7. Continuum versus Disruptum:

A Poetic-philosophical Approach to the Instrumental and Vocal Works of Iannis Xenakis

Pierre Albert Castanet

(translated by Sharon Kanach)1

© 2024 Pierre Albert Castanet (translated by Sharon Kanach), CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0390.09

For my dear friend, Márta Grabócz,

on the occasion of the centenary of Iannis Xenakis.

The more one becomes a musician, the more one becomes a philosopher.

(Friedrich Nietzsche)2

The twentieth century has generated many elements of musical “modernity,” both experimental and speculative. It must be said that, long before their spectacular advent at the end of World War II, Charles Baudelaire (1821–67) had identified that modernity represented “the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, whose other half consists of the eternal and the immutable.”3 At the dawn of this modernist era, which would become increasingly turbulent (until the decrescendo of postmodern obedience—in music—initiated in the early 1980s), a few composers of the twentieth century modified our spatial-temporal vision of the acoustic world, engendering in their parametric wake the unusual meanders of an artistic discourse with prodigious vocabularies and novel syntaxes.4 Among these pioneers, Iannis Xenakis—who was fascinated by nature as well as by light, as much by sound as by numbers, by music as much as by architecture, as much by “outside time space” as by “the temporal flux,”5 as much by undulatory movement as by currents of particles, as much by intellectual gnosis as by operational physics—displayed the beams of a real “poetic vision”6 and a philosophical one, on the sound horizon of a typically sovereign “art-science.”7 In short, as Gaston Bachelard (1884–1962) stated in 1938, “all that philosophy can hope for is to make poetry and science complementary, to unite them like two well-made opposites.”8

While marvelously toying with various physical and metaphysical notions of the world, Xenakis cleverly conceived some unsuspected laws directed towards the so-called “contemporary” sound universe. For sure, at the helm of numerous successful projects (from instrumental solos to spatialized orchestras, and from vocal compositions to his electroacoustic opus, sometimes multidisciplinary…), he has often been recognized as the cantor of unexpected cascades or of violent shock.9 Nevertheless, apart from his significant process characterized by a global approach to sound phenomena,10 we will try to show that, through this somewhat hasty presupposition, he was a great pragmatic initiator of the artistic upheaval in what we could call the “continuist/discontinuist” order (we know how much this relation was valued by the master as “a positive source of conceptual innovation”).11 However, under such circumstances, the concept of continuum has often been evoked in relation to Xenakis’s electroacoustic corpus12 because, objectively, it is quite clear that it is easier to let a sound flow in a continuous way if the support is fundamentally electro-machinic. This is why we have insisted on taking the examples of this present study exclusively from his instrumental and vocal works.

It is also important to add to these introductory remarks that the term continuum appeared regularly in the work of scientists, since the beginning of the 1920s (particularly in the language of physicists), as a set of elements arranged in such a way that one can pass from one to the other in a continuous way. Hence the recovery by relativistic theories13 of the expression of the space-time continuum as a four-dimensional space (the fourth being Time).14 As for the disruptum, etymologically speaking, it concerns the phenomenological data of rupture, break, and fracture15.

A Movement of Flux in the Space-time Artifex

First, it is appropriate to apprehend the peripheral question of the advent of so-called “contemporary” music, an elective register for which Xenakis was a remarkably unequalled representative. For, “what has happened to music since Varèse (1883–1965)?” [qu’arrive-t-il à la musique depuis Varèse?] asked the acousmatic composer François Bayle (b. 1932): “To be interested in the modulation of the breath of energy. To be fascinated by the continuum” [De s’intéresser à la modulation du souffle de l’énergie. D’être fascinée par le continuum]. “What happens to energy?” [Qu’arrive-t-il à l’énergie?] he continues providentially:

To be finely distributed along the veins of time. No longer only the range of shocks, successive blows, local and discontinuous decisions. No more words, no more notes. But what are possible are the flow, a wind, a temperature, a movement that traverses the space, defines it, envelops it, represents it.16

All these parameters—in general primarily fortuitous regarding avant-garde sound art, but now authentically acknowledged—reflect a good part of the elementary ingredients of the Xenakian artifex.17 Moreover, at the heart of this new palette capable of imagining a musical composition under unsuspected auspices, the idea of a continuum relying on an inevitably elusive temporal management has been fundamentally tested, summoned, explained, negotiated, implied, circumvented, impeded on purpose… Henceforth, driven by a scheme (elaborated more than endured) entirely dedicated to the law of continuity of musical time and to its corollary accomplice discontinuity, the sono-artistic opus of this bold and audacious polymath was offered, out of principle, in the pure combinatorial apparatus of a legitimated movement which permeates, articulates, structures, orients and gives it, at the same time, sense and meaning—original or metaphorical.18

Through this order of thought with a strong orthonormal scope, Xenakis followed—mutatis mutandis—in Varèse’s (and sometimes Scelsi’s)19 footsteps by composing for example—among some memorable masterpieces—Naama (1984) for amplified harpsichord.20 But why focus on this work (which is not one of the best known)? Quite simply because its Greek title immediately suggests the notion of “flux.” Moreover, at the time of the Luxembourg premiere, the program note mentioned that the score called for “periodic constructions” [constructions périodiques] realized thanks to a “group of hexahedral transformations as well as stochastic distributions” [un groupe de transformations–exahédriques–ainsi qu’à des distributions stochastiques]. The presentation text of this solo, dedicated to the harpsichordist Elisabeth Chojnacka (1939–2017), also mentioned that (predictable) “fluxes of regularities” [flux de régularités] were opposed to irregularities, to contrary predicates, sometimes distributed on several planes simultaneously, “which requires the soloist’s mastery of the architecture, of techniques specific to the harpsichord, and an exemplary determination” [ce qui exige de la part du soliste, la maîtrise de l’architecture, de la technique spécifique au clavecin et une détermination exemplaire].21 In this solo work, rhythmic passages played on the two keyboards strike percussive patterns (the sporadic addition of incisive stops providing a palette of subtle accents). “It’s as if he were writing for the two hands of a percussionist” [C’est un peu comme s’il écrivait pour les deux mains d’un percussionniste], the virtuoso dedicatee confessed.22

In music, the notion of flux can generate various aspects of the parametric distribution of materials: for example, from the impressionist “subtle fluidity” [subtile fluidité] (cherished by Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–98)) to an infinite melody, the mind has the capacity to inform and control the sound, hence this “flux context” [contexte flux] intervening as soon as the “time factor” [facteur temps] is deployed, provided that a point freely stretches to move in a line of flow.23 In philosophy, the “continuistic” [continuiste] idea can also take on multiple guises: from transcendental meditation to the quest for immortality, via Zarathustra’s doctrine of “eternal return,” [l’éternel retour] understood as “absolute and infinite repetition of all things.” [répétition absolue et infinie de toutes choses].24 For example, for the philosopher Ferdinand Alquier (1906–85) (Gilles Deleuze’s (1925–95) teacher), “the mind cannot engender time. But it can dominate it, reach eternity from which time becomes thinkable.”25 Unceasingly eager to approach the shores of the unapproachable, sown with ineffable feelings, Xenakis courted, within this dual context with the promising prescriptions, the elements of “imaginary dynamology” [dynamologie imaginaire], formerly defined by Bachelard.26

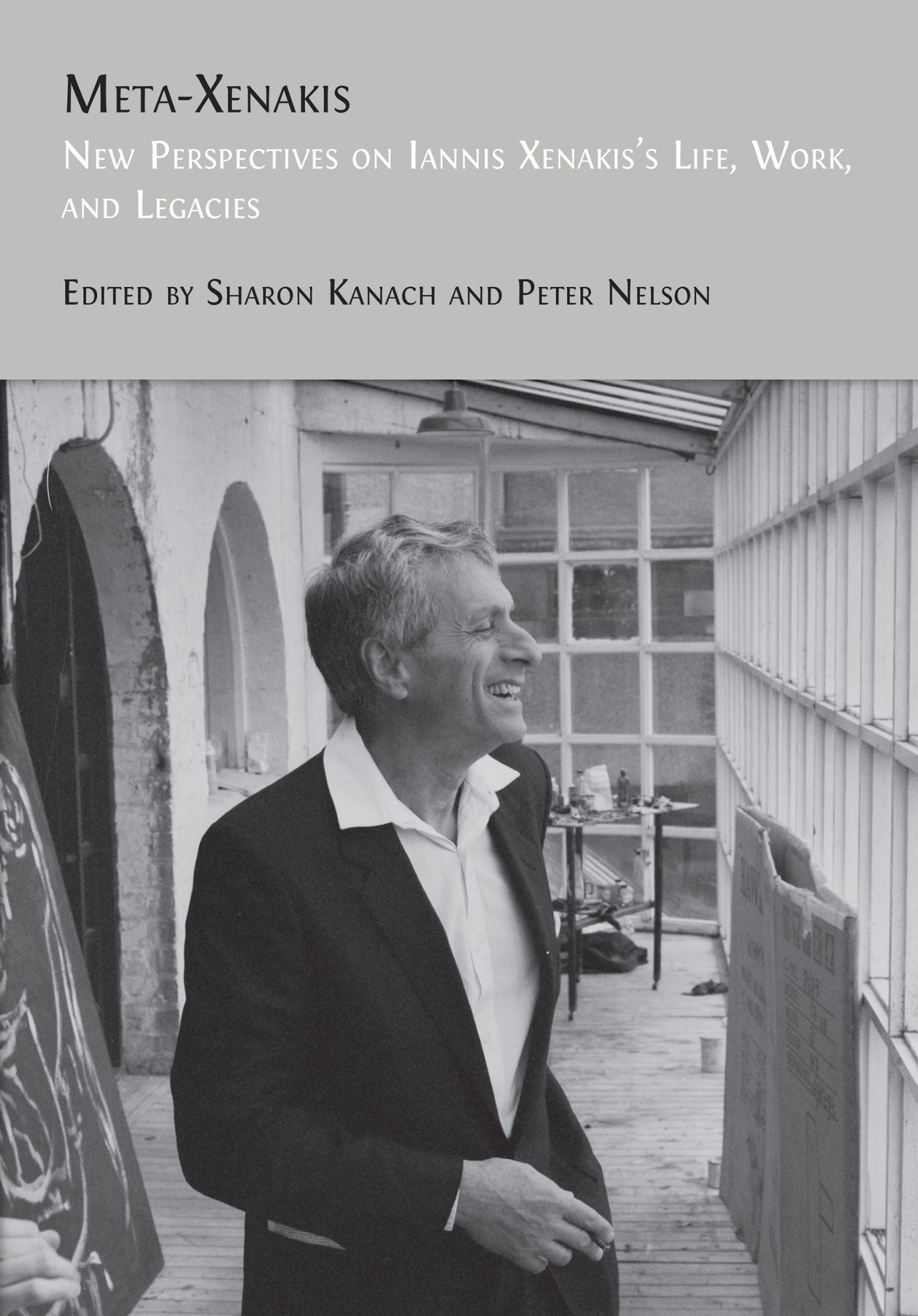

Thus, throughout the phases of creative utopia that marked his career as a composer, Xenakis voluntarily wanted to inhibit the monodirectional flux of the desired sound discourse (a sort of horizon of expectation, agreed upon a priori) in order to always privilege a field paved with “insecurity” [insécurité] and “uncertainty” [incertitude].27 Furthermore, willingly using Valéry’s (1871–1945) relationships embracing abruptness and shock, expectation and surprise28 as principial preferences, artifacts taking the appearance of mysterious barricades were indeed systematically crystallized by the musician, the operation finally engaging the idea of sporadic detour (sometimes of dendritic order).29 Be it through a “happy” Naama or an “unhappy” Roàï (1991),30 the holding tension of a more-or-less disseminated flux is then convincing thanks to the character of the resulting relational duality governing the various directional elements of force that are present. It is important to remember that, for Xenakis, the experimental notion of a “continuous” line was put to work in multiple ways, on the visual level (see, for example, the lines drawn in space by laser beams integrated in the audiovisual spectacles of certain polytopes),31 on the sound level (consider the various lines resulting from graphic gestures feeding the functions of acoustic representation offered by the UPIC).32

Fig. 7.1 Iannis Xenakis demonstrating the first version of his UPIC. Archives du Centre Iannis Xenakis / CIX—Université de Rouen Normandie, Després collection.

An Alternative Order of Temporal Metaphysics in the Context of the Xenakian Habitus

“To name is to isolate within a continuum,”33 Antoine Compagnon (b. 1950) indicated as an aside. Certainly, the ability to define the local while thinking of the global perspective seduced a good number of composers with a theoretical spirit34 during the twentieth century. In fact, only the elements of sensation and cognition seem to be able to acknowledge the discrete pertinences of the “continuous/discontinuous” [continu/discontinu], or even “periodic/aperiodic” [périodique/apériodique]35 systemic binomial, even if the semioticians judged the qualities of this domino as belonging to a pertinently and reasonably “undefinable” [indéfinissable]36 element. Conversely, it is undoubtedly the idea of immanence and permanency of state (real or slightly warped) in the space-time framework that can legitimize the notion of continuity (in fact, sometimes thanks to the aspectual relief reminiscent of the shape of a volubilis, a spiral, a typhoon or nebula). For, a bit like the matrix icon represented by the continuum, cannot the helical form of the spiral constitute a “universal glyph” [glyphe universel]37 in the “habitus”38 of the musical temporality?

Is it necessary to mention that as an ornamental figure, the idea of the spiral has illuminated many compositional projects in music after 1945,39 its “evolving” and “involuting”40 principles being subject to the experiential rite of establishing reference points managed by the laws of space-time?41 While the generic symbolic representation of the labyrinth has frequently served to confront the solitary walker with blind spots and dead ends with opaque sides (generating in fact a discontinuous multicursal place)42, the cliché of the spiral has, on the other hand, systematically referred to the application of a smooth, regular, continuous, ordered and above all unicursal becoming.43 Between tangible mechanism and abstract conceptualism, for example, Xenakis tried his hand at the spiral vortex in the last section of Persephassa (1969), a piece for percussion sextet surrounding the public (premiered in Iran during the Festival of Shiraz).44 Consequently, this kind of relief, skillfully designed for spatialized listening, sought to keep the spectator informed on the spot of this ex- or con-centric circumvolutionist model (a paragon continuously implying a modulated non-blunt curve). Besides, we will note in the margin that the musician had committed himself to denote poetically45 the strangeness of the place occupied by the spiral as an “aesthetic ornament” [ornement esthétique] in its geographical distribution (on earth, in some epochs of high Antiquity, during millennia before our era...).46

Moreover, convinced that the “intellectual representation” [représentation intellectuelle] of continuity was rather “negative” [négative], didn’t Henri Bergson (1859–1941) find that, like immobility, intelligence was “clearly [represented] only by the discontinuous” [clairement [représenté] que par le discontinu]?47 Disserting on free will and the isolation of the elements, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) showed that “in reality, the whole of our activity and our knowledge” [en réalité l’ensemble de notre activité et de notre connaissance] was not ”a series of facts and empty intermediate spaces” [une série de faits et d’espaces intermédiaires vides] but “a continuous flux” [un flux continu].48 As for Xenakis, he indicated in his way—anthropologically speaking and by leaning on the data of a Zenonian problematic—that man represented the symbol of the discontinuous: “it is a kind of perpetual struggle of our perception and our judgment to try to imagine the continuous movement” [c’est une sorte de lutte perpétuelle de notre perception et de notre jugement que d’essayer d’imaginer le mouvement continu], he had confided to us, on 7 May 1986, at the time of a conference at the Université de Rouen.49 Let us also remember that Gilbert Amy foresaw with a certain good sense that “neither you, nor the best ‘listener’ can boast of not having a fraction of a second of distraction, and thus of introducing discontinuity in an apparently smooth listening.”50 In some respects, this idea is reflected in Xenakis’s musical design as, already in the mid-1950s, the artist imagined, a new “morphology” of an acoustic order. The musician was then working on a composition for two trombones, forty-six string instruments, xylophone and woodblock which was entitled Pithoprakta (1955–6) (in fine, this score51 implemented—“stochastically” speaking—action of probabilities).52

Exhibiting a wide range of sounds going from noise to pure harmonics and playing categorically on the “plastic modulation of matter” [la modulation plastique de la matière],53 Pithoprakta became thereafter an emblematic work of “contemporary music” with its singular contours. This ten-minute work sought an audible confrontation of continuity and discontinuity through, on the one hand, the calculated use of glissandi (assimilated to straight lines in continuous transformation)54 and, on the other hand, the use of pointillist pizzicati (groupings of sorts of acoustic pixels in view of the relevant granulation of the different sound volumes). However, generating a “sensation of unheard-of materials” [un sensation de matières inouïes]55 (especially by the turgid presence of more or less dense sound blocks), the palette of effects was enhanced by very brief bow strokes, strikes with the wood of the bow, and knocks by the hand on the body of the stringed instruments (divisi to the extreme).

Basically, on the strict conjectural level of this “continuum of discrete sensations” [continuum des sensations discrètes],56 can’t the principle of the localized or generalized glissando (despised by Boulez)57 be related to the driving element of a “theory of the continuous field” [une théorie du champ continu]? Because for the architect-musician answering Michel Serres (1930–2019), “the glissando is precisely a modification of something in time, but imperceptible, meaning that it is continuous but cannot be grasped, because man is a discontinuous being.”58 (It should be noted that this idea joins the Bachelardian conception of musical experience.)59 In fact, influenced by Euclidean geometry, the glissando effect can be treated as a signaling index of transition (or intermediate link between two distinct or similar materials): one might listen to the beginning of Jalons (1986) for fifteen musicians. Here, the glissando makes it possible to pass from abrupt textures (accentuated by blocks or points) to zones of microtonal oscillations. Similarly, between continuous and discontinuous, doesn’t this same sliding artifice, placed within Tetras (1983) for string quartet, serve to maintain a link,60 joining one pole to the other?61 In this respect, two other questions arise simultaneously: doesn’t this sectorial positioning have the mission of including a principle of elementary topics for which geometry would ostensibly tend to be reflected even in its very constitution? And then, between a feeling of relativity and a project of continuity,62 would not this binary (and complementary) mesh correspond to the prominent elements of Taoist thought concerning the unity of opposites (Yin and Yang)?63

Elsewhere, in Nuits (1967–8) for twelve mixed voices, modulated glissandi offer the precise qualities of an indexed element cementing in three superimposed strata the extended significance of the melodic relief of the score, thanks to the technique of crossfading64 and sometimes to that of evolution by overlapping; one might listen, for example, to the triple forte opening ostensibly colored by the timbres in the women’s voices. Furthermore, the vocal and extra-vocal material65 of the beginning of this a cappella work (premiered in 1968 at the Royan Festival), demonstrate a striking aural poetry, between purity and impurity, stemming from a symbolism aiming at the extension of the line66 through a rhythmic-melodic design curved by a network of wavy slurs (cf. the “très lié” [closely tied] mentioned at the beginning of the score).67 Chosen to easily accentuate the linear (or smooth) character of their respective relationships, the characteristic elements of the expressive palette68 are

- Continuous glissandi: implies the singer will cover all the micro-intervals between the two written notes. This unified path in the continuum thereby offers an ascending or descending vocal siren effect.69 This technique is present from the first pages of the score, but it also animates the rising and falling curves of the sixth, seventh, and eleventh parts. For the record, omnipresent in the great musical work of the polytechnician, the glissando was theoretically considered by Xenakis as “a particular case of continuously varying sound.”70

- Brief glissandi: unlike the continuous glissando, this short effect resembles a very rapid “spurt of sound” [jet sonore]71 (a furtive, percussive impact) as compared to a siren’s stretched sound (a vocalized type of sound line). Its spasmodic function nevertheless allows for a jump of an octave (ascending or descending). This same process, entrusted to the strings, is used in the first measures of Tracées (1987) for large orchestra.72 Moreover, Xenakis had noticed that “a crowd of short string glissandi can give the impression of continuity and a crowd of pizzicati can also do so” [une foule de glissandi courts de cordes peut donner l’impression du continu et une foule de pizzicati le peut également].73

- Whistling sounds: it depends on a play of air (of the “colored noise” [bruit coloré] type) obtained from the tip of the lips (with the addition of a lot of air). Diversely timbred, this singular sound in fact results from an indeterminate pitch. Like the sound rendering of a siren (similar to a vocalization or a Larsen effect, or even the malleable sound of an electric guitar, a theremin, or ondes Martenot), this kind of acoustic arabesque shows a truly exemplary degree of continual fluidity (see especially the fifth and sixth parts of Nuits).

From “Continuous” Smoothness to “Epic” Disruption

For Aristotle (384–22 BCE), “we perceive movement and time simultaneously” [c’est simultanément que nous percevons le mouvement et le temps].74 Nevertheless, treated in a scientific or metaphorical manner, spatial movement and temporal animation can sometimes take on the appearance—a priori paradoxical—of balance within imbalance or order within disorder (for example, the final homogeneity in Jonchaies (1977) for orchestra is constantly confronted with the “disorder of a field of rushes” [désordre d’un champ de joncs]).75 See the image reproduced in the catalog published by The Drawing Center of a sketch for the composition of Jonchaies:76 at the top of this multicolored study, Xenakis shows an unequivocal desire to “interrupt” the flow initially drawn in six colored layers.77

Regarding this kind of process, which is conducive to the play of regulation/deregulation, Paul Ricœur (1913–2005) discussed the theme of the “rupture of an order for the benefit of a terminal situation, conceived as a restoration of order.”78 In any case, Robert Francès (1919–2012) judged for his part that it was necessary to consider the relationships existing between “the main idea and its different appearances” [l’idée principale et ses différentes apparitions], and that it was useful to respect the relations manifesting themselves between “this idea and those that are interspersed between the different appearances” [cette idée et celles qui s’intercalent entre les différentes apparitions]. In his doctoral dissertation, this professor of psychology even mentioned a third manner, a synthetic one at that, aiming at the associations established between all “the intercalary ideas” [les idées intercalaires].79 It is precisely within the framework of a global auditory apprehension that we could interpret these organizational signs associating—in a simple or complex way—the horizontal, oblique, and vertical values of Xenakis’s musical writing. From this contingent of more or less instinctive or totally thought-out practices, we can then perhaps promulgate that, in any mathematical law, the parametric character (that we allow ourselves to apply here to the heuristic domain of music)80 possesses a priori the property to alter the centrifugal deployment of the “space-time” couple. As Gaston Bachelard liked to insist: “no space without music because there is no expansion without space.”81 Thus, it is undoubtedly interesting to think that, on both sides of the dividing line, taken in isolation, each moving parameter has the possibility of concealing the paradoxical osmosis of the “constant-flow” [constant-coulant],82 (as Paul Valéry incidentally perceived it). In this sense, the score of Xenakis’s Mikka (1971) for solo violin uses, as an indicated arrow towards the idea of continuum, quarter-tones—so many sample frequencies considered almost-touched landmarks, delimiting the layout of the elaborate audio-plastic curves to be realized with an extreme dexterity.

About Mikka, this peculiar solo where the glissando is king,83 the instrumentalist can read that

the continuous line below or above the notes means a continuous variation in pitch that passes through the notes inscribed, considered reference points, on which one must not stop, because the glissando must continue throughout the duration of the note. Therefore, it is useless to try to play according to a traditional fingering, because it is (one or) several fingers that must continuously slide on the strings without stopping, except where the continuous line does not appear, as well as where there is no indication of a glissando.84

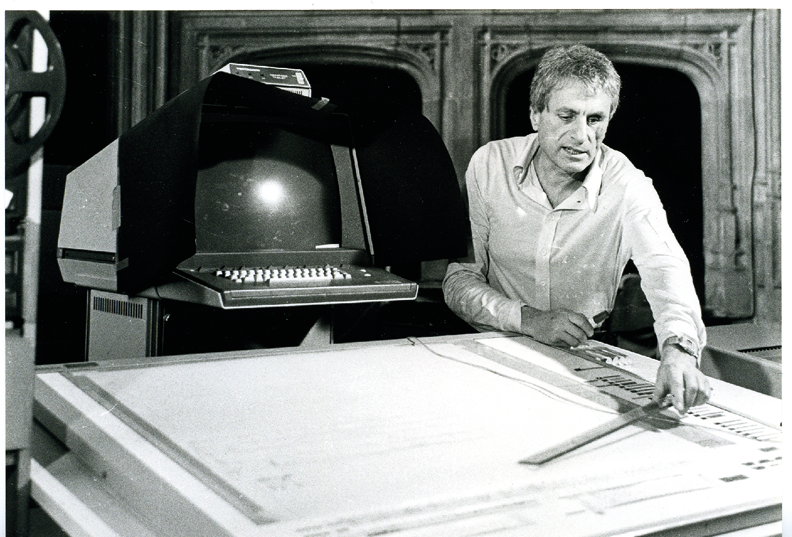

Listen, in this respect to this monodic excerpt modeling a relief (of a melodic order),85 sometimes elusive (in tied sixteenth-notes), sometimes static (pole notes in long values: in this case, tied whole-notes). Here, it seems, “it is the interior of time that counts, not its absolute duration; the content where time is articulated independently and simultaneously by various musical events.”86

Fig. 7.2 Mikka (1971) by Iannis Xenakis for solo violin, p. 1.87

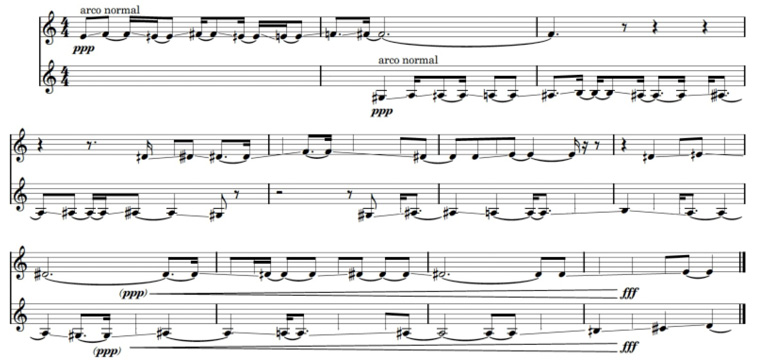

Similarly, in the score of Mikka S—a companion work completed by Xenakis in November 1975, published in 1976 by Salabert (the title of which is sometimes written Mikka “s”)—the mostly two-staved notation (except for the monodic coda, played ffff), sometimes introduces eighth-tone oscillations. A general performance note—not a simple one, at that—informs the solo violinist that

the glissandi are to be played in such a way that, to the ear, the pitch change will be absolutely uniform (a progressively slower ascending movement, a progressively faster descending one) and must be executed and completed precisely according to their indicated durations.88

Dedicated to his publisher, Mica Salabert, this piece—which can complement the performance of Mikka in an interesting, albeit dizzying diptych—demonstrates, from its start, the idea of a laminated continuum, in relay with overlapping of voices (on two strings, bars 2 and 3), leading to a bifid ribbon (end of bar 5) sharing dynamics (synchronized crescendo from ppp to fff, bars 8–11).

Fig. 7.3 The first 11 bars of Mikka S (1976) by Iannis Xenakis for solo violin, p. 1.

In these two violin examples, Xenakis—who in this circumstance willingly compared sounds to molecules89—installed a degree of flexibility in the sliding continuum thanks to the transfer of the prolific nature of Brownian movement.90 Thus, whether it is about a monist sphere or a pluralist universe, the conclusion is always the same, according to Bachelard: “a homogeneous process is never evolutionary. Only a plurality can withstand, can evolve, can become. And the becoming of a plurality is polymorphic as the becoming of a melody is, despite all simplifications, polyphonic.”91

Therefore, to make the phenomenon relevant, scholarly musicians often have recourse to the “epic” technique (to borrow an expression from Roland Barthes (1915–80)92 of breaking the established order93 (on the global level) and of the rupture of the legendary linearity of the continuum (on a more local level). Thus, artfully installed, this principle tends to establish breakable points or segments of derailment that divert listening, for a while. In this respect, in the context of a generalized overview, let us consider the role of micro-intervallic details integrated into the polyphonic treatment enveloping—between coherence and incoherence94—the sometimes archaic, sometimes avant-garde arrangement of the piece entitled Embellie (1981) for solo viola—this work being the composer’s last solo work.95 About this point, one might listen also to Keren (1986) for trombone. In this unusual solo, Xenakis placed glissandi and micro-intervals at the service of a melodic ribbon sporadically interrupted by disruptive elements (irregular rhythms and accents, varied timbres, register leaps, sudden contrasting dynamics…).96 In this framework, where appreciation of the local perception of temporary misalignment is diligently sought, we could certainly try to delve into the fundamental technique that governs the “breaking points” [points de rupture] of the continuity of the “serial” [sérielle] writing of Metastasis (1953–5).97 However, an attentive listener can more easily notice the arrival of the agitating strokes (with acerbic pointillism) performed by the wood-blocks in this work for orchestra (sixty-one performers). It is also possible to fully grasp impacts of the same kind occurring in Rebonds B (1987–9),98 a piece conceived for solo percussion. Similarly, one may try to locate the rhythmic sections (not embedded) attributed to the passages with a punctuated character in Nuits for vocal ensemble (see on this point the treatment of the vocal material in a “striated” [striée] temporal form).99

Between constraint and freedom, arduous calculations and mere feelings, formalization and abstraction, the alternation of modes of fluidity (smooth/choppy) are then attached to an original way of orienting the discourse from the one to the multiple (and vice versa). It is then possible to suspect that the composer’s intention resides in a subtle play of contrasts bearing witness to the strategic idea of change, detachment, diversion, derivation, divergence... interruption, cut, break, caesura, rupture... and more poetically of “embellie” [embellishment], upstream and downstream from an imaginary “storm” [tempête]100… Incidentally, does not this form of hiatus resemble in some respects what Boulez called “incise”101—in this case, in the introduction to Incises for piano102—a work that Boulez began in 1994—the composer symbolically placed a “supple” [souple] element between two “very fast” [très rapides] passages? In Xenakis’s output, an illustration of such a process oriented towards a clear derivation is found in Knephas (1990).103 Linking held notes (or melodic material based on a vocalization) to phases nourished by brief rhythms sung homo-rhythmically, this dark work for mixed a cappella choir was written by Xenakis after the death of his friend Maurice Fleuret (1932–90). In the same manner, if we return to Tetras, we notice that the avant-garde musician insisted on judiciously placing some efficient noise effects (of non-smooth, pizzicati of various sorts) in transitional zones where continuous glissandi sections predominate (these eruptive intermediate data go, for example, from a simple vibrato wave to the fluctuation of complex trills).104

For the record, on the first page of the score symbolically entitled Metastasis, dedicated to Maurice Leroux (1923–92), is it not expressly requested that the players of the bowed strings interpret “glissandi of a rigorously continuous movement” [glissandi d’un mouvement rigoureusement continu] (these controlled curves with a sliding trajectory directly based on the graphics105 of the work of the architect Xenakis)?106 The project of this carefully thought-out score was in fact intended to favor the full qualitative development of the spatial-temporal reference point: “the harmonics, the glissandi, the pizzicati hammer out the serial rounds by creating perspectives and multidimensional sound volumes,”107 the composer was keen to explain. Moreover, in the program note accompanying the premiere of the work at the Donaueschingen Festival,108 didn’t the composer note that “the ‘linear category’ of contemporary musical thought had been overtaken and replaced by surfaces and masses”? [la “catégorie linéaire” de la pensée musicale contemporaine se trouve débordée et remplacée par des surfaces, des masses ?]109 Let us also note that the title Metastasis comes from the ancient Greek μετάστασις (μεθίστημι meaning “I’m changing places” [je change de place]. In addition, this word is also the etymological origin of “metastasis,” a medical notion that implies the idea of moving the locus of a disease, but above all, implies the corollary concept of its continuous evolution.

In the same vein, Thallein (1984) for instrumental ensemble refers to the slow metamorphosis of plants110 (with their almost invisible transitions at a given time).111 Indeed, the Greek title chosen by Xenakis refers to the natural idea of budding, suggesting notions of discrete growth, of the quiet blossoming of a given organic life.112 This dreamlike (extra-musical) context of inspiration subsequently triggered a desire to put natural phenomena into his scores. Thus, musically speaking, the family of glissandi seems to offer here free-floatings, describing sensitive zones to the ear of wayward activities with blurred and impalpable reliefs. Let us distinguish once more that in the historical masterpiece that is Metastasis (as well as in Mikka and Mikka S, in some passages of Embellie, and in many other works for strings), vibrato is totally proscribed.113 Given the technique of elusive transformation of pitches, the syntactic context of this singular corpus does not operate at all through the tempered scale of the twelve tones of the classical chromatic scale, but opens up a whole galaxy of sounds with circumstantial micro-intervallity.

When Xenakian Philosophy Embraces an (Inaccessible) Idea of the Continuum

Concerning the relation to Homeric reverence, didn’t Barthes prosaically affirm that “the epic is what cuts (shears) the veil, breaks down the tar of mystification”?114 Therefore, the behavior of musical discursivity (inevitably evolutionary, due to associating the virtues of the continuum and of the discontinuum) depends, for Xenakis, more on the immanent complementarity of the presence of dynamic materials than of the properly elementary negation of an intentionally and mono-directionally limited path. Among the many zealous metaphors attached to varied contexts of energies,115, “euphoric” [euphoriques] as well as “dysphoric” [dysphoriques], Milan Kundera (1929–2023) underlined that the starting point of Xenakis’s music is situated “in the noise of the world, in a ‘sound mass’ which does not spring from the inside of the heart, but arrives at us from the outside like rainfall, the din of a factory, or the shout of a crowd.”116 In the same manner, when praising the nonconformism of creation, the philosopher Stéphane Lupasco (1900–88) once demonstrated that “the logic of the aesthetic must evolve, and be centered inversely of a rational or irrational process; in other words, inversely of a process of non-contradiction. The logic of aesthetics must proceed from the non-contradictory to the contradictory; its goal is contradiction.”117

In the end, both as a virtuous indication favorable to the most diverse interferences (positive and negative) and as a convincing guarantee of general dynamics (both local and global), the Xenakian dichotomous approach seems to show—even if we listen blindly to his works—a polyagogical sense.118 Indeed, we could argue that, with this composer, the completion of a work depends, most of the time, on the purely aesthetic ingredient that is this influxus imperfectus. Should we then remember that this absolute system incriminating a certain idea of contrast can “topically” [topiquement] show, on various levels119, “two fundamental aspects of sound” [deux aspects fondamentaux du son]? On this subject, the composer of Eonta (1963–4)120 continues:

The discontinuous is easier to understand, because everyday life teaches us to distinguish phenomena like day and night, seasons, and years, etc. Continuous evolution is much more difficult to grasp because it refers to the very transformation of a phenomenon, to its intensity and speed. It is very difficult to be conscious of it because any change is supposed to be infinitesimal.121

Attempting to gather some synthetic data to approach the concluding elements of this study, we could contextualize, on the one hand, the words of the Belgian philosopher Pascal Chabot (b. 1973) who reminds us that “humanity now lives at the rhythm of disruption.”122 More simply, on a psychological level, between “substantive parts” [parties substatives] and “transitive parts” [parties transitives], the American psychologist and philosopher William James (1942–10) shows, on the other hand, that various “currents of consciousness” could be linked to some informational flows “like the life of a bird, [its flux] seems to be made up of alternating flights and perches [...],”123 as the erudite philosopher remarks with a touch of pedagogical imagery. As the idea of unraveling some braided links of intuitive conviction124 and intimate necessity125 comes to mind, we might dare to establish a (admittedly adventurous) connection between an introspective listening to the self and the extrinsic dynamics of animated sound, terms finally understood as coming from the classical domain of “kinesthesia” [kinesthésie] (or “sense of movement” [sens du mouvement].126 If Plato (428/27–348/47 BCE) was fundamentally interested in seeking an exclusive judgment of the deep knowledge of every person,127 wasn’t Xenakis’s epistemological project a deepened philosophy of the external consciousness of the governance…of sounds? We find ourselves at the crossroads of “enstasis” [enstase] (noted by Satprem (1923–2007)128 as the fruit of the supreme experience found in the depths of our being) and of “ek-stasis” (cited by Xenakis129 as a way out from oneself—for creative purposes). In this context, the artist-philosopher Richard Shusterman (b. 1949) shows, more recently, that certain “conditions” or even certain “stimuli” [stimulations] could provide an individual with both the “formative energies and the guidelines for expressive movement, as well as for self-knowledge and self-cultivation.”130

Now to conclude, we invite researchers to venture further into these musicological regions not yet truly explored, as we are aware that there are still many points to be raised and clarified in the field of human sciences regarding Xenakian music philosophy. The epistemologist Gilles Gaston Granger (1920–2016) believed in a philosophy whereby one of the active links would preside over the field of hermeneutics, naturally keeping “its place at the edge of science, whatever progress it makes, but it could only substitute itself by imposture, just as an equal imposture would suppress philosophy for the benefit of science.”131 Furthermore, didn’t Nietzsche consider the “philosopher” as being ‘a terrible explosive that puts everything in danger”?132 In this context, let us remember that in June 1966, Xenakis published, in the twenty-ninth and last issue of the Gravesaner Blätter (Gravesano Review),133 an extensive article precisely entitled “Towards a Philosophy of Music.”134 In addition, as a fighter against conventions, as much as a pioneer of the unheard of, didn’t the artist-engineer want to create music “without following known paths or being trapped by them”?135 This is how he reminded us on so many occasions that he wanted to “open the windows to the unprecedented.”136 As Francis Ponge (1899–1988) emphasized, “things have to disturb you. They must force you to get out of the rut; that is the only interesting thing because that is the only thing that can make the mind progress.”137

In fine, within these preoccupations of intellectual obedience, it would be possible to once again quote a remark by Satprem because, in a synthetic way, this “researcher of worlds to come” [chercheur des mondes à venir] admitted without blushing that “not everyone is a philosopher, nor poet, and even less a fortune teller.”138 Nevertheless, because of this utopian idea of continuum in filigree throughout his numerous music compositions and aesthetic reflections, wasn’t the follower of set theory someone who finally practiced “philosophy, as an inaccessible thought of totality”?139 Moreover, didn’t the composer François-Bernard Mâche (b. 1935)—a long-time friend of Xenakis—point out that “a true musician is always a philosopher of sounds, and his aesthetic conceptions always carry their glances beyond simple considerations of craft and emotion”?140 Faced with such questions remaining to be solved (in the long run), one of the answers perhaps resides in what Xenakis initiated in 1965 when he declared with solemnity that “the era of Scientific and Philosophical Arts has begun. From now on, a musician will have to be a maker of philosophical theses and global architectures, of combinations of structures (forms) and sound matter.”141

References

ALQUIÉ, Ferdinand (1987), Le Désir d’éternité, Paris, Presses universitaires de France.

ARISTOTLE ([400 BCE] 2015), Physique, Paris, Flammarion.

BACHELARD, Gaston (1943), L’Air et les songes, Paris, José Corti.

BACHELARD, Gaston (1948), La Terre et les rêveries du repos, Paris, José Corti.

BACHELARD, Gaston ([1936] 1989), La Dialectique de la durée, Paris, Quadrige/Presses universitaires de France.

BACHELARD, Gaston (2017), La Psychanalyse du feu, Paris, Gallimard.

BAILLET, Jérôme (2003), “Des transformations continues aux processus de transformation,” in Makis Solomos (ed.), Iannis Xenakis, Gérard Grisey—La métaphore lumineuse, Paris, L’Harmattan, p. 237–44.

BARNETT, Lincoln (1951), Einstein et l’univers, Paris, Gallimard.

BARTHEL-CALVET, Anne-Sylvie (2003), “MÉTASTASSIS-Analyse: Un texte inédit de Iannis Xenakis sur Metastasis,” Revue de Musicologie, vol. 89, no. 1, p. 129–87.

BARTHEL-CALVET, Anne-Sylvie (2011a), “Xenakis et le sérialisme: l’apport d’une analyse génétique de Metastasis,” Interactions, vol. 31, no. 2, p. 23–34.

BARTHEL-CALVET, Anne-Sylvie (ed.) (2011b), Oser Xenakis, Paris, Durand-Salabert-Eschig.

BARTHES, Roland (1995), Œuvres complètes, vol. III, Paris, Seuil.

BAUDELAIRE, Charles (1980), Œuvres complètes, Paris, Robert Laffont.

BAYLE, François (1993), Musique acousmatique - Propositions... positions, Paris, INA-GRM/Buchet-Chastel.

BERGSON, Henri ([1911] 1994), L’Évolution créatrice, Paris, Quadrige/Presses universitaires de France.

BERTHOZ, Alain (2013), Le Sens du mouvement, Paris, Odile Jacob.

BOULEZ, Pierre (1964), Penser la musique aujourd’hui, Geneva, Gontier.

BOULEZ, Pierre (1989), Jalons (pour une décennie), Paris, Christian Bourgois.

BUJIC, Bojan (1997), “Delicate Metaphors: Music, Conceptual Thought and the ‘New Musicology’,” The Musical Times, vol. 138, no. 1852, p. 16–22.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (1986), “MISTS de Xenakis: de l’écoute à l’analyse, les chemins convergents d’une rencontre,” Analyse Musicale, no. 5, p. 20–31.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (1998), “L’espace spiralé dans la musique contemporaine,” in Makis Solomos and Jean-Marc Chouvel (eds.), L’Espace: Musique/Philosophie, Paris, L’Harmattan, p. 85–103.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2000), “Tourbillon et spirale: matrices universelles dans la musique contemporaine,” in Béatrice Chevassus-Ramaut (ed.), Figures du grapheïn, Saint-Étienne, Université Jean Monnet/CIEREC, p. 35–42.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2003), “SPIRALES – de la spirale esthétique à la cyberspirale médiologique: Technique et Politique dans la ‘musique contemporaine,’” Universidade de Aveiro (Portugal), Comunicarte, vol. 1, no. 4, p. 38–47.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2009), “Analyse d’Incises de Pierre Boulez,” Guide d’écoute, Paris, Cité de la musique.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2014), “Les humanités sensibles d’un sphinx à l’oreille d’airain: notes pour une philosophie xenakienne de l’art, de la science et de la culture,” in Pierre Albert Castanet and Sharon Kanach (eds.), Xenakis et les arts: miscellanies, Rouen, Ed. Point de vues, p. 14–35.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2018), “Flux de forces et forces de flux dans la musique de Tristan Murail,” Euterpe, no. 30, p. 14–19.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2021a), “Musica Motus Modus - De l’entéléchie à la kinesthésie: pour de nouveaux ‘gestes-mouvements,’” in Pierre Albert Castanet and Lenka Stransky (eds.), MOUVEMENT - Cinétisme et modèles dynamiques dans la musique et les arts visuels, coll. aCROSS, Sampzon, Delatour France, p. 69–86.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2021b), “‘Mouvement est nécessité’: pour une relation au monde du mouvement et de la musique,” Itamar, vol. 7, p. 72–94, https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/ITAMAR/article/view/23593

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2023), Giacinto Scelsi—Les horizons immémoriaux—La philosophie, la poésie et la musique d’un “sage” au XXe siècle, preface by Tristan Murail, Paris, Michel de Maule.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (2024), Hommage aux compositeurs Tessier, Murail, Levinas, Grisey, Dufourt—1973–2023—50 ans de L’Itinéraire, preface by Alain Louvier, Collection aCROSS, Sampzon, Delatour France, p. 141–67.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert (forthcoming), “Continuum versus Disruptum: Pour une approche poético-philosophique de l’idée de continuum dans l’œuvre instrumentale et vocale de Iannis Xenakis,” in Laurence Le Diagon and Geneviève Mathon (eds.), De Franz Liszt à la musique contemporaine: musicologie et significations – Hommage à Martá Grabócz, Dijon, Éditions universitaires de Dijon.

CASTANET, Pierre Albert and KANACH, Sharon (eds.) (2014), Xenakis et les arts: miscellanies, Les Cahiers de l’École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Normandie Recherche, Rouen, Point de vues.

CAULLIER, Joëlle (1988), “Pour une interprétation de Nuits,” Entretemps, no. 6, p. 59–68.

CAZABAN, Costin (2000), Temps musical / espace musical comme fonctions logiques, Paris, L’Harmattan.

CHABOT, Pascal (2018), interview, Télérama, no. 3558, 21 March 2018.

CHOJNACKA, Élisabeth (2008), Le Clavecin autrement—Découverte et passion, Paris, Michel de Maule.

COMPAGNON, Antoine (1998), Le Démon de la théorie—Littérature et sens commun, Paris, Seuil.

DELALANDE, François (1997), “Il faut être constamment un immigré”: Entretien avec Xenakis, Paris, Buchet/Chastel.

DELEUZE, Gilles and GUATTARI, Félix (1972), Anti-Œdipe, Paris, Minuit.

DELEUZE, Gilles and GUATTARI, Félix (1980), Mille plateaux, Paris, Minuit.

DELEUZE, Gilles (2015), Lettres et autres écrits, Paris, Minuit.

DELIÈGE, Célestin (2003), Cinquante ans de modernité musicale: de Darmstadt à l’IRCAM, Brussels, Mardaga.

DEMANGE, Dominique (1991), “Iannis Xenakis, une approche philosophique,” Le Philosophoire, no. 7, p. 200–40.

DIDEROT, Denis (1994), Œuvres esthétiques, Paris, Classiques Garnier.

DURAND, Gilbert (1982), Les Structures anthropologiques de l’imaginaire—Introduction à une archétypologie générale, Paris, Bordas.

DUSAPIN, Pascal (2001), “Hommage,” in François-Bernard Mâche (ed.), Portrait(s) de Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, p. 90.

ECO, Umberto (1965), L’Œuvre ouverte, Paris, Seuil.

EINSTEIN, Albert ([1910] 2001), La Relativité, Paris, Petite Bibliothèque Payot.

FOUCAULT, Michel (1971), L’Ordre du discours, Paris, Gallimard.

FRANCÈS, Robert (2002), La Perception de la musique, Paris, Librairie philosophique J. Vrin.

GALLIARI, Alain (2007), Anton von Webern, Paris, Fayard.

GRABÓCZ, Márta (1998), “Formules récurrentes de la narrativité dans les genres extra-musicaux et en musique,” in Costin Miereanu and Xavier Hascher (eds.), Les Universaux en musique, Paris, Sorbonne, p. 68–86.

GRABÓCZ, Márta (1999), “Méthodes d’analyse concernant la forme sonate,” in Méthodes nouvelles, musiques nouvelles, Strasbourg, Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg, p. 109–35.

GRANGER, Gilles Gaston (1967), Pensée formelle et Sciences de l’homme, Paris, Aubier-Montaigne.

GREIMAS, Algirdas Julien and COURTÈS, Jacques (1979), Sémiotique - Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Paris, Hachette.

HASEGAWA, Robert (2012), “Coherence and Incoherence in Xenakis’s Embellie,” in Sharon Kanach (ed.), Xenakis Matters, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon Press, p. 29–41.

JAMES, William (1909), Précis de Psychologie, vol. IX, Paris, Marcel Rivière.

KANACH, Sharon and LOVELACE, Carey (eds.) (2010), Iannis Xenakis: Composer, Architect, Visionary, Drawing Papers 88, New York, New York, The Drawing Center, https://issuu.com/drawingcenter/docs/drawingpapers88_xenakis

KOESTLER, Arthur (1964), The Act of Creation, London, Hutchinson.

KUNDERA, Milan (2009), Une rencontre, Paris, Gallimard.

LALO, Charles (1939), Éléments d’esthétique musicale scientifique, Paris, Vrin.

LASSUS, Marie-Pierre (2010), Gaston Bachelard musicien—Une philosophie des silences et des timbres, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

LIGETI, György (1974), “D’Atmosphères à Lontano - un entretien entre György Ligeti et Josef Häusler,” Musique en jeu, no. 15, p. 21–32.

LUPASCO, Stéphane (1947), Logique et contradiction, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France.

LYON, Raymond (1974), “Propos impromptus,” Courrier musical de France, no. 48, p. 25–6.

MANDOLINI, Ricardo (2012), Heuristique musicale—Contributions pour une nouvelle discipline musicologique, Sampzon, Delatour France.

MÂCHE, François-Bernard (2001), Musique au singulier, Paris, Odile Jacob.

MATOSSIAN, Nouritza (1981), Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Fayard/Sacem.

MATOSSIAN, Nouritza (2005), Xenakis, Cyprus, Moufflon Publications.

MICHEL, Pierre (2002), Amy... un espace déployé, Pertuis, Millénaire III.

MIEREANU, Costin (1998), “Statégies du discontinu - Vers une forme musicale accidentée,” in Costin Miereanu and Xavier Hascher (eds.), Les Universaux en musique, Paris, Sorbonne, p. 31–42.

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich ([1908] 1993), “Ecce Homo,” in Œuvres, Paris, Robert Laffont.

NIETZSCHE, Friedrich ([1888] 2007), Le Cas Wagner, Paris, Allia.

PEZET, Jacques (2017), “Check News: Que signifie «disruptif» et pourquoi tout le monde sort ce mot?” (13 October), Libération, 13 October, https://www.liberation.fr/desintox/2017/10/13/que-signifie-disruptif-et-pourquoi-tout-le-monde-sort-ce-mot_1602934/

PLATO (1849), Œuvres, vol. VI, Paris, Rey et Gravier.

POINCARÉ, Henri (1913), Dernières pensées, Paris, Flammarion.

PONGE, Francis (1961), Méthodes, Paris, Gallimard.

PROST, Christine (1989), “Nuits, première transposition de la démarche de Xenakis du domaine instrumental au domaine vocal,” Analyse Musicale, no. 15, p. 18–25.

REGNAULD, Irénée (2018), “La démocratie à l’épreuve de la ‘disruption’,” Socialter, no. 29, p. 19–21.

REUX, Cédric (2010), “Étude d’une méthode d’amortissement des disruptions d’un plasma de totomak,” doctoral thesis, École polytechnique de Palaiseau.

REVAULT-D’ALLONNES, Olivier (1975), Xenakis—Les Polytopes, Paris, Balland.

RICŒUR Paul (1980), “Le récit de fiction,” in Dorian Tiffeneau (ed.), La Narrativité, Paris, CNRS, p. 35–44.

SATPREM (1970), Sri Aurobindo ou l’aventure de la conscience, Paris, Buchet/Chastel.

SHUSTERMAN, Richard (2020), Les Aventures de l’homme en or, Paris, Hermann.

SOLOMOS, Makis (1996), Iannis Xenakis, Paris, Mercuès, P.O Éditions.

SOLOMOS, Makis (2013), “Iannis Xenakis,” in Nicolas Donin and Laurent Feneyrou (eds.), Théories de la composition musicale au XXe siècle, Vol. 2, Lyon, Symétrie, p. 1057–80.

TIAN, Tian (2021), “Xu Yi’s Qing: A Musical Interpretation of Taoist Thought,” Le GRIII, no. 8, 13 August.

TONNELAT, Marie-Antoinette (1971), Histoire du principe de relativité, Paris, Flammarion.

VALÉRY, Paul ([1894] 1973), Cahiers I, Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de La Pléiade.

VIDAL, Jean-Pierre (1975), Dans le labyrinthe de Robbe-Grillet, Paris, Hachette.

WEIBEL, Peter, BRÜMMER, Ludger and KANACH, Sharon (eds.) (2020), From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today, Berlin, Hatje Cante Verlag, https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today

XENAKIS, Iannis (1955–6), Pithoprakta for 49 musicians (score BH03801), London, Boosey & Hawkes.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1963), “Musiques Formelles,” La Revue Musicale, no. 253–4, Paris, Richard-Masse, p. 295.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1965), “La voie de la recherche en question,” Preuves, no. 177, p. 25–32.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1967), Nuits: Phonèmes sumériens, assyriens, achéens et autres, for 12 mixed voice soloists or mixed voice choir (score 17045), Paris, Salabert.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1971), Musique. Architecture, Paris, Casterman.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1971a), Mikka (score 17078), Paris, Salabert.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1972), “Rationalité et impérialisme,” L’Arc, no. 51, p. 56–8.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1976), Mikka “S” (score 17252), Paris, Salabert.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1979), Arts/Sciences: Alliages, Paris, Casterman.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1981), “Le temps en musique,” Spirales, no. 10, p. 8–12.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1981a), Embellie (score 17528), Paris, Salabert.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1985), Arts-Sciences, Alloys: The Thesis Defence of Iannis Xenakis before Olivier Messiaen, Michel Ragon, Olivier Revault d’Allonnes, Michel Serres, and Bernard Teyssèdre, translated by Sharon Kanach, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1986), “Ouvrir les fenêtres sur l’inédit,” in Jean-Pierre Derrien (ed.), 20e siècle—Images de la musique française, Paris, Sacem / Papiers, p. 52–60.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1987), “Mycenae-Alpha 1978,” Perspective of New Music, vol. 25, no. 1–2, p. 12–15.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1988), “À propos de Jonchaies,” Entretemps, no. 6, p. 133–7.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1992), Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Music (rev. ed.), additional material compiled and edited by Sharon Kanach, Stuyvesant, New York, Pendragon.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1994a), Kéleütha: Ecrits, preface and notes by Benoît Gibson, Alain Galliari (ed.), Paris, L’Arche.

XENAKIS, Iannis (1994b), “Musique, espace et spatialization: Interview of Iannis Xenakis by Maria Harley [Paris, 25 May 1992],” translated by Marc Hylan, Circuit: Musiques contemporaines, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 9–20, https://doi.org/10.7202/902104ar

XENAKIS, Iannis (1996), Musique et originalité, Paris, Séguier.

XENAKIS, Iannis (2001), Texte du CD Metastasis, Pithoprakta, Eonta, Le Chant du Monde, LDC 278368.

XENAKIS, Iannis (2006), Transformation d’un combat physique ou politique en lutte d’idées, Madeleine Roy (ed.), La Souterraine, La main courante.

ZELLER, Hans Rudolf (1987), “Xenakis und die Sprache der Vokalität,” Musik-Konzepte, no. 54–5, p. 7–15.

1 This chapter was translated in January 2023. A previous version of this article was originally written in French for an edited collection, see: Castanet, forthcoming. We thank Éditions universitaires de Dijon for authorizing its publication in English in the present volume.

2 Nietzsche, 2007, § 1 [Plus on devient musicien, plus on devient philosophe]. All translations of cited excerpts are by Sharon Kanach, unless otherwise noted.

3 Baudelaire, 1980, p. 797 [le transitoire, le fugitif, le contingent, dont l’autre moitié est l’éternel et l’immuable].

4 After 1945, one may cite the works of Giacinto Scelsi (1905–88), John Cage (1912–92), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007), György Ligeti (1923–2006), and La Monte Young (b. 1935).

5 Xenakis, 1994, p. 101 [l’espace hors-temps; le flux temporel].

6 Cf. Castanet, 2014, p. 15–16 [vision poétique].

7 Stemming from Varese’s philosophy, this expression of art-science was used by Xenakis in the last sentence of his essay entitled “Towards a philosophy of music” (Xenakis, 1971, p. 119; in English, Xenakis, 1992, p. 241). Furthermore, the publication of Xenakis’s 1976 defense for his Doctorat d’État was titled Arts/Sciences: Alliages, (Xenakis, 1979; in English, Xenakis, 1985).

8 Bachelard, 2017, p. 12 [tout ce que peut espérer la philosophie, c’est de rendre la poésie et la science complémentaires, de les unir comme deux contraires bien faits].

9 “The public is struck by lightning when hearing a work by Xenakis” [Le public est foudroyé lorsqu’il entend une œuvre de Xenakis], his teacher, Olivier Messiaen (1908–92), confessed (remark published on 14 February 2011 on the blog “Le regard de Claude Samuel,” which is no longer active). As for his student at the University of Paris 1 (Panthéon Sorbonne, Saint-Charles), Pascal Dusapin (b. 1955), noted that “all the ‘pedagogical art’ of Xenakis consisted in upsetting the complicity of his listener” [tout “l’art pédagogique” de Xenakis consistait à mettre en désordre la complicité de son auditeur] (Dusapin, 2001, p. 90).

10 Cf. Solomos, 2013, p. 1058–70.

11 Matossian, 1981, p. 108.

12 See, for example Weibel, Brümmer, and Kanach, 2020, p. 417–57.

13 It should be noted that Albert Einstein (1879–1955) is often credited with having the audacity to reduce time to a fourth dimension (cf. Einstein, 2001).

14 “We live in a four-dimensional space-time continuum” [Nous vivons dans un continuum espace-temps à quatre dimensions], he liked to conclude his various demonstrations (Einstein, quoted by Barnett, 1951, p. 97). More poetically, did not Arthur Koestler (1905–83), the Hungarian-born novelist, demonstrate that, like Van Gogh’s (1853–90) unfolding of the skies, Einstein’s notion of space ultimately suggested a true “act of creation”? (Arthur Koestler, 1964).

15 This term, which corresponds perfectly to Xenakis’s temperament, is also used in the field of nuclear fusion as an abrupt interruption of the current generated by thermonuclear plasma (cf. Reux, 2010). We will also note that in the twenty-first century, the word disruption has been used by diligent shareholders of global marketing and has been abundantly taken up by the international media to circumscribe “a dynamic methodology oriented towards creation” [une méthodologie dynamique tournée vers la création]. Challenging conventional uses, the general idea of disruption would then aim to “give birth to a creative ‘vision’ of radically innovative products and services” [accoucher d’une “vision” créatrice de produits et de services radicalement innovants] (Pezet, 2017).

16 Bayle, 1993, p. 235–36 [D’être distribuée finement le long des nervures du temps. Plus seulement la gamme des chocs, des coups successifs, des décisions, locales, discontinues. Plus de mot, de note. Mais possibles le flux, un vent, une température, un mouvement qui parcourt l’espace, le définit, l’enveloppe, le représente].

17 “This term ‘Art,’ for Xenakis, refers to the artifex, to the creator” [“L’art,” ce terme renvoie chez Xenakis à l’artifex, au créateur] (comment by Olivier Revault d’Allonnes, 1975, p. 29).

18 Cf. Bujic, 1997.

19 In Giacinto Scelsi’s obituary in The Guardian on 23 August 1988, an unnamed journalist noted that the Italian composer-poet had said of his relationship to Iannis Xenakis: “We are both digging a tunnel. But we began far apart from each other. Neither knows exactly where he’s going, but perhaps one day, we will meet in the middle.” (cf. Castanet, 2023, p. 287).

20 Xenakis, Naama (1984) (24 September 2014), Elisabeth Chojnacka (harpsichord).

21 Program note (anonymous) of the creation of Naama, Luxembourg, Studio RTL, 20 May 1984. The composition of this work by Xenakis certainly is due to a “clever mixture of entrepreneurial spirit and new technologies” [astucieux mélange d’esprit entrepreneurial et de nouvelles technologies]. Metaphorically speaking, showing strategic marks of “radical innovation” [innovation radicale], its aesthetics can thus be akin to one of the definitions of “disruption” given by Régnauld, 2018, p. 6.

22 Chojnacka, 2008, p. 145.

23 We addressed this point in the conference entitled “Flux de forces et forces de flux dans la musique de Tristan Murail” [Fluxes of forces and forces of fluxes in the music of Tristan Murail], at the international conference Messiaen/Murail, Voyage à travers le son, La Grave, Festival Messiaen au Pays de la Meije, 27 July 2017 (significantly elaborated, this text was later published in Castanet, 2018 and developed in Castanet 2024).

24 Nietzsche, [1908] 1993, p. 1156.

25 Alquié, 1987, p. 106 [l’esprit ne peut engendrer le temps. Mais il peut le dominer, atteindre l’éternité à partir de laquelle le temps devient pensable].

26 Bachelard, 1948, p. 303.

27 Cf. Delalande, 1997, p. 126.

28 Cf. the chapter “Temps” in Valéry, [1894] 1973.

29 See, for example, the beginning of the score of Mists (1981) for piano, the more or less licentious apparatus rendering the sometimes canonical and sometimes arborescent arrangements technically realized from numerical sequences. (cf. Castanet, 1986). See also Chapter 19 in this volume.

30 Dorian title of a work for large orchestra composed in 1991 by Xenakis. Obviously, Roàï invites one to interpret its generic expression in a gigantic way, embracing—etymologically speaking—the universal idea of “flux” and “reflux.” Similarly, Sea-change (1997) for orchestra refers to the “return of the tide.” In the same vein, animated by a flux with a spellbinding aura—a pulsating current highlighting the essential qualities of the protagonists—N’Shima (1975), written for two mezzo-sopranos and instrumental quintet, attempts to legitimize the etymological character of its title (“breath” in Hebrew).

31 Cf. Revault d’Allonnes, 1975.

32 Equipped with a computer system to assist music composition through drawing, this mini-computer was conceived by Xenakis at the end of the 1970s. Titled Mycènes Alpha (1978), his first work for stereophonics and projection was based on a whole network of diverse lines stemming from very inventive spatio-linear drawings (cf. Xenakis, 1987, p. 12–15).

33 Compagnon, 1998, p. 143 [Nommer, c’est isoler dans un continuum].

34 We have in mind Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951), Ivan Wyschnegradsky (1893–1979), Pierre Boulez (1925–2016), Iannis Xenakis, Giacinto Scelsi, Claude Ballif (1924–2004), Jean-Claude Risset (1938–2016), Gérard Grisey (1946–98), Tristan Murail (b. 1947), François Leclère (1950–2015), and many others.

35 For the composer and conductor Gilbert Amy (b. 1936), “continuous/discontinuous” [continu/discontinu] and “periodic/aperiodic” [périodique/a-périodique] are equivalent. Cf. Michel (ed.), 2002, p. 119.

36 Greimas and Courtès, 1979, p. 101.

37 On this topic, see Durand, 1982, p. 338.

38 Ligeti’s term referring to his own music, awakening “the impression of flowing continuously, as if there were neither beginning nor end” [l’impression de s’écouler continûment, comme si il n’y avait ni début ni fin] (Cf. Ligeti, 1974, p. 110).

39 Works by Messiaen, Stockhausen, Boulez, Risset, George Crumb (1929–2022), Tōru Takemitsu (1930–96), Bayle, Emmanuel Nunes (1941–2012), Hugues Dufourt (b. 1943), Murail, Toshio Hosokawa (b. 1955).

40 Whereas the notion of evolution carries promising attributes of a “function of opening [...] involution signals, in some way, the closing of the discourse” [fonction d’ouverture […] l’involution signe, en quelque sorte, la clôture du discours] (Miereanu, 1998, p. 38).

41 On this subject, see Castanet, 1998, p. 85–103; Castanet, 2000; Castanet, 2003.

42 “The function of any labyrinth is to abolish time in a magic space where duration merges with the landscape and the walk which crosses it” [La fonction de tout labyrinthe est d’abolir le temps dans un espace magique où la durée se confond avec un paysage et la marche qui la traverse] (Vidal, 1975, p. 23).

43 “Often, utopias guide us towards reality: a spiral-work, a labyrinth-work, such are the images that reflect the complexity and the infinitude of the relations of the system and the idea” [Les utopies, souvent, nous guident vers la réalité : l’œuvre-spirale, l’œuvre-labyrinthe, telles sont les images qui reflètent la complexité et l’infinitude des relations du système et de l’idée], noted the composer of Poésie pour pouvoir (Boulez, 1989, p. 390).

44 George N. Gianopoulos, composer, “Iannis Xenakis – Persephassa for Six Percussionists (1969) [Score-Video],” 20 April 2018, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=osw8Cr58cXs

45 In the manner of the semiologists, we prefer to give to the word “poetic” a sense close to its classical meaning. Umberto Eco (1932–2016) noted in this respect: “it is not a system of rigorous rules (the Ars Poetica as an absolute law) but the operative program that the artist proposes to himself each time; the work to be done, such as the artist, explicitly or implicitly, conceives it” [ce n’est pas un système de règles rigoureuses (l’Ars Poetica en tant que loi absolue) mais le programme opératoire que l’artiste chaque fois se propose ; l’œuvre à faire, telle que l’artiste, explicitement ou implicitement, la conçoit] (Eco, 1965, p. 10).

46 Cf. Xenakis, 1994, p. 137 (first publication: Le Nouvel Observateur, 25–31 May 1984).

47 Bergson, 1994, p. 155.

48 Nietzsche, [1908] 1993, p. 834.

49 This idea had already been advanced in Xenakis, 1985, p. 104.

50 Amy cited in Michel, 2002, p. 105 [ni vous, ni le meilleur “écouteur” ne pouvez vous targuer de ne pas avoir une fraction de seconde de distraction, et donc d’introduire de la discontinuité dans une écoute apparemment lisse]. Xenakis had declared for his part: “the smooth continuum […] abolishes time, or rather time in the smooth continuum is illegible, unapproachable” [le continu lisse […] abolit le temps, ou plutôt le temps dans le continu lisse est illisible, inabordable] (Xenakis, 1996, p. 37).

51 Conducted by Hermann Scherchen, this work was boo-ed at its premiere in Munich in 1957. For the record, Xenakis calls this master of Gravesano “the midwife of music” [l’accoucheur de la musique]. Scherchen was also responsible for the premieres of two other works by Xenakis: Achorripsis (1956–7) (in Buenos Aires in 1958) and Terretektorh (1965–6) (in Royan in 1966).

52 Based on the principle of Brownian motion and on the law of large numbers bequeathed by Jacques Bernoulli, the principles of the work are founded on Maxwell-Boltzmann’s statistics, Gauss’s law (for the distribution of the speed of the glissandi) and Poisson’s Law (for the minimum number of relations that can exist between the sound events present). Performed by the Orchestre national de l’ORTF, conducted by Maurice Le Roux. Recording available at Pour ceux que le langage a désertés, “Iannis Xenakis – Pithoprakta (1955–56) pour 49 musiciens” (25 September 2020), Youtube,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxAakHDWjrw53 Xenakis, 1971, p. 120.

54 Let us note that the Xenakian practice of ”continuous transformations” was especially present in his works between the years 1955–68. Jérôme Baillet has pointed out the paradoxical character of that process because, for him, they were not at all opposed to a feeling of “statism” [statisme] (Baillet, 2003, p. 241).

55 Cf. text for the CD, Xenakis, 2001, p. 8. In addition, the musician wrote in his unpublished preliminary notes that the score of Pithoprakta implemented a “set of energetic transformations” [un ensemble de transformations énergiques]. Cf. Archives Xenakis, Carnet 23, consulted by the author at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris in 2002.

56 As expressed by Wilhelm Wundt, taken from Grundriss der Psychologie [fourth edition of 1897] consigned in French by Lalo, 1939, p. 184.

57 Boulez, 1989, p. 366.

58 Xenakis, 1985, p. 73. The same idea can be found in “Entre Charybdis et Scylla” in Xenakis, 1994a, p. 88–93.

59 Cf. Lassus, 2010, p. 66.

60 Note that the etymology of the title Herma (1961) refers to—among other things—the word “link.” It should be noted that for this work for piano, Xenakis relied on a trilogy of algebras: first, by which the operations outside time, including pitches, are practiced; second, temporal algebra, in which the events are embodied on the basis of metric time, statistically organizing the durations; and third, algebra in time, combining the two preceding ones, putting in relation the sound movements in their evolution. Cf. Deliège, 2003, p. 521.

61 Xenakis, Tetras (1983) (28 April 2018), Arditti String Quartet.

62 Cf. Tonnelat, 1971, p. 436.

63 Analyzing Xu Yi’s Qing, Tian Tian showed that, in the first section of that work, the glissando was related to the Yang and that the pizzicato represented the Yin (Tian, 2021). Before the study, the author revealed that the Chinese composer was inspired by the theorist Xu Shangying’s book entitled Artistic Conception of Xi Shan’s Guqin Music.

64 Looking at the notes on his “correspondence of the arts” [correspondance des arts], it is easy to see that the technique of the “process of linked events” [processus d’événements enchaînés] was already present in Xenakis’s research at the end of the 1950s (cf. Archives Xenakis, Carnet 26, 1959, p. 75, consulted by the author at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris in 2002. This document is reproduced in Castanet and Kanach, 2014, p. 8.

65 Apart from the musical presence of breaths and cries, the micro-interval elements are enhanced with phonemes of Sumerian, Assyrian, Achaean origin. Complementary reading in Zeller, 1987.

66 In this context, Christine Prost speaks of continuous “braids” [tresses] (Prost, 1989).

67 Xenakis, Nuits (1967), world premiere performance on 7 April 1967 by soloists of the ORTF chorus and conducted by Marcel Couraud. For recording, see vox_ritualis, “Xenakis—Nuits (phonèmes sumériens, assyriens, achéens et autres)” (27 July 2018), YouTube,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nyg7tMV3oyQ68 Márta Grabócz has notably worked on recurrent expressive elements within a work or on specific data that crystallize the language of this or that composer. For more information on this subject, see Grabócz, 1998, p. 77–8.

69 It should be noted that the howling sirens that Xenakis heard during the war in the streets of Athens during the unforgettable German air raids—were from the same type of siren dear to Edgard Varèse’s instrumentarium (listen to Ionisation (1929–31)). The composer-architect also used them in some important pieces for orchestra (such as Terretektorh) or in Persephassa (for percussion sextet).

70 Xenakis, 1971, p. 27 [un cas particulier de son à variation continue]. See also note 78 of the present chapter.

71 This image may remind us of the etymology of the title of Achorripsis (1956–7), since it comes from the Dorian ichos (sound) and ripseis (spurts).

72 Performed by the Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg, with Arturo Tamayo as conductor. See Feinbird, “Iannis Xenakis—Tracées (1987)” (10 June 2021), YouTube,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXIYFOUKtDc73 Xenakis, 1994a, p. 58.

74 Aristotle, 2015, p. 250.

75 According to conductor Pascal Rophé in Barthel-Calvet, 2011b, p. 6.

76 Kanach and Lovelace, 2010, p. 103, Pl. 81.

77 In 1986, Xenakis explained these alternating “abrupt caesura” [brusque césure], “arborescences of glissandi” [arborescences de glissandi], “idea of fluid” [idée de fluide], and “foreign element” [élément étranger] … He also legitimized the structuring element of “‘before-and-after’ the cut” [coupure “avant-après”] (Xenakis, 1988, p. 133–7). Xenakis, Jonchaies (1977), performed by the Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg, conducted by Arturo Tamayo. See Pour ceux que le langage a désertés, “Iannis Xenakis – Jonchaies (1977) pour grand orchestre” (10 January 2020), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxAakHDWjrw

78 Ricœur, 1980, p. 38 [rupture d’un ordre au bénéfice d’une situation terminale, conçue comme restauration de l’ordre].

79 Francès, 2002, p. 203.

80 In our opinion, Xenakis’s mathematical formulas could be used as a kind of “compositional heuristics” [heuristique de la composition] (cf. Mandolini, 2012, p. 55).

81 Bachelard, 1943, p. 62 [pas d’espace sans musique parce qu’il n’y a pas d’expansion sans espace].

82 Valéry, [1894] 1973, p. 1029.

83 This technique is also present in Phlegra (1975), Jonchaies (1977), Dikthas (1979), three scores—amongst many others—that weave a continuum, notably of pitches, thanks to this homogeneous technique of “non-break.” Note that at the beginning of the 1970s, the dichotomy “break—continuous flux” [coupure—flux continu] was treated by Deleuze and Guattari, 1972.

84 Performance Notes, in French and English, Xenakis, 1971a. For the record, the notion of “continuously varying sounds” [sons à variation continue] has been deployed in many Xenakian demonstrations—see the elements of study that originally appeared at the heart of his formalization of music in 1963 (Xenakis, 1981, p. 27).

85 As Denis Diderot (1713–84) related it in his way: “There is, between unity and uniformity, the difference between a beautiful melody and a continuous sound” [Il y a entre l’unité et l’uniformité la différence d’une belle mélodie à un son continu] (Diderot, 1994, p. 760).

86 Xenakis, 1994, p. 13 [C’est l’intérieur du temps qui compte, non sa durée absolue; ce contenu où le temps est articulé indépendamment et simultanément par divers événements musicaux].

87 Irvine Arditti on violin. For a recording, see belanna000, “Iannis Xenakis – Mikka (w/ score) (for violin solo) (1971)” (3 August 2015), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ifxs3TBSSAs

88 Quoted from the composer’s Performance Notes (in both French and English) in Xenakis, 1976, p. 5.

89 It will be remembered that, after having addressed the notion of “seizing” [capture] of energy, Deleuze and Guattari put forward the notion of “molecular flickering” [clapotement moléculaire] (Deleuze and Guattari, 1980, p. 326–7). This idea had already been advanced by Deleuze in 1978 during a conference relating to “musical time” [le temps musical]. During his lecture, the philosopher then evoked the “molecular becoming of music” [le devenir moléculaire de la musique] (Deleuze, 2015, p. 241). Xenakis’s reference was made in the previously mentioned lecture on 7 May 1986 at the Université de Rouen Normandie.

90 Cf. Solomos, 1996, p. 66–7. In this book, arguing that the that glissando originated from a “gestural character” [caractère gestuel], the musicologist postulates that “the Xenakian gesture par excellence is the linear glissando” [le geste xenakien par excellence est le glissando linéaire] (p. 155). Concerning the idea of the glissando representing the “refusal to make” [le refus d’opérer] a “choice” [choix] in the “continuum,” see Cazaban, 2000, p. 133–4. Concerning the temporal virtues of sound art, see Xenakis, 1981, p. 9–11.

91 Bachelard, 1989, p. 123–4 [un processus homogène n’est jamais évolutif. Seule une pluralité peut durer, peut évoluer, peut devenir. Et le devenir d’une pluralité est polymorphe comme le devenir d’une mélodie est, en dépit de toutes les simplifications, polyphone]. With regard to the thinking of Bachelard with that of Xenakis, see Lassus, 2010.

92 Barthes, 1995, p. 263.

93 In a preliminary note written in view of his composition of Metastasis, Xenakis writes: “The repetition of a rhythmic unit is impossible because I break the order” [La répétition d’une unité rythmique est impossible car je brise l’ordre]. Archives Xenakis, Carnet 13, dated 30 January 1954, p. 10, consulted by the author at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 2002.

94 Cf. Hasegawa, 2012, p. 231–43.

95 Garth Knox on viola. Recording available at George N. Gianopoulos, composer, “Iannis Xenakis – Embellie for Viola (1981) [Score-Video]” (14 May 2018), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6hW0R7Nrw0

96 Benny Sluchin on trombone. Recording available at belanna000, “Iannis Xenakis – Keren (w/ score) (for trombone solo) (1986)” (3 August 2015), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCBclgx_Jvc.

97 Cf. Barthel-Calvet, 2011a, p. 10.

98 If the first part (called “A”) of Rebonds progressively installs a kind of “perpetual movement” with an expressly continuous dominant, the second part (called “B”) animates a rhythmic apparatus galvanized by the bongos. The latter are play in regular cells that are often destabilized by heavy bass-drum strokes, thanks to consciously shifted accents. Within this last phase of relatively primitive aesthetics, Xenakis was preoccupied, using a faster tempo, with imposing a quintet of woodblocks to break the discursive flow on several occasions.

99 In fact, playing as much on the micro-detail as on the macro-structure, the abundant arsenal put in place in different sections of Nuits confirms the shaping of a stylistic relief placed entirely under the generic aegis of the continuous-discontinuous—what Joëlle Caullier calls “the intermingling of immobility-directionality” [l’entremêlement immobilité-directionnalité] or “the conjunction of perennity-temporal transience” [conjonction pérennité-fugacité temporelle] (Caullier, 1988, p. 64).

100 Xenakis used this image when presenting his work Embellie for viola, a solo dedicated to Geneviève Renon-McLaughlin (Xenakis, 1981a, p. 1). In addition, the composer confided: “According to the Petit Larousse dictionary, an ‘embellie’ is a clearing that occurs during or after a gust of wind” [D’après le Petit Larousse, “l’embellie” est une éclaircie qui se produit pendant ou après une bourrasque] (remarks reported after the premiere of the work by Claude Samuel in Le Matin, 2 April 1981). The dynamic metaphor of the storm is also referenced in the context of his composition Terretektorh: indeed, on one of the preparatory sketches of the work, one can read “storms of maracas” [des tempêtes de maracas]: Cf. Xenakis Archives, Paris, consulted by the author at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 2002; document reproduced in Kanach and Lovelace, 2010, p. 18.

101 Originally derived from the Latin incisa, the French word “incise” means “cut.” But if in music, the term denotates “a group of notes forming a fragment of a rhythm” [un groupe de notes formant un fragment d’un rythme], it can also mean “a phrase of little scope, forming a sort of parenthesis in a longer phrase” [une phrase de peu d’étendue, formant une sorte de parenthèse dans une phrase plus longue] (according to the Dictionnaire de la langue française-lexis, Paris, Larousse, 1979, p. 945) One must bear in mind that Boulez, who obviously borrowed some notions from Henri Poincaré (1854–1912) without quoting him (cf. Poincaré, 1913, p. 137–41), considered that the continuum could be manifested by the possibility of “cutting” [couper] space according to certain laws: “the dialectic between the continuous and discontinuous passes by the notion of ‘cutting’; I will go so far as saying that the continuum ‘is’ this very possibility, because it contains both the continuous and the discontinuous: the cut, if one wants, changes the continuum’s sign.” [la dialectique entre continu et discontinu passe donc par la notion de “coupure” ; j’irai jusqu’à dire que le continuum “est” cette possibilité même, car il contient, à la fois le continu et le discontinu : la coupure, si l’on veut, change le continuum de signe. Plus la coupure deviendra fine, tendra vers un epsilon de la perception, plus on tendra vers le continu proprement dit…] (Boulez, 1964, p. 95).

102 Cf. Castanet, 2009.

103 Performed by the New London Chamber Choir, conducted by James Wood. Recording available at Ryan Power, “Iannis Xenakis – Knephas (Audio + Full Score)” (5 April 2022), YouTube,