archived information and documents from their authors and contexts—a process described by Achille Mbembe (2002) as ‘dispossession’ and ‘despoilment’—the anarchive binds together seemingly disparate fragments of ‘missing’ data (for example, texts, material objects, bodies, memories, movements, performances, emotions, and lived histories), engendering reciprocity, building relations, and opening new possibilities of seeing the world. In our book, the anarchive restores but also restories the conventional narratives and official histories of the Cold War, a bygone era that is mostly memorialised in political terms and interpreted with construed binaries of East-West.

Second, the anarchive actively defies the control of the archivists (or historians) who use their authority to control, regulate, and govern the archived knowledge and materials. Archives exercise ‘hermeneutic privilege’ (Derrida and Prenowitz 1995) by classifying their material and thus already ascribing the stored data with a pre-set meaning. By selecting some materials (over others) for preservation, they define how and whose biographies will be accessible (Jakobsen and Beer 2021). While many archives today are open for citizens to retrieve information or to add their collected materials, the anarchive intentionally emerges from community-based, collective, and collaborative processes, ‘opening up dynamic possibilities that push archival impulses in new and urgent directions’ (Springgay, Truman, and McLean 2020, p. 205). In our work, the anarchive sprung from collective-biography workshops, which brought together academics and artists from both state post/socialist and capitalist societies to remember their childhood and schooling experiences during and after the Cold War. The aim was not necessarily to give witness to an era but, rather, to explore together the textures of everyday life through sharing childhood memories. It was about paying attention to the ways in which historical events are narrated, interpreted, and restor(i)ed through sharing and interrogating of one’s own experiences. Collective biography collapses the binary that separates the knowledge-generating expert from the memory-recalling layperson and, ultimately, from the archivist recording and cataloguing it. Within the intersubjective sharing spaces, the intensity and affective flows of memories make them collective as listeners feel themselves within the tellers’ stories (Davies and Gannon 2012; Foster et al. 2023) and sense the emerging connections across times and places.

Third, anarchives are not static and can never be complete as their organising idea and logic escape the urge for control and ordering. Thus, we work with ‘an an-archic energy’ that eclipses regulation and engages with and against the archive’s own failures and utopian urges for mastery (Ring 2014, p. 388, with reference to Foucault and Derrida). This energy keeps the stories and the anarchive on the move—merging, mixing, connecting, but also juxtaposing personal experiences, public memory, political rhetoric, places, times, themes, and artifacts. In addition to memories, the anarchive spills into theater performances, artworks, museum exhibitions, films, academic courses, and more.1 These are all anarchival forms that contain and prompt collaborative interactions that then go on to produce new anarchival forms and encounters. In this sense, the anarchive is a practice that ‘catches experience in the making’ and that ‘catches us in our own becoming’ (Manning 2020, p. 84). What may have once appeared as discrete, isolated, and immobile pieces of archival data come to vibrant life in the anarchive, ‘making it other than it is just now, and already more than what it was just then’ (Massumi 2015, p. 94) as collective memories carry all involved beyond their own selves.

Finally, the anarchive does not act to preserve the past, a function generally performed by traditional archives. Rather, it acts to re-configure the present and re-story possible futures. By refusing the linear flow of time, the anarchive works ‘to germinate seeds for new processes’, thus carrying the potential to unmoor the shape of the events and the contours of future possibilities as they reveal themselves today (Manning 2020, p. 94). In our work, we too endeavoured to move beyond storing undocumented experiences and childhood memories that problematise the representation of the past. Our purpose became to reimagine the future by actively ‘undoing and unlearning’ dominant categories and cartographies by restor(y)ing childhoods (Springgay et al. 2020; see also Tlostanova and Mignolo 2012). In this process, we were inspired by Foucault’s (2002) idea that the ‘archive is not something which belongs to the past but something which actively shapes us’ in the present and future (cited in Agostinho, Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Grova Søilen 2019, p. 5). Building on the notion of anarchiving as a ‘feed-forward mechanism’ in a continuously changing creative process (Massumi 2016, cited in Springgay et al. 2020, p. 897), we were curious to explore what our anarchive could do in the present-future through disrupting narratives, or how it could depart from established archival techniques and procedures in restor(y)ing pasts, presents, and futures.

Thinking with decolonial, feminist, and post-structural theories of the anarchive, we asked ourselves: What datasets are missing from research and artistic work on everyday childhoods lived during the Cold War? What exclusions have a bearing on its aftermath? How do missing datasets—such as untold memories of personal experiences (forgotten or repressed), hidden objects, or dusty photo albums—disqualify, marginalise, and erase knowledge and ways of knowing and being otherwise? What remains unknown and unimaginable as a result? Moreover, as we reflect on our knowledge production, how can we practice a continuous critique of our own knowledge creation with the anarchive in ways that remain inclusive, while generating affective relations, new connections, and meaningful dialogues?

***

The memory stories which compose this growing anarchive originate from the ‘Reconnect/Recollect’ research project, which brought together more than seventy scholars and artists from thirty-six countries (across six continents) to share their childhood experiences during the Cold War. We gathered in places marked by old borders and newly erected walls: in Berlin (a city divided into East/West during the Cold War), Riga and Helsinki (two cities serving as Baltic Sea ports and marking the borders of Europe), and Mexico City (in close proximity to the most recently built wall at the Mexico–U.S. border), with additional workshops being held online for those unable to travel. We approached memory work via collective biography, foregrounding the shared generation and analysis of memories through processes of telling, acting, sensing, listening, reflecting, writing, rewriting, sharing, and collectively exploring and interrogating our memory stories (see, for example, Haug et al. 1987; Davies and Gannon 2006; Gonick and Gannon 2014; Hawkins et al. 2016; Silova, Piattoeva, and Millei 2018). From this perspective, childhood memories extend beyond the individual, connecting private and public remembering and collective interpretations in multifaceted and reciprocal ways (Millei, Silova, and Gannon 2022). Each telling of a memory story calls forth more stories—you hear one, you tell one—mobilising resonances and highlighting nuances of difference and detail between stories.

All of the memory stories produced during our collective-biography workshops and collected through exhibitions or our website make up a diverse, multivocal, and uneven collection. This digital, online, and open-access archive of over 250 childhood memories in 13 languages (https://coldwarchildhoods.org/memories/) invites further explorations of lived childhoods as we continue to remember and share memories. Personal memories are a key element in understanding the ‘forces that sustain continuities in the social world’ and humans’ relations with the world (Fox and Alldred 2019, p. 31). Memories are, thus, ‘territorializing forces moving bodies and initiating repetition’ (ibid., p. 24); they uphold, shape, and reconfigure social processes and relations, recreating pasts, presents, and futures. As the scope and scale of the collection expands, so does the ever-growing internal web of inter-references, producing new meanings and connections across memories. In this sense, the digital collection of childhood memories is only ‘a passing point’ (3ecologies 2023), a springboard for the anarchive to expand into artworks, films, fictional stories, and more:

[Such expansions are] activated in the relays: between media, between verbal and material expressions, between digital and off-line archivings, and most of all between all of the various archival forms it may take and the live, collaborative interactions that reactivate the anarchival traces, and in turn create new ones […] organising and orienting live, collaborative encounters. (Manning 2020, p. 93, italics in the original)

As one of its readers, you become a part of the collaborative encounters, intentions, and creative processes that brought this book into being. No matter where or how you begin to engage with the stories presented in these pages, you may ponder these questions: What do childhood memories tell us about the Cold War and its aftermath? How can we archive or anarchive childhood? What bodies of knowledge, emotions, vibrancies are kept in our personal anarchives of memories? What do we archive in our own bodies? How can we explore the affective flows within events and experiences where collective memories may be invoked or mobilised alongside personal memories? How can memories extend history into the future? And what do memories of the Cold War tell us about the Anthropocene?

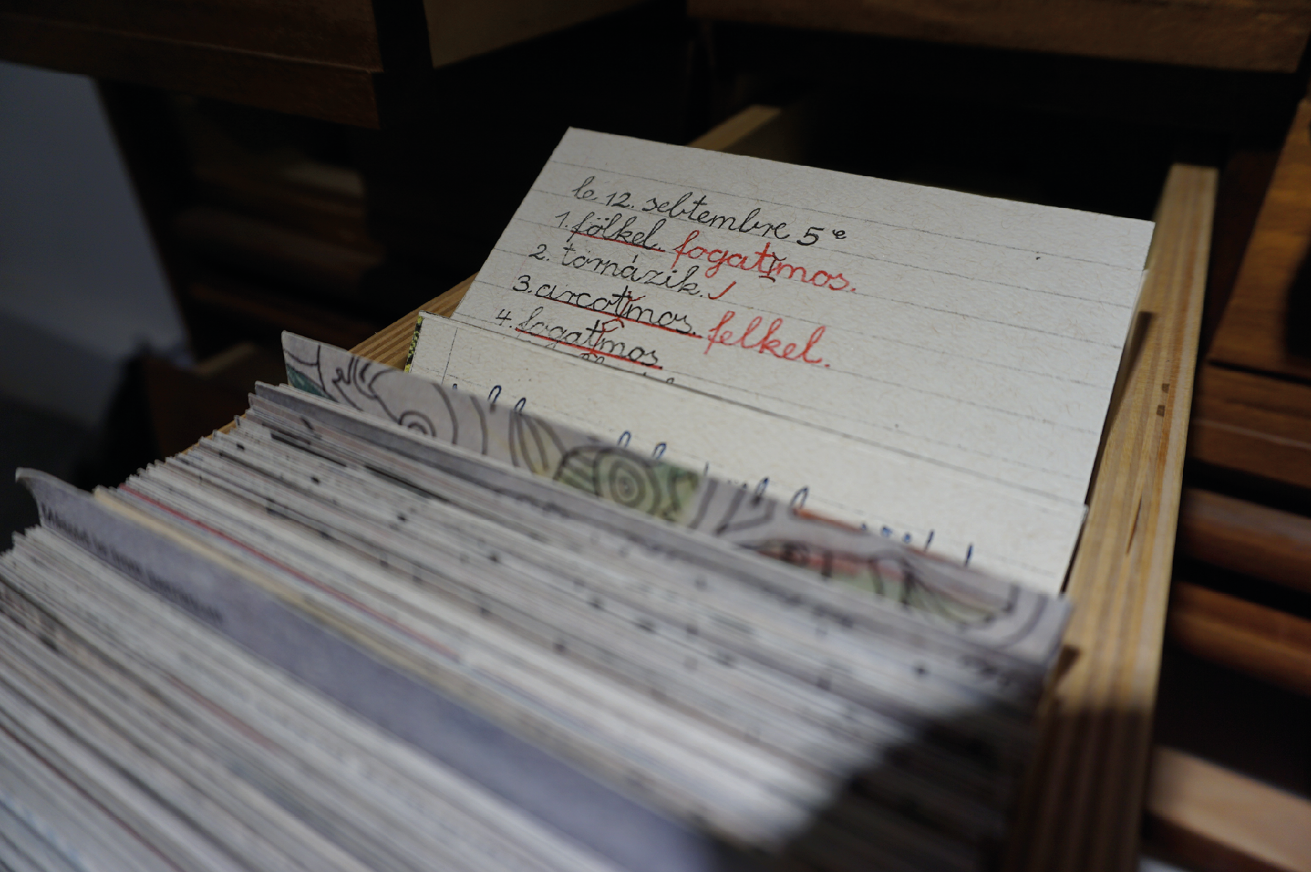

In short, there is no one way to read this book. You may start by picking an entry, a memory story, or an artwork, as you would open a traditional library catalogue, and pick out cards with the book titles that may not link thematically but follow an alphabetical order and connect with your own memories or interests (Figures I.1, I.2, I.3). You might explore the book from an academic perspective or dive into the pages where memory meets imagination in ways that you may find surprising and refreshing. Your own memories, imagination, and insights might start to roam, creating new connections. The book might move you to write your own memories and add them to the anarchive, filing away new entries for the next reader. Or, you may want to simply follow your intuition, only opening some chapters as drawers of the library catalogue, and leaving others shut. Below, we would like to introduce some thematic threads that emerged as we ourselves engaged with ideas across the anarchive. You can follow these sticky threads of childhood memories—or spin your spidery own—as we begin to (re)story childhood memories.

Fig. I.1 Sára Gink, BETŰVÁSÁR—ISBN 963 18 1254 5. Mixed media, 160×190 cm. Photo by Zsuzsa Millei of installation at the ‘Whale of a Bad Time’ exhibition, Budapest 2020.

Fig. I.2 Sára Gink, BETŰVÁSÁR—ISBN 963 18 1254 5. Mixed media, 160×190 cm. Photo by Zsuzsa Millei of installation at the ‘Whale of a Bad Time’ exhibition, Budapest 2020.

Fig. I.3 Sára Gink, BETŰVÁSÁR—ISBN 963 18 1254 5. Mixed media, 160×190 cm. Photo by Zsuzsa Millei of installation at the ‘Whale of a Bad Time’ exhibition, Budapest 2020.

An/archives as Bodies, Bodies as An/archives

While exploring the potential of the anarchive, our interest has extended beyond memory stories, artifacts, and objects to also include the idea of the body, thus interrogating the relationship between ‘bodies’ of archives and ‘archival bodies’ (Battaglia, Clarke, and Siegenthaler 2020, p. 9). On one hand, our anarchive of childhood memories is clearly composed of different bodies (or collective bodies), including bodies of knowledge, documents, photographs, objects, and memory stories—all of which seem to shift in contents and contexts as each reader browses through and engages with them. These bodies of anarchive offer new spaces and forms of collective work, bringing into conversation seemingly unrelated memory stories and objects. For example, a memory of travelling on the train in East Berlin unexpectedly triggers a memory of hearing an underground train pass by towards the other side of the Berlin Wall (see Chapter 15 by Sarah Fichter and Anja Werner), while stirring a broader conversation among listeners and readers about their experiences of border-crossing during the Cold War. Suddenly, we see traces of the train tracks criss-crossing the canvas in Hanna Trampert’s paintings (Chapter 3) inspired by these memory stories. And in this process of anarchiving, the collective bodies of knowledge, experience, and art trouble the existing divides, while highlighting connections.

On the other hand, bodies also act as archives of knowledge, sensations, and feelings of the world. As Battaglia et al. (2020) note, ‘archives are not only bodies of documents and knowledge, but also something fundamental to the body; the body is an archive, bodies are in the archive, and researchers intervene in either the material bodies of objects, files, or images that make up the archive’ (p. 9, italics in the original). In memory workshops we did not only brainstorm but also body-stormed our personal memory archives, asking the participants to remember from the body: ‘how did it feel, how did it look, what were the embodied details of this remembered event?’ (Davies and Gannon 2006, p. 10). The writing of memories, too, focuses on the moments in which the body resists the effects of narrative structures that might impose linearity, causality, or closure. Writing, therefore, must be initiated ‘from the body, not telling the story how it should be told, but as it is lodged in the body’ (ibid.).

From this perspective, the traditional ontology of the archive is seriously challenged. Memories are, as Hart (2015) suggests, archived ‘into/onto’ the body and also move bodies as stories take shape and build new connections. The body is, thus, both a container of archival material and a powerful medium. In this process, the multisensorial, relational, affective, and embodied knowledge becomes animated and the body begins to ‘speak’. In the words of the author and psychoanalyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés (1989),

[the body] speaks through its colour and its temperature, the flush of recognition, the glow of love, the ash of pain, the heat of arousal, the coldness of non-conviction. It speaks through its constant tiny dance, sometimes swaying, sometimes a-jitter, sometimes trembling. It speaks through the leaping of the heart, the falling of the spirit, the pit at the centre, and rising hope. The body remembers, the bones remember, the joints remember, even the little finger remembers. Memory is lodged in pictures and feelings in the cells themselves. Like a sponge filled with water, anywhere the flesh is pressed, wrung, even touched lightly, a memory may flow out in a stream. (p. 198)

In our book, ‘bodies’ of archives and ‘archival bodies’ are constantly entangled with each other. Bodies appear as historical symbols of the ideal future and instruments of soft power. Bodies are put on display in sports, parades, and performances (see Chapter 10, by Stefanie Weiss and Susanne Gannon, on children in elite sports or Chapter 2, by Pia Koivunen, on children’s participation in parades during Gorbachev’s visit to Finland). We come across carnal bodies—flesh, blood, strength, dexterity, agility—which are trained, capacitated, and skilled, while at the same time storing the memory and emotionality of these exercises. Bodies are also inseparable from their material and sociopolitical contexts as they are subjected to discourses, practices, affect, and ideals (see Chapter 9 by Katarzyna Gawlicz and Zsuzsa Millei on menstruation). There are dead bodies—both human and more-than-human—which are archived in children’s memories, revealing how, even in their inert form, bodies can move children and continue to move them as the now-adults narrate their stories (see Chapter 8 about secrets by Irena Kašparová, Beatrice Scutaru, Zsuzsa Millei, Josefine Raasch, and Katarzyna Gawlicz or Chapter 13 by Raisa Foster on upcycling artworks). Bodies of all kinds are figuring in memories, photographs, and paintings, extending the archive into, onto, and across bodies, expanding the archive in embodied ways (see the artworks by Raisa Foster and Hanna Trampert). As you dive deeper into this anarchive of childhood memories, listen to how your own body archive is moved by the stories and what might arise in response.

Memory as Affect

Memories are created and take shape through affective pulls, relations between and across beings, times, spaces, places, feelings, historical events, and more (Reading 2022). Approaching memories as affect that has the capacity to move things, create realities, cut across many divides—the personal/collective, real/imagined, human/more-than-human, true/subjective—highlights ‘how memories materially affect the world (just as they are themselves affected by events)’ (Fox and Aldred 2019, p. 21). For example, social expectations shape the process of remembering and, in turn, the event remembered affects the identity and subjectivity of the memory-story teller. As Petar Odak explains in Chapter 1, in a memory workshop exploring the Cold War, the expectation is often to share memories with a particular political charge and to avoid describing mundane events that might be perceived as unsuitable or uninteresting. The context, thus, affects the choice; this, in turn, negates subjectivities and, in this case, the importance of one’s being a ‘regular’ child. The choice of remembering and forgetting thus exposes the micropolitics of memory work.

Memory as affect also moves artwork. While painting inspired by her memory, Hanna Trampert remembers how something begins to crystallise and come to light, something that she feels must be dealt with. Trampert explains, ‘actually, my art is about becoming conscious and, of course, about an aesthetic experience’ (personal communication, 2022). She recalls how her memories of childhood lay dormant until our memory-workshop invitation made her work with them, inspiring a whole new series of paintings in which she explores the metaphysics of memory. Others in the workshops also recounted how childhood memories moved and energised them to explore their childhoods that also brought into their adult life’s forgotten subjectivities. Memories and art as affect also move participants and authors closer. The various memories and artwork introduced and discussed in this book are more ‘concerned with advancing collaborative ways of knowing and representation than with individual expertise and recognition, with advancing a more serious invitation for those with visceral experience of oppression to collaborate with the learned and cultured in the creation of knowledge that heals’ (Moreira and Diversi 2014, p. 298).

The ‘ethical and affective spaces of inquiry’ (Gannon et al. 2019, p. 50) open real alternatives to the contemporary academy and its dominant culture of individualism, extractivism, competitiveness, and narrow specialisation. This process of reclaiming science, not as an academic institution but rather as a collective space of concerns for the world, entails the need to recuperate and heal ourselves as scientists as well. As Isabelle Stengers (2018) explains, we are ‘sick’ from being locked in a form of knowledge production that is bound by capitalist production and competition. This book is an attempt to recuperate from this sickness and to

becom[e] capable of learning again, becoming acquainted with things again, reweaving the bounds of interdependency. It means thinking and imagining, and in the process creating relationships with others that are not those of capture. It means, therefore, creating among us and with others the kind of relation that works for sick people, people who need each other in order to learn—with others, from others, thanks to others—what a life worth living demands, and the knowledges that are worth being cultivated. (Stengers 2018, pp. 81–82)

For us, the affective (and emotional) force of this ‘collaborative praxis’ (Tlostanova et al. 2016, p. 2) and friendships are at the very core of surviving and meaningfully co-existing in academia—and the world more broadly—today.

Memory-work as Worldmaking

The Cold War provided collective-biography-workshop participants and some of the chapter authors a frame in which to raise questions about who counts as a ‘real’ contemporary with an ‘authentic’ first-hand experience of the historical period. Some of those who were brought up in non-socialist societies felt they could not personally add to the explorations. For example, see reflections shared by Pia Koivunen (Chapter 2), Elena Albarrán (Chapter 14), Inés Dussel (Chapter 7), and Erica Burman (Chapter 4). Others looked to such listeners for the criteria to decide which memories to recall, seeking reasons to judge a memory as ‘worth’ sharing in a group and to judge other memories as too generic or mundane to share. Thus, the Cold War operated as an active force in participants’ decisions about how to evaluate their own experience and participation or how to invoke the desired response from their listeners (see Chapter 1). By highlighting the objects and materialities, such as colours, smells, textures of everyday life, stereotypically represented as symbols of the Cold War, some childhood memories inadvertently recreated divides or gave witness to the conjured myths about the ‘Other’ (see Jennifer Patico’s chapter, Chapter 6, on mythical objects and Ivana Polić’s argument in Chapter 12 about the connections made by objects). Rare time-spaces encountered in the memories of Cold-War childhoods, such as the Berlin ghost metro stations (Chapter 15 by Sarah Fichtner and Anja Werner), or occupied by children during unsupervised times (Chapter 11 by Nadine Bernhard and Kathleen Falkenberg) offer glimpses into how infrastructures and gendered work were interpreted in memories to create the textures of real or imagined Cold-War divides and existence.

How memories are judged as research data or the ways in which memory work is considered as methodological practice also hinge on onto-epistemological and disciplinary assumptions. These decisions in turn make up scientific worlds and construct the routes that researchers must take to arrive at a fruitful and rigorous memory work (see Pia Koivunen’s journey highlighting her concerns about the use of memory in historical research in Chapter 2). Working with memories thus does not only connect to the past worlds but also constructs the world present in the memory works and disciplinary fields of analysis.

Secret/ive Memories of Children’s Worlds

Reading across the chapters, we can see how ideology and divisions motivated children to ignore official lines and to disguise their resistance to norms and prohibitions. The politics of the public space folded onto the home space, creating secrets. The intricate practices of childhood secret-keeping mirrored the binary of official- and private-life secrets in the public culture of Czechoslovakia portrayed in the ethnodrama by Irena Kašparová and her colleagues (Chapter 8). Some were open secrets—ones transparent and known to everyone, but their status as secrets was, nevertheless, preserved. Those could not be uttered out loud, only whispered. The ethnodrama shows how children eagerly learned to keep secrets but sometimes slipped, even intentionally, imitating the norms that regulated the open existence of secrets. In another example of secretive practices explored by Katarzyna Gawlicz and Zsuzsa Millei in Chapter 9, young girls inherited the culture of menstruation as a taboo despite the official gender equality proclaimed by socialist parties and the inclusion of sexual education in schools. Girls hid the onset of the menarche and handled the blood in secret—one their mothers often knew but pretended not to know. Susanne Gannon and Stefanie Weiss show in Chapter 10 how the soft power of the Cold War manifested in elite-athlete training. The practice hid the unwanted individual sacrifices imposed on children in the name of building socialist nations, demonstrating the superiority of one political ideology over the other. Children also kept secret their pain, boredom, resistance, or the suffering caused by their parents, perhaps trying to avoid problems or seeing the expression of their feelings as futile. In unsupervised times, away from observation by school or family, children generated shared experiences of freedom and contentment; they also experienced loneliness that was not always known by parents (see Chapter 11 by Nadine Bernhard and Kathleen Falkenberg).

Although the keeping or revealing of secrets was mostly harmless, it sometimes carried life-or-death consequences for children or their families. Inés Dussel, a child of a leftist-activist couple growing up in Argentina during the military dictatorship of the 1970s and 1980s, tells in Chapter 7 how she was entrusted with keeping the family safe by keeping its secrets while moving discreetly between temporary homes and school. Keeping secret the family’s location and political views punctuated the child’s everyday life. The adult narrator remembers this childhood experience as the leading of a double life, knowing exactly which details to share and which to keep secret. Such double consciousness characterised everyday socialist lives.

All in all, secrets reveal important aspects of children’s everyday life connecting these experiences across times and spaces. They also trouble the taken-for-granted notions of childhood in societies, such as the innocence or ignorance of children, their lack of competencies compared to adults, childhood’s apolitical nature or the narrow view of children as victims of political agendas. At the same time, we can see how these notions and tropes help narrators to make sense of and (re)story their memories. Secrets help to create alternative spaces, however transient and hidden those might be. These spaces might even emerge in parallel to the creation of alternative worlds by their parents who experienced conflicts due to being estranged from and by the socialist regime (see Madina Tlostanova’s fictional memory story in this book; Burman and Millei 2021).

Memory as Pedagogy

Children’s learning in the socialist societies has been habitually portrayed as top-down and dominated by formal education or public pedagogies relaying official state ideologies. However, a different picture emerges when we examine the learning experiences portrayed in the memories presented in this book. In these, children keenly observe and partake in their everyday environments, in or beyond formal schooling. They collect, engage with, and puzzle together over many things—adults’ minor gestures, gossip, smells, colours, textures, snippets of news in the media, and the presence or absence of consumer products—to create their own understandings of life. Memories particularly attune us to learning that is fluid and emerges relationally with everyday objects or affective atmospheres, and they foreground a type of learning beyond the notion of conscious sense-making. For instance, girls learned about the controversial status of women in their respective societies through their experience of a scarcity of feminine-hygiene products. Moreover, by handling self-made menstruation pads or by observing and connecting other objects and conditions—from stains on clothes to female pets in heat—they developed an understanding about menstruation amidst the silence of adults. They invented their own intimate and intricate practices to regain agency over controversial feelings and bleeding body (see Katarzyna Gawlicz’s and Zsuzsa Millei’s exploration of menstruation in Chapter 9).

Sometimes objects instigate children to misbehave and learn about ‘the other’ beyond the official narratives, such as in the case of a child pressing the forbidden buttons on a TV-set in East Germany (see Chapter 12 by Ivana Polić). Learning with objects is induced by and induces different affective states, including pleasure, curiosity, and desire that are less frequently referenced in research or media depicting everyday life and consumption in socialist societies. The affective and sensory experiences of the ‘other side’—mediated by clothing catalogues, photographs, TV-programmes, or make-up—serve as a means of getting to know the West and the world at large but also of engaging in relationships at home. Experiencing the West often entwines with children’s own maturation, developing perceptions of themselves, and their intergenerational relations (see also Chapter 6 by Jennifer Patico). Curiosity about ‘the other’ flourished on the Western side of the Iron Curtain, too, with children questioning the official narratives and developing their own interpretations of ‘the other’ through literature or music (see more in Ivana Polić’s Chapter 12).

The anarchived memories operate as pedagogical devices in academic teaching and learning with the more-than-human world that both socialist and capitalist modernities perceive as a passive object of learning for perpetual extraction and progress. Elena Jackson Albarrán, in Chapter 14, describes how the course in comparative Cold-War childhoods she created for the post-socialist generation born in the 2000s intimates the diversity of Cold-War experiences and helps to understand the role of individuals as historical actors navigating historical forces then and now. Memories shared by family members and recorded and analysed by students make a distant history matter in the present in ways that a detached description of historical events and actors cannot achieve: the nuances and inconsistencies of history, the subjectivity of human actors, and the permeabilities of the Iron Curtain come into sharp focus (see also Chapter 2 by Pia Koivunen). By engaging students with the stories and the popular culture of the Cold-War period, learning with memories is a pedagogical device that reaches beyond historical knowledge to cultivate intergenerational empathy. Memories help us to re-member and re-learn from and with our plant-kin, where both memories and plants act as teachers in the process (Jiang et al. 2023). Here, the learning is bodily, emotional, and spiritual, building on ‘the arts of noticing’ (Tsing 2015, p. 37) the multispecies common worlds we inhabit in our research and practice. Recollecting and learning through ‘eco-memories’ cultivates curiosity, reciprocity, care, and gratitude to plants and other more-than-human companions. In this re-learning, intergenerational and interspecies relationships and mutual vulnerability nourish each other to reinstate the forgotten ways of being in and with the animate world (see Chapter 16 by Jieyu Jiang, Esther Pretti, Keti Tsotniashvili, Dilraba Anayatova, Ann Nielsen, and Iveta Silova).

Restor(y)ing Memory for the Anthropocene

Reading through the chapters in this book, parallels emerge between the two major events in the late history of modernity: the breakdown of the state-socialist systems in Southeast/Central Europe and the former Soviet Union and the ‘patchy’ unravelling of the Anthropocene on a global scale (Tsing 2015). Memories extend history into the present and trouble the feeling of discontinuity between generations and at the same time highlight the multiplicity of futures. State-socialist systems seemed immutable, steadily progressing towards the infinite and bright future of communism (Yurchak 1997). Disestablishment of the so-called Second World was abrupt but unsurprising—sort of expected—by the majority of its people. With its disappearance, the future it had created became unrealised and was discarded. ‘Unrealised’ or ‘unrealisable’ futures destabilise the straightforward assumption that ‘pasts and presents have futures, that things just keep on going, that time and history keep unfolding’ (Wenzel 2017, p. 502). Today, youth and children question the very existence of a future for them. This unrealisable future’s past is what we are living now; it reminds us that we are, in fact, authoring the im/possibility of its very futures now.

Cold-War childhood memories richly animate the triumph of modern technological progress in stories of the infinite growth and the development promised by fossil fuels (see Foster et al. 2022; ZIN and da Rosa Ribeiro 2023). Memories also reveal other ways of relating to the world and other ways of engaging in collective remembering with the inclusion of more-than-human companions. As we listen to the memory stories about the children touching a dead bird, about children listening to the orchestra of bees, or about children engaging with farm animals and plants (see Chapter 16 by Jiang et al.), we recall the moments of our multisensory awareness, recognising our bodily belonging in a more-than-human world. In turn, we might start to remember the relations with Earth and cosmos, while re-animating our capacity for wonder and empathy. Anarchiving incites practices of restor(y)ing, challenging fascination with originality understood narrowly as newness. By doing so, the anarchive confronts the modern desire for progress as a never-ending production of new—the dominant logic that has also extended to artistic work (see Chapter 13 by Raisa Foster). There is an inspiring parallel between upcycling existing materials, ideas, and artworks to create sustainable practices and continuity in the arts and museum practices, and the restor(y)ing of memories for envisioning a future that connects and sustains all planetary companions. Starting with memories that recount our world-making relations, we can story futures that connect generations past, present, and future and that make kin and place without imposing human domination or nature/culture divisions. This is a future that sustains care, reciprocity, and humility for life.

These are just a few threads that we have begun to weave together while reading the book, and we invite you to spin your own threads as you dive deep into the anarchive of memories.

References

3ecologies (2023). ‘Anarchive—Concise Definition’, https://3ecologies.org/immediations/anarchiving/anarchive-concise-definition/

Agostinho, D.; Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K.; and Grova Søilen, K. L. (2019). ‘Archives that Matter: Infrastructures for Sharing Unshared Histories. An Introduction’. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Informationsvidenskab Og Kulturformidling, 8(2), 1–18, https://doi.org/10.7146/ntik.v7i2.118472

Burman, E. and Millei, Z. (2022). ‘Post-socialist Geopolitical Uncertainties: Researching Memories of Childhood with “Child as Method”’. Children and Society, 36(5), 993–1009, https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12551

Craps, S.; Crownshaw, R.; Wenzel, J.; Kennedy, R.; Colebrook, C.; and Nardizzi, V. (2018). ‘Memory Studies and the Anthropocene: A Roundtable’. Memory Studies, 11(4), 498–515, https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017731068

Davies, B. and Gannon, S. (eds). (2006). Doing Collective Biography. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press

Davies, B. and Gannon, S. (2012). ‘Collective Biography and the Entangled Enlivening of Being’. International Review of Qualitative Research, 5(4), 357–76, https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2012.5.4.357

Derrida, J. and Prenowitz, E. (1995). ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’. Diacritics, 25(2), 9–63, https://doi.org/10.2307/465144

Foster, R.; Zin, M.; Keto, S.; and Pulkki, J. (2022). ‘Recognising Ecosocialization in Childhood Memories’. Educational Studies, 58(4), 560–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2022.2051031

Foster, R.; Törmä, T.; Hokkanen, L.; and Zin, M. (2022). ‘63 Windows: Generating Relationality through Poetic and Metaphorical Engagement’. Research in Arts and Education, 2), 56–67, https://doi.org/10.54916/rae.122974

Fox, N. J. and Alldred, P. (2019). ‘The Materiality of Memory: Affects, Remembering and Food Decisions’. Cultural Sociology, 13(1), 20–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518764864

Gonick, M. and Gannon, S. (2014). Becoming Girl: Collective Biography and the Production of Girlhood. Toronto: The Women’s Press

Hart, T. (2015). ‘How do You Archive the Sky?’. Archive Journal, https://www.archivejournal.net/essays/how-do-you-archive-the-sky/

Haug, F. et al. (1987). Female Sexualization. The Collective Work of Memory. London: Verso

Hawkins, R.; Falconer Al-Hindi, K.; Moss, P.; and Kern, L. (2016) ‘Practicing Collective Biography’. Geography Compass, 10(4), 165–78, https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12262

Jacobsen B. N. and Beer D. (2021). Social Media and the Automatic Production of Memory: Classification, Ranking and the Sorting of the Past. Bristol University Press

Keightley, E. and Pickering, M. (2012). The Mnemonic Imagination: Remembering as Creative Practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Massumi, B. (2016). ‘Working Principles’, in The Go-To How To Book of Anarchiving, ed. by A. Murphie. SenseLab, pp. 6–8), http://senselab.ca/wp2/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Go-To-How-To-Book-of-Anarchiving-landscape-Digital-Distribution.pdf

Mbembe, A. (2002). ‘The Power of the Archive and its Limits’, in Refiguring the Archive, ed. by C. Hamilton and others. Dordrecht: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0570-8_2

Millei, Z.; Silova, I.; and Gannon, S. (2019). ‘Thinking Through and Coming to Know with Memories of Childhood in (Post)Socialist Spaces’. Children’s Geographies, 20(3), 324–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1648759

Moreira, C. and Diversi, M. (2014). ‘The Coin will Continue to Fly: Dismantling the Myth of the Lone Expert’. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 14 (4), 298–302, https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708614530300

Onuoha, M. (2016). The Library of Missing Datasets. mixed-media installation, https://mimionuoha.com/the-library-of-missing-datasets

Reading, A. (2022). ‘Rewilding Memory’. Memory, Mind and Media, 1, E9, https://doi.org/10.1017/mem.2022.2

Ring, A. (2014). ‘The (W)hole in the Archive’. Paragraph, 37(3), 387–402, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26418642

Silova, I.; Piattoeva, N.; Millei, Z. (eds). (2018). Childhood and Schooling in (Post)Socialist Societies: Memories of Everyday Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62791-5

Springgay, S.; Truman, A.; and MacLean, S. (2020). ‘Socially Engaged Art, Experimental Pedagogies, and Anarchiving as Research-Creation’. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(7), 897–907, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419884964

Stengers, I. (2018). Another Science is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science. Polity Press.

Stoler, A. L. (2002). ‘Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance’. Archival Science, 2, 87–109, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632

Tlostanova, M. (2017). Postcolonialism and Postsocialism in Fiction and Art: Resistance and Re-existence. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48445-7

Tlostanova, M. and Mignolo, W. (2012). Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas. Columbus: Ohio State University Press

Tlostanova, M.; Koobak, R.; and Thapar-Bjorkert, S. (2016). ‘Border Thinking and Disidentification: Postcolonial and Post-socialist Feminist Dialogues’. Feminist Theory 17(2), 211–28

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873548

Vierke, U. (2015). ‘Archive, Art, and Anarchy: Challenging the Praxis of Collecting and Archiving: From the Topological Archive to the Anarchic Archive’. African Arts, 48(2), 12–25

‘Whale of a Bad Time’ (2020). [museum exhibition]. KUBAPARIS, Budapest, https://kubaparis.com/archive/a-whale-of-a-bad-time

Wenzel, J. (2010). Bulletproof: Afterlives of Anticolonial Prophecy in South Africa and Beyond. University of Chicago Press, https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226893495.001.0001

Yurchak, A. (2008). Dasha Fursey: Utopia at The Roof of the World. Catalogueue for Art Exhibition ‘At the Top of the World’. New York

—— (1997). ‘The Cynical Reason of Late Socialism: Power, Pretense, and the Anekdot’. Public Culture 9(2), 161–88

Zin, M. and da Rosa Ribeiro, C. (2023). ‘Timescapes in Childhood Memories of Everyday Life During the Cold War’. Journal of Childhood Studies, 48(1), 99–110, https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs202320547

1 As we discuss further in this chapter, our project led to multiple types of scholarly and artistic works; it also inspired new memories. All of these compose the anarchive. See https://coldwarchildhoods.org