3. Revisiting Definitions and Challenges of Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Case of the Old Centre of Mashhad

©2024 Shahamati, Khaleghi & Norouzi, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.03

Introduction

Urban areas are currently facing powerful processes of change and transformation. The rising challenges of the twenty-first century, such as the exponential increase in urbanisation and the growing number of urban development projects, globalisation and its homogenisation processes, and the changing role of cities as drivers of economic activity and development, have had major impacts on the physical and social character of cities. Such processes are continuously reshaping urban areas and have led to numerous threats to cultural diversity and pluralism.1

Because of these growing threats, safeguarding the identity and diversity of communities and urban areas has been identified as a matter of emergency by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in the last three decades.2 This in turn has given rise to various charters and conventions3 which not only provide guidelines and policies for protecting the identity of communities, but encompass a more universally accepted understanding of heritage and its complexities. As a result, heritage has come to be conceptualised globally based not only on its tangible and monumental forms, but also its humanistic value.4

Based on UNESCO’s definition, cultural heritage consists of both tangible and intangible assets. Tangible heritage includes monuments, artefacts and the built environment, while intangible heritage is characterised as an invisible dimension5 which can take the form of songs, myths, beliefs, superstitions, oral poetry, memories, performing arts and other types of social practices. Because intangible heritage is often deeply connected to collective identities and a sense of place,6 it is an important aspect of safeguarding cultural diversity in cities that are increasingly threatened by globalisation and its homogenising processes.7 Although the recognition of the intangible dimensions of culture has heightened the attention given to cultural diversity and social values, there are still various challenges to achieving a more comprehensive understanding of such values in cities. UNESCO recognised intangible heritage via an official nomination and recognition process based on specific criteria.8 Yet, most of the invisible assets of local areas face difficulties in being recognised through such processes.

With the current emphasis on measurable and quantifiable aspects of cities in urban planning practice and research, the marginalisation of the ‘soft’ and subjective elements that are otherwise known as intangible is inevitable.9 The importance placed on measurable features of urban areas has led to decisions that prioritise the values of the built environment at the dire expense of the social environment. Relevant examples of such decisions can be seen in various urban redevelopment projects that have resulted in the displacement of residents through the gentrification process or forced eviction.10

Urban interventions have contributed to the modification of the urban fabric without considering the accumulated identity of places and their cultural, social and historical complexities. Even when mainstream planning practices acknowledge cultural heritage, they tend to be limited to what is embedded in the built environment. Cultural maps designed for planning purposes are systematically limited to sites, monuments and buildings that can be precisely pinpointed in the physical environment, while dismissing any intangible dimensions that cannot be easily measured or clearly circumscribed spatially.11 These maps contribute to the erasure of intangible heritage in our collective memories. Because of its invisible nature, these intangible dimensions are often in danger of disappearance and destruction. This problem is heightened in historic towns or boroughs built on intangible values.

To investigate this subject in greater depth, this chapter looks at a historic city built on intangible values—the city of Mashhad in northeast Iran. With a population of roughly three million people, Mashhad is the second largest city in the country after Tehran, and has been built around a holy shrine for Shia Muslims. The Holy Shrine has historically determined the socio-economic conditions of the city as well as its architectural emphasis on religious values, such as humbleness. The story of Mashhad shows that intangible values that have survived for centuries are now endangered by the growing threats of globalisation and urban revitalisation. In focusing on this story, this chapter highlights the importance of reconceptualising intangible heritage not only in international charters but also in research and practice. This study seeks a reconceptualisation of cultural heritage that can lead to more innovative and concrete ways of integrating these assets in decision making.

Redefining intangible heritage

UNESCO has played a leading role in heightening the level of global attention paid to the intangible dimension of culture. UNESCO’s approach to intangible cultural heritage is rooted primarily in the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003), followed by the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005).12 Even before the 2003 Convention, UNESCO initiated other activities for promoting intangible cultural heritage worldwide, including the Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore (1989), the Living Human Treasure System (1993) and the Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humans (1998).13

The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) was a decisive point in the conceptual understanding of intangible heritage. It reflected the efforts made by the international community to define intangible heritage and provided a series of recommendations for safeguarding these assets against deterioration and disappearance. Based on the definition of the Convention, intangible cultural heritage includes oral traditions, languages, performing arts, social practices, traditional knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe, as well as traditional artisanship.14 More specifically, Article 2.1 of the Convention defines ‘intangible cultural heritage’ as the ‘practices, representations, expressions and skills as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated with communities and groups that are constantly being recreated by communities in response to their environment and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity’.15

UNESCO’s definition of intangible heritage laid the groundwork for a better understanding of this concept, providing a comprehensive conceptualization of its meaning and an enumeration of its different forms and representations. However, this approach to intangible cultural heritage has also been met with a range of criticisms. One major criticism of this Convention and of UNESCO’s approach relates to the use of lists and inventories for identifying, recognising and valorising cultural traditions and dividing them into material and immaterial traditions.16 UNESCO’s differentiation between tangible (material) and intangible (immaterial) culture reflects a Eurocentric view of cultural heritage and thus is inappropriate for interpreting the cultures of many groups. In the definition provided by UNESCO, intangible heritage is characterised as an invisible part of cultural heritage that is separate from what we consider tangible heritage, such as monuments and artefacts. However, the interconnection of intangible, tangible and natural heritages17 must not be overlooked.18 Taking natural heritage into consideration, it can be argued that the ‘land is not only interwoven by biodiversity, habitat and ecosystem but also our senses, emotions and connections to one another’.19 The conservation practices of many communities have been developed through their cultural values and understandings, which have reshaped the natural landscapes over time.20 Thus, it is relevant to reconceptualise natural heritage through its interconnectedness with intangible heritage.

Similarly, intangible heritage can be considered inseparable from material and tangible heritage. The separation of tangible and intangible heritage is inherently imprecise, as the construction and use of tangible heritage is often reliant on intangible heritage such as certain skills, traditional knowledge or social practices.21 More specifically, tangible heritage can be considered slow events created via specific processes and skills with particular values and meanings to the community.22 From this perspective, material culture gets its significance from socially attributed meanings rather than physical characteristics. Ise Jingu, the sacred shrine in Japan, is rebuilt every twenty years without undergoing any material changes or any changes in its use. The process of rebuilding the shrine takes eight years and has been carried out sixty-one times since the shrine’s creation by local carpenters who remember and try to pass on their knowledge. Therefore, Ise Jingu is a slow event related to the meanings, knowledge, skills and values that intertwine with the physical aspect of the building.23 This example challenges the validity of separating tangible and intangible heritage as suggested by international organisations24 as this would neglect the essence of the concept of heritage and its inherent complexities.

A second issue with the definition of intangible heritage adopted by UNESCO and others is that it implies a direct connection with communities. UNESCO’s definition is structured around preserving the cultural practices of communities. Although the relationship between intangible heritage and communities is important, the definition of community becomes blurrier in the urban context. Because of the dynamic and flexible nature of the concept of community in cities, people might belong to various groups and communities temporarily based on shared interests, such as music, lifestyle or even sexual orientation. Therefore, by definition, communities may be temporary, highly complex and interrelated. The community-centric approach to intangible heritage can also be criticised as biased towards well-organised groups that can better promote their roles and perspectives.25

Viewing heritage through the lens of communities can also limit its scope to social practices. In other words, the intangible heritage of communities may be viewed as separate from places and mostly contingent on the human bearers of tradition. Based on this perspective, some might defend the problematic assertion that the displacement of communities does not necessarily affect their intangible heritage. Given these concerns, it is beneficial to rethink the conceptualisation of communities within common definitions of intangible cultural heritage, particularly as they relate to the significance on the places in which the traditions are practiced.

Places and landscapes26 offer an interesting framework for examining the relationships between people and cultural heritage. As a theoretical concept, landscapes can be understood as ‘produced and lived in an everyday, practical, very material and repetitively reaffirming sense’.27 This concept can be characterised by social practices embedded in a spatial context.28 The landscape approach in heritage studies envisions urban landscapes as accumulations of the multiplicity of meanings, significance and collective and individual relevance to the past, present and future.29 This approach highlights the importance of spatiality and meanings in different contexts, supporting the idea that individuals and groups are inseparable from the places where they live.30 As Relph emphasises, ‘an individual is not distinct from his place; he is that place’.31 The daily lives of individuals and groups shape the places they inhabit and vice versa. Understanding intangible heritage in an urban context, which is often characterised by the multiplicity of communities and social groups, can be achieved through the study of the lives of its inhabitants and of their relationships with the built environment. In other words, rather than viewing intangible heritage as cultural expressions created by and dependent upon communities, we can look at the relationship between places and people regardless of the communities they might often be associated with. This is not to say that identifying communities and their cultural expressions should not be a priority; rather, it is to acknowledge places as valuable sources of knowledge that can help us better understand intangible assets. By examining places and the various processes that have shaped them, we can more clearly identify their intangible assets.32

As mentioned earlier, in order to understand intangible heritage, it is essential to pay attention to the continuous interaction between people and the physical environment.33 Intangible heritage can be considered an inclusive dimension of culture derived from the meanings and values people give to the environment. Based on this understanding, intangible heritage can be reconceptualised as heritage that emerges through the continuous interaction of people with their physical environment over time. It is embodied in people and is connected to places, objects and natural landscapes. Intangible cultural heritage can be manifested in values, beliefs, representations, skills, knowledge and social connections. This understanding diverges from the mainstream conceptualisation of tangible and intangible that confines them to certain forms. Reconceptualising heritage as an accumulation of tangible and intangible dimensions that have been interwoven into places has the potential to broaden our understanding of historic towns and centres.

The next section of this chapter delves into the history of the Iranian city of Mashhad, a city built on religious values. Based on archival studies, two years of direct observations in the area and individual interviews with residents, business owners and pilgrims, this research outlines the importance of intangible religious values in the formation and evolution of Mashhad and the manifestations of such values in the built environment in relation to the growing challenges of the twenty-first century.

The story of Mashhad: A city built on intangible values

Intangible heritages have played an important role in the development of the city of Mashhad since its origins in the ninth century. Mashhad began to expand and flourish following the death of Imam Reza in the year 818 AD (the eighth Shia Imam). Historically, there was a town in the vicinity of Imam Reza’s burial tomb named Sanabad. Over time, the number of pilgrims visiting the grave from Sanabad and other towns increased, leading to the creation of the first structure of Mashhad, which was a bazaar34 built on the road linking Sanabad to Imam Reza’s tomb.35 Thus, it can be argued that the first structure of the city was built as a direct result of religious visitors. With an increase in the number of pilgrims, many structures and buildings were constructed in the immediate vicinity. Over time, this growth led to the emergence of Mashhad as an independent city.

The growing importance of religious beliefs of Shias during the Safavid dynasty (the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries) brought various urban elements, including numerous karavansara (equivalent to modern day hotels), bazaars, mosques and main transport routes.36 As such, the city’s roots, as well as its subsequent development were shaped by intangible values—as a result of people’s affection for Imam Reza. The Holy Shrine and the tradition of pilgrimage not only created this city but also led to its growth. Religious values affected various dimensions of urban development in Mashhad, including its physical, economic, social and even environmental character.37

The economic character of the city has been built and reinforced through pilgrims and the culture of pilgrimage. Over time, not only has trade with pilgrims strengthened the economic development of Mashhad but the importance of souvenirs during pilgrimage has also contributed to the economic vitality and survival of this city.38 Moreover, the culture of devotion has played an important role in its economic development. The religious value of donating wealth for the public good has always been influential in the growth of Mashhad. Various schools, mosques, gardens, cemeteries, hammams, mausoleums, qanats, bazaars and hospitals have been built as a gift from the wealthy families of the city to the public.39 The religious character of the city has also been reflected in its social assets. Numerous social activities and relations have been shaped by religious traditions and celebrations, such as Ashura, Moharram and Ramazan. Mosques have been the centres of such religious activities during specific months and have created a strong social setting for residents and pilgrims. Despite all the recent developments, such cultural connections can still be seen in the centre of the city.

The most important aspect of Mashhad’s character that has affected its current situation is its physical dimension, which, like its other aspects, was also based on religious values. Etemado Alsaltaneh described the exteriors and facades of buildings as extremely simple and modest, originating from the religious values of humility and equality.40 One of the earliest Western visitors to Mashhad, James Bailie Fraser, also described the city’s humble physical character, noting that this simplicity is one of the most striking features for visitors.41 These qualities within the built environment, inspired by religious values, make Mashhad a city that has evolved based on the invisible and intangible values of spirituality, and demonstrate the necessity of recognising invisible values of heritage in historical assessments.

Intangible assets of Mashhad

Constructed based on intangible values, Mashhad has maintained its religious identity over the centuries. Furthermore, the built environment of the city has always had distinctive architectural qualities as compared with other historic Iranian towns, such as Yazd, Isfahan and Shiraz. A short description of its numerous intangible heritage assets is given below. These assets, while often overlooked by city planners and decision makers, make Mashhad an exemplar of a historic town based on intangible values.

Mashhad’s centre is home to a rich variety of tradition bearers that sustained cultural continuity through their local knowledge, oral history and craftsmanship. As emphasised by UNESCO (2003), the tradition bearers play a vital role in the survival of the tangible and intangible assets of communities. Recognition of these figures contributes to the expansion of knowledge regarding the cultural assets of communities. In Mashhad, apart from their role in sustaining oral history and different forms of local knowledge, they have also been involved in constructing traditional institutions as settings for social activities in different neighbourhoods. Mahdiye Abedzadeh, one of Mashhad’s important cultural institutions, was built and owned by the renown religious philanthropist Ali Asghar Abedzadeh. Over time, the institution has expanded in size, coming to encompass a number of buildings donated by Abedzadeh for cultural and religious purposes. The institution has become a social setting in the heart of various neighbourhoods for people to gather for religious or political debates, educational activities and other special events.

Certain places in each of the city’s neighbourhoods are designated for meetings and social gatherings among residents. A study on the historic neighbourhoods of Mashhad by the Samen Research Institute42 shows that each of the historic neighbourhoods has a centre where residents gather and socialise. These are often informal places known only by long-term residents. Yet, these places, which have been shaped through social connections, are threatened not only by redevelopment and construction projects but also by growing evictions of the residents and the loss of their social interactions.

Events play a significant role in the cultural survival of this city. Religious events in particular have shaped Mashhad’s physical environment. Seven major religious events take place each year in Mashhad and they are integral to the physical and social character of the city. These special events, where people traditionally distribute food, drink and gifts, are an important part of Mashhad’s spiritual and social vitality.

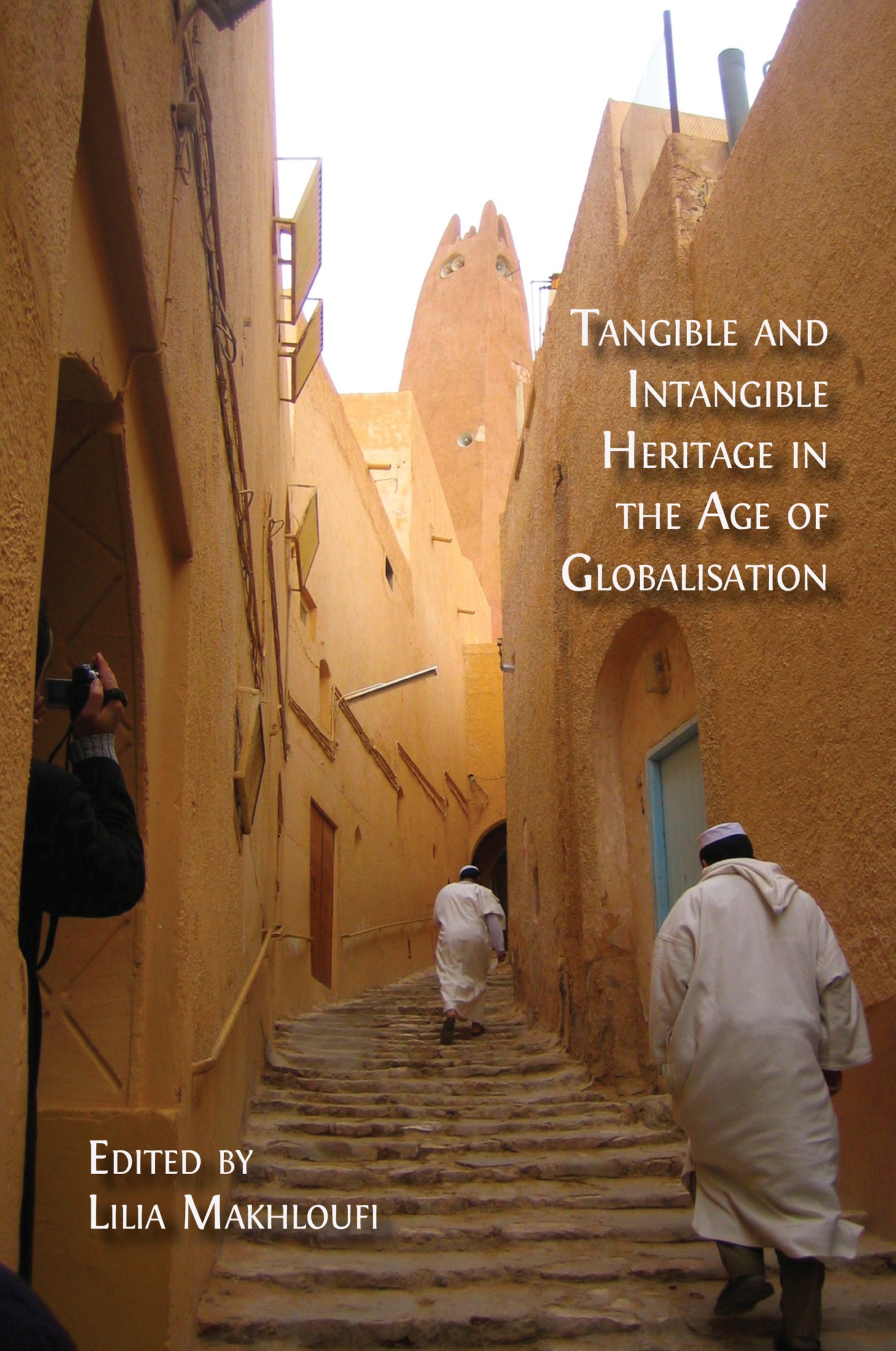

Fig. 3.1 Street installations for free food distribution during the month of Moharram, Mashhad. Author’s photograph, 2016, CC BY-NC-ND.

There are yearly religious marches that take place in the streets leading to the Holy Shrine. During Tasua and Ashura, which are the two most important religious days for Shias, all the streets leading to the holy shrine are full of devout citizens. These groups come from Mashhad and all around the country to be in the vicinity of Imam Reza on these special days. Apart from the religious events held in the mosques, there are three important houses that have hosted the celebrants of Ashura and Tasua for over one hundred years. These houses are not listed officially as places of religious events, but they are well known by all the residents of surrounding neighbourhoods.

Fig. 3.2 Street marches towards the Holy Shrine during the Month of Moharram, Mashhad. Author’s photograph, 2016, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 3.3 Street performance during Moharram, Mashhad. Author’s photograph, 2016, CC BY-NC-ND.

Religious performances have also been a source of cultural vitality in this area. These performances, inspired by historic events, have been conducted in special places that have been well-known in local knowledge and collective memory for one hundred years. Mashhad once housed ten such historic performance venues, but because of the neglect of these assets, only two of these locally important locations remain.

Food is also a significant part of the cultural identity of Mashhad. Not only does the city have a unique culture of distributing free food, but the distinctive dish of Mashhad, Sholeh,43 is iconic for its traditional preparation methods. The making of this dish, which has been listed as intangible heritage in Iran, entails a convergence of spirituality, devotion and cultural values.44 Still, although the recipe and the process of making Sholeh have been listed as national intangible heritage, the places in which this tradition takes place remain unrecognised. Every year, specific houses in the area cook this food and distribute it to the public. These houses, which have intangible values for residents, are often not prioritised in decision-making processes.

The aforementioned examples are just some of the rich cultural inheritances of the city of Mashhad—a city whose development has been shaped by religious traditions and values. However, Mashhad’s intangible heritage assets have been neglected by both the Iranian National Heritage Listing and UNESCO lists, as well as by the city’s decision makers and developers. As we will see in the following section, this negligence has resulted in massive transformations in the area that have threatened and destroyed both invisible and visible heritage.

The neglect of intangible heritage in the urban development plans of Mashhad

As mentioned above, the rich intangible cultural heritage of Mashhad has not been prioritised by decision makers and urban planners. The historic centre of the city, 360 hectares in size,45 has witnessed massive transformations in different historical periods from the Safavid era (the sixteenth to the eighteenth century) to the present. Its first redevelopment programme led to the construction of many courtyards and passageways to the shrine in the Timurid (the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries) and Safavid eras. The programme continued in the Pahlavi era (1925–1979) and later resulted in the disconnection of the bazaar from the Shrine and the construction of a large roundabout. These redevelopments were followed by a total relocation of the bazaar and extensive clearance around the shrine, which led to the destruction of many houses and retail stores during the second half of the twentieth century.46

One of the most controversial interventions in the historic centre of Mashhad and around the Holy Shrine was the renewal plan in 1966 proposed by the renowned Iranian architect, Borbor. This plan crucially overlooked the historic value of the area with the exception of a few buildings and proposed massive transformations of the built environment.47 Further plans, especially the one implemented by Abdolazim Valian in 1973, led to the destruction of the urban fabric within 320 metres of the shrine.48 However, the most impactful redevelopment and transformations in this district happened in 1992,49 when a renewal plan stressed this area’s inefficiency and lack of urban and architectural value, and proposed massive demolitions and reconstructions.

The plan defined its goals as follows: (i) improving the role and importance of the religious character of the city as a hub for Islam and Muslim pilgrims and (ii) increasing the economic competitiveness of the city at local, regional and international levels. The second goal involved a focus on the religious role of the city when amending the physical environment, satisfying the needs of pilgrims and providing opportunities for investment.50 The plan proposed major transformations in the area; based on the recommendations, a large part of the centre had to be demolished and rebuilt. New forms of blocks and road networks were built without consideration for the historic fabric of the area and mostly for the usage of short-term residents and tourists. This led to the dislocation of a high proportion of the original residents and the massive destruction of an urban fabric with a rich history. A large part of Mashhad’s centre, which had residential infrastructure prior to the redevelopment proposals, was replaced by commercial and retail infrastructure. The decrease in the population of the area, from ~58,000 in 1991 to 32,851 in 2011, is also an indication of dislocation of residents from this area.51

In the aforementioned redevelopment plans, the historic value of this centre was assessed by the architectural value of the buildings. As mentioned above, the centre of Mashhad has been built upon religious values of humility and equity and did not have the common architectural qualities of Iranian historic centres. This led to the neglect of its intangible heritage value and as a result, to the destruction of its built as well as its intangible heritage.

Conclusion: The importance of reconceptualising intangible heritage in decision making

Cities are filled with cultural assets that may extend beyond the built environment and tangible manifestations. Historic urban environments are built on both material and immaterial elements. These invisible assets impact not only the daily lives of inhabitants, but also the designs and development of built landscapes.

The story of the evolution and development of Mashhad, as well as the challenges it is facing in the twenty-first century, shows the necessity of a reconceptualised perspective on intangible heritage. As a city built on intangible religious values, it is facing numerous challenges to the preservation and valorisation of its assets. The story of Mashhad shows that our current perspective towards listing tangible and intangible heritage is insufficient, and that there is a growing need for new tools and frameworks to better recognise and integrate these assets. Although novel theoretical frameworks and guidelines for a comprehensive understanding and representation of tangible and intangible assets have been introduced in the last two decades, the negligence of invisible assets in wider decision-making processes remains a significant problem. Whereas new methods, such as cultural mapping, seem to be a promising approach for identification and representation of tangible and intangible cultural assets, there are still various challenges related to them.52

Cultural mapping methods focus on processual approaches involving communities in defining and representing their cultural assets. Although the cultural mapping approach highlights the necessity of mapping both tangible and intangible assets, it is mostly focused on quantifiable and material resources while its treatment of intangible elements is often ambiguous.53

These challenges not only necessitate a new approach for identifying and representing intangible heritage with a fresh definition built on a place-related concepts, but they also call attention to the importance of a systematic method for wider planning and decision-making purposes. In the twenty-first century, the need to develop a systematic methodology capable of capturing and systematically representing the invisible essence of cultural heritage for urban researchers and decision makers is crucial. The methodological innovations should be primarily based on a revised concept of urban heritage, which liberates the notion from the constraints of listings and inventories and acknowledges the interconnectedness of visible and invisible assets. This reconceptualisation is an important step for the protection of the cultural identity of cities.

Bibliography

Aikawa, Noriko, ‘A Historical Overview of the Preparation of the UNESCO International Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage’, Museum International, 56:1–2 (2004), 137–49, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-0775.2004.00468.x.

Akbari Motlagh, Mostafa, ‘Barrasiye tajrobeye modâxele dar bâfte markaziye šahre mašhad’ [Assessing Transformations in Mashhad’s Central District], Sepidar Urban Planning and Architecture Research Institute (2014).

Asgharpour Masule, Ahmad Reza and Behravan, Hossein, ’Cârcubi mafhumi barâye tahlile jâm’ešenâxti hamkâri miyane konešgarân dar barnâme nosâziye bâftahâye farsude bâ takid bar mantaqe sâmene mašhad’ [A Conceptual Framework for Sociological Assessment of Cooperation between Actors in Redevelopment of Distressed Area Focusing on Samen District in Mashhad], Mashhad Pazuhi, 5 (2010), 35–56.

Bailie Fraser, James, Safarnâmeye Fraser [Fraser’s Travel Diary], translated by Amiri, Manouchehr (Tehran: Toos, 1821).

Bandarin, Francesco, and Van Oers, Ron, The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119968115

Bertorelli, Caroline, ‘The Challenges of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage’, 観光学研究= Journal of Tourism Studies, 17 (2018), 91–117

Duncan, James and Duncan, Nancy, ‘Can’t Live with Them, Can’t Landscape without Them: Racism and the Pastoral Aesthetic in Suburban New York,’ Landscape Journal, 22:2 (2003), 88–98, https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.22.2.88

Duxbury, Nancy, Garrett-Petts, W. F. and MacLennan, David, Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry: Introduction to an Emerging Field of Practice (New York: Routledge, 2015), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315743066

Etemado Alsaltane, Matlaelšams [Sunrise] (Tehran: Farhangsara Publications: 1983).

Grevstad-Nordbrock, Ted and Vojnovic, Igor, ‘Heritage-Fueled Gentrification: A Cautionary Tale from Chicago’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 38 (2019), 261–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.08.004

Hafstein, Valdimar, ‘Intangible Heritage as a List: From Masterpieces to Representation’, in Intangible Heritage, ed. by Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 93–111.

Isna, ‘Sabte melliye šoleye Mašhad’ [National Listing of Mashhad’s Sholeh] (Isna.ir, 2017), https://www.isna.ir/news/96071005128/

Jeannotte, Sharon M., ‘Story-telling about Place: Engaging Citizens in Cultural Mapping’, City, Culture and Society, 7:1 (2016), 35–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.07.004

Jigyasu, Rohit, ‘The Intangible Dimension of Cities’, in Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage, ed. by Franceso Bandarin and Ron Van Oers (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

Kato, Kumi, ‘Community, Connection and Conservation: Intangible Cultural Values in Natural Heritage—The Case of Shirakami‐sanchi World Heritage Area’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12:5 (2006), 458–473, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250600821670

Kirshenblatt‐Gimblett, Barbara, ‘Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production 1’, Museum International, 56:1–2 (2004), 52–65, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-0775.2004.00458.x

Kurin, Richard, ‘Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in the 2003 UNESCO Convention: A Critical Appraisal’, Museum International, 56:1–2 (2004), 66–77, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-0775.2004.00459.x

Leimgruber, Walter, ‘Switzerland and the UNESCO Convention on Intangible Cultural Heritage’, Journal of Folklore Research: An International Journal of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, 47:1–2 (2010), 161–196, https://doi.org/10.2979/jfr.2010.47.1-2.161

Longley, Alys, and Duxbury, Nancy, ‘Introduction: Mapping Cultural Intangibles,’ City, Culture and Society, 7:1 (2016), 1–7, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.12.006

Mahavan, Ahmad, Târixe Mašhadol Rezâ [Mashhad’s History] (Mashhad: Mahavan, 2004).

Marrie, Henrietta, ‘The UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Protection and Maintenance of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Peoples’, in Intangible Heritage, ed. by Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa (London: Routledge, 2009).

Radovic, Darko, ‘Measuring the Non-Measurable: On Mapping Subjectivities in Urban Research’, City, Culture and Society, 7:1 (2016), 17–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.10.003

Relph, Edward, Place and Placelessness, vol. 67 (London: Pion, 1976).

Rezvani, Alireza, Dar jostojuye howeyate šahre Mašhad [In Search for Mashhad’s Identity] (Tehran: Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, 2005).

Ruggles, D. Fairchild and Silverman, Helaine, ‘From Tangible to Intangible Heritage’, in Intangible Heritage Embodied, ed. by Helaine Silverman and D. Fairchild Ruggles (New York: Springer, 2009), pp. 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0072-2

Samen Research Institute, Asarâte tarhe tose’eye mantaqeye sâmen [Impacts of the Development Plan of Samen District] (Mashhad: Samen Research Institute, 2018).

Sarkheyli, Elnaz, Rafieian, Mojtaba, and Taghvaee, Ali Akbar, ‘Assessing the Convergence Effects of Religious and Economic Forces on the Contemporary Changes of Form and Shape of Samen Region in Mashhad’, Motaleat Shahri, 12 (2015), 87–101.

Sarkheyli, Elnaz, Rafieian, Mojtaba, and Taghvaee, Ali Akbar, ‘Qualitative Sustainability Assessment of the Large-Scale Redevelopment Plan in Samen District of Mashhad’, International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development, 6:2 (2016), 49–58.

Seyedi, Mahdi, Târixe šahre Mašhad [Mashhad’s History] (Tehran: Jami, 1999).

Smith, Laurajane and Akagawa, Natsuko, eds., Intangible Heritage (London: Routledge, 2009), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203884973

Swensen, Grete, Jerpåsen, Gro B, Sæter, Oddrun, and Tveit, Sundli Mari, ‘Capturing the Intangible and Tangible Aspects of Heritage: Personal Versus Official Perspectives in Cultural Heritage Management’, Landscape Research, 38:2 (2013), 203–221, https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2011.642346

Tash Consultant Engineers, ‘Tarhe nosâzi va bâzsâziye bâfte pirâmune harame motahhar’ [Regeneration of Holy Shrine’s surrounding district], Mashhad: MHDCC (1994).

Tavassoli, Vahid, ‘Arzešhâye târixiye harame motahhare razavi dar šekl giri va tose’eye šahre Mašhade moqadas’ [Historical Values of Creation and Development of Mashhad], International Congress on Revising Islamic Cultural Civilization and Islamic Cities with Focus on Mashhad (Mashhad: 2017).

UNESCO, ‘Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage’, General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Thirty-Second Session, Paris, September 29–October 17 (2003), https://ich.unesco.org/en/conventio.

Van der Hoeven, Arno, ‘Networked Practices of Intangible Urban Heritage: The Changing Public Role of Dutch Heritage Professionals’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25:2 (2019), 232–245, https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1253686

Vecco, Marilena, ‘A Definition of Cultural Heritage: From the Tangible to the Intangible’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11:3 (2010), 321–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2010.01.006

Veldpaus, Loes, Pereira Roders, Ana R., and Colenbrander, Bernard J. F., ‘Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future’, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 4:1 (2013), 3–18, https://doi.org/10.1179/1756750513Z.00000000022

1 Francesco Bandarin and Ron Van Oers, The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

2 Noriko Aikawa, ‘A Historical Overview of the Preparation of the UNESCO International Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage’, Museum International, 56:1–2 (2004), 137–149.

3 D. Fairchild Ruggles and Helaine Silverman, ‘From Tangible to Intangible Heritage’, in Intangible Heritage Embodied, ed. by Helaine Silverman and D. Fairchild Ruggles (New York: Springer, 2009), pp. 1–14.

4 Richard Kurin, ‘Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in the 2003 UNESCO Convention: A Critical Appraisal’, Museum International, 56:1–2 (2004), 66–77.

5 Barbara Kirshenblatt‐Gimblett, ‘Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production 1’, Museum International, 56:1–2 (2004), 52–65.

6 Alys Longley and Nancy Duxbury ‘Introduction: Mapping Cultural Intangibles’, City, Culture and Society, 7:1 (2016), 1–7; Rohit Jigyasu, ‘The Intangible Dimension of Urban Heritage’, in Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage, ed. by Francesco Bandarin, Francesco and Ron Van Oers (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), pp. 129–160; Longley and Duxbury, ‘Introduction: Mapping Cultural Intangibles’, pp. 1–7.

7 Longley and Duxbury, ‘Introduction: Mapping Cultural Intangibles’.

8 Caroline Bertorelli, ‘The Challenges of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage’, 観光学研究= Journal of Tourism Studies, 17 (2018), 91–117.

9 Darko Radovic, ‘Measuring the Non-Measurable: On Mapping Subjectivities in Urban Research’, City, Culture and Society, 7:1 (2016), 17–24.

10 Ted Grevstad-Nordbrock and Igor Vojnovic, ‘Heritage-Fueled Gentrification: A Cautionary Tale from Chicago’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 38 (2019), 261–70.

11 Sharon M. Jeannotte, ‘Story-Telling About Place: Engaging Citizens in Cultural Mapping’, City, Culture and Society, 7:1 (2016), 35–41.

12 Longley and Duxbury, ‘Introduction: Mapping Cultural Intangibles’.

13 Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa, Intangible Heritage (London: Routledge, 2009).

14 Henrietta Marrie, ‘The UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Protection and Maintenance of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Peoples’, in Intangible Heritage, ed. by Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa (New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 169.

15 UNESCO, ‘Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage’ General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, thirty-second session, Paris, September 29–October 17 (2003).

16 Walter Leimgruber, ‘Switzerland and the UNESCO Convention on Intangible Cultural Heritage’, Journal of Folklore Research: An International Journal of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, 47:1–2 (2010), 161–196; Valdimar Hafstein, ‘Intangible Heritage as a List: From Masterpieces to Representation’, in Intangible Heritage, ed. by Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa (New York: Routledge, 2009), pp. 93–111; Kumi Kato, ‘Community, Connection and Conservation: Intangible Cultural Values in Natural Heritage—the Case of Shirakami‐sanchi World Heritage Area’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12:5 (2006), 458–473 (93–111).

17 Natural heritage refers to natural features, geological and physiographical formations and delineated areas that constitute the habitat of threatened species of animals and plants and natural sites of value from the point of view of science, conservation or natural beauty (UNESCO, 1972).

18 Kirshenblatt‐Gimblett, ‘Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production 1’.

19 Kato, ‘Community, Connection and Conservation’, 67.

20 Ibid.

21 Kirshenblatt‐Gimblett, ‘Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production 1’.

22 Marilena Vecco, ‘A Definition of Cultural Heritage: From the Tangible to the Intangible’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11:3 (2010), 321–324.

23 Kirshenblatt‐Gimblett, ‘Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production 1’.

24 Silverman and Fairchild, ’From Tangible to Intangible Heritage’.

25 Arno Van der Hoeven, ‘Networked Practices of Intangible Urban Heritage: The Changing Public Role of Dutch Heritage Professionals’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25:2 (2019), 232–45.

26 Grete Swensen, Gro B Jerpåsen, Oddrun Sæter, and Mari Sundli Tveit, ‘Capturing the Intangible and Tangible Aspects of Heritage: Personal Versus Official Perspectives in Cultural Heritage Management’, Landscape Research, 38:2 (2013), 203–21.

27 James Duncan and Nancy Duncan, ‘Can’t Live with Them, Can’t Landscape without Them: Racism and the Pastoral Aesthetic in Suburban New York,’ Landscape Journal, 22:2 (2003), 88–98 (p. 7).

28 Swensen et al., ‘Capturing the intangible and tangible aspects of heritage’.

29 Loes Veldpaus, Ana R. Pereira Roders, and Bernard J.F. Colenbrander, ‘Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future’, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 4:1 (2013), 3–18.

30 Swensen et al., ‘Capturing the intangible and tangible aspects of heritage’.

31 Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness, vol. 67 (London: Pion, 1976), p. 43.

32 Ibid.

33 Swensen et al., ‘Capturing the intangible and tangible aspects of heritage’.

34 Alireza Rezvani, Dar jostojuye howeyate šahre Mašhad [In Search for Mashhad’s Identity] (Tehran: Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, 2005).

35 Ahmad Mahavan, Târixe Mašhadol Rezâ [Mashhad’s History] (Mashhad: Mahavan, 2004); Rezvani, Dar jostojuye howeyate šahre Mašhad.

36 Ibid.; Maryam Mirahmadi, Dino Dowlat [Religion and the State] (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1990).

37 Vahid Tavassoli, ‘Arzešhâye târixiye harame motahhare razavi dar šekl giri va tose’eye šahre Mašhade moqadas’ [Historical Values of Creation and Development of Mashhad], International Congress on Revising Islamic Cultural Civilization and Islamic Cities with Focus on Mashhad (Mashhad: 2017).

38 Mahdi Seyedi, Târixe šahre Mašhad [Mashhad’s History] (Tehran: Jami, 1999); Tavassoli ‘Arzešhâye târixiye harame motahhare razavi dar šekl giri va tose’eye šahre Mašhade moqadas’.

39 Seyedi, Târixe šahre Mašhad.

40 Etemado Alsaltane, Matlaelšams [Sunrise] (Tehran: Farhangsara Publications: 1983).

41 James Bailie Fraser, Safarnâmeye Fraser [Fraser’s Travel Diary], translated by Manouchehr Amiri (Tehran: Toos, 1821).

42 Samen Research Institute, Asarâte tarhe tose’eye mantaqeye sâmen [Impacts of the Development Plan of Samen District] (Mashhad: Samen Research Institute, 2018).

43 Šole [Sholeh] is the traditional food of Mashhad, which is made of meat, beans and spices.

44 Isna, Sabte melliye šoleye Mašhad [National Listing of Mashhad’s Sholeh] (Isna.ir, 2017), https://www.isna.ir/news/96071005128/

45 Elnaz Sarkheyli, Mojtaba Rafieian, and Ali Akbar Taghvaee, ‘Assessing the Convergence Effects of Religious and Economic Forces on the Contemporary Changes of Form and Shape of Samen Region in Mashhad’, Motaleat Shahri, 12 (2015), 87–101.

46 Elnaz Sarkheyli, Mojtaba Rafieian, and Ali Akbar Taghvaee, ‘Qualitative Sustainability Assessment of the Large-Scale Redevelopment Plan in Samen District of Mashhad’, International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development, 6:2 (2016), 49–58; Sarkheyli et al., ‘Assessing the Convergence Effects of Religious and Economic forces on the Contemporary Changes of Form and Shape of Samen Region in Mashhad’.

47 Mostafa Akbari Motlagh, ‘Barrasiye tajrobeye modâxele dar bâfte markaziye šahre mašhad’ [Assessing Transformations in Mashhad’s Central District], Sepidar Urban Planning and Architecture Research Institute (2014).

48 Sarkheyli et al., ’Qualitative Sustainability Assessment of the Large-Scale Redevelopment Plan in Samen District of Mashhad’.

49 Sarkheyli et al., ‘Assessing the Convergence Effects of Religious and Economic forces on the Contemporary Changes of Form and Shape of Samen Region in Mashhad’.

50 Tash Consultant Engineers, Tarhe nosâzi va bâzsâziye bâfte pirâmune harame motahhar [Regeneration of Holy Shrine’s Surrounding District] (Mashhad: MHDCC, 1994).

51 Ahmad Reza Asgharpour Masule and Hossein Behravan, ’Cârcubi mafhumi barâye tahlile jâm’ešenâxti hamkâri miyane konešgarân dar barnâme nosâziye bâftahâye farsude bâ takid bar mantaqe sâmene mašhad’ [A Conceptual Framework for Sociological Assessment of Cooperation between Actors in Redevelopment of Distressed Area Focusing on Samen District in Mashhad], Mashhad Pazuhi, 5 (2010), 35–56.

52 Nancy Duxbury, W. F. Garrett-Petts, and David MacLennan. Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry: Introduction to an Emerging Field of Practice (New York: Routledge, 2015).

53 Duxbury et al., Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry, p. 22.