8. Influences of Physical and Imagined Others in Music Students’ Experiences of Practice and Performance

©2024 A. Schiavio, H. Meissner & R. Timmers, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0389.08

Introduction

Most musical activities can be carried out either individually, such as practicing with a musical instrument by oneself, or in a more social context, such as rehearsing or performing with an ensemble. These situations showcase different characteristics which bring particular pressures, challenges, and rewards. Nevertheless, offering clear-cut distinctions between social and individual contexts may be more difficult than expected. On the one hand, the felt presence of ‘others’ in solitary contexts could transform the individual nature of certain musical actions into a more intersubjective experience; on the other hand, a strengthened awareness of the ‘self’ in group situations can reveal in a clearer fashion the different subjectivities that contribute to the collective work. Music-making itself is strongly intersubjective: musicians may experience a ‘dialogue’ with the composer and assign agency to the music as represented by the score (Mak et al., 2022), in addition to experiencing the dialogue with other musicians happening in real-time, or in the past (Clarke et al., 2016). The social context of performance is often strongly felt by musicians, and seems to contribute to emotional peak experiences in the form of intense positive experiences of felt connection with the audience, and to emotional challenges and apprehension in reports of music performance anxiety (e.g., Perdomo-Guevara, 2014). In this chapter, we investigate this intersubjective dimension that often permeates musical performance and practice. We are interested in how social presence shapes and becomes part of the experience of performers and learners, and how different ways of engagement between musicians and ‘others’ are formed and qualitatively felt. To explore these aspects, we operationalised intersubjectivity1 as two main modes of social presence, namely physical presence and imagined presence. By doing so, we assume that we can also observe intersubjectivity when musicians engage with others who are only present in their thoughts, creating inner dialogues and establishing social relationships that take an imaginative form. This conjecture is in line with recent scholarship on interactive cognition and musical creativity, which increasingly places emphasis on the social components of mental life (Di Paolo & De Jaegher, 2012; Schilbach et al., 2013), as well as on the imaginative capacities that are central to thinking and acting musically (Hargreaves, 2012; Kratus, 2017). At the crossroads of these approaches lies research positing an intersubjective framing also in seemingly solitary contexts (Høffding & Satne, 2019). This work, in a nutshell, suggests that settings in which agents operate by themselves (e.g., when practising or composing music alone) should not be conceived of as separate from the broader network of cultural, social, and historical influences that drive and inspire musical activity (Clarke et al., 2016; Folkestad, 2011; Schiavio et al., 2022).

With this in mind, imagining others can be seen to stand between the two connected levels of intersubjectivity described by Fusaroli et al. (2012), where the latter is understood as ‘1. […] the articulation of continuous interactions in praesentia between two or more subjects. [… and] 2. As sedimented socio-cultural normativity: i.e., of habits, beliefs, attitudes, and historically and culturally sedimented morphologies’ (p. 2). Imagining others, indeed, displays a rather ambiguous status in that—at least in certain cases of vivid imaginative activity—it can feel as if interaction were in praesentia; as if, in other words, the imagined other(s) were physically present. This makes such a phenomenon particularly fascinating in the musical domain, where the role of others (e.g., listeners, co-players, teachers, etc.) is crucial for music’s various manifestations (see, e.g., Small, 1998). Specifically, we ask (1) in what sense can relevant musical ‘others’ (whether physically present or not) shape music-making activity? And (2) how does the influence of others vary depending on whether we are considering a performing or practising context? In what follows, we aim to address such questions by reporting on a qualitative study conducted with a small group of music higher education (MHE) students, whose verbal descriptions can help to increase understanding of intersubjectivity in musical contexts.

Method

Participants

Ethical approval was obtained through the Department of Music at the University of Sheffield. Following ethics approval, a total of 17 adult music students responded to a recruitment email. They were studying music performance at postgraduate level at MHE institutions of the second and third author in the Netherlands and in the UK, respectively. Taking part in this study was voluntary, and participants gave their written consent. Two individuals were excluded as they either did not give their consent or answered in an insufficient manner. This reduced the sample to 15 participants (7 women; 8 men), playing different musical instruments and genres (see Table 8.1). Their ages ranged between 21 and 32 years (M = 26.2 years; SD = 3.1). Each respondent was assigned a pseudonym (P1, P2, etc.) to ensure anonymity.

Table 8.1 Overview of the participants

|

Pseudonym |

Gender |

Age |

Musical genre played |

|

|

P1 |

M |

25 |

Classical guitar |

Classical |

|

P2 |

F |

26 |

Voice |

Classical |

|

P3 |

M |

27 |

Percussion |

Various |

|

P4 |

M |

28 |

Drums |

Rock and Jazz |

|

P5 |

F |

31 |

Piano |

Classical |

|

P6 |

F |

32 |

Piano |

Jazz, Pop, and Blues |

|

P7 |

F |

23 |

Voice |

Jazz |

|

P8 |

M |

28 |

Violin |

Classical |

|

P9 |

M |

24 |

Organ |

Classical |

|

P10 |

F |

25 |

Cello |

Classical |

|

P11 |

M |

21 |

Electric bass |

Metal |

|

P12 |

M |

27 |

Saxophone |

Rock |

|

P13 |

M |

30 |

Guitar |

Jazz and Classical |

|

P14 |

F |

22 |

Bass clarinet |

Classical |

|

P15 |

F |

24 |

Violin |

Classical |

Materials and procedure

The research team developed an open-ended questionnaire to explore the responses of music students when asked about the range of intersubjective experiences felt during practice and performance. Participants accessed the questionnaire online and were invited to type their answers on a Google form anonymously. The instrument comprised a first section dedicated to demographics and musical background, and a second one featuring eleven questions, to which respondents answered without a word limit. With these questions we invited participants to share their perspectives on practice and performance both as a solitary activity and in the presence of others. This involved exploring the differences between such situations and offering examples illustrative of the influence of others on emotions, feelings, and thoughts. Accordingly, we focused on the following modes of presence: (i) physical presence, that is, when someone else is present, whether passively or playing together (e.g., in the same room as the musician), and (ii) imagined presence, that is, when this ‘someone else’ is only present in the mind of the musician. To make sure the written responses could capture the continuities and differences between these types of presence, as well as elicit a variety of subjective characterisations of both phenomena, we developed deliberately broadly interpretable questions that could resonate with each musician and invite personal reflections about the (intersubjective) experiences permeating their musical practice and performance. The main part of the questionnaire can be found in the Appendix of this chapter.

Data analysis

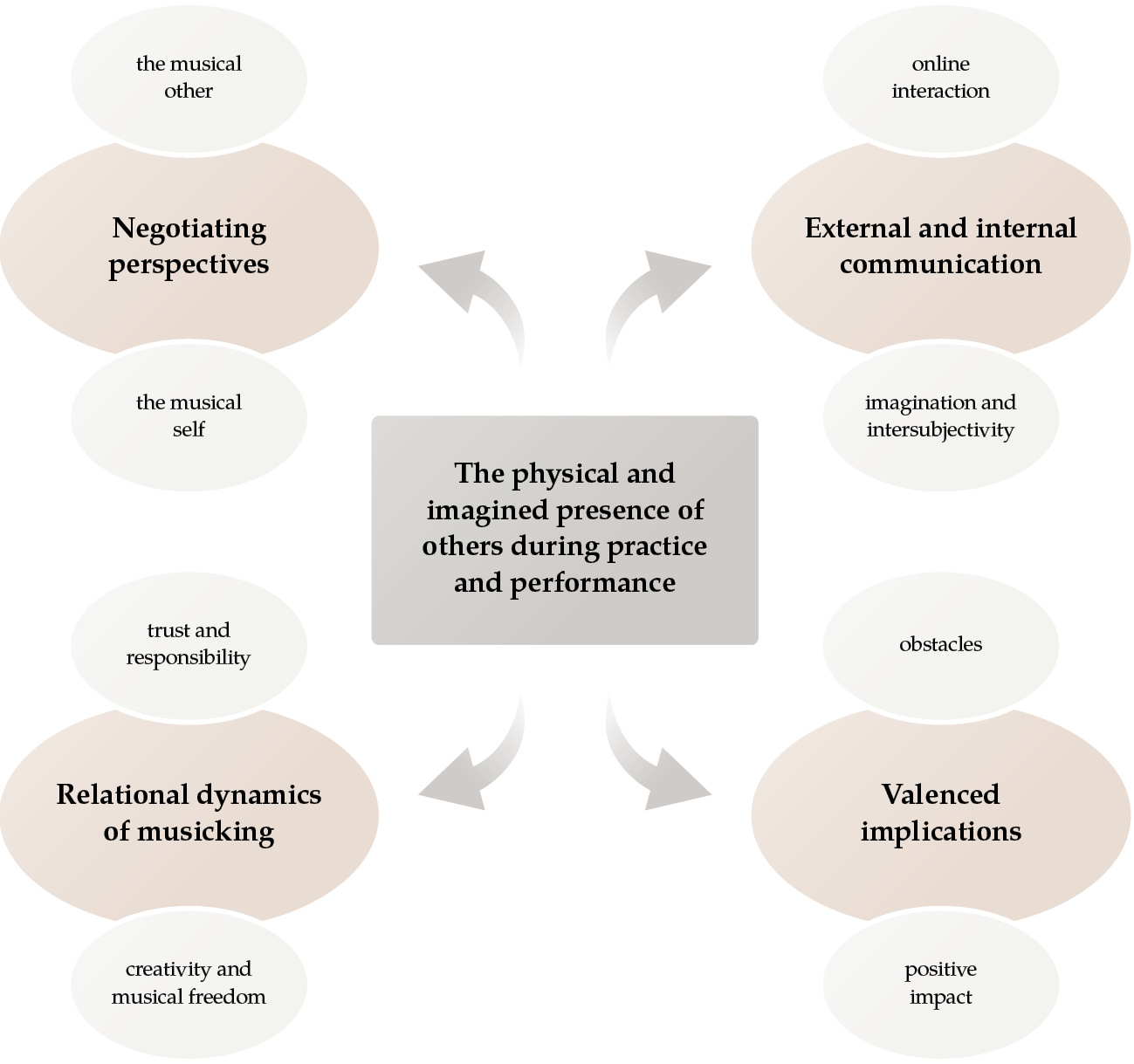

Given the exploratory nature of the research, data analysis was performed via a grounded theory approach (Oktay, 2012). This allows the researcher to look for meaningful units of analysis (i.e., codes referring to distinctive ideas, concepts, or experiences) directly in the data, and to systematise them into categories relating to more general dimensions. The analysis began with an immersion phase, where the raw data were read multiple times to gain familiarity with their content. Preliminary interpretations were noted through informal memos, so that the units of analysis could be generated contextually and, if necessary, modified. This gave rise to eleven codes. Subsequently, all raw data were merged into a single Word document, with each participant’s answers being segmented into shorter quotes. Where possible, these quotes were organised around the codes developed earlier on, assessed for intra-code coherence, and either kept, discarded, or moved to another code. During this phase, three codes were eliminated since many of the quotes associated with them could be submerged under other codes. This process was re-examined in a third phase of the analysis, where codes were systematically grouped into four broad categories with two codes each. The initial coding was done by the first author and independently verified by the second and third authors. The resulting coding scheme is depicted in Figure 8.1.

Results and discussion

Negotiating perspectives

This category includes statements referring to the way our respondents distinguish and negotiate between social-focused and individual-centred perspectives. It includes the codes ‘the musical other’ and ‘the musical self’.

The musical other

Not only is social participation a defining feature of music-making; it is also seen by one participant as a defining feature of who we are as a species:

We can only define ourselves as humans through other people. This also goes for the fact of being a musician. (P13)

This aspect of defining oneself in relation to others (or ‘the musical other’, as we will call it when stressing its musical connotations) is further elaborated by another participant:

I think our behaviour is strongly determined by how we interact with others and how we think the other sees us. I therefore think it’s impossible to not be impacted by others in practising, performing and any other things. (P1)

The same respondent also explains why such an investigation can reveal an important, yet often underplayed dimension; that is, the self-other dialectics that emerge in the musical moment:

It’s interesting to think about the concept of ‘the other’. In performances you cannot really see how the other sees you, you only have your own perspective, so you see your version of the other and you fill in how the other would see you. In that sense there might not be a big difference between a physical audience and an imagined audience. (P1)

One aspect at the heart of this form of self-other interplay, as the quotation suggests, is represented by a continuous change of perspective. Intersubjective experience appears to be systematically filtered by one’s own agency and subjectivity. Accordingly, the physical or imagined presence of others may, in a sense, feel the same: what matters is not primarily how the others manifest themselves, but rather how we react to their presence. This resonates with a reflection offered by another participant:

I think whether the presence of others affects you or not depends on your personality and the way you take things. If you feel affected [by] thinking about what others can say about your performance, their presence during your performance could affect you, but if you are confident enough with yourself and your performance, others’ opinions cannot cause you any problem. (P3)

Nevertheless, several participants mentioned that they are affected by the presence of others during practice or performance, and that this is very much dependent on the situation and on how they perceive the musical others, and whether they are seen as friendly and supportive or critical and evaluating:

It depends on how they react. For example, if there are friends and they enjoy what I practise, I feel good. On the other hand, if they judge my play, I feel very uncomfortable, and I don’t want to practise in front of them anymore. (P6)

While ‘the musical other’ manifests itself in a variety of forms, how this might affect one’s musicking seems to depend on the situation and on how one is attuned to it. Developing this view, the role of intersubjective presence in musical settings might be better understood if we re-orient the discussion towards a more self-centred perspective.

The musical self

As we have just seen, the focus on ‘the musical other’ lends itself naturally to a consideration of its complementary pole of interaction, that is, the (musical) self. This dimension emerges strongly when respondents are asked to define what performing music means to them. Consider the following statements from three different participants:

Performing music is presenting your musical voice, either in solo or in harmony with those you’re performing with, towards an audience. (P11)

‘Performing music’ means letting myself be carried away by the feelings and emotions that music produces in me. I perform to feel and to convey these feelings to the audience. (P5)

[Performing music is] showing myself and inviting [the] audience to my world; comforting myself and someone. (P6)

Note how these participants place emphasis on their personal perspectives (i.e., their own ‘musical voice’; ‘letting myself be carried away’; ‘inviting [the] audience to my world’), before letting others join in. Prima facie, this could be taken for a one-way communication model, in which the musician sends a musical message to an otherwise passive audience. However, as the last quote suggests, there is also a more active role for the latter: they are ‘invited’ to enter a personal space, one in which musicians and others can share something meaningful in the musical moment. This arguably gives rise to a less static process of give-and-take, where the presence of others can shape musical activity—including practice:

If I am thinking of others while practising, it will often be a motivator. Mainly this is of my teachers and how they motivate me to work on the things I may not […] want to practise in the moment. (P11)

However pervasive the presence of others may be, it should be clear that musicians do not ‘suffer’ from it passively. Instead, they are able to use their mental resources to adapt to it and to optimise their musicking accordingly:

I think it is not about the presence of others during practice or [performance], but rather the kind of thoughts I have and how I perceive the situation. When I started to realise that anxiety was not created by others but by the thoughts I had about them, I could focus more on music and started to enjoy what I was doing. (P5)

According to P5, it is important to work on a robust and confident musical self that can be informed or inspired by others, being at the same time defined by a strong sense of agency and competence. We explore these inner-outer dialectics in the next section.

External and internal communication

This category includes descriptions of how one can communicate with others when they are physically present, and when these latter are only constructed internally in the imagination. We use here the distinction between ‘online’ and ‘offline’ social cognition proposed by Schilbach (2014). The former term describes social cognition from an interactor’s point of view, whereas the latter focuses on the observer. It includes the codes ‘online interaction’ and ‘imagination and intersubjectivity’.

Online interaction

Despite the previously mentioned fuzzy or porous distinctions between the impact of imagined and actual others, some participants do highlight an important difference between such modes of presence:

With others physically present you are communicating your story to the others, and you will get a genuine reaction from them, [while] with others in your imagination you are just interacting with yourself and with your idea of the other. (P1)

Participants also explain how they adjust to others and foster communication:

[When] performing with others […] I often feel that I can be more focused on expressive and communicative intent because I have more contact with them on the stage and their physical presence reminds me that the performance is not only about technical competency. (P2)

This dimension of openness to others, importantly, also emerges during practice:

practising music with others […] means more teamwork: taking into account other people’s opinions, expressing yours and being more flexible. (P10)

It appears that this self-other dialogue when others are physically present gives rise to a range of explicit, intuitive forms of communication. These may arguably be associated with a more direct involvement of both parties when compared to situations where others are only imagined. The next code includes reflections that address the latter case.

Imagination and intersubjectivity

Experience teaches us that imagination can be extremely vivid. As such, within the musical settings being considered here, it might be hard to distinguish how others can impact on musical experience and behaviour based only on their mode of presence:

The feeling is the same if others are physically present or in my imagination. There have been times when while I was practising, I have thought that a certain person is listening to me, and I have noticed the nerves in my stomach. Suddenly my feelings change, and I worry about what that person might think. (P5)

This point is echoed in another example provided by a different respondent:

Sometimes [during performance] I try to remember someone whose smile brings me ease. If I think about the people who are watching in an evaluation context, I tend to get more tense and start losing control of what I’m doing. (P10)

It should be noted that the concrete consequences of engaging in such an imaginative practice may go beyond influencing one’s musical experience, reaching instead to a deeper dimension:

In practice, [imagining others] can [make me] feel quite safe but also a bit vulnerable because there is a recognition that this person really wants to understand your thoughts and imaginative ideas and that can be quite a personal thing. (P2)

This last statement suggests a subjective form of communication with the imagined other, as if the latter were not a product of the musician’s imaginative activity, but rather an independent sentient being. Of particular interest is the reported effect of such a peculiar, inner dialogue, in which the presence of the imagined other is felt as almost intruding upon the intimate spheres of one’s mental life. This could be a manifestation of anxiety. However, this was not further explained in the written responses. Perceiving others in the mind or in the surrounding environment, as we have seen, can thus give rise to different forms of inter- and intra-personal dialogue.

Relational dynamics of musicking

Recurring themes in the data are related to ‘trust and responsibility’ and ‘creativity’. This category explores how both dimensions play out in a social context, shaping relational dynamics.

Trust and responsibility

A great sense of responsibility was perceived both in solo and ensemble situations. As stated by one respondent: ‘[performing music is about] responsibility, having fun, and transmitting emotions’ (P4). And both forms of performance bring high responsibility in subtly different ways:

[Playing with others] feels safer because you are not in the spotlight and yet at the same time more compromising because of the responsibility of being only one part of the whole. (P10)

When I am playing with others, the group itself forces me […] to keep doing what I am doing better. (P3)

When I perform music alone, I feel like I have all the responsibilities such as drummer, bassist, and other melodic instrument players. (P6)

When performing alone all the responsibility is on you to play well. In a way that is nice because you know what you are capable of and if something goes wrong it is usually easier to fix because you are the only person involved. (P9)

These responses indicate a sharing of responsibility with others, which requires trust and a reliance on others. Often such sharing makes both performance and practice more enjoyable, as one participant illustrates in two different quotes:

I think when others are physically present in performance it’s much more likely to be able to enter a flow state. When I performed in Le Nozze di Figaro I feel like that happened also because we began to trust each other more through the rehearsals and we get real response and communication between the characters, rather than just repeating musical lines that are written in the score. (P2)

[When others are physically present while I’m practising], I feel like there is more trust in the room and less judgement. I’ve found that especially during opera rehearsals when people are physically present there can be more playfulness and curiosity and willingness to take more risks. When this hasn’t happened, and I notice that they are concerned about remembering lines or feeling a bit stuck in their body, it becomes harder to create a performance and feels that you can’t be as free in your freedom of expression and ideas. (P2)

Across all responses, there was no mention of the role played by imagined others in shaping trust and responsibility. Instead, rich descriptions were offered of how the physical presence of others contributes to creating a sense of shared responsibility. In addition, several participants mention how performing with others helps them feel safe and enhances their confidence (see below). Overall, positive experiences are reported when it comes to communicating and trusting others in music-making. As the last quotation also suggests, however, if joint musicking does not work properly, the presence of others might be detrimental for musical creativity and expression. In the next code, we explore these aspects in more detail.

Creativity and musical freedom

While the attribution of trust and responsibility to others often requires their physical presence, creative thought and action appear to be less constrained by such a mode of engagement with musical others. With respect to practice, one of the participants explains:

If you are practising technique, [imagining others] is not positive because this means that you are losing concentration. But if you are working on improvisation, for instance, it can inspire you. (P4)

The separation between practising technique and improvisation delineated here, where the influence of imagined others is considered as positive only for the latter, contrasts with a previously reported statement by P11—in which the mental presence of others is understood as a ‘motivator’. In a similar vein, imagining others might drive creativity:

In performance, I feel that when others are present in my imagination then it is possible to create a kind of spiral of ideas and have more possibility of risk-taking and being spontaneous. (P2)

The final line about risk-taking is particularly interesting, as one would expect more creativity to flourish when openly communicating with other musicians or audience members who are physically present. However, as the same participant explains: ‘Alone I feel like I can take a bit more time for the exploration of body and music’ (P2). The point is echoed by another music student as follows: ‘I feel more freedom when I practise alone’ (P1). It seems, then, that while responsibility and trust are particularly relevant when others are physically present (possibly due to direct musical exchanges occurring in real time), creativity and expressivity appear to be associated with self-focused attention (see Berkowitz & Ansari, 2010), where a quasi-interpersonal form of communication unfolds between the musicians themselves and their imagined others. As such, this code highlights a special role for imagined interaction with others in the relatively flexible setting of solo performance and practice.

Valenced implications

The implications of the thought processes and musicking with others were regularly negatively valenced, which we code as ‘obstacles’. This is contrasted with instances in which the presence of others did have a positive impact.

Obstacles

A prominent theme we touched upon in the code ‘The musical self’ is that of tension and anxiety—a sensation that musicians can feel intensely across a variety of contexts (see, e.g., Papageorgi & Welch, 2020). It is sometimes difficult to avoid being affected by someone else’s presence, particularly when they might assess and judge the performance, or when they have a strong emotional bond with the musicians. The following example speaks about the influence of the imagined presence of others:

I think having others present in your thoughts and imaginations can create a lot of pressure you put upon yourself. There you can feel the need to prove yourself and impress upon people what you can do and as those others are often the ones you feel a closer emotional connection to, you want to do the best you can. This can create a lot more unnecessary performance anxiety in contrast to being able to see them present in the room and their live reactions. (P11)

This point is restated by another participant as follows:

I normally feel uncomfortable when I imagine someone listening to my practice. This is because they are mostly the people who judge me in my thoughts. (P6)

Also, when looking at the physical presence of others during a performance—audience members particularly—a similar sense of tension arises in relation to their level of familiarity. For instance, one participant admits that ‘it all very much depends on how well I know the people’ (P1). Another participant explains:

In a more relaxed concert setting with an unknown audience, I may become more relaxed and comfortable in my physicality and therefore my performance. In a more formal environment (such as with juries, competitions etc.) this may add tension. If I am performing to an audience that features people I know, I feel more pressure to perform to a higher level. (P12)

This situation is not specific to performance, but can also occur during practice:

When I practise playing the piano, a little thought about someone watching makes me stumble and I will make a mistake for sure. (P7)

Getting rid of such daunting sensations is no easy task, and musicians might therefore try to reduce moments where they actively think of others. That said, it is generally more difficult to avoid situations where others are physically present, so musicians may use various techniques to feel more at ease:

During the group lessons, the fact that I feel observed and listened to attentively makes me feel nervous and my breathing is interrupted. I physically weaken and lose my grip on the keyboard. I must be very aware of my breathing and do a ‘bodyscan’ before playing to be able to control these sensations. (P5)

This last example aligns well with one of the major themes of our analysis, namely the focus on a self-centred view used as a resource to adapt to external perturbations. Nevertheless, many participants also describe the presence of others as a positive driver of performance and practice.

Positive impact

While the imagined or physical presence of others are understood as distinct situations with distinct phenomenologies and nuances, they arguably share more properties than one might expect. Amongst others, we have seen how they both have a real impact on the musicians as well as a particular relation with their emotional sphere:

I often use the imagery in my practice, so this—[…] depending on the circumstance—generally positively impacts my playing. It’s easier for me to play with feeling and emotion if I’m imagining/remembering something emotional. (P12).

If we assume that imagining others while musicking may give rise to a sort of inner dialogue, as we pointed out in the code ‘Imagination and intersubjectivity’, it appears that such an intra-personal experience may also facilitate musical expression and emotion, similarly to how it facilitates the generation of novel and valuable musical ideas and outcomes (see code ‘Creativity and musical freedom’). Furthermore, one of the positive aspects of the physical presence of others concerns the musician’s confidence:

I’ve noticed over time that the presence of others while practising has gone from placing a pressure on me to perform to a high standard to giving me confidence in showing an audience what I am able to do. (P11)

The same participant further elaborates on this idea, extending the same insight from practice to performance settings:

I think the presence of others has a great impact upon my confidence as a musician. Firstly, if you see the audience enjoying what you’re playing then it affirms what you’ve been doing and therefore your confidence can grow massively. Also, while the presence of others can create a form of pressure it can also give you the encouragement you need to perform in the best way you can at that moment. (P11)

Several participants report that performing together with others can also provide a feeling of safety, thus enhancing confidence:

[Performing] alone feels quite naked but you have the time for yourself and together you have the feeling that the others can provide a safety net. (P14)

Interpreting in a group I feel more sheltered. Eye contact and a smile while playing gives me peace. (P5)

A possible way to boost confidence, which we believe many musicians are familiar with, is described as follows:

You can fake a live situation at home by imagining very strongly that you have to play in front of people. Your heart beats faster when you do this. Practising this really works when you find it hard to perform. (P13)

As we have seen earlier, the presence of others is never purely passively perceived. Rather, it triggers a more or less explicit response—an evaluation, or a coping mechanism that is often self-centred (e.g., a ‘bodyscan’ in the words of P5, or a reflection on the emotional components involved in musicking). Musicians seem to be open and receptive to the presence and actions of others, being at the same time ready to react in the most efficient way through reliance on a strong inner self.

Conclusion

Music is an intrinsically participatory phenomenon (Turino, 2008), but this is by no means confined to purely physical interaction. The imagined co-production of musical parts played by others has been shown to causally contribute to synchronisation (Novembre et al., 2014) and accuracy of turn-taking (Hadley et al., 2015). Furthermore, imagining an audience has been advocated as a technique to prepare for public performance (Connolly & Williamon, 2004), and mental rehearsal through listening and imagining one’s own and others’ parts is a known strategy to advance practice and performance (Clark et al., 2011). In the present chapter, we have contributed to such research areas by exploring how social presence shapes and becomes part of the experience of a group of advanced music performers and learners, and how different modes of social engagement (i.e., physical and imagined presence) are qualitatively felt.

In response to our first research question—in what sense can relevant musical ‘others’ (whether physically present or not) shape music-making activity—we note that participants often focused on those shifts between attention oriented inward and outward which, in many cases, accompany the presence of others. Respondents combined socially oriented descriptions with analyses of self-centred processes. Such an inner-outer dialectic aligns well with the notion of ‘dual intentionality of music-making’ (Høffding & Schiavio, 2019), which examines how making music is both directed towards external (social) domains, and towards a more intimate dimension, strongly associated with agency and selfhood. This dialectic between internal and external focus was felt in relation to responsibility and agency, a sense of competence and vulnerability where others were seen as either motivators and supporters, or as judges, or a source of distraction. Inner strength and competence (‘my voice’) was felt to be important in this context of high-performance demands. In other descriptions, such a dialectic gave way to a more integrated sense of self and other, with references to ‘our energy’, group creativity, and sheltered performance. This was primarily described in the context of performing with others, but imagined others could, for some, also play a role in promoting creativity or sharing responsibility.

Engaging with others musically, we suggest, involves a continuous renegotiation of individual focus, involving both internal and external aspects, regardless of the nature (i.e., physical or imagined) of the other(s) being present. This relates to the sense of communication that our participants reported to be part of their musicking, and that includes others who are imagined or physically present. Internal and external focus are closely associated, in line with explanations by participants of the narrow distinctions between physical others and imagined others: one cannot fully know what others think even if they are present, and since imagination can be extremely vivid, concrete (positive or negative) implications are physically experienced even in the absence of others. This proximity also works the other way around: an external focus on audiences as judges can be strongly internally oriented, as they may represent personal fears and developed processes of self-evaluation. The seeking of approval was seen as unavoidable, but also something that many participants sought to free themselves from, both in practice and performance.

This brings us to our second research question: how does the influence of others vary depending on whether we are considering a performing or practising context? In general, performing together with other musicians was seen by most as an enjoyable and creative experience, in which co-players provide safety and confidence. Conversely, imagining others during practice was seen by most as a sign of intrusive thoughts or distraction, which could lead to feeling vulnerable when playing. However, imagining others could also serve a variety of positive functions, including pre-experiencing performance situations during practice and inspiring expressivity and creativity. Whilst the presence of an observing audience often leads to considerable negative feelings, as known from the extensive literature on performance anxiety (see Chapter 15 in this volume), the goal of performance has been described as to share one’s ‘story’ and musical interpretation with others. And, indeed, musicians who focus on communication with imagined or physically present audiences may enjoy their musicking more than those who see the latter as evaluators. But while it might be liberating to focus on communication and expression in such cases, the references to tension in several responses suggest that this is not easy and requires practice. One participant, for example, refers to the detrimental effects of recurring negative feedback:

Sometimes the things people have said or done to you can resonate with you as you’re playing. […] I know many great musicians [who] have the negative words of past teachers ‘ringing in their ear’ as they play and practise. The continuous negativity impacts their confidence, playing, and thus their ability to enjoy music. (P12)

This vivid description highlights the importance of raising awareness of the risks connected to a ‘pedagogy of correction’ (Bull, 2022) in music education. It is important to foster safe learning environments where musicians can focus on connection and communication rather than perfection and evaluation (Meissner et al., 2022). Future research could build on the method and findings of this chapter to encourage musicians to make explicit their thought processes and perspectives on self and others during practice and performance. This may involve exploring shifts of attention between internal and external focus, examining their associated subjective experiences, and investigating how a sense of joint effort and intersubjectivity can be described and enhanced when musicking. This chapter has highlighted the multitude of roles of the self and others in music performance and practice, and the relevance of these perspectives on the felt experiences of a cohort of music students.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the students who took part in this study.

References

Berkowitz, A.L., & Ansari, D. (2010). Expertise-related deactivation of the right temporoparietal junction during musical improvisation. Neuroimage, 49(1), 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.042

Bull, A. (2022). Equity in music education: Getting it right: Why classical music’s “Pedagogy of Correction” is a barrier to equity. Music Educators Journal, 108(3), 65–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/00274321221085132

Clarke, E., Doffman, M., & Timmers, R. (2016). Creativity, collaboration and development in Jeremy Thurlow’s ‘Ouija’ for Peter Sheppard Skærved. Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 141(1), 113–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690403.2016.1151240

Clark, T., Williamon, A., & Aksentijevic, A. (2011). Musical imagery and imagination: The function, measurement, and application of imagery skills for performance. In D.J. Hargreaves, D.E. Miell, & R.A.R. MacDonald (eds), Musical Imaginations: Multidisciplinary perspectives on creativity, performance, and perception (pp. 351–365). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199568086.003.0022

Connolly, C., & Williamon, A. (2004). Mental skills training. In A. Williamon (ed.), Musical excellence: Strategies and techniques to enhance performance (pp. 221–245). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198525356.001.0001

Di Paolo, E., & De Jaegher, H. (2012). The interactive brain hypothesis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, Article 163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00163

Folkestad, G. (2011). Digital tools and discourse in music: The ecology of composition. In D.J. Hargreaves, D.E. Miell, & R.A.R. MacDonald (eds), Musical Imaginations: Multidisciplinary perspectives on creativity, performance, and perception (pp. 193–205). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199568086.001.0001

Fusaroli, R., Demuru, P., & Borghi, A.M. (2012). The intersubjectivity of embodiment. Journal of Cognitive Semiotics, 4(1), 1–5. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/cogsem.2012.4.1.1/html?lang=en

Hadley, L.V., Novembre, G., Keller, P.E., & Pickering, M.J. (2015). Causal role of motor simulation in turn-taking behavior. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(50), 16516–16520. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-15.2015

Hargreaves, D.J. (2012). Musical imagination: Perception and production, beauty and creativity. Psychology of Music, 40(5), 539–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735612444893

Høffding, S., & Satne, G. (2019). Interactive expertise in solo and joint musical performance. Synthese, 198(1), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02339-x

Høffding, S., & Schiavio, A. (2019). Exploratory expertise and the dual intentionality of music-making. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 20, 811–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-019-09626-5

Kratus, J. (2017). Music listening is creative. Music Educators Journal, 103(3), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432116686843

Mak, S.Y., Nishida, H., & Yokomori, D. (2022). Agency in ensemble interaction and rehearsal communication. In R. Timmers, F. Bailes, & H. Daffern (eds), Together in music: Coordination, expression, participation (pp. 35–43). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198860761.003.0004

Meissner, H., Timmers, R., & Pitts, S.E. (2022). Sound teaching: A research-informed approach to inspiring confidence, skill, and enjoyment in music performance. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003108382

Novembre, G., Ticini, L.F., Schütz-Bosbach, S., & Keller, P.E. (2014). Motor simulation and the coordination of self and other in real-time joint action. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(8), 1062–1068. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst086

Oktay, J.S. (2012). Grounded theory. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199753697.001.0001

Papageorgi, I., & Welch, G.F. (2020). ‘A bed of nails’: Professional musicians’ accounts of the experience of performance anxiety from a phenomenological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 605422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.605422

Perdomo-Guevara, E. (2014). Is music performance anxiety just an individual problem? Exploring the impact of musical environments on performers’ approaches to performance and emotions. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 24(1), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000028

Rabinowitch, T.-C., Cross, I., & Burnard, P. (2012). Musical group interaction, intersubjectivity, and merged subjectivity. In D. Reynolds & M. Reason (eds), Kinesthetic empathy in creative and cultural practices (pp. 109–120). Intellect Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290857650_Musical_group_interaction_intersubjectivity_and_merged_subjectivity

Sawyer, K.R. (2003). Group creativity: Music, theater, collaboration. Erlbaum.

Schiavio, A., Ryan, K., Moran, N., van der Schyff, D., & Gallagher, S. (2022). By myself but not alone. Agency, creativity, and extended musical historicity. Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 147(2) 533–556. https://doi.org/10.1017/rma.2022.22

Schilbach, L. (2014). On the relationship of online and offline social cognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, Article 278. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00278

Schilbach L., Timmermans, B., Reddy, V., Costall, A., Bente, G., Schlicht, T., & Vogelay, K. (2013). Toward a second-person neuroscience. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(4), 393–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12000660

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Wesleyan University Press.

Turino, T. (2008). Music as social life: The politics of participation. University of Chicago Press.

Appendix

Questionnaire

- What does practising music mean to you?

- What does performing music mean to you?

- What are the main differences for you between practising music alone or together with others*?

- What are the main differences for you between performing music alone or together with others?

- How do you feel (in terms of emotions or physical sensations) during your musical practice when others are physically present? Please provide examples based on your personal experience.

- How do you feel (in terms of emotions or physical sensations) during your musical performance when others are physically present? Please provide examples based on your personal experience.

- How do you feel (in terms of emotions or physical sensations) during your musical practice when others are present in your imagination or thoughts? Please provide examples based on your personal experience.

- How do you feel (in terms of emotions or physical sensations) during your musical performance when others are present in your imagination or thoughts? Please provide examples based on your personal experience.

- Do others (whether they are physically present or not) have an impact on your musical interpretation? Please explain.

- Do others (whether they are physically present or not) have an impact on your confidence as a musician? Please explain.

- Would you like to add anything else about your thoughts about others or the relevance of the presence of others for your musical performance and practice?

* Others may include teachers, ensemble members, other students, friends, audience, family members, etc.

1 We understand intersubjectivity as the sense of individuals sharing meaning with others and functioning as part of a larger whole that has been described as a powerful experience in a range of musical contexts (see, e.g., Rabinowitch et al., 2012; Sawyer, 2003).