16. A Myth of Recurrence in Iannis Xenakis’s La Légende d’Eer

Anton Vishio1

© 2024 Anton Vishio, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.18

De la terre ou de toi, qui a vraiment tourné?

(Abdellatif Laâbi)2

On a recent drive through a relentless downpour, I found my attention riveted to the sound of rain pelting the car. I am not sure how long the experience lasted, but it persisted through several waves as the storm recaptured its peak intensity. Gradually, frustrated by the unending deluge, I tried to mine the complex sound for some recognizable shape, some clue that would indicate the ordeal was nearing an end. And at that point, I thought of Xenakis.

Admittedly, one can imagine somewhat safer moments for such contemplation. But I perceived that the rich, granular sound unfolding around me was not unlike ones I had encountered often in the composer’s work, not only in terms of its “mass effect” but also in its elusive nature; for Richard Barrett, writing about La Légende d’Eer (1977), this nature emerges through a kind of time-dilation, a conflict between time as clocked and time as experienced, time as observed just as one is “forcibly immersed” in it instead of a “safe distance” away.3

Indeed, this forced immersion makes the question of the passage of time in La Légende d’Eer especially compelling—and especially vexing. Barrett finds that the composition lacks “clearly defined points of departure and arrival”; James Harley similarly remarks that “the music proceeds in an extremely continuous fashion,” while Pierre Albert Castanet notes the presence in the “electroacoustic flux” of “a strangely labyrinthine sonorous continuum,” filled with moments that seem to fold back upon themselves to reveal a wealth of sonic layers beneath.4 These perceptions speak to the difficulty of fixing anchors as the work flows through and past us; but for Xenakis these “perceptive reference events” are those things, and “only” those things, through which we “seize the flux of time which passes invisible and impalpable.”5 In his essay “Concerning Time,” the composer develops an “axiomatization of temporal structures” in which separable “points of reference” in the flux of time, “instantaneously hauled up outside of time because of their trace in our memory,” become mental constructs to which we can assign various metrics—”distances, intervals, durations”; these in turn allow us to create, “outside time,” a “geographical map” of the composition.6 The original French terms help to clarify a subtle conceptual journey: the markers we latch on to in the flux are points-repères (points of reference), internalized in our recollection as the more spectral points-traces (vestiges).7

But what if “separability” is not so easily perceived? There are surely phenomena in the work whose clock time we can roughly identify; there is even substantial agreement in the literature on what the most significant of those phenomena are, in the detailed analyses given by the authors already mentioned as well as by Makis Solomos, who provides an especially thick hearing informed by the composer’s late draft.8 But isolating these as landmark points in the fluctuation is another matter. We might instead refer to “phases,” as Solomos does, for instance in describing the “silent phase” after the extended opening section of La Légende d’Eer; “phases” better characterizes the kind of emergence (and decay) encountered in the piece, and explains the fuzziness of its sectional boundaries.9 The different properties of an architecture of phases as opposed to an architecture of points suggest a focus on the deployment of middle-ground shapes, ones which have space to proliferate through the course of longer sections.

The overall form that encases those sections has also been a point of some consensus in the literature on La Légende d’Eer. In particular, there is agreement that the work can be described in a symmetrical fashion, as “roughly circular” (Barrett), “a dramatic arch form” (Solomos), an “immense arch” (Castanet).10 The correspondences between the beginning and ending of the composition, the presence of similar high-pitched, “whistling” sounds in both, suggest strong support for this formal conception. But, at the same time, such a balanced design seems at variance with the internally unsettled character produced by evolving phases; I shall develop a formal model which addresses those phases and their ultimate fate.

Fig. 16.1 The Pinwheel Galaxy (Credit: NASA, ESA, CXC, SSC, and STScl).

Our consideration can begin with this astronomical object, the Pinwheel Galaxy, Messier object 101; Robert P. Kirshner’s description of a supernova within it, as detected in 1970, is the subject of one of the assemblage of texts that Xenakis provided as background for La Légende d’Eer.11 Kirshner’s neutral account of the science of successful prediction of features of supernovas is striking in its orthogonal relationship to the cosmic violence of the event itself. He notes that “The fact that calculations based on models of stars that seem likely to explode agree so well with the observation of stars that actually explode is encouraging.” 12 But that violence in the context of M101, in its vast extent, barely registers; indeed, the supernova in question is at the bottom of the galaxy in Figure 16.1, leaving its elegant spiral untouched.13 In the case of La Légende d’Eer, by contrast, the difference in relative size between internal “phases” and overall shape is much less; we should expect a “supernova” in this more intimate, palpably involute context to be far more disruptive, bending that shape to its will.

The quotation from the Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laâbi (b. 1942) in the epigraph addresses the interconnectedness of the work in another, more playful aspect, via perspective: imagining how the immersive nature noted above reflects how everything around us is fundamentally in motion, whether we perceive it or not.14 In this connection, we might also consider Xenakis’s vision for La Légende d’Eer, as relayed to Dominique Druhen: “I was thinking of someone who would be in the middle of the ocean: All around are the sounding elements, unleashed or not”: i.e. some elements seem to cycle around the observer, some seem to become unmoored, floating off into the distance.15 The ideas then of form as involute, immersive, perspectival, and ultimately provisional, something that can be undermined from within, these are features that ultimately guide what I refer to as the “myth of recurrence” in La Légende d’Eer.

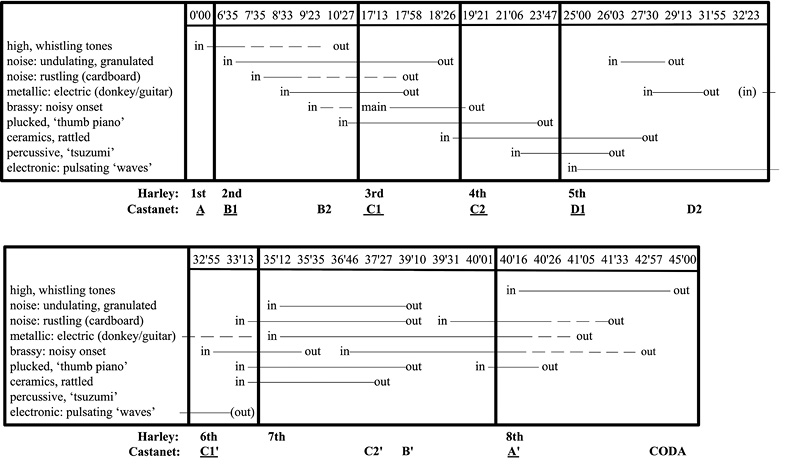

Fig. 16.2 After Harley’s form chart for La Légende d’Eer (with Castanet’s arch). Figure created by author.

Figure 16.2 is based on Harley’s compact picture of the form of La Légende d’Eer, aligned underneath with the sectional labels proposed by Castanet. At least at section beginnings, the two are largely congruent; Castanet’s letters match the beginning of Harley’s divisions in seven of eight sections, underlined on the figure.16 The chart reveals the basis for the suggested frame; the “keystone” of Castanet’s arch, section D, is also the only part of the piece other than the outer sections to be dominated by one sound, the pulsating waves. This is not the only sound stream in Harley’s fifth section, but in its wide-ranging exuberance—the “deafening phase of the cosmogony,” in Solomos’s apt description—it easily crowds out the entrances of other materials.17 And the pulsating waves are limited to this section, just as the A materials are confined to the work’s boundaries. This structural similarity however cannot mask the vast gulf between them: the high whistling sounds in A which minimally saturate their texture against the metallic waves in D which maximally saturate theirs. If this is to be an arch, it is held in place by extreme contrast, as if the A and D sections, strong negatives of each other, keep the composition balanced through the force of their mutual repulsion.

If these framing materials remain aloof, interacting minimally with others, the contents of Castanet’s sections B and C and their reversals are much more gregarious; they are asymmetrically arrayed, gradually layered in moving from A to D and amassed in a volatile jumble in the reverse. It is in these two very different composings-out where the arch seems weakest. The materials of B and C are basically cyclical; they are characterized by reasonably clear onsets, and they are continually, albeit irregularly, renewed, jostling each other for space.

The sound stream whose cyclic procedure is easiest to perceive in these sections is what Harley labels as “brassy, noisy onset” on the fifth line of his chart. Solomos terms this “white noise followed by Brownian motions,” and traces nine appearances of the figure, lasting from eight to twenty-six seconds within a roughly seven-minute period beginning at around 9’30, occurring against the “ground” of what Xenakis designates as “guimbardes africaines,” and the “undulating, granulated” texture that was the first new sound to emerge after the opening section.18 We might describe such multiple, irregularly aligning cyclic threads as “epicyclic,” in a literal sense of “circles upon circles.”19 It seems to me that this is one way in which Xenakis enacts the temporal ambivalence so characteristic of this piece. Within each cycle, there seems to be a more or less conventional “behavior,” i.e., for this phase noise then Brownian motion; each cycle has a perfectly clear trajectory in itself. But the interaction of these separate trajectories amounts to no more than a fluctuating density in the overall shape.

It is undeniable that the sounds at the beginning and the ending of the work—high whistling tones, shooting stars—resemble each other more than they resemble any other materials; but does their resemblance imply a balance between them? There are differences in pitch and timbre, which I will not attempt to detail here; but I was struck more palpably by the difference between the histories of the sounds at the opposite ends of the piece—how the sounds of the opening disappear and how the similar sounds of the ending emerge.

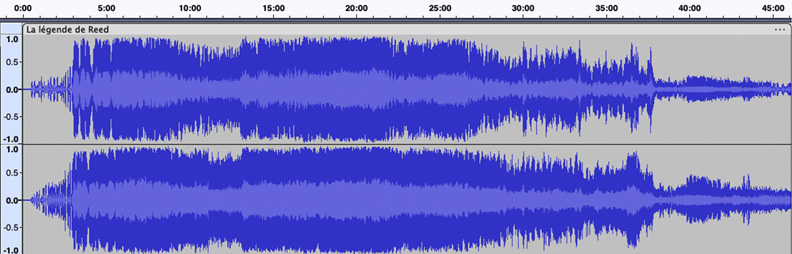

Fig. 16.3 A Doppelgänger of La Légende d’Eer. Figure created by author.

One way I explored the nature of this opposition was to listen to the work backwards, a transformation creating a new piece whose waveform appears as Figure 16.3. Such a maneuver is reminiscent of an article by Edward T. Cone (1917–2004) which criticized then-contemporary analytical writings on the Second Viennese School for being unable to tell the difference between a twelve-tone piece and its mirror image.20 Here instead I was interested in testing formal identity; La Légende de Reed should still retain the arch shape of its progenitor. If anything, though, the reversal more starkly underlines the difference between the two framing A sections. Now the first A section, starting dal niente, gradually grows a continuity, blending into the developing texture rather than staying aloof from it; now the final A section seems to achieve a kind of perpetual steady-state, an uneasy rejection of the intensely restless nature of the piece to that point.21 Meanwhile, this exercise has also clarified for me the differing character of the A sections in their actual order. The first part of La Légende d’Eer stands out as self-contained, an exceptional state within the composition as a whole; while at the ending, the material reminiscent of the opening is merely the “last sound standing,” as if it had never really gone away. The whistling tones are alone not because they push away any sounds, but because the others have just dispersed.

In thinking about the function of different kinds of interfering or incomplete rotations here, I was reminded of the study of rotational form in tonal music that has been spurred by various publications of James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, reaching an important articulation point in their treatise on Sonata Theory. In a terminological appendix, they define rotation as the “recycling” of a “referential thematic pattern established as an ordered succession at the work’s outset.”22 Such a referential object seems exactly like what we would not expect to hear in Xenakis; but Hepokoski and Darcy go on to trace the archetypal nature of the form, and there affinity emerges. After presenting a simple calendrical model of temporal return, they note:

Another, perhaps more sophisticated, metaphor is that of tracking a large spiral through two or more cycles. No set of events that unfolds in nonrecoverable, ever-elapsing time can exist in a condition of complete identity to any [preceding] set […] An essential feature of all such constructions is the tension generated between the blank linearity of non-repeatable time and the quasi-ceremonial circularity of any repeatable events […] inlaid into it. Rotational procedures are grounded in a dialectic of persistent loss […] and the impulse to seek a temporal “return to the origin,” a cyclical renewal and rebeginning.23

Here we might recall how “non-repeatable time” functions in Xenakis’s own musical thought, as the “irreversibility” characteristic of “in time” structures.24 “Outside time,” we are free to imagine the play in the ocean of those sounding elements, which can be set into various relations with each other as we sit surrounded by them, in a “fictitious time….based on memory”; but once we set them in motion “in time,” their order is fixed.25 The “dialectic of persistent loss” is surprisingly close to the dialectic with which Xenakis concludes “Concerning Time”:

The repetition of an event, its reproduction as faithfully as possible, corresponds to [the] struggle against disappearance, against nothingness […] The same principle of dialectical combat is present everywhere, verifiable everywhere. Change—for there is no rest—the couple death and birth lead the Universe, by duplication, the copy more or less conforming. The “more or less” makes the difference between a pendular, cyclic Universe, strictly determined, and a nondetermined Universe, absolutely unpredictable.26

In the case of La Légende d’Eer, it is striking that the materials that rush in to fulfill the aural space once the “origin” has been abandoned have the “quasi-ceremonial” quality referred to by Hepokoski and Darcy, seeking a new foundation that is ultimately unachievable. The end of the composition seems indeed to suggest a “return to the origin”—perhaps, in the spirit of a question of Michel Serres (1930–2019), “an attempt to fight against temporal irreversibility”—but inevitably it falls short, unable to muster the density of material that would permit regeneration.27 No rotation can proceed. Instead, the material drifts away, its sounds dispersed, and then falls silent.

Do other works of Xenakis manifest a similar tension, a feint towards reversibility in the face of its impossibility? It seems to me that Palimpsest (1979) could be approached from a similar perspective. Palimpsest begins with an extended, swirling piano solo, itself continually renewed in density and register; but the function of this opening is puzzling, since it suggests a leading role for the instrument that is only intermittently borne out by the rest of the work. But it turns out it is the material, not the instrument, that is being highlighted; Harley remarks that the work can be heard “as a series of variations on the arborescence entity” that is first unfolded in the piano.28 The opening “state,” like the opening of La Légende d’Eer, represents an unusual condition, a situation of order which Palimpsest tries to reinscribe throughout the piece in the face of “persistent loss.”

Despite Solomos’s warning that the relationship between the thematic texts that Xenakis assembled and the Diatope is complex—“they cannot,” he emphasizes, “be conceived of as [its] argument”29 —and despite the vast range of threads contained in the “cosmic string” with which Xenakis lassoed them together, I close with a brief examination of the ways in which formal ideas explored above, about conflicts between the rotational impulse and time irreversible, emerge in and through them. We have already examined the article by Kirshner; I have italicized key turns of phrase in the remaining texts excerpted below.30

Plato

[…] they saw the ends of the chains of heaven let down from above: for this light is the belt of heaven, and holds together the circle of the universe […] From these ends is extended the spindle of Necessity, on which all the revolutions turn […] The spindle turns on the knees of Necessity; and on the upper surface of each circle is a siren, who goes round with them, hymning a single tone […] round about, at equal intervals, there is another band, three in number, each sitting upon her throne: these are the Fates, daughters of Necessity […] Lachesis singing of the past, Clotho of the present, Atropos of the future…31

Plato describes a threefold rotation about an axis held together by the belt of heaven, whose complex gear work coordinates several epicycles.32

Hermes Trismegistus

9. But the Mind […] begat by Word another Mind Creator. Who being God of the Fire and Spirit, created some Seven Administrators, encompassing in circles the sensible world…

11. But the Creator Mind along with The Word, that encompassing the circles, and making them revolve with force, turned about its own creations and permitted them to be turned about from an indefinite beginning to an interminable end; for they begin ever where they end…

14. And He [i.e. the Man, begat by the Father of all things, the Mind] looked obliquely through the Harmony, breaking through the might of the circles…33

These rotations described in Poemandres are, not surprisingly, far more obscure, but Hermes Trismegistus emphasizes the dangerous creative energy involving the simultaneous projections of the circles that encompass the “sensible world,” producing “irrational animals” as the forced rotations separate out the worlds of air, earth and water; eventually, the creation of the Creator God, Man, discerns the Harmony that allows Him to break through the circles to follow His own creative impulse.

Pascal

[…] let the earth seem to [Man] a dot compared with the vast orbit described by the sun, and let him wonder at the fact that this vast orbit itself is no more than a very small dot compared with that described by the stars in their revolutions around the firmament […] It is an infinite sphere, the centre of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere. 34

Pascal’s orbits in their clarity produce an even more terrifying vision, orbits piled upon orbits upon orbits…

Jean Paul

Upon the dome above there was inscribed the dial of eternity—but figures there were none, and the dial itself was its own gnomon […] And I fell down and peered into the shining mass of worlds, and beheld the coils of the great serpent of eternity all twined about those worlds; these mighty coils began to writhe and rise, and then again they tightened and contracted, folding round the universe twice as closely as before; they wound about all nature in thousandfolds, and crashed the worlds together…35

Finally, the nightmare relayed by Jean Paul, whose central image, the “mighty coils” of the “great serpent of eternity,” seems to prefigure the corde cosmique that Xenakis invokes in yoking together these thematic texts.36 This excerpt is particularly striking for the dream frame that Xenakis omits: the idyllic setting which disintegrates into this nightmare, and then Jean Paul’s waking from the End of Time to a soothing vision, “from all nature round, on every hand, rose music-tones of peace and joy, a rich, soft, gentle harmony, like the sweet chime of bells at evening pealing far away.”37 But as noted above, the end of La Légende d’Eer is not soothing, much less an awakening; indeed, Xenakis’s preoccupation with death in his works of the 1970s can receive ample confirmation in the final trajectory of this piece, quite apart from the content of the programmatic texts themselves.38

But that is an awfully gloomy place to end. There is no recurrence, nor was meant to be; but the world we experienced brought into (and out of) being through La Légende d’Eer was one worth mourning when it departed. Hopefully, like the original Er, we avoided drinking at the river Unmindfulness; and we have our memories to reconstruct and relive that world until we can hear it again.

References

BARRETT, Richard (2002), “Musica instrumentalis of the Merciless Cosmos: La Légende d’Eer,” Contemporary Music Review, vol. 21, no. 2–3, p. 69–83.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2014), “Les humanités sensibles d’un sphinx à l’oreille d’airain: Notes pour une philosophie xenakienne de l’art, de la science, et de la culture,” in Pierre Albert Castanet and Sharon Kanach (eds.), Xenakis et les arts, Rouen, École supérieure d’architecture de Normandie, p. 14–35.

CHAMBERS, John D. ([1882] 1972), The Divine Pymander and Other Writings of Hermes Trismegistus, New York, Samuel Wieser.

CONE, Edward (1967), “Beyond Analysis,” Perspectives of New Music, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 33–51.

DELIO, Thomas (1980), “Iannis Xenakis’ Nomos Alpha: The Dialectics of Structure and Materials,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 63–95.

DRUHEN, Dominique (1995), Liner notes for Auvidis Montaigne MO 782058, Iannis Xenakis: La Légende d’Eer.

FLINT, Ellen Rennie (2001), “The Experience of Time and Psappha,” in Makis Solomos (ed.), Présences de Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Centre de documentation de la musique contemporaine, p. 163–71.

HARLEY, James (2002), “The Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis,” Computer Music Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, p. 33–57.

HARLEY, James (2004), Xenakis: His Life in Music, New York, Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203342794

HARLEY, Maria Anna (1994), “Spatial Sound Movement in the Music of Xenakis,” Journal of New Music Research, vol. 23, no. 3, p. 291–314.

HEPOKOSKI, James and DARCY, Warren (2006), Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late Eighteenth-Century Sonata, New York, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001

HERZFELD-SCHILD, Marie Louise (2014), Antike Wurzeln bei Iannis Xenakis, Stuttgart, Franz Steiner, https://doi.org/10.25162/9783515106894

ILIESCU, Mihu (2015), “La Légende d’Eer à la lumière de son argument littéraire: symbolisme gnostique et morphologies archétypales,” in Makis Solomos (ed.), Iannis Xenakis, La Musique Electroacoustique, Paris, Harmattan, p. 225–40.

JEAN PAUL ([1796–97] 1897), Siebenkäs, translated by Alexander Ewing, London, George Bell and Sons.

KIRSHNER, Robert (1976), “Supernovas in other Galaxies,” Scientific American, vol. 235, no. 6, p. 88–101.

LAÂBI, Abdellatif (2016), In Praise of Defeat: Poems by Abdellatif Laâbi, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Brooklyn, New York, Archipelago Books.

MATOSSIAN, Nouritza (1981), “L’artisan de la nature,” in Hughes Gerhards (ed.), Regards sur Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Stock, p. 44–51.

NAKIPBEKOVA, Alfia (2022), “Nomos alpha by Iannis Xenakis and the Problem of Death and Destiny,” in Anastasia Georgaki and Makis Solomos (eds.), Centenary International Symposium XENAKIS ’22, Athens, Kostarakis, p. 79–88.

PAPE, Gerard (2009), “Xenakis and Time,” in Ralph Paland and Christoph von Blumröder (eds.), Iannis Xenakis: Das elektroakustische Werk, Vienna, Verlag Den Apfel, p. 35–40.

PASCAL, Blaise (1961), Pensées, translated by J. M. Cohen, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

PLATO (1970), The Republic, translated by Benjamin Jowett, New York, Vintage.

SOLOMOS, Makis (2005), Liner notes for Mode DVD 148, Xenakis Electronic Music 1: La Légende d’Eer.

SOLOMOS, Makis (2006), “Le Diatope et La Légende d’Eer de Iannis Xenakis,” in Bruno Bossis, Anne Veitl, and Marc Battier (eds.), Musique, instruments, machines. Autour des musiques électroacoustiques, Paris, Université Paris 4-MINT, p. 161–96.

VANDENBOGAERDE, Fernand (1968), “Analyse de ‘Nomos Alpha’ de I. Xenakis,” Mathématiques et sciences humaines, vol. 27, p. 35–50.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1985), Arts-Sciences, Alloys: The Thesis Defence of Iannis Xenakis before Olivier Messiaen, Michel Ragon, Olivier Revault d’Allonnes, Michel Serres, and Bernard Teyssèdre, translated by Sharon Kanach, Stuyvesant, New York, Pendragon.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1988), “Sur le temps,” in Adolphe Nysenholc and Jean Pierre Boon (eds.), Redécouvrir le temps, Brussels, Revue de l’Université de Bruxelles, p. 193–200.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1989), “Concerning Time,” translated by Roberta Brown, Perspectives of New Music, vol. 27, no. 1, p. 84–92.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1994), Kéleütha: Écrits, with preface and notes by Benoît Gibson, edited by Alain Galliari, Paris, L’Arche.

1 The talk this chapter is based on was originally (mis)titled “Negative Form and La Légende d’Eer;” many thanks to the editors for allowing me to change it for this publication, as well as to James Harley, Yayoi Uno Everett, Nathan Friedman, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments and discussion.

2 Laâbi, 2016, p. 700. Donald Nicholson-Smith translates this as “As between the earth and you, which has actually turned?”

3 Barrett, 2002, p. 77. A better description of being stuck in a relentless downpour would be hard to imagine! Castanet, 2004, p. 22, cites an early observation of Maurice Fleuret (1932–90) about La Légende d’Eer, that it concerned “a rain of comets with a thousand suns.” All translations not otherwise attributed are my own.

4 Barrett, 2002, p. 75; Harley, 2004, p. 112; Castanet, 2014, p. 25. I have slightly truncated the quotation from Castanet [le flux électroacoustique va…abondamment entretenir les flux d’un continuum sonore aux détails poétiques étrangement labyrinthiques].

5 Xenakis, 1989, p. 87; the original French version of this essay appeared as Xenakis, 1988, reprinted in Xenakis, 1994.

6 Xenakis, 1989, p. 89.

7 Xenakis, 1994, p. 102. Elsewhere in the essay (ibid., p.98) he uses, in quick succession, “repères sensibles” (perceptible landmarks), “repères-événements” (landmark events), and “phénomènes-repères” (landmark phenomena), for subtle gradations of similar concepts. Gerard Pape (Pape, 2009, p. 37) has suggested that the same “outside time” structures can lead to a variety of “in time” realizations; one can imagine that the journey of a point of reference from sonic marker to mental “trace” is an important enabler of this variety.

8 Solomos, 2006.

9 Ibid., p. 169. Castanet (Castanet, 2014, p. 28), in his engaging “Petite guide d’écoute” (Brief Listening Guide), speaks of a “phase acoustique” (acoustical phase) in relation to the section labeled as C1 on Figure 16.2 below.

10 Barrett, 2002, p. 76; Solomos, 2006, p. 163; Castanet, 2014, p. 28.

11 Kirshner, 1976. The image of the Pinwheel Galaxy in Figure 16.1 appeared several decades after Kirshner’s article. I shall briefly review the other texts in Xenakis’s assemblage in the last section of this paper.

12 Ibid., p. 93. Xenakis had a choice of supernovas to work with. Kirshner’s article leads not with SN 1970g but with a Type I (now Ia) supernova that was discovered two years later by Charles T. Kowal, designated SN 1972e; Kowal’s photographs of that supernova, taken over a period of eleven months, appear at the outset of Kirshner’s article. But SN 1972e occurs in the “irregular” galaxy NGC 5253, whose shape is much more elusive, a Blue Compact Dwarf galaxy described as “peculiar” at ESA, https://esahubble.org/images/potw1248a/. Did Xenakis choose M101 to emphasize its more striking spiral?

13 “SN 1970G,” Chandra X-ray Observatory Center, https://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2005/sn70/sn70_hand.html

14 Earlier in this poem, entitled “La halte de la confidence” (A Halt to Disclosure), Laâbi writes “Night after night you scrutinize the stars. Their beauty is not the question. Naming them seems trivial. Their great distance from you? A detail. What you want is to establish a link with them, a physical link…” (Laâbi, 2016, p. 693)—lines which resonate beautifully with Xenakis’s admission to Nouritza Matossian, “I want to bring the stars down and move them around. Don’t you have this kind of dream?” (Matossian, 1981, p. 50, as cited in Harley, 2004, p. 114).

15 Druhen, 1995, p. 2 [Quand j’ai composé La Légende d’Eer, je pensais à quelqu’un qui se trouverait au milieu de l’Océan. Tout autour de lui, les éléments qui se déchaînent, ou pas, mais qui l’environnent].

16 Harley, 2002, p. 50; also in Harley, 2004, p. 113. I am most grateful to James Harley for permission to reproduce his chart here. I should also point out that Harley’s discussion of the form is much more agnostic about large-scale shape than the others; indeed, as we shall see, the details Harley provides help to show where the arch model is less successful.

17 Solomos, 2005.

18 Solomos, 2006, p. 172–3 [bruit blanc puis mélodie probabiliste (mouvements browniens)]. Detailing of later occurrences of the sound, interweaved in a more complex sonic environment, can be found in ibid., p. 176–7.

19 To stretch the Ptolemaic metaphor further—perhaps too far!—the “circles” in question could be said to rotate about the “deferent” formed by the larger cycle of the entire composition.

20 Cone, 1967. Cone initially transformed his examples through inversion rather than through retrograde, to avoid various technical issues; but he does eventually entertain the possibility that retrogression would make the same point (p. 36).

21 In fact, the ending is perhaps even more disturbing in the Doppelgänger; it provides a musical parallel to the phenomenon of heat death, its universe reduced to high whistling sounds in perpetuity. Meanwhile, the clarity of the “epicyclic” material is lost; this casts light on the strategy of how that cycle was constructed in the “forwards” version of the piece, beginning with a breath before moving on to extended Brownian motion.

22 Hepokoski and Darcy, 2006, p. 611.

23 Ibid. Hepokoski and Darcy go on to list a number of other uses of “rotation” in music theory that are quite different; we too can note that “rotation” is applied in a number of unrelated contexts in the Xenakis literature, as a group-theoretic operation (for instance, applied to a cube to generate material in Nomos Alpha, as in Vandenboegarde, 1968 or Delio, 1980) or in the varieties of sound movement studied by Maria Anna Harley (M. A. Harley, 1994).

24 Xenakis, 1985, p. 74–5.

25 Ibid., p. 71.

26 Xenakis, 1989, p. 91–2.

27 Xenakis, 1985, p. 73.

28 Harley, 2004, p. 123–4.

29 Solomos, 2006, p. 192: “On ne peut cependant les concevoir comme l’argument du Diatope.”

30 The texts are: Plato, Republic 10: 613c–621d; extracts from Poemandres by Hermes Trismegistus; Pensées by Blaise Pascal (1623–62); and Siebenkäs by Johann Paul Richter, known as Jean Paul (1763–1825). Druhen (1995) supplies the full excerpts used by Xenakis. Editions used for the English translations are provided below.

31 Plato, 1970, p. 391–2.

32 The spindle is a representative of the archetype that Mihu Iliescu identifies as “L’axis mundi” in his exploration of gnostic themes in La Légende d’Eer; the axis was also realized in the Diatope’s central light tower. Iliescu, 2015, p. 230.

33 Pymander, Chambers, [1882] 1972, p. 4–5, 7–8.

34 Pascal, 1961, as cited in Druhen, 1995, p. 21.

35 Jean Paul, [1796–7] 1897, p. 262, 265. In her wide-ranging discussion of the texts, Marie Louise Herzfeld-Schild notes that Xenakis’s English source referred to “rings” rather than “coils”; but his source is unidentified. Herzfeld-Schild, 2014, p. 174–5.

36 Xenakis referred to that “cosmic string” as a “sort of sonorous string pulled tight by mankind, through cosmic space and eternity, a string of ideas, of science, of revelations coiled around it.” Solomos, 2005 (emphasis mine).

37 Jean Paul, [1796–7] 1897, p. 265.

38 Solomos, 2006, p. 193; Harley, 2004, p. 129–33. In her recent essay, Nakipbekova, 2022 provides a broader picture, stretching back to the 1960s.