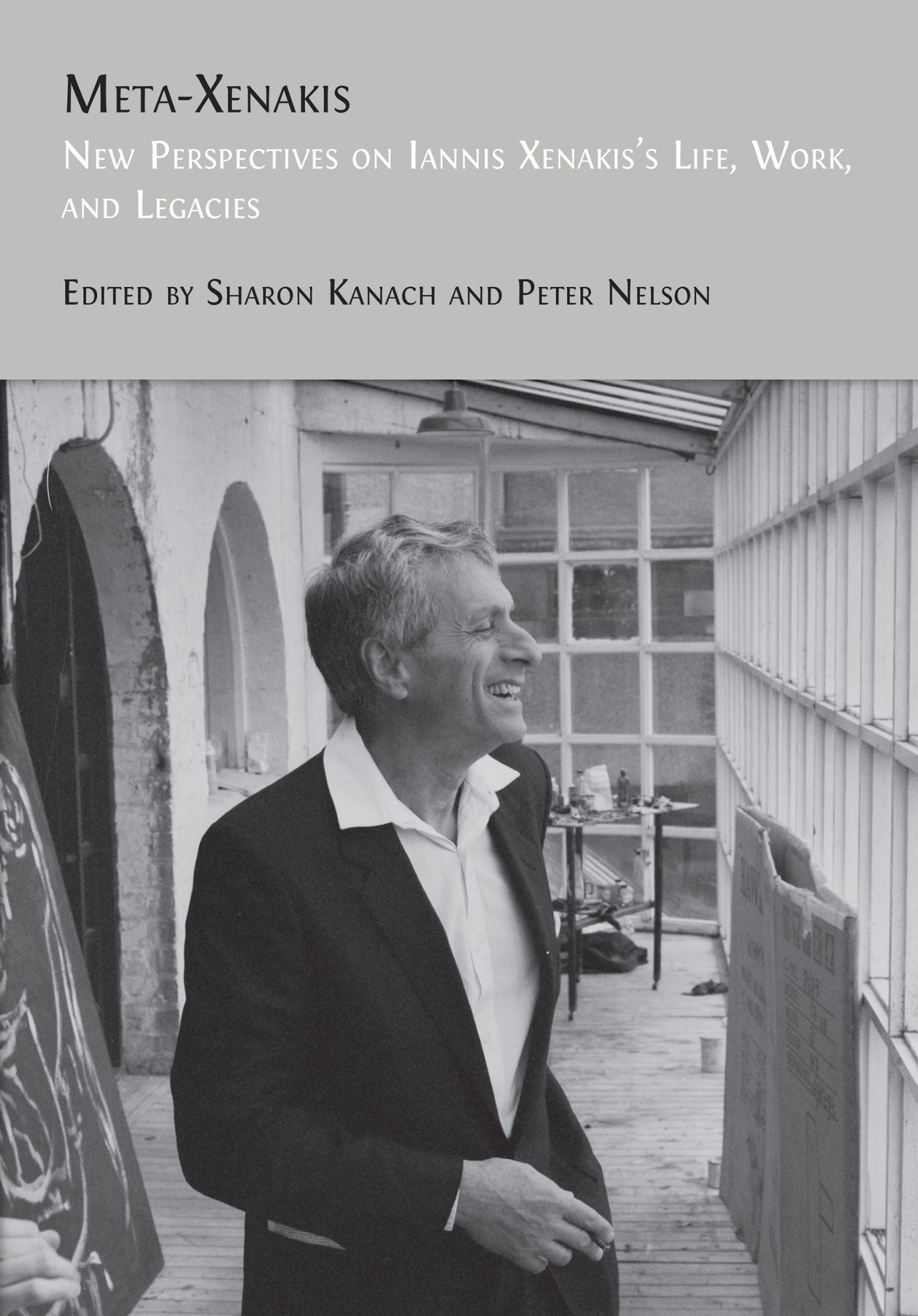

22. Iannis Xenakis/Le Corbusier:

A Confrontation en sol dur

Guy Pimienta

(translated by Sharon Kanach)1

© 2024 Guy Pimienta |(translated by Sharon Kanach), CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.24

A work of art is good if it has arisen out of necessity.

That is the only way one can judge it.

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926)2

Le Corbusier (1887–1965) always knew how to surround himself with extremely competent people. In this respect, Pierre Jeanneret (1896–1967), Charlotte Perriand 1903–99), and Pierre Faucheux (1924–99) were key in establishing his fame. What is not as well-known is how much Iannis Xenakis contributed to Le Corbusier’s last projects. It is under the epigraph above by Rilke that this essay is positioned, as this citation is remarkably applicable to Xenakis. Yes, his music was born from a necessity, which we will call his “inner atelier.” Something is transmuted there as Xenakis invented a non-perspective organization of listening; he listened to the world with a different ear.

The work of Xenakis is characterized by an internal tension, a horizon of expectation whose distinctive features between “fields of experience” and “horizon of expectation” are not yet fully grasped. His thinking is situated between Vitruvius and Aristotle, architecture and philosophy, where questions of place, void, and time are addressed.

What makes architecture strong is proportions: the coherent relationship between the details and the overall work, and even when there are only ruins left, one still realizes perfectly well the power or not of proportions.3

Musician and architect; or rather, musician or architect? It is essential to address the question from both sides. It is in the relationship between these two aspects that Xenakis’s approach is to be found. His originality lies therein, like his interest not in numbers but in the relationship between them. It forms a kind of paradox that isn’t one. His time with Le Corbusier structured him. Very early on, Le Corbusier recognized Xenakis’s ability to shift the boundaries of his own architectural research. It is this “beyond” that Xenakis prepared during the twelve years he spent with Le Corbusier.

This chapter analyzes Xenakis’s trajectory through an examination of the internal organization of Le Corbusier’s studio and its evolution during the 1950s. What was the mutual influence between Le Corbusier and Xenakis, given the often-fractious relationship between engineers and architects? More specifically, I will examine the role played by Le Corbusier’s assistants and the confrontation between music and architecture. On examination, I find that Xenakis brought to light the fact that there was not only a simple exchange between disciplines but that there was a true departure from all disciplinary thinking, and that his œuvre aligned his architectural projects, his musical compositions, and his writings.

Le Corbusier’s Method: A Laboratory of Possibilities

It was Georges Candilis (1913–95)4 who introduced Xenakis to Le Corbusier in 1947 when important commissions were pouring in. Le Corbusier entrusted this new young polytechnician with technical tasks: calculating structures. Le Corbusier’s use of mathematics was rather literary: he resorted to it to legitimize his intuitions and make them acceptable. Xenakis quickly realized that Le Corbusier was a poor builder and that he left it to “his family” (the architects—and engineers—of his atelier) to sort out a certain number of constructive inconsistencies to accommodate his theories. Le Corbusier quickly recognized what Xenakis could do for him.

Something connected the two; they shared the capacity to be penetrated by emotional experiences. Their respective aesthetic stances were rooted in drawing and painting for Le Corbusier and in philosophy and mathematics for Xenakis. They both had a common way of exploring their respective research through the process of memory. The studio at 35 Rue de Sèvres where Xenakis arrived in 1947 was for him a laboratory of possibilities. Xenakis was confronted there with a very singular working method; nevertheless, he observed, he listened, he analyzed. Le Corbusier reminds us:

My young people help me realize my ideas; I am their elder. If they came to me to contribute their work effort, it is because all in all they found these ideas valid. I get my ideas from their working drawings; I fight against their wrong paths; I try to uplift them. I endure the throes of childbirth with them, holding their pencil and eraser in my hand; they witness the birth of a work of architecture.5

In his manner of conceiving projects, Le Corbusier sought to articulate all this collective knowledge into new elements that had both form and meaning through a constant exchange with his employees.

Le Corbusier invited his employees to use their imagination as a complement to his own, to engage in a coerced exchange: he allowed them to make something Le Corbusier as long as the Corbusian doxa was not questioned; an enlightened despotism in which Xenakis never allowed himself to be trapped. Le Corbusier said of him: “Xenakis is of the race of the Greek tragedians, of the pre-Socratics; he is open to Greek art, to Byzantine music and, as an architect, he always has a global vision of things.”6

Xenakis’s command of modern music and mathematics literally fascinated Le Corbusier. During the twelve years he spent in the atelier, Xenakis forged his own tools. In his own way, Xenakis applied the rules of Auguste Dupin in Edgar Allan Poe’s (1809–49) The Purloined Letter (1844): a time to see, a time to understand, a time to act. Architecture became the alloy that allowed him to create the fusion between the arts and sciences and became the theme of his doctorat d’état in 1976, comprised of his entire musical, architectural and theoretical output at that time: Arts/Sciences: Alloys.7 This long process of cognitive development, L’atelier de la recherche patiente (Creation is a Patient Search)8 as Le Corbusier called it, was a foundation for Xenakis’s constant interest in music. He forged his musical destiny with the tools of architecture. Building, on the one hand, and composing on the other, are but the same aspects of the creative act; they both are preoccupied by the unresolved redefinition of space and time. Xenakis overturned tables in search of sound surfaces that would later translate into his polytopes, authentically enveloping spatial structures.

The Inner Atelier: A Vitruvian Dream

It is imperative that an architect has a flair for writing, skill in drawing, knowledge of geometry… he must have a thorough understanding of arithmetic, be well versed in history, have carefully studied philosophy, know music, be familiar with medicine and jurisprudence, as well as the science of astronomy, which introduces us to the movements of the heavens.9

Without their mutual fascination with Greek antiquity, without such an understanding, one cannot address what brought Xenakis and Le Corbusier together: their formative years illuminate what each was to become.

Le Corbusier

During his travels, Le Corbusier drew to capture the essence of what he discovered. His notebooks were his working tools: they served to record, in their raw state, his observations, the images that he would revisit later, or never. He constantly referred to his notebooks, spoke of them often, but rarely revealed them. Drawing for him was his means to understand things, a way to decipher the world. Between 1910 and 1911, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (the future Le Corbusier) embarked on a journey to Constantinople, crossing all of Europe. His account of this journey was to become Le Voyage d’Orient (The Voyage to the East) and was supposed to be published in 1914. It was not. The manuscript was buried deep in Le Corbusier’s archives. He rediscovered it fifty-four years later, and the account was finally published posthumously in 1966, the year after his death.10 What emerges from this narrative is his fascination with the Acropolis. He was overwhelmed by the Parthenon. The nature of the relationships between the buildings is what interested Le Corbusier, as an enigma to be solved, without, however, being able to articulate it.

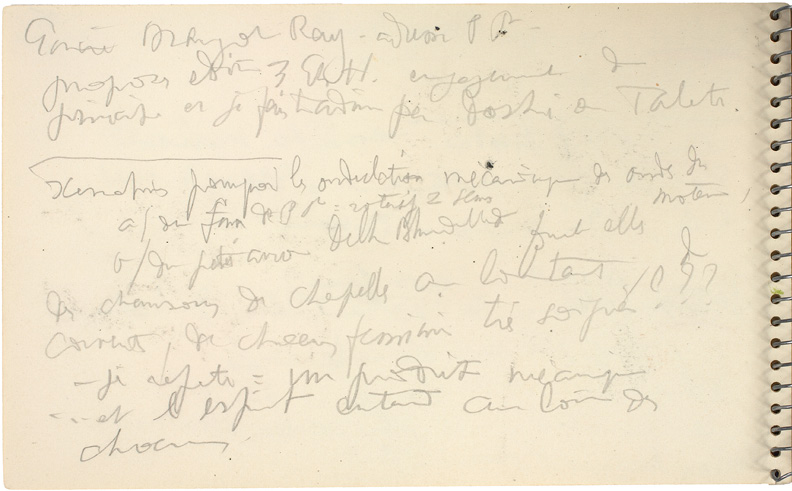

Fig. 22.1 Excerpt from Le Corbusier’s Carnet III, no. 617 (courtesy of Fondation Le Corbusier).

Over the years, his notebooks (which he never abandoned), reflected his secret garden, the place from which his first ideas emerged. His drawings show a stenographic manner of working; they reveal a fundamental relationship between painting and architecture. His notebooks are a collection of analytical annotations, a veritable tool for appropriating and understanding what he sees. Seventy-three notebooks have been found and published in four volumes.11 Quantities of images and notes can be found in these notebooks, which represent Le Corbusier’s memory. They translate, day after day, his experience of the world and tell his own story: multiple sources of references, of jotted down thoughts, representing many layers of his invention. There are thirty instances where the name of Xenakis appears in these four volumes. It becomes very clear that Le Corbusier undeniably relies on him. Let us consider, for example, this one:

[…] Xenakis, why mechanical waves of the engine // a) of PJ’s12 oven = rotating 2 directions // b) of the small airplane Delhi Ahmedabad // do they create songs of a chapel in the distance, of convents, of very refined female choirs?…- I repeat = a mechanical product…and the mind hears choirs in the distance.13

Xenakis

Xenakis’s thought is fundamentally grounded in Greek antiquity. Xenakis was well-versed in the texts of Homer, the Greek philosophers, and Greek tragedy. Before joining Le Corbusier’s studio, Xenakis always claimed to know nothing about modern architecture and asserted that nothing could surpass the Parthenon.

In my youth, I intended to be an archaeologist, undoubtedly because I lived immersed in ancient literature, in the middle of statues and temples… I used to go to Marathon by bicycle. At the supposed place of the battle, there was a tomb with a bas-relief of Aristocles [Plato], and I would stay there for a long time to soak up the sounds of nature, the cicadas, the sea.14

Xenakis’s invention and curiosity were constant, inseparable from who he was. While taking his first lessons in analysis, harmony, and counterpoint, at the age of fifteen, he transcribed a Bach fugue in graphical form in order to “find the structure, the architecture in a visible way.”15

I learned piano with a Swiss teacher, I sang Palestrina, and at the age of sixteen I decided to devote myself to composition. I was also very interested in philosophy and mathematics, but not at all in architecture, which, for me, had ceased to exist in the 5th century B.C.! It was somewhat by chance that I found work with Le Corbusier when I arrived in Paris in 1947. I understood what architecture was through his example, which corresponded to what I wanted to do in music.16

Xenakis engaged in “Le Corbusier’s method” like a laboratory of forms and plastic ideas; he talked about “liturgy” where the master carried out a kind of “secret transmutation” with his disciples. This method became a “sounding board” for him.17

Concomitance of Music: Articulating Orient-Occident

Xenakis secretly composed music in Le Corbusier’s studio whenever he had the opportunity; his manuscript would vanish as soon as the master appeared. Xenakis, while performing his role as an engineer, also composed at home and submitted his musical work to musicians whom he esteemed. This is how he met Olivier Messiaen (1908–92) in 1951 and followed his course at the Conservatoire. Later, Xenakis said of Messiaen: “For the very first time I saw a musician think in a wide and unconventional way. Especially the rhythms he introduced and the way he analyzed Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.”18 In the course of a few years, Xenakis managed to combine music, architecture, and mathematics in order to create a new music made up of sound masses. Metastasis (1953–4) is his most emblematic work of this kind. The role played by Messiaen was fundamental, he supported him unfailingly and encouraged him to continue his musical research:

[…] Finally what he has done, he has used mathematics, he has used architecture, in order to compose and that has given something which is totally inspired, but is completely ”outside.” Which belongs only to him. Which no one else could have done! That has an impact, a force. That is a power.19

Messiaen’s support was what made it possible for Xenakis to combine music and architecture. Such encouragement allowed the young Greek to define himself in relation to architecture while at the same time reinforcing his musical aspirations. He said:

I found that problems in architecture were the same as in music. One thing I learned from architecture which is different from the way musicians work is to consider the overall shape of the composition, the way you see a building or a town. Instead of starting from a detail, like a theme, and building up the whole thing with rules, you have the whole in mind and think about the details and the elements and, of course, the proportions. That was a useful mode of thinking. I was young and I was not formed, so I thought that the best way to attack the problem was from both ends, detail and general.20

However, in his memory, the words of Messiaen from 1951 still resonated: “you are almost thirty, you have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect, and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music.”21

Furthermore, Messiaen often brought Eastern and Asian music to his classes, to which he paid the same analytical attention as to Western music. It is undeniable that this had a determining influence on Xenakis:

[I]n the 1950s, I discovered non-European music: from India, Laos, Vietnam, Java, China and Japan. Suddenly, I found myself in familiar waters. Concurrently, Greece appeared to me in a new light, at the intersection of relics from a very ancient musical heritage.22

And elsewhere:

I was looking to see if studies had been done in older or more primitive societies than ours, such as with Australians, in Africa, or in the Amazon, to see if they conceived of time and space in the same way we do.23

Xenakis sought to transgress the duality of time and space categories by advocating their inseparable nature. The concept of in-between would later crystallize during his trip to Japan with his discovery of ma. The concept of ma is both what separates and what unites; in music, it is silence between two musical phrases. We even find its appearance in his piece Hibiki-Hana-Ma (1969–70)…24

Metastasis/La Tourette Convent: A Turning Point

One day, Xenakis asked Le Corbusier to entrust him with a project in its entirety. It was to be the convent of La Tourette, which illustrated Le Corbusier’s talent for bringing Xenakis’s qualities to the fore.

In 1953–4, while working for Le Corbusier, Xenakis created Metastasis for sixty-one instruments; it was his first music entirely derived from mathematical principles and procedures. For Xenakis, it was a question of implementing a direct relationship between music and architecture, an uncommon combination, but one that was self-evident for him.

We find here perhaps the Gordian knot of the composer/Xenakis corroborated by what he says about the similarities between architecture and music: “I discovered through contact with Le Corbusier that the problems of architecture, as he formulated them, were the same as those I faced in music.”25

Indeed, Xenakis discovered a singular way of conceiving architecture with Le Corbusier, by crossing the borders between disciplines. He found and retained a way of thinking that he implemented in his musical practice. Xenakis only keeps the forms of the intention, in short, “matrices of ideas,” a constant dialectic between analysis and bricolage.26

Le Corbusier is a complex figure in the history of architecture; his career was driven by a double ambition: to build at all costs and to leave his mark on the history of architecture. His architectural production becomes very heterogeneous after the war. Indeed, the projects were designed by architects from all over the world. Le Corbusier sensed what Xenakis could bring him when he offered him the opportunity to work on the La Tourette convent in 1954. With this project, Le Corbusier opened a loophole in his system where he foresaw the ability of Xenakis to put his theories into practice and even to go beyond them. With the convent of La Tourette, Xenakis applied the laws of the Modulor,27 absolute credo at that time for Le Corbusier. He insisted on the fact that the Modulor was a way of regulating the logic of numbers, combinatorics, a way of getting out of the classical workings of academism. During his travels in Greece, Le Corbusier measured the components of buildings to note that the golden section appeared there in a recurrent way. Returning to the roots of ancient Greece legitimized the arrival of the young Greek polytechnician in his studio. The strategy of the Corbusian project is built around a double separation: separation between the formal and constructive project, and separation of the formal project between the sketches of Le Corbusier and the Xenakis’s dimensions. The Modulor, deprived of any inherent logic, took its efficiency from a logic of conviction since the autonomy of the act of creation must be established together with the arbitrary. Xenakis takes the Modulor into his own hands and addresses the question of whether such a system of proportions can also serve as a basis for his musical compositions.

During the conception of the La Tourette convent, Xenakis developed the principle of undulating glass panes.28 Thanks to an observation made by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh regarding a technique of inlaying glass in concrete, Xenakis applied and transposed the Indian glass panels from his musical experience. Le Corbusier coined the term “musical glass panes” because of Xenakis’s rhythmic treatment of them. This invention bears witness to a turning point: Xenakis affirmed himself as an architect and, at the same time, confirmed his becoming a musician. In Le Corbusier’s studio, he articulated the two registers concomitantly: music and architecture. He later admitted that it was through Le Corbusier that he had succeeded in considering architecture from a new angle, convinced that it could be treated in an abstract and not only in a formal way: “Graphics are indispensable; there are things that can be more easily manipulated through drawing. I acquired this experience during the twelve years I dealt with architecture with Le Corbusier.”

One of his colleagues in Le Corbusier’s studio, Fernand Gardien, recalled that Xenakis, when composing and decomposing his undulating glass panes, systematically beat the measure while singing!29

Xenakis later mentioned the internal necessity that unites music and architecture while evoking the convent of La Tourette:

Even if the concrete has aged, that “special something” has remained with the Monastery [sic]of La Tourette that instantaneously makes us under- stand that we are in front of a real work, an architectural work. By the way, it was conceived on the basis of a very classical schema: a simple rectangle. It holds together because, behind it all, there is that special something that creates the inner coherence, an internal necessity. In music as well, it is that inner necessity of sounds, their nature, how they are arranged, their transformations in or outside time, which constitute its “truth.” This is towards what both the architect and the composer must aspire.30

The fact remained that Le Corbusier always wanted more. He would push to the limit all the tasks entrusted to Xenakis, demanding so much that he once wrote to him:

It’s time to move ahead! I have three urgent things to take care of at the same time. Don’t complain! If you can’t handle it, then you are neither an architect nor a leader. But I know you are capable.31

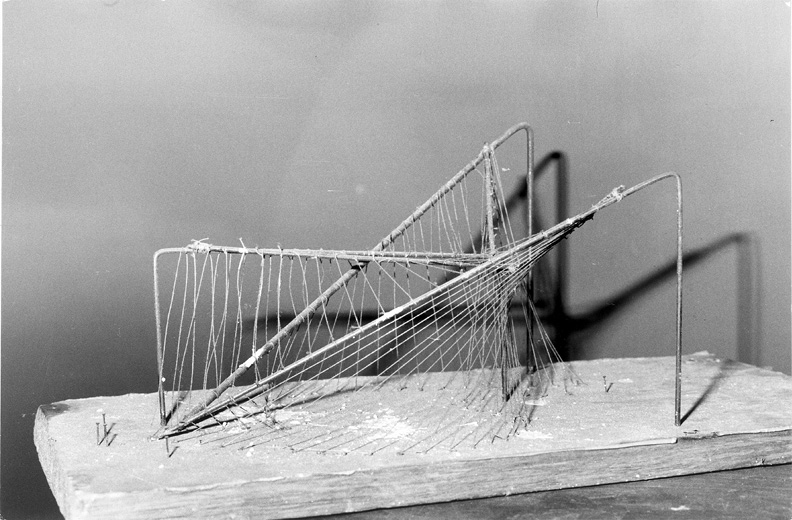

The Places of a Rupture: Denial Considered as one of the Fine Arts

In 1956, Le Corbusier asked Xenakis to design the Philips Pavilion for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, a true contemporary expression of the synthesis of the arts. If with the La Tourette convent, Le Corbusier used Xenakis’s talents to satisfy his aesthetic desires, with the Philips Pavilion, the situation was the opposite. Indeed, with its complex shapes derived from advanced mathematics and new construction techniques, this project evolved in a realm totally unknown to Le Corbusier. Xenakis’s mastery was absolute, and such a situation was unbearable for his boss, who never fully delegated the control of a project. Le Corbusier was torn between his desire to be master of the situation and to be innovative. Le Corbusier’s method was put to test; it turned against him. With the Philips Pavilion, Le Corbusier renounced the credo of his first hypotheses of the right angle. He saw an opportunity to make a 180-degree turnaround. Never had engineers and contractors had to deal with a construction composed exclusively of hyperbolic paraboloids, self-supporting ruled surfaces; Xenakis’s project had no interior nor exterior support components. Xenakis pushed the limits of his favorite material, reinforced concrete, to the extreme. Moreover, he didn’t have any modeling tools other than trial and error. In this respect, one of the first models made of piano strings is one of the most eloquent examples of Xenakis’s experimental research.

Fig. 22.2 Philips Pavilion first Scale model (courtesy of Fondation Le Corbusier).

The Philips Pavilion echoed Xenakis’s musical preoccupations of the time, and mastering such complexity provided him with a solid foundation on which to build his future Polytopes.

In the Philips Pavilion I realized the basic ideas of Metastaseis: as in the music, here too I was interested in the question of whether it is possible to get from one point to another without breaking the continuity. In Metastaseis this problem led to glissandos, while in the pavilion it resulted in the hyperbolic parabola shapes.32

While deeply involved in this project, Le Corbusier initially refused to acknowledge Xenakis’s contribution, not wanting his name to be mentioned. It was a breaking point; their relationship deteriorated increasingly. Xenakis demonstrated with this project that he was much more than an engineer-draftsman, a simple subordinate to a demanding architect. The notes in Le Corbusier’s notebooks prove the importance he placed on Xenakis. In 1957, Xenakis wrote to the director of Philips in disgust:

I now demand, very firmly, that your press services mention my name in the architectural creation of the Pavilion, at the side of Le Corbusier [...] It is the least gesture of justice and truth which Philips owes me for the intellectual and moral qualities which I have placed at its disposal.33

Le Corbusier’s reaction was scathing: “Since 1922, I personally have not personally traced a single line on a drawing board. […] It is a well-known fact that the studio is persuaded that it is he who drives the cart […]”34 How could one not be flabbergasted by such a formula! How can one not be shocked by such contempt? “What exactly do you think you have invented? All these shapes are well known!”35

The Philips Pavilion unleashed something unexpected and troubling in Xenakis. In this project, his mastery was total: he drew, he calculated, he composed, he built, he searched… Le Corbusier’s reaction, writing to the head of Philips indicating that he was the sole creator of the Pavilion, left Xenakis dumbfounded. Even if the name of Xenakis appeared on the Philips Pavilion in fine, the damage was done. Le Corbusier’s jealousy was at its peak; he took advantage of summer vacation to change the locks of the studio and to fire three of his pillars: Iannis Xenakis, Augusto Tobito (1921–2012), André Maisonnier (1923–2016). He called the three of them “date trees” because, according to him, they were enjoying the sun without producing fruit!36

Later, Xenakis said he was deeply disappointed: “I continued to work until 1959 and the situation became absolutely untenable. He came less and less…and then he did something quite disgusting, he used summer vacation to kick me out!”37

When Le Corbusier asked him to return to his studio, Xenakis remained inflexible. He was dejected and offended: “When I decided to do only music, I was very distressed because architecture was very important to me. I did it because I had to make a choice.”38

The Echo Chamber

In a possible anamnesis, we can resurrect how and why Xenakis ended up in Le Corbusier’s studio: the young revolutionary fled Greece because he knew he would be sentenced to death there for his political activities (obviously). He therefore took the chance of receiving the same sentence, but in absentia, wherever he landed. He headed off, destined to the United States, where he had a brother awaiting him.39 But, by the time he arrived in France, during a general strike, he ran out of money, but he was welcomed in Paris by other Greeks in exile and the Communist party. Very soon afterwards he met and was hired (as an engineer, at first, let us not forget) by Le Corbusier. However, he never forgot the demonstrations against the British in Athens in December 1944:

then the fight against the British themselves, in December 44, who had transformed the icy city of Athens into a kind of fantastic polytope both of sound, and of light, with tracer bullets, explosions and all that. They were remarkable polytopes. And afterwards, to organize these masses of events: this is where I say that there is an emergence, because all this came out much later, sweeping away all the preoccupations that I had with polyphonic and harmonic writing, all that I was relearning at the time.40

Indeed, in December of 1944, the street was a vibratory space. This past, he would later transcend it, as he conceded in the same interview: “it comes closer to elsewhere, to the movements of celestial bodies, comets... shooting stars...”41

Xenakis had read Camille Flammarion (1842–1925) and Jules Verne (1828–1905), revealing his taste for the elements and tectonics. He was fascinated by chaos, catastrophes, storms; all those elements that emanate from the uncertain condition of man. How to speak of the earth and speak of mankind? How to make the relationship and the concerns of human beings on earth heard? It was a new consideration of the world, of the ground [sol dur]42 on which he stood.

What does Xenakis make us hear? A disembodied sound, the buzz of an insect, an indistinct sound that man struggles to hear? It is a sound texture that Xenakis offers us, plucked from the universe. Xenakis claimed this inner necessity and made of it a truly different music. To quote Messiaen, Xenakis is “a musician not like the others.”43

What did Xenakis get rid of? Xenakis freed himself from any Western musical legacy. Milan Kundera (1929–2023) explained in his book, Une rencontre, how Xenakis’s music extinguishes sentimentality resulting from the Romantic perception of the world: “And I think of the need, the deep sense of this necessity, which led Xenakis to take the side of the objective sonority of the world against that of the subjectivity of a soul.”44

Xenakis was impregnated with both a method and a way of shaking the foundations of architecture in Le Corbusier’s studio. Modern architecture swept away a repertoire cluttered by the fundamental elements of space: straight lines, plane, right angle. With the advent of the free plan of Le Corbusier, this progress could only serve as a “matrix of ideas” for Xenakis. A complicity united the two men, they unleashed elements of the past, architectural for the first, musical for the second. To establish a filiation between Le Corbusier and Xenakis makes sense only if one considers that the structure of expectation for Xenakis does not develop but unfolds. As sound unfolds in space; sound, that ultimate element that Xenakis appropriated. As Meister Eckhart (ca. 1260–1328) famously stated: “Only the hand that erases can write the true thing.”

Coda

Without Le Corbusier’s firing of Xenakis in 1959, Iannis Xenakis, the musician, would never have revealed himself to the world. Metaphorically, Xenakis was wounded a second time, and he didn’t forget the memory of earlier injuries such as those on his face, which one (and Xenakis shaving every day) could follow with a finger, as they evolved over time. He perfectly mastered the role history attributed to him and that was written on that indelible musical staff.

Le Corbusier’s impulsive sidelining of Xenakis succeeded in bringing the composer to the fore, sidelining a figure the latter, in fact, had never feared. Xenakis’s work momentarily distanced itself from architecture, but in no way did it erase it; rather, it solidified it. Xenakis’s destiny had been, as it were, mortgaged. Its and his true vocation were elsewhere: in the necessity of which Rilke speaks in my epigraph. When Xenakis refused the master’s last offer to reinstate him in his studio; he swept aside the Corbusian table and overturned a cumbersome figure with the certainty that in order to become, he had to open up a topos: the ground on which everything rests, no matter how solid (dur).

References

BRIDOUX-MICHEL, Séverine (ed.) (2018), Le Corbusier, Iannis Xenakis: Un dialogue architecture / musique, Marseille, Imbernon.

BRIDOUX-MICHEL, Séverine (ed.) (2022), Entre les mondes, Iannis Xenakis, Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses universitaires du Septentrion, Series: Esthétique et sciences des arts.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert and KANACH, Sharon (eds.) (2014), Xenakis et les Arts, Rouen, éditions point de vues.

DELALANDE, François (1997), “Il faut être constamment un immigré,” Entretiens avec Xenakis, Paris, Buchet/Chastel.

FERRO, Sergio, SIMONNET, Cyrille, and PRELORENZO, Claude (eds.) (1994), Le Corbusier—Le Couvent de La Tourette, Marseille, Editions Parenthèses.

HELFFER, Claude (1981), “Sur Herma et autres,” in Hugues Gerhards (ed.), Regards sur Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Stock, p. 195–204.

JARRY, Hélène (1992), “Un musician dans sa tour?” L’humanité, 1 December 1992.

LE CORBUSIER (1941), Sur les quatre routes, Paris, Gallimard.

LE CORBUSIER ([1950] 1983), Le Modulor, 2 vols., Paris, L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui.

LE CORBUSIER (1958), Le poème électronique, Paris, Minuit.

LE CORBUSIER ([1960] 2015), L’atelier de la recherche patiente, Lyon, Fage.

LE CORBUSIER ([1966] 1987), Le voyage d’Orient, Marseille, Editions Parenthèses.

LE CORBUSIER (1981), Les carnets de dessins, 4 vols., Herscher et Dessain et Tolra.

LE CORBUSIER (1987), Le Corbusier, une encyclopédie, Paris, Centre Georges-Pompidou.

KANACH Sharon and LOVELACE Carey (dir.) (2010), Iannis Xenakis: Composer, Architect, Visionary, New York, The Drawing Center.

KUNDERA, Milan (2009), Une rencontre, Paris, Gallimard.

MATOSSIAN, Nouritza ([1981] 2005), Iannis Xenakis, Nicosia, Moufflon.

POE, Edgar Allan (1979), La Lettre volée, Paris, Franco Maria Ricci.

QUINTANA GUERRERO, Ingrid (2018), “La colonie latino-américaine dans l’atelier parisien de Le Corbusier”, Les cahiers de la recherché architecturale, no. 2, n.p., https://doi.org/10.4000/craup.525

RÉMY, Claire (1986), “Sons, probabilités, graphismes. Le mélange étonnant de Xenakis,” Micro-systèmes, no. 65, p. 78–82.

RILKE, Rainer Maria ([1929] 2001), Letters to a Young Poet, translated by Stephen Mitchel, Malden, Massachusetts, Burning Man Books.

SOLOMOS, Makis (ed.) (2003), Iannis Xenakis, Gérard Grisey, La métaphore lumineuse, Paris, L’Harmattan.

SOLOMOS, Makis (ed.) (2022), Révolutions Xenakis, Paris, L’œil and Cité de la musique.

STERKEN, Sven (2004), Iannis Xenakis, Ingénieur et Architecte, Ghent, Universiteit Gent.

VARGA, Balint Andras (1996), Conversations with Iannis Xenakis, London, Faber and Faber.

VITRUVE (1965), Les dix livres d’architecture, Paris, André Balland.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1968), Entretien avec Jacques Bourgeois, London, Boosey and Hawkes.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1971), Musique. Architecture, Paris, Casterman.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1979) “Si Dieu existait il serait bricoleur,” Le Monde de la musique, no. 11, p. 92–7 (95).

XENAKIS, Iannis (1985), Arts/sciences, Alloys: The Thesis Defense of Iannis Xenakis before Olivier Messiaen, Michel Ragon, Olivier Revault d’Allonnes, Michel Serres, and Bernard Teyssèdre, translated by Sharon Kanach, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon Press.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1994), Kéleütha: Ecrits, Paris, L’Arche.

XENAKIS, Iannis (2008), Music and Architecture: Architectural Projects, Texts, and Realizations, translated, compiled and presented by Sharon Kanach, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon Press.

1 This chapter was translated in May 2023.

2 Rilke, [1929] 2001, p. 6.

3 Xenakis quoted in Bridoux-Michel, 2022, p. 68.

4 Candilis was a Greek, born in Baku, Azerbaijan on 29 March 1913. Educated as an architect at the Athens Polytechnic (1931–6), Candilis met Le Corbusier during his studies, at Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) IV (1933) in Athens. Following their encounter, Le Corbusier assigned Candilis the leadership of Assemblée de constructeurs pour une rénovation architecturale (ASCORAL) in 1943. In 1945 he joined the office of Le Corbusier, where he became one of his main collaborators. He also became the project architect for the construction of the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (1945–52), the first project on which Xenakis worked for Le Corbusier. Georges Candilis died in Paris on 10 May 1995.

5 Le Corbusier, 1941, p. 164.

6 Le Corbusier, quoted in Helffer, 1981, p. 203.

7 Xenakis, 1985.

8 Le Corbusier, [1960] 2015.

9 Vitruve, 1965, p. 30.

10 Le Corbusier, [1966] 1987.

11 Le Corbusier, 1981.

12 “PJ” = Pierre Jeanneret, Le Corbusier’s cousin and business partner.

13 Le Corbusier, 1981, Carnet III, number 617.

14 Xenakis, 2008, p. 17.

15 Xenakis, 1968, p. 7.

16 Jarry, 1992.

17 Xenakis quoted in Matossian, [1981] 2005, p. 83.

18 Ibid., p. 60.

19 Ibid., p. 20.

20 Xenakis quoted in ibid., p. 81.

21 Messiaen quoted in ibid., p. 59.

22 Xenakis quoted in Xenakis, 2008, p. 21.

23 Xenakis, 1968, p. 34.

24 See further Chapter 17 in this volume.

25 Xenakis quoted in Matossian, [1981] 2005, p. 64.

26 Cf. Xenakis, 1979, p. 95.

27 Cf. Le Corbusier, [1950] 1983.

28 Cf. Xenakis, 2008, Chapters 1.11–13, p. 41–8.

29 Ferro, Simonnet, and Prelorenzo (1994), p. 91, 94.

30 Ibid., p. 5.

31 Xenakis, 2008, p. 84.

32 Xenakis quoted in Varga, 1996, p. 24.

33 Xenakis quoted in Matossian, [1981] 2005, p. 129.

34 Le Corbusier’s letter to Philips quoted in ibid., p. 130.

35 Le Corbusier quoted in Xenakis and Kanach, 2008, p. 101.

36 Quintana Guerrero, 2018, p. 11.

37 Xenakis quoted in Bridoux-Michel, 2022, p. 192.

38 Xenakis, 1985, p. 57.

39 Matossian, [1981] 2005, p. 40_1.

40 Delalande, 1997, p. 111–13.

41 Ibid.

42 The original title (in French) of this essay was “Xenakis/Le Corbusier: une confrontation en sol dur,” which represents a clever play on words and language. Sol = ground, or the note G (or gamma), a fundamental pitch in the Ancient Greek system and which led to the term “gamme” in French (meaning “scale” in English); “dur” in German, means “major” (as in major or minor scales, intervals…) and in French, means “hard,” like a hard surface. (trans. note).

43 Matossian, [1981] 2005, p. 17.

44 Kundera, 2009, p. 98.