6. Mutrah Old Market, Oman: Analysis to Enhance a Living Heritage Site1

©2024 Mohamed Amer, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.06

Introduction

Culture and heritage are a means of conserving the inherited past, enabling it to inform the present and develop a future vision. This is achieved through tangible and intangible transmitted cultural heritage expressions and the community.2 Heritage cities serve to transmit cultural identity while accounting for the community’s contemporary needs and promoting creativity.3 According to the Hangzhou Declaration,4 from a socio-economic perspective, heritage supported by urban planning also encourages sustainability, cultural diversity and inclusion. Furthermore, as ‘nodes of economic activities for the creative industries’,5 they play a significant role in providing employment opportunities and generating local revenue.6

Mutrah old market, as a cultural heritage space, is a focal point of Omani living heritage. This chapter reviews the market’s cultural significance, highlighting its potential to serve as a key driver of sustainable development. For this research method, the chapter employs a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis, using qualitative methods such as direct observation and interview. The chapter examines the current situation of Mutrah old market as a case study on the preservation of authentic heritage value and assurance of integrity.

Living heritage and the community

In the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognition of cultural landscape (2013), certain authentic values valorise an interactive context between the human being and the surrounding cultural assets, both material and immaterial, to preserve ‘traditional techniques of [sustainable] land use and maintaining [cultural] diversity’.7 These processes of interaction within urban spaces create emotional connections with cultural meaning, continually reviving the lifelong learning memory of the community. Thus, cultural identity contributes to the city’s public image, which highlights the transmitted living heritage by creating ‘a mental map’ of the city’s memorable spaces and experiences. This offers a means of ‘allowing the city’s public image to emerge through social curation’.8

As stated in a 2015 UNESCO document, ‘a living heritage site is a measure to evaluate the depth of communication or interaction between cultural properties and the populations […] or what motivates the population to co-operate in achieving their common future visions’.9 In defining the characteristics of a living heritage site, it is necessary to consider the heritage context to identify the modifications in the community-based cultural heritage fabric over time, including ‘changes in the function, the space, and the community’s presence, in response to the changing circumstances in society’.

The significant role of the community in preserving living heritage was aptly summarized in 2003, at the first meeting of the Living Heritage Programme of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM):

Heritage does not belong to experts, or to governments […] which leave the public out of the process of defining their heritage and the most appropriate means to care for that heritage risk failure. Heritage belongs to the members of society whose values are reflected in the definition of heritage.10

Considering reflections on living heritage, Dr. Rhiannon Mason, a senior lecturer in museum, gallery and heritage studies at the International Centre for Cultural and Heritage Studies at Newcastle University, connects the cultural heritage and the cultural identity of local communities with the expression ‘sense of the place’, denoting an emotional rapport between the urban heritage space and the local community.11 This rapport can be observed in local efforts to preserve the authentic value of heritage sites and ensure their integrity via a triangle of communities—communities of place, communities of interest and communities of practice.12

Thus, living heritage is mainly an engine for the continuity of the local community which preserves it and sustains its values.13 The rapport between the community and its ‘tangible and intangible’ heritage should be enhanced by all key stakeholders, as should the community’s motivation and desire to preserve and safeguard expressions of heritage. This will generate new added value, mitigating human-induced impacts such as the effects of tourism, development projects, and new facilities and amenities. As a people-centred conservative management approach, it aims to sustain the main function of heritage buildings and the urban fabric by creating a link between the cultural identity and tangible forms of heritage space and empowering the local communities to actively participate in heritage conservation progress. This link strengthens the sense of ownership or custodianship that drives the local community to conserve its heritage.14

Heritage values of Mutrah old market

Investigating the traditional markets and their culture in the Arabian region, the term ‘market’ conceptually refers to ‘the place where baggage and goods are brought for sale and procurement… a point of convergence that gets people closer and translates […] the social rituals that they practice’.15 The significance of these traditional markets, as spaces of communities of practice, is not limited to their sold products; rather, these places also represent both tangible and intangible heritage and the authentic cultural knowledge of the local community. As a holistic recreational hub, the market represents a unique social, cultural and economic interactive living space that is perhaps the main tool for preserving the socio-cultural values and harmony of the Arabian community. Gradually, as a result of the cultural and economic pressures of globalisation, the role of the traditional market has diminished; the market has struggled to compete with contemporary ‘shopping’ culture, and at the same time, many historical market sites have deteriorated.16

Historically, Oman is considered one of the main examples of culturally mixed markets in coastal communities. The country’s high level of commercial activities gave traders an understanding of other cultures, allowing them to export and import traditional goods with foreign countries with permanent markets.17 Mutrah old market is located in the province of Mutrah, in the south of Muscat Governorate. It is a central commercial centre for Omani people, especially those who are living in Muscat. Although it is part of Omani culture and heritage, it brings together diverse cultures and traditions.

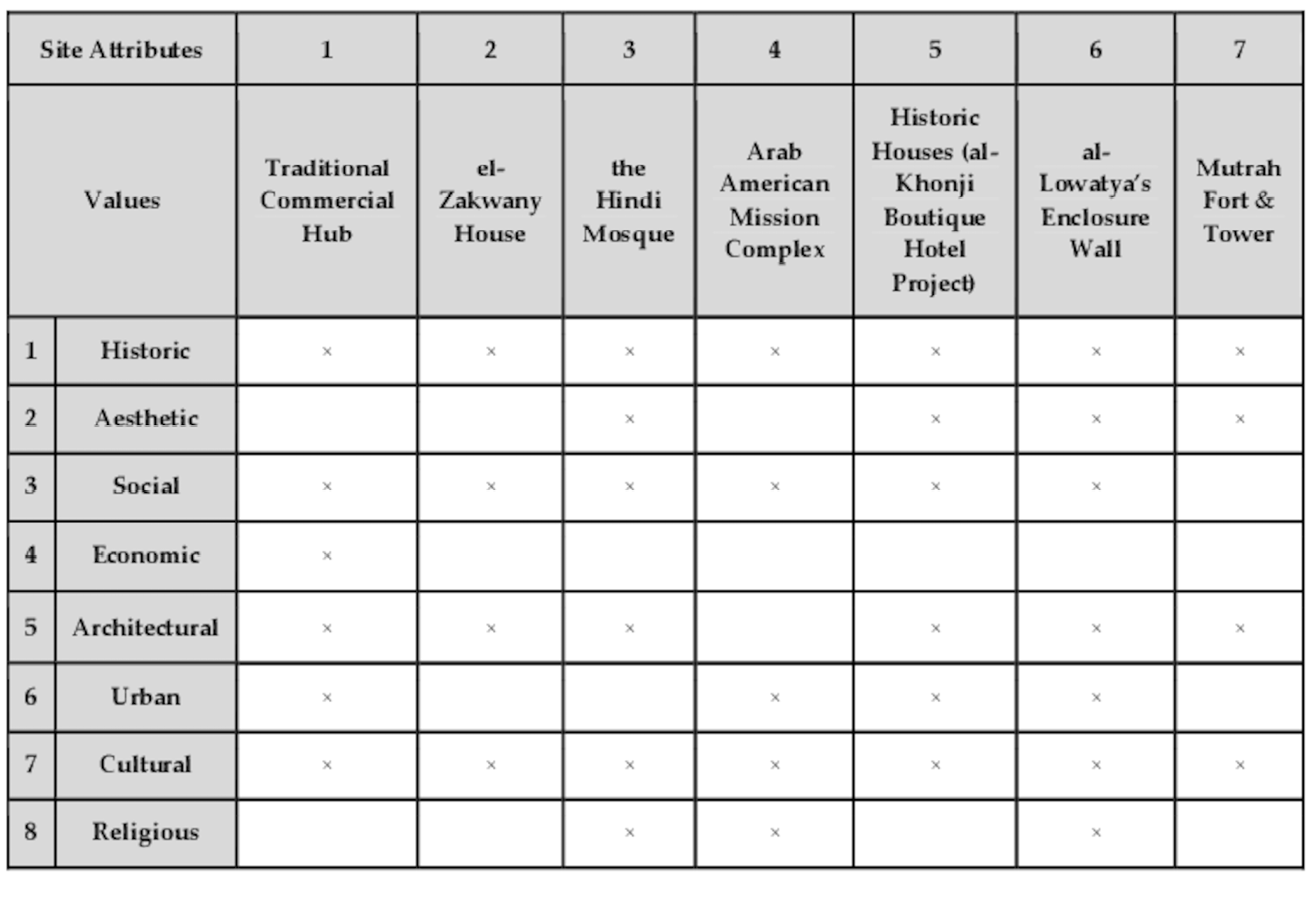

The attributes of Mutrah old market include the main road for traditional commercial activities; the Hindi Mosque; el-Zakwany House; the Arab American Mission complex (hospital/house/church) that was built in 1948; historic houses (al-Khonji Boutique Hotel Project); the ‘al-Lowatya’ enclosure wall; and the Mutrah Fort, gate and tower.

Table 6.1 The attributes and heritage values of Mutrah old market

Fig. 6.1 El-Zakwany House, Mutrah Fort and Historic Enclosure Wall. Author’s photograph, 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.

Historic value

Mutrah, as a coastal commercial hub with one of the oldest permanent markets in the Arab world, was founded during the historical period of the Magan civilization. However, the transmitted form of Mutrah Old Market was founded as a historical consequence of the construction of the Portuguese Mutrah fort in the sixteenth century in the centre of the old city of Muscat.18 Mutrah old market stands as a testament to diverse historical and cultural phases, boasting an urban fabric marked by the Omani tribes as well as Portuguese and British foreign forces in later centuries.

Urban-architectural value

The architectural significance of public markets has played a major role in preserving the identity of heritage cities in the long term.19 The spatial features of Mutrah old market include both the street markets located in urban districts and the roadside markets situated in rural villages. It is a covered market with ‘small-scale retail shops associated with urban market areas’.20 Thus, the historic buildings, spatial allocation and social interaction are important to consider, especially in redevelopment projects enhancing the traditional context of the market.21

As a historic market, the settlements and old market of Mutrah followed a common traditional architecture in Oman. It was formerly constructed of clay and palm leaves, which were a suitable material given the high temperatures and harsh environment of Oman. With the occupation of Mutrah by Portuguese forces in 1507, the continuity of the traditional architectural material and design of the old market was interrupted. The Portuguese influence in Oman manifested in the use of a regular-shaped stone-brick.

On the other hand, the old market has also a unique urban traditional characteristic. Remarking on the convergence of the Omani traditional architecture and the Portuguese architecture of Mutrah Fort, Al-Maimani described Mutrah as ‘enclosed by [a] wall, or houses built on the wall, with four towers in the corners, one gate in the southwest and one gate in the northeast facing the Corniche. There is a high probability that it was built inside one of the Portuguese forts’.22

Mutrah old market was Y-shaped around two hundred years ago. It is still on the same layout, functions and the sold traditional products up to now. It consists of two parts - Suq Saghir (‘the market of darkness’) on the one hand and the large market for wholesale goods on the other—which were connected by numerous pathways and alleyways. According to an urban profile from 1970, Suq Saghir extended from the Prophet Mosque or Lawatiya Mosque to Khawr Bimbah. There, as a part of Omani local identity, most textiles and fabrics, foodstuffs, cosmetics, plastic jewellery, fragrances and pharmaceuticals are sold.

Enhancing the urban-architectural values, the objectives of the Mutrah Redevelopment Master Plan (MRMP) (2005) and the market’s redevelopment project (2012, which were provided by Deloitte Touch Tohmatsu India Private Limited (DTTIPL) 23 aimed to preserve the character of the place as ‘a public market’ for Omani and international visitors and to enhance the thrift shops, arts and crafts, and other socio-economic activities, guaranteeing the market’s main functionality.24 The Muscat municipality renovated Mutrah old market during the regeneration project (2004–2005) and added some decorative motifs from Omani and Islamic architecture to the market’s architecture. To maintain its distinctive character, special emphasis was placed on the market’s ornamentation following the traditional Omani model. In addition, the market’s roads and alleys were paved for the comfort of citizens, residents, visitors and shoppers.25

Fig. 6.2 Changes of traditional material (including new building material and design). Development project 2004–2005. Author’s photograph, 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 6.3 Mutrah Market Old Gate after the development project that took place in 2004–2005. Author’s photograph, 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.

Socio-cultural value

Beginning in the sixteenth century, Mutrah was inhabited by the Khoja community, who worked as craftsmen in carpentry, weaving, shipbuilding and so on. They later became involved in trade and the governance of Mutrah village.26 In addition, it, as a costal public market, has been a space for exchanging social and cultural manifestations ‘within their respective communities, and […] integrated into local economic and social life.’27 Mutrah market was a social focal point for creating a strong relationship between the commercial tribe and local residents.

Mutrah old market is a unique example of a traditional historic market with socio-cultural value throughout its functional continuity, responding to the needs of the local community and the cultural diversity.28 As a historic, culturally mixed commercial hub, Mutrah attracted people of various ethnicities from Arab regions, Africa (specifically, Zanzibar), Baluchistan, Iran and India. The built context of the historical market hosts their crafts and craftsmanship, traditional products and customs. Thus, the market embodies the local history and cultural identity of the Omani community and its evolution.

Socio-economic value

Embaby emphasises the socio-cultural importance of conserving and developing the economic identity of historical markets, which ‘are considered one of the most important cultural memories of the past communities [and] the old lifestyle with its customs, goods and traditions, and the traditional commerce that were famous locally and regionally’.29

Historically and recently, the most common products sold in Mutrah old market are traditional Omani male clothes (Dishdasha), male embroidered caps (Kumah), the bamboo stick (Khayaran), headdresses (Massar), framed daggers (Khanjar), frankincense (Luban), incense, palm-made braziers, Arabian perfumes, Omani spices and Omani sweets (Halwa). These products contribute to preserving Omani citizens’ transmitted traditional lifestyle and cultural identity and pausing the impacts of modernization.30 Additionally, some Omani Halwa makers had workshops and shops. There was also a silver market, which was considered the most important part of Suq Saghir on account of its unique products.31

Focusing on the authentic socio-economic value of Mutrah old market the dates-based commercial activities were developed as the main Omani economic sector while preserving the social practices that were emerged as a result of cultural diversity. Scholz identifies dates as a primary ‘source of exchanging’ and dynamic economic domain in Oman up to the 1960s. Dates were important in agriculture and other indirect manufacturing activities. As Scholz notes, ‘cultivated in the oases of inner Oman and the Batinah coast, dates—packaged in woven sacks—were traded in Mutrah and exported via the port of Muscat. […] The organizers of the export of dates were primarily Hindu merchants in Mutrah. […] the Khojas involved in the date trade concentrated their activities on the collection and distribution of dates inside Oman’.32

SWOT analysis of Mutrah old market

Strengths

1. Authentic value/heritage significance:

As aforementioned assessing the heritage values, Mutrah old market is authentic and unique, consisting of historical layers that provide links with various civilisations of the past, especially those in the Middle East and Europe. Moreover, it has a collection of various buildings that are a harmonised example of architectural heritage. In contrast, the local urban fabric contributes indirectly to preserving the authentic value of the market and maximising the visiting experience.

2. Multi-functionality

Mutrah has a unique interactivity. It hovers between being a commercial space and a residential district and represents diverse socio-economic groups. As a picnic and tourist attraction, it is a suitable place for Omani residents and visitors to hike33 and enjoy leisure time with their families and friends.

3. Stable boundaries

The layout and borders of Mutrah old market have remained relatively unchanged. Recently, it has clear borders, facing Sultan Qaboos Port to the north, Mutrah Fort to the east, al-Lawatya walled enclosure and mosque to the west and Mutrah Police Station to the south. This connection with the Sultan Qaboos Port ensures that its boundaries cannot be altered in the future, preserving the layout without adding new urban extensions.

4. Well-known and promoted attraction

The old market is considered a landmark for both Omani residents and international visitors. Moreover, it is so near to the most common tourism facilities and services e.g. restaurants, cafes, hotels, local museums and so on.

Weaknesses

1. Lack of accessibility and limited capacity

According to direct observation (2018–2019), the traditional urban fabric of Mutrah old market has narrow subsidiary lanes, decreasing the number of local customers and international visitors that can access some shops. In addition, el-Bahari Road and the corniche separate traditional commercial activities from the oceanfront.

2. Lack of heritage interpretation

Unfortunately, Mutrah old market has insufficient interpretation tools, such as signage, banners, concise historical knowledge and guidance arrows which would allow visitors to better navigate and understand their historic surroundings.

3. Lack of security

Although there is an evacuation plan at the main entrance, the market generally lacks security for visitors, residents and goods.

4. Lack of effective cooperation among administrative authorities

Mutrah old market is administrated by various governmental bodies such as Mutrah Wali, Muscat governorate, the Ministry of Tourism and Heritage, and the Ministry of Defence. According to some conversations with local investors, there is insufficient coordination among them to the site’s management and development planning. Al-Maimani et al. have noted,

There is subsequent inadequate coordination of investment and management which has consequently a great impact on managing the resources of this traditional market. Mutrah municipality, Mutrah ruler Walli and other local authorities do not play an effective role in preserving this old market.34

As a result, there has been a ‘poor evaluation of the higher tourism potential of cultural heritage that could enrich the socio-cultural experience’.35

In addition, regarding the direct observation of the author, he noted a lack of community involvement in the development of cultural heritage, as local strategic partners and a business canvas for adaptive reuse. Subsequently, it might negatively affect the development of societal and cultural values in the future.

5. The demographic decline of Omani inhabitants

In 2019, Gutbertlet observed, ‘the majority of the vendors in Mutrah are expatriates […] from India, Pakistan or Bangladesh. Most of them live and work within walking distance.36 If Omani cultural policy is adapted to these foreign residents, ‘this movement away from the traditional fabric can lead to loss of identity’.37 In addition, Scholz has observed that:

The developments in Suq Saghir after 1974 have been outlined […] increasing numbers of customers who were Asian guest workers and by the decline in Mutrah of the wealthier and more discerning Omani categories of customers. They had emigrated to the new residential districts of the Capital Area or stayed away from this shopping district due to its inaccessibility by car.38

6. Lack of conservation and infrastructure 39

In the 1950s, Mutrah was incorporated as a part of a capital rather than an independent province. Subsequently, according to the Omani national development plan, Mutrah market and its cultural assets become associated with the Sultan Qaboos Port. This action impacted renovation projects, resulting in new facilities and amenities to accommodate the needs of international visitors and the introduction of modern materials and designs in the maintenance of Mutrah Fort and its towers. In 1970, the designation of Muscat as the Omani political capital likewise contributed to changes in certain traditional elements of the Mutrah old market, such as the clay buildings.40

Although ‘physical improvements could encourage [new globalised] businesses to open, and especially higher profile ones’41, these external investments and developments have led to the degradation of some cultural assets because of pressures related to customization and profitability.

Furthermore, the infrastructure does not adequately account for the frequency of heavy rain and high tides. Al-Maimani observed in 2013 that Mutrah exhibits visible physical deterioration. This deterioration has occurred because of a lack of planning, a lack of maintenance policies and a lack of heritage conservation criteria to address the destruction of historic buildings and their valuable heritage. Unfortunately, because of these environmental factors, these buildings are subject to intensive renovation and ‘the demolition of such valuable heritage buildings which in turn can lead to a loss of the traditional urban pattern. Each type of physical deterioration affects the socio-cultural and economic conditions of the resident community.42

|

|

|

Fig. 6.4 and Fig. 6.5 Lack of conservation criteria in Mutrah. Al Khonji House, al Khonji Boutique Hotels Project (Al-Khonji Real Estate and Development LLC). Author’s photograph, 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.

Opportunities

1. Possibility of partnership with local, provincial and federal

agencies to preserve the traditional markets in the Gulf Cooperation

Council (GCC) countries

Based on the heritage values and the aforementioned strengths, Mutrah can be not only a market or a traditional commercial centre but also a corporate entity emancipating the community involvement as a kind of people-public-private partnership. It has great potential to attract international funds to preserve Omani heritage, especially these kinds of traditional markets. Moreover, the characteristics of Mutrah old market may be suitable to enable partnerships with other provincial and international agencies for assessing and preserving traditional markets, as well as restoring, conserving and managing the old buildings, such as Al-Khonji Real Estate and Development LLC. This step could integrate the market’s cultural and traditional commercial agenda with that of other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and their neighbour states in the Middle East.

2. Suitable venue for traditional Omani festivals and events

Based on its historic activities, the market’s cultural identity has a great effect on Oman’s appeal to tourists. Thus, it might encourage the local craftsmen to establish a training centre to pass down these heritage skills to future Omani generations so that this appeal can be maintained. Moreover, al-Khonji settlements might host events representing the tangible and intangible cultural heritage as well as the traditional social practices of the Omani community.

Fig. 6.6 Old house after development; al Khonji Boutique Hotels Project (Al-Khonji Real Estate and Development LLC). Author’s photograph, 2018, CC BY-NC-ND.

Threats

1. Impacts of Over-tourism

Because of its location in front of Sultan Qabus Port, Mutrah old market usually receives higher numbers of international visitors during the winter as compared to the summer season. Thus, regarding the fragile carrying capacity of the market, those visitors may materially affect the conservation mandate of the market. Realizing the dimensions of glocalization and its impacts on cultural identity, this over-tourism might socially affect the Omani community’s traditional values and demographic structure, behaviour, lifestyle, and living standards. 43

2. Rapid urban development

As a result of the increasing number of Bangladeshi and Pakistani employees44 in the Mutrah market, irregular regenerated constructions have been built in recent decades which do not correspond to the traditional Omani style of the surroundings. Thus, there may be a push to completely reconstruct this historical market to make it more interactive realizing the cultural diversity and to provide a more efficient shopping environment.45 This could alter the features of the social spaces,46 as well as negatively affect the cultural identity and traditional urban fabric in Mutrah. Furthermore, the unorganised or visually unappealing buildings may generate visual pollution over the years.

3. Surrounding development projects

Due to previous rehabilitation and development projects, Mutrah, as a historical space, has lost most of its unique aesthetic potential, which stemmed from its picturesque qualities. According to an interview with Badriya al-Siyabi in 2018,47 a group of investment projects in Sultan Qaboos Port and al-Inshirah district includes restaurants, shopping malls and tourism and recreational facilities. The valorisation of these new branded investments will lead Mutrah old market to competition rather than collaboration which could result in endangering the intangible cultural heritage expressions and authentic cultural knowledge. Consequently, it might affect its socio-economic environment and its conservation in the short or long term.

4. Modernisation

In 1970, Mutrah was faced with rapid economic and infrastructural development and modernised urbanisation which especially impacted the urban fabric of Muscat as the political capital of Oman. New supermarkets and shopping malls were constructed, precipitating a confrontation between traditional Omani crafts and modern manufacturing. This has led to the loss of the cultural significance of traditional markets in the Omani community.48 Thus, the traditional socio-cultural identity of Mutrah faces a great modernisation-related risk to its significance and survival within a transformed context where ‘the most dynamic urban economic activities and high-income households abandoned many historic commercial centres, which often led to further deterioration and obsolescence of buildings and public spaces’.49

Conclusion

Mutrah old market has great cultural significance as one of the most well-conserved traditional markets in the GCC region. This historical landmark is one of the few remaining locations in Oman where it is still possible to discern local traditional architecture, both in terms of materials and design. As a traditional commercial space, it is a prime example of sustainability at the local level, transmitting the traditional knowledge and practices of the community.

Given its outstanding values, Mutrah has considerable potential to emerge as a key pillar of a successful sustainable development process.50 Successful historic markets create jobs both in their rehabilitation and operation, and the profits often stay in the community.51 Historically, Mutrah old market has been an economic engine connecting rural and urban residents. As Bryan Rich has pointed out, ‘the old market attracts customers from all economic backgrounds’,52 and it may support partnerships between non-profit entities and other organisations. These partnerships might encourage a financial balance between conservation and management activities and other profitable public goals.53

After reviewing the heritage values of Mutrah old market, it is apparent that the market requires a special urban rehabilitation policy. For instance, al-Khonji’s reuse project seeks to convert some historic houses into a boutique hotel. Such projects have significant potential to strengthen heritage contexts from a socio-economic perspective, including preserving the local cultural identity and bolstering urban infrastructure. However, they often counteract the aims of conservation by altering the inherited urban fabric.

Consequently, there is a need to unify the priorities and interests of the various stakeholders. Such hybridization or partnership would enable the development of an effective master plan including an overarching set of strategies and policies which reflects the collaboration of the local community, or investors, governmental bodies and public institutions, civic societies and the private sector.

To mitigate the negative effects of customization, the owners, especially local investors, should alter their marketing perspective, upgrading the quality of services, facilities and amenities, and adopting new social, economic, technological, and cultural policies.54 Hence, a visitor or consumer would be able to find imported modern products alongside traditional Omani products, aligning with the evolving requirements and the customized nature of the modern market in the face of direct and indirect competition.

Using cultural mapping as a heritage interpretation method to sustain a living heritage context, key stakeholders should collaborate to generate a range of creative cultural tourism activities, investments and entrepreneurial projects, rehabilitating and adaptively reusing the market as an engine for socio-economic development. This joint effort can interact with transmitted values, lessening the rapid modifications of cultural assets and preserving their significance.

Bibliography

Al-Maimani, Ahood Abdullah, Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs: the Case of Souq Mutrah, Muscat, Oman (MSc in Arts, Doha, Qatar University, 2014).

Al-Maimani, Ahood, Salama, Ashraf M., and Fadli, Fodil, ‘Exploring Socio-Spatial Aspects of Traditional Souqs: the Case of Souq Mutrah, Oman’, International Journal of Architectural Research (Archnet-IJAR), 8:1 (2014), 50–65.

Baram, Uzi, ‘Marketing Heritage’, in Encyclopaedia of Global Archaeology, ed. by Claire Smith (New York: Springer, 2014).

Caballero, Gabriel Victor, ‘Crossing Boundaries: Linking Intangible Heritage, Cultural Landscapes, and Identity’, in the Proceedings of Pagtib-Ong: UP Visayas International Conference on Intangible Heritage (UP Visayas International Conference on Intangible Heritage, Iloilo City, Philippines, 2017).

Court, Sarah and Wijesuriya, Gamini, People-Centred Approaches to the Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Living Heritage (Rome: ICCROM, 2015).

Cranshaw, Justin B., Luther, Kurt, Kelley, Patrick Gage, and Sadeh, Norman, ‘Curated City: Capturing Individual City Guides through Social Curation, in CHI ‘14- Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Toronto: Association for Computing Machinery, 2014), 3249–58.

Deloitte Touch Tohmatsu India Private Limited, ‘Pre-feasibility Study for Re-development of KR Market’, in Final Report, Sector Specific Inventory and Institutional Strengthening for Private-Public Partnership Mainstreaming for Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) (2012).

Dorr, Marica and Richardson, Neil, ‘Beyond Tradition’, in The Craft Heritage of Oman, vol. 2, ed. by His Highness Seyyid Shihab bin Tariq Al Said (Dubai: Motivate Publishing for the Omani Craft Heritage Documentation Project, 2003), 512–23.

Duany, Andres, Plater-Zyberk, Elizabeth, and Speck, Jeff, Suburban Nation: the Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream (Macmillan: North Point Press, 2000).

Embaby, Mohga E., ‘Sustainable Urban Rehabilitation of Historic Markets Comparative Analysis’, International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), 3:4 (2014), 1017–31.

Gentry, John Daniel, A Sustaining Heritage: Historic Markets, Public Space, and Community Revitalization (MA thesis, University of Maryland, 2013).

Gutberlet, Manuela, Searching for an Oriental Paradise? Imaginaries, Tourist Experiences and Socio-Cultural Impacts of Mega-Cruise Tourism in the Sultanate of Oman (PhD thesis, University of Aachen, 2017).

Hall, C. Michael and Lew, Alan A., Understanding and Managing Tourism Impacts: An Integrated Approach (London: Routledge, 2009).

Hosagrahar, Jyoti, Soule, Jeffrey, Girard, Luigi Fusco, and Potts, Andrew, ‘Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda’, in ICOMOS Concept Note for the United Nations Agenda 2030 and the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (HABITAT III) (Quito, Ecuador: International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), February 15, 2016).

ICCROM, ‘Background Paper Prepared for the First Strategy Meeting of ICCROM’s Living Heritage Sites Programme’, in The ICCROM’s Living Heritage Sites Programme First Strategy Meeting (Rome: ICCROM, 2003).

Lynch, Kevin, The Image of the City (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1960).

Mason, Rhiannon, ‘Heritage and Identity: What Makes Us Who We Are? ’, The Heritage Alliance, 5 November 2014.

Misiura, Shashi, Heritage Marketing, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 2006).

Miura, Keiko, ‘Conservation of a ‘Living Heritage Site’ a Contradiction in Terms? a Case Study of Angkor World Heritage Site’, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 7:1 (2005), 3–18.

Oman Ministry of Tourism, Trekking Path to Mutrah or Riyam (Destinationomen.com, 2005), www.destinationoman.com/pdf/trekking+routs2.pdf

Poulios, Ioannis, ‘Discussing Strategy in Heritage Conservation: Living Heritage Approach as an Example of Strategic Innovation’, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 4:1 (2014), 16–34.

Quartesan, Alessandra and Romis, Monica, The Sustainability of Urban Heritage Preservation: the Case of Oaxaca de Juarez (Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank, Institutional Capacity and Finance Sector, 2010).

Rahman, Md. Mustafizur, Islam, Shahidul, and Hasan, Mohammad Tanvir, ’A Redevelopment Approach to a Historical Market in Sylhet City of Bangladesh’, Civil Engineering and Architecture, 4:3 (2016), 127–138.

Santoro, Roberta Cauchi, ’Mapping Community Identity: Safeguarding the Memories of a City’s Downtown Core’, City, Culture and Society, 7 (2016), 43–54.

Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, The Program of Rehabilitation and Development of the Vernacular Markets in K.S.A (Riyadh: Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, 2010).

Scholz, Fred, Muscat—Then and Now: Geographical Sketch of a Unique Arab Town (Berlin: Schiler Hans Verlag, 2014).

Smith, Laurajane, ’Theorizing Museum and Heritage Visiting’, in The International Handbooks of Museum Studies: Museum Theory, 1st ed, vol. 1, ed. by Andrea Witcomb and Kylie Message (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015).

Smith, Laurajane, The Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, 2006).

UNESCO, Culture: Urban Future. Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development (Paris: UNESCO, 2016).

UNESCO, Operational Guideline for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2013).

UNESCO, Policy Document for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention (Paris: UNESCO, 2015).

UNESCO, The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies (Paris: UNESCO, 2013).

1 This research was conducted at the Department of Logistics, Tourism, and Service Management, Faculty of Business and Economics, German University of Technology in Oman (GUtech), which is affiliated with RWTH Aachen University, during the Winter Semester 2018–2019. The author appreciates the cooperative effort of Professor Heba Aziz, Dean of Faculty.

2 Uzi Baram, ‘Marketing Heritage’, in Encyclopaedia of Global Archaeology, ed. by Claire Smith (New York: Springer, 2014); Shashi Misiura, Heritage Marketing, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 2006); Roberta Cauchi Santoro, ‘Mapping Community Identity: Safeguarding the Memories of a City’s Downtown Core’, City, Culture and Society, 7 (2016), 43–54.

3 Laurajane Smith, ‘Theorizing Museum and Heritage Visiting’, in The International Handbooks of Museum Studies: Museum Theory, vol. 1, ed. by Andrea Witcomb and Kylie Message (Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2015); Laurajane Smith, The Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, 2006).

4 UNESCO, The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies, 2013.

5 Jyoti Hosagrahar, Jeffrey Soule, Luigi Fusco Girard, and Andrew Potts, ‘Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda’, ICOMOS Concept Note for the United Nations Agenda 2030 and the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (HABITAT III) (Quito, Ecuador: International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), February 15, 2016).

6 UNESCO, Culture: Urban Future. Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development (Paris: UNESCO, 2016).

7 Justin B. Cranshaw, Kurt Luther, Patrick Gage Kelley, and Norman Sadeh, ‘Curated City: Capturing Individual City Guides through Social Curation’, in CHI ‘14- Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, Canada: Association for Computing Machinery, 2014), pp. 3249–58.

8 Gabriel Victor Caballero, ‘Crossing Boundaries: Linking Intangible Heritage, Cultural Landscapes, and Identity’, in Pagtib-Ong: UP Visayas International Conference on Intangible Heritage (UP Visayas International Conference on Intangible Heritage, Iloilo City, Philippines, 2017); Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1960); Smith, The Uses of Heritage.

9 UNESCO, ‘Policy Document for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention’ (UNESCO, 2015).

10 ICCROM, ‘Background Paper Prepared for the First Strategy Meeting of ICCROM’s Living Heritage Sites Programme’, in The ICCROM’s Living Heritage Sites Programme First Strategy Meeting (Rome: ICCROM, 2003), p. 1; Keiko Miura, ‘Conservation of a “Living Heritage Site”: A Contradiction in Terms? A Case Study of Angkor World Heritage Site’, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 7:1 (2005), 3–18.

11 Rhiannon Mason, ‘Heritage and Identity: What Makes Us Who We Are?’, The Heritage Alliance, 5 November 2014.

12 Sarah Court and Gamini Wijesuriya, People-Centred Approaches to the Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Living Heritage (Rome: ICCROM, 2015).

13 ‘Emphasis is on the present, since “the past is in the present”. The present is seen as the continuation of the past into the future, and thus past and present-future are unified into an ongoing present (continuity).’ Ioannis Poulios, ‘Discussing Strategy in Heritage Conservation: Living Heritage Approach as an Example of Strategic Innovation,’ Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 4:1 (2014), 16–34.

14 Poulios, ‘Discussing Strategy in Heritage Conservation’.; UNESCO, ‘Operational Guideline for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention,’ Organization, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2013.

15 Ahood Abdullah Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs: the Case of Souq Mutrah, Muscat, Oman’ (Master of Science/Arts, Doha, Qatar University, 2014); Ahood Al-Maimani, Ashraf M. Salama, and Fodil Fadli, ‘Exploring Socio-Spatial Aspects of Traditional Souqs: the Case of Souq Mutrah, Oman,’ International Journal of Architectural Research (Archnet-IJAR), 8:1 (2014), 50–65.

16 Ibid.

17 Al-Maimani, Salama, and Fadli, ‘Exploring Socio-Spatial Aspects of Traditional Souqs: The Case of Souq Mutrah, Oman.’

18 Manuela Gutberlet, ‘Searching for an Oriental Paradise? Imaginaries, Tourist Experiences and Socio-Cultural Impacts of Mega-Cruise Tourism in the Sultanate of Oman’ (Doctoral thesis, University of Aachen, 2017).

19 Gentry, ‘A Sustaining Heritage.’

20 Md. Mustafizur Rahman, Shahidul Islam, and Mohammad Tanvir Hasan, ‘A Redevelopment Approach to a Historical Market in Sylhet City of Bangladesh,’ Civil Engineering and Architecture, 4:3 (2016), 127–138.

21 Al-Maimani, Salama, and Fadli, ‘Exploring Socio-Spatial Aspects of Traditional Souqs’.

22 Ibid.

23 Deloitte Touch Tohmatsu India Private Limited, Pre-Feasibility Study for Re-development of K R Market: Final Report, Sector Specific Inventory and Institutional Strengthening for Private-Public Partnership Mainstreaming for Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) (2012).

24 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula the Decline of Traditional Souqs’.

25 Ibid.

26 Fred Scholz, Muscat—Then and Now: Geographical Sketch of a Unique Arab Town (Berlin: Schiler Hans Verlag, 2014).

27 John Daniel Gentry, ‘A Sustaining Heritage: Historic Markets, Public Space, and Community Revitalization’ (Master’s thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, 2013).

28 Embaby; Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, The Program of Rehabilitation and Development of the Vernacular Markets in K.S.A (Riyadh: Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, 2010).

29 Mohga E. Embaby, ‘Sustainable Urban Rehabilitation of Historic Markets ‘Comparative Analysis,’ International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), 3:4 (2014), 1017–31.

30 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs’.

31 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs’; Scholz, Muscat—Then and Now.

32 Scholz, Muscat—Then and Now.

33 Oman Ministry of Tourism, Trekking Path to Mutrah or Riyam (Destinationomen.com, 2005), www.destinationoman.com/pdf/trekking+routs2.pdf

34 Al-Maimani, Salama, and Fadli, ‘Exploring Socio-Spatial Aspects of Traditional Souqs: The Case of Souq Mutrah, Oman’; Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs: The Case of Souq Mutrah, Muscat, Oman.’

35 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs: The Case of Souq Mutrah, Muscat, Oman.’

36 Gutberlet, ‘Searching for an Oriental Paradise? Imaginaries, Tourist Experiences and Socio-Cultural Impacts of Mega-Cruise Tourism in the Sultanate of Oman.’

37 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs’.

38 Scholz, Muscat - Then and Now.

39 ‘The concept of conservation has expanded from archaeological and heritage conservation to sites of cultural values conservation, also the conservation policies developed from heritage building adaptation to comprehensive urban context rehabilitation’. Mohga E. Embaby, ‘Sustainable Urban Rehabilitation of Historic Markets Comparative Analysis,’ International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), 3:4 (2014), 1017–31.

40 Al-Maimani, Salama, and Fadli, ‘Exploring Socio-Spatial Aspects of Traditional Souqs’.

41 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs’.

42 Ibid.

43 Gutberlet, ‘Searching for an Oriental Paradise?’; C. Michael Hall and Alan A. Lew, Understanding and Managing Tourism Impacts: An Integrated Approach (London: Routledge, 2009).

44 Bangladeshi and Pakistani people represent around 70% of the Mutrah market’s residents. Badriya Al-Siyabi, Impact of Sultan Qaboos Port Development Project on Mutrah Old Market, December 17, 2018.

45 Rahman, Islam, and Hasan, ‘A Redevelopment Approach to a Historical Market in Sylhet City of Bangladesh.’

46 Al-Maimani, ‘Socio-Spatial Study of Traditional Souqs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Decline of Traditional Souqs’; Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Jeff Speck, Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream (Macmillan: North Point Press, 2000).

47 Ms. Badriya al-Siyabi - CSR Manager, Muttrah Tourism Development Company LLC at Sultan Qaboos Port [company was developed by DAMAC (Private Sector) and Omran (Public Business Sector)], 2018.

48 Marica Dorr and Neil Richardson, ‘Beyond Tradition,’ in The Craft Heritage of Oman, vol. 2, ed. by His Highness Seyyid Shihab bin Tariq Al Said (Dubai: Motivate Publishing for the Omani Craft Heritage Documentation Project, 2003), pp. 512–23; Gutberlet, ‘Searching for an Oriental Paradise?’.

49 Alessandra Quartesan and Monica Romis, The Sustainability of Urban Heritage Preservation: The Case of Oaxaca de Juarez (Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank, Institutional Capacity and Finance Sector, 2010).

50 Embaby, ‘Sustainable Urban Rehabilitation of Historic Markets ‘Comparative Analysis.’

51 Theodore M. Spitzer and Hilary Baum, Public Markets and Community Revitalization (Washington DC: Urban Land Institute and the Project for Public Spaces, 1995).

52 Bryan W. Rich, ‘Structure, Hierarchy and Kin. An Ethnography of the Old Market in Puerto Princesa, Palawan, Philippines,’ Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5 (2017), 113–24.

53 Gentry, ‘A Sustaining Heritage’.

54 Rahman, Islam, and Hasan, ‘A Redevelopment Approach to a Historical Market in Sylhet City of Bangladesh.’