5. Sound Experience and Imagination at Early School Age: An Opportunity for Unleashing Children’s Creative Potential

©2024 M. Zećo, M. Videnović & L. Silajdžić, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0389.05

Introduction

This study describes a novel approach to facilitating children’s musical development, creativity, and imagination with the use of vibrational percussive instruments in early music education. These musical instruments have been used in therapeutic techniques called sound bath or sound healing (Goldsby et al., 2022; Stanhope & Weinstein, 2020) and as tools for relaxation, meditation, and stress reduction (e.g., Benton, 2008; Crowe & Scovel, 1996; Lee-Harris et al., 2018; Trivedi & Saboo, 2019). We trialled the introduction of these instruments in early musical education to support children’s imagination as a crucial element of creativity (Duffy, 2006; National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education, 1999). The Vernon Howard continuum of imagination (Howard, 1992) was used as an instrument for validating our assumptions and analysing sound experiences triggered by listening and playing these instruments. The pedagogical aims of this approach are to arouse interest in music-related experiences and promote a long-term appreciation of sounds and music.

Music has already been proven as beneficial for various aspects of children’s development, starting from prenatal musical development (Welch, 2014). Early experiences of sound are related to the construction of subjective meanings in the pattern of sound and silence (Welch, 2006). However, loud noises, stress, and the cacophony present in contemporary society may narrow the space for developing this ability (Nadilo, 2013). Children need a supportive environment for their native musical abilities to flourish (Welch, 2014) as well as other cognitive, emotional, and social capacities for music development (Stepanović & Videnović, 2012). Research has shown that, alongside the stimulation of the family environment, early music education can facilitate musical development (Schellenberg, 2015). Moreover, there are non-musical benefits that can be derived from early music education through later development, including improvements to cognitive (Schellenberg, 2004) and socio-emotional skills (Stepanović et al., 2019; Stepanović Ilić et al., in press; see Chapter 6 in this volume) as well as to linguistic (Degé & Schwarzer, 2011; Gromko, 2005) and visuospatial abilities (Rauscher & Zupan, 2000).

While there have been some attempts to introduce the sound of vibrational instruments into education, the focus has been on vulnerable children. Peter Hess (2008) in his pedagogical work aimed to give young people with behaviour disorders equal opportunities for education and an individualised approach to support their development. During his journey to Nepal, Hess was inspired to conceptualise the use of sound as a medium for relaxation and a mechanism to release different blockages in the body, in therapeutic as well as educational settings.

Designing successful early music education for all children (not only for gifted ones) that would broaden their experiences in creative activities related to music and contribute to their early musical development is a challenging task. A sharp focus on the formal curriculum has led to limitations in creative engagement with music, which could be overcome by an informal music education that enhances new ideas and extends experiences (Georgii-Hemming & Westvall, 2010). Some think that returning to sound and the production of sound as the beginning of music experiences could be an appropriate starting point (e.g., Schiavio et al., 2017).

In this applied interdisciplinary study, we traced the sound experiences of a group of six-year-olds during specifically created musical activities. We expected the selected vibrational instruments to be a means whereby children’s imaginative processes could be enhanced. We assimilated musical activities into the daily school schedule and researched how much and in what way holistic sound can stimulate a creative and positive social and musical environment.

Musical vibrational instruments and early education

We have argued that every child should benefit from early musical education, regardless of their talent, background, musical knowledge, or interest. It is well documented that children intuitively discover different qualities of sound, timbres, melodic and rhythmic patterns before starting their formal musical education (Blacking, 1974; Tafuri, 1995), and that these sound-oriented musical actions appear in infancy (Schiavio et al., 2017). Children are generally able to describe sounds verbally, and to anticipate and describe changes in music and differences between musical genres by the end of the preschool period (Burke, 2018; Stepanović & Videnović, 2012;). However, a child needs support to develop these skills, as well as the ability to listen attentively. Teaching music in preschool by ear, or ‘aural learning’, is an important mode of learning at various levels of music education (Bačlija Sušić et al., 2019; Zećo et al., 2023).

Children can learn musical conventions and structures through environmental exposure to music (Tafuri et al., 2003). Children spontaneously differentiate sound qualities during free imaginative play, where there are no strict rules and they are not foreseeing what they still ‘do not know’. In this way, children sensitise themselves and develop listening skills as preconditions for music education.

Vibrational musical instruments could be a powerful didactic tool in early childhood education for several reasons. The soft, resonant, and subtle sound of these instruments prompts one to listen to their qualities in a quiet manner. This is particularly important because growing up in noisy, stressful environments interferes with a child’s language development (White-Schwoch et al., 2015), increases the risk of academic failure (Kraus et al., 2014), and can reduce the quality of life (Klatte et al., 2017). Raising children’s awareness of sounds provides a basis for enjoying music (Swanwick & Tillman, 1986). It is also a way to increase children’s sensitivity to the sound coming from the environment (Zhou, 2015) and their more general phonological awareness (Degé & Schwarzer, 2011). We furthermore expect that exposure to different, interesting sounds will trigger the process of imagination as an inevitable part of a child’s play.

The beginning of formal education can be a very stressful and demanding period for some children in the areas of communication, language acquisition, and social adjustment (Crowe & Scovel, 1996; Videnović et al., 2018). However, listening to vibrational instruments can have a relaxation effect and potentially reduce anxiety and stress (Goldsby et al., 2022; Stanhope & Weinstein, 2020). One of the advantages of these instruments is that it is relatively easy for children to produce a rich and harmonious sound that is novel to them, different from other sounds or instruments, and they can then improvise and produce their own music. Children can very quickly become involved in music-making regardless of their previous knowledge and musical affinity. Research data has shown that children often find playing vibrational instruments more attractive than any other music-related activity (Temmerman, 2000). Hence, playing such instruments in class can enhance students’ motivation to engage in musical activities during early music education. Moreover, when children play in a group, they also learn to collaborate in the process of creating meaning through sound. This kind of engagement contributes to their social and collaborative skills development, which is an important objective of education in general (Baucal et al., 2023).

Imagination and improvisation to foster musical creativity

Cognitive processes of improvisation and imagination have a role even in the early years in promoting the development of musical creativity, as was shown in a school context in Croatia (Bašić, 1973) and confirmed in later music research (Koutsoupidou & Hargreaves, 2009). Improvisation implies the simultaneous making and performing of music without much previous preparation (Campbell, 2009; Young, 2002, 2008). Playing with sounds by improvising or exploring could be considered something that any child can do and that should be supported as part of music education (Hickey, 2009). It is expected that six-year-olds are able to make the first steps towards playing musical instruments and devising rhythmical patterns (Burke, 2018). Research shows that creating opportunities for improvising significantly affects the development of musical creative thinking, by promoting musical flexibility, originality, and syntax in children’s music-making (Koutsoupidou, 2008). Improvisation in a group as a medium for non-verbal dialogue can support social development and communication skills (MacDonald et al., 2002; Major & Cottle, 2010) and foster emotional expression (Duffy, 2006).

The idea that early music education needs a different approach is pretty old. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze noticed that by teaching children to play and sing, we avoid teaching them to hear and listen (Jaques-Dalcroze, 1932). He designed a well-known approach to music education that aims to support students’ innate musicality by introducing rhythmic movement (often called eurhythmics), improvisation and spontaneous expression (Anderson, 2012; Jaques-Dalcroze, 1930). His idea was that music education should encourage the expression of the somatic experience of rhymes before introducing intellectual explanation. The tension in contemporary music education also lies between teaching children musical skills, techniques, and rules, while at the same time leaving space for spontaneous music-making. Playing vibrational instruments does not require a particular mastering of skills for it to be sonically rewarding. It could be a useful didactic tool for encouraging a child’s creative growth through spontaneous improvisation.

Spontaneous improvisation can include various artistic areas where the child can express their story through sound and art, and the use of motor skills (Bašić, 1985), including body movements (Burnard, 1999). When children are given the opportunity to choose an instrument for improvisation, they will often select percussion instruments that allow unrestricted body-use, with no need for precise instrumental technique during playing.

A child’s imagination and fantasies may support spontaneous music-making in response to sounds, which are considered crucial spontaneous aspects of musical experience (Reichling, 1997). Imagination bridges children’s play and musical engagement. Imagination has also been the focus of contemporary arts education as the source of creative expression (e.g., Sungurtekin & Kartal, 2020; Wagner, 2014). Imagination emerges early in childhood development, first in pretend play and later in role play (Harris, 2000). A child’s fantasy life is not something trivial or useless. It is a valuable resource for a child’s cognitive and socio-emotional development (e.g., Kushnir, 2022). Connecting music with the world of fantasy at an early age may increase the likelihood that a child will later engage in music as an extracurricular activity or hobby. Furthermore, engaging in music in their free time has a multitude of positive effects on students’ development (Videnović et al., 2010). Research shows that formal music education in primary school often does not adequately support children’s musical creativity and imagination (Sungurtekin, 2021). Formal educational activities are often perceived as mentally demanding, tedious, and boring, frequently provoking anxiety (Pešić et al., 2013; Radišić et al., 2015). The importance of imagination was recognised in Lev Vygotsky’s theoretical writings a long time ago. He argued that education should be oriented towards developing children’s imaginative abilities (Vygotsky, 1967/2004). Imagination was treated as a basis for all creative activities. Children’s experience of music is in many ways different from that of adults or professional musicians (Gardner, 1982).

Howard proposed a way to trace a child’s imagination in relation to music (Sungurtekin, 2021). He constructed a scale labelled ‘continuum of imagination’, which is rarely used, but in our opinion the only available method that considers specific qualitative differences in the child’s responses to sounds. The Howard continuum of imagination has four points: ‘Beginning with fantasy, imagining the non-existent, imagining what exists but is not present, having an image and imposing it on something, imagining X as Y and ending with perceiving things in general and recognising them’ (summarised by Reichling, 1997, p. 43). These points do not imply a particular age or stage of development but are considered milestones in the continuum. The further the child’s imagination progresses along the continuum, the greater is their ability to recognise and include concrete sonic characteristics in the imagination process. Reichling (1997) chose this scale to investigate the role of imagination in play and music and to develop a framework for music grounded in play theory. The first point is named fantasy or imagining the non-existent. This kind of imagination is the most similar to children’s play, when substitutes for the perceivable world are created (e.g., monsters, fairy tales, heroes). At the second point—imagining what exists but is not present—things that are part of the imagination exist in the real world, but they are not part of the child’s current situation (Reichling, 1997). The third point describes ‘figurative imagination’—imagining X as Y—when a metaphoric relationship between present and imagined is created (Reichling, 1997). The final point, labelled ‘literal imagination’, includes perceiving things in general and recognising them. This type of imagination is thoroughly grounded in the sense-world. It includes improvisation with sound elements to construct a new musical performance combination. A child should be able to recognise and preserve sound elements like volume, intensity, harmony, and the colour of the sound.

Aims

Following on from this theoretical background, this empirical study had two related aims. The main aim was to create a series of workshops with intensive musical activities, demonstrations, and active participation, working with selected vibrational instruments in the first year of primary school. The second aim was to investigate students’ imaginative processes instigated by listening to and playing vibrational instruments. We assumed that the opportunity for spontaneous improvisation with these instruments would foster a sensitivity to sound qualities.

Method

Participants

Four groups of students attending the first year of primary school, aged 6 to 7, participated in the sound workshops. There were 15 children in each group, 34 boys and 26 girls, totalling 60 children. The workshop leader (WL) was the first author, a music teacher with experience and expertise working with young children. A technical assistant (TA) was involved in supporting the workshops. The research was carried out in a primary school in the Canton of Sarajevo in the academic year 2016/17, with extensive support and collaboration from the headmaster, school counsellors, teachers, and parents. Parents were informed about the content of the workshops and gave informed consent for their children’s participation in workshops and research.

Materials

Three types of vibrational instruments were used in all the workshops: gongs, Himalayan Singing Bowls, and Koshi Chimes. All instruments were of East Asian origin. In the workshops, we used the Planetary gong Venus, similar to the Symphonic gong (Cousto, 2015). The gong is about 66 cm high, and it produces a rich, warm bass tone, with a frequency of 221.23 Hz. Children played it while they were on their knees, with the gong placed in front of them (on the right in Figure 5.1).

Fig. 5.1 Photograph of the workshop setting. The faces of the participants are blurred to preserve their privacy. Photo from Mirsada Zećo’s private collection

Himalayan Singing Bowls, or small gongs, also have a long-standing tradition (Perry, 2016). Three different bowls were used (Figure 5.1, in the middle) that are often part of sound therapies (Hess, 2008). The small bowl weighs about 600 grams and has a high sound (200–1,200 Hz). The medium bowl weighs about 900 grams and has a wide sound spectrum (100–1,000 Hz). The large sonic bowl weighs 1,500 grams and produces a deep sound (100–2,800 Hz). Therefore, each bowl emanates numerous sounds and aliquots depending on the place where it is touched. A special wooden or leather-coated stick (puja) was used to produce the sound waves by rubbing the instrument. Chimes are also used in classical music as percussion instruments (Pesek & Bratina, 2016). The Koshi Chimes that were used have a specific sound and contain eight tones in a resonant bamboo tube (held by the children at the left of Figure 5.1).

Procedure

A series of twelve workshop sessions with different content was realised over a period of four months. The workshops were held once a week, lasting forty minutes each. Workshops were scheduled during Music Culture lessons, which is an obligatory subject in general primary school and hence all the children in the class were present. The schedule was adapted according to the children’s school timetable and other curricular activities. The developmental characteristics of the age group, such as attention span and the ability to concentrate, including individual differences in abilities and knowledge, were considered when planning the workshop session activities. A technical assistant recorded videos and wrote down children’s verbal responses and observations of children’s behaviour in the pre-prepared protocols. After each workshop, the workshop leader and assistant collated their observations about the children’s behaviours.

Guided fantasy was used to enhance the imaginative process in these workshops. A regular part of some workshops was a fantasy trip with vibrational instruments as the background sound, providing a relaxed and non-threatening environment as a solid ground for creative processes (Anderson, 1980). Children lay on the floor with their eyes closed during guided fantasy, listening to sounds and building up the fantasy stories related to them. In this way the atmosphere, pleasure, state of mind, and mood was created. The leader/researcher delivered spontaneous sound improvisations along with a story. The stories that were intended to inspire fantasy were about natural elements, such as the symbols associated with the vibrational instruments. Children were guided to travel ‘through the sky’ and listen to the story about a ‘water drop’, or else an ‘imaginary doll’ took them on a trip to the land of dreams and play. A brief description of the workshops’ content is presented in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Content of the workshops

Children at this age cannot accurately express their sound experience solely through words (Lefevre, 2004). With that in mind, children were encouraged to reflect on their sound experience (Workshops 1–5) using different symbolic systems (drawing, movement, or dance). Children were encouraged in the early sessions to fantasise about the sounds, but they did not play the instruments or improvise. For example, having been assigned into groups, children were asked to draw their impressions after different musical activities. Also, they were encouraged to verbally describe the colour of the instruments or to use movement to express their imagination. This method is in line with recent empirical research showing that sensory systems (e.g., touch, smell, the auditory system) interact, producing multimodal or cross-modal experiences (Eitan & Granot, 2006).

In the next set of workshops, children had the opportunity to produce or act out sounds, followed by playing the instruments, in addition to listening and guided fantasy. Namely, children were encouraged to imitate the instruments’ sounds with their voices or movements like in the first set, and then they played instruments and improvised with them (Workshops 6–12). The gong’s position was lowered to the children’s height so they could play more easily, and it was suggested that they ‘do not play too hard because the hidden heart is in the instrument’s middle’.

The additional thirteenth workshop took place without instruments, and the aim of the session was evaluation; specifically, we were interested to hear children’s impressions about the whole process. The workshop leader told the children the instruments had returned to their homeland. Children were invited to share their experiences about the activities or the instrument they enjoyed the most or to tell the story about the homeland of the instruments. A brief questionnaire (four multiple-choice questions and the opportunity to add additional insights) was created to assess parents’ perspectives on the workshops (e.g., did the children talk about the workshops, participate in them, describe instruments, or imitate instruments at home). Also, two teachers described their impressions of the workshops and their impact on the children’s behaviour.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis was conducted using the transcriptions of children’s verbal reactions from the video recordings. Children’s responses during the discussion phase of the workshops, their guided fantasy stories, and spontaneous comments produced during activities (Table 5.1) were included as material for analysis. We used Thematic Analyses (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and combined deductive and inductive methods. Two authors read each child’s verbal response, analysing, in particular, their relationship with Howard’s four-point classification. Less than 10% of the answers remained unclassified.

Statements were coded by hand on one of the four points of the continuum. Two authors independently coded the transcripts. The statements were mixed up so that the coder could not see in which workshops they had appeared. The differences between codes (less than 10%) were discussed in detail. In case of disagreement, final codes were created collaboratively. We paid particular attention to statements that appeared in the process of the workshops related to whether the children’s imagination was stimulated through guided fantasy (Workshops 1–5), and to responses after instruments were introduced and played in the workshop (Workshops 6–12).

Results

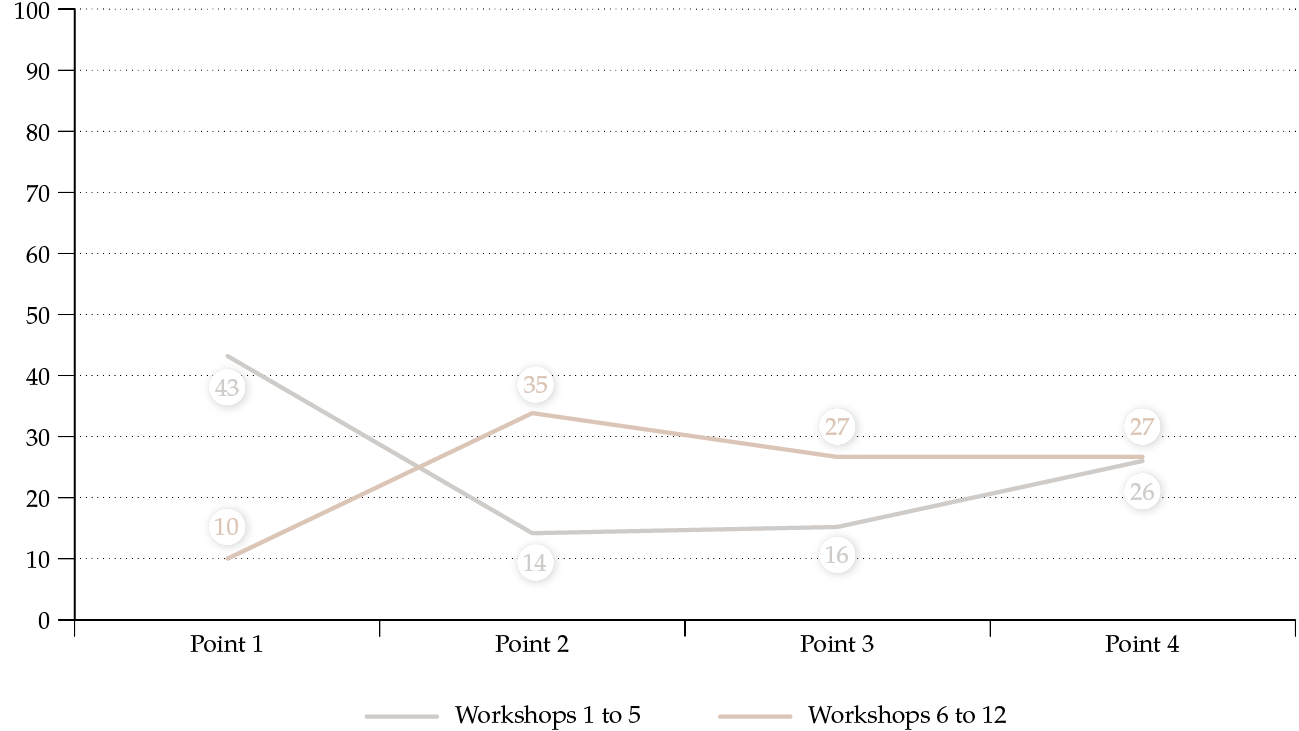

Figure 5.2 shows the percentage of responses children gave that were classified to be at a certain point of Howard’s continuum across the two workshop phases. Responses to the first five workshops were considered as one phase or group, namely, fantasies induced by the WL’s storytelling and playing the instruments. Workshops where the practice of playing and improvisation was introduced (6–12), constituted the second group of responses. We analysed 131 responses in total: 69 were produced during the first five workshops, and the remaining 62 were from the second group of workshops. The results showed that children’s imagination reached each point of the Howard continuum of imagination.

Note. Imagining the non-existing (Point 1), Imagining what exists but is not present (Point 2), Figurative imagination (Point 3), Literal imagination (Point 4).

Fig. 5.2 Percentage of the responses at each point of the Howard continuum of imagination

The biggest difference between the two phases (groups) is in terms of Point 1 of the continuum. At the beginning, the children’s imaginative processes were oriented towards the non-existing world when they were exposed to listening to improvisation and guided fantasy. They described the visions they created in their minds as: ‘Clouds [that] whisper a secret or a story or take you to the dragon castle’. Sometimes they were emotionally involved: ‘A ghost came to our classroom, and I was very scared.’ To attribute life to inanimate objects (like clouds) is a well-known characteristic of this developmental stage (e.g., Klingensmith, 1953; Piaget, 1926). It was expected to occur during guided fantasy.

The fantasies sometimes took the form of quite a complex story. For example, a child created a fairy tale about the instruments’ homeland during the last workshop:

Once upon a time there were three instruments, one was big and called a gong, and the other was small, and it was called a bowl. And then they walked until they saw the house and went inside. And the gong says, ‘Is this your house or are we going round?’ The small bowl says, ‘We’re just playing!’, And the gong says, ‘We’re not playing after all.’ Then something black came, they didn’t know what it was, but it was a stick called ‘little black’. When they met that stick, they joined it and followed it. The stick took them to a dark place. When they came into the scary, big house, they met a great spirit and the spirit fulfilled their three wishes to play loud or a little quieter. When they told them what their wishes were, they went on a picnic. The story is over!

The second kind of fantasy with real-life elements was the dominant one in the second group of workshops. Children were ‘travelling to Africa, Japan, Paris’, or they included their relatives, parents, or friends in their imagination (‘My aunt and I walked into the park’; ‘I saw a stork and a chicken—a very small stork’; ‘My parents were drinking tea, while I was playing’).

Figurative imagination (Reihling, 1997) included metaphors to describe sounds. The percentage of these statements increased in the second group of workshops. Our results show that children construct verbal metaphors spontaneously when they try to express their sound experiences. Improvisation tasks seemed to support this process. They compared the sound of the therapeutic instrument with another sound in nature or their environment. For example, ‘The sound is like the heart’, or ‘It is the sound of an elephant movement’, or ‘The sound of an insect or laser’.

At the final point of the Howard continuum of imagination, the students were able to describe sound characteristics: intensity, volume, rhythm, and harmony. They showed their sensitivity by comparing sounds; for example, ‘a better sound than the gong instrument, softer sound’ (Literal imagination). Students used their sound experience as a tool to describe something beyond music and the world of sound (‘The sound of Earth will be like this’). They also made a connection between different sensory systems. The sound was ascribed a colour, smell, and tactile characteristics: the sound is ‘cold’, ‘sweet’, ‘heavy’, ‘soft’. These statements occurred from the first to the last workshop. It is important to notice that the children were not selected based on their musical talent. This shows that children’s ability to listen and fantasise based on sounds is better than is often assumed. Introducing vibrational instruments into their education would be one way to stimulate the further development of their imaginative capacities. Table 5.2 presents examples of children’s comments from each point.

Table 5.2 Examples of the children’s answers

|

Imagining the non-existing |

Imagining what exists but is not present |

||

|

The cloud was singing TU, TU, TU. I saw a white cloud and hung out with it. I was flying. I was dreaming high. I went to Mount Jupiter. |

It’s a volcano! …. I am an Indian and I light a fire… the fire crackles … We are the ‘Flowering Tribe’ and we are invisible in the forest … we are very quiet, we listen to the wind. I went to Dubrovnik. |

The sound is like ice. The bowl has a heart beating in the wood!!! The sound of a bee. The sound is a stampede of elephants. The sound of surprise. |

The sound of the biggest bowl is the deepest! It has both a medium sound and a high sound. I felt a sound, a heavy sound, a deep sound. |

During the workshops, we took care not to leave any children behind and to include them all in the designed activities. All children had an equal opportunity to participate according to their wishes at the time. Our impression was that children accepted the activities, easily developed their imagination, and were happy to participate. The last workshop was dedicated to the children’s evaluation of their experience with this type of work. They had the opportunity to talk about the workshops while drawing with watercolours. For example, a child drew a house for the instruments while saying: ‘Their house is somewhere in the air since the instruments go somewhere up there when we play the notes!’ They were very enthusiastic about enrolling again on the workshop.

Besides investigating the children’s experiences, we also asked parents and teachers to share their impressions with us. Our results show that children shared with their parents their experiences relating to the workshops. Most parents (71%) described instruments and their sounds correctly. Only two parents (out of 42) did not talk with their children about the workshops’ activities. Almost all the parents (91% present) reported that their children gladly participated in the workshops’ activities. Teachers also described the positive effects of the workshops. They reported that the children looked forward to each workshop with great impatience. They would return to the classroom full of impressions, happy and ready to talk about everything they heard, saw, and learned. As one teacher said: ‘After the workshops, they would return to the classroom relaxed, rested, and full of energy for the next wave of teaching.’

Discussion

Research in music pedagogy emphasises the importance of a child’s spontaneous improvisation and imagination during musical education (Clennon, 2009; Goncy & Waehler, 2006; Hickey, 2009). Music is a powerful medium for invoking these processes (Ritter & Ferguson, 2017). However, educators experience difficulties implementing and developing activities that are dedicated to these goals. Traditional teaching in the form of ‘learning to sing children’s songs’ has not fostered enough of children’s inner creative competencies (Anderson, 2012; Georgii-Hemming & Westvall, 2010). In light of its interdisciplinary and innovative approach to early music education, this study intended to draw attention to underused possibilities relevant to facilitating children’s creativity.

The study represents a unique attempt to enhance children’s spontaneity, imagination, curiosity, and openness towards new ideas by implementing unconventional vibrational music instruments into music classes. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, in his pioneer works, used classical musical instruments to foster improvisation with sounds through spontaneous movement (Jaques-Dalcroze, 1930). The sound colour and tone qualities of vibrational musical instruments differ from classical ones, producing uncommon aesthetic experiences. The results suggest that the deliberately planned workshops acted as catalysts for the children’s imaginative processes, with these fantasies gradually evolving in their properties, adopting forms of figurative or literal imagination over time. The children were sometimes able to describe sound characteristics and use them to guide their imagination (Howard, 1992). Furthermore, the children expressed sensitivities to sound qualities, particularly in later workshops when playing the instruments was introduced. However, differences between the two sets of workshops do not imply that certain activities, like playing, will better foster sound sensitivity and imagination. This study’s methodology only suggests that designed workshops will eventually provoke figurative imagination and sophisticated perception of sound quality among preschool students.

The study results are in line with previous research indicating the significance of children’s improvisatory music-making, which can be a tool for fostering creative processes (Koutsoupidou & Hargreaves, 2009) and cognitive development (Duffy, 2006; Pešić & Videnović, 2017). Furthermore, giving children the chance to use imagination and play freely may make them better listeners. In our research, we developed a method to scaffold improvisatory play with musical instruments. This was facilitated by emphasising imaginative ideas evoked by sounds, and modelling improvisatory play to support imagery provided by the workshop leader before inviting children to have a go. The emphasis on sounds and their qualities may have offered a safe environment for play and improvisation.

The practical implication suggests that an effort should be made to introduce listening to simple sounds before singing or instrument learning in early music education. Challenging children to express their experiences will foster their ability to pay attention to and identify sound qualities. Guided fantasy and other art forms (like drawing) can be powerful tools for enhancing the imagination. The important point is that the workshop participants were not selected based on their musical talents or prior knowledge. Indeed, we believe that musical pedagogy should start from the notion that every child could be creative in music (Goncy & Waehler, 2006; National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education, 1999), rather than musical education being reserved for talented children only. However, organising education following this principle is still a challenge. We argue that this important pilot study on the introduction of vibration instruments into general education could be the way to unlock every child’s creative potential.

Limitations of the study

This research design could not separate the effects of workshop activities (including, e.g., guided fantasy) from the effects of being more familiar with the sound of the instruments. It is possible that a change in the type of imagination during the workshop might be related to children becoming more familiar and relaxed in the new activity, and should not be exclusively attributed to the workshop activities. It is important to keep in mind that no control group or elimination of confounding factors were used, which limits the inference about the effects of the pedagogical intervention. Furthermore, we did not formally assess the skill development outcomes of the workshops. Our observations do point to the inclusivity of the methods and the qualitative benefits that the children reported.

Conclusion

As a result of our research, we can state that vibrational musical instruments can play an important role in music education classes, in the early years and possibly beyond. They can be included successfully in combination with guided fantasy, drawing, dancing, and improvisation activities. The benefits are directed towards increasing children’s sound sensitivity and making them better music listeners, which was facilitated by the fact that children did not have prior expectations of how these instruments sound. Moreover, it was easy for them to play the instruments and make rich sounds. In that way, every child had an equal opportunity to be a musician regardless of their abilities and previous knowledge. This represents a good start for further implementations made for developing musical skills in general education without excluding anyone.

We are aware that this practice can sometimes be a challenge to incorporate into existing research paradigms and music education. These activities require significant resources. However, this action research was essential for gaining new insights into the opportunities to make music in childhood in a new setting. Clearly, teachers are the gatekeepers and can have a powerful influence on access to music: ‘From a Vygotskian sociocultural perspective, it is clear that children’s development is shaped and guided by “more competent others”’ (Lamont, 2017, p. 180). The implementation of workshops with unconventional sound instruments and related practice in regular schools can serve as an incentive for adopting this flexible model. Such instruments have a place in enhancing the imagination, aural skills, and cognitive development. The practice of ‘playing with music’ opens new ways of understanding music and building up ‘music in identity’ (Hargreaves et al., 2012). This trial opens the possibility of applying theory and practice from the music therapy domain to the future work of music educators. It presents a challenge and a contribution for further use and exploration.

References

Anderson, R.F. (1980). Using guided fantasy with children. Elementary School Guidance and Counseling, 15(1), 39–47.

Anderson, W.T. (2012). The Dalcroze approach to music education: Theory and applications. General Music Today, 26(1), 27–33. https://doi. 10.1177/1048371311428979

Bačlija Sušić, B., Habe, K., & Mirošević, J.K. (2019). The role of improvisation in higher music education. In L. Gómez Chova, A. López Martínez, & I. Candel Torres (eds), ICERI2019 12th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain: Conference Proceedings (pp. 4473–4482). IATED Academy. https://library.iated.org/view/BACLIJASUSIC2019ROL

Bašić, E. (1973). Improvizacija kao kreativni čin [Improvisation as an act of creativity]. Umjetnost i dijete, 26(5), 44–69.

Bašić, E. (1985). Sinkretizam u muzikalnom izražavanju djeteta [Syncretism in children’s musical expression]. Umjetnost i dijete, 17(1), 21–33.

Baucal, A., Jošić, S., Stepanović Ilić, I., Videnović, M., Ivanović, J., & Krstić, K. (2023). What makes peer collaborative problem solving productive or unproductive: A qualitative systematic review. Educational Research Review, 100567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100567

Benton, M. (2008). Gong yoga: Healing and enlightenment through sound. Bookshelf Press.

Blacking, J. (1974). How musical is man? University of Washington Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burke, N. (2018). Musical development matters in the early years. The British Association for Early Childhood Education. https://early-education.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Musical-Development-Matters-ONLINE.pdf

Burnard, P. (1999). Bodily intention in children’s improvisation and composition. Psychology of Music, 27(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735699272007

Campbell, P.S. (2009). Learning to improvise music, improvising to learn music. In G. Solis, & B. Nettl (eds), Musical improvisation: Art, education, and society (pp. 119–142). University of Illinois Press.

Clennon, O.D. (2009). Facilitating musical composition as ‘contract learning’ in the classroom: The development and application of a teaching resource for primary school teachers in the UK. International Journal of Music Education, 27(4), 300–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761409344373

Cousto, H. (2015). The cosmic octave: Origin of harmony. Mendocino, California, EUA: LifeRhythm.

Crowe, B.J., & Scovel, M. (1996). An overview of sound healing practices: Implications for the profession of music therapy. Music Therapy Perspectives, 14(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/14.1.21

Degé, F., & Schwarzer, G. (2011). The effect of a music program on phonological awareness in preschoolers. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, Article 124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00124

Duffy, B. (2006). Supporting creativity and imagination in the early years (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

Eitan, Z., & Granot, R.Y. (2006). How music moves: Musical parameters and listeners’ images of motion. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23(3), 221–248. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2006.23.3.221

Jaques-Dalcroze, E. (1930). Eurhythmics and its implications (F. Rothwell, Trans.). The Musical Quarterly, 16, 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/XVI.3.358

Jaques-Dalcroze, E. (1932). Rhythmics and pianoforte improvisation (F. Rothwell, Trans.). Music and Letters, 13, 371–380.

Gardner, H. (1982). Art, mind, and brain: A cognitive approach to creativity. Basic Books.

Georgii-Hemming, E., & Westvall, M. (2010). Music education—a personal matter? Examining the current discourses of music education in Sweden. British Journal of Music Education, 27(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051709990179

Goldsby, T.L., Goldsby, M.E., McWalters, M., & Mills, P.J. (2022). Sound healing: Mood, emotional, and spiritual well-being interrelationships. Religions, 13(2), Article 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020123

Goncy, E.A., & Waehler, C.A. (2006). An empirical investigation of creativity and musical experience. Psychology of Music, 34(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0305735606064839

Gromko, J.E. (2005). The effect of music instruction on phonemic awareness in beginning readers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 53(3), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242940505300302

Hargreaves, D. J., Hargreaves, J. J., & North, A. C. (2012). Imagination and creativity in music listening. In D. Hargreaves, D. Miell, & R. Macdonald (eds), Musical imaginations: Multidisciplinary perspectives on creativity, performance and perception. Oxford University Press.

Harris, P.L. (2000). The work of the imagination. Blackwell Publishing.

Hess, P. (2008). Singing bowls for health and inner harmony through sound massage according to Peter Hess. Tension reduction, creativity enhancement, history, rituals. (T. Hunter, Trans). (Original work published 1999). Verlag Peter Hess.

Hickey, M. (2009). Can improvisation be ‘taught’?: A call for free improvisation in our schools. International Journal of Music Education, 27(4), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761409345442

Howard, V.A. (1992). Learning by all means: Lessons from the arts. Peter Lang.

Klatte, M., Spilski, J., Mayerl, J., Möhler, U., Lachmann, T., & Bergström, K. (2017). Effects of aircraft noise on reading and quality of life in primary school children in Germany: Results from the NORAH study. Environment and Behavior, 49(4), 390–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516642580

Klingensmith, S.W. (1953). Child animism: What the child means by ‘alive’. Child Development, 24, 51–61.

Koutsoupidou, T. (2008). Effects of different teaching styles on the development of musical creativity: Insights from interviews with music specialists. Musicae Scientiae, 12(2), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/102986490801200207

Koutsoupidou, T., & Hargreaves, D.J. (2009). An experimental study of the effects of improvisation on the development of children’s creative thinking in music. Psychology of Music, 37(3), 251–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735608097246

Kraus, N., Hornickel, J., Strait, D.L., Slater, J., & Thompson, E. (2014). Engagement in community music classes sparks neuroplasticity and language development in children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01403

Kushnir, T. (2022). Imagination and social cognition in childhood. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 13(4), Article e1603. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1603

Lamont, A. (2017). Musical identity, interest, and involvement. In R. McDonald, D.J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (eds), Handbook of musical identities (pp. 176–196). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0010

Lee-Harris, G., Timmers, R., Humberstone, N., & Blackburn, D. (2018). Music for relaxation: A comparison across two age groups. Journal of Music Therapy, 55(4), 439–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thy016

Lefevre, M. (2004). Playing with sound: The therapeutic use of music in direct work with children. Child & Family Social Work, 9(4), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2004.00338.x

MacDonald, R.A.R., Miell, D., & Mitchell, L. (2002). An investigation of children’s musical collaborations: The effect of friendship and age. Psychology of Music, 30(2), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735602302002

Major, A.E., & Cottle, M. (2010). Learning and teaching through talk: Music composing in the classroom with children aged six to seven years. British Journal of Music Education, 27(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051710000240

Nadilo, B. (2013). Definiranje i zakonsko određivanje buke: Mnogo nepreciznosti i nejasnoća [Definitions and legal determination of noise: A lot of vagueness and ambiguity]. Građevinar, 64(9), 857–863. http://casopis-gradjevinar.hr/assets/Uploads/JCE_65_2013_9_8_Zastita-oklisa.pdf

National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (1999). All our futures: Creativity, culture and education. DfEE Publications. https://sirkenrobinson.com/pdf/allourfutures.pdf

Perry, F. (2016). Himalayan sound revelations: The complete Singing bowl book. Polair Publishing.

Pesek, A., & Bratina, T. (2016). Gong and its therapeutic meaning. Muzikološki zbornik/ Musicological Annual, 52(2), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.4312/mz.52.2.137-161

Pešić, J., & Videnović, M. (2017). Slobodno vreme iz perspective mladih: kvalitativna analiza vremenskog dnevnika srednjoškolaca [Leisure from the youth perspective: A qualitative analysis of high school students’ time diary]. Zbornik Instituta za pedagoška istrazivanja, 49(2), 314–330. https://doi.org/10.2298/ZIPI1702314P

Pešić, J., Videnović, M., & Plut, D. (2013). How high-schoolers perceive educational activities: A qualitative analysis of time recordings. Nastava i vaspitanje, 62(3), 407–420. https://scindeks.ceon.rs/article.aspx?artid=0547-33301303407P

Piaget, J. (1926). La représentation du monde chez l’enfant [The child conception of the world]. Félix Alcan.

Radišić, J., Videnović, M., & Baucal, A. (2015). Math anxiety—contributing school and individual level factors. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0224-7

Rauscher, F.H., & Zupan, M.A. (2000). Classroom keyboard instructions improve kindergarten children’s spatial-temporal performance: A field experiment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00050-8

Reichling, M.J. (1997). Music, imagination, and play. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 31(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333470

Ritter, S.M., & Ferguson, S. (2017). Happy creativity: Listening to happy music facilitates divergent thinking. PloS ONE, 12(9), Article e0182210. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182210

Schellenberg, E.G. (2004). Music lessons enhance IQ. Psychological Science, 15(8), 511–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00711.x

Schellenberg, E.G. (2015). Music and nonmusical abilities. In G. McPherson (ed.), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development (2nd ed., pp. 149–176). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198744443.003.0008

Schiavio, A., van der Schyff, D., Kruse-Weber, S., & Timmers, R. (2017). When the sound becomes the goal: 4E cognition and teleomusicality in early infancy. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 1585. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01585

Stanhope, J., & Weinstein, P. (2020). The human health effects of singing bowls: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 51, Article 102412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102412

Stepanović Ilić, I., Krnjaić, Z., Videnović, M. & Krstić, K. (in press). How do adolescents engage with music in spare time? Leisure patterns and their relation with socio-demographic characteristics, wellbeing and risk behaviours. Psychology of Music.

Stepanović, I., & Videnović, M. (2012). Intelektualni (saznajni) razvoj [Intelectual (cognitive) development]. In A. Baucal (ed.), Standardi za razvoj i učenje dece ranih uzrasta u Srbiji [Standards for the development and learning of early-age children in Serbia] (pp. 23–39). Filozofski fakultet.

Stepanović Ilić, I., Videnović, M., & Petrović, N. (2019). Leisure patterns and values in adolescents from Serbia born in 1990s: An attempt at building a bridge between the two domains. Serbian Political Thought, 66, 99–123. https://doi.org/10.22182/spm.6642019.5

Sungurtekin, S. (2021). Classroom and music teachers’ perceptions about the development of imagination and creativity in primary music education. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(3), 164–186. http://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2021371364

Sungurtekin, S., & Kartal, H. (2020). Listening to colourful voices: How do children imagine their music lessons in school? International Online Journal of Primary Education, 9(1), 73–84. https://www.iojpe.org/index.php/iojpe/article/view/40

Swanwick, K., & Tillman, J. (1986). The sequence of musical development: A study of children’s composition. British Journal of Music Education, 3(3), 305–339. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051700000814

Tafuri, J. (1995). L’educazione musicale: Teorie, metodi, pratiche [Music education. Theories, methods, practices] (Vol. 1). EDT srl.

Tafuri, J., Baldi, G., & Caterina, R. (2003). Beginnings and endings in the musical improvisations of children aged 7 to 10 years. Musicae Scientiae, 7(1), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649040070S108

Temmerman, N. (2000). An investigation of the music activity preferences of pre-school children. British Journal of Music Education, 17(1), 51–60. https://ro.uow.edu.au/edupapers/6

Trivedi, G.Y., & Saboo, B. (2019). A comparative study of the impact of Himalayan singing bowls and supine silence on stress index and heart rate variability. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Mental Health, 2(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.14302/issn.2474-9273.jbtm-19-3027

Videnović, M., Pešić, J., & Plut, D. (2010). Young people’s leisure time: Gender differences. Psihologija, 43(2), 199–214. https://doiserbia.nb.rs/img/doi/0048-5705/2010/0048-57051002199V.pdf

Videnović, M., Stepanović Ilić, I., & Krnjaić, Z. (2018). Dropping out: What are schools doing to prevent it? Serbian Political Thought, 17(1), 61–77. https://www.ips.ac.rs/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/spt17_12018-4.pdf

Vygotsky, L.S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood (M.E. Sharpe, Trans.). Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10610405.2004.11059210 (Original work published 1967)

Wagner, T. (2014). The global achievement gap: Why our kids don’t have the skills they need for college, careers, and citizenship—and what we can do about it. Hachette UK.

Welch, G.F. (2006). Singing and vocal development. In G. McPherson (ed.), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development (pp. 311–330). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198530329.003.0016

Welch, G.F. (2014). The musical development and education of young children. In B. Spodek & O.N. Saracho (eds), Handbook of research on the education of young children (pp. 269–286). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315045511

White-Schwoch, T., Davies, E.C., Thompson, E.C., Carr, K.W., Nicol, T., Bradlow, A.R., & Kraus, N. (2015). Auditory-neurophysiological responses to speech during early childhood: Effects of background noise. Hearing Research, 328, 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2015.06.009

Young, S. (2002). Young children’s spontaneous vocalizations in free-play: Observations of two- to three-year-olds in a day-care setting. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 152, 43–53.

Young, S. (2008). Collaboration between 3- and 4-year-olds in self-initiated play on instruments. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2007.11.005

Zećo, M., Videnović, M., & Žmukić, M. (2023). Sound improvisation through image and shape. Facta Universitatis, Series Visual Arts and Music, 9(2), 101-112. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUVAM231002009Z

Zhou, J. (2015). The value of music in children’s enlightenment education. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 3(12), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.312023