II. Education

© 2024 H. Lähnemann & E. Schlotheuber, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0397.02

The nuns gave the girls entering the convent a demanding education, which lasted several years and included scholarly Latin, theology and music for the choir services; knowledge of economic and organizational matters pertaining to convent administration; as well as handicrafts and the production and decoration of books. Their instruction offered more than mere ‘professional training’. As the example of the Ebstorf World Map in the previous chapter shows, knowledge was always also a carrier of spiritual and intellectual meaning. The allegorical interpretation of their environment and religious tasks was an important part of their education in the convent school and one that created meaning. The individual phases in a nun’s training were intertwined with the various steps involved in entering the convent on the way to becoming a choir nun with a seat and voice in the chapter. They were linked by rites of passage – such as the investiture of, profession by and crowning of the nuns – which both structured and motivated the course of their education.

1. The Convent as School

Educational Trip to the Neighbouring Convent

At the beginning of 1487, the nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster received a visit from the Cistercian convent of Derneburg. The abbess of Derneburg, Sophie von Schulenburg, had fallen ill and travelled to the sisters at the Heilig Kreuz Kloster in order to obtain medicine more easily in the nearby town of Braunschweig. The guest from Derneburg made a deep impression on the Cistercian nuns of Braunschweig. Almost all the nuns, young and old, visited Sophie and enjoyed talking to her, fascinated by her education and wisdom. The learned abbess made such an impression, especially on the younger nuns, that some of them asked their own abbess, Elisabeth Pawel, to be allowed to go to Derneburg for a year to receive better instruction in theology and, above all, Latin.

By the 15th century, Derneburg already had an eventful history behind it. Towards the end of the 14th century, the convent there, originally founded in 1143 as a house of *Augustinian canonesses, had, like so many other monasteries and convents, become impoverished when after the Black Death of 1348 the old farming methods no longer yielded enough, not least due to a lack of labour. The late medieval monastic reform attempted to combat these crises with greater discipline in the nuns’ conduct of their lives and in their theological education, but above all with a new approach to the management of the convent economy. A functioning economy was the prerequisite for the entire convent to be provided for throughout the year, both from its own lands and from other income, and for the women not to be forced to return to their families in the months of famine during the spring or when they were ill. When the Augustinian canon and reformer Johannes Busch wished to introduce a life governed by the rules of the Order as well as strict enclosure in the Derneburg convent, the nuns resisted. Johannes Busch only narrowly escaped an ‘assassination attempt’ when the nuns locked him into their cellar rooms. Now the patience of the Bishop of Hildesheim with the canonesses in Derneburg was at an end. He had the unruly women distributed amongst other convents and in 1442 filled Derneburg with highly educated Cistercian nuns from Wöltingerode, who were faithful to the reforms.

The monastic communities which had accepted reform constituted, as it were, a new religious movement characterized not only by greater discipline, but above all by a new, inward-looking piety (Chapter V). The reformed nuns and monks probably saw themselves as a spiritual elite and established their own networks among themselves. The reform was therefore often associated with an intensified education of the rising generation, improved instruction in Latin and the rebuilding of monastic libraries. On the other hand, the Cistercian nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster had eluded the ‘grasp’ of the monastic reformers and therefore their community stood somewhat apart from the major upheavals, from the discourse on the new forms of religious life and from the wide-ranging literary networks of the reform monasteries. Now, when the abbess of Derneburg, Sophie von Schulenburg came to visit, they were abruptly confronted by the result of a more profound education and an internalized understanding of their spiritual life and it fascinated them. Sophie’s counterpart, the abbess of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster Elisabeth Pawel, saw a great opportunity in the desire of the younger nuns to go to Derneburg in order to become better acquainted with the new way of life. Although concerns were raised in the convent that this might harm the reputation of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, the abbess placed two younger nuns from her convent, one of them named Dorte Damman, in the care of her fellow abbess. This decision remained controversial.

The convent reacted indignantly to the permission granted arbitrarily by the abbess because Elisabeth Pawel had not sought beforehand the advice of the elders and the sisters who held convent offices. This shows the extent to which the abbess’s decision-making powers were constrained by internal power structures and her dependence on gaining acceptance within the convent itself for her decisions to be acted upon and respected. Elisabeth Pawel had good reasons to give her permission without consultation, because she had obviously feared that the sisters in office and the elders would have misgivings if word went round that ‘remedial tutoring’ was needed at the Heilig Kreuz Kloster. The good reputation of a convent was crucial, not least for the economic survival of its community: it determined how much families were inclined to make endowments, to choose the convent as their burial place and to give their daughters to the convent.

Abbess Elisabeth’s unauthorized decision had consequences: there was much ‘grumbling’ in the convent and a split, since some liked her actions while others did not. On the day the two girls left the Heilig Kreuz Kloster for Derneburg, the abbess came to chapter and announced that anyone who continued to grumble or to say anything at all on this topic would, as punishment, have to throw herself onto the floor in front of the others at chapter and do such penance as would fill the others with fear. After all, she said, she had acted for the good of the community. This was the end of the matter for the time being, but a year later, in 1488, after the return of the two sisters, the controversy flared up again.

When the two nuns returned from Derneburg, the abbess convened the elders and counsellors to consult them on how to proceed with the twelve girls who were now old enough to start in the convent school. The unanimous advice of the experienced nuns was that these girls should be divided into two school classes so that they could be better looked after and more intensively taught. As the diarist notes in her displeasure, Abbess Elisabeth Pawel did not act on their advice but placed all the girls in the care of Dorte Damman, who had enjoyed the more intensive instruction at Derneburg and who had suggested to the abbess that, in order to pass on her experience, she would teach all the girls together. Setting a new course was not as easy as she anticipated. Even though the abbess gave Dorte Damman full authority over the girls’ education, the convent *scholastica, the previous teacher, reacted by withdrawing from everything because she could not bear the harshness of the new school regime. As the outcome of the affair demonstrated – or so notes the diarist – it would probably have been better if the girls had been divided into two classes because, presumably in the certain knowledge they were doing things better and right, Dorte Damman and her fellow sister who had accompanied her to Derneburg turned the convent against them through their unusual strictness. The situation deteriorated so badly that in the daily chapter the abbess had yet again to forbid the nuns to reproach the two sisters for their stay in Derneburg. According to the diarist, because of the severe penalties she threatened ‘no one now dared to say anything, either good or bad’.27 The abbess’s attempt to use the education of the next generation as, so to speak, an informal means of somewhat narrowing the gap between the reform monasteries and life in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster had failed.

What, then, was it about the teaching reform in the monasteries? It was very important to the reformers, the bishops and abbots of the *Bursfelde Reform Congregation, that nuns should have sufficient knowledge of Latin for a good understanding of the liturgy and the ability to read the theological reform literature independently. In fact, this was so important to them that they encouraged the women to employ a (male) Latin teacher to take over this task with the convent pupils should the competence available in their own convent be insufficient and they not be able to supply suitable teaching staff from their own ranks – as had been the case at the Heilig Kreuz Kloster.

The results of these educational efforts were impressive. Johannes Busch writes approvingly that in the reformed Augustinian convent of Marienberg near Helmstedt the girls and nuns had, under their teacher Tecla, made such good progress in singing and the scholarly branches of learning that they knew how to interpret Holy Scripture and write letters or reports in a masterly manner. He testifies to his assessment ‘as I have seen and examined it for myself and is evident from the enclosed letters’. Marienberg was also dependent on outside support. Magistra Tecla had come to Marienberg for some time specifically to teach the pupils but was obviously better able to deal with the situation there than Dorte Damman at the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, because the letters demonstrate the enthusiasm of her then-pupils, who obviously missed her badly after she left.

School Lessons in Ebstorf

The Marienberg nuns shared their enthusiasm for their teacher with the convent schoolgirls at Ebstorf. The Ebstorf girls wrote countless essays and texts for school lessons which provide a lively and striking impression of their daily school life. Here the charisma which distinguished the then-magistra in Kloster Ebstorf becomes apparent. It was not only her teaching talent but also her careful, comprehensible explanation of Latin grammar that impressed and enthused the schoolgirls, because suddenly they really understood the contents and meaning of the liturgical chants and Latin prayers:

She construed the whole text of the Rule of Benedict with us word by word, explaining each verse first literally and then according to the sense. Oh, what a pleasure it is to hear and read the sacred readings in the divine worship, the words of the holy gospel from the mouth of the Lord, the words of the holy fathers of both the Old and the New Testaments! For Bernard of Clairvaux rightly claims: ‘If there is paradise on earth, it is either in books or in enclosure.’ By contrast, how tedious and tiresome it is to stand in the choir and read and sing and to understand nothing!28

The records of the convent schoolgirls at Ebstorf tell of (poor) food, baking, dyeing, bathing, the cold, contemplation, mass – and, perhaps most extensively, of school. Alongside the many enthusiastic descriptions, they also reveal the reality of school, which could often be hard, especially in winter. One of the pupils begins her account quite prosaically by mentioning the barely tolerable winter cold. The tremendous frost, she writes, condemned her to idleness, for her hands were frozen stiff and so was the ink, which hardly wanted to turn liquid on the stove. She thought she could still sew gloves from the rest of the woollen fabric her parents had bought for a cloak for her at the market. Although the magistra had taken precautions against snow and rain with wooden shutters in the school, the warming house (calefactory) was now either dark or the rain was coming in. The previous year, she writes, it had been particularly unpleasant in the school because the windows had been broken everywhere. The magistra had then procured new stained-glass windows with beautiful images for the school, which her relatives had donated to the convent at her request.

The ambitious educational goals of the reform movement also had their downsides. The diary-like notes on the last pages of the notebook kept jointly by the schoolgirls convey an idea of everyday school life – and perhaps of the other side of the teenagers’ frenetic desire for knowledge. They read as if this particular convent schoolgirl had given vent to her anger as well as her contempt – or it might be a literary topos used for a composition exercise:

Why do you envy me for learning well? Dogged repetition of reading bears fruit in my knowledge. I just put my abundant natural talent to good use. One who is gifted easily absorbs instruction. You have a poor memory; your shallowness does not allow you truly to devote yourself to literature. You are so slow in declining when you are taught grammar; you are beaten all through school by the cruel blows of the rods. You become a joke to everyone if you do not speak perfectly!29

For all the effort that was put into educating the girls to live a communal convent life characterized by mutual caritas and devotio, it was probably not possible anywhere for things to proceed entirely without tension within the community.

2. The Convent as Cultural and Educational Space

Convent Entry and Convent School

‘Whenever the instruction in learned knowledge decreases in the monastic houses, the impact of religious life will most certainly perish’30 – or so a young nun from Kloster Ebstorf recorded in her notebook at the end of the fifteenth century, presumably picking up on one of the Latin proverbs taught in the convent school. While earlier scholars considered the religious life of women to be intellectually undemanding, we now know that coping with the communal life of women in strict enclosure was very demanding and required the mastery of scholarly Latin for the choir services, the ability to infuse one’s tasks with profound theological meaning and a knowledge of economics for the administration of the convent estates. The understanding of the Latin liturgy, the related insight into one’s own tasks and the inner ordering of convent life were of an importance which was not to be underestimated. The women needed a thorough, intense education, something they could only acquire in the convent or through private lessons within the family, because Latin schools and universities remained closed to them until well into the modern era. Scholarly knowledge thus had to be passed down from generation to generation within the convent. Education in the convent school was, therefore, very attractive to girls and women; and families repeatedly tried to have daughters who were destined for the ‘world’ and marriage educated in the convent school. The nuns, on the other hand, rejected communal lessons with girls who were later to marry because this disturbed the withdrawal from the world by these convent residents and simply made it more difficult to observe strict enclosure.

The problem became clear when the founder of the Cistercian convent of Wienhausen, Duchess Mechthild of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (d. 1261), had it recorded in a document that, in accordance with custom, only girls who later took their vows should find a home in Wienhausen. A temporary admission of pupils into the convent for education or training alone was not to be permitted. Mechthild of Braunschweig-Lüneburg wanted an exception to be made for the daughters of the ducal family as a special privilege of the founding family. It suited both the convents and the families to admit the girls early so that they could attend the convent school at the age of six or seven, as soon as they were of an age to learn. While the convent communities wanted the girls to decide in favour of a religious life as independently as possible, their families, on the other hand, had an interest in an early, binding decision on the future status of their daughters – be it spiritual or secular.

But when and how did one enter the convent? Tilburg Remstede, nine years old, was already one of older girls when she was solemnly admitted to the Benedictine convent of Lüne on 10 January 1482. Katharina Semmelbecker had just turned four when she arrived at Lüne on 1 May 1487, the feast day of the Apostles Philip and James. Here Katharina met her biological sister Elisabeth, who had been living in the convent for a year. The girls’ age and the day of their admission were carefully noted down by the officeholders, as were all further steps and rites associated with each girl’s entry into the convent. The steps leading to admission often took up to ten years and were very important for both the girls and the community as well as for the families. The first was the solemn admission, followed by investiture and, at the earliest a year later, profession. As a rule, this was preceded by graduation from the convent school. Finally, the ‘consecration of virgins’, celebrated as the *crowning of the nuns, formed both the conclusion and in some respects the climax of the initiation rites.

Religious life as an alternative to marriage was highly attractive to women and their families. The nuns enjoyed great prestige in late-medieval society as ‘brides of Christ, the king of kings’; and their spiritual marriage to the heavenly bridegroom was celebrated in the ceremony of the nuns’ coronation. Admission to a convent gave the girls access to a learned education and a career in responsible leadership positions, for they not infrequently presided over communities of sixty to eighty nuns, numerous lay sisters and a large number of domestic servants. The women were responsible for managing both the extensive landholdings belonging to the convent and revenues such as from the salt works. According to wills from Cologne, until the middle of the fourteenth century, when the population declined due to the plague, half of all children were destined for religious life. Even at the turn of the sixteenth century, from the prestigious Nuremberg patrician family of Pirckheimer, six of Willibald Pirckheimer’s sisters and three of his five daughters entered a convent (see Chapter IV). Only Willibald’s sister Juliane entered into marriage. In the late Middle Ages, women’s communities could certainly pick and choose their future convent members. The reform statutes for the Benedictine convent of Lüne from the end of the fifteenth century stipulated that if parents asked that a child be admitted to a convent, their repeated request should be granted, provided the status and reputation of the girl and her family had been carefully scrutinized. If the provost and convent agreed to her admission, at least six months were to elapse before her solemn induction (introductio). On the first presentation, the provost was to ask the child herself whether she wished to enter and remain in the convent of her own free will. She was then given a black tunic, a long veil and, as further head-covering, most especially a ‘nun’s crown’, which consisted of two strips of white cloth, each a finger wide, crossed over the top of the head (see Figure 12). The new clothes were but symbolic references to the girl’s destination for a religious life, because she had not yet entered the spiritual estate.

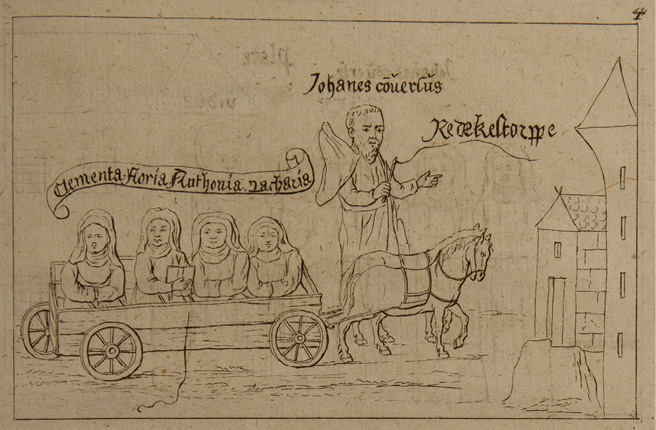

Since the dowry for a wedding befitting a girl’s status was very expensive, parents tried to limit girls’ permission to marry unless the marriage contributed to the success of their family politics. The relevant arrangements for the next generation were usually made by noble and patrician circles at the end of pueritia, when their children were six or seven years old – namely, before they were handed over to relatives or friends in neighbouring towns, or to other courts, or to monasteries or convents for education. At twelve, girls came of age and could enter into marriage without the consent of their parents. Even the staunch monastic reformers of the fifteenth century took the needs of lay society into consideration: the reform statutes of the Benedictine convent of Lüne set the minimum age for admission to the convent at five and the maximum age at twelve. The nuns were generally true to the rules of their statutes. In some cases, however, they also accepted younger girls. In the following case, a family relationship to Provost Johannes Lorber (1506–1529) may be assumed: on 25 July 1518 ‘Sister Cecilia Lorber came to this convent in her fourth year, on the day of the blessed virgin Gertrude. We fetched her in a little cart, and she remained here with us’.31 The panel painting of lay brother Johannes transporting four nuns from Kloster Wolmirstedt to the newly founded convent in Old Medingen in a kind of hand-drawn wagon might reflect such practice.32

Fig. 10 History of Kloster Medingen, Panel 4. Lyßmann (1772) after paintings from 1499. Repro: Christine Greif.

The girls themselves could only take a valid vow of profession when they reached the age of majority. Then, however – as an alternative, one which many fathers and mothers may well not have had in mind – they could also enter into marriage against the will of their parents. If their family wished to bind the girls to a religious life prior to this, church law provided two possibilities for entering a convent while still a minor: *oblation and ‘tacit profession’. In the case of oblation, the parents made a legally binding vow on behalf of their underage child by offering him or her to the altar of the spiritual community in question – in other words, by ‘sacrificing’ him or her. Through the parents’ vow of oblation the child had entered the clerical state, whereby this decision did not, in principle, require any further confirmation by the adolescent. The ‘tacit profession’ usually took the form of the handing over of the *habit and is therefore called an ‘investiture’ in the sources (from the Latin vestis: robe; clothes). Investiture also corresponded to entry into the clerical state – albeit with the reservation that this had to be confirmed later, at the age of majority. Phrases such as ‘virgins consecrated to God’ (virgines deo sacratae) are not, therefore, mere vague descriptions but clear legal terms which denote the completed passage of the girl concerned into the spiritual state of a choir nun.

While oblation was quite common in the Cistercian convent of Wienhausen, after the monastic reform of the fifteenth century the Benedictine nuns in Lüne rejected this path to entry and preferred investiture. In preparation for the investiture ceremony, the provost gave an address to the girls in the chapter about the strictness of the rule, the ‘perpetual enclosure’, the renunciation of private property, the contempt for everything worldly, the complete separation from – the ‘forgetting’ of – parents, and the girls’ relinquishment of their own will. The investiture itself was integrated into the celebration of a mass, during which the girls’ parents and relatives were permitted to enter the nuns’ choir. While the families and the girls sat in the middle of the nuns’ choir, the convent followed the ceremony from the choir stalls. The nuns’ crowns which the girls had worn since their admission were now taken from them and laid in front of the figure of the convent patron, St Bartholomew, where they were kept until the coronation of the nuns.

Mechthild von Eltzen, who had come to Lüne in 1506 at the age of six, celebrated her investiture just two years later. The prioress of Lüne, Mechthild Wilde, led the girl to the steps of the altar, where the provost received her. He took off her nun’s crown (vitta) and the upper garment (toga) while he spoke of stripping off the former existence; and then he consecrated the novice’s habit. With the verse ‘the Lord robes you’ (induat te dominus), based on Ephesians 4:24, the provost dressed her again in the habit and cincture. Finally, he took up a cloth, covered the novice’s head with it and cut off her hair. It was hair like this, braided into plaits, that was discovered by the scholars of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster near Braunschweig when they searched the empty convent for usable objects during the nuns’ exile (Chapter I.1). Afterwards everyone enjoyed a celebratory meal together, and Mechthild and the other girls received smaller or larger gifts. To mark the occasion, the mother of Adelheid Stüver gave her daughter a silver statue of St Aldegunde, on whose feast day she had been born; another mother gave her daughter a silver figure of St Clare; others gave silver spoons, a wine jug or money. In Lüne, the ceremonial investiture within the framework of mass marked, as a ‘spiritual wedding’, the transition to the religious estate and thus the final farewell to parents and to the life of the world in general.

Leaving the Convent School and Profession

The lessons at the convent school were entirely geared to the liturgical tasks and demands of life in strict enclosure. At age five to seven, the time spent in school was quite long and demanding by the standards of the time. Magdalena Schneverding came to Lüne in 1515 at the age of seven and was admitted to the convent school a year later, invested in 1520 at the age of twelve and left the school in 1523. At this point she had, therefore, already been living in Lüne for eight years. The ceremonial leaving of the convent school then took place at chapter in the presence of the convent and the provost. He officially released the girls ‘from the scholastic yoke’ (a iugo scolasticali). The education of the girls in the convent school was of the utmost importance to the convent. Here the course was set for the attitude and skills of the rising generation. In a typical mixture of Low German and Latin, a Cistercian nun from Wöltingerode noted down a programmatic poem below the text on the first page of a book on martyrs; the third stanza runs: ‘The study of the arts should be a prelude to salvation: indeed, let us understand scripture! Without it, monastic – alas! – devotion remains in idleness: not to read is evilly done.’

Salutis ad preludium / sit artis nobis studium: / wolan, die scryft vorstan!

quo sine stat in ocio / claustralis – heu! – devocio: / nicht lesen is ovel dan!33

The punchline of the stanza is provided by the Low German phrases that follow each Latin rhyming couplet: scryft (scripture) can be understood as literature in general but applies especially to the Holy Scriptures. Just as at university, the study of philosophy in the form of the seven liberal arts (artes) has the purpose of preparing students for the higher faculties, including that of theology; a deeper understanding of the basic sciences is also necessary for nuns to live convent life appropriately. Otherwise, the greatest sin of monastic life threatens: idleness.

The Nun’s Coronation

The nun’s coronation, known as the ‘consecration of a virgin’ (consecratio virginis), formed the climax and conclusion of the nuns’ admission ceremonies. Nuns’ crowns were widespread in late medieval northern German convents, but in southern Germany they can only be found in isolated cases. The essential elements in the ritual crowning of a nun were obviously derived from the secular marriage ceremony of late Antiquity. Traditionally, only the bishop enjoyed the right to crown nuns because their coronation signified the official recognition of their virginity by the church. The consecrated nun’s crown anticipated their coronation in heaven, to which the virgins were entitled after the last judgement as a reward for their virginity, this being understood as a bloodless martyrdom. The nuns’ crowns consisted of white strips of material laid over the head in a cross shape. Crosses of red silk were sewn onto the front and, more frequently, onto all four sides, as well as on the top of the crown. This is clearly visible in the depiction of music lessons from Kloster Ebstorf (Figure 27), in which the organ player, the two seated women in the garden and (seen here in the detail) the nun teaching the others to read music wear the ribbons with the red crosses over their veils.

Fig. 11 Benedictine nun with nun’s crown (detail from Figure 27).

Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis.

The transmission of the nun’s crown shown in the next illustration is a stroke of good fortune. It was only purchased from private ownership in 2000 by the Abegg Foundation on the Riggisberg near Bern. Until then medieval nuns’ crowns had only been known from written sources or from illustrations. It consists of precious white silk ribbons with gold borders laid over the head in the shape of a cross, with five medallions where the ribbons cross: on the crown a red square with five golden dots; on the forehead a lamb of God (agnus dei); on the sides a cherub and an angel with a lily sceptre; and at the back of the head the Old Testament king David in an attitude of worship. At the end of the fourteenth century, the light silk bands were sewn for stabilisation onto a blue silk cap, to which the red trimming also belongs. The embroidery and especially the medallions on the nun’s crown correspond to the descriptions of the famous nuns’ crowns from the Rupertsberg, which Hildegard of Bingen describes in the letter to Tengswich of Andernach (d. 1152/1153) and in her visionary work Scivias (‘Know the Ways’) and which the nuns there wore over their loose hair.

Fig. 12 Nun’s crown from the twelfth century. ©Abegg Foundation, inv. no. 5257.

In her vision, Hildegard sees some of the nuns adorned with a golden circlet, displaying on the forehead a lamb, on the right a cherubim, on the left the figure of an angel, on the crown of the head the image (similitudo) of the Holy Trinity and a human being. This nun’s crown comes very close to that description. In Hildegard’s vision, it is no longer the tangible object, but already the heavenly crown which Christ placed on the head of his brides, the virgins, in their eternal life, in parallel to the crowning of Mary as the first of the virgins.

In Lüne, as in Ebstorf, the girls wore somewhat simpler nuns’ crowns, which instead of medallions were decorated with red crosses as symbols of the stigmata of Christ. The unconsecrated nuns’ crowns were initially given to the girls without the red silk crosses. Later, the abbess presented them with the crosses as gifts on special occasions. They were sewn onto the white fabric strips retrospectively. During the coronation of the nuns, the bishop consecrated the white strips of cloth, which had been deposited with the convent patron St Bartholomew at the time of their investiture as a sign of their promise of chastity; and then he placed them on the girls’ heads in a solemn ceremony. The liturgical configuration of the celebration was based on the story of the wise and foolish virgins (Matthew 25:1–10). This biblical parable is about the return of Christ, the hour of which is unknown. Ten virgins – all personifications of the bride – go to meet the bridegroom by taking their lamps and setting out. The five foolish ones only have their lamps with them; the five wise ones also have oil. In the night, only the wise ones find their way to the bridegroom. Future nuns were to emulate these five. In the ceremony, this was staged as follows: with lighted candles in their hands and their heads uncovered, the candidates approached the bishop through the nuns’ choir. There they received the crowns, which signified their final arrival and privileged position in the spiritual world.

3. The Heiningen Philosophy Tapestry

The nuns, especially in northern Germany, were well acquainted with Latin and with the learning of their time. As a rule, therefore, they were able to explore theological, philosophical and many other topics independently. This meant they belonged to a group of literate people which even in the late Middle Ages was still small. How, then, did the nuns themselves perceive the universe of education and where did they locate themselves within it?

A Demonstration of Education

The Philosophy Tapestry from the Augustinian convent of Heiningen is a very special means of demonstrating education: in 1516, the nuns in Heiningen produced a monumental tapestry, the visual rendition of a universe of knowledge into which the community – all the nuns, the lay sisters and the convent pupils – inscribed themselves.

Fig. 13 Heiningen Philosophy Tapestry. ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, Accession No. 289–1876.

The tapestry measures almost five by five meters, everything revolving around one personification: Lady Philosophy. It must have taken many years to create such a monumental tapestry, from its design to its realization and the detailed embroidery of the figures with their speech scrolls.

Even though the tapestry reveals a great love of detail and the numerous speech scrolls require detailed studying, the overall structure is clearly recognizable. Philosophia, crowned, as imagined in Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy, is enthroned in the centre; in her all knowledge is gathered. Two circles enclose the celestial sphere of knowledge, the source of which is Philosophy in the centre. While the sciences, which explain the immaterial forces at work in the cosmos and on earth, are framed by trefoil arches resting on pillars, this heavenly sphere of divine order is separated from human knowledge by a square frame. Earth-bound education rests on four authorities as the foundation of knowledge: Ovid, Boethius, Horace, and Aristotle. These highly respected classical authors were regarded as the origin of the academic disciplines. The first large display of Humanism north of the Alps happened about 100 years earlier, when a large group of Italian humanists participated at the Council of Constance (1414–1418), schooled as they were in the texts of Antiquity. Their education and culture deeply impressed the Holy Roman Empire gathered at Lake Constance. Renaissance culture had also gained acceptance in the convents of northern Germany. Eloquent and well-read, the nuns quoted Ovid: ‘One should cultivate the arts in these times when faith stands or falls with fate’34 – a far-sighted quotation in view of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses published only a few years later in 1517. Despite their enclosure, the nuns in Heiningen were apparently well acquainted with the fact that social change was on the horizon. From Aristotle, they selected a very pertinent admonition for a community tackling such a major undertaking as this tapestry together: ‘Bad is the companion who hinders the common task’.35

The Tapestry Speaks

The Philosophy Tapestry is not a purely abstract or prefabricated view of the universe of medieval knowledge: rather, the women (and men) of Heiningen have integrated themselves into it. On the edges, in the outermost square frame, an inscription which surrounds the entire tapestry names Prioress Elisabeth Terwins as the driving force. The tapestry itself ‘speaks’: ‘In 1506, our honourable Domina Elizabeth Terwins had me made by the professed nuns consecrated to God’, and then lists in order of seniority the sub-prioress Margaret Hornborch, the bursar Anna Lunemans, the other officeholders and the total of thirty-six choir nuns, six lay sisters and four novices in the convent.36 The provost and the priests are also listed. Reference is made to the founding of Heiningen and its reform, which, as a second act of foundation, had made possible the blossoming of the convent at the turn of the fifteenth century. At the same time, this a snapshot of the convent of Heiningen with all its members. After a period of decline, they had all worked together to breathe new life into the convent through the reforms in the fifteenth century. To achieve this, the nuns and the entire community of Heiningen inscribed themselves into the universe of education and the long traditions of learned knowledge.

The Academic Disciplines and Christian Ethics

The intellectual roots of the academic disciplines and the educational universe lie in philosophy as the undisputed ‘art of the arts’ (ars artium). The speech scroll above Lady Philosophy declares that she encompasses everything a human being can know and that through her it is possible arrive at theology, the highest academic discipline – if knowledge is augmented by the grace of cognition. Following the systematics of Plato and Aristotle, the knowledge encompassed by philosophy is divided between five medallions, which are identified by female personifications displaying characteristic objects and epithets: ‘Physics’ (natural sciences) with a cylindrical medicine tin; ‘Mechanics’ (applied sciences) with a protractor; and ‘Logic’ (explained as ‘knowledge for disputations’) with a book. In addition, we find ‘Practice’ (moral philosophy and politics); and ‘Theory’ (speculative philosophy and searching for truth), the latter identified by a mirror.

Fig. 14 Philosophy enthroned and surrounded by personifications (detail from Figure 13).

In the second large ring, we then find the Seven Liberal Arts, the artes liberales, personified by male and female figures and starting with the basics of Grammar, Rhetoric and Dialectic – or the Trivium, a term related to ‘trivial’, i.e. basic meaning. Building on this foundation, the Quadrivium was taught: Music, Geometry, Astronomy and Arithmetic. The Liberal Arts do not stand here alone and separate but are accompanied by and paired with the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Here the individual Arts are framed by rhymed mnemonic verses, such as were presumably taught in school. The seven gifts display quotations from the Old Testament on their speech scrolls, the contents of which always refer to the particular discipline of the Liberal Arts next to which they stand. Hence the academic disciplines, which, as the nuns knew only too well, can be used for both good and ill, are each restrained by a principle of Christian ethics in this blueprint for an ordered universe of education. Thus, Grammar is said to teach the art of writing and the manner of speaking;37 and Wisdom is placed next to her in the form of Solomon, who warns us to be modest, emphasizing that all wisdom comes from God and is eternal in him. Grammar was the key qualification for all those educated in the convent, who were expected to converse with one another in Latin and also to compose their works in this language.

From 1516, the tapestry was kept in Kloster Heiningen and survived all reforms, the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation until the convent’s dissolution in 1851. Whoever wanted to decipher the message had to circumnavigate the tapestry, because the figures and texts are arranged as on the axes of a wheel. Like the Wienhausen Tristan Tapestry (Figure 17), the textile was probably laid out in the convent for special visitors on feast days. Due to its monumental size, only the convent church or the nuns’ choir could conceivably have been used for this purpose. The Philosophy Tapestry must have meant a great deal to the community because it was kept at Heiningen for many centuries. In 1876, it was purchased for the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, where the intention was to gather exemplary arts and crafts from all over Europe to act as models for budding craftsmen. Pieces like this one influenced the Arts and Crafts Movement with the medieval revivalism of William Morris and other artists; the memoria of the Heiningen nuns, of their craftsmanship and their names has thus continued under different auspices into the present.