1. Socio-Spatial Practices of a Community Living Beneath the Land in Beni Zelten, South-Eastern Tunisia

©2024 Houda Driss, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.01

Introduction

Architectural heritage is characterised by its physical and material features, which attract interest in the study of the intrinsic properties of the built framework. The study of space from a similar point of view allows us to understand the logic of its insertion in the urban context, to identify its geometrical characteristics and to define its materials and construction techniques. However, studying architectural heritage solely in terms of its physical materiality removes it from its content and meanings. The function of inhabited space is not limited to sheltering the human body and protecting it from external agents, but rather, over time, it acquires another abstract and immaterial dimension.

This chapter focuses on the study of socio-spatial practices in vertical troglodytic dwellings located in the village of Beni Zelten in south-eastern Tunisia, which constitute an important part of the region’s intangible heritage. According to the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), ‘Social practices, rituals and festive events are habitual activities that structure the lives of communities and groups and that are shared by and relevant to many of their members.1 In this chapter, the author will identify and explore the spaces in which these practices, rituals and events took place and their significance to the community.

The first part of this study identifies the spaces belonging to these dwellings and the relationships that exist between the different spaces, using the methodologies of literature review, in situ observation (particularly the architectural survey technique) and other investigative methods. The second part consists of enumerating and analysing the activities practised in the studied dwellings through a historical and investigative approach which relies on direct interviews with several elderly individuals (women and men) native to and resident in the region. In the course of these interviews, the interviewees discussed the socio-spatial domestic practices of their ancestors. The collected data was then processed and classified according to the interlocutor’s gender, degree of privacy and the frequency of specific activities (daily or occasional).

Spatial organisation of vertical troglodytic dwellings

The village of Beni Zelten is located in the Governorate of Gabès in south-east Tunisia. It was inhabited by Arabised Berbers who led a semi-nomadic lifestyle and were active in the agro-pastoral and artisanal sectors. Troglodytic architecture, which is characteristic of the architecture in the village, refers to habitable spaces that are dug out of geological formations. Trebbi and Bertholon add that it is ‘an architecture in negative˝, dug in a mass, which favours the interior space obtained by subtraction of material.2 They can be considered subterranean dwellings, which Golany defines as ‘Structures located deep within the ground. The depth may vary. The soil cover functions not only as an insulator but also and primarily as a heat retainer. The subterranean system is usually found in a hot/dry climate’.3

The vertical troglodytic dwellings are occupied by extended families consisting of a father, mother and married male descendants. In this conservative and patriarchal society, the members of an extended family share the agricultural harvest and the available resources, under the predominant authority of the father. The houses are imperceptible at first glance. Only the patios, large circular or square holes dug at the top of the small hills, testify to the presence of an underground human settlement.

The dwellings are accessible through an entrance vestibule, which preserves the privacy of the inhabitants by shielding them from public view. Located on both sides of the access corridor (also underground) are barn(s) and storage area(s) for agricultural equipment. The vestibule leads to the patio, usually on the west side.

The open-air patio is the only source of air and light in the home. Its dimensions vary between six to ten metres in depth and five to ten metres in width. The depth of this central courtyard depends on the number of floors in the house. If the house has one or more granaries on the first floor, then greater depth is needed. The uncovered patio is sufficiently lit and airy, just as it would be in a dwelling built above ground. This patio is the site of various daily and occasional activities, especially those conducted by women, such as preparing meals, grinding grains, drying fruits and vegetables and laundry, etc. This central courtyard also allows passage between the different spaces—namely, the bedrooms, kitchen(s) and granary/-ies.

The houses have several rooms and no windows. They range from three to four metres wide and two to two-and-a-half metres high, and they have varying depths of four to eight metres. The roofs of these underground spaces are never flat. Rather, they take the form of a raised arch, a parabolic vault or a triangular shape. These are rigid structures. This configuration allows the distribution and transmission of load without the risk of collapse.

The rooms have multiple uses. The area closest to the door can house a loom and be furnished as a living room and a sleeping area for children. However, the deepest, most intimate space is reserved for the couple. The back wall of some rooms has a small excavation that serves as an ablution space, often containing a shower. It is used exclusively to wash the body and never as a toilet. As André Louis observes, ‘It should be noted that the troglodyte house does not have toilet facilities.4 Toilets, considered impure, are not integrated into the dwelling. Instead, according to oral tradition, men go away from homes to perform these natural functions in the wild, whereas women make use of small, discreet excavations that are arranged outside the dwelling.

The cooking space may be a shallow excavation located on one of the walls of the patio. Alternatively, it can be a space bounded by a wall occupying a corner of the courtyard and covered by some tree branches. In the same dwelling, one can find up to four cooking spaces if the family inhabiting it is very large. The cooking spaces can be located to the right or left of the entrance vestibule opening on the patio and can occupy any position between two rooms.

The granary is a space used for storing olives. It opens onto the central courtyard, but it is raised a half or whole level above the patio floor. From the inside, it is accessible by carved notches or pieces of olive wood embedded in the wall, which function as a staircase. The granary occupies an elevated position compared with the other spaces that open onto the central courtyard, for two reasons. The first is to protect the contents of this space from thieves by making access difficult. The second relates to the symbolism of this space, which reflects the esteem and wealth of a family. The roof is equipped with a pipe that allows olives to be transferred into the granary from the outside without crossing the courtyard. According to Libaud, to fill the granary, ‘the owner will only have to drive his camel on the hill (which is now the roof of the house) to the pipe and unload the olives directly from the outside.5

As the description above makes clear, vertical cave dwellings are not directly accessible. The organisation of the housing layout is not arbitrary; rather, the nature of spaces and the relationships between them are dictated by well-defined social laws and cultural codes. As Pierre Robert Baduel explains,

To produce a habitat, is first of all to develop societal relations, to organize proximities and distances, to draw boundaries between an inside and an outside. [… The] inhabited space is therefore oriented, and oriented specifically according to the reference culture.6

Privacy is only one such cultural concern that informs the layout of the troglodytic structures. The studied houses have two sets of spaces. The first contains the rooms, cooking spaces and granaries. The second consists of the service spaces (vestibule, barns and agricultural equipment depots), which are relatively far from the living spaces. This arrangement is a matter of health and hygiene, as it distances occupants from their animals. All the components of the house are part of the same enclosed perimeter because of the lack of security and the conflicts that have prevailed in this territory. As Eleb and Chatelet note, ‘the division of the ground, as well as the distribution of the rooms of the dwelling qualify both the lifestyle […] and the relationships between people.7

Socio-spatial practices in vertical troglodytic dwellings

Record of activities in vertical troglodytic dwellings

To understand the socio-spatial practices in vertical troglodytic dwellings, first we must collect information about how the local population used the different domestic spaces. The second task is to process the collected data to understand the different scenes of life in these underground spaces, by referencing the existing literature on the one hand and utilising investigative methodology on the other. Based on the inhabitants’ speech, this study identified thirty-six domestic activities.

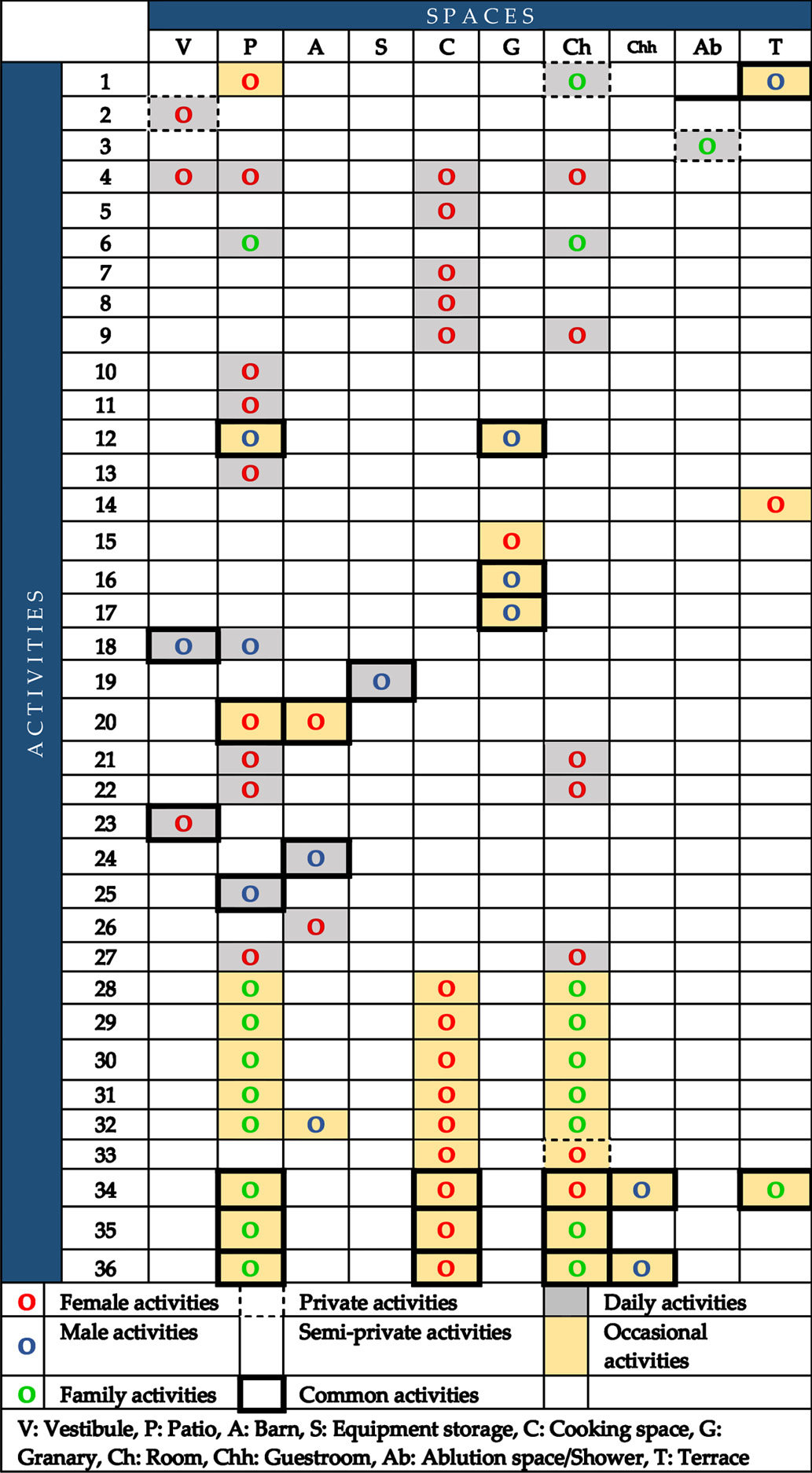

The activities are classified according to the gender of the user and the activities’ periodicity. Female activities are performed only by women, whereas male activities are performed only by men. Family activities are carried out by all family members (women and men). The second classification shows that daily activities are performed frequently throughout the year. While occasional activities take place in an irregular and seasonal manner, they have a religious, para-religious and ceremonial nature. Table 1.1 allows for the comparison of the data of the two established classifications.

Table 1.1 shows occasional activities, including those carried out by women, men and the entire family. For example, on the day of Eid al-Adha, men slaughter sheep and women clean and grill offal as they prepare couscous with lamb meat. Then, the whole family partakes in the meal.

Table 1.1 Classification of activities according to type and frequency.

The different activities can be further classified according to the degree of privacy of the space. The study first distinguishes private activities performed by a small family (a couple and their children) within a room. It then identifies semi-private activities carried out by members of the extended family (all occupants of the dwelling: grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, etc.). Finally, it indicates the common activities carried out publicly, in the presence of guests and neighbours. This classification is presented in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Classification of activities according to the degree of privacy (private, semi-private, common).

Identifying activities in spaces

The obtained data on activity types (female, male and family), degree of privacy (private, semi-private and common), periodicity (daily or occasional) and the different spaces contribute to a better understanding of socio-spatial practices in studied homes.

Table 1.3 Identification of activities in spaces.

In Table 1.3, each line represents an activity. The columns indicate the different spaces in the dwelling. The observed activity is marked by a circle in the corresponding box. The three circle colours correspond to the following significations:

To indicate the periodicity of the activity, the boxes relating to daily activities are shaded in light grey and the occasional activities are shown in salmon colour. The degree of privacy is expressed by the boxes with dashed lines for private activities, fine lines for semi-private activities and bold lines for common activities.

Classification of spaces by number of activities

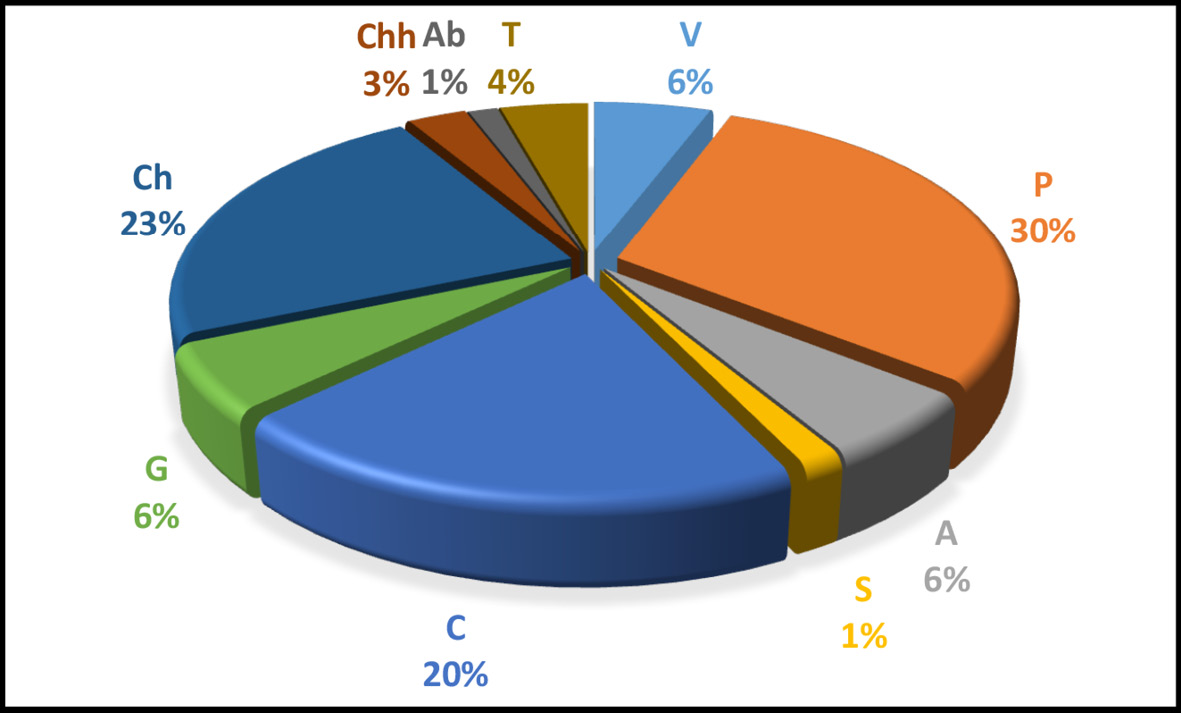

Based upon the information in the preceding tables, Figure 1 shows the percentage of the use of each space in vertical troglodytic dwellings.

This graph shows that the patio has the highest number of activities at 30%. Rooms and cooking spaces occupy the second rank, with a percentage close to 20% each. The other spaces are sparsely used and have rates below 6%.

Fig. 1.1 Percentage of use of each space in vertical troglodytic dwellings (V: Vestibule, P: Patio, A: Barn, S: Equipment storage, C: Cooking space, G: Granary, Ch: Room, Chh: Guest room, Ab: Ablution space/Shower, T: Terrace).

Author’s graph, CC BY-NC-ND.

Spatial characteristics according to female, male and family practices

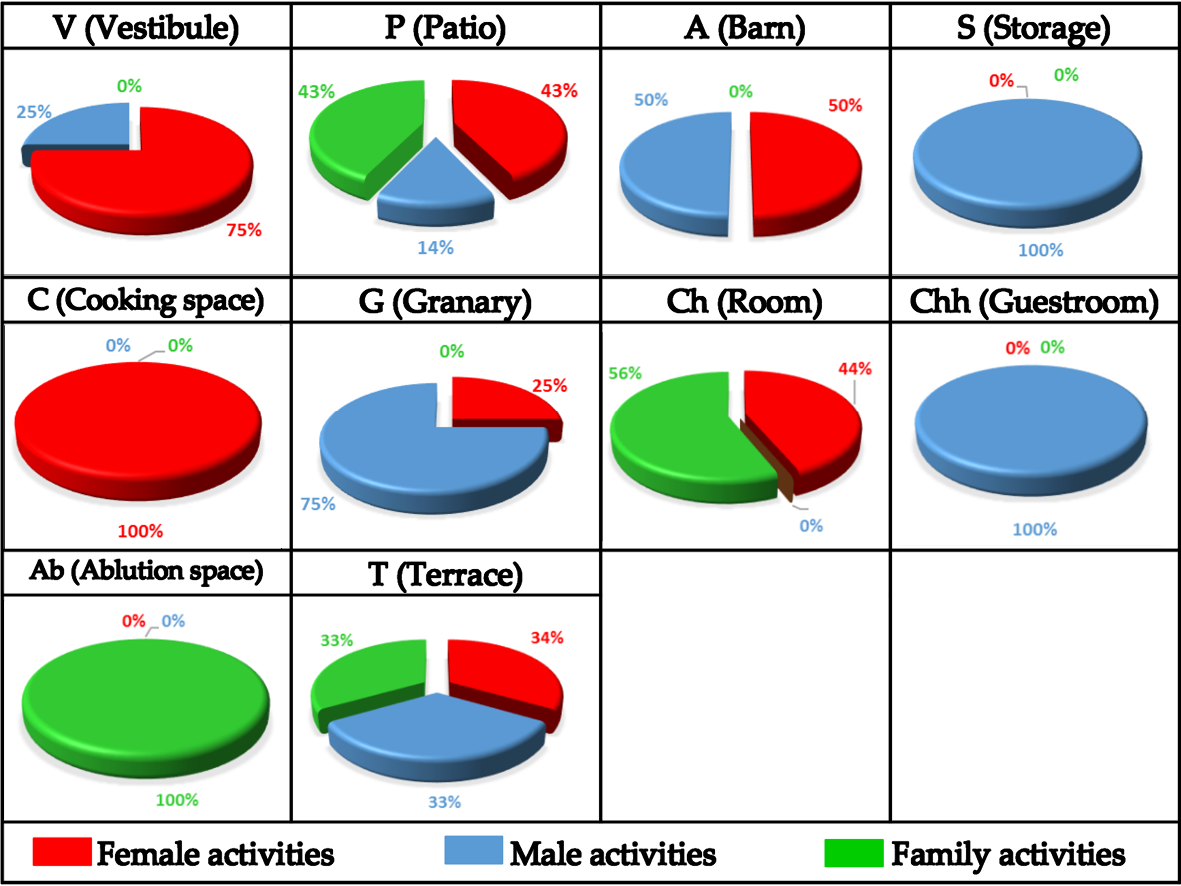

The digital data from Table 1.3 have been converted into graphs to better differentiate the type of user of the space (female, male and family). The kitchen contains 100% female activities (meal preparation, cooking), and men do not use this part of the house. The cooking space is the only space exclusively for female use. The storage space for agricultural equipment and the guest room (if it exists) is comprised of 100% male activities. The women do not engage in any activity in these two spaces that open onto the vestibule.

The ablution area houses 100% family activities. The family members (women and men) use the space to wash their bodies equally and without segregation. The barn includes 50% female activities and 50% male activities. Female and male activities take place in the same space but at different times of the day.

Fig. 1.2 Spatial characteristics according to female/male/family activity types. Author’s graphs, CC BY-NC-ND.

The vestibule represents mostly female activities, with a percentage of 75%, whereas male activities account for only 25% of the activities. No family activity occurs in this space of transition between the interior and the exterior of the home. The granary houses only 25% female activities and 75% male activities. The graph shows no family activity in the storage space. In all rooms except the cooking space, guest room, granaries and terrace, 44% female activities and 56% family activities occur, but there are no exclusively male activities that take place there. The patio involves exclusively female activities, family activities and exclusively male activities. In this area, female and family activities are carried out at the same rate, each representing 43% of the activities. However, the rate for male activities is much lower, at 14%.

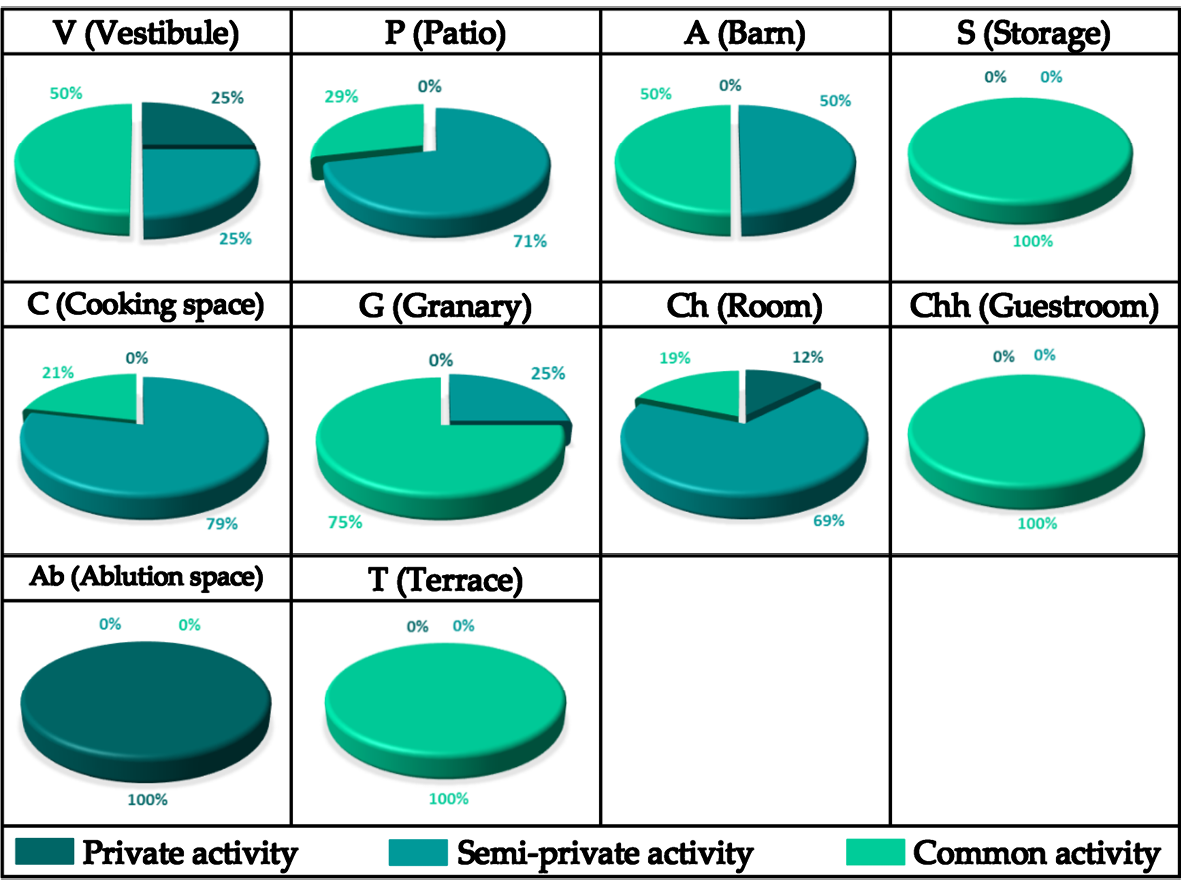

Spatial characteristics according to the degree of privacy (private, semi-private or common)

Figure 3 shows that the storage space for agricultural equipment, the guest room and the terrace allow common activities to be practised in front of different members of the extended family as well as people from outside the family. These spaces contain 100% common activities. The ablution space is used individually; it contains an intimate activity that is 100% private. The vestibule houses activities belonging to all three levels of privacy. Private activities and semi-private activities are equal in this area, at 25% each. The percentage of common activities is higher, at 50%.

The rooms, such as the vestibule, contain activities belonging to the three levels of privacy; however, the rates for practising each level are different. The activities are mostly semi-private, with a rate of 69%. Private activities have the lowest rate (12%), and the rate for common activities is 19%. The barn does not involve any private activity. Half the barn activities are semi-private (50%), and the other half are reserved for common activities. The patio houses 71% semi-private activities and only 29% common activities; no private activities are practised in this space.

Activities in the kitchen are mostly semi-private, with a rate of 79%. Only 21% of the activities are common, and no private ones are performed in this space. Seventy-five per cent of the activities in the granary are common, 25% are semi-private and no private activity takes place in this storage space.

Fig. 1.3 Spatial characteristics according to the degree of privacy (private, semi-private and common). Author’s graphs, CC BY-NC-ND.

Characteristics of socio-spatial practices in vertical troglodytic dwellings

According to Letesson, socio-spatial analysis reveals ‘the intrinsic relationships between the social and the architectural aspects, between a human group and its built space’.8 This study allows the detection of certain principles that govern the socio-cultural life of the inhabitants of Beni Zelten and that are inscribed in the architectural object by well-defined spatial organisation.

The entrance hall is a transitional space between the interior, the domain of the family’s private life, and the exterior, the domain of the community’s collective life. It is a common space for all users of the dwelling, but it is forbidden to those who do not reside in the dwelling, except with the inhabitants’ permission. Depending on the time of day, the degree of privacy of this space may change. It preserves the intimacy of the home and especially the privacy of women. The vestibule is in direct connection with the patio, the stable, the storage space for agricultural equipment, and, in some rare cases, the guest room.

On either side of the vestibule, we find excavations that are used to shelter domesticated animals and agricultural tools. These service spaces, located close to the entrance of the house, are far from the human spaces. The storage space and the barn are considered less ‘noble’ and less clean than the rest of the spaces, but they are essential to maintain the inhabitants’ way of life. These service spaces house mostly common male activities. In some houses, the vestibule has a guest room, which is never arranged around the central courtyard of the dwelling. The guest room is intended to accommodate outside visitors who visit the family for wedding ceremonies or mourning. It is accessible through the vestibule to avoid interfering with the intimacy of the women of the house.

The patio houses activities mainly of a female and family nature, which are mostly semi-private. This space, which is especially utilised by women, is used for meeting family members, weaving, washing and drying laundry, grinding grain, taking meals and so on. However, the men occupy this space to repair the agricultural equipment, to work the alfa, for gatherings and other such activities. The rooms are multipurpose spaces where essentially private activities are carried out, especially by women. The kitchens are exclusively for female use and essentially qualified as semi-private. Most of the studied houses have one or more granaries. These spaces are used for the storage of the food supply (cereals, olives, dried figs, etc.), which can be rare and very valuable, especially during difficult years, when irregular rainfall impedes agricultural production in the area. These granaries, with their difficult access, are rarely used and represent areas for men to practice common activities.

The spatial practices in the studied houses are the result of the interaction between the natural context, represented by the available resources, and the particular socio-economic context. This interaction gave birth to an intangible heritage housed in a tangible heritage that is now abandoned. Since the 1950s and 1960s, the inhabitants of the village have occupied new forms of built housing where the old socio-spatial practices have mixed with new ones. These are dictated by the change in the sectors of activity of the population and by the adoption of new standards of modern life.

Conclusion

This study showed that in the troglodytic houses in Beni Zelten, South-Eastern Tunisia, the dwelling is the women’s domain par excellence. There is a gendered spatial distribution that has also been found to manifest in several other societies. Men occupy the house during moments of rest or to carry out complementary activities to their agropastoral occupations on agricultural lands. Thus, the dwelling ensures the security and preserves the intimacy of the family and the privacy of women. As Zaied confirms, ‘the idea of honour is linked to three entities: The tribe, the family and the woman. […] This control is even more severe with regard to women. […] She is even one of the symbols of honour’.9 The village of Beni Zelten, like all Jbelia villages, has long suffered from insecurity and political conflicts between tribes. The houses were an adapted response to these situations that would allow inhabitants to contend with invaders and looters. The houses are underground dwellings that are difficult for enemies to spot. Access is provided through a transitional space (vestibule) and is never direct. Finally, the food supply is stored in granaries that are difficult to access.

The south-eastern region of Tunisia is strongly affected by the phenomenon of migration. Nasr speaks about ‘a very ancient Dynamic for more than four centuries (organized emigration)’.10 These migratory movements intensified around the middle of the twentieth century in the aftermath of World War II. Young people of working age then left their native regions for big cities in Tunisia or abroad in search of better paying jobs and better living conditions. The dwellings in the troglodytic villages were subsequently abandoned. They have been replaced by built houses that are better adapted to the standards of modern life, characterised by the standardisation of daily activities and current needs. Troglodytic dwellings as tangible heritage fell into ruin and gradually deteriorated over time.

What should we say about socio-spatial practices, considered to be intangible heritage, that fall completely into oblivion? According to the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage ‘Social practices, rituals and festive events are strongly affected by the changes communities undergo in modern societies. […] Processes such as migration, individualisation, the general introduction of formal education […] have a particularly marked effect on these practices.11 Thus, this study represents an opportunity to reveal socio-spatial practices in troglodytic dwellings in the village of Beni Zelten as intangible heritage. It could be extended to other villages in the same region or to other regions. This troglodyte heritage reflects the identity of the region. It is time for politicians, heritage authorities and architects to take action to protect these sites and proceed with their registration as cultural heritage before it is too late.

Bibliography

Baduel, Pierre-Robert, Habitat–Etat–Société au Maghreb (Paris: CNRS, 1988).

Eleb, Monique and Chatelet, Anne-Marie, Urbanité, sociabilité et intimité: Des logements d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Epure, 1997).

Golany, Gideon, Earth Sheltered Dwellings in Tunisia: Ancient Lessons for Modern Design (Newark: University of Deleware Press, 1988).

ICOMOS, Intangible Heritage, Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage / Québec declaration on the preservation of the spirit of place / The ICOMOS charter for the interpretation and presentation of cultural heritage sites with a bibliography based on documents available at the UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. August 2011, https://www.icomos.org/centre_documentation/bib/2011_intangible-heritage_complete.pdf.

Letesson, Quentin, Du phénotype au génotype, analyse de la syntaxe spatiale en architecture minoenne (MMIIIB-MRIB) (Belgium: Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2009).

Libaud, Geneviève, Symbolique de l’espace et habitat chez les Beni-Aïssa du sud tunisien (Paris: CNRS, 1986).

Louis, André, ‘L’habitation troglodyte dans un village des Matmata’, Cahiers des Arts et Traditions Populaires, 2 (1968), 33–60.

Nasr, Noureddine, ‘Agriculture et émigration dans les stratégies productives des jbalia du Sud-Est tunisien’, in Environnement et sociétés rurales en mutation: Approches alternatives, ed. by Michel Picouet, Mongi Sghaier, Didier Genin et al. (Paris: IRD Editions, 2004), pp. 247–57.

Trebbi, Jean-Charles and Bertholon, Patrick, Habiter le paysage (Paris: Alternatives, 2007).

Zaïed, Abdesmad, Le monde des Ksours du sud tunisien (Tunis: Centre de Publication Universitaire, 2006).

1 ICOMOS, Intangible Heritage, Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage / Québec declaration on the preservation of the spirit of place / The ICOMOS charter for the interpretation and presentation of cultural heritage sites with a bibliography based on documents available at the UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. August 2011, https://www.icomos.org/centre_documentation/bib/2011_intangible-heritage_complete.pdf

2 Jean Charles Trebbi and Patrick Bertholon, Habiter le paysage (Paris: Alternatives, 2007), p. 7.

3 Gideon Golany, Earth Sheltered Dwellings in Tunisia: Ancient Lessons for Modern Design (Newark: University of Deleware Press, 1988), p. 19.

4 André Louis, ‘L’habitation troglodyte dans un village des Matmata’, Cahiers des Arts et Traditions Populaires, 2 (1968), 33–60.

5 Geneviève Libaud, Symbolique de l’espace et habitat chez les Beni-Aïssa du sud tunisien (Paris: CNRS, 1986), p. 111.

6 Pierre Robert Baduel, Habitat–Etat–Société au Maghreb (Paris: CNRS, 1988), p. 234.

7 Monique Eleb and Anne-Marie Chatelet, Urbanité, sociabilité et intimité: Des logements d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Epure, 1997), p. 350.

8 Quentin Letesson, Du phénotype au génotype, analyse de la syntaxe spatiale en architecture minoenne (MMIIIB-MRIB) (Belgium: Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2009), p. 5.

9 Abdesmad Zaïed, Le monde des Ksours du sud tunisien (Tunis: Centre de Publication Universitaire, 2006), pp. 151–53.

10 Noureddine Nasr, ‘Agriculture et émigration dans les stratégies productives des jbalia du Sud-Est tunisien’, in Environnement et sociétés rurales en mutation: Approches alternatives, ed. by Michel Picouet, Mongi Sghaier, Didier Genin et al. (Paris: IRD Editions, 2004), pp. 247–57.

11 ICOMOS, Intangible Heritage, Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage / Québec declaration on the preservation of the spirit of place / The ICOMOS charter for the interpretation and presentation of cultural heritage sites with a bibliography based on documents available at the UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. August 2011, https://www.icomos.org/centre_documentation/bib/2011_intangible-heritage_complete.pdf