9. Creating and Sustaining the Care Information Utility–How, Where and by Whom?

© 2023 David Ingram, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0384.05

We come now to the most challenging questions concerning the care information utility: how, where and by whom will it be created and sustained, and under what governance arrangements? This chapter looks to the wider and future scene, to consider how the work described in Chapters Eight and Eight and a Half can be extended and sustained, in the context of greater opportunity and need for individual self-management of care and supportive services that move from a fragmenting culture of ‘What is the matter with you?’ to an integrative culture of ‘What matters to you?’ We must embrace an iterative and incremental approach here, where we learn by doing. The chapter is thus not prescriptive; it rather reflects on the nature of the challenges faced and what we should have in mind in framing our policy and practice in tackling them.

Central to this will be the approach and method adopted for implementation of a coherent and trusted information utility that every citizen can feel part of and contribute to, which helps and supports them along the way as they seek health and wellbeing in their own lives, and the lives of those they care for. The chapter highlights the importance of the Creative Commons and public domain governance that bridges with and preserves the non-exclusive relationship with private enterprise. The story of common land and its appropriation to private interests through the eighteenth-century Enclosure Acts in the UK, is visited as a parable of common ground in the Information Age. It discusses the harm that restriction of intellectual property does in blocking innovation that tackles intractable ‘wicked problems’, which require connection and collaboration on common ground, within diversely connected communities of practice.

The chapter then focuses on the work of implementing and sustaining the care information utility and the environments, teams and communities whereby it is enabled and supported. It looks at the different qualities of leadership that such pioneering endeavours require and exemplify, and playfully compares them with the principles outlined in The Art of War, the classic text of Sun Tzu, which is much used in elite management courses on leadership. With its focus on people and environments, this part of the chapter draws a great deal on people I have known and worked with, and environments we worked in and created together, and is thus especially personal and autobiographical.

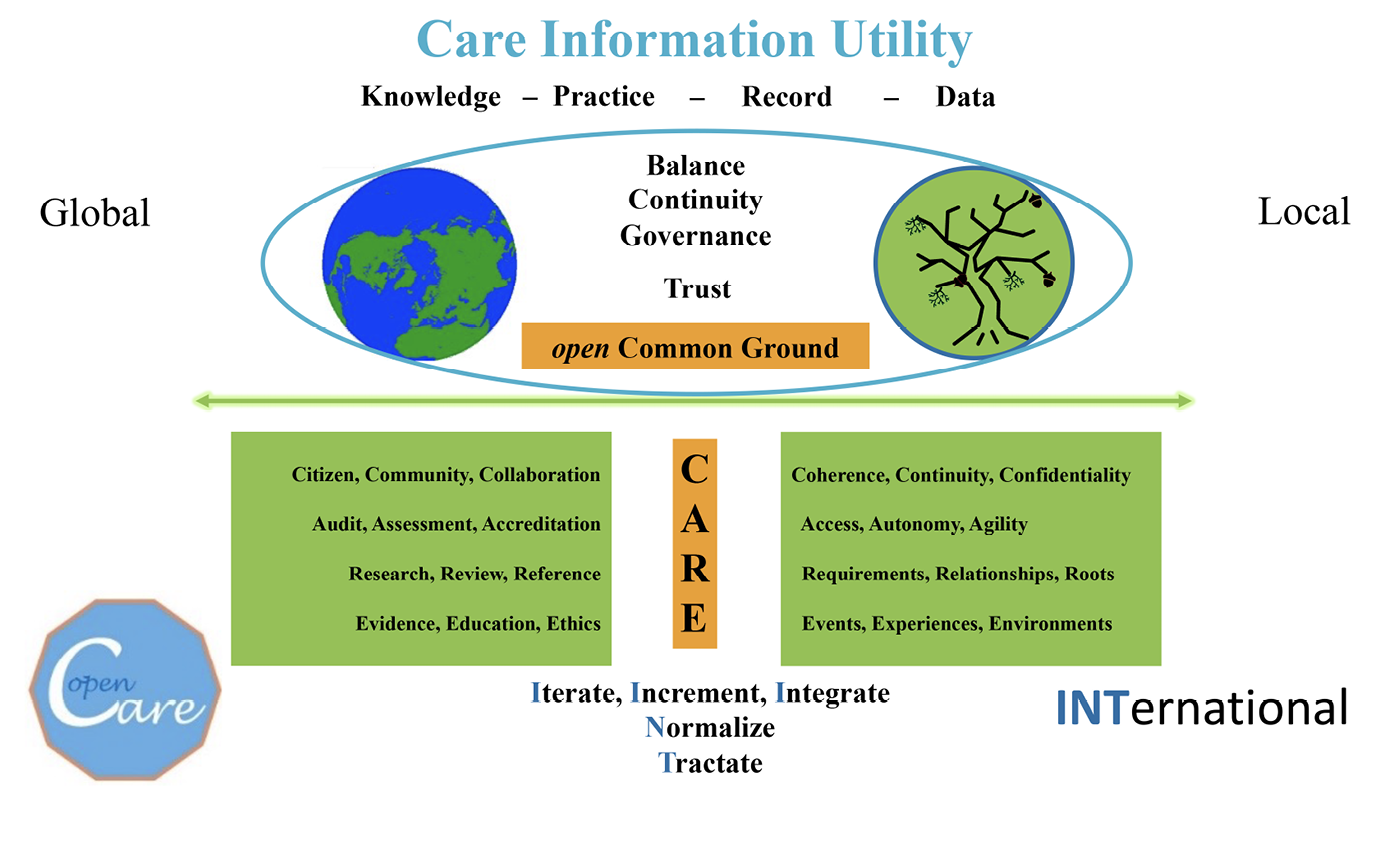

Trust in and recognition of individual and communal roles and responsibilities must unite citizens with the multiple professions and communities of health care practice, around shared goals for the care information utility. Governance arrangements will thus constitute a third major component of implementation of a utility that is coherent, effective, efficient, equitable, stable and life-enhancing, in support of health care services for the Information Society of tomorrow.

These threefold challenges of implementation will require strong alliances–the theme I reflect on, in parenthesis, at the end of the chapter.

Bolder adventure is needed–the adventure of ideas, and the advantage of practice conforming itself to ideas. The best service that ideas can render is gradually to lift into the mental poles the ideal of another type of perfection which becomes a programme for reform.

–Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947)1

When spontaneity is at its lowest, in practice negligible, the final trace of its operation is found in alternations backwards and forwards between alternate modes. This is the reason for the predominant importance of wave transmission in physical nature.

–Alfred North Whitehead2

I repeat this first quotation to re-emphasize that care information utility is an adventurous idea and a central focus in the reform and reinvention of health care. It is a shared resource, created, owned, operated and sustained locally. It is not a directed flow from a source to a recipient of information. It is a resource that faces and informs both ways. Governance and rules of the road must reflect this mutuality and be understood, trusted and supported accordingly.

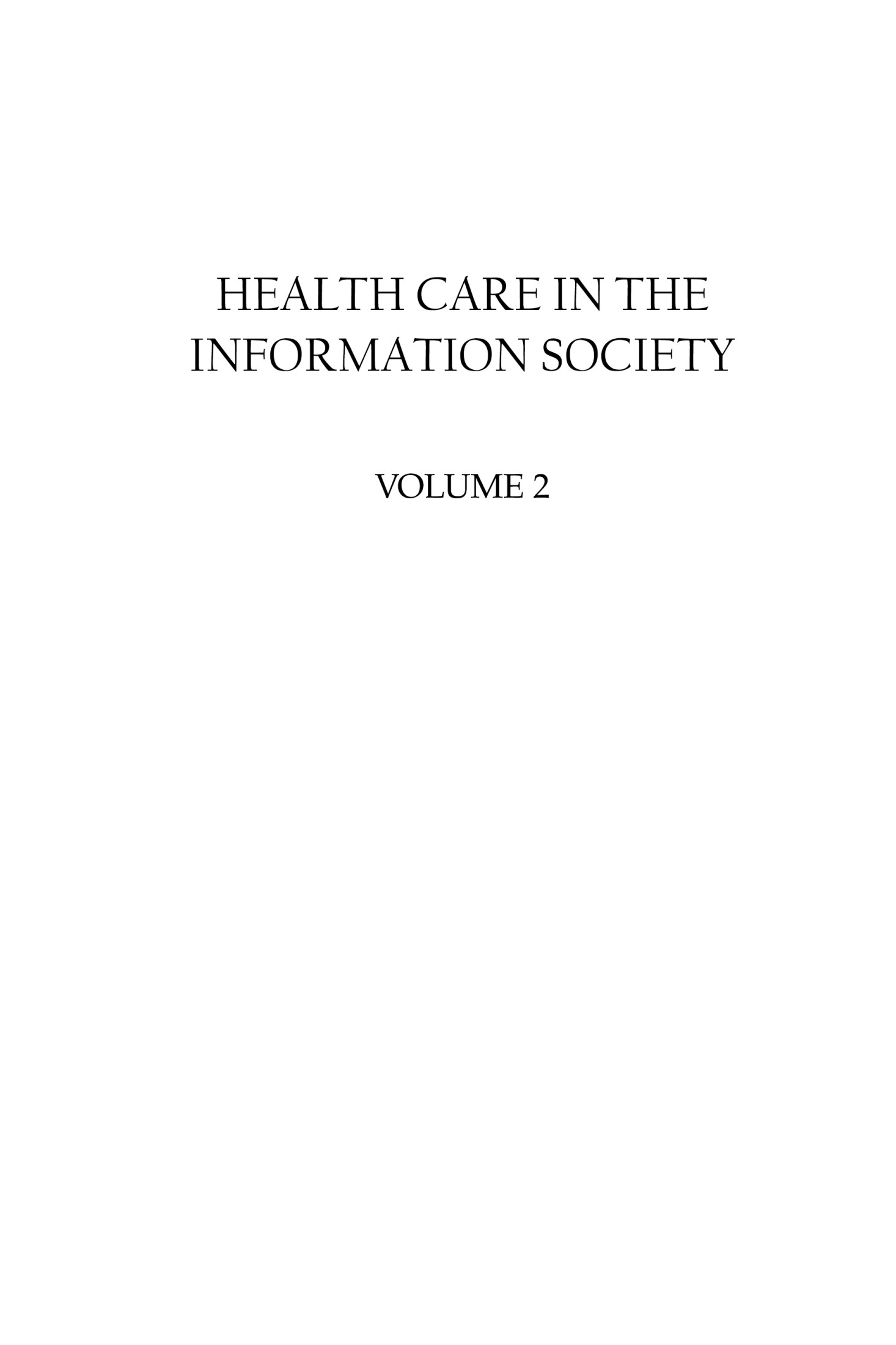

Chapter Eight has addressed questions of what is needed and why. This chapter connects them with the practical question of how. It is about the approach to and method of implementation, and the endeavour and governance that will be required to create, bring to fruition and sustain an evolving care information utility. At the centre of the utility is record, and at the centre of record is the individual citizen. How will this utility be created, based on what approach and method? How will it build on and supplant current fragmented legacy information systems? Why, what and how form a tripod of implementation that frames endeavours–they are about approach and method. They must be learned, not prescribed. I call this tripod Implementation One.

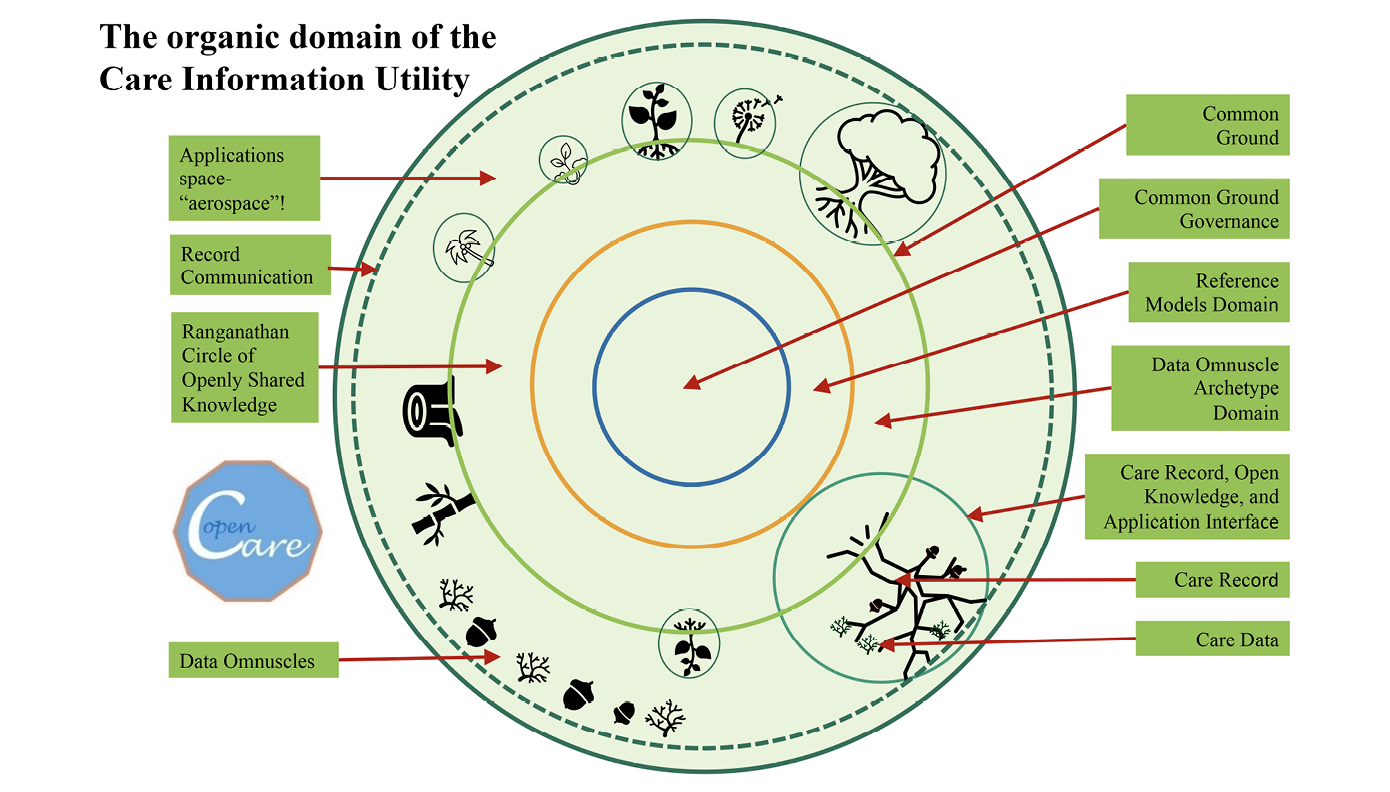

Where, who and when form a further tripod for endeavours. I call it Implementation Two. Where is about environment–the setting in which to tackle the creative and ongoing challenges. Who is about people–teamwork and leadership. When is continuously–the imperative is to keep moving upstream and sustain efforts through staying power. This chapter is thus also, crucially, about the people, teams and wider connected communities needed to co-create, own, operate and sustain the utility, the environments where they collaborate and the common ground they create, occupy and share. These are the good environments that Richard Wollheim (1923–2003) described as not a luxury but a necessity, that are needed for nurturing the utility from sapling tree into forest ecosystem.

Those first two tripods of implementation need a third to balance and stabilize approach, method and endeavour. This is the tripod of head, heart and hand of citizens and communities, expressed through systems of governance. I call it Implementation Three. Good governance, too, must be learned.

In my geometrically and visually configured mind, implementation is thus depicted as a triangle of the three complementary tripods of approach and method, endeavour and governance. It is enacted by people in settings and contexts, imbued by the culture and values they develop and exhibit in their work and behaviour. I have thus cast implementation as a triangle of tripods (implementation, implementation, implementation!) to emphasize its importance–a trifecta of complementary tripods! Making and doing these things, iteratively and incrementally, is all-important. And drawing everything together, at the apex of a tetrahedral implementation pyramid, is indivisible trust. Implementation comes together within a safe and trusted framework of making and doing. Figures 9.1 and 9.2 provide a pictorial representation of this esoteric geometry in my mind!

Fig. 9.1 Looking down from the red trust apex of the threefold implementation pyramid. Image created by David Ingram (2022), CC BY-NC.

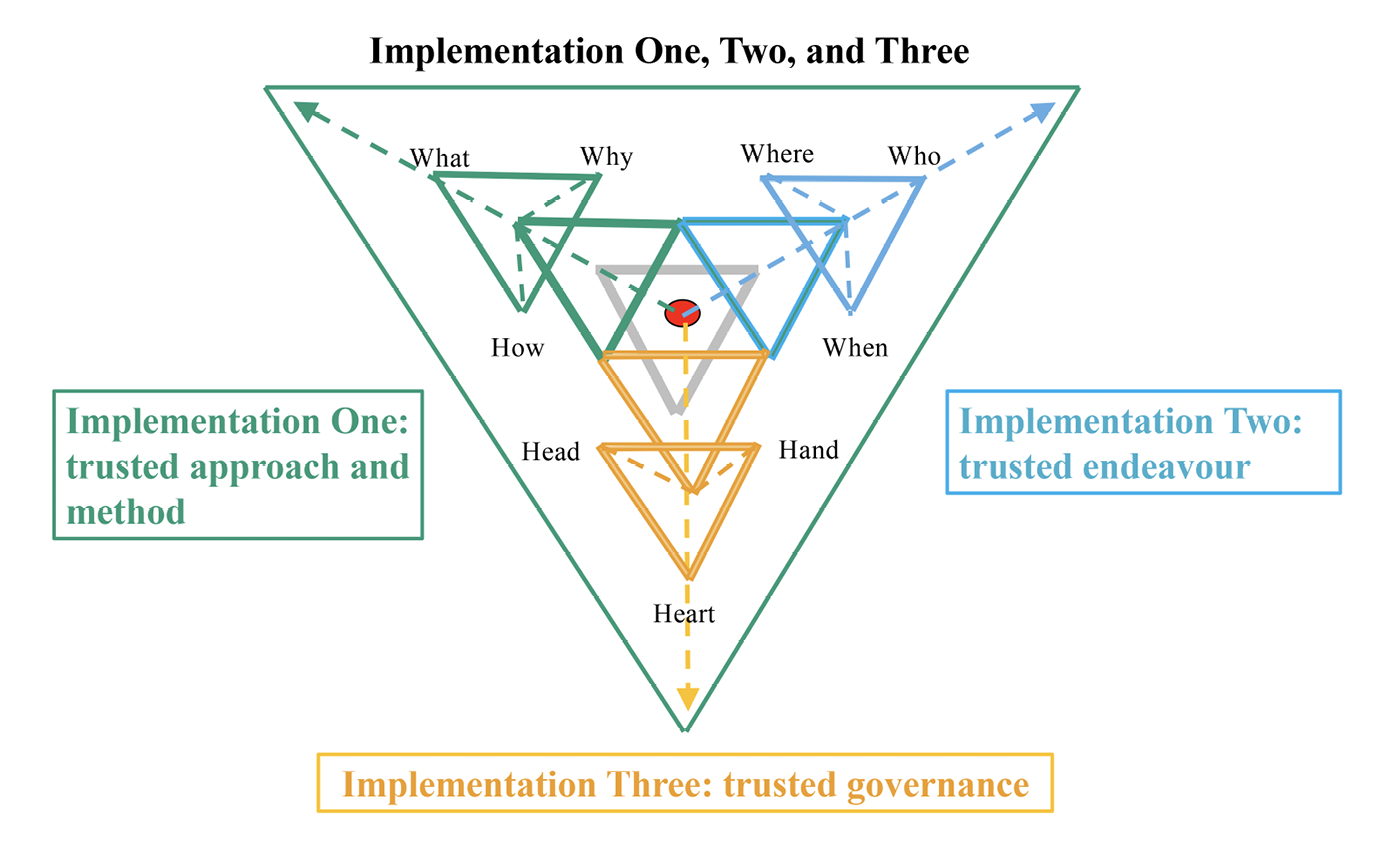

The Polish mathematician Wacław Sierpiński (1882–1969) was a pioneer of set and number theory and topology. His work has inspired model builders and artists. Images of the fractal decomposition of the Sierpiński tetrahedron have inspired my characterization and illustration of the threefold dimensions of implementation of the care information utility in this chapter.

Fig. 9.2 A fractal three-dimensional printed model of the Sierpiński tetrahedron–tetrahedron enfolded within tetrahedron, illustrating the fractal nature of implementations. Based on a design by Josef Prusa (2021), CC BY-NC, https://www.printables.com/en/model/67531-sierpinski-tetrahedron

Enough abstract geometrical analogy! Implementation cannot just be analyzed, planned and managed. It is organic and must be nurtured, grown, led, and sustained, and learned about through example.

We might similarly characterize three dimensions of reinvention and reform of health care services, as matters of approach and method, endeavour and governance. There is continuous interplay along and between these dimensions, that defies prescription and requires resilience to cope with events and adapt as they unfold uncertainly over time. This chapter draws from personal experience of this interplay along my songline, in several different contexts. It compares the ‘horses for courses’ observed and experienced, seeking to highlight patterns relevant for the future. Notwithstanding the pretence of electoral cycles and manifestos, none of this can ever be created with magic bullets or in rapid progress. Controlled nuclear fusion-based power stations have long been fifty years away, and care information utility is a still forming vision and long-term goal!

The quotations from Whitehead that headline this chapter, written a hundred years ago, are still to the point. In the first, he is suggesting that bolder adventure of ideas is needed to guide reform. This complements Mervyn King’s call for new ideas that are approached with audacious pessimism.3 He must have pondered that term–preferable to risk-averse pessimism or audacious optimism, which abound in uncertain times! The second quotation reflects the price we pay when lacking adventure of ideas, common purpose and energy in what we make and do–our actions oscillate to and fro, like waves in a water tank. The politics and policy of health care has oscillated between central and devolved focus, public and private provision and different models of delivery. Expensive reorganizations of associated services have gone through recurrent limit cycles of boom and bust.

King described the recurring crisis of the money and banking systems as a crisis of ideas. In banking, huge sums of money were spent on new information infrastructure and yet the instability of the monetary system persisted and worsened. The lack of ideas that King regretted was not about ways to spend money shoring up infrastructure. It was about lack of ideas for reform of the purposes, principles and goals underpinning the monetary system, as the global economy headed through the Information Age, with the computer exposing and amplifying its vulnerabilities. Care information utility is not about ways to spend money on infrastructure, either. Governments have spent very considerable amounts on computers and consultancy, mistakenly expecting thereby to change and shore up a fragmenting landscape of health care services.4

Some of these fragments have been prioritized and benefited hugely and function much better as a result–general practice IT systems in the UK being one good example. There have also been pre-eminent scientific, technological and clinical advances in imaging systems, genomics and pharmaceutics. Confidence in what artificial intelligence (AI) might contribute is both exploding and imploding, as I write–valiant AlphaFold meets its shifty alter ego, ChatGPT, as it were! Perhaps the Neocene will never be seen, or perhaps it will be us that no longer see. Implementation Three and confident governance resembles St George squaring up to this unpredictable dragon, hopefully equipped with effective armour and a sharp sword!

Leaving such speculative conjecture aside, in terms of what health care information systems could now be, with the individual citizen the central focus, the reality still falls far short of requirement and expectation. Ever more money spent in falling short, makes long-term reform ever harder. Confidence is at a low ebb.

Through the course of the preceding chapters, I have highlighted what I have seen and experienced as historic overemphasis of policy on what is needed and expected from health care information systems, and why, and lack of focus and critical examination of how its vision can be created, governed and sustained. Lacking a practical sense of how desired reform can occur and be sustained, the outcomes sought and invested in are not achieved, and undesired outcomes grow in their place. Implementation of policy has swung like a pendulum, between central fiat and local autonomy; it has been scattered and inconsistent in focus, oblivious to harm done in places struggling to cope and care. It is hard not to feel appalled by and ashamed of the cost, waste and harm it has engendered in many out of sight, out of date and increasingly decrepit environments in which our health care services, and their teams must operate.

Information policy is central to all the professions of health care and those they serve, the ways they work together and are organized, and the information systems and technologies they employ. Approaches to policy focused on prediction and management of goals and targets that have not often been met–as Chapter Seven addressed in detail–and pursued largely devoid of methods for achieving traction, have repeatedly failed to gain traction. This has made successive policy initiatives increasingly hard to implement, being increasingly encumbered and impeded by changing requirements, new science and technology, and a burgeoning legacy of incompatible information models and systems brought into being along the way. This failure has led to poorly contained explosion of noisy information–much as the Octo Barnett-led report to the Office of US Congress Technology Assessment Board feared and foretold, fifty years ago.5

All that said, Richard and Daniel Susskind counselled against what they called ‘technological myopia’, by which they meant the tendency to discount future potential of technology to assist and improve, by emphasizing too greatly its current perceived failings.6 Whitehead described mistakes and failure as normal parts of improvement and growth. All this is true, but simply repeating an ever more expensive and complex failure, revisiting the same ground that has characterized much of the past fifty Groundhog Years, is not acceptable. New ideas are needed, as is deeper and more openly shared reflection on the reasons for successive failures of policy and strategy, and failure to learn from experience, that have characterized policy in the field.

This chapter proposes how we might, and now can, bypass and progressively clean up the costly and accumulating legacy of unconnected and incompatible information systems, to create a care information utility that is much more cost-effective and better positioned along a sustainable pathway for the future, more in tune with the changing times, as we evolve into the Information Society. It proposes an effective, affordable and agile way to approach, create, replenish and sustain this utility, drawing on thirty years of personal experience and effort along the runway. This may, no doubt, be seen by some as a silly, unworldly and naively optimistic vision, perhaps also fearing that it is a destabilizing and threatening one. It has certainly been treated in those ways, but it is still alive and developing, as Chapter Eight and a Half has shown, after those many years of growing pains. I have taken heart from King and Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) in expressing it here. New ideas are needed, and we should not shrink from appearing or being cast as foolish in expressing our ideas, especially when we have real-life examples of these ideas being implemented and working coherently in practice and at scale, with connectivity and continuity that has eluded much, and far more expensively unsustainable, practice to date.

Implementation experiences of the architectural blueprints outlined in Chapter Eight and a Half are well advanced along new runways all over the world. And through dint of hard-won and multiprofessional team culture, practical industrial and organizational skill and effort, and staying power, these are amassing achievements that are helping shift the balance to a more open and inclusive way of thinking and acting. If these small efforts, many of the early ones substantially voluntary and unfunded, continue to bear fruit, they will have been very worthwhile. They have been, and probably will still be countered by giga-amounts of money and influence spent on powerful politically and commercially coordinated and focused efforts, with deep pockets and a mix of ambitions for enclosure and control of services and markets. At worst, if they ultimately fail, our now worldwide teams and community will have reset the dial for other communities to think differently and generate their own new ideas, that build and improve on what has been made and done to date. This will be useful learning to have documented, alongside that of the Broad System of Ordering and GALEN Project of Chapter Two. Great movements do fail–the Chartist movement, for example, with its story of community empowerment before universal suffrage. Samuel Smiles (1812–1904), my Chapter Five guide to the transforming power of innovation, as exemplified in the Industrial Revolution, was one of its champions. But, in failing, that movement also moved the dial.

In the parenthesis of Chapter Four, the topic reflected on was purpose. In Chapter Five, it was making and doing things differently. There is little point in having a purpose, unless pursued with commitment, and little point in setting a goal, unless accompanied by a realistic sense of how to achieve it. How, in practical terms, will the care information utility be created? How, likewise, will it work and be maintained and sustained? Implementation is about setting achievable goals and building the communities and environments needed for achieving them. It is about values and principles guiding the approach taken and method adopted, whereby success can be nurtured, and approach and method adapted, in context and over time, to remain focused on the purposes served.

Wicked problems of policy are real and the complexities and difficulties they present must be coped with, as much as predicted and managed. This coping centres on honest communication and competent listening, responsive to needs and recognizing limitations, and creating and building on common ground. It is very much a domain in need of what Gillian Tett, the anthropologist and financial journalist, described in her 2021 book, Anthro-Vision.7 She argues for a different AI–anthropology intelligence not artificial intelligence. She describes new attention being drawn globally to corporate governance focused around ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) principles of sustainability. This is seen as a modern-day imperative, when coping with the VUCA era (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) which has intensified through the Information Age.

This chapter suggests an audacious idea of care information utility, built on a tripod of co-created and shared intellectual property, community interest and enterprise, and an inclusive balance of global, national and local governance, drawn from these communities. As ever, in a spirit of ‘audacious pessimism’, this must prove its credentials, iteratively and incrementally, and be seen to be realistic, in actions and outcomes, not words. It must prove an agile and flexible approach, adaptable to changing context and need, as science, engineering, health and care, all experience, live through, learn from and emerge from the transition of the Information Age. It must accommodate new balances: of human head, hand and heart, with technology; of professional and personal roles and autonomy; of public and private enterprise; of global and local society and culture.

This is an open and inclusive perspective that seeks to help repair and reunite the prevailing fragmentation of sectors and professions of health care services, and of the organizations, communities and individuals they serve, and those that support them. The policy for several health economies well known to me–usually smaller ones, each serving no more than several million citizens–is aligning and further fostering creation of care information utility along this pathway. As I write, highly innovative tenders for openEHR-based community-wide health care information ecosystems have just been adjudicated for Catalunya, attracting considerable interest among policy makers in other places. Also as I write, a similar tender is being publicized by the Östergötland region of Sweden, potentially spreading more widely across the four or five principal health regions of the country.

I draw on several and disparate sources, in making the case for creating common ground and pursuing openness and collaboration in these endeavours. These reflect social, economic and political circumstances, and thinking that is not new. Such concerns have arisen in much the same way, both in history and in present-day deliberations about other major policy challenges. The first comes from the history of common land and its enclosure in early nineteenth-century England. The second from Karl Popper’s (1902–94) magnum opus of 1945, making his case for Open Society where creativity and democracy can thrive. The third from six thought leaders of today, illuminating themes of global crisis, social change and reform. Their perspectives (of economist, lawyer, financier, social historian and philosopher) align on the need for new thinking and new foundations of endeavour anchored in the Creative Commons of intellectual property. I also draw on the history of open-source software, supplementary to the discussion of the World Wide Web in Chapter Five.

I then circle back to the care information utility and where it should be pitched in the ecosystem of health care services, alongside the information systems of today. One goal must be to enable the still depended-upon legacy system functions to migrate safely, with the least disruption, into the new organic ecosystem that the information utility will nurture, incrementally, over time. In Chapter Eight and a Half, I described progress towards a central component of the utility, which bridges between knowledge, practice and community. This is the citizen-centred digital care record–its serial non-delivery being the fifty-year-old elephant in the room–perhaps not so old, for elephants!

So how can and should the care information utility be created, maintained and sustained? What is required for implementing and nudging change towards realization of a functioning information utility for health care?

Implementation One–Approach and Method–Learning and Showing How

Implementation is where we learn about wicked problems and how to tackle them. We learn how to do things by doing them–there is no other way. We must be engineers, keeping a close eye on what we are trying to achieve and aware of how the computer may be helping or hindering us in this.8

In science, theory and practice are grounded in hypothesis, experiment and evidence. Creation and innovation arise from left and right field–substantially independently from commentary and prediction. They proceed, like the steam engine, under their own steam and ahead of evidence. My anthropologist colleague in Centre for Health Informatics and Multiprofessional Education (CHIME) at the University College London (UCL), Paul Bate, specialized in the organizational development of health services. He emphasized the need to work from experience of practice into theory of practice, as well as vice-versa, with new ideas–the latter, the traditionally construed ‘bench to bedside’ paradigm of translational medicine. As discussed further, below, this has been called Ostrom’s Law–that is, ‘things that can work in practice, can work in theory as well’!

When formulating and implementing new ideas for tackling wicked problems, what seems often to engender success and sustainable impact is the way in which perceived needs and deficits are tackled. Bate highlighted this in his studies of health care innovations. The way we act can be as important as what we do. We should focus less on theory that predicts, or second-guesses, how the uncertain future emerging from Pandora’s box will play out. We can now predict the weather ahead more accurately and adjust accordingly. But even this knowledge remains couched with increasing uncertainty, the further ahead we look, in days and weeks.

Unfortunately, but inevitably in highly charged realms of politics, innovation as a focus for reinvention and reform is openly or covertly opposed, at times and places where it is most necessary for exposing and helping to clarify problems being faced. With wicked problems, it seems often to be required that anyone seeking a solution be able to demonstrate how to solve the problem before being helped and supported to discover how to do so. As the very wise former head of the Wellcome Trust advised me, thirty years ago, you cannot succeed with this kind of problem by talking and writing about it, you can only succeed by showing how. Until you succeed, no one wielding power will feel able to support you, and when you succeed, everyone will all always, secretly, have been your friend, she said, smiling encouragingly!

Such innovation is about creating and learning by making and doing. It is where head, hand and heart must align. It is mission, insight and alliance. It is not a place where money is easily, if at all, made, other than by the already wealthy, clever or lucky gamblers about the future. Some grab, pre-empt or gamble the future, and some opt out and manage, or prefer, just to gambol into it! Innovative mission is about staying power.

Politicians and civil servants have a hard job in presiding over dreamers, apparatchiks, gamblers and those who gambol. Managers must draw on evidence to focus and lead. But faced with complexity, reasonable concern for evidence can easily segue into treating ‘lack of evidence’ as ‘evidence of lack’. When there is a lack of evidence confirming something, it is often mistakenly treated as untrue. This is a cardinal error in clinical practice as well as a potential Achilles’ heel of ‘closed-world’ logic, as was discussed in Chapter Two. It may not do the health of the nation much good, either. We set standards that evidence must meet and use them as instruments for regulating innovation in areas not yet well-understood, but where there is pressure to frame and manage them, nonetheless. This is more defendable when managing well-established discipline, but of questionable value when charting the unknown. We need to create and experience futures before we can evaluate them sensibly with evidence. Disruptive futures are feared and shot down, for lack of evidence, before they can, or are allowed, to prove themselves. Remember the debunking of Charles Babbage (1791–1871) by George Airy (1801–81), as recounted in Chapter Five! Disruptive innovation was the focus of the economist Clayton Christensen (1952–2020).9

In Chapter Five and elsewhere in the book are numerous stories of obstruction of what ultimately proved successful and important insights and innovations, from centuries ago in the Industrial Revolution and in modern times–James Lighthill’s (1924–98) take-down of AI, for example. Funny from afar but not so funny up close, in similar machinations of the information revolution of today. Failure to marry necessary but inevitably disruptive innovation with enforcement of status quo often betokens hidden or unrecognized issues of understanding and capacity–what Whitehead and King saw as poverty of ideas and pretence of knowledge. King wanted more focus on narrative and storytelling, and my Chapter Eight and a Half tells a story.

Endeavour that sets out to create the care information utility will, inevitably, bring to the fore undecidable aspects of ‘wickedness’ in the problems addressed. Is human society capable of, and up for, the shouldering of the personal responsibilities that are entailed in realizing the personal expectations of health care services in the Information Society? Our expectations of and about other people in our community are easy to express and readily communicated widely in the Information Age–this is a distal connection. Our individual trust and participation in that community will depend on ways available to each of us, to help us feel part of and valued in achieving shared goals–this is a proximal connection. Enhanced distal connection and diminished proximal connection do not fit well together. Will the creation of the care information utility in Globalton10 community run aground, and rougher justice and injustice prevail in health care, by default? Zobaczymy [we will see]!11 The future will be created, one way or another.

There is no logical way to argue such matters of belief, one way or the other–we do not know the answer, or even if there is one, but we do have responsibility and opportunity to work for the creation of the future we want to see. Horses backed and decisions taken, and the outcomes they lead to, one way or another, will matter. These are new times and today’s answers do not lie in retrospective view. Stubborn and obsessed innovators and their innovations look forward and reveal paths ahead of us in the wood. Social movements start in threes and tens and rise to hundreds and tens of thousands. The statistician Lionel Penrose (1898–1972) proposed a square root law to characterize the power of social influence, after studying the voting behaviour of groups.12 I have found this insight helpful in thinking about the strategic growth of openEHR. In seeking to influence a group of people of size n, a cohesive sub-group numbering the square root of n can prevail. Ten committed and coordinated people can influence one hundred–in good and bad directions, of course! You can think of this another way–if you face a problem of scale n, first focus on a goal of scale square root of n–or root(root(n)) etc. to a scale that is tractable–and then work and seek to scale up from there.

The flip side of audacious hope is the resigned pessimism that can easily prevail in the face of the extent of wasted investment and opportunity that has been sunk in and now holds back progress. Much of the current legacy of health information technology (IT) systems is in a slow extinction phase, as indeed is that from much else of the historic investments to date in all IT systems. Globalizing monopolies are hoovering up some of the remains. I have seen and heard trusted reports of what lies under polished ‘car bonnets’, in too many places, not to know this. Many suppliers of systems know it, too, and are in survival or safe exit mode.13

We must not disregard or deny extinction events, including extinction of software technologies or patterns of health care; it is too costly. As with changing a house, there comes a point where modification is too costly and disruptive, and knocking down and starting again is the best and most cost-effective way forward to achieve the new house desired. The in-between stage is hard. We have neighbours two doors up from us, who, for eighteen months, have been creating a new house over the foundations of an old one–the family is living there as it metamorphoses. They have been caught by a delayed timescale, consequential on having started the building work just a couple of months before the Covid-19 virus struck! Shortage of materials, subsequent discovery of weak foundations, woodworm and more, have doubled the estimated construction time to eighteen months and still going. And they work from home and have teenage children! Other neighbours, at the end of the road, with four younger children, decamped to a fortuitously vacant close-by house while their builders moved in, ripped the house apart and rebuilt it. It has all been done in six months.

But we cannot move out of health care information systems and services while we rebuild them! We must work in situ, and this multiplies the complexity immensely. Bringing new imaging systems to a radiology department is almost straightforward, when contrasted with a project for creating and maintaining the integrity and continuity of part-paper, part-electronic health care records. These records cannot continue to be lost, in the ways that they have been multiple times during my career, due to organizations migrating them onto new systems that are not backwardly compatible. Data migration has been so complex that there has often been little choice but to throw up the hands and decide not to try. Data migration between systems lacking shared semantic and syntactic information models is a risky, noise-generating undertaking, if not intractable and unsafe. It makes no sense to continue to pile resources into pretending otherwise or believing new hype, that a new method can magically achieve it, where repeating history has indicated otherwise. This is a good example of one of the Susskind book’s short-term expedients that do long-term harm. Neither should we countenance placing all eggs in one or a few, monopolistic baskets–what one might provocatively describe as a ‘basket case’ strategy!

So, what of implementation of care information utility?

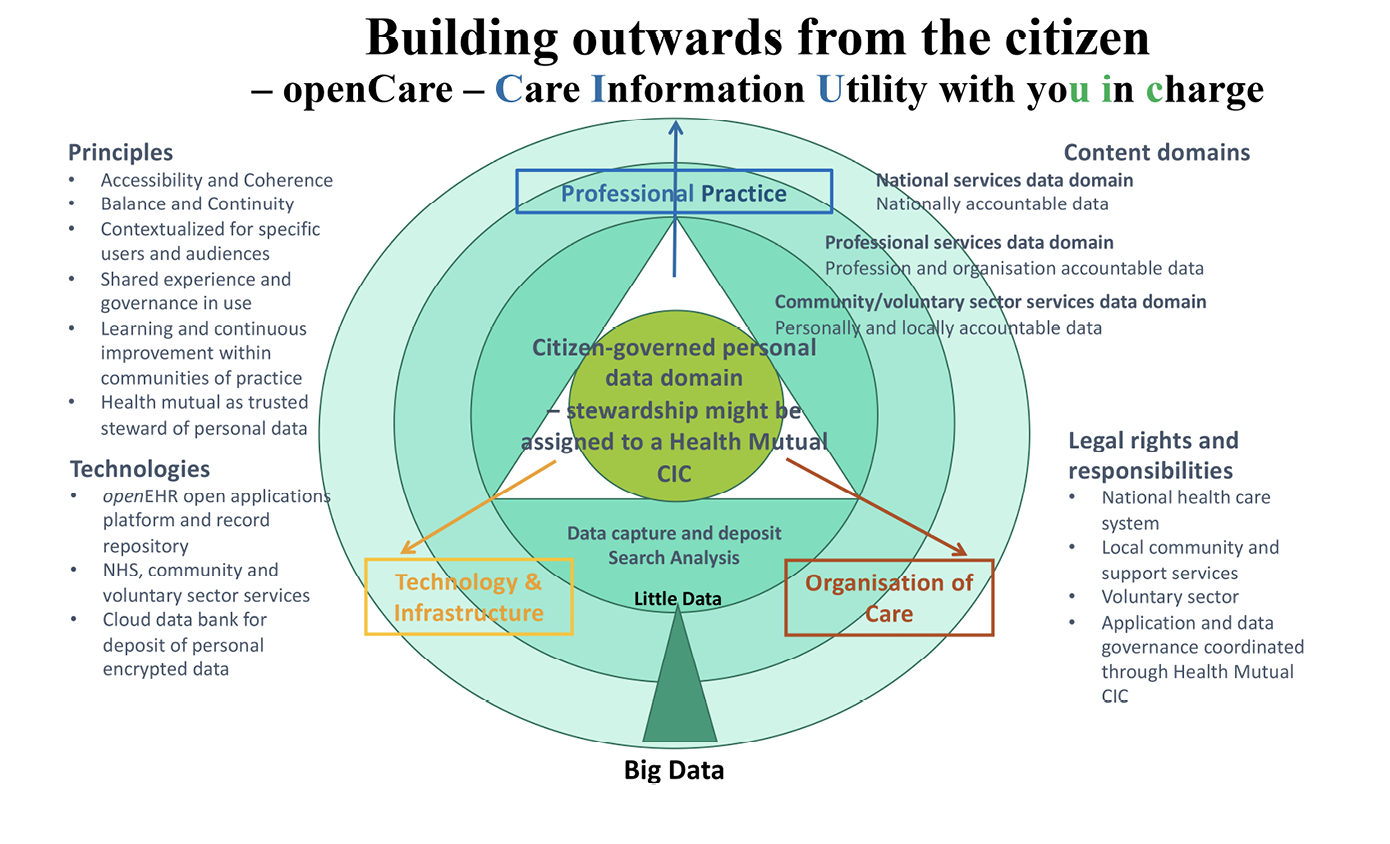

- Align under a simple monicker: A citizen-centred care information utility, perhaps called openCare;

- Tackle tractable goals in support of well-delineated groups of citizens and their supporting professionals, that integrate at home, in hospital and care settings, and on the move within and between countries, in their daily lives;

- Be clear about and pursue purpose and goal in improving the balance, continuity and governance of services;

- Focus on what matters to citizens in their health care services, and to the professionals who serve them;

- Focus on and engage carers and volunteers;

- Focus on services that bridge disciplines and professions across sectors of care;

- Focus on common ground;

- Think and act both locally and globally;

- Adopt an open platform;

- Build and support collaborative teams, environments and communities;

- Build iteratively and incrementally, in individually manageable and beneficial stages;

- Build in parallel and integrate;

- Prioritize Little Data and let the Big Data take care of itself. As Michelle Obama writes in her book The Light We Carry, we must go small before we can think big.14 We should focus on small and completable tasks–that is how we develop and grow.

Approach–the Culture of Care Information Utility

The approach proposed, here, is a natural and logical progression from the fifty-year halfway stage we have reached, as we now look forward to the next fifty years. In parallel with the opening of new vistas of prevention, detection, treatment and management of illness, the utility will reflect the greater capability and personal autonomy of the citizen in understanding and managing their personal health care needs, as an active participant who shares more fully in what is decided and what is done and is owner and sharer of their personal data. This contrasts with past approaches to information systems and their governance that have painted the subjects of care as passive actors, treated implicitly as a source of data to be harvested in pursuit of stuff that is done to and for them. We are at a bifurcation of paths forward in the use of information technology–one on a downhill and increasingly fragmented pathway, patching up inevitably always overburdened services, and one on an uphill and increasingly integrative pathway, building outwards from the individual citizen and their health care needs as a global villager, from their home.

This integrative goal is implicit in the image of the inverted triangles, based on Richard Smith’s landmark BMJ editorial of 1997 (see Figure 7.10) and depicting the transition from Industrial Age medicine to Information Age health care. In this perspective, services will focus and be based much closer to citizens at home. They will own their personal data and have greater personal autonomy and associated rights and responsibilities for taking care of their health. Services supporting them in these matters will focus more locally and around them. It has been a failure of vision of the intervening quarter century that too much attention has focused on advancing and shoring up struggling institutions and the data silos of fragmenting and overloaded Industrial Age medicine and social care, and too little on creating new, both real and virtual, environments for the delivery of health care services, in keeping with changing science and society.

This change of approach to care information systems will reflect and represent a transition of values and principles, extending throughout many communities of interest concerned with health and wellness in society. The lesson of experience of wicked problems like this is that it is impractical to orchestrate such a transition and inadvisable to leave matters to individual sectors or free markets to organize. It requires inclusive enablement of communities of interest, environments and endeavours. The multiplicity of potential connections embraced by such wide-ranging communities of interest is immense and realizing the vision can but be tackled collaboratively. There are many and diverse resources that the care information utility can draw on and contribute to. Again, incremental development and prioritization are inevitable. As with the Good European Health Record (GEHR) project described in Chapter Eight and a Half, the mission to imagine and create an architecture of this information utility is once more an iterative and experimental process that should be conducted in the public domain. What are the requirements and how can these be expressed in terms of an information architecture? This work is at the same early stage that I described in Chapter Eight and a Half, when writing about the workplan and drawing together of the GEHR project requirements. GEHR started from an existing prototype architecture and incremented from this in successive stages of modelling, implementation, testing and scaling. openCare can build from where openEHR has reached, and engage community-wide teams and organizations, aligned around shared goals, methods and governance. It can create and test prototypes and evolve iteratively and incrementally from there.

In tackling the wider integration of health and wellness services, the Nordic Countries stand out as pioneers in the formulation and implementation of their plans for the health and social care domain, with individual populations of Finland, Norway and Denmark, of around five million citizens, Sweden around ten million and the other smaller countries bringing the total to around twenty-eight million.15 The initiatives for Finland provide an instructive example, where the openEHR industry partner Tietoevry is playing a coordinating role in the creation of supporting information systems.

In 2022, the country has embarked on a complete reorientation of the organization of health care, social welfare and rescue services. In February 2022, presentations were given to a Nordic Countries meeting to consider collaboration in openEHR implementation. The aim of the proposed reform was to offer the population more equal access to services, to reduce disparities in health and wellbeing and restrain costs. In the IT dimension, focus was placed on service coordination, integrated health care and social welfare services and well-managed care paths, digital services and digitalization of processes. There will be considerable organizational transformation over the coming year, to create a national network of twenty-one Wellbeing Counties plus Helsinki and Åland, for organizing health care, social welfare and rescue services. Funding of the counties will principally be based on central government funding. This is a shift from services based on one hundred and sixty primary health care centres and twenty-one central hospitals, five of which are university hospitals; and from a previous configuration of two hundred and ninety social care units and twenty-two rescue departments managed by municipalities. Some two hundred thousand people will have a new employer.

This is not a scope as revolutionary as that implied by the Richard Smith diagram, but it is an important stepping-stone in that direction, tackling the re-integration of ‘health care and social welfare’ services, drawn together around a common methodology for standardizing care records. To my way of thinking about the implementation challenge of an information utility architecture that builds outwards from the citizen, there will be a requirement for wider integration with all manner of other products, activities and services that help promote individual wellness. Help in coping with and monitoring chronic disease; exercise and nutrition; social prescribing–for counselling and support of mental wellbeing, for example; personal advocacy and support services; citizen-based networks reporting on experience of, and coping with, disease. These all connect within the citizen’s purview of what is involved in keeping well and coping with illness. There is a huge network of home-based carers, hospice and other voluntary-sector support services, and local and national charities that contribute. Although not all within the scope of national government funding, they may attract large amounts of local government funding and public donations. This is where a locally framed and governed utility could be highly beneficial, by encouraging and facilitating local community ownership of needs and coordinating collaborative endeavours in concert with taxation-funded services.

I draw, below, on ideas gained in working for many years to support the StartHere charity, founded by Sarah Hamilton-Fairley and her husband Richard Crofton. This was inspirational and influential work, lauded and successful in multiple pilot projects, but ultimately not something that disparate community interests were prepared to risk their separate interests and identities to sustain. It lacked the care records dimension and my thoughts on integrating these under a common framework of global and local governance led to the conception of the care information utility I propose here.

All this will come to the fore in tackling health inequalities and shifting the focus of care onto a worldview of the citizen in need, not the organization providing services. It needs fresh thinking inclusive of this wider community of interest. It needs reinvention and redefinition of scope of service and articulation of requirements addressed. It needs new focus on wellness and the citizen at home. Citizen and service focus are complementary. We will need to overlay wider and complementary perspectives onto the ellipses of the GEHR requirements for comprehensiveness of care record architecture depicted in Chapter Eight and a Half (see Figure 8.21): wellness and illness; patient and professional; citizen and community; local and global standards and governance; citizen and academic science; computer science student and professional system developer.

At this point and time, as described at the beginning of Chapter Eight, we appear to be at a Robert Frost moment of choice between bifurcating pathways in the wood. Up-down and down-up paths beckon. Along the down-up route there must be vision and principle for connection of people, community, environment, architecture, design, resource, organization and governance. There must be a trusted and shared purpose and goal, forming the basis of cooperation. There must also be a process or roadmap that connects and creates from the here and now and its legacy, to a new and more sustainable future legacy. There must be incremental steps, and learning along the way, spreading out and integrating, horizontally across landscape of disciplines, professions, services and countries, and vertically within governance and government. As is being more widely spoken of, now, this is reinvention more than reform of health care. The care information utility will be one thread in the braid of that reinvention.

The technical dimensions of the reinvention will require authority within political, professional, commercial and institutional circles; the social dimensions will require authority within personal and community circles. Authority is not conferred–it is acquired. None of this can be mandated or imposed–it must be seeded, nurtured and helped to grow. There must be practical credibility, of head, hand and heart, throughout. These are the dimensions of the challenge for health care services to come through their anarchic Information Age transition, facing up to current fragmentation and inequitable unravelling of service, infrastructure, discipline and profession, and the need for their reinvention, reform and reassembly, supported by an inclusive, integrated and whole care information utility.

This rather ethereal vision of the implementation challenges posed by the utility is, admittedly, an abstract and symbolic one, and it sits alongside other symbols whereby people and communities gain strength and trust, to cope and cooperate. As Robert Axelrod wrote in The Evolution of Cooperation, based on his influential research in the early 1980s, trust is the foundation of human cooperation.16 Whitehead’s warning that I have quoted in the book’s Introduction, and again in the Postscript, also resonates–society must learn how to sustain its symbols or risk its own destruction by the anarchic forces of fundamental change. The Information Age is a transitional era of fundamental change in society. To borrow, and possibly misuse, a phrase from Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), ‘We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately’.17

The practical things needed to achieve the specific goals we set out towards creating the care information utility can all be made and done incrementally, over time. In development of human life, the embryo evolves a very long way towards wholeness, from single cell to body, before it is born into the world outside. Care information utility already has a living body, personality and community. It is directly relevant to the here and now of policy and practice for health care information. And crucially, it has examples that support and evidence it, and growing influence at a global scale: in Australia, Brazil. China, England, Finland, Germany, India, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, Portugal, Russia, Scotland, Slovenia, South Africa, South America, Spain, Sweden, Uruguay, Wales and many more, too extensive to list or possibly not yet known about.

When I first met Xudong Lu from Zhejiang University in China, while representing openEHR in Sao Paulo at the 2015 Medinfo world conference of Medical Informatics, he presented an astonishing paper about implementation of an openEHR-based health record system at his nearby two-thousand-bed hospital. He had built a team and created this system solely from the Creative Commons specifications of the openEHR architecture of electronic health records and the then existing, and now hugely more comprehensive and refined, body of clinically curated openEHR models of clinical data–the largest such repository in the world and in large part a product of cooperating professional volunteers, across disciplines, professions, organizations and industries.

And today, people all over the world can download and spin into life a functioning open-source OpenEyes ophthalmology record keeping system, the same as that now servicing approaching fifty percent of eye consultation records across the UK. And openEHR and OpenEyes are incrementally being harmonized, for national platforms of care record services, in whole national jurisdictions. The achievement of incremental goals, contributing towards the realization of Care Information Utility (CIU) is happening, now, North and South in the world. It started, as most seeds do, with a very small chance of success–it is now a 50:50. We are halfway there–the theme of the Postscript–echoes of Bon Jovi!

Having gone on at length about the importance of practical implementation, as is my wont, I now look back into history, as is also my wont, to the origins of two phrases–the Creative Commons and the Open Society.

The Commons

The word ‘common’ is semantically rich. It is the common land on which we can all walk, and maybe graze our horse. It is common sense, which is, paradoxically, both easy to talk and argue about and nigh-on impossible to define from an algorithmic and data-driven perspective, or have AI acquire! It is social and intellectual rank–House of Commons and House of Lords in the UK Parliament; scholars, exhibitioners and commoners in the archaic Oxbridge student parlance of my days there.

Common land was an interest of the historian Richard Tawney (1880–1962). After graduating from the University of Oxford in 1903, he and his friend William Beveridge (1879–1963) lived at Toynbee Hall, then the home of the recently formed Workers’ Educational Association. Tawney is a hero of the widely read and listened to Harvard University philosopher, Michael Sandel, who recently published his own critique of contemporary society, entitled Tyranny of Merit.18 In medieval England, there was a balance of land divided into strips, where villagers looked to their own needs for cultivation, and common land that was shared. This was an expression of the public and the personal, of owning and sharing. And in this environment, there was trust and continuity, independence and mutuality in life. This spirit is also expressed and illustrated today in the concept of Creative Commons. One must not get too starry eyed–there is always unfairness, poverty, criminality and exploitation, as well. But common ground was a valued and valuable resource. And in the Enclosure Acts of early nineteenth-century England, common land was enclosed and privatized, thereby destroying habitat, life and an enduring culture of community and countryside. John Clare (1793–1864) described ‘Enclosure like a Bonaparte let not a thing remain’.19 His poetry, nurtured in the rural idyll of his daily life, conveys sensitivity to the importance of this balance of personal and shared, private and public. He expressed this through everyday scenes and features of the landscape–an iconic elm tree–and the history and meaning they embodied.

Some have written of the ‘tragedy of the commons’, others of its ‘comedy’. In the tragedy, individual self-interest exploits the commons and triumphs over collective interest in sustaining and preserving it. In this scenario, as described by Garrett Hardin (1915–2003) in 1968, a group of shepherds graze sheep on common-land pasture; one shepherd places more than their equitable number of sheep, to their own benefit but to the disbenefit of their community of colleagues who keep to their quota. The value of the common pasture becomes impoverished for all, save for the miscreant, for whom default pays off. That is, until the members of the community, one by one, lose heart and the common pasture is no more. The ‘comedy of the commons’ describes how people contribute property and value accrues from its wider sharing. In the Information Age, what is contributed is knowledge and content–not for personal gain but for the good of the community. Examples often cited of this are free and open-source resources such as Wikipedia, and the many open-source projects made public through GitHub, parented by Microsoft, rather as UCL parented openEHR and the Apperta Foundation now parents OpenEyes.

The modern-day Creative Commons is an important and adventurous idea, being played out on common ground. Its legal foundations are tuned to different ways allowed for sharing and building on this common property, in balance with privately enclosed property. It is concerned with protecting and sustaining intellectual property for the common good, and preserving and sharing its value and meaning, for everyone. It is both lodestone and stepping-stone in the quest for social equity. Creative Commons is finding ways to protect and share intellectual property, that do not involve enclosure and defence against access. Lodestones are natural magnets; they naturally align to attract and cohere, and, otherwise aligned, they repel. Stepping-stones show a path across a stream. Thus it is with Creative Commons; we need to explore and understand the opportunities, polarities and forces in play, in shaping and sharing common ground, for the common good.

Common sense comes into play as much through perception of its absence in human thoughts and behaviours, as its presence. Maurits Escher (1898–1972) tackled the challenge of making sense and nonsense from incompatible, inconsistent or intractable ideas, in his collection of iconic lithograph designs, that I have pointed to in several parts of the book. To be valuable as common ground, there must be discipline in the intellectual commons, and a transparent and open balance of theory and practice. Where this balance is attempted on enclosed and opaque ground, it fosters division, exclusivity, inequality and extremity. Information Age infrastructure and services have evolved and migrated onto considerable mutual common ground, as I explore further later in the chapter. Next, I will briefly trace historical ideas about ‘openness’. This is a different trajectory, but the two come together in the context of future information utility.

The Open Society

The word ‘open’ is also semantically rich. Open, ajar and closed doors; open and closed minds; open and shut cases in law, where legal principle and precedent brook no argument as to the outcome; open sesame where anything goes. Open books are transparent–what lies inside is seen. Black boxes hide what lies inside. Black holes presented an information paradox–was information conserved or lost, and how? I gather that there are seven theories at least that seek to resolve this matter! Zobaczymy–or maybe we will not see!

It feels appropriate to mention Popper’s epic book, The Open Society.20 It is a heartfelt account, written while living in New Zealand. The country’s geographical isolation helped it to avoid the spread of world wars from Europe, in the decades in which Popper developed the philosophical ideas set out in the book. Popper went there as an exile from the Anschluss annexation of Austria, in 1938, and the book first appeared in 1945, the year of my birth. New Zealand was a relatively isolated enclave from Covid-19, avoiding the first waves of the pandemic.

The book is long (seven hundred and fifty-five pages) and outspoken. Maybe that is why Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) liked it so much! In my editions, Russell pips Popper in page count–eight hundred and forty-two pages of his History of Western Philosophy, but Popper out-pips Russell with rhetorical invective, decrying culture of deference and centralism leading to totalitarianism. Popper’s highly influential book is an often-florid expression and interpretation of culture, history and belief, born of powerful personal experience. He recognized this in prefacing a later edition, saying it had not been a time to mince words.

Popper had an affinity with Communism after the First World War but in time espoused liberal democracy. He railed against the mirror phenotypes of fascism and totalitarianism exhibited in his growing years. His analysis traced these cultural trends to pillars of Greek philosophy and onward into the twentieth century, sparking fiery debate and accusations of misunderstanding and misrepresentation. A bit like contemporary debates about ontology! His portrayal of the philosophy of Socrates (470 BCE–399 BCE), Plato (c. 428 BCE–348 BCE) and Aristotle (384 BCE–322 BCE) in support of his arguments was criticized, as was his critique of twentieth-century Marxist interpretations of history. He attracted warm support from radical philosophers of the time, such as Ernst Gombrich (1909–2001) and Gilbert Ryle (1900–76), as well as Russell.

Popper also railed against historicism–teleology in historical narrative–maintaining that history was influenced by growth in knowledge, which was inevitably unpredictable. His writings on conjecture and refutation became a key plank in the philosophy of science. I will leave the philosophical debate to others who know how to argue about such matters. My only reason for detouring through this history is to make a parallel with the meaning of ‘open’ in contemporary debate about Information Society, where information technology has become a stepping-stone on pathways both to enlightenment and to monopoly and extremism. The landscape of health care IT is an archaeological record, bestrewn with the remnants of ideas pursued with unsustainable methods, by unsuited and poorly led people, in the wrong place at the wrong time. We need a sense of what constitute open alternatives with better chances for success. A utility centred on proprietary knowledge and intellectual property, placed in control of citizens’ personal data, is most unlikely to prove a sustainable or acceptable model for a care information utility, although both public and private components assuredly will and should feature.

Threads in a Braid

Many threads are being woven together in discussions of major challenges the world faces at the outset of the twenty-first century. Braiding hair can help it to grow faster and provide a more stable structure. Unravelling of braids can lead to a tousled tangle. Transition in society is the disheveled unravelling of braids and the purposeful weaving of new ones. It is also the cycle of downswing and upswing in social cohesion, described by Robert Putnam in his 2020 book Upswing,21 and the similar optimism of Thomas Piketty in his equally magisterial 2022 book A Brief History of Equality.22 The six threads I describe, here, come under headings of economics of property, nature of professionalism, global community, global crisis, pendulum of change and social equality. They have profound implications for creation of care information utility.

Elinor Ostrom on the Economics of the Commons and Property Law

The Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom (1933–2012) challenged the assumptions about property that underpin economic theory, especially that which is held in the commons. She analyzed alternative ways of looking at examples of functioning common property, showing how they worked in practice and arguing that if they worked in practice, there must be a common theory to account for their success. This became known as Ostrom’s Law, which Lee Anne Fennell summarized as: ‘A resource arrangement that works in practice can work in theory’.23 I think of the development of openEHR and OpenEyes, with their emphasis on the primary importance of implementation experience, a bit like that!

We hear a great deal about intellectual property and its protection and appropriation for commercial benefit. We hear that the Amazon Company is valued at trillions of dollars while the Amazon rain forest is registered nowhere as a financial asset. For many house owners in South East England, personal property has for many years been accumulating more value in a year than is earned in full-time employment.

Richard and Daniel Susskind on Professional and Personal Sharing of Knowledge

In their book that I discussed in Chapter Eight, Richard and Daniel Susskind concluded that the societal contract–they called it a Grand Bargain–underpinning the relationship of trust between professional and citizen could only come into balance in the changing dynamic of the Internet age if communities and partnerships between communities shared their knowledge. In their seventh chapter, entitled ‘After the Professions’, they dissected the arguments both in favour of and in opposition to the idea of this operating as a Creative Commons, in terms of motivation, incentive, and sustainability. Citing the example of the success of Wikipedia, they highlighted that as a cost-free, supporter-funded initiative, it overcame problems of exclusivity.24 In their envisaged ecosystem, with the sharing of knowledge transacted and governed in the commons, they argued that a new, more equitable and beneficial professional relationship would emerge, trusted on all sides–a Wikipedia of professional practice.

They were not focused exclusively on the professions of health care, but their wider review of many professions provides a useful context for thinking about health care professionalism. It is a mistake to think along the lines often encountered, that because something is different, it is completely different. It seldom is, and such thinking says more about protectionism than the potential for collaboration around common purpose. Health and care have much common ground, with one another and with other professions.

Cass Sunstein on Aggregation of Knowledge and Markets, Deliberation of the Crowd and the Nudging of Behaviour

Cass Sunstein is a Harvard Law Professor who has made extensive studies of group dynamics in the Internet and social media age. In his 2006 book, Infotopia, and others of his works, he reflects on the many new contexts and communities in which we now accumulate and share knowledge and reach decisions, both individually and in groups debating with one another.25 The rise of the Internet has changed market mechanisms and Sunstein explores the new ways in which these can be predicted and gamed, and how they interact to cajole and persuade, through new forms of targeted advertising and manipulative manoeuvres that seek to influence and exploit behaviour.

He considers emerging Internet resources and tools, such as open-source software, wikis and Wikipedia, and revisits citizen rights in this context, settling around traditional areas of education, shelter and health, and with new focus on protection against monopolistic practices. He is concerned by the potential for the weakening of democracy through retreat into echo chambers of views and experiences that play out online, and isolated from direct human contact and ideas that might challenge their beliefs–a process called ‘cyberbalkanization’.

In 2021, Sunstein teamed up with Daniel Kahneman and Olivier Sibony, to publish Noise.26 This book draws on Kahneman’s ideas about behavioural economics, set out in his celebrated book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, showing how we are all influenced in our decision making.27 It presents a new and more forensic appraisal of how human judgements exhibit different kinds of noise and bias, including, for example, in sentencing practice of judges and clinical judgement of doctors.

Mark Carney on Global Crisis of Money, Climate and Pandemic

In December 2020, the annual BBC Reith Lectures were delivered over the Internet by King’s successor as Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney. Anticipating his new role as United Nations (UN) Coordinator of Policy on global climate change, he drew parallels from three crises of our age, and common problems of economics and society that run through them. These were the near collapse of the world monetary system in 2007–08, the escalating climate crisis and the 2020 viral pandemic. The lectures reminded me of John Houghton’s (1931–2020) much quoted remark, in relation to his time working on the UN International Panel on Climate Change initiative, decades ago, that humankind only takes issues seriously when in crisis.

Carney identified three areas of focus for change: engineering, politics and finance (new opportunity in innovation). His focus was on barriers to change, and he noted that the Gates Foundation emphasized the significance of speed and scale in their initiatives; policy must be driven quickly to scale, if it is to succeed.28 Agreeing a common approach and making it a reality should be as high a priority as dotting i’s and crossing t’s in selecting the particular policy to be implemented.29

In his lectures, Carney highlighted Cass Sunstein’s above discussed work on how social movements gain traction. He set out some principles of implementation of change, based on feedback and self-reinforcement cycles, with ‘values driving values’. Nothing succeeds like success, as it were. His emphasis was first on ‘reporting’, citing the maxim that what gets measured gets managed. His second focus was on risk management–all sectors must align around risk. His final emphasis was on what he called ‘returns’–making innovation for sustainability a business and making investors hold company policies and plans to account around specific values that their work embodied. This idea aligns closely with what Tett described in Anthro-Vision, as mentioned above, as the changing emphasis towards goals of sustainability which she had noted at the Davos conferences of world corporate leaders she had attended and reported on.

Carney’s take-home message in his Reith Lectures was the need to tie policy to what he called the leverage of social coalitions, with fairness, and income and welfare reflecting values. Again, this seems much in tune with Tett’s anthropological perspective, as well as with the ideas set out by Mariana Mazzucato in The Entrepreneurial State, when discussing reformulation of economic relationships in the world economy, in response to the crisis of VUCA.30 These ideas are much in keeping with the purpose and goals of care information utility, as proposed in this book. Carney’s central idea of values driving values is also descriptive of practitioner peer group review and reinforcement, on the ground. This bottom-up perspective and approach needs equal status alongside a managerial approach that takes a top-down view–both are seeking to ‘drive’ improvement of quality of services, and both are needed if a care information utility is to be created and sustained.

Robert Putnam on Upswing

As referred to several times in the context of previous chapters, this is a forensically researched and well-illustrated account of the half century or so ‘upswing’ of society from 1900 in the USA–from ‘I’ to ‘we’, as Putnam characterizes the era–with its emphasis on concern for the common good supplanting a culture of individualism and social divisiveness. The following half-century or so of ‘downswing’, from the 1960s onwards, he characterizes as ‘we’ back to ‘I’, with emphasis on assertion of individual rights and cumulative pressure on countering social and group norms that had come to frustrate individual freedoms. Putnam is four years older than me and has lived through downswing. His copious and wide-ranging socio-economic data analyses, notably including those on gender and race, are authoritative in tracking the century of American history, through which my parents lived, here in the UK.

Graph after graph of Putnam’s social and demographic analysis exhibits a similar inverted U-shaped curve of upswing and downswing over the century. One cannot help noting that the Information Age has emerged alongside these fifty years of downswing. Putnam does not connect the two, but it is tempting to postulate a causative and not purely associative relationship with the local social disconnects and global virtual connects of those times–one wonders!

In thinking of the prospects for the coming decades of the twenty-first century as we emerge towards the Information Society, with the experience of VUCA and related ESG priorities and calls for new focus, it is interesting to note Putnam’s optimism. He writes that the historical perspective laid out in the book leaves him more optimistic than he has ever been about the future trajectory of American society. Let us hope so–for other countries, too.

Thomas Piketty on Equality

As I completed my second draft of this book, around April 2022, Piketty’s Brief History of Equality appeared. It is itself a woven braid of decades of his treatises on the theme of equality in society, written in French and translated to English in this inspiring book. To do it justice briefly, here, is well beyond my ability, but I have collected a set of quotations from the introductory and concluding sections, where he sets out his stall. I have abbreviated them to exclude their particular contexts, simply to highlight their general relevance and connection to themes of this book.

From the book cover:

We need to resist historical amnesia and the temptations of cultural separatism and intellectual compartmentalization. At stake is the quality of life for billions of people. We know we can do better. The past shows us how. The future is up to us.

Regarding knowledge and learning, Picketty writes:

The process of collective learning about […] is often weakened by historical amnesia, intellectual nationalism, and the compartmentalization of knowledge. In order to continue the advance […], we must return to the lessons of history and transcend national and disciplinary borders.31

Regarding transition:

[…] economic and financial crises often serve as turning points where social conflicts are crystallised and power relationships are redefined.32

Regarding instability and iteration:

However, each of these arrangements, far from having reached a complete and consensual form, is connected with a precarious, unstable, and temporary compromise, in perpetual redefinition and emerging from specific social conflicts and mobilizations, interrupted bifurcations, and particular historical moments. They all suffer from multiple insufficiencies and must be constantly rethought, supplemented, and replaced by others.33

Regarding social and organizational change:

The social sciences naturally have a role to play in this, a significant role, but one that must not be exaggerated: the processes of social adaptation are the most important. This adaptation also involves collective organisations, whose forms themselves remain to be in reinvented.34

Regarding pitfalls between theory and practice:

Two symmetrical pitfalls must be avoided: one consists in neglecting the role of struggles and power relationships […]. The other consists, on the contrary, in sanctifying and neglecting the importance of political and institutional outcomes along with the role of ideas and ideologies in their elaboration. Resistance by elites is an ineluctable reality today, in a world in which transnational billionaires are richer than states.35

Regarding the process of reform:

Questions regarding the organisation of the welfare state, […] are both complex and technical and can be overcome only through a recourse to history, the diffusion of knowledge, deliberation, and confrontation among differing viewpoints.36

Regarding a balance of politics and ideas:

It is not always easy to find a balanced position between these two points: if we over emphasize power relationships and struggles, we can be accused of […] neglecting the question of ideas and content; conversely, by focusing attention on the [theoretical and programmatic weaknesses of ideas and content] we can be suspected of further weakening [them] and underestimating the dominant classes’ ability to resist and their short-sighted egoism (which is however often patent).37

Regarding the importance of an empowered citizenry:

[such] questions are too important to be left to a small class of specialists and managers. Citizens’ reappropriation of this knowledge is an essential stage in the transformation of […] relationships.38

And finally, in his conclusion, Picketty advocates for the reframing and reorganizing of common ground:

We must also describe precisely the transnational assemblies that would ideally be entrusted with global public goods and common policies […] Economic questions are too important to be left to others. Citizens’ reappropriation of this knowledge is an essential stage in the battle for equality.39

There is much of the culture and values of care information utility woven into Piketty’s vision, as extracted, and summarized here.

Co-Creation of Common Ground

This book is about the co-creation of common ground on which to base a care information utility, and discusses achievements to date as stepping-stones to that end. It is about what we grow there, and how we live and work there. The previous section drew together diverse perspectives on what implementation on common ground entails and how these complement one another. It is where those seeking to fulfil and achieve shared purposes and goals, combining diverse threads and methods of implementation, come together to complement, collaborate and co-create, thereby braiding and strengthening their endeavours. It is another organic analogy. Braiding occurs naturally in plants. The urgent new shoots of honeysuckle and wisteria outside my study window flail independently as they grow, seeking traction. They find one another, intertwine as a braid, and grow upward, stronger. In relation to the braiding of the many threads and methods of care information utility, in what contexts, according to what principles and governance, can they be created, extend to scale and be sustained?

In tackling grand challenges with wide-reaching impacts, from the local to the global, the balance and alliance of public and private sector endeavour is crucial. Where such alliance is scarce and balance questionable, their impact can be harmful. Reinvention of the balance and alliance of the two sectors requires new ideas, as Mazzucato has explored.40 For care information utility, these ideas must reflect and respect a shared common ground of values, principles, goals and methods. Fred Sanger (1918–2013) worked always in the public domain. James Black (1924–2010), John Vane (1927–2004) and Salvador Moncada, whose paths crossed with mine at various times, worked in partnerships of public and private endeavour. Great scientists such as these created, underpinned and led molecular biology and pharmaceutical science for several decades. Global money and industry organized, scaled, monetized and further developed its products and markets. In like manner, academic research created, underpinned and led methods for coping with large-scale unstructured data, and these foundations have been built on in the global tech companies of today.

Modern-day pharmaceutical industries have grown from intellectual property created and shared in academic and health care environments. Government, philanthropy, industrial partnership and individual voluntary and charitable endeavours have co-created and sustained those environments. AI, automation and robotics have been similar in provenance. No parties acting alone could have made this progress. Google and Facebook have grown from and traded on knowledge created on common ground, appropriated into private enclosure, aided by passive data volunteers. Wikipedia builds in the public domain, on the contributions of an active community of volunteers who offer their knowledge; it is a utility that can grow, enhance and share their knowledge and resource. In the Information Age, models of public interest have faced powerful competition with business models of enclosure. The Creative Commons is powering a reversal of that trend and enabling new and more open business models to prosper.

The word open has found a new niche in the Information Age–open-source software, open data, open knowledge–even openEHR and OpenEyes! Being ‘open’ does not in itself solve any wicked problem and it raises new problems of viability and governance of its own. As an expression of human aspiration and commitment, it is a bugle call and flag to rally under, about culture and practice of the Information Age. It is interesting that in the connected contexts of the previous section, several of the cited authors make connections with the advance of the open-source software movement, and with Wikipedia, as pioneering initiatives in creating common ground.

Open-source Software

A good starting point, here, is the story of Unix. Quite early along my software songline, I became aware that manufacturers’ operating systems for their computers were an eclectic mix, difficult to get to grips with and work with, and consuming a good deal of time, effort and resource on the part of their users. And this was ephemeral knowhow–one got better at it as one tackled essentially the same challenges for successive machines that one used. But it tended to ensconce tribal loyalty to particular manufacturers and their ways of doing things, as the devil one knew. People built their careers around International Business Machines (IBM), Honeywell, International Computers and Tabulators (ICT), Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Data General, Hewlett-Packard… and so on.

The idea of the AT&T Unix operating system emerged in the Bell Labs research centre. It was to be portable across different computers and provide a common programmer and user experience of a multitasking, multiuser operating system. Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie were its originators at Bell Labs, and the system was licensed from there, not originally as open source (i.e., providing all the code to its users), but addressing many of the needs for a common research computing environment. It spread under its own momentum across the world. From this beginning in the 1970s, arose a Unix family of implementations on different machines.

In 1991, the Finnish Computer Scientist Linus Torvalds published the first version of an open-source Unix-like operating system, which was named Linux–a bit of Linus and a bit of Unix! The license chosen was a cautious one, to preclude downstream meddling that might corrupt the free dissemination and functional integrity of the standard version. Torvalds was and remains the Fred Brooks style of architect–in charge, capable and motivated. New business models emerged for companies providing installation, training and consultancy services based on Linux, which remained free to download and unrestricted in use.

In the following decade, the Android open-source project drew together a community of developers to create an operating system that spanned smartphones and notepads. From 2005, it was taken in and run by Google, which set and maintained a high standard for cost and performance, with the software freely downloadable under the liberally permissive Apache 2 open-source license. The viability of this software ecosystem depends on Android remaining state of the art, such that there is no functional or cost incentive for forked versions of the code to emerge, although these are technically permitted under the license. Google, itself, mixes proprietary code with Android open-source code in its own products, presumably to maintain some exclusivity. Other suppliers can do likewise.