Introduction

© 2024 Helen Julia Minors et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0398.00

This book is the first publication to address the potential of artistic research in music to innovate the teaching and learning of music performance in Higher Music Education (HME) in Europe. Across the past twenty years, method development in artistic research has introduced experimental approaches1,2,3 and artistic application of reflexive methods4,5 in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). While artistic research entered academia as something of a Trojan horse (as described by Marcel Cobussen in 2007),6 our book traces how the practices of artistic research, and their practitioners, have become increasingly integrated in HME. At the same time, we also identify how important aspects of the potential of artistic research to provide critical and novel perspectives to HME are immediately related to how artistic researchers are also situated in Art worlds and its music industries.

As a response to the Bologna process (since 1999), HME has been in a state of transformation, which has often been referred to as an academization of formerly more practice-based teaching institutions. This publication seeks to bring out a different trajectory, through which processes of renewal in HME has led to developing student-centred approaches, employability skills, and greater student autonomy, with the further argument that artistic research practices have provided novel opportunities in this development. This has entailed a development of teaching models that would promote student self-determination, capacity to autonomously identify needs for further knowledge, and competencies, and also an emphasis on lifelong learning.

Some of the challenges that HME has been seeking to address are related to the questioning of the traditional conservatoire model. Practices associated with the teaching and learning of music performance have focused on values and expectations established in the nineteenth-century Western conservatory context and its master-apprentice practice.7 This resulted in a predominantly mono-directional teaching and learning environment, emphasising the development of technical skills rather than critical and creative abilities.8 Furthermore, such practices do not sufficiently prepare the student to meet the current professional demands and to envision alternatives beyond traditional institutional contexts for musical performance.9 Current professional demands require the development of new, innovative pedagogical models as integrated alternatives to existing traditional practices.10,11

REACT – Rethinking Music Performance in European Higher Education Institutions is a Strategic Partnership funded by ERASMUS+ that seeks a response to these problems and to communicate best practices in this domain, with the aim of furthering a new teaching and learning paradigm in HME. REACT is developed by an international consortium12 that mobilises an international cooperative network to develop new approaches to the teaching and learning of music performance in Higher Music Education. This strategic partnership collaboratively explores the potential of artistic research to propose new approaches to lifelong learning and student-centred pedagogical approaches.

Hence, the core pedagogical idea is that teachers share their experience of artistic research practices with their students. This entails an approach built on reflective practice and critical thinking. Rather than top-down transmission of knowledge, the aim is to create teaching and learning contexts that enable student and teacher to contextualise, explore, and share artistic research practices in music performance, from within the framework of Higher Music Education. At the same time, this also entails situating the study of music performance in a wider context, in immediate interaction with the music art worlds and their music industries. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, by inviting students to an approach to learning music performance through artistic research, we put the individual capacities, interests, and inner motivation of the student at the centre.

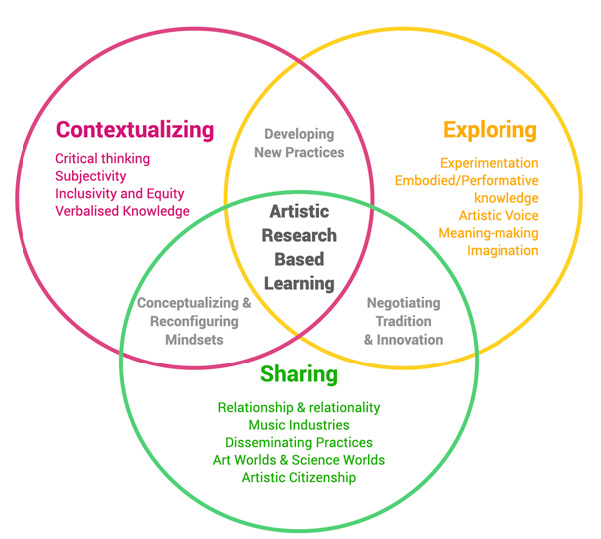

In Figure I.1, the core perspectives of contextualising, exploring, and sharing are organised in three spheres, with the notion of artistic research based-learning at the centre, as a representation of how the student’s individual wishes, intentions, possibilities, and challenges must be at the heart of the matter.

The left sphere embraces different perspectives of how a student may further contextualise their practice. Artistic research has brought to light the multiplicity of the knowledge production in musical practice. To fully embrace the embodied, artistic, and discursive knowledge forms also entails identifying possibilities for artistic development. At the same time, it also brings light to how some knowledge forms are deeply situated in practices developed in the art worlds of music and others situated in the science worlds of music research. For the purposes of this book, and considering the forms of knowledge activated in artistic research, it is essential to see this distinction as a way for each individual to navigate their practices within these wider fields of knowledge production. It is not a matter of choosing alliances but, rather, constitutes a means to situate one’s practices and abilities in a wider context and identify the many different agencies with which a musician must interact in their studies as well as in their professional life. The ethos of critical thinking also demands that the process of contextualising practice involves the consideration of equitable and inclusive practices in order to inform and make meaningful change.

The right sphere includes explorative practices drawn from artistic research. We find essential how artistic research has come to be understood as built on the notion of experimentation in exploratory artistic lab settings. This may entail experimentation with artefacts like scores and instruments, and with musical traditions by challenging and blending performance practices. These explorations may also entail subjective perspectives such as finding a personal voice as well as the extension of such artistic experimentation in intersubjective negotiations of a shared, or discursive, voice through artistic collaboration.13

The bottom sphere reflects how the outcomes of artistic research may be effectively shared, both within academic contexts and in relation to art worlds as well as in wider societal perspectives. This may entail the development of further institutional collaboration beyond the academy, seeking to increase employability skills and societal relevance in our education.

Fig. I.1 A student-centred perspective on the teaching and learning of music performance grounded in artistic research practices.

Introducing approaches to knowledge through critical thinking and a wide range of embodied, artistic and discursive knowledge forms, this book is complemented by a series of videos, as part of a MOOC14 produced by teachers and researchers, which offer a first-person perspective of the artistic research in action, from teachers and researchers from within the consortium.

A student-centred approach was the basis for formulating the above figure. This was done in multiple ways: first REACT training schools engaged directly with students testing new ideas and involving both staff and students in partnership in the various experiences (articulated in Chapters 4 and 10). Moreover, the research presented within REACT and this book, all utilise student-centred approaches to considering the benefit and impact of the teaching and learning experience. In many of the examples, such as in Chapter 10, 11, and 12, students work as partners with colleagues to lead on making such artistic changes. The student voice is frequently cited throughout this book, enabling readers to engage directly with the feedback given in response to the creative interventions leading to the novel pedagogic ideas and findings shared here.

The present book is composed of chapters mainly drawn from peer reviewed contributions from the REACT symposium held at the Piteå School of Music, Luleå University of Technology in September 2022. The professional experience of the collected authors represents many decades of developing new approaches to their teaching through artistic research. The discrepancy in how artistic research has been implemented in varying degrees in different European countries is at this point becoming a concern in the development of the teaching of music performance in HME.15 It is a concern because there remains an over-reliance on traditional methods. The need for sharing practices across institutions is imperative to deepen understanding of the potential of artistic research in this context as well as sharing pedagogic tools and methods in advancing the centring of the student voice. Whilst the need for sharing these experiences and practices in teaching performance in HME is great, the differing institutional and structural conditions make such sharing less feasible. Hence in some countries, as exemplified in Chapter 1, artistic research has formed the basis for the development of the degree projects, and the structure of both first and second cycle education in music performance across the past decade and more, while in other countries, such as Germany, such processes are initiated at around the same time as the REACT project was created. In addition, the funding structures for HME vary greatly, which impacts not only the access to education, but the pedagogic models for delivering performance. For example, in the UK, there are fees paid via loan for every degree, currently £9,250 per year, which means there are limited resources for one-to-one tuition, and, as such, universities have fewer one-to- one performance-hour delivery per year than the specialist providers, including conservatoires, who gain more funding. By contrast, in many European countries, the education is fully funded by the state, which facilitates access and does not limit the resourcing of performance tuition.

While such differences have been observed also within the consortium of REACT, the project seeks to develop innovative means for sharing practices across institutions and, thereby, to develop impact which can substantially strengthen the development of more inclusive and dynamic teaching practices. The aim of the present book is to contribute to such a development by focussing more on the practices developed by an author, or a group of authors, rather than on theoretical perspectives. Further, all chapters address these practices in varying degrees from a student-centred perspective, sometimes by providing examples of a practical nature, or by reporting on research that draws on accounts and experiences of students, and by incorporating PhD artistic researchers in their own reflections on their own learning processes, as well as how such experience can be applied in teaching.

The book is structured in three parts: I) Artistic Research in HME; II) Novel Approaches to Teaching Interpretation and Performance; III) Challenges and Opportunities of Music Performance Education in Society. The four editors all have significant long-term experience of carrying out artistic research across European institutions, as well as of developing, leading, and managing music performance teaching in HEIs and have themselves developed novel teaching formats and curricula.

Part I, ‘Artistic Research in HME’, provides perspectives on how artistic research has developed in Higher Education Institutions in Europe since the beginning of the implementation of the Bologna process. Through a range of practice-based examples, drawing both on accounts from students and teachers, it is suggested that artistic research has increasingly contributed to reconfiguring music-performance teaching and learning also at undergraduate levels. From different perspectives, each chapter in this section provides examples of how artistic research practices have been central in the development of methods for teaching and learning of music performance across different European countries. A central factor appears to be a focus on artistic processes, and how these can be both scrutinised and deepened, through approaches to practice through research. Further, many examples point to how the artistic research practices of teachers may be shared with students, to the effect of enabling greater student autonomy and the development of lifelong learning.

Stefan Östersjö, Carl Holmgren, and Åsa Unander-Scharin’s chapter, ‘A Swedish Perspective on Artistic Research Practices in First and Second Cycle Education in Music’, explores student-centred formats for HME. Fausto Pizzol, in ‘Experimentation as a Learning Method: A Case Study exploring Affordances of a Musical Instrument’, and Mikael Bäckman, in ‘From Imitation to Creation’, both seek to explore how the processes of developing a creative voice and personal performance voice may be effectively shared with students in the HME setting, through exploratory and innovative curriculum design. Gilvano Dalagna, Clarissa Foletto, Jorge Salgado Correia, and Ioulia Papageorgi’s chapter, ‘Teaching Musical Performance from an Artistic Research-Based Approach: Reporting on a Pedagogical Intervention’, reports on a pedagogical intervention testing an artistic research-based approach to teaching and learning music performance, as a part of the REACT project.

Part II, ‘Novel Approaches to Teaching Interpretation and Performance’, presents a series of innovative educational approaches, ranging from the use of improvisation in the teaching of classical music performance, approaches bridging music theory and performance, as well as critical-response theory and reflexive methods. Each chapter is built on accounts of individual teaching practices rather than on general teaching models. All of which converge in promoting student autonomy and critical thinking, paving the way for novel creative approaches to music performance teaching and learning.

Mariam Kharatyan’s chapter, ‘Score-Based Learning and Improvisation in Classical Music Performance’, is based on personal reflections on how a classical pianist may develop individual approaches to the interpretation and performance of classical music by contextualising the compositions and experimenting with their performance practice through the use of improvisation. Further, Kharatyan explores how sharing such practices with students has created new opportunities for students to develop their voices. Robert Sholl, on the other hand, employs improvisation as a tool in a performance-oriented approach to music theory. His chapter, entitled ‘Reconnecting Theory: Pedagogy, Improvisation, and Composition’ introduces students to the craft of improvised counterpoint through exercises based on Bach’s Goldberg variations. Jacob Thompson-Bell, in his chapter ‘Shared Learning Environments: Amplifying Group Agency and Motivation with Conservatoire Musicians’, introduces the reader to a practice of applying a Critical Response Process feedback framework (CRP) to the teaching and learning of music performance. The chapter provides a theoretical framework through which CRP can be understood but also critically assessed and evaluated. Finally, Richard Fay, Daniel Mawson, and Nahielly Palacios, in their chapter ‘Intercultural Musicking: Reflection in, on, and for Situated Klezmer Ensemble Performance’, provide an outline of how reflective practices in music performance may form a basis for intercultural learning.

Part III, ‘Challenges and Opportunities of Music Performance Education in Society’, provides four perspectives on the challenges and possibilities for Higher Music Education. Perspectives address a range of issues including performance in intercultural contexts to several approaches to innovate in the design of educational programmes and curricula in response to changes in society. These changes include course developments which ensure that the higher music education curriculum is truly inclusive and diverse, with a global approach to pedagogy. Beyond the already existing skill-centred model of music performance education, the authors in this section propose a teaching/learning environment based on critical self-reflection and broader social reflexivity, meeting new artistic and societal challenges, such as linking artistic practice to the music industry (pedagogic approaches to embedding employability skills into the curriculum), community intervention (engaging with student and staff identities and creative voices to ensure an authentic education is crafted to develop individual needs), and inclusion (ensuring that students can see themselves represented in the curriculum).

Sarah-Jane Gibson’s chapter, ‘Experience, Understanding and Intercultural Competence: The Ethno Programme’, explores how the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded Ethno project, in the UK, develops participants’ cross-cultural understanding, across genres and in improvisatory live spaces, in order to prepare HME students for professional employment. Odd Torleiv Furnes’s chapter, ‘The Musical Object in Deep Learning’, defines, clarifies, and critiques how deep learning can be facilitated within a HME curriculum to ensure both an aesthetic and embodied experience of music performance during the learning process. Randi Margrethe Eidsaa and Mariam Kharatyan reflect on an initial stage of the REACT project in relation to their own teaching, learning and creative practice in Norway. In ‘Rethinking Music Performance Education Through the Lens of Today’s Society’ they advocate for a student-centred interdisciplinary approach to facilitating students’ understanding of the multiple possibilities of making music in contemporary society. Helen Julia Minors’s chapter, ‘Integrating Employability Skills within an Inclusive Undergraduate and Postgraduate Performance Curriculum’, explores specific case study projects, which she led in the UK, which resulted in a revision of the HME curriculum to ensure it was both inclusive for all students and that the HME approach was relevant to contemporary employability skills. There is variability in these four chapters (two based in Norway and two in the UK), which intentionally shows different ways to develop a performance curriculum that is contemporary, placing students’ creative voices and their individual developmental musical needs at the core of the educational design.

This book is developed also with the aim of addressing the increasing need for HME to reassess the relation to other professional music institutions. It brings together diverse voices working within HME—ranging from artistic researchers, who are also often professional performers, lecturers, postgraduate researchers, performance tutors, heads of department, and senior managers—to encourage the creation of closer collaborative bonds with music industries. Hereby, HME can develop teaching approaches that more efficiently further students’ professional career opportunities. In combination with the videos in the MOOC, the final aim of this book is to fuel such developments and to instigate future actions in this field.

References

Cobussen, Marcel, ‘The Trojan Horse. Epistemological Explorations Concerning Practice Based Research’, Dutch Journal of Music Theory, 12/1 (February 2007), 18–33.

Crispin, Darla, ‘The Deterritorialization and Reterritorialization of Artistic Research’, Online Journal for Artistic Research, 3 (2019), 45–59

Crispin, Darla, ‘Looking back, Looking through, Looking beneath. The Promises and Pitfalls of Reflection as a Research Tool’, in Knowing in Performing: Artistic Research in Music and the Performing Arts, ed. by Annegret Huber, Doris Ingrisch, Therese Kaufmann, Johannes Kretz, Gesine Schröder, and Tasos Zembylas (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2021), pp. 35–50

Dalagna, Gilvano, Sara Carvalho and Graham Welch, Desired Artistic Outcomes in Music Performance (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429055300

De Assis, Paulo, Logic of Experimentation: Rethinking Music Performance through Artistic Research (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2018)

Dromey, Chris and Julia Haferkorn, The Classical Music Industry (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018)

Eidsaa, Randi, ‘Dialogues between Teachers and Musicians in Creative Music-Making Collaborations’, in Musician-Teacher Collaborations: Altering the Chord, ed. by Catharina Christophersen, Ailbhe Kenny (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), pp. 133–45

Jørgensen, Harold, ‘Western Classical Music Studies in Universities and Conservatoires’, in Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning, ed. by Papageorgi, Ioulia and Welch, Graham (Ashgate: Surrey, 2014), pp. 3–20

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe and Dawn Bennett, ‘A Lifespan Perspective on Multi-Professional Musicians: Does Music Education Prepare Classical Musicians for their Careers?’, Music Education Research, 22 (2020) 1, 1–14, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/14613808.2019.1703925

Nelson, Robin, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond): Principles, Processes, Contexts, Achievements, 2nd edn (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2022)

Östersjö, Stefan, ‘Artistic knowledge, the laboratory and the hörspiel.’ in Gränser och oändligheter –Musikalisk och litterär komposition, en forskningsrapport /‘Compositional’ Becoming, Complexity, and Critique, ed. by Anders Hultqvist and Gunnar. D. Hansson (Gothenburg: Art Monitor, 2020).

Rowley, Jennifer, Dawn Bennet, and Patrick Schmidt, Leadership of Pedagogy and Curriculum in Higher Music Education (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019) p. 178

Sloboda, John, Musicians and Their Live Audiences: Dilemmas and Opportunities. Understanding Audiences ([n. p.]: Scribd, 2013), https://pt.scribd.com/document/538118141/Sloboda-John-Musicians-and-their-live-audiences-dilemmas-and-opportunities

1 Paulo de Assis, Logic of Experimentation: Rethinking Music Performance through Artistic Research (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2018), p. 150, https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461662507

2 Ben Spatz, Making A Laboratory. Dynamic Configurations with Transversal Video (Santa Barbara, CA: Punctum Books, 2020), https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.2353794

3 Stefan Östersjö, ‘Artistic knowledge, the laboratory and the hörspiel.’ in Gränser och oändligheter –Musikalisk och litterär komposition, en forskningsrapport /‘Compositional’ Becoming, Complexity, and Critique, ed. by Anders Hultqvist and Gunnar. D. Hansson (Gothenburg: Art Monitor, 2020).

4 Darla Crispin, ‘The Deterritorialization and Reterritorialization of Artistic Research’, Online Journal for Artistic Research, 3 (2019), 45–59.

5 Darla Crispin, ‘Looking back, Looking through, Looking beneath. The Promises and Pitfalls of Reflection as a Research Tool’, in Knowing in Performing: Artistic Research in Music and the Performing Arts, ed. by Annegret Huber, Doris Ingrisch, Therese Kaufmann, Johannes Kretz, Gesine Schröder, and Tasos Zembylas (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2021), pp. 35–50.

6 Marcel Cobussen, ‘The Trojan Horse. Epistemological Explorations Concerning Practice Based Research’, Dutch Journal of Music Theory, 12/1 (February 2007), 18–33.

7 Harold Jørgensen, ‘Western Classical Music Studies in Universities and Conservatoires’, in Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning, ed. by Ioulia Papageorgi and Graham Welch (Ashgate: Surrey, 2014), pp. 3–20.

8 Randi Eidsaa, ‘Dialogues between Teachers and Musicians in Creative Music-Making Collaborations’, in Musician-Teacher Collaborations: Altering the Chord, ed. by Catharina Christophersen and Ailbhe Kenny (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), pp. 133–45.

9 Guadalupe López-Íñiguez and Dawn Bennett, ‘A Lifespan Perspective on Multi-Professional Musicians: Does Music Education Prepare Classical Musicians for their Careers?’, Music Education Research, 22 (2020) 1, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1703925

10 Jennifer Rowley, Dawn Bennett, and Patrick Schmidt, Leadership of Pedagogy and Curriculum in Higher Music Education (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019) p. 178.

11 Chris Dromey and Julia Haferkorn, The Classical Music Industry (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), p. 30.

12 University of Aveiro (Portugal), University of Agder (Norway), University of Nicosia (Cyprus) Uniarts/Sibelius Academy (Finland), and Luleå University of Technology (Sweden).

13 David Gorton and Stefan Östersjö, ‘Negotiating the Discursive Voice in Chamber Music’, in Performance, Subjectivity, and Experimentation, ed. by Catherine Laws (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020).

14 The MOOC is available in the following website: https://react.web.ua.pt

15 Robin Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond): Principles, Processes, Contexts, Achievements, 2nd edn (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2022).