4. Teaching Musical Performance from an Artistic Research-Based Approach

Reporting on a Pedagogical Intervention in Portugal

© 2024 Gilvano Dalagna et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0398.05

Introduction

This book chapter reports on the outcomes of the second REACT training school, a pedagogical intervention to test an artistic research-based approach to teaching and learning music performance. This extracurricular course was created at the University of Aveiro, leading institution in the strategic REACT project. The intervention was tested as extracurricular to pilot interventions, solutions, and feedback prior to formalising such changes within the validated curriculum. The chapter is structured in four parts. The first part discusses existing practices of music performance teaching and learning in European higher education institutions. This part explores the historical development of music performance education and the influence of the values and expectations established in the context of the nineteenth-century Western Music Conservatoire and its traditional master-apprentice one-to-one pedagogical model. The consequences of this model, referred to here as ‘the conservatoire model’, are outlined, along with a summary of the career requirements of music performance professionals, in ‘Artistic Careers in Music: Stakeholders Requirements Report’, the first output published by the consortium of the REACT project.1 Connections are drawn between the conservatoire model and artistic research in order to inform innovative practices and launch an alternative pedagogical intervention. In the second part, the implementation of the pedagogical intervention at a Portuguese university is described. Details about types of activities and contents included in the programme, selection of participants, data collection (from focus groups interviews), and data analysis are presented. The results are presented in the third part of the chapter. They are based on students’ collected feedback on their experiences regarding their participation in the intervention. We utilise the student voice in order to assess the effectiveness of the training school itself. An account of the thematic analysis and its results are presented through the sharing of student voices from the focus-group interviews. In the final section, the theoretical and pedagogical implications of the intervention are evaluated, with reference to the student feedback and the process of the implementation undertaken. We also address the methodological limitations of the study and, finally, propose suggested directions for future research.

Background

Since the nineteenth century, two different ways of conceptualising the teaching and learning of music performance in higher education have been established in mainland Europe. Higher education institutions are considered to have two approaches: that of universities, which is described as academic, and that of conservatoires, which is described as performance based.2,3 In practice, many university courses do include performance, but they are structured differently, and likewise, conservatoires do include academic programmes, but for a smaller modular proportion. Moreover, university-degree courses, for the most part, are three years, while conservatoire courses are usually four years in length (referring to full-time registration). The Bologna model (see further below), however, posits the structure of three years of undergraduate study, plus two years of postgraduate taught master’s study. Despite the apparent differences, these two educational environments—university departments and conservatoires—have similarities. Both aim to create a student-centred approach, but they vary in the hours each dedicates to performance, particularly to one-to-one teaching, referred to here as the master-apprentice model. Conservatoires usually dedicate a smaller percentage of their students’ time to theoretical courses. 4,5,6 Universities, on the other hand, usually tend to reduce the time students dedicate to performance practice.7 While university music programmes usually offer a variety of modules such as musicology, performance studies, music technology, composition, and music education, conservatoires also offer these, but their focus is on what these subjects can help improve performance.

Several institutions continue to train young musicians primarily using a curriculum built on principles institutionalised in the Paris Conservatoire in the nineteenth century.8 These principles are deduced from a view of performance as essentially a question of interpreting a composer’s score. This understanding aligns with the paradigmatic influence of werktreue, which led to the development of the following practices: (i) specialism in a single instrument or vocal type; (ii) a pursuit of virtuosic technique; (iii) focus on accurately performing what is written in the score; (iv) a standardisation of exams and prizes as a means by which to monitor the quality of music performance; (v) teacher-directed as opposed to student-centred teaching; and (vi) dominance of Western art music.9 This teaching paradigm encourages performance students to interpret pre-existing scores in line with traditional and hegemonic performance practices.10 The excessive focus on imitation moves away from encouraging student-centred learning, where the voice of the students’ own creativity and critical thinking is made the focal point.

The conservatoire model has also influenced how students envision their future careers in music industries, largely as performers in dominant classical music institutions.11 Historical evidence from the last decade suggests that students have had some difficulty finding ways to relate their practice with their creativity,12,13 due to the excessive focus on developing competences. Other authors, more radically, have suggested that the conservatoire model neither prepares students for their likely freelance futures nor helps them to achieve their artistic aspirations, since the professional music field is changing faster than training programmes. This may create a tension between the skills prioritised and what is needed to sustain a career in music.14 The perceived tension highlights the importance of continuing to design approaches that effectively equip musicians for sustainable careers and integrate the student-voice in such design processes.15

This gap between the conservatoire model and career demands motivated the development of a strategic partnership of REACT (as discussed in the introduction to this book). The consortium of institutions in the aforementioned countries conducted a cross-European study with the aim of identifying current artistic career demands in the music-performance industry. This interview-based study involved a large number of stakeholders, and the proportions are different for each case study, but all comprise professional performers, students, teachers, artistic directors, career coaches, heads of music departments, composers, and music producers. The analysis revealed common challenges and demands for an artistic career, but also some differences across the countries represented. The final report summarised the data collected in the qualitative study and a literature review. The authors propose a list of professional requirements and a number of suggestions which would enable HME to respond to referred requirements (see Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Professional competencies identified in the synthetic analysis.16

In the following table, a triangulation involving the results of the cross-European study and a synthesis of the existing literature review on career development is presented. Table 4.2 shows a more detailed list of demands that integrates other competencies beyond technical and interpretative skills.

|

Cross-European study |

Synthesis of the Literature Review |

|

|

Table 4.2. Artistic career demands in music performance.

One can argue that the list of demands is vast and complicated to address through a single strategy. However, Pamela Burnard,27 Mary Lennon, and Geoffrey Reed28 have suggested that creativity and critical thinking should be highlighted in order to develop individual creative voices. Further, our report29 identifies two fundamental approaches to supporting the transition from the role of student to professional musician: institutions must create a student-centred curriculum which enables their voices to speak (see Chapters 11 and 12 in this book) and project-based learning informed by artistic research practices (see Chapters 1 and 3 in this book). The currency of the aspects listed in the table has been evident throughout the process of adapting pedagogy in HME in accordance with the Bologna Declaration.30,31 As discussed above, HME, have historically been built on the conservatoire model and, therefore, have focused on one-to-one teaching.32 Ford and Sloboda observe that HME have faced several managerial challenges to justify the financial viability of this one-to-one teaching model, notably from a social and political perspective, when resources are limited and costs increasing, and where inclusive practices and widening participation are central aims for regulators.33

Driven by an aim to create a unified European Higher Education sector, the Bologna Declaration encouraged many conservatoires and universities to rethink their pedagogical structure and, consequently, their relationship with the music industries, as well as to adhere to the principle that each educational area should be supported by research.34,35,36 The agreement instigated a process of developing research cultures across all HME institutions. In this process, artistic research has emerged as an important factor in the creation of such research environments that meaningfully include research in music performance.37,38

The challenge of the Bologna Declaration, of grounding all education on research-led teaching, was to articulate how research findings were possible in practice. This turmoil was grounded in how artists felt the need to justify their artistic practice as research and could be valued as a contribution to knowledge.39

Artistic research has emerged as a solution to this state of affairs, since it has the potential to ground arts education in a student-centred, experiential way of learning, with a basis in research practice. As such, it has facilitated novel ways of teaching and assessing (see Chapter 12). The term ‘generative’40 describes artistic research as an alternative to the existing qualitative and quantitative paradigm: ‘artwork embodies research findings which are symbolically expressed, though not expressed through numbers and words’.41 The inadequacy of scientific research42 to ground arts education in practice could finally be overcome by an epistemological approach through artistic research as it enables a somatic experience within the context of the art world, often described as ‘Practice Research’.43 Artistic research offers a possibility to overcome the subject/object dichotomy of scientific research, since it allows the sharing of the artist’s subjectivity and experience in the development of a new practice (which crosses all the arts, not only music). The development of this new practice is fundamental to a student-centred approach, which engages with contextualisation, exploration, and dissemination, as shown in the REACT model (see Introduction). In addition to the potential in observing, analysing, and describing musical practices from a multidisciplinary perspective, artistic researchers critically reflect on their subjective and inter-subjective experience of artistic practice, identifying and proposing new possibilities that are conveyed through their practice in their art world.44

Artistic research is not fully integrated in all HME bodies in Europe. Only a few institutions have explored the potential of artistic research as a new paradigm in music performance teaching in its full capacity.45 It is not yet possible to grasp the impact of artistic research in the education of students in HME across the sector, though work is being done within individual institutions (see for instance Chapters 1, 3, and 11). Likewise, the impact of artistic research-informed teaching in students’ transition to professional is clear, as, in the UK, the graduate outcomes demonstrate a benefit (see Chapter 12).

REACT Training School

In the REACT project, two training schools formed a basis for experimenting with educational models based on artistic research (the first, in Norway, discussed in Chapter 10), and the second in Portugal (discussed here). Both interactions tested project-based learning pedagogical strategies and student-centred approaches through practices of artistic research in music.

This change of perspective was the main objective of these interventions. Critical thinking and creativity were core elements in the pedagogical praxis, as can be seen further on in the ‘Results’ section, where we analyse the impact of the second training school via the interviews with participants. The first core element (critical thinking) refers to a reflexive process focused on the subjectivity of each individual, while the second (creativity) refers to a process of communicating this subjectivity in academic and professional contexts.

Students were invited to conceive, develop, and publicly present an artistic project based on challenges they experience during their practice. The activities proposed by the training school aimed to assist students in this process. Thus, music performance was conceived as a creative practice and a space for problematization. Students defined the focus of their projects, and pedagogical support was provided through mentoring by consortium members.

Structure and Implementation of the 2nd REACT Training School

Building on the evaluation of the first training school (see Chapter 10), as well as the outcomes of the Stakeholders Requirement Report,46 the consortium members defined the following structure for the second training school, which encompassed four main modules:

- philosophical stance - aims to critically identify challenges in musical practice;

- exploration - aims to develop a critical creative reaction to the challenges identified in module 1;

- self-disclosure - facilitates students in making sense of their own experience to find ways to connect them with their own music making;

- social intervention - aims to explore the impact of artistic research and its potential for change in art worlds and industry.

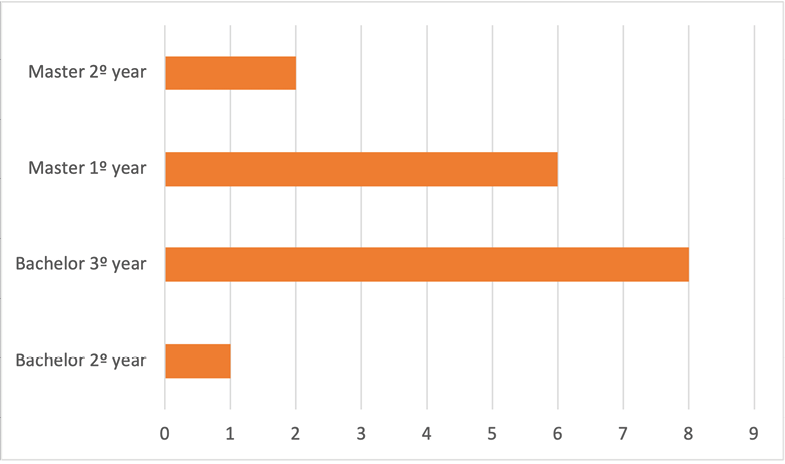

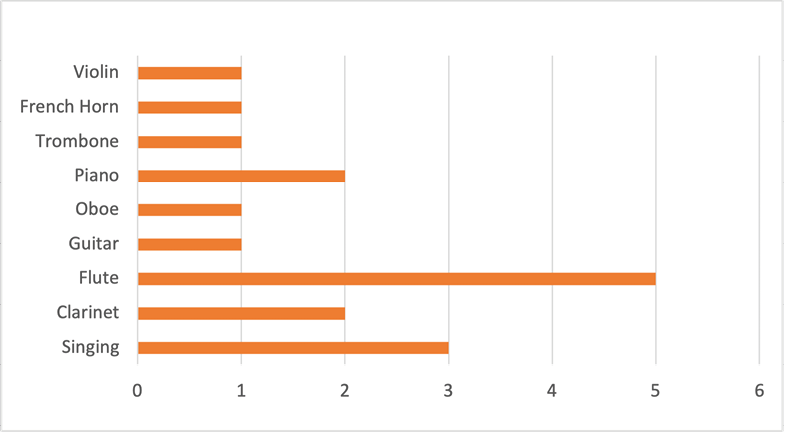

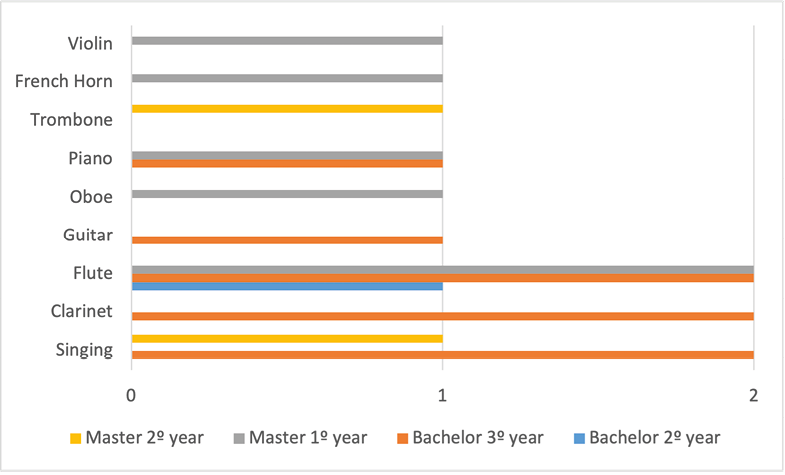

The course was held in May 2022, at the Department of Communication and Art at the University of Aveiro in Portugal. During a full teaching week (40 hours), 17 master’s and bachelor’s students (see Fig. 4.1) were involved in a total of 25 activities distributed throughout the week. Nine instrumental teachers from the department were invited to select potential student participants based on the following criteria: (i) interest in an artistic career and in developing a project of their own; (ii) some experience in research methods and developing their own career planning; (iii) sufficient performance experience to deal with this intervention; (iv) having completed 1 year of a bachelor’s programme. The three figures below show the number of students at each level (Fig. 4.1), the instruments they play (Fig. 4.2), and the correlation between the students and their instruments (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.1: Number of students by course and year of study.

Fig. 4.2: Students by instrument.

Fig. 4.3: Correlation between instruments and students.

The activities were based on the four modules previously described above. In each module, the consortium members proposed two units (that is, target topics addressed in each module) and invited feedback from others to indicate which units could be addressed in the school. In these modules, four main competencies were addressed: meaning making (A), finding one’s own artistic voice (B), developing and managing projects (C), and seeking empathy (D).

Sixteen lectures, workshops, and demonstrations of projects were proposed by eleven REACT members. All of the activities distributed across the units can be seen in Table 4.3. Between the lectures, group mentoring sessions were offered on each day.

Table 4.3. React training school structure

Data Collection and Analysis

A focus-group interview was conducted one week after the end of the training school with the aim of assessing its impact on the students’ learning and professional path.47 All students were invited to take part in the interview. It was scheduled at a time when the majority of the participants could attend. However, nine of the seventeen students declined to participate in the interview because of other commitments. We adopted a semi-structured technique to guide the group interview48 and solicit observations about the training school. The discussion centred around four questions:

- What do you think was most pertinent, for you in particular, during the week of the training school?

- How has this experience impacted on your activity as a performing musician?

- What improvements do you think are needed at the school?

- Imagining the school’s curriculum as a basis for the development of other courses, what impact could this kind of activity have on the teaching of music performance in the future?

Eight students participated in the discussion during the focus-group interview and the total length of the interview recording was one hour. We had four students in the third year of the bachelor’s degree, three in the first year of the master’s degree, and one in the second year of the master’s programme. They encompassed six instruments. The original data was recorded in Portuguese and then transcribed verbatim using the F5 software. A thematic analysis, with the aid of the software NVivo 12, was conducted through a process of coding the data, then organising them into themes and sub-themes.49 Themes and sub-themes were coded according to the four aforementioned questions that guided the interviews.50

Results

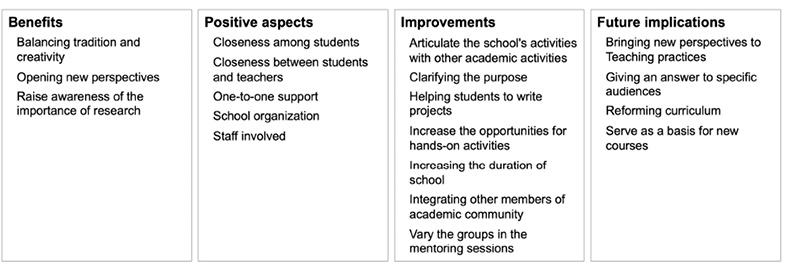

Four themes emerged in the analysis of the interview data.

- Benefits: the students’ perspectives on their knowledge development during the training school and how this impacted their way of conceiving musical practice;

- Positive aspects: students’ positive feedback on the structure, delivery, engagement, and management of the training school;

- Improvements: students’ feedback on possible changes in the structure, content, and/or pedagogical approach adopted in the training school;

- Future implications: students’ feedback on a possible impact of the training school in HEIs.

Fig. 4.4 displays the four emergent themes and their correspondent set of sub-themes. Both, themes and sub-themes, listed in the figure will be explained further throughout the description that comes next.

Fig. 4.4: Themes and their respective sub-themes identified in the data analysis of the interviews.

Benefits

Regarding the benefits, the participants talked about how the school could affect their artistic and professional path. One of the benefits mentioned during the focus-group discussion was the possibility of gradually adapting the approach proposed in the training school to the current conservatoire model. We coded this sub-theme as ‘balancing tradition and creativity’ as listed in Fig. 4.4. It appears that the school stimulated some of the students to explore creativity and take a critical standpoint towards their musical practice, exploring new interpretive possibilities in the repertoire.

P3: But I think the REACT school was a kick-start for us to start exploring creativity, something I’d never done before, and it helped me open up my horizons a lot. It doesn’t mean that now I’m going to do everything in an extremely creative way. We also (need to) follow a tradition in order to then deconstruct it, I think…

This quote summarises what all the participants ended up sharing in the interviews and is in line with the objective set by the REACT consortium for the training school. These objectives were not intended to teach artistic research methods but, rather, to provide students with experiences that would pave the way for them to become open to actively engage with other professional opportunities.

Another theme that emerged in the data analysis was coded as ‘opening new perspectives’, listed as the second sub-theme in Fig. 4.4. For the participants, the new perspectives were related to projects that they could develop in their future careers, other paths than those exclusively centred on playing in an orchestra or on teaching. The following two quotations refer to this sub-theme. The first concerns the opportunity to think differently about the scores and the concert itself, while the second is about the process of developing a project:

P4: Everything we did in the workshops really helped to create new ideas for the projects and to give me a new way of thinking about scores and our concerts that I hadn’t had before.

P2: I really enjoyed the week. It was something I’ve never done before. Throughout the week, I had a lot of ideas about my project, and I don’t think I could have done it on my own.

One of the main aims of the REACT training school was to encourage students to explore their own expectations and challenges through project-based learning, rather than proposing ready-made models of good practice. This was mainly achieved in the mentoring sessions, the focus of which was to help students integrate the topics discussed at the training school with their individual contexts.

The last sub-theme coded in Benefits was ‘raising awareness of critical and creative thinking’. It describes student feedback on the role of critically exploring the decision-making process that is integral to project development.

P5: The school gave us the freedom and ‘wings’ to consciously think in terms of research about what we really wanted to do and not explore aimlessly. We had this idea at the beginning that we were going to experiment without control, but I ended up realising that, more than control, experimentation within the framework of research leads to conscious freedom within the scope of our creative project. I was able to realise this better by attending the workshops…

The training school revealed that any meaningful change in the teaching and learning traditional model through artistic research requires much more than teaching artistic research methods to undergraduate students. If students are surrounded by a teaching culture where research is not a core value, it will be hard for them to understand this paradigm shift. This was highlighted in the above quotation, when the student explained that the school taught them to ‘think in terms of research’. All of the students taking part in the training school had previous experience of learning research methods, but P5 suggests that the link between these research methods and their practice was not obvious.

Positive Aspects

The participants identified five positive aspects in the training school, coded as: closeness and partnership between students, closeness and partnership between teachers and students, individual support, school organisation, and staff involved in the school. Each of these aspects were coded as sub-themes. The first one (closeness and partnership between students) concerns the relationships established between participants in the training school. P9 and P2 referred to such relationships as more meaningful than others established in their usual courses. They appreciated the friendly environment that encouraged interaction between students and between students and teachers.

P9: [There was] a deeper relationship with the participants in this training school than probably with many of the colleagues I’ve known in the music department since the beginning of the year

P2: We spend more time with these people [the REACT training school colleagues] than with other colleagues on our course [...] it’s social, and social is extremely important and this Training School is centred on that too

Since the training school was developed on the basis of values such as collaboration and sharing, these quotes lead us to reflect further on why such a connection between the participants was so evident. These students were all enrolled at the same institution, but it seems that the training opened up an opportunity for them to discuss their challenges and expectations in a non-judgemental environment, where all participants had the chance to discuss and contribute individually to each other’s projects.

The second sub-theme listed as a positive aspect was ‘closeness and partnership between students and teachers’. P2 observed that the training school allowed students to share more about their feelings and ideas:

P2: I think it was very good that there was no distance between teachers and students, I’m talking about the coffee break, I think this connection helped a lot and it’s a form of sharing, because music is also what we do, we share a taste that we all have, however different it may be, it’s always a way of getting together, of creating new connections, of creating small roots within the same area, so to speak.

This quotation refers to the general perceptions of the students: the training school followed a dialogical and horizontal approach that facilitated the relationship between students and teachers, despite age or cultural differences in the group. The students felt an openness from the teachers, which encouraged them to share their thoughts and ideas. This was particularly important in one-to-one interactions, such as in the mentoring sessions.

One of the main aspects highlighted by the students was the ‘individual support’ given to them during the mentoring sessions—the third sub-theme coded within the positive aspects. The tutorial sessions opened a space for students to share their personal ideas on a more personal level and receive feedback from teachers.

P1: I think that, in my case, what was perhaps most important were the mentoring sessions. We talked about everything [...] but the mentoring was a bit more individual and specific to each case. In my case it helped more than probably for others, because on the last day we had mentoring with the teacher who gave the lecture on performance anxiety, and I think the lecture was super interesting, she was able to help me more directly. At least for me, for my problems, that moment gave me more space to talk about more private things. I think those sessions were the most important parts for me…

This observation suggests that a culture of mentoring should be fostered in HME. Although these students have individual lessons on a regular basis, the comment also suggests that creating opportunities to discuss wider topics with other experts could be very useful. P1’s quotation also leads us to recognise that topics such as artistic enquiry and performance anxiety are closely linked and that this relationship could be explored further in future interventions.

Another two sub-themes coded as positive aspects were the ‘school organisation’ and the ‘staff involved’. Participants found the programme to be balanced, with very good connections between lectures. P4 and P5 highlighted the fact that the programme was well balanced and that there was non-hierarchical relationship between student and staff.

P4: I think the organisation of the school was quite good. It wasn’t overwhelming, it wasn’t too heavy. It was intense, but it was of an appropriate intensity. It wasn’t too heavy for what I was expecting. Because when I saw the weekly timetable, I was frightened by how many different things we were going to have, but I think there was a good connection between them, and that got people motivated and wanting to know more.

P5: I totally agree that the organisation was exemplary, these things are usually chaotic, with many teachers who never keep to the timetable and we’re also Portuguese and consequently arrive late... this issue of there not being so much hierarchy between teachers and students is also something I’ve always valued a lot, I didn’t know almost anyone in the group that took part, but out of the blue it seemed like everyone was my friend!

These last two comments constitute significant feedback for the organisation of the training school. Seemingly, these students were expecting topics to be presented in a one-directional, expository manner. Adopting project-based learning combined with a student-centred approach allowed the REACT staff to cover a wide variety of topics in an interactive and therefore light-hearted way.

Improvements

The participants in the focus group talked about a number of possible improvements for future interventions as well as for the proposed shift to the new paradigm, which were very relevant for this initiative. These improvements were coded as the following sub-themes: ‘articulating the school’s programme with other academic activities’, ‘integrating more teachers and students’, ‘helping students to write projects’, ‘increasing the opportunities for hands-on activities’, ‘increasing the duration of the school’, and ‘varying the groups’ formation in mentoring sessions’. The first sub-theme, ‘articulating the school’s programme with other academic activities’, concerns the importance of integrating the school activities with the existing curriculum. For example, some students were not allowed to participate all week because some teachers did not excuse them from their other regular activities, as indicated by P6.

P6: But even so, for the experience I had, which was very limited, I think it was very enriching and I’m very sorry I couldn’t stay the whole week and that’s also something I can add to the things that could be better. We had a whole week to try and sort out our creativity (so to speak), but, for example, I had to leave in the middle of this very special and unusual project to take part in an orchestra activity that I’ve been doing since the beginning of my degree [...] just because no one was released from the orchestra.

This problem arose due to the difficulty of articulating intensive extracurricular courses with the institution’s regular activities without overriding them. However, many students felt that their instrumental teacher should have been involved. This suggestion of improvement was coded as ‘integrating other teachers and students’. The next two quotation exemplify the importance of involving teachers:

P2: I think it’s important that teachers have this way of understanding our idea and what we’ve done this week, because it can affect assessment; we can become demotivated when we’re assessed. You can spend a whole week acquiring new knowledge that you then fail to apply. If the teachers are in tune with our ideas, or at least if they understand what this ‘training school’ stands for, then perhaps this is a way for us to make a significant change through the REACT project, rather than confronting two opposing forces.

P3: To open up this thinking to the whole community, especially the instrument teachers, because as they said, the curriculum is very interesting, but the way it’s put into practice sometimes doesn’t match the objective. Often, teachers do with the modules what they want and not what is proposed by the module itself, and that makes everything very difficult [...] I’m talking specifically about the orchestra. For example, I could have been exempted from doing [it for] the rest of the project, but that didn’t happen. But there are a lot of problems, you have to deconstruct a lot of problems to be able to implement this kind of thing, but I think we’ve had some very interesting days.

Continuing in this line of thought, P3 highlighted the importance of involving more students in the training school. This participant emphasised the importance of informing others about the initiative:

P3: I wanted to address this point because I think it’s really important that all students know that this school exists and that all teachers should be the main disseminators of this information among their students.

These previous three comments suggest that students are aware that the impact of this training school could be amplified if the instrument teachers were in tune with the main ideas of the training school. This corroborates the idea that the development of new pedagogical approaches to performance must integrate all parties involved.

In addition, some students felt that the training school would benefit from giving students opportunities to plan and organise a concrete project, ‘helping students to write their own projects’, the fourth sub-theme coded as improvement.

P7: Before the week started I had the idea that we were going to... like... with the mentoring sessions, draw up our projects and put them on paper, you know. And I missed that a bit, because sometimes it’s important [...] sometimes it’s important to learn how to structure a project, even to prepare it for a public call.

This feedback led us to reflect on the importance of the space opened up by the programme to understand the particularities of each individual case. Although mentoring sessions should naturally cover this aspect, there was still room to delve deeper into each student’s particular project.

In terms of the structure of the school, it was suggested that ‘increasing the opportunities for hands-on activities’, the fifth sub-theme coded as improvement. should be considered:

P9: Have a practical component, even if it’s on the day itself. Along with a kind of theoretical lecture, there should also be space in the mentoring session to help students with the practical aspects of realising the project.

In fact, several comments in the interviews emphasised the importance of practical activities for the school (especially those dedicated to developing the project), although the students recognised a good balance between the activities on offer. Some participants suggested that ‘increasing the duration of the school’ would improve it. This was specially highlighted by P1 and P2. In the second quotation, below, increasing the practical component is linked to the wish for increased opportunities for hands-on activities.

P1: I would say that there are things that could have more time to discuss. There were moments when we organised ourselves in groups and we had to prepare presentations… but it would be much more effective and interesting if we had had more time. […] Especially at the beginning of the week we had several practical things and I think this should be the path to continue; it is the one that is the most stimulating and that ends up making the biggest difference [...] I would say that some lectures are immensely theoretical and are interesting too… but, whatever is more practical I like it better. In short, I suggest extending the time with these teachers through more mentoring sessions and workshop sessions.

P2: So, I think the school week is very well structured, I also think that the issue of specifying some subjects, or some workshops, or even broadening the mentoring sessions would be something that could benefit everyone […] time could be more extended, it doesn’t need to be a week, but also to give time so that we could focus at the theoretical level and have a practical component […] and even make room for more mentoring sessions so that students have specific help more suited to their specific project.

Increasing the duration of the school, as suggested by these participants, is a challenge for the REACT consortium. In fact, organising interventions like this requires a deep negotiation that involves several parties in each of the five participating institutions.

During the school, the mentoring sessions always comprised the same group of students; only the facilitators changed. P7 and P4 suggested that the groups could also be varied, integrating the students even more, in terms of including the student voice in co-creating sessions. This concerns the seventh code within the improvement category: ‘varying the groups’ formation in mentoring sessions’:

P7: Really, a week is a short time, it would have to be a longer period, but I also think it’s very nice the idea that after each group debate in the mentoring sessions, if we could get to know the ideas of the other groups, of the other projects, because that can help, one can get other ideas and suggestions too.

These suggestions for improvement are important for the planning of future interventions. They highlight the importance of balancing different types of activities and negotiating the pedagogical proposal with the idiosyncrasies of each institution. Although REACT teachers made themselves available to continue supporting the development of projects after the training school finished, the demobilisation caused by the end of face-to-face activities ended up resulting in, if not abandonment, a considerable slowdown in the implementation of individual projects. Only a few students got back in touch with the participating teachers to get further help.

Future Implications

The last theme described in this chapter encompasses two sub-themes, namely: ‘giving an answer to specific audiences’ and ‘serving as a basis for new courses’. According to the students, future implementations of this training school could ‘give answers to specific audiences’—the first sub-theme coded as future implications—who are interested in developing more performance and artistic skills to improve in their profession.

P4: It is always personal, so I think, in the long run, it would help specific students who really want to integrate this new field of vision and lead to a new way of thinking as artists. Not everybody wants to be. There are a lot of people who want to be researchers, want to be artists, there are a lot of different specificities but I think this approach is something that is missing at the moment.

Finally, the students felt that this training school could have a huge impact on curriculum reconfiguration and could ‘serve as a basis for new courses’.

P4: we would really need to experience the REACT school as a master degree or at least as a branch of a course… This would be an effective way to offer this new perspective and knowledge.

P4 also suggested that the structure of the training school could be included as a module in the current plan of the master’s degree.

P4: I think it would be a good idea, not to change the system completely, not to do it in a brutal way, but to implement it little by little. For example, we have many subjects that are not taught at the moment, in the master’s degree and bachelor’s degree, but they do exist in the curricular plan. I think that, with the REACT training school, we should be able to replace those subjects that are frozen. And it would already be a path of slowly implementing a new way of restructuring the curriculum, and it would already help students in the future, close to those who are finishing the conservatory, to be able to have new subjects that can be very important for the curriculum and for the way of preparing themselves for the labour market.

The comments here suggest that the participating students recognised the potential of an artistic research-based learning for their artistic development and did clearly understand why it should be further explored. Despite feeding back on the potential for improvement, participants recognized that an intervention like the REACT training school should be integrated in the curriculum, not an isolated activity.

Discussion

This book chapter has reported on the second REACT training school, which was a pedagogical intervention testing an artistic research-based approach to teaching and learning music performance, offered as an extracurricular course. The rationale for this implementation is based on the limitations and shortcomings of the ‘conservatoire model’, which has restricted students’ possibilities for developing critical and creative thinking in HEIs. Inspired by the practices and methods of artistic research, the second REACT training school was an initiative designed to foster creativity and critical thinking51,52 via a student-centred curriculum and project-based learning.53 This approach addresses aspects that were mentioned as key issues by the literature referred to in section two. The purpose of the school was to provoke change in the students’ perspective and attitude towards making music, by providing perspectives drawn from artistic research practice.

Overall, participants reported benefits related to the school and to their perspectives that seem to match the artistic career demands in music industries. These benefits included balancing tradition and creativity,54 opening up new perspectives,55 and raising awareness of critical56 and creative thinking. 57 The outcomes of the study reported in this chapter reinforce the need to open space for new pedagogical and artistic perspectives that stimulate critical thinking in HME. Overall, the students reported a significant change in their attitude towards music practice and goals. They reported a shift in their creative focus from one of skill competency toward a personal reflective practice focused on project-based learning within their art world. We argue that this shift constitutes an important first step in students’ development of their future professional career.

The second REACT training school was designed for the purpose of testing novel approaches in the teaching and learning of music performance. Here, we do not proposed a concrete solution but, instead, present a range of possibilities. Although this intervention offered a clear hint that the proposed approach could lead to a very promising change in mindsets, there is still a need to clarify how artistic research can interact with the conservatoire model, as well as how instrumental teachers, who are not familiar with artistic research, might come to participate. Further, the qualitative study which forms the basis of the chapter had its own limitations: the limited number of interviewees (just 8 from a total of 17 participants); the short duration of the intervention, which did not allow tutorial support until the public presentation of the developed projects; the data analysis was based on students’ reports of their experiences and did not include other sources such as the data related to their final projects’ presentations. Nevertheless, the findings marginally suggest several benefits and positive aspects of integrating artistic research practice in the pedagogical structure of HEIs, as further supported by findings presented in other chapters of this book. Students seemed very aware of the importance of their learning development and pointed to the importance of new teaching approaches in HME.

The results here suggest that students highly valued the closeness and the open environment promoted by the training school, in terms of their interactions with staff. Future studies could explore the ways in which institutions encourage students in the deeper investigation of their feelings, activities, questions, and personal challenges. In this way, they would engage students in experiential terms in all the dimensions of the REACT model. The training school was limited, as noted, but it gave us insight into the potential of approaches to teaching and learning performance through artistic research. And, through the qualitative study, we have been encouraged to think of this as an opportunity to increase student autonomy and personal engagement in the design of their studies.

References

Barrett, Estelle, Aesthetic Experience and Innovation in Practice–Led Research (2010), conference paper, Deakin Research Online, https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30032166

Bartleet, Brydie-Leigh, Dawn Bennett , Ruth Bridgstock, Paul Draper, Scott Harrison, and Huib Schippers, ‘Preparing for Portfolio Careers in Australian Music: Setting a research agenda’ Australian Society for Music Education Corporation, 1 (2012), 32–41, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1000243.pdf

Beeching, Angela, ‘Musicians Made in USA: Training Opportunities and Industry Change’, in Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, ed. by Dawn Bennett (Champaign, IL: Common Ground, 2012), pp. 27–43

Bennett, Dawn and Ruth Bridgstock, ‘The Urgent Need for Career Preview: Student Expectations and Graduate Realities in Music and Dance’, International Journal of Music Education, 33 (2015) 3, 263–77, https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761414558653

Bennet, Dawn, Angela Beeching, Rosie Perkins, Glen Carruthers, and Janis Weler, ‘Music, Musicians and Careers’, in Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, ed. by Dawn Bennett (Champaign, IL: Common Ground, 2012), pp 9-10.

Berger, Martin ‘Educing Leadership and Evoking Sound: Choral Conductors as Agents of Change’, in Leadership and Musician Development in Higher Music Education, ed. by Dawn Bennett, Jennifer Rowley, and Patrick Schmidt (Routledge: New York, 2019), pp. 115–29 (pp. 115–20)

Bulley, James and Özden Şahin, Practice Research - Report 1: What is practice research? and Report 2: How can practice research be shared? (London: PRAG-UK, 2021), p. 80, https://doi.org/10.23636/1347

Burnard, Pamela, Developing Creativities in Higher Music Education: International Perspectives and Practices (Routledge: London, 2013), p. 100

Carey, Gemma and Don Lebler, ‘Reforming a Bachelor of Music Programme: A Case Study’, International Journal of Music Education, 30 (2012) 4, 312–27

Cooper, Paul and Donald McIntyre, Effective Teaching and Learning: Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives (Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education, 1998)

Correia, Jorge and Gilvano Dalagna, ‘A Verdade Inconveniente sobre os Estudos em Performance’, in Performance Musical sob uma Perspectiva Pluralista, ed. by Sonia R. Albano de Lima (São Paulo: Musa Editora, 2021), pp. 11–26

Correia, Jorge and Gilvano Dalagna, Cahiers of Artistic Research 3: An explanatory model for Artistic Research (Aveiro: Editora da Universidade de Aveiro, 2018)

Correia, Jorge, Gilvano Dalagna, Alfonso Benetti, and Francisco Monteiro, Cahiers of Artistic Research 1: When Is Research Artistic Research? (Aveiro: Editora da Universidade de Aveiro, 2018)

Correia, Jorge and others, REACT–Rethinking Music Performance in European Higher Education Institutions, Artistic Career in Music: Stakeholders Requirement Report (Aviero: UA Editora, 2021), https://doi.org/10.48528/wfq9-4560

Crispin, Darla, ‘Artistic Research and Music Scholarship: Musings and Models from a Continental European Perspective’, in Artistic Practice as Research in Music: Theory, Criticism, Practice, ed. by Mine Doğantan-Dack (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2015), pp. 53–72

Dalagna, Gilvano, Sara Carvalho, and Graham Welch, Desired Artistic Outcomes in Music Performance (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021)

De Assis, Paulo, Logic of Experimentation: Rethinking Music Performance through Artistic Research (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2018)

Deliège, Irene, and Geraint Wiggins, Musical Creativity: Multidisciplinary Research in Theory and Practice (Psychology Press: East Sussex, 2006)

Durrant, Colin, ‘Shaping Identity Through Choral Activity: Singers’ and Conductors’ Perceptions’, Research Studies in Music Education 24 (2005) 1, 88–98, https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X050240010701

Dylan Smith, Gareth, ‘Masculine Domination in Private Sector Popular Music Performance Education in England’, in Bourdieu and the Sociology of Music Education, ed. by Pamela Burnard, Ylva Trulsson Hofvander, and Johan Söderman (Ashgate: Surrey, 2015), pp. 61–78

Ford, Biranda and John Sloboda, ‘Learning from Artistic and Pedagogical Differences Between Musicians’ and Actors’ Traditions Through Collaborative Processes’, in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, ed. by Helena Gaunt and Heidi Westerlund (Surrey: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 27–36

Gill, Rosalind, ‘Cool, Creative and Egalitarian? Exploring Gender in Project-Based New Media Work in Europe’, Information, Communication and Society, 5 (2002), 70–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180110117668

Gaunt, Helena, Andrea Creech, Marion Long, and Susan Hallam, ‘Supporting Conservatoire Students Towards Professional Integration: One-to-One Tuition and the Potential of Mentoring’, Music Education Research, 14 (2012) 1, 25–43

Haseman, Brad, ‘A Manifesto for Performative Research’, Media International Australia, 118 (2006) 1, 98–106

Jørgensen, Harold, ‘Western Classical Music Studies in Universities and Conservatoires’, in Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning, ed. by Ioulia Papageorgi and Graham Welch (Ashgate: Surrey, 2014), pp. 3–20

Jørgensen, Harold Research into Higher Music Education (Oslo: Novos Press, 2009)

Lennon, Mary and Geoffrey Reed, ‘Instrumental and Vocal Teacher Education: Competences, Roles and Curricula’, Music Education Research, 14 (2012) 3, 285–308

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe and Dawn Bennett, ‘A Lifespan Perspective on Multi-Professional Musicians: Does Music Education Prepare Classical Musicians for their Careers?’, Music Education Research, 22 (2020) 1, 1–14, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/14613808.2019.1703925

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe and Dawn Bennett, ‘Broadening Student Musicians’ Career Horizons: The Importance of Being and Becoming a Learner in Higher Education’, International Journal of Music Education, 39 (2021) 2, 134–50, https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761421989111

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe and Pamela Burnard, ‘Towards a Nuanced Understanding of Musicians’ Professional Learning Pathways: What Does Critical Reflection Contribute?’, Research Studies in Music Education, 0 (2021) 0, 1–31, https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X211025850

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe and Dawn Bennett, ‘A Lifespan Perspective on Multi-Professional Musicians: Does Music Education Prepare Classical Musicians for their Careers?’, Music Education Research, 22 (2020) 1, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1703925

Östersjö, Stefan, ‘Art Worlds, Voice and Knowledge: Thoughts on Quality Assessment of Artistic Research Outcomes’, ÍMPAR Online journal for artistic research, 3(2) (2019), 60–69

Östersjö, Stefan, ‘Thinking-Through-Music: On Knowledge Production, Materiality, and Embodiment in Artistic Research’, in Artistic Research in Music: Discipline and Resistance, ed. by Jonathan Impett (Leuven: Leuven University, Press, 2018), pp. 88–107

Papageorgi, Ioulia and Graham Welch, (eds), Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning (Surrey: Ashgate, 2014)

Papageorgi, Ioulia, Andrea Creech, Elizabeth Haddon, Frances Morton, Christophe De Bezenac, Evangelos Himonides, John Potter, Celia Duffy, Tony Whyton, and Graham Welch, ‘Perceptions and Predictions of Expertise in Advanced Musical Learners’, Psychology of Music, 38 (2010a) 1, 31–66

Papageorgi, Ioulia, Andrea Creech, Elizabeth Haddon, Frances Morton, Christophe De Bezenac, Evangelos Himonides, John Potter, Celia Duffy, Tony Whyton, and Graham Welch, ‘Institutional Culture and Learning I: Perceptions of the Learning Environment and Musicians’ Attitudes to Learning’. Music Education Research, 12 (2010b) 2, 151–178.

Persson, Roland S., ‘The Subjective World of the Performer’, in Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory Research and Applications, ed. by Patrick N. Juslin and John Sloboda (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 275–89

Perkins, Rosie, ‘Learning Cultures and the Conservatoire: An Ethnographically-informed Case Study’, Music Education Research, 15 (2013) 2, 196–213

Robson, Colin, Real World Research (West Sussex: Wiley, 2011)

Seth, Sanjay, Beyond the Reason: Postcolonial Theory and the Social Sciences (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021)

Silverman, Marissa ‘A Performer’s Creative Processes: Implications for Teaching and Learning Musical Interpretation’, Music Education Research, 10 (2008) 2, 249–69

Smilde, Rineke and Sigurdur Halldórsson, ‘New Audiences and Innovative Practice: An International Master’s Programme with Critical Reflection and Mentoring at the Heart of an Artistic Laboratory’, in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, ed. by Helena Gaunt and Heidi Westerlund (Surrey: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 225–30

Sloboda, John, Musicians and Their Live Audiences: Dilemmas and Opportunities. Understanding Audiences, ([n. p.]: Scribd, 2013), https://pt.scribd.com/document/538118141/Sloboda-John-Musicians-and-their-live-audiences-dilemmas-and-opportunities

Stepniak, Michael and Peter Sirotin, Beyond the Conservatoire Model: Reimagining Classical Music Performance Training in Higher Education (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 72

Thompson, Katja ‘Fostering Transformative Professionalism Through Curriculum Changes Within a Bachelor of Music’, in Expanding Professionalism in Music and Higher Music Education: A Changing Game, ed. by Heidi Westerlund and Helena Gaunt (Routledge: London, 2021), pp. 42–58

1 Jorge Correia and others, REACT–Rethinking Music Performance in European Higher Education Institutions, Artistic Career in Music: Stakeholders Requirement Report (Aveiro: UA Editora, 2021), p. 20, https://doi.org/10.48528/wfq9-4560

2 Harold Jørgensen, ‘Western Classical Music Studies in Universities and Conservatoires’, in Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning, ed. by Ioulia Papageorgi and Graham Welch (Ashgate: Surrey, 2014), pp. 3–20 (p. 15).

3 Ioulia Papageorgi; Andrea Creech; Elizabeth Haddon; Frances Morton; Christophe De Bezenac; Evangelos Himonides; John Potter; Celia Duffy; Tony Whyton, and Graham Welch, ‘Perceptions and Predictions of Expertise in Advanced Musical Learners’, Psychology of Music, 38 (2010) 1, 31–66, https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735609336044

4 Gemma Carey and Don Lebler, ‘Reforming a Bachelor of Music Programme: A Case Study’, International Journal of Music Education, 30 (2012), 4, 312–27.

5 Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning, ed. by Ioulia Papageorgi and Graham Welch (Surrey: Ashgate, 2014), p. 15.

6 Michael Stepniak and Peter Sirotin, Beyond the Conservatoire Model: Reimagining Classical Music Performance Training in Higher Education (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 72.

7 Ioulia Papageorgi, Andrea Creech, Elizabeth Haddon, Frances Morton, Christophe De Bezenac, Evangelos Himonides, John Potter, Celia Duffy, Tony Whyton, and Graham Welch, ‘Institutional Culture and Learning I: Perceptions of the Learning Environment and Musicians’ Attitudes to Learning’, Music Education Research, 12 (2010) 2, 151–78.

8 See Gilvano Dalagna, Sara Carvalho, and Graham Welch, Desired Artistic Outcomes in Music Performance (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), p. 108; John Sloboda, Musicians and Their Live Audiences: Dilemmas and Opportunities. Understanding Audiences ([n. p.]: Scribd, 2013), https://pt.scribd.com/document/538118141/Sloboda-John-Musicians-and-their-live-audiences-dilemmas-and-opportunities

9 Biranda Ford and John Sloboda, ‘Learning from Artistic and Pedagogical Differences Between Musicians’ and Actors’ Traditions Through Collaborative Processes, in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, ed. by Helena Gaunt and Heidi Westerlund (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 27–36. See also Sloboda.

10 Roland S. Persson, ‘The Subjective World of the Performer’, in Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory Research and Applications, ed. by Patrick N. Juslin and John Sloboda (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 275–89.

11 Dalagna, Carvalho, and Welch, p. 150.

12 Helena Gaunt, Andrea Creech, Marion Long, and Susan Hallam, ‘Supporting Conservatoire Students Towards Professional Integration: One-to-One tuition and the Potential of Mentoring’, Music Education Research, 14 (2012) 1, 25–43.

13 Angela Beeching, ‘Musicians Made in USA: Training Opportunities and Industry Change’, in Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, ed. by Dawn Bennett (Champaign, IL: Common Ground, 2012), pp. 27–43.

14 Rineke Smilde and Sigurdur Halldórsson, ‘New Audiences and Innovative Practice: An International Master’s Programme with Critical Reflection and Mentoring at the Heart of an Artistic Laboratory’, in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, ed. by Helena Gaunt and Heidi Westerlund (Surrey: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 225–30 (p. 220).

15 Dawn Bennet, Angela Beeching, Rosie Perkins, Glen Carruthers and Janis Weler, ‘Music, Musicians and Careers’, in Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, ed. by Dawn Bennett (Champaign, IL: Common Ground, 2012), pp. 9-10.

16 Correia and others, p. 20.

17 Rosalind Gill, ‘Cool, Creative and Egalitarian? Exploring Gender in Project-Based New Media Work in Europe’, Information, Communication and Society, 5 (2002), 70–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180110117668

18 Guadalupe López-Íñiguez and Dawn Bennett, ‘A Lifespan Perspective on Multi-Professional Musicians: Does Music Education Prepare Classical Musicians for their Careers?’, Music Education Research, 22 (2020) 1, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1703925

19 Dawn Bennett and Ruth Bridgstock, ‘The Urgent Need for Career Preview: Student Expectations and Graduate Realities in Music and Dance’, International Journal of Music Education, 33 (2015) 3, 263–77, https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761414558653

20 Colin Durrant, ‘Shaping Identity Through Choral Activity: Singers’ and Conductors’ Perceptions’, Research Studies in Music Education, 24 (2005) 1, 88–98, https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X050240010701

21 Katja Thompson, ‘Fostering Transformative Professionalism Through Curriculum Changes within a Bachelor of Music’, in Expanding Professionalism in Music and Higher Music Education: A Changing Game, ed. by Heidi. Westerlund and Helena Gaunt (Routledge: London, 2021), pp. 42–58 (pp. 44–50).

22 Martin Berger, ‘Educing Leadership and Evoking Sound: Choral Conductors as Agents of Change’, in Leadership and Musician Development in Higher Music Education, ed. by Dawn Bennett, Jennifer Rowley, and Patrick Schmidt (Routledge: New York, 2019), pp. 115–29 (pp. 115–20).

23 Gareth Dylan Smith, ‘Masculine Domination in Private Sector Popular Music Performance Education in England’ in Bourdieu and the Sociology of Music Education, ed. by Pamela Burnard, Ylva Hofvander Trulsson, and Johan Söderman (Ashgate: Surrey, 2015), pp. 61–78.

24 Pamela Burnard, Developing Creativities in Higher Music Education: International Perspectives and Practices (Routledge: London, 2013). P.100.

25 Irene Deliège and Geraint Wiggins, Musical Creativity: Multidisciplinary Research in Theory and Practice (Psychology Press: East Sussex, 2006), p. 1.

26 Brydie-Leigh Bartleet, Dawn Bennett, Ruth Bridgstock, Paul Draper, Scott Harrison, and Huib Schippers, ‘Preparing for Portfolio Careers in Australian Music: Setting a Research Agenda’, Australian Society for Music Education Corporation, 1 (2012), 32–41, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1000243.pdf

27 Burnard, p. 100.

28 Mary Lennon and Geoffrey Reed, ‘Instrumental and Vocal Teacher Education: Competences, Roles and Curricula’, Music Education Research, 14 (2012) 3, 285–308.

29 Correia and others, p. 20.

30 The Bologna Declaration refers to an agreement between 29 European countries to establish a European Higher Education area which supported the free movement of students, the acceptance of equivalent entry qualifications, and a standard approach to undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. See https://ehea.info/Upload/document/ministerial_declarations/1999_Bologna_Declaration_English_553028.pdf

31 Darla Crispin, ‘Artistic Research and Music Scholarship: Musings and Models from a Continental European Perspective’, in Artistic Practice as Research in Music: Theory, Criticism, Practice, ed. by Mine Doğantan-Dack (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2015), pp. 53–72 (p. 68).

32 Crispin, p. 55.

33 Ford and Sloboda, p. 30.

34 Jorge Salgado Correia, Gilvano Dalagna, Alfonso Benetti, and Francisco Monteiro, Cahiers of Artistic Research 1: When Is Research Artistic Research? (Aveiro: Editora da Universidade de Aveiro, 2018), p. 40.

35 Dalagna, Carvalho, and Welch, p. 108.

36 Crispin, p. 55.

37 Jorge Salgado Correia and Gilvano Dalagna, Cahiers of Artistic Research 3: A explanatory model for Artistic Research (Aveiro: Editora da Universidade de Aveiro, 2018), p. 40.

38 Stefan Östersjö, ‘Thinking-Through-Music: On Knowledge Production, Materiality, and Embodiment in Artistic Research’, in Artistic Research in Music: Discipline and Resistance, ed. by Jonathan Impett (Leuven: Leuven University, Press, 2018), pp. 88–107 (p. 100).

39 Jorge Salgado Correia and Gilvano Dalagna, ‘A Verdade Inconveniente sobre os Estudos em Performance’, in Performance Musical sob uma Perspectiva Pluralista, ed. by Sonia R. Albano de Lima (Musa Editora: São Paulo, 2021), pp. 11–26 (p. 20).

40 Estelle Barrett, Aesthetic Experience and Innovation in Practice–Led Research (2010), conference paper, Deakin Research Online, https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30032166

41 Brad Haseman, ‘A Manifesto for Performative Research’, Media International Australia, 118 (2006) 1, 98–106.

42 Sanjay Seth, Beyond the Reason: Postcolonial Theory and the Social Sciences (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), p. 200.

43 James Bulley and Özden Şahin, Practice Research - Report 1: What is practice research? and Report 2: How can practice research be shared? (London: PRAG-UK, 2021), p. 80, https://doi.org/10.23636/1347

44 Stefan Östersjö, ‘Art Worlds, Voice and Knowledge: Thoughts on Quality Assessment of Artistic Research Outcomes’, ÍMPAR Online journal for artistic research, 3(2) (2019), 60–69.

45 Dalagna, Carvalho, and Welch, p. 180.

46 Jorge Correia and others, p. 20.

47 The REACT project received approval for conducting this study by the Ethics and Deontology Committee of University of Aveiro (Approval no. 18-CED/2021) and by the Data Protection Officer of University of Aveiro. In addition, all participants signed an informed-consent document agreeing to participation, and they were assured that all data collected were confidential and anonymous. For the purpose of this chapter, participants are referred to as P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, and P8.

48 Colin Robson, Real World Research (West Sussex: Wiley, 2011), p. 400.

49 Paul Cooper and Donald McIntyre, Effective Teaching and Learning: Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives (Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education, 1998), p. 35.

50 Only selected parts of the interviews that exemplify each theme were translated into English when writing up the results.

51 Burnard, p. 120.

52 Lennon and Reed, p. 258.

53 Correia and others, p. 80.

54 Dalagna, Carvalho, and Welch, p. 180.

55 López-Íñiguez and Bennett, p. 134.

56 Correia and others, p. 20.

57 Thompson, p. 44.