13. The Lived Experience of Radical Acceleration in the Biographical Narratives of Exceptionally Gifted Adult Musicians

©2024 Olja Jovanović et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0389.13

Introduction

If giftedness manifests itself in the exceptional speed at which one acquires the skills and knowledge of a given domain (e.g., Winner, 1996), then this can be particularly salient in the realm of music. Not only is this a domain where giftedness may emerge very early on (Winner, 1996), it is also one in which those identified as gifted can progress at a pace far greater than that expected by the regular music curriculum (Gagné & McPherson, 2016). In this chapter we address the experience of radical acceleration as reflected in the narratives of four musicians who were identified as exceptionally musically gifted during childhood. To provide a context for analysing their narratives, we will first review the major points about the development of musical talent, as well as about the educational practice of acceleration.

The development of musically gifted individuals into elite musicians

The complexity of the process that may ultimately produce an elite musical performer is captured in current models of talent development (e.g., Gagné & McPherson, 2016; Subotnik & Jarvin, 2005), both in terms of the multiple stages and transitions that are deemed to constitute this process, and in the multitude of factors thought to contribute to it. Contrary to the popular image of a ‘born artist’, these models assume a lengthy process of honing abilities into competencies and into expertise, to eventually reach the level of eminence and artistry (Subotnik et al., 2016). Moreover, they regard the process of talent development as extending beyond formal education and encompassing the various phases of building a career as a professional musician (Gembris & Langner, 2006). As depicted in McPherson and Lehmann’s (2012) model, the first three stages of musical development (sampling, specialisation, and investment) fulfil the purpose of ‘getting there’, yet there is also a final maintenance stage which is about ‘staying there’, that is, preserving the status of the successful musical performer.

At any point in this process, the level of performance is determined by numerous factors, as is the likelihood and speed of transitioning from one level to the next (Subotnik et al., 2016). According to Gagné and McPherson (2016), the achievement of expertise in music depends not only on the level and nature of the aptitudes that feed directly into the talent development process, but also on various intrapersonal and environmental catalysts, as well as factors related to the developmental process itself (see Chapter 12 in this volume). Moreover, as pointed out by Subotnik et al. (2016), it appears that different constellations of factors are relevant at different stages of talent development, and that the relative weight of these factors tends to shift over time. Thus, while success in a field almost always requires both cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and employs various types of abilities, there is a tendency for social skills, creativity, and practical intelligence to gain in importance and outweigh more analytical and technical skills as the talent development process moves towards its higher stages.

Acknowledging that each progression from one stage to the next is fraught with specific challenges, a review of the literature also suggests that two transitions stand out as being particularly difficult. The first is that of entering what McPherson and Lehmann (2012) call the ‘investment stage’, which means prioritising music over other endeavours and making the decision to pursue music as a profession. For highly gifted and precociously developing individuals, this ‘career decision’ is often made at a very young age (Gagné & McPherson, 2016; Jung & Evans, 2016), in fact before the child has had a chance to seriously consider alternative life paths, so that ‘it’s only later in adolescence that prodigies can begin to doubt themselves and their commitment to music performance’ (Subotnik et al., 2016, p. 287). The second great challenge is the individual’s professional integration once they have completed their musical education (Gaunt et al., 2012), that is, the transition from studying music to entering the job market and the music industry (Gembris & Langner, 2006; Jung & Evans, 2016); again, in the case of musically precocious students, this may happen as early as adolescence. The above-mentioned shift in the weight of factors that lead to success is especially obvious at this point in talent development, because it is with this transition that an array of ‘non-musical’ competencies come into play (Gaunt et al., 2012; Gembris & Langner, 2006; Jarvin & Subotnik, 2010), and personality factors tend to outweigh other variables.

In sum, while the speed of progress through the various stages of musical talent development may largely depend on the person’s level of musical abilities (Gagné & McPherson, 2016), the desired outcome of becoming a professional musician is also contingent upon other characteristics and competencies, such as personal charisma, determination, and social and practical skills. Even for those with an exceptional gift in music, the talent development process may assume various individual trajectories and lead to outcomes other than world-class eminence.

Playing fast forward: Accelerated talent development

One way to ensure a positive outcome of the talent development process is, of course, the provision of adequate educational interventions, and a major intervention in accommodating gifted learners is acceleration. Basically, acceleration consists in adjusting the pace of formal learning to meet the precocious development and abilities of gifted learners. Although considered essential in gifted education (Mayer, 2005; Rogers, 2007; Winner, 1996), it is also surrounded by some controversy, especially when it comes to its grade-based forms (e.g., early entrance to school/college, grade skipping), wherein the student is placed within an older age cohort. Nevertheless, in the field of academic giftedness, acceleration—including radical grade-based acceleration of 2+ years—is a well-researched intervention (Dare et al., 2019; Neihart, 2007), with findings of quantitative studies usually testifying to its beneficial effects, both short-term and long-term, on students’ academic achievement, motivation, and productivity (e.g., Rinn & Bishop, 2015; Sayler & Brookshire, 1993). Available findings also suggest that acceleration does not entail any significant socio-emotional risks, yet we must agree with Gronostaj et al. (2016) that little is known about these effects, and that a large-scale quantitative approach cannot depict the complexity of the experience of grade skipping from an individual perspective. Several qualitative studies have sought to address this issue, revealing that while the experience of grade skipping is generally a positive one, accelerands may also experience some difficulties in social adjustment (Jett & Rinn, 2019) and dealing with the high expectations put on them (Mun & Hertzog, 2019).

Addressing acceleration in musical education presents us with a paradox: radical acceleration is more common, but far less explored in this field than others, and the literature seems to provide more questions than answers about how acceleration shapes the development of musical talent (Gagné & McPherson, 2016). To further complicate things, radical acceleration in musical schooling may require corresponding adjustments to regular education: thus, for a musically precocious teenager to enter the conservatory, their general schooling must also often be accelerated, although the student may not be academically brilliant. Also, while for academically gifted students the choice is whether to skip grades or not (without having to leave regular school), musical accelerands have to deal with the decision of committing themselves to music rather than anything else. Thus, acceleration can add further challenges and complexities to the process of talent development in music.

Aims

Given that radical acceleration is often part and parcel of musical talent development, yet little is known about how it shapes and affects this process, our study focused on the lived experience of acceleration from the perspective of adult musicians—those who have reached the final stages of the talent development process. We were specifically interested in how they experienced the two critical developmental transitions mentioned above—deciding to study music at university level and starting a career as a professional musician (i.e., entering the investment and the maintenance stage; McPherson & Lehmann, 2012)—since they made these transitions at a rather young age.

We were further interested in whether the experience of radical acceleration and the process of talent development would bear any specific features related to the socio-cultural background of the accelerands—more precisely, to their origins in the Western Balkans, specifically Serbia. We raised this issue on the assumption that the experience of acceleration may greatly depend on the structure and organisation of music education (cf. Gagné & McPherson, 2016), which is different in Serbia from other investigated countries (see Nogaj & Bogunović, 2015). We also had in mind that musicians from Serbia who are now in their young adulthood were born and/or raised in politically and socially turbulent times which were characterised by a devaluation of culture—a fact that might have left a specific mark on their experience of developing a talent in classical music. Finally, given that Serbia is a relatively small country, and success in classical music usually means moving abroad, we reasoned that the talent development process might include yet further challenges for musical accelerands from this country.

Method

To uncover the meanings that gifted musicians ascribe to their experiences of radical acceleration, we chose a narrative approach—a method which entails an exploration of the narrator’s motivation, values, and meaning-making systems along a temporal dimension (Spector-Mersel, 2011), and ultimately allows for an in-depth understanding, while also ensuring methodological and scientific rigour (Leung, 2010). The Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Music, University of Arts in Belgrade approved the research.

Participants

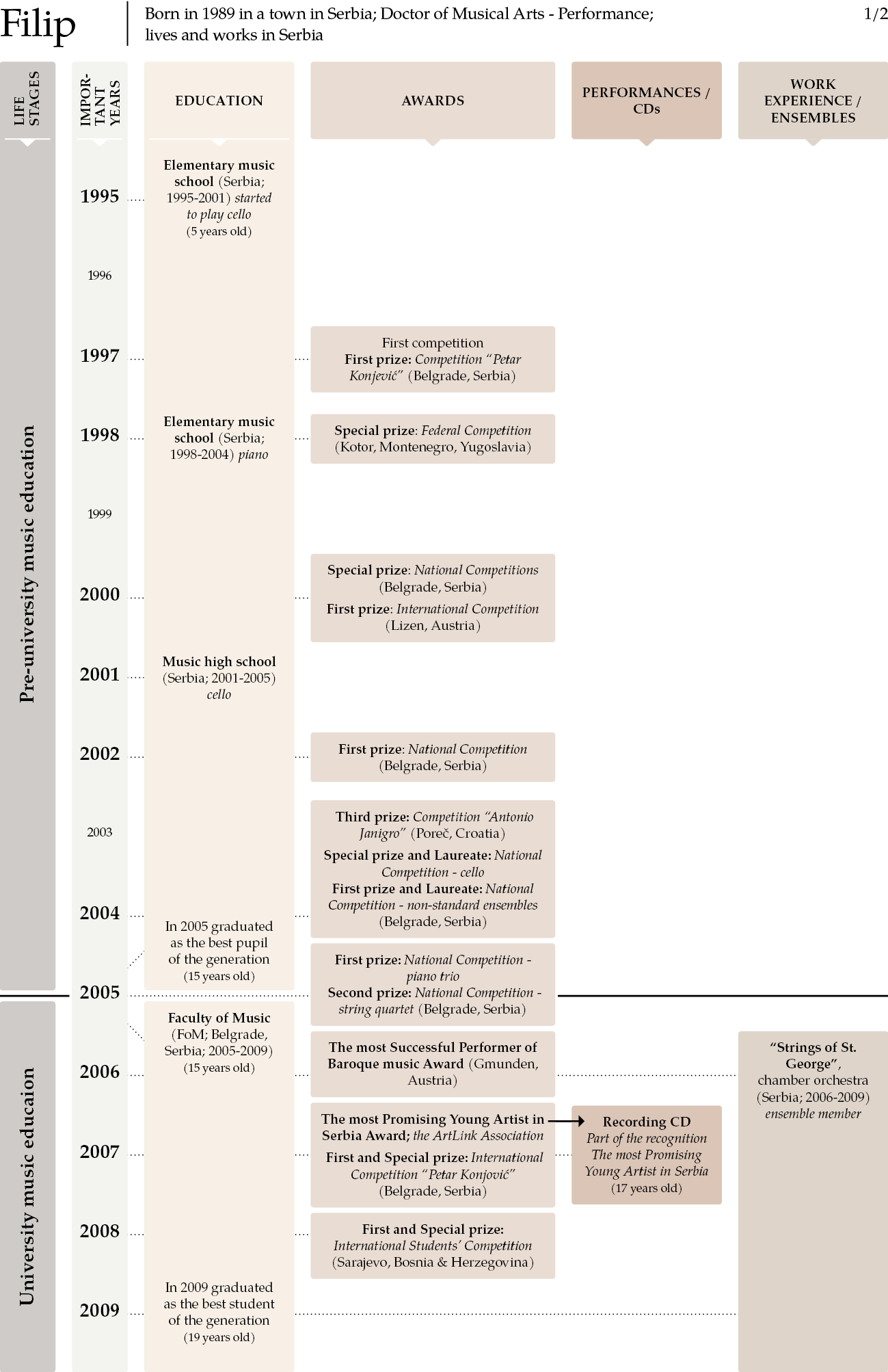

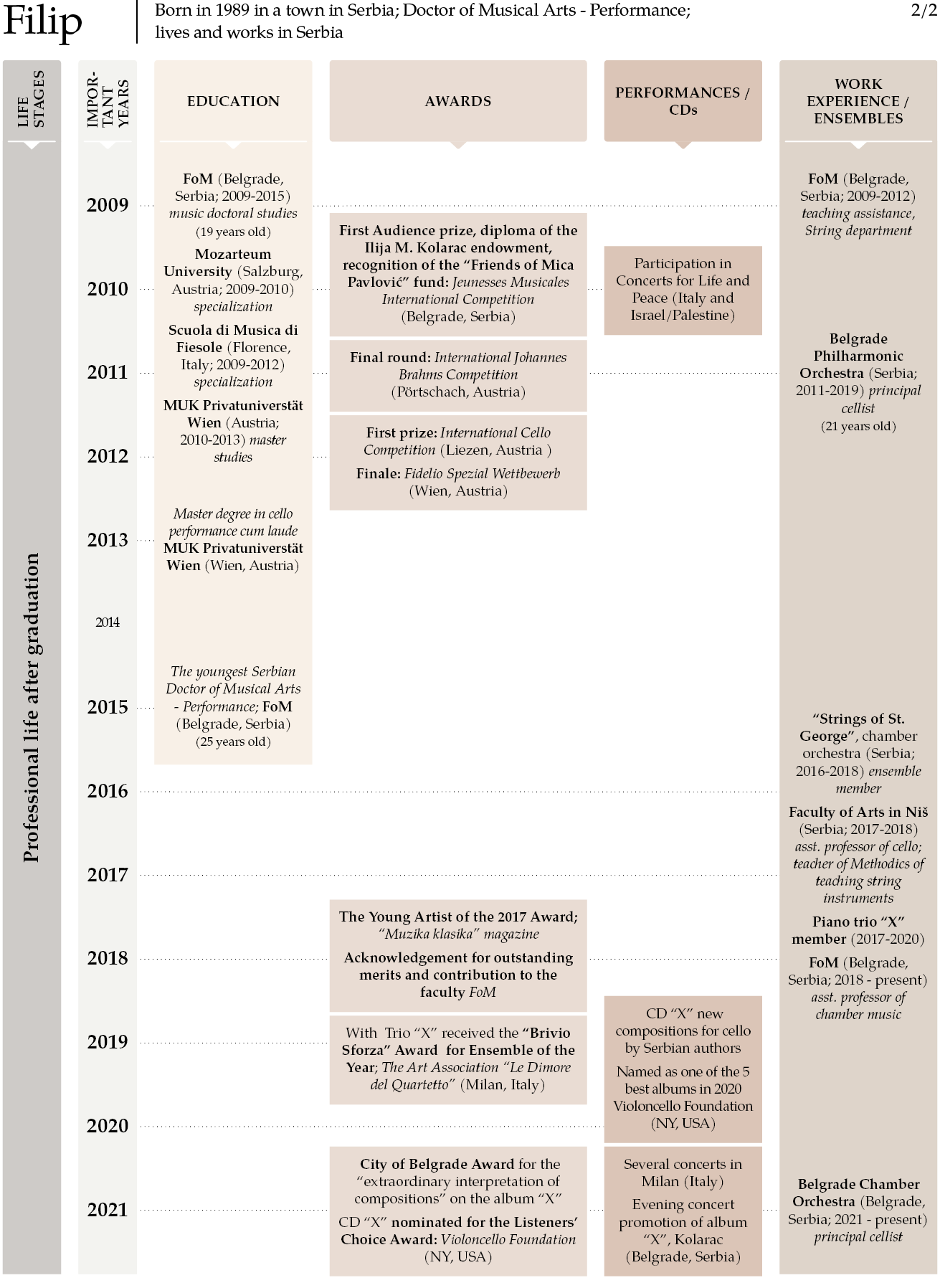

The study included a purposive sample1 of four participants, aged 32–45 years, who were identified early in their lives as exceptionally musically gifted, and who, in terms of talent development, are now amidst the artistic, concert-career developmental phase (Manturzewska, 1990). Each participant had the experience of radical acceleration in their music education. Further information about the participants’ characteristics is provided in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Characteristics of participants

|

Gender |

Instrument |

Starting MHE Age |

Starting MHE Country |

Starting MHE Age |

MHEc, country |

Currently stationed, country |

Ageb |

||

|

Graduate studies |

Postgraduate studies |

||||||||

|

Marija |

Female |

Piano |

6 |

Serbia |

15 |

Serbia, France |

Serbia, France |

France |

45 |

|

Ana |

Female |

Violin |

4 |

Serbia |

15 |

Serbia |

Serbia, USA |

Serbia |

43 |

|

Marko |

Male |

Violin |

6 |

Serbia |

14 |

Serbia |

Serbia, Germany |

Germany, Denmark |

37 |

|

Filip |

Male |

Cello |

5 |

Serbia |

15 |

Serbia |

Serbia, Austria, Italy |

Serbia |

32 |

a Names were changed to preserve the anonymity of participants.

b Age of participants at the time of data collection.

c Abbreviation for “music higher education”.

An online version of this table may be viewed at https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/0e1f026f

Data collection

Data were derived from semi-structured narrative interviews focusing on the experience of acceleration in the context of the participant’s overall life story. The interviews started with the instruction: ‘Please tell me the story of your life. You may start with the year 19** (year of birth) and then describe, as detailed as possible, those aspects of your life that you consider important.’ The interviews were facilitated by a biographical timeline previously prepared by the researchers (see the Appendix to this chapter). The questions following the storytelling aimed at prompting participants to reappraise their experiences, reconnect their past with the present, reveal the interaction between experience and context, and put ‘meaning’ into the foreground for conscious examination (Leung, 2010). At the end of the interview, participants were asked to think about the life stories they had told, to identify important ‘chapters’ in them, and to give titles to those chapters (cf. Thomsen & Berntsen, 2008).

Data collection took place in 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, via the web-based video-conferencing tool Zoom. The content was audio recorded with the participants’ consent. Reflexive memos kept by the researcher facilitated the process of analysis and reduced the potential for bias (Birks et al., 2008). The interviews lasted 70–100 minutes and resulted in 87 pages of interview transcripts.

Data analysis

We approached the data inductively, following the four-stage process of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (for details, see Smith & Osborn, 2004). Analysis began with a close interpretative reading of the first case where initial codes were annotated in the comments. These initial codes were translated into emergent themes at a higher level of abstraction. This process was repeated for each case. Patterns were documented cross-case and transformed into a narrative account, supported by verbatim extracts from each participant. The analysis of the timelines provided a contextual understanding of the individual participants’ experience of acceleration. At this point, a researcher who had not participated in the data analysis independently judged the coherence between the findings and the transcripts, ensuring the trustworthiness of the study.

Although participants’ narratives covered the period from early childhood to the present, and yielded six recognisable ‘life chapters’, in line with the above-stated focus of our study we will here only present the results concerning two of these: entering music education at university level and starting professional life as a musician (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Overview of the two life chapters and themes

Results

The findings portray how our exceptionally gifted participants perceive and reflect on the part of their lives from the time they entered music higher education institutions (MHEI), up to their first steps as independent professionals in the music industry, and they encompass information on selected events, people, and the overall socio-historical-cultural context. These portrayals are organised around the key themes identified in the participants’ narratives.

Maturing as a musician

Entering university at a young age

The transition to university is a challenging period that involves navigating a number of important new tasks: making friends, establishing independence, and developing a different approach to learning (e.g., Brooks & DuBois, 1995). While all four participants entered university early, at 14–15 years of age, their experiences of this transition differ. Like Jet and Rinn’s (2019) participants, both Marko and Filip reflected on some of the negative impacts on their social development and romantic relationships, and on missing out on certain experiences that are common for adolescents. Ana, however, talks about being cared for by her fellow students, since she was amongst the youngest in the group. From the perspective of academic tasks, all participants emphasise that they had difficulties mastering certain (non-musical) subjects at university level:

I have to admit that, in my opinion, acceleration has very negative consequences, especially in some social aspects, since my fellow students were much older than me… My voice, for example, has been changing […] when I took solfège during the entrance exam, […] my voice cracked non-stop, the others laughed. It was very difficult for me to bear it then. Not to mention I started smoking at the age of 14, since I was surrounded by people who smoked, I thought it was something extremely cool. […] In essence, there are some things that a person should experience before entering university, developing that certain level of awareness. (Marko)

I remember we had Psychology and Pedagogy in the second year, Sociology in the third year. That was hell for me because, I mean, at 14–15 I didn’t understand anything. No… That terminology. It was terrible for me. (Ana)

During this period, learning from a ‘master teacher’ is seen as a privilege and presumes a close relationship, loyalty, and trust. Our interviews were rich with data about recognising excellent music teachers and moving to their institutions, even if they were in a different country or continent.

I was ranked first in the entrance exam and graduated in three years. Since Professor M. was about to retire, and I wanted to graduate in his class, I had to merge my third and fourth year at the university—which I did. […] so at the age of 17 I enrolled in master studies and at 19 I obtained my master’s degree. (Marko)

Juggling studies and career

Since our participants were already accomplished young musicians by this stage, they had a variety of professional engagements which required that teachers adjust the schedule for them, but they still had to juggle their studies with their professional activities. Looking back on this intensive period, all participants observed that it was only later in life that they ‘had discovered the beauty of procrastination’, as Filip described it. During that period, our participants sought to expand their presence in the field of music and establish themselves in the professional community:

So, I travelled a lot. And there was always some, some pressure. I mean, it was physically demanding, since you had to get up [early], and do your duties, and studies, and travel to those countless masterclasses and seminars, and find money for that… (Filip)

Identity foreclosure

Although the transition between childhood and adulthood usually provides an opportunity to explore one’s past, current, and potential selves and take ownership of one’s life (Erikson, 1956), our participants do not remember questioning their choice of a music career during adolescence. In Marko’s words, they ‘didn’t have the luxury of questioning’ it, because by that age they had already invested long hours into music practice. Also, due to their outstanding accomplishments in music, their identities as (future) musicians were positive and stable, albeit foreclosed:

I mean, it was kind of natural. You don’t think about it at all. (Ana)

I didn’t question myself. Well, how could I have questioned myself—I had been in music education for 15 years at that time, I was playing the cello and I really wasn’t interested in anything else. (Filip)

In my mind, I have never wondered if I should be something else. But it’s not like passion guided me. No! It was just like that. I did it. I was good at it, obviously. And you get into a machine where there are no such questions anymore. That’s it. That’s my life. But after a while, you start asking yourself: ‘Could I do something else now?’ (Marija)

The participants’ narratives revealed a strong tendency to be perfect as musicians, illustrating Dews and Williams’s (1989, p. 46) statement: ‘Music, perhaps more than any other artistic pursuit, demands a high level of perfection from those hopeful of being successful in it.’ This perfectionism is rooted in familial and cultural expectations (cf. Flett et al., 2002). For example, Ana described how coming from a well-known musical family set high standards for her, while Filip mentioned that being aware of his parents’ material and non-material investments into his career raised the bar for him. Sometimes, high standards are perceived or explicated as a feature of the music profession or certain positions, as in Marko’s case.

Because classical musicians must always be top-notch. Everything has to be perfect, always; you always strive for an ideal and perfection. So, you always demand the maximum from yourself—the best. That is why we are so insecure. In the end, never satisfied. […] A mistake is not an option. It cannot happen. And that burdened me a lot. […] It can happen to anyone, but it cannot happen to me, since I was a concertmaster, since I’m his daughter…2 (Ana)

This is an act that I still can’t understand— They [his parents] sold the apartment we lived in to obtain the money for buying me an instrument. […] It was a burden for me: that someone is selling an apartment, automatically means asking a lot from me. However, in 2003 it happened that I went to a competition in the Czech Republic and did not pass to the second round [laughs]. They had just bought a new instrument for me, so it should have been great. Right? However, I did not live up to those expectations and that’s it. […] I may have been too young to really understand the burden of it all. (Filip)

Of course, [giggles] the reason for such a contract is that I am expected not to make any mistakes. Never. Which is a lot of pressure, of course. And, since it is still a radio orchestra, from the moment I take my seat in the orchestra, everything is recorded. […] …nerves of steel [laughter]… (Marko)

Seeking refuge in music

Some participants’ university studies partly took place during the specific circumstances of the bombing of Serbia in March–June 1999. These participants reported that music and intensive practice had a protective role, shielding them from the disturbing political and social reality:

I think it’s good because we were really dedicated to art, to music. In the circumstances in which we grew up that saved us mentally. (Ana)

For Marija, music was literally a way out: she had earned a scholarship abroad where she continued her studies. However, she recognises that she was not prepared for this sudden transition, having to leave her friends and family and adapt to a new life and environment. Moreover, being in constant transition created an everlasting sense of longing, with music as the only constant:

So, all these, all these accelerations, in fact, have created in me some… a kind of lack… I call it [lacking of] a home. I mean, of one’s country, and city, and Mom and Dad, and… Which has become a very, very important place for me, psychologically. My problem or my… a fact that I have to… that I deal with, more or less well, depending on the moment… Like when you go home, and you sense some familiar smell, and it feels right. Well, that’s what I’m looking for. I mean, that’s my whole life. And the only place that offers me that, in fact, is the piano. (Marija)

Starting to live the life

Entering the profession at a young age

Radical acceleration also meant gaining an early entrance into the profession and highly prestigious professional roles from a young age. This transition was experienced differently depending on the type of position. Those who held stable positions that required working with other people (e.g., as a concertmaster) had to master non-musical and particularly social skills relevant for their new role; those who became independent musicians had to learn how to be more visible and how to attract an audience. Generally, participants reported feeling they lacked non-musical skills (e.g., foreign languages, communication, leadership):

At the age of 19, I started working—permanent employment—and in fact, I haven’t spent a single day without being permanently employed since then […] In fact, I can freely say that I have been working since I was 14. (Marko)

I was already known in professional circles at the time of my studies, so the director of the Belgrade Philharmonic had heard me [play], knew that I was from a musical family. And they called, suggesting that I audition for the position of the concertmaster, I was 19 at the time. And it was, like: ‘Well, why not.’ […] But, since being a concertmaster is not just about playing well… You practically have to manage 100 people. […] Then I learned communication [skills] along the way: how to manage people; they look upon me as an authority. 100 people! You have to be, I mean… [laughter] It’s very strange. Challenging, at the same time, at 20 years of age. No, it wasn’t easy. (Ana)

Experiencing the gap between education and profession

In line with the notion that ‘Only those who can reinvent themselves will make the leap between childhood giftedness and adult creativity’ (Winner & Martino, 2000, p. 107), participants reflected on how, at this stage, they were expected to make a shift from technical proficiency to innovation and creativity, to give their playing a new meaning. For some of the participants it was a transition from the role of performer to that of a meaning maker, and their musical education had not prepared them for this. As Bennett (2013) explains, music education traditionally focuses on virtuosic performance, and is unlikely to encourage broader views of what it means to be a successful musician:

And that’s the problem that you’re… totally unprepared for… You come, in fact… as if you were heading into space. You have to speed up, like [makes ‘vroom’ sound] when a rocket is launched. Because you had a drill for 20 years. Literally. And then, they drop you into some airless space and you are so, aaaaah… (Marija)

Experiencing new professional horizons

After university, life begins. The completion of studies and the expertise gained were experienced as an expansion of their professional horizons that gave them opportunities to explore different musical genres and activities (cf. Palmer & Baker, 2021). At the same time, this also meant taking responsibility for oneself, freedom in decision-making, and financial independence (cf. Subotnik et al., 2016), which are the hallmarks of adulthood (Arnett, 2000):

And then, there was a period when I started making a living, making a living from what I was educated for [laughs]. Um, then it became my life (How should I put it?), professionally. I was no longer dependent on anyone, not only financially, but I also found my own path… (Marija)

Reminiscent of Bennett’s (2007) findings, our participants describe themselves as being engaged in different professional activities and in different fields of music, whether they were independent musicians or employed full-time as performers. They ascribe their professional progression to a combination of social capital, high quality performance, and positive chance:

I needed to get a new instrument. This one wasn’t satisfactory anymore… That was a student’s instrument and I needed a better one for my career. Well, I was lucky … In 2012, I met a lady in Italy who was a financial adviser there, at that school. She heard me play among other students, that is, cellists. And she showed great affection for me and approached me saying that my instrument is awful, but that I play wonderfully and that she will organise something for me. And she really did, a few months later, an event in Milan where she invited me. […] She invited the elite from that city who were ready to support a young musician… one from Serbia — a third-world country [laughter], or fifth-world [through laughter]. And then, they raised funds… And then I got a new instrument. (Filip)

At this stage, Marija and Marko are living and working abroad. Both of them described how while they have easily become recognised for their music skills, they feel at the same time that they will always be foreigners:

You are simply not one of them. Never. I have a passport here [France], but still, I am not a product of their school. And you have that strange name, hard to pronounce. I have never experienced any political…, like: ‘You are Serbs’. However, ‘You are the Foreigner’ is present. No matter who you are, it is always there, …you will always be the Foreigner. (Marija)

Experiencing diversification of private roles

The gendered dynamics that came into play while participants were talking about their past and current selves and their plans for the future, resonate with the findings of previous studies (Cook, 2018; Teague & Smith, 2015), including those focused on adults who are gifted in other domains (Ferriman et al., 2009). For the female participants, the central focus of their career-related plans was to accommodate for childbearing and parenting: they tended to look for professional positions that provide more stability (e.g., a position at a university) and/or more time for family roles (e.g., teaching). On the other hand, this interaction between career-related plans and other aspects of life was not salient in the accounts of the male participants.

It has speeded up a lot, in fact. And, also, when the children are born, and responsibilities to them, and the husband, and the household, and… So, it’s just a lot of roles that you perform… A lot of roles. And in each of them, at least that’s how we were brought up, I think militarily: ‘Work (uh), wash the ashtrays, but do the best you can.’ Like that. So, even now, with that kind of responsibility in me, with 15 roles that I perform during the day; I have to be perfect in each one. That is, in fact, a bit too much for an ordinary person. (Ana)

Discussion

The ‘gauntlet was thrown down’ by McPherson (2016), who called for more research about prodigies in socio-cultural milieus other than English-speaking ones. This study deals with exceptional musical talents coming from the Western Balkans whose education was radically accelerated, and who told us their life stories while looking back at their musical development. This chapter focused on two important transitions of musical prodigies: firstly, when they make conclusive career decisions (Jung & Evans, 2016) about their music education, and, secondly, later on, when they take on the role of professionals.

Radical acceleration from an individual perspective

Like other qualitative research on acceleration (Jett & Rinn, 2019; Mun & Hertzog, 2019), this study revealed the experience of radical accelerands to be quite complex. On the one hand, early identification and promotion of talent may instil a feeling of security in young accelerands, with the domain of music acting as a ‘secure base’ or ‘place of comfort’, which one can always resort to. On the other hand, it may bring potential health risks, such as early substance abuse due to the pressure to ‘act older’, as well as the risk of identity foreclosure, that is, of automatically extending the identity of a ‘child prodigy’ into that of an ‘exceptional performer’ (Evans & McPherson, 2017) without acknowledging the fragile nature of the prodigy or the fact that there is more to life than ‘talent development’. Moreover, while opening up great possibilities for musical development (Martin, 2016), radical acceleration can also reduce the opportunities the prodigy has to acquire knowledge and skills in other areas, and thus can limit their chances of a career change—which is a considerable drawback given the uncertainties and demands of a musical career, even for those who are exceptionally talented. Finally, while radical acclerands consistently ‘win’ in social comparisons of ability (being younger, but progressing faster in the field of music than most other students), and thus may construct positive identities as musicians (Davidson, 2017), they also experience a ‘loss’ when it comes to their sense of belonging to a peer group (rather than just having ‘fellow students’).

Radical acceleration from a contextual perspective

Given that context is viewed as critically important for both understanding and developing talent (Plucker & Barab, 2005), the question is how (and how much) it affects the experience of radical acceleration? Firstly, our participants’ narratives reveal how the nature of music education in Serbia has affected their musical and personal development. The strong emphasis on developing musical skills and performing publicly, in a highly structured educational environment, is recognised by our participants as both an advantage and a disadvantage. On the one hand, this educational approach has helped them to become easily recognised as outstanding music performers in different contexts, transcending national, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds in music practices (Folkestad, 2017); on the other hand, it has failed to build the psychosocial skills (e.g., communication, leadership, self-regulation) that are necessary for long-term success in a music career (Jung & Evans, 2016). Secondly, living in a country where state funding for the development of musical talents is scarce has made it necessary for the individual to be proactive to ensure the resources for practising and performing; to look for enrichment activities abroad; and, consequently, to also master foreign languages, as a tool for becoming a member in relevant professional and social communities. Thirdly, the strong dedication to music, to the development of musical skills, and to meeting the expectations in this particular field also provided some protection against the adverse political and social events of the immediate environment. Music was an ‘escape hatch’ from the grey reality of serious political upheavals. Yet, at the same time, the exclusive commitment to music entailed a specific kind of vulnerability: the continual need to confirm one’s worth and identity as the ‘perfect musician’. Finally, a special challenge for our prodigies was moving to another country and adjusting to the language, culture, and customs of a new place, while at the same time ‘mastering the field’ (Subotnik & Jarvin, 2005): making networks, arranging concerts, and finding funds. Although, in the participants’ narratives, migration seemed to open up different experiences of the world and music for them, it also meant changing their relationship to their homeland and settling into a new environment, which sometimes persisted in reminding them that they were ‘foreigners’. Still, music was there to provide some comfort and to evoke the feeling of being at home, of having a solid identity and place in the world.

Limitations and future directions

This study is based on participants’ retrospective accounts, which provided an opportunity to situate the experience of acceleration within the broader framework of their life stories; to explore what they perceive as critical events and how they interpret causal connections between events; and how they create links between the events and aspects of themselves (McLean, 2005). Nevertheless, focusing on past experiences in a specific context calls for caution when drawing implications for the here and now. Additionally, we aimed to describe the experience of radical acceleration for musically gifted individuals of a particular cultural context. In order to gain a fuller understanding of both the musical and general development of accelerands, cross-cultural research is needed (Ziegler et al., 2018). We thus hope that future research on the radical acceleration of musically gifted individuals will allow us to collect their stories as they are emerging, across lifespans and diverse socio-cultural milieus.

Conclusion

Four adult musical prodigies reflected on their experiences of radical acceleration against the backdrop of their lives, navigating the complex socio-political context of Serbia, in addition to the complexity of early professional engagements, and an accelerated educational journey. Rather than just being an ‘educational intervention’, acceleration shapes numerous aspects of life, not limited to professional careers and artistry, but affecting social, emotional and identity development. We have found multiple examples of evidence for the notion that ‘context matters’, which further highlights the need for more research on the development of musical talents in different parts of the world and to explore different ways in which acceleration can happen (McPherson, 2016). Although certain similarities were found among the four individuals in the centrality of music for identity, refuge, and motivation, our findings also highlight the idiosyncrasy and complexity of the talent development process, indicating the need to provide individualised support to the maturing musical prodigy.

Acknowledgement

It was a worthwhile research endeavour to learn how adult musical prodigies reflect on their experiences of radical acceleration against the backdrop of their lives. We are grateful to Istra Pečvari and Zlata Maleš for their assistance in recruiting the participants, as well as to our participants for sharing their life stories with us.

References

Arnett, J.J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Bennett, D. (2007). Utopia for music performance graduates. Is it achievable, and how should it be defined? British Journal of Music Education, 24(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051707007383

Bennett, D. (2013). The role of career creativities in developing identity and becoming expert selves. In P. Burnard (ed.), Developing creativities in higher music education: International perspectives and practices (pp. 234–244). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315885223

Birks, M., Chapman, Y., & Francis, K. (2008). Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987107081254

Brooks, J.H., & DuBois, D.L. (1995). Individual and environmental predictors of adjustment during the first year of college. Journal of College Student Development, 36(4), 347–360. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232514967_Individual_and_Environmental_Predictors_of_Adjustment_During_the_First_Year_of_College

Cook, J.A. (2018). Gendered expectations of the biographical and social future: Young adults’ approaches to short and long-term thinking. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(10), 1376–1391. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1468875

Dare, L., Nowicki, E.A., & Smith, S. (2019). On deciding to accelerate: High-ability students identify key considerations. Gifted Child Quarterly, 63(3), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986219828073

Davidson, J.W. (2017). Performance identity. In R. MacDonald, D.J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (eds), Handbook of musical identities (pp. 364–382). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0020

Dews, C.L.B., & Williams, M.S. (1989). Student musicians’ personality styles, stresses, and coping patterns. Psychology of Music, 17(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735689171004

Erikson, E.H. (1956). The problem of ego identity. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 4(1), 56–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306515600400104

Evans, P., & McPherson, G.E. (2017). Processes of musical identity consolidation during adolescence. In R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (eds), Handbook of musical identities (pp. 213–231). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0012

Ferriman, K., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2009). Work preferences, life values, and personal views of top math/science graduate students and the profoundly gifted: Developmental changes and gender differences during emerging adulthood and parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(3), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016030

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Oliver, J. M., & Macdonald, S. (2002). Perfectionism in children and their parents: A developmental analysis. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (eds), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 89–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-004

Folkestad, G. (2017). Post-national identities in music: Acting in a global intertextual musical arena. In R. Macdonald, D.J. Hargreaves, & Miell, D. (eds), Handbook of musical identities (pp. 122–136). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0007

Gagné, F., & McPherson, G.E. (2016). Analyzing musical prodigiousness using Gagné’s Integrative Model of Talent Development. In G.E. McPherson (ed.), Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology (pp. 3–114). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199685851.003.0001

Gaunt, H., Creech, A., Long, M., & Hallam, S. (2012). Supporting conservatoire students towards professional integration: One-to-one tuition and the potential of mentoring. Music Education Research, 14(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2012.657166

Gembris, H., & Langner, D. (2006). What are instrumentalists doing after graduating from the music academy? In H. Gembris (ed.), Musical development from a lifespan perspective (pp. 141–162). Peter Lang. https://www.peterlang.com/document/1101004

Gronostaj, A., Werner, E., Bochow, E., & Vock, M. (2016). How to learn things at school you don’t already know: Experiences of gifted grade-skippers in Germany. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986215609999

Jarvin, L., & Subotnik, R.F. (2010). Wisdom from conservatory faculty: Insights on success in classical music performance. Roeper Review, 32(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783191003587868

Jett, N., & Rinn, A.N. (2019). Radically early college entrants on radically early college entrance: A heuristic inquiry. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(4), 303–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219874430

Jung, J.Y., & Evans, P. (2016). The career decisions of child musical prodigies. In G.E. McPherson (ed.), Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, music education, musicology and ethnomusicology (pp. 409–423). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199685851.003.0018

Leung, P.P.Y. (2010). Autobiographical timeline: A narrative and life story approach in understanding meaning-making in cancer patients. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 18(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL.18.2.c

Manturzewska, M. (1990). A biographical study of the life-span development of professional musicians. Psychology of Music, 18(2), 112–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735690182002

Martin, A.J. (2016). Musical prodigies and motivation. In G.E. McPherson (ed.), Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology (pp. 320–337). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199685851.003.0013

Mayer, R.E. (2005). The scientific study of giftedness. In R.J. Sternberg & J.E. Davidson (eds), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 437–447). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511610455.025

McLean, K.C. (2005). Late adolescent identity development: Narrative meaning making and memory telling. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.683

McPherson, G.E. (ed.). (2016). Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology. Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/musical-prodigies-9780199685851?cc=rs&lang=en&#

McPherson, G.E., & Lehmann, A.C. (2012). Exceptional musical abilities: Musical prodigies. In G.E. McPherson & G.F. Welch (eds), The Oxford handbook of music education: Vol. 2 (pp. 31–50). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199928019.013.0003_update_001

Mun, R.U., & Hertzog, N.B. (2019). The influence of parental and self-expectations on Asian American women who entered college early. Gifted Child Quarterly, 63(2), 120–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986218823559

Neihart, M. (2007). The socioaffective impact of acceleration and ability grouping: Recommendations for best practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986207306319

Nogaj, A.A., & Bogunović, B. (2015). The development of giftedness within the three-level system of music education in Poland and Serbia: Outcomes at different stages. Journal of the Institute for Educational Research, 47(1), 153–174. https://doiserbia.nb.rs/img/doi/0579-6431/2015/0579-64311501153N.pdf

Palmer, T., & Baker, D. (2021). Classical soloists’ life histories and the music conservatoire. International Journal of Music Education, 39(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761421991154

Plucker, J.A., & Barab, S.A. (2005). The importance of contexts in theories of giftedness: Learning to embrace the messy joys of subjectivity. In R.J. Sternberg & J.E. Davidson (eds), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 201–216). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511610455.013

Rinn, A.N., & Bishop, J. (2015). Gifted adults: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Gifted Child Quarterly, 59(4), 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986215600795

Rogers, K.B. (2007). Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented: A synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986207306324

Sayler, M.F., & Brookshire, W.K. (1993). Social, emotional, and behavioral adjustment of accelerated students, students in gifted classes, and regular students in eighth grade. Gifted Child Quarterly, 37(4), 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698629303700403

Smith, J.A., & Osborn, M. (2004). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In G. M. Breakwell (ed.), Doing social psychology research (pp. 229–254). Blackwell Publishing; British Psychological Society.

Spector-Mersel, G. (2011). Mechanisms of selection in claiming narrative identities: A model for interpreting narratives. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(2), 172–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410393885

Subotnik, R.F., & Jarvin, L. (2005). Beyond expertise: Conceptions of giftedness as great performance. In R.J. Sternberg & J.E. Davidson (eds), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 343–357). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511610455.020

Subotnik, R.F., Jarvin, L., Thomas, A., & Maie Lee, G. (2016). Transitioning musical abilities into expertise and beyond: The role of psychosocial skills in developing prodigious talent. In G.E. McPherson (ed.), Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology (pp. 279–293). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199685851.003.0011

Teague, A., & Smith, G.D. (2015). Portfolio careers and work-life balance among musicians: An initial study into implications for higher music education. British Journal of Music Education, 32(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051715000121

Thomsen, D.K., & Berntsen, D. (2008). The cultural life script and life story chapters contribute to the reminiscence bump. Memory, 16(4), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802010497

Winner, E. (1996). Gifted children: Myths and realities. Basic Books.

Winner, E., & Martino, G. (2000). Giftedness in non-academic domains: The case of the visual arts and music. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Mönks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (eds), International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed., pp. 95–110). Elsevier. https://shop.elsevier.com/books/international-handbook-of-giftedness-and-talent/heller/978-0-08-043796-5

Ziegler, A., Balestrini, D.P., & Stöger, H. (2018). An international view on gifted education: Incorporating the macro-systemic perspective. In S. Pfeiffer (ed.), Handbook of giftedness in children (pp. 15–28). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77004-8_2

Appendix