2. Impact of Jurisprudential Heritage in the Organisation of the Medina of Tunis: Joint Ownership, Social Practices and Customs

©2024 Meriem Ben Ammar, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.02

Introduction

Since the beginning of Islam, Islamic law has ordered relations between Muslims and managed their lives, rights and duties. The city as a living environment was organised through numerous rules and laws, based on the Hadith of the prophet Mohammad, which state that harm should neither be inflicted nor reciprocated.

The neighbourhood is an important aspect of Muslim life and a special focus of both the Quran and the Sunnah, which emphasize unity and peace as distinctive elements of the Islamic neighbourhood. Religious tenets include notions of good neighbourliness and various rights and customs governing interactions between residents of the same neighbourhood. As Ali Safak notes, ‘One of the most important of today’s problems [for Muslims], about which questions are frequently asked, is the matter of ownership rights’.1 This will be the subject of the current chapter. From the relationship between neighbours, various types of transactions are generated, such as joint ownership, the object of which can be a shop, land, a house or a contiguous wall, given the anatomy of the Islamic city and the layout of its dwellings.

According to some researchers, shared walls are a characteristic feature of the medina, or old town. Moncef M’halla considers the clustering and connecting of houses to be at the origin of the formation of the medina and its urban fabric, where the wall—as an important architectural element—is akin to its spinal column.2 This feature is absent in contemporary cities, which adopt the European model as a development plan. As Mazzoli-Guintard states, we should not forget ‘that among the remarkable morphological features of the city of the medieval Arab-Muslim world is that of the contiguity of the building’.3 We can observe this omnipresent aspect in the medina of Tunis, registered since 1979 as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site, with its weaving of houses surrounded by mosques, souqs [markets], mausoleums, madrasas [schools], hammams [bathhouses], fondouks [hotels] and so on.

Fig. 2.1 Medina of Tunis, example of a party wall used by one of the neighbours as a support for its construction of an upper floor. Author’s photograph, 2017, CC BY-NC-ND.

According to O’Meara, the city can be defined and determined by its walls. The basic building block was the dar [house], simply a walled enclosure or a cell. Thus, the medina’s structure is defined by the enclosures’ walls that set out and delineate the buildings and the streets.4 Some owners could legally make changes to their private properties (extension, restoration, demolition, reconstruction of walls, etc.), but sometimes owners did so illegally, violating the regulating code of the medina5 and disrupting the neighbourhood’s harmony (Fig. 2.1).

To minimise the incidents and injustices caused by joint ownership and establish a legal framework to resolve these conflicts, Islamic jurisprudence sets out several rules that take into account social practices, relations between neighbours, construction techniques and materials. These long-established rules have since become customs. They were written by jurists, judges or even masons in the form of books or epistles under the heading ‘Jurisprudence of Architecture and Urbanism’ and are dedicated to discussing problems related to construction techniques and materials, neighbourhood conflicts, roads, town planning, lighting and so on.6

The study of the rules transmitted from one generation to another, here analysed and interpreted in a graphical way, constitutes a fundamental contribution to the knowledge of the structure of the contemporary Islamic city; it can be useful for the assessment of contemporary tangible heritage, and therefore, for making decisions regarding the protection and enhancement of the built environment in the light of tradition.

State of studies on Islamic urban planning

Since Islamic jurisprudence manages both religious and temporal aspects of believers’ lives, it practically regulates all areas of existence. ‘Jurisprudence of Architecture and Urbanism’ can be defined as the set of rules and recommendations prescribed by Islamic law that govern everything related to architecture, town planning and the development of an Islamic city. It can also be considered a group of principles derived from the urban movement and its interaction with society. It provides answers to the Muslim community’s concerns while respecting the interests of the individual and the public. These responses subsequently provide a reference for any problematic situation as well as a legally binding framework. The need for a legal guide has given rise to works and treatises that can be employed and developed according to rite, space and need.

Early research on the Islamic city was characterized by homogeneity, thanks to a structural model that was applied to all cities without taking into account the geographical, economic, social, and historical characteristics of each region.7 Efforts have been made to revise this approach that account for these factors, as well as distinguishing towns from rural settlements. Giulia A. Neglia noted that, after 1970, studies have been oriented towards the role of religion in the codification of Islamic urban form and society, or on the structure of cities in different regions.8

The Islamic city with all its components is not the result of a singular generative mechanism, but a multidisciplinary process based on various parameters: legal, religious, political and cultural.9 Dating from the eighteenth century, the book An Epistle on Disputed Contiguous Walls by Tunisian jurist Muhammad bin Hussain al-Baroudi al-Hanafi (d. 1801) focuses on cases of neighbourhood conflicts, using the provisions set out in the treaties of Hanafi law as a reference. This manuscript is devoted exclusively to neighbourhood conflicts, unlike previous works which have addressed this issue along with many other subjects, such as water, streets, impasses, and public and private property. The jurist tried to collect and cite all the rules relating to these conflicts, while providing accompanying commentary. Despite the rich potential of this legal literature, it has only been treated with minimal interest.10 It is true that numerous manuscripts were transcribed, but this chapter is interested in analytical works focused on the study of sources of legislation related to the city and its architecture. More contemporary academic studies of this literature on Islamic law presented elements drawn from work on jurisprudence and the various questions relating to urbanism dealt with by Maliki jurists. They tried to show how religious laws and ethical values have been central to the creation and development of the city over time.11 In examining the subject from various levels of analysis—from the city to the Muslim world,12 and back to the neighbourhood—the contemporary academic study sheds light on the relationships between society, religion, and the construction of urban and architectural practices. This is done in an effort to demonstrate the application of the Islamic foundations in urban planning, and to explain how Islamic thought has affected urban strategy, roads, infrastructure, politics and social life.13More contemporary academic studies offering a new reading of the Maliki and Hanafi legal sources endeavour to understand the genesis of the medina by emphasising the role of the wall and the rules of the contiguity between joint ownership and donation of the wall. These are an attempt to find a link between Islamic legal techniques and modern cities by exploring how these sources can help to understand and solve present-day urban problems through emphasis on the phenomenon of contiguity.14

Presentation of the Epistle

Two copies of the Epistle were found at the National Library of Tunis; their characteristics are listed in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Characteristics of the two copies of the Epistle.

|

Nature |

||

|

Number |

09732 |

03933 |

|

State |

Draft |

Final copy |

|

Source |

Collection of legal questions (a set of 123 folio) |

Independent booklet |

|

Owner |

||

|

Number of sheets |

16 (from folio 32 to folio 47) |

18 |

|

Date of writing |

End of Shaaban in the year 1215H (January 1801) |

Tuesday 9 dhu al-Qa’da in the year 1215H (23 March 1801) |

|

Dimensions (cm) |

20.8 * 15 |

21 * 15 |

|

Writing |

||

|

Ink |

Black |

Black |

|

Support quality |

||

|

Binding |

||

The jurist, his approach and his sources

The jurist was descended from a family of Turkish scholars originally from Morea in Greece. His grandfather, Ibrahim al-Baroudi, a janissary specialist in the manufacture of gunpowder, arrived and settled in Tunis towards the end of the seventeenth century. His father was Hussain bin Ibrahim al-Baroudi (1700–1773), a renowned Hanafi jurist and theologian who held several important positions in the Tunisian Beylic. Muhammad bin Hussain bin Ibrahim al-Baroudi also became a renowned Hanafi jurist. He worked as a teacher at the great mosque and at al-Chammaiya Madrasah. In 1776, Ali Bey (1712–1782) appointed him as the third Hanafi mufti, and in 1780, he became imam and teacher at the Hammouda pasha mosque. He gained remarkable status under the rule of Hammouda pasha (1759–1814), including the title of Cheikh al-Islam, which he received around 1799 and held until his death in 1801.15

The text16 is presented in a progressive manner with the absence of the classic layout of jurisprudence manuscripts (introduction, sections and chapters). Al-Baroudi starts by introducing the topic of neighbourhood conflicts, expressing his interest in this problem and encouraging jurists to pay special attention to it. We can discern the various cases of conflict thanks to his descriptive writing, which uses an informative tone and a hypothetical style to describe certain situations and enumerate their relative causes, the conditions and the different states on either side of the wall—each neighbour’s property, the state of his walls, the roof, its composition, and the construction technique. Finally, Al-Baroudi presents the most suitable solution, accompanied by references from legal sources to support the judgement.

Throughout the manuscript, and to consolidate his opinions, Al-Baroudi mentions various sources that belong to the Hanafi rite. These include the works of the founder of the doctrine, Abu Hanifa, and his student and companion, Abu Yousuf. Two other works were mentioned several times—the Imadian Decisive Arbiter,17 described as a valuable and comprehensive collection of all legal matters, and Fatawa Qadi Khan,18 one of the most approved, widely known and ubiquitous Fatwah books among Hanafi jurists. Other than the general Fiqh,19 Al-Baroudi relies on the most famous book of the Hanafi school on architecture and urbanism, the Book of the Walls.20 This book covers a variety of issues related to shared walls—the right of use, connections between buildings, roofing, common ownership of a party wall, connected and raised beams, wall arrangements in the case of conflicts and multi-storey buildings, as well as issues relating to streets, water canals, irrigation and so on.

Cases of neighbourhood conflict

Al-Baroudi addresses the reader directly, informing them of disagreements between two neighbours concerning a contiguous wall where each claims ownership but without proof or avowal. The cases are grouped into two main categories, the first where the two contestants are equal in their pleas and neither has a valid argument that favours one person or side over the other. The second category includes cases where one or both parties have a reason that supports their claim.

Division criteria

Types of connection

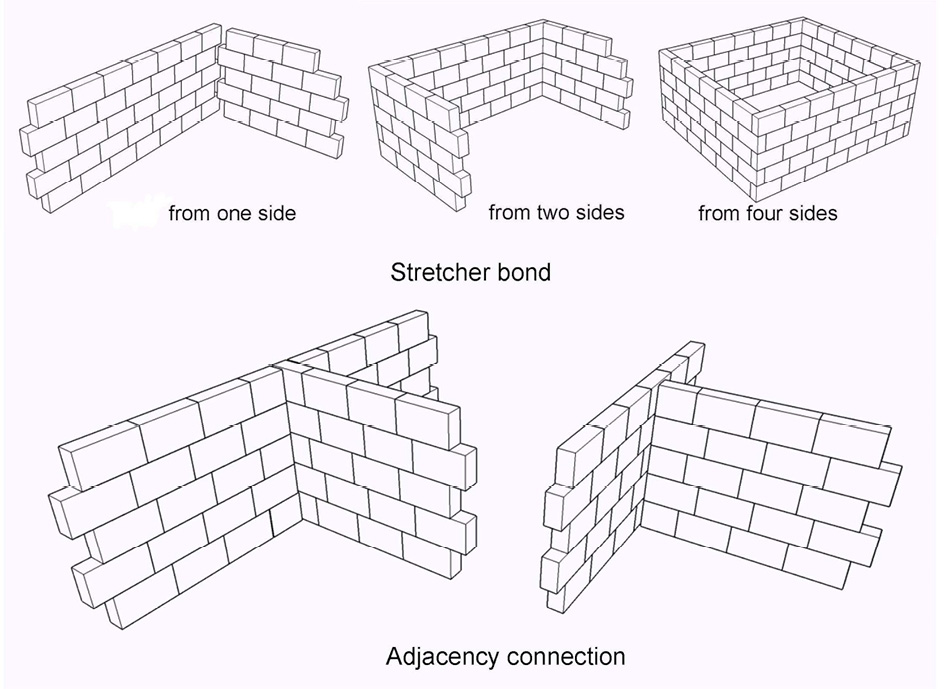

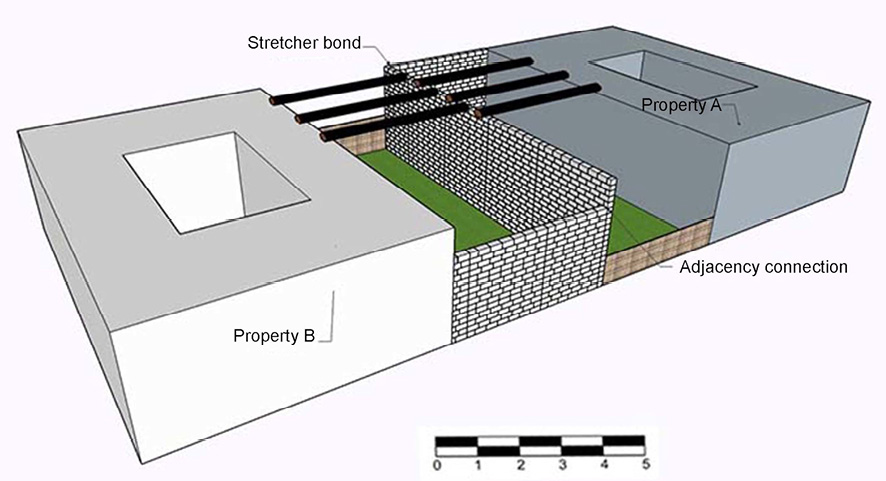

Al-Baroudi mentions two types of connection: a stretcher bond and an adjacency connection. The first is defined as the connection between the contested wall and another orthogonal one so that its masonry blocks overlap with those of the other. This is called squaring because it is built to form a square space with two other walls.

According to Al-Baroudi, if the construction is made of stone or brick, the half-blocks of the contested wall are interwoven with the half-blocks of the uncontested orthogonal wall, and if it is made of wood, each bar is inserted into the orthogonal wall (Fig. 2.2).21 The second type of construction is the juxtaposition of two walls without overlapping, also called contiguity. According to jurists, this is a simple juxtaposition of two walls, without interference or sharing, and the neighbours each occupy and operate their building (Fig. 2.2).

Fig. 2.2 Types of stretcher bond and adjacency connection. Author’s illustration, CC BY-NC-ND.

The method of use

The wall is presented as a partition wall between two distinct properties. It is a dividing wall commonly referred to as a contiguous wall. Al-Baroudi explains that it can be built in masonry composed of blocks of cohesive and viscous clay (that is, not mixed with sand), bricks, or even wood. He insists that the wall is only built to support the floor by sustaining its beams (palm trunks) and cannot be built to provide shade.

Precedence

An important criterion in determining the owner of the wall is distinguishing the person who has precedence in terms of use. This person has the right of ownership of the wall. Precedence is in the order of priority; in Islamic law, anything old corresponding to the law must be left intact unless there is evidence to the contrary because the persistence of something for a long time is proof that it is legitimate.22 This criterion is also used in determining easements, the rights of the road, the right to water and so on.

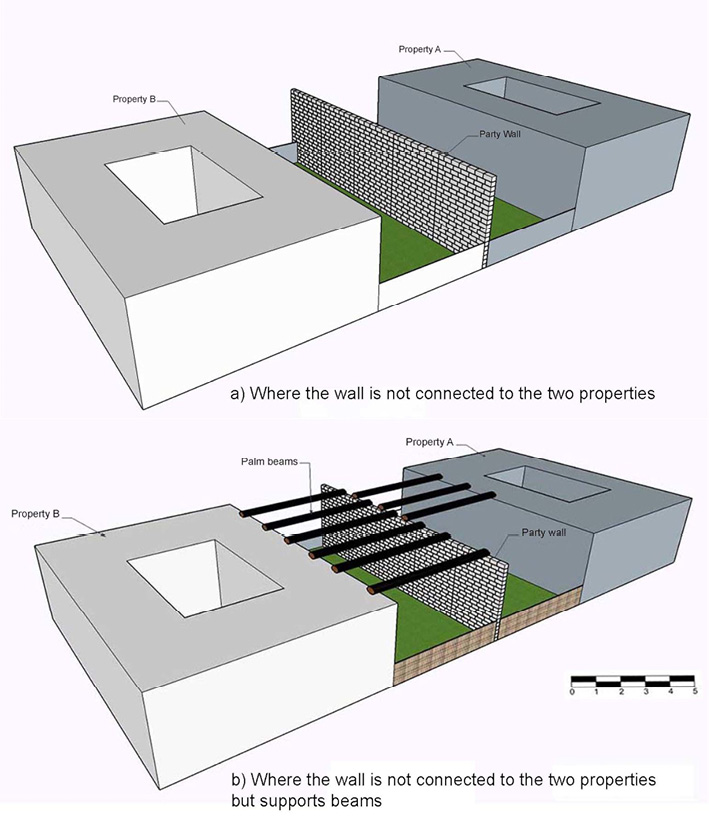

Contiguous properties without tangible connection

Contiguous properties without concrete connection can be defined as a situation where the only connections between two contiguous properties are the neighbourhood and the party wall. The party wall can be the subject of a dispute between the owners of the two properties that adjoin it, especially in the absence of a proof of ownership or a declaration of non-ownership, or a recognition or cause of preference. There are two types of case described. The first is where the wall is not connected to the two properties either by a stretcher bond or by an adjacency connection and does not support palm beams. At this point, the wall must be divided between the two neighbours identically and with abandonment of cause (Fig. 2.3a).23 The second case predicts that, despite the discontinuity between the wall and the two neighbouring properties, there are beams supported by the wall that belong to the two parties. In this case, the situation is divided into several sub-cases (Fig. 2.3b).

If there is an equal number of beams on both sides, the wall is a common possession. Otherwise, if owner A has a beam placed higher than that of owner B, the latter would have ownership of the wall since he enjoys the right of precedence while maintaining A’s beams on the condition that they do not damage the wall. If the beams are at the same height, there are three possibilities.

Firstly, each has three or more beams; the wall is a common possession; the abundance of beams does not change anything; and the two are equal in the mode of use since the wall is built to support the floor, which requires at least three beams.

Secondly, A has three beams and B has two. It could be that the wall is a common property; alternatively, it may simply be attributed to owner A. According to Al-Baroudi, the latter opinion is most suitable, considering the role of the wall as a support for the roof.

Fig. 2.3 Cases of contiguous properties without concrete connection. Author’s illustration, CC BY-NC-ND.

Thirdly, A has three beams and B has only one. Al-Baroudi decides that the wall must be attributed to A but without removing the beams of B.24 He also raises the question about the void above the wall attributed to A, since A already enjoys property rights to the wall, whereas B only has the right to support his beams.

Connection between the wall and adjacent buildings

A connection between the wall and adjacent buildings is characterised by the presence of a connection between the party wall and the two adjoining constructions, as well as several arguments that favour one side over the other. In fact, there are two conditions—either the wall is connected to the two parties’ homes, or it is only connected to a single neighbour’s dwelling. Several cases are distinguished for each situation.

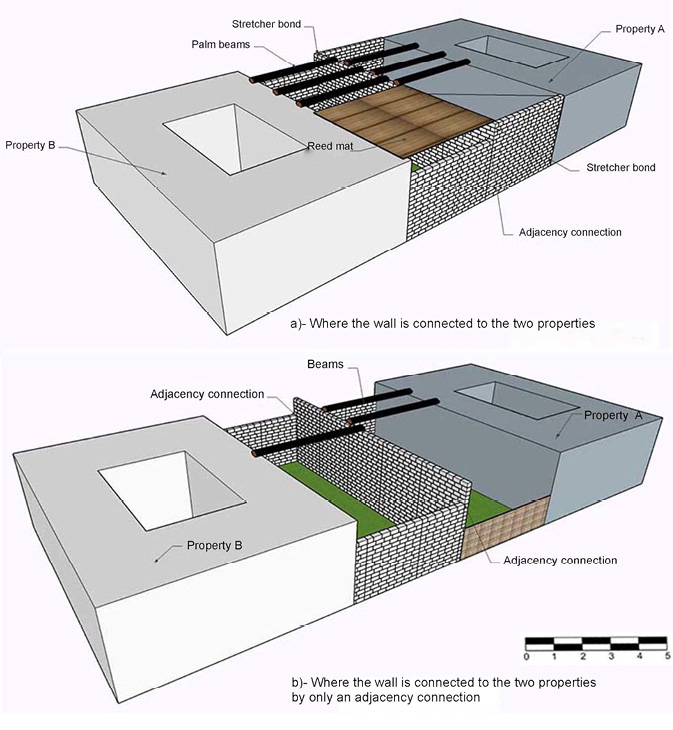

The wall is connected to the two neighbouring houses

The first such case is if the wall is connected to the two houses on one, two or four sides by a stretcher bond or an adjacency connection without beams. Only one side is enough to confirm the liaison; therefore, the party wall is considered common property (Fig. 2.4a).

Fig. 2.4 Cases of connection to the two properties. Author’s illustration, CC BY-NC-ND.

If the wall is connected to the two houses by a stretcher bond and only one of the two parties has beams hanging on it, the one that has the link has priority. However, if the wall is connected to both houses and each of them has beams placed on it, it will be divided evenly between them for equality of cause and confirmation of the use of the wall by both. It is also assigned to both evenly when the party wall is linked to A by a stretcher bond on one side and to B from two sides.

If the wall is connected to one property by a stretcher bond, while in the other property we find a reed mat placed on the wall for shade, ownership is then attributed to the stretcher bond holder because the presence or absence of the reed mat is equal and does not change anything. The party wall and the two houses are linked by an adjacency connection: if we find the same number of beams placed on either side, the wall is a common property of the two contestants. If the number is different, the judgement is made according to the basis of the three beams. If only one has beams, then he is the owner of the wall (Fig. 2.4b).

The wall is linked to a single property

If the party wall is linked to neighbour A by a stretcher bond from the four corners,25 while A or B has beams, the wall ownership goes to the holder of the bond. If the wall is linked to A by an adjacency connection, while B has beams, the wall then reverts to B’s ownership. However, if these beams belong to A, then the wall belongs to A absolutely (Fig. 2.5).

If the wall is linked to A by a stretcher bond and by an adjacency connection to B, the former has the right to the wall.

Fig. 2.5 Where the wall is connected to only one of the properties either by adjacency connection or stretcher bond. Author’s illustration, CC BY-NC-ND.

Utility of jurisprudence heritage in the management of the medina

From this analysis, it can be seen that certain distinctive elements of the neighbourhood and party wall relationships could be beneficial to resolve current joint ownership and neighbourhood conflicts, or to help during the restoration phase. These are: the construction of storeys; the loan of the wall by its owner to the neighbour; an extension on the empty space of the adjacent street; the permitted height of the construction; the determination of the real owner of the wall; the mode, techniques and materials of construction used; the presence and number of beams; the existence of an opening; and the criterion of precedence. Based on observation and direct inspection of the building for a fair and equitable judgement: the party wall is a structural element whose only role is to lift and support the roof. An essential criterion in determining its owner is the inspection of the type of use, its nature, and its date. The person with precedent takes priority, especially when they have built something; this is a strongly endorsed argument.

A stretcher bond is a finished construction; therefore, the presence of a stretcher bond is considered valid evidence of the laying of the beams since the former preceded the latter. When beams are set on the wall, this is an act of preparation to build a roof, so it is more valuable than an adjacency connection. Assigning the wall to one of the neighbours does not give the neighbour the right to remove what the other has in terms of beams, parapets or reed mats on the wall. The person can continue to use it as long as it does not cause damage to the neighbour’s property.

For jurists, the principles of not causing damage and helping neighbours were the main guides to regulate these relationships and resolve any conflict. Evolving over time and in relation to the requirements and nature of Islamic cities, several legal rules and behaviours developed over time, such as those mentioned in the Epistle.

Resolving wall conflicts requires a thorough knowledge of construction issues and their technology, which confirms the jurist’s ability and legal and architectural knowledge. In general, this allowed jurists to carry out the task of controlling and organising the urban fabric of the medina of Tunis in the absence of the municipality at that time, given the fact that the first municipality was founded in Tunis in 1858. They based their task on the customary law, which examined the connection between the party wall and its surroundings.

The customary techniques and building materials used in this space, relating to the architectural culture passed down from one generation to another, have the potential to solve a variety of disputes between neighbours. While these rules have been passed down orally, this does not exclude the possibility that they may have been written down at some point in time, a supposition justified by the mention of several references that go back to the basis of the Hanafi doctrine. It also shows the evolving and flexible nature of Hanafi jurisprudence, allowing it to adapt to any period and situation as long as the public and private benefit is guaranteed. Although the regency had a Malikite majority, the Hanafi rite was used because Hanafi governance was in place, with seemingly clear influence at the level of the mosques and mausoleums, as well as at the level of the medina. Ibn Abi Dhiaf said that during the reign of Hammouda Pacha Bey (1759-1814), people eagerly moved towards agriculture, commerce and industries and the country experienced urban development, financial prosperity and wealth under some Ottoman rulers,26 with urban extensions and constructions of new dwellings in the suburbs that potentially caused neighbourhhood conflicts requiring resolution. Even today, these customs continue to exist and operate in a tacit way but are recognised between neighbours (they include the customs of privacy, the prohibition of looking into your neighbour’s house, the prohibition of illegal occupation of the street, restrictions on heights of buildings, etc.). This is true not only in the medinas (Tunis, Kairouan, Sousse, etc.) but also in new cities built since the 1980s with a similar (or even a different) configuration where the houses are isolated.

Hanafi jurisprudence largely inspired the Ottoman Urbanism Code called Madjallah,27 which ceased to function after the Westernisation of Ottoman law. Following their colonisation28, the Maghreb countries, including Tunisia, adopted the European model of development, which involved an urban planning code. As Houcine has shown, technical and material innovations pursued by most of the provincial cities, especially the Maghreb cities and medinas, have always been accompanied by recourse to European laws and the abandonment of Islamic ones, which are better suited to Muslim life and spatial practices, especially in terms of contiguity and joint ownership.29 Not only are these regulations able to resolve conflict issues, but they are also fundamental to understanding the traditional basis of the rules of neighbourhood conviviality in the whole medina. As Houcine notes, ‘We have continued to adopt Western planning laws and instruments, without worrying about their inadequacies to the socio-cultural realities of Muslim nations’.30

According to Van Staëvel, by analysing the normative legal discourse devoted to the property regime, it becomes possible to outline some of the particular features of social practices and representations of space, both domestic and urban, in cities of the medieval Muslim Occident.31

European laws have failed to protect medinas from vandalism and the loss of homogeneity and uniformity.32 With this study, we have aimed to demonstrate the utility of Islamic jurisprudence in future reforms of the legislation regulating Tunisian medinas, which are the subject of continual debates regarding the conservation and preservation of their identity. It is essential to understand the reasoning behind their creation and to consider the Islamic architectural and urban law in future processes of urban redevelopment. The medina is a historical urban space with a long and complex tradition. Its efficient management requires a functional grasp of the principles and urban standards inspired by the ancient rules that historically generated and organised the medina.

The persistence of the medina’s urban fabric reflects the area’s history and suggests that these legal rules have proven their effectiveness. Many issues related to housing, property and joint ownership remain largely unchanged over time. Today, despite the presence of the relevant authorities and the Urban Code, transgressions are prevalent in the old cities and have no deterrents or solutions.

The manuscript An Epistle on Disputed Contiguous Walls, and the study of ancient jurisprudence in general, is useful to understand the laws governing the medina. A broader and more comprehensive look at this set of rules makes it possible to discern the vitality and complexity of the building processes of the past and to link them to the present. In this way, we can better understand which practices are best suited to preserve the architectural and urban heritage of spaces in historic centres, and what rules to apply to respect private and public property, especially the quality of the places in which we live. The past offers valuable insights for finding solutions in the present.

Conclusion

The interest of studying Muslim legal manuscripts lies in understanding the mechanisms of city formation through the discernment of social practices and constructive and legal customs that have persisted because of their effectiveness. This has created an opportunity to clarify, via the study of neighbourhood relationships, the mechanisms and parameters responsible for the functioning of the medina before the municipality (founded in 1858 in Tunis) replaced jurists, qadis and guilds. It is an attempt to determine their role and to understand how citizens shaped their living environment.

This study does not advocate the adoption of these manuscripts as a code of urbanism, but rather highlights their utility in resolving urban problems, many of which remain largely similar despite population growth and the evolution of needs, techniques and building materials. Such manuscripts thus provide valuable references for those developing the new rules governing the medina, but are nevertheless often considered outdated, and as such, neglected. By demonstrating their relevance, this study seeks to reverse this trend and encourage researchers to study them.

Though often overlooked, current practices of joint ownership constitute an important aspect of legal and cultural heritage, which can be observed in the urban fabric of the medina, where they continue to be functional despite the changes that have occurred over time. The restoration of some districts like the Hafsia Quarter have been undertaken in the image of the existing urban fabric, benefiting from elements discussed by Islamic laws—height restrictions, houses with courtyards, the prohibition of the obstruction of the street, non-opposing doors, respect for one’s neighbour and so on. Throughout history, these laws have proven their effectiveness and adaptability, in addition to being a significant element of cultural and intellectual heritage. For these reasons, they must be preserved and incorporated into modern codes and laws.

Bibliography

Abdelmalek, Houcine, ‘La mitoyenneté dans la jurisprudence islamique’, Tracé (bulletin technique de la Suisse romande), 1 (2011), 6–15.

Akbar, Jamel, A Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1988).

Al-Baroudi, Muhammad bin Hussain bin Ibrahim, Risālat Fatḥ al-Raḥman fī mas’lat al-Tanāz’u fī al-ḥitān [Epistle on Disputed Contiguous Walls], Tunis, National Library, MS 03933, MS 09732.

Azab, Khaled, Fiqh al-’imāra al-Islāmiyya [Islamic Jurisprudence of Architecture] (Egypt: University Publishing House, 1997).

Hakim, Besim Selim, Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles (New York: Routledge, 2010).

Jayyusi, Salma K., Holod, Renata, Petruccioli, Attilio, and Raymond, André, eds., The City in the Islamic World (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2008).

M’halla, Moncef, ‘La médina un art de bâtir’, Africa (Institut national du patrimoine de Tunis), 12 (1998), 33–98, https://www.inp2020.tn/periodiques/atp/atp12.pdf

Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine, Vivre à Cordoue au Moyen Âge: Solidarités citadines en terre d’Islam aux Xe-XIe siècles (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2003), https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.17013

O’Meara, Simon, ‘A Legal Aesthetic of Medieval and Pre-Modern Arab Muslim Urban Architectural Space’, Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 9 (2009), 1–17, https://doi.org/10.5617/jais.4594

Robert Brunschvig, ‘Urbanisme médiéval et droit musulman’, Revue des études islamiques, XV (1947), 127–55.

Safak, Ali, ‘Urbanism and Family Residence in Islamic law’, Ekistics, 280 (1980), 21–25.

Uthman, Muhammad Abd al-Sattar, Al-Madīna al-Islāmiyya [The Islamic City] (Cairo: Dar al-Afaq al-Arabiyah, 1999).

Van Staëvel, Jean Pierre, Droit mālikite et habitat à Tunis au XIVe siècle. Conflits de voisinage et normes juridiques d’après le texte du maître-maçon Ibn al-Rāmī (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie, 2008).

1 Ali Safak, ‘Urbanism and Family Residence in Islamic Law’, Ekistics, 280 (1980), 21–25 (p. 21).

2 Moncef M’halla, ‘La médina un art de bâtir’, Africa: Fouilles, monuments et collections archéologiques en Tunisie, Institut national du patrimoine de Tunis, 12 (1998), 33–98 (see esp. p. 44, pp. 53–54), https://www.inp2020.tn/periodiques/atp/atp12.pdf

3 Christine Mazzoli Guintard, Vivre à Cordoue au Moyen Âge: Solidarités citadines en terre d’Islam aux Xe-XIe siècles (Rennes: Presses universitaires, 2015), p. 163, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.17013

4 Simon O’Meara, Space and Muslim Urban Life: At the Limits of the Labyrinth of Fez (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 15.

5 Plan d’aménagement urbain de la commune de Tunis, Règlement d’urbanisme [Urban development plan for the municipality of Tunis] (Commune-Tunis, January 2016), pp. 31–33, http://www.commune-tunis.gov.tn/publish/images/actualite/pdf/Reg-PACT-livre-enq%20publiqueh.pdf

The urban planning rules relating to the medina of Tunis occupy a chapter in this code, which presents the characteristics of the medina as a residential, economic real-estate space and monumental heritage with safeguarding standards.

6 Several classical books have been written in this field, such as the following (the titles of these books and of the epistle studied in this chapter have been translated from the Arabic by the present author): Issa bin Moussa al-Toutili, The Book of the Wall (tenth century); Al-Mourji al-Thaqafi, The Book of the Walls (tenth century); Al-Fursutaai al-Nafoussi, The Book of the Division and the Origins of the Lands (twelfth century); and The Book of Advertisement of Judicial Provisions of Buildings (fourteenth century) by the Tunisian mason Ibn al-Rami.

7 Henri Pirenne, Les villes du moyen âge (Brussels: Lamertin, 1927); Georges Marçais, ‘L’urbanisme musulman’, in 5e Congrès De la Fédération des Soc. Savantes d’Afrique du Nord, Tunis, 6–8.4.1939 (Algiers, 1940), 13–34; Georges Marçais, ‘La conception des villes dans l’Islâm’, Revue d’Alger, 2 (1945), 517–33.

8 Giulia Annalinda Neglia, ‘Some historiographical notes on the Islamic city with particular reference to the visual representation of the built city’, in The City in the Islamic World, ed. by Salma K. Jayyusi, Renata Holod, Attilio Petruccioli and André Raymond (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2008), pp. 3–46 (p.13).

9 The Islamic City: A Colloquium, ed. by Albert Habib Hourani and Samuel Miklos Stern (Oxford: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970); Islamic Architecture and Urbanism, ed. by Aydin Germen (Dammam: King Faisal University, 1983); The Middle East City: Ancient Traditions Confront a Modern World, ed. by Abdelaziz Y. Saqqaf (New York: Paragon House, 1987); Janet L. Abu-Lughod, ‘The Islamic City: Historic Myth, Islamic Essence, and Contemporary Relevance’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 2 (1987), 155–76.

10 To the best of the author’s knowledge, unlike other manuscripts of architectural and urban planning jurisprudence, this epistle has not been analysed. The epistle has been consulted at the National Library of Tunis, in the form of a manuscript dating from the 18th century.

11 Robert Brunschvig, ‘Urbanisme médiéval et droit musulman’, Revue des études islamiques, XV (1947), 127–55; Besim Selim Hakim, Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles (New York: Routledge, 2010); Jean-Pierre Van Staëvel, Droit mālikite et habitat à Tunis au XIVe siècle. Conflits de voisinage et normes juridiques d’après le texte du maître-maçon Ibn al-Rāmī (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie, 2008).

12 Jamel Akbar, A Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1988).

13 Khaled Azab, Fiqh al-ʿimāra al-Islāmiyya [Islamic Jurisprudence of Architecture] (Egypt: University Publishing House, 1997); Muhammad Abd al-Sattar Uthman, Al-Madīna al-Islāmiyya [The Islamic City] (Cairo: Dar al-Afaq al-Arabiyah, 1999).

14 Moncef M’halla, ‘La médina un art de bâtir’, Africa: Fouilles, monuments et collections archéologiques en Tunisie, Institut national du patrimoine de Tunis, 12 (1998), 33–98; Abdelmalek Houcine, ‘La mitoyenneté dans la jurisprudence islamique’, Tracé (bulletin technique de la Suisse romande), 1 (2011), 6–15; Simon O’Meara, ‘A Legal Aesthetic of Medieval and Pre-Modern Arab Muslim Urban Architectural Space’, Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 9 (2009), 1–17, https://doi.org/10.5617/jais.4594

15 Hassan Hosni Abdelwaheb, Kitāb al-ʿumr fil-muṣannafāt wal-muʾallifīn al-tunisiyyīn [A Book on Tunisian Works and Authors], 2 vols. (Tunis: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 1990), I, p. 930; Muhammad Mahfûz, Tarājim al- muʾallifīn al-tunisiyyīn [Biographies of Tunisian Authors], 5 vols. (Tunis: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 1994), I, p. 74; Muhammad al-Snussi, Musāmarāt al-dharīf bi ḥusn al-taʿrīf [Biographies of Tunisian authors], ed. by Muhammad al-Chadli al-Nayfir, 4 vols. (Tunis: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 1994), II, p. 40.

16 In general, the Arabic is fluent and understandable; the text is rich in technical and legal terminology, but the jurist has provided definitions for difficult terms.

17 Al-Imad Abu al-Fath Zainuddin Abd al-Rahimbin Abi Bakr Al-Marghinani (d. 670 C.E), Al-Fuṣūl al-ʿimādiyyah [The Imadian Decisive Arbiter] in Yahya Mohammad Melhem, The Imadian Decisive Arbiter (Jordan: The University of Jordan, 1997).

18 Fakhr al-Din QadiKhan al-Hanafi (d. 592/1195), Fatāwā Qādhī Khān [Legal opinions of Qadikhan] (Mohamed Shahin Press, 1865).

19 Fiqh refers to Islamic jurisprudence and can be characterized as the means by which legal scholars extract guidelines, rules, and regulations from the foundational principles found in the Quran and the Sunnah.

20 The copy used here is not that of al-Thaqafi (see note 6) but that of the Hanafi jurist and judge Omar bin Abd al-Aziz bin Maza al-Bukhari (1090–1141). Al-Baroudi mentioned his recourse to this jurist and his work, which could be explained by the fact that Ibn Maza’s copy contained the complete, annotated version of the book.

21 The jurist explained how the construction material is laid in the case of a stretcher bond connection. Only the blocks’ stretchers are visible, designated by the term ‘half-blocks’; they are linked to the opposite wall by interweaving.

22 Ali Haydar, Durar al-ḥukkām šarḥ majallat al-aḥkām [Explanation of the Journal of Provisions], 4 vols. (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub Al-Ilmiyyah, 2018), I, p. 19.

23 This is reported in the text as a judgment that leaves things as they are, which means that the object of the conflict is to be left in the hands of the owner of the land. See Badr al-Din al-Aini, Al-Bināya fī šarḥ al-hidāya [Explanation of the Guidance], 13 vols. (Beirut: House of Scientific Books, 2000), XII, p. 309; Hervé Bleuchot, Droit musulman, 2 vols. (Marseille: Presses Universitaires d’Aix-Marseille, 2015), II, p. 470. The judge can prevent the plaintiff from going on with the trial, such as by instructing him: ‘You have no right’ or ‘you are forbidden to claim’ (Ali Haidar, Explanation of the Journal of Provisions, IV, p. 573).

24 This is justified in that it is a judgment of an argument or a right to exception, a judgment based on the examination of the wall’s situation and not for cancellation or revocation.

25 The contested wall’s masonry is linked by overlap to two other orthogonal walls, which are linked to a fourth wall.

26 Ibn Abi Dhiyaf, Itḥāf ahl al-zamān bi akhbār mulūk Tūnis wa ʿahd al-amān [Present of the Men of our Time. Chronicles of the Kings of Tunis and the Fundamental Pact], 8 vols., ed. by the Commission of Inquiry of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs (Tunis: Arabic House of the Book, 1999), III, p. 78.

27 This code was promulgated in 1882 by the Ottoman Empire as urban Islamic law.

28 Starting with the colonisation of Algeria in 1830, Tunisia in 1881and Libya in 1911.

29 This has included even harmful redevelopment operations in historic centres, namely the ‘éventrement’ or demolition of cul-de-sacs to control and connect the old and new cities (Tlemcen, Constantine and Tunis, with an unfinished project from 1957 providing for the opening of the medina by a boulevard connecting Bourguiba Street to the Kasbah district).

30 Abdelmalek Houcine, ‘La mitoyenneté dans la jurisprudence islamique’, Tracé (bulletin technique de la Suisse romande), 1 (2011), 6–15 (p. 7).

31 Van Staëvel, Droit mālikite et habitat à Tunis au XIVe siècle, pp. 10–11.

32 The urban planning regulations of the Urban Development Plan of the Municipality of Tunis insist on respecting the medina as an important piece of heritage and maintaining the standards that regulate it: preservation of volumetric homogeneity, a fixed height, lighting thanks to the interior courtyard, etc. Despite the existence of this code, violations are observed in some neighbourhoods, including height overruns, volumetric breaks, pollution, graffiti, etc.