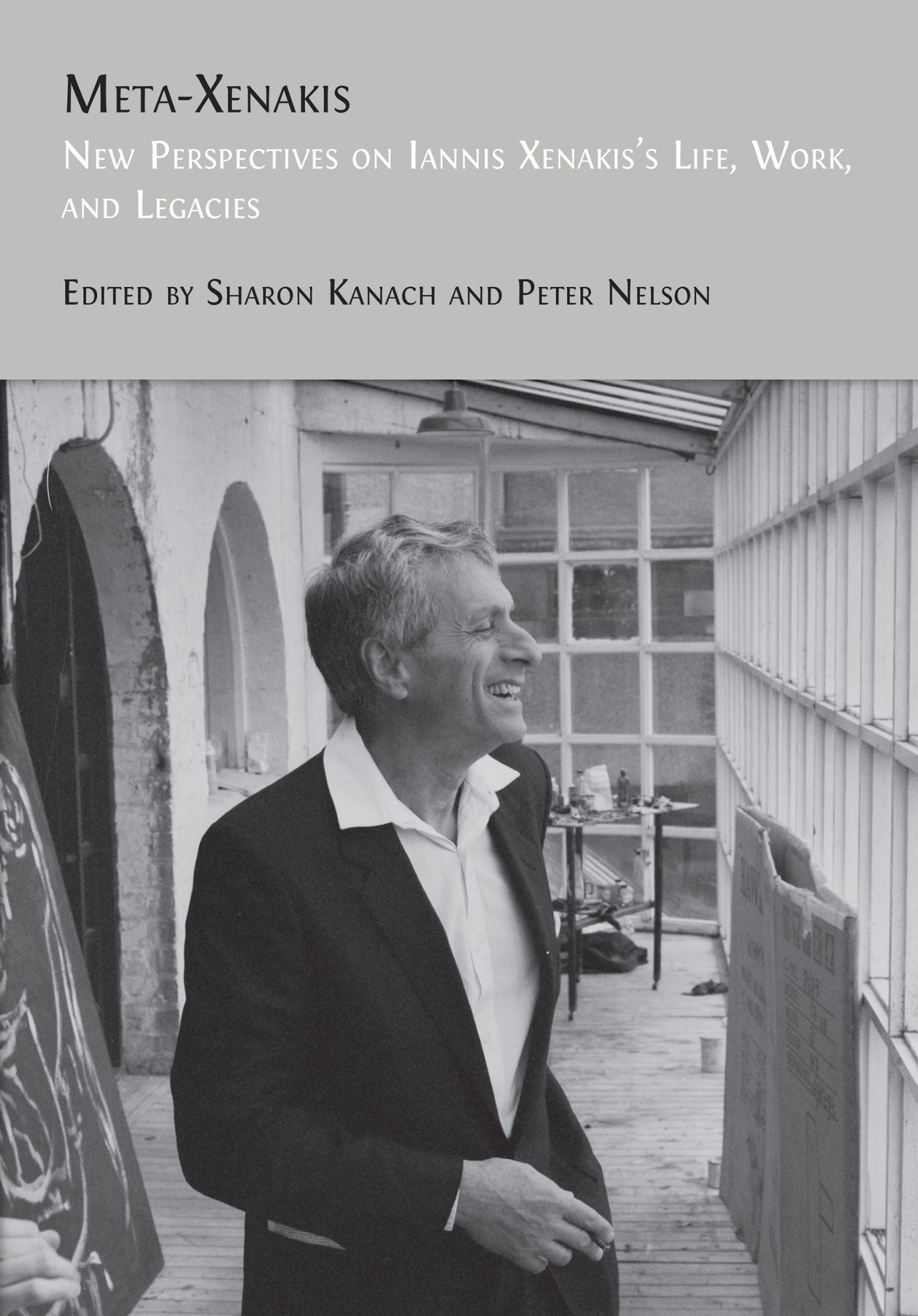

4. Debating the Noise: The Reception of Iannis Xenakis’s Music in Serbia as a Part of the SFRY (1960–90)

Jelena Janković-Beguš

© 2024 Jelena Janković-Beguš, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.06

Over several decades, the city of Belgrade (the current capital of the Republic of Serbia), enjoyed the privilege of being the capital city and the largest cultural center of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY).1 Despite several attempts to bring the relatively young Serbian musical culture closer to the current music trends in Western Europe, the Serbian musical establishment never developed a particular liking for avant-garde music, even during its greatest flourishing in European countries after the World War II (WWII), from 1950 onwards.2 Serialism specifically was never really accepted by the vast majority of Serbian composers, while the compositional techniques of the so-called “Polish School” were assimilated to a certain extent, but they were usually combined with other, more traditional approaches to music composition.3 The situation was somewhat different in other republics of the former Yugoslavia, notably in Croatia and Slovenia, where many more composers ventured into avant-garde and experimental music, and where important contemporary music festivals were founded in the 1960s.4 The majority of Serbian composers, with the notable exception of Vladan Radovanović (1932–2023), were more interested in various neo-classical syntheses, inspired by the work of Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) and Paul Hindemith (1895–1963).5 It is safe to assume that the Serbian composers’ mistrust of the avant-garde was not a consequence of the short-lived “socialist realism” in the period immediately after WWII, but rather was a reflection of the overall artistic climate in Belgrade which was much more inclined towards syntheses of the past and the future than the radical denial of the past in favor of the future.6

These overall standpoints of the Serbian musical establishment in the second half of the twentieth century can be observed in the critical thought of the time, and they are clearly visible in the attitudes towards the music of Iannis Xenakis. While Xenakis himself did not actually belong to any of the predominant currents of the European avant-garde (serial, aleatoric), nor was he close to the American experimental current (represented by John Cage (1912–92) and his followers), he was nevertheless perceived in Belgrade as the exemplary European avant-garde composer. Hence, the reception of his music in Serbia was, for a long time, largely negative, with more favorable opinions about his music only beginning to be expressed in the 1980s.

The written critical texts which will be examined here encompass a period of nearly three decades, from the early 1960s until the end of the 1980s. This timeframe was chosen because the beginning of the 1990s marked the onset of the dissolution of the SFR Yugoslavia and a profound change in the cultural landscape in Serbia.

Throughout the observed period, Radio Belgrade Third Programme (founded in 1965) was the tireless promoter of the most contemporary music currents, with a special emphasis placed on European avant-garde music. I am deeply grateful to the musicologist Hristina Medić (b. 1943), who held the position of music editor of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme (1969–2005), and who during that time compiled a vast number of music reviews—a veritable history of the reception of musical life in Belgrade in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s—written by her and by many other music critics. This abundant material chronicles musical life in Serbia and particularly in Belgrade, including the performances of Xenakis’s pieces in the country. Regardless of their relatively small number, these performances always managed to “stir the pot” and they were usually reviewed by more than one music critic.7 H. Medić has recently published this collection of texts, where certain reviews are published for the first time, as they were presented orally on the Radio Belgrade Third Programme.8 The other texts were printed in various daily newspapers (most notably the Politika daily), at the time when printed press was still a powerful mass medium. Another valuable source material that H. Medić placed at my disposal were the program books of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme (1967–9): in these volumes one finds diverse sources such as speakers’ texts for live broadcasts of concerts, transcripts of discussions which took place after the concerts (which were also broadcast live), and a small number of concert reviews from various newspapers.9 Regardless of the abundance of material that I have examined, the present research does not pretend to be exhaustive—rather, it should be understood as an initial stage in studying the impact of Xenakis’s opus on musical life in Serbia, which is yet to be fully grasped.

Xenakis in Serbia

The two earliest mentions of Xenakis and his music in Serbia date from the early 1960s, several years before his music was actually presented in concert in Belgrade. Both articles were written by one of the most prominent Serbian music writers (and, early in his career, also a composer) Dragutin Gostuški (1923–98), who spent his entire professional career at the Institute of Musicology of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. His position among Serbian composers and music writers of his generation is unique due to his keen interest in classical Greek culture, which is interesting in the context of his attitude towards Xenakis’s opus.10 Gostuški composed a small number of moderately modern works, but already at the beginning of the 1960s—coinciding with the emergence of interest in the music avant-garde in Yugoslavia—he stopped writing music and devoted himself to musicology.11 The first article is highly illustrative of the Serbian music establishment’s attitudes towards the music avant-garde of which Xenakis’s opus was considered symptomatic. The article entitled “Uz račun verovatnoće” (Alongside the Calculation of Probability) addresses the topic of the “crisis of music.”12 This art form, in Gostuški’s opinion, became alienated from the audiences due to the extreme nature of many avant-garde and experimental compositions. Gostuški begins his text with the following observation (see Figure 4.1):

One, hitherto unknown composer with a Greek last name, has appeared in Paris with a new system of composing music: he took the tables of probability calculation, he substituted the numbers with notes, he made additions and subtractions, he multiplied and divided, and so on and so forth. The end result was a miniature score which was performed by a well-known orchestra Lamoureux. […] [N]one other but Igor Markevitch introduced this haughty young author to the audience.13

Fig. 4.1 Dragutin Gostuški, “Uz račun verovatnoće” (1960). First page of the printed article. © SOKOJ, reprinted with permission, CC BY-NC-ND.

While Gostuški does not actually mention the composer’s name, it is clear from the context that he is speaking precisely about Xenakis, since the author mentions the “calculation of probability,” as undoubtedly one of the most distinctive and recognizable characteristics of Xenakis’s compositions of the time.14 Even though it is a false assumption that Xenakis was “hitherto unknown” in Europe, he certainly was a new name in the Serbian context. For Gostuški, the “moral of the story” about the calculation of probability is that “the so-called crisis of the arts is not an empty word […] but a living reality […] The appearance of the calculation of probability in music–insignificant as it may be for the future of this art–still possesses significant value as a symptom.”15 Gostuški claims that none of the so-called revolutionary systems of composition that emerged from the second decade of the twentieth century have proven satisfactory, resulting in the near constant search for new methods of composition. These methods are often discarded after a short period of experimentation:

None of these systems has experienced any evolution, which is a necessary condition to recognize its vitality. […] We must draw a conclusion that the crisis is self-evident from the simple fact that it is not possible to observe any kind of prosperity—of a style, of works or of composers themselves, unless their personal resourcefulness surpasses their art.16

From Gostuški’s point of view, the experimentation in itself would not be so detrimental for the art of music had it not become obvious that the music was becoming increasingly isolated, detached from the audiences who did not possess the ability to adjust to the near-constant novelties. For him, the word “progress” (in art) represents an “exceptionally cunning trap which unmistakably catches all the cowards who run towards it out of fear that they would be labelled stupid and retrograde.”17 Gostuški claims that it has been decades since any avant-garde work has built its reputation “based on the interested [audiences’] desire to hear it over and over again,” criticizing the current lack of “valuable pieces” that could be compared to Richard Wagner’s (1813–83) overtures, Claude Debussy’s (1862–1918) Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894), Richard Strauss’s (1864–1949) Don Juan (1888), Maurice Ravel’s (1875–1937) Daphnis et Chloé (1912), or Igor Stravinsky’s (1882–1971) Petroushka (1911).18 One can say that time has proven Gostuški wrong, and that a number of avant-garde or experimental pieces have remained in the repertoires of various ensembles across Europe and in the world (including works by Xenakis). However, from Gostuški’s immediate perspective, the art of music composition was endangered by what he observed as the loss of compositional technique in a classical sense—which was being replaced with various pre-compositional procedures. “The application of the calculation of probability to notes can only mean one thing: That music is no longer capable of imposing its own laws but is submitted to a different category of thinking.”19 Gostuški was not happy about the “rise of mathematics” in the works of many avant-garde composers (such as Pierre Boulez (1925–2016), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007), or Xenakis) because music, in his opinion, should adhere to its own set of innate rules.20 Gostuški was apparently unaware that for many avant-garde composers—and this is particularly true of Xenakis—mathematics and natural sciences often represented nothing more than a source of inspiration, and not a prescribed route. In Gostuški’s opinion, the calculations could not guarantee the establishment of any logical relations between sounds and human consciousness, which is why the result of such procedures “does not belong to music.”21 Thus he concludes his text with a sardonic remark:

Today we have the score which has originated from the calculation of probability; tomorrow we might have the one which has resulted from a cheese pie recipe. In any case, listening becomes redundant.22

The next year (1961), Gostuški had a chance to meet Xenakis in person in Tokyo, Japan, where the Serbian author was a delegate at the congress entitled “Tokyo East-West Music Encounter”, and he published an article about it (see Figure 4.2).23 The congress incorporated a rich festival concert program, with ensembles and artists such as the New York Philharmonic, Gewandhaus Orchestra, Isaac Stern (1920–2001), and so on. Although Gostuški does not provide sufficient detail, it can be concluded that Xenakis was one of the featured composers at the congress since he had an opportunity to present himself and his work to the attendees. In contrast to the dislike of Xenakis’s music, Gostuški had nothing but sympathy “for the Greek-turned-French composer of a nonchalant ‘Saint-Germain’ demeanor, and we parted ways as friends.”24 However, Gostuški was quick to admit that, regardless of this amicable encounter, he still could not grasp the music of his Greek-French peer:

[M]y general impression about his music is precisely that all of it lacks some sort of calculation, no matter of which sort. The last time I had heard something similar was when kitchen plates were broken in a dining room of a ship, due to rough weather. The main difference lies in the fact that the second case carried more logic–that is, a better connection between the cause and effect.25

Obviously, to an ear unfamiliar with “sound masses” and “clouds,” these music structures could have appeared as being completely arbitrary. Nevertheless, in one of my earlier analyses, I identified numerous points of convergence between the music-theoretical writings of Xenakis and Gostuški from the mid- and late 1960s—these proximities are especially observable in their relation to Greek Antiquity and its influence on European music and art at large.26 Had Gostuški had more time to spend in the company of Xenakis, discussing philosophical and artistic matters which were dear to both of them, he might have changed his negative attitude towards Xenakis’s music—the attitude which was, in fact, illustrative of Gostuški’s rejection of the post-WWII avant-garde as a whole, and of his own failure at finding any musical meaning in these radically untraditional compositional endeavors.

The greatest merit for promoting Xenakis’s music in Belgrade goes to the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, which in 1967 launched a concert cycle entitled Muzika danas (Music Today); the cycle was renamed Muzička moderna (Musical Modernism) the following year. This cycle of concerts and live broadcasts, initiated by Mira Daleore, the music editor-in-chief of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme at the time, lasted until 1985 and it introduced many important pieces of European and American avant-garde and experimental music to audiences in Belgrade and in Serbia (thanks to live broadcasts). Interestingly, Xenakis was among the most performed contemporary composers in the cycle, as his pieces were heard in eleven concerts (ten different pieces in total), which was undoubtedly due to his remarkable reputation in Europe and elsewhere.27 In addition, during the first two years (until April 1969) each concert was followed by a conversation between invited intellectuals—music critics, composers, etc.—which was also broadcast live, and which provided the first critical commentary of the performed pieces.28

Fig. 4.2 Dragutin Gostuški, “Muzički sastanak Istoka i Zapada” (1961). First page of the printed article (excerpt). © SOKOJ, reprinted with permission, CC BY-NC-ND.

According to the compendium of music critical texts I have examined, the first performance of Xenakis’s music in Belgrade and Serbia took place on 28 December 1967, at the Youth Cultural Center (Dom omladine Beograda—DOB), in the final concert and live broadcast of the Muzika danas cycle that year. The program was performed by an ensemble of musicians from Belgrade led by the conductor Konstantin Simonovitch (1923–2000) with the soloist Arlette Sibon-Simonovitch on ondes Martenot.29 K. Simonovitch chose to present Xenakis’s Analogique A + B for nine strings and tape (1958/9), paired with works by Niccolò Castiglioni (1932–96), André Jolivet (1905–74), Edgard Varèse (1883–1965), and Serbian contemporary composer Vladan Radovanović (1932–2023). The ensuing conversation was led, as usual, by the Serbian music critic Pavle Stefanović (1901–85), himself a keen advocate of the most contemporary music currents, while other participants were K. Simonovitch, Serbian composer Berislav Popović (1931–2002) and Croatian critic Petar Selem (1936–2015).30

After the concert, Simonovitch elaborated on the relationship between the instrumental and electronic sounds of Analogique A + B, and he described the piece as Xenakis’s “etude rather than a proper composition. At the same time, it is his first serious piece which is devoid of any [external] effect.”31 Popović remarked that he was impressed by “all this mathematical approach, a very rational relationship towards the material,” and especially by Xenakis’s effort to “establish a constructive engine which would push the whole thing forward.” In his opinion, this “constructive engine” can be found in the diversity of sound sources (traditional instruments versus electronic sounds) and their confrontation; however he was under the impression that “in this case, these two sources were incongruent, that they did not merge and that they often appeared as an artificial echo… and that we did not get a crown achievement as a result of Xenakis’s efforts.”32 Thus, the first opinions after listening to Xenakis’s music in Belgrade were not very favorable, however it is possible that the performance itself, carried out by local musicians who probably had little or no experience in performing such complex sound structures or insufficient time to rehearse with the guest conductor diminished the overall impression of Analogique A + B.

The following year, 1968, saw two performances of Xenakis’s works in Belgrade. The first concert, entitled “Konkretna muzika—Elektronska muzika” (Musique Concrète—Electronic Music) took place on 22 April at the Belgrade Philharmonic Hall, and it was performed by the members of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales of Radio France under the technical and artistic leadership of Ivo Malec (1925–2019) and François Bayle (b. 1932) (Malec also joined the conversation after the concert).33 On this occasion, the Serbian audience had an opportunity to hear Xenakis’s first venture into electroacoustic music, his famed composition Diamorphoses (1957–8). However, the conversation after the concert took an unexpected turn, since the traditionally oriented composer Enriko Josif (1924–2003) disputed the right of the pieces on the program to be called “music.” His interlocutors—Malec, Stefanović, and Selem, all responded with their “defense” of electroacoustic music, which Stefanović considered a “creation of the human consciousness,” while Selem discussed the establishment of a new music hierarchy which was replacing the traditional one—“only it is no longer absolute but relative, and it is valid for each individual case in which it is created.”34 Selem also published a review of this concert in which he assessed Diamorphoses rather unfavorably: while he commended Xenakis’s attempt to create autonomous sound structures, intentionally obscuring the origin of sounds, Selem thought that the piece was “still rudimentary” (especially compared to more recent compositions by Malec, Parmegiani, and Bayle) and unsuccessful in avoiding “naturalistic representation.”35

The second concert in 1968 which featured Xenakis’s music took place on 17 October at the Belgrade Philharmonic Hall. Once again, Konstantin Simonovitch led a group of musicians from Belgrade; however, Xenakis’s famous piece Nomos Alpha for solo cello (1966) was performed by a guest from France, cellist Jacques Wiederker. A brief review written by the critic Branko Dragutinović (1903–71) and published in the daily Politika on 22 October does not provide any qualitative assessment of the pieces performed at the concert,36 so the only trace of reception is found in the transcript of the discussion which ensued after the concert.37 Together with Stefanović and Simonovitch, the interlocutors were Gostuški and Rajko Maksimović (1935–2024), at the time one of the young Serbian composers interested in certain techniques of the “Polish School.” Once again, the discussion about Nomos Alpha showed a lack of understanding for the constructive procedures which governed the compositional process in this piece. While Maksimović was impressed by the virtuosity of the cellist, he scrutinized the piece which he thought represented nothing more but a “demonstration of what the instrument can play. […] We had 20–25 or 30, I don’t know exactly how many, technical procedures, let’s call them tricks, which […] are completely unconnected to one another.’ Simonovitch, who had personally collaborated with Xenakis in the past, rightfully observed that music professionals’ experience of listening to music is marred by a burden of habit, of certain expectation, which can prove limiting “if one considers certain music which has nothing to do with earlier music, which is the case with Xenakis, with entire Xenakis. In such a case, a wider audience is far more open [to novel sound] than the audience of composers, musicians, etc.”38 Stefanović, who was always open minded and curious when it came to novelty, still expressed his disappointment in himself that he was not able to understand any of the mathematical “precompositional” procedures and he regretted that the audience of the broadcast did not have a more competent interlocutor for this particular segment of the discussion.39 It is obvious that these early attempts at presenting Xenakis’s music in Serbia (in the seventh decade of the twentieth century) were hampered by the inability of local music critics to adequately mediate the full scope of the composer’s creative endeavor, even to the interested audiences.

The following performance in Belgrade of a piece composed by Xenakis took place four years later, on 10 February 1972: his choral work Nuits (1967–8) was performed by the vocal soloists of the French Radio and Television choir at the Belgrade Philharmonic Hall, and the ensemble was led by the French conductor Marcel Couraud (1912–86). Two critical reviews of this performance are preserved, one written by the composer (Leon) Miodrag Lazarov (= Lazarov Pashu, b. 1949) for the Radio Belgrade Third Programme (broadcast on 11 February), and the other one published in the daily newspaper Politika by the composer Aleksandar Obradović (1927–2001). The younger of them, Lazarov, who at the time of this performance was still a student of composition, would later establish himself as one of a few radical minimalists in Serbian art music.40 Obradović, on the other hand, belonged to the generation of composers who assimilated certain compositional techniques of the “Polish School” (notably controlled aleatorics) and elements of György Ligeti’s (1923–2006) micropolyphony, and mixed them with traditional motivic work and sonata forms. Concerning the performance of Nuits, both critics point out the exemplary musicianship of the French artists. Lazarov qualifies them as “an ideal instrument” for the most contemporary music.41 Obradović was even more pleased with the French artists:

Twelve soloists of this chamber choir (6 female and 6 male) dispose of wonderful voice materials, homogenous, and exquisitely uniform, with astonishing perfection of pitch control […]. I was under the impression that I was listening to a living organ, and that the excellent and intelligent artist—the conductor Marcel Couraud—was pulling out sound colors from this instrument as if he were changing organ stops and manuals. His refined affinity for extremely different styles […] reveals high professionalism and extensive knowledge.42

While neither critic reviewed the individual pieces performed on the program, being more focused on the musicianship of the French choir and their conductor, it is interesting to mention that Obradović stressed out the dedication of the piece Nuits “to all political prisoners in the world!”43 As a lifelong communist who as a teenager actively participated in WWII as a member of the liberation army, Obradović was clearly intrigued by this dedication from a composer who had also survived the horrors of war.44

The next performance of Xenakis’s music in Belgrade took place on 10 January 1974, when his piece Aroura for twelve strings (1971) was performed by the Belgrade Chamber Ensemble, conducted by Boris de Vinogradov (1929–2008), at the Students’ Cultural Center in Belgrade. Subsequently, two largely negative reviews of the concert appeared, this time focusing on the works themselves. The first one, written by the musicologist Mirjana Veselinović (= Veselinović-Hofman, b. 1948), revealed the author’s impression that the extra-musical organization of the sound material in all the performed pieces did not produce truly impactful music.45 Concerning Xenakis’s piece Aroura, Veselinović briefly remarks that this work “lacks the musical expression of its professed goal: to discover and to investigate layers of sound.”46 Petar Ozgijan (or Osghian, 1932–79), Belgrade-based composer and occasional critic, who (similarly to Obradović) was keen to combine certain avant-garde compositional techniques with essentially neo-classical musical language, had an even harsher account of the pieces performed at the concert:

One of the common characteristics of nearly all performed compositions […] is the lack of good measure in terms of duration, where the authors simply did not pay attention to the perceptive abilities of a listener. This negative quality could be observed […] notably in Xenakis’s Aroura (1971), whose length doesn’t only cause fatigue, but appears to be even more stretched out and boring due to the persistent repetition of the same compositional procedures.47

Ozgijan also noted that the conductor Boris de Vinogradov “limited himself to the role of a reliable pointsman, allowing his exquisite musicians to navigate their own path through this ‘traffic jam.’”48 Clearly, Aroura, with its profuse use of glissandi over the duration of approximately twelve minutes, combined with an underwhelming performance, proved to be too much for Serbian music critics.

Equally unfavorable was the reception of Xenakis’s Medea for male choir, four instruments and percussion (1967), on its performance at the Student’s Cultural Center in Belgrade on 21 November 1974. The French conductor Couraud, who had received praise for his performance with the French vocal ensemble two years earlier, performed this time with the Belgrade Radio and Television Choir. Aleksandar Obradović commended the efforts of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme to keep the Belgrade audiences in touch with the contemporary music world within their series of concerts aptly titled Musical Modernism. However, he thought that the program was “pretty one-sided” and he also noted that the “pieces by the well-known bearers of contemporary modernism, Ligeti (Lux aeterna–for mixed choir (1966)) and Xenakis […] left more of an impression of cerebral creations then music that one would happily listen to more than once.”49 In his opinion, a part of that lackluster effect resulted from Couraud’s routine approach, which lacked creativity that could have stimulated the performance potential of the choir, consequently unravelling more of the musical substance of the abovementioned pieces.50 Lazarov was equally unimpressed with the performance (which is reflected in the title of his review, “Nedorađenost u studiranju detalja” (The Incomplete Study of Details)):

A great apprehension in approaching a contemporary music score is caused by its complexity. If it is not presented in its full scope, and especially if certain imprecision is allowed in the interpretation of details, the modern score loses its flexibility. […] [At this concert] we must ascertain the lack of minute study of the scores, which inevitably reflected on our impression about the presented pieces.51

However, his criticism is directed not only towards the performance, but also towards the pieces themselves, and especially towards Xenakis’s Medea which he labels the “biggest surprise in a negative sense.”52 Following the ancient Greek instrumental and vocal tradition while enriching it with certain procedures of the avant-garde principles of composition, Xenakis created, in Lazarov’s opinion, a “ridiculous, completely incoherent work which will either represent a passing, temporary weakness and delusion in his opus, or a turnaround in his creative output.”53 While Medea may not represent the pinnacle of Xenakis’s incidental music, it certainly does not deserve the disdainful reviews that it has received from Lazarov or from another sharp-tongued Serbian composer-turned-music critic, Konstantin Babić (1927–2009), whose text is entitled “Neveseo zvuk avangarde” (Unjoyful Sound of the Avant-garde).54 Babić was one of the more traditional composers of his generation who remained faithful to neoclassicism throughout his creative life, and his short text, published in the daily Večernje novosti, clearly illustrates the attitudes of the conservative music circles in Serbia towards the avant-garde music as a whole:

In this concert, […] the same unjoyful picture from the earlier “happenings” of the musical avant-garde was repeated once again. The sparse audience […] greeted with anemic applause the pieces entitled Tužbalica [Threnody], Radosno opelo [Joyous requiem], Medea, Sferoon and Lux aeterna. […] [A]ll these works are oddly similar, and they only present whining and certain stiff horror. […] [A]ll these compositions are based on the repetition of a small number of technical procedures, which lethally impoverishes the already unconvincing content. All this music seems static, immobile, cramped or, at times, manic and hysterical.55

On the other hand, Lazarov displays an increasingly hostile attitude towards any music that is not serial or radically minimalist–since, in his opinion, only these two main principles (“the maximization of serialization and minimization of constitutive elements”) characterize Modernist thinking from the 1960s onwards.56 All other approaches to contemporary music, which fall somewhere “in-between” these two, produce “vulgarisms of a smaller or larger scope.”57 He expresses these attitudes in his review of the concert performance given by the renowned harpsichordist Elisabeth Chojnacka (1939–2017), herself a champion of Xenakis’s music, on 23 February 1978, again at the Students’ Cultural Center (she performed Khoaï for solo harpsichord (1976), among other pieces). While Lazarov calls Chojnacka “the harpsichordist with an extraordinary affinity for performing pieces of avant-garde music (probably one of the most convincing that we have ever heard in Belgrade),” he feels that the majority of pieces performed were exemplary of the abovementioned “third approach,” i.e., neither serial nor minimalist—and in his opinion this is particularly true of the compositions by Xenakis, Luc Ferrari (1929–2005) and partly by François-Bernard Mâche (b. 1935):58

Iannis Xenakis generally finds himself in the rift between the total serialization […] and the amalgamation of Greek folk idioms. However, his harpsichord piece Khoaï apparently insists on these shortcomings of Xenakis’s creativity, the shortcomings caused by the insufficient correlation between the elements necessary for shaping the musical form. Thus, Khoaï is formally divided in two parts: the first is dominated by the elements of quasi-minimalist approach […] and especially by the elements of Greek folklore; in the second part (in stark contrast to the first) we observe neo-punctualist elements (but not in the Webernian sense), closer to atonality in any case. From a structural point of view, this approach does not provide the possibility to ensure the coherence of the piece; these are the shortcomings of earlier Xenakis’s works and they are factually explicit in this piece as well.59

The same harpsichord piece, together with several other important works by Xenakis, was performed once more in Belgrade several years later, on 24 April 1985 at the National Museum in Belgrade. This was a particularly festive occasion as it marked the only time that Xenakis himself visited Belgrade. The concert was co-organized by the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, French Cultural Center (today the French Institute) in Belgrade and the Serbian concert agency Jugokoncert.60 The concert featured Xenakis’s recent compositions dedicated to and written especially for Elisabeth Chojnacka and the percussionist Sylvio Gualda, both of whom performed in this concert: Khoaï, Psappha for percussion (1975), Naama for harpsichord (1984) and Komboï for harpsichord and percussion (1981). According to the musicologist and music critic Zorica Premate (b. 1956), the composer attempted to animate to the extreme all of the creative, performing, and technical capabilities of these sensitive musicians, and he did so to a great result: “the pieces with their enormous internal expressiveness, extraordinary technical demands and untamed temper, left the performers and the audience nearly out of breath.”61 Premate rightfully observes that all these pieces were created within the same circle of inspiration and ideas, with similar compositional-technical and formal solutions. Thus, “[t]he concert was envisaged as the development of a single idea and of a certain creative principle: during the performance it was first exposed, then elaborated in several variants, culminating with the performance of the final piece.”62 Unlike previously cited authors, Premate’s reception of Xenakis’s music is highly favorable:

Iannis Xenakis convinced us with his music that the work created […] with the aid of calculations and mathematical logic, does not have to be inartistic, even when measured by the classical aesthetic methods which observe form, clarity, dramaturgy, and even compositional technique. The performed pieces did not reveal their mathematical, non-media origin, not for a single second. Even more, with their clear, usually fragmentary form, where each segment represents a logical continuation and adds to the dramaturgical development of the whole, and especially with their gigantic agglomerates of energy and authentic temper, these stochastic compositions carry within themselves more liveliness and they draw attention much more that many other, classically composed contemporary pieces. Nevertheless, because Xenakis is above all an artist, and only then mathematician and someone infatuated with computer technology, many bits of his scores show [human] interventions compared to the would-be computer dictated shape of the work. It is apparent that Xenakis uses mathematical programs and their digital superstructure as some sort of ‘material,’ not even as a strict compositional technique; and that after many years of avant-garde experimentation and exploring possibilities with stochastics, music is what is most important to him.63

Premate lauds the exceptional potential of the performers whose temper, as well as their immersion into the performed pieces, contributed a great deal to the success of the concert of Xenakis’s music. She stresses the surprising sonic potential of the harpsichord “which sounded like a powerful percussion instrument such as the xylophone, glockenspiel, bells or marimba, or as an electronic generator.”64 In the manner of a music critic who truly understands contemporary music in all its facets, Premate concludes her review with the following remark: “In his rich creative fantasy, Xenakis has succeeded in creating a sound whose timbre is nearly identical to that of electronic music—but in contrast to the majority of generator synthetized pieces, it contains a high level of living, tangible human emotion.”65

However, the same level of enthusiasm for the same concert was not shown by another Serbian music critic, Milena Pešić (b. 1941). In her account, entitled “Grubost zvuka” (The Roughness of Sound), she focuses on the resemblance of Xenakis’s aesthetic postulates to those of his “role-model” Le Corbusier, “submitting […] to the forms of machinist civilization, castrated lines and cubic shapes.”66 Unlike Premate, Pešić is not impressed with Xenakis’s treatment of musical form and micro-structure:

Using a habitual auditory method of observation, we could not detect the living music cells and their natural morphogenesis in the given timeframe […]. The pieces Naama and Khoaï revealed to what extent this fragile instrument [the harpsichord] could be deformed by the aggression of the cluster sounds. Sylvio Gualda’s virtuoso performance on various percussion instruments, including ceramic jars, did not reduce the acoustic terror, just as the astonishing skill and complementarity between him and Chojnacka in the performance of Komboï was not sufficient on its own.67

While Pešić acknowledges the spirit of experimentation which has contributed to Xenakis’s reputation as one of the most prominent contemporary composers, she comments on what she observes as a certain lack of evolution in his music writing: “the avant-garde, which lasts too long and which stays the same, inevitably becomes fossilized.”68 It has to be mentioned that by the time of Xenakis’s arrival in Serbia, the avant-garde musical thinking had already begun its decline, making way for the rise of postmodernist approaches which were no longer concerned with ideas of progress and novelty, but which (re-)established various forms of dialogue with the musical past.

Conclusion

The final performance of Xenakis’s music in Belgrade during the composer’s lifetime occurred on 26 May 1998, when one of his earliest preserved pieces was included in the concert program of the French contemporary music ensemble Accroche note: Ziya for soprano, clarinet, and piano (1952).69 It was my first live encounter with Xenakis’s music, albeit with an uncharacteristic piece, and the beginning of a life-long fascination with his creative opus.

Owing to the enthusiasm and dedication of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, the presence of Xenakis’s music on Belgrade concert podiums was considerable over several decades (in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s), especially in comparison to the music of other reputable European modernists of his generation. Even though the concerts of the Muzika danas/Muzička moderna/Musica viva cycle usually took place in smaller venues in Belgrade and were not attended by large, live audiences (not including the radio audience), they attracted the interest of various music critics, although their reception of modernist music—including Xenakis’s own—was more often unfavorable than not. Xenakis’s reputation as one of the contemporary music greats, as well as the opportunities to hear renowned European performers, were the most likely reasons for the critics’ interest in these concerts. The pieces themselves were usually received with the habitual skepticism of the Serbian music establishment towards avant-garde music. Only Zorica Premate, and as late as in 1985, fully embraced Xenakis’s musical procédé and paved the way for future understanding of his music in Serbia. However, since the composer’s death, his works have been presented in concerts in Belgrade sporadically, notably within the framework of the International Review of Composers, and rarely in other settings.70 Serbian concert stages have yet to welcome any of Xenakis’s major large-scale works, giving yet another testimony to the persisting traditionalist taste of the majority of Serbian music institutions.71

References

BABIĆ, Konstantin (1974), “Neveseo zvuk avangarde,” Večernje novosti, Monday, 25 November, p. 27.

DRAGUTINOVIĆ, Branko (1968), “Tri gosta u ‘Otelu’. [Muzička moderna],” Politika, Tuesday, 22 October, p. 10.

GOSTUŠKI, Dragutin (1960), “Uz račun verovatnoće,” Zvuk, Jugoslovenska muzička revija, vols. 35–6, p. 258–62.

GOSTUŠKI, Dragutin (1961), “Muzički sastanak Istoka i Zapada,” Zvuk, Jugoslovenska muzička revija, vols. 49–50, p. 527–32.

GOSTUŠKI, Dragutin (1968), Vreme umetnosti. Prilog zasnivanju jedne opšte nauke o oblicima, Belgrade, Prosveta.

JANKOVIĆ-BEGUŠ, Jelena (2017), “‘Between East and West’: Socialist Modernism as the Official Paradigm of Serbian Art Music in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,” Musicologist, International Journal of Music Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 141–63, https://doi.org/10.33906/musicologist.373187

JANKOVIĆ-BEGUŠ, Jelena (2021), Antička (grčka) paradigma u savremenoj umetničkoj muzici. Studije slučaja/konvergencije: Janis Ksenakis, Vlastimir Trajković, PhD thesis, Belgrade, University of Arts, Faculty of Music.

JANKOVIĆ-BEGUŠ, Jelena and MEDIĆ, Ivana (2020), “On Missed Opportunities: The International Review of Composers in Belgrade and the ‘Postsocialist Condition,’” in Biljana Milanović, Melita Milin, and Danka Lajić Mihajlović (eds.), Music in Postsocialism: Three Decades in Retrospect, Belgrade, Institute of Musicology SASA, p. 139–68.

LAZAROV, Miodrag (1972), “Pozitivne strane eksperimenta u muzici,” Radio Belgrade Third Programme, broadcast on 11 February 1972, in Hristina Medić (ed.), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Prva knjiga, 1970–1984, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo, p. 21.

LAZAROV, Miodrag (1974), “Nedorađenost u studiranju detalja,” Radio Belgrade Third Programme, broadcast on 22 November 1974, in Hristina Medić (ed.), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Prva knjiga, 1970–1984, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo, p. 88–9.

LAZAROV, Miodrag (1978), “Muzička moderna,” Radio Belgrade Third Programme, broadcast on 24 February 1978, in Hristina Medić (ed.), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Prva knjiga, 1970–1984, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo, p. 201–2.

MARINKOVIĆ, Sonja and JANKOVIĆ-BEGUŠ, Jelena (eds.) (2017), O ukusima se raspravlja. Pavle Stefanović (1901–1985), Belgrade, Serbian Musicological Society.

MASNIKOSA, Marija (2012), “The Reception of Minimalist Composition Techniques in Serbian Music of the Late 20th Century,” New Sound, International Magazine for Music, vol. 40, no. 2, p. 181–90, https://scindeks-clanci.ceon.rs/data/pdf/0354-818X/2012/0354-818X1202181M.pdf

MEDIĆ, Hristina (ed.) (2023a), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Prva knjiga, 1970–1984, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo.

MEDIĆ, Hristina (ed.) (2023b), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Druga knjiga, 1985–2000, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo.

MEDIĆ, Ivana (2007), “The Ideology of Moderated Modernism in Serbian Music and Musicology,” Muzikologija, vol. 7, p. 279–94.

MEDIĆ, Ivana (2015), “Ciklus koncerata Muzička moderna Trećeg programa Radio Beograda (1967–1985),” in Ivana Medić (ed.) Radio i srpska muzika, Belgrade, Institute of Musicology SASA, p. 141–74.

MEDIĆ, Ivana (2019), “The Impossible Avant-garde of Vladan Radovanović,” Muzikološki zbornik/Musicological Annual, vol. 55, no. 1, p. 157–76, https://doi.org/10.4312/mz.55.1.157–176

MEDIĆ, Ivana (2022), “The Role of the Third Program of Radio Belgrade in the Presentation, Promotion, and Expansion of Serbian Avant-Garde Music in the 1960s and 1970s,” Contemporary Music Review, vol. 40, no. 5–6, p. 482–511, https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2021.2022885

MILIN, Melita (1999), Tradicionalno i novo u srpskoj muzici posle Drugog svetskog rata (1945–1965), Belgrade, Institute of Musicology SASA.

MILIN, Melita (2006), “Etape modernizma u srpskoj muzici,” Muzikologija, vol. 6, p. 93–116.

OBRADOVIĆ, Aleksandar (1972), “Žive orgulje boga Jana,” Politika, Wednesday, 16 February, p. 9.

OBRADOVIĆ, Aleksandar (1974), “Muzička moderna,” Politika, Tuesday, 26 November, p. 15.

OZGIJAN, P. [Petar] (1974), “Muzička moderna,” Politika, Thursday, 31 January, p. 15.

PEŠIĆ, Milena (1985), “Grubost zvuka (Veče Janisa Ksenakisa),” Politika, Friday, 3 May, p. 11.

PREMATE, Zorica (1985), “Dela Janisa Ksenakisa,” Radio Belgrade Third Programme, broadcast on 26 April 1985, in Hristina Medić (ed.), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Druga knjiga, 1985–2000, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo, p. 492–3.

SELEM, Petar (1968), “Dalje od sonornog stripa,” Telegram, 26 April 1968, p. 6.

STOJANOVIĆ-NOVIČIĆ, Dragana (2007), Oblaci i zvuci savremene, Belgrade, Fakultet muzičke umetnosti—Signature, Katedra za muzikologiju.

STOJANOVIĆ-NOVIČIĆ, Dragana (2013), “Musical Minimalism in Serbia: Emergence, Beginnings and Its Creative Endeavours,” in Keith Potter, Kyle Gann, and Pwyll ap Siôn (eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, Farnham, Ashgate, p. 357–67, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613260-31

VESELINOVIĆ, Mirjana (1974), “Pitanje umetničkog dejstvovanja,” Radio Belgrade Third Programme, broadcast on 11 January 1974, in Hristina Medić (ed.), Evropa i Beograd 1970–2000: Muzička hronika Beograda u ogledalu kritičara, dokument vremena. Prva knjiga, 1970–1984, Belgrade, RTS Izdavaštvo, p. 57.

Archival Material

Program book of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, cycle Muzika danas, year 1967.

Program book of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, cycle Muzička moderna, years 1968–9.

1 As the successor of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (1918–29) and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929–45), the new communist-led country was created in 1945, under the name of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. The name was changed in 1946 to the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, and in 1963 it was renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During all these transformations, Belgrade, as the country’s largest city, remained the administrative capital of the country.

2 See more in Milin, 2006, p. 93–116.

3 This framework is analysed in great detail in Milin, 1999.

4 The Music Biennale Zagreb was established in 1961, and the Yugoslav Music Review was established in Opatija in 1964. The first festival was international, while the other one was of a Yugoslavian focus.

5 About Vladan Radovanović’s unique position among Serbian composers of his generation, see Medić, 2019, p. 157–76.

6 See Milin, 2006, p. 103–15, and Medić, 2007, p. 279–94.

7 The translations of all texts from Serbian into English language are the author’s.

8 Medić, 2023a, 2023b.

9 A thorough analysis of the key role that Radio Belgrade Third Programme had in promotion of the contemporary—i.e., avant-garde and experimental—music can be found in Medić, 2015, p. 141–74 and Medić, 2022 (the latter article is published in English).

10 Gostuški’s magnum opus, his book Vreme umetnosti. Prilog zasnivanju jedne opšte nauke o oblicima (Time of Art: Contribution to the Foundation of a General Science of Form) clearly demonstrates his admiration of Greek Antiquity (Gostuški, 1968).

11 More on the subject of “moderate modernism” in Serbian art music: Medić, 2007, p. 279–94.

12 Gostuški, 1960, p. 258–62.

13 Gostuški, 1960, p. 258 (see Figure 4.1).Igor Markevitch (1912–83) was the principal conductor of the Orchestre Lamoureux from 1957–61.

14 This reference to Xenakis in Gostuški’s text was first observed by the musicologist Dragana Stojanović-Novičić in Stojanović-Novičić, 2007, p. 61–2.

15 Gostuški, 1960, p. 258 (see Figure 4.1).

16 Ibid. (see Figure 4.1).

17 Ibid., p. 259 […[O]vde je reč ‘napredak’ izvanredno lukava klopka u koju bez pogreške uleću sve moguće kukavice iz straha da ne budu oglašene za glupe i nazadne].

18 Ibid., p. 260 […[V]eć decenijama nema avangardističkog dela koje je steklo renome na osnovu želje zainteresovanih da bude ponovo, tj. stalno slušano.’ ‘Moderna svetska muzika nema standardnih dela koja bi se mogla uporediti sa Wagnerovim uvertirama, Debussy-evim Faunom, Straussovim Don Juanom, Ravelovim Daphnis i Chloe ili Petruškom Stravinskoga].

19 Ibid., p. 261 [Račun verovatnoće među notama ima znači jedan glavni smisao: muzika nije više u stanju da sama sebi postavlja zakone, već se podređuje jednoj drugoj kategoriji mišljenja].

20 While expressing his dislike for this new “trend” in contemporary music, Gostuški also implicitly announced his impending withdrawal from composing music (ibid.): “I do not see a reason why I should contribute to such state of the matter. […] If that is what you call progress of music, then I refuse to take part in such a progress” [I opet ne vidim razlog da se pridružim takvom stanju stvari. […] Ako se to zove napretkom muzike, onda u tom napretku ne želim da učestvujem].

21 Ibid. [I zato rezultat ne spada u muziku].

22 Ibid. [Danas je već pred nama partitura proizašla iz recepta računa verovatnoće; sutra može iz recepta pite sa sirom].

23 According to Gostuški, the congress was organised by the UNESCO and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in April 1961. Cf. Gostuški. 1961, p. 527. See also Stojanović-Novičić, 2007, p. 62.

24 Gostuški, 1960, p. 528 [Za pofrancuženog Grka nonšalantnog senžermenskog ponašanja imao sam lične simpatije i rastali smo se kao prijatelji].

25 Ibid. [[O]snovan utisak koji sam o njegovoj muzici dobio [je] baš taj da u svemu tome nedostaje nekakav račun, kakav bio da bio. Nešto slično čuo sam poslednji put kad su se usled bure polomili tanjiri u brodskoj trpezariji. Glavna je razlika što je u ovom drugom slučaju bilo više logike, tojest bolje povezanosti između uzroka i posledice].

26 I have examined the relationship of Xenakis’s and Gostuški’s poetics in my doctoral dissertation: Janković-Beguš, 2021.

27 Cf. Medić, 2015, p. 142.

28 Ibid, p. 144.

29 Belgrade-born conductor Konstatin Simonovitch (b. Simonović, sometimes also credited as Simonovich or Simonovic) was the founder and conductor of the Ensemble instrumental de musique contemporaine de Paris (Paris Instrumental Ensemble of Contemporary Music). In 1966, he was the recipient of the Grand Prix du Disque for his interpretation of Xenakis’s Eonta with that ensemble (the same vinyl LP record also included the recordings of Metastasis and Pithoprakta by the Orchestre National De L’O.R.T.F. with the conductor Maurice Le Roux).

30 The creative opus of Stefanović as a music writer and promoter of contemporary music was elaborated in detail in the collection of papers: Marinković and Janković-Beguš, 2017. The transcript of the conversation is taken from the program book of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, cycle Muzika danas, year 1967. The page numbers refer to the retyped transcript of the discussion.

31 Program book Muzika danas, 1967, p. 14 [… [T]o bi se više moglo nazvati etidom nego li zaista delom. To je u isto vreme prvo njegovo ozbiljno delo lišeno svakog efekta].

32 Ibid., p. 16 [… [k]od Ksenakisa vrlo imponuje sav taj matematički naučni prilaz, mislim jedan vrlo racionalan odnos prema tom materijalu... Međutim, mene najviše impresionira u ovoj Ksenakisovoj kompoziciji napor kompozitora da... pokušava da uspostavi taj jedan konstruktivni motor koji bi gurao celu tu stvar... Čini mi se taj konstruktivni motor, a to je mislim opet jedan fenomen samo raznovrsnost izvora, jedna tradicionalna grupa instrumenata, jedan zvučnik sa elektronskim zvucima, u tom jednom suprotstavljanju jedna suprotnost mislim je jedna poluga za eventualno pokretanje. Međutim, čini mi se da su ta dva izvora u ovom slučaju odudarala, da se nisu spajala, da su delovala kao neki vrlo često veštački eho... i da nismo dobili krunu rezultat Ksenakisovog napora].

33 Other interlocutors were Stefanović, Serbian composer Enriko Josif (1924–2003), and Selem. The program of the concert featured works by Pierre Schaeffer (1910–95), Ferrari, Luciano Berio (1925–2003), Xenakis, Bernard Parmegiani (1927–2013), Bayle, and Malec. Cf. Program book Muzika danas, 1967, p. 21.

34 Ibid., p. 22 [Dakle, bez obzira na jezički sistem, čim nešto, koji bilo predmet zvuči a ne zato što spontano prirodno zvuči, nego je odabrano čovekovom svešću da zvuči i da se kombinuje sa nekim drugim momentom zvučanja, tu počinje muzičko mišljenje]; ibid., p. 23 [Jer, koliko sam ja shvatio, jedina konkretna stvar koja nam je ovde trebala biti razmeđa, razgraničenje dokle muzika ide, odakle ne ide, u prvom času nije bilo samo pitanje nestanka stanovite hijerarhije, vrijednosti, jer se ona opet stvara samo što ona sad više nije apsolutna, nego relativna i vredi za svaki pojedini slučaj u kojem se stvara].

35 Selem, 1968, p. 6 [Xenakis čak izričito, u komentaru svoje skladbe, postavlja zahtjev za oslobađanjem od porijekla, ili, kako on kaže, treba “zaboraviti definiciju porijekla zvukova”. Ipak, i pored očitih ambicija da se u prostorima što ih otvara mogućnost tehničke obrade pa i proizvodnje zvuka ostvare autonomnosti glazbene strukture, ove skladbe ostaju još rudimentarne, a njihova se sonorna događanja, kao po nekoj fatalnosti, počinju vezivati uz stanovitu naturalističnu predodžbenost, uz stanovite asocijativne smjerove].

36 Program book of the Radio Belgrade Third Programme, cycle Muzička moderna, years 1968–9, p. 10–11 [Inače što se tiče ove Ksenakisove kompozicije, to je po koji put već imamo kompoziciju za solo instrument koja je samo demonstracija onoga što može instrument da odsvira. Imali smo jednog izvrsnog instrumentalistu virtuoza večeras, svakako virtuoz. Međutim, imali smo jednog 20–25 ili 30, ne znam koliko postupaka tako nekih tehničkih, da ih nazovemo, trikova koje je on izveo ili koji su totalno nepovezani među sobom].

37 Dragutinović, 1968.

38 Ibid, p. 12 [Na kraju krajeva, radi se o tome da mi slušamo muziku ipak sa jednom izvesnom navikom, odnosno navikom izvesnih struktura koje poznajemo, analize koje smo radili i koje nas možda čak i sputavaju. Ako se radi o jednoj demonstraciji, o jednoj muzici koja nema uopšte nikakve veze sa prethodnom muzikom što je slučaj sa Ksenakisom, sa celokupnim Ksenakisom. U tom slučaju je široka publika daleko otvorenija nego li publika kompozitora, muzičara, itd].

39 Ibid, p. 16–17 [Ali, onako kako sam samo slušajući, dakle, primećujući samo auditivni utisak, opet sam imao onu asocijaciju, nažalost, kao što sam već rekao, ’iz struke’ o kojoj ništa ne znam. [...] Da li za ovu priliku, s obzirom na tako veliki oslonac [...] onaj predmuzički i van muzički u čistoj matematici, da je koja sreća, čini mi se, da nije kad bismo ovde mi za slušaoce imali jednog poznavaoca...].

40 For more on minimalism in Serbian art music, see Masnikosa, 2012, p. 181–90; Stojanović-Novičić, 2013, p. 357–67.

41 In addition to Nuits, they also performed the pieces Exhortatio (1970) by Luigi Dallapiccola, Recitatif, air et variation by Gilbert Amy (1970), and Dodecameron by Ivo Malec (1970). Cf. Lazarov, 1972. [Ovog puta kao idealan “instrumentarij”, oni su, izrazitom elastičnošću i tehničkom briljantnošću, izveli dela: Opomena Dalapikole, Rečitativ, ariju i varijacije Amija, Dodekameron Maleca i Noći Ksenakisa].

42 Obradović, 1972 [Dvanaest solista ovog kamernog hora (6 ženskih i 6 muških) raspolažu divnim glasovnim materijalima, homogenim i izvanredno ujednačenim, sa intonativnom perfekcijom koja zadivljuje […]. Imao sam utisak da slušam žive orgulje na kojima je vrsni i inteligentni umetnik, dirigent Marsel Kuro, izvlačio tonske boje kao da je menjao orguljske registre i manuale. Profinjeni smisao za krajnje različite stilske pravce (od renesanse do avangarde) odaje visoki profesionalizam i široko znanje].

43 Ibid. [[P]osvećena svim političkim zatvorenicima sveta!’].

44 For additional information about Aleksandar Obradović, see Janković-Beguš, 2017, p. 141–63.

45 Veselinović, 1974 [Logičnost sistema kao takvog, ne obezbeđuje uvek umetničku komunikativnost zvučnog rezultata, smisao i epitet umetničkog dela. Tada taj sistem ima samo vrednost po sebi. Ovaj problem bio je evidentan na ovogodišnjem prvom koncertu iz ciklusa Muzička moderna. Izvedene kompozicije […] postavljaju pitanje umetničkog dejstvovanja].

46 Ibid. [Delu Aroura za 12 gudača Janisa Ksenakisa, međutim, nedostaje i muzički izraz njenog–rečima samouvereno iskazanog—cilja: otkrivanje i ispitivanje zvučnih slojeva]

47 Ozgijan, 1974 [Jedna od zajedničkih osobina svih izvedenih kompozicija [...] jeste pomanjkanje osećanja mere o dužini kompozicije, pri čemu autori jednostavno ne vode računa o mogućnostima percepcije slušaoca. To se i ovaj put moglo uočiti [...] posebno u Ksenakisovoj Aroura (1971.), koja ne samo da zamara svojom dužinom već deluje još razvučenije i dosadnije usled stalnog ponavljanja istih kompozicionih postupaka].

48 Ibid. [Dirigent Boris de Vinogradov je u mnogim izvedenim kompozicijama sveo svoju ulogu na dobrog saobraćajca, prepustivši izvrsnim muzičarima da se sami snalaze u toj “saobraćajnoj“ gužvi].

49 Obradović, 1974 [Kompozicije poznatih nosilaca savremene moderne, Ligetija (Luks eterna – za mešoviti hor) i Ksenakisa (Medeja—za muški hor, četiri instrumenta i udaraljke), izazvale su utisak više kao cerebralne tvorevine, nago kao muzika koja bi se rado još jednom čula].

50 Ibid.

51 Lazarov, 1974 [Velika opreznost pri pristupu tumačenja moderne partiture proizilazi iz njene kompleksnosti. Ako se ne tumači u punom njenom obimu, naročito ako se dozvoli nepreciznost u tumačenju detalja, moderna partitura gubi u svojoj fleksibilnosti. […] [Na ovom koncertu] moramo konstatovati pomanjkanje detaljnog studiranja partitura, što se neminovno reflektovalo i na naš utisak o prezentiranim delima].

52 Ibid. [Najveće negativno iznenađenje, ako tako može da se kaže, predstavljalo je izvođenje dela Medeja za muški hor i pet instrumentalista Janisa Ksenakisa].

53 Ibid. [Pridržavajući se stare grčke instrumentalne i vokalne tradicije, a obogaćujući je pojedinim postupcima avangardnih principa komponovanja Ksenakis je napravio smešno, poptuno nekoherentno delo, koje će u njegovom opusu predstaljati ili prolaznu, trenutnu slabost i zabludu, ili zaokret u stvaralaštvu].

54 Babić, 1974, p. 27.

55 Ibid. [I na ovom koncertu […] ponovila se ona nevesela slika sa ranijih „priredaba“ muzičke avangarde. Malobrojna publika […] pozdravila je malokrvnim aplauzima kompozicije sa nazivima Tužbalica, Radosno opelo, Medeja, Sferoon i Luks eterna. […] [S]va ova dela [su] neobično slična i što se u njima zapaža samo lelek i kuknjava i neka ukočena strava. […] [U] svim ovim kompozicijama ponavljaju svega nekoliko tehničkih postupaka, koji ubistveno osiromašuju ionako neubedljiv sadržaj. Sva ova muzika deluje statično, ukočeno, zgrčeno, ili, katkad, panično i histerično].

56 Lazarov, 1978 [Ako je za Modernu, maksimalizacija serijalizacije i minimalizacija konstitucije karakteristika posle šezdesetih godina, tada su svi oni drugi pristupi emanacija nečega što se nalazi između toga, te se, u komparaciji sa prethodnim kategorijama, odnose ili sa pozicija neshvatanja prave suštine stvari (često i sa pozicija odsustva želje za shvatanjem)—stoga su u stanju da proizvode vulgarizacije manjeg ili većeg obima—stvarajući izomorfne oblike].

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid. [O upravo ovom, trećem pristupu (koji je na ‘pola puta,’ koji je negde između glavnih principa karakterističnih za način mišljenja Moderne) može biti reči kada se želi izvršiti nekakva klasifikacija dela izvedenih od strane Elizabete Hojnacke, inače klavsenistkinje sa izvanrednim smislom za tumačenje dela avangardne muzike (verovatno jedne od najuverljivijih koje smo uopšte čuli u Beogradu). To se pre svega odnosi na kompozicije Janisa Ksenakisa, Lika Ferarija i delimično na Fransoa-Bernara Maša]

59 Ibid. [Janis Ksenakis se i inače nalazi u procepu između totalne serijalizacije […] i amalgamizacije grčkih folklornih idioma. Khoai, delo za klavsen, međutim, kao da u ovom smislu potencira upravo te nedostatke Ksenakisovog stvaralaštva, nedostatke dovoljnosti korelacije između elemenata potrebnih za oformljenje. Tako se Khoai formalno razgraničava u dva dela: u prvom dominiraju elementi kvaziminimalističkog pristupa […] i izrazito— elementi grčkog folklora; u drugom (suprotno) evidentiramo neopunktualne elemente (no ne u Vebernovom smislu), svakako bliže atonalnosti. Ovakav pristup, u strukturalnom smislu ne pruža mogućnost obezbeđenja koherencije dela; ovo su mane i ranijih Ksenakisovih ostvarenja, one su se kao činjenica eksplicirale i u ovom].

60 This visit was made possible by the fact that in April 1985 Xenakis was the guest of the Muzički Biennale Zagreb (Music Biennale Zagreb), the oldest festival of contemporary music in ex-Yugoslavia (today in Croatia), together with several other world-known contemporary composers such as John Cage, Luciano Berio and Krzysztof Penderecki. Cf. Pešić, 1985. As observed by Ivana Medić, the entire cycle Muzika danas/Muzička moderna (which was renamed once again in its final year, 1985, as Musica viva) relied heavily on the program of the Music Biennale Zagreb, since the Radio Belgrade Third Programme did not dispose of financial resources to invite foreign performers and composers. See Medić, 2015, p. 142, 144.

61 Premate, 1985 [[Izvedene] kompozicije svojom ogromnom unutarnjom ekspresijom, izuzetnim tehničkim zahtevima, neobuzdanim tempermentom ostavile su gotovo bez daha i izvođače i publiku].

62 Ibid. [Koncert je bio i osmišljen u smislu razvoja jedne ideje i određenog stvaralačkog principa koji je, tokom izvođenja, izložen, pa razrađen u nekoliko varijanti, kulminirao poslednjom izvdenom kompozicijom].

63 Ibid. [Janis Ksenakis nas je, svojom muzikom, uverio da delo nastalo […] uz pomoć računskih operacija i matematičke logike, ne mora biti i neumetničko čak i ako je mereno klasičnim estetskim merilima koja se bave formom, jasnoćom, dramaturgijom, pa i samom kompozicionom tehnikom. Izvedena dela nisu ni jednog trenutka odala svoje matematičko, nemedijsko, poreklo. Čak, jasnom formom, uglavnom fragmentarnog oblika u kojoj svaki odsek predstavlja logičan nastavak i dramaturški razvoj celine, a pogotovu ogromnim akumulacijama energije i izvornog temperamenta, ove stohastičke kompozicije nose u sebi više živosti i vezuju pažnju u mnogo većoj meri od mnogih drugih, klasično komponovanih savremenih dela. Ipak, kako je Ksenakis pre svega stvaralac, pa tek onda matematičar i zaljubljenik u kompjutersku tehniku, na mnogim mestima u pariturama, vidljive su stvaralačke intervencije u odnosu na kompjuterski diktiran izgled dela. Očigledno je da se Ksenakis služi matematičkim programima i njihovom digitalnom nadgradnjom kao ‘materijalom,’ čak ne ni kao striktnom kompozicionom tehnikom i da mu je, nakon godina avangardnog eksperimentisanja i ispitivanja mogućnosti u okviru stohastike, najvažnija muzika].

64 Ibid. [Iznenadili su zvučni potencijali čembala koje je zvučalo kao moćna udaraljka, ksilofon, zvončići, zvona ili marimba, ili pak, kao elektronski generator].

65 Ibid. [U svojoj bogatoj stvaralačkoj fantaziji, Ksenakis je uspeo da ostvari zvuk, po boji gotovo identičan elektronskoj muzici, a ipak za razliku od većine dela sintetizovanih na generatoru, visokog naboja žive, opipljive ljudske emocije].

66 Pešić, 1985 [Usvojivši estetske postulate svoga uzora [Korbizjea], podređene […], formama mašinske civilizacije, kastriranih linija i kubusnih oblika, Ksenakis je nastojao da slične matematičko-projektantske radnje implantira u tkivo muzike].

67 Ibid. [Uobičajenim auditivnim načinom nismo mogli da otkrijemo žive ćelije muzike i njihovu prirodnu morfogenezu u zadatom vremenu […]. Kompozicije Naama i Koai za čembalo otkrile su do koje mere ovaj krhki instrument može biti deformisan agresivnošću klasterskog zvučanja. Bravurozno izvođenje Silvija Gualde, njegovo virtuozno snalaženje na raznovrsnim udaraljkama među kojima su bili i keramički ćupovi, nije umanjilo akustički teror, kao što ni zadivljujuća veština i komplementarnost njega i Hojnacke u delu Komboi nije sama sebi mogla biti dovoljna].

68 Ibid. [No, avangarda koja predugo traje, ne menjajući se, doživljava neminovnu fosilizaciju].

69 The concert took place within the program of the 7th International Review of Composers in Belgrade, at the Kolarac Foundation Hall. The program also featured works by other French contemporary composers (Mâche, Dutilleux, Prin, Dusapin, and Aperghis) and one piece by Petar Bergamo (1930–2022). Several years earlier, Xenakis’s piece Rebonds for solo percussion (1987–9) was performed by the Romanian percussionist Liviu Dănceanu at the 4th International Review of Composers in Belgrade, on 13 May 1995 at the Foyer of the Sava Center, within the concert presented by the Ensemble Archaeus from Bucharest which featured mainly Romanian contemporary music. More information about the International Review of Composers’ history and programming in Janković-Beguš and Medić, 2020, p. 139–68.

70 Apart from the already mentioned, Xenakis’s pieces were performed three more times within the International Review of Composers after the composer’s death: Akea for piano and string quartet (1986) on 12 May 2002 at 7:00 PM, Kolarac Hall (Ensemble Avantgarde, Germany), Waarg for thirteen musicians (1987–8) on 15 November 2009 at 8:00 PM, Kolarac Hall (Klangforum Wien, Austria, Conductor Emilio Pomárico), and Theraps for solo double bass (1975–6) on 7 October 2016 at 5:30 PM, National Bank of Serbia (Goran Kostić, Serbia). Most recently, Serbian percussionist Darko Karlečik performed Rebonds B: the concert took place on 2 September 2022 at 8:30 PM at the District Music Stage in Novi Sad.

71 For instance, the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra, as arguably the best orchestral ensemble in Serbia, has never performed any of Xenakis’s works.