4. Promoting the Role of Egyptian Museums in Nurturing and Safeguarding Intangible

Cultural Heritage

©2024 Heba Khairy, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.04

Introduction

Egyptian heritage is rooted in the earliest eras of ancient Egypt, when Egyptians recorded scenes from their daily lives and traditions on the walls of temples and tombs, including scenes of agriculture, dance performances, arts, industry, and religious rituals. Traditional handicrafts were an important part of these murals, which depicted the making of papyrus, pottery, jewellery, glass, and textiles as well as stone, metals, wood, and leather making. This heritage evolved and expanded through time due to cultural accumulation and the exchange of influence and knowledge with other cultures and civilizations neighbouring Egypt. As a result, the country became renowned among nations for its rich intangible cultural heritage (ICH), characterized by an originality, creativity, and diversity which reflects the depth and continuity of Egypt’s various unique communities and groups.

Egyptian tangible heritage is considerably less endangered by the threats of deterioration and extinction than its intangible counterpart, likely as a result of the country’s numerous museums, which have made preserving tangible heritage their priority. Since these museums began to be established at the beginning of the twentieth century, they have successfully dealt with material artifacts, with little awareness or attention paid to the importance of preserving ICH. This chapter aims to provide a prototype for how Egyptian museums can evolve their functions and operations in order to take on a greater role in the safeguarding of living heritage, while engaging heritage practitioners and bearers in this process.

Globalisation of intangible heritage

The twenty-first century has already witnessed many conflicts, critical events and changes that have strongly affected human intellectual production and identity. The rapid growth of globalisation, industrialisation and modernity has made these processes an inescapable destiny for communities worldwide.1 The objectives of globalization are characterized as positive in terms of outward impact, as the world has become more connected than ever before through technological advancements and economic integration. However, it has proved negative in terms of inward impact, as it has increased income inequality and substandard working conditions in developing countries that produce goods for wealthier nations, which accordingly affects traditional handicraft production. Globalisation has also been characterised as having hidden consequences, which include the elimination of intellectual, cultural, and human interactions between groups belonging to one place and civilisation.2 It is widely acknowledged that globalisation has given traditional craftsmen and their handicrafts access to new technology and increased product quality, but surprisingly, many concerns have been raised over the impact on employment and the deterioration in the quality of jobs. So, it has been suggested that globalisation has also brought about ‘negative inclusion,’ since economic exclusion is linked to exclusion from the limited public space that remained accessible for discussion and negotiation. Globalisation has adversely affected the heritage practitioners’ engagement, participation, transparency, accessibility, and accountability.3 This has led to a widening gap between individuals and their communal identities, as well as the gradual disappearance of inherited traditions, values, and intellectual creativity.4 In Egypt, most handicrafts are facing a fierce struggle for survival as human capital is replaced by modern industrial machinery. Currently, Egyptian artisans are fighting against the tide of industrial mechanics, synthetic fibres, and plastic products—materials which are not used to create new forms but merely imitations of traditional artisan work. The result is a hybrid product that lacks the soul of the Egyptian cultural tradition while pretending to have integrity and authenticity. Accordingly, traditional artisans experience increasing difficulty in finding their raw materials, preparing them, making tools, and finding ways to overcome modern obstacles.5

The negative consequences of globalization have become a global issue urgently requiring action by international and national organisations as well as museums to develop strategies, policies and measures to confront the erosion of traditions.6 To this end, the International Committee of Museums (ICOM) added the concept of ‘intangible heritage’ to its definition of museums, leading to a notable shift in museum practices.

Museums worldwide, particularly Asian and European museums, have taken important steps towards increasing their involvement in the safeguarding of ICH. They have transformed from guardians of the past to cultural and educational institutions which enshrine the meaning of societies’ transformations. From 2017 to 2020, museums in Belgium, Switzerland, the Netherlands, France and Italy cooperated to create the Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museums Project (IMP), which explored the various practices and approaches of museums to safeguarding intangible heritage. The participating museums provided mutual assistance in the protection of ICH while working alongside its practitioners. IMP helped museums to support heritage communities, groups and individual practitioners in transmitting their cultural practices to future generations. The project succeeded in making living heritage an integral part of future museum practices and policies through the participation and engagement of the practitioners within the museum programmes, galleries and different activities. Additionally, IMP helped to build and develop the capacities of museum professionals by providing them opportunities to exchange knowledge and experiences such as at workshops and conferences.7

Egypt’s intangible heritage domains

Egypt’s modern history is an endless narrative of social, cultural and political innovations drawing on the experiences of the people who settled in the narrow valley in the middle of the Egyptian desert.8 Looking at the relics, reliefs, and monuments of ancient Egypt, we cannot help but notice how much of the ancient heritage of the pharaohs is still reflected in present-day life in Egypt. Egyptians are conservative and keen to safeguard old rituals and inherited traditions which give modern Egyptians a sense of stability, belonging and continuity.9

Oral traditions and expressions

Although the national language of Egypt is Arabic, there are many other ethnic and indigenous languages widely spoken among the ethnic communities (e.g., the Amazigh, Nubian and Bedouin tribes). These languages express an enduring living legacy and are harmonious and overlapping with the oral expressions of Egyptians from thousands of years ago.10

Performing arts

Upper Egypt and the Delta Region have a unique and authentic musical and performing heritage11 which includes distinctive dances. For example, Al Tahteeb is a traditional dance of Upper Egypt performed by men wielding long sticks, sometimes on horseback. The dance of Zagal is an individual or communal dance performed by men in the Siwa Oasis which consists of continuous rolling and spinning in circles to the rhythm of drums and traditional musical instruments.12

Social practices, rituals, and festive events

Whether they are Copts or Muslims, Egyptians celebrate birthdays or anniversaries to honour saints or holy men in ceremonies known as Mulid which date back to ancient Egyptian traditions honouring kings and gods. In Egypt, almost every city, neighbourhood or town has its ‘holy man’ buried under a dome or tree.13

Knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe

The belief in both good and bad luck has persisted from ancient Egypt. Today, Egyptians still endeavour to predict their good days, bad days and future events by reading shells, palms and the stars. Many believe blue-eye amulets, touching wood or repeating certain phrases or spells offers protection against the evil eye and envious spirits.14

Crafts and traditional handicrafts

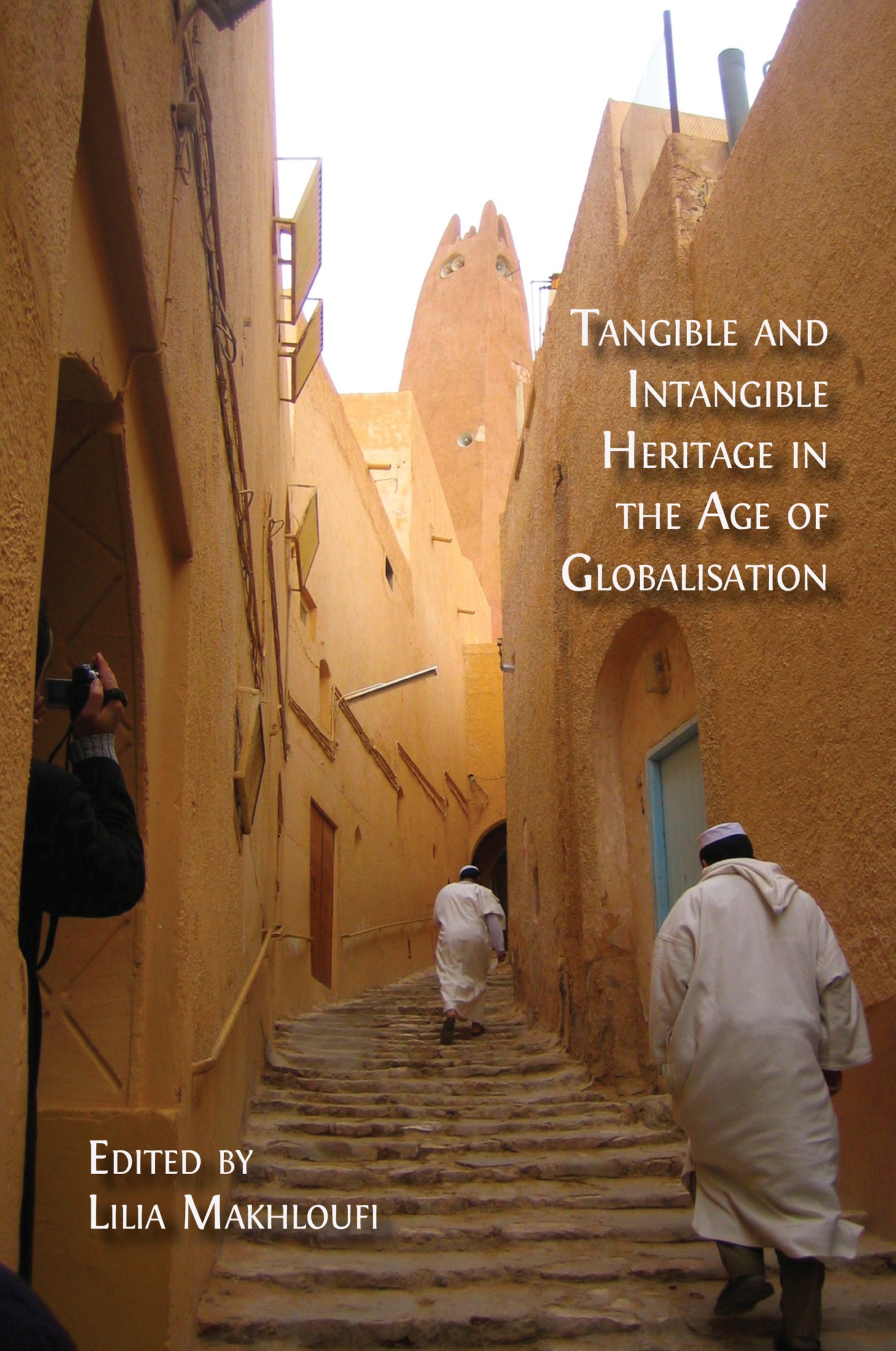

Many traditional handicrafts practised in contemporary Egypt date back hundreds or thousands of years. Looking at the scenes and reliefs depicted on the walls of ancient Egyptian temples and tombs, we can see ancient Egyptians represented while making pottery, spinning fabric, making papyri or carving stones and wood.

Fig. 4.1 Egyptian artist weaving a hand stitch portrait, Al-Khayameia traditional market, historical Cairo, Egypt. Author’s photograph, 2019, CC BY-NC-ND.

Egyptian cities are also rich in traditional handicrafts. These include copper, glass, and wooden artwork, jewellery, carpets and hand-woven textiles, as well as pottery, which is one of the oldest crafts in Egypt. Pottery is distinctive in various parts of Egypt, such as Fustat in Cairo, Fayoum City, Damietta and many cities and villages of Upper Egypt.15

Inscribed intangible heritage of Egypt

Egypt was one of the first states to adopt the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of ICH. As a result, Egypt succeeded in inscribing seven elements of its intangible heritage on the lists of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): three elements on the representative list and two elements on the urgent safeguarding list. However, it is worth noting that this is a relatively small number considering the richness of Egyptian ICH. Accordingly, Egypt must take decisive measures to ensure that more elements of its living heritage are inscribed.

Festivals related to the Journey of the Holy Family

Every year, Christian and Muslim Egyptians of all ages celebrate the feast of the Journey of the Holy Family to Egypt and the birth of the Virgin Mary. These celebrations include singing, traditional games, re-enactments of the journey, religious processions, artistic performances, and the sharing of traditional foods. The celebrations are filled with social functions and cultural meanings, including the unified social and cultural fabric among Christians and Muslims.

Arabic calligraphy

Arabic calligraphy is considered a symbol of the Arab-Islamic world. The artistic practice of writing Arabic calligraphy expresses the harmony and beauty between the letters of the Arabic language. The fluidity of Arabic calligraphy provides unlimited possibilities for writing letters and transforming them in many ways to create different forms of the same word. Unfortunately, many Arabs no longer write by hand due to technological advances, which has led to a sharp decline in the number of specialized Arabic calligraphy artists.

Handmade weaving in Upper Egypt

The famous tradition of hand-weaving in Upper Egypt has been practised since the Pharaonic eras up to the present. It is distinguished across various governorates of Upper Egypt by the use of different types of looms, such as Akhmimi weaving in Sohag, Farka in Naqada Qena and Adawi kilim in Assiut. Additionally, hand-weaving tools and practices differ from one governorate to another, resulting in a diverse textile heritage across the country. For instance, Assiut kilims are different that those in Marsa Matrouh, and looms differ from one place to another.16

Date palm, knowledge, skills, traditions and practices

Date palm practices have special industrial, culinary and religious importance in Egypt. Date palm was initially cultivated thousands of years ago in the Nile Valley. It was given various names in Ancient Egypt including Bni, Buno and Benrt. In ancient as well as modern Egypt, date palm leaves have been used for basket making, while the trunks have been used to make roofing for houses in rural areas.17

Al-Aragoz traditional hand puppetry

Al-Aragoz is a form of traditional Egyptian puppet theatre, involving glove dolls. Some researchers claim that this traditional puppet theatre has been passed down from ancient Egyptian heritage, whereas others trace it back to the Mamluk period.18

Tahteeb (stick game)

Tahteeb is a form of individual martial and dance art that was practised in ancient Egypt and is still practised today; however, while it retains some of its original symbolism, in modern times it has become more of a festive game. It is performed in front of a public audience by two male rivals wielding sticks in a non-violent competition.19

Al-Sirah Al-Hilaliyyah

Al-Sirah Al-Hilaliyyah, also known as the Al-Hilaly Epic, tells the story of the Bedouin tribe of Bani Hilal, which migrated from the Arab Peninsula to North Africa in the tenth century. The biography of Al-Hilaly, which disappeared everywhere except Egypt, is considered one of the most important epic poems, which emerged as folk art in its musical form.20

Egyptian museums from a heritage perspective

Egyptian heritage has dazzled the world,21 attracting the curiosity of researchers and amateurs alike. Accordingly, museums all over the globe are keen to acquire, display, preserve and study Egyptian antiquities within their museums and institutions.22

Egypt was the first country in the Middle East to create museums to collect and conserve the country’s ancient treasures and express its temporal, civilisational and spatial identity. Egypt is renowned for its antiquities, which are displayed in dozens of museums that constitute major cultural wealth.23

Nevertheless, Egyptian museums are archaeological museums concerned with artefacts from ancient Egypt. These museums have a traditional function in terms of representing the country’s national identity and history, through the preservation and study of the Egyptian antiquities.24 As a result, these museums have neglected interpretive elements which would shed light on the specificity of Egyptian living heritage and link contemporary Egyptian society with its ancient past through inherited and continued practices. Thus, Egyptian museums may be losing their opportunity to be the premier supporters and interpreters of their communities’ identities and beliefs. Today, Egyptian museums are stressing the need to develop deliberate policies for the advancement and marketing of museums at home and abroad.

The historical and multicultural city of Cairo is considered an open museum, reflecting thousands of years of history, heritage and civilisations. As the capital of Egypt, Cairo is home to the country’s major museums, which are regarded as among the most appealing attractions for visitors interested in Egyptian heritage, whether foreign or local. Based on interviews and surveys, the present research found that compared with other museums in Egypt, Cairo’s museums are the most active in terms of the programmes and activities they offer to visitors.25

Egyptian museums and the community

The placement of objects at the centre of Egyptian museums’ concerns and core functions has created barriers between the Egyptian museums and their local visitors, local communities and living heritage. Egyptian museums do not reflect the challenges and changes that have occurred in Egyptian society in the last ten years, and as such, they do not meet the needs and expectations of Egyptian communities. Local communities are likewise not adequately incorporated into museums’ programmes and activities,26 nor are heritage practitioners involved in museums’ efforts to preserve and ensure the sustainability of living heritage.

Nevertheless, some Egyptian museums have made attempts in recent years to incorporate living heritage through programmes, activities and temporary exhibitions aimed at providing interactive and educational experiences through which Egyptian communities can learn about their heritage. Some of these programmes and activities have revolved around traditional handicrafts and folk performances. These attempts constitute a commendable step towards implementing new practices within Egyptian museums for presenting Egyptian living heritage.27 Notably among these efforts are those that have been made by the Cairo Egyptian Museum and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation through their children’s museum and educational department. This has included numerous educational programmes and activities led and performed by heritage practitioners and artisans, such as tactile tours, handicrafts workshops and art performances. These programs and activities aim to extract the intangible heritage value from the museum objects. Another example is a temporary exhibition developed by the National Museum for Egyptian Civilization entitled ‘Egyptian Handicrafts Across the Ages’, which focused on the historical development of Egyptian traditional crafts.28

The Nubian Museum in Aswan provides an interesting experience based on the Nubian community traditions and folk lifestyle, using dioramas and real contemporary Nubian objects from the community.29 Between 2014 and 2019, the Egyptian Textile Museum also held several programmes and lectures raising awareness about Egyptian traditional handicrafts as part of its annual World Heritage Day celebrations. Likewise, every year, the Egyptian Textile Museum also celebrates the Egyptian Heritage Festival.30

Unfortunately, the efforts described above lack continuity, effectiveness and creativity because they do not encourage the engagement and integration of heritage carriers (i.e. the heritage practitioners and heritage custodians). Moreover, Egyptian museums lack financial and professional capacities, effective strategies, communication tools and plans to deal with all domains of Egyptian intangible heritage and their practitioners. These factors have put Egyptian museums decades behind their international counterparts, who have made great strides in the last decade towards engaging with local communities to reflect their living identity and contemporary challenges.

Towards new models of museums functions in Egypt

Egypt’s museums can effectively contribute to safeguarding and supporting intangible heritage, as well as the country’s communities and individual practitioners who are keen to pass on their cultural practices to future generations. The measures outlined below are ways museums can protect and nurture living heritage, namely through its integration in practice and policies, as well as the adoption of participatory and people-centred approaches.31

Adaption of laws and legislation

Egypt has passed many laws on the protection and preservation of cultural heritage, but these have focused only on tangible heritage without mentioning any of the intangible forms of Egyptian culture. This means that the Egyptian state has not yet considered any legal measures to ensure the protection of intangible materials.32

The Egyptian Constitution, ratified in 2014, includes several provisions that confirm the state’s commitment to protecting the identity and cultural diversity of its communities. However, the term ‘intangible’ was not explicitly mentioned in these provisions. Thus, there is a need for legislation which explicitly affirms the state’s obligation to protect ICH and the ethnic communities that live within the country’s borders. The Egyptian government must develop practical instruments and theoretical guidelines that can contribute to protecting and supporting intangible heritage and its practitioners.33

Documenting and collecting ICH

The procedures for documenting artefacts and objects within Egyptian museums are different from creating an inventory of intangible heritage.34 Therefore, Egyptian museums should develop documentation policies and standards that reflect and are more relevant to the Egyptian characteristics of their living heritage. This can be done by combining both methodologies, generating an enriched approach to heritage documentation via the following measures:35 linking community-based heritage inventories to object-identification systems, moving from object collecting to collecting heritage stories within the Egyptian community, and creating a databank to be integrated into existing museum databases for the intangible elements that are collected.36 These measures could be successfully implemented through cooperation with the Centre for the Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage, which is developing projects to document the ICH of Egypt in line with its mission to document Egyptian traditions from Egyptians’ daily lives.37

Collaboration with stakeholders

There is national collaboration between many governmental organisations, including the Higher Institute for Folklore and the Art House for Folklore and Performing Arts, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as the Egyptian Archives of Folk Life and Folk Traditions and Egyptian Society for Folk Traditions. Collaborating globally, in particular with UNESCO and ICOM as leading international organisations, can also provide technical support for the safeguarding of Egyptian heritage through various programmes and workshops focused on exchanging expertise gained through previous successful experiences, strategies and projects in international museums.

Building capacities

Capacity building that is relevant to safeguarding living heritage must target heritage practitioners and museum professionals alike. Training ensures that an effective and qualified workforce can be maintained inside Egyptian museums, promoting dialogue and co-creation activities. Measures to build the capacities of Egyptian museum professionals should have the following aims:38

- To deepen their sense of social responsibility for safeguarding and nurturing living heritage.

- To strengthen their knowledge about the forms of heritage that exist within their society.

- To develop their working relationships with intangible heritage bearers using sociology and anthropology workshops and sessions, as well as through participatory tasks with heritage practitioners.

Museum education: Object/heritage-based education

Education is central to the function and practices of museums, and both formal and non-formal education is of great importance for the transmission of intangible heritage. Incorporating the artefacts and collections of Egyptian museums into educational programmes to teach Egyptian heritage and history has strong potential to attract visitors and encourage their engagement, as artefacts embody the stories of real people from the past and shed light on cultural inheritances from past generations.

Building trust and creating spaces for heritage practitioners

Strong relationships between museums and heritage custodians are the result of frequent and continued interaction and emotional engagement based on reciprocity. Weak relationships can prohibit access to new information that evokes creativity and innovation.39 Museums can cultivate a trusting relationship with heritage custodians through dialogue based on the appreciation of their values and practices, and measures such as those outlined below which aim to help them revive their endangered traditions.

In addition, museums can support artists financially by providing them space to sell their handicrafts in museum shops and retail spaces.40 Outreach programmes can likewise be developed for museum professionals to support and engage with practitioners in their local communities. Most importantly, heritage practitioners should be assisted in safeguarding and transmitting their cultural traditions and skills in a contemporary context by focusing on cultural revival rather than archival documentation.

Traditional handcraft workshops in the museum campus

Training programmes, workshops and sessions can be led by heritage practitioners, giving space and opportunity for artisans and crafters to practice their trades and confirm the artistic value in this field in a historical, creative and modern environment. For example, each artisan can produce heritage products related to the museum’s collections as displayed to visitors in the galleries. At the end of the museum tour, each visitor can request a particular piece that they liked from the collection to take home as part of the tour. Through this interactive approach, visitors can experience the stories behind the pieces, representing the intangible side of Egyptian culture.41

Community-based exhibitions

Egyptian museums must go beyond their conventional role as mere places for the display of artifacts and become community-based spaces. By adopting a participatory approach that highlights their community and its values, they can act as stakeholders who have the authority to interpret the objects they display. The community exhibition approach aims to ensure community cohesion and well-being, by highlighting the distinctive heritage among the community members through the participation of these members in choosing the theme of the exhibition and the collection, in addition to writing the narratives of the exhibition to present their collective identity and memories. In this case, exhibitions can involve the practitioners of that heritage and the forms of knowledge and values linked to it.42 This promises to strengthen the relationship between museums and communities, providing the latter with a sense of inclusion and the opportunity to express themselves through storytelling and gallery talks.

Exhibitions can be developed about living heritage communities, which depend on practitioners as ‘first-person interpreters’, where sharing their story, values and culture serves as an interpretation tool. Additionally, videos and records accompanying the display can be used as an interactive approach to gallery interpretation. This will generate a dialogue, enabling visitors and museum professionals to connect personally and emotionally with the intangible stories of the museum collections.

Conclusion

Society has changed rapidly in the twenty-first century as a result of social transitions, economic and technological shifts, and the spread of globalisation and mass tourism. These all contribute to the contemporary challenges to the preservation of heritage, which have led to the destruction and loss of many cultural values and practices found within local communities. Globally, many institutions and organisations dealing with heritage, especially museums, have taken steps towards safeguarding and nurturing ICH and its communities. These steps have manifested in many approaches and forms ranging from developing strategies and plans to creating exhibitions and human/heritage-based activities.

Egypt is a country of tremendous diversity and unique intangible heritage and values. This heritage is notable for its integrity and authenticity, having been formed and passed down over thousands of years and influenced by other cultures and civilisations through both cultural integration and exchange. The lack of awareness about the forms and values of Egyptian living heritage, in addition to the lack of institutional engagement in ensuring the sustainability of Egyptian ICH, has a deeply detrimental impact on the stability and continuity of these forms and values. Furthermore, Egyptian museums have failed to reflect their heritage communities and the challenges they have been facing for decades.

Museums in Egypt still play their traditional role as institutions that preserve and display artefacts. However, in order to confront the threats to their country’s heritage and the challenges facing Egyptian communities, they must rethink and redefine this role, adopting more inclusive and participatory approaches. Effective efforts to safeguard their country’s living heritage in the twenty-first century will require museums to shift their focus from objects to human experience by integrating intangible heritage within their displays, functions and programmes. These measures are the surest means of protecting and supporting Egypt’s threatened cultural heritage.

Bibliography

Abdennour, Samia, Egyptian Customs and Festivals (Cairo: American University Press, 2007).

Ahmad, Hilal W., ‘Impact of Globalization on World Culture’, Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2 (2011), 1–4.

Alivizatou, Marilena, Intangible Heritage and the Museum: New Perspectives on Cultural Preservation (London: Routledge, 2016), http:// 10.1080/13527258.2014.913343.

Centre for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage, Briefing about CULTNAT (Cultnat.org, 2020), https://www.cultnat.org/About.

Derić, Tamara N., Neyrinck, J., Seghers, E., and Tsakiridis, E., Museums and Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards a Third Space in the Heritage Sector: A Companion to Discover Transformative Heritage Practices for the 21st Century (Bruges: Werkplaats immaterieel erfgoed, 2020).

Doyon, Wendy, ‘The Poetics of Egyptian Museum Practice’, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 10 (2008), 1–37.

Egypt State Information Service, Egyptian Heritage (Sis.gov, 2019), https://www.sis.gov.eg/section/10/1517?lang=ar.

Eladway, Salwa M., Azzam, Yousri A., and Al-Hagla, Khalid S., ‘Role of Public Participation in Heritage Tourism Development in Egypt: A Case Study of Fuwah City’, WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment Journal (2020), 27–43, http://doi.org/10.2495/SDP200031

El-Batraoui, Menha, The Traditional Crafts of Egypt (Cairo: The American University Press, 2016).

El-Saeed, Yomna, ‘The Egyptian Textile Museum’, Daily News Egypt, 1 October 2013, https://dailynewsegypt.com/2013/10/01/antique-fabrics-at-the-egyptian-textile-museum/.

European Union External Action, European and Egyptian Cooperation to Transform the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, Supported by the EU (Eeas.europa.eu, 2019), https://south.euneighbours.eu/news/european-and-egyptian-cooperation-transform-egyptian-museum-cairo/

Gad, Mustafa, Treasure of the Intangible Culture Heritage Part 2 (Sharjah: Sharjah Institute for Heritage Publications, 2019).

Gamal, Mohamed, ‘The Museums of Egypt after the 2011 Revolution’, Museum International (2015), 125–31, https://doi.org/10.1111/muse.12089

Gamal, Mohamed, ‘The Museums of Egypt Speak for Whom?’, CIPEG Journal: Ancient Egyptian & Sudanese Collections and Museums, 1 (2017), 1–11.

Gamal, Mohamed, Museology, its Creation, Branches and Impacts (Cairo: Al Araby Publications, 2019).

ICOM, Shanghai Charter (Icom.museum 2018), https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Shanghay_Charter_Eng.pdf

Kemp, Barry J., Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization (London: Psychology Press, 2006), https://doi.org/10.2307/530011

Kete, Molefi, Culture and Customs of Egypt (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002).

Khairbek, Maha N., Challenges of Globalization and its Relation with the Global Culture Heritage and Modernity (Tahawlat.net, 2014), http://www.tahawolat.net/MagazineArticleDetails.aspx?Id=825

Khalil, Mokhtar, The Nubian Language: How to Write It (Khartoum: Nubian Studies and Documentation Centre, 2008).

Manickavasagan, A., Essa, M. Mohamed and Sukumar, E., eds., Dates: Production, Processing, Food, and Medicinal Values (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1201/b11874.

Ministry of Antiquities, Antiquities Protection Act and Its Executive Regulations (Mota.gov.eg, 2022), https://mota.gov.eg/media/yafbwufg/%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A2%D8%AB%D8%A7%D8%B1-2022.pdf

Nakamura, Naohiro, ‘Managing the Cultural Promotion of Indigenous People in a Community-Based Museum: The Ainu Culture Cluster Project at the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum, Japan’, Museum and Society Journal, 3 (2007), 148–67.

National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Events (Nmec.gov.eg 2023), https://nmec.gov.eg/ar/past/.

Nwegbu, Mercy U., Eze, Cyril C. and Asogwa, Brendan E., ‘Globalization of Cultural Heritage: Issues, Impacts, and Inevitable Challenges for Nigeria’, Library Philosophy and Practice Journal (2011), 2–4.

Riggs, Christina, ‘Colonial Visions: Egyptian Antiquities and Contested Histories in the Cairo Museum’, Museum Worlds, 1:1 (2013), 65–84, https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2013.010105

Santova, Mila, Todorova-Pirgova, Iveta, and Staneva, Mirena, eds., Between the Visible and the Invisible: The Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Museum (Sofia: Publishing House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2018).

Septiyana, Iyan and Margiansyah, Defbry, ‘Globalization of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Strengthening Preservation of Indonesia’s Endangered Languages in Globalized World’ in Proceedings of the International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs (Dordrecht: Atlantis Press, 2018), pp. 8–10, http://doi.org/10.2991/icocspa-17.2018.23

UNESCO, Al-Sirah Al-Hilaliyyah Epic (Ich.unesco.org, 2008), https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/al-sirah-al-hilaliyyah-epic-00075

UNESCO, Handmade Weaving in Upper Egypt (Sa’eed) (Ich.unesco.org, 2021), https://ich.unesco.org/en/USL/handmade-weaving-in-upper-egypt-sa-eed-01605?USL=01605

UNESCO, Tahteeb, Stick Game (Ich.unesco.org, 2016), https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/tahteeb-stick-game-01189

UNESCO, Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Ich.unesco.org, 2022), https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

UNESCO, Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Ich.unesco.org, 2022), https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

UNESCO, Traditional Hand Puppetry (Ich.unesco.org, 2018), https://ich.unesco.org/en/USL/traditional-hand-puppetry-01376

Wieczorek,, Marta ‘Postmodern Exhibition Discourse: Anthropological Study of an Art Display Case’, Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 2 (2015), 19–24, https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v7i2.139

Zakaria, Nivine N., ‘What “Intangible” May Encompass in The Egyptian Cultural Heritage Context? Legal Provisions, Sustainable Measures and Future Directions’, International Journal for Heritage and Museum Studies, 1:1 (2019), 17–18, http://10.21608/ijhms.2019.119038

1 Iyan Septiyana and Defbry Margiansyah, ‘Globalization of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Strengthening Preservation of Indonesia’s Endangered Languages in Globalized World’, in Proceedings of the International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs (IcoCSPA 2017) (Dordrecht: Atlantis Press, 2018), pp. 8–10, http://doi.org/10.2991/icocspa-17.2018.23

2 Mercy U. Nwegbu, Cyril C. Eze and Brendan E. Asogwa, ‘Globalization of Cultural Heritage: Issues, Impacts, and Inevitable Challenges for Nigeria’, Library Philosophy and Practice Journal (2011), 2–4.

3 Hilal W. Ahmad, ‘Impact of Globalization on World Culture’, Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2:2 (2011), 1–4.

4 Salwa M. Eladway, Yousri A. Azzam and Khalid S. al-Hagla, ‘Role of Public Participation in Heritage Tourism Development in Egypt: A Case Study of Fuwah City’, WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment Journal (2020), 27–43, http://doi.org/10.2495/SDP200031

5 Menha El-Batraoui, The Traditional Crafts of Egypt (Cairo: The American University Press, 2016), pp. 1–2.

6 Maha N. Khairbek, Challenges of Globalization and its Relation with the Global Culture Heritage and Modernity (Tahawolat.net, 2014), http://www.tahawolat.net/MagazineArticleDetails.aspx?Id=825

7 Tamara Nikolić Derić, Jorijn Neyrinck, Eveline Seghers, and Evdokia Tsakiridis, Museums and Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards a Third Space in the Heritage Sector: A Companion to Discover Transformative Heritage Practices for the 21st Century (Bruges: Werkplaats immaterieel erfgoed, 2020), pp. 3–15.

8 Molefi Kete, Culture and Customs of Egypt (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002), pp. 1–3.

9 Samia Abdennour, Egyptian Customs and Festivals (Cairo: American University Press, 2007), p. 12.

10 Mokhtar Khalil, The Nubian Language: How to Write It (Khartoum: Nubian Studies and Documentation Centre, 2008), pp. 21–24.

11 Egypt State Information Service, Egyptian Heritage (Sis.gov, 2019) https://www.sis.gov.eg/section/10/1517?lang=ar

12 Mustafa Gad, Treasure of the Intangible Culture Heritage Part 2 (Sharjah: Sharjah Institute for Heritage Publications, 2019), pp. 866–70.

13 Abdennour, Egyptian Customs and Festivals, p. 22.

14 Gad, Treasure of the Intangible Culture Heritage Part 2, pp. 358–59.

15 El-Batraoui, The Traditional Crafts of Egypt, pp.1–2.

16 UNESCO, Handmade Weaving in Upper Egypt (Sa’eed) (Ich.unesco.org, 2021), https://ich.unesco.org/en/USL/handmade-weaving-in-upper-egypt-sa-eed-01605?USL=01605

17 Annamalai Manickavasagan, M. Mohamed Essa and Ethirajan Sukumar, Dates: Production, Processing, Food, and Medicinal Values (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2012), pp.5–6, https://doi.org/10.1201/b11874

18 UNESCO, Traditional Hand Puppetry (Ich.unesco.org, 2018), https://ich.unesco.org/en/USL/traditional-hand-puppetry-01376

19 UNESCO, Tahteeb, Stick Game (Ich.unesco.org, 2016), https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/tahteeb-stick-game-01189

20 UNESCO, Al-Sirah Al-Hilaliyyah Epic (Ich.unesco.org, 2008), https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/al-sirah-al-hilaliyyah-epic-00075

21 Barry J. Kemp, Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization (London: Psychology Press, 2006), p. 23, https://doi.org/10.2307/530011

22 Christina Riggs, ‘Colonial Visions: Egyptian Antiquities and Contested Histories in the Cairo Museum’, Museum Worlds, 1:1 (2013), 65–84, https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2013.010105

23 Mohamed Gamal, Museology, its Creation, Branches and Impacts (Cairo: Al Araby Publications, 2019), pp. 27–30.

24 Mohamed Gamal, ‘The Museums of Egypt Speak for Whom?’, CIPEG Journal: Ancient Egyptian & Sudanese Collections and Museums, 1 (2017), 1–11.

25 European Union External Action, European and Egyptian Cooperation to Transform the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, Supported by the EU (Eeas.europa.eu, 2019), https://south.euneighbours.eu/news/european-and-egyptian-cooperation-transform-egyptian-museum-cairo/

26 Mohamed Gamal, Museology, its Creation, Branches and Impacts (Cairo: Al Araby Publications, 2019), pp. 27–30.

27 Mohamed Gamal, ‘The Museums of Egypt after the 2011 Revolution’, Museum International (2015), 125–31, https://doi.org/10.1111/muse.12089

28 National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Events (Nmec.gov.eg, 2023), https://nmec.gov.eg/ar/past/

29 Wendy Doyon, ‘The Poetics of Egyptian Museum Practice’, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 10 (2008), 1–37.

30 Yomna El-Saeed, ‘The Egyptian Textile Museum’, Daily News Egypt, 1 October 2013, https://dailynewsegypt.com/2013/10/01/antique-fabrics-at-the-egyptian-textile-museum/

31 Between the Visible and the Invisible: The Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Museum, ed. by Mila Santova, Iveta Todorova-Pirgova and Mirena Staneva (Sofia: Publishing House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2018), pp. 2–8.

32 Ministry of Antiquities, Antiquities Protection Act and Its Executive Regulations (Mota.gov.eg, 2022), https://mota.gov.eg/media/yafbwufg/%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A2%D8%AB%D8%A7%D8%B1-2022.pdf

33 Nivine N. Zakaria, ‘What “Intangible” May Encompass in The Egyptian Cultural Heritage Context? Legal Provisions, Sustainable Measures and Future Directions’, International Journal for Heritage and Museum Studies, 1:1 (2019), 17–18, http://10.21608/ijhms.2019.119038

34 Marilena Alivizatou, Intangible Heritage and the Museum: New Perspectives on Cultural Preservation (London: Routledge, 2016), p. 22, http://10.1080/13527258.2014.913343

35 ICOM, Shanghai Charter (Icom.museum 2018), https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Shanghay_Charter_Eng.pdf

36 UNESCO, Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Ich.unesco.org, 2022), https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

37 Centre for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage, Briefing about CULTNAT (Cultnat.org, 2020), https://www.cultnat.org/About

38 ICOM, Shanghai Charter.

39 Tamara Nikolić Derić, Jorijn Neyrinck, Eveline Seghers, and Evdokia Tsakiridis, Museums and Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards a Third Space in the Heritage Sector (Bruges: Werkplaats immaterieel erfgoed, 2020), p. 13.

40 UNESCO, Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Ich.unesco.org, 2022), https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention.

41 Naohiro Nakamura, ‘Managing the Cultural Promotion of Indigenous People in a Community-Based Museum: the Ainu Culture Cluster Project at the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum, Japan’, Museum and Society Journal, 3 (2007), 148–67.

42 Marta Wieczorek, ‘Postmodern Exhibition Discourse: Anthropological Study of an Art Display Case’, Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 2 (2015), 19–24, https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v7i2.139