The Door1

© 2024 Khanum Gevorgyan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0383.23

In 5, 4, 3… she will hear the front door open, and his heavy footsteps will echo in their already 50-year-old, partially renovated yet so warm house. In 3, 2, 1… he will open the living room door, where everyone is waiting for him with tearful eyes, including his three children that do not really realize why he was wherever he was. At exactly 0, according to her counting at least, he will drop his duffel bag wrapped with a few packs of tape. At the time, she thought the tape wrapping was meant to make it easier for him to carry the bag because of the many handles it had. However, now that she has had a fair portion of the world in her pocket, she understands that it was meant to keep the bag safe from those who would try to open it or throw it so hard that the bag breaks. After zero is a scene engraved in her memory forever.

He was a father of three, her—Khanum, being the oldest. Although in the past 2–3 years, he had seen his kids only four months a year, no one could blame him. No one could complain. Neither his wife could voice her longing towards a husband hardly seen, neither the children could cry out for his presence. That was a normality at their schools, neighborhoods, and even family gatherings, where the barbeque could no longer be made by the fathers of the family, so mothers had to get a crash course and teach themselves.

Russia had become the fathers’ land. The mothers’ land Armenia was forced to face not only longing for a loved one but also challenging house tasks, upbringing, and teaching children, and the economic challenges, which were portrayed in her childhood memories as the exchange rate boards that gave her mother a horrifying feeling. The only public display of longing allowed was screaming, ‘Airplane! Bring my father back!’ every time an airplane was seen in any part of the sky. Only children screamed. With mothers’ encouragement, the screams were sometimes so loud, they would deafen one’s ears. One day, her father would be in one of those airplanes, landing in Armenia, and hearing her voice, he would fly faster, get home faster, open the doors faster…

There was no need to count after zero. Not only because she did not know about negative infinities, but also because a few seconds after zero, she was hugging her father. He would always kneel on the floor, open his arms wide like an eagle and wait till one of his children was courageous enough to hug a stranger so familiar. She was not always the bravest. However, after the three of them were in his arms, everything else would go silent, at least for her. She would not hear or see her grandma drying her eyes, her uncle screaming, ‘Someone, give me coffee!’ or her mom crying, having ‘Armen’, her father’s name, on her lips. Nothing else mattered, aside from the taped duffel bag full of Russian chocolate. The next stop after her father’s embrace would be the bag full of chocolates and gifts. The three of them literally made a jump towards the bag and ripped the tape apart, while their father was hugging the rest of the family members.

The siblings, excited with their gifts and the unlimited amount of chocolate, were planning on which candies they were to take to school and share with classmates to show off their father being back from Russia. The happiness was cut short, however. The mother, Azniv, rushing from the kitchen with a huge kompot2 jar in her hand ordered the kids to put all the chocolate in the jar, so she could keep some for the New Year table. This was the mark of winter for the children because from then on, they would go on a secret mission to find this jar and destroy the chocolate way before the New Year’s Eve. The best part about this was that they worked individually. If one found the jar hidden in mother’s wardrobe or behind the kitchenware, they would never share the secret to make sure the chocolate lasts longer. They were wise children…

There was also a lot of Armenian chocolate in the vase just beside the hidden jar. If chocolate had feelings, the Armenian one would be desperately heartbroken because it was considered nothing compared to the Russian one. It is not like Armenia did not have Alonushka or the animal looking chocolates or Rosher. Culturally, everything from Russia was considered to be a luxury, something more quality than everything else in Armenia. That is why Khanum and her siblings were always proud when going to school after the day their father came home.

December was a month of celebrations. Her father’s arrival always overlapped with New Year and Christmas celebrations, so even if the airplanes never landed from Russia, this period would still be a celebration. At least that is how Khanum thought at the time because her life was surrounded only by laughter and happiness then. She never asked questions and only enjoyed the gifts left by her pillow or under the Christmas tree from the Winter Grandfather.3 So did her younger siblings. If they were lucky that year, Winter Grandfather would get them whatever they asked for in their letter. If not, Winter Grandfather was so kind that even in those years that he was poor, he would still leave a bag of chocolates and fruits for the kids. Perhaps because a child’s heart was too keen on disappointment. Winter Grandfather wanted them to have a joyous childhood. Winter Grandfather was no one other than Azniv and Armen, whose wealth depended on how much Armen had earned in Russia or Azniv managed to save in Armenia.

Disappointing. So many lives depended and depend on Russia.

The logical continuation of the December celebrations was the setting of the Christmas tree. The Christmas tree they owned was huge. It was tall, almost reaching the sky, as Khanum remembered. It had beautiful ornaments in yellow, red, green, and blue. They even had some fancy ones: a Christmas tree ornament, a Winter Grandfather ornament, a snowflake, and even a star. The best thing about this tree was that it was the first thing their family bought and owned by themselves. It was an achievement, like buying a house, or a piece of land. For their family, that Christmas tree was a sign of their independence despite everything that had happened in their life. That Christmas tree still decorates their house. It has already been at least 15 years but neither the tree nor their family wants to let go of the memories.

That year, decorating the Christmas tree was extra special because their father agreed to take photos with the tree. The old-time serious father, who usually would prefer to be in the shadow despite his shiny personality and disliked being photographed, had agreed to take a silly photo, where two of the red ornaments were hanging from his ears. Quite an achievement for children with limited time with their father, not only because he would soon-enough leave for Russia, but also in a literal sense. Surprisingly, those silly photos became the last ones of the happy December.

Putting up the Christmas tree also marked the beginning of New Year Preparations. Every New Year seemed the same besides the fact that the Christmas tree became smaller and smaller with each year passing by. The New Year preparations for the female kids in the family were very smooth. Khanum does not really remember how she ended up writing to Winter Grandfather in the kitchen, instead of the living room. The worst is, she never understood why her brother was not sharing her faith in letter-writing with doughy hands. With the Christmas tree growing smaller, Khanum and her sister started sharing more responsibilities alongside her mother in cleaning and cooking. From December 27th to the 31st, Khanum, her mother, and her sister worked in the kitchen like ants preparing for the long winter. Many dishes and salads were made, many recipes were uncovered, and many failed. The kitchen used to smell like an actual restaurant kitchen and the cooks smelled like a mix of their dishes. The women in the house prepared for the New Year for four-five days in a row and no one dared to question why they were alone. Khanum does not recall when exactly she started asking her brother for help but one day the response was that “he is a man” and “men do not cook.” Khanum thought and went with the idea, burying the resentment in her heart because going against traditions far too rooted meant disappointing her family. As the oldest child, she could not endure that pain. They worked in the kitchen for hours, sometimes even forgetting to grab a bite. To add to the restaurant vibe, her brother or father would scream occasionally asking for coffee. Then another fight would flame in the kitchen between the sisters because none of them liked making coffee.

Meanwhile, her father would lie on the couch watching a movie and her brother would entertain himself with dangerous experiments that now shape his profession. This memory hurt Khanum deeply. She resented cooking and baking from those days onward, especially seeing not only her mother in horrible shape after those celebrations but also all the women she saw. Everyone was tired. Everyone had cooked for a whole week before the New Year to make sure they get enough rest and not cook for a few days afterward. This was a dream vacation for many women in her surroundings and she hated this. Everyone was in their righteous place at the time, wherever they were perceived to belong, were not they?

Many Christmas tree years later, the order in Khanum’s family started to change. 2008 was already in the past and even though airplanes were still a means to show longing, at least exchange rate boards in the banks were no longer a threat. Their family also managed to purchase the second thing they fully owned: a house, where the role division was challenged. However, the financial difficulties and the ambition to bring a better, stable future for his family cost Armen his life. The red ornaments stopped being earrings for him and Khanum and her family members stopped waiting for open doors or Russian chocolates.

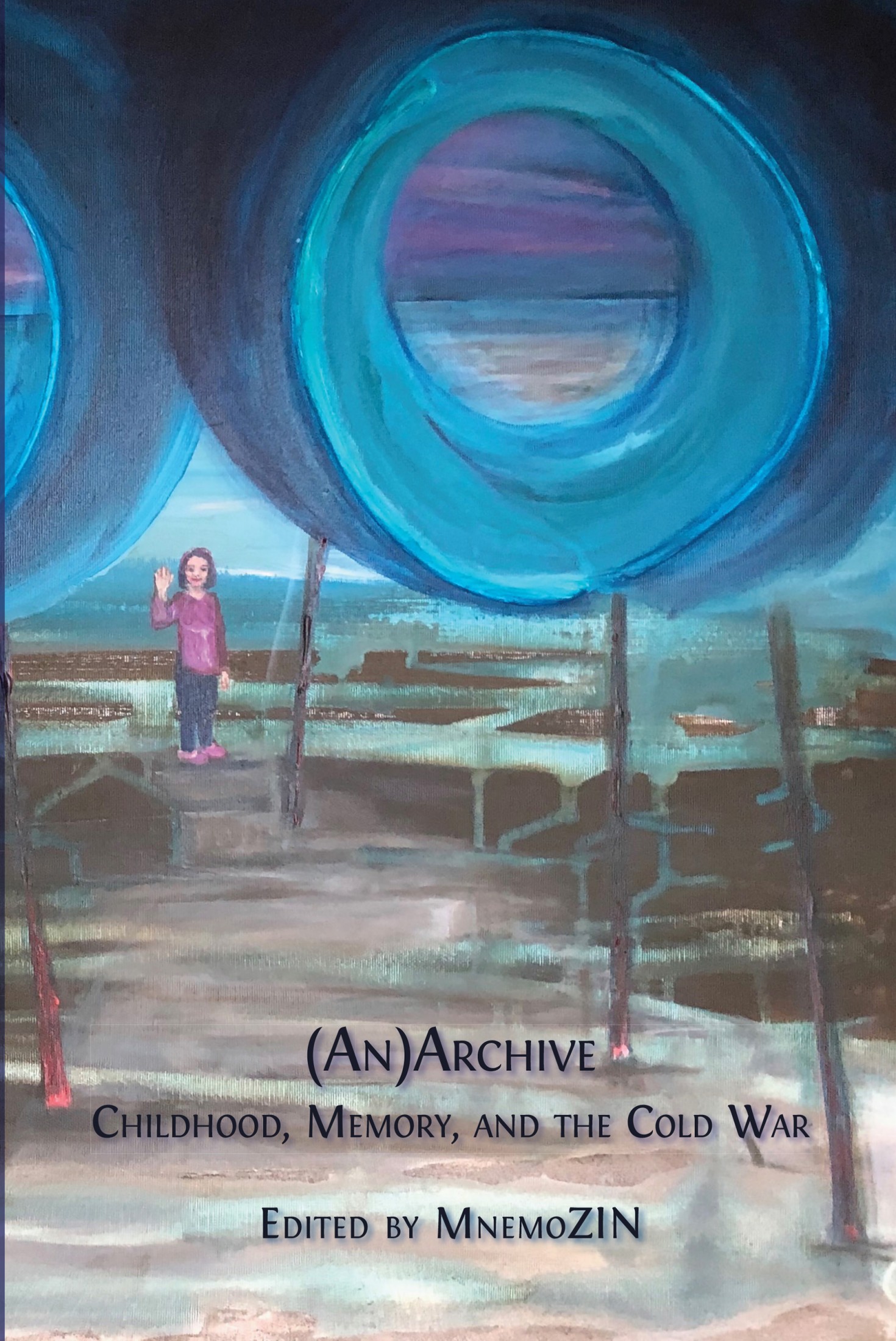

Photograph of the author and her father in a military uniform, n.d. From Khanum Gevorgyan’s family archive.

Holding a photo in her hand that brought back all these memories, Khanum remembered that she does not really remember. Memories fade away and the worst is, sometimes one is unable to distinguish between real memories and memories that our minds create to compensate for the time lost with a special someone. In this photo, where Khanum is sitting in her father’s lap, with his military beret on her head, she is way younger than she was in her memories. What is fascinating, Khanum bears no memories of this photo, because after spending days thinking about the photo and the time it was shot, she failed…failed to remember or perhaps the memory did not exist to remember.

Memories are not only pieces of recollections but also puzzles to understand the past and its consequences. In her book titled Remains of Socialism: Memory and the Futures of the Past in Post-socialist Hungary, Maya Nadkarni (2020) highlights the transformation of the notion of ‘nostalgia’. At one point in history, nostalgia named a physical illness experienced by those away from home, but, in the modern cultural understanding, the term describes not an individual’s pain but his or her longing for a past to which it is impossible to return (Nadkarni 2020, p. 106). Nadkarni believes that nostalgia is a result of loneliness and exile from the present and a yearning for a much more sensible, authentic, soulful past (ibid.). Nostalgia does not have to revolve around ‘virulent nationalism’, as Svetlana Boym calls it (cited in Nadkarni 2020, p. 106), the yearned-for past may still be individual. However, nostalgia related to memories of life within a particular socio-political situation may be shared by many. The details might not necessarily be the same, but the longing and the reasons for hate and love may overlap.

My home country’s socio-political situation mirrored itself in my childhood memories through which I could understand myself as a child of the ‘independence generation’.4 The events in the memories took place in December across the years from 1998–2014 and in various villages and the capital of Armenia. As the socio-political situation did not differ much in centralised Armenia, the settings in each memory have not been specified. In 1988, after Perestroika began, many Armenian revolutionaries and politicians started campaigning for the unification of Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh, a disputed region at the time populated with Armenians and Azerbaijanis. The Independence Movement of Armenia started with unification protests and demonstrations all around Armenia (De Wall 2003). The result of this was the Nagorno Karabakh (now the First NK) war. The combination of the 1988 Spitak Earthquake, which increased poverty and homelessness in Armenia and compounded the national anger and victimisation still felt in response to the 1915 Armenian Genocide (Steiner 2021), and the NK war coincided with the dissolution of the USSR. Armenia, now a post-Soviet country, was in chaos. I was born in 1998 when the war had been over for four years and Armenia was independent; however, the cost of the war, the consequences of the Spitak Earthquake, and the paused economic situation after the collapse of the Soviet Union did not ensure a worry-free life for any married couple in Armenia, my parents being one of them. Until age 14–15, I was quite unaware of the past and how much it had affected my present, including my family.

My father, Armen, was an NK war veteran and carried the psychological and physical pain of the war. As Jens Qvortrup highlights, children are not outside the zone of political influence even when politics are not directed specifically toward them (2008). ‘[M]uch of what happens to childhood, towards forming and transforming childhood and much of what influence childhood and their daily lives is in fact instigated, invented or simply taken place without having children and childhood in mind’, therefore, children become non-targeted, yet political objects (Qvortrup, 2008, p. 12). My siblings and I were non-targeted objects of politics. Neither the war nor politics—not even our family—was meant to direct our mindset towards one or another way, however, every lived experience shaped our fragile personalities. Despite our wish and anyone’s intent to pass on national pain and political emotion, we grew up with it and were very much influenced by it. The photo I mention in the last paragraph of my story, which I remember portraying my father in his military uniform and me, ended up being just a photo with no memories of it remaining. Nevertheless, it always brought back memories and awakened vengeance in me against Azerbaijan, the enemy country. As the oldest daughter of an NK war veteran, I always felt that hating is my responsibility, although no one ever told me so. The photo reminded me that, just like the beret in the photo, my father gifted me his legacy and I have to proudly keep it. I must, thus, avenge those who left such deep scars on my family and country. That was the general discourse in all childhoods, veteran or not. The burden was especially heavy on the boys. I can only imagine how children on the other side felt (feel). This shared political emotion also contributed to the romanticisation of the military, wars, and veterans. The financial challenges that my parents faced afterward were all negative results of the war. Despite the war being over, my childhood was still full of transferred war memories. Although vengeance has long left my heart, the actuality of memories inherited from my family and the memories I was unfortunate enough to create during the second NK war, in 2020, prevent me from being hopeful.

After the Spitak Earthquake, the collapse of the USSR, and the NK war and its aftermath, Armenia was not the safest country in which to live. Democracy was fragile and the blockade made living challenging. My father, who continued to work for the National Army, soon enough left his post and took the same road as many other Armenian fathers: he became a work migrant in Russia to be able to care for his family. Migrant workers were often known as ‘people who go to khopan’,5 and Russia had become the equivalent of khopan as many Armenians would choose Russia as their destiny (ILO, 2009). In my memories, my family’s financial difficulties were portrayed through the New Year and Christmas gifts that I would get from Winter Grandfather, which, sometimes would be nothing but fruits and candies as these were already purchased for New Year and did not require extra spending. At some point, my siblings and I started guessing the pattern of our gifts based on daily conversations that we heard from our parents and the amount of money we would save or the amount of work we would do on our house in later years. Soon enough, my childhood also became filled with adult worries, and I started carrying the worry of not being a burden.

The first year we bought the Christmas tree, it was nothing but a sign that there was hope that we may be able to catch up with the rest of our classmates and neighbours in having a brand-new Christmas tree. However, as time passed, the Christmas tree became more of an emotional symbol—a door to the longing for the past and the nostalgic feelings and the déjà vu that it gave every year during its decoration. As mentioned in the memory, that same Christmas tree is now fifteen (or perhaps more) years old, which may speak of two things: the sustainability of the household and the financial challenges that kept the Christmas tree the same for years despite its growing deterioration.

We had the tradition of saving chocolate and putting it on the New Year table to feel fancy. Despite the economic situation in the newly independent Armenia, many Armenians continued to aspire to the heights of development at the core of the USSR: Moscow. Anything from Moscow was a luxury. As Nadkarni mentions, ‘the Western standard of living became the benchmark of the “normal” through which the Hungarians developed consumer consciousness’ (2020, p. 108). The same happened in Armenia. Before consumer tastes in the country were westernised, they carried proud sentiments of their Soviet past, giving Russian products special treatment and looking at the local ones with prejudice. Many of my classmates, as mentioned in the memories, would have brand-new shoes, coats, and phones, and would bring chocolates to share with others. These products and this gesture were viewed as something fancy that not many could afford. That was how children romanticised the idea of khopan, despite knowing what it entailed, what their fathers had to go through. Continuing the consumer consciousness, the memories of the two chocolate jars—the Armenian and Russian—show how much was each valued through the eyes of children with no knowledge of political happenings.

My memories show how I resented gender inequality, even as a child. The clear role divisions put forward unhealthy expectations for both sexes to meet. As shared through the memories, my father was a migrant worker who left his family in the Spring and came back only in Winter for a few months. He worked for various construction companies in Russia, and the work was often physically punishing and, sometimes, exploitative. My father came back from Russia exhausted, in bad shape, and with little money that our family had to use to make ends meet. My mother could not contribute to the household income because my extended family did not consider it acceptable at the time for a woman to work outside the home. Although my mother had ambitions to work as a teacher, she was forced to become a housewife. This was the fate of many Armenian women and girls at the time who did not dare to question their situation. My father, as the sole financial provider of the family, could not afford to stay in Armenia.

As the memory tells, sometimes New Year preparations were very hard on women. While men had the opportunity to rest in Winter after working hard in the other seasons, women were never given the same chance. They worked the whole year, busy with housework, yardwork, the upbringing of their children, and other matters. New Year brought extra work: a whole week of just cooking and cleaning because the tradition was so. This was a shared social difficulty that many families carried. Gender inequality and role distribution very much depended on individual families. One family in the city-centre of Yerevan was conservative to the degree that its womenfolk were prohibited from leaving the house alone, while many families in villages did their best to ensure that both their male and female children received equal education. Therefore, I dare not say that women faced this social challenge only in villages or small towns. The worst thing about the gender inequality was the presumption that it would naturally continue, as when, for instance, my brother would rest while his sisters cooked. Gender roles are rooted in everyday life in Armenia. It is unfair for both men and women. Nevertheless, many people fight against this every day despite the challenges posed because of the latest war, the on-going skirmishes, and the lack of male soldiers in the country. There have been growing equality movements in Armenia and other social developments—both had an immediate effect on my childhood and youth. In 2006, when I was a first grader, a foundation, the Children of Armenia Fund, launched development programs in Armenia, beginning in the village of Karakert, where I was raised. Many other non-profit organisations joined them, offering hundreds of students an opportunity to explore the world outside their families and villages. Although my memories do not detail this transformation, this social and political change was at the core of Armenia as a former Soviet republic.

Thanks to this project, I was able to travel back in time and understand the reasons why my memories of these years feel so nostalgic. While feeling nostalgic about certain things is harmless, after analysing my own memories and understanding how unintentionally politicised my childhood was, I understand the importance a memory carries. Memories can work as puzzle pieces to reconstruct the past and at the same time an opportunity to review our actions and the way we build the presence of children nowadays and in the future.

References

De Waal, T. (2003). The Black Garden. New York University Press

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2009). Migration and Development: Armenia Country Study. Yereva, Armenia

Nadkarni, M. (2020). Remains of Socialism: Memory and the Futures of the Past in Postsocialist Hungary. Cornell University Press

Qvortrup, J. (2008). ‘Childhood and Politics’. Educare, 3, 6–19, https://ojs.mau.se/index.php/educare/article/view/1291

Steiner, P. (2021). Collective Trauma and the Armenian Genocide: Armenian, Turkish, and Azerbaijani Relations since 1839. Hart Publishing

1 This is a childhood memory produced as part of the Reconnect/Recollect project discussed in the introduction to this book.

2 ‘Kompot’(In Armenian: կոմպոտ)—homemade juice usually made in summer and kept till winter.

3 ‘Winter Grandfather’ (in Armenian: Ձմեռ Պապիկ ‘Dzmer Papik’)—an equivalent of Santa Claus in Armenian Christmas and New Year celebrations.

4 ‘Independence Generation’ is a term used to describe the generations coming after the fall of the USSR and the independence of Armenia. Children from 1994 onwards are a part of the independence generation because of the First Nagorno Karabakh War (1988–1994). See more: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/georgien/13149.pdf

5 Khopan (in Armenian: խոպան) is Armenian slang used to define people who leave Armenia for abroad to become cheap migrant workers. According to the ILO, Russia is the top host country for Armenian migrant workers (2009).