Introduction:

Tangible and Intangible Heritage

©2024 Lilia Makhloufi, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0388.00

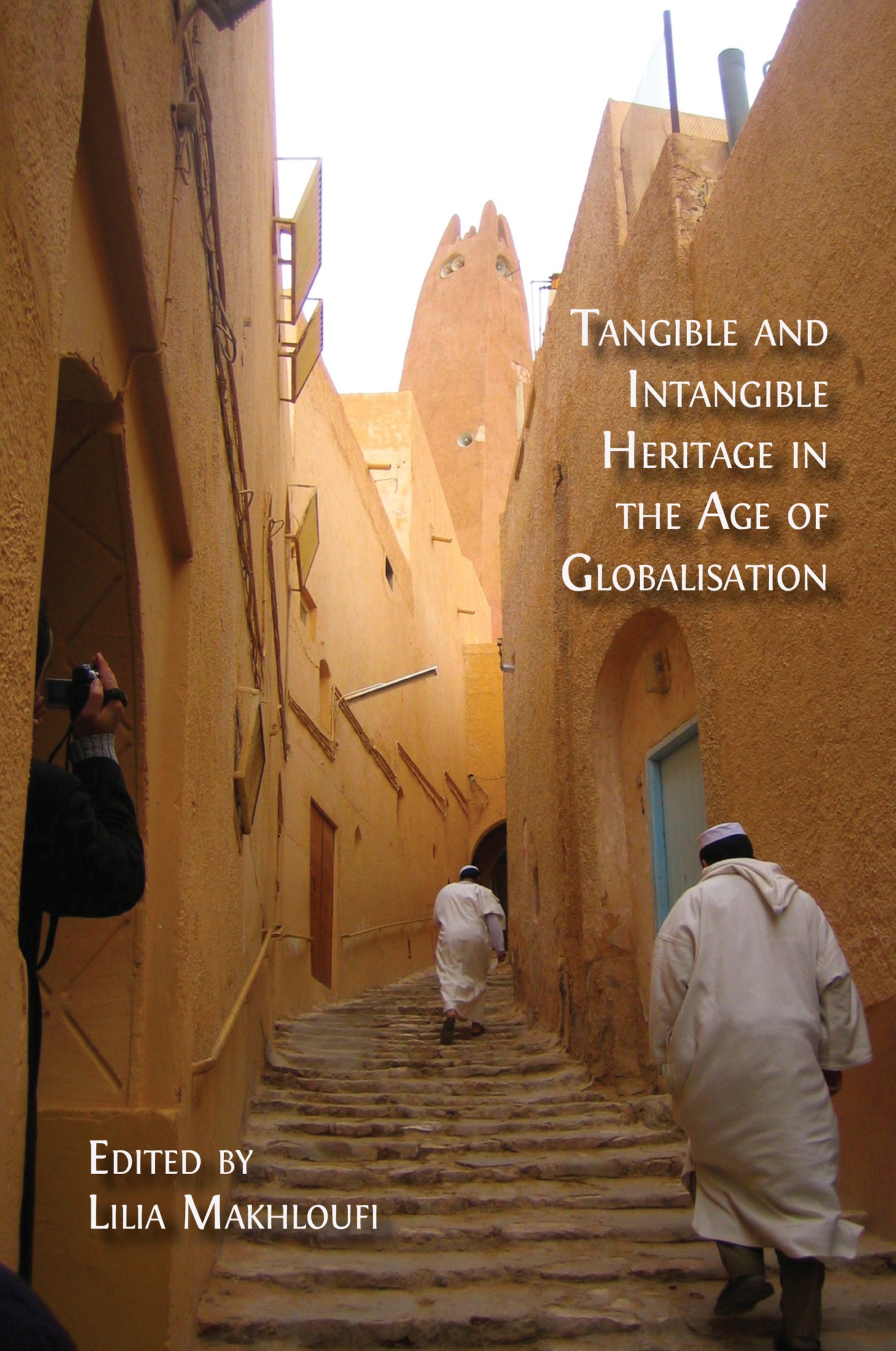

The old part of a city has always been a reference point in architecture, either from the urban perspective or from the building perspective. Traditional cities were shaped by a conceptual framework with conscious responses to environmental, urban and societal conditions. Over the centuries, this vernacular architecture encouraged a local style that manifested in ordinary houses with unified construction techniques and materials, and the harmonisation of the built framework and physical features.

This book analyses the architectural and urban spaces that shape cities’ tangible heritage, considering the urban networks, residential spaces and materials and methods of construction. The book also examines the parameters governing societies’ intangible heritage by defining: (i) individuals according to local identities, cultures and religions, (ii) behaviours rooted in local ways of life and social values, and (iii) practices including local customs, feasts and festivals.

Globalisation has developed the international standardisation of architecture and urban planning to the detriment of the representation of local identity and culture. In this sense, greater efforts have been made to protect local heritage and develop it through national and international organisations. However, the concepts of integrity and authenticity are challenged by international charters and academia. For instance, heritage sites are inscribed on the World Heritage List only if their integrity and authenticity are beyond question, ensuring their Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) in this way.

Today, heritage is subject to the transformation of cultures and the displacement of societies. Moreover, the number of studies on heritage has multiplied, as the currents of globalisation lend new exigence to its study and management. In this book, sixteen researchers from various disciplines―such as architecture, urban planning, landscape architecture, history, sociology, archaeology, heritage marketing, museum and cultural tourism―share their approaches to heritage, with perspectives on localities in the Middle East, North Africa, Eastern Europe, South America and Eastern Asia. More specifically, they focus on topics that will enrich the debate about the past, present and future of heritage in their respective countries and beyond.

Our collaboration on this book has sparked a fruitful exchange with the objective of redefining heritage as an interdisciplinary and intercultural concept. The contributors examine architectural, urban and cultural heritage, studying tangible and intangible parameters over time and discussing cultural challenges and opportunities. They analyse the conditions of the past with a focus on informing the present and the future. As a result, this book features case studies on Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chile, Egypt, Iran, Japan, Morocco, Oman, Syria and Tunisia, which are presented over the course of eleven chapters, structured according to the following themes.

The first part of the book brings together architects who give their perspectives on built heritage in Tunisia. Reflecting on residential characteristics, these chapters explore social and spatial practices in traditional dwellings.

Houda Driss analyses ancestral ways of occupying and appropriating space within the ‘troglodytic’ dwellings in the village of Beni Zelten, located in southeast Tunisia. Her research examines this architecture with respect to its natural environment and historical longevity, before identifying and analysing the socio-spatial practices inside these living spaces. The combination of theoretical and practical aspects of troglodytic spaces enables her to enumerate the activities practised in this context, which she then classifies according to the user type, degree of privacy and frequency of practice. In this way, she demonstrates how the underground dwellings in the Tunisian village of Beni Zelten reflect and respond to the natural environment, social factors and cultural values.

Meriem Ben Ammar focuses on architecture and town planning in the medina of Tunis, highlighting norms and rules relevant to the spatial organisation of houses, the material separation between neighbours and the management of the city in general. She analyses an archived manuscript dating from the eighteenth century on Hanafi law, written by Tunisian jurist Muhammad bin Ḥusayn bin Ibrahim al-Bārūdīal-Ḥanafī. This manuscript offers fair solutions to conflicts over property ownership, construction forms and housing issues between inhabitants and their closest neighbours. Over many centuries, this intellectual heritage encouraged a unified system of construction in the walled medina of Tunis, an organisation of its urban network and the preservation of its neighbourhood relationships.

Housing is a social space and includes the material context of social life.1 Yet, most of the time, housing is considered material data. However, we should be aware that housing is, above all, the product of a given society. This privileged place, in which people represent themselves and construct their lives, illustrates the codes of the society in which they live. By the intimacy that it preserves or the openness that it promotes, housing expresses a particular conception of social life. Moreover, the organisation of its spaces and the nature of its furniture represent a way of life and a culture, from which it is possible to discern the importance of the individual in every housing analysis.2

The second part of the book brings together architects, archaeologists and museum professionals, who give their perspectives on intangible components of cultural heritage in Iran, Egypt and Syria. More specifically, they examine local heritage, studying changes in collective memory over time, cultural challenges and opportunities.

In the twenty-first century, urban development effectively takes place according to socio-economic requirements. Local cultures, religious values and identities are increasingly neglected in decision-making processes in favour of the measurable and quantifiable data available in architectural and urban projects. This has resulted in the transformation of neighbourhoods, the transfer of local populations and the loss of many traditions and other cultural practices for present and future generations.

In this context, Sepideh Shahamati, Ayda Khaleghi and Sasan Norouzi consider the case of the Iranian city of Mashhad. In the last decade, this city—and more precisely, its centre—has undergone different urban transformations, which have had a considerable impact on both its built and cultural heritage. The case of Mashhad’s historic centre recalls the importance of reconceptualising intangible cultural heritage in decision-making processes and the challenges of its preservation in the twenty-first century, especially in the case of cities which were built and have developed according to spiritual and religious values.

Moreover, Heba Khairy analyses the museums of Egypt, a country renowned for its tangible and intangible heritage. Certainly, artefacts have been preserved in Egyptian museums since the twentieth century, but, to date, museum practice has been overwhelmingly concerned with tangible heritage, to the neglect of its intangible counterpart. As such, this research seeks to uncover viable solutions for the incorporation and development of intangible heritage in Egyptian museums. This is achieved by providing a conceptual prototype that will allow practitioners to safeguard and develop intangible cultural heritage, particularly in terms of living memory and communal identities.

Nibal Muhesen focuses on the case of intangible cultural heritage in Syria, which has suffered considerable destruction due to the conflicts of recent years. He underlines the importance of reviving all forms of local crafts, oral traditions, arts performance and old Souqs, with the objective of protecting the collective memory of communities and their cultural identities. He also suggests strategies for the protection of intangible cultural heritage, identifies challenges to its survival and emphasises the need for effective reconstruction efforts for all components of Syrian heritage.

The major obstacles to preserving tangible and intangible heritage in times of conflict are the subject of a great deal of contemporary discussion among researchers. They note the difficulties of safeguarding built heritage, on the one hand, and of protecting cultural heritage on the other. Indeed, several studies on archaeological sites, artefacts and historical monuments have been undertaken for the purposes of post-war damage assessment and the development of recovery policy. In the meantime, handicrafts, collective memories and cultural identities have suffered relatively less damage and could be more rapidly and easily revived.

The third part of the book brings together architects, historians and heritage management professionals who reflect on the cultural tourism potential in Oman, Algeria and Japan. They examine historic sites, studying the shape and content of their urban networks, buildings, infrastructure and spaces with respect to socio-cultural values.

Mohamed Amer examines the tangible and intangible heritage characteristics of the traditional market of Mutrah in Oman’s capital city of Muscat. He assesses its interactive historic, architectural, urban, social, economic and cultural values alongside their managerial features, in order to identify practical measures for the enhancement of this living cultural heritage, the effective preservation of Omani cultural identity, avenues for local socio-economic empowerment and sustainable cultural tourism. Here, Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analyses brought to light the internal and external factors that are favourable to achieving these objectives.

SWOT analyses have the potential to be a valuable tool in development processes and heritage conservation. Public spaces and streets in particular have a direct impact on the townscape, and their fundamental nature impacts the visual comfort of pedestrians (inhabitants, passers-by, tourists, merchants, etc.) and the attractiveness of the city for domestic and foreign visitors.

The historical and architectural significance of public spaces play an important role in preserving the identity of the heritage city. In this context, Lemya Kacha and Mouenes Abd Elrrahmane Bouakar investigate public spaces and their impact on the local community in the historic centre of Cherchell in Algeria, which has rich Punic, Roman, Arab-Andalusian, Ottoman and French heritage. The main objective of their analysis is to assess the perceptions and attractiveness of selected streetscapes among domestic tourists. Here, the Kansei Engineering method allowed them to quantify participants’ perceptions of streetscapes based on panoramic photographs. Through this method, which has significant potential in the field of sustainable cultural tourism and heritage conservation, the researchers found that the originality of the materials and the construction techniques are the main factors that have led to the preservation of heritage value. Moreover, the attractiveness of architectural heritage will contribute to enhancing both cultural and heritage tourism in the long term.

The important role of historical and cultural richness in attracting tourism is also evident in Japan, which has excelled in dealing with the living heritage. The principal agency for preserving Japan’s cultural properties has promoted churches as one of the region’s leading tourism destinations and integrated museums and souvenir shops to encourage touristic activities around these cultural and religious sites of memory. The objective of this strategy is to restructure the leisure industry and to moderate the impact of tourism on the local community lifestyle.

In this context, Joanes Rocha explores the concept of the ‘site of memory’, with a comparative case study of the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Amakusa, and their nomination for the World Heritage List. Although the study focuses on Catholic churches, it also considers local communities, their private sites and their significant contribution to the preservation of local history and religious practices and traditions. A comparative analysis allows different social, cultural and religious expressions of an intangible nature to be distinguished as a mechanism to strengthen local identity and to develop sustainable tourism in these historic and religious sites with their specific memorial aspects.

The fourth and final part of the book brings together architects and historians with perspectives on heritage sites in Morocco, Chile, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The research in these chapters reveals the challenges faced when preserving cultural heritage within specific historical, environmental and political contexts.

Urban heritage, with its tangible and intangible components, is of vital importance for present and future generations as a source of social cohesion, cultural diversity, collective memory and identities. With this in mind, Assia Lamzah analyses the dualities between Orientalism and Occidentalism and their consequences for heritage in postcolonial Morocco. She questions the dichotomies long used in architecture and urban planning, such as traditional versus modern or oriental versus occidental, and discusses the ways they have been developed and normalised. This is done through a case study of Jemaa el-Fna Plaza in the Marrakesh medina, where precolonial conceptions and spatial construction have been continuously renewed to create a contemporary heritage site that corresponds to the needs of the local population and adapts to a dynamic Moroccan society.

Moreover, Fabiola Solari Irribarra and Guillermo Rojas Alfaro consider the vulnerability of urban and industrial constructions and their deterioration in arid climates. They question the authenticity of Humberstone and Santa Laura Salpeter Works in Chile according to the original fabrics and structures of this industrial heritage, the integrity of which has been harmed by the natural environment over time. In the last decade, several security measures and consolidation and stabilisation works were undertaken to conserve the tangible assets of this site. While conservation works partially compromised the original fabric and material aspects of the site, this change can be viewed as positive because the material decay of these mining complexes coexisted with efforts to keep them standing. In this way, these buildings and the choices made in conserving them bear witness to the key historical, industrial, and social processes associated with the heritage site.

Nowadays, heritage management and discourse are subject to contemporary challenges involving different actors, and the specific relationships of local populations and tourists to these heritage sites. For the local authorities as well as for researchers, these sites are important parts of national, historical and cultural heritage.

In this context, Aliye Fatma Mataracı analyses the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo and discusses the major challenges of preserving tangible and intangible heritage in war and post-war periods. She raises the difficulties of safeguarding and renovating the museum as a built heritage asset on the one hand, and of protecting and maintaining its collections as cultural heritage on the other. Particular attention is also given to the term ‘national’ and its usage in the English title of the museum, in reference to the former Austro-Hungarian and local appellations of the museum. This heritage site has been exposed to different political, social, economic and religious contexts. However, it promotes the expression and representation of the cultural heritage of people from Bosnia and Herzegovina and offers an alternative for the preservation and maintenance of the country’s ethno-religious identities and cultures.

The publication process for this book has proven to be challenging, as it was necessarily carried out via emails during the COVID-19 pandemic, while contributors were in different countries and time zones. However, in overcoming these obstacles and seeing the publication through to its completion, I found my mind opened to other ways of thinking about tangible and intangible heritage, the significance of its theories and practices, and the ways cultures of heritage can be developed and fostered. I hope that this book will have a similar impact on the readership of Open Book Publishers.

1 Lilia Makhloufi, ‘Globalization Facing Identity: A Human Housıng at Stake—Case of Bab Ezzouar in Algiers’, in Proceeding Book of ICONARCH II, International Congress of Architecture, Innovative Approaches in Architecture and Planning (Konya: Selçuk University Faculty of Architecture, 2014), pp. 133–144 (p. 142).

2 Lilia Makhloufi, ‘Inhabitants/Authorities: A Sustainable Housing at Stake—Case of Ali Mendjeli New Town in Constantine’, in Sustainable Architecture & Urban Development, SAUD 2010, vol. 1, ed. by S. Lehmann, H. Al Waer & J. Al-Qawasmi (Amman: The Center for the Study of Architecture in the Arab Region & University of Dundee, 2010), pp. 367–383 (p. 372).