V. Music and Reform

© 2024 H. Lähnemann & E. Schlotheuber, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0397.05

Convent communities always developed through an interplay with the religious and social conditions and needs of their time. Conversely, their vision of a religious life influenced society, since their particular way of life meant these spiritual women acted as role models in medieval society. From the very beginning, convent life was exposed to constant changes and processes of adaptation; almost every generation sought to bring its way of life closer to the original ideals of Christianity, to ‘re-form’ it. The monastic reform of the fifteenth century was influenced by the devotio moderna, the ‘new devotion’, which, as a powerfully influential religious movement, was meant to bridge the gap between the individual and God through personal relationship. While earlier scholarship long regarded the late Middle Ages as a time of decline, we now know that it was precisely the great ecclesiastic and monastic reform of the fifteenth century that led to a blossoming of society and spiritual institutions and to a profounder religiosity. Enclosure, an expanded education that inspired the devotional practice and a remoulded liturgy prove this. Something else was obvious: the renewal of religious life became manifest in its music. One could hear the reform.

1. Secular Songs while Breaking Flax

It was in the summer of 1491 that Abbess Mechthild von Vechelde announced to the convent her intention to give permission for a *flax-breaking festival ‘so that’, as the chronicler says, ‘we could look forward to it since we would have great entertainment in the breaking of flax and, if we wanted, could sing songs during it. This news pleased us very much, both the old and the young and those of middle age’.93 A flurry of preparations began immediately. Because it was a long time since there had been a festival like this to mark the breaking of flax, the women tried to recall the old songs that were usually sung during this work and to adapt them for the coming festival. The middle-aged sisters and the younger nuns wrote down these songs; the girls – both the young and the slightly older ones – practised them with great zeal. So important was this pleasure to them, notes the diarist, that they did not consider what the end result of such foolishness would be, for they believed that such entertainment would be freely granted every year from then on.94

From the Songbooks

It can be assumed that numerous songbooks containing secular and spiritual song texts were written for such occasions and later passed down to us from the convents. When a suitable day arrived, ‘our abbess had the linen brought and taken into our courtyard; and she ensured there was a wheel in the barn so that we could spend a cheerful day there breaking the linen. To help us, she allowed our familia to enter, both the men and the women, the confessor and the provost, the scholars and whichever of the others wanted to be there’95 – in other words, also the servant-girls and the prebendaries. For this one day, enclosure, usually strictly observed in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, was lifted. The nuns, especially the younger ones, and the novices, the maids and the lay sisters sang spiritual songs together – or even secular ones whose content was also acceptable to convent residents,96 as the Cistercian diarist adds. When they no longer knew any further respectable songs to sing, they let the maids and the prebendaries sing secular songs and whomever wanted to join in on the singing.97

A Godly Feast?

At that, time Salome, the daughter of Konrad von Schwicheldt, a member of the lower nobility, was living as a guest in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster along with a lay sister. They had come from neighbouring Wöltingerode to the Heilig Kreuz Kloster in Braunschweig so that the Braunschweig doctors could more easily treat Salome’s serious illness, since the Cistercian convent of Wöltingerode was quite remote. There the monastic reform had already been introduced in the middle of the fifteenth century with a life lived in strict accordance with the rules; and it had since enjoyed the reputation of a model convent for faithfulness to reform. The lay sister from Wöltingerode was obviously shocked by the flax-breaking festival and such exuberance. The diarist notes, ‘that some of the external visitors were scandalized by it, or so it seemed to me, and above all the lay sister from Wöltingerode, about whom I have already reported, was immensely indignant: she said she had never seen or heard anything like it before, but nevertheless she disliked such entertainment’.98 The Braunschweig nuns, lay sisters, maids, priests and servants had fun: ‘For our abbess, out of respect, they sang something appropriate to her. They did something similar for the provost, singing “O best prelate” and other songs they had composed impromptu’.99 The day ended with small gifts for the singers and a communal meal for all the helpers. The provost was also taken with it, ‘or at least he pretended to be’. The singers, male and female, received prizes and the confessor and some of the priests sent gifts, ‘as if they were well-disposed towards us. Our abbess and individual sisters in office also gave a prize, even if it was not particularly valuable. In the evening our abbess gave food and drink to all who had helped’.100

Such large, exuberant festivities were probably common in many convents before the reform. Their importance for the harmonious co-existence of the various groups in the convent should certainly not be underestimated. The potential side effects were perhaps one of the reasons why the strict observance of enclosure emerged as one of the first demands of the reform movement. The tradition of convent festivals had evidently been curtailed in Braunschweig’s Heilig Kreuz Kloster as well, but not completely discontinued. However, even this small festivity on the occasion of flax-breaking, one in which the whole monastic familia had taken part, now no longer seemed in tune with the mood music of the times. Some from the convent’s social sphere, whose names and positions the diarist did not know, took offence at the festivities and induced the confessor and the provost to reprimand the nuns for this enterprise. Thus the diarist’s merry account ends on a sombre note: ‘And I have described all this in such detail because we had not been allowed such entertainment for a long time, nor were we able obtain it again for a long time, because it provoked great ill-feeling, since some were very displeased with everything that had happened on that day and condemned it severely. They also persuaded our father confessor to condemn us, to rebuke us, mainly, it seemed to us, to ensure that similar things do not happen more often’.101 The provost Georg Knochenhauer reacted strategically when he avoided a similar situation in future simply by prohibiting the cultivation of flax in the convent garden – without revealing the reason, of course, so as not to offend the women of the convent.

2. Convent Reform

Music was indisputably at the centre of the nuns’ lives, especially in the context of the liturgy, but by no means only there. The women singing in the nun‘s choir could not be seen; they were shielded from the gaze of laity and clergy, but their voices could be heard.

Where They Sing, There Set Yourself Down

The question of which song is pleasing to God occupies all religions. The Bible also offers a repertoire of love songs in the form of the Song of Songs, which was only included amongst the canonical books because it could be understood as an allegory of God’s love for his people. Nonetheless, the erotic potential behind and alongside this book continued to inspire and to retain its explosive power. In a letter to a widow who had asked for advice on education, the church father Jerome stated categorically that young people, especially girls, should not read the Song of Solomon under any circumstances. It was above all the great Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux who, in the twelfth century, enabled the potential of this ‘Song of Songs’ to bear fruit, interpreting it as the basis for the highly personal love (conceived as transcendental) of an individual soul for her bridegroom Christ and developing it as a theological and spiritual approach of considerable appeal. The nuns’ devotional texts are, therefore, full of quotations and images from the Song of Songs praising the heavenly bridegroom Christ as the heavenly bridegroom and Mary as a role model for the bride of Christ and first amongst virgins. Just as the songs of the Old Testament were repeatedly understood in new ways and blossomed in new contexts, so was everyday life in the Middle Ages shaped by fluent transitions between spiritual and secular songs.

On the one hand, the songs and chants of everyday life and church festivals followed fixed norms; on the other, every religious order, such as the Cistercians, had their own tradition. Moreover, each monastery or convent celebrated their own patron saints and special feasts. The well-informed could recognize monks and nuns by their singing. The soundscape of the convent was varied – and by no means only spiritual, an aspect which admittedly sparked controversy time and again. In addition to the sung liturgy which accompanied the nuns’ lives and in which changes became an audible feature of reform, this also affected oral traditions brought into the convent from the outside world.

Writing a sermon for her fellow sisters in a North German convent, a nun begins with a ‘pretty little song’, which she says secular people ‘usually sing with pleasure’.102 It tells of a blossoming apple tree under which lovers desire to meet, wishing that summer would never end, as it says in the refrain: ‘And she shall be my love all summer long, and that shall last very long; long, long shall last, even longer shall that last’.103 Similar songs with refrains such as the ‘long, long’ repeated here are also entered by the nuns into their devotional books. These include, for example, a song which the nun Winheid wrote in her devotional book in 1478. It relates how King David himself plays the harp for the nuns to dance and Mary is called upon in the refrain to lead the heavenly dance:

King David plays the harp for the dance, he plays the harp well and eagerly, we may well long for it, what joy is in the kingdom of heaven! Mary, honey-sweet Mary, Empress Mary, help us, noble, fine virgin, so that we may perform this dance.104

Secular and Sacred Music in Dialogue

We can assume that on occasions such as the flax-breaking, songs of this kind were reworked to suit the occasion and then actually sung. In this way secular and spiritual song texts cross-fertilized one another – a creative and quite characteristic mixture with which we are already familiar from the convents. The song texts found, for example, in the Wienhausen Songbook, a collection from the fifteenth century, are not actually offensive, but certainly include texts which gently mock the clergy and which one can imagine being received with a frown by the provost. The song ‘Little Donkey in the Mill’ (asellus in de mola) is one such song. It tells of a donkey who signs off work at the miller’s in order, with his ‘i-a’ (hee-haw), to succeed as a Latin singer in the choir and forge a career as a cleric: ‘I sing in the choir in order to obtain a big *benefice; when I open my mouth, “i-a” comes out; I don’t want to carry sacks any longer’.105 Similar mockery of the clergy’s ability to read and sing the liturgy is also visible on a keystone in the cloister of Kloster Ebstorf. It shows the donkey standing on its hind legs, its mouth open, in front of a large lectern, while the open book in front of it reveals the letters ‘I’ and ‘A’, which it sings. Opposite the donkey is a wolf dressed as a deacon with a thurible and a candle; judging by the wolf’s open snout, it howls along with the donkey’s braying.

Fig. 25 Keystone, 2nd half of the 14th century. Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis ©Kloster Ebstorf.

The secular songs on the occasion of the flax-breaking festivities also created similar offence to the guests from the reformed convent of Wöltingerode – the sick nun and her aide (a lay sister) – because their reform liturgy had been kept simpler and stricter and these people were thus critical of polyphony or accompaniment by musical instruments. This was another decisive feature of monastic reform.

The Reform – A Second Foundation with New Rules

This alone shows that introducing monastic reform into a convent was by no means an easy undertaking. Religious communities enjoyed a way of life which had often been established for many generations and which they sometimes defended with all their might. For this reason a bishop, a senior member of the order or sometimes even the territorial ruler attended the introduction of reform in order to make the gravity of the situation clear to the nuns. The first thing they did was to take stock of the situation in the convent, known as a visitation, which was then coupled with binding recommendations for the women. After that, the men’s task was over. They could not undertake the task of familiarizing the nuns with their new daily routine, with the conditions of strict enclosure, with managing the convent economy so as to put food on the common table, or with the reform liturgy. As a rule reformed nuns from neighbouring convents were summoned to instruct and guide their sisters. Being called upon to aid reform in another convent was a very honourable, but sometimes difficult, task. Accepting the monastic reform meant a new beginning in the eyes of all involved; it became a second act of foundation, one that the Heiningen nuns decided to record for posterity on their Philosophy Tapestry. Some of the women took on leadership functions in the new convent; others later returned to their own convent, with the result that close relationships developed between the reform convents – the nuns’ networks.

From the visitation records106 in Kloster Medingen, we know precisely what the reform theologians considered to be the decisive characteristics of a convent life which obeyed the rules because they recorded this in sixteen points. The first, and for them the most important, was to follow the Liturgy of the Hours, at night just as scrupulously as during the day. In the second paragraph, they stipulated the unconditional community of property. All personal property was to be donated to the convent. In addition, it was important to them to prevent the nuns from having direct contact with the secular world around them. For this purpose, a window for communications, probably covered by fabric or a grille and equipped with a turntable (rotula), was to be installed; it was only to be used with the special permission of a ‘window sister’ (fenestraria), yet to be appointed, and the prioress. In the confessional, an iron grille also served as a screen so that confession could be heard without direct contact. Through the introduction of strict enclosure, upon which all convent doors had to be fitted with double locks, they intended to prevent nuns from leaving the convent without permission (active seclusion) and, except in dangerous situations, to deny entry to all outsiders (passive seclusion). Only the provost and the abbess were each to have a key for faithful safekeeping. The next paragraph demanded the strict implementation of the prohibition on speaking, which was to be observed without exception in the dormitory, refectory, choir, and cloister. No conversations were to be allowed anywhere after compline and before the end of prime. In addition, they imposed ‘chapters of fault’, at which the nuns in the chapter had to confess in front of the community any rule transgressions such as breaking the ban on speech and atone for them. This strict examination of their own behaviour in the penitential chapters furthered the ability of the nuns and monks to reflect on their own actions, which is why the reformed way of life led not least to a high degree of self-discipline.

Since the reform required change in all areas of life, it had to be ‘learnt’. For this reason, the next paragraphs stipulated the following for Medingen: two Cistercian nuns from a neighbouring reformed convent were to be summoned to instruct the Medingen nuns. This requirement was to be adopted ‘without grumbling or resistance’ (sine omni contradictione et rebellione) until everyone had been familiarized with the demands of living in accordance with the rules (in regulari vita). Some nuns ate well because they were better placed thanks to their families, while others in the convent went hungry: in other words, the differences in status characteristic of the society around them filtered through into the community. To prevent this, a decisive component of the reform was the provision of meals for all nuns. This communal meal was to be introduced into the refectory, accompanied by table readings from religious texts taken from the prioress’s canon of readings. Of course, the new rules had to be enforced in part against the will of some individuals, which is why the installation of a penitential cell was prescribed in Medingen in accordance with the Cistercian statutes so that punitive measures could be taken. Strengthening community life also dictated that sick nuns no longer had to go home to their families to be looked after: a room was to be converted into a sick chamber and two sisters were to be delegated to bring meat, fish and whatever else was needed to the sick. Supplying about sixty to eighty nuns and the lay sisters with all the necessities of life throughout the year constituted a great logistical achievement. It required the provost’s full attention and capacity for work, which is why his residency and presence were mandatory unless there was a compelling reason keeping him away. After all, it was his responsibility to ensure that all the nuns were provided with food and clothing.

As can be seen clearly here, convent reform also had an economic side, because the convent properties and revenues had to be sufficient to provide for the entire convent, the lay sisters, and the servants for twelve months of the year. Adoption of reform therefore entailed reorganization of the estates, whereby the professionalisation of their economic management becomes apparent in the creation of account books, for which the nuns frequently assumed responsibility themselves after the reform. Strict care was taken to ensure that no greater number of girls were allowed entry to a convent than its economy could later provide for as nuns. Since the convent depended on good relations with the girls’ families, the problem of rejecting candidates was referred upwards to the next level in the hierarchy, namely the bishop. The Carta decreed that new sisters could only be accepted with the express permission of the bishop until a final quota had been established. All in all, the entire convent had to become firm in their grasp of the rules, which is why it was stipulated that the Cistercian regulations and statutes should be acquired in writing, if possible, in order for the nuns to see clearly what was permitted and what was not. As a final point, the Medingen reformers addressed a very central concern: women’s convents in particular had often taken in girls from the secular world for training and education only. This option was very popular with families because there were no other institutions providing education for women in the Middle Ages. Families were willing to pay well for it, and the religious communities often depended on this money. This practice was now to be stopped because tension was caused by the close association between girls who would become future nuns and those who would later return to the world and marry. Secular pupils were, therefore, no longer to be admitted so that the sisters could devote themselves to divine worship without being distracted. Only those who wished to be robed as a religious person in the future were to be admitted.

The Monastic Reform as a Narrative of Progress

‘After performing these tasks, the bishop departed and left them cartam visitasionis and a new seal’, reports the Medingen Chronicle in the eighteenth-century copy of Abbess Clara Anna von Lüneburg. Some of the points listed were probably implemented immediately, as demonstrated by the report on the commissioning of the required Cistercian Rule from the scholastica and of the mandated table readings from the vicarius. The implementation of the reform is impressively rendered in visual history of Medingen mentioned before, as penultimate panel of the series commissioned by the abbess to show the convent going from glory into glory.

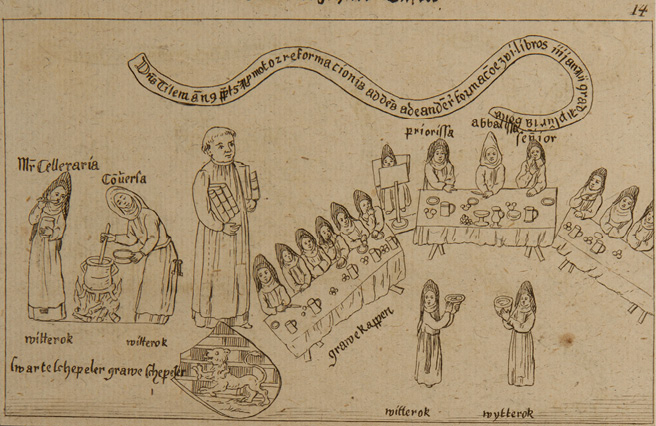

Fig. 26 Communal meal after the reform. Lyßmann (1772) after Medingen 1499. Repro: Christine Greif.

As is typical of medieval images, representation and interpretation are inextricably linked. The results of the reform are arranged together in a bird’s-eye view as visible signs of renewal. On the left stands the nun in charge of the food, tasting the stew prepared by the lay sister in charge of cooking. This marks the fact that the nuns no longer individually cooked their own soup (or ‘did their own thing’), but that the food was prepared and eaten together. The engraving also copies the annotations added to the sketches for the painter, probably an artist based in the city. These annotations not only record the functions of the women, such as Mater celleraria – the sister acting as steward of kitchen and cellar and here tasting the soup – but also the colours of the garments. The habit worn by the order was also a visible sign of the reform because the black veil (swarte schepeler) for the celleraria, meant to be worn with the white dress (witte rok), had only become pointed in the reform. A black habit marked a nun as a Cistercian; before the reform, they wore a white round veil like the ones used by other orders.

The officeholders are enthroned at a separate table with the abbess in the middle and the prioress on her right; to the left and right the convent community sit at long tables – the same arrangement as in the choirstalls (see Figure 5). In the background a sister is visible on a high chair with a lectern, reading aloud during the meal so as to combine physical with spiritual nourishment, as required by the Visitation Act – actually a practice which had existed since the start of monasticism, but one which could only be put into action if there was a common table around which the whole community gathered. The aforementioned canon of readings of the Medingen prioress has not been preserved, but we know from medieval libraries such as that in Kloster Ebstorf or the library of the Dominican Sisters of St Katherine in Nuremberg that saints’ legends, providing exempla for the nuns’ own lives, sermons together with interpretations of the liturgy were read out at table, knowledge indispensable for the nuns’ understanding of their own way of life. In a nice circular way of events, the German version of this book, ‘Unerhörte Frauen’, has been used as table reading in the Benedictine Abbeys of Münsterschwarzach and Maria Laach – a fact which certainly would have pleased the nuns of Medingen and the other convents discussed here.

In the picture the provost appears in the refectory with folio-sized books under both arms. The accompanying text explains that these are six liturgical manuscripts which he had commissioned in Braunschweig, his hometown.107 The provost is depicted as much larger than the nuns, but this portrayal of him does not mean that those who designed the cycle had failed to master rules of perspective. Rather, it derives from medieval conventions for measuring importance: the special significance of the provost for the convent and for the new beginning represented by the reform is illustrated here by the representation of him as bigger. With his coat of arms, the Guelph lion awarded to him by the duke, the provost carries with him not merely the liturgical books with their music but, as it were, the reform itself.

The Nuns’ Networks

For the practical instruction of the Medingen nuns in the new way of life, reform nuns from neighbouring convents were called in, as suggested in the visitation report. The abbesses from Kloster Derneburg and Kloster Wienhausen, as well as three nuns and two lay sisters from Wienhausen, arrived in Kloster Medingen for three weeks in order to introduce and implement the work of reform. While introduction of the reform in the Cistercian convent of Wienhausen had led to fierce arguments and even violence and in Kloster Mariensee the nuns had even cursed the convent reformers with Latin chants, this mediation ensured that the reform process in Kloster Medingen evidently went smoothly. After only a few weeks, communal meals had been introduced and private possessions handed over: ‘The nuns brought everything they had kept in their private household, including precious things such as rings or money, all they had saved also for comfort in their old age, books etc., to a collection point’.108 On Laetare Sunday (4th Sunday in Lent, named ‘Rejoice’), they ‘left their keys with the prelates and prioress, as well as everything they privately owned in terms of gold, silver and money. Each person had previously provided themselves with all the necessary goods, meat, fish, beans, peas, groats, honey, oil, butter, cheese, etc. All this they left cheerfully, gladly and willingly’. The chronicler adds: ‘But they also noted that the flesh was still weak’109 – the biblical reference to Matthew 26:41 (‘the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak’) probably a veiled hint in the otherwise consistently positive picture of the nuns’ willingness to reform the convent, suggesting that some found it more difficult than others to relinquish their possessions.

Moreover, the rules governing fasting could naturally be enforced more strictly with communal meals than if individual nuns kept their own households. On the other hand, communal meals gave everyone the chance to enjoy any delicacies equally. The Wienhausen Chronicle notes that Susanne Potstock, the first abbess after the monastic reform, gave out ‘not only half a jug of beer every day, but on fast days a whole jug’ for each nun and also ‘a certain quantity of ginger, figs and raisins during Advent and during the fasts, and a cake made of wheat during the fasts’.110 The provost had to provide bread and beer; also, in the case of Wienhausen, 12 fat pigs, 10 three-year-old cattle, 30 mutton or sheep, 4 tons of fresh butter, 6 tons of herring, dried cod, 3 tons of cheese, 120 chickens, eggs, almonds, rice, vegetables, milk and much more on an annual basis.

Susanne Potstock had brought personnel from Wienhausen as support. Amongst them was Margarete Puffen, a nun in the convent. In 1479 she was elected prioress in Medingen in the presence of the abbot of Scharnebeck, the provost of Ebstorf and town councillors from Lüneburg because the old prioress, Mechthild von Remstede, who was already bedridden during the reform, could no longer fulfil this office. Puffen was officially released by Kloster Wienhausen for this task. A year later, Kloster Derneburg offered spiritual friendship to the newly reformed convent, thereby officially admitting Kloster Medingen to the network of reform institutions in Lower Saxony. The convents which had helped each other with the reform continued to provide mutual assistance beyond the actual reform period. From Kloster Derneburg, whose abbess had first helped to reform Kloster Wienhausen and then Kloster Medingen, via Kloster Wienhausen, a family of successive spiritual generations was created in which mother and daughter convents were in regular contact, not least through their lively correspondence.

In Seclusion

The convent reform had far-reaching effects on the daily life of its inhabitants, male and female, of the nuns, lay brothers and sisters and the group of clerics and pupils around the provost. The reorganization of the estates made it possible to run the economy more effectively, from which the necessary alterations to the buildings had to be financed: a common dining hall; a common dormitory; the walls, locks and doors which were necessary to maintain enclosure. The nuns’ choir was furnished with further sacred pieces. After that, the provost was only allowed to enter the area for the washing of the feet on Maundy Thursday; and from then on secular guests were only permitted on high feast days, such as the investiture of their daughters. In the church, they were now even more strictly separated from the nuns. To this end, the area under the nuns’ choir, which belonged to the parish church and was intended for its congregation, was vaulted over. In a directive four years after the visitation, the Bishop of Hildesheim and Verden reminded the provost of the obligations arising from the visitation and instructed him to build the promised guest house so that the enclosure of the nuns could be all the more bindingly observed. On pain of excommunication, the nuns were no longer allowed to receive secular guests or to supervise pupils from outside the convent.

Antiphonal Singing

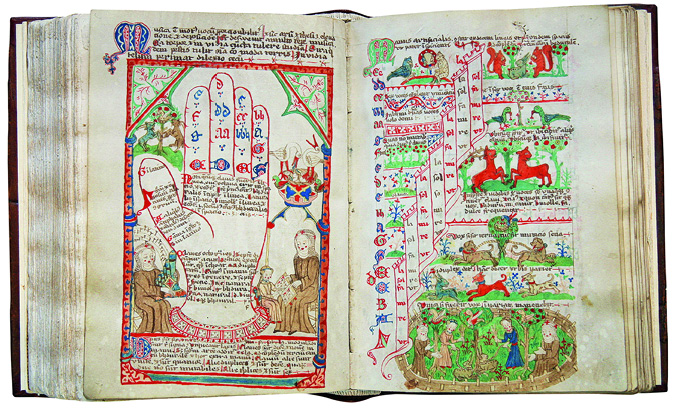

The community of nuns was organized into two groups, which sat opposite each other in the nuns’ choir, as can still clearly be seen in Kloster Wienhausen to this day (Figure 5). The liturgy was a dialogue – with God, but also with one another. The singing was led by a precentor, the cantrix, and her deputy, the *succentrix, who, alternating, sang the antiphons, psalms and chants of the Liturgy of the Hours and, in addition, the more complex *sequences and chants on feast days, for example for the Easter celebrations. The texts and the manner of their performance were noted down in large parchment choir books, which were expensive and very time-consuming to produce. When the chants for the church year were changed, these choir books also had to be rewritten. It is in this context that the image of the Guidonian Hand (Figure 27) used in music lessons has come down to us from Kloster Ebstorf; and from the manuscripts there we also know that the first thing to happen after the reform was that the nuns, working night shifts, wrote down the new liturgical chants on slips of paper. These chants were quickly learned by a few nuns in order then to perform them as antiphons in two choirs of six nuns each until the entire community had mastered the new repertoire.

3. Music Instruction in Kloster Ebstorf

Books are complex sign systems. This is all the more the case when they contain not only script and illustration but also musical notation. These signs must literally be deciphered, their meaning recognized and then transposed into practice in performance, rendered audible in divine worship or devotion, all of which demands a system of several stages. These are ‘narrative images’, which do not depict reality but seek to explain to the viewer multi-layered facts within their semantic context. How this process worked at the time is seen particularly graphically in the double page from a manuscript for music instruction in Ebstorf, which is densely decorated with symbols, pictures and texts.

Fig. 27 Guidonian Hand. Klosterarchiv V 3, 15th century, fols 200v–201r. Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis ©Kloster Ebstorf.

A Mnemonic for the Singers

The depiction of the double page with the Guidonian Hand combines this visual aid for learning intervals with music theory definitions, mnemonic verses and little scenes as illustrations. The hand, which assigns notes within the hexachord system to the joints of the fingers to aid memorisation, is intended to facilitate the learning of liturgical chants through the conception of intervals. In conjunction with the towers on the right, illustrating the graduation of the scales, the concept is based on the pedagogy for religious music associated with the name of Guido of Arezzo (c. 992–after 1033); depictions of the hand are transmitted from the twelfth century onwards. The texts explain that thorough contemplation of the ‘artful hand’ (manus artificialis) opens the way to understanding its musical components, provided they are studied closely. This is underlined by an accompanying animal scene: a monkey, sitting casually with crossed legs next to an owl, provocatively holds a mirror in which the profiles of both animals can be seen, along with the monkey’s spotty fur. A pictorial commentary, the scene holds up a mirror to students of music: which animal do they wish to follow, the wise owl or the silly monkey? The admonition to the nuns is quite clear: anyone who evades the step-by-step didactic introduction to music offered here will not gain a true understanding of its spiritual content. The two squirrels on the right demonstrate how the road to revelation is to be opened: by cracking nuts, a popular image for the value in working one’s way through hard shells to the tasty kernel.

Fig. 28 Owl and monkey looking in the mirror (detail from Figure 27). Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis.

On the left side, too, symbolic animal scenes are assigned to the two nuns: the one making music and the one teaching. The suggestion of a roof arches over the depiction of teaching; a nest with two storks can be seen on its battlements. One of them feeds the young in the nest; the other one, its beak open and its head thrown back, signals nature joining in with the jubilation of Creation. This also provides us with information about the musical lesson taking place underneath. It is part of the tenderly affectionate upbringing of the girls in enclosure by means of role models: with a stylus, her writing tool, the pupil sitting on the low chair traces the line marked out for her by the teacher’s pointing hand. On the left, a nun playing the organ demonstrates that learning to read musical notation is worth the effort. Music lessons in general, as emphasized in the various tracts from Kloster Ebstorf, are not primarily about the acquisition of theory. On the contrary, the nuns should apply what they learnt so that the celebration of the liturgy could bring them joy.

At the same time the leaf of parchment with its detailed diagrams illustrating musical theory, the professional notation and, not least, its rich decoration with images documents what could be achieved in the field of manuscript production and illustration through training in the convent. Finally, the page layout and the adept use of colour are proof of great skills in graphic design. The materials for the long production process were largely produced in the convent itself. The parchment (from animal skins) and paper (from rags) were rarely produced in the convents themselves, but were usually bought in from outside as the basis for writing. The further preparation of the material, though, lay with the scribes. They smoothed and prepared the parchment further; cut the quires to size; and pricked out the lines on the writing material with the pricking wheel, a tool which allowed several pages to be set up at once by rolling a small wheel with sharp points over the pages. In addition, they boiled the ink, for which recipes have survived: for example, for the boiling down of oak galls. They also cut the feathers of different species of birds to produce nibs for strokes of different thicknesses. These quills then had to be regularly re-sharpened when they became blunt. Protective parchment covers were made for the household-management books by the nuns themselves. ‘Hardcover’ leather bindings over wooden boards were also occasionally made and repaired in the convents to protect the precious parchment or paper blocks and to make the manuscripts ‘library-ready’, sometimes also chained, as surviving staple marks show.

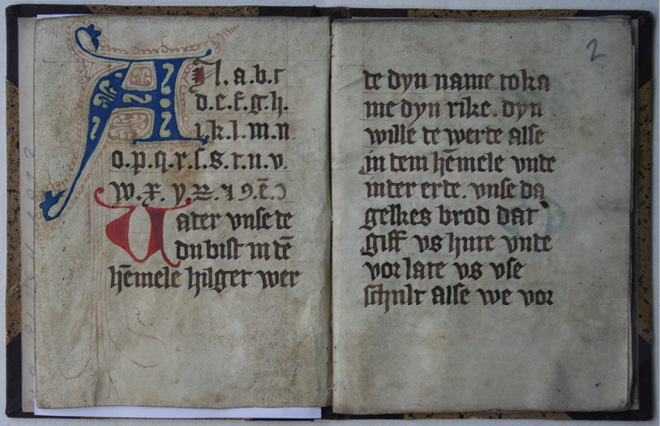

Moreover, a slim sample book from Kloster Medingen, written in Low German and containing the alphabet, the Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary, and other daily prayers, shows that templates were also provided for the lay sisters which they could use as a guide when creating their own prayer books.

Fig. 29 SUB Göttingen 8º Cod. Ms. Theol. 243, fols. 1v–2r, c. 1500. Photograph: Hans-Walter Stork ©SUB Göttingen.

The Reform – An Intellectual Training

The reform of the liturgy in the fifteenth century thus demanded intensive intellectual and musical training, which was part of building a community. In 1495, an elderly nun in Kloster Ebstorf noted, with a withering look at the younger singers, that she had never heard such bad choir singing in all her sixty years in the convent. She admonished them:

Make an effort to sing and read correctly, observe the pauses for breath and the caesuras in half verses and help the precentors on both sides of the choir faithfully. Do not sit there in silence and let them sing alone as often happens! You should now make an effort. Things will become clearer to you with time so that you will then understand all the better what you are to do.111

There were clear monastic guidelines on ‘how to sing and how we should recite the psalms’, which were quoted and commented on in Kloster Ebstorf:

We are not to drag out the psalms too much, but sing them in a well-rounded way, with a lively voice, that is, resonantly, evenly and regularly, not trailing and all too slowly lingering, but also not too quickly so that it does not sound frivolous and skittishly skipping. We should strike up the verse together and end it together and observe the pause together in the middle and at the end of the verse.112

All in all, ‘we are to sing manfully’ (Wy schollet synghen menliken, respectively in the Latin text: viriliter). This means, first and foremost, the performance style of firm, straight singing, but it is also a remarkable demand. Especially after the reform, the nuns saw themselves as part of a culture of singing that could and should be cultivated in women’s convents as well as men’s monasteries.

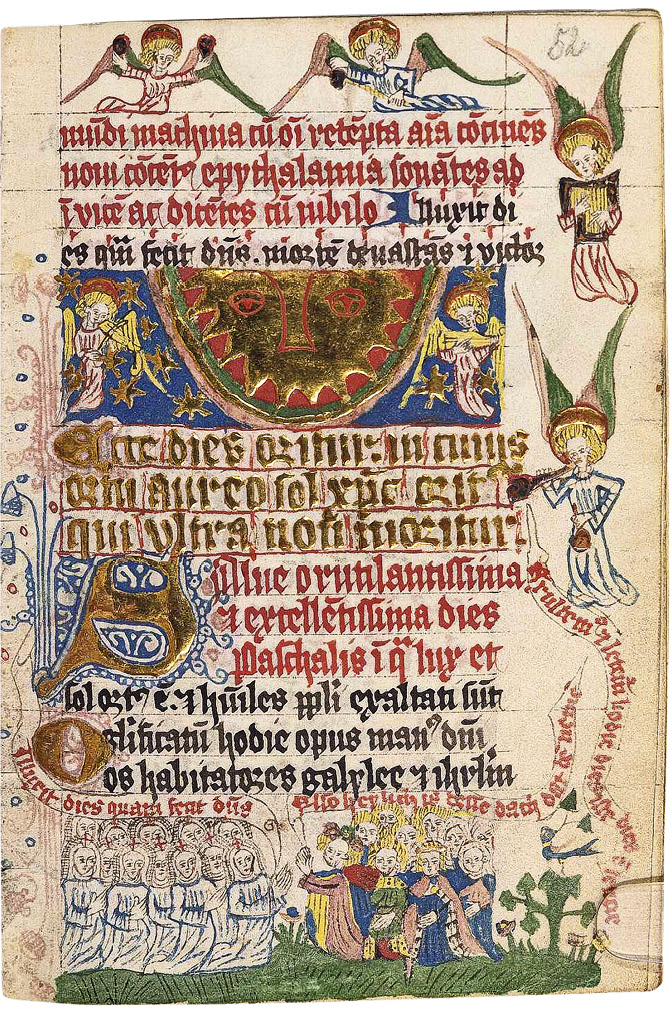

So it is above all the singing that, from a musical point of view, stands at the centre of the reform. The organ is the only musical instrument for which there is firm evidence in convents, although its use was not uncontroversial. Indeed, the renunciation of organ-playing is mentioned as a feature of the reform in Kloster Ebstorf, along with the renewal of the liturgical books. As always, regulations and implementation are not necessarily synonymous. In Medingen, even after the reform, it is certain that an organ was used at least during Easter, since the abbess’s official manual states that during the girls’ communion the *hymn ‘This is the bride of the highest king’ (Hec est sponsa summi regis) should be sung to organ accompaniment. Moreover, as we have seen (Chapter III.2, Figure 16), on the panels depicting the history of the convent organ-playing is portrayed as an ancient tradition. Throughout the sources, music-making – whether on real instruments or ‘the harp-playing of the soul’, as inner participation is called in the texts – is depicted as part of the angelic choir, of the jubilation of the spirit which moves people and even animals. As instruments of jubilation, the organs and bells were silent only during Holy Week and during an *interdict, when they were replaced by ‘wooden bells’, the tongues of a standing rattle which instead gave out the necessary acoustic signal to call the nuns to prayer. In the Medingen prayer book written and illuminated by the nun Winheid (of Winsen) in 1478, a nun plays the organ while a boy treads the bellows and rings the bell. The text for this comes from the Easter hymn Laudes Salvatori.

Fig. 30 Nun playing the organ. Dombibliothek Hildesheim Ms J 29, fol. 119r. ©Dombibliothek Hildesheim.

The soundscape of the convent, with bells, organ and the nuns’ singing, which could be heard but not seen, must have been impressive and was certainly one of the reasons why participating in services in convent churches was also attractive to lay people. After the convent reform, when the Medingen nun adapted the manual for the provost and added more chants, she also included responsories in the vernacular for the congregation and for the first time codified some of the chorales which are still sung in worship today, such as ‘Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ’.113 At Easter, the nuns in the gallery intoned the Latin sequence ‘Praise to the Saviour’, and after each verse, the laity responded from the nave with the vernacular ‘Christ is risen’.114 This is explicitly justified in theological terms when it says of Easter: ‘The laity join in the praise because on this day all nature rejoices’.115 In the common liturgy, the barrier of enclosure is overcome, and the church space expands for heavenly song. The Medingen Easter prayer books depict how heavenly choirs and the local congregation sing together on Easter morning:

The angels sing the Easter hymn ‘Let us rejoice today’ (Exultemus et letemur hodie); the nuns join in with ‘The day is dawning’ (Illuxit dies, a line from the Laudes Salvatori); and the laity respond, as they did during the Easter service in Medingen, with the German stanza ‘This day is so holy’ (So heylich is desse dach).

The liturgical performance, repeated every year in the rhythm of the church feasts, made comprehensible and tangible the wide spiritual horizons beyond the material world and opened a space for reflection on the deeper meaning of life. Music could thus become the place where lay people and members of the convent came together in shared closeness to God.

Fig. 31 Dombibliothek Hildesheim Ms J 29, fol. 52r. ©Dombibliothek Hildesheim.