3. Iannis Xenakis in Berlin

Marko Slavíček1

© 2024 Marko Slavíček, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.05

Early Berlin-related Engagements

Iannis Xenakis’s first documented experience with Berlin was of an architectural nature and took place in the late 1950s. In this period, Xenakis worked as an engineer at the studio of a notorious modernist architect, Le Corbusier (1887–1965), in Paris. He was engaged in various tasks, both as an engineer and as an architect, which included the development of Unité d’habitation (housing) projects.2 The first realized projects of the series were in Paris and Marseille3 in the 1940s and early 1950s, while others followed in Nantes (1955), Berlin4 (1957), Briey (1963), and Firminy (1965). Although the construction of the Berlin project took place while Xenakis still worked at the studio,5 no indications of his possible participation have (yet) been identified.6

In March 1957, the West Berlin Senate initiated a prestigious international town planning competition to rehabilitate the central urban areas. Berlin was heavily damaged during the Second World War, and several internationally renowned architects participated in the competition.7 Together with two colleagues from Le Corbusier’s office, André Maisonnier (1923–2016) and Augusto Tobito Acevedo (1921–2012), Xenakis created detailed plans for the competition in January 1958. As the entries had to be anonymous, it is difficult to determine precisely which portions of the work were overseen by each draftsman. However, notes in Xenakis’s handwriting on two drawings serve to help us in identifying his contribution. The submission of Le Corbusier’s studio was ultimately eliminated on the grounds that the planned buildings were too high.8

In the same period, Xenakis was not only occupied as an engineer but was also struggling to make a breakthrough as a young composer. Among the most influential persons in his musical development was a Berlin-born conductor, Hermann Scherchen (1891–1966), who was known to actively promote music of contemporary composers. Xenakis met Scherchen in Paris after a rehearsal of Edgard Varèse’s (1883–1965) Déserts (1954) and also visited him in his hotel room the next morning presenting the score of his first mature orchestral work, Metastasis (1953–4). Although Scherchen expressed interest in conducting the piece, it was in the end premiered by an Austrian conductor, Hans Rosbaud (1895–1962) in Donaueschingen. Scherchen did, however, conduct Xenakis’s future works, such as Pithoprakta (1955–6) in 1957, Achorripsis (1956–7) 9 in 1958, and Terretektorh (1965–6) in 1966. The two remained close until Scherchen’s death in 1966.10

Scherchen’s influence on Xenakis was not simply of a practical nature—in terms of mentoring and promoting his music—but also of a theoretical nature. The conductor organized annual conferences at his home in Gravesano, Switzerland, where he invited international experts to discuss contemporary music, electronic music, and audio and sound engineering.11 In addition, from 1955 to 1966, Scherchen published a series of reviews titled Gravesaner Blätter (Gravesano Review), which covered the conferences’ activities. He also invited Xenakis to participate at the conferences, thus encouraging him to formulate and articulate his ideas in writing.12 In Gravesano, Xenakis had an opportunity to meet important figures in the sphere of the theory of information and its adaptation to the realm of aesthetics and music, such as Werner Meyer-Eppler (1913–60) and Abraham Moles (1920–92).13 In the ninth issue of the Review, in 1957, even Le Corbusier contributed with a text on his Modulor system.14 Throughout the period of eleven years, Xenakis wrote twelve texts for the Review. Many of these writings were later used in his first book Musiques formelles (Formalized Music), first published in October 1963.15 Xenakis’s texts include: “The Crisis of Serial Music” (No. 1, 1955), “Probability Theory and Music” (No. 6, 1956), “Le Corbusier’s ‘Electronic Poem’” (No. 9, 1957), “In Search of a Stochastic Music” (Nos. 11–12, 1958), “Elements of Stochastic Music” (No. 18, 1960), “Elements of Stochastic Music (II)” (Nos. 19–20, 1960), “Elements of Stochastic Music (III)” (No. 21, 1961), “Elements of Stochastic Music (IV)” (No. 22, 1961), “Stochastic Music” (No. 23–4, 1962), “Free Stochastic Music from the Computer” (No. 26, 1965), “Concerning Le Corbusier” (Nos. 27–8, 1966), and “Towards a Philosophy of Music” (No. 29, 1966).16

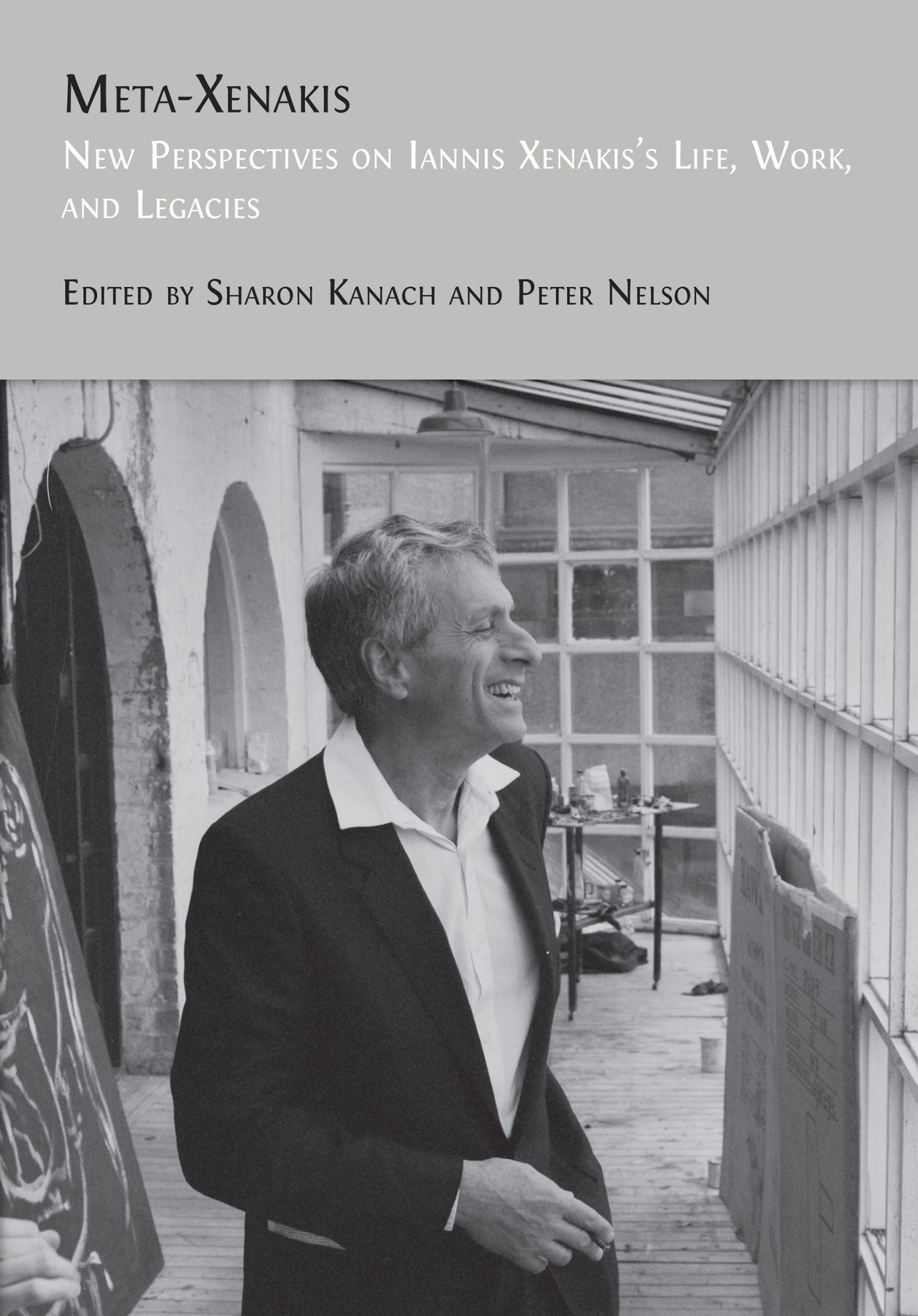

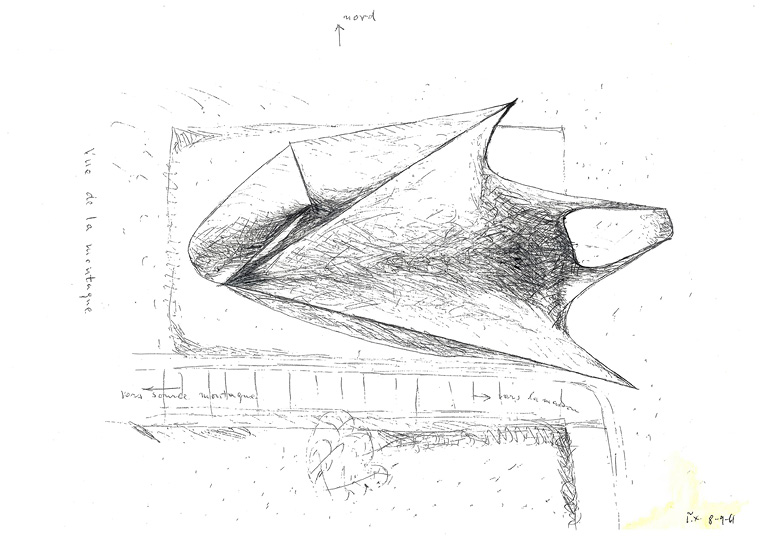

Scherchen wanted to establish an international music center in Gravesano and had plans to build a studio there. To motivate Xenakis to pursue architecture alongside his musical endeavors, Scherchen asked him to design the auditorium. Although Xenakis began work on the project, it was abandoned after the conductor’s death (Figs. 3.1–2).17 It also appears that the two men considered compiling Xenakis’s Gravesano writings and publishing them under the title Mécanisme d’une musique (Mechanism of Music). Xenakis enthusiastically wrote a prologue for the text, but the edition was never published.18 In September 2017, the archives of the Berlin Academy of Arts (Akademie der Künste, or AdK) digitized all twenty-nine volumes of Gravesaner Blätter and made them accessible online.19

Alongside his music activities, Scherchen also showed interest in sound reproduction. As stereophony was not yet popular during this period, he wanted to improve music transmission and give it the sort of spatial sound effect one would otherwise experience in a concert hall. To simulate sound reflection from various locations, the conductor experimented with a spectrophone20—a rotating device that aimed to provide an immediate surround sound. Scherchen’s innovation was to rotate the device simultaneously around the vertical and horizontal axes, an idea which he patented. The patent consisted of a tripod with a diameter of 1.5 meters with a central spherical part hosting thirty-two loudspeakers.21 Due to the periodically varying positions of the system, one could experience a subjective sound localization and a Doppler effect. If lights were to be placed on the sphere, the rotating system would create a corresponding visual effect of Lissajous curves.

Figs. 3.1–2 Two of Xenakis’s sketches for the Hermann’s Scherchen’s Auditorium in Gravesano, Switzerland: top view and perspective. © By kind permission of Archiv der Akademie der

Künste Berlin.

In 1963, together with German scenographer Hans-Ulrich Schmückle (1916–93), Scherchen created the sound film recording Achorripsis, named after the eponymous piece by Xenakis that Scherchen premiered in 1958 in Buenos Aires. The five-minute film–the duration of which corresponds to that of the composition–was an experimental sound-and-light study of Scherchen’s new sound system. Despite all efforts and hopes for future development, the innovation did not achieve commercial success. However, the film was later restored and presented in Berlin in 2011 (Färber 2021).22

The Berlin Residency (1963–4)

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Xenakis began to be recognized as a composer. In 1957, a Russian-born American composer Nicolas Nabokov (1903–78) serving as a Secretary-General of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), supported the young Xenakis by encouraging the European Foundation for Culture to give an award to his piece Metastasis.23 In April 1961, he invited Xenakis to attend the Tokyo East-West Music Encounter. And Nabokov was not the only supporter. Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt (1901–88), a German composer and musicologist who worked at the influential Berlin newspaper Der Tagesspiegel and later as a professor at the Music Department of the Technical University of Berlin, invited Xenakis to Germany to give a lecture on his music. It was to be part of the series of lectures and broadcasts organized by Stuckenschmidt in 1962 and 1963, with many famous names contributing.24 The events were transmitted live by Sender Freies Berlin (SFB) broadcasting company. Xenakis’s lecture, with the title “Formalization and Axiomatization of Musical Compositions,” took place on February 18, 1962, at the Berlin Congress Hall in the Tiergarten district.25 Xenakis touched on many topics which he had already discussed in Gravesano, such as the formalization of stochastic music as an alternative to serialism. He also presented several of his musical compositions as examples of his theories, primarily Metastasis and Pithoprakta, but discussed his architectural experience as well. Between February 19 and 27, 1963, a number of reviews of Xenakis’s lecture were published, namely by Der Abend, Der Kurier, Berliner Morgenpost, Der Tag, Der Tagesspiegel, Telegraf, Die Welt, Berliner Zeitung, and Westfalen-Blatt.26 Only two weeks after the lecture at the Congress Hall, Xenakis would be invited to the city again. This time it was to take part in the Ford Foundation’s27 artist-in-residence program. Before this would take place, Xenakis would spend a summer teaching at the Tanglewood Music Center in Massachusetts, following an invitation by renowned American composer Aaron Copland (1900–90). In September 1963, after the Tanglewood summer course and some time spent in New York, Xenakis moved to Berlin.28 In a letter to Scherchen dated 2 October 1963, Xenakis writes that he arrived in the city three days ago.29

After many years engaged as an engineer, Xenakis finally had an opportunity to be financially secure working exclusively on his music. The program in question, partially funded by the Ford Foundation and partially funded by the West Berlin Senate, aimed to be given to artists of international status with the hope that they would work and reside in a post-war, isolated enclave.30 A French historian, Indologist, and musicologist, Alain Daniélou (1907–94), participated in the same program.31 A German-American pianist and radio presenter, Karl Haas (1913–2005), was included in the program organization and stood at Xenakis’s disposal.32 Between 13 August and 4 September 1964, during the New York City Ballet’s performance at the Berlin Festival Weeks, Xenakis may have also met the influential Georgian-American ballet choreographer George Balanchine (1904–83) for the first time. Balanchine would later choreograph Xenakis’s Metastasis and Pithoprakta in New York, in 1968.33 Among composers whom Xenakis had an opportunity to meet in Berlin were John Cage34 (1912–92) and Joel Chadabe (1938–2021). The latter remained a close friend of Xenakis and was a promoter of his music, publishing the first CD of his electronic works.35 Despite the ideal working conditions, Xenakis lived in Berlin in extreme isolation and did not enjoy his stay. He invited his wife Françoise to join him, along with their daughter Mâkhi, to help him endure the time.36 The family was accommodated in a large house in the Grunewald district of West Berlin (Fig. 3.3).37 The daughter attended the French school for a year. Xenakis described the new environment in a letter to Françoise, dated 2 October 1963:

I am writing to you in my presidential armchair in this miniature Marienbad. Three times the area of our flat, eight rooms, ceiling four meters high, large windows with a view over the lake, bathroom, cupboards everywhere. But what am I to do in this colossal place all by myself? A kind of glass-casement overhangs the park and the lake below this facade is to the south. It is scandalous. No telephone, but soon no doubt. It is very peaceful, and the silence is deafening. When I walk through the rooms at night, I feel phantasmal shadows brushing lightly, ghostlike.38

Françoise, too, expressed a similar sentiment of isolation in an interview from January 1981:

The local people resented the artists being coddled in their midst. “Why don’t you take your money and spend it elsewhere?”, they said. If one spoke French, it was impossible to get a seat on the bus. I preferred not to meet the Berliners as they walked through the Grunewald at night with their huge Alsatians off the lead. I once narrowly escaped being devoured by one. I was wearing a white sheepskin coat, and it was exactly that, a wolfhound trained to catch sheep. In short, none of the past was forgotten, either by them or by myself. We stayed at home and worked a lot. I wrote Des dimanches et des dimanches. Occasionally we met other foreign artists but with the city there was little real contact.39

Fig. 3.3 The house in Grunewald district of Berlin where Xenakis family was accommodated.

© Photo by Marko Slavíček, 21 January 2023.

Since 1965, the artist-in-residence program has been run by DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) [German Academic Exchange Service], the largest German academic support organization. In 2020, the DAAD digitized archive materials from the period 1963–78.40 The Xenakis folder contains seventy-six scanned pages of personal correspondences and related materials dating from 1962 to 2011. The folder includes twenty-one scanned letters in total. Ten letters from March to August 1963 constitute the correspondence between Xenakis and Moritz von Bomhard (1908–66), Consultant of the Ford Foundation. Within the correspondence, two additional letters are enclosed: one from Xenakis to Igor B. Maslowski (1914–99) of the Philips company, dated 11 December 1962, and one from Xenakis to Prof. Dr. Ing. Fritz Winckel (1907–2000) of the Technical University of Berlin, dated 22 May 1963. Eight letters from October 1964 and November 1965 between Xenakis and Peter Nestler (1929–2022), the Head of the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program, are also available. An additional enclosed letter was sent by Xenakis to Dr. Wolfgang Gert Stresemann (1904–98), Intendant of the Berlin Philharmonic, on 3 July 1965.41

The official invitation to Xenakis was sent by von Bomhard on 3 March 1963. In the letter, we find that Nabokov was a mediator in this arrangement and that Mr. Shepard Stone, Director of International Affairs at the Ford Foundation, announced in a press conference that the foundation planned to spend eight million German marks (Deutsche Mark, or DM) on the program. If the invited artists should want to continue to teach their students, they too would be welcome in Berlin, for which they would receive a scholarship. Xenakis was offered fifteen thousand dollars and housing free of charge for the year. In further correspondence with von Bomhard, Xenakis expressed a desire to work with Winckel42 at the electronic studio of the Technical University of Berlin.43 Xenakis recommended three of his colleagues/students to join him in Germany: Japanese composer and pianist Yuji Takahashi (b. 1938), French composer François-Bernard Mâche (b. 1935), and Polish musicologist and composer Józef Patkowski (1929–2005).44 Of the three, Mâche and Patkowski were not able to join the program for personal reasons.45 Takahashi received a yearly scholarship of 2,100 dollars plus travel costs, while he needed to take care of the housing himself. Xenakis also asked for the Foundation to provide funds for Winckel but was denied.46

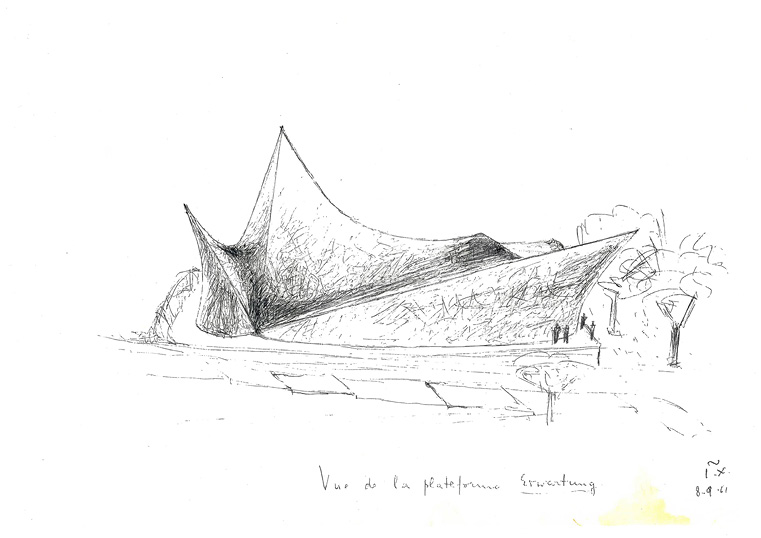

In the correspondence with Peter Nestler in 1965, Xenakis praised his student Takahashi and recommended his scholarship to be extended for at least one more year (Fig. 3.4).47 Xenakis’s willingness to help the young musician is evident in the following passage:

I am anxious about his [Takahashi’s] future. […] [But] although [these] concerts are paid [to him], this money is certainly not sufficient for him and his family. [...] I can certainly affirm again my admiration for him as a pianist and in general as a musician. I think that the European possibilities will bring him to a high standard, one of the highest in the world. Much more safely than in Japan. I know that you agree with me and that your human qualities make you completely understand these considerations in my will to help this extraordinary man and give him the smallest opportunity to achieve himself. Unfortunately, there is no policy of helping young talents in France such as it is developed in Germany or in the USA, this is why I am addressing my request to you.48

Fig. 3.4 A letter from Xenakis to Peter Nestler, dated 4 January 1965. © By kind permission of Archiv Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD.

Ford Foundation agreed to Takahashi’s prolongation to the end of June 1966.49 Xenakis also recommended a young French composer, Francis Miroglio (1924–2005), the director of the summer festival in Saint-Paul de Vence.50 Norddeutscher Rundfunk (Northern German Broadcasting, or NDR) released a four-minute report on Xenakis, titled Stipendiaten der Ford Foundation: Iannis Xenakis (Scholarship Holders of the Ford Foundation: Iannis Xenakis), dated 30 April 1964. In the footage, the young Xenakis is seen crossing the road at Ernst-Reuter-Platz in the Charlottenburg district, entering the IBM building, and using the computers. He also gave a brief statement in German about his music.51

In the summer of 1965, Xenakis complained to Nestler and Stresemann that the German-American conductor Lukas Foss (1922–2009) had withdrawn his Pithoprakta from the concert scheduled to be performed in Berlin by the Berlin Philharmonic on 21 June 1965. At the time, Xenakis was not able to attend the performance, as he was visiting the rehearsals of the National Orchestra of France for the recording of the same piece. He found out about the withdrawal three days before the performance and objected to Foss’s arguments of the composition being unplayable by listing twelve successful performances since the premiere in Munich on 7 March 1957.52

Theoretical Work in Berlin

By the time Xenakis moved to Germany, his first book was ready to be published. In October 1963, under the title Musiques formelles: nouveaux principes formels de composition musicale (Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition), it was released as a double special issue of the French music periodical La Revue Musicale.53 The first edition contained six chapters on various aspects of stochastic music. The future editions included extensions and additional chapters, some of which covered the techniques first developed during the Berlin residency.

The most notable Berlin discovery is the application of mathematical sieve theory in music. Xenakis primarily used the theory to construct musical scales, although the rhythmical sieves soon proved to be just as useful.54 The prototypical example of sieves in mathematics is known as the Sieve of Eratosthenes (?–194 BCE), named after an ancient Greek polymath from Cyrene. It was used for finding all prime numbers up to a given limit. This technique happened to be crucial for Xenakis, as it provided him with a method of “filtering” elements in order to create and manipulate structure.55 On one of his calculations made in pencil, Xenakis specifically notated in his native Greek in red ink: “Hurray! Eureka!” and “Berlin 28/6/64, 5 pm.” He would later formulate and present the theory in essays such as “Towards a Metamusic” of 1967, which he included in Musique. Architecture and the 1992 edition of Formalized Music.56 The manuscript of ‘Towards a Metamusic’ dates from 1965 and was originally titled ‘Harmoniques (Structures hors-temps)’.57 The text examines Pythagoras (ca. 570–ca. 500/490 BCE) and Aristoxenus (ca. 375–ca. 360 BCE), another of Xenakis’s Greek precedents he seemed to have occupied himself with during the residency. With this study, he was able to formulate and clarify his tripartite notion of musical structure: outside time, temporal, and inside time. This was also the first time Xenakis summoned the history of music by showing deep interest in the tonal structures of Antiquity and Byzantine music.58

Three other essays are the result of Xenakis’s Berlin residency, too. These are “Intuition or Rationalism in the Techniques of Contemporary Musical Composition,”59 “La voie de la recherche et de la question” (The Way of Research and Questioning),60 and the first version of “Towards a Philosophy of Music.” The last one was published in Gravesaner Blätter in 1966 (which happened to be Xenakis’s final contribution to the magazine) and was later republished in Musique. Architecture and Formalized Music. All three essays cover the contemporary importance of the pre-Socratic philosophers Pythagoras and Parmenides (ca. late sixth to fifth century BCE), the group structure of sound characteristics (such as pitch, intensity, and duration), and the axiomatic development of those characteristics.61 Together with “Towards a Metamusic,” “Towards a Philosophy of Music” would also be included in Musique. Architecture and Formalized Music.

The Berlin residency gave birth to another notable Xenakis essay, this time architecture-related: ‘La ville cosmique’ (The Cosmic City). It was originally published by Françoise Choay (b. 1925) in her 1965 anthology L’Urbanisme, Utopies et Réalités, and later reprinted in Musique. Architecture.62 In the text, Xenakis is preoccupied with the utopian proposal of an ideal city. This was his take on the concept that can be traced to the urban planning of the Renaissance and to the theoretical writings of Plato (428/427–348/347 BCE).63 Many architects before his time were driven to design a city from scratch using their own formal, functional, and philosophical objective. Notable examples include a fifteenth-century polymath Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) and Xenakis’s former employer, Le Corbusier.64 Xenakis’s proposal stands apart by shifting the focus from planar urban design to the vertical, permeated by a strong belief in technology.65 He pushed the verticality to extremes and imagined parabolic skyscrapers up to several kilometers in height. Led by his engineering experience, Xenakis understood the quality of geometrically and topologically complex algebraic surfaces with which one could produce such large resilient structures.66 In only one of the skyscrapers, it would be possible to fit the entire population of Paris, leaving the surrounding areas free. The aim of Xenakis’s proposal was not only the freeing of the space of the Earth but also decentralization and the avoidance of the city’s orthogonality. In Musique. Architecture, he published a drawing of the Cosmic City to illustrate its scale.67

Xenakis would repeat his 1963 Berlin lecture in 1964 and publish it in his 1971 book Musique. Architecture.68 The lecture titled “Mathematical Formulation of Musical Composition,” dated 3 June 1964, took place in the Amerika Haus Berlin at Hardenbergstraße 22–4. The flyer included the following description:

An attempt to use the universal language of modern thought in musical composition, such as the mathematical theory of probability, or theoretical logic, and of operational research. With the assistance of Yuji Takahashi, pianist, and musical illustrations on tape.69

From the same flyer, we find that the first Berlin performance of Xenakis’s string quartet ST/4-1,080262 (1956–62) took place shortly before the lecture, and was performed by the Parrenin Quartet.70

Musical Work in Berlin

Although the Berlin period was primarily significant for Xenakis because of his theoretical research and was not the most productive one in terms of completed scores, he did manage to occupy himself with a few compositions at the time. The pieces that were composed during the residency, at least partially if not in their entirety, include Eonta (1963), Akrata (1964), and Hiketides: Les Suppliantes d’Eschyle (1964).71 Eonta is scored for piano, two trumpets, and three tenor trombones. Akrata is scored for an ensemble of sixteen wind instruments, consisting of eight woodwinds (piccolo flute, oboe, E-flat piccolo clarinet, B-flat bass clarinet, B-flat contrabass clarinet, bassoon, two double bassoons) and eight brass instruments (two horns, three trumpets, two tenor trombones, and tuba). Hiketides is scored for two trumpets, two trombones, and strings (6.6.0.8.4 or multiples).72 A common denominator of all three pieces is the prominent use of brass instruments, be it in combination with piano, woodwinds, or strings.

The first written notes for Eonta date to summer 1963, when Xenakis was still in Tanglewood, but the piece was finalized in Berlin. It was commissioned by the Ensemble du Domaine Musical and the premiere was conducted by the composer Pierre Boulez (1925–2016). The title is a tribute to the philosopher Parmenides and can be translated as “being(s),” which is a present participle verb and a noun in plural form. In Eonta, Xenakis uses symbolic logic and stochastic principles to generate musical materials. The piece is characterized by spatial positioning of the instrumentalists: the brass players are directed to perform at different locations on the stage, to walk around the stage, to direct the bells of their instruments in various directions, and to blow directly into the open body of the piano. The spatial gestures were meant to exploit the acoustics of the performance space; however, Boulez objected to these gestures, deeming the piece impossible to play as written. His criticism turned out to be unnecessary, as Eonta is regularly performed as intended and remains one of the most successful of Xenakis’s works.73 The premiere took place in December 1964 in Paris. Some of the instrumental parts were calculated on an IBM 7090 computer at the Place Vendôme in Paris.74

Unlike Eonta, which exploits techniques Xenakis had developed until this point in his career, Akrata is the true result of his Berlin residency. Commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation, it was completed in 1965 and premiered in June 1966 at the English Bach Festival in Oxford. It is also stylistically different from the virtuosic Eonta, as it restricts the material to held or repeated tones. The music proceeds as a series of sounds separated by silences. According to Xenakis, Akrata is based on the theory of groups of transformations and the theory of sieves. These theories Xenakis discussed in detail in the essay “Towards a Philosophy of Music”—included in Musique. Architecture and Formalized Music—but in reference to his 1966 piece Nomos Alpha for violoncello, rather than Akrata.75

After Xenakis’s piano quartet Morsima-Amorsima premiered in Athens in December 1962, it received the Manos Hadjidakis Prize.76 The prize resulted in a commission to compose incidental music for a 1964 production of Aeschylus’s tragedy Hiketides (The Suppliants) at the ancient theater in Epidaurus. It was Xenakis’s first work intended for the dramatic stage. The original musical setting was intended for chorus and ensemble, but a more popular instrumental suite based upon the original material was scored for brass and string instruments, in which the brass material is drawn from the choral part. As Xenakis was inspired by the music of Antiquity, Hiketides does not resemble his typical modernist style. Despite not becoming a standard part of his repertoire, it represents the beginning of an exploration of ancient Greek theater in future stage projects like Oresteia (1965–6) and The Bacchae (1993), as well as multimedia spectacles Polytope de Persépolis (1971) and Polytope de Mycènes (1978).77 The premiere took place in July 1964. In a letter from Xenakis to George Balanchine dated 10 October 1964, we find out that Xenakis had left Berlin.78

Later Connections to Berlin

More than a decade after the residency, Xenakis received a prestigious commission from the Berlin Philharmonic. The unusual instrumentation for twelve violoncellos was to be performed by the orchestral players without a conductor. The result was the piece titled Retours-Windungen (1976) with circularly positioned instrumentalists located in front of the audience. The piece premiered on February 20, 1976, in Bonn. Two years before that, the city of Bonn would host a Xenakis festival, and the next year, 1977, they would award Xenakis a Beethoven Prize for his orchestral piece, Erikhton (1974).79

Between 30 March and 2 April 1982, a four-day event titled Inventionen’82 took place in Berlin.80 It was organized by Ingrid Beirer and Helga Retzer of DAAD, professor Folkmar Hein (b. 1944) of the Technical University of Berlin, and composer Sukhi Kang (1934–2020). The series of four concerts was the result of the collaboration between DAAD, the Technical University, and the Academy of Arts. On 31 March, three electronic pieces by Xenakis were performed at the exhibition hall of the Academy of Arts: Bohor (1962), Légende d’Eer (1977), and Mycènes Alpha (1978).81 On the same evening, Xenakis was invited to give a talk on the research institute he had established in 1972, CEMAMu (Centre d’Etudes de Mathématique et Automatique Musicales), as well as on his own computer music. The audio of the talk is archived at the Electronic Studio of the Technical University under the title Xenakis_speech mit telcom.82 In the ten-minute recording, Xenakis discusses the UPIC system, which was created at the CEMAMu as a drawing compositional tool. It was first used in Mycénes Alpha (1978) and premiered at the ancient site of Mycenae in Greece. The piece was also performed in Berlin on 8 September 1988, the year when the city was designated the cultural capital of Europe. For this occasion, Folkmar Hein invited Xenakis’s UPIC system to be presented at the Technical University.83 Apart from the concert with an exhibited graphic score, the event included workshops.84

The last musical work Xenakis created for the performance in Berlin was Roáï (1991), scored for an orchestra of ninety musicians. The title means “fluxes” in ancient Greek dialect, but it can be taken as indicative of various ideas, such as flow, current, transfer, or fusion. In this piece, Xenakis uses the sieve technique he designed almost three decades previously in Berlin. Under the baton of Olaf Henzold (b. 1960), Roáï was premiered on 24 March 1992, by Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. The concert marked the fortieth anniversary of the European Festivals Association.85 Although Xenakis was approaching seventy years of age and was suffering from ill health, with five large orchestral scores produced within a single year, this period turned out to be the last great burst of his compositional activity.86

Xenakis’s last documented visit to Berlin was in autumn 1994. Initiated by the conductor Guillermo Tuchsznaider, the society Berliner Dirigentenwerkstatt e.V. organized their second Berlin Conductor’s Workshop. Between 30 September and 8 October, the event focused on the composer-conductor relationship using works by Xenakis. The workshop, which took place at Centre Culturel Français (French Cultural Centre) and Academy of Arts, consisted of rehearsals and a final concert with introductory talks. Alongside Tuchsznaider’s direction, the workshop featured Silvia Malbrán teaching rhythmic comprehension and rhythmic-physical perception, Rudolf Frisius (b. 1941) analyzing Xenakis’s work, and Heinz Klaus Metzger (1932–2009) discussing Xenakis’s aesthetics. The computer team from the Institute for Musicology of the Technical University consisted of Prof. Dr. Helga de la Motte (b. 1938), Dr. Reinhard Kopiez (b. 1959), and Dr. Christian Dahme as a guest. The video team in charge of filming a documentary on the workshop was coordinated by Franz A. Pindorfer. At Tuchsznaider’s suggestion, the Canadian media artist David Rokeby (b. 1960) presented his award-winning “Very Nervous System” as an interactive sound installation at the workshop. The list of performers included the chamber choir of the Berliner Dirigentenwerkstatt (coordinated by Sabine Wüsthoff), the Clara Schumann children’s choir, the Brandenburg Philharmonic, and vocal soloists. The works by Xenakis that they performed were Krinoïdi (1991), Polla ta dhina (1962), Hiketides: Les Suppliantes (1964), Les Bacchantes d’Euripide (1993), Serment-Orkos (1981), Nuits (1967), Pour la Paix (1981), and À Hélène (1977). The workshop received over two hundred applications from various countries. The event was covered by Berliner Morgenpost.87

In 1983, Xenakis became a member of the music section of the Academy of Arts in West Berlin, together with Aaron Copland and George Crumb (1929–2022). From 1990 to 1993, he was a corresponding member of the same institution in East Berlin, elected in 1989 with György Kurtág (b. 1926) and Edison Denisov (1929–96). From 1993 until his death in 2001, he remained a member of the institution in the reunified city.88

Xenakis in Berlin: Aftermath

The fascination with Xenakis’s music and his theoretical work did not fade following his death, as several doctoral theses and publications in Berlin prove.89 In 2007, DAAD and the Technical University collaborated again on a series of concerts, under the name ‘fünf+1 – Raumklangkonzerte’. On 21 September, Daniel Teige performed Xenakis’s 1971 electronic piece Persépolis within the event. Between 6 September and 27 November 2011, an exhibition titled “Kontrolle und Zufall—Iannis Xenakis: Komponist, Architekt, Visionär” (Control and Chance—Iannis Xenakis: Composer, Architect, Visionary) took place at the Berlin Academy of Arts organized by the Schering Foundation, DAAD, Zitty Berlin, and Deutschlandradio Kultur.90 The event hosted a performance of Xenakis’s Légende d’Eer91 as well as the screening of Scherchen’s experimental film Achorripsis.92 In July the same year, inspired by Xenakis’s multimedia spectacles, a soloist ensemble Kaleidoskop performed the so-called “ein Polytop für Iannis Xenakis” on the streets of Berlin.93 In 2021, Berlin-based composer Christian Dimpker (1982) included his piece N. 25/2 Klavierstück V in a Berlin soundwalk as an artistic homage to Xenakis within the Month of Contemporary Music. To commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of Xenakis’s birth, a festival was held in 2022 in Berlin with the title “X100: A Festival in the Spirit of Iannis Xenakis.”94 These and other constantly emerging new events continue the legacy of the city’s former avant-garde resident long after his death.

Berlin-related Chronology

References

BARCZIK, Günter, LABS, Oliver, and LORDICK, Daniel (2009), “Algebraic Geometry in Architectural Design,” in Gülen Çağdaş and Birgül Çolakoğlu (eds.), Computation: The New Realm of Architectural Design: Proceedings of the 27th Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, September 16–19, 2009, Istanbul, Istanbul Technical University Faculty of Architecture, p. 455–65, https://ecaade.org/current/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/eCAADe_2009.pdf

BARTHEL-CALVET, Anne-Sylvie (2009), “De l’ubiquité poïétique dans l’oeuvre de Iannis Xenakis—Espace, Temps, Musique, Architecture,” Intersections: Canadian Journal of Music/Intersections : revue canadienne de musique, vol. 29, no. 2, p. 9–51.

DI SCIPIO, Agostino (2001), “Clarification on Xenakis: The Cybernetics of Stochastic Music,” in Makis Solomos (ed.), Presences of/Présences de Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Centre de Documentation de la Musique Contemporain, p. 71–84.

DI SCIPIO, Agostino (2015), “Stochastics and Granular Sound in Xenakis’ Electroacoustic Music,” in Makis Solomos (ed.), Proceedings of the Conference Iannis Xenakis. La musique électroacoustique-2012, Paris, L’Harmattan, p. 277–96.

EXARCHOS, Dimitris (2008), “Iannis Xenakis and Sieve Theory: An Analysis of the Late Music (1984–1993),” doctoral dissertation, Goldsmiths, University of London.

EXARCHOS, Dimitris (2019), “The Berlin Sketches and Xenakis’s Middle Period Style,” in Alfia Nakipbekova (ed.), Exploring Xenakis: Performance, Practice, Philosophy, Wilmington, Delaware, Vernon Press, p. 21–36.

FÄRBER, Peter (2021), “Scherchens rotierender Nullstrahler (1959): »Idealer« Lautsprecher oder nur Effektgerät?,” in Thomas Gartmann and Michaela Schäuble (eds.), Studies in the Arts-Neue Perspektiven auf Forschung über, in und durch Kunst und Design, Bielefeld, Transcript, p. 113–36, https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839457368-009

HARLEY, James (2004), Xenakis: His Life in Music, New York, Taylor & Francis.

KANACH, Sharon (2003), “The Writings of Iannis Xenakis (Starting with ‘Formalized Music’),” Perspectives of New Music, vol. 40, no. 1 (Winter), p. 154–66.

KERMIT-CANFIELD, Elliot Forrest (2013), “Spatialization in Selected Works of Iannis Xenakis,” master’s dissertation, the Pennsylvania State University.

MATOSSIAN, Nouritza ([1981] 2022), Xenakis, Electronic edition, Armida Publications.

PRESSE- UND INFORMATIONSAMT DES LANDES BERLIN (ed.) (1964), Ford Foundation Berlin Confrontation: Artists in Berlin, Berlin, Brüder Hartmann.

SCHEUBEL, Robert Schmitt (ed.) (2012), Musik im Technischen Zeitalter: eine Dokumentation, Berlin, Consassis.

SAUNDERS, Francis Stonor ([1999] 2013), The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, New York, The New Press.

SOLOMOS, Makis (1996), Iannis Xenakis, Mercuès, PO éditions.

STERKEN, Sven (2004), “Iannis Xenakis: ingénieur et architecte: une analyse thématique de l’oeuvre, suivie d’un inventaire critique de la collaboration avec Le Corbusier, des projets architecturaux et des installations réalisées dans le domaine du multimédia,” doctoral dissertation, Ghent University.

TURNER, Charles (2012), “Why Bohor?,” in Makis Solomos (ed.), Proceedings of the international Symposium Xenakis, Xenakis, The Electroacoustic Music, Paris, University of Paris, p. 97–108.

TURNER, Charles (2014), “Xenakis in America,” doctoral dissertation, the City University of New York, https://monoskop.org/File:Turner_Charles_Xenakis_in_America.pdf

VAGOPOULOU, Evaggelia (2007), “Cultural Tradition and Contemporary Thought in Iannis Xenakis’s Vocal Works,” doctoral dissertation, University of Bristol.

VARGA, Bálint András (1996), Conversations with Iannis Xenakis, London, Faber & Faber.

WEIBEL, Peter, BRÜMMER, Ludger, and KANACH, Sharon (eds.) (2020), From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today, Karlsruhe, Hatje Cantz, https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today

XENAKIS, Iannis (1971), Musique. Architecture, Paris, Casterman.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1985), Arts-Sciences, Alloys: The Thesis Defence of Iannis Xenakis before Olivier Messiaen, Michel Ragon, Olivier Revault d’Allonnes, Michel Serres, and Bernard Teyssèdre, translated by Sharon Kanach, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon.

XENAKIS, Iannis ([1963] 1992), Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Music (rev. ed.), additional material compiled and edited by Sharon Kanach, Stuyvesant, New York, Pendragon.

XENAKIS, Iannis (2008), Music and Architecture: Architectural Projects, Texts, and Realizations, translated, compiled and presented by Sharon Kanach, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon Press.

Other Sources

Archival materials kindly provided by German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, or DAAD) and Berlin Academy of Arts (AdK).

Conversations with Mâkhi Xenakis, Folkmar Hein, James Harley, and personnel of DAAD.

Gravesaner Blätter (Gravesano Review) (1955–66), Akademie der Künste, https://archiv.adk.de/bigobjekt/44596

1 I would like to thank Mâkhi Xenakis, Folkmar Hein, German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and the Berlin Academy of Arts (AdK) for their kind help in providing me with archival material.

2 This was an influential high-density residential building design with an aim to serve the purpose of a self-sufficient smaller-scale city.

3 One of the most successful of Le Corbusier’s realizations, La Cité Radieuse (The Radiant City), was designed in Brutalist architectural style.

4 This project was located in the Westend district, near the Olympic stadium. Today it is known as Corbusierhaus.

5 Le Corbusier terminated Xenakis’s employment on September 1, 1959. Xenakis had worked at his studio since December 1947 (Turner, 2014, p. xvii).

6 Sterken, 2004, p. 295 and Xenakis, 2008, p. 308. Matossian ([1981] 2022) mentions Xenakis being involved in partial solutions to the project (p. 163).

7 For example: Alvar Aalto (1898–1976), Walter Gropius (1883–1969), and Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012).

8 Official website of the Le Corbusier Foundation: https://www.fondationlecorbusier.fr/oeuvre-architecture/projets-urbanisme-berlin-allemagne-1958/

9 This composition, scored for an ensemble of 21 musicians, was published by Berlin-based publishing house Bote & Bock. It was the first published score by Xenakis (Turner, 2014, p. 26).

10 Xenakis [1963] 1992, p. 15, 24, 260; Varga, 1996, p. 33–40.

11 Di Scipio, 2015, p. 289.

12 Varga, 1996, p. 36.

13 Harley, 2004, p. 11.

14 This is an anthropometric system of proportions based on the golden mean. The graphic representation of Modulor appeared on the cover of this ninth edition for the first time and remained unchanged until the final twenty-ninth edition in 1966. Prior to that, the Review used a neutral cover design, deprived of any illustrations.

15 Turner, 2014, p. xviii; Di Scipio, 2015, p. 289. Xenakis also expressed his gratitude to Scherchen in the preface to the book, written in 1962 (Xenakis, [1963] 1992, p. x).

16 Apart from the first text (“The Crisis of Serial Music”), which was published in French as “La crise de la musique serielle“ and the second text (“Probability Theory and Music”), which was published in German as “Wahrscheinlichtkeitstheorie und Musik,“ all the other texts were published in both German and English.

17 Varga, 1996, p. 36; Sterken, 2004, 349f. Under a working title SCHR 100, Xenakis sketched out the draft in the summer of 1961. He planned to further explore the hyperbolic paraboloid shapes with which he had previously worked along with Le Corbusier on the Philips Pavilion for the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. The project was most probably abandoned due to the lack of funds. The Berlin Academy of Arts archives contain three of Xenakis’s sketches for the auditorium under the shelf-mark Scherchen 1442. The sketches, representing the top and perspective views of a typical Xenakian hyperbolic paraboloid structure, are dated September 8, 1961 (Figs. 3.1–2).

18 Kanach, 2003, p. 155.

19 Akademie der Künste, https://archiv.adk.de/bigobjekt/44596

20 This is not to be confused with a spectrophone–an instrument used in spectral analysis as an adjunct to the spectroscope.

21 The disposition of loudspeakers on a sphere follows the disposition of faces of an Archimedean solid truncated icosahedron. A prototype is well documented by Cathy van Eck at “An Active Loudspeaker by Hermann Scherchen,” Between Air and Electricity,

http://microphonesandloudspeakers.com/2017/03/10/active-loudspeaker-hermann-scherchen/22 Färber, 2021, p. 130–3. The screening of the film was missing a long-lost soundtrack. The version with the soundtrack would be shown four years later at the festival Kontakte ’15 in Berlin.

23 For the historical background of the Western efforts to support artistic movements in Europe to combat the political influence of the Soviet Union, see Saunders, [1999] 2013.

24 For example: Boris Blacher (1903–75), John Cage (1912–92), Hans Werner Henze (1926–2012), György Ligeti (1923–2006), and Luigi Nono (1924–90) (Scheubel, 2012, p. 13f).

25 Today Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of the World’s Cultures).

26 The reviews are reprinted in Scheubel, 2012, p. 200–9, together with two letters by Xenakis, addressed to Stuckenschmidt.

27 This American private foundation was founded in 1936 by industrialists Edsel and Henry Ford (see www.fordfoundation.org).

28 Xenakis, [1963] 1992, p. 371, Varga, 1996, p. 44, Harley, 2004, p. 31, and Turner, 2014, p. xvii.

29 The Berlin Academy of Arts archives, shelf-mark Scherchen 963. The folder contains twenty-one letters and one telegram of correspondence between Scherchen and Xenakis.

30 Vagopoulou, 2007, p. 16. The program began in 1963, and throughout the following decades, the organizers invited many famous composers, among whom were Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020), György Ligeti, Morton Feldman (1926–87), John Cage, Arvo Pärt (b. 1935), Luigi Nono, La Monte Young (b. 1935), and Olga Neuwirth (b. 1968). It is currently called Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD (The DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program) (www.berliner-kuenstlerprogramm.de).

31 In 1967, Daniélou published Xenakis’s essay “ad libitum” in his journal World of Music, and Xenakis cited Daniélou’s North Indian Music in his Formalized Music chapter “Towards a Metamusic” (Turner, 2012, p. 103).

32 A letter from Moritz von Bomhard—the Consultant to the Ford Foundation—to Xenakis, dated 29 August 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 20).

33 Turner, 2014, p. xix.

34 In conversation with Xenakis scholar James Harley (29 June 2022). The existing photograph of the two composers together was likely taken in 1964 but this is not certain. It can be seen at the following link: www.adk.de/de/projekte/2011/cage/programm2011.htm

35 Official website of the Meta-Xenakis Global Symposium 2022: https://meta-xenakis.org. See also Chapter 45 in this volume.

36 Solomos, 1996, p. 31; Varga, 1996, p. 44; Vagopoulou, 2007, p. 16.

37 In conversation with Mâkhi Xenakis (1 June 2021). The address Winkler Str. 4, West Berlin 33—DE (today Winkler Str. 4a, 14193 Berlin) was found on the letter by Scherchen to Xenakis (The Berlin Academy of Arts archives, shelf-mark Scherchen 963), dated 8 October 1963. The house has since been reconstructed, with additions built on its sides and in the back garden (Fig. 3.3).

38 Matossian, [1985] 2022, p. 324–6.

39 Ibid.

40 In conversation with the personnel of DAAD (18 November 2019).

41 The entire correspondence between Xenakis and Bomhard is in English. Enclosed letters to Maslowski and Winckel are in French. The correspondence between Xenakis and Nestler is both in English and French. The enclosed letter to Stresemann is in French, with a translation to German.

42 A letter from Xenakis to Bomhard, dated 12 March 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 38).

43 The electronic studio was located in the main building of the University, in room 1001 (see “Die Umzüge des Studio” (September 2004), Technical University of Berlin, https://fhein.users.ak.tu-berlin.de/Alias/Geschichte/themen/Umzuege_Neubau.html).

44 A letter from Xenakis to Bomhard, dated 10 April 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 35f).

45 A letter from Xenakis to Bomhard, dated 22 May 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 25f), and from Bomhard to Xenakis, dated 29 August 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 30).

46 A letter from Bomhard to Xenakis, dated May 30, 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 23f), and from Bomhard to Scheibe, dated 12 August 1963 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 21f).

47 A letter from Xenakis to Nestler, dated 4 January 1965 (Fig. 3.4) (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 12).

48 A letter from Xenakis to Nestler, dated 18 November 1965 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 4).

49 A letter from Nestler to Xenakis, dated 29 November 1965 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 2f).

50 A letter from Xenakis to Nestler, dated 18 November 1965 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 4).

51 See Ford Foundation Fellows: Composer Iannis Xenakis” (30 April 1964), ARD, https://www.ardmediathek.de/video/kultur-im-norden/stipendiaten-der-ford-foundation-komponist-iannis-xenakis/ndr/Y3JpZDovL25kci5kZS9lOTEyNDFhYy03MGI3LTQ3OWMtODNiYi0zMzNhZDg1YTg5NDM

52 A letter from Xenakis to Stresemann, dated 3 July 1965 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 7–9), and from Nestler to Xenakis, dated 9 July 1965 (DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 5).

53 Xenakis, [1963] 1992, p. viii.

54 The examples are evident in percussion works Persephassa (1969) and Psappha (1975).

55 Exarchos, 2008, p. 54.

56 Xenakis, 1971, p. 38–70 and [1963] 1992, p. 180–200.

57 Exarchos, 2019, p. 34.

58 Solomos, 1996, p. 31 and Harley, 2004, p. 36.

59 Presse- und Informationsamt des Landes Berlin, 1965, p. 14–18.

60 In the Cultural Council Foundation’s journal Preuves, no. 177 (1965), p. 33–6.

61 Turner, 2014, p. 42.

62 Xenakis, 1971, p. 151–60; Solomos, 1996, p. 31; Varga, 1996, p. 45; Sterken, 2004, p. 159–66.

63 Namely, in Republic.

64 Ville contemporaine (Contemporary City) and Ville radieuse (Radiant City) (the latter not to be confused with Cité radieuse).

65 Xenakis, 2008, p. 127f.

66 Barczik, Labs, and Lordick, 2009, p. 456.

67 Xenakis, 1971, p. 159. Xenakis also discusses the Cosmic City in an interview with Renée Larochelle, dated 11 May 1967 (archivesRC, “Yannis Xenakis et son Polytope à Expo 67” (24 March 2021), YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=eh30vxCDYpg, as well as in his thesis defense (Xenakis, 1985, p. 50–7). The text is published in English in Xenakis, 2008, p. 136–41.

68 Xenakis, 1971, p. 20–5; Di Scipio, 2001, p. 83; Scheubel, 2012, p. 76–82. There are slight but no significant differences between the 1962 and 1964 texts. For further details, compare the German transcript in Scheubel 2012 to the French one in Xenakis 1971.

69 DAAD archives, Xenakis folder, p. 19.

70 The world premiere took place in Paris in 1962, performed by Quatuor Bernède.

71 See Les Amis de Xenakis, www.iannis-xenakis.org/en/category/works/music/

72 Ibid.

73 Varga, 1996, p. 45, 68, and 100–2; Harley, 2004, p. 31; Kermit-Canfield, 2013, p. 29f. The first performance, conducted by Boulez, included a second set of brass players. The performance with the proper number of players was conducted by Konstantin Simonovitch (1923–2000) in 1965.

74 See Iannis Xenakis, “Eonta (1963–64),” Boosey & Hawkes,

https://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Iannis-Xenakis-Eonta/44675 Exarchos, 2019, p. 34.

76 Xenakis shared the first prize ex aequo with Anestis Logothetis (1921–94).

77 Harley, 2004, p. 36.

78 Turner, 2014, p. 89.

79 Harley, 2004, p. 89; Barthel-Calvet, 2009, p. 31.

80 See “Inventionen’82,” Inventionen, www.inventionen.de/1982/index_1982.html

81 Apart from the first concert at the Technical University, all performances took place at Berlin Academy of Arts.

82 In conversation with Folkmar Hein (15 November 2019).

83 Ibid.

84 Weibel et al., 2020, p. 156; see also “Werkstatt Elektroakustische Musik” (20 January 1989), Technical University of Berlin, https://fhein.users.ak.tu-berlin.de/Alias/Geschichte/chrono/Werkstatt_E88.html

85 Les Amis de Xenakis, www.iannis-xenakis.org/en/category/works/music/

86 Harley, 2004, p. 202.

87 Archival materials of DAAD.

88 “Iannis Xenakis,” Akademie der Künste, https://www.adk.de/de/akademie/mitglieder/index.htm?we_objectID=52587. The membership certificate and election results can be found in the Academy archives under the shelf-marks AdK-O KM, AdK-O 2330, and AdK-W 134–32.

89 To name few scholars: Eugenia Alexaki, Alexandros Droseltis, Marie Louise Herzfeld-Schild, Peter Hoffmann, and Boris Hofmann.

90 “Kontrolle und Zufall – Iannis Xenakis: Komponist, Architekt, Visionär,” Akademie der Künste,

www.adk.de/de/programm/index.htm?we_objectID=3034791 Archival materials of DAAD.

92 “Kontakte 2015: Freitag, 25.09,” Akademie der Künste,

www.adk.de/de/projekte/2015/Kontakte/teaser_6.htm93 “XI – ein Polytop für Iannis Xenakis,” Kaleidoskopmusik,

https://kaleidoskopmusik.de/en/projects/xi-ein-polytop-fuer-iannis-xenakis/94 “X100: 100 Years of Iannix Xenakis,” Kulturstiftung des Bundes,

https://www.kulturstiftung-des-bundes.de/en/programmes_projects/music_and_sound/detail/x100.html