III. Nuns, Family, and Community

© 2024 H. Lähnemann & E. Schlotheuber, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0397.03

Convent and world were interconnected in many different ways. When they entered the convent, the girls and women also made the legal transition from their own family group to their new family, the community of choir nuns. Whereas their father or a male relative had previously been their guardian, this duty was now assumed by the convent provost, who as the ‘bride’s best man’ represented the nuns’ bridegroom, namely Christ. The families remained connected to the community of nuns in many different ways, often celebrating high feast days in the convent and maintaining their family tombs there. As a highly respected alternative to marriage, the convent also represented a special space in which to reflect on spiritual and secular models for the conduct of one’s life. Likewise, role models such as Elisabeth of Thuringia could be preserved, negotiated and imbued with meaning: Elisabeth had not entered a convent but had, in active service to others, dedicated herself to nursing the sick. In the Middle Ages, families were understood as a community of their members living in both world and convent and as a cross-generational network of the living and the dead, equally commemorated by the nuns in their prayers.

1. Life History and Family Influence

Family ties between the Heilig Kreuz Kloster and Braunschweig were close. This can be seen, for example, in the family van dem Kerkhove. Through the generations, many women from this family of tailors, an old patrician family whose members had long served on the town council, lived in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster. The men of the family officiated as *procurators, secular advocates for the community of women, on Braunschweig town council; and the van dem Kerkhove had a right to a place for their daughters in the convent.

The Limping Girl

In 1483, the Braunschweig citizen Margarete van dem Kerkhove, a friend of the convent, came to the convent and asked the community to take in her daughter, who limped. Yet she did not wish the daughter to be accepted into the convent as a future nun, but initially only that she could live there as a guest with the other girls. The daughter was seven years old when she came to the Cistercian nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster on the Rennelberg. She lived with the nuns without being bound by vows of any kind, as the diarist points out. She wore a white habit and participated in the Liturgy of the Hours as well as interceding for the deceased, an obligation to which the convent was bound. Sometimes she studied in the school with the future choir nuns; on other days she worked alongside the lay sisters. She did not wear a *scapular, the dark upper garment of the habit, over her shoulders, nor did she follow the rule of the order – she remained a guest. Her uncertain status stemmed mainly from the fact that her family did not wish to see their daughter admitted as a lay sister, and the convent would not agree to her admittance as a nun because of her physical ailment. Being a nun was a question of status.

Almost seven years passed before unfortunate circumstances meant the daughter was almost the only one left in her family. Both parents had died in the meantime, as had all her brothers and sisters. In this situation, the girl’s relatives advised her to ask the abbess to grant her permission to return to the world. Mechthild von Vechelde, abbess of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, gave consent on one condition: namely, that the girl, who had lived with the nuns for so long and had been educated for this life, would continue to remain chaste and would not marry. With that, the abbess released the familiar guest, having first removed the robe she had worn in the convent. Of course, the abbess’s authority ended at the convent walls. Back in the world, the girl did not feel bound by any promise. She married in the very same year and gave birth to a son, thereby ensuring the continuity of the family. The diarist does not comment on this breaking of her promise but concludes the narrative with the terse words: ‘Let us not talk about that in detail now, but return to our own affairs’.38

The Reception Party for the Weferlingen Daughters

The convent performed an important function for the families in several respects. For the wives and daughters in particular, it served as a special space and shelter which provided an alternative to marriage and, not least, access to scholarly knowledge. Through this mutual dependence, convent and lay world were bound together by close relationships, which became critical when questions arose about the admission of future members of the convent. On one St Anthony’s Day, 17 January 1496, the wife of the knight Ulrich von Weferlingen came to the convent, bringing with her two girls named Katharina and Elisabeth. The noble family of Weferlingen had probably been connected to the convent since its foundation and maintained their family tomb there. The convent accepted the two girls into its community in accordance with an earlier agreement and their father’s will, on condition that they would agree to enter the convent of their own free will after a probationary period.

For the convent, it was a balancing act. For the nobility and the patriciate in particular, their daughters’ entry into the convent was an important instrument in their family strategy. Especially if the families had the right to a *prebend, the financial outlay was much lower than a marriage in keeping with their status, amounting to barely a tenth of the dowry. Because the family estate became the property of the husband’s family on a daughter’s marriage and served as widow’s dower to provide for her after the husband’s death, families could prevent the fragmentation of their property by having one or more daughters enter a convent. For the convent community, on the other hand, it was crucial that future nuns had made their decision in favour of a spiritual life as independently as possible and viewed the religious way of life positively so that community life was not damaged by their inner reluctance.

When the probationary year of Katharina and Elisabeth von Weferlingen had passed, the elder of the two sisters refused to receive the clerical garments. ‘We let her go free’, the diarist notes, after the abbess had stripped her of the white robe, the promise to enter a religious life.39 The younger girl, on the other hand, was keen to stay in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster and decided to become a nun. In the meantime, her mother, the wife of Ulrich von Weferlingen, had become a widow. In addition to the two older girls who had already spent a year in the convent, she had three other younger daughters, the youngest of whom, Fia, had taken it upon herself to take up the place left vacant by the departure of her sister Katharina. She wished to pray for their father and, as far as she was able, to come to the aid of his soul, which was presumed to be in purgatory. According to the diarist, Fia convinced her mother through ‘fervent pleading’,40 with the result that the latter brought the four-year-old to the convent. The convent accepted Fia. In the same year the oblation of both daughters was celebrated as a spiritual wedding, at which the mother took perpetual vows on behalf of the children, who were still minors. These vows signified their passage into the status of *religious. The major celebration was set for 16 June 1499, St Vitus’s Day, and the widow of Ulrich von Weferlingen invited friends and relatives of the family to the convent to celebrate her daughters’ wedding day together.

Unfortunately, many of the invited guests obviously made their excuses because the diarist mentions with regret that this meant they had gone to great length to put out a ‘great spread’ of everything ‘because of the nobles who were expected, but it was all in vain since only very few came’.41 The convent had wanted to prove to the family that it was accommodation worthy of their status. The family of the Weferlingen daughters as the brides, on the other hand, had to pay for the festivities and the widow spared no effort or expense. Four courses of meat alone were served; there was venison, chicken, and beef for guests to fill their bellies. The convent ‘accepted it gratefully on the day, but afterwards I heard several times that almost everyone was displeased by the overabundance’, the diarist notes critically as a warning for future similar events.42

The Convent Throws Out the Provost

The most important office, the link between the convent and lay society, was that of the provost. As the highest-ranking clergyman in the convent, he was responsible for the supreme supervision of its religious life alongside the abbess. His main task was to ensure the nuns were provided for through the estates and to regulate all secular affairs for the nuns, including maintenance of the convent buildings.

In 1488 Heinrich Karstens, who admittedly still owned his own farm near St Cyriacus Abbey in Braunschweig, was provost and at the same time *canon in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster. The abbess of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, Elisabeth Pawel, was not very satisfied with him. Heinrich Karstens was hardly ever present, but constantly spent his time on the Cyriakusberg, where he was having a new house built for himself. The absence of the provost had a severe impact on convent life. Sometimes the women did not have enough bread for the convent; sometimes there was a lack of wood, or of coal and in general of all the necessities of life: ‘Whatever the provost was required to provide for us from our own estates could not be obtained without anger and harsh words from the abbess’.43 Quite obviously, the nuns suspected that the provost was appropriating their property for his own building project. Worse still, he had turned almost the entire familia, all the secular servants who lived and worked on the neighbouring farm, against the nuns. The abbess found herself in a difficult position. Normally she would have discussed this abuse of office with the procurators, an office usually held by high-ranking Braunschweig citizens, who were responsible for representing the affairs of the nuns of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster on the town council. During these years this office was held by the two councillors Albrecht von Vechelde and Bodo Glümer. Yet Heinrich Karstens seemed to have been a respected, influential person in Braunschweig: the procurators declined to intervene because they did not want to annoy him. They were probably afraid of endangering their own affairs, or so the nuns heard from third parties. Nothing could be done, and the women had to put up with the damage caused.

Eventually, however, it all became too much for the abbess, and she resorted to a very effective expedient, one which illustrates the close lines of communication between the convent and the world. During the daily chapter meeting, the abbess gave permission to the whole congregation to complain to their relatives and friends about the provost and to ask them for advice on what could be done. She herself enquired from the good friends of the convent how the community could obtain different governance, that is, a new provost. They advised her to summon to the convent some of the twenty-four *guild masters, the political representatives of the guilds, and explain the situation. The abbess followed their advice, and the guild masters promised to support the community’s request.

The effect was immense, but its consequences were not without problems for the convent. The twenty-four guild masters decided not only to dismiss the provost Heinrich Karstens, but also to remove the two procurators, Albrecht von Vechelde and Bodo Glümer, from office. They appointed two new councillors in their stead, namely Jakob Rose and Konrad Scheppenstede. Of course, Albrecht von Vechelde and Bodo Glümer were profoundly angered by this turn of events. The abbess tried to reconcile them with the convent by all means possible, sending them gifts and asking them to remain loyal friends of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, but all in vain: they remained angry. Moreover, the deposed provost took revenge in his own way and took whatever he could with him from the provostry.

2. The Family and the Convent Community

As the example of the dispute with the provost and the lobbying of the Braunschweig families demonstrate, the convents were integrated into a tight network of families bound together by ties of friendship. Many of these families remained connected to a particular convent for generations, and their closeness can be traced back to its founding days. Both sides, the families and the nuns, benefited from this. The convents offered both men and women special access to salvation, but also to careers as religious – women as abbesses or office holders; men as provosts or parish priests in the parish churches under the supervision of the convent, for example. Through these networks the communities of nuns often exerted their influence very effectively.

The Families of Origin: Nobility and Patriciate

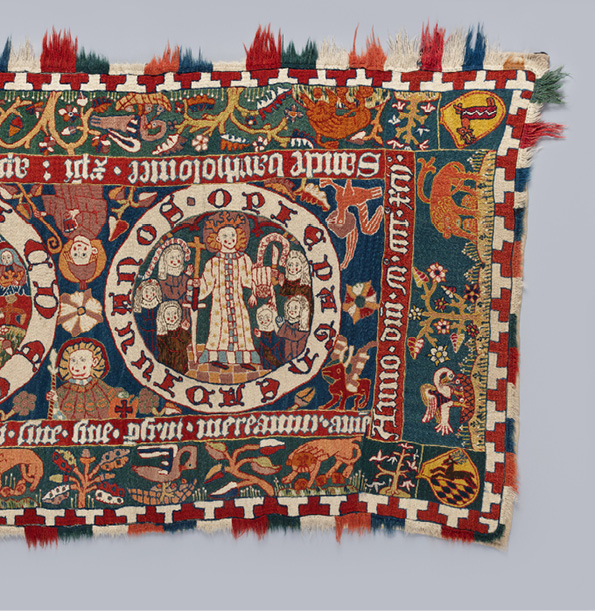

In principle, anyone and everyone could choose a religious life and enter monastic houses, but in practice the options for women in particular were predetermined by the status of the family from which they were descended. The civic or episcopal Latin schools were open to sons, who could, therefore, often make the decision about their way of life, whether spiritual or secular, much later, namely in adulthood. Then they could also enter a religious community against their parents’ will and choose between a whole spectrum of religious ways of life that were more or less open to the world. In order to enter a community of Benedictines or Cistercians, the old monastic orders, daughters needed the support of their families, who contributed to their keep by means of a dowry. As the example of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster shows, the girls came from families who were in a position to make this financial outlay and who had long had ties to the convent. These were usually noble families from the surrounding area or members of the urban patriciate. Their coats of arms can be found in the objects handed down in the convents to this day. For example, the coat of arms of the von Bodendike family – a leaping brown stag with red antlers and a jagged white chevron on its coat – is set on a keystone in the cloisters in Kloster Lüne and is also immortalized on several tapestries, each of which was produced around 1500 during the period in office of Prioress Sophia von Bodendike, including the Bartholomäuslaken, a wall hanging showing the legend of St Bartholomew, the convent’s patron saint. Around the first eight of the nine scenes there are short captions explaining the action. In the last roundel, the nuns are depicted adoring the saint who wears over his arm his flayed skin but is smiling with a heavenly crown on his head. The caption gives a short prayer instead ‘O kind patron, help us’,44 with a further prayer line written as speech bubbles coming from the two nuns kneeling at the top: ‘O glorious patron, blessed Bartholomew!’45 Around the whole tapestry runs a longer rhymed prayer in the voice of the whole convent, imploring Bartholemew as ‘God’s friend’ to assist the nuns in joining him in the ‘hall of heaven’:

Saint Bartholomew, apostle of Christ, outstanding teacher of the Indians, incline your ear to our cries, that lifted up towards the Lord by your help, we may merit to become heaven’s citizens like you. Intercede for us to the Lord, glorious friend of God, that by his grace granting, for the memory of our patron, we may behold you, God, face-to-face in glory, and live eternally. Holy Bartholomew, patron, teacher, good apostle of God, be our aid in the hour of death, place us in the hall of heaven, so that we may merit to enjoy the face of God without end, amen. In the year of our Lord 1492.46

Fig. 15 Bartholomew tapestry of 1492. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Lüne.

While family members were allowed to enter the convent on special feast days, the nuns’ enclosure meant they were not permitted to leave the convent to attend family celebrations or to care for sick relatives. For that reason, they had to rely on letters for communication. Among the letters of the Benedictine nuns in Kloster Lüne are quite a number congratulating their siblings on their weddings; in them the nuns regret that they cannot attend the celebration themselves because of their secluded way of life but promise to send holy guests with the gift of good wishes instead. Anna von Bülow thus congratulates her brother Vicke von Bülow on his second marriage and explains the spiritual significance of the celebration: Christ, her bridegroom, and Mary, her mother-in-law, would be present at the wedding just as they were in Cana when Jesus was instructed by his mother to turn water into wine.

The cultivation of good relations also included sending small gifts, although the nuns themselves owned no property and were therefore dependent on the work of their own hands in this respect. For example, the three sisters Elisabeth, Mette (Mechthild), and Tibbeke (Tiburg) Elebeke, living as nuns in Kloster Medingen, wrote a Low German prayer book for their sister Anna, who had married the mayor of Lüneburg, Heinrich von Töbing. For the volume they translated texts from their own Latin prayer books and adapted them to the life of their secular sister. Another nun from Kloster Lüne was apparently worried about her brother, to whom she wrote an admonition to study hard as well as good wishes for his recovery, because she had heard from their mother that he was ill. She said that he should commit himself to his talent for study, because now it was up to him what he made of it: after good beginnings, Judas had ended up a traitor; Saul, on the other hand, had turned into Paul. Although the brother had obviously studied and had certainly learnt Latin, the siblings wrote to each other in Low German – perhaps because of family ties.

The Monastic Community: Abbess, Prioress, Nuns, Lay Sisters, Provost, and Scholars

Medieval convents were large and often very influential spiritual institutions. As we have already seen, it was by no means only nuns who lived in them: the often extensive buildings housed very different social groups, both men and women.

A monastic community was always structured hierarchically. The abbess led the convent and represented it externally, while a number of further office-holding nuns assumed functions in its internal organization, such as prioress, precentrix (*cantrix), cellar mistress (*celleraria) or schoolmistress (magistra, scholastica) and formed a kind of ‘inner council’. This council assisted the abbess in major decisions, they signed important documents together and led the way in ceremonies such as processions. The elders (seniores) in a convent also performed an advisory role, whereby their ‘age’ was measured according to the date when they entered the convent or took their vows. The communities could vary greatly in size, from a mere dozen to ten times that number of women: *houses of secular canonesses usually comprised twelve to fifteen women, convents an average of sixty to eighty women, as well as the novices and girls who had not yet professed but were already living in the convent.

Since the women lived in strict enclosure, they were assisted by lay sisters who undertook the necessary work outside the enclosure and ran errands for them. While the choir nuns, through their spiritual marriage to Christ, occupied a high rank in medieval society and were a ‘good match’ for Christ as ‘son of the highest king’, the lay sisters represented a different social order and usually came from less affluent families, such as the urban middle class. This is also the reason why, in the case of the girl with a limp, her patrician family resisted giving her to the convent as a lay sister rather than a choir sister.

Lay sisters typically entered the convent at an age when they were fit for work, took only simple vows and were cared for in the convent throughout their lives. They did not go through the convent school, so they did not learn Latin and had reduced prayer obligations so that their work did not suffer. Yet they learnt to some extent to read and write in the vernacular, as is evident from the letters and devotional manuscripts they wrote for themselves. They were not bound by any fixed rules of enclosure, and enjoyed greater freedom of movement, albeit under some control.

A rule from the 1470s for the lay brothers and sisters in Kloster Medingen stipulates that they were not to use their right to come and go more freely to smuggle strangers into the convent or, conversely, to go into town to visit relatives without express permission. They were to dress plainly and not, for example, wear two-tone red and green, tight-fitting garments with silver buttons – a prohibition that, like so many others, provides us with an insight into what was fashionable at the time. Above all, however, they were forbidden, under threat of excommunication, to write their wills without the knowledge of the provost – too great was the fear that property would be lost for the convent.

Maids and servants such as day labourers came from the same social group as those doing similar jobs in the town or for the nobility. They looked after the mills, brewery, fishponds, farms, vineyards, and the rest of the convent property. Sometimes they came to the convent together with members of a family whom they had also served in a secular capacity, even though the convent rule forbade *religious to be assisted by personal servants. The prebendaries found in many convents also represented an important group – men and women who decided, mostly towards the end of their lives, to live with a religious community that would then take care of them – a provision for their retirement. It was not uncommon for them to possess special skills, have detailed knowledge of sewing, be learned lawyers or trained craftsmen which was very useful to the convent. They transferred their inheritance to the convent when they entered, took on many smaller and larger tasks for the community, such as running errands, and were provided with all the necessities of life in return.

On the whole, a monastic community thus followed the model of a family, starting with the ‘head of house’ as the mother of the entire community. This is clear from the very title of the office. The term ‘abbess’ has a long journey through many languages behind it, beginning in the bible itself. Its basis is the intimate Aramaic address for ‘Father’, abba, which Jesus uses in the Lord’s Prayer. The abbess represented and took responsibility for the community to the outside world and for this reason was also allowed to leave the enclosure. The reputation and prosperity of the convent often depended on her family connections: for example, when in case of conflict it became necessary to assert the interests of the convent in lay society. She also had the power to punish the nuns and the duty of supervising discipline in the convent. The office of abbess was extremely demanding. In the Lüne letters, obituaries praise the head of house (which in convents sometimes was the prioress) as ‘sweet mother and loyal shepherdess’ whose loss is mourned by the nuns like ‘lost sheep’.47 The inscription on the last panel from the cycle in the house of the abbess in Kloster Medingen praises the work of Margarete Puffen, who had been the first prioress during the monastic reforms and who had successfully managed to be promoted to the higher-status form of abbess in 1494. It does so in Latin verse and from the point of view of the convent:

She taught us, the handmaiden of Christ, with all gentleness and piety in the holy reform and observance and abolished fully the vice of personal property. She scattered the flowers of true religion and reform and rejected all error. All the deeds of her predecessors she gilded with her own deeds; and like an angel of the Lord she walked among us and never tired of working for us day and night.48

Men were also necessary in this community: canon law forbade women not only to speak publicly on issues of dogma, but also to preach and to administer the sacraments. As shown by the example of the nuns in their Braunschweig exile, they organized the Liturgy of the Hours and the chapter meetings themselves, but in several areas they came up against the limits imposed by canon law. For the celebration of mass and the sacraments, the women needed priests. These could be secular clergy, the provost or even monks who took over the spiritual ministry known as ‘care of the souls’ (cura animarum). The small group of clerics who assumed responsibility for pastoral care in the convent was usually headed by a provost (Latin praepositus, anybody ‘appointed to position as superintendent, governor or administrator, reeve, provost, mayor’). Frequently he was not only the chief cleric but also assumed responsibility for all the administrative and legal matters of the community. The powers of the provost could vary greatly from convent to convent, depending on whether the foundation in question belonged to a religious order such as the Cistercians. If that was the case, the monks took over the task of spiritual ministry to the women; and the abbot who governed the men’s community was the competent clergyman. Then only the task of administering the nuns’ secular affairs (cura temporalium) fell to the provost, who was assisted by cantors, deacons and scholars. As a rule, a whole group of clergymen thus lived at or near a convent; apart from the provost, the confessor was the most important point of reference amongst them. In addition, representatives of the church hierarchy preached at services; led the nuns through the liturgy of masses and high feast days; heard confession; led processions such as the exodus from the Heilig Kreuz Kloster; administered extreme unction; performed the last rites before death and the funeral rites.

Men were also needed for the concrete administration of goods and produce on the farms, as experts for the brewery, mills and agriculture. Some of them were *lay brothers who, like the lay sisters, became part of the clerical estate; others were laymen such as stewards or farmhands, who did the heavy physical work. For example, on illustrations of feast days in the convent the nuns playing the organ are assisted by boys who tread the bellows and also ring the bells (see Figure 30 in Chapter VI.3), an activity which can also be seen when welcoming the nuns in their new home in Medingen. The old nuns and novices leave the old site (Oldemeding), weeping, following Provost Ludolf; the younger nuns greet them in a welcome procession with banners, a cross and the statues of the patron saints Mary and St Maurice.

Fig. 16 Procession to the new convent in Medingen. Lyßmann (1772) after Medingen 1499. Repro: Christine Greif.

The extent of the male guardians’ power to make decisions depended on many circumstances. The nuns could be very persistent when it came to their spiritual care, both for good and bad. In the mid-fifteenth century, for example, Kloster Lüne was drawn by Provost Dietrich Schaper into serious unrest in the town of Lüneburg during the so-called Prelates’ War. Schaper vigorously defended the interests of the Lüneburg nuns against the financial claims of the town council, a stance which made him many enemies on said council. When, in 1451, this finally resulted in a trial at which the provost was accused of disloyalty, squandering convent property and leading a dissolute life, the convent appeared in court under the leadership of Prioress Susanne Munter and presented a witness testimony written in Low German defending the provost and declaring the charges levied against Schaper to be unfounded.

The fact that the close interaction of the sexes and these diverse social groups functioned for centuries in a relatively small space was due to their body of rules and the ingenious arrangement of this space. They spent most of their time in separate areas, but were nonetheless aware of one another and, as in the convent church, could still sing together, even though the nuns could not be seen by the other groups. This was due not least to their common goal, namely, to enable a spiritual life in enclosure dedicated to the praise of God.

3. Representation and Status

The Tristan Tapestry

What is a story of adultery doing in a convent? The nuns of Wienhausen embroidered no fewer than three large-format tapestries depicting the love story of Tristan and Isolde, complete with love potion and bed scenes. The largest of them (2.3 metres high and four metres wide) is particularly revealing for an understanding of the meaning of these tapestries.

Fig. 17 Wienhausen Tristan Tapestry. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Wienhausen.

It depicts coats of arms and scenes from the story in alternating strips; a band of Low German inscriptions runs between them; and on the sides the pictorial narrative is surrounded by climbing roses and ivy. Just like the Ebstorf World Map, these coats of arms combine the local and the global: first comes the imperial eagle, then the Braunschweig lion – but in the top right-hand corner we also find the coat of arms of the legendary King Arthur, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem is prominently represented. In between these features, the nuns placed themselves: their family coats of arms, or at least elements which also appear in the symbolism of their families, such as the cross of St Andrew, the griffin or the lion. Whenever there were important visitors, for example from the House of Guelph, which, in the person of Duchess Agnes of Landsberg, had co-founded the convent, the tapestries with their courtly themes of hunting, battle, love and dragons could be brought out to decorate the rooms for festivities.

The nuns also memorialize themselves on the tapestries through their own interpretation of the Tristan story. At the centre of the Tristan Tapestry, both literally and figuratively, are the women and their astuteness. After Tristan sets off for Ireland to fight Morolt in the first strip and returns wounded (the direction of travel back and forth across the Irish Sea can be seen from the fact that the horse looks once to the left and then to the right as it watches Tristan row), the second strip has in the middle the two scenes with Queen Isolde and her daughter of the same name. They drag Tristan, who has disguised himself as a minstrel, into the fortress-like city of Dublin and heal him. While the two crowned women stand tall with their ointments, small, sick Tristan crouches between them. The bottom row of images repeats the depiction of the women’s power to save from illness and threat. When Tristan faints from the poisonous fumes emitted by the dragon he has defeated, the three women find him (the servant Brangäne has joined them), literally pull him out of the swamp, bathe him and escort him to the royal court. In the bathtub he again sits small among the vigorous, active women; one of them, the young Isolde, has seized his sword. In the known versions of the Tristan story she raises her weapon in this scene to take revenge on Tristan for the death of her uncle Morolt, but the Low German inscription on the tapestry turns this around: ‘There stood Lady Brangäne and healed him; Lady Isolde anointed him. Then she bathed him. Lady Isolde held the sword’.49 Threat has turned into protection; and it is clear who holds the threads of the narrative as well as of the embroidery: the nuns, who turn forbidden love into a story about the fight against evil and salvation from sickness and death by women.

Fig. 18 Bathing scene from the Wienhausen Tristan Tapestry. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Wienhausen.

The Black Knight Maurice Intervenes

A unique testimony has been preserved from Kloster Medingen which provides us with some insight into how the nuns themselves conceived of their history. There are fifteen pictorial panels from 1492 with detailed captions in Latin and German explaining how, since its foundation, the community had been divinely guided and how heaven had repeatedly intervened to further the convent’s interests. The originals, which hung in the abbess’s house, were destroyed by fire in the eighteenth century, but thanks to 18th century copperplate engraving where the Protestant chronicler of the convent history very accurately copied the preparatory drawings for the panels, even including the notes for the painter regarding the colour of the nuns’ habit and cloaks, the iconographic programme can be reconstructed. Previous chapters already introduce depictions of nuns on the handcart (Figure 10) and of the feast marking the consecration of the new convent (Figure 16), but the nuns’ view of their own history becomes even clearer in the pictures which show how they have repeatedly and energetically been helped by saints. On Panel 9, the Virgin Mary, patron saint of the Cistercians, orders the construction of a new convent; and on the next one, John the Baptist, one of the patron saints of the city of Lüneburg, personally clears the land for it.

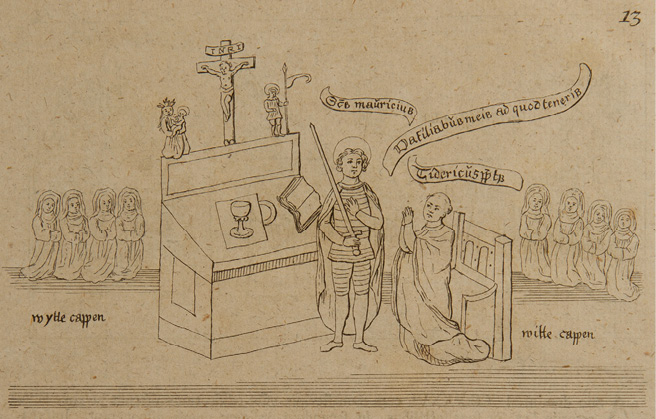

Fig. 19 St Maurice threatens Provost Dietrich Brandt. Lyßmann (1772) after Medingen 1499. Repro: Christine Greif.

The saints’ active solicitude for the nuns is particularly clear on Panel 13, which depicts a scene during a Christmas mass with Provost Dietrich Brandt, who held office at the end of the fourteenth century (1380–96), as the inscription Tidericus prepositus reveals. He kneels with raised hands before the patron saint of the convent, St Maurice, depicted as an armed knight, who presents his sword and in a speech scroll exhorts the provost to provide the nuns with what is due to them: ‘Give my daughters what you owe them’.50 The nuns, dressed in their white festive robes, kneel in two groups in the background.

Accompanying texts explain in Latin and Low German what is meant by the scene. The Low German text reads: ‘When the previous provost had died, they elected Master Dietrich Brandt, who once during Advent withheld the provisions due to the nuns and gave them nothing to eat. During Christmas mass, when the provost was sitting on his chair by the altar, it came to pass that he saw St Maurice in front of him with his sword unsheathed, and the saint said to him: “Give to my dear children what you owe them”. Then the provost rose and fell to his knees and the whole convent joined him, though they did not see him, only the provost did’.51

Thus the patron saint intervenes in his own person and with some force. It is as if the figure visible in miniature on the altar suddenly springs into action larger than life. The scene allows us an insight into the way space is organized in Medingen. The rendering of the space is of necessity highly simplified, but it is obvious that the nuns are depicted as observers, albeit distant ones. From their seats they follow the events at the high altar. As the caption describes, the nuns have fallen to their knees on seeing their intimidated provost falling to his. In the centre of the image stands the high altar of the convent church with *paten, chalice, and book; across it at the back is an altar-like rectangular panel bearing the statues of Mary and Maurice to the right and left of a crucifix. The climax of the celebration of the mass, the transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, is imminent: the chalice is already on the *corporal, the rectangular base for the communion vessels; the paten, the plate for the bread, is half covered by it. To the right lies an open book, the missal, from which the priest was meant to read the words of consecration. If the depiction were liturgically correct, the volume would, seen from Christ’s position, be on the right-hand side of the altar, where the Gospel was read out. The provost would be standing in front of it with another, assisting priest. Yet this is not a snapshot of a historical situation. The panel was only created one hundred years after this incident is said to have taken place. The event is concentrated symbolically, preserved for the memory of the community and recognizable to fifteenth-century viewers as history which is of ultimately timeless validity. This is why the figures on the altar – Maurice, the armoured knight with the fluttering standard, and the Madonna – correspond to the statues that could be seen on the main altar in the convent church.

The large altar statue is lost; the small statue of St Maurice that has been preserved in Kloster Medingen shows the same type of armoured knight with curly hair and fluttering standard. It was commissioned by Abbess Margaret Puffen in 1506 and made by the renowned sculptor Hermann Worm whose dragon stamp (as canting arms symbolising his name ‘worm’ = dragon) and hallmark to show the purity of the gilded silver is visible at the front. At the feet of the saint clad in duckbill-style sabatons (iron shoes as part of plate armour), above an intricately worked octagonal base, an engraved scroll has the statue speak to the viewer: ‘In the year of our Lord 1506, the venerable Lady Margaret, the first abbess in Medingen, had me made in praise of the Lord and St Maurice’.52 The statue completed the furnishings of the new abbess’s office. While the portrayal of Maurice in the Medingen manuscripts follows the general template for saints, namely a youth with red cheeks and armour only sketched in schematically on the blank parchment, in the commissioned works which were executed in Lüneburg by professional craftsmen he is depicted as a black knight in fashionable ceremonial plate armour, with feathers and precious stones adorning the crown on his head.

Fig. 20 St Maurice. Lüneburg: Hermann Worm 1506. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Medingen.

For the nuns, the chivalric St Maurice was of considerable importance: he made the convent attractive to the surrounding nobility. Today, one might speak of a ‘company logo’ or ‘mascot’, even if this only partially reflects his significance for the identity of the nuns. His accompaniment of them runs like a golden thread through the history of the convent: a statue of Maurice travelled with the first nuns from Magdeburg, where he was the patron saint of the diocese, and was carried ahead of their procession from Old to New Medingen (Figure 16). The importance of the saint in the furnishings of the convent is also evident from the fact that the statue was one of the few items saved during the fire in the late eighteenth century, along with the abbess’s ceremonial crosier, also displays Maurice as a black knight.

The community of saints surrounded, protected and adorned the nuns’ devotions. In the inventory of the furnishings of Kloster Medingen compiled in the mid-eighteenth century, the following are listed for the nuns’ choir alone: a triptych with apostles in two rows; another shrine to the apostles from the fourteenth century; a large wooden crucifix; a painting from 1504 with the head of Christ; a painting on which the scene on the Mount of Olives is expanded to include the figures of the Virgin Mary and St Bernard of Clairvaux; a life-size Man of Sorrows; and a wooden annunciation group in a niche. All this set the scene for and framed both the abbess’s throne with its carved canopy and the space-filling choir stalls, which held almost one hundred seats (see Figure 5 for the comparable space in Kloster Wienhausen). The statues of saints were not simply room ornaments: the heavenly patrons were the nuns’ networks for eternity. They were the promise that the women’s prayers would be answered – right down to the very tangible form of the Christmas meal, which Maurice won for them as their very own knight.