4. Private Life

©2024 Leslie Howsam, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0392.04

Eliza Orme thought Christmas cards were stupid. She much preferred ‘a nice hearty greeting’ in the form of a letter, ‘instead of one of those senseless cards that we are inundated with—Cats—heartseases—frogs in tail coats—castles—all manner of things in earth and heaven with the ever recurring “happy Xmas” printed beneath’. So, with an almost audible snort, she told her friend Sam Alexander in 1887, in response to his having written a proper letter to her mother. She also delighted in funny or poignant happenings, especially if they involved the Irish dialect: In an 1889 letter to Sam from Ireland, she observed of ‘these fascinating Celts’ that ‘they use our longest words in the most eccentric way—just off the exact grammatical line—and it results in a mixture of pathos and humour which conquers me “entirely’’’. She continued: ‘Yesterday I was talking to a poor tenant who lives in a poor mud hovel not fit for a pig. Wife and innumerable children. I had been thinking that if I had been in his place or in his wife’s place suicide would have been my cure at once. But when we left the cabin he attached himself in a most sociable way and discoursed politics with such intelligence that I began to see why his life was interesting enough to keep him alive’. She took even more pleasure in beloved friends. Later in life, she recalled seeing in the new year of 1900 with Sam and his dog, and some of her family including their own dog Rhoda: ‘we walked down Tulse Hill and fancied we heard St Pauls Cathedral ringing in the new century. We heard all sorts of strange noises and the vague hum of the great city’. Eliza’s letters to Sam have little to do with her status as a professional person making her mark in public life. They do, however, give us a whisper of the voice that her friends and family knew, a tart but warm, laughing but thoughtful voice that she must consciously have set aside when dealing with barristers, speaking on suffrage platforms, and strategizing at Liberal committee meetings.

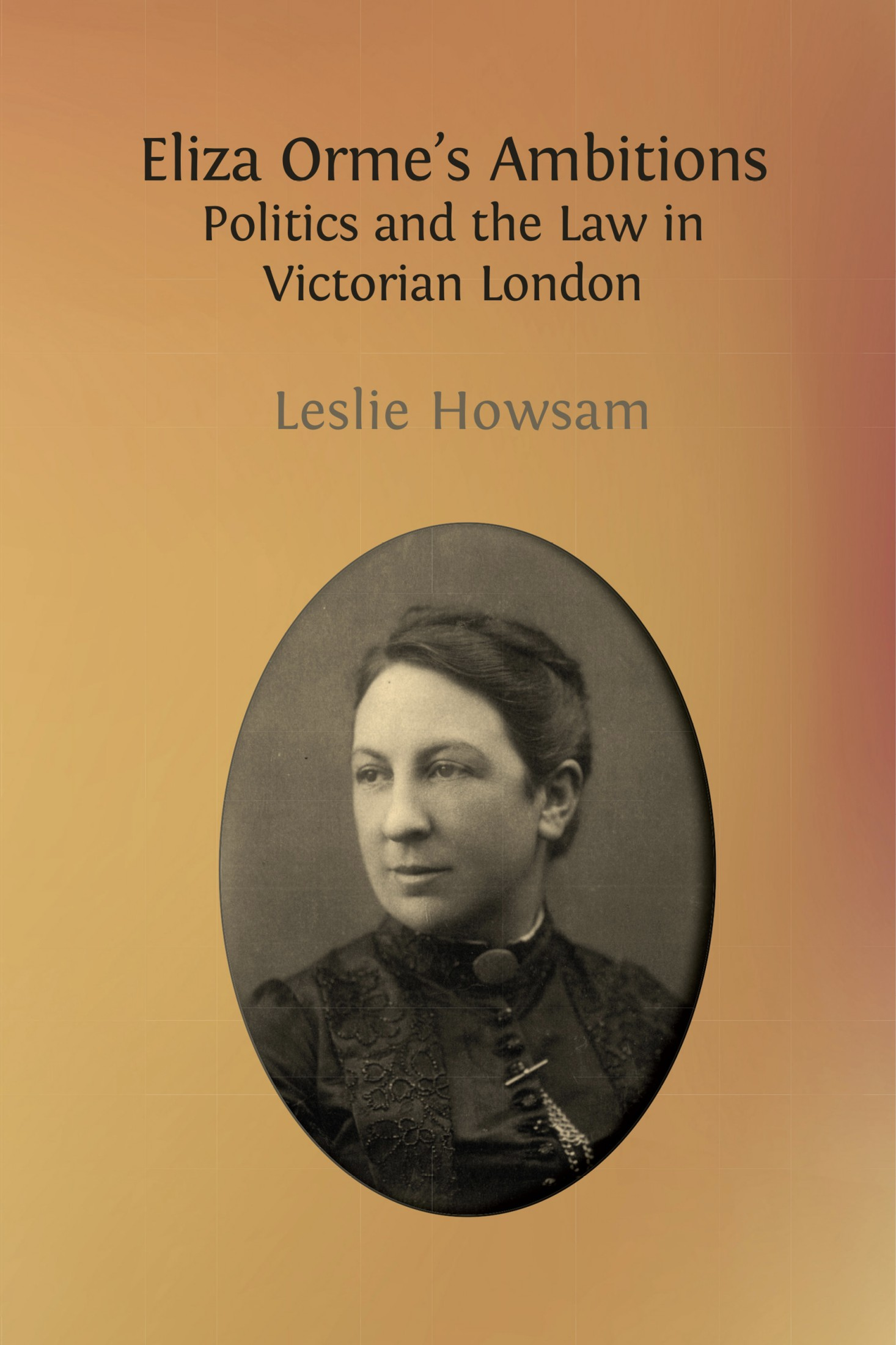

To put a face to that voice, we can look at the photograph taken in 1889, when Eliza Orme was forty, at The Cameron Studio, in Mortimer Street in central London. (That was not the studio of the famous Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, but of her son, Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, who specialized in portraiture.) She turns to one side, faintly smiling and serene, her dark hair pulled up and back from a high forehead. She has a strong nose and chin, elegant eyebrows. She is conventionally dressed, as befits her decided views on the extremes of attire adopted by some of her contemporaries who styled themselves the ‘new women’. I wonder how it came to be taken. Did Cameron invite her, or did Eliza commission the portrait herself, perhaps to commemorate achieving the law degree a few months earlier? I think it must have been a private commission because I have never seen a nineteenth-century reproduction of this photograph—although now (thanks to me) it adorns various websites celebrating the first women lawyers in Britain and it was even reproduced in colour, in oil paint on canvas (by the artist Toby Ursell), as part of one such celebration. A framed print hangs in my office. I am forever grateful to Pierre and Hélène Coustillas, for giving me a scan of the original. They told me it had been inscribed by Eliza to her Australian nephew David Orme Masson and inherited by Professor Masson’s granddaughter Jenny Young. So it seems likely that Aunt Eliza had a few copies made for family members and friends. The Massons in Edinburgh might have received a copy, as well as the Bastians in Manchester Square, and the Foxes in Cornwall. Maybe one sat on a table in Reina Lawrence’s Belsize Avenue home. Perhaps another adorned the Oxford rooms of the scholar Samuel Alexander. Eliza may have had a whole ‘other family’ in the town of Buxton: perhaps they, whoever they were, received a copy of the portrait too. But this is all speculation: she remains elusive. Her public persona—which we will come to in Chapter 5—was, necessarily, so severe (although the severity was tempered by an acerbic humour that I think she cultivated) that the giddiness, the wit, and the warmth of her few surviving personal letters come as a delightful surprise. I like to think the photograph shows a bit of both.

Fig. 5 Eliza Orme (1889, The Cameron Studio), ©The estate of Jenny Loxton Young.

When I wrote my 1989 article, I said that ‘no diary, letters, or other personal papers of Eliza Orme have survived’. Even back then, I should have known better. Most certainly I should have known about the businesslike letters to Helen Taylor at the London School of Economics, but I was distracted by other commitments and interests and had come to believe there was nothing to be found, so I stopped looking very hard. In my defence, I was never part of the network of historians working on the mid-Victorian women’s movement, where I might have got wind of the Taylor collection from a colleague. It would not be reasonable, though, to blame myself for not finding her letters to Samuel Alexander, even though at the time they were safely ensconced with that philosopher’s papers at the John Rylands Library in Manchester. Those I came across quite serendipitously, at home in 2020, through combining her name in a search engine with that of another of Alexander’s correspondents. The Rylands archivists had recently put a finding aid to his papers online, and the algorithm did the rest. (The archivists noted that she was one of the few correspondents to address him as ‘Sam’) Both the Taylor and the Alexander letters have to be seen on site at the relevant library, or else by way of a digital scan supplied by the staff in charge. Whereas her letter of 1884 to Susan B. Anthony (the one that gives news of Eliza’s mother as well as of her colleagues) was published in the National Woman Suffrage Association’s Report of their Washington convention, has been digitized, and is online. A few others have turned up in similarly unexpected places, but there is still not much. She wrote dozens of letters to George Gissing, but he kept none of them. I would give a lot to see any intimate letters (or even business letters) she might have written to Reina Lawrence. But if they ever existed those letters were most likely either tossed in a waste-paper basket or kept only to be destroyed later, in the course of a wartime paper drive.

The other thing that was unavailable when I began this research in the 1980s was the internet. Three decades and more after my first encounter with Eliza Orme, and my initial pursuit of her in the pages of Gissing’s published diary and letters, much is now available to me in my home office. I am glad I made those delightful but laborious visits—to London archives and record offices, to Somerset House where wills were lodged, to Warwick University in Coventry to see Clara Collet’s papers, and to the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane to see the census records—but even gladder that there is now an alternative. Census and other government records like birth and death certificates and wills are now readily available, for a small fee. The British Newspaper Archive and periodicals databases make millions of contemporary words, some of them identifying her by name, available through academic libraries. I have also become adept at online searches, entering either her full name, or ‘Miss Orme’, or sometimes just her surname, in juxtaposition with another word or phrase that identifies a person or institution. Much of what appears that way is about her public life, of course, but when she encountered someone who later became well-known—Christina Rossetti, Susan B. Anthony, John Stuart Mill, Beatrice Webb, to name a few—then the encounter might have been captured in some nineteenth-century book, and hence in the Internet Archive. Remarkable. But, accessible as all these things are, you first have to frame the question, and propose the juxtaposition.

The borderline between public and private is blurred when a woman’s accomplishment is unthinkable and most of the evidence undiscoverable. In that sense, the paid legal work in Chancery Lane in these decades might almost be considered part of her private life: those discreet services to barristers, taking on their intricate jobs at half-fees, were not advertised or (as far as I know) documented. Her availability must have been made known by word of mouth. For a couple of decades of her long life she was also a minor public figure, especially from the mid-1880s to the mid-90s beginning with the foundation of the Women’s Liberal Federation and then her appointment to a Royal Commission on Labour and later to a government committee on prisons. However she was not well enough known to develop an indelible reputation, like Josephine Butler or Millicent Fawcett. Indeed, the people who memorialized those other leaders may have consciously erased Orme’s name from the feminist record, or maybe subconsciously forgotten to include it, for reasons we will see in Chapter 7 with the messy split in the WLF that happened in 1892. At that time, the name of ‘Miss Orme’ was in the public eye while ‘Eliza’ was careful to keep her private life just that—private.

Family and Childhood

Census records show that Charles Orme was twenty-six when he married Eliza Andrews in 1832; she was sixteen. Directories and press advertisements reveal that he was a businessman in the liquor trade, a distiller with premises in Blackfriars that he had inherited from his own father. The business obviously prospered, since Charles supported a large family of eight children, a wife, a sister-in-law, and four live-in servants. Eliza gave birth to her first child at seventeen and her last at forty-one. As ‘Mrs Charles Orme’, she became well known for the informal salon she hosted in their house on Avenue Road in Regent’s Park on Friday evenings. Her guests included some of the leading artists and intellectuals of mid-Victorian London as well as people in the women’s suffrage movement. A third adult later joined the household in the shape of Georgina Patmore, the senior Eliza Orme’s ten-years-younger sister and a widow. I cannot help but notice some intriguing parallels between the Ormes’ arrangements and the central characters of A. S. Byatt’s wonderful novel tracing a handful of complex families from the 1890s through to the 1920s, The Children’s Book.

At this point, I must pause to say ‘mea culpa’ on my own behalf, but perhaps also gently critique the careless scholarship of some long-dead aficionados of the mid-Victorian literary world. In more than one sketch of Eliza Orme, I have followed those gentlemen in noting that the lawyer’s mother was governess to Elizabeth Barrett Browning before her marriage. This was fun: it was name-dropping, it was colourful—but it was not true and I should have checked up sooner. I based the error on historical accounts of Barrett Browning’s connections with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. As it turns out, the poet kept in touch with a former governess by the name of Charlotte Orme (always referred to as ‘Mrs Orme’ by Victorian convention), and it was that lady who effected an all-important introduction to the brotherhood. To confuse matters and explain how the mistake was made in the first place, Eliza Orme senior did have a rich network of relationships with the Pre-Raphaelites herself. A University College London Ph.D. thesis by Scott Lewis was my source for the correct information.

Back to the firmer ground of census records.

Eliza and her sister Beatrice were the youngest of the Orme children, so much so that their niece Flora Masson was a year older than Beatrice, and their nephew David just a few months younger when they were all still living together in that capacious house. The eldest son, Charles Edward Orme (1833–1912) became a surgeon; he remained a bachelor and lived with his parents for many years, and latterly with Eliza and Beatrice. The second son (and fifth child) was Campbell Orme, also a surgeon, again a bachelor. Born in 1842, six years before Eliza, he studied at St Bartholomew’s Hospital; in 1871 he was serving as ‘medical assistant’ at a mental hospital. Campbell Orme died at forty-one, on board a Royal Mail ship at Rio de Janeiro. At that point he was a medical officer with the Guinea Coast Gold Mining Company. Orme told Susan B. Anthony that the death had been a ‘great shock’ to her mother, adding ‘My brother was not publicly known at all, but he was deeply valued in his own family and after a long illness we thought he had recovered’.

Eliza Orme senior had already lost a child when Campbell died in 1883. Helen Foster Orme died in 1857 at the age of twenty when Eliza was only eight. Helen was a childhood friend of the poet Christina Rossetti. The record shows that she died in Hemel Hampstead, Hertfordshire, an agricultural market town outside London. Their sister Rosaline Masson named a child after Helen. Apart from these fragments, I know nothing of Helen’s life. I wonder if Eliza Orme’s poem, ‘Song’, might have been written to evoke her memory; it was first published in The Examiner in 1875: ‘I’m thinking of a fair face, The fairest ever seen; And I sigh good-bye to summer, And the glory of the green’. It could be about anybody, but it might be about Helen.

The Ormes’ eldest daughter was Rosaline, born three years after their marriage. In 1854, when Rosaline was nineteen and marrying David Masson, Christina Rossetti described the bride to a friend as ‘pretty, clever I imagine, and indescribably winning’. Rosaline and David lived with the family in the Avenue Road house for many years, and she gave birth to two children there before her husband was appointed to an important post in Edinburgh. The next daughter was Helen, then Julia Augusta Orme (1840–1928), who married the physician and psychologist-neurologist Henry Charlton Bastian (he later became Professor of Pathological Anatomy and of Clinical Medicine in University College London). The Bastians, in their turn, lived at Avenue Road after their 1866 marriage (and after the Massons had moved out); they were still there with two children for the 1871 census when Eliza was away teaching in Wiltshire. When they got their own London home it was in Manchester Square. The Bastians had five children. The third married sister was Olivia Blanche (1844–1930); she was just four years older than Eliza. Blanche married Howard Fox, a merchant and ship agent, and lived in Falmouth, in Cornwall. Howard came from a Quaker family; he was American consul in Falmouth and also acted as consul for Ecuador, Sweden, Norway and Denmark. There is evidence in Eliza’s and Beatrice’s later lives of a close relationship with the Cornwall family.

Last of all came Beatrice, born the same year that Helen died, 1857. Her oldest sibling Charles was twenty-five, her sister Eliza was eight. This daughter’s full name was Beatrice Masson Orme, just as some of the Masson, Bastian, and Fox children were given ‘Orme’ as their middle names. Beatrice attended University College London from 1879 to 1881 but does not seem to have graduated. She was active in various women’s rights causes, notably the Women’s Liberal Federation alongside her sister. Beatrice and Charles Edward Orme both lived with Eliza for decades, in Eliza’s homes in Chiswick (Bedford Park) and later Brixton (Tulse Hill). There is evidence in the letters to Sam Alexander and in George Gissing’s diary that the two sisters were close. It might be tempting to think that Beatrice’s role in her sister’s life became some combination of the ones that Eliza described in an 1897 article about how a professional woman organizes her life: ‘She has a house of her own with servants, one of whom is very probably a lady help or companion housekeeper, whose domestic tastes make the position pleasant as well as profitable. And very likely she helps a younger sister or niece to enter upon a life as useful and honourable as her own’.

It is difficult to discover much about schooling for the girls in this family and might be tempting to think that with such intellectual parents, aunts and uncles, brothers-in-law, and visitors, they hardly needed it. What we do know is that three of the sisters attended Bedford College for Women, as I mentioned in Chapter 2. We are on firmer ground with university education since both Eliza and Beatrice attended University College. As for their brothers, Charles Edward’s medical education as a surgeon would not have involved university training. It is unclear what qualifications Campbell Orme had to be a ‘medical officer’ but I have found no record of a degree. Certainly Eliza’s LL.B. was the highest educational attainment achieved by anyone in the family.

The Orme family had numerous cousins on the Andrews side. One who left a record of her visits to Avenue Road was Mabel Barltrop, who came to stay in the 1880s when Eliza was busy with her practice of law, her academic studies, and her political interests. Mabel was quite friendly with both Charles Edward and Beatrice Orme; she referred to the latter as ‘Bix’. Perhaps this was a family nickname, and if so it is delightful, if disconcerting, to learn that en famille Eliza was ‘Sili’. Despite using the goofy nickname, Mabel was in considerable awe of Eliza, who introduced her to people and took her along to lectures and suffrage meetings, even a private preview of an art exhibition at the Royal Academy. Mabel wrote to her fiancé that Eliza was someone who ‘should be worshiped’ and ‘a darling’, adding ‘You cannot fail to like and admire her. I think hers a lovely character, always doing something for somebody’. Mabel’s indignation about Eliza’s exclusion from law libraries at the Inns of Court also appears in this letter. (For the sources of these quotes and the extraordinary life of Mabel Barltrop, see Octavia Daughter of God: The Story of a Female Messiah and her Followers, by Jane Shaw. But that really is another story.)

Apart from the dubious documentation of the names of Charles Orme’s sisters Caroline (her husband was Henry Richard Brett, her dates were 1804–1867, and she had two children) and Emily (born about 1821) on genealogy websites, I have not found evidence of aunts, uncles, or cousins on the Orme side of the family.

The Ormes lived in three houses over the half-century I am interested in. All eight of the children were born at 16 Regent Villas (later 81 Avenue Road) in the Regent’s Park area of north London. For those who orient themselves to London through women’s suffrage landmarks, the house was not far from Langham Place. Others might find it more compelling to know that property on that street is now among the highest-priced in the United Kingdom. At some point in the early 1880s, they moved to a new suburb in the west-London area of Chiswick, called Bedford Park (number 2, The Orchard, to be exact). By that time the family had dwindled to the two parents and their three unmarried offspring Charles Edward, Eliza, and Beatrice, plus a couple of servants. Bedford Park was a railway suburb, which made it convenient for Eliza to commute to Chancery Lane and to her many political meetings around the country. Mary Ellen Richardson lived in the neighbourhood too, operating her retail business nearby. Bedford Park was also a newly developed garden suburb, which quickly became popular with writers who thought of themselves as ‘aesthetes’, and with a new generation of the same sort of artists and intellectuals who had frequented the house in Avenue Road. Then in the mid-1890s, after both parents had died, the three siblings moved to yet another new suburb, into the house at 118 Upper Tulse Hill, in the south London district of Lambeth.

I made a pilgrimage to Avenue Road early in my researches on Eliza Orme, and later went to Bedford Park in Chiswick. When I visited Tulse Hill it was in the 1990s, a rather turbulent time in the history of London’s race relations. I remember choosing Sunday morning for the expedition, feeling anxious about my safety, and taking great satisfaction in finding the house, a little shabby at that point but a substantial two-storey establishment. Although I am not now certain that it was the same one, since house numbering has changed.

Eliza Orme’s letters to Samuel Alexander indicate that she regarded both his family and Reina Lawrence’s as part of her own circle of aunts and cousins, siblings and nieces and nephews, and felt at home in their homes. Mysteriously, one of those letters to Sam hints at yet another such family. In the busy year of 1888, she told her friend that she had been taking care of her father ‘while Mamma and Beatrice are at Brighton. They return tomorrow and I join my other family at Buxton. I wish there were a few less of the Sol Cohen tribe there but Aunt Loo makes up for a few of them’. Then she was heading for Edinburgh for a family wedding and looking forward to ‘another luxurious rest at Buxton’ before making a political trip to Ireland. Buxton is a spa town in Derbyshire, in the Peak District of England. Who the Cohens were, what was objectionable about Sol Cohen or his connection, and what the charms of Aunt Loo might have been, I have no idea. And it is not for a lack of trolling through census records and old newspapers to try to figure it out. My searches did reveal one possibility: Reina Lawrence’s father was the nephew of a New York businessman by the name of Lewis Cohen. But both Lawrence and Cohen are common names. Perhaps the people in Buxton were what we now call a ‘chosen family’.

Friends and (perhaps) Lovers

If Eliza Orme was in a long-term intimate relationship with anyone, the most likely candidate is Reina Emily Lawrence. The sources that were first available to me did not provide any clues, and I must admit that back then I was probably thinking more in terms of men in her life. I had missed the 2008 biography of Gissing by Paul Delany, who stated definitely (but with no footnote) that the two women were a couple: ‘She never married, apart from a “Boston marriage” with Harry Lawrence’s sister’, he wrote. The term refers to a long-term intimate relationship between independent women who might, or might not, think of themselves as lesbians. In 2014 when I encountered Mary Jane Mossman, she told me about a new biography of George Gissing that referred to the relationship. I now realize that she meant Delany’s, since she mentioned it in a footnote to a 2016 article. But at the time, I assumed she was talking about the three-volume Heroic Life of George Gissing by Pierre Coustillas, published in 2011–12. I looked that one up and discovered Coustillas had referred to Lawrence as Orme’s ‘intimate friend’. Knowing that the phrase can denote anything from a close friendship to a fully-fledged sexual relationship, I decided to ask Professor Coustillas, with whom I was by this time corresponding. He replied that in all the years that he and Hélène Coustillas had been researching Orme as an associate of Gissing’s, they ‘had never for one moment entertained the idea of a sexual relationship’ between her and Reina Lawrence. I have since corresponded with Paul Delany, who was unable to supply any further information about his offhand remark. So there is still no hard evidence, one way or another.

Unlike Coustillas, I am quite prepared to entertain the idea. Beyond whatever offhand tittle-tattle Delany picked up in his researches on Gissing’s associates, there is the circumstantial evidence that when Eliza drafted her will in 1885, she made Reina her executor. At that time, Eliza was thirty-eight, in practice with Mary Ellen Richardson. Reina was twenty-four, still a law student herself. In a very short time, Miss Lawrence joined Miss Orme in the Chancery Lane law chambers. Jessie Wright’s visit in 1888 is evidence for that. When Eliza died in 1933, Reina duly executed her will, which had designated her as heir to Eliza’s real estate and residuary personal estate (the money and securities were left to Beatrice). In itself, the half-century duration of that friendship offers its own kind of evidence of intimacy, perhaps sexual, perhaps not. On the other hand, the two women never seem to have lived together under the same roof, except perhaps on holiday.

Reina Emily Lawrence (1861–1940) was born in New York City, third of the nine children of John Moss Lawrence, a London-born merchant who made his fortune in the business of printing playing-cards. The family was Jewish. It would be intriguing to know more about the mother, Emily Lawrence, who was born in Jamaica into the Asher family, and was married to someone called Mills before she married John Lawrence. Two of Reina’s siblings are notable: Esther Lawrence (‘Essie’) who became head of Froebel College, the progressive teacher-training establishment, and Henry Walton (‘Harry’) Lawrence, who became a partner with the publisher A. H. Bullen. (Lawrence and Bullen published some of George Gissing’s books, and it was while smoking at their after-dinner table that the novelist first encountered Eliza Orme, though he perhaps did not know that she was a family friend.) The Lawrences lived at 37 Belsize Avenue, in Hampstead, not far from the Ormes’ Avenue Road home. Eliza’s letters to Sam Alexander refer chummily to ‘the Belsize flock’, or to ‘spending every spare minute at Belsize lately’, especially around the time when the father died in 1888. Much later, in 1916 when Beatrice was sixty-seven (and there was a war on), she and Beatrice went to Belsize and ‘led a lazy and luxurious life there for ten weeks’.

Reina Lawrence earned her own LL.B. degree in 1893. Apart from working in the Chancery Lane chambers both before and after that event, she was active in local politics, serving on the Hampstead Distress Committee whose mandate was to help unemployed people. In 1907, when Lawrence was in her mid-forties, Parliament passed a Qualification of Women Act which enabled women to be elected to Borough and County Councils. In a by-election that same year Lawrence became the first woman elected as a councillor in London. She told voters that she was particularly interested in issues of housing, swimming baths, and infant mortality and assured them that she was not a suffragette. She was a candidate again but not re-elected in 1909, and continued to work, along with her sisters and others, on what Eliza described in a 1916 letter to Sam as ‘care committees’ and ‘similar philanthropic efforts’, adding ‘Reina has knowledge and experience and a capacity for seeing two sides of a question which is invaluable in this sort of work’.

I would like to end this section with an authoritative account of Reina’s ‘intimate friendship’—whatever its terms—with Eliza, but that is not possible. For the record, I do think it was probably a lesbian partnership, but I do not know, and incontrovertible evidence is difficult to come by. It is easier to show that they were political allies. In a letter to Sam (undated but possibly 1887, or maybe late in 1889), Eliza reported on a visit to Lyndhurst, in the New Forest area of Hampshire. Both Reina and Essie Lawrence were part of the party, with other members of that family including a baby grandchild. They all went to Ringwood by train, had lunch in ‘a pretty Inn on the fringe of the woods’ and then walked about twelve miles: ‘by keeping our shadows before us struck right through furze and thicket to Lyndhurst to a cosy tea in the Crown’. On another day they all went to a ‘radical demonstration’, that is, a political meeting where one of the speakers was the Irish Fenian John O’Connor Power. Eliza adds: ‘Reina and I do all sorts of Home Rule Union work rather like needle-work on Saturday. That is we do not exhibit unnecessarily before the eyes of the Boss’. It is not clear whether ‘the Boss’ was Reina’s formidable but clearly beloved mother, or one of her siblings, or someone else. Strategizing about the politics of Ireland is hardly intimate talk, but there is something about the suggestion of Saturdays and needle-work (that most female and feminine of occupations) that sounds like it excludes others from the conversation.

That’s about it for suggestive language in the Alexander letters, with one remarkable exception. If Reina was present at an 1890 house party in the Scottish highlands, then we might infer that the coded language Eliza used on that occasion, about women wishing to spend their time untrammelled by male relatives, was a roundabout way of saying they wanted to be alone with people who understood and accepted the nature of their relationship. The letter of 27 August 1890, from Ballachulish in the highlands of Scotland, is the most intriguing (and frustrating) of all Eliza’s letters to Sam. I have expended hours of energy, trying to track down the people she alludes to, to little or no avail. The tone of the letter, like many of the others, is light-hearted and teasing. The whole thing may well be an elaborate in-joke. Here it is, with irrelevant parts elided:

My dear Mr Alexander [she normally addressed him as ‘Dear Sam’ so this is mock formality]. Your Aunt has asked me to reply to your letter received today as she thinks that one who is an old friend will perhaps be able to do so more easily than she could and she does not think you would care for any of your cousins to be mixed up in the matter. She wishes you to understand in the first place that she values highly the warm family affection which prompts your earnest desire to come to Ballachulish … But it is best to speak quite plainly and so I have to tell you, she cannot do with you here at all. I am sure if you think of it you will see for yourself how totally unsuitable it would be. We are a party of ladies and just one man would be a mere clergyman`s tea-party. It is not that your Aunt does not respect men, and even boys, in their proper place but there is no denying that they are a terrible nuisance when women want to enjoy a real change and holiday. We spend our time quite informally taking our meals how and when we please. We dress in tam-o-shanters and ulsters without any worry or conventionality. We take long walks and roving expeditions almost every day. To be obliged to consider the whims and necessities of a man, however much we may like him personally, would be to change our present ease into the stiffness of Scarboro’ or Brighton. Do not suppose from what I have said that we are at all intellectually idle. We heard by chance of Cardinal Newman’s death and have frequently repeated ‘Lead Kindly Light’ to one another since. A copy of the Woman’s Gazette dated August 2nd has been lying on the table quite prominently and an odd volume of Waverley belongs to the house and can be read by us if we feel inclined to study Scotch history.

This is an extraordinary letter for a woman to write to a man in the 1890s, and very difficult to interpret. In the first place, I cannot work out which aunt she is referring to. Not the one who came to live with Sam and his mother from Australia, because that did not happen until later. Possibly the one who lived in Wiltshire, who wrote him a couple of letters in the 1890s, according to the handlist with the Alexander papers at the John Rylands Library. I cannot help wondering if this is an honorary aunt, and in particular if it might be Emily Lawrence, Reina’s mother, to whom Eliza refers affectionately in other letters as ‘the Old Lady’ (or just, the OL). But really the aunt does not matter. What matters is a ‘party of ladies’ who insist that they must be free to dress as they please (ulsters are a kind of informal overcoat with a cape, and tam o’shanters are flat hats originating in Scotland), eat meals when they feel like it, and go for long walks on a whim. All in the freedom of a rural cottage in the highlands, far from ‘the stiffness of Scarborough or Brighton’ (both seaside resort towns frequented by the two families). As for the remarks about Cardinal Newman’s poem and Walter Scott’s novel, I believe they are meant to be sarcastic, as is the reference to the Women’s Gazette and Weekly News of which Eliza was editor at this point.

Of course it is tempting to suppose that the ‘party of ladies’ indulged in some sexual intimacy that had to be concealed from the masculine gaze. On the other hand, it is a bit mind-boggling to think of such goings-on at a family outing which included members of at least two generations—though certainly not impossible. More likely, though, this is the same kind of arch humour that Eliza deployed in her other letters (such as the one quoted in the Prologue, where she implored him to attend a party at the Belsize Avenue Lawrence home and drink Oscary Wildey lemonade) but meant in this case to gently let Sam know why he would be unwelcome, while at the same time reminding him of everyone’s strong affection. If I am right, her forthrightness is noteworthy here. How many women of her generation were in a position to tell a man not to show up, merely because she and her friends would prefer a few days free of deferring to the sensibilities of people of his gender? None of the other members of the house party are named, so it is impossible to be sure, but I like to think they were the Lawrence women, mother and daughters, on a jaunt with their family friend Eliza Orme.

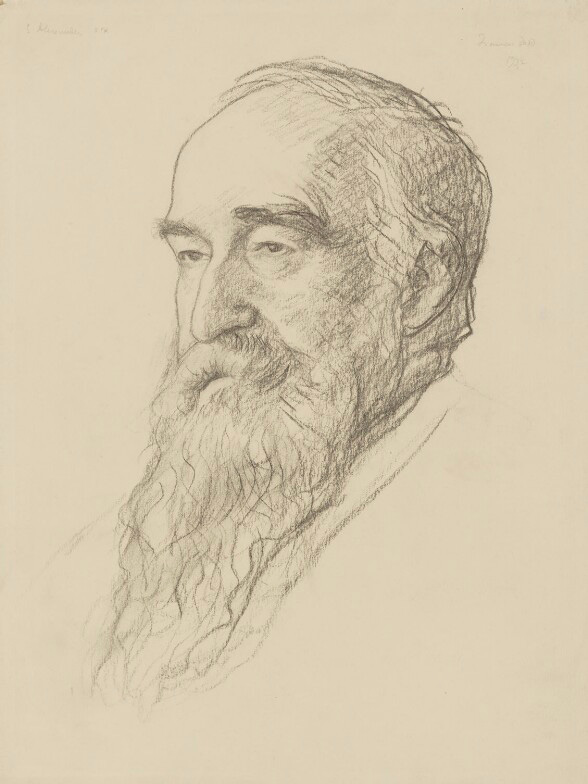

Samuel Alexander was Jewish, as were the Lawrences. He may have met them when he came to England from Australia, or perhaps he knew them before he arrived. I assume he encountered Eliza through Reina’s family, but I do not know for certain. Born in Sydney in 1859, the son of a saddler, he studied at the University of Melbourne and won a scholarship that took him to England in 1877. Alexander became a distinguished and very innovative philosopher with an interest in psychology. Eliza Orme’s first surviving letter to him was written in 1886 while he was still in Oxford. He moved in 1893 from a fellowship there to a professorial post in Manchester; and in 1902 his widowed mother, an aunt, his two brothers and one sister, all came from Australia to join him. Ten years younger than Eliza, Alexander was very good-looking (‘tall, unusually handsome, of charming personality, yet reserved and thoughtful’) and his politics were feminist as well as liberal and Zionist. All this information and more is available on the University of Manchester website, which is where I first tracked down Eliza’s ‘dear Sam’ letters and finally heard her amiably intimate private voice so many years after first encountering her briskly practical public persona.

Fig. 6 Samuel Alexander (1932, Francis Dodd), ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Sam knew Eliza’s mother well enough to send her a Christmas letter, and he knew her sister Beatrice too. She had met his mother and siblings and some of his friends in Oxford. They also had mutual acquaintances in London such as the portraitist Edwin Longsden Long. Eliza helped a bit with Alexander’s first book, Moral Order and Progress, and when it came out in 1889 she was jubilant (‘You have made the book so valuable by writing in it that I have to buy another copy to lend’) and duly read and critiqued all the reviews. She thought Leslie Stephen’s was ‘the nicest of all’.

Eliza often gave Sam intelligent practical advice: in that first 1886 letter it was about how to handle his relationship with someone caught up in a nasty scandal. (She does not identify him by name, but it was almost certainly Charles Dilke as I explain in Chapter 8.) In 1892 when Sam was making his will she understood his wishes with respect to various family members, and used her professional knowledge to advise as to the best way to have them realized. In 1895 the problem was insurance. In 1902, when the family arrived in England, she counselled him on the best way to organize the domestic arrangements so that he would be able to get his work done and still keep everyone happy. Sam gave Eliza advice too, but she did not always take it. Late in December 1887, she wrote: ‘I am going in for that everlasting exam next Monday. Reina told me you thought it very wrong of me to do it but I dislike being beaten in such a matter and why should I not luxuriate in my own obstinacy if it hurts no-one? My people here know nothing of it so they are not anxious’. This was presumably the second (and final) LL.B. exam, which she passed triumphantly a few weeks later, but may have tried and failed the previous year. It is a little disconcerting to think that neither Sam nor ‘my people here’ (presumably the family at home) supported her writing the exam, but we must remember that no woman had ever passed it before–and that other careers than law were open to Eliza Orme.

She also knew Sam well enough to tease him about his growing reputation and even his marital eligibility, assuring him that he need not have financial worries: ‘You will accept a richly endowed (not widow tho’ I know you think that word is coming) but American chair and out of your ₤1500 per annum you will pay a biennial visit to London and be pitchforked into the Athenaeum and wear extremely fashionable clothes (but of an Academic style) and become a mugwump’. In a mark of intimacy in a different register, she reported to him on her illnesses—a quarantine for measles, a case of influenza, and (in 1916 when she was 67) being ‘locked up in a sick room’ in a ‘stupid woolly condition’.

There is evidence for the genuine friendships that existed among Eliza Orme, Sam Alexander, and Reina Lawrence, an intimacy that extended to members of all three friends’ families. That evidence takes the form of Eliza’s letters to Sam and her choice of Reina as executor, along with a few fragments from other sources. But it is certain that Eliza Orme had other close friends apart from the Lawrence and Alexander families. If letters from Mary Richardson had survived, or from someone in the ‘other family’ at Buxton, they would have shown just as warm and supportive a relationship as those with Sam Alexander. One close connection that she mentions in a letter to Sam is with the Liberal journalist and politician Auberon Herbert: ‘The most unreasonable, fascinating, absent-minded, amusing idler that ever bore the name of Herbert. Look him up and be amused’, she advised her friend. I have looked him up, in an internet search combining their names, and discovered only that Herbert was honoured alongside Charles Dilke at the republican political meeting in 1872 attended by Eliza and her friend Mathilde Blind. If they were still in touch sixteen years later and on such friendly terms, I might have hoped to learn more, but no further information has appeared. Nor have I been able to find anything substantial about the connection with Mathilde Blind.

She apparently knew Richard Garnett, a scholar-librarian at the British Library, well enough for him to send her an article about economics, knowing that she would share his sophisticated disdain for the author and the views expressed. Eliza thanked him in friendly, familiar terms, telling Garnett the piece had ‘afforded me much amusement’. She added a joke about the author’s foolish exercise of ‘popular logic’: ‘We are not to explain the Law of Supply & Demand because the phenomenon is as old as the Hills: ergo we are not to analyse air because Adam had lungs’. Their exchange happened in May 1873, around the time that she was starting to study with Savill Vaizey. I have searched in vain for further evidence of the Orme-Garnett connection and found nothing. As with the Alexander letters, it is only because Garnett’s papers are preserved at the Harry Ransom Center in Texas that I got to know of their relationship.

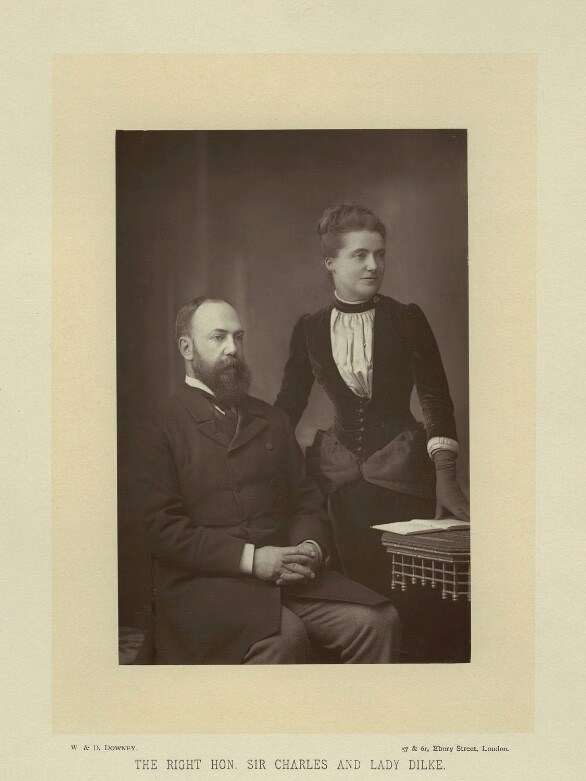

Another friendship that can be documented with certainty is with Charles and Emilia Dilke, a Liberal politician and the remarkable woman who was his second wife. Eliza was braving a snowstorm when she went to St James’s Hall with her friend Mathilde Blind to hear Sir Charles Dilke honoured at a huge political meeting as early as 1872. At that time he was already a Liberal Member of Parliament, a supporter of women’s suffrage and other radical causes, whose name was mentioned as a future prime minister. Dilke’s political leadership opportunities were blighted when he became involved in a very messy divorce scandal in 1885. (He had an affair with his brother’s mother-in-law, and was accused of seducing a woman called Virginia Crawford who was a member of the lover’s family; Dilke’s court case went disastrously wrong and his reputation was badly damaged). That first letter from Eliza Orme to Samuel Alexander is almost certainly a reply to one from him, seeking advice about the Dilke case, although no names are mentioned. In the letter, she passionately asserts the politician’s innocence and refers to her own ‘strong personal liking’ for the man, mentioning that she had ‘been much concerned’ in the case. The extent of Orme’s ‘concern’, and what it means, will show up in Chapter 8. Meanwhile, you can read more about the scandal in Kali Israel’s excellent book and article on the subject. Dilke’s political career did recover enough for him to return to politics but not to become Prime Minister as some had hoped. In 1892 he ran as a Liberal candidate in the Forest of Dean constituency, and Eliza Orme was among his campaign workers.

Fig. 7 Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, 2nd Bt. and Emilia Francis (née Strong), Lady Dilke (1894, W. & D. Downey, published by Cassell & Co. Ltd.), ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Emilia Dilke’s interests embraced the unlikely combination of trade unionism and art history. Among other occupations, she became leader of the Women’s Trade Union League. Lady Dilke had a regular column in the Women’s Gazette and Weekly News. In the case of the Dilkes, there is evidence of shared political and intellectual interests and of Eliza Orme’s fierce loyalty in the face of scandal; there is also my suspicion (see Chapter 5) that Charles Dilke was a silent partner in the ownership of Orme’s journalism project, the Women’s Gazette. All of that is compelling, but the fact remains that I have found no evidence of the three friends writing to one another, and hence no evidence of the warmth (or otherwise) of their relationships.

Then there are people whose lives touched hers, who may or may not have been friends. One of these was Manomohan Ghose, who was the first practicing barrister of Indian origin. It may have been friendship that motivated her to edit a book in which he figured, or their relationship might have been more collegial, or even businesslike. Ghose was older than Orme, studying law at University College in the 1860s, so they were not fellow students though both were active in women’s rights and other progressive circles before he went back to India. He did return to England briefly in 1885, so perhaps they encountered or reconnected with each other on that occasion; certainly they met in 1896 when she attended a public debate he was involved in. The book she edited, The Trial of Shama Charan Pal: An Illustration of Village Life in Bengal, featured a court case in which Ghose was the defending barrister. The book was published by Lawrence and Bullen in 1897, so it is also possible that the link with him was via the Lawrences. Whatever the motivation, the book is typical of Orme’s energetic, practical approach to challenges, whether they related to career, domestic arrangements, or political life. The relationship, however, remains opaque.

The same goes for her ten-year friendship, if that is what it was, with George Gissing, one that extended for a further decade of contact with his estranged second wife and children. Although this relationship is quite well-documented, the surviving evidence comes from the perspective of the novelist, and he tended to be rather complacent about the practical and imaginative aid he received from that quarter. Gissing was the same age as Beatrice Orme, born in 1857. As a young man, his promising intellectual career had been cut short when he was imprisoned—and expelled from college—for stealing money with the objective of helping a troubled young woman with whom he was involved. (Nell Harrison was a working-class woman who had been engaged in sex work.) Their eventual marriage left him stuck in the lower middle class with a chip on his shoulder, a condition that he turned to brilliant use in the plots and characterization of his novels. By the time Gissing met Orme in 1894 he had married his second wife and they had a son. (Edith Underwood, too, was from the working classes and seems to have experienced some mental health challenges.) His novel The Odd Women had been out for about a year at this point. Gissing mentions in his diary that he has promised his publisher Henry Walton Lawrence of Lawrence and Bullen ‘to dine with him and Bullen to meet Miss Orme shortly’, but he gives no reason why this promise has been extracted or offered. The invitation duly arrived and Gissing acquired a dress suit, though he later realized he had not needed it. They dined at the Adelphi Restaurant and later went to the publishers’ Henrietta Street offices to smoke and talk, ‘Miss Orme taking a cigar as a matter of course’. At this point Orme was well-known in London, as the Senior Lady Assistant Commissioner on the recently completed Royal Commission investigation of labour conditions, but if Gissing knew that he was not impressed enough to mention it in his diary or in any of the surviving letters to friends. Around the same time Gissing was also building a friendship with one of Orme’s colleagues on the Commission, Clara Collet.

Fig. 8 George Robert Gissing (1897, William Rothenstein), ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Gissing must have stayed in touch with Orme because he turned for both practical and emotional support to both her and Collet when his marriage began to break down in 1897. By this time there was a second baby. Edith Gissing’s side of the story remains undocumented, whereas the eloquent author wrote bitterly of her unacceptable behaviour and of his own unhappiness, both in a diary and in letters to friends. Most of his biographers seem to take Gissing’s judgement of Edith at face value, but it is worth noting that Orme and Collet saw both sides of the dispute, at least initially. Perhaps they regarded Edith’s outbursts as consistent with the extravagant rhetoric of the working-class women they had encountered in their labour investigations, rather than the evidence of insanity perceived by George Gissing. They both helped Gissing to manage his familial and legal obligations. (‘What toil and misery she is taking off my hands’, he wrote of Orme.) In September he agreed to pay Orme the considerable sum of ₤50 a quarter to care for Edith and the baby, Alfred, as lodgers in the home she shared with Beatrice and Charles Edward. Initially both she and Collet hoped to reconcile the couple, but by February of 1898, Orme found somewhere else for the mother and son to live, advised Gissing to seek a legal separation, and recommended her own solicitor. She found lodgings nearby for Edith and Alfred with ‘a decent working-class woman who could let part of her house unfurnished’. Gissing recorded in August 1898 that Edith had ‘written an insulting and threatening postcard’ to Miss Orme, addressed ‘Bad Eliza Orme’. Perhaps Edith felt betrayed.

Certainly there is a lot we do not know about all these relationships. The relentless scholarship of Gissing scholars like Michael Collie and Pierre Coustillas extends to peripheral people in the novelist’s life, people like Orme and Collet, but only insofar as they fit into the scholar’s analysis of the novelist’s family situation. In the case of Coustillas, in particular, this analysis followed Gissing’s own and was unsympathetic to Edith’s perspective. Later, after Edith had been arrested and subsequently confined to a mental-health institution, Orme called upon her sister Blanche Fox to find a farming family in Cornwall who took care of Alfred; this cost Gissing a mere ₤19 per year.

When I wrote about Eliza Orme’s career in terms of its precarity, for the 2021 essay collection Precarious Professionals, I speculated that the task of housing, feeding, and supervising Edith and Alfred Gissing might have been a paid gig—perhaps a welcome supplement to her income after the Royal Commission and the committee on prison conditions had ceased to provide any revenue. I realize there was more to the relationship between Orme and Gissing than a cash transaction, but I also believe the association was more complicated than Coustillas and other Gissing scholars have allowed. Knowing Orme as I now do, it seems obvious there was more to it than her endless kindness and sympathy for the genius of the tortured novelist. A tiny example: Coustillas has trouble understanding why Gissing might have received an invitation from the editor of the Weekly Dispatch, who contacted him in 1897 about an authorship opportunity. W. A. Hunter was editor of this newspaper for only five years; mostly he appears in reference works as a Liberal politician and law professor. As with Orme, Hunter’s journalism work is less well known. The editor said he heard of Gissing through Mrs Ashton Dilke (a women’s rights activist and his former student, the sister-in-law of Charles Dilke), but he may well have been concealing a closer connection: Eliza Orme wrote anonymous editorial essays (leaders) for the newspaper and she had known Hunter since her student days at University College. My guess is that she was either discreetly extending some practical help to Gissing as someone who needed a little cash, or else she was offering her editor a contact with a proven writer. Maybe even both. I wonder what she thought about Gissing’s refusal to take up the offer, and his expressed concern that his artistic output would be ‘tainted’ by juxtaposition with the trashy sort of popular fiction that appeared in the Weekly Dispatch?

As with the Dilke couple, there is no way to recover the texture of the relationships between the two estranged Gissing spouses and Eliza Orme. To use that fraught term, there was a certain ‘intimacy’ to both friendships, because she knew things about both couples that were private. As well, the boundary between ‘friend’ and ‘legal advisor’ in both relationships may have got blurred when tensions were high. I wonder how she addressed George and Edith, or Charles and Emilia, in face-to-face conversation—and how she talked to Beatrice about them when the two sisters were alone?

With other acquaintances, there is often insufficient evidence even to speculate on the level of familiarity. Orme worked closely with Sophia Fry, Sophia Byles, Alice Westlake and others in the Women’s Liberal Federation, but it is difficult to know which of those people were friends and which merely colleagues. Sophia Bryant, however, does seem to have been a real friend. Bryant was always identified by her science degree (D.Sc.) in women’s suffrage and Liberal publications, just as Orme was by her law degree. Bryant was from an Anglo-Irish family, and (like Eliza Orme) trained as a mathematician. She had been widowed at the age of twenty and used that independent social position to study mathematics and then make a name for herself both in her profession and in the Women’s Liberal Federation and other feminist causes. But as with the Dilkes and so many others, the tone of the friendship is out of reach to us today.

Playing to the Gallery

It seems to me that the relationship of mentor and protégée was important to Eliza Orme, as was the collegial closeness that can develop between people working together on the same project or cause. In my own life I have benefitted immensely from being mentored by senior scholars, while becoming a mentor in my turn has been equally rewarding. Some of those relationships have turned into friendships, while others have faded a bit when we no longer see each other at academic gatherings. There is almost always a dynamic of unequal power in the relationship between two people who started out as mentor and protégé, though that dynamic does not always get acknowledged.

One protégée from early in Orme’s career was Hertha Marks (better known in later life as the engineer/mathematician Hertha Ayrton). In one of her letters to Helen Taylor, in November 1875, Eliza mentioned that she had heard that Taylor ‘would like to help a clever girl study at Girton’. The one she had in mind was about twenty, daughter of a Jewish widow in poor circumstances and encumbered with a younger sister. Orme herself had taught mathematics to Miss Marks, and the powerful women’s movement leader Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon was also interested in her case. Taylor did as she was asked, and Orme duly acknowledged a cheque for ₤25. I hope that, in helping Hertha Marks, Eliza understood how someone who lacked her own economic and familial privileges must be having a much more difficult time than she herself had experienced.

Later in life, just before her stint on the Royal Commission on Labour, Orme mentored Alice Ravenhill (1859–1954), later one of the first women to do public health inspection work, advising Ravenhill that ‘There is such a thing as legitimate “playing to the gallery’’’. In other words, it was a good idea to perform one’s competence for the benefit of a powerful audience, and a bad idea to hide one’s light under the proverbial bushel. She added that ‘one should never lose an opportunity to see, hear, or if possible, secure contact—however momentary—with persons of note’. Finally, she recommended, a young woman with Ravenhill’s kind of ambitions ought always to ‘apply to the fountainhead for information’—that is, go directly to whoever held authority in a given situation. There is plenty of evidence that Eliza took her own advice as she built her own career, but it is delightful to know exactly how she articulated it for someone else.

Alice Ravenhill moved to Canada after establishing herself in England as a practitioner of home economics. In British Columbia she supported and advocated for Indigenous arts and crafts among other interests. Ravenhill’s memories of Orme’s advice turn up in her autobiographical writings. In addition to those published memoirs, a great many of Ravenhill’s letters have been preserved in the British Columbia Archives, the University of British Columbia Library, and in Library and Archives Canada. These two women lived parallel lives in some ways (Ravenhill was born eleven years after Orme and she lived to be ninety-five), but the difference was that one’s papers were mostly lost while the other’s were, mostly, preserved for research.

Many of Orme’s own mentors were male, the professors like Hunter and others who had taught her in university, the barristers like Phipson Beale who helped her get a foothold in Chancery Lane, and the politicians like John Stuart Mill whose aloof encouragement shaped some key moments of her career. Presumably she ‘played to the gallery’ with some of them, first in classrooms and then in the chambers of the Inns of Court, at Liberal Party gatherings, or in private meetings. In her appeal to Helen Taylor, she can be seen ‘applying to the fountainhead for information’, seeking moral as well as financial support and (perhaps) useful introductions. That was a complicated relationship, in that Taylor controlled Orme’s access to Mill. In any case, it is pretty clear that relationship did not develop into a friendship; in fact it seems to have devolved into antagonism.

All of these people—parents, siblings, nephews and nieces, friends, lovers(?), acquaintances, protégées, colleagues—drifted in and out of Eliza’s life over the decades of her education, political work, and quasi-professional career. As we will see, her public prominence peaked in the early 1890s when she was in her mid-forties but continued for another decade. The deaths of both her parents in 1893 may have precipitated a rethinking of priorities and possibilities. Charles Orme’s will left everything to be divided among his three unmarried children, but Eliza was made executor of the estate. The three siblings moved from the Chiswick house to the new one (possibly newly built) in Tulse Hill not long after.

Who, then, was the private Eliza Orme? And whose was she—whose friend, colleague, antagonist, lover, lawyer, sister? Whose aunt or niece, editor or mentor? With all the sensational tidbits on Eliza Orme’s private life that have surfaced for me recently, it has been more and more tempting to believe I know enough to reconstruct her life on the page, with authority and certainty. But I remain absolutely certain that I cannot, that much more information remains unrecovered, some lost forever and some waiting for the right questions to be asked, the right archives consulted. With respect to the question of her sexuality, for example, and remembering the need for discretion on the part of women in public life, it is possible that Eliza’s relationship with Reina was strictly one of business and family friendship. Or that there was another woman, or perhaps a man, whose role in her life I will never know. I would not, after all, know about her and Sam Alexander if he had not happened to be a distinguished philosopher whose personal papers were preserved, organized, and documented by the university to which he devoted his career. But she and Sam were chums, more like cousins with a ten-year age gap to enhance the gender difference. Eliza and Reina were chums, too—girlfriends who also worked together on political campaigns and in their Chancery Lane chambers when they were not organizing parties where iced lemonade and bananas were served. Each of them had a life and a reputation in the public eye, but their correspondence, even if such letters ever survived the accidents of time, was not likely to receive the same archival attention as that of Alexander or of Gissing. Not only that: both Eliza and Reina had a lot more to lose than did their male contemporaries. When scandal touched the life of the radical politician Charles Dilke, his career eventually recovered, whereas theirs would have been irretrievably damaged. In any case, I suppose both women believed that posterity had no business delving into their privacy.

Public life, however, was another matter. Like other extraordinary women of her time, Orme saw her achievements recorded as news items. She had the opportunity to express her views in published opinion pieces. And her adversaries were eager to record their opposition to her actions.