I. Enclosure

© 2024 H. Lähnemann & E. Schlotheuber, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0397.01

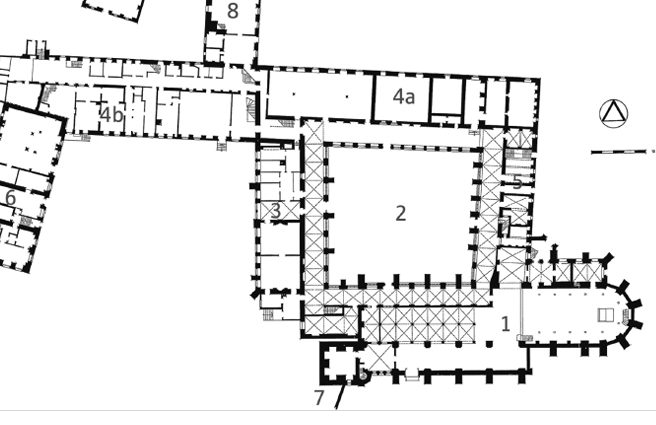

Fig. 1 Floor plan of the monastic buildings at Ebstorf. 1 Church. 2 Cloisters. 3 Abbess’s House. 4 Dormitory on the first floor. 5 Bell. 6 Clergy. 7 Lodge. 8 Kitchen. ©Klosterkammer Hannover

Monastic houses are built around the concept of enclosure, the cloistered life away from the world as can be seen still in the floor plans for example of the Lüneburg convents. In its basic features, the plan of the Benedictine convent of Ebstorf (Figure 1) goes back to the time of the world map (Figure 8), on which the convent is represented by a stylized house with a cross on top (Figure 9). The centre of the plan is occupied by the convent church with its choir orientated towards the east and the nuns’ choir spanning the western half of the church, above a vaulted lower church for the laity. The nuns could access their choir from the cloister to the north of the church, around which lay the chapter house, refectory, and the other communal rooms. The congregation could access the lower church from the south side. The cloister had stained-glass windows and figured keystones (Figure 25). The gatehouse was to the south-west of the church. Not shown here are the farm buildings which lay outside the complex of connected buildings.

1. The Nuns’ Flight

Characteristic features of the nuns’ particular way of life become apparent at precisely the moment when this order is disturbed, when war breaks out and the nuns are forced to flee, just as the author of the diary from the Heilig Kreuz Kloster reports for the year 1492.

Suddenly in the Midst of War: The Great Braunschweig Civic Feud

On 12 August 1492 the young Duke Henry the Younger sent written challenges into the town of Braunschweig. Braunschweig’s town councillors had refused to pay homage to the new duke, who did not wish to confirm their ancient rights and freedoms. The Cistercian Heilig Kreuz Kloster, marked as ‘Convent s. Crucis’ on the Rennelberg, a hill to the northwest of the town, lay between the ducal residence in Wolfenbüttel and the town of Braunschweig, just outside the town walls.9

The nuns were in turmoil. What were they to do? Stay and hope the duke would spare them, or leave convent and enclosure and flee to Braunschweig? War loomed on the horizon, and the town councillors urged the nuns to flee. Not just the council’s messengers but also townswomen came to the convent and painted a colourful picture of the duke’s atrocities – the nun reports in direct Low German speech their pleas: ‘Dear children, where do you intend to stay? The duke is closer to us than you yourselves believe’, with another one adding: ‘Run, run, dear children, run, he already stands with his army before the Krüppelholz (stunted wood)’. Time and again they came out to the convent and pressed the women: ‘Dear children, are you still here? The duke is already inside the lines of fortification and wanted to take the cows from the old town. Alas, alas! If we had you inside the town, we would know that you were kept safe, that you would not be robbed of the noble treasure of your virginity’.10 Still, the nuns hesitated – violating enclosure was a serious step.

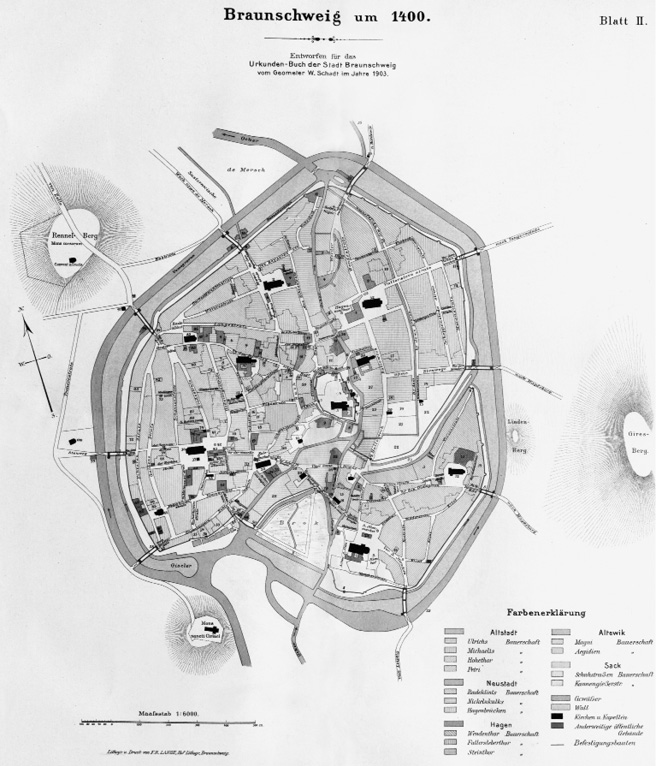

Fig. 2 Map of Braunschweig around 1400. ©W. Schadt, 1903.

Their fear and uncertainty speak to us vividly through the diary of the nun from the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, who does not reveal her name but recounts many of these moving events. The nuns did not hesitate without reason. They knew full well that the Braunschweig town councillors were parties in the dispute. In her diary, the Cistercian nun shrewdly notes that the nuns were more exercised by the horrific nature of the reports than by the actual danger. They also knew it was an easy matter to bombard the town from their well-fortified convent. For that reason, the council had a considerable interest in the nuns’ moving into the town so that they could billet town soldiers in the convent before the duke arrived and seized it. Suddenly, the nuns from the Heilig Kreuz Kloster found themselves at the heart of the conflict; furthermore, they occupied the centre ground between the two parties not just spatially but also socially. Within the convent walls, the daughters of the Braunschweig *patriciate, that is, of the urban upper bourgeoisie, lived harmoniously side by side with the daughters of noble families from the surrounding area. That had not happened by chance. The Cistercian Heilig Kreuz Kloster had been founded as an act of atonement and owed its establishment to a feud which had broken out in 1227 between the traditional chivalric nobility and the up-and-coming town of Braunschweig. At that time, the *ministeriales had taken advantage of a tournament outside the town walls to launch a surprise attack on the town by armed knights. The citizens of Braunschweig had known how to hold their own and had subsequently forced the nobles to found a convent on the Rennelberg, their former jousting field, in atonement for their act of violence (see Figure 2 for the position of the hill). The endowment of a convent just outside the town gates brought with it many advantages. It freed the citizens of Braunschweig from the presence of the knights and their tournaments directly before the gates, particularly since tournaments could always also be used as preparation for military campaigns. Instead, an enclosed site was created where the daughters of the citizens of Braunschweig and the surrounding nobility could together lead a spiritual life and hence, in their way, serve to safeguard the peace between the rival social classes.

This solution succeeded for centuries, but old antagonisms resurfaced with the Great Braunschweig Civic Feud in August 1492. In this tricky situation, the nuns were at a loss; as the conflict came to a head, they packed up all their worldly goods, their bedding, their good cloaks and veils and sent everything off by messenger to their relatives, where it was out of harm’s way. Town mercenaries were already loitering around the convent day and night, but – as the author of the diary bitterly remarks – less for their protection than to hold the location for the town. While they were, admittedly, not permitted to enter the *enclosure, the women’s inner domain, they ran amok in the courtyard, the kitchens, and the storerooms. In the process, they gave the nuns’ provost such a fright that he told the women he intended to leave the convent and seek safety in the town. If they wished to remain, that was their responsibility. This did not improve the situation.

Some nuns recommended sending letters to those noble families with connections to the convent who also exercised influence in the ducal council in order to ask them to spare the nuns and the convent. This discreet diplomacy bore fruit inasmuch as the addressees of the letters promised to intervene with the duke on the nuns’ behalf to the best of their ability. Yet they warned that, due to the readiness on the part of the various armies to use violence, the women’s protection could not be guaranteed. The nuns were in a real dilemma, since they could not achieve certainty by this means either. Hence the Cistercian nun adds to her diary something we rarely hear: unvarnished criticism of the way the Mother Superior Abbess Mechthild von Vechelde, only recently elected, exercised her office. The author of the diary complains that in those fearful days, they had been like lost sheep – and precisely because their shepherdess, the abbess, had been as if paralysed by fear and panic and was completely at a loss to know what to do. For that reason, she had made promises which subsequently had to be rectified amidst expressions of remorse.

It was no longer possible to think of an orderly daily routine. On the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin (15 August), they once more undertook a communal procession through the convent, cloisters, and cemetery. When they looked through the bars on their windows the following morning, they saw terrifyingly armed knights, heard shots, and heard the bells ringing. Then, during the night, messengers came from the council who more or less ordered them to leave the convent. Their departure had been decided. In the morning, the nuns gathered punctually in the church on the chiming of the bell in order to place themselves and the convent into the hands of God. Our Cistercian nun relates that they wept and wailed so much that they were hardly able to sing. Together they intoned the *antiphon ‘O cross, more splendid than all the stars’, which they knew so well.11 This was followed by five recitations of the *paternoster before they entrusted themselves to God and their patron the Holy Cross and, amidst a veil of tears, left the choir.

For their departure, they lined up in the normal processional order: at its head the provost and his clerics; followed by Abbess Mechthild von Vechelde, at whose side a townswoman from Braunschweig was placed as an escort; then Prioress Remborg Kalm and the oldest nuns, the seniores; then the *subprioress and, finally, all the nuns who had already been consecrated as well as the novices, the girls with their magistra. These were followed by the *lay sisters; and two or three men and the remaining women brought up the rear. A similar procession is depicted in the panel painting from Medingen which shows the move from the old to the new convent place (Figure 16). They all solemnly walked together to the Grauer Hof,12 the farmyard and economic centre of the Cistercian monks in Braunschweig.

Exile

The Grauer Hof at the south end of the ‘plank way’,13 the central medieval street in Braunschweig, belonged to the Cistercians in Riddagshausen, who stored and sold the grain produced by their farms there.

Fig. 3 Map view of the Grauer Hof in Braunschweig. Albrecht Heinrich Carl Conradi c. 1755. ©Stadt Braunschweig.

A monk from Riddagshausen received the group and led them in. Initially he showed them only a single room. It rapidly became clear to the provost and his clerics that they could not remain there with the women because there was not enough space to accommodate both groups. Hence, in tears, the latter bade the provost goodbye for this first night. Together the nuns read *compline in the room into which they had been led by the monk and, exhausted, fell asleep perched in the window niches or with their heads leant against the walls. The next morning, things assumed a very different complexion. The monk returned and showed them a chapel in which they could celebrate divine office; two rooms which were suitable for a communal dormitory; and for the abbess, a room of her own. The room in which they had passed the first night was transformed into a refectory, and there was even a heated chamber with hot-air heating from a stone oven, so-called hypocaust heating, and eleven seats which could be warmed by hot air. Now, in the light of day, they discovered in the middle of the Grauer Hof complex a large courtyard with trees and a small pond for which the provost procured them some fish. Ultimately, a solution was also found for all the other duties which made up their daily religious routine: the nuns took communion in a room by the entrance to the chapel, but always with the doors closed. They equipped a small chamber above the chapel, the gallery (priche), as their space for confession. It was so cramped that they were obliged to kneel in front of their father confessor, without a screen between them. They also used the room in front of the chapel as a place for the sermons normally preached to them by their father confessor, the provost, or sometimes even by a cleric invited from outside the convent. The daily reading (collatio) after *vespers took place there as well and on Thursdays the washing of feet. In the chapel itself, they sang the seven *hours together every day, celebrating the divine office as they always had.

There was a clear hierarchy amongst the rooms in monasteries and convents, one dictated by their sacred function and significance, and very important to the nuns and monks. At the heart of monastic life was the daily assembly in the *chapter house, the meeting of the monastic chapter. In exile, the nuns chose the room in front of the church for this purpose, but because it could not be securely locked and since it was a place where topics meant exclusively for the nuns were dealt with – such as breaches of the rules and other sensitive issues – it was not an ideal environment.

During the period of exile, communal processions which in the convent could take place in the sheltered space of the cloisters, had to be cancelled completely. The Braunschweig town councillors certainly kept an eye on the nuns in their enforced place of refuge. As a precaution, they ordered the monk from Riddagshausen to return to his monastery after a few days. The provost and his clergy, who celebrated mass for the nuns and were their spiritual advisors, as well as the cook, the baker, and some other servants, remained with them, albeit in separate accommodation. However – the diarist adds critically – they were not as securely separated by locks and bolts as they should have been. Each group in the monastic community had its own household, which had to be reorganized here. The cook for the priests and the *familia, i.e. the nuns’ secular servants, and the lay sisters all cooked together and warmed themselves at one fire; the priests and scholars and rest of the familia at another. The spatial separation of the different social groups in the community, men and women, was thus established on a makeshift basis. This was necessary for a monastic life in strict enclosure such as lived by the Cistercian nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster. Separation was the basis for their way of life and the prerequisite for their most important task, namely, divine service and the performance of the *liturgy. In the nuns’ own understanding of themselves, the quality of their prayers and worship depended upon the quality of their spiritual life in enclosure, upon the regular fulfilment of their duties and their inner turning towards God. Ensuring this in exile was a great challenge, one which the community now had to face together – and it was not possible to find a good solution for everything.

Enclosure had been carefully protected by the structural organization of medieval monasteries, but now the community had to improvise. For the celebration of mass, the priests, along with the scholars and everyone else who took part in the mass, had to pass through the rooms where the women resided. Thus, the Cistercian nun writes worriedly, they could hear and see everything that was otherwise hidden from them and all the more secret things, even if they physically turned away. The provost had impressed upon the male clergy that they should keep as far away from the women as possible; and the abbess ordered the nuns that no one was allowed to leave the premises assigned to them without special permission, except the chapel mistresses for the preparation of the liturgy, the cellar mistress, and the lay sisters for their various jobs and tasks. According to the diarist, the majority of the men and the women carefully observed the prohibitions, ‘but some were curious and stood at the windows or went under some pretext into the kitchen and the weaving mill, where the priests, scholars and servants quite frequently exchanged a few words with the lay sisters, because they wanted to see and be seen, hear, and be heard’.14 She concludes this delicate subject by observing: ‘However, with God’s help and through the Virgin Mary’s intervention, and although some were rather careless and went without witnesses or a companion to places forbidden to us’, fortunately nothing bad happened, although there were rumours. Here the diarist addresses her readers directly: ‘Of this I write nothing further for now, but I admonish those who will read this in the future so that they take note and understand and take care of themselves and theirs not to run into similar dangers’.15

Even personal hygiene was not easy in the new situation. There was a small apple orchard in the courtyard, where the women installed a large barrel as a bathtub and, as the diarist joyfully notes, had their bathhouse without a roof and a stove, ‘which we liked very much, even in winter in the cold air’. Of course, the courtyard was damp, and the women suspected it was a breeding ground for pests. One day, when an old and already slightly infirm sister sat in the cell block for an hour or two and looked at her coat, she discovered it was ‘alive’: it was crawling with worms and lice. Initially she said nothing and hid it as best she could, but then the same thing happened to other sisters, and they could no longer conceal it because the lice bit so fiercely. When they collected the clothes to wash them, it turned out that most of the community was infested with this plague of lice.

In the meantime, the duke laid siege to the town and tried to starve it into submission. It became increasingly difficult to obtain food, with the result that the women in Braunschweig who could no longer support themselves and their families through their work painted their faces black to avoid detection and at night walked as far as Peine and Hildesheim to procure food, which they then sold in the town at double the price. The abbess also bought from them for the community of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster because there was nothing else. A Braunschweig chronicle also mentions these women, who successfully undermined the duke’s attempt to starve the town. Under the heading ‘Of the Enemies of Women’ it says the duke was so incensed by their actions that he sent letters of feud against the women into the town so that he could declare them combatants, i.e. enemies in war, and could fight them. While famine was breaking out in the city, the lay sisters and clerics ran back to the Heilig Kreuz Kloster on numerous occasions and brought everything they could carry and use from there into the town. In the process, the scholars found in various places in the convent and in the cells the braids which had been cut off the girls when they had entered the religious estate, a practice comparable to the shaving of the tonsure in monks. They had hidden them in every conceivable nook and cranny in their cells. According to the diarist, because the scholars were honourable, nothing bad had happened to them. She continues: ‘But they told the lay sisters how stupid and careless we were, that we did not keep our braids in a safer place, especially when we left the convent, not knowing what kind of people we would encounter and how much danger to our virginity could arise from that’.16 What the scholars and lay sisters could not take with them, such as the devotional pictures on the walls and some other, less valuable items, was stolen by town women and others who roamed through the place and took everything holy they could find, ‘which filled our hearts with very great sorrow’.17

On the occasion of the nuns’ exile, the diarist’s stories reveal for the first time the everyday life and spiritual interaction that were otherwise hidden from the eyes of contemporaries. Because she also reports everyday occurrences in what was for them a highly unusual, threatening situation, she also gives later readers a special, and vivid, insight into a life otherwise shielded and protected by walls and secure enclosure.

2. The Convent Living Space

A medieval convent was a complex organism which included women and men, different social groups, and many people who were tied to the women’s community with varying degrees of closeness. All these groups had specific tasks and their own needs, for which they required their own living spaces. The organizational form of medieval women’s religious houses, like that of men’s, had developed over centuries. Their space was oriented towards the church as the sacred centre where all involved parties gathered. In the sacral hierarchy, second place was occupied by the area which comprised the enclosure of the women; and then the sphere of the lay sisters and brothers, who, because of their countless tasks in the convent yard and the fields, lived a ‘semi’-spiritual life between the convent and the world, so to speak. The complex structure that was the ‘convent’ had constantly to be adapted to the respective local conditions and its occupants.

Convent and Enclosure: On Terminology

What becomes particularly clear in the account of the forced flight to Braunschweig is the significance of enclosure for a convent: the state of being closed off from the world can be taken as the very definition of a monastic house, particularly for women. The German word ‘Kloster’ (which existed in medieval English as closter) derives from the Latin claustrum, past participle of the verb claudere (to close), which in medieval Latin took the popular form clostrum. In German, the term refers to monastic houses in general, which can be specified as for men (‘Männerkloster’) or women (‘Frauenkloster’). The English term ‘cloister(s)’ which came from the same root via Old French cloistre into English, more specifically just means the inner part of a monastic community, particularly a ’covered walk or arcade connected with a monastery, college, or large church, serving as a way of communication between different parts of the group of buildings, and sometimes as a place of exercise or study; often running round the open court of a quadrangle, with a plain wall on the one side, and a series of windows or an open colonnade on the other’.18 The term ‘monastery’ from post-classical Latin monasterium (‘monk’s cell, monastery’), which is a loan word from Byzantine Greek (μοναστήριον) of the same meaning, derived from the Hellenistic Greek verb for ‘living alone’ (μονάζειν). It was taken over into the vernaculars as ‘Münster’ (in German, as in ‘Freiburger Münster’, the Cathedral including the ‘Münsterbauhütte’, the medieval workshop still attached to it) or ‘Minster’ (in English, as York Minster); even though the nuns sometimes refer to their institution as monasterium, in English it traditionally just referred to religious institutions for men even though the latest edition of the Oxford English Dictionary now allows more flexibility. OED2 defines ‘monastery’ as ‘A place of residence of a community of persons living secluded from the world under religious vows; a monastic establishment. Chiefly, and now almost exclusively, applied to a house for monks; but applicable also to the house of any religious order, male or female.’ OED3 allows more flexibility with ‘A place of residence for a community living under religious vows, esp. the residence of a community of monks.’ Still, for the German ‘Frauenkloster’, in this book the term ‘convent’ is used, even though this means a doubling of use: both for the community of nuns and for the institution they inhabit. The word ‘enclosure’ like ‘Kloster’ comes from claudere, with the added prefix ‘in’ after the Old French verb enclore which also gave English the word ‘inclusive’.19 The walls surrounding the convent limit the women’s sphere of activity to the inside, but also offer protection from the outside. The outer world was meant to be closed off so that an inner one could open up. Accordingly, the convent life of the old orders – such as the Benedictine and Cistercian nuns – served contemplation and meditation. Later Protestant historiography perceived only the function of confinement: the novels of the nineteenth century are full of figures of poor imprisoned girls who long for their romantic liberator from the dungeon that was the convent and who are trapped within its walls against their will by the clerics and the abbess. One of the most frequent word combinations in German is ‘to lock up in a convent/monastery’.20 In English, this is apparent in the derogatory undertones which ‘nunnery’ acquired over the early modern period, ‘get thee to a nunnery’ in Hamlet III.i, even playing with the anti-Catholic Tudor meaning of ‘brothel’. The Middle Ages, however, viewed the religious space very differently.

The exile of the nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster shows how difficult it is for the community to leave this shelter. In the Lüne letters, too, the women themselves consistently use positive images when they speak of enclosure. It is their space. It is the ‘vineyard of the Lord’, fenced in against wild boars; or the ‘rose garden’, where, like the bride in the Song of Songs, the women can walk with Jesus as their sweetheart. On the Wichmannsburg *Antependium, for example, a richly embroidered altar cloth produced by the nuns of Kloster Medingen and used in the parish church of Wichmannsburg that belonged to the convent, a woman sits at the foot of the cross in a rose garden enclosed by a woven fence, gathering flowers in a cloth, with a Middle Low German caption that links the delight of gathering flowers and seeing her beloved, i.e. Christ, as part of the garden experience.

Fig. 4 Wichmannsburg Antependium, Kloster Medingen, late 15th century. Photograph: Christian Tepper. ©Landeshauptstadt Hannover.

Nuns’ Choir, Chapter House, Refectory, Dormitory: On the Architecture of the Convent

Because protection was derived from this very seclusion, the channels of communication were particularly important. Naturally, close contacts to and well-established spaces for communication with the outside world were needed. The convent area was usually only permeable for this world in three places: first, at the convent gate, which for the nuns symbolized the narrow gate leading to the kingdom of heaven; second, at the communication grille, where the nuns could converse with their relatives from the city at visiting times; third, in the convent church, which, however, was also divided into distinct areas according to the sacral hierarchy: the east was the place for the clergy; while the west was, in many cases, divided into a lower church for the local congregation and above them the *nuns’ choir.

As can still be seen today in Wienhausen in Lower Saxony, for example, the nuns’ choir could take on the dimensions of a small church, equipped with choir stalls and altars for worship. At west end, the seat of the abbess is located; on the south and north side, the nuns sit in the stalls, with lower benches for the novices who would only join in at certain times (for further images of the architecture from the inside and seen from outside see Chapter VII.3).

Fig. 5 Nuns’ choir at Wienhausen, looking towards west. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Wienhausen.

Since the nuns met in the nuns’ choir for matins at night or early in the morning, the distances had to be short. The nuns usually reached it via their own corridor, directly connecting the dormitory on the upper floor of the cloister with the nuns’ choir. The significance of the nuns’ choir as a sacred space is clear from the fact that the lay sisters were only allowed to enter it on special feast days. Moreover, they were not allowed to use the path through the nuns’ choir as a shortcut to reach the church more quickly.

Another area reserved for the choir nuns was the chapter house, even though the provost could join them for important events. As the report from the Braunschweig exile of the nuns from the Heilig Kreuz Kloster makes clear, it formed the centre of communications within the community because the daily assemblies took place there. During their exile, improvisation was necessary, and the nuns rededicated a room not originally intended for this purpose; otherwise, the chapter house was often an area of the convent which boasted specifically designed architecture and was decorated, like the church, with columns and ornaments to emphasize the importance of this representative community space. Here reports were given, the course of the liturgy on feast days was discussed, plans were deliberated and decisions taken for the future.

For this purpose, the lay sisters had their own area, the workhouse, where they performed manual work. It had to have good light and was situated somewhat outside the narrower area of enclosure, the architectural backbone of which was the *cloister. Accordingly, the lay sisters’ dormitory was located in a wing further away from the church and closer to the work area.

The kitchen was the realm of the celleraria, who supervised the lay sisters, who then served the food in the refectory. In the refectory, the nuns sat at long tables with the abbess presiding over them while the lectrix, the ‘reader’ designated for that occasion, read spiritual works out aloud to them. We know from Kloster Lüne that an important part of the conventual reform (which is discussed in detail in Chapter V) was the return to communal meals. An experienced housekeeper (celleraria) was sent from Kloster Ebstorf especially for this purpose, one who knew how to provide for all those living in the convent throughout the year. This can also be seen on a panel from Kloster Medingen depicting the reform; on the left it shows the celleraria seasoning the stew cooked by a lay sister in the large cauldron (Figure 26, Chapter V.2).

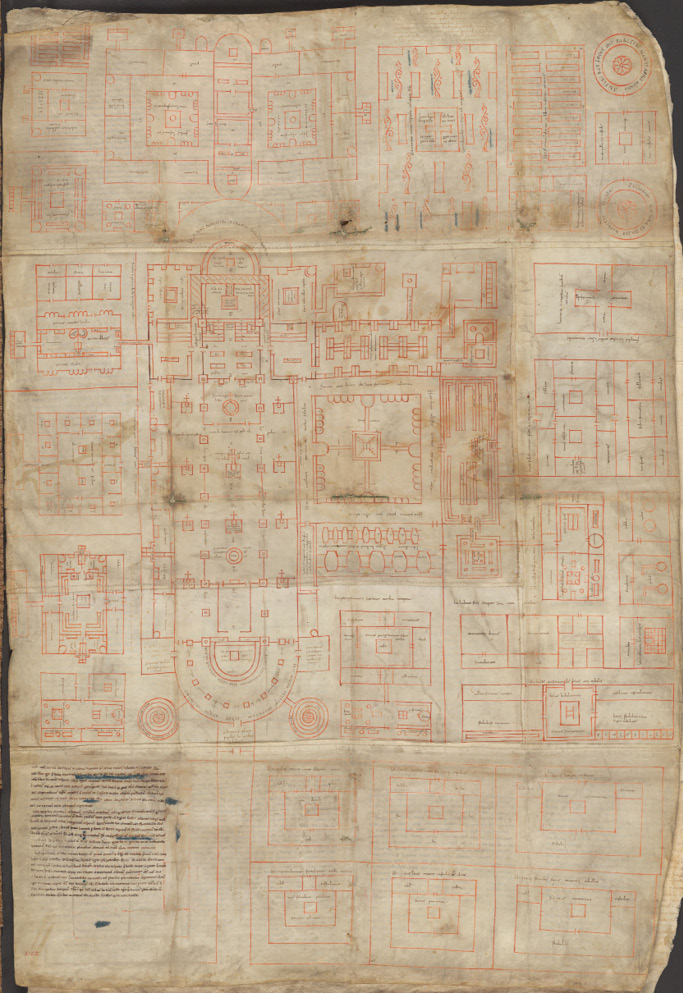

Fig. 6 Plan of St Gall, Reichenau, early 9th century. Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen, Ms. 1092. Public domain.

On the whole, the basic layout found in a men’s monastery also applies to women’s convents. It is best known from the Plan of St Gall, the earliest surviving visual representation of any architecture complex, which outlines forty different areas for praying, living, eating, healing, entertaining guests, and managing the monastic economy.21

This ideal plan was implemented in religious institutions for women even more rarely than for male communities, whether completely or even to a considerable extent. Unlike monasteries, convents were more frequently founded by rededicating existing buildings, which were then extended piecemeal and as needed. Within the convent walls, one thus often finds a loose conglomeration of buildings rather than the precisely encircled complexes of e.g. Cistercian foundations for men which followed clear building regulations. This complexity, illustrating the growth of the female community over the centuries and the adaptation to new demands on the organization of their space, makes architectural complexes like Kloster Lüne so attractive. Here a Baroque house stands side-by-side with red-brick Gothic, and an ultramodern textile restoration workshop gets a dedicated space above a purpose-built textile museum.

Hours, Masses, Church Year: On Monastic Structures of Time

The nuns’ daily routine was determined by structuring time into multiple layers. True to the words of the Psalm 113:3, ‘From the rising of the sun to its setting, praise be to the name of the Lord’ and to Psalm 119:164, ‘seven times a day I praise you’, the prayer times, also called the *canonical hours after the Latin word hora for hour, were spread across the day from sunrise to sunset and even beyond, since the nuns, like the Wise Virgins from Christ’s parable,22 wished to be properly prepared to meet their bridegroom at midnight. In the convent, the day was structured by the seven hours during which, above all, the psalms were recited. The table in the Appendix (Chapter VIII.2) provides an overview of the resulting daily structure. The day began after sunset, a tradition which to this day has been preserved for Christmas with Christmas Eve. In the evening, compline concluded the day’s work and matins began the new day. Nocturns, the night prayers, were celebrated at matins in the early hours of the morning so that the night’s rest was not interrupted.

The day had different lengths in summer and winter since it was not based on modern time but on sunrise and sunset. At dawn, the nuns rose for the second time for prime, followed by the chapter office, for which the entire convent went to the chapter house in the east wing of the enclosure. The so-called ‘chapter’ took its name from the reading of a chapter from the rule of the order and was the most important gathering point for the community. The chapter was presided over by the abbess of the convent; and the nuns sat on her right and left according to their ‘professed age’, i.e. the date of their *profession – a seniority rule still observed in the seating plan for the Protestant convents. At chapter, the abbess or prioress gave addresses on spiritual matters to the community; violations of the rule were punished, the daily schedule was discussed, and the particular tasks for the day were distributed. In addition, the deceased members of the convent, lay sisters and brothers or benefactors were remembered. Afterwards, one to two hours were free for the work which was waiting to be done before the convent gathered again for terce, the third hour, after which, at about 10 o’clock, followed the conventual mass, which the nuns attended in the nuns’ choir. Only then, at around 11 a.m., came the first meal of the day, the prandium, which orders leading a communal life took together in the refectory. At the communal meals, a sister undertook the table readings, which included exegetical writings by the church fathers, explanations of the liturgy or exemplary stories, as well as descriptions of the lives of exemplary saints. Sext was sometimes recited before the meal, sometimes after it; then the nuns had none in the early afternoon, followed by time for work or rest. Vespers concluded the working day. At around 5 or 6 p.m., the convent gathered again for dinner in the refectory. Before the night’s rest, which began with the onset of darkness, there was often an evening reading (collatio) in the north wing of the cloister, usually with a fortifying drink, before the day was placed in God’s hands with the Canticle of Simeon during compline.

The prayer books of the nuns from Kloster Medingen clearly illustrate how every step of the daily routine is symbolically charged. When rising in the morning, the nun is supposed to think of Christ’s resurrection from the dead; when putting on her robe, of Christ one day clothing her with the robe of eternal life; when going to the nuns’ choir, of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem etc. A layer of spiritual meaning is superimposed on the structures of convent life, one which elevates everyday life symbolically, interpreting it in terms of the history of salvation. In the eyes of both the nuns and the monks themselves, as well of the broader community outside the convent, their ‘service’ to God was central to the salvation of humanity. They could thus be seen as experts in the immaterial for the semantic space beyond the material world: for that reason, they always located themselves within larger contexts of space and time.

This is particularly apparent in the division of the year, determined by the events of the history of salvation recurring within the liturgy. At Christmas, the devotional texts instructed the nuns to help the Virgin Mary swaddling and caring for the Christ child (quite literally, in the case of the devotional cradles sometimes used in convents or clothing the doll-like statues from Brabant). In Passiontide, they were called to suffer with him by contemplating his wounded limbs (see Figure 24 for the larger-than-life figure of Christ of the Holy Sepulchre from Kloster Wienhausen), thus enabling them to encounter the risen Christ once more on Easter along with Mary Magdalene. The extent to which the Liturgy of the Hours allowed the nuns to participate directly in biblical events is particularly evident at Easter, when Christ is equated with Sunday, the course of which is followed from hour to hour. In this, they are emulating the passage of time, from the Resurrection at sunrise to the evening, when Christ is invited to stay with the two disciples encountered on the road to Emmaus.

The church year is structured in such a way as to repeat the history of salvation, made audible and tangible in the liturgy by the nuns who simultaneously insert themselves into events that encompassed time and space. Since their enclosure meant that they were forbidden to go on pilgrimages, they visualized Rome or Jerusalem as a spiritual pilgrimage within their own cloister and the church. Conceptual designs such as that of the Ebstorf World Map (Figure 8) rendered concrete the imagined order of time and space. The Liturgy of the Hours was conducted by the nuns themselves, with the singing of the psalms alternating between both sides of the choir stalls and led by the precentrix and her deputy. High mass and feast-day masses, on the other hand, were public affairs for which, if the convent church was also the parish church, the local congregation attended the service. In these cases, the nuns could hear and therefore follow the proceedings at the high altar in the east from their gallery. To this day, a candelabrum in the shape of a garland with a Madonna in an aureole hangs above the nuns’ choir in Kloster Lüne.23 It has two faces: one looks down on the nuns from close by, while the other is visible from a distance to the clergy in the east choir. A renovation note from 1649 shows that it continued to be in use after the Reformation.

Fig. 7 Candelabrum from the nuns’ choir. Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis ©Kloster Lüne.

Some convent churches included a Holy Sepulchre, or alternatively, the altar doubled as the Tomb of Christ, which could be approached together with the Three Marys (see Figure 24 for the Wienhausen entombed Christ). While the priests chanted about Christ’s descent into limbo to free the Old Testament patriarchs, the arrival of Christ’s advance could be followed in the liturgy as if in real time. At Christmas, the altar then became the manger from which the priest could lift the host representing the Christ Child. More on this can be found in the chapter on the sacred and social space of the convent (Chapter V.2).

In addition to the division of the day and the structure of the church year, there were also special feast days, especially for the saints. Each *psalter, the basic manuscript of the psalms which the nuns used daily, begins with a calendar of feasts and commemorative days, both those of the convent in general and those of the individual scribe or user. Each women’s convent had its own canopy of saints which determined which feasts were particularly highlighted. The English expression ‘a red-letter day’ for special events comes from the medieval practice of highlighting particularly important feasts in red.

In addition to saints’ days on which the patron saints of the convent were celebrated, for example, there were numerous days of personal celebration and commemoration. Widespread throughout the late Middle Ages was the assigning of an apostle who, like the guardian angel, personally watched over those entrusted to his care. This ‘personal apostle’, who was responsible for the protection of an individual nun and for whose veneration she was responsible, especially on his feast day, is also occasionally noted in the manuscripts. It was even more important to record precisely who had died and their date of death in order to remember them in prayers and masses. The community of both the living and the dead transcended the boundaries of time through memoria, an active form of remembrance which was renewed every year.

3. The Ebstorf World Map

The Ebstorf World Map is an example of the macro- and microcosm of the convent and the positive connotations of enclosure. Moreover, it is more closely connected to nuns than one might think: it is a large, round map that was created in the Benedictine convent of Ebstorf in the 14th century. It was destroyed by a fire in Hanover during World War II, but full-scale reproductions on parchment were made before the war.

Fig. 8 The Ebstorf World Map. 14th century. Facsimile Kloster Ebstorf Ebs Cb 009. ©Kloster Ebstorf.

A World Map from the Middle Ages

Originally, the Ebstorf World Map consisted of 30 sheets of goatskin parchment on which a circle 3.5 metres in diameter was drawn, a so-called ‘wheel map’, as noted in the upper left margin:

The orb (orbis = ring) is named after the roundness (rotunditas) of the circle because it is like a wheel (rota). For the Ocean flows around it in a circle. It is divided into three parts, that is, into Asia, Europe, and Africa. Asia alone covers one half of the earth; Europe and Africa together occupy the other half and are divided by the Mediterranean Sea. Asia takes its name from a woman who ruled the east in ancient times. It is laid out like this on three sides: it is bounded in the east by the rising of the sun; in the south by the ocean; in the west by our (= the Mediterranean) Sea; and in the north by the Maeotian Sea or Marshes and the River Don. Asia includes a multitude of provinces, regions and islands. Europe is named after the daughter of King Agenor; Africa after a descendant of Abraham and Keturah called Afer. There are countries, islands and provinces. You will find a few of their names and their locations on the drawn map if you look more closely.24

In the top right-hand corner, we find an explanation of the multiple uses of such a map, whose origins are traced back to Antiquity:

The term mappa refers to a form. Hence mappa mundi means the form of the world. Which Julius Caesar, having sent legates throughout the expanse of the whole globe, first established. Regions, provinces, islands, cities, coasts, marshes, stretches of ocean, mountains, rivers: he compiled a complete overview of everything on one sheet; which indeed provides not insignificant usefulness to readers, direction to travellers, and the most delightful contemplation of the course of things.25

Unlike most of today’s maps, the Ebstorf map of the world does not have north at the top but east. The upper half forms Asia, the lower-left quarter Europe, and the lower-right quarter Africa. Like the convent, the inhabited world is enclosed twice: geographically by water, the world sea; spiritually by Christ, whose head ‘orients’ the map at the east end and who marks the north-south axis with his hands; his feet peep out at the bottom, illustrating the west end. The two-dimensional wheel shape applies only to the surface of the earth. The fact that the world is a sphere had been known since Antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages, this knowledge is demonstrated by the shape of the globe in Christ’s hand in numerous depictions.

As in the normal arrangement of the T and O map, Jerusalem is positioned at the hub of the wheel, around which literally everything revolves. A square, golden wall with twelve towers encloses the scene of Christ’s resurrection, in which he rises from the grave depicted in the same way as many works of art, for example on the nuns’ choir in Wienhausen. Therefore, the city is at one and the same time the biblical Jerusalem, where Christ was crucified and rose from the dead; the contemporary Jerusalem, to which the pilgrimages and crusades set out; and the heavenly Jerusalem, entry to which is promised to the wise virgins: Jerusalem, the golden, in all its manifold splendour. Here the structures of space and time overlap; long-remembered history is captured in the image as the history of the world and salvation, one into which the nuns integrate themselves because they contribute to the salvation of the world through their way of life. On the map, Adam and Eve are found in the Garden of Eden, right next to the face of Christ; Alexander the Great is depicted on his journey to India in the very top left; and the fabulous creatures of the far south are represented on the right edge, with their feet pointing towards the ocean which surrounds the world. On the lower-left-hand edge of the world, however, at about the level of Christ’s right shin, the nuns of Kloster Ebstorf inscribe themselves into the map.

Ebstorf and Its Surroundings

Fig. 9 Lower Saxony on the Ebstorf World Map. Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis ©Kloster Ebstorf.

On the map, North Germany (Figure 9) consists of a sequence of architectural symbols connected rather than separated by bodies of water: shipment on the rivers Elbe and Ilmenau, then onwards via the North Sea and the Baltic into the trading network of the Hanseatic League, constituted the most important long-distance transport system in northern Germany in the late Middle Ages. The towns of Braunschweig and Lüneburg stand out prominently. Braunschweig, the point of reference for the nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, bears the Guelph lion as a crest, just as it did on the city wall; the lion had stood in the Castle Square26 at Dankwarderode Castle since the reign of Duke Henry the Lion in the 12th century. Lüneburg, the town that contributed to the prosperity of the convents in Lüne, Medingen, Wienhausen, Isenhagen, Walsrode and, of course, Ebstorf with the income from its saltworks, can be recognized from the round object with the inscription luna: the town traced its name back to the Roman moon goddess Luna. Also visible are the bishoprics in the region: Bremen, Verden and Hildesheim, each as towers. The convent of Ebstorf is embedded in this regional structure of duchies, cities and dioceses as a small symbol with three rectangular fields directly below it: these are martyrs’ graves, the presence of which further served to make the convent a holy site.

A World View as a Map

The World Map is a combined narrative of history and space and can be read in several dimensions, inviting both study and wonder. This results in differing densities of development and emphasis for the different regions. Even if, for example, it is possible to plan a concrete itinerary through Franconia with the map points of Nuremberg, Forchheim and Bamberg along the blue veins of the rivers Main and Regnitz, the edges of the world perform a completely different function. The Sciapods, Cyclopes and Blemmyes, or headless creatures, are drawn with vivid detail in the south on the right edge, as are the man-eaters in the Caucasus, as well as Alexander the Great on his journey to India at the outer reaches of Asia on the top left. On the one hand, these fantastic beings constitute imaginative world travel and adventure novels but, on the other, these pictures and texts also invite us to marvel at the diversity of God’s creation, who has ordered everything according to measure and number (Wisdom 11:20).

The nuns who recorded remarkable geographical and historical facts through texts and images on goatskins made more systematic sense of the globe from reports, encyclopedias, and world chronicles than was possible even compared to merchants or pilgrims. They might have been able to travel as far as Mount Ararat but, despite being eyewitnesses to the actual physical surroundings, likely perceived less of the allegorical and historical significance of the place than the nuns. The latter had, in fact, their own understanding of space and time. For example, for them Noah’s Ark was more important than the actual appearance of the place, since the Ark stood for God’s covenant with humanity.

Most of the space in the marginal notes is taken up by exotic animals and their significance: lions, panthers, salamanders, Scitalis snakes, hydra, basilisk. This was not the product of fantasy, but derived from the most important encyclopaedist of the Middle Ages, Isidore of Seville (d. 636): ‘Whoever wants to know more, let him read Isidore’, as a note on the map says. The animals not only broaden the zoological horizon, but are bearers of meaning and, as the annotations show, bear witness not least to the nuns’ knowledge of the bible: the oversized camel is placed next to the gates of Jerusalem in such a way that it simultaneously refers to the biblical verse that says a camel goes more easily through the eye of a needle than a wealthy man into the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 19:24; Mark 10:25; Luke 18:25).

In the fifteenth century Erhart Groß wrote instructions for the Dominican sisters of St Katherine in Nuremberg on how they could travel to Jerusalem in spirit with the help of a map, a compass and the Lord’s Prayer but without leaving their cells. They were to read off the distance on the map using a compass to measure miles and pray one Lord’s Prayer per mile; then, when they had prayed their way to Jerusalem, they would receive the same indulgences as were offered to pilgrims. The Ebstorf map does not have an exact mileage scale by which the distance could be measured, but the viewer can nevertheless seek a spiritual pilgrimage route along which she can pause at several symbols, such as the various saints buried and venerated in the towns along the way.

Even if some maps could be ‘measured’ with dividers and other instruments, unlike modern road maps this material does not become obsolete. In the Ebstorf map the nuns brought the world into their enclosure in a representation that transcended time and retained its validity.