15. Indigenous leadership is essential to conservation: Examples from coastal British Columbia

Andrea J. Reid1 and Natalie C. Ban

©2025 Andrea J. Reid & Natalie C. Ban, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0395.15

Positionality statement and preface

Dr. Andrea Reid is a Nisg̱a’a fisheries scientist and Dr. Natalie Ban is a Canadian settler marine conservation scientist. Dr. Andrea Reid carries a responsibility to hold place for Indigenous voices in the academe, especially within the natural sciences, where often no space is held, and she is supported and upheld in this work by colleague and ally, Dr. Natalie Ban. Together, we welcome readers to this space created to highlight the importance of Indigenous leadership in conservation for the benefit of all—people, place, and non-human relatives—today and in the future.

The topics covered throughout this chapter reflect the experiences gained by us through our respective research programs that are carried out in full and equal partnership with Indigenous Peoples in the place now known as British Columbia (BC), Canada. Given the uniqueness of Indigenous Nations in BC, Canada, and around the world, the commonalities and distinctions drawn here will not necessarily be relevant or reflective of the reality of all Indigenous Nations.

Territorial statement

This chapter was prepared from the territories of the Anishinaabeg [Ottawa], xwməθkwəy'əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlil'ilw'ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) [Vancouver], as well as the Lək'wəŋən (Lekwungen)-speaking Peoples, namely the Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ [Victoria]. We work to be respectful guests while visitors on these lands and waters and are committed to working in a good way with local Indigenous governments, communities, organizations, and individuals. Ultimately, it is our hope that we can work together towards building space for multiple ways of knowing in institutes of higher education that have long histories of Indigenous exclusion and injustice that fundamentally need to be recognized and redressed.

Indigenous-led conservation

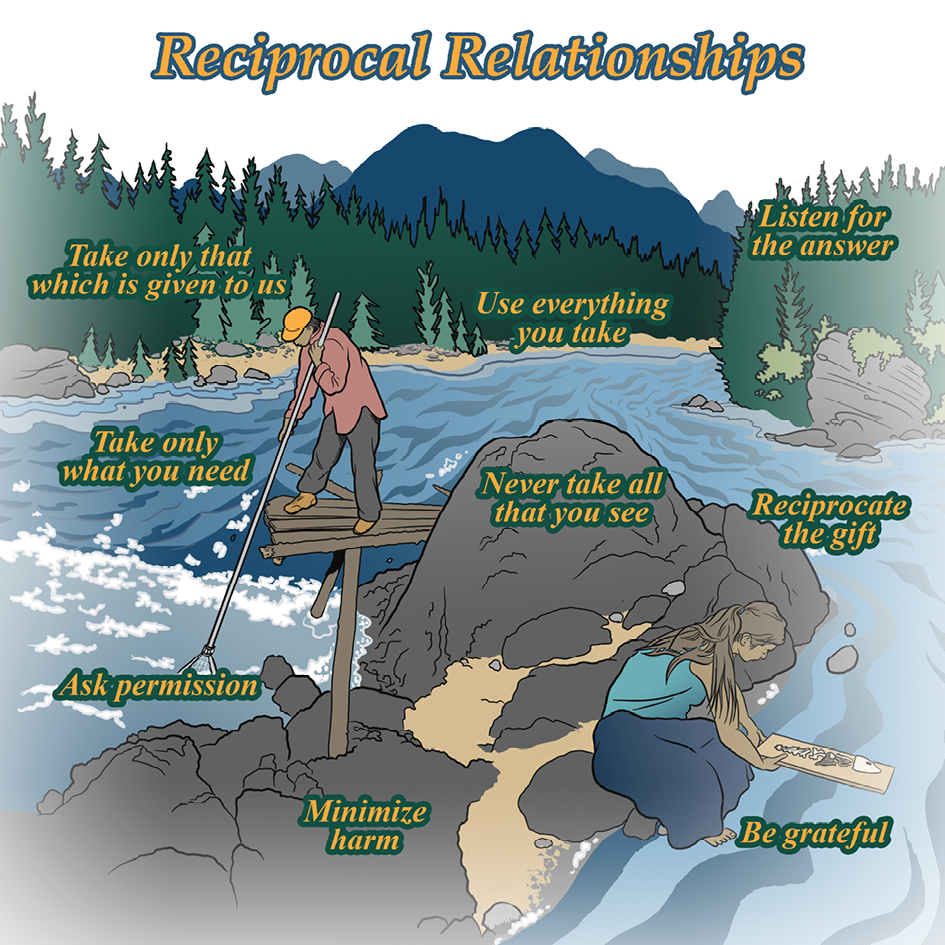

The need for and value of Indigenous-led conservation is being increasingly recognized by the academic community and public alike. This is apparent across Canada and around the world where policymakers and various actors in dominant society have failed to control human activities driving climate change and habitat loss, while Indigenous lands and waters have been successfully stewarded and managed over millennia. In Canada, Brazil, and Australia, for instance, vertebrate biodiversity in Indigenous territories has been shown to equal or surpass that found within formally protected areas (Schuster et al., 2019). Far from the colonial idea of separating people from nature in order to preserve nature and the concept of the “pristine primitive” or “wilderness” free from human influence (Anderson et al., 2008), Indigenous approaches to conservation regularly place reciprocal people–place relationships (Figure 15.1) at the center of cultural and stewardship practices (Kimmerer, 2013). As such, Indigenous approaches to conservation ought to be centered in discussions around integrating science and governance.

Fig. 15.1 Reciprocal relationships between Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest and Pacific salmon are linked to entire fishing ethics as depicted here that embody respect, reverence, responsibility and reciprocity. The practices highlighted here stem from Kimmerer’s33 conceptualizations of the “honorable harvest” in the realm of harvesting plants and medicines—all of which were found to exist in parallel in salmon-centered studies undertaken and described in Reid. These ideas were illustrated by Nicole Marie Burton.

Indigenous-led conservation supports and embraces Indigenous knowledge systems, sovereignty, and governance structures. The return to this mode of conserving flora and fauna can help countries meet their responsibilities to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, 2007) and respond to national calls to action such as those prescribed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Government of Canada, 2015) or agreements reached to govern Crown-Indigenous relations (e.g., pre-Canadian Confederation: Peace and Friendship Treaties, 1725–1779; post-Canadian Confederation: Canada’s Numbered Treaties, 1971–1921). In 2019, British Columbia (BC) became the first province in Canada to create legislation setting out a process to align provincial law with UNDRIP (SBC, 2019), creating the potential to transform what has historically been a relationship of tension and conflict to one possibly characterized by collaboration, respect, and real partnership. At this current time of political and racial awakening (e.g., Black Lives Matter, Land/Water/Fish Back), there is perhaps greater societal and institutional will to cultivate a more socially just reality for all people—ultimately creating space for Indigenous societies, values, and knowledge systems to govern (as they once did) lands and waters within their traditional territories.

A reckoning for conservation science

Over the last two decades, there has been a reckoning in conservation science that social sciences are vital to ensuring the uptake and efficacy of conservation measures (e.g., Bennett et al., 2017; Moon and Blackman, 2014; Pressey and Bottrill, 2009), and that conservation science needs to embrace socio-ecological systems thinking to meet the needs of both the environment and society at large (e.g., Ban et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2012). The interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary endeavor of conservation science started as a normative field seeking to protect biodiversity. Initially, conservation science focused on ecological and biological studies about species and their habitats to identify places and actions that recover and ensure persistence of biodiversity (Margules and Pressey, 2000; Soule, 1985). Since the formation of conservation science (initially termed ‘conservation biology’) in the 1980s, there has been an increasing realization that social science methodologies and insights are essential to achieving successful conservation (e.g., Jacobson and McDuff, 1998), and that the effects of conservation on people matter (e.g., Ban et al., 2019).

We believe conservation science is at the cusp of another reckoning: that socio-ecological approaches and methodologies are insufficient, and that embracing multiple ways of knowing—especially Indigenous ways of knowing—is essential if humanity is to protect biodiversity, and respect and uplift human rights. To date, conservation science has been guided by dominant approaches to academic (or “Western”) science (Redford and Richter, 1999; Robinson, 2006; Soule, 1985). Recognizing the value of Indigenous knowledges2 in conservation is not new (Gadgil et al., 1993). Indeed, there is a growing body of literature based on the importance of traditional ecological knowledge for conservation (e.g., Berkes, 2004; Drew, 2005; Moller et al., 2004). However, many conservation case studies to date have focused on utilitarian aspects of Indigenous knowledge systems by considering traditional ecological knowledge as a source of data to be incorporated into Western framings of conservation (Nadasdy, 2005), or by appropriating aspects of Indigenous cultures into conservation (e.g., taboos, Osterhoudt, 2018). Such approaches contribute to disempowering Indigenous Peoples by extracting their knowledge for external purposes (Thompson et al., 2020), and continue colonial legacies (Tran et al., 2020). Instead, we need conservation science that supports, uplifts, and respects Indigenous rights, stewardship, and knowledges, and thereby expands conservation beyond our current Western scientific approaches.

In this chapter, we draw upon our experiences in the place now known as BC, Canada, to showcase examples of Indigenous conservation and science. We emphasize historical and contemporary conservation leadership by Indigenous Peoples, highlight the history of active suppression of such practices by colonizers, and provide some guidance on how non-Indigenous scholars can be allies to Indigenous leadership in conservation.

Understanding Indigenous science and stewardship

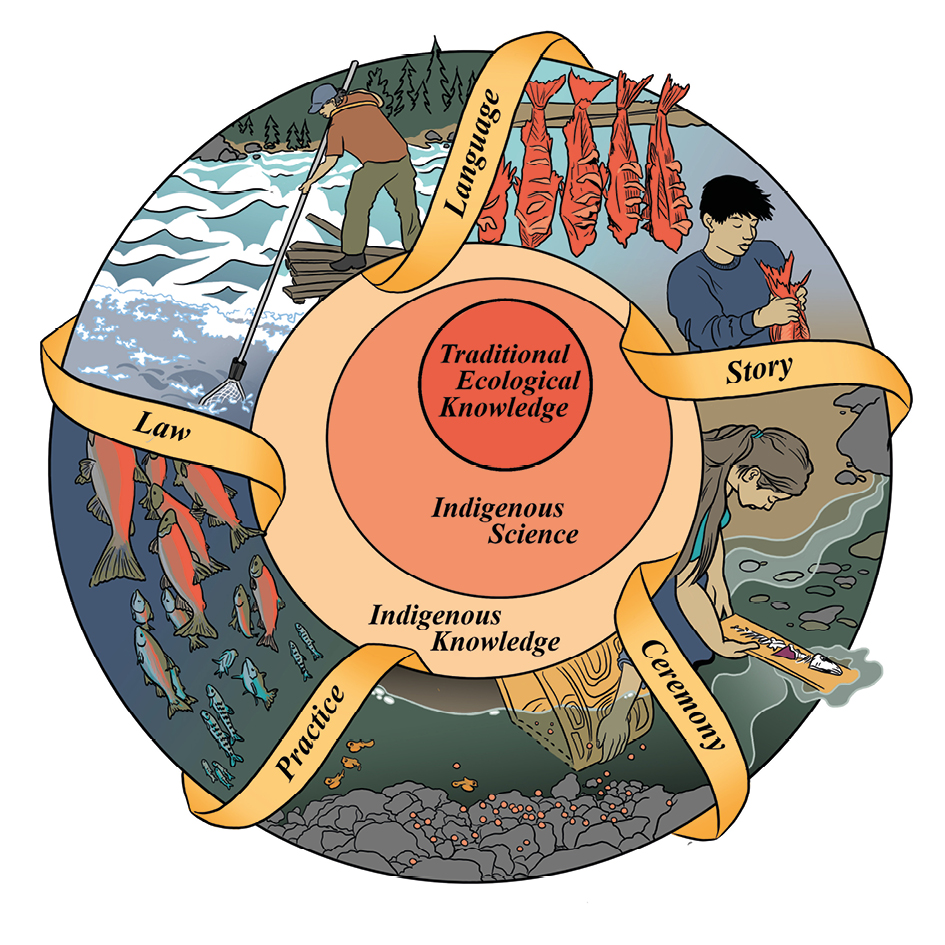

Along with the reckoning of conservation science to recognize multiple ways of knowing comes the need to understand Indigenous science. While Indigenous science was only defined as a term in the literature in recent decades, coined by Colorado (1988), its existence is long-standing. It is generally accepted now as the scientific knowledge (see below) of “all peoples who, as participants in culture, are affected by the worldview and interests of their home community” (Snively and Corsiglia, 2016). According to the Worldwide Indigenous Science Network (wisn.org), Indigenous science “is a way of perceiving the world that is holistic, participatory, and in balance with the Earth’s life support systems.” While scientific knowledge is understood as deriving from a “systematic enterprise that gathers and condenses knowledge into testable laws and principles” (Wilson, 1999), the term ‘science’ is most often used only in reference to that which has roots in the philosophies of Ancient Greece and the Renaissance, favouring reductionism and physical law (i.e., Western science). We believe conservation would improve by embracing systematic enterprises of gathering and condensing knowledge that stem from other worldviews and ways of knowing and being.

Fig. 15.2 Interrelationships between traditional ecological knowledge, Indigenous science, and Indigenous knowledge are depicted here using the symbology of the life cycle of Pacific salmon, starting with the salmon egg at the core of the image. The understandings and philosophies embedded in this center are carried through time––across generations––through language, story, ceremony, practice and law. Salmon and Salmon People not only co-exist in these settings but are interdependent with one another. These ideas were illustrated by Nicole Marie Burton.

In many cases across distinct Indigenous cultures, Indigenous science is holistic and inherently transdisciplinary (Berkes, 2017). It is contained within a much larger body of philosophies and understandings—Indigenous knowledge—and may pertain to, but is not limited to, human relationships with the environment (Figure 15.2). Languages and stories are the vessels that transmit these understandings through time and space, and they are carried across generations through ceremonies and practices that are guided and protected by laws. Another common feature is that so-called nature, which is not viewed in isolation or as separable from people, is understood as being alive, intelligent, and possessing inherent rights (Kimmerer, 2013) to which humans bear a great responsibility (pers. comm., Mi’kmaw Elder Dr. Albert Marshall). This is reflected, as one example, in the legal rights of personhood bestowed in 2017 on the Whanganui River in Aotearoa/New Zealand to align with Māori rights and cosmology (Magallanes, 2015). The non-human (or what many term the ‘more-than-human’) are positioned as relatives or gifts, depending on the context and culture, rather than as commodities or machinery subject to human control (Kimmerer, 2013). Indigenous science therefore stems from a vastly different foundation than Western science, which culminates in distinct approaches to understanding, interacting with and stewarding the natural world.

Indigenous stewardship practices are often steeped in highly reciprocal relationships, as noted above, in which, for example, it is not solely humans that need fish or land, but fish and land also need people—not only as harvesters or users, but as caretakers and stewards (e.g., Land Needs Guardians initiative; https://landneedsguardians.ca/). According to this view, humans are not strictly perceived as a destructive or consumptive force, but as beings with constructive or productive powers (Kimmerer, 2013). For Indigenous Peoples in coastal BC, determining who has access as well as responsibility to a specific place was—and remains so in certain areas—linked to the clan system and specific house groups. In these systems, chiefs and matriarchs provide(d) oversight over such matters, often in the context of house feasts or potlatches (gift-giving feasts, a crucial governance mechanism for coastal First Nations in the Pacific region) which were banned in Canada from 1885 to 1951 as part of national cultural assimilation processes (Cole and Chaikin, 1990). The potlatching system creates community accountability as well as serving as a “monitoring device” wherein the sustainability of harvest and stewardship practices are subject to repeated assessments by those who potlatch together (Weinstein, 1999).

Coastal Indigenous stewardship

Indigenous leadership has fostered successful marine stewardship and management in the past and at present through a multitude of strategies that play out differently across the world. Indeed, coastal Indigenous Peoples have been managing oceans and coastal regions for thousands of years (McKechnie, 2007; Turner and Berkes, 2006). Indigenous marine and coastal conservation, stewardship, and management practices (hereafter ‘Indigenous marine conservation’) vary globally to support local ecosystems, customs, and ongoing use (Ban and Frid, 2018; Berkes, 2017; Lepofsky and Caldwell, 2013). Some Indigenous marine conservation strategies are similar across diverse cultures, including customary tenure areas where rights of use, management, and access to the ocean belong to specific people or entities as discussed above; e.g., a village, chief, or family (Jupiter et al., 2014). Some Indigenous marine conservation approaches are increasingly well-recognized, whereas others are little known or misunderstood by Western science. Indeed, in some parts of the world—especially Oceania—Indigenous marine governance systems have been embraced, revitalized, and are forming the basis of contemporary ocean management (Johannes, 2002; Jupiter et al., 2014). In particular, customary marine tenure, often in the form of locally managed marine areas, are common forms of management of marine species and spaces (Cinner, 2005; Cinner et al., 2007; Lam, 1998; Winter et al., 2018). In other regions, especially where colonial forces actively undermine(d) Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous governance revitalization efforts are underway but recognition by colonial governments is slow (Ban and Frid, 2018; Bess, 2001; Eckert et al., 2018; Nursery-Bray and Jacobson, 2014; Nursery-Bray and Rist, 2009). Here we provide two examples of Indigenous marine and coastal stewardship by Indigenous Nations with whom we have partnered in our research: the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation, and the Nisg̱a’a Nation (Figure 15.3).

Fig. 15.3 Map of the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia (BC), Canada, specifying the approximate contemporary location of villages of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais (Klemtu) and the Nisg̱a’a Nations (Gingolx, Laxgalts’ap, Gitwinksihlkw and Gitlaxt’aamiks). Map illustrated by Nicole Marie Burton.

Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation marine governance3

Kitasoo Xai’xais marine governance flows from the underlying principles of Kitasoo Xai’xais Law that guides all actions: respect, reciprocity, intergenerational knowledge, and interconnectedness. Everything—people, plants, animals, place—has the right to be respected in all forms, including physically and verbally. People have a responsibility to show gratitude and maintain reciprocity in relationships with the land, sea, natural environment, and other humans. This responsibility is commonly shown through territorial access and gift giving. Exchanges can be between people, animals, and supernatural beings. People should base decisions on learning from experience, including the experiences of past generations (Ban et al., 2019; Ban et al., 2020).

Exchanging intergenerational knowledge, especially through stories, is the main method to pass down past experiences, and thus language revitalization is very important. Storytelling often occurs on the land and water while harvesting and processing foods, allowing experiential learning to take place. Adaptive management is a scientific principle that ties in with the concept of ‘listening to your elders’. Indeed, it is the responsibility of community members and especially elders to teach younger generations their knowledge. Furthermore, the natural environment and its species, including humans, are all connected. This oneness means that one small change can affect everything else. Thus, everyone has a responsibility to ensure intergenerational and interspecies equity by using species (non-human relatives, gifts) as food sustainably. Kitasoo Xai’xais marine governance implements these underlying principles through societal structures and practices. The ocean is a key place where knowledge is passed through generations and teaching takes place (Ban et al., 2019). However, because the oral tradition is not documented in the way that Western science acknowledges, it can be challenging to recognize or cite this knowledge within the Western scientific paradigm.

Historically as well as today, Kitasoo Xai’xais Hereditary Chiefs are stewards for the land and ocean territory held under their chief name to ensure their areas remain plentiful and healthy (Ban et al., 2020). Historically, families and lineages dispersed to seasonal spring, summer, and fall camps to use species as food—or what might be called ‘resources’ in Western science—to which their lineage have rights or to which individual families have rights. Everyone using more-than-human-beings as food has an obligation to steward areas. Historically, the responsibility rested on the Hereditary Chiefs to ensure conservation of species by making decisions around harvesting—for example by observing how many salmon are returning to a stream—including telling families when fish can be harvested without overfishing. Conservation was also practiced through the right to exclude people and regulate access to the territory, both in the short term to allow recovery of species, and in the long term through agreements with neighboring Nations. Although inevitably impacted by colonization, aspects of these practices and responsibilities continue today. Ongoing use of species as food through time was and continues to be a way of maintaining and displaying rights to resource claims. In other words, harvesting throughout the territory is a way to take care of places, and enables stewardship actions through ongoing observations carried out while fishing. Selective harvesting is paramount; examples include harvesting species that are abundant, selecting for specific characteristics and sizes (e.g., using fish traps and weirs; throwing back female crabs and small crabs) (Ban et al., 2020).

Kitasoo Xai’xais Hereditary Chiefs continue to use their longstanding authority to stand against non-Kitasoo Xai’xais decisions imposed upon them. For example, in the 2010s, the Kitasoo Xai’xais created their own herring management plan (2019), distinct from the federal government’s plan, and Kitasoo Xai’xais members protested in an important bay in their territory (Kitasu Bay) against the commercial herring roe fishery, reacting to concerns about declines in herring populations and unsustainable contemporary fisheries management. After many years of protests, this has led to co-management of herring with Fisheries and Oceans Canada in their territory. Similarly, when Fisheries and Oceans Canada (formerly the Department of Fisheries and Oceans; DFO)—the Canadian fisheries agency—disclosed new fishing regulations in Kitasu Bay for community members, the Chiefs told the fisheries officer that they did not accept them, and they went out to protest. Hereditary Chiefs have the right and obligation to stand up and provide a voice for people, plants, animals, and places. By this act of self-determination, Hereditary Chiefs and community members practiced their authority with regard to harvesting decisions, despite the Canadian government not fully recognizing their authority (Ban et al., 2020).

Nisga’a Nation salmon stewardship

Another example of historic and contemporary Indigenous coastal fisheries stewardship involves the Nisg̱a’a Nation and the Nass salmon fishery in northern BC. Here, the Ḵ’alii Aksim Lisims (Nisg̱a’a for Nass River; used hereafter) sits at the very base of the Alaska Panhandle, where it flows from its headwaters, Mag̱oonhl Lisims (Nass Lake), for approximately 380km into Saxwhl Lisims (the mouth of the Nass) and then out into the Portland Inlet and Pacific Ocean. With a drainage area of >20,000km2 (Fissel et al., 2017), the Nass River is BC’s third largest salmon producer, supporting all five species of anadromous BC salmon—ya’a (Chinook; O. tshawytscha), k’a’it (chum; O. keta), eek (coho; O. kisutch), sdiḿoon (pink; O. gorbuscha), and miso’o (sockeye; O. nerka) (Connors et al., 2019; Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife 2019)—as well as milit (steelhead; O. mykiss) and saak (oolichan; Thaleichthys pacificus). Salmon are a key link between marine and coastal systems and epitomize how connected these systems are. Indeed, unlike the realities of Western governance, in many Indigenous worldviews—and indeed according to that of the Nisg̱a’a—the land, fresh water, and the sea are not seen as distinct, but rather as an interconnected and interdependent continuum. Conservation of coastal species such as salmon that provide a crucial link between systems is essential for healthy animals and people, plants, and places.

Through Ayuuḵhl Nisga’a (Nisg̱a’a Law) and Adaawaḵ (Nisg̱a’a oral histories, legends, and customs), the Nisg̱a’a way of life has been maintained for centuries, before European contact until today. Nisg̱a’a cosmology centers on harmony and balance between people and all of the other elements of the environment in which Nisg̱a’a live. Balance has been built into Nisg̱a’a life to provide for the wellbeing of whole families—the Nisg̱a’a way is said to be one of sharing within and among families, and of being closely related to the land (Dr. Joseph Arthur Gosnell, Sr. CC OBC, personal communication). As examples of this balance, and in line with the reciprocal salmon–people relationships described above (Figure 15.1), Nisg̱a’a fishing ethics often involve not playing with food (e.g., avoiding catch and release fishing), keeping what you catch (e.g., using selective fishing methods so there is no need for bycatch reduction strategies), only taking what you need and sharing what you have with family (Reid, 2020).

This system has provided for the ‘People of the Nass River’—the Nisg̱a’a—as well as neighboring Nations for millennia. The English name “Nass” likely derives from the neighboring Tlingit language, from their word “Naasí” meaning intestines or guts, in reference to the river’s large food capacity in its fish (Akrigg and Akrigg, 1997; Edwards, 2009). The Nass River served as a veritable food basket for many peoples and organisms pre-colonization (Scott, 2009), and it continues to do so today where it underpins a large commercial fishery (in Portland Inlet—Fisheries Management Area 3) and remains the lifeblood of Nisg̱a’a culture and commerce. In 2000, a landmark agreement between the governments of the Nisg̱a’a, BC, and Canada came into effect, creating BC’s first modern-day treaty (one of only four ratified treaties out of 200+ First Nations in the province), which involves a specific right to fish salmon. The Treaty sets out the Nisg̱a’a right to self-government (represented by the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government) and the authority to manage lands and species (represented by the Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department). Via the Joint Fisheries Management Committee, the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, BC, and Canada co-manage the Nass salmon fishery.

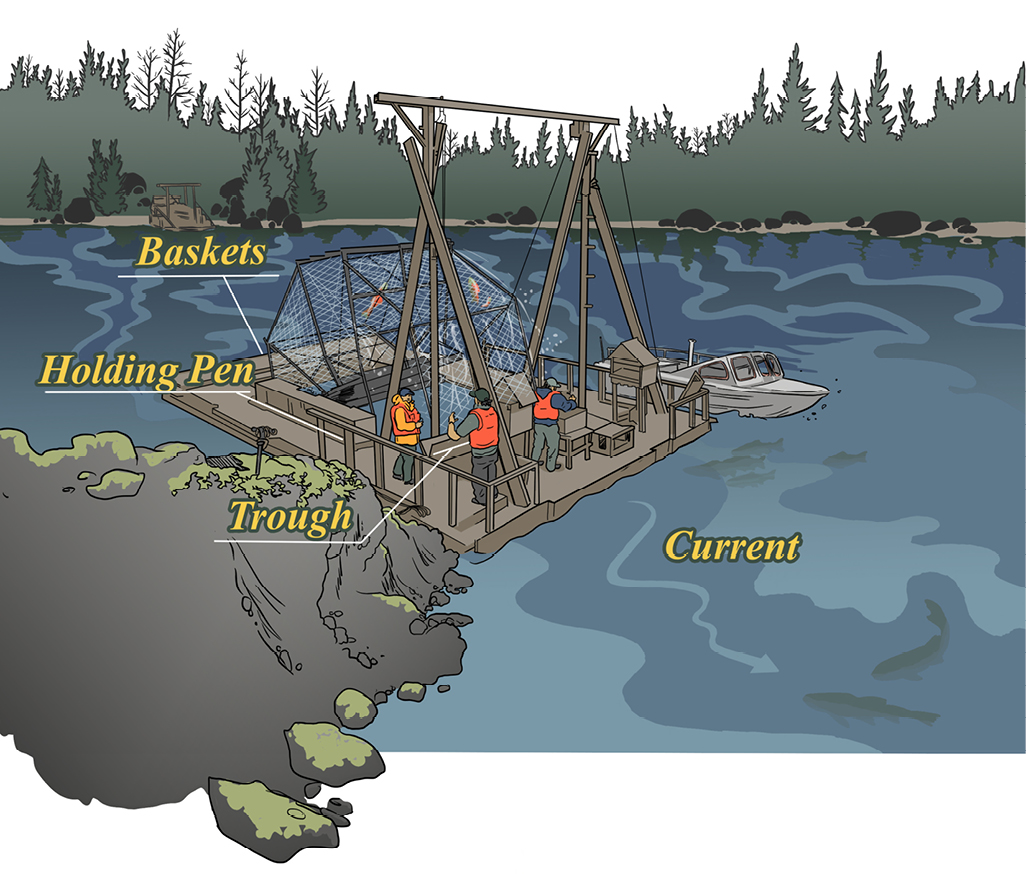

Fig. 15.4 A Nisg̱a’a fishwheel on the Nass River of BC. The current powers the rotational movement of baskets that gently catch and lift fish from the river and deposit them into submerged holding pens. Fish are held here until Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department biologists and technicians transfer them by dipnet into a flow-through trough where they can be tagged, measured, and released unharmed or retained for food. These ideas were illustrated by Nicole Marie Burton.

Together, they now co-manage a renowned fisheries science program that has been used for Nass salmon assessment and management for over three decades (est. 1991). The Nisg̱a’a Fisheries Management Program uses fishwheels (Figure 15.4) and other technologies on the Nass River to monitor, mark, and collect data from fish swimming upstream, facilitating stock assessments on a variety of species throughout the Nass watershed. Between 1992 and 2018, an average of 1.5 million salmon have returned to the Nass River each year, with sockeye, pink, and coho salmon dominating returns (43%, 39%, and 13%, respectively) (Nisg̱a’a Fisheries and Wildlife, 2019). The goals of the program, according to the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, are to: “(1) determine the status of Nass stocks; (2) provide information required for better management; (3) determine run size, timing, and harvest rates; (4) determine factors limiting production; (5) provide training and employment for Nisg̱a’a people” and it does so by “(6) collaborating with researchers from around the world” (Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, 2019). This management plan is guided by Nisg̱a’a knowledge systems and priorities, and hinges on deep respect for salmon and recognition that salmon and people are inter-reliant. Ayuuḵhl Nisga’a and Adaawaḵ detail Nisg̱a’a responsibilities to salmon, and describe what living in a good way in the Nass River Valley entails. The methods used to monitor salmon populations are thus positioned to minimize stress and harm to the fish, and endeavor to bring together the best tools available to improve collective understanding of salmon status and fate of the population (Reid, 2020). A lauded example is that of the fishwheel-based monitoring program, described as: “an ingenious fish-counting system in the Nass River that combines ancient Nisg̱a’a fishwheel technology with modern statistical methods of data analysis” (Corsiglia, and Snively, 1997). The Nisg̱a’a fishwheel program has enabled the continued monitoring of salmon escapement and harvest, the study of factors limiting salmon production, as well as the participation of Nisg̱a’a citizens in the active and continual stewardship of the Nass River (Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, 2019).

Suppression of Indigenous conservation

That Indigenous conservation continues—as exemplified above with the Kitasoo Xai’xais and Nisg̱a’a cases—is evidence of the strength of Indigenous Peoples and worldviews in the face of historical colonial atrocities, including genocide (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). While these are examples that can and should be celebrated, it is undeniable that past and ongoing European colonization of coastal regions has resulted in rapid and drastic changes in Indigenous management practices (including within Kitasoo Xai’xais and Nisg̱a’a Territories) because they were criminalized, dispossessed and/or restricted out of existence (Atlas et al., 2021). Indigenous Peoples were forcibly relocated, and the decline of many species due to commercialization contributed to reduced access to fish and a reduced ability to exercise self-determined management practices (Harris, 2002; Osterhoudt, 2018). In Canada, the Indian Act (enacted in 1876) and associated policies prohibited Indigenous cultural practices such as potlatches, banned Indigenous selective fishing methods such as fish traps and weirs (barriers across rivers that allowed for selective harvest of salmon) (Atlas et al., 2017), confined Indigenous Peoples inside reserves, and forcibly removed children from their families, cultures, and languages by sending them to residential schools (Harris, 2002; Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015). These past and ongoing policies severely diminished the wellbeing of entire Nations, disrupting Indigenous knowledges and management practices (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015).

Indigenous Peoples created many strategies to continue their traditions and keep practicing their cultures despite these genocidal policies. For example, an important celebration for the Kitasoo Xai’xais—like many coastal First Nations—is the annual return of the salmon. When potlatches were banned, Kitasoo Xai’xais still celebrated this important event, but concealed it under the Salmon Queen and, later, the May Queen celebrations (i.e., ostensibly celebrating the Queen of England). A pole was erected in the 1950s next to the May Queen stand in the center of the community with a salmon on top. People risked arrest to continue this important celebration (Ban et al., 2019). Potlatches across many Nations were not extinguished but instead driven underground, and the languages and bodies of practice—while purposefully diminished in strength by the oppressors—have not altogether disappeared in all contexts, but in many cases, they are waiting to be reawakened through Indigenous resurgence and reassertion of Indigenous rights.

Supporting Indigenous conservation

To transform conservation science into a science and practice that embraces multiple ways of knowing, conservation scientists and practitioners must support the original caretakers of lands, fresh waters, and seas. This is not a question of ‘allowing’ Indigenous peoples to manage, steward, and govern their territories (a paternalistic attitude that has characterized much related policy and practice to date), but rather it is a matter of creating space and stepping aside so Indigenous leaders can indeed lead. Various guidance exists for scientists to support Indigenous Peoples in conservation and related fields in a good way (e.g., Adams et al., 2014; Ban et al., 2018), and here we highlight some of that pertinent guidance.

Supporting Indigenous Peoples in conservation entails that non-Indigenous conservationists should be allies. As examples, two Canadian-based organizations have provided guidance on what it means to be an effective ally. The Montreal Indigenous Community Network developed an online Indigenous Ally Toolkit4 that includes three steps. First, be critical of any motivations, to ensure that engagement is not aimed simply at furthering one’s own self-interest (e.g., publishing a paper), but rather genuinely supports Indigenous Peoples and voices (i.e., does the work at hand originate from Indigenous needs and interests?). Second, start learning. This is an ongoing process of education that then includes applying the lessons in meaningful ways, for example, to ask if one’s privileged position can be used to listen, shift power dynamics, and further reconciliation. There must be efforts made to understand the impact of colonialism and to be willing to give up space and power so that it is available for others. Finally, act accordingly, including in communications with relevant Indigenous Peoples or organizations. We present these here, not as a panacea, but as an entry point for readers to begin to interrogate their own positionality and identify steps that lead to greater equitability in the research process and in the practice of conservation science.

Another ally toolkit, specifically aimed at supporting Indigenous-led conservation, was developed by the Indigenous Leadership Initiative5. It shares their hopes and expectations of how we—Indigenous and non-Indigenous people—can collaborate. Very briefly, the guidance includes: trust Indigenous leadership; create space for Indigenous voices; understand the connection between land and nationhood; recognize Indigenous science; participate with interest; focus on solutions; share stories with respect; continue to learn; and influence your peers. We cannot stress enough the importance of taking guidance from leaders in this space, and of advocating for transparent discussions with Indigenous partners in research and conservation science to learn what each of these specific recommendations look like in their individualized context (i.e., what is the connection to land here and what does it mean? What is the core problem and what would solutions look like?). A promising new toolkit was recently developed by the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation and research partners to provide an ‘open source’ and generalizable research guide to inform equitable applied research practices (available for download here: https://klemtu.com/research-guide/).

Important ethical guidance around data ownership and intellectual property also exists for research with Indigenous Peoples, which is especially important for conservation scientists conducting research in Indigenous territories and in partnership with Indigenous Peoples. In particular, the principles of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP® principles6) are a set of standards for how First Nations data should be collected, used, or shared. Ownership means that First Nations own their cultural knowledge, data, and information; control emphasizes that First Nations can control all aspects of research and information; access means that the data themselves have to be shared with First Nations; and possession refers to First Nations having physical control of data. These are very similar to the CARE principles for Indigenous data governance: Collective benefit; Authority to Control; Responsibility; and Ethics7 (GIDA, 2019), and fit within a broader and growing movement and literature base on the subject of Indigenous data sovereignty (Walter et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the concept of Etuaptmumk (meaning ‘the gift of multiple perspectives’ in Mi’kmaw) or ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’ might be helpful for non-Indigenous and Indigenous scientists alike in embracing knowledge pluralism in conservation. The relevance of Etuaptmumk was recently articulated for fisheries research and management (Reid et al., 2021), and similarly applies to conservation. As stated in that paper, this teaching “embraces ‘learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all,’ as envisaged by Elder Dr. Albert Marshall” (Reid et al., 2021). Etuaptmumk provides a pathway whereby Indigenous knowledge systems can be paired with, not subsumed by, Western scientific insights.

We strongly encourage readers to engage with these references and guidelines as but a first step in the learning process of how to support Indigenous conservation and create space for multiple ways of knowing in both research and management. Working in this space in a good way requires, amongst other things, being open to learning and self-reflection, while building relationships and trust with Indigenous partners, and being able and willing to stand aside to let Indigenous leaders lead. Guidelines such as these are just that, guidelines, and they need to be adapted to the needs and interests of Indigenous communities and partners, which will surely differ across contexts.

Conclusion

We demonstrated in this chapter that, in order to transform conservation science, we—all conservation scientists—must recognize that to uplift Indigenous conservation means supporting Indigenous Peoples in their conservation leadership. The examples we highlight are just two of many Indigenous Peoples leading stewardship in their territories. They are illustrative of the many and diverse forms of conservation that exist, and that all conservation scientists should uphold, including as part of integrating science and governance. For example, the holistic, intergenerational approach of the Kitasoo Xai’xais people has enabled them to stand up for their beliefs when federal management has endangered their territory. The Nisg̱a’a Nation provides one example of how ancient knowledge can be paired with modern techniques in the maintenance of respectful relations with salmon. These positive examples exist because of the many skilled and tenacious Indigenous leaders who continue to fight for their holistic view of the land, fresh waters, and sea. These examples showcase some of the many reasons why Indigenous knowledges, but particularly Indigenous knowledge systems, are so essential for conservation. In our view, it is not possible to support Indigenous conservation without a fundamental shift in the purpose and process of mainstream conservation science.

References

Adams, M.S., Carpenter, J., Housty, J.A., Neasloss, D., Paquet, P.C., Service, C., Walkus, J. and Darimont, C.T. (2014). Toward increased engagement between academic and indigenous community partners in ecological research. Ecology and Society, 19(3).

Akrigg, G.P.V. and Akrigg, H.B. (1997). British Columbia place names. 3rd edn. Vancouver, British Columbia. UBC Press.

Anderson, C.N., Hsieh, C.H., Sandin, S.A., Hewitt, R., Hollowed, A., Beddington, J., May, R.M. and Sugihara, G. (2008). Why fishing magnifies fluctuations in fish abundance. Nature, 452(7189), pp.835-839.

Atlas, W.I., Ban, N.C., Moore, J.W., Tuohy, A.M., Greening, S., Reid, A.J., Morven, N., White, E., Housty, W.G., Housty, J.A. and Service, C.N. (2021). Indigenous systems of management for culturally and ecologically resilient Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) fisheries. BioScience, 71(2), pp.186-204.

Atlas, W.I., Housty, W.G., Béliveau, A., DeRoy, B., Callegari, G., Reid, M. and Moore, J.W. (2017). Ancient fish weir technology for modern stewardship: lessons from community-based salmon monitoring. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 3(6), p.1341284.

Ban, N.C., Wilson, E. and Neasloss, D. (2019). Strong historical and ongoing indigenous marine governance in the northeast Pacific Ocean: a case study of the Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation. Ecology and Society, 24(4). https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7f66/a1755f27f9aee8babf54d30ce5d08544726b.pdf

Ban, N.C. and Frid, A. (2018). Indigenous peoples’ rights and marine protected areas. Marine Policy, 87, pp.180-185. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X17305547?casa_token=5o6ivd2LHuEAAAAA:RzCkpxtThzhQU3d_tGxZPumxXYCbxKrSLgby0vrWbhrFAqgGyWa6ekHHstv2b5-9X3A1wIjKVw

Ban, N.C., Frid, A., Reid, M., Edgar, B., Shaw, D. and Siwallace, P. (2018). Incorporate Indigenous perspectives for impactful research and effective management. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(11), pp.1680-1683.

Ban, N.C., Gurney, G.G., Marshall, N.A., Whitney, C.K., Mills, M., Gelcich, S., Bennett, N.J., Meehan, M.C., Butler, C., Ban, S. and Tran, T.C. (2019). Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas. Nature Sustainability, 2(6), pp.524-532.

Ban, N.C., Mills, M., Tam, J., Hicks, C.C., Klain, S., Stoeckl, N., Bottrill, M.C., Levine, J., Pressey, R.L., Satterfield, T. and Chan, K.M. (2013). A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: embedding social considerations. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11(4), pp.194-202.

Ban, N.C., Wilson, E. and Neasloss, D. (2020). Historical and contemporary indigenous marine conservation strategies in the North Pacific. Conservation Biology, 34(1), pp.5-14.

Bennett, N.J., Roth, R., Klain, S.C., Chan, K., Christie, P., Clark, D.A., Cullman, G., Curran, D., Durbin, T.J., Epstein, G. and Greenberg, A. (2017). Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. biological conservation, 205, pp.93-108.

Berkes, F. (2004). Rethinking community‐based conservation. Conservation biology, 18(3), pp.621-630.

Berkes, F. (2017). Sacred Ecology (4th ed.). Routledge. New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315114644

Bess, R. (2001). New Zealand’s indigenous people and their claims to fisheries resources. Marine Policy, 25(1), pp.23-32.

British Columbia. (2019). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, Bill 41, (SBC 2019). Chapter 44. https://canlii.ca/t/544c3

Cinner, J.E. (2005). Socioeconomic factors influencing customary marine tenure in the Indo-Pacific. Ecology and society, 10(1).

Cinner, J.E., Sutton, S.G. and Bond, T.G. (2007). Socioeconomic thresholds that affect use of customary fisheries management tools. Conservation Biology, 21(6), pp.1603-1611.

Cole, D. and Chaikin, I. (1990). An iron hand upon the people: the law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast. Douglas & McIntyre: Vancouver.

Colorado, P. (1988). Bridging native and western science. Convergence, 21(2), p.49.

Connors, K., Hertz, E., Jones, E., Honka, L., Kellock, K., and Alexander, R. (2019). The Nass Region: Snapshots of Salmon Population Status. The Pacific Salmon Foundation. Vancouver, British Columbia.

Corsiglia, J. and Snively, G. (1997). Knowing home: NisGa’a traditional knowledge and wisdom improve environmental decision making. Alternatives Journal, 23(3), pp.22-25.

Drew, J.A. (2005). Use of traditional ecological knowledge in marine conservation. Conservation biology, 19(4), pp.1286-1293.

Eckert, L.E., Ban, N.C., Tallio, S.C. and Turner, N. (2018). Linking marine conservation and Indigenous cultural revitalization. Ecology and Society, 23(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10417-230423.

Edwards, K. (2009). Dictionary of Tlingit. Sealaska Heritage Institute.

Fissel, D.B., Lin, Y., Scoon, A., Lim, J., Brown, L. and Clouston, R. (2017). The variability of the sediment plume and ocean circulation features of the Nass River Estuary, British Columbia. Satellite Oceanography and Meteorology, 2(2).

Gadgil, M., Berkes, F. and Folke, C. (1993). Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio, pp.151-156.

Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) (2019). Care Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, GIDA-global.org

Government of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Harris, C. (2002). Making native space: Colonialism, resistance, and reserves in British Columbia. University of British Columbia Press.

Jacobson, S.K. and McDuff, M.D. (1998). Training idiot savants: the lack of human dimensions in conservation biology. Conservation Biology, 12(2), pp.263-267.

Johannes, R.E. (2002). The renaissance of community-based marine resource management in Oceania. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, pp.317-340.

Jupiter, S.D., Cohen, P.J., Weeks, R., Tawake, A. and Govan, H. (2014). Locally-managed marine areas: multiple objectives and diverse strategies. Pacific Conservation Biology, 20(2), pp.165-179.

Kimmerer, R.W. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed editions.

Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation. (2019). Kitasoo Xai’xais Management Plan for Pacific Herring. Kitasoo Xai’xais Integrated Resource Authority. Klemtu, British Columbia, Canada.

Lam, M. (1998). Consideration of customary marine tenure system in the establishment of marine protected areas in the South Pacific. Ocean & Coastal Management, 39(1-2), pp.97-104.

Lepofsky, D. and Caldwell, M. (2013). Indigenous marine resource management on the Northwest Coast of North America. Ecological Processes, 2(1), pp.1-12.

Magallanes, C.J.I. (2015). Maori cultural rights in Aotearoa New Zealand: Protecting the cosmology that protects the environment. Widener L. Rev., 21, p.273.

Margules, C.R., and Pressey, R.L. (2000). Systematic conservation planning. Nature, 405(6783), pp.243-253.

McKechnie, I. (2007). Investigating the complexities of sustainable fishing at a prehistoric village on western Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Journal for Nature Conservation, 15(3), pp.208-222.

Miller, B.W., Caplow, S.C. and Leslie, P.W. (2012). Feedbacks between conservation and social‐ecological systems. Conservation Biology, 26(2), pp.218-227.

Moller, H., Berkes, F., Lyver, P.O.B. and Kislalioglu, M. (2004). Combining science and traditional ecological knowledge: monitoring populations for co-management. Ecology and society, 9(3).

Moon, K. and Blackman, D. (2014). A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conservation biology, 28(5), pp.1167-1177.

Nadasdy, P. (2005). The anti-politics of TEK: the institutionalization of co-management discourse and practice. Anthropologica, pp.215-232.

Nisga’a Lisims Government (2019). Fisheries Management. https://www.nisgaanation.ca/fisheries-management

Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife. (2019). Nass River Salmon Stock Assessment Update. pp. 34.

Nursey-Bray, M. and Jacobson, C. (2014). ‘Which way?’: The contribution of Indigenous marine governance. Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, 6(1), pp.27-40.

Nursey-Bray, M. and Rist, P. (2009). Co-management and protected area management: Achieving effective management of a contested site, lessons from the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (GBRWHA). Marine Policy, 33(1), pp.118-127.

Ommer, R.E. (2007). Coasts under stress: restructuring and social-ecological health. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Osterhoudt, S.R. (2018). Community Conservation and the (Mis) appropriation of Taboo. Development and change, 49(5), pp.1248-1267.

Pressey, R.L. and Bottrill, M.C. (2009). Approaches to landscape-and seascape-scale conservation planning: convergence, contrasts and challenges. Oryx, 43(4), pp.464-475.

Redford, K.H. and Richter, B.D. (1999). Conservation of biodiversity in a world of use. Conservation biology, 13(6), pp.1246-1256.

Reid, A.J. (2020). Fish–People–Place: interweaving knowledges to elucidate Pacific salmon fate (Doctoral dissertation, Carleton University).

Reid, A.J., Eckert, L.E., Lane, J.F., Young, N., Hinch, S.G., Darimont, C.T., Cooke, S.J., Ban, N.C. and Marshall, A. (2021). “Two‐Eyed Seeing”: An Indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish and Fisheries, 22(2), pp.243-261.

Robinson, J.G. (2006). Conservation biology and real‐world conservation. Conservation Biology, 20(3), pp.658-669.

Schuster, R., Germain, R.R., Bennett, J.R., Reo, N.J. and Arcese, P. (2019). Vertebrate biodiversity on indigenous-managed lands in Australia, Brazil, and Canada equals that in protected areas. Environmental Science & Policy, 101, pp.1-6.

Scott, A. (2009). The Encyclopedia of Raincoast Place Names: A Complete Reference to Coastal British Columbia. Harbour Publishing.

Snively, G. and Corsiglia, J. (2016). Indigenous science: Proven, practical and timeless. Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science with Western Science (Book 1); Snively, G., Williams, WL, Eds, pp.89-104.

Soulé, M.E. (1985). What is conservation biology?. BioScience, 35(11), pp.727-734.

Thompson, K.L., Lantz, T. and Ban, N. (2020). A review of Indigenous knowledge and participation in environmental monitoring. Ecology and Society, 25(2).

Tran, T.C., Ban, N.C. and Bhattacharyya, J. (2020). A review of successes, challenges, and lessons from Indigenous protected and conserved areas. Biological Conservation, 241, p.108271.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Turner, N.J. and Berkes, F. (2006). Coming to understanding: developing conservation through incremental learning in the Pacific Northwest. Human ecology, 34(4), pp.495-513.

UN General Assembly. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/295. https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html.

Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Carroll, S.R. and Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (2021). Indigenous data sovereignty and policy (p. 244). Taylor & Francis.

Weinstein, M.S. (1999). Pieces of the puzzle: solutions for community-based fisheries management from native Canadians, Japanese cooperatives, and common property researchers. Georgetown International Environmental Law Review, 12, pp.375.

Wilson, E.O. (1999). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Vol. 31). Vintage Books, pp.382.

Winter, K.B., Beamer, K., Vaughan, M.B., Friedlander, A.M., Kido, M.H., Whitehead, A.N., Akutagawa, M.K., Kurashima, N., Lucas, M.P. and Nyberg, B. (2018). The moku system: managing biocultural resources for abundance within social-ecological regions in Hawai'i. Sustainability, 10(10), p.3554.

1 The University of British Columbia, https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=WWdYxJgAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=sra

2 ‘Peoples’ and ‘knowledges’ are used in these pluralized forms here and throughout the chapter to reflect the plurality of knowledge systems (as well as cultures, identities, traditions, languages, and institutions) across distinct Indigenous Nations both in Canada and around the world.

3 Ideas and some text for this section are taken or adapted from previously published sources of Ban et al., 2019 and Ban et al., 2020. All information in this chapter about the Kitasoo Xai’xais peoples comes from these two articles, co-authored with Doug Neasloss and Emma Wilson.

4 http://reseaumtlnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Ally_March.pdf

5 https://www.ilinationhood.ca/publications/how-to-be-an-ally-of-indigenous-led-conservation