VII. Illness and Dying

© 2024 H. Lähnemann & E. Schlotheuber, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0397.07

Caring for the poor and accompanying the sick and dying were an integral part of monastic life. The very first convents in the Merovingian Empire in the sixth and seventh centuries were founded together with hospitals where the poor, pilgrims and the sick found shelter. In many cases across the centuries, they were run by women. For example, on the well-known St Gall plan from the early ninth century – the ideal conception of a Benedictine monastery that was never built – a sick room is provided for the monks. That convents should be well equipped to care for the sick was also a concern of the monastic reform. Dealing with death and dying was a natural part of everyday convent life. Last but not least, intercession for the dead and the care of family burial sites were one of the nuns’ central tasks, if not their most important, for this was often already stipulated in a convent’s foundation documents.

The nuns’ networks enabled an exchange about methods of treatment as well as participation in the commemoration of the dead through prayer fraternities. There was a difference between the scholarly medicine practised by doctors, who were summoned to the convent in serious cases, and what we might today refer to as naturopathy, natural healing methods, about which a great deal of knowledge was handed down within the convents.

1. Death in the Community

After a Long Illness

For more than twenty years Prioress Remborg Kalm had managed the internal affairs of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster, overseen discipline in the convent, settled disputes or stood in for the abbess when she was ill or away travelling. Then at the beginning of 1506, she discovered a lump in her left breast as big as a small nut (nobbeke), located deep in the flesh. When she asked for advice on what to do about it, she was counselled to treat her breast with hot water. She also asked her relatives, who in turn asked several other women what could be done. One of them advised something, the other something else. In the meantime, her condition worsened. Her breast had swollen, turned hot and red and as hard as a stone. Moreover, the prioress became so weak she could hardly walk or stand, but she kept on walking and standing up as best she could. Then everything happened very quickly.

On 6 January, Epiphany, as the diarist relates, she became so mortally ill that she wanted to make confession and take communion, but because of Lent she postponed both until 16 January, when the convent would eat with the abbess. On the eve of this appointment, friends came and suggested a new treatment for her so that she forgot to make confession. That same evening, her health deteriorated rapidly, and death came swiftly and on quick feet. She was barely able to confess her sins. At the eleventh hour, the father confessor came to administer the last rites, made the sign of the cross over her, and she died. The diarist notes: ‘We were so terrified and paralysed by fear that we could not read and pray the liturgy of the dying as is fitting for the last rites and the act of dying. We immediately rang the bells and buried the prioress the next day’.137 Abbess Mechthild of Vechelde, who was also laid low, got up from her sickbed, joined the chapter meeting the following day and redistributed the offices, as was necessary.

After a Sudden Accident

The convent was responsible not only for the community of nuns, but also for the whole convent familia. Accordingly, the Cistercian nun also relates another event in the convent: a year earlier, the scholar Nicholas, who was always on hand to help with all the work, had wanted to help with the building work in the convent when he was knocked to the ground by a falling beam and lay as if dead. Deeply frightened, they poured cold water over the poor man and took him to the convent as quickly as possible so that the lay sisters could come to him and aid his body and his soul. In the meantime, they laid him out like a corpse in the provost’s office. The confessor was summoned, for when cold water had been poured over the scholar, he had regained some consciousness and had responded. Yet when the confessor wished to help him and enquire about his sins, he rebuffed him angrily and shouted at him, remembering an argument he had had with the confessor a few days before. A doctor was summoned, and the lay sisters who had rushed to the poor man’s aid returned to the convent. The doctor began to wrap the scholar in bandages so that his limbs could heal, but when he returned the next day and saw that the scholar had suffered an epileptic fit and torn and stripped off the bandages, the doctor refused to treat him further. The poor scholar was so hurt and tormented by the terrible pain that all those present were moved to tears of pity and could hardly bear to look at the poor man in his suffering:

And so there was no one who could bear to remain in his presence except one old woman, who was our prebend. She alone stood by him in everything during this most terrible time of his illness. In the three days after his fall, he grew worse and worse so that we not only feared for his life, but actually hoped for death as his salvation from his misery.138

She goes on to write:

Our Provost Georg Knochenhauer personally took care of the scholar and sang holy mass for him at Whitsun, cheerfully and with a firm voice, when things suddenly took a turn for the better and it seemed as if the scholar had been touched by the right hand of God. From that day on, he began to improve steadily, and the illness left him so completely that many later said he had never really had epileptic seizures, because these did not disappear completely, but always left aftereffects. Some were of the opinion that those seizures, the spasms in the limbs and the banging of the head, were due to the fact that at the very beginning, when he was lying there lifeless, ice-cold water had been poured over him. Then when the provost visited him on the Monday after Pentecost, he was again stricken by the old illness, from which he later died; and in addition, he was struck by blindness, with the result that he could see nothing, not even with his eyes open. When our abbess learned of this, she visited the scholar the same day and admonished him to submit to God’s will, to strengthen himself with the holy sacraments and to call for executors to make his will, which he did willingly. On Friday, he made his confession; the priests came with the last rites and communion, followed by the convent. The ailing Nicholas tearfully asked the convent to forgive him all the careless errors he had made as a scholar. The provost and the priests alternated with the convent in singing the funeral hymns, the litany and the collects at the scholar’s bedside. When the convent withdrew, the abbess stayed with him and talked to him about a variety of things that could be of use to the community, but alas, he brought none of these more useful things that he had framed in his mind to fulfilment, after his memory and reason failed together.139

That is why, to their distress, the community of nuns with whom he had lived was not included in his will.

The sick boy was now given a widow as a companion, who assisted him day and night and made sure that he wanted for nothing. She stayed by his side until his death, but when he had died, she refused to leave his room until she had received adequate remuneration. A doctor was also called again. He could do nothing but was nevertheless paid after the scholar’s death. The diarist observes:

Our provost Georg Knochenhauer counted amongst his scholars and priests some very rich and influential men who had been relatives of the scholar Nicholas so that he would have become a priest and in the course of time could have taken over the parish of St Michael and then our provostry, which is why they were always happy to oblige him. They visited him frequently when he was still healthy and then when he fell ill and stood by him in word and deed. Now, when he was ill, the scholar chose these men as his executors and made his will according to their will. Without the knowledge and consent of the abbess and our convent, he bequeathed and promised many things to them and to others, all of which they would demand and receive from us after his death, down to the very last farthing.140

Medicine has made enormous progress in modern society, especially during the last 200 years, with the result that today, dying and death have been pushed into the background. Previously, death had been an integral part of everyday life. The nuns had generations of experience in dealing with illness and the death of individuals. Convents had developed rituals of mourning and dying that closely involved the living in the process of dying. It was hoped that death could be overcome by means of common commemoration, creating a community of the quick and the dead. People did not die alone; this explains why there was always someone keeping watch at the scholar’s bedside, while all the others sang funeral hymns, litanies and so forth. In this way, it becomes clear how holding fast to life (administering medicine) and letting go (administering the Last Sacraments) went hand-in-hand. It was well known that death was not in human hands. The nuns had an exceptionally developed understanding of the art of consolation. The collection of letters from Lüne contains hundreds of letters of consolation on the death of loved ones; and the replies sometimes show that they did not fail to have an effect. This was not contradicted by the concomitant wish for the convent to be acknowledged financially after the death of the person concerned. There were also situations in which such ritual accompaniment was no longer possible, such as epidemics and pandemics, and especially the plague that repeatedly raged through Europe.

The Plague Comes to Braunschweig

During outbreaks of epidemics and plagues, communities were particularly vulnerable since people lived together in confined spaces, whether in a convent or in a city. Ignorance of the pathogens that caused the Black Death, which had become endemic in Europe after the great outbreak of 1346, but also of the causes of other contagious diseases, meant that people were almost helpless in the face of this deadly phenomenon. While the prosperous citizens in the cities could flee to the countryside and save themselves from the recurrent onslaught of the plague, a community of nuns living in isolation stood barely a chance when an epidemic hit them.

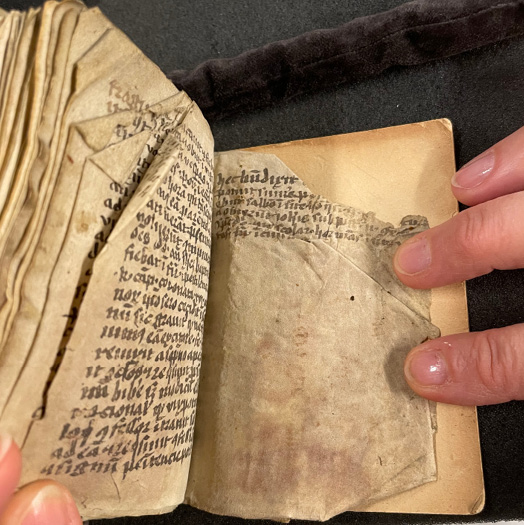

The first years of the sixteenth century were thus a difficult time for the community in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster: at the beginning of 1507, canine parvovirus broke out and their best dogs fell ill. The nuns wrote prayers such as ‘The word became flesh’ or ‘Thou preservest man and beast’, as well as other prayers, on slips of paper. The lay sisters gave these slips of paper to the dogs to eat with bread and butter – whereupon, so legend has it, the epidemic actually subsided.141 In spring 1507, the diarist jotted down her last lines on the parchment of her former prayer book; at the same time, the plague began to rage through the town of Braunschweig. Since the first great waves of the plague, the disease had broken out time and again at longer or shorter intervals, especially in the cities. Personal testimonies concerning the outbreak of the plague, especially in monasteries and convents, are very rare. The diarist obviously did not have much time left either:

Several girls, and male and female servants died of it; very many fell ill, some of whom recovered. At this time the *suffragan of the bishop of Hildesheim consecrated the cemetery of St Martin’s in the town, so our abbess had sent him the cross above the chapel by the choir with which to consecrate it. He granted a major indulgence to the cross and, out of affection, visited us personally, doubling our indulgence by both his own and the bishop’s authority and granting absolution and blessing to the convent in the nuns’ choir. At this time our procurators, Gerd Hollen and Cord Broysem, were removed from office without the knowledge and consent of the provost and our abbess, and we were given two new ones, namely Werner Lafferdes and Cord Breyer, both of whom died of the plague a few weeks later.142

It would be interesting to know what happened next. The diary of the Cistercian nun of the Heilig Kreuz Kloster breaks off abruptly in mid-sentence. Her last words are:

At Whitsun in 1507, our baker died of the plague. A few days later, Elisabeth Kalm fell so badly ill with the plague that she made confession that very evening. The next day, she took communion, received the last rites and died the same evening, on the eve of Corpus Christi, before vespers. After vespers, she was carried into the church, and the next morning we buried her at the fifth hour.143

A little later, Katharina Kampe fell ill with the plague; she was sixteen years old and had already been crowned a nun.

In the evening, she fell into such a deep sleep that we were unable to wake her. Three days later, she woke again, opened her eyes and made a sign that she was thirsty, but she was barely in her right senses and was not able to speak much. The confessor entered alone, elicited her confession, made a sign of penance, and gave her the final blessing. She could hardly drink and died the following Saturday during the night. Then our under-baker John and the scholar Hermann died in the night…144

Then the diarist fell ill and died. Only she was no longer able to inform us of it.

Fig. 33 End of the diary, HAB Wolfenbüttel, Cod. 1159 Novi, fol. 238r. Photograph: Henrike Lähnemann ©HAB Wolfenbüttel.

2. Medicinal Knowledge and the Rituals of Dying

As we have seen from the medical and spiritual care given to the prioress with cancer and the scholar who died in an accident, illness and death challenged nuns in two ways: the practical treatment of the illness and the spiritual accompaniment of the sufferer. Both required specialized training. While only the doctors who were called to the convents in serious cases had academic medical knowledge, some knowledge of the arts of healing formed part of the syllabus taught in convent schools and of the established knowledge in the convents. This knowledge is evident in the countless collections in their libraries which deal with medicine and recipes for medication, containing short Latin treatises on topics such as the examination of urine, information on the symptoms of the plague or pharmacopoeias. This knowledge was then put to use by the convent infirmary, where the infirmarian was responsible for prevention, medication, and nutrition for the sick, who were cared for with the help of the lay sisters.

The Doctrine of the Four Humours in Application

Treatment in the convent predominantly followed the *doctrine of the four humours and its diagnosis of people’s temperaments. The appearance and behaviour of a person indicated the dominance of a certain ‘humour’ – namely, whether there was an excess of blood, phlegm, yellow or black bile. Sanguine people, for example, had too much blood and were characterized by dry heat, i.e. they were ‘hot-blooded’; melancholic people, on the other hand, had too much cool, moist black bile, leading to depression. It was, therefore, necessary to analyse the patients’ respective symptoms in terms of their dampness and warmth in order to ascertain which herb could be used in their cure. For stomach aches, for example, the Low German ‘Storehouse of Medical Knowledge’ (Promptuarium Medicine), printed by Bartholomäus Ghotan in Lübeck in 1483 and copied in Kloster Wienhausen in the fifteenth century, recommended administering nutmeg, galangal, sweet flag, cloves, or ginger. True galangal, a plant related to ginger, contains pungent essential oils which can have a digestive, anti-spasmodic, anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory effect and was therefore counted among the ‘dry-hot’ spices, just like cloves or normal ginger. Accordingly, it was, and still is, used in both Asian and medieval medicine to treat ‘damp-cold’ complaints such as stomach aches. Conversely, damp-cold elderberry water is meant to be good against any kind of heat in the human body.

An astonishing variety of ingredients can be found in the prescriptions and instructions for preparing medicines. Some of their applications for everyday ailments live on as home remedies, whether it be a simple salt solution or spices, some of which are still grown in the herb beds of convents today. One formula, for example, names violet leaves, maidenhair fern, hart’s tongue fern, and oregano, ingredients that are still made into cough syrup today. Another combines field, forest and meadow herbs with other ingredients and calls for mallow, two *lots of finely chopped marshmallow, two lots of finely chopped liquorice, two lots of finely chopped male fern, eighteen finely chopped figs, one lot of mallow seeds, a small handful of winter barley, two quarts of water, and one lot of raisins. The more precious ingredients such as figs, nutmeg, and ginger, which had to be imported, were sometimes baked in order to preserve them for longer and be able to ship them. The whole life of the convent was determined by a rhythm of fasting and feasting which was set by the church year, as is also shown by the specifications of food for Lent from Kloster Wienhausen (Chapter V.2). The boundary between dietetics and medicine was fluid; and the letters from the convents frequently mention spiced baked goods, for example in the form of gingerbread (Lebkuchen), as New Year greetings, or other *pastries baked in special shapes as gifts. Nonetheless, a medical manuscript from the Dominican convent of Lemgo, written in 1350, around the time of the Black Death, informs its readers in rhymed hexameters: ‘Know this: against love no medicinal herb can be grown’.145

The medicine books or prescription slips, like those preserved in the find from the nuns’ choir in Wienhausen, albeit often in fragmentary condition, give instructions for the preparation of remedies. The following is typical: ‘Strain this through a linen cloth until it is pure. Then put the purified liquid back on the fire and add two egg whites. Let it all come to the boil again so that it produces a great deal of foam’. The subsequent use of the remedy is also specified: ‘Those who suffer from a dislocated lower jaw should finely crush cinnamon and put it in a small bag. Boil the sachet in sweet milk and then place it on the lower jaw’.146 For headaches ‘one should finely crush juniper berries and hemp and then add two egg whites. Boil this mixture together with wine and bind it on the head and forehead of the sufferer’. Calendula, spearmint (sweeter than peppermint), lavender and common liverwort are said to help against consumption: ‘These four medicinal herbs should be put into fresh beer and left to ferment in it’.147 Another recipe instructs us: ‘Take chamomile, honey, rosehip, wood sanicle, and agrimony. This is to be boiled up in old beer mixed with bean stalks that have been burnt to ashes and then this beer is to be strained. Then add red ointment to the beer and drink it with your lunch’.148 To improve one’s memory, wine should be poured onto finely chopped parsley and then this mixture should be drunk.

While some of the herbal remedies were indeed calming, anti-inflammatory, or possessed other healing properties, even in cases when a pharmacological effect was doubtful, the awareness of having been looked after and given medical treatment in the convent helped just as much – or at least as much as placebos work in modern medicine. The medieval concept of illness assumed that the soul could make the body sick and, similarly, healthy. In this sense, nursing was always as much about caring for the soul as about caring for the body, an approach that today seems really indeed modern. Of course, a modicum of miraculous healing was also part of the mix. For example, another Wienhausen prescription, one for stopping nosebleeds, states that the sign of the cross was to be made over the nostrils and the following incantation recited: ‘Through the mediation of Mary, hell is closed, the gates of heaven are opened’. Then the prologue of the Gospel according to St John was recited, from ‘In the beginning was the word’ to ‘and without him was not anything made that was made’; this was considered the most effective incantation of all. That the help from the saints invoked in prayers also extended to animals is demonstrated by the use of the verse ‘The word became flesh’ from the prologue of St John’s gospel when dealing with the sick dogs in the Heilig Kreuz Kloster. The scribe adds: ‘If you wish, you may substitute the missing name of the sick person in: “Lord be nearer to your servant / maid N”’. Then the carer was to make another sign of the cross and ‘say: from her nostrils let not a drop of blood come forth. Thus may it please the Son of God and the holy mother of God, Mary. In the name of the Father, let the blood cease, in the name of the Son’.

Plasters and ointments were made for the sick room. For example, we know from the Lüne letter books that there was a lively exchange about the preparation of a lavender ointment supposed to help against the chest complaints of an old nun. Amongst the Wienhausen fragments is the formula for an ointment that contained a mixture of herbs made both spreadable and preservable by lard: ‘As long as the poppy is in flower, add poppies, henbane, violet leaves, caper spurge, blackberry leaves, mandrake leaves, black nightshade, houseleek, greater burdock and common houseleek. These medicinal herbs should all be crushed beforehand and then boiled with the lard until everything has turned green. Then strain everything through a cloth. Put everything in a tin. This is black poplar ointment’.

Spiritual Care

If none of this helped, it was the task of the community to ensure that a dying member of the convent received last rites from the provost and an opportunity for confession and penance. The convent was at all times a community of both the living and the dead. The rituals which accompanied dying and death were one of the few occasions on which the door to enclosure was opened. This was true both for the nuns who, when the provost died, took in his body and for the provost, who sought out dying nuns and then buried them in the cemetery within the cloister. The convent was present at extreme unction as well as at the funeral ceremony itself and returned to the church together with the provost. Back in the church after the procession from the interment in the cloister courtyard, in some convents known as ‘paradise’, the nuns sang in answer to the responsory sung by the provost. It was also the provost who, in front of the altar in the church, sang ‘In the midst of life we are in death’ (Media vita in morte sumus) as the final chant. A Medingen nun’s account of the death of the provost Tilemann notes a range of sequences and rituals performed by the nuns, some of them analogous to the rites for a deceased sister. Throughout the whole of the Tilemann’s illness, readings, prayers and chanting took place at his bedside, in the cloisters and in the nuns’ choir.

Of Vigil, Mass and Burial

The psalms were read individually and collectively by the nuns at the vigil for Tilemann; the prioress arranged matters so that people alternated in groups of ten at a time and then went back to the nuns’ choir for the choir service, as the report says: ‘In the convent one psalter was read with the nuns taking turns. It was arranged so that some people remained during vespers and some went to the choir so that everyone might go to the sick chamber once. Our abbess saw to it that after the meal ten or more people read the psalter there; after compline they went in again and others came; whoever wished to stayed there throughout the night; and so it was properly and fittingly arranged that it would not be too onerous for any one person’.149

For the reception of the body the nuns sang in the provostry the responsory ‘Deliver me Lord’ with the accompanying verse from ‘Day of wrath’ (Dies irae), the hymn about the last judgement. The convent then moved into the church with the corpse carried by the clergy, and from there to the nuns’ choir, where a rich liturgy unfolded: ‘When he had been taken into the church, they sang “May the angels lead you into paradise”. This was followed immediately by the convent singing the requiem mass. After the mass we held a meeting of the chapter, then sang the mass “I am risen”.’ During these three masses the convent sang ‘sacred sequences’.150

Women and clergy then took turns during the vigil. The abbess personally supervised the lay sisters, who were in the church during the day, while the deputy provost was supposed to stand watch at night. He fell asleep during this task – something which led the nun writing the account to compare him to the guards sleeping at Christ’s tomb, before she added by way of an excuse that it was probably due to his old age. On Monday the commemoration of the dead man continued. At all three masses the nuns singing in their choir must have been clearly audible to the assembled congregation of secular visitors in the part of the church reserved for the parish. The account emphasizes that at the funeral itself the nuns held their own customary memorial service but entrusted the performance of the funeral service, in accordance with Tilemann von Bavenstedt’s rank, to Abbot Johannes of the Benedictine monastery of Oldenstadt as the celebrant and to other high-ranking visitors. From their point of view, however, its performance left much to be desired, since the visitors did not observe the established customs for the interment of a provost:

On Monday, he was buried. Therefore in the morning the whole convent wore white robes because of the funeral. We stood in the choir, read during the procession out of the church and sang ‘Maker of all things’ and ‘Deliver me’. However, we relied on the many people present who had more experience of burying lords and prelates than we did. For that reason, we gave no instructions regarding how they should hold the service as befits a prelate, but unfortunately the Abbot of Oldenstadt buried him in accordance with his own order and did not say the formula of abjuration, nor did he place a chalice on his body as is the custom, nor did he sing ‘I receive the chalice of salvation’ three times. May God forgive him.151

3. This World and the Next in the Wienhausen Nuns’ Choir

Bloodletting as Prevention

One particularly important area, which fell into the realm of prophylaxis as well as healing, was bloodletting. This was regularly carried out for the entire convent, even in the sixteenth century, as is clear from the account of the vision of Dorothea von Meding (Chapter V.3): the vision is said to have occurred after the women had just been gathered in the calefactory for bleeding. The fact that the procedure was carried out in the only heated communal room was intended to prevent attacks of weakness after the blood had been taken. On the monastery plan of St Gall, the warming house is located next to the dormitory for the sick, the bloodletting house, the bath house for the sick and a separate kitchen for the sick and those who had been bled. Their sojourn in the calefactory was certainly also one reason why the nuns positively looked forward to the dates for their bloodletting, which came round two or three times a year. Bloodletting was closely linked to the calendar, to a complex set of rules specifying ‘good’ and ‘evil’ days. Each sign of the zodiac was allotted to a particular part of the body, which was good to cup at that time. In the prayer book of Abbess Odilie von Ahlden of Mariensee, for example, a section has been inserted at the end of the prayers with the remark that the best time for bloodletting is from mid-April to mid-June, because ‘the blood then grows and increases’. A depiction of how bloodletting was conducted in the convent can be found on one of the arches in the nuns’ choir in Wienhausen (Figure 35).

A Colourful Array of Pictures

For 1488, the Wienhausen Chronicle mentions the renewal of the wall painting in the nuns’ choir, dating from the early fourteenth century, ‘by three sisters called Gertrud’. The nub of the entry clearly lies in the similarity of the names, whereas it was obviously not at all surprising that women were active as church painters. The nuns’ choir in Wienhausen displays one of the richest and most sophisticated iconographic programmes in medieval architecture to have survived in its entirety. The images cover the ceiling and walls of the choir, which has the dimensions of a sizeable church. Starting with Adam and Eve, biblical events are depicted on the walls in two strips which run all round the choir from the south- to the west- to the north-wall. The strip above these shows scenes from the legends of the saints. On the vaulting, divided into various fields intersected by the ribs, the most important stations in Jesus’s life are depicted.

Fig. 34 Wienhausen nuns’ choir. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Wienhausen.

Certainly, this richly coloured array of pictures – for example, the Red Sea into which Pharaoh sinks in his pursuit of the Israelites is actually shot through with red waves – not only provided a welcoming viewing material for the girls who, sitting on a low bench in front of the nuns, took part in divine office at certain times, but also functioned as a theological commentary on the nuns’ singing and praying. This is reinforced by the interplay of the images with the other furnishings, such as the Holy Sepulchre which must have been in a place such as a chapel accessible to the nuns; and in the placement of the individual pictorial themes next to and above one another and in relation to the architecture of the chapel. The nuns sat in the choir stalls, which were divided according to the two choirs (cf. Chapter V.2). The space, protected by stained-glass windows and well lit, was used not only for divine office but also for needlework and other convent activities. This becomes clear from the variety of objects found underneath the floorboards, which have already been mentioned several times as evidence of everyday culture in the convents. There were small weaving discs, fabric remnants, strips of embroidered cloth, appliqué work, stencils, figurines, a variety of small and very small written texts such as recipes, invoices, devotional sheets, bookmarks, and duty rotas; as well as material evidence of education, above all the oldest preserved spectacles in the world, pointer sticks, small wax tablets, and writing pens. For the nuns, the choir was a space for both working and devotion.

On the east side, it allowed access to the east choir of the parish church, meaning there was no space for paintings there. Instead, the vaulted arch between the nuns’ choir and the parish space is decorated with its own cycle of paintings combining spiritual and secular interests, namely, the depiction of characteristic activities for the twelve months of the year, known as the ‘monthly works’. Bloodletting is pictured in the first circular painting on the south side of the arch above a depiction of Luna as a woman with a moon.

A woman hands a white bandage to a seated man after she has cupped him – he still holds the bowl in his right hand in which the blood was collected. The event is not depicted as a convent act: both persons are dressed in secular clothes. Yet the nuns, as the accounts from the convents show, were very familiar with the procedure.

Fig. 35 Bloodletting among the pictures representing each month in the Wienhausen nuns’ choir. Photograph: Ulrich Loeper ©Kloster Wienhausen.

Between the Transcendent and the Temporal

The depictions of the months formed the appropriate interface between the nuns’ choir and the parish church. Here the sequence of the calendar with its practical activities met the transcendence of temporal order as represented in the nuns’ choir. The nuns were part of both worlds: that of the history of salvation, its structure transcending time, in which they already participated as brides of Christ; and the seasonally recurrent structure of sowing and harvesting, pruning and healing. This is particularly clear in the picture that can still be found today above the door in the north-east corner of the nuns’ choir, through which the nuns left the sacred space again after divine office.

In the transverse rectangular field, two six-winged cherubs on the left and right stand sentinel over an architectural ensemble which looks as if it were projected onto a wall fortified by crenelations. A blank speech scroll hovers above the gables. The group of buildings displays a characteristic profile: above the lower buildings at the front rises a storehouse with numerous door and window hatches in the triangular stepped gable. It boasts a small, round staircase tower and stands at right angles to another building complex marked by a ridge turret as a church building. The tracts of high Gothic windows in the upper section indicate that this is a more modern building than the lower part with the round windows which adjoins it on the right. This description also accurately reflects the view of Kloster Wienhausen from the south today, right down to the relationship between the Gothic nuns’ choir, which towers over everything else, sits above the parish church and rises far above the older east section.

Fig. 36 Wall painting in the Wienhausen nuns’ choir. Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis ©Kloster Wienhausen.

Fig. 37 View of Wienhausen from the south. Photograph: Wolfgang Brandis ©Kloster Wienhausen.

The painting from the 1330s is thus not only the oldest depiction of Wienhausen, but above all a multilayered and highly symbolic interpretation of the meaning and purpose of convent life. When they were in the nuns’ choir with its tracts of high Gothic windows, the nuns saw themselves already absorbed into the future joy of heavenly Jerusalem, which had been promised to them when they were crowned as nuns. Convent life is shut off from the world by the enclosure walls, but open towards heaven.

The nuns knew full well that illness and death formed an inseparable part of life because they constantly reflected on them in meditation and in song. Unlike in modern society, illness and death were not pushed to the margins: dealing and coping with death and grief were a communal task to which nuns devoted a great deal of their energy. Communal singing played a decisive role in this, connecting them with both the living and the dead in their invocation in the liturgy of the divine sphere and the closeness to Christ. In this spiritual understanding, knowledge of the connection between life and death opened up deeper aspects of what it is to be human, which – as not least the Lüne letters reveal – were experienced as very comforting, with the result that many lay people sought proximity to the nuns and their community. In this respect, the nuns constituted an entirely independent force and strong voice within medieval society. Even though history has often overwritten or erased their cloistered lives and we barely seem to hear their voices today, in their own time they were by no means invisible or inaudible; and when they had to defend their own cause they could also become outrageously obstreperous. By their heavenly bridegroom Christ – of this they were firmly convinced – they were heard and exalted.