14. The CIX Archives: Revalorizations and Hidden Treasures

Cyrille Delhaye

© 2024 Cyrille Delhaye, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.16

The work conducted on the conservation and valorization of the archives of the Centre Iannis Xenakis (CIX) since 2010 shows that the main collection includes all the archival documents of the association Les Ateliers UPIC (renamed the Centre de Création Musicale Iannis Xenakis (CCMIX) in 2000, before being renamed CIX in 2009).1 This association, founded by Iannis Xenakis in 1985, aimed to promote the UPIC, a machine for aiding composition through drawing, invented in 1977 at Xenakis’s research center, the Centre d’études de mathématique et automatique musicales (CEMAMu), through a whole series of pedagogical actions, composition workshops, and concerts throughout the world. Among the traces left by composers who came to Paris to compose on UPIC, a folder constituted by Iannis Xenakis for Taurhiphanie (1987) catches one’s attention: it regroups compositional materials, UPIC pages, contextual archives, photographs of the first performance, etc. These documents highlight some aspects of the genesis of this polymorphic work, created in the Arles Arena (France) in 1987 for a real-time UPIC, percussion ensemble, horses, and bulls.

After presenting an update on the work in progress for the conservation and valorization of the CIX collections since 2010, we will dive into the depth of the collection by analyzing and contextualizing the traces left by Xenakis when composing Taurhiphanie.

What Is UPIC?

In the 1950s, Iannis Xenakis had the intuition to develop a machine that would allow him to free himself from the limitations of traditional musical notation, while simplifying the exploration of this new way of composing: in his mind, this instrument would facilitate, for example, the graphic and sonic transcription of the glissandi in his 1954 work Metastasis. But it was only in 1977 that the prototype of a machine hybridizing drawing, sound synthesis, and music was born in his research center the CEMAMu: it was named UPIC (Unité Polyagogique Informatique du CEMAMu), a name that evokes the double vocation of this machine to be both for composition and for pedagogy. In its first version, the UPIC consisted of a large graphic table, a magnetic pen, and a sound signal calculation interface. It allowed the composer to conceive all the elements of a musical work visually, from the micro to the macro form, by hybridizing within a single system its formal conception, waveforms, and sound synthesis.

Fig. 14.1 Photo of a UPIC Workshop in Aix-en Provence, France (1985), with, at the desk in front of the UPIC set-up, composer Pierre Bernard (left) and director of Les Ateliers UPIC Alain Després (right). Photo by Henning Lohner. Archives of the Centre Iannis Xenakis, Lohner collection.

The archives of the Centre Iannis Xenakis reveal the traces left by circa 130 composers who worked at Les Ateliers UPIC/CCMIX between 1985 and 2009. For example, we find traces of work on the UPIC by François-Bernard Mâche (b. 1935), Luc Ferrari (1929–2005), La Monte Young (b. 1935), Brigitte Robindoré (b. 1962), Julio Estrada (b. 1943), Jean-Claude Risset (1938–2016), Roger Reynolds (b. 1934), Curtis Roads (b. 1951), Daniel Teruggi (b. 1952), and many others. In addition, the innumerable educational activities carried out in France and abroad by the association around UPIC are also reflected in this rich, unpublished, and very heterogeneous collection of documents.

The CIX Collections

The main collection of the CIX embraces more than twenty-five years of research and creation around UPIC. The fifty linear meters of archives deposited at the Service Commun de la Documentation of the Université de Rouen Normandie (University library) are composed of manuscripts, drawings, scores, tapes, records, DATs, books, press, correspondence, etc. It is a collection that is certainly small and specialized, but which synthesizes the general problems related to the management of contemporary music archives. From this point of view, this collection is particularly interesting to study, for the following reasons:

- Heterogeneity of data and multimedia supports: magnetic tape, DAT, QIC cartridges, burned CD, etc.

- Variety of printed materials: large posters, scientific and scholarly literature (including grey literature), equipment manuals, flip charts from summer sessions around UPIC, manuscripts, typescripts on onionskin paper, etc.

- Unpublished musical recordings, some anonymous.

- A very diverse collection of scores: manuscripts, copies, many resulting from the calls for composition competitions and workshops organized by the association, as well as several UPIC scores (on fax paper).

- Obsolete software used by composers.

- All the problems related to the rights of use of these materials.

Furthermore, this collection regularly benefits from bequests from collaborators, dedicatees, and other friends of Iannis Xenakis. Robert Dupuy (1945–2018), engineer and close collaborator of Xenakis, for example, entrusted three linear meters of his personal archives related to the first Polytope of Cluny (1971–72), the first event in Europe where lasers were introduced. These documents can now open the way to an authentically informed reinterpretation of this great “music and light work” initially presented in the medieval thermal baths in Paris (les Thermes de Cluny). Documents include the original source code, scores, photos, correspondence between Dupuy and Xenakis, and various suppliers, etc. This collection was recently processed by Daniel Teige, another founding member of the CIX, as part of a joint research residency between our university and the Hochschule für Kunst in Bremen. Teige will curate both a “hard copy” and a virtual exhibit from this extraordinary bequest in the near future.

New Archival Holdings2

Other new archives have been added to the initial collection and are waiting to be processed so they can all be utilized:

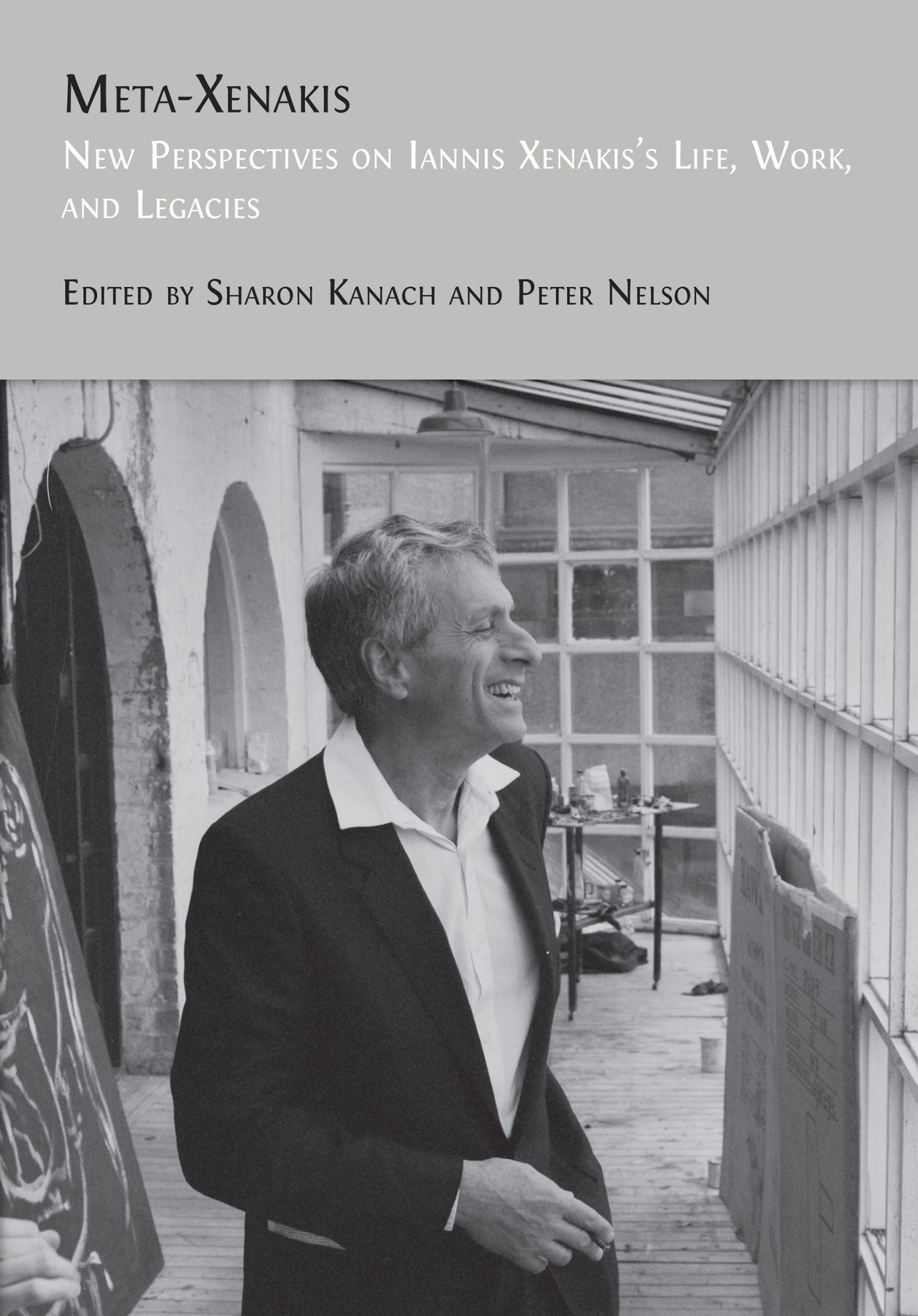

- Henning Lohner (b. 1961), a former student of Xenakis. This collection includes numerous photos of Xenakis in all sorts of situations (personal, in rehearsal, giving lectures throughout Europe), and with other composers such as John Cage (1912–92), Frank Zappa (1940–93), Pierre Boulez (1925–2016). It contains over a thousand photographs and six hours of film in all (see Figure 14.1 as well as throughout this volume, including the cover).

- Marie-Hélène Serra (b. 1960), a former collaborator of Xenakis at CEMAMu. This is an important collection estimated at about five linear meters, including boxes of working notes, articles, and documentation related to her years at CEMAMu, where she mainly worked on the GENDYN program (a dynamic stochastic approach to waveform synthesis).

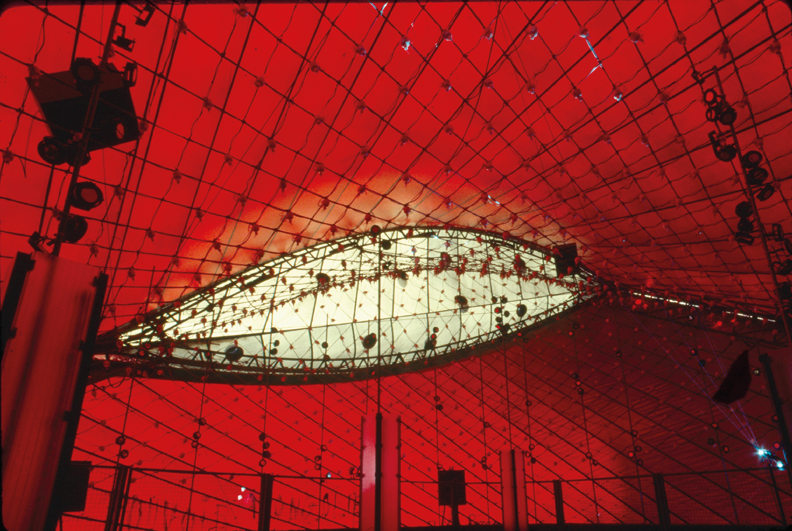

- Bruno Rastoin (1954–2020), visual artist and scenographer, and collaborator with Xenakis on the Diatope, a work created in 1978 on the public square of the Centre Georges-Pompidou in Paris. Most of this collection has been digitized and cataloged. It consists of numerous photos of the Diatope—another polytope, like the Polytope of Cluny mentioned above—but one where Xenakis also designed the architecture. Its presentation in both Paris and Bonn, its construction and dismantling, and the light show itself are documented.

Actions for Revalorizing the Rastoin Collection

In 2022, as part of the Meta-Xenakis centenary events, a group of musicology students from the Université de Rouen Normandie (Master’s Research cursus) immersed themselves in the CIX archives to create an exhibition that shows the genesis of the Diatope through photographs and unpublished documents at Bruno Rastoin’s bequest.3 The exhibition was inaugurated on 22 April 2022 at the Maison de l’Université (MDU, or campus student center) in Rouen, and a virtual rendering will soon be published on CIX’s website.

Fig. 14.2 Iannis Xenakis’s Diatope, interior view. Photo by Bruno Rastoin (1978). Archives of the Centre Iannis Xenakis, Rastoin collection.

The CIX Website

Since 2012, the CIX has also launched a website using Omeka, a free and opensource content management system (CMS), which exposes a part of the fifty linear meters of its physical (and partially digitized) archives and their associated metadata in the Dublin Core format.4 Even if Dublin Core does not have a fine granularity of data description, this set of metadata guarantees maximum interoperability from one system to another, and requires limited library and technical knowledge. In addition, Omeka allows the possibility of many custom fields in a second metadata set. Concerning the CIX archives, in the current state, the 3,500 records of the FileMaker inventory are in the CMS. Approximately 2,500 records are available in public mode; the general inventory of the CIX archives (“mother collection”) is available as a downloadable PDF file.5

KSYME and CIX

Since January 2015, CIX and KSYME/CRCM (Contemporary Music Research Center), housed at the Athens Conservatoire, have a project to create a joint library of their respective digitized archives in connection with Xenakis and/or UPIC. The KSYME/CRCM was founded in 1979 in Athens by Iannis Xenakis, John G. Papaioannou (1915–2000), and Stephanos Vassiliadis (1933–2004). The KSYME acquired a UPIC in 1986. The KSYME originally worked in the same way as the historical Ateliers UPIC/CCMIX did in Paris: running educational programs for children and the general public, and courses in music composition organized around the UPIC. In order to create this common digital library, an open archive repository (based on the OAI-PMH protocol) will be set up between our two Omeka instances: it will allow users to perform federated searches on the archival collections of both centers in a transparent way. CIX already uses the OAI-PMH protocol to disseminate archives to other research centers: the CIX archives were, for example, harvested by the Contemporary Music Portal from 2014 and more recently by Isidore, the federated search engine for Humanities data in France.6 This work on a common digital library is in progress: KSYME has already started to digitize some of its archives and is exposing them on an Omeka instance.

Focus on Taurhiphanie

Let us now dive into the heart of the matter to discover the traces left by Xenakis himself around the genesis of a work: Taurhiphanie.

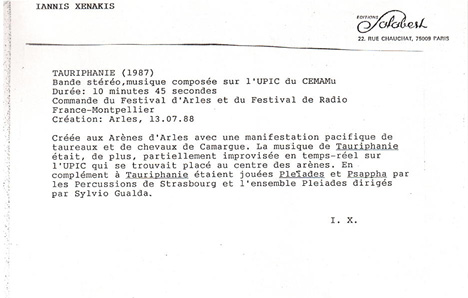

Taurhiphanie was first performed on 13 July 1987, in the Arles Arena following a commission from the Festival d’Arles and the Festival Radiophonique France-Montpellier. This work—composed by Xenakis on the UPIC—is written for a two-track stereo tape, lasting ten minutes and forty-five seconds. This work has the particularity of involving a group of bulls that influence the course of the show during its creation in the arena of Arles. According to this typescript from the CIX archives (Figure 14.3), the premiere of Taurhiphanie was programmed with two other works by Xenakis: Pléïades (1978) and Psappha (1975), performed by the Pleiades Ensemble directed by Sylvio Gualda (b. 1939).

Fig. 14.3 Program note for Taurhiphanie by Iannis Xenakis (ca. 1987). Université de Rouen Normandie, CIX Archives, CIX 43, typescript.

As Xenakis pointed out to Bálint András Varga (1941–2019) in 1989, Taurhiphanie is a neologism he coined from tauros (bull), hippos (horse), and epiphany (apparition).7 Ramón del Buey Cañas and Oswaldo Emiddio Vasquez Hadjilyra, in Chapter 8 of this volume, develop the foundations of these semantic associations and how they shed light on Xenakis’s creative processes, particularly for Taurhiphanie. Also noteworthy is the work of Pierre Couprie, who in 2020 compiled an inventory of primary sources available for Taurhiphanie for the purpose of musical analysis.8

Taurhiphanie and “Live Elements”

As Maurice Fleuret (1932–90) pointed out, beginning with his Polytope de Persépolis (1971), Xenakis frequently introduced live elements in the conception of his Polytopes.9 Furthermore, in an interview, Xenakis recalled the creation of Taurhiphanie by stating:

Taurhiphanie was a summation of my dreams about the archaic Mediterranean past. The gods—Baal, Apis, the Minotaur, and Zeus, transforming himself into a bull to kidnap Europe, but who had grown up with the deafening percussion of the Corybantes, the divine and talking horses of Achilles [...] Of course, out of the two hundred bulls I had been hoping for, I only got 25! A symbol, and still speechless! But this modern day smallness was corrected by the few mares, who had come with their foals and two studs, whose beauty of undulations, fears, and erotic attractions were mixed, and who, all touched by grace, intermingled in an unequalled perfection of movement; and my music, with this animal participation, then became Nature. In addition to the “human” music of the percussionists, the animals, [there was] the music composed on the UPIC with the help of computers.10

Approximately one month before the premiere, Xenakis further revealed to Brigitte Massin (1927–2002) that the performance would finally unfold in four parts, with the third part for UPIC being framed by compositions for percussion. Xenakis specified to Massin that the arena would be fully equipped with sound reinforcement and that a tower would be erected in the center of the arena, on which a UPIC table would be installed. From this vantage point, Sylvio Gualda also would conduct the percussionists (the Pléïades Ensemble, and the Percussions de Strasbourg)11 arranged in a circular formation in the front rows of the stands around the arena, while Iannis Xenakis would stand there to conduct, in real-time, Taurhiphanie, specially created for the occasion.12

Fig. 14.4 Photograph of the creation of Taurhiphanie (13 July 1987). Université de Rouen Normandie, CIX Archives, CIX 20.

The spectacle would proceed as follows: the first to make their entrance are the horses, the mares each accompanied by their foals, along with two stallions led on a lead.13 For the composer, this marks the opening parade, accompanied by the percussion sounds of Idmen-B (1985), initially composed for Europa-Cantat festival in Strasbourg. Once the horses leave the arena, the percussionists perform Pleïades (1978) under the direction of Sylvio Gualda.14 Then the bulls arrive in numbers—though Xenakis was hoping for thirty to fifty at this stage, he will ultimately only manage to get around twenty of them—to create Taurhiphanie.15 Finally, once the bulls exit, Xenakis exits and allows Psappha (1975) for solo percussionist to close the show.16

UPIC Back to Front

With Taurhiphanie, Iannis Xenakis hijacked the UPIC from its primary vocation, which was to generate synthetic sounds in order to arrange them visually by drawing on a graphic table. Here, Xenakis used UPIC “back to front”: he starts with sounds from natural patterns to generate the shape of the work. In this, he used UPIC in the manner of his long-time friend, the composer François-Bernard Mâche. Indeed, as soon as Mâche discovered the UPIC system in October 1978, he proposed an expanded use of it, or even a complete hijacking.17 Whereas Xenakis conceived UPIC as a means of facilitating the conception and realization of graphic scores made with sounds generated by sound synthesis, Mâche was essentially interested in a marginal functionality of the UPIC prototype: its sampler.18 Mâche rejected the idea of projecting a theoretical speculation onto the machine and then listening to the sonic result. In his first work for UPIC (Proteus, composed in 1980), he preferred to use the machine as a graphic editing table for pre-recorded sounds of batrachians. Moreover, in the last part of Hyperion written in 1988, Mâche used the UPIC as a tool to hybridize synthesized sounds with recordings of birds and amphibians.

Here, for the composition of Taurhiphanie, Xenakis obtained most of the waveforms (or samples) by recording bull sounds. A video archive from the Centre Iannis Xenakis shows Iannis Xenakis and a team recording the sounds of bulls in the Camargue countryside, in southern France.19 As he tells a journalist in this video, he hopes to record “sounds of their voices, sounds of nostrils, sounds of trampling [...] all kinds of noises that are part of the bull’s environment.”20 The sounds collected in the field were then reworked in the studio, input into the synthesis engine of UPIC, and then arranged graphically on UPIC pages. Finally, those UPIC pages were sequenced to form the final composition.

Improvising with UPIC

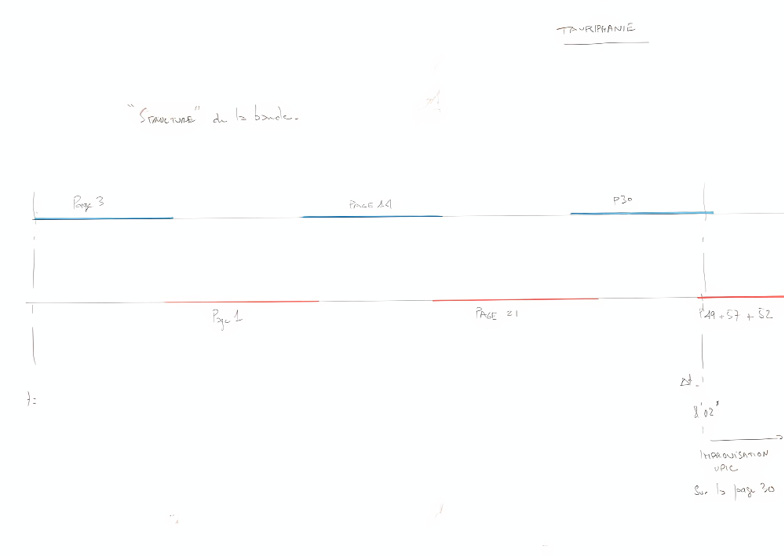

Most of the UPIC pages of Taurhiphanie are intended to be played in concert without structural or envelope modifications. However, as shown by an archive from the Centre Iannis Xenakis (Figure 14.5), for the last two minutes of the work Xenakis decided to exploit an experimental feature of UPIC in 1988: real-time composition.

Fig. 14.5 Taurhiphanie: Structural diagram of the tape, Anonymous (ca. 1987). Université de Rouen Normandie, CIX Archives, CIX 43.

On the document intended to accompany the performance of the piece (Figure 14.6), it is specified: “For the last part of Taurhiphanie, starting at 8′02″ (the section composed of pages 49, 57, 52), UPIC and its ‘master’ will play page 30, which is also the previous one.”

Fig. 14.6 User manual for Taurhiphanie, Anonymous (ca. 1987). Université de Rouen Normandie, CIX Archives, CIX 43.

The real-time UPIC was developed by the CEMAMu engineers in 1987. According to Jean-Michel Raczinski, it is:

[…] a radical evolution, simply because the result is instantaneous. Better still, you can modify an object (a waveform, an envelope, etc.) and hear the effect as it is modified. […] one can now work on truly complex pages, which was not possible due to the computation time of the deferred-time systems; we can also use UPIC like a musical instrument on which we improvise from previously written material.21

In the last section of Taurhiphanie, Xenakis imagined being able to react to the stimuli of the immediate environment in the arena: movements of the bulls and horses, lighting effects, reactions of the public, etc. To achieve this, Xenakis equips the horns of the bulls with wireless microphones: he hopes to collect the sounds of the animals in real-time to generate material for his improvisation on UPIC.22 Additionally, as James Harley (b. 1959) specifies: “Spotlights were to project patterns of light sounds onto the floor of the arena and the animals would create dynamic stochastic patterns as they moved around the ring.”23 Xenakis also explained to Brigitte Massin his desire to open the final part of Taurhiphanie to improvisation, based in the fact that this was now technically possible: “What interests me is that I am free to make my choices, my score allows for multiple paths, I can improvise on elaborated structures, and of course mix the elements to my liking.”24 The innovation of a real-time UPIC obviously changed Xenakis’s mind about improvisation, once he could be behind the controls himself, as a sort of comprovisateur.25

However, under the conditions of this concert, Xenakis could not precisely control the movement of the bulls and horses in the arena; in contrast, for example, to the Polytope de Persépolis (1971), where he had perfectly timed the movements of the children and the goats on the hills. It is perhaps from this constraint that the idea of improvising on the UPIC directly in the arena was born. But, according to the testimonies of people who attended the creation of Taurhiphanie, the bulls remained quite static, as James Harley specifies: “The animals did not cooperate in creating interesting stochastic patterns; they tended to huddle at one end of the ring or another, apparently traumatized by the pounding of the amplified percussion and the extreme dynamic range of the electronic sounds […] Taurhiphanie, though, remains as perhaps Xenakis’s most successful piece created using the UPIC.”26 Therefore, Xenakis preferred to use the previously recorded sounds of the bulls for the creation of the final part of Taurhiphanie, rather than those generated live by the animals in the arena.

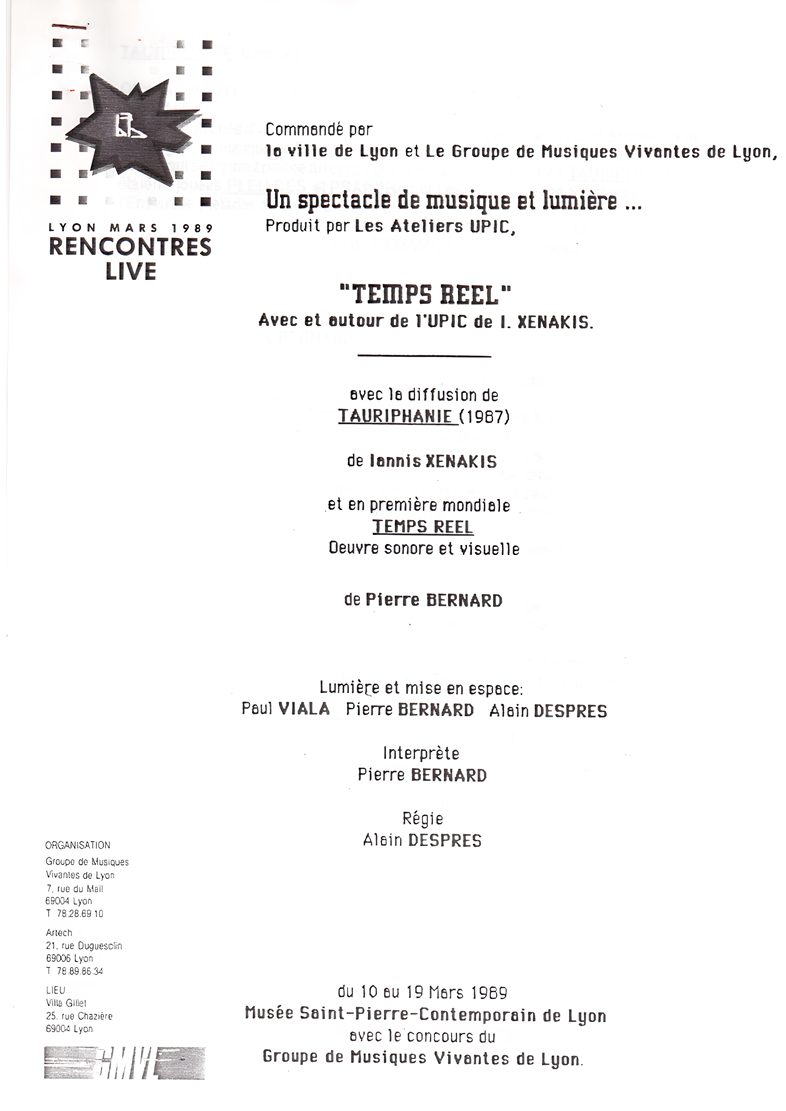

Fig. 14.7 Program note: Rencontres Live de Lyon, Anonymous (1989). Université de Rouen Normandie, CIX Archives, CIX 106, 2 p.

Despite this setback during the premiere, Taurhiphanie was nevertheless programmed several times for concerts and festivals. Alain Després, director of the Ateliers UPIC at their creation in 1985, had been particularly involved in promoting Xenakis’s UPIC works and had programmed Taurhiphanie on multiple occasions. In this sense, Alain Després’s approach fits perfectly within the missions defined by Xenakis himself for Les Ateliers UPIC, which aim to promote and enhance UPIC, thus enabling CEMAMu to actively pursue its research on the technical development of the system. The archives of the Centre Iannis Xenakis reveal, for example, the program notes (Figure 14.7) for the Festival des Rencontres Live organized in Lyon in 1989. This concert shows a strong desire to associate Taurhiphanie with other works composed for real-time UPIC, such as Pierre Bernard’s Temps réel (1989), a work entirely based on the new capabilities of UPIC, making it a full-fledged musical instrument.27 More recently, a DAT and a concert poster found in the CIX archives attest that Taurhiphanie was performed as part of a concert for flute, voice, and tape at the Théâtre des Nouveautés in Tarbes on 22 October 1997.28 Other works composed with the help of UPIC were also programmed there: one could notably hear Danse de Salomé (1993) by Hans Mittendorf (b. 1952), L’Autel de la perte et de la transformation (1993) by Brigitte Robindoré or Deux chansons (1993) by Gerard Pape (b. 1955).

Outlooks and Transition to the Semantic Web

This work on Taurhiphanie, based on the CIX archives, shows the richness of the Centre’s collections. But these collections offer so much more to discover! The paths of many of the numerous composers who worked in this creative center founded around UPIC have yet to be explored: the traces they left in the collections are preserved but await analysis. Currently, most documents from the main collection are inventoried, and some recent collections are cataloged. In their current state, the archives of CIX are described linearly: meaning that digitized documents are associated with metadata that are indeed interoperable with other information systems, but do not demonstrate the complexity of relationships between different objects. The relationships between composers, works, machines, software, locations, mediums, performers, educational activities, concerts, mediation activities, etc., are indeed rich and highly heterogeneous. Therefore, the CIX archives lend themselves to a semantic description by the triplet Object/Predicate/Subject. However, these relationships are not currently modeled in the information system, which hinders deep musicological exploitation of the archives. In order to address this issue, since 2022 CIX has engaged in the dynamics of the Musica 2 Consortium of the TGIR Huma Num to participate in discussions on ontological modeling of contemporary and electroacoustic music.29 Various avenues are emerging: the choice and adaptation of the CIDOC-CRM ontology, the possibility of integrating the ElectroAcoustic Resource Site (EARS) thesaurus, sharing of reference frameworks, etc.30 This work aims, over the medium term, to outline a common semantic language which, in addition to data interoperability, allows for the description of contemporary musical creation objects and the relationships they generate using the same concepts and within a common ontology.

Since 2013, by sharing and opening its research data, the CIX has aligned its approach with the philosophy of open knowledge, and has already embraced the concept of FAIR data (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable).31 Now, by aiming to initiate its transition towards the semantic web, the CIX is intensifying its efforts not only to make primary sources in this realm of contemporary music accessible to researchers, but also to enable them to analyze and annotate the complex relationships generated by this type of musical creation.

References

COUPRIE, Pierre (2020), “Analytical approaches to Taurhiphanie and Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède by Iannis Xenakis,” in Peter Weibel, Ludger Brümmer, and Sharon Kanach (eds.), From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today, Berlin, Hatje Cantz, p. 434–57, https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today

DELHAYE, Cyrille (2020), “François-Bernard Mâche et l’UPIC de Iannis Xenakis: entre modèles naturels et synthèse sonore,” in Marta Grabocz (ed.), Modèles naturels et scénarios imaginaires dans les oeuvres de Peter Eötvös, François-Bernard Mâche et Jean-Claude Risset, Paris, Hermann, p. 173–85.

DELHAYE, Cyrille and KANACH, Sharon (2022), “Creating New Cultural Content from Old Archival Materials: Centre Iannis Xenakis,” IAML Congress, Prague, 24–29 July 2022, https://www.iaml.info/sites/default/files/pdf/iaml-2022-xenakis-delhaye-kanach-slides.pdf

FLEURET, Maurice (1971), “L’anti-son et lumière: 2300 ans après Alexandre, un Grec embrase Persépolis, mais dans un grand feu de joie. Iannis Xenakis au 5ème Festival des Arts de Chiraz” (3 September), Le Nouvel Observateur, p. 43.

HARLEY, James (2002), “The Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis,” Computer Music Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, p. 33–57, https://doi.org/10.1162/014892602753633533

MÂCHE, François-Bernard (2020), “The UPIC Upside Down,” in Peter Weibel, Ludger Brümmer, and Sharon Kanach (eds.), From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today, Berlin, Hatje Cantz, p. 357–77, https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today

MATOSSIAN, Nouritza (2005), Xenakis, Nicosia, Moufflon Publications.

RACZINSKI, Jean-Michel (2001), “L’UPIC, outil de composition pour quelles musiques?,” in Sylvie Dallet and Anne Veitl (eds.), Du sonore au musical, Cinquante années de recherches concrètes (1948–1998), Paris, L’Harmattan, p. 77–87.

VARGA, Bálint András (1996), Conversations with Iannis Xenakis, London, Faber and Faber.

WEIBEL, Peter, BRÜMMER, Ludger, and KANACH, Sharon, (eds.) (2020), From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today, Berlin, Hatje Cantz, https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today

WILKINSON Mark D. et al. (2016), “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship,” Scientific Data, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 160018, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

XENAKIS, Iannis (1988), “Le mois de Iannis Xenakis,” in Le Journal de l’année, Paris, Larousse, p. 105.

XENAKIS, Iannis and MASSIN Brigitte (1987), “Le compositeur à Arles, Xenakis dans l’arène,” Le Matin de Paris (19 June), p. 21.

1 Centre Iannis Xenakis, https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org

2 This report on the current state of the archive is based on a paper given by the author with Sharon Kanach at the International Association of Music Libraries (IAML) congress in Prague in 2022. See Delhaye and Kanach, 2022.

3 “Video Presentation of the Exhibition: Xenakis’s Diatope: A Visual Artist’s Perspective by Bruno Rastoin” (2022), Centre Iannis Xenakis, https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/items/show/4982

4 Omeka, https://omeka.org/

5 “Inventaire des archives,” Centre Iannis Xenakis, https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/inventaire_archives

6 Isidore, https://isidore.science/source/10670/2.ofsr4v

7 Varga, 1996, p. 193.

8 Couprie, 2020, p. 437–57.

9 Fleuret, 1971.

10 Xenakis, 1988, p. 105 [Cette Tauriphanie fut une synthèse de mes rêves quant au passé archaïque méditerranéen. Les dieux, Baal, Apis, le Minotaure, Zeus se transformant en taureau pour enlever Europe, mais qui avait grandi avec la percussion assourdissante des Corybantes, les chevaux divins et parlants d’Achille… Bien sûr, des deux cents taureaux espérés, je n’en ai obtenu que 25 ! Un symbole, et encore sans voix ! Mais cette petitesse contemporaine fut corrigée par les quelques juments, venues avec leurs poulains et deux mâles, chez lesquelles beauté des ondulations, craintes et attractions érotiques se mêlaient, et qui, toutes effleurées par la grâce, se croisaient en une perfection inégalée des mouvements ; et ma musique avec cette participation animale devenait alors Nature. Puisqu’à la musique “humaine” des percussionnistes, aux animaux, s’ajoutaient la musique composée sur l’Upic à l’aide d’ordinateurs]. All translations are my own, under the attentive and valuable guidance of Sharon Kanach.

11 “Program Note, 1987 Edition” (1987), Le Nouveau Festival Radio France Occitanie Montpellier,

https://lefestival.eu/les-archives/12 Xenakis and Massin, 1987.

13 “Tauriphanies de Xenakis, à Arles les fils de Minos sont restés muets” (17 July 1987), Le Monde,

https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1987/07/17/tauriphanies-de-xenakis-a-arles-les-fils-de-minos-sont-restes-muets_4050030_1819218.html14 A request for access to the Percussions de Strasbourg archives is underway to determine how the two percussion ensembles present at the event distributed the interpretations of the works, and for any insights on their spatialization within the arena.

15 “Tauriphanies de Xenakis, à Arles les fils de Minos sont restés muets” (17 July 1987), Le Monde,

https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1987/07/17/tauriphanies-de-xenakis-a-arles-les-fils-de-minos-sont-restes-muets_4050030_1819218.html16 Xenakis and Massin, 1987.

17 Delhaye, 2020, p. 173–84.

18 Mâche, 2020, p. 354–77.

19 “Reportage sur les prises de sons de Taurhiphanie” (1987), Centre Iannis Xenakis,

https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/items/show/499020 Ibid.

21 Raczinski, 2001, p. 82–3 [[…] C’est une évolution radicale, tout simplement parce que le résultat est instantané. Mieux, on peut modifier un objet (forme d’onde, enveloppe, etc.) et en entendre l’effet au fur et à mesure de la modification. […] on peut maintenant travailler des pages véritablement complexes, ce qu’on ne faisait pas à cause des temps de calcul des systèmes temps-différé ; on peut aussi utiliser l’UPIC comme un instrument de musique sur lequel on improvise à partir d’un matériau écrit au préalable].

22 Couprie, 2020, p. 439.

23 Harley, 2002, p. 53.

24 Xenakis and Massin, 1987 [Ce qui m’intéresse c’est que je suis libre de mes choix, ma partition me permet des parcours multiples, je peux improviser sur des structures élaborées, et bien entendu mixer à ma convenance les éléments].

25 Although Xenakis’s scepticism about the value of improvisation is widely recognized, Matossian (2005, p. 211–12), his “living biographer” also underlines the “usefulness” of improvisation for the composer: “He liked to work with physical sounds, to familiarise himself with the properties of sonorities, as he did with construction materials. He has retained this preference, often experimenting with instruments before he composes for them.” Ibid., p. 61.

26 Harley, 2002, p. 53

27 “Liste des œuvres composées sur l’UPIC” (1989), Centre Iannis Xenakis,

https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/items/show/498428 “Concert for Flute, Voice and Tape,” Centre Iannis Xenakis, https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/items/show/2927; “UPIC Concert” (1997) Centre Iannis Xenakis,

https://www.centre-iannis-xenakis.org/items/show/6429 MUSICA2, Consortium en musicologie numérique, “Vers une standardisation des métadonnées,” Hypothèses, https://musica.hypotheses.org/metadonnees

30 CIDOC-CRM Conceptual Reference Model, https://cidoc-crm.org/; EARS, ElectroAcoustic Resource Site, http://ears.huma-num.fr/index.html

31 Wilkinson et al., 2016.