1. A Swedish Perspective on Artistic Research Practices in First and Second Cycle Education in Music

© 2024 Stefan Östersjö et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0398.02

Introduction

This chapter seeks an understanding of the ways in which practices of artistic research are contributing to the development of the teaching and learning of music performance in Higher Music Education (HME). It is built on the authors’ long-term experience of teaching artistic research methods and supervising theses in first and second cycle programmes in Sweden. First, we provide a brief historical overview of how artistic research in music was implemented in Sweden, with particular attention to knowledge claims and method development.1 Second, we consider the impact of the Bologna process on HME in Sweden, a process in which the authors have been personally involved. It has, among other things, demanded a shift from teacher-driven provision toward ‘student-centred higher education’.2 The third section is the most substantial, and first outlines the role of the thesis project in the bachelor’s and master’s programmes in the Piteå School of Music, at Luleå University of Technology (LTU), and the courses that prepare students to undertake thesis projects. We present an overarching qualitative and quantitative analysis of completed theses from 2020–2022 with regard to aims, research questions, and methods. For each of the six identified categories, one thesis was selected for a more detailed qualitative analysis. Finally, each of these six students was interviewed. Hereby, the central material of the chapter is constituted of student voices, the experience manifested in their thesis projects as well as their retrospective reflections on the role of the projects in their individual artistic development, as expressed in individual interviews carried out by the authors.

Artistic Research in Sweden

Artistic research was implemented in the early 2000s in Sweden, with the first PhD students employed in 2002.3 A fundamental characteristic of artistic research in the country has been a consistent focus on artistic excellence, as expressed by Gertrud Sandqvist, ‘artistic-research education should be given to artists who have a well-developed practice of their own’.4 This approach generated a set of highly independent PhD projects with a firm grounding in their respective art worlds,5 carried out by artists who sought means for challenging their individual practices and creating a wider understanding of their role. As further argued by Sandqvist, the rationale for this approach was that only when they have fully ‘mastered their own artistic projects can artists decide which methods they need in order to develop the specific parts of their artistic projects that are oriented towards the production of new knowledge’.6 Hence, while the point of departure was the qualities of the individual artistic practice of the PhD student, the further aim would always be to ‘produce a new kind of information that is not introspective but combinative, outward-looking and seeking new connections’.7 The first Swedish PhD theses in artistic research in music were defended in 2008, and the past ten years have given clear indications of an increasing maturity in the field, with stronger research environments, and also, as argued by Lundström, with projects ‘increasingly conducted by research groups or research teams that often involve more than one university and more than one discipline’.8

Although a comprehensive analysis of the methods and practices developed in the field of artistic research in Europe across the past twenty years is still lacking, it is clear that one important feature is the application of reflexive methods in artistic projects.9 For instance, Darla Crispin, observes how, in artistic research, ‘attention has increasingly turned to ways in which auto-ethnography and self-reflexivity can continue to be developed as viable approaches to conducting musical research’.10 From the perspective of other research domains, in which autoethnography has become an important vehicle, Bartleet observes how

autoethnography and artistic research have enjoyed a dynamic relationship—the former enabling the latter, and the latter fuelling the former, and both have found themselves privileging the subjectivity of the artist-researcher, the materiality of the researcher’s body, and the intersubjectivities that emerge through the researcher’s artistic encounters with the world.11

Crispin further notes how the method development in artistic research ‘has become concomitant with innovations around musical language and notions concerning its “truth content”’.12 At the same time, Crispin observes how the outcomes of artistic research also have ‘been a driving force behind various innovations in art-making’.13 Hence, professional artists, carrying out artistic research using reflexive methods have demonstrated substantial impact on the development of their individual research projects. Another factor, common to these projects, is the role of artistic experimentation, as a means for challenging the individual practice of the researcher.14 Of particular interest for the purposes of the present chapter is however whether the methods and practices of artistic research have indeed also affected the teaching and learning in HME.

In a recent article, Karin Johansson and Eva Georgii-Hemming argue that ‘[i]n Sweden, the artistic PhD degree has established artistic research as the main way of enquiry for developing new knowledge in the field of music’;15 and they make the further claim that this has laid the grounds for creating formats for a research-based education, a perspective which will be further examined in the next section. They also find that reflection has constituted a basis for the introduction of research-based methods, and Georgii-Hemming, Johansson, and Nadia Moberg note how ‘teachers and leaders [in HME] view reflection as a method for students’ self-improvement as the students develop written and oral skills by which they can document and consider their performances and artistic development’.16 In the following section, we will further examine the results of their large-scale comprehensive study, as a part of outlining the curriculum development in HME in Sweden, largely built on the process launched by the Bologna agreement.17

The Bologna Process and HME in Sweden

As indicated in a recent literature review, instrumental teaching and learning in HME have been reported as largely based on the master–apprentice model.18 However, the way in which this model is implemented has been found to be in direct conflict with three of the changes that the Bologna process entailed, since such education should be research-based, use student-centred teaching models aiming to activate students in their learning, and aim for students’ lifelong learning (i.e., emphasise the need for generalisation and transfer of learning, and meta-cognitive aspects such as learning of learning). Although no specific requirements for music are given in Swedish legislation,19 students shall, for a degree of bachelor of fine arts, demonstrate abilities including autonomously identifying, formulating, and solving artistic and creative problems; making assessments informed by relevant artistic, social, and ethical issues; and identifying their need for further knowledge and taking responsibility for their learning.20 Second-cycle education shall, in addition, further develop students’ ability to integrate and make use of their knowledge and students’ potential for professional activities or research that demand considerable autonomy.21 Thus, based on these formulations, artistic education in music post-Bologna shall be research-based, student-centred, and develop students’ capacity for lifelong learning.

The research project ‘Discourses of Academization and the Music Profession in Higher Music Education’ (DAPHME, 2016–2018), sought a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the Bologna process on artistic education in music in Europe. Hence, the outcomes of the Swedish study within the DAPHME project constitute a central reference regarding the implementation of the Bologna process in HME in Sweden. A major portion of papers from the Swedish study within the DAPHME project are based on interviews with teachers and leaders in HME. For instance, Johansson and Georgii-Hemming cite extensively from their informants, who generally describe the establishment of artistic research as a decisive factor for the renewal of the degree project in music performance in HME.22 It is argued that practices from artistic research have demonstrated how ‘to integrate reflective and artistic activities, and how to document and present research in multimodal formats’.23 Furthermore, informants observe how the degree projects are not typically designed to conform with ‘ready-made forms and stereotypes’ but ‘are both conventional and experimental, they cross borders and investigate new things’.24

To summarize the outcomes of the Swedish part of the DAPHME project, the leaders and teachers in HME were found to use four types of justifications for including reflection in artistic programmes in music. First, reflection was described as having the ability to enable students to take individual responsibility for their artistic development.25 Second, reflection was viewed as a tool for personal branding and expanding musicians’ capacity to verbally communicate about their performances.26 Third, it was described as a tool that enables musicians to situate themselves, and that may produce musicians ‘who have a voice’.27 And, finally, reflections were found to show ‘potential to develop the common professional field of knowledge’.28

While Johansson and Georgii-Hemming emphasise that the degree project was ‘initially much debated’,29 their study confirms our impression that, in Swedish HME, the degree project, built on artistic research practices and methods, has become an integrated building block in the curricula in all teaching institutions. Furthermore, their study also proposes that the use of reflexive methods is a typical feature of these practices, as discussed and problematized by Crispin.30

In a recent article, Moberg31 makes contrasting observations drawn from a qualitative content analysis, followed by a discourse analysis, of finished master’s thesis projects. She puts forth a more critical view on the implementation of reflexive methods in second-cycle degree projects, claiming that ‘sought-after practices within HME such as critical thinking, reflection, reflexivity and metacognitive engagement […] are conspicuous by their absence’.32 Moberg further claims that ‘theses reproduce music as an object independent of social and political concerns along with practitioner preoccupation with the self in search of individual advancement’, arguing that such a point of departure in individual artistic practice entails that ‘arguments beyond the self are rendered redundant’.33 However, in the method description, Moberg describes how her analysis ‘focused on purpose formulations and/or research questions (or sections serving a similar function) and justifications for the theses’.34 Thus, it is unclear how claims can be made regarding the students’ abilities to contextualise their practice, since the study is explicitly limited to the purpose formulations, research questions, or ‘sections serving a similar function’.35 Throughout this chapter, we will seek a deeper understanding of the role of reflexive methods and how the degree project may, indeed, promote critical thinking and the ability to situate artistic practice in wider socio-cultural contexts. We note how the study of artistic learning processes is challenging when it comes to the collection and analysis of data.

Description of Programmes in the Piteå School of Music

The three-year bachelor programme in music, as well as the two-year master’s, have been given at the Piteå School of Music since 2007. The programmes have, since the beginning, been constructed with a clear progression with the student’s degree project in mind. The overarching aim has been to identify each student’s individually experienced artistic possibilities, challenges, and motivations, in order to involve both student and teachers in the design of the studies. Hereby, the degree project should be an integrated and central component in the artistic development of the student. The design also aims to develop student autonomy and reflexivity, an objective which is addressed in the introductory courses, in which students are taught critical thinking and reflexive methods, based on practices of artistic research.36

|

Bachelor |

Master |

|

The Research Process (7.5 credits) |

Artistic research processes: theory and method (15 credits) |

|

Degree project (15 credits) |

Degree Project (30 credits) |

Table 1.1. The basic design of introductory courses and degree projects in the bachelor’s and master’s programmes in Music Performance at Piteå School of Music, Luleå University of Technology (LTU).37

In Table 1.1, the upper row refers to the introductory courses in both programmes, each of which leads to the formulation of a project plan for the thesis project to follow (as listed in the second row). The introductory course in the bachelor’s programme is carried out in the spring of the second year, with the course stretching across the entire term. Similarly, the 15-credit thesis project stretches across the entire third year. A seminar at a 70% milestone is held in March and a final seminar in May, followed by an examination wherein both the artistic outcomes and the written submission are discussed and assessed as a whole.

In the master’s programme, the introductory course stretches across the entire first year. The degree project is carried out in the second year, although many students start their thesis project with a pilot study, which concludes the first term of the first year. Thereby, the thesis work can extend across three terms, occupying more or less the entire duration of the studies. In the master’s thesis course, there are part-time seminars at 40% and 70% milestones, followed by a final seminar in May. As in the bachelor course, the final examination of the thesis takes place after the final seminar.

Design of the Study

This chapter builds on a study of the role of the thesis project in the Piteå School of Music, in which the authors have been directly involved as teachers, supervisors, and examiners. The greater part of the study is concerned with the documented outcomes of the students’ independent degree projects. Since the courses for both artistic research methods and theories, as well as the thesis project itself, have been in constant development, we decided to focus this study on the theses produced in 2020–2022.

The study consisted of five main parts: first, a preliminary qualitative content analysis of the bachelor’s (n = 56) and master’s theses (n = 11); second, a quantitative analysis of selected key words in the theses; third, a qualitative analysis of aims and research questions serving to validate the analysis in the two previous stages; fourth, for each of the categories identified in the first qualitative analysis, one student thesis was selected subjected to a closer study; and fifth, we interviewed the students whose theses we had analysed, asking them to provide feedback on our analysis of their project and asked additional questions regarding how they had experienced their artistic education and how they had experienced the role of the degree project in their studies. In sum, the design of the study has sought to provide insights regarding the implementation of artistic research practices in the students’ theses project and to foreground students’ own accounts, both through their written publications and through interviews.

Preliminary Qualitative Content Analysis

We first approached the data through a qualitative content analysis38 based on a summative reading of all the theses from 2020 to 2022, aiming to identify overarching topics and methods used. This initial step in the research design is similar to the study by Moberg mentioned above, in which a qualitative content analysis of 266 master’s theses with ‘a classical music orientation’ from three institutions for higher music education in Sweden 2013–2020 was carried out.39 Our analysis led to a preliminary set of six categories in which the student projects could be structured:

- ‘Collaborative Practices and Ensemble Interaction’

- ‘Interpretation, Expression, and Voice’

- ‘Performer-Instrument Interactions’

- ‘Rehearsal and Efficient Practising’

- ‘Musical Gesture in Performance and Conducting’

- ‘Performance Anxiety’

It should be noted that several of these categories are closely linked. ‘Performer-Instrument Interactions’, ‘Rehearsal and Efficient Practising’, and ‘Musical Gesture in Performance and Conducting’ all build on the embodied interactions between performers and instruments. Moberg’s findings have many similarities, wherein more than half of the theses were concerned with the following seven topics: technique and expression (12.8%); musical works and composers (10.2%); interpretation (9%); auditions and competitions (8.6%); mental health and preparation (6.8%); arranging, composing, and improvisation (4.5%); and practice (4.5).40 Our impression was that the outcomes of the content analysis were less precise than we had wished for, a concern which appears to be relevant also for the similar type of categorisations found in Moberg’s paper.

Quantitative Analysis of Student Theses

After the preliminary qualitative thematic analysis, we sought a wider understanding of the findings by conducting a quantitative content analysis41 using automated bash scripts. Hereby, we examined the frequency of 40 selected keywords, relating to the methods used in all bachelor’s (n = 56) and master’s (n = 11) theses (in total, n = 67). In the search, we set the threshold for inclusion at three occurrences of the respective search term, striving to filter out theses making only passing mention of the terms. The theses were written in either Swedish or English; therefore, parallel searches were made in both languages.

The raw output from the searches of the selected keywords was then inserted into a spreadsheet, where the data was further analysed. Two general observations were made: first, the term ‘process’ is mentioned in almost all bachelor’s and all master’s theses, typically always with reference to a description or discussion of the individual artistic process, hence indicating that this aspect of artistic research practice has had a prominent role in the inquiry. Second, the term ’reflection’ (and the Swedish ‘reflektion’), although occurring in some of the bachelor’s theses, is substantively more common in master’s theses, thus possibly indicating the advanced students’ higher level of metacognitive awareness, or at least suggesting a greater ability to conceptualise their learning process.

The analysis of methods confirmed some expected patterns, wherein projects addressing aspects of performance typically employed both audio and/or video for the documentation of artistic process, while projects related to composition and related practices would focus more on other modes of documentation. An increase in the use of video documentation was noted among master’s projects. The use of logbooks was found more frequently in bachelor’s than in master’s theses. Interviews were also used by students in both programmes, however more frequently in the master’s theses. Furthermore, in some master’s theses, stimulated-recall analysis was used, indicating an increased interest in achieving intersubjective understanding. Moreover, a tendency was found that the combination of ‘interview’ and ‘teacher’ was more frequent in master’s theses, possibly indicating that the students’ regular teachers had had a more substantial involvement in these projects, an observation that we will return to below.

Qualitative Analysis of Aims and Research Questions

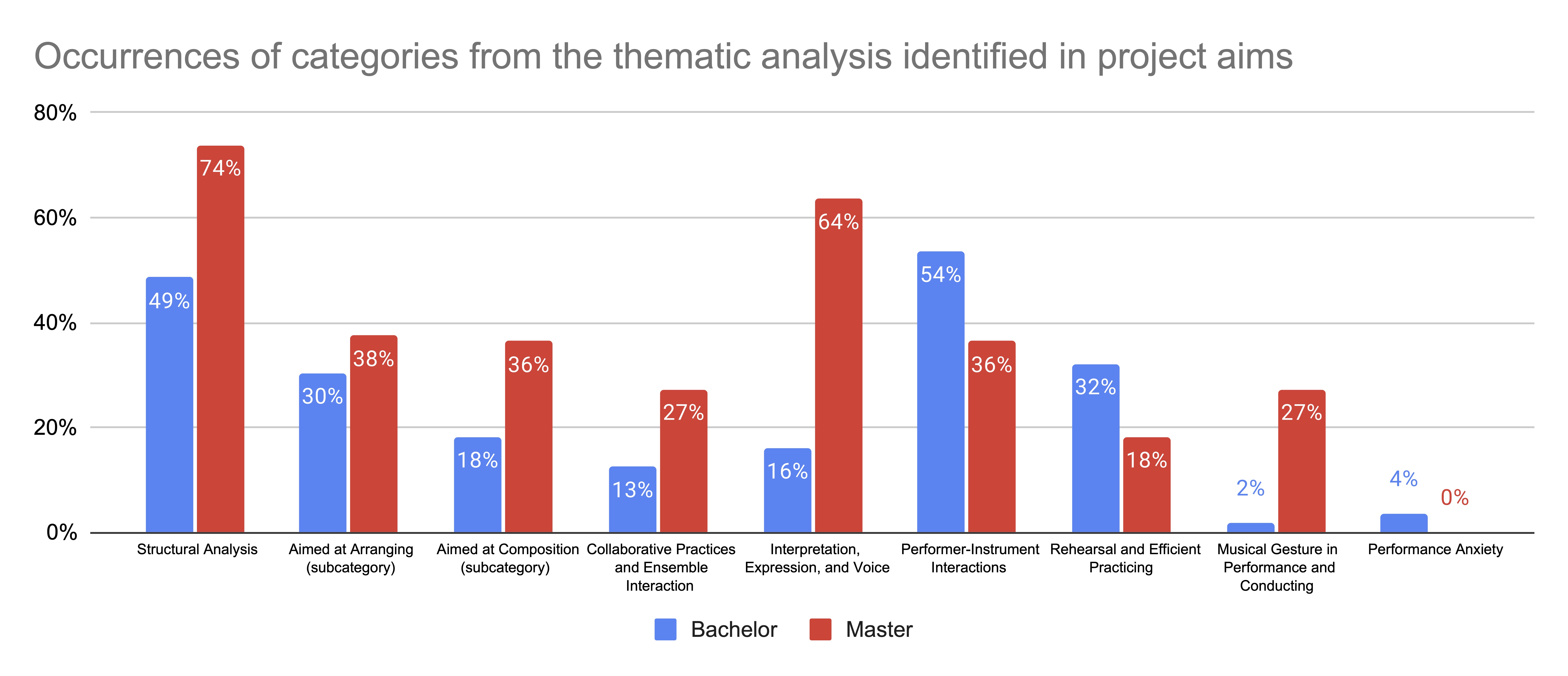

In order to obtain a deeper understanding of the data, a further qualitative analysis of all the studied theses’ aims and research questions was carried out, which entailed identifying central categories, beyond those found in the first analysis. The findings were triangulated against these six categories, and the number of occurrences was quantified, allowing more than one category for each thesis.

This analytical process indicated clearly that the initially identified category of ’Performance Anxiety’ was not relevant, since the phrase occurred only twice in bachelor’s theses (see Fig. 1.1). At the same time, an additional category, labelled as ‘Structural Analysis Aimed at Arranging or Composition’, was found to be quite central as it occurred in 49% of the bachelor’s theses and in 74% of the master’s theses. Furthermore, we found that this category could be subdivided into projects that either sought to develop skills in arranging or in composition. It should be noted that ‘arranging’ here refers to a wide range of skills, often related to either individual performance or to studio production.42 Additionally, some projects also referred to ‘structural analysis’ but as an aspect of musical ‘interpretation’, and are hence found in that category (see, further, Fig. 1.1).

The excluded category of ‘Performance Anxiety’ is a topic that has tended to recur across institutions in Sweden, in particular among students in classical music performance, as evidenced in Moberg who reports that 6.8% of the analysed master’s theses falls within this category.43 It is beyond the scope of the present chapter to discuss this phenomenon,44 but it does suggest that there are issues with psychological well-being among classical music students. Notably, in the present study, very few occurrences of Music Performance Anxiety-related topics were found, instead leaving space for projects exploring musical performance as creative practice.

The final six categories found in the analysis of aims and research questions were:

- ‘Structural Analysis Aimed at Arranging or Composition’ (49% bachelor, 74% master).

- ‘Collaborative Practices and Ensemble Interaction’ (13% bachelor, 27% master) where the focus is on the interaction between performers, as well as between performer and composer (more prominent within master’s theses).

- ‘Interpretation, Expression, and Voice’, denotes projects which sought to develop students’ personal musicianship, striving to form their own musical identity as performers (16% bachelor, 64% master).

- ‘Performer-Instrument Interactions’ focused on the performers’ relation to their instrument and how this could be developed to meet their artistic goals (54% bachelor, 36% master).

- ‘Rehearsal and Efficient Practising’ denotes theses that sought to develop more efficient ways of practising (mostly bachelor) and rehearsing (32% bachelor, 18% master)

- ‘Musical Gesture in Performance and Conducting’, are projects studying and exploring gestures in performance and conducting (2% bachelor, 27% master)

Fig. 1.1: A proportional representation of occurrences of the most prevalent categories in the qualitative content analysis.

Qualitative Analysis of Method and Design — a Closer Study of One Student Thesis per Category

For each of the six categories identified above (see Fig. 1.1), one student thesis was selected and subjected to a closer study. Our ambition has been to give voice to each student and, thereby, prioritise direct quotations.45 Furthermore, we also interviewed the students whose theses we had analysed, asking them to provide feedback on our analysis of their thesis also posing additional questions regarding how they had experienced their artistic education as well as the role of the degree project in their studies. The authors translated all Swedish quotes, and the originals are presented in the footnotes.

Structural Analysis Aimed at Arranging or Composition

The use of structural analysis to explore and develop practices of musical composition is a category which is commonly found both in bachelor- and master-level theses. We will, in the following, look at the master’s thesis by Robin Lilja, which explores a particular method for algorithmic composition, using what he calls ‘constraint-based patterns’.46 This method sought to develop conditions for creating a convincing balance between contrast and coherence across musical parameters in a musical composition, an objective previously explored through a similar composition method within the frames of Lilja’s bachelor’s thesis project.47 According to the aims of the project, the ‘achieved contrasts should be apparent in multiple parameters, but the overall musical structure should still maintain some form of coherence’, and the project was built on the hypothesis that ‘the sequential nature of the contrasts within the constraint-based patterns should contribute to the desired level of coherence’.48

In the literature study, the writings of Gerhard Nierhaus were a central reference, and, in order to further substantiate the project’s relation to research on algorithmic composition, Lilja followed two courses at Kunst Universität Graz (KUG), Nierhaus’s home university.49 The fundamental method of the project is described as artistic experimentation, and, to capture the outcome of this practice, two main methods were used to document the author’s individual process: a structured logbook and the use of verbal annotations in the finished score, both contributing to capturing moments of decision-making. The analytical approach, however, was not merely an assessment of the artistic outcomes of the composition method, as experienced from a first-person perspective. A further perspective was provided through the collection of different forms of feedback from listeners. Such third-person perspectives on the artistic outcomes were drawn from differently designed focus-group interviews (which always included a full screening of a particular piece, typically a concert recording from the premiere). In these sessions, informants were selected according to the criteria that they have no knowledge with regard to the method used for the composition of the music. A different category of feedback was drawn from teachers and fellow composition students, whose feedback built on both listening and reading the score (most typically, drafts derived in the process of artistic experimentation). In the final discussion, Lilja concludes that both types of responses were useful, but the feedback from the more informed listeners provided valuable input in the creative process, identifying artistic challenges, issues, and potential. At the same time, it is interesting to note how it became difficult for Lilja to tell whether a perceived increase of coherence in the music was due to revisions in the score or if it was related to a particular listener becoming accustomed to the style of the music.50 In an interview carried out in December 2022, Lilja further reflects on the role of feedback in relation to lifelong learning and notes how:

While it might go without saying, I want to state the importance of the teachers, supervisors, and peers in the process of ‘becoming your own teacher’. Their comments during feedback will echo in my head as I grow, and I will ask myself ‘what would my teacher/supervisor/peer have said?’51

In the discussion, much emphasis is given to the relation between complexity in input and output. For example, in the section addressing the creation of the orchestral piece, Lilja explains that he eventually decided to use ‘a simpler algorithm for a more complex result’.52 Similar observations constitute the general response to the aim of the project: to explore how the use of the constraint-based patterns may shape the relation between coherence and contrast. In the final discussion, Lilja observes how:

The greater the amount of composition parameters which are controlled through constraint-based patterns, the simpler each individual composition parameter has to be in order to reach contrasting results that I find satisfying. In other words: when the interference patterns of the multiple composition parameters become more complex, the less complex each individual parameter needs to be for the result to be interesting. What is truly delightful, is that this means that you can have high coherence in each individual parameter […] while the resulting interference pattern provides high contrast.53

Another recurring topic is the role of intuition in the compositional process and its relation to the compositional constraints. In his conclusion, Lilja reflects on how there is always more to be learnt with regard to the potential of the system he created, observing how ‘satisfaction is never reached, and therein lies the beauty’.54 In reflecting on the thesis project as a whole, Lilja notes how, ‘[i]n artistic endeavours we make a lot of choices, and artistic research is where we explain why we made these choices—to the extent that someone else can understand and learn from them’.55 In the final analysis, therefore, Lilja’s degree project appears to have provided tools for lifelong learning and an awareness of how such learning is dependent on interaction with others.

Collaborative Practices and Ensemble Interaction

The category of ‘Collaborative Practices and Ensemble Interaction’ was more prominent in master’s theses compared to in the bachelor’s in our study. One example is the project of jazz-pianist Ester Mellberg entitled ‘A partner at the piano: Expanding musical and performative expressions in a duo with a vocalist’.56 This thesis project was carried out through the study of an already existing duo: Mellberg and the vocalist Sofie Andersson. Andersson was a student in the same programme and, interestingly, her degree project was also a study of their collaboration, but more from her perspective as a vocalist.57 Hence, artistic collaboration not only constituted the object of study, but it was also the artistic method through which two independent theses were eventually produced. Mellberg situates her project in a research context with reference to the work of Vera John-Steiner58 but also through specific studies in artistic research in music, looking at how a shared voice can be developed through artistic collaboration.59 In an interview with Mellberg, she claims that the combined collaborative perspectives facilitated different learning processes. She describes how, at times, the members of the duo were ‘becoming each other’s supervisors, and thus also our own’.60

For Mellberg, the personal motivation for the project lay in her relation to her instrument, the piano. She experienced how ‘the link between expressing something and the practice of piano performance are separated in the teaching, at least in my genre’.61 She describes how she had learnt ‘a lot of crafts such as music theory, chords and scales and how to use them for improvisation’. However, the issue that she wished to address was the experience of having ‘rarely practised the use of the crafts or improvisation in an expressive way. One practises techniques to play fast, loud or to understand complex harmonies but forget the part where to use the crafts to express something’.62 Hence, Mellberg’s research aim was to deepen her ‘understanding of what it means to be an expressive and interactive pianist and expand those skills in duo performance with a vocalist’.63 The project emerged in collaboration with Andersson as they created arrangements of three songs, recorded them, and analysed their interactions and the emergence of joint expression.

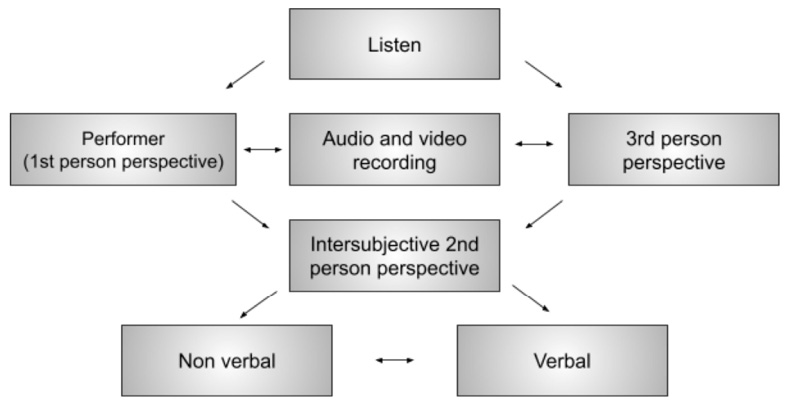

To efficiently address the artistic processes that emerged through the collaboration, video and audio documentation was employed. This data was analysed through the use of stimulated recall,64 motivated by the pianist’s wish to create a joint understanding of the developing practice, together with the singer. A flowchart drawn from Mellberg’s thesis describes how this method formed part of the artistic process (see Fig. 1.2). In discussing the choice of methods, Mellberg observes how ‘[s]timulated recall has been used both as we have created our arrangements and also to analyse the outcome of our recordings. While creating arrangements we have used stimulated recall to get a 3rd person perspective of our musical interpretation’.65 Thereby,

we can give ourselves constructive criticism and make the changes we need to reach the intended expression. […] Using stimulated recall interspersed with open coding has been a great way of reaching a deeper understanding of the knowledge we have gained through this project, and also the knowledge we already possessed.66

In the final analysis, they used a model of performer’s voice, based on embodied music cognition, with particular interest in how a shared voice can emerge through the blending of individual voices.

Fig. 1.2: A flowchart of the interaction between Mellberg and Andersson through the use of stimulated recall analysis.67

When reflecting on the role of the thesis project within their studies, Mellberg observes how it

was by far the most important for us. [...] It created a clear direction, a clear focus and a goal to aim for. Both Sofie [Andersson] and I were completely invested in the work, and we became better at reflecting, deepening our understanding and thinking in several steps.68

The full project can perhaps only be understood by a reading of the two theses, but in our interview with Mellberg, she concludes that, for her, the project had most of all contributed to developing greater ‘autonomy and self-confidence’.69

Interpretation, Expression, and Voice

The category of ‘Interpretation, Expression, and Voice’ was the second most prominent among master’s thesis projects but was much less common in the bachelor’s theses. In Simon Perčič’s master’s thesis ‘Temporal Shaping: A conductor’s exploration of tempo and its modifications in Weber’s Der Freischütz Overture’,70 the aim was to explore the historical ‘conception of “tempo modification” and its overall relevance in the temporal shaping of music in orchestral conducting’.71 While this entailed a study of historical performance practice, further aims were to relate tempo modification to present-day conventions and to explore tempo modification through Perčič’s own practice as an orchestral conductor, thus providing important insights into the development of a musical interpretation.

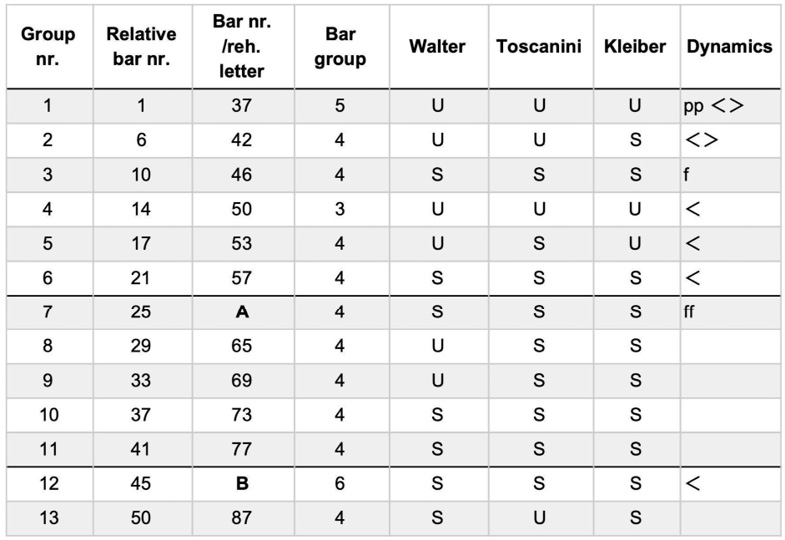

Tempo modification as a historical practice was researched through a multi-method design consisting of a literature study, an in-depth interview with the composer Marko Mihevc, and, finally, through analysis of recordings by Toscanini, Walter, and Kleiber. The study focused on the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz, first through a detailed study of historical recordings of the piece and, second, through a similar study of recordings of two different performances conducted by Perčič. The historical analysis suggested that tempo modification has become less of a common practice, as indicated in Table 1.2 below in the decreasing number of occurrences of unstable bar groups in the performances by Walter (6), Toscanini (4), and Kleiber (3), represented here in chronological order. Another artistic method was to develop approaches to score reduction, and an entire chapter is dedicated to a description of this process, which encompassed the two years of the degree project. In this, Perčič sought to ‘extract the balance and structural development, which constitute a firm ground for tempo nuancing’.72

Table 1.2. Der Freischütz; stable (S) and unstable (U) bar groups, drawn from Perčič, 2020, p. 26.

Although the study of historical practices of tempo modification lays the ground for the entire thesis, the core results are drawn from the analysis of Perčič’s practice as a conductor. The first performance of Weber’s Der Freischütz Overture was carried out with the Norrlandsoperan Symphony Orchestra. The second performance, scheduled with The Gävle Symphony Orchestra, was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic and substituted by a rehearsal and recording of the piece in a version for two pianists. This makeshift solution provided both limitations and a potential for further experimentation. The comparative audio analysis identified no ‘unstable’ bar-groupings in Perčič’s first recording (as compared to the findings represented in Table 1.2) but four in the second version. Importantly, Perčič also highlights the deepened interaction between conductor and performers in the later version, a feature which appears to have strongly contributed to their exploration of the phenomenon of tempo modification.

In an interview carried out in January 2023, Perčič reflects on the thesis project and notes how ‘it addresses an issue that cannot be solved immediately, but needs to be explored from within—we could find an analogy in organic development—an approach that goes from the inside out’.73 The embodiment and subjectivity of the student are therefore integrated in the learning process in ways that are central to artistic research practices.

In the concluding discussion, the combination of methods in the project are considered in relation to conventional forms of teaching in HME. Perčič suggests that research-based approaches have the potential to enable ‘a more detailed understanding of the potential in conducting’74 and, further, proposes that different pedagogies could be developed by defining

what skills are best taught in a master-apprentice way, and what skills could be further developed through the use of scientific approaches and novel forms of teaching, that encourage independence and personal judgement. Learning conducting is more often than not connected with master-apprentice way of knowledge passing, therefore, I would argue, building new knowledge, using technologies, research papers and especially experimental testing is from my point of view the way forward.75

Building on these ideas, in the interview, Perčič describes the thesis project as providing ‘a basic tool for thinking about your own daily learning – a kind of resilience generator’.76 Hence, this thesis not only provides an account of individual artistic development and how a historical study of performance practice can contribute to developing individual approaches to musical interpretation, but, also, it reflects on how this learning process may inform the development of pedagogical approaches to the teaching and learning of music performance.

Performer–Instrument Interactions

The fourth category addresses ‘Performer-Instrument Interactions’. As an example of this category, we will look at the bachelor’s thesis of jazz drummer Jakob Sundell entitled ‘The Drum Also Sings: A study exploring playing tonal melody on the jazz drum set’.77 When he introduces what sparked his ideas for this project, he writes ‘I would like the melodical [sic] expression of the drum set to be a natural part of my musicianship. The aim has been for me as a musician to be able to use rhythm, phrasing, melody and harmony just like any other instrumentalist’.78 Thus, Sundell’s thesis is an example of how explorative approaches to the relation between performer and instrument can give rise to expanded possibilities and novel modes of expression.

Literature studies were a considered part of the project design, providing a historical outline of the development of melodic drumming in jazz. This also entailed an interest in how the modern drum kit evolved, identifying a direct connection between the modified setup and the emergence of melodic drumming in the 1960s in the playing of Max Roach and Art Blakey. Another fundamental reference is the work of the drummer Ari Hoenig, whose approach to tuning the drumkit, and techniques for modifying pitch, are adopted by Sundell.

The project was structured as an iterative cycle consisting of four steps. Practicing was the first step, which entailed testing different tunings for a number of jazz standards and devising techniques for modifying the pitch of individual drums while playing. The second step was to make studio recordings with a full group. Thirdly, feedback sessions on these recordings were held with peers, teachers, and other established musicians. Fourth and finally, Sundell undertook an analysis of the recordings, which was to a great extent focused on the playing techniques and tuning systems devised for the drum kit. Comparing this cycle with how Paulo de Assis79 conceives of experimentation in artistic research—as integrated in cyclical processes intertwined with other forms of knowledge construction—we find interesting how the first step in Sundell’s cycle could be better described as artistic experimentation. Furthermore, the component of feedback from teachers and peers differentiates his model from that of Assis, providing a stronger focus on the learning processes. This step in the explorative cycle seems very fruitful in a bachelor’s thesis project and also establishes a more dynamic relation between student and teacher.

The discussion is largely focused on technical aspects of the experimentation carried out in the first step, such as how to tune the drums and manage the melodic intonation. It also covers the setup itself, including drumheads but also the choice of striking implements. Taken together, the approach developed in the project entails a redefinition of the drum kit, demanding a new practice and also affording a series of musical challenges.80 Sundell notes that there are, indeed, parts of melodic improvisation on other instruments that are transferable to the drum set,

such as phrasing, tension and release, call and response and melodic contour. But the melodic content in tonal improvisation is not. The drum set can be able to play improvisational lines based on scales. For this to happen the intonation and melodic intention has to be of high precision.81

Reflecting back on the thesis project, Sundell notices that: ‘I became fully aware of my musical ability and weaknesses and what I needed to do to come closer to my goal’.82 Sundell further observes how this was ‘the point at which the studies went from being instructive to constructive’ and that the students were invited to ‘generate their own knowledge through the process of the thesis course’.83 To conclude, Sundell expresses how his exploration of the ‘melodic possibilities of the drum set’ has given rise to a novel awareness of a ‘target sound’, which is a characteristic of a personal ‘musical voice’, and also provided new and more goal-directed methods for artistic development.84

Rehearsal and Efficient Practising

Many students decide to focus their degree project on developing or testing techniques for efficient rehearsal and practising. Such projects demand a thorough design for assessing the outcomes of such experimentation with the embodied practice of performance. Sara Hernandez, in her bachelor’s thesis ’Fiolen i kvinter: En ny metod att hitta en handställning som förbättrar intonationen’ (’The Violin in Fifths: A novel method for finding a hand position that improves intonation’), provides a convincing example of how such work can be carried out and assessed.85 Her thesis starts out by acknowledging the complexity of obtaining good intonation on the violin, which, apart from developing one’s listening, involves a practice deeply embodied in the performers’ left-hand technique. Hernandez points to how the many aspects of left-hand technique have been previously explored by Schradieck, Flesch, and Sevcik. However, her project is built on the novel approach proposed by the violinist Rodney Friend, which seeks to develop a better left-hand position with a grounding in the performance of fifths, and how this enables the development of a better left-hand technique with the further aim of improving intonation. Her project follows the meticulous process of testing these exercises and applying them in the study of two pieces: the fugue from Bach’s first violin sonata in G minor, BWV 1001, and the first movement of Samuel Barber’s violin concerto, Op. 14. To assess potential progress in the development of technical skills, a sufficient time span is necessary. The first documentation was, therefore, carried out in March 2021, with audio recordings of selected exercises from Friend’s method86. After using this practice method for a year, the same exercises were recorded again in April 2022. Sections in Bach’s fugue and Barber’s concerto that were found to be particularly challenging in terms of intonation were selected and recorded within the same time span as designed for the selected exercises. In the thesis, Hernandez provides detailed examples of how these sections were prepared in several steps, by applying technical exercises built on fifths, according to Friend’s method. Effectively, these examples also provide an analytical parsing of the challenges to the left-hand technique in each sequence.

An interesting feature of Hernandez’s project design is the use of a reference group of two fellow students and one teacher, who were invited to listen to recordings of both technical exercises and rehearsal performances of the two works, grading the quality of the intonation on a scale from 1 to 5. Hernandez also carried out the same grading process as the reference group. The outcome of the project is clearly expressed in the assessment of the recordings, wherein the judgement is quite unanimous in all cases, generally shifting from 2 to 4 in the comparison between March 2021 and April 2022. The development and application of methods for practising and rehearsal in the study of music performance are a major contribution of this thesis. Hereby, the project indicates that basic skills can be efficiently developed through an individual degree project, if the project design is efficient and purposeful.

In an interview, Hernandez observed how her writing had ‘encouraged reflection, since I’ve had to analyse and observe my playing from an outside perspective, in ways that were new to me. Writing about it has helped me articulate and understand myself better as a musician’.87 Hence, the tasks of documenting and analysing her practising not only contributed to the learning process but also had been directly intertwined with and enhanced through the writing process. In a further reflection on the impact of the thesis project in her studies as a whole, Hernandez concludes that

the project has been an exercise in looking at oneself from outside with new eyes – the eyes of a teacher. To make recordings and evaluate before and after practising gives an incredible amount of insight and information into one’s own playing’.88

To conclude, an important contribution of this thesis project may ultimately lie in how the combination of methods have contributed to further developing the student’s capacity for autonomous learning.

Musical Gesture in Performance and Conducting

The final thematic category is ‘Musical Gesture in Performance and Conducting’, exemplified here by the master’s thesis ‘Meaningless Movement or Essential Expression: A study about gestures’ by the clarinettist Stina Bohlin.89 She describes how the idea of studying musical gestures first came to her when her clarinet teacher told her

that I was wasting my air by moving a lot when playing long phrases. Hearing this made me feel confused, since I thought I stood relatively still while playing. This led me to reflect upon the fact that there seemed to be a discrepancy between how I thought I was moving versus how others perceived my body language.90

We find this description, of how her initial interest in a study of gesture was sparked, to be revealing in relation to our thematic analysis. Bohlin expresses an experience which is grounded in the relation between performer and instrument, but, at the same time, the experience she describes is closely related to the type of issues addressed by many students in the category of ‘Rehearsal and Efficient Practicing’. However, this initial observation led Bohlin to further reflection on the relation between body movement and expressiveness in music performance (effectively relating her project also to the category of ‘Interpretation, Expression, and Voice’). The aim of her thesis was, therefore, formulated as seeking ‘a more expressive performance by increasing awareness of the gestures I make while playing’.91

Bohlin further notes how ‘It is hardly possible to conduct a study about gestures in music without coming across the concept of embodiment’.92 Here, she turns to Randall Harlow, who claims that ‘it is argued that musicians and their musical instruments exist in an ecological relationship at the level of embodied gesture’.93 Inspired by previous research in systematic musicology—but also, more immediately, by the artistic research of her clarinet teacher, Robert Ek—her project had a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. Hence, it should be noted how, in Bohlin’s project, a closer collaboration between teacher and student was possible because her teacher was already carrying out an artistic PhD project on a related topic.

Bohlin collected video data of her own performance, as well as of a fellow student and of her teacher, all performing the first movement of Brahms’s second clarinet sonata in E-flat major, Op. 120 No. 2. Qualitative and quantitative coding of these videos were carried out, involving both the teacher and the fellow student in stimulated recall sessions. Further interviews with both informants added to the qualitative data. The outcomes of the project led Bohlin to conclude that ‘for experienced performers, expressiveness is vital when playing music and musicians use a variety of tools for enhancing musical intentions when performing, gestures being one of them’.94 She eventually concluded that ‘[h]ow these insights will influence my future performances remains to be seen but by turning attention towards my own gestural language I have not only been studying gestures, but also myself, as a performer’.95 We observe how this thesis, even more than in the case of Sundell’s bachelor project, shows evidence of instigating a different relationship between teacher and student. The research design has been instrumental in replacing the traditional master-apprentice model with a more dynamic interrelation. The reasons for this appear to be manifold, since her clarinet teacher is himself involved in similar research on gesture: their interactions in the collection and analysis of data became a vehicle for collaboration and, perhaps even, mutual learning. In addition to this collaborative design, the study itself brought insight into the student-teacher interaction, and the widened understanding of these relations appear to have further sparked more autonomous modes of working. In an interview in January 2023, Bohlin made the observation that her work on the thesis has provided several tools for lifelong learning. She mentions getting ‘inspiration from what others have done previously, to be introduced to different ways of analysing and reflecting on one’s music making and to get tools for concretizing things one already “knows” but which are difficult to verbalise’.96 Again, these reflections emphasise how the task of situating one’s artistic practice—as a part of designing and then writing a thesis, as well as of acquiring methods for critical reflection—may contribute to laying the groundwork for student autonomy and student-driven learning.

Discussion

The discussion is structured according to the three main perspectives promoted in the Bologna Declaration. Hence, we will consider whether and how the degree projects analysed in the study embrace forms of learning that are research-based, student-centred, and contribute to developing students’ capacity for lifelong learning. Outside of these three perspectives, our study has also indicated that experimentation has proven to be an important factor in a majority of the analysed projects, just as can be observed in the development of artistic PhD programmes in music,97 and we address this perspective and its implications for HME in a final section.

Research-Based Approaches

Just as concluded by Georgii-Hemming et al.,98 a central trace of the impact of artistic research in HME is the predominant use of reflexive methods in the design of degree projects. In our study, we have found many different approaches to how qualitative and reflexive methods can be integrated to enhance artistic development.

In all of the theses discussed, reflexive methods are interwoven with artistic development, which we understand as a result of the implementation of methods and practices from artistic research. Moreover, we find the use of such methods to have created learning situations that contributed to the students’ development of self-understanding, situatedness, and an interest in lifelong learning.

It appears that the degree project has typically played a central role in the students’ education. For example, Mellberg described how, for the artistic development of their duo, the thesis project was ‘by far the most important’, creating a ‘clear focus and a goal to aim for’.99 As examples of artistic outcomes, Sundell points to an increased awareness of a personal ‘musical voice’ and of how to develop it,100 while Bohlin observes the emergence of ‘a more expressive performance’ and claims that the origin of this development is found in an ‘increasing awareness of the gestures’ she makes in performance.101

Regarding methods used, we see, as noted in the preliminary qualitative content analysis, that logbooks and various forms of audio-visual documentation are used. Several master’s theses employ stimulated recall methods, which allows students to combine second- and third-person perspectives with the first-person accounts otherwise typical of many reflexive methods. For instance, in Mellberg, intersubjective approaches were employed both in the artistic work as well as in the analysis of the creative collaboration in their duo, using ‘stimulated recall to get a 3rd person perspective of [their] musical interpretation’.102 Furthermore, Mellberg claims that stimulated recall analysis has enabled ‘constructive criticism’ and increased awareness of how ‘to reach the intended expression’ and, ultimately, contributed a ‘deeper understanding of the knowledge we have gained through this project, and also the knowledge we already possessed’.103

In reflecting back on the design of his thesis project, Lilja observes how ‘there is a difficulty in observing oneself’, and his project sought to methodologically address this challenge by introducing feedback from different groups of listeners, in combination with his own reflections as captured in logbooks and score annotations.104 With these, Lilja sought to capture how artistic research can allow for the creation of new knowledge ‘that someone else can understand and learn from’.105

Lilja’s thesis points to the usefulness of obtaining more developed methodological awareness when it comes to the negotiation of subjective and intersubjective perspectives in artistic research. It further exemplifies how students may benefit from developing self-reflexive skills. On the same note, Hernandez observed how the degree project prompted her to ‘analyse and observe my playing from an outside perspective, in ways that were new to me’.106 But, the development of such skills is also particularly useful as tools for lifelong learning, a perspective which we address further below.

However, a recent paper by Moberg instead notes how students’ formulations of the purpose-statements in their master’s theses ‘typically include “I”, “me”, “mine” or “my”’ and connecting this tendency with a ‘focus on individual competences rather than collective knowledge’.107 In Moberg’s discourse analysis, it is claimed that such introspective perspectives were rendered hegemonic in these theses as justifications were premised on individualistic wants, needs, or interests: ‘Here, the “I” is centred not only as the object of study, but also as an authority and source of knowledge, as a problem and as a means’.108 Hence, Moberg suggests that these degree projects are ‘primarily expected to be self-serving, occasionally serve colleagues, and, in exceptional cases, an audience’.109

While we sympathise with Moberg’s wish to emphasise the need for degree projects to situate the student in a wider context and address issues that are of relevance for a wider audience, we believe that reflexive methods have a wider usefulness in the teaching and learning of music performance in HME. As stated by Lilja, ‘[i]n artistic endeavours we make a lot of choices, and artistic research is where we explain why we made these choices – to the extent that someone else can understand and learn from them’.110 Thus, as also clarified through Lilja’s reflection regarding the difficulties of self-observation, with reference to the methodological design of his thesis project, it seems clear that the use of reflexive methods should not immediately be equated to what Moberg describes as focussing ‘on individual competences rather than collective knowledge’.111

Georgii-Hemming et al. describe how teachers and institutional leaders conceptualise reflection as demanding the ability to situate ‘yourself in relation to society as well as to how certain musical ideas and ideals have developed historically’.112 Johansson and Georgii-Hemming further note how ‘[t]he research-oriented degree project in the first and second cycles of HME has gradually emerged as a discipline-specific instrument for individual as well as institutional development’.113 At the same time, in Moberg’s study, it is claimed that, in degree projects, ‘justifications are not anchored in previous research or situated within a field of research’.114 However, our observation in regard to the students’ awareness of research contexts is rather the opposite to Moberg’s.115 We find that the theses discussed here explicitly refer to previous research and were understood to build directly on music-research practices. Bohlin expressed this when noting how her ‘goal was to use methods and practices from artistic research, to the greatest extent possible, [...] perhaps most of all in the coding and analysis of my recordings’.116 It may be worth mentioning that, while qualitative analysis of video and audio recordings are not in themselves particular to artistic research, such methods have tended to be a typical feature of the design of artistic research projects. With the use of audio and video technologies, the student projects discussed above, have been designed through cycles of experimentation, documentation, and analysis, leading to the development of new practices. Furthermore, a historical perspective on the research questions has both situated the studies as well as informed the design, as can be seen in the projects of Sundell and Perčič.117 Lilja, on the other hand, situates both the artistic practice and a research approach in the domain of algorithmic composition. The literature reviews in all of these six theses are substantial and situate the projects in various ways in relation to art worlds and science worlds.118 Taken together, we find all of these qualities to suggest that the theses analysed in this chapter are all built on artistic research methods and practices.

Student-Centred Teaching and Learning

As put forth above, the overarching aim of the course design of the bachelor’s and master’s programmes at the Piteå School of Music has been to identify each student’s individually defined and experienced artistic possibilities and challenges. A further aim was to develop a project for which the student’s individual motivation is strong and the potential for individual artistic development is central. As phrased by Perčič, in his reflection, a well-designed thesis project may address ‘an issue that cannot be solved immediately, but needs to be explored from within’ and may find ‘an approach that goes from the inside out’.119 Here, Perčič aligns with Hannula et al., who argue that, ‘instead of a top-down model or intervention, there has to be enough room, courage and appreciation for organic, content driven development and growth’.120 Furthermore, this student-centred approach has also entailed that students’ understanding of their own needs for development became more clearly articulated, thus improving their capacity for autonomous learning. An example of this is when Lilja notes that learning is a matter of ‘understanding what there is to understand’.121 Sundell, in reflecting on the role of the thesis project, goes further to observe how the project went ‘from being instructive to constructive’.122 The student was no longer required to acquire knowledge from the teacher but to ‘generate their own knowledge’.123 In reflecting on the degree project, Sundell notes how he has found that ‘most teachers at the university work on a principle of teaching the student to learn by themselves’ and, further, observes how ‘this approach was also a big part of the thesis course. The student is given the tools to learn and develop skills on their own’.124

On a different note, and bringing forth a set of critical reflections, Mellberg finds a lack of connections in the teaching ‘between expressing something and the practice of piano performance’.125 She further describes how one ‘practises techniques to play fast, loud or to understand complex harmonies but forget the part where to use the crafts to express something’.126 Similarly, but in a different genre, Hernandez, as a classical violinist, observes that what she ‘can sometimes find missing in teaching is finding the source of the problem, not just identifying it’,127 and her thesis project sought ways to address such shortcomings. This observation is in line with previous research suggesting that, to avoid limiting the potential for students’ development of metacognitive skills, teachers should involve students in discussions regarding their problems, the sources of these, as well as how they could be solved.128

Perčič, in turn, takes such institutional critique even further, asking ‘what skills are best taught in a master-apprentice way, and what skills could be further developed through the use of scientific approaches and novel forms of teaching’.129 He argues that conducting is seldom a practice that is best taught by copying a master. Rather, he advocates the development of independence, personal judgement, but also ‘building new knowledge, using technologies, research papers and especially experimental testing’, which, he suggests, is ‘the way forward’130 for the teaching and learning of music performance. An outcome of such student-centred approaches, which is highlighted in several interviews, are, as expressed by Mellberg, the emergence of a stronger sense of ‘autonomy and self-confidence’.131 Lilja, in turn, notes how ‘[i]ndependence may be one of the most important qualities if you want to become a freelance composer’.132 This suggests that a student-centred approach may indeed be a means for properly preparing students for professional life and for lifelong learning.

Approaches to Lifelong Learning

Lilja makes useful observations regarding how abilities for lifelong learning may be drawn out of interactions with teachers and supervisors, noting how ‘[t]heir comments during feedback will echo in my head as I grow, and I will ask myself ‘what would my teacher/supervisor/peer have said?’.133 Furthermore, by developing a deeper understanding for how artistic collaboration may serve as a tool for lifelong learning and artistic growth, Mellberg expresses how the combined collaborative perspectives made the duo partners become at times, ‘each other’s supervisors, and thus also our own’.134 Mellberg further notes how

becoming one’s own teacher, I believe is a matter of perspective. To manage to make observations of your own music making from several perspectives, than those from inside the experience of performing. It is great to be able to record oneself and show and discuss what is heard and seen with others, and thereby get perspectives to utilise in an analytical moment.135

A similar observation is made by Lilja, who relates an increased ability in the development of autonomy as an artist, which he connects to the different forms of feedback that formed a central aspect of the project design in his master’s thesis:

Feedback is crucial in becoming your own teacher, because if you comment on someone else’s creative decisions, you will look at your own work and ask yourself ‘what would I have said if this was someone else’s work?’. I would argue that continuously giving and receiving feedback to and from my peers is one of the main reasons why I reached the point I am at today, and due to the importance of synergy between classes I find this point to be of relevance to this question.136

To summarise, the student theses appear to have provided different methodological tools and encouraged personal abilities that may promote lifelong learning. Perhaps such meta-cognitive processes137 can be summarised through Perčič’s observation of how the thesis project may function as ‘a basic tool for thinking about your own daily learning – a kind of resilience generator’.138

Experimentation

Experimentation is not only a long-standing component of research in the hard sciences but also a decisive factor in the development of music and other arts since the early twentieth century. In fact, it played an important role much before then, although sometimes under a different label. As argued by Stefan Östersjö, ‘the core of an artistic research project is where the subjectivity of an artist encounters an experimental approach, a challenge to one’s practice, and perhaps often to one’s habits’.139 Along similar lines, Hannula et al. claim that the artistic researcher ‘must be able – even by bending the rules – to find or create courage for experimentation, for taking risks and, above all, for enjoying the uncertainty, detours and failures of research’.140 In this final section of the discussion, we will consider to what extent artistic experimentation has characterised the degree projects in the study.

In the theses of four students—Lilja, Mellberg, Perčič, and Sundell—experimentation is present (to varying degrees) as a way of conceptualising different aspects of their music making and learning but also as a method for artistic development. Thus, Lilja describes artistic experimentation as a ‘main research method’,141 while Sundell’s thesis exemplifies how explorative approaches to the relation between performer and instrument can give rise to expanded possibilities and novel modes of expression through the design of iterative cycles that involve experimentation. In Mellberg, the experimental dimension of the project is a stylistic measure, while Perčič refers to his ‘experiments with reductive analysis’ as a central artistic method.142 While the prominence of reflexive methods has been rightly observed to be a central trace of the impact of artistic research methods and practices in HME, we believe that a further development of methods based on artistic experimentation has the potential to deepen the students’ understanding of artistic research and its potential for the teaching and learning of music performance.

Final Thoughts

The present study has obvious limitations. First of all, it scrutinises in depth a relatively limited number of theses and, secondly, it focuses on theses produced in one single school of music. Furthermore, the initial stages of the qualitative and quantitative analysis were tentative, though built on our pre-understanding of the material (since two of the authors had either been examining or supervising the theses studied). As discussed above with reference to Moberg’s study, also in this chapter, it has been difficult to produce a transparent argument through content analysis of student theses. However, despite the limitations in the method and design, the initial analysis provided the necessary structural understanding, which allowed us to select theses for the following, more detailed, qualitative analysis.

Hence, there is a need for a deeper understanding of both the development of methods and practices in the artistic PhD education in HME, and its impact on first and second cycle education in these institutions. Moreover, as Moberg notes,143 the relationship between the written text and the artistic artefacts should be explored more in-depth in future studies.

In a publication created by the Swedish partners of the REACT project, based on interviews with students, alumni, staff, and stakeholders outside of HME, it is argued that, in Sweden, ‘artistic research is not fully implemented in the current curricula, and especially in the first and second cycle. As a result, students do not gain enough experience of and skills in critical thinking and academic writing’.144 However, through our study of the theses discussed above, we observe that research methodologies and practices drawn from artistic research are successfully employed in degree projects. Or, to put it differently, while a wider group of informants in Correia et al.145 argues that there is a need to strengthen the role of artistic research in HME, our analysis of student theses at the Piteå School of Music suggests that a process of implementation of artistic research methods and practices is already well underway. The resulting learning processes for the students can be observed to be fruitful, both in terms of project results as well as expressed in their retrospective self-assessment. Many means for developing students’ capacity for lifelong learning and for increasing their understanding of music, musical performance, and themselves as artists are brought forth, both in the written theses as well as in interviews cited above. We also wish to underline the importance of having faculty that have pursued PhD studies, as such involvement, as evidenced in Bohlin’s project, opens up for different forms of student-teacher collaboration, in the exploration of more student-centred and research-based approaches to the teaching and learning of music performance.146 Again, we believe that herein lies the potential for what Perčič advocates as ‘the way forward’.147

To conclude, we find that the study proposes three main implications for HME. First, that artistic research has shown potential to enable more student-centred forms of teaching and learning, based to a great extent on its use of reflexive methods. Second, that employing artistic research practices and methods shows great potential to enhance lifelong learning. Third, that the role of artistic experimentation, as expressed in the student theses, suggests that the notion of the artistic research laboratory148 is a potential model for how the teaching and learning in HME may be reconsidered.

At the same time, we would be the first to acknowledge that there is still so much to learn; and the path ahead is, indeed, not clearly mapped out. The final argument of this chapter is, therefore, that results such as presented in this small-scale study should be cross-referenced with similar data from other countries, a research approach which in turn could lay the ground for a more substantial re-imagining of curricula in HME, grounded in artistic research practices.

References

Andersson, Sofie, ‘Expressive Voice: Enhancing a vocalists performative tools in duo collaboration with a pianist’ (master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2022), https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-91445

de Assis, Paulo, Logic of Experimentation: Reshaping Music Performance in and through Artistic Research (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461662507

Bartleet, Brydie-Leigh, ‘Artistic Autoethnography: Exploring the Interface Between Autoethnography and Artistic Research’, in Handbook of Autoethnography, ed. by Tony E. Adams, Stacy Holman Jones, and Carolyn Ellis (New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 133–45, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429431760-14

Becker, Howard S., Art Worlds, 25th anniversary edn., updated and expanded (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982/2008)

Blair, Erik and Hendrik van der Sluis, ‘Music Performance Anxiety and Higher Education Teaching: A Systematic Literature Review’, Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 19.3 (2022), 5–15, https://doi.org/10.53761/1.19.3.05

Bohlin, Stina, personal communication, 8 January 2023

——, ‘Meaningless Movement or Essential Expression: A study about gestures’ (master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2021), http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-85247

Correia, Jorge and others, REACT–Rethinking Music Performance in European Higher Education Institutions, Artistic Career in Music: Stakeholders Requirement Report (Aviero: UA Editora, 2021), https://doi.org/10.48528/wfq9-4560

Crispin, Darla, ‘Looking Back, Looking Through, Looking Beneath. The Promises and Pitfalls of Reflection as a Research Tool’, in Knowing in Performing: Artistic Research in Music and the Performing Arts, ed. by Annegret Huber, Doris Ingrisch, Therese Kaufmann, Johannes Kretz, Gesine Schröder, and Tasos Zembylas (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2021), pp. 35–50, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839452875-006

Drisko, James W. and Maschi, Tina, Content Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190215491.001.0001

European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education, ‘London Communiqué: Towards the European Higher Education Area: Responding to Changes in a Globalised World’, 18 May 2007, http://www.ehea.info/Upload/document/ministerial_declarations/2007_London_Communique_English_588697.pdf

Friend, Rodney, The Violin in 5ths: Developing Intonation and Sound (London: Beares Publishing, 2019)

Georgii-Hemming, Eva, Karin Johansson, and Nadia Moberg, ‘Reflection in Higher Music Education: what, why, wherefore?’, Music Education Research, 22.3 (2020), 245–56, https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2020.1766006

Hallam, Susan, ‘The Development of Metacognition in Musicians: Implications for Education’, British Journal of Music Education, 18.1 (2001), 27–39, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0265051701000122

Hannula, Mika, Juha Suoranta, and Tere Vadén, Artistic Research: Theories, Methods and Practices, trans. by Gareth Griffiths and Kristina Kölhi (Helsinki: Academy of Fine Arts, 2005)

Harlow, Randall, ‘Ecologies of Practice in Musical Performance’. MUSICultures, 45.1–2 (2018), 215–37

Hernandez, Sara, personal communication, 2 January 2023

——, ‘Fiolen i kvinter: En ny metod att hitta en handställning som förbättrar intonationen’ [The Violin in Fifths: A novel method for finding a hand position that improves intonation] (bachelor’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2022), http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-91435

Holmgren, Carl, ‘Dialogue Lost? Teaching Musical Interpretation of Western Classical Music in Higher Education’ (PhD thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2022), http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-88258

Johansson, Karin and Eva Georgii-Hemming, ‘Processes of Academisation in Higher Music Education: the case of Sweden’, British Journal of Music Education, 38.2 (2021), 173–86, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051720000339

John-Steiner, Vera, Creative Collaboration (Oxford University Press, 2000)

Lilja, Robin, personal communication, December 31 2022

——, ‘Constraint-based Patterns – An Examination of an Algorithmic Composition Method’ (Master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2021), http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-85001

——, ‘Musikaliska kontraster genom förbud: Undersökning av min kompositionsmetod antikomposition’ [Musical Contrasts through Prohibition: Investigation of my Composition Method Anticomposition] (bachelor’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2019), https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-74099

Luleå University of Technology, C7010G, Artistic Research Processes: Theory and Method, 15 Credits [course syllabus] (Luleå: Luleå University of Technology, 2022a), https://webapp.ltu.se/epok/dynpdf/public/kursplan/downloadPublicKursplan.pdf?kursKod=C7010G&lasPeriod=208&locale=en&locale=en

——, X0005G, Research Process C, 7.5 Credits [course syllabus] (Luleå University of Technology, 2022b), https://webapp.ltu.se/epok/dynpdf/public/kursplan/downloadPublicKursplan.pdf?kursKod=X0005G&lasPeriod=214&locale=en&locale=en

——, F0316G, Thesis, Bachelor Programme in Music – Classical Musician, 15 Credits [course syllabus] (Luleå University of Technology, 2022c), https://webapp.ltu.se/epok/dynpdf/public/kursplan/downloadPublicKursplan.pdf?kursKod=F0316G&lasPeriod=212&locale=en&locale=en

Lundström, Håkan, ‘Svensk forskning i musik: De senaste 100 åren’ [Swedish Research in Music: The Last 100 Years], Swedish Journal of Music Research, 101 (2019), 1–47

Mellberg, Ester, personal communication, 6 January 2023

——, ‘A Partner at the Piano: Expanding Musical and Performative Expressions in a Duo with a Vocalist’ (Master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2022), http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-91443

Moberg, Nadia, ‘The Place of Master Theses in Music Performance Education in Sweden: Subjects, Purposes, Justifications’, Music Education Research, 25.1 (2023), 24–35, http://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2023.2167966

Nelson, Robin, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond). Principles, Processes, Contexts, Achievements, 2nd edn (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90542-2

Östersjö, Stefan, Nguyễn Thanh Thủy, David Hebert, and Henrik Frisk, Shared Listenings: Methods for Transcultural Musicianship and Research (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009272575

Östersjö, Stefan, ‘Thinking-through-Music: On Knowledge Production, Materiality, Subjectivity and Embodiment in Artistic Research’ in Artistic Research in Music: Discipline and Resistance, ed. by Jonathan Impett (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2017), pp. 88–107, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21c4s2g.6

——, ‘Art Worlds, Voice and Knowledge: Thoughts on Quality Assessment of Artistic Research Outcomes’, ÍMPAR Online Journal for Artistic Research, 3.2 (2019), 60–69, https://doi.org/10.34624/impar.v3i2.14152