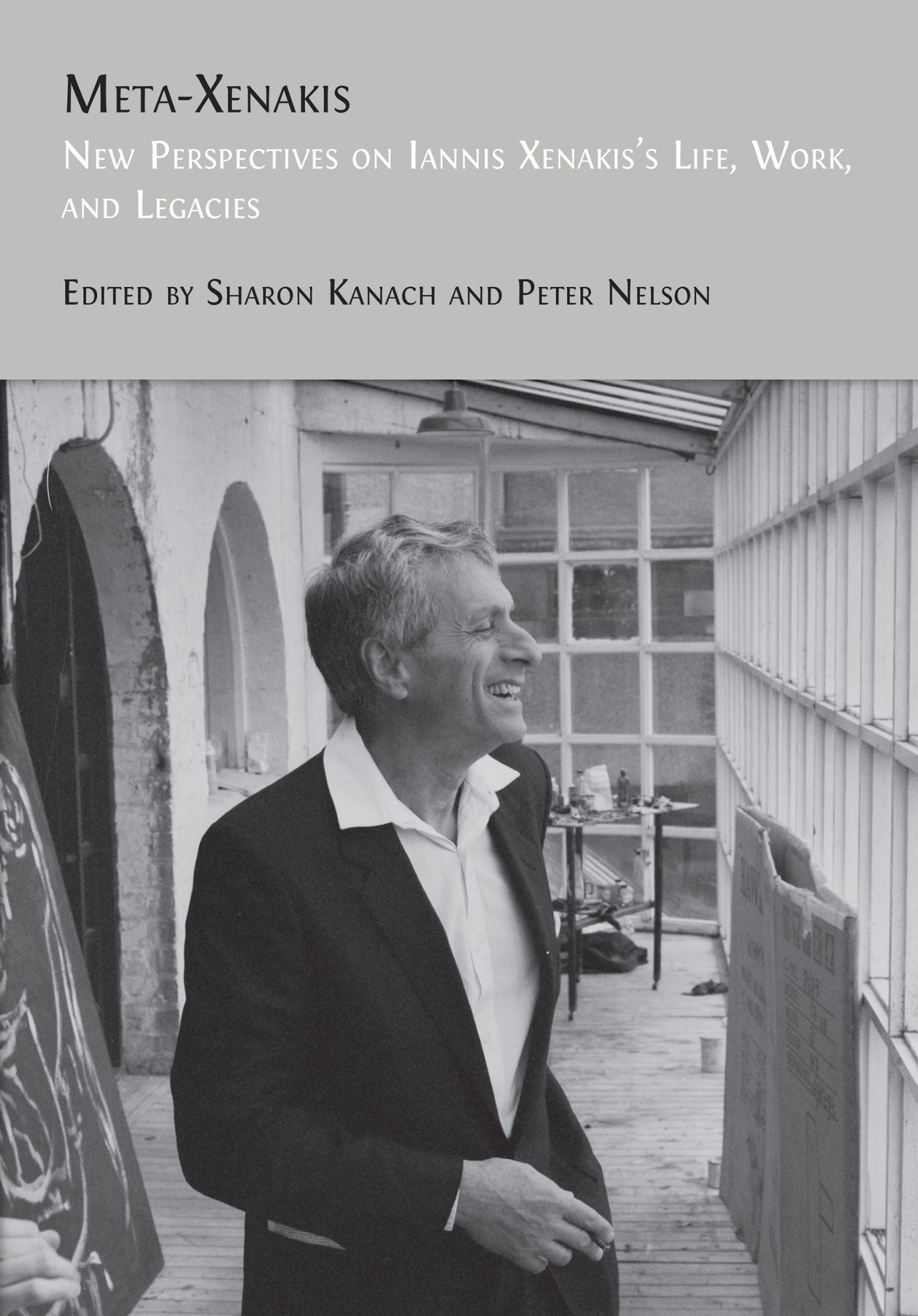

5. Iannis Xenakis in Japan: Productive Performances and Reception of Texts

Mikako Mizuno

© 2024 Mikako Mizuno, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.07

Introduction

This text was given as an introduction to the lecture-concert presented by Yasuko Miyamoto (b. 1970) on 1 October 2022, in Nagoya, as part of the Japan team’s contribution to the Meta-Xenakis Symposium, and offers a short description of Japanese performers who contributed to the reception of the work of Iannis Xenakis in Japan. This overview covers only a few performers, but it demonstrates their important impact on the music scene in Japan to this day.

Over the last two decades several excellent younger players of Xenakis’s work have emerged. They were all born in Japan and are establishing a new phase of Xenakis performances in Japan. They succeed the first generation of performers, who had shared with Xenakis the same years of the cultural avant-garde period after World War II.

We can say that the years between 1960 and the early 1970s generated the first phase of Xenakis’s reception in Japan, and that the second phase encompasses the period from the 1990s until the present day.

First Generation, First Phase

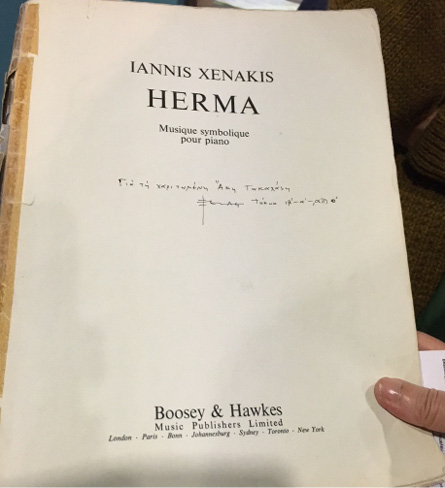

The first generation of Japanese Xenakis performances were led by Yuji Takahashi (b. 1938) and Aki Takahashi (b. 1944), who presented Xenakis’s piano works, as well as, for the former, his texts on philosophical and mathematical theories. In February of 1962, Yuji Takahashi premiered Herma (1961) in Tokyo, which the pianist had commissioned directly from the composer. Takahashi wrote about the process of commission and the piece:

I first met Xenakis when I played Takemitsu’s Piano Distance at a Sogetsu Art Center concert [in 1961]. Later, at the recommendation of Kuniharu Akiyama [1929–96],1 I wrote a letter to Xenakis and commissioned a piano piece from him. The piece I received was Herma. It took thirty days of practice, dividing it into small sections, because the piece jumps all over the keyboard. The younger generation of pianists later criticized me if I played these rhythms incorrectly. But the score, by using a grid of 1/5 and 1/6 of the probability-calculated time of occurrence of the notes, vaguely reflects music that cannot be written in regular rhythms. My hands and fingers playing those phrases bring out unexpected music. Two layers of sound are simultaneously heard: a slow-moving surface and a fast-scattered line.2

Takahashi played as soloist for the world premiere of Eonta (1964) in December 1964 in Paris with Pierre Boulez (1925–2016) conducting, and played that same piece in the project Orchestral Space on 4 May 1966, at Nissei Theater (Tokyo) with the brass players of Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra.3 The project Orchestral Space was planned and designed by Tōru Takemitsu (1930–96) and Toshi Ichiyanagi (1933–2022). It was one of the big series of contemporary music events which were held in the 1960s to introduce and promote cutting edge Western compositions.4 Notably, 1966 was the year Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) came to Japan and created Telemusik (1966) and Solo (1966) in the NHK electronic music studio. Stockhausen gave a lecture, including an introduction to the concept of stochastic music, but there was no information in Japan about the theory of Xenakis’s stochastics until 1975 when Yuji Takahashi translated and published parts of Xenakis’s Music and Architecture.5 In the 1970s Yuji Takahashi translated some other texts by Xenakis and published some articles in the magazine TRANSONIC, among others.6

The first collaborations between Xenakis and Japanese musicians culminated in the Osaka World’s Fair (1970) and the preparatory process of Hibiki-Hana-Ma (1969–70) in the NHK’s electronic music studio. This experience made important footprints not only on musical concepts among Japanese contemporary composers but also on collaborative teamwork between musicians and engineers of electronic music.7

Also, Evryali (1973) and Herma (1961), as well as the Japanese premiere of Synaphaï (1969), all played by Yuji Takahashi in the 1970s, were so fascinating that many young and future Japanese musicians became determined to proceed to study and research Xenakis and his theories, and strived to attain the level of virtuosity required to perform his music.

For example, the percussionists Sumire Yoshihara (b. 1949), Yasunori Yamaguchi (b. 1941), and Jun Sugawara (b. 1947) should be mentioned as part of the generation that was inspired by those early exposures to Xenakis’s music. All of them have included Xenakis’s percussion works in their repertories. In turn, they themselves made recordings which have become the established models for Japanese contemporary percussion performance.

Yoshihara’s performance of Psappha has also been highly influential because she, like Yamaguchi, has been a professor in music colleges and universities in Japan. In the workshop organized around Xenakis, after having been awarded the Kyoto Prize on 12 November 12 1997, Yoshihara played Psappha (1975) in celebration of Xenakis.

In 1988, Jun Sugawara held a concert entitled “Sound of Xenakis and Yuji Takahashi.” The program was composed of works by Xenakis (Persephassa (1969), Psappha (1975), Dmaathen (1976)) and by Yuji Takahashi (Lullaby for marimba (1985) and Wolf for percussion (1988, world premiere)).

Pianists Following Takahashi

In the 1990s, the second generation of pianists took on the challenge to perform recitals featuring the music of Xenakis, Stockhausen, Boulez, and György Ligeti (1923–2006). Leaders of this new generation of pianists included Hiroaki Ooi (b. 1968) and Hideki Nagano (b. 1968).

Hiroaki Ooi started his career as a self-taught pianist and is now a multi-keyboardist. In July of 1996, Hiroaki Ooi received attention when he played and recorded the piano solo for Synaphaï, with the Japan Philharmonic, with Michiyoshi Inoue (b. 1946) conducting.8 At that time, Ooi was the youngest Xenakis performer in Japan. Three concerts conducted by Michiyoshi Inoue were held in Tokyo and Kyoto featuring Synaphaï with Ooi. The performance in Kyoto was recorded, and Xenakis received this recording via his publisher Salabert. As Xenakis listened to the recording, he said that Japanese musicians are interesting because they play “so precisely.”9 Xenakis’s principal publisher, Salabert, used that recording as an exemplary reference of Synaphaï for promotional purposes for many years.

In 2001, Ooi received the Idemitsu Music Award10 and performed the Japanese premiere of Erikhthon (1974) with the Tokyo City Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Tatsunori Numajiri (b. 1964). Ooi played Synaphaï for a recording with Arturo Tamayo in 2002, and in 2004 he was featured in Tamayo’s recording of Erikhthon, both with the Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra and released on the Timpani label.11

In the booklet Salabert published to commemorate the 10th anniversary of Xenakis’s death in 2011, Ooi composed Oser Xenakis (Daring Xenakis):

Before tackling Synaphaï, it is necessary to go through his three solo piano pieces carefully. […] The more training you have, the more you may be frustrated that you cannot play the music at sight, and that it is far removed from the academic conservatory style.12

Ooi played all of Xenakis’s solo piano pieces in a concert titled “Portraits of Composers #6” on 23 September 2011, in Hakuju Hall in Tokyo. And in 2022, he played the Japanese premiere of Keqrops (1986) with the New Japan Philharmonic conducted by Michiyoshi Inoue.

The Summer Festivals and the Prize by Suntory Foundation for the Arts

The millennium successors had experienced several important Xenakis events in Japan in their younger days, such as the world premiere of Horos (1986), commissioned by Suntory Hall. The Suntory Hall International Composition Commission Series was a project through which Suntory Hall commissioned new orchestral pieces from leading composers selected by the music director, Tōru Takemitsu (1930–96). The selected composers themselves would be in charge of selecting works, responding to prompts including “works that have influenced me” and “young composers I am paying attention to.” In 1986, Xenakis was selected for the second concert of the series, for which he composed Horos and where Olivier Messiaen’s (1908–92) Chronochromie (1960) and François-Bernard Mâche’s (b. 1935) La Peau du silence I (1962) were also featured. That concert was performed by the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Hiroyuki Iwaki (1932–2006).

In 1997, there was a celebration concert for Xenakis who won the Kyoto Prize that year, and the Suntory Summer Festival thematized Xenakis, and featured two nights of Xenakis’s work.13 The first night included: ST/4 (1956–62), Jalons (1986), Phlegra (1975), Tetras (1983), and Persephassa (1969).14 The second evening was an orchestral concert with the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Hiroyuki Iwaki, playing Syrmos (1959), Synaphaï, ST/48 (1962), and Kyania (1990). This time, the solo pianist in Synaphaï was Hideki Nagano (b. 1968), who had been a member of the Ensemble InterContemporain since 1995.

In 2012, the Suntory Summer Festival produced its original production of the complete staging of Xenakis’s Oresteïa. The Oresteïa was first staged in Japan as a suite for mixed choir in 1976 at Nissei Theater (Tokyo), which was conducted by Yuji Takahashi. In the program pamphlet, Takahashi wrote about the universe and music of Xenakis:

The kernel of Xenakis’s music and his thought can be said to liberate man from the wheel of destiny into which he is thrown. Science, history, and culture are all tools for this journey of the human spirit, and the artist, as the freest in the realm of the intellect, assumes the role of pilot to carry out this mission.15

Xenakis started to compose his Oresteïa in 1965 and completed it in 1966 in Japan, where Xenakis stayed in our country for a short time. In 1986, Kassandra, and in 1992, La Déesse Athéna were composed, both of which include solo voice. In 2012, Horos was selected by Toshio Hosokawa (b. 1955), who was then the music director for the series. It was the second performance of Horos in Japan in Suntory Hall, which was realized by Kazuyoshi Akiyama (b. 1941) and the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra.

In 1992, the 15th concert of the Suntory Hall International Composition Commission Series, for which José Maceda (1917–2004) was selected, featured Maceda’s new piece Distemperament (1992), Edgard Varèse’s Intégrales (1924) and Xenakis’s Kyania (1990), as well as Yuji Takahashi’s Thread Cogwheels (1990). Intégrales is, as Maceda asserted, responding to the prompts indicated above, the “work that has influenced me” and stated that Xenakis and Takahashi are the “young composers I am paying attention to.”16 All four pieces were performed by the New Japan Philharmonic conducted by Yuji Takahashi.

The baritone, Takashi Matsudaïra (b. 1963), known as a specialist of Stockhausen, applied his marvelous voice in this 2012 production of Xenakis’s Oresteïa. Takashi Matsudaïra wrote a minute analysis about the écriture of Xenakis on his website.17 The stage sound plan was designed by Sumihisa Arima (b. 1965). Sumihisa Arima is the key person for today’s electronic staging in Japan, and he worked as the sound designer and operator also for Xenakis’s Persépolis (1971) produced in Akiyoshidai in 2020.18 Persépolis in Akiyoshidai was an open-air, electroacoustic performance, and with the contribution of Arima and the lighting designer Tomomi Adachi (b. 1972). This concert was awarded the Saji Keizo Prize from the Suntory Foundation for the Arts.

The Year of Xenakis’s Centennial

In 2022, there were several concerts prominently featuring Xenakis as a celebration of the centennial of his birth. For example, musicians and ensembles like Quartiers Musicaux, Trio à Cordes de Pointe, Izumi Sinfonietta, Ichiro Nodaïra (b. 1953) and the Arditti Quartet. Also the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra featured a special concert including the Japanese premiere of Xenakis’s piano concerto Keqrops, featuring pianist Hiroaki Ooi, conducted by Michiyoshi Inoue. The percussionist, Kuniko Kato (b. 1969), produced a concert titled Xenakis and Dance in SAïTAMA. The Suntory Summer Festival had a day titled 100% Xenakis. The musical group Nymphe Art had a concert which focussed on Xenakis. Kunitachi College of Music produced a special event titled transmitting/transmitted by hearing.

Yasuko Miyamoto and Sumire Yoshihara

After graduating from the department of music of Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts, Yasuko Miyamoto went to Germany and graduated from the Freiburg College of Music’s soloist course in 1999.

When she encountered Xenakis’s score of Psappha, she was shocked because she did not know how to interpret its notation. She took two months to rewrite by herself the seemingly graphic notation of Psappha into a more traditional type of musical score. Miyamoto has been deeply impressed by Yasunori Yamaguchi and Sumire Yoshihara concerning their performance styles in contemporary music. And it was Sumire Yoshihara who directly showed her how to perform Psappha.

Under the influence of Yamaguchi and Yoshihara, Miyamoto studied Zyklus (1959) and Kontakte (1958–60) by Stockhausen and works by Luc Ferrari (1929–2005). In Freiburg, Miyamoto also challenged a wider variety of repertories19 under Professor Bernhard Wulff (b. 1948).

In Europe, she played as a member of Ensemble Charis (Zurich), YMMO Ensemble (Freiburg), and performed as a guest player for Ensemble Recherche (Freiburg), Musikfabrik (Köln), Radio Symphony Orchestra Stuttgart, Sinfonieorchester Basel, and Bremen Philharmonie.

In contrast to Stockhausen’s pieces, in which performers have the heavy duty of interpreting many indications concerning how to use the mallets, or the necessity of needing to memorize the tape sounds, Xenakis’s pieces, Miyamoto says,20 give performers free choices, which demand a performer’s own imagination.

For example, in Rebonds B (1987–9), the composer indicates at places to play “wooden instruments.” So, Miyamoto tried with wood blocks. But she had to abandon simply playing wood blocks because it is impossible to play pianissimo tremolo with normal wood blocks. Her teacher, Sumire Yoshihara, put several rubber bands on the wood blocks which muted them. Miyamoto realized that performing Xenakis should mean finding a way to create timbre. Again, it demands the performer’s imagination.

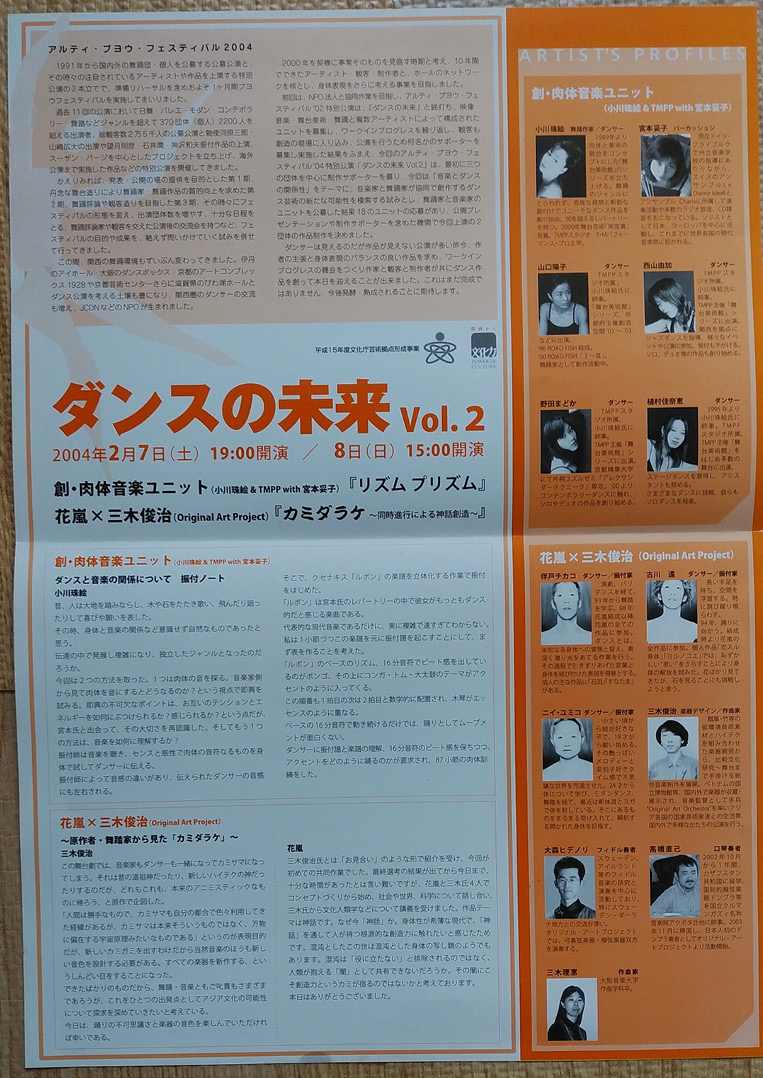

As an example, this video linked in this footnote starts with excerpts from Rebonds B performed by Yasuko Miyamoto and the dancers Tamae Ogawa & TM Performance Professional (TMPP).21 Okho (1989) follows with Mitamoto’s short explanation about the instruments.

Rebonds B and accompanying dance was recorded in February 2004 in Kyoto Arti Hall, which was a part of the Arti Dance Festival 2004. Their performance was titled “Sozo Kukan, Dance no Miraï vol.2” (Space for Creation, Dance in the Future vol.2).

The dancer/choreographer Tamae Ogawa22 made a table of rhythms from the score of Rebonds B as a choreographic notation. Keeping to the beat of the semiquaver, the dancers responded to the musical accents and made interesting movements.

Concerning this video recording of Okho, Miyamoto herself talks about how she and her collaborators approach timbre in Xenakis. For the performance recorded in the video they used three sets of multi-percussions, replacing the three djembes called for in the score, and various sticks: long and heavier sticks, mallets for timpani, beaters for bass drum, rubber tipped mallets, hand-made sticks with rubber to be handled, cooking chopsticks etc. In the twenty years of her activities as a percussionist, Miyamoto has performed all of Xenakis’s percussion solo and ensemble pieces in Europe and Japan. Miyamoto indicates in the video that she found a phrase in Rebonds A which appears also in the last part of Okho. She feels quite excited when that phrase appears.

Fig. 5.1 Flyer for “Dance no Miraï” (Dance in the Future), 2004. © Tamae Ogawa, reproduced with permission.

Conclusion: Beyond the Centennial in Japan

In Xenakis’s centennial year, Japanese players had more opportunities to perform his works than ever before. Some of the concerts seemed to provide new encounters with Xenakis’s music for younger musicians. For example, the concert realized by the Kunitachi College of Music on 1 October 2022 featured Achorripsis (1957), Anaktoria (1969), Echange (1989), O-Mega (1997), and two special concerts for La Légende d’Eer (1977), which attracted young audiences who filled up the concert venue and provided a great educational experience. The Tokyo University of Arts held a symposium and concert on 4 December 2022. The concerts included performances of Kottos (1977), Nyuyo (1985), Khal Perr (1983), Kassandra (1987),23 and Waarg (1988). Both concerts revealed several excellent performances of Xenakis by very young players. Both the players and the audience were enthusiastic, which is not the case in most contemporary music concerts these days in Japan! For the players, performing Xenakis’s work is a great and challenging task. Rewriting scores, physical training to become familiar with the use of the instruments, or preparing for the performance (including memorization) seem to be difficult—but worthwhile—goals for the players to overcome, as a Japanese bassist, Yoji Sato (b. 1979) said in an interview with the author.24 We will certainly witness many more performers and performances of Xenakis’s music in the near future in Japan.

Fig. 5.2 Autographed score of Herma by Xenakis to Aki Takahashi: “To dearest Aki Takahashi, Tokyo, January 12, 1970.”25 Reproduced with permission from the dedicatee.

References

BARTHEL-CALVET, Anne-Sylvie (ed.) (2011), Oser Xenakis, Paris, Durand-Salabert-Eschig, https://issuu.com/durand.salabert.eschig/docs/oser_xenakis_fr

KAKINUMA, Toshie (1992), “The 15th Suntory Hall International Composition Commission Series,” Ongakugeijyutsu, vol. 50, no. 9, p. 84–5.

LUXEMBOURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA, OOI, Hiroaki, and TAMAYO, Arturo (2007), Iannis Xenakis: Orchestral Works Vol. 4—Erikhthon, Ata, Akrata, Krinoidi, Paris, Timpani.

TAKAHASHI, Yuji (1976), “Sotogawa karano shiten” (program pamphlet), Nissei Theater.

XENAKIS, Iannis ([1975] 2017), Ongaku to kenchiku (Music and Architecture), edited and translated by Yuji Takahashi (rev. ed.), Tokyo, Zen-On Music.

1 Kuniharu Akiyama was the husband of Aki Takahashi, and a well-known music critic as well as a sound artist associated with the Fluxus movement.

2 Yuji Takahashi, “Who – Where –, no.2 Iannis Xenakis,”

https://www.suigyu.com/yuji/ja-text/dare_doko1-11.html#xenakis (translation by the author).3 The concert featured: Sosokusonyu by Joji Yuasa (b. 1929), AMBAGES by Roger Reynolds (b. 1934), Eclipse by Tōru Takemitsu (1930–96), The Wonderful Widow of 18 Springs (1942) by John Cage (1912–92), and Eonta (1963) by Iannis Xenakis.

4 The others are: Sogetsu Art Center Contemporary Series, Contemporary Music Festivals of Nijyusseiki ongaku kenkyujyo (research institute of twentieth-century music) and the Contemporary Music Festival of Autumn of Osaka. Takahashi premiered Herma at a concert as part of the Sogetsu Art Center Contemporary Series.

5 Xenakis, [1975] 2017.

6 For example, a translation of the ninth chapter of Formalized Music, in the fourth volume of the magazine TRANSONIC, or Chi no senryaku Xenakis no baai (Strategy of Knowledge in the Case of Xenakis), Eureka, April 1974, in which Takahashi explains and summarizes Xenakis’s theory of stochastics, combination, and sieves as an intellectual strategy.

7 See Chapter 17 in this volume for more information on this subject by the same author.

8 This performance can be viewed here: PTNA, “Xenakis ‘Synaphai’ Ooi/Inoue/NewJapanPhilharmonic” (18 September 2018), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rZYN4kdorVQ

9 Takuo Ikeda, “Japan Premiere of Xenakis’ ‘Cecrops’!” (10 February 2022), TPO,

https://www.tpo.or.jp/information/detail-20220210-01.php (translation by author).10 Ooi was awarded the “Best young musician of the year” with a strong recommendation by Takahiro Sonoda (1928–2004), who was a member of the jury of the Messiaen International Competition.

11 Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra, Ooi, and Tamayo, 2007.

12 Barthel-Calvet, 2011, p. 7.

13 The text of Xenakis’s acceptance speech can be read both in Japanese and in English at:

https://www.kyotoprize.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1997_C.pdf14 Norio Sato (conductor), Ensemble Nomade, Alberi String Quartet; percussion: Jun Sugawara, Toshiyuki Matsukura, Takafumi Fujimoto, Kyoko Kato, Daiji Yokota, and Yu Ito.

15 Takahashi, 1976. Program pamphlet translated by author.

16 José Maceda quoted in Kakinuma, 1992, p. 84–5. Although Xenakis was seventy years old and Yuji Takahashi was sixty-two years old in 1992, Maceda, at seventy-five years old, was still their elder, and therefore viewed them as “young composers”!

17 Takashi Matsudaira, “Writing for the Baritone Solo in Xenakis’s ‘Oresteia,’”

http://matsudaira-takashi.jp/analysis/oresteia/18 “Persepolis: Tape Music Played at Akiyoshidai,” Akiyoshidai International Art Village,

https://aiav.jp/13357/19 “Information: 2001,” Yasuko Miyamoto,

http://www.yasukomiyamoto.com/information/2001.html20 In an online interview with the author (18 April 2022).

21 Mikako Mizuno, “Yasuko Miyamoto, Meta-Xenakis,” Vimeo,

https://vimeo.com/802224852/1e49632017?share=copy. Recorded at Shokeikan Hall of Doshisha Women’s College, Kyoto, on 5 September 2002. Recording provided by Masanori Kasai and Kazuko Narita.22 Tamae Ogawa started a dance project named “Butai Bijyutsukan” (Performance Museum) in 1989. Since then, she has been actively creating dance workshops in collaboration with contemporary artists: musicians, visual artists, stage designers. In 1996, she founded her company TMPP and produced several performances: Kyoto City Art Festival, Kyoto Sozo Kukan projects 2001/2002/2003/2004/2005, the 40th anniversary ceremony of the EXPO’70 world exhibition, the 26th National Cultural Festival, etc.

23 The countertenor Toshiharu Nakajima’s performance was powerful. Nakajima (b. 1986) received the Bunkacho Prize of 2022 for young artists.

24 25 September 2022, at Aichi Art Center.

25 This date is two days after Xenakis’s arrival in Osaka for work on Hibiki-Hana-Ma. See Chapter 17 in this volume.