3. Finding Voice

Developing Student Autonomy from Imitation to Performer Agency

© 2024 Mikael Bäckman, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0398.04

Introduction

Across the past twenty years, artistic research has offered new approaches to the study of artistic process. This development can be divided in two types: those that study individual process and those who study collaborative process.1,2 In Blom et al, such study of individual artistic process is also found to have implications for education, since ‘[t]he process of engaging in, reflecting and analyzing, writing, and feeding back into one’s own arts practice and teaching is, itself, an ‘artistic action research’ model that contributes to the discipline area as well as the development of the individual artist-academic’.3 This chapter unfolds such a process of applying artistic research findings in teaching in Higher Music Education.

Since the implementation of the Bologna process, there is an expectation that teachers in higher music education (henceforth HME) should promote student autonomy and lifelong learning.4 Previous research suggests that informal learning practices are effective tools in order to enable student autonomy.5 An important aspect of informal learning is that, unlike traditional learning, there are no definable goals, the ends are not defined in advance.6 This has the implication that the student can be involved in planning the content of the learning experience, to take charge of their own learning, thus leading to meta-cognitive skills such as learning about learning (as discussed above in Chapter One), and finding lifelong learning strategies.7 In such a learning situation, the teacher’s role is ‘mainly to assist students to become aware of their strengths and weaknesses in relation to future challenges’.8 In order to help the student to obtain lifelong learning strategies, the teacher must meet the student where s/he is, and adapt the content to each individual.9

In what follows, I will attempt to explore how results from my artistic research project may be applied in my own teaching.10 Through my practice as a harmonica player, I have investigated how a personal expression, or voice, may emerge from a process initiated by transcription and imitation. The aim of the project was to explore the transformation of a performer’s voice through a process of transcribing and practicing solos by the iconic harmonica player Charlie McCoy. When applying my findings from this artistic research project in my teaching in HME, the challenge was to initiate a similar process with my students, with the aim of promoting student autonomy and lifelong learning. So how does the idea of copying someone’s playing relate to student autonomy? The answer may lie in informal learning practices, since they ‘may allow students to develop a degree of musical autonomy as well as experimenting with and formulating their own unique musical voice’.11 Up until the inclusion of jazz studies in HME, the only way to learn how to play was through informal learning.12 The same goes for Blues and Country music. Today, ‘it could be said that the jazz tradition underwent a change for the worse when it became a subject formally studied in schools’.13 This formalization of how you learn how to play jazz, at the expense of the traditional informal way of learning, has been critiqued.14 There is a paucity of studies concerning this shift from informal to formal regarding Country music and Blues within HME, most likely since they entered the world of HME at a much later stage. However, as a musician mostly active within the field of Country music and Blues, I would argue that those genres run the risk of being institutionalized, in the same way as one may argue that Jazz has been.

This chapter builds on an analytical perspective, informed by embodied music cognition, and engages with concepts of voice and affordance to try to clarify these processes. According to the research paradigm ‘embodied music cognition’ (EMC), the involvement of our body is central to understanding our interaction with music.15 EMC builds on embodied-cognition theories and applies them to music. I view voice as the sum of all the choices a musician makes—choices that become patterns, which, in turn, make a musician unique.16 For a further discussion of voice, see Mikael Bäckman.17 In order to fully understand a musician’s voice, one needs to engage with the concept of affordances. This concept originates from James Gibson and his work in ecological psychology, where he argues that we perceive objects based on how we can use them, i.e., what they afford us.18 This is a relational concept, since objects do not afford the same thing to different animals or, indeed, different humans. This is easily applicable to musical instruments, as a harmonica in the hands of a professional affords many things that is unavailable for a beginner (see also Chapter 2 of this book).

In what follows, I show how the transformation of voice took place within my own artistic practice, with a particular attention to challenges I came across. Furthermore, I will show how I have applied my method in my teaching in HME, focusing on students’ challenges.19 I will also briefly touch upon the impact of the affordance of the diatonic harmonica in this specific voice transformation process. In the first section, I will describe the overall method of my artistic research project. Then I will present the preliminary artistic results, giving extra attention to two examples where my method encountered challenges. In the next section, I will describe and present some tentative results from my educational study. Once again, I will put the spotlight on what proved to be difficult, this time focusing on the challenges that my students experienced. In the final section, I will discuss the challenges that my students and I encountered and reflect on how the similarities and differences of these challenges relate to our various experiences as musicians.

A Performative Study of Idiolect

This chapter is based on the results of my artistic research project, as well as a qualitative study of my teaching in HME. The first stage of my project was to immerse myself in the playing style of country harmonica legend Charlie McCoy. McCoy has been active as a session musician, as well as a recording and performing artist, since the early 1960s. He has recorded more than 14,000 sessions during his still-ongoing career.20 I transcribed McCoy’s first thirteen albums as a featured artist, representing his recorded output during the 1960s up until 1978.21 These transcriptions were notated, more specifically, written down in a tablature notation. The transcriptions were also aural, i.e., I learned to play the transcriptions along with the original recordings. This was a very important part of the process, since this is how I attempted to embody the idiolect of McCoy. Based on these transcriptions, McCoy’s playing style, particularly the charting of his musical idiolect, was analysed. From this analysis, a number of frequently occurring licks and strategies were identified. I argue that these licks are important features of McCoy’s idiolect. In addition to the transcriptions, in-depth interviews were conducted—with McCoy as well as two other prominent country harmonica players: Buddy Greene and Mike Caldwell. The aim of these interviews was to test the accuracy of my analysis. With McCoy’s licks as a point of departure, I have created my own variations of these. This lick-creation process was documented with video/audio recordings.22 This journey, from analysis to creation, is the focus of my artistic research project. In the next section, I will present my artistic results, thus far. I will also present a few challenges I encountered.

Results

The first part of my artistic research project was to transcribe and imitate the harmonica playing of Charlie McCoy. The analysis of those transcriptions, combined with the results from the interview with McCoy, as well as the interviews with Caldwell and Greene, informed me in two ways. Firstly, I became quite knowledgeable concerning McCoy’s idiolect, not only in an analytical way, but also in a very practical way since I learned to play my transcriptions. One might say that I became proficient at McCoy’s idiolect, both intellectually and in musical practice. Second, since McCoy’s playing has been, and still is, so influential, mapping his idiolect also functions as an audit of country harmonica playing in general. The mapping is thus not only of an idiolect, but also a significant mapping of country harmonica playing from the 1960s and onwards. This mapping was important for the next phase of my project; when I created new licks, I had an embodied knowledge of what was innovative and what was derivative.

The results thus far are twofold. First, I came up with results that are musicological, i.e., the transcriptions and my analysis of McCoy’s idiolect based on said transcriptions and complementary interviews. Second, based on the knowledge I gained through interviews and transcriptions, I have sought to transform my own artistic voice as a country harmonica player, thus producing artistic results. In what follows, I will describe how the musicological results have inspired and informed my artistic results.

As described above, my artistic research project has provided me with a thorough mapping of McCoy’s idiolect. This has resulted in two publications, one of those focuses specifically on how McCoy found his own style, by relating to his influences. These influences were mainly other musicians—guitarists, fiddle players, and pedal steel guitarists—that McCoy worked with in the recording studios of Nashville. Therefore, the role of instruments other than the harmonica in this process is discussed in the paper.23 The other publication presents McCoy’s idiolect in a more artistic way; it is an audio paper, which also deals with how I have used my McCoy idiolect study to transform my own voice.24

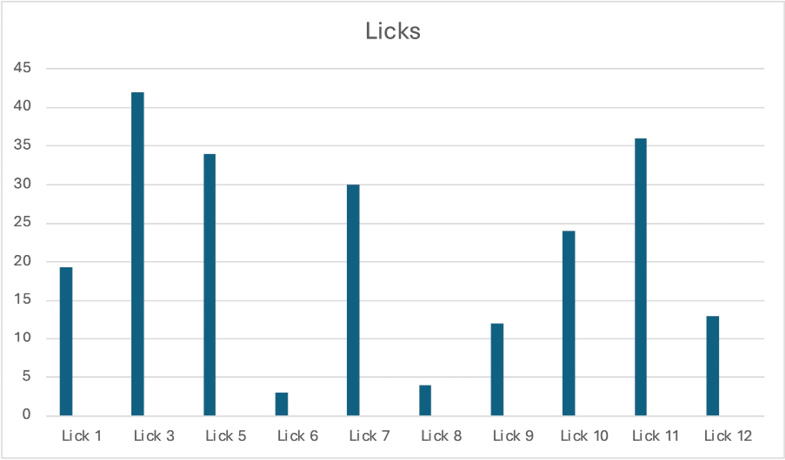

Another result was my creative process of lick generation. I chose 10 McCoy licks, using these as starting points to create original material. I devoted a practice session to each of these McCoy licks, which I documented with video and audio recordings. In each session, I played a McCoy lick verbatim, over and over, until my inner hearing presented, or rather suggested, a variation of this lick. I played that variation and, if it was to my liking, I continued to play this new lick over and over until I came up with a variation of that lick. This process produced more than 200 new licks based on McCoy’s original licks (see Figure 3.1). The goal of each session was to let the original McCoy lick inspire me to create variations, thus creating licks which are no longer McCoy’s but, instead, my own original material. Important to note here is that each of these ten licks have many variants in McCoy’s output. In other words, my variations on McCoy’s licks can also be seen as a logical continuation of what he himself has been doing throughout his career. McCoy has recorded licks he liked, and, at later recordings, these licks have recured, usually slightly changed. I, in my turn, have identified McCoy licks which I like, then I have consciously changed them. However, that is only the beginning. As I now implement these licks in my playing with my band ‘John Henry’, my licks are sometimes being altered as I improvise my solos.25 Sometimes I start out playing a lick and, as I am playing it, I hear a new way to resolve the phrase. This might be inspired by what someone else in the band is playing, or the chord changes of the song, or the groove we are playing, or someone’s previous solo in the song. In the moment of playing the lick, I am usually unaware of what inspires me to make a change, it is a very intuitive process which draws upon all my embodied knowledge as a musician. The number of licks produced is significant since, in the next phase of my project, I commenced to practice my own licks, embodying them in my bag of licks. Therefore, I would consider a session successful if it produced many variations on the original McCoy lick. As can be seen in Figure 3.1 below, some licks were more productive than others.

Fig. 3.1: Overview of the 10 McCoy licks I chose with the intent of creating original licks inspired by the original recordings. Lick 2 and 4 are omitted since I chose not to engage with those.

When I transcribed McCoy’s playing, I realized that certain licks were reminiscent of pedal steel guitar playing. This suspicion of mine was confirmed during the interview with McCoy, where he pointed out that his style is based on adapting licks by other typical country instruments, the pedal steel guitar being one of them, to the harmonica. As I realized that I was very fond of playing these pedal steel-like licks I found in my transcriptions, I decided to do what McCoy had done, i.e., transcribe pedal steel solos and licks. This proved to be quite fruitful; it produced very interesting licks when I adapted the original solos and licks to work with the affordances of the diatonic harmonica. Rather than taking the detour of transcribing a harmonica player’s version of pedal steel licks, I cut out the middleman and went straight to the source, i.e., the pedal steel. Niklas Lundblad and Fredrik Stjernberg write about the distinction between emulation and imitation.26 When emulating, X does what Y did to achieve a specific goal. Emulating means that X focuses on what specifically led Y to achieve that goal. When imitating, by contrast, X does what Y did, duplicating not only the behaviour that specifically led to the achievement of the desired goal but also other behaviours.27 In my project, I would consider learning to play McCoy’s solos an act of imitation. However, transcribing pedal steel solos—since the interviews revealed to me that this was McCoy’s method—is an act of emulation. I am, at the same time, imitating pedal steel playing and emulating Charlie McCoy.

Another type of lick which McCoy has recorded on a few occasions, is his harmonica adaptation of a vocal yodel.28 McCoy’s yodels occur in songs originally performed by Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams. When I practise these yodel-licks, I use a technique known as corner switching, taught to me by Robert Bonfiglio, which makes them more accessible on the harmonica.29 During the interview, McCoy confirmed that he does not use the same technique as me, which might explain why he has not explored the concept of yodelling on the harmonica in more depth than he has. It made me realise that this is a perfect area for me to delve deeper into. So, once again, I stopped taking the detour of transcribing a harmonica player’s imitation of the original source, i.e., the yodels, and started transcribing the vocal yodels themselves. In other words, I chose the path of emulation rather than imitation. Some yodels work quite well on the harmonica without the need to adapt them. However, most of them need to be altered to make them work well with the affordances of the harmonica. I found that the most interesting sound is when I can use chromaticism, playing with portamento through bending notes. This transformation, adapting the vocal source to fit the affordances of the harmonica, has been a very rewarding negotiation that has taught me much about my instrument, what it offers, and what it resists.

One of McCoy’s most significant contributions to the field of country harmonica playing is his use of the so-called ‘country-tuned’ harmonica. McCoy did not invent this tuning, but he is the first to record with it; hence, he is responsible for disseminating this tuning throughout the harmonica world. McCoy uses this tuning to make the affordances of the harmonica better fit his musical needs. The country tuning turned out to be especially applicable on the dominant chord. In my own playing, I found the major supertonic chord to be a challenge, where the harmonica resisted more than it offered.30 Since this chord is quite common in Western Swing, I realised there might be a need to change the affordances of my instrument. Therefore, I started exploring a tuning I had devised in 2019, which I call Western Swing tuning. This tuning alters the affordances of the harmonica and offers the same advantages on the supertonic chord that the country-tuned harmonica does on the dominant chord.

Difficulties

Having described the results of my artistic research project in the previous section, I will now move on to present some challenges experienced by myself and by the students. Whereas some of the practice sessions I did based on McCoy licks generated more than forty new original licks, two of the sessions produced less than five new versions (see Fig. 3.1). In this section, I will direct my focus to these two, less fruitful, lick-generating sessions.

Lick Eight

Video 3.1. Video of author documenting lick-generation session eight,

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f09a5320

When I start lick-generation session eight, as in all my sessions, I verbally define the lick which I am about to start working on. In this particular session, I start out by stating that lick eight ‘…is not as clearly defined as some of the other licks…’ (0.19). After some hesitation, I define lick eight as ‘a descending motion followed by an ascending interval jump [leap]’ (0.35). Most sessions last for approximately twenty minutes, and some licks were explored in two or more such sessions. Lick eight’s session, however, only lasted for fourteen minutes, then I gave up. At one point in the session, after several fruitless attempts at creating an interesting new lick, I simply state that ‘hmmm, that just sounds like Charlie’ (03.41). In most of these sessions, an interesting variation of McCoy’s original lick arrives within the first minute or two. With lick eight, it took more than nine minutes to produce the first variation that I found to be worthy of preservation. Watching the video recording of the session, it is clear that I am quite ambivalent about that new lick, stating that ‘Not sure if I like it or not, but yeah, maybe’ (10.49).

At 14.34, the camera’s battery ran out and interrupted the session. While replacing the battery, I realise that this lick is a dead-end and decide not to resume the session. When listening back to these four licks at the time of writing this chapter, approximately two years after the session, I find these less than impressive. Even after practising and performing my corpus of new licks for nearly two years’ time, I still found a vast majority of these licks to be to my liking. The licks derived from lick eight however, are not quite up to scratch. One reason this lick failed to produce more material might be the somewhat unclear definition of the McCoy lick itself. In most cases during these sessions, I had a clear lick, or strategy, to work with. The licks had a solid construction, yet they were easy to turn into malleable material. However, when the original lick seemed to lack such clarity, it paradoxically lacked the ability to become malleable. It was almost as if the licks that produced many variations were made from clay with a perfect texture. The clay was not too hard, which would have made it difficult to shape it into new forms. On the other hand, it was hard enough not only to have an original shape, but also to maintain the shape I altered them into.

Lick Six

Video 3.2. Video of author documenting lick-generation session six,

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/8ef03205

Lick six is played over a II-V-I progression, and it was the least productive of all my lick-creation sessions. The first lick took approximately three minutes to come up with, but then it took almost ten minutes to produce the next one. Even though this session lasted for twenty minutes, it only produced three new licks. However, unlike lick eight, the licks produced during this session were to my liking, and I have found versions of them popping up in my playing ever since they were first discovered. However, when the session was over, I had a feeling that I had not been creating, but rather that I was playing, or perhaps constructing, an exercise.31 In other words, I was struggling to find creative material. What I came up with sounded correct over the chord changes, but most of what I played did not excite me.

One possible reason for the meagre output of lick-session six might be that I am playing over a predefined chord progression, which may have limited my imagination. In other sessions, I would hear a chord or chord progression in my mind, but I would allow myself to be free to make changes to that progression as a new lick developed. However, during this session, I was locked into a set chord progression. Another possible reason for the relative failure of the session is related to the affordances of the harmonica. As stated in the section concerning my Western Swing-tuned harmonica, the major supertonic is, when playing in second position on a diatonic harmonica, quite challenging.32 Both the tonic and the third of the chord are bent notes, i.e., notes which are not available on the harmonica simply by exhaling or inhaling, hence, an extended technique is required. This very limitation is why I designed the Western Swing-tuned harmonica, but unfortunately, I did not use that tuning in this particular session. In other words, playing the major supertonic with a regular country-tuned harmonica has its limitations, and this I believe to be one reason why I was having trouble coming up with creative material in this session. I am not saying that it cannot be done, Charlie McCoy has played very well over a major supertonic chord countless times, however, in this session, it was an obstacle for me.

Having examined the difficulties that I encountered in my creative process, I will now direct my focus to my harmonica students and consider the challenges they experienced.

My Harmonica Students

In this section I will describe my HME study with harmonica students. This study resonates well with the goal of the REACT training school, which aimed to encourage artistic creation rather than uncritical imitation (as discussed in Chapter 4 in this book). My goal was not only that students would learn from and be inspired by the transcription of harmonica recordings but that they would not stop there. The aim was to create original material, based on the transcription and imitation. This was, however, not easy for the students, so in this section I will focus on the challenges they encountered. They are, as we shall see, quite different from the challenges I experienced. The above-described method of deliberate transformation of individual voice has constituted my central artistic method. Since this method was found to be productive and useful to me, I have sought to further explore its possibilities for my teaching in HME. However, since my project took place over the timespan of several years, and the students would be working with this concept in a 7.5 credit course, I had to delimit their endeavour. In my artistic research project, I aimed to transform my artistic voice, which would have been a bit ambitious to achieve in a single course. Hence, I chose to focus on the process of using transcription and imitation as a springboard for artistic creation. In order to explore this further, I created this single-subject course for harmonica students with the aim of exploring how the process of transcription may lead to the formation of original licks. I have conducted one study with five students and a second study with four students.

The course was set up so that the students would do what I have done in my artistic research project, although on a much smaller scale. They were to choose at least one harmonica solo to transcribe. Allowing them to choose solos, as opposed to me selecting the solos for them, was important to ensure that student autonomy played a major role in the course. They chose solos which they are particularly fond of, thus increasing their motivation to devote the many hours which are necessary to transcribe the music played. In the first study, two of the students chose one solo, two chose two solos, and one chose three solos. In the second study, all students chose one solo each. During the transcription process, they were guided by me; they sent me their transcriptions, and I provided them with feedback. Then they had another go at the transcription based on my feedback. After that, we agreed on a final version, which they now had the task of learning to play, along with the original recording, as well as they could. At this point in the course, they are strictly working with imitation. The goal of this process is twofold, 1) they improve their playing technique while striving to play as close to the original as possible. This process allows the students a chance to find the areas where they need to improve. 2) The imitation stage gives them the opportunity to, at least partly, embody the original solo. I provided them with feedback during this process as well. This feedback was mostly concerned with technical advice, e.g., how to perform certain phrases on the harmonica, which techniques to use, and so on. When they played the transcription to the best of their ability, we moved on to the next stage of the course where they chose at least three favourite licks from their transcriptions. Once again, it was important for student autonomy that they choose the licks they wanted to work with. The students were then given the task of creating variations on these licks, i.e., new licks based on the originals from their transcriptions. We initially discussed various possible strategies to create variations, both based on available literature as well as my own experiences of this process.33

Preliminary results indicate that this is a fruitful method, however, there are challenges which need to be addressed. It is at this point important to point out that the students who have participated in this study are not enrolled in our regular bachelor’s or master’s programmes, simply because we have no harmonica students in those programmes at present. This entails a few implications: 1) Students who are in the midst of a university education are quite used to reflecting on their own learning process, since this is a natural part of many courses. The harmonica students in my study are not currently active as full-time university students, therefore they tend to be unaccustomed to reflecting on their own learning process. This is a skill which needs practice, and it is difficult to achieve proficiency at this during the rather short time span of a 7.5 credit course.34 This possible lack of reflective skill may have affected the feedback I received from them in my interviews. 2) The level of playing skills was quite varied amongst these students, and the first study indicated that this type of voice development benefits from a rather high level of instrumental skill. 3) Since eight of these nine students lack a formal music education, they are comfortable with an informal learning situation. A student in our regular bachelor’s programmes might feel that a course like this is more informal that what they are used to, since the outcome is not clearly defined in advance.35 However, several of these students spoke of the value of the high level of structure they imposed on their practising during the course.

Another important aspect is the students desire to actually come up with original material. This is not the goal of every student; some are quite content with learning to play a solo as closely to the original recording as they are capable of. After learning to play that solo, some students had no desire to further explore the possibilities of creating original licks inspired by the transcriptions. They only did so because it was required in the course.

There were a lot of challenges for the students during the course, the hardest and most interesting being the creation of new licks. Three main challenges were brought forth by the students:

Challenge A: Trying to Improve a Lick which is Already Great

All students expressed, in different ways, that it was almost overwhelming to try to create something new from a material which was, in their view, already perfect. They had chosen a favourite solo to transcribe, then selected their very favourite phrases, or licks, from that solo. They felt almost intimidated by the perfection of the original lick, just the thought of changing it ever so slightly was almost considered blasphemy. Student A said ‘How can I change this? This is fantastic. Anything I will do [to change the lick] feels like it would just trash this song’.36 This implies a fear of destroying something beautiful and replacing it with something of perceived lesser beauty. As student D put it: ‘It’s good the way it is’.37

Challenge B: All the Great Ideas have Already been Played and Recorded

Student D said that ‘It’s hard to come up with something which hasn’t already been done, because the stuff that has been done earlier, you know they sound good…’.38 It is clear to me, from the interviews and lessons I had with student D, that s/he has studied the genre, in this case blues, well. S/he would quite often refer to various influential blues harmonica players and what they typically play on recordings. This is a knowledge which can be both a blessing and a curse. It is a blessing since it means that you, through extensive listening, know what is appropriate to play in a traditional blues, and the licks you come up with are going to sound true to the genre. It is, perhaps, simultaneously a curse, since this knowledge might make you compare everything you play with that produced by masters of the genre. Or it might lead you to be guided by your inner hearing and play someone else’s lick when trying to create something original. As Karin Johansson writes, ‘The relationship between artistic independence and the preservation of traditions can be a difficult topic to handle on a personal level.’39

Challenge C: Falling into Old Habits

When trying to change the original lick, there is a risk of falling into old habits and playing what you usually do, hence nothing new is brought to the table. Student B refers to this challenge, stating that it is hard to come up with something original from a great lick, since ‘…In a way you have your own vocabulary, your style […] Then [when you try to come up with an original version of the lick] it just becomes that stuff you usually play […] You have your little toolbox’.40

Discussion

Both my students and I found the method of transcription and imitation to be a prosperous springboard to create original material. This could be used to initiate a process which ultimately strives towards finding one’s own voice. The informal learning, which was an important part of the process, granted the students autonomy since they, in many ways, were masters of their own learning. They were allowed to choose the songs they transcribed, and they chose their favourite licks to use as models in the lick-creation process. As Phil Jenkins states, ‘Informal learning implies a self-motivated effort to reach competence in some task or skill’.41 In her studies on how popular music is learned, Lucy Green points to the increase in motivation when the students are allowed to work with music of their choice.42 I feel that it is especially important to include a high degree of informal learning when you work with genres such as Blues and Country music, which are ones all the students in my study did. These genres, just like early Jazz, have a history of informal learning which we should respect, even when we include them in HME. In the interviews, student C commented on the freedom to choose the material to transcribe, thinking it an excellent way to start this process. However, the students were not always realistic in their choices, what they wanted to learn was sometimes far above their own playing level. That is when my role as a teacher becomes important, I could advise them to choose a recording which was at a more appropriate level for them.

I have used a fair amount of informal learning in these harmonica courses, but it is important to note that the traditional formal teaching and learning methods have merit, too. All of the students needed help with the transcriptions, and I spent time with each student working on and discussing different playing techniques used by the harmonica players in the original recordings. During the process of transcription and imitation, the students developed their metacognitive skills in that they identified their own weaknesses when being unable to play, or indeed hear, parts of the solos. This often resulted in me giving them exercises to work on in order to improve their technique. Formal learning with a well-defined goal indeed. Research points to the importance of finding a balance between formal and informal learning, or ‘transfer learning and transformational learning’, as Gemma Carey and Catherine Grant refer to this type of learning.43 Also interesting thing to note is that I, who have worked as a university lecturer for the better part of the past twenty years, consider this course to contain a high amount of informal learning. However, that view was not shared by all students. Those who were completely self-taught found that one benefit of this course was that it inspired them to become more structured in their practising routine, i.e., to impose a higher amount of what could be considered formal learning with explicit goals.

Though the students greatly appreciated the autonomy they were allowed, I was surprised by one aspect in the interviews. The part of the course, which in my mind was the most autonomous, i.e., the lick-generation process, was not viewed as such by all students. They experienced ownership of their learning when they worked with the transcriptions of their own choice, but when it came time to create licks of their own, some of the students paradoxically felt constrained. The perceived lack of autonomy was that they had to create licks of their own. Though they were free to create what they wanted, if they wanted to pass the course, they were not free to refrain from creating new licks. As Smilde writes, ‘Perhaps the most important aspect [of lifelong learning strategies] is that this is never a matter of simply giving out ready-made recipes: it starts with considering the mindset and identity of each individual.’44

If I would have had more time with the students, I could have implemented the lick-generation process at different (later) stages in their education, some earlier than others. This perceived lack of autonomy relates to their (lack of) desire to create new, original materiel. As discussed earlier, most of the students would have been perfectly happy if the course had only contained transcription of solos and getting guidance from me concerning how to play the solos. This likely has to do with where they are in their musical journey. Jenkins states that ‘like any other creative activity, the quality of what one creates greatly depends on the quality of one’s experiences, and here, perhaps more than in other informal techniques, skill obtained from formal instruction will affect quality as well’.45 Once again, this points to the need of a balance of formal and informal learning. Susan Hallam writes that ‘students need to acquire this “musical” knowledge base prior to or concurrently with knowledge about specific learning and support strategies’.46 So, my ambition to provide these students with lifelong-learning strategies and autonomy, was, in a way, a little premature. Most of these students would need to work more with formal learning concerning transcription and technical skill on the harmonica. This formal learning can, of course, go hand in hand with informal learning and autonomy, allowing the students to choose what they want to learn. It is my job to guide them and inspire them to search for their own voice, not to be content to be a copycat. Carl Holmgren writes, regarding the development of a personal artistic voice, that:

given that a personal artistic voice is a complex amalgamation that demands an intricate interplay between philosophical and aesthetic judgments and stances, as well as an adequate technical command on the instrument, it is not possible to develop merely through imitation.47

So, during the formal studies of transcription and imitation, it might be fruitful to carefully add the lick-generation process, bit by bit, aiming towards the creation of a unique voice.

Granted, we all had our difficulties along the way. My challenges deal exclusively with lack of inspiration due to the original lick being either too rigid or too loose in its structure. The less-productive licks were either not clearly enough defined to provide me with a solid foundation to experiment with, or too constrained, thus inhibiting creativity. On the other hand, the students’ challenges mainly concerned what might be considered a misconception, i.e., that you are supposed to create something of higher aesthetic value than the original recording. I will return to that thought later, but first I would like to point out two important differences between me and the students, one difference concerning our sources of inspiration. They based their lick-creation sessions strictly on discrete licks from the solo(s) they had chosen. My variations were based on what I call ‘lick-families’, i.e., licks that had many recorded variations. One way of viewing this is that the licks I based my variations on had, in most cases, already been altered. McCoy had, in fact, made plenty of his own variations, which inspired my own investigations. However, since we were limited by the time span of a short course during one semester, there was obviously not enough time for the students to find such a pool of lick variants to work with. Another difference between the students and myself is where we are as harmonica players and musicians. I am playing at a professional level, and they are not quite there (yet). Hallam’s research indicates that professional musicians have developed considerable metacognitive skills, such as learning of learning, simply because they must in the competitive world in which they work.48 These types of skills were present among advanced students, too, in Hallam’s study, but not as well developed.

Challenges A and B refer to the students’ experience of not being able to better the originals. This I would argue is a misconception, since the goal is not to try to improve on the licks you love, the object is to let them guide you in your search for your own voice. This requires that you lose your ego and stop comparing yourself with the original, or as student D put it: ‘That you don’t care so much, that you just go.’49 Let the masters of past and present inspire you, allow their voices to be heard in your own playing. To me, copying what someone else has done with the aim of finding your own voice is the utmost sign of respect. Regardless of how you alter the lick, you are not going to damage it. The original recording will remain the same. It is my role as a teacher to help the students to get into this mindset: they should not see their task as trying to improve on something beautiful, rather, to see themselves reflected in that beauty. This is an important part of the process, where I, as the teacher, am much needed as a mediator between the original recordings and the students.

Although the comparison with the solos on the recordings clearly is an obstacle for the students, there is something beautiful about Challenges A and B. They feel intimidated because they love and respect the tradition in which they are working. I feel the same way about McCoy’s playing, it does not need improvement. However, if I am to play licks I have learned from McCoy, they will benefit from the addition of my own voice. After all, McCoy plays McCoy better than anyone else. Mike Caldwell stated in our interview that he wanted to add his own personality to the licks, careful not to claim his ideas to be better than McCoy’s: ‘It’s ok to play it a little different than Charlie, because it’s me.’50

Challenge C, on the other hand, deals with the risk of falling into old habits, thus preventing yourself from letting the source of your inspiration guide you to new solutions. There is certainly a tension here, when you want to bring yourself into the lick, to put your own stamp on it, you are running the risk of moving too far from your source of inspiration, i.e., the original lick. By ‘too far’, I mean that you end up playing one of your own clichés without a trace of the original, which was meant to inspire you to come up with something of your own. One might say that the point is to meet halfway or, rather, to bring yourself into the lick and then go beyond. However, you need to be careful not to leave it behind completely. In your new lick, you should be able to, in some way, trace your way back to the original lick. In other words, you should be able to explain to yourself why you made the choices you made. On the other hand, there is certainly nothing wrong with coming up with a lick that in no way resembles the original, as long as it is new to yourself, and not one of the licks you already had in your little toolbox, as student B put it.

When helping students to strive towards the goal of creating their own voice, one powerful tool is reflection.51 During the interviews, both individual and in group form, the students were given plenty of opportunity to reflect on their own learning. These reflections not only increased their autonomy and strengthened their lifelong-learning strategies but also helped them in their voice development. Moberg and Georgii-Hemming write that ‘students must reflexively become aware of who they are, what musical preferences they have, and where they are located in the musical field’ in order to develop artistic freedom.52 This resonates well with my study, since the students reflected on their own abilities to copy other harmonica players in their field. Their musical preferences were front and centre in the course, since they chose the material we worked with. They also reflected on these preferences when I interviewed them regarding why they chose certain licks. I would argue that one important step towards finding your own voice is the very choice of solos and licks. There are reasons why the students chose what they did; student A said that certain licks ‘lay well in my mouth’ when explaining why s/he chose to work with those licks.53 There is something in these solos and licks which resonates within the students, something which points to who they are. This very resonance is what they need to pay attention to, to develop, to nurture, and adapt into their own playing. Through their choices of solos, they have begun the journey of identifying what they really love, and this, I believe, is the way to find out not only who you are but also who you want to be as a musician.

As far as the challenges we all experienced, it is interesting to note that my challenges and the students’ challenges are entirely different. I never felt intimidated by the original recording, only inspired. One possible explanation for this might be that I was able to play the transcriptions along with the recordings, sounding close to the original, without the need of slowing the speed of the recording down. However, the students were all, more or less, struggling to play their chosen solos and licks. They all had to slow the recordings down and were still, in many aspects, not sounding like the original. There is nothing remarkable about that: I have spent thousands of hours honing my skills at aural transcriptions; they have not. Not yet anyway.

In sum, the preliminary results of my educational study encourage me to continue working in this manner. That is, to apply the knowledge I gain through my artistic research and my artistic practice in my teaching in HME. There is nothing particularly novel about that ambition, my colleagues at my university do, to greater or lesser extent, precisely that. However, when you formalize this process as you do in a research project, the potential gain increases. Granted, there will always be a need to adapt the methods used in your artistic research when applying them within the framework of HME. For example, to adjust to the timeframe of a single course, a semester or even the three-year span of a bachelor’s programme. Also, it will be necessary to adapt my methods to meet the students where they are, and to meet the needs of the students. Regarding the various challenges I have outlined, I do not necessarily see a need to eliminate these challenges. On the contrary, working with these challenges is what gives the students opportunity to grow, become autonomous, and to work towards fostering an individual voice. Trying to work around or to eliminate the challenges might mean less opportunity for learning.

In short, I am confident that all students, teachers, and researchers will benefit from HME being informed by up-to-date artistic research. It is my hope that presenting what I am doing will inspire teachers in HME to do artistic research, as well as artistic researchers to apply their findings in HME.

References

Aebersold, Jamie, How to Play Jazz and Improvise (New Albany, NY: Jamey Aebersold Jazz Inc, 1992)

Bäckman, Mikael, ‘The Real McCoy. Tracking the Development of Charlie McCoy’s Playing Style’, International Country Music Journal (2022), 184–231

Bäckman, Mikael, ‘In Search of My Voice’, Music & Practice, 10 (2023), unpaginated, https://doi.org/10.32063/1012

Berild Lundblad, Niklas, and Fredrik Stjernberg, Frågvisare. Människans Viktigaste Verktyg (Stockholm: Volante, 2021)

Berliner, Paul F, Thinking in Jazz. The Infinite Art of Improvisation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994)

Blom, Diana, Dawn Bennett, and David Wright, ‘How Artists Working in Academia View Artistic Practice as Research: Implications for Tertiary Music Education’, International Journal of Music Education, 29(4), (2011), 359–73, https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761411421088

Caldwell, Mike, interview, conducted 3 September 2020

Carey, Gemma and Grant, Catherine, ‘Teachers of Instruments, or Teachers as Instruments? From Transfer to Transformative Approaches to One-To-One Pedagogy’ in Becoming and Being a Musician: The Role of Creativity in Students’ Learning and Identity Formation, Proceeding of the 20th International Seminar of the ISME Commission on the Education of the Professional Musician, July 2013, https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2916.3204

Craenen, Paul, Composing Under the Skin: The Music-Making Body at the Composer’s Desk (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014)

Frisk, Henrik and Östersjö, Stefan, (re)Thinking Improvisation: Artistic Explorations and Conceptual Writing (Lund University, Elanders Sverige AB, 2013)

Gibson, James J., The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (New York: Psychology Press, 1979)

Goldsmith, Margie, Masters of Harmonica (Alpharetta, GA: Mountain Arbor Press, 2019)

Green, Lucy, How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead for Music Education (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002)

Hallam, Susan, ‘The Development of Metacognition in Musicians: Implications for Education’, British Journal of Music Education, 18.1 (2001), 27–39, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051701000122

Hess, Juliet, ‘Finding the “both/and”: Balancing Informal and Formal Music Learning’, International Journal of Music Education, 38:3 (2020), 441–55, https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761420917226

Holmgren, Carl, ‘Dialogue Lost? Teaching Musical Interpretation of Western Classical Music in Higher Education’, PhD thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2022.

Hultberg, Cecilia K., ‘Artistic Processes in Music Performance. A Research Area Calling for Inter-Disciplinary Collaboration’, Swedish Journal of Music Research/Svensk Tidskrift för Musikforskning, 95 (2013), 79–94

Jenkins, Phil, ‘Project Muse: Formal and Informal Music Educational Practices’, Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19:2 (2011), 179–97, https://doi.org/10.2979/philmusieducrevi.19.2.179

Johansson, Karin, ‘Undergraduate Students’ Ownership of Musical Learning: Obstacles and Options in One-To-One Teaching’, British Journal of Music Education, 30:2 (2013), 277–95, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0265051713000120

Leman, Marc; Luc Nijs, Pieter-Jan Maes, and Edith Van Dyck, ‘What is Embodied Music Cognition?’, in Springer Handbook of systematic Musicology, ed. by Rolf Bader (Berlin: Springer, 2017), pp. 747–60

Moberg, Nadia and Eva Georgii-Hemming, ‘Musicianship – Discursive Constructions of Autonomy and Independence within Music Performance Programmes’, Proceedings of the Conference ‘Becoming Musicians. Student Involvement and Teacher Collaboration in Higher Music Education’, Oslo, October 2018, ed. by Stefan Gies and Jon Helge Sætre, NMH publications, 2019, p. 67–88

Pivec, Matt, ‘Maximizing the Benefits of Solo Transcription’, JazzEd, January (2008), 23–26

Roe, Paul, ‘A Phenomenology of Collaboration in Contemporary Composition and Performance’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of York, 2007)

Sadolin, Catherine, Complete Vocal Technique (Copenhagen: CVI publications, 2021)

Sandell, Sten, ’På Insidan Av Tystnaden: En Undersökning’ (PhD thesis, Göteborgs Universitet, Art Monitor, 2013)

Smilde, Rineke, ‘Change and the Challenges of Lifelong Learning’, in Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, ed. by Dawn Bennett (Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing, 2012), pp. 99–123

Wilf, Eitan, School for Cool: The Academic Jazz Programme and the Paradox of Institutionalized Creativity (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2014)

Östersjö, Stefan, ‘Shut Up ‘N’ Play: Negotiating the Musical Work’ (PhD thesis, Lund University, Media-Tryck, 2008)

1 Concerning study of individual process, see for example Sten Sandell, ’På Insidan Av Tystnaden: En Undersökning’ (PhD thesis, Göteborgs Universitet, Art Monitor, 2013). See also Paul Craenen, Composing Under the Skin: The Music-Making Body at the Composer’s Desk (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014).

2 Concerning study of collaborative process, see Henrik Frisk and Stefan Östersjö, (re)Thinking Improvisation: Artistic Explorations and Conceptual Writing (Lund University, Elanders Sverige AB, 2013). Paul Roe, ‘A Phenomenology of Collaboration in Contemporary Composition and Performance’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of York, 2007). Stefan Östersjö, ‘Shut Up ‘N’ Play: Negotiating the Musical Work’ (PhD thesis, Lund University, Media-Tryck, 2008).

3 Diana Blom, Dawn Bennett and David Wright, ‘How Artists Working in Academia View Artistic Practice as Research: Implications for Tertiary Music Education’, International Journal of Music Education, 29(4), (2011), 359–73 (p. 369), https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761411421088

4 European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education, ‘London Communiqué: Towards the European Higher Education Area: Responding to Changes in a Globalised World’ (2007), http://www.ehea.info/Upload/document/ministerial_declarations/2007_London_Communique_English_588697.pdf, p. 2.

5 See, for example, Cecilia K. Hultberg, ‘Artistic Processes in Music Performance. A Research Area Calling for Inter-Disciplinary Collaboration’, Swedish Journal of Music Research/Svensk Tidskrift för Musikforskning, 95 (2013), 79-94. See also Phil Jenkins, ‘Project Muse: Formal and Informal Music Educational Practices’, Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19:2 (2011), 179–97.

6 Phil Jenkins, ‘Project Muse: Formal and Informal Music Educational Practices’, Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19.2 (2011), p. 179-97.

7 Susan Hallam, ‘The Development of Metacognition in Musicians: Implications for Education’, British Journal of Music Education, 18.1 (2001), p. 27–39.

8 Nadia Moberg and Eva Georgii-Hemming, ‘Musicianship—discursive constructions of autonomy and independence within music performance programmes’. Proceedings of the Conference ‘Becoming Musicians. Student Involvement and Teacher Collaboration in Higher Music Education’, Oslo, October 2018, ed. by Stefan Gies and Jon Helge Sætre ([n.p.]: NMH publications, 2019) pp. 67–88.

9 Rineke Smilde, ‘Change and the Challenges of Lifelong Learning’, in Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, ed. by Dawn Bennett (Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing, 2012), p. 99–123.

10 This artistic research project was developed and carried out for my PhD thesis in Musical Performance.

11 Juliet Hess, ‘Finding the “both/and”: Balancing informal and formal music learning’, International Journal of Music Education, 38:3 (2020), 441–55 (p. 451).

12 See, for example, Paul F. Berliner, Thinking in Jazz. The Infinite Art of Improvisation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

13 Jenkins, p. 195.

14 See, for example, Eitan Wilf, School for Cool: The Academic Jazz Programme and the Paradox of Institutionalized Creativity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

15 Marc Leman, Luc Nijs, Pieter-Jan Maes and Edith Van Dyck, ‘What is Embodied Music Cognition?’, Springer Handbook of systematic Musicology, ed. Rolf Bader (Berlin: Springer, 2017), 747–60.

16 Naomi Cumming, The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000).

17 Mikael Bäckman, ‘In Search of My Voice’, Music & Practice, 10 (2023), unpaginated.

18 James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (New York: Psychology Press, 1979).

19 I have worked as a lecturer at The School of Music in Piteå at the Luleå University of Technology, Sweden, since 2005, teaching harmonica, music history, ensemble, and music theory.

20 Margie Goldsmith, Masters of Harmonica (Alpharetta, GA: Mountain Arbor Press, 2019), p. 165.

21 Not including his work as a session player during this time period.

22 Examples of this documentation are stored in the online ‘Research Catalogue’, an international and non-commercial database for artistic research. See https://www.researchcatalogue.net/profile/show-exposition?exposition=1964122

23 Mikael Bäckman, ‘The Real McCoy. Tracking the Development of Charlie McCoy’s Playing Style’, International Country Music Journal (2022), 184–231.

24 Mikael Bäckman, ‘In Search of My Voice’, Music and Practice, 10 (2023), unpaginated, https://doi.org/10.32063/1012

25 For examples of documentation of my playing during my artistic research project, see the following YouTube videos: ‘Turn the Cards Slowly’, uploaded by BD Pop, 11 March 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VChN5y_dKI; ‘Roly Poly’, 11 March 2021, uploaded by BD Pop, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAf8VJibMMw; ‘Turn the Cards Slowly’, uploaded by John Henry, 12 November 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zfTqqOYsn-Q; ‘Flip That Rock’, uploaded by John Henry, 12 November 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4QW9AcAWB4. Also, for the main artistic output of my PhD thesis, see John Henry, ‘Lucky Luck’, Spotify album, uploaded by John Henry, https://open.spotify.com/artist/2V9BG3gxbAY6QZEQ76c7tm?si=4yMsHA_0RL2P9Zv5t-ryGA

26 Niklas Berild Lundblad and Fredrik Stjernberg, Frågvisare. Människans viktigaste verktyg (Stockholm: Volante, 2021), p. 44.

27 Ibid.

28 ‘Yodeling is a series of rapid changes (breaks) between Overdrive in fuller density and Neutral in falsetto. These singers often use note leaps of sixths or sevenths.’ Catherine Sadolin, Complete Vocal Technique (Copenhagen: CVI Publications, 2021), p. 306.

29 Robert Bonfiglio, b. 1950, is the world’s premier classical harmonica player.

30 For example, an A major chord in the key of G major.

31 Not unlike what you can find in a how-to-play-jazz instruction book. See, for example, Jamie Aebersold, How to Play Jazz and Improvise (New Albany, NY: Jamey Aebersold Jazz Inc, 1992).

32 Positions are the term used by harmonica players when referring to playing diatonic harmonica in different keys. This is most often done by playing in the various modes which the major scale affords. The most commonly used positions are 2nd (mixolydian), 1st (ionian), and 3rd (dorian).

33 See, for example, Paul F. Berliner, Thinking in Jazz. The Infinite Art of Improvisation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994) and Matt Pivec, ‘Maximizing the Benefits of Solo Transcription’, JazzEd, January (2008), 23–26.

34 A student is expected to put in 200 hours of work for a 7.5 credit course. Approximately 12 hours consisted of workshops and individual lessons, the remaining time is devoted to individual practice.

35 See Phil Jenkins, ‘Project Muse: Formal and Informal Music Educational Practices’, Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19:2 (2011), 179–97.

36 Group interview, my translation. Original quotation in Swedish: ’Hur ska man kunna göra om det här, det här är ju fantastiskt. Allt jag kommer göra känns ju som att det…bara krascha den här låten.’

37 Individual interview, my translation. Original quotation in Swedish: ’Den är ju så bra som den är.’

38 Group interview, my translation. Original quotation in Swedish: ’Det är svårt att hitta på något som inte är gjort tidigare. För de grejorna som är gjorda tidigare dom vet man ju att de låter bra många gånger.’

39 Karin Johansson, ‘Undergraduate students’ ownership of musical learning: obstacles and options in one-to-tone teaching’, British Journal of Music Education, 30.2 (2013), 277–95 (p. 279).

40 Group interview, my translation. Original quotation in Swedish: ’Man har ju på något sätt sitt vokabulär och sin stil […] Då blev det ju det där vanliga töntet som man brukar hålla på med […] Man har ju sin lilla verktygslåda.’

41 Jenkins, p. 181.

42 Lucy Green, How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead for Music Education (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002).

43 Gemma Carey and Catherine Grant, ‘Teachers of instruments, or teachers as instruments? From transfer to transformative approaches to one-to-one pedagogy’, in Becoming and Being a Musician: The Role of Creativity in Students’ Learning and Identity Formation, Proceeding of the 20th International Seminar of the ISME Commission on the Education of the Professional Musician, July 2013, https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2916.3204; see also Hess.

44 Smilde, p. 115.

45 Jenkins, p. 195.

46 Susan Hallam, ‘The Development of Metacognition in Musicians: Implications for Education’, British Journal of Music Education, 18.1 (2001), 27–39 (p. 21).

47 Carl Holmgren, ‘Dialogue Lost? Teaching Musical Interpretation of Western Classical Music in Higher Education’, PhD thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2022, p. 50.

48 Hallam.

49 Individual interview, my translation. Original quotation in Swedish: ’Att man inte bryr sig så mycket, att man bara kö.’

50 Mike Caldwell interview.

51 See, for example, Moberg and Georgii-Hemming.

52 Moberg and Georgii-Hemming, p. 81, emphasis in original.

53 Group interview, my translation. Original quotation in Swedish: ’…att det låg bra i munnen.’