50. The Iranian Context of Iannis Xenakis’s Persepolis

Aram Yardumian

© 2024 Aram Yardumian, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.52

In this chapter, I will be running through some details to help better understand the premier of Iannis Xenakis’s work Persepolis (1971). This is also the subject of my recent book, and obviously, there is a lot more detail in the book than I have time for here, but what I can do is to offer a sketch of what can be found in the book.1

I want to clear up a popular misconception. A surprising number of books and articles imply that Persepolis was premiered at the infamous 2500th anniversary celebration of the founding of the Persian Empire. It was not. It was, in fact, premiered at the 1971 Shiraz Arts Festival, which was held in conjunction with the infamous event, but was a month earlier. The Shiraz Arts Festival was an international festival held between 1967 and 1977 at the initiative of the Empress, Farah Pahlavi. And the idea of this festival was twofold: one, to introduce Iranian audiences to Western music, and also to showcase lesser-known performing artists from within Iran. The Empress sent out emissaries around the country and found musicians and puppeteers and theater artists and referred to this gathering of Iranian unknowns as “an embarrassment of riches.” All of this was presented in Iran alongside John Cage (1912–92), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007), Bruno Maderna (1920–73), playwright Robert Wilson (b. 1941)—some pretty avant-garde material being presented in Iran in the 1960s and 1970s.

Xenakis participated three times at the Shiraz Festivals: first in 1968, with Nuits (1967) an a cappella vocal work made up of syllables from Mycenæan, Sumerian, and Persian texts; again in 1969 with Persephassa (1969) for six percussionists; and a third time in 1971 with Persepolis. In the preface to the Nuits score, Xenakis makes an overtly political gesture with his dedication to “disappeared” political prisoners. This was a bold move to make at a time when Iranians who opposed the Shah were routinely being maimed and killed by the secret police. These names, when you research them, yield basically nothing. They were real people, but I think Xenakis chose them not for their being celebrity political prisoners, but precisely because they were obscure people.

At the time, opposition to Mohammad Reza Shah (1919–80) was increasing and some five thousand SAVAK (the secret police) agents were out on the streets hunting dissidents and torturing them in secret facilities, as well as acting as media censors. SAVAK had tremendous power and were feared, especially in Tehran. At the same time, bribes were part of the Iranian general economy and the Shah’s family made hundreds of millions of dollars each year with money flowing upward. The conditions for revolution were ripening, and ultimately, one of the reasons the Revolution was so successful was that ultraconservative clerics and leftists both opposed the Shah and united, so groups on all sides of the political spectrum, who were otherwise ideological enemies, came together to fight a common enemy—the Shah.

In the eyes of the leftists opposed to the Shah, the Shiraz Festivals and the 2500th anniversary party in 1971 represented the widening gap between rich and poor. For the clerics it represented signs of moral degeneracy. The festivals, it has been argued, contributed something to the final downfall of the Shah. Few were saying such things in public—after all, the Shah and SAVAK controlled the press—but people were saying it.

Despite Xenakis’s small, anti-authoritarian gesture in the preface to the score of Nuits, he received two more invitations to premier work at the Shiraz Festivals. Persephassa in 1969 was held at the Persepolis archaeological site, which had been the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Persephassa is a percussion work for six players who are positioned in a hexagonal formation surrounding the audience. I think that is important because it tells us that Xenakis had seen the potential of the landscape, architecture, and acoustic dynamics, and was thinking about what perhaps he could do there if he was invited again.

He received an official invitation from the organizers of the Shiraz Festival to participate a third time, in 1971. That year’s events would be different than before, as they would be held on the same year as the 2500th anniversary celebration of the founding of the Persian Empire. Accordingly, the organizers asked Xenakis to develop a son et lumière (sound and light show) for premiere at the opening of the 1971 Shiraz Festival and this would be held at Persepolis on the night of 26 August. This time he would expand the range of action out from the site itself into the hillsides and the Naqsh-e Rostam, which is the necropolis where the lineages of Darius and Xerxes are buried. This is part of what would get him into trouble.

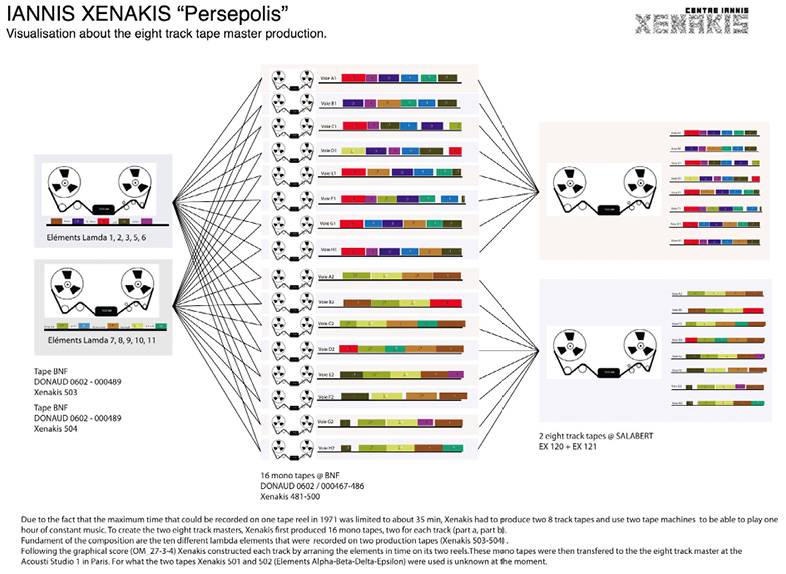

Persepolis was certainly the most technically complex sound-assembly process Xenakis had undertaken to date. He began by collecting found sounds, some (but not all) of which he identifies in the sketch plan for the work. We do not know what they all are. They include ceramic wind chimes, a Japanese gong, wind, an airplane (“jet”), timpani rolls, clarinets, strings, and the sounds of cardboard being folded. The rest we cannot identify, but maybe it does not matter because they do not have independent lives since they all blend into the whole of the work. The score for this piece was almost as painstakingly assembled as the work itself. On graph paper, Xenakis carefully pasted measured paper strips representing the sequence of the objets sonores, which he called “lambda elements.”

|

1 |

Jet |

|

2 |

Strings |

|

3 |

Clarinet |

|

4 |

⸻⸻ |

|

5 |

Urn (ceramic) |

|

6 |

“Carton” (i.e., cardboard being folded?) |

|

7 |

Japanese gongs |

|

8 |

Wind |

|

9 |

Timpani rolls |

|

10 |

Japanese cymbal |

|

11 |

Ceramic wind chimes |

Table 50.1 The ten identified “lambda elements” in Persepolis (note that Xenakis “missed” number 4).

The character of some of the elements (e.g. “jet”) and their positions were noted on the graph paper. While each always lasted the same length of time, he avoided repetitions by varying the attack point or by using different sections of the same material.

Below is another rendering of the “score.” One can see the “lambda elements” arranged in sequence to form the layers of the sound mass.

Fig. 50.1 Daniel Teige’s rendering of the eight-track tape master of Persepolis, composed of the ten “lambda elements.” Teige, 2012, reproduced with permission.

In physical rather than conceptual terms:

This music corresponds to a rock tablet on which hieroglyph or cuneiform messages are engraved in a compact, hermetic way, delivering their secrets only to those who want and know how to read them. The history of Iran, a fragment of the world’s history, is thus elliptically and abstractly represented by underground currents of sound.2

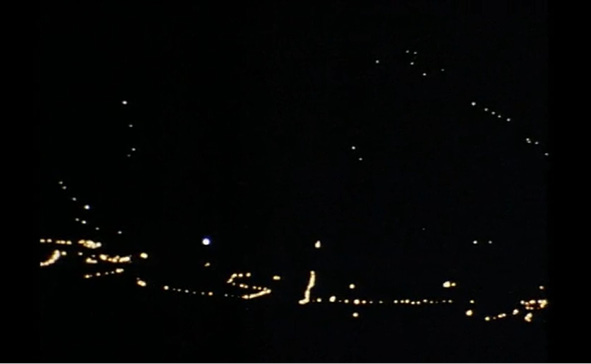

The event began at 8:00 PM on 26 August. The nearly one-hour son et lumière was touched off as Xenakis spooled the first reel of Persepolis. There was also a prelude with another of his electroacoustic works, Diamorphoses (1957), but the real event touched off with Persepolis itself, which was broadcast on fifty-nine multi-channel speakers distributed throughout the six contiguous listening areas in the ruin. In each such “room” either eight or more speakers were distributed. Each set of speakers broadcast one track of the eight-track recording of Persepolis to a standing audience. As the music began, the hillsides above the ruin were engulfed in light. Two gigantic gasoline bonfires were ignited at the Naqsh-e Rostam necropolis, with additional light from battery-powered car headlamps, pointed skyward, and from red laser beams sweeping across the ruins. Then several groups of Shiraz schoolboys, about one hundred and thirty in all, gathered with torches at the base of the hillside. In view of the listening audience, they climbed to the summit of the hill, in the direction of the fires, and stood, forming an outline of light between the crest and the sky. A Franco-Swiss documentary film on Xenakis by Pierre Andrégui, released also in 1971, includes footage of parts of the event.3 Below is a still from that film of the schoolchildren carrying torches up the hill in the dark.

Fig. 50.2 Still from P. Andrégui’s film Xenakis (1971) of torch-bearing schoolchildren from Shiraz spelling out “We Bear the Light of the Earth” in Persian during the Persepolis Polytope, 26 August 1971.

Response to the Shiraz Festivals in general and to Persepolis in particular is important here. Newspaper articles following the event mostly described it in negative or ambivalent terms. Amir Taheri’s 28 August review in Kayhan is one example of this, but there were several others.4 This one was interesting because it mentions the placement of the bonfires at the Naqsh-e Rostam, which is reputed to have been the place where Alexander’s troops entered Persepolis to complete their conquest of the Persian Empire. And thus, according to him, here comes another Greek to burn down Persia!

This theme was also taken up at a contentious roundtable discussion with students a few days after the event. Xenakis and his supporters tried to explain that the fire and lights represented the Zoroastrian values of eternal life and the triumph of good over evil, and the children themselves represented the carriers of these values into tomorrow—a cry of hope for the future. But one has to wonder how many of those children went on to participate in the Revolution? Others lambasted the music itself, saying it simply could not even be evaluated as good or bad because “its meaning is the one arbitrarily chosen by its maker.” Someone else decried this lack of symbolic meaning, saying, “It could have been presented as an homage to a sausage factory.”

It did not help that Xenakis, unlike Stockhausen and the others, had a direct connection to the Empress, and thus with the court of the Shah himself. For this reason, Xenakis received some of the most serious criticisms, not from Iranian journalists, but rather from Iranian expats in Paris who had the ability to speak freely in the press. They openly characterized the Shah as an oppressive dictator and abuser of human rights. Persian-French artist Serge Rezvani (b. 1928) published a letter in Le Monde on 24 November 1971 in which he asked how Xenakis (and Peter Brooks) could “actively be taking part in the happening of Persepolis and endorse it” when Asadollah Alam (1919–78), the Iranian minister of the Imperial Court, had supposedly publicly declared that “the peasants must even sell their blankets in order for the festivities to take place.”5 It is ironic that Persepolis became, if briefly, a symbol for that which Xenakis spent his life fighting against. It must have been painful not just to be generally misunderstood, but to be misperceived as standing for the opposite of his beliefs. In 1976, Xenakis officially cut ties with the Iranian regime, citing the political impossibility of continuing, and thus ending the chance of appearing at the next Shiraz Festival, and designing an arts center with funding from the empress.6

Among those taking notice of the festival programming was Khomeini. In 1977, while in exile in Najaf, he preached to a crowd of followers, “You do not know what prostitution has begun in Iran. You are not informed: the prostitution which has begun in Iran and was implemented in Shiraz—and they say it is to be implemented in Tehran, too—cannot be retold. Is this the ultimate—or can they go even further—to perform sexual acts among a crowd and under the eyes of the people?” Khomeini is referring here to Pig, Child, Fire, an Artaud-inspired play performed by the Squat Theatre, a Hungarian theater company, that featured, in its Iranian iteration, a forced sexual encounter, but without nudity.

By the time revolutionary activity got fully underway, leading to the permanent ousting of the royal family in January 1979, no one was talking about the Shiraz Festivals or the 2500th anniversary anymore. So much had happened in the meantime. But it could be argued that they were fertile ground for the seeds of anger to be sewn.

Fig. 50.3 Author’s book cover of Iannis Xenakis’s Persepolis (2023), London, Bloomsbury. CC BY-NC-ND.

*******************

The following is a transcript of the exchange that took place after the presentation of a version of this this paper at the second, Xenakis Project of the Americas (XPA) leg of the Meta-Xenakis Global Symposium Marathon that took place at the William P. Kelly Skylight Room (9th floor), The Graduate Center, the City University of New York (CUNY), 365 Fifth Avenue (at 34th Street), New York City, on 30 September 2022.

Questions

Carey Lovelace: Thank you so much for that. There were so many interesting points you brought up. We did a restaging of this in Los Angeles 2010 and the thing that was so impressive to me that I had never realized about Xenakis’s work, even though I had studied with him a little bit and had done these events around his music, was the sheer physicality of the sound.7 Those 50+ loudspeakers with people wandering through, and it wasn’t just a musical or sound experience, it was a primal dip into the history of Greek drama, so I was really surprised when you were talking about the sausage factory. It seemed more assaultive, in a good way, and I was wondering whether there was any commentary about the music itself, which is, more than other things I’ve heard, gets to this elemental nature.

Aram Yardumian: There were other comments. The way Amir Taheri characterized it in Kayhan International was meant to be demeaning but it was also accurate. I don’t have the phrasing in my memory now, but he described it as a mass of sound, like jets and wind, and he was correct in that, but he didn’t intend for it to be purely descriptive, he intended it to be a takedown. So, there was some description of the sound art itself, yes, but none of it was very positive… which is interesting because Stockhausen had been there. And there were others in the press who came out and said that it was a mistake to have these avant-garde composers at the Festivals because, as they said, we were just beginning to listen to Bach; Stockhausen was impossible.

James Harley: Great to meet you in person! I’m following up on what Carey was talking about. I’m just wondering, with such a huge sound system, and knowing Xenakis is famous for really, really loud playback of his work, and it would have been overwhelming. It’s funny that no one was commenting on that. It leads me to wonder whether the reports were written by people who weren’t really there?

Aram Yardumian: That’s an interesting point. One of the details I was unable to verify for the book is who was there. I shouldn’t say this if I ever want to visit Iran, but I corresponded briefly with Farah Pahlavi and her secretary and neither she nor he could come up with any names of attendees at the Persepolis premier. There’s a lot of mixing up of the two events. At the 2500th anniversary party, everybody was there. Even Spiro Agnew was there! But nobody really recalls who was present at the Persepolis premier. Journalists must have been there. Surely some traveled there. But maybe the reports were also an excuse to be dramatic in print because you couldn’t otherwise, in the press, say everything you wanted to say, but you could criticize things in this way and get a certain point across without dragging the Shah and Shahbanu directly into it. It was his event, and it was his newspaper.

James Harley: That’s the other thing I was going to ask about. It’s so tricky in that kind of a context to write anything. In Poland during Soviet times, it was also kind of like that. People developed an ability to write around things and be critical without actually being critical. My sense from what you’re reporting is that there was some of that going on in Iran?

Aram Yardumian: I do think there was circuitous criticism of the whole regime. And maybe no one was thinking too carefully about what Xenakis was doing. But you know, there are entire volumes dedicated to just what SAVAK was saying about the Shiraz Festivals. All in Persian. My colleague Houshang Chehabi and I looked carefully, and Stockhausen is mentioned by the secret police but they considered him to be just an idiot, a waste of money, but not threatening in any way. But Xenakis isn’t even mentioned! How do you render Xenakis in Persian? That was one problem. We tried every possible way, and we don’t think he was ever mentioned in those volumes.

Lauren Roser: Can you tell us more about the recording and mixing process?

Aram Yardumian: I wish I could tell you more about that. Studio Acousti in Paris is out of business. I did reach out to someone who had formerly worked there, but not the owner and not anyone who was there in 1971. Everyone who was there in 1971 is gone. I think we’re too late. That studio was quite popular with French folk artists and so on. It was anomalous that Xenakis’s Persepolis came out of that studio. I think he chose it because of its ability to work with sixteen tracks. Not everybody in 1971 had the ability to do that, maybe not even Pierre Schaeffer. And by then the GRM had probably folded anyway. So, I regret that I can’t be more technical about that. At least at the moment.

Carey Lovelace: But didn’t Daniel Teige… he remastered the tapes for the version we did. He must have had some contact. What did he say about that?

Aram Yardumian: We know that Persepolis had to be recorded on eight tracks on two separate reels. An audio reel lasted about half an hour. So Xenakis had to spool the second reel overlapping the first reel overlapping the first one at the premier. You may have noticed that every version of Persepolis runs out at a different timing. One version is a full fourteen minutes different from another! Some of that comes down to versions mastered at the wrong speed, but according to Daniel, who I presume is in the online audience, the version he did allowed for a longer overlap than the recent Karl Records’ version, which I think is also pretty good.8 There is no doubt that more that could be said about how the recording was made but not yet.

References

ANDRÉGUI, Pierre (dir.) (1971), Xenakis, Sodaperaga, 54 min, https://www.medici.tv/en/documentaries/xenakis-persepolis-pierre-andregui

REZVANI, Serge (1971), “L’autre Iran,” Le Monde, 24 November, p. 6.

TAHERI Amir (under the pseudonym Parisa Parisi) (1971), “The Xenakis Attempt to Burn Persepolis,” Kayhan International, 28 August, p. 6.

TEIGE, Daniel (2012), “Dead or Alive. Aspects Concerning the Performance and Interpretation of Xenakis’ Polytopes Today,” in Sharon Kanach (ed.), Xenakis Matters, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon, p. 245–55.

XENAKIS, Iannis (2008), Music and Architecture: architectural projects, texts, and realizations, compilation, translation, and commentary by Sharon Kanach, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon.

YARDUMIAN, Aram (2023), Iannis Xenakis’s Persepolis, London, Bloomsbury.

1 Yardumian, 2023.

2 Program booklet for Persepolis cited in Xenakis, 2008, p. 221–2.

3 Andrégui, 1971.

4 Taheri, 1971.

5 Rezvani, 1971.

6 For more information on this unrealized Arts Center, see Xenakis, 2008, p. 171 and 173–5.

7 See “Iannis Xenakis’ Persepolis L.A.,” Kathryn King Media,

https://www.kathrynkingmedia.com/artist.php?id=2077 and, for some footage of that event, see: Xenakophon, “Xenakis Persepolis Los Angeles” (29 July 2011), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VeXMMdHAiaQ8 “IANNIS XENAKIS > 100th Anniversary Box Sets” (22 June 2021), KarlRecords,

http://www.karlrecords.net/iannis-xenakis-100th-anniversary-box-sets/