10. Integrity and Authenticity:

Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (Chile)1

©2024 F. S. Irribarra & G. R. Alfaro., CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.10

Introduction

The Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works were inscribed on the World Heritage List in July 2005 as a single industrial complex, although they operated independently in the past. They were included on the List of World Heritage in Danger simultaneously because of their structures’ vulnerability—namely, the integrity threat stemming from extensive damage to metal and wood, accentuated by the harsh desertic environment. UNESCO’s decision recognized the need to both safeguard and conceptually reflect on the site’s authenticity when undertaking conservation works that might involve the replacement of irredeemably deteriorated materials.2

Moreover, the aim to conserve original material traces, as evidence and sources for an understanding of the past, is particularly challenging in mining complexes, where the infrastructure usually responded to the needs and life cycle of the extracting process and its materials were not designed to last.

This chapter discusses the concept of authenticity theoretically, and its relationship with original material integrity in the context of world heritage, to evaluate the conservation works undertaken in Humberstone and Santa Laura which brought it into compliance with the Desired State of Conservation for the Removal (DSOCR) from the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2019. The case study illustrates how integrity and authenticity concerns were approached at a World Heritage Site made up of vulnerable temporary mining structures under extreme environmental conditions.

Authenticity in world heritage

In the heritage field, few topics have been more controversial than authenticity.3 Lowenthal warns that ‘authenticity risks being a risible as well as a futile quest’.4 Similarly, Page states that architectural authenticity is no more than a ‘mirage, and a chimera, something we can only imagine exists’.5 Page relates authenticity to something original, pristine or unchanged.6 In defining authenticity by those parameters, it becomes evident that any place that appears perfectly authentic cannot be so because all materials age and change.

Regarding understandings of heritage, Starn argues that the Venice Charter of 1964 was responsible for situating the concept of authenticity at the core of conservation practice.7 The Venice Charter stated that it is our duty to safeguard and handle historic monuments ‘in the full richness of their authenticity’.8 In the Venice Charter, the concept of authenticity translates into honest conservation—that is, replacements should be distinguishable from the original and at the same time integrated harmoniously with the whole; restoration must rely on evidence, not conjecture; and documentation of works must be precise.9

The 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage incorporates the concept of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) as the fundamental condition for inscription as World Heritage,10 where the definition is specified by the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. These guidelines are revised and updated periodically, while the Convention document remains unchanged from its 1972 version. In the 1977 version of the operational guidelines, it states that properties should ‘meet the test of authenticity in design, materials, workmanship and setting’11to become part of the World Heritage List, along with complying with at least one of the criteria for inclusion.12

The definition of authenticity in the Operational Guidelines was expanded in 2005 after the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994) was developed.13 The Nara Document became part of Annex 4 to the 2005 guidelines to further bolster the concept’s interpretation.14 Both Jones and Starn emphasise the relevance of Article 11 as a turning point from previous notions of authenticity.15

Article 11 of the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994):

All judgements about values attributed to cultural properties as well as the credibility of related information sources may differ from culture to culture, and even within the same culture. It is thus not possible to base judgements of values and authenticity within fixed criteria. On the contrary, the respect due to all cultures requires that heritage properties must be considered and judged within the cultural contexts to which they belong.16

The Nara Document relativises the idea of authenticity, acknowledging that it cannot mean the same thing to different cultures because it should be judged within its cultural setting. Nonetheless, the document still relies on the credibility of information sources to determine veracity according to the specific nature of heritage values. After the Nara conference, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and National Committees of the Americas met to discuss the concept of authenticity in their specific context, consolidating the Declaration of San Antonio in 1996. The Southern Cone, which includes Chile, prepared the Carta de Brasilia (The Brasilia Charter) in 1995 for the San Antonio assembly, in which it was argued that authenticity is entangled with the idea of identity, and as such, is changeable, adaptable and dynamic. The Charter indicates that identities acquire value; they can also devalue or become valuable again as part of social processes.17 The Brasilia Charter relates authenticity to the correspondence between an object and its significance; it states, ‘[N]os hallamos ante un bien auténtico cuando existe una correspondencia entre el objeto material y su significado’ [We face an authentic object when some correspondence exists between the material object and its significance].18 Therefore, it could be argued that the Brasilia Charter advocates for a notion of authenticity that is self-verifiable in the fulfilment of its values—that is, significance.

The Declaration of San Antonio (1996) states, ‘the authenticity of our cultural resources lies in the identification, evaluation and interpretation of their true values as perceived by our ancestors in the past and by ourselves now as an evolving and diverse community’.19 It also emphasises the importance of values being true. Almost ten years later, in the Declaration of San Miguel de Allende of 2005, as part of the New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas, ‘it is noted that the concepts of authenticity and integrity need to be fully integrated into field practices in all its facets’.20 It is interesting to compare the statement of the declaration with the specific section on La Autenticidad e integridad en las polítcas de patrimonio mundial de Chile [Authenticity and integrity in world heritage policies of Chile], where Ángel Cabeza, former head of the institution responsible for the protection of national cultural heritage, the National Monuments Council of Chile, endorses the view that authenticity and integrity are the axes of the identification, management and use of heritage conservation.21 However, he also states, ‘[L]a comunidad debe tener claros los valores que se deben conservar, y su respaldo a la autenticidad se dará por añadidura’ [The community must understand the values that need to be conserved, and with their support authenticity will come naturally].22

From the revision of charters and conventions, two dimensions emerge for determining authenticity. One refers to the truthfulness of significance or values, the judgment of which should be contextually defined and expressed by their attributes (‘including form and design; materials and substance; use and function; traditions, techniques and management systems; location and setting; language, and other forms of intangible heritage; spirit and feeling; and other internal and external factors’).23 The other dimension relates to the veracious transmission of significance by practice and/or interpretation.

Although the conventions appear to relate authenticity to truthfulness, there is yet another understanding of authenticity that is of interest. In Jones’ article titled ‘Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves: Beyond the Deconstruction of Authenticity’, she states that a problematic dichotomy characterises our understanding of authenticity. On one hand, there is the constructivist perspective that understands authenticity as a cultural construction, while on the other, there is the materialist approach that assumes authenticity is an integral part of objects. Jones proposes that authenticity should be considered as neither culturally constructed nor integral to objects, but instead described as ‘a product of the relationships between people and things’.24 Hence, heritage objects embody networks of authentic relationships.25 Although Smith’s work relates to the constructivist approach, as authenticity may be understood as a product of the Authorised Heritage Discourse, it is interesting to note that in Uses of Heritage, Smith mentions that ‘authenticity of heritage lies ultimately in the meanings people construct for it in their daily lives’.26 Therefore, Jones’ understanding of authenticity relates to Smith’s statement, viewing it as something neither foreign nor inherent in objects but something in between that emerges in the relation between people and places. Both Jones and Smith see authenticity as dynamic rather than stable and not inherent, but relational.

How authenticity is understood may qualify what is expected of conservation works, conditioning whether interventions are considered appropriate. When judging authenticity through the lens of the UNESCO Operational Guidelines, many outcomes are possible. One could conclude that material and substance contribute to a site’s authenticity, and thus that ageing and patina are befitting of a heritage site, being the proper condition of original material, which needs to be safeguarded. Opposingly, following the same guidelines, authenticity can be related to use and function. Therefore, a derelict condition could be considered a sign of neglect that makes the history of the site less legible, threatening its authenticity by making its use difficult to interpret. In this sense, ‘tampering with the past is inescapable, its outcome neither true nor false, right nor wrong, but a matter of choice and chance’.27

The Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works as World Heritage

World Cultural Heritage is defined in Article 1 of the World Heritage Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage as monuments, groups of buildings or sites of OUV.28 According to the 2005 Operational Guidelines, the World Heritage Committee considers a site as having OUV when it meets at least one of ten criteria, complies with conditions of integrity and/or authenticity and has adequate protection and management. All properties must satisfy the integrity condition, whereas only properties nominated under Criteria (i) to (vi) must meet the authenticity condition. Criteria (i) to (vi) refer to cultural heritage, whereas Criteria (vii) to (x) characterise natural heritage.29

Fulfilling the integrity and authenticity aspects can be especially challenging for mining complexes. These industries are usually located in extreme environmental conditions with materials likely to be vulnerable, because they were not designed for endurance but rather to provide a temporary settlement for the duration of extraction processes. The Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works exemplify this dilemma. Both its integrity and authenticity were considered endangered—either because of the damaged condition of its fabric or the potential replacement of its original materials for conservation purposes.

The Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works were inscribed as cultural heritage under Criteria (ii), (iii) and (iv). These criteria refer to the interchange of human values, manifested in the exchange between people of South America and Europe, the testimony of a cultural tradition revealed in the distinct culture of the inhabitants of the area—the pampinos—and the illustration of a significant stage in human history, as the saltpeter mines in the north of Chile transformed the Pampa30 and agricultural lands that benefited from nitrate as fertiliser. How the site complies with the three cultural criteria is specified in the Decisions of the 29th session of the World Heritage Committee as follows:

Criterion (ii): The development of the saltpeter industry reflects the combined knowledge, skills, technology, and financial investment of a diverse community of people who were brought together from around South America, and from Europe. The saltpeter industry became a huge cultural exchange complex where ideas were quickly absorbed and exploited. The two works represent this process.

Criterion (iii): The saltpeter mines and their associated company towns developed into an extensive and very distinct urban community with its own language, organisation, customs, and creative expressions, as well as displaying technical entrepreneurship. The two nominated works represent this distinctive culture.

Criterion (iv): The saltpeter mines in the north of Chile together became the largest producers of natural saltpeter in the world, transforming the Pampa and indirectly the agricultural lands that benefited from the fertilisers the works produced. The two works represent this transformation process’31.

Along with these criteria, in order to be considered to have OUV, the Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works had to comply with an integrity and authenticity condition. The authenticity description of this property on the UNESCO website considers both tangible and intangible dimensions. In terms of the tangible aspect, it states that the remains at the site are ‘authentic and original’. Their authenticity is enhanced by their setting in a desertic landscape, evidencing the territory’s occupation, and a lack of additions from periods other than the saltpeter era. The Saltpeter Week gathering of saltpeter workers and descendants is mentioned as one of the intangible attributes contributing to the site’s authenticity.32 Saltpeter Week is a festival that takes place every third week of November and gathers people from different pampinos’ associations to commemorate and celebrate the Pampa culture. Activities have been held in Iquique—the nearest major city—and culminated in Humberstone since 1981.33

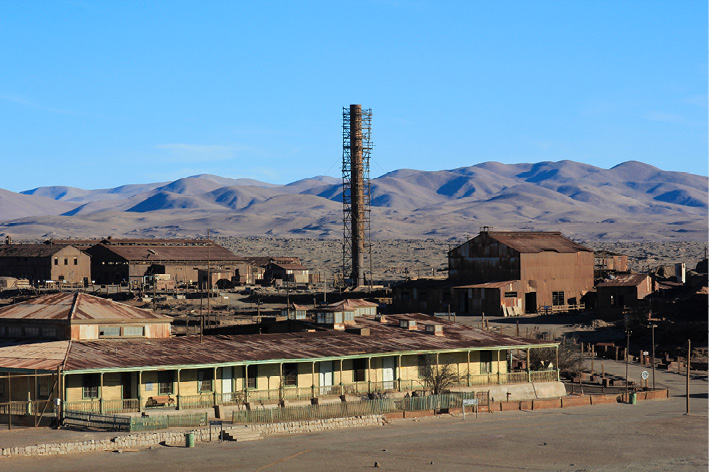

In terms of integrity, Humberstone and Santa Laura are the most intact vestiges of the 200 saltpeter works that once populated the area of Antofagasta and Tarapacá in Chile. The sites were inscribed together, despite operating independently in the past, because looting and demolition had affected the integrity of both saltpeter works. Nonetheless, when combined, they were deemed to still reflect ‘the key manufacturing processes and social structures and ways of life of these company towns’.34 The industrial equipment is readable in Santa Laura, whereas the urban settlement is distinct in Humberstone (see Fig. 10.1 and Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.1 Santa Laura Saltpeter Works. Photograph by Diego Ramírez, 2019, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 10.2 The public heart of Humberstone, with the plaza surrounded by the pulpería, the market and the hotel in photograph from the theatre (2012). Photograph by Juan Vásquez Trigo, 2012, CC BY.

Humberstone stands as an example of the many urban camps that existed at the Pampa, and its infrastructure is representative of the urban lifestyle in the saltpeter works. The site comprises living quarters, a tennis court, an administration house, the main square, a theatre, a grocery store, a swimming pool, a chapel, a hospital and a school, among other urban equipment and some of the industrial infrastructure that belonged to the complex (see Fig. 10.3, Fig. 10.4 and Fig. 10.5). In contrast, the Santa Laura remnants mostly comprise the industrial infrastructure necessary to extract the mineral, including the leaching plant, where the water tanks necessary for processing the nitrate were stored. This is the only such structure that survives from all the saltpeter works that once existed at the Pampa (see Fig. 10.6).35 Both sites conserve their tailing cakes, ‘where all the waste from the mine was dumped’.36

Fig. 10.3 Humberstone theatre and housing. Photograph by Jorge López, 2019, Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 10.4 Succession of woods, corrugated zinc plates, caliche grounds and hills to define the view to the northwest of the camp and the industrial sector. Photograph by Juan Vásquez Trigo, 2012, CC BY.

Fig. 10.5 The old theatre of La Palma, transformed into the Boy Scouts headquarters. Photograph by Juan Vásquez Trigo, 2012, CC BY.

Fig. 10.6 In the picture, Santa Laura’s chimney and leaching plant are visible. Photograph by Jorge López (2019), Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural, CC BY-NC-ND.

The Humberstone Saltpeter Works is located approximately 1.5 km northeast of the Santa Laura Saltpeter Works. The nearest town to the World Heritage Site is Pozo Almonte, located 8 km south. Its closest city is the port of Iquique, the Tarapacá Region’s capital, located 47 km east of the complex.37 Both saltpeter works are located in the dry and arid Pampa landscape, where the average annual temperature rises to 30 °C during the day and drops to 2 °C at night.38 The sites’ buildings were constructed mainly of timber and calamine (metal sheets).39

The Humberstone Saltpeter Works, formerly La Pampa, was established in 1862, whereas Santa Laura was built in 1872. Both remained up and running during the saltpeter industry rise, boom and crisis, closing their doors in 1960. The saltpeter industry flourished at the Pampa from the first decade of the nineteenth century. Nitrate was processed to be used as fertiliser. It was widely exported to international markets until the production of synthetic fertilisers in the 1920s, which led to the saltpeter crisis, followed by the Great Depression of 1929. As a result, both saltpeter works stopped their production and were bought by the Chilean private company Compañía Salitrera de Tarapacá y Antofagasta (COSATAN). In 1959, COSATAN was shut down, and Humberstone and Santa Laura were auctioned off in 1961 to be dismantled.40

The saltpeter works were protected by Chilean law as Historic Monuments in 1970 to avoid their demolition, however, they remained neglected until the 1990s. No management plan was developed until 2002, when the Saltpeter Museum Corporation—a non-profit institution formed in 1997 by the inhabitants and descendants of the various former Pampa saltpeter workers—acquired the site by public auction.41 The pampinos were the ones that pushed the nomination of the site. They submitted the 20,000 signatures that endorsed the nomination to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre.42

The lack of maintenance that threatened the site over forty years had repercussions for the evaluation undertaken by ICOMOS for the World Heritage Committee, which emphasised the need to keep the buildings standing and avoid further ‘erosion of integrity’.43 As a result, the saltpeter works were inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger, ‘considering the ascertained threats to the vulnerable structures forming the property, and in order to support the urgent and necessary consolidation work, as well as to safeguard the authenticity of the property by setting appropriate benchmarks in the conservation plans’,44

In terms of how the conservation works should manifest, UNESCO states that ‘it is necessary to conceptually reflect on authenticity which opens up a space coherently with replacing those pieces and sections that have irredeemably deteriorated, defining a criteria for change associated with that degradation, in order to maintain them for all time’.45 There appears to be an inherent contradiction in the aim to maintain what was not meant to last for all time. Nonetheless, from an atheoretical standpoint, authenticity does not depend exclusively on the site’s material aspect, and conservation works will unescapably modify physical attributes.

World Heritage in danger: Conservation efforts and the inevitability of change in Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works

UNESCO based the decision to include Humberstone and Santa Laura in the List of World Heritage in Danger on the urgent need for consolidation work and the safeguarding of authenticity ‘by setting appropriate benchmarks in the conservation plans’.46 To be removed from the Heritage List in Danger, which happened in July 2019,47 the site had to achieve the DSOCR. The DSOCR included four conservation axes, described as follows:

- Stability, authenticity, integrity, safety, and security: Urban and industrial constructions of the Santa Laura and Humberstone saltpeter works have been stabilised, and their integrity and authenticity are guaranteed, on the basis of an agreed, long-term, comprehensive conservation strategy, and conservation plan. These buildings bear witness to the key historical, industrial, and social processes associated with the Humberstone and Santa Laura saltpeter works,

- Management system and plan: The management system is fully operational, with adequate funding for operation. The comprehensive management plan, with conservation and management provisions for the property and its buffer zone, is fully enforced and implemented through an interdisciplinary group, with the participation of involved institutions and social stakeholders,

- Presentation of the Property: The World Heritage property complies with safety and security standards for visitors and workers, and the assets of the property are adequately protected. Its Outstanding Universal Value is reliably conveyed to the public, which facilitates comprehension of the saltpeter era and the mining processes,

- Buffer Zone: There is a buffer zone that is protected and regulated’48.

The first axis, focusing on integrity and authenticity, was accomplished by the three following actions: implementing the Priority Interventions Programme (PIP), developing a comprehensive conservation plan and implementing security and protection measures.49 The Ministry of Public Works, the Saltpeter Museum Corporation and the National Council of Monuments developed the PIP in 2005. Its objective was to establish which structures should be subject to intervention and when, in order to ensure the site’s integrity.50 The PIP describes four kinds of actions—setting security standards for visitors and workers, cleaning and selecting material, engaging in structural consolidation and establishing new infrastructure works.51 The programme included intervention on former housing, industrial areas, some public buildings and the extension of water and electrical supply to allow the site’s use as a museum.

The site’s conservation goals translate into efforts to stabilise and consolidate its structures, allow its feasible management and interpretation, and guarantee the security of the site as well as its visitors. The actions described in the PIP follow the minimum intervention principle, replacing what is beyond salvation using the same materials and construction systems as used in the rest of the site.52 The consolidation and stabilisation measures relate to the conservation of the tangible assets as ‘archaeological evidence’, which, according to the Joint ICOMOS–TICCIH Principles for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes, may be jeopardised if significant components are destroyed or removed.53 Nonetheless, as Cosson states, the evidential importance in the archaeological sense is not the only value embodied in industrial places, nor is it necessarily the most important.54 The site’s interpretation may conserve other industrial heritage dimensions when communicating workers’ skills, memories and social lives. One of the PIP’s actions to this end was establishing an interpretation centre at Humberstone’s former grocery store. Through human-scale sculptures as well as various artifacts and documents, it re-creates how the site was inhabited and offers a comprehensive exhibition of the saltpeter’s history.55

The interventions that have been undertaken so far in Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works can be described as selective and focused on particular security, accessibility and stabilisation issues. Because of the concerns for integrity and authenticity, activities have been largely focused on maintenance and consolidation rather than extensive restoration. For example, the conservation works on the energy house—where electricity was generated—consisted of the cleaning and removal of rubble; the restoration of a beam; the repositioning of metal sheets, windows and doors; and the implementation of security railings. At the same time, the conservation works on the corridor houses for married workers concerned the restoration of ceilings, reinforcements and reparation of cracks, and the installation of doors and windows.56

Dereliction prevails in Humberstone and Santa Laura even after the conservation works, which may be a consequence of intervening only to the extent strictly necessary for accessibility, keeping the original material fabric and replacing what is beyond salvation. This policy aligns with an understanding of the fabric on site as a source of valuable information about historical working conditions and economic structures of the saltpeter era, allowing reflections about the use or, perhaps, abuse of natural resources.57 Comprehension of the site relies on both the acknowledgment of its structures as specimens of a certain type of construction or architecture, and its relationship with its setting or surrounding landscapes, which were ‘affected by the industrial processes’ and ‘often have within their boundaries archaeological evidence spanning a considerable depth of time’.58 For example, the site’s tailing cakes stand as evidence of the transformation of the surroundings in the course of resource exploitation.

The site’s dilapidated appearance following the conservation works does not seem to be problematic to the site’s OUV; as the mission report from the ICOMOS visit in 2018 states,

[T]he property retains the authenticity of the attributes which contribute to its OUV. All the elements that compose the property manifest the different stages and processes through which the history of the place has evolved since its founding in the 19th century, its boom in the early 20th century, and the period of abandonment and partial decommissioning up to its recovery at the beginning of the 21st century.59

As the commission mentions, abandonment is one of the site’s historical layers that is discernible when visiting. Once the industry’s decline is recognised and understood as part of the site’s life cycle and constitutive of its authenticity, it is possible to embrace the material decay rather than fight against it. Although the site’s decayed state is not explicitly described as a desirable attribute, the lack of additions of elements different from the original is seen as helping to maintain the property’s authenticity, making the material decay an integral part of the scene.60 In her book titled Curated Decay, Heritage Beyond Saving, DeSilvey describes ‘arrested decay’ as the conservation policy used ‘when one wishes to maintain the site’s structural integrity yet preserve their ruined appearance’.61The Humberstone and Santa Laura conservation works seem to have developed in this direction because of the environmental conditions that are likely to keep the site’s patina.

Despite the apparent decay, the timber is expected to endure in the future; recent studies of wood structures in the leaching house of Santa Laura have shown that despite wood defibration, the material is mostly healthy and able to withstand a significant seismic event.62 The structural diagnosis may reinforce the practicality of minimum intervention criteria in the rest of the complex. It seems that the ruined fabric’s presence can also allow communities’ self-identification with material remains of their stories, which perform important emotional and symbolic functions on a personal level. The wear and tear of machinery, graffiti, and forgotten personal belongings convey the stories of workers and the wider community, whose lives were in the hands of the industry. These elements allow inferences to be made about people, places and purposes.63 With age, they carry personal significations to their users and enable users’ self-identification with them.

DeSilvey explores the relevance of accepting change and creative transformation as productive and positive in heritage contexts. She proposes that ‘the disintegration of structural integrity does not necessarily lead to the evacuation of meaning’.64 She suggests that change needs to be incorporated rather than denied because gradual decay may also provide memory-making engagement and interpretation opportunities in some contexts.65 As Holtorf argues,

‘[I]f we want to understand what heritage does and what is done to it in the contemporary world we need to see heritage in terms of persistence and change, persevering in a process of continuous growth and creative transformation’.66

Change can take many forms. In industrial sites, decay may reveal the ‘culture behind the material’ experienced through signs of age.67 Those sites are ‘identified with a value no longer measured in terms of functional performance but in its ability to evoke what is lost’.68

The inevitability of change in the Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works is evident. It can be argued that the conservation works on the site are responding to this reality and aim to manage it rather than deny it. The conservation goals are not intended to restore all buildings; rather, they are aimed at making the site accessible and secure, avoiding vandalism and guaranteeing the safety of both people and structures. In this sense, recent surveys that contribute to the site’s accessibility align with the conservation efforts undertaken. For example, since May 2020, it has been possible to explore the Saltpeter Interpretation Centre virtually and take guided tours of Santa Laura from home.69 Indeed, Santa Laura’s online tour allows access to the Leaching Plan’s first floor, which is not accessible on the site because of security concerns. Humberstone and Santa Laura’s recorded guided tour was arranged for the Chilean national Día del Patrimonio Cultural (Day of Cultural Heritage), and it is still available online, among other digital resources.70

The measures taken at the site are considered to have actively supported people’s connection to place while allowing for its feasible management, and each intervention provides specific opportunities for negotiation and challenge. The site depends on diverse stakeholders’ agreement, and it is this ongoing local negotiation that will shape its future. Documenting and partially allowing the Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works’ material detriment seems appropriate when considering the mining heritage material’s life cycle as constitutive of the site’s character. Nonetheless, the decay of the site will be in tension with the current needs of accessibility and interpretation, and it is this tension that will define its future.

Conclusion

The Humberstone and Santa Laura conservation efforts take into account the periods of abandonment and subsequent recovery in the site’s history. The UNESCO and Chilean integrity concerns about the vulnerability of its structures and the possible consequences for its authenticity reveal views about the relationship between these concepts and material conservation, which can be jeopardised by the disappearance or damage of fabric. Nevertheless, the conservation works carried out at the site, such as security measures, consolidation and stabilisation work and new infrastructure for interpretation, inevitably change material aspects of the site. However, when authenticity is understood as dynamic and multidimensional in the sense that interpretation, accessibility and reflective actions add to it as it is constantly co-created, change may be a constructive force for the future of heritage.

It is tempting to discard the concept of authenticity as vague and overly fixated on material originality. This line of thought would see our present and future as an uncomfortable and inauthentic disruption of the past. However, authenticity may be useful when we understand heritage not as found authentic places but rather as sites for the constant re-creation of values, significance, and therefore, authenticity.

The difficulties that have emerged from integrity and authenticity concerns in Humberstone and Santa Laura imply negotiations between different stakeholders who, in allowing the conservation, share the common objectives of accessibility, transmission and forging of significance while allowing the educational use of the site. The cautious approach partially accepts decay as a natural part of the site’s heritage, while allowing change that works towards its contemporary valorisation.

In Humberstone and Santa Laura, the material decay of temporal mining camps coexists with efforts to keep them standing for their interpretation. The conservation efforts on site shift between enabling the expression of age and keeping the saltpeter era legible. Still, since heritage values are not inherent properties of a place or construction, conservation status or attitudes to conservation cannot be viewed as final. Conversely, they should be adaptive and transient enough to comprehend and enhance the malleable reality of the substance to be conserved and the changeable reality of its beholders.

Bibliography

Alivizatou, Marilena, ‘Debating Heritage Authenticity: Kastom and Development at the Vanuatu Cultural Centre’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18:2 (2012), 124–43, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.602981.

Cabeza Monteira, Ángel, ‘La Autenticidad e Integridad En Las Políticas de Patrimonio Mundial En Chile’, in Nuevas Miradas Sobre La Autenticidad e Integridad En El Patrimonio Mundial de Las Américas | New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas, by ICOMOS, ed. by Francisco Javier López Morales, 2nd ed. (México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2017), pp. 147–55.

Capture3DChile, Pulpería de Santiago Humberstone, Corporación Museo del Salitre (2020).

Chilean Government, Ministry of Cultures, Arts and Heritage, ‘Being in Danger, an Honest Way to Safeguard. The Case of Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works’ (presented at the HeRe—Heritage Revivals—Heritage for Peace, Bucharest, Romania, 2019).

Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales, Corporación Museo del Salitre, and Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Programa de Intervenciones Prioritarias Para Las Oficinas Salitreras Humberstone y Santa Laura, 2005-2006, 2005.

Corporación Museo del Salitre, http://www.museodelsalitre.cl/.

Cossons, Neil, ‘Why Preserve Industrial Heritage’, in Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation, ed. by James Douet (Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited, 2012), pp. 6–16.

DeSilvey, Caitlin, Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Emmison, Michael, and Philip Smith, Researching the Visual: Images, Objects, Contexts and Interactions in Social and Cultural Inquiry (London: SAGE, 2000).

Getarq, Planta de Lixiviacion, Salitrera Santa Laura, Patrimonio Accesible, https://www.getarq.com/tour360/santa_laura/index.htm.

Gobierno de Chile, and Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural, Programa de Intervenciones Prioritarias 2005-2018. Sitio de Patrimonio Mundial Oficinas Salitreras Humberstone y Santa Laura (Chile, 2018).

Holtorf, Cornelius, ‘Averting Loss Aversion in Cultural Heritage’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21:4 (2015), 405–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.938766.

ICOMOS, Humberstone and Santa Laura (Chile) No 1178, 2005.

ICOMOS, ‘International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter)’, 1964.

ICOMOS, Joint ICOMOS–TICCIH Principles for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes, 2011, https://www.icomos.org/Paris2011/GA2011_ICOMOS_TICCIH_joint_principles_EN_FR_final_20120110.pdf.

ICOMOS, Nuevas Miradas Sobre La Autenticidad e Integridad En El Patrimonio Mundial de Las Américas | New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas, ed. by Francisco Javier López Morales, 2nd ed. (México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2017).

ICOMOS, The Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994, https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf.

ICOMOS Argentina, ICOMOS Brasil, ICOMOS Chile, ICOMOS Paraguay, and ICOMOS Uruguay, Carta de Brasilia, 1995, http://www.icomoscr.org/doc/teoria/VARIOS.1995.carta.brasilia.sobre.autenticidad.pdf.

ICOMOS National Committees of the Americas, The Declaration of San Antonio

(1996), https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/188-the-declaration-of-san-antonio.

Jokilehto, Jukka, and ICOMOS, eds., The World Heritage List - What Is OUV? Defining the Outstanding Universal Value of Cultural World Heritage Properties, Monuments and Sites, 16 (Berlin: hendrik Bäßler verlag, 2008).

Jones, Siân, ‘Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves: Beyond the Deconstruction of Authenticity’, Journal of Material Culture, 15:2 (2010), 181–203, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183510364074.

Lowenthal, David, ‘Authenticities Past and Present’, CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship, 5:1 (2008), 6–17.

Lowenthal, David, ‘Authenticity? The Dogma of Self-Delusion’, in Why Fakes Matter: Essays on Problems of Authenticity, ed. by Mark Jones (London: British Museum Press, 1993), pp. 184–92.

Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio de Chile, and UNESCO World Heritage, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works, Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/humberstone-and-santa-laura-saltpeter-works/XQVRfkn12rzafA.

Nora, Pierre, ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, 26 (1989), 7–24, https://doi.org/10.2307/2928520.

Ortiz, R., A. Jamet, A. Moya, M. González, M. Paz Varela, M. Hernández, and others, ‘Diagnóstico de la Planta de Lixiviación de la oficina Salitrera Santa Laura en Chile. Patrimonio de la Humanidad’, Informes de la Construcción, 67:540 (2015), e115, https://doi.org/10.3989/ic.14.101.

Page, Max, Why Preservation Matters (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

Recorrido por Humberstone | Colores del norte (2020), https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=692114534918224&ref=watch_permalink.

Republic of Chile, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works. Nomination for Inclusion on the World Heritage List/UNESCO, 2003, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1178/documents/.

Schlereth, Thomas, ‘Material Culture and Cultural Research’, in Material Culture: A Research Guide, ed. by Thomas Schlereth (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), pp. 1–34.

Smith, Laurajane, Uses of Heritage (Abingdon, Oxon.; New York: Routledge, 2006).

Starn, Randolph, ‘Authenticity and Historic Preservation: Towards an Authentic History’, History of the Human Sciences, 15:1 (2002), 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695102015001070.

Stuart, Iain, ‘Identifying Industrial Landscapes’, in Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation, ed. by James Douet (Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited, 2012), pp. 48–54.

Tempel, Norbert, ‘Post-Industrial Landscapes’, in Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation, ed. by James Douet (Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited, 2012), pp. 142–49.

UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, 1972, http://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf.

UNESCO, Report of the ICOMOS Advisory Mission to Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (Chile) (1178bis), 4 November 2018, https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/3883.

UNESCO World Heritage, The Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works Site (Chile), Removed from the List of World Heritage in Danger, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1997/.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Decision 29 COM 8B.52 Inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger (Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works), 2005, https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/517/.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Decision 37 COM 7A.37 Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (Chile) (C 1178) (2013), UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/5014/.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works, UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1178/.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 2005, https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 1977, https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide77b.pdf.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/.

World Heritage Committee, Decisions of the 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee, 2005, https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2005/whc05-29com-22e.pdf.

1 The authors thank Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) Magister Becas Chile 2019/73200337, ANID Doctorado Becas Chile 2019/72200044 Scholarships and the Master of Urban and Cultural Heritage program at the University of Melbourne. The authors also thank Dr. Stuart King for his comments and support, as well as Diego Ramírez, Juan Vásquez Trigo, María Pilar Matute, Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural (Chile) and Corporación Museo del Salitre for their generosity in sharing information and photographs.

2 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (Whc.unesco.org, n.d.), https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1178/

3 Marilena Alivizatou, ‘Debating Heritage Authenticity: Kastom and Development at the Vanuatu Cultural Centre’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18:2 (2012), 124–43.

4 David Lowenthal, ‘Authenticity? The Dogma of Self-Delusion’, in Why Fakes Matter: Essays on Problems of Authenticity, ed. by Mark Jones (London: British Museum Press, 1993), pp. 184–92 (p. 189).

5 Max Page, Why Preservation Matters (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), p. 33.

6 Ibid.

7 Randolph Starn, ‘Authenticity and Historic Preservation: Towards an Authentic History’, History of the Human Sciences, 15:1 (2002), 1–16.

8 ICOMOS, ‘International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter 1964)’, 1964.

9 Ibid.

10 Jokilehto, Jukka, and ICOMOS, eds., The World Heritage List - What Is OUV? Defining the Outstanding Universal Value of Cultural World Heritage Properties, Monuments and Sites, XVI (Berlin: hendrik Bäßler verlag, 2008), p. 47.

11 UNESCO, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 1997, p. 3, https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide77b.pdf

12 UNESCO, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 1977.

13 Jokilehto and ICOMOS, 2008, p. 43.

14 UNESCO, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 2005, pp. 91–93, https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/

15 Siân Jones, ‘Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves: Beyond the Deconstruction of Authenticity’, Journal of Material Culture, 15:2 (2010), 181–203; Starn, 2002.

16 ICOMOS, The Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994.

17 ICOMOS Argentina and others, Carta de Brasilia, 1995,

http://www.icomoscr.org/doc/teoria/VARIOS.1995.carta.brasilia.sobre.autenticidad.pdf

18 ICOMOS Argentina and others, 1995, p. 2.

19 ICOMOS National Committees of the Americas, The Declaration of San Antonio (1996), ICOMOS, https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/188-the-declaration-of-san-antonio.

20 ICOMOS, Nuevas Miradas sobre la Autenticidad e Integridad en el Patrimonio Mundial de las Américas | New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas, ed. by Francisco Javier López Morales, 2nd ed. (México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2017), p. 22.

21 Ángel Cabeza Monteira, ‘La Autenticidad e Integridad En Las Políticas de Patrimonio Mundial En Chile’, in Nuevas Miradas sobre la Autenticidad e Integridad en el Patrimonio Mundial de las Américas | New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas, by ICOMOS, ed. by Francisco Javier López Morales, 2nd ed. (México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2017), pp. 147–55.

22 Cabeza Monteira, 2017, p. 155.

23 UNESCO, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 2019, p. 27, https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/.

24 Jones, 2010, p. 200.

25 Ibid.

26 Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (Abingdon, Oxon, New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 6.

27 David Lowenthal, ‘Authenticities Past and Present’, CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship, 5:1 (2008), 6–17 (p. 14).

28 UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, 1972, http://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf.

29 UNESCO, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 2005, pp. 19–23.

30 According to the Royal Academy of the Spanish language, the word Pampa comes from the Quechua language and means plain or prairie; it refers to extending plains of South America without arboreal vegetation.

31 World Heritage Committee, Decisions of the 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee, 2005, p. 142, https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2005/whc05-29com-22e.pdf

32 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works.

33 Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio de Chile and UNESCO World Heritage, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works, Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/humberstone-and-santa-laura-saltpeter-works/XQVRfkn12rzafA; Republic of Chile, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works. Nomination for Inclusion on the World Heritage List/UNESCO, 2003, p. 78; UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1178/documents/; Corporación Museo del Salitre, http://www.museodelsalitre.cl/

34 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works.

35 Republic of Chile, 2003, pp. 29–45.

36 Ibid. p. 30.

37 Republic of Chile, 2003, p. 13.

38 Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio de Chile and UNESCO World Heritage.

39 Republic of Chile, 2003, p. 31.

40 Ibid., pp. 54–61.

41 Ibid., pp. 76–80.

42 Ibid., p. 5.

43 ICOMOS, Humberstone and Santa Laura (Chile) No 1178, 2005, p. 194.

44 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Decision 29 COM 8B.52, Inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger (Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works) (2005), UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/517/.

45 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works.

46 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Decision 29 COM 8B.52, Inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger (Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works).

47 UNESCO World Heritage, The Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works Site (Chile), Removed from the List of World Heritage in Danger (2019), UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1997/

48 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Decision 37 COM 7A.37 Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (Chile) (C 1178) (2013), UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/5014/

49 Chilean Government, Ministry of Cultures, Arts and Heritage, ‘Being in Danger, an Honest Way to Safeguard. The Case of Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works’ (presented at the HeRe—Heritage Revivals—Heritage for Peace, Bucharest, Romania, 2019).

50 Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales, Corporación Museo del Salitre, and Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Programa de Intervenciones Prioritarias Para Las Oficinas Salitreras Humberstone y Santa Laura, 2005-2006, 2005, p. 2.

51 Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales, Corporación Museo del Salitre, and Ministerio de Obras Públicas, 2005, pp. 2–3.

52 Ibid.

53 ICOMOS, Joint ICOMOS–TICCIH Principles for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes, 2011, https://www.icomos.org/Paris2011/GA2011_ICOMOS_TICCIH_joint_principles_EN_FR_final_20120110.pdf

54 Neil Cossons, ‘Why Preserve Industrial Heritage’, in Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation, ed. by James Douet (Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited, 2012), pp. 6–16.

55 Capture3DChile, Pulpería de Santiago Humberstone, Corporación Museo del Salitre (2020), MPEmbed.

56 Gobierno de Chile and Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural, Programa de Intervenciones Prioritarias 2005-2018. Sitio de Patrimonio Mundial Oficinas Salitreras Humberstone y Santa Laura (Chile, 2018).

57 Norbert Tempel, ‘Post-Industrial Landscapes’, in Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation, ed. by James Douet (Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited, 2012), pp. 142–49.

58 Iain Stuart, ‘Identifying Industrial Landscapes’, in Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation, ed. by James Douet (Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited, 2012), pp. 48–54.

59 UNESCO, Report of the ICOMOS Advisory Mission to Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (Chile) (1178bis), 2018, p. 23, https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/3883.

60 UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works.

61 Caitlin DeSilvey, Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), p. 32.

62 R. Ortiz and others, ‘Diagnóstico de la Planta de Lixiviación de la oficina Salitrera Santa Laura en Chile. Patrimonio de la Humanidad’, Informes de la Construcción, 67:540 (2015), e115.

63 Michael Emmison and Philip Smith, Researching the Visual: Images, Objects, Contexts and Interactions in Social and Cultural Inquiry (London: SAGE, 2000).

64 DeSilvey, 2017, p. 5.

65 DeSilvey, 2017, pp. 1–21.

66 Cornelius Holtorf, ‘Averting Loss Aversion in Cultural Heritage’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21:4 (2015), 405–21 (p. 418).

67 Thomas Schlereth, ‘Material Culture and Cultural Research’, in Material Culture: A Research Guide, ed. by Thomas Schlereth (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), pp. 1–34 (p. 3).

68 Pierre Nora, ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, 26 (1989), 7–24 (p. 17).

69 Getarq, Planta de Lixiviacion, Salitrera Santa Laura, Patrimonio Accesible,

https://www.getarq.com/tour360/santa_laura/index.htm

70 Recorrido por Humberstone | Colores del norte (2020), Facebook,

https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=692114534918224&ref=watch_permalink