1. Etosha-Kunene, from “pre-colonial” to German colonial times

©2024 S. Sullivan, U. Dieckmann & S. Lendelvo, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.01

Abstract

We outline “pre-colonial” and German colonial structuring of “Etosha-Kunene”, leading in the early 1900s to the institution of formal game laws and game reserves as key elements of colonial spatial organisation and administration. We review the complex factors shaping histories and dynamics prior to formal annexation of the territory by Germany in 1884. We summarise key Indigenous-colonial alliances entered into in the 1800s, and their breakdown as the rinderpest epidemic of 1897 decimated indigenous livestock herds and precipitated enhanced colonial control via veterinary measures and a north-west expansion of military personnel. A critical and collaborative Indigenous “uprising” in the north-west in 1897–1898—known variously as the Swartbooi or Grootberg Uprising—was met by significant military force, disrupting local settlement and use of the area stretching from south of Etosha Pan towards the Kunene River. It resulted in the large-scale deportation of inhabitants of the area, who were brought to Windhoek for mobilisation as forced labour for the consolidating colony. An intended outcome was the clearance of land for appropriation by German and Boer settler farmers, a process that also contributed to establishing a massive game reserve in Etosha-Kunene in subsequent years. The proclamation of “Game Reserve No. 2” in 1907 can be seen as the beginning of a long and varied history of formal colonial nature conservation in Etosha-Kunene, whose shifting objectives, policies and practices had tremendous influence on its human and beyond-human inhabitants.

1.1 Introduction1

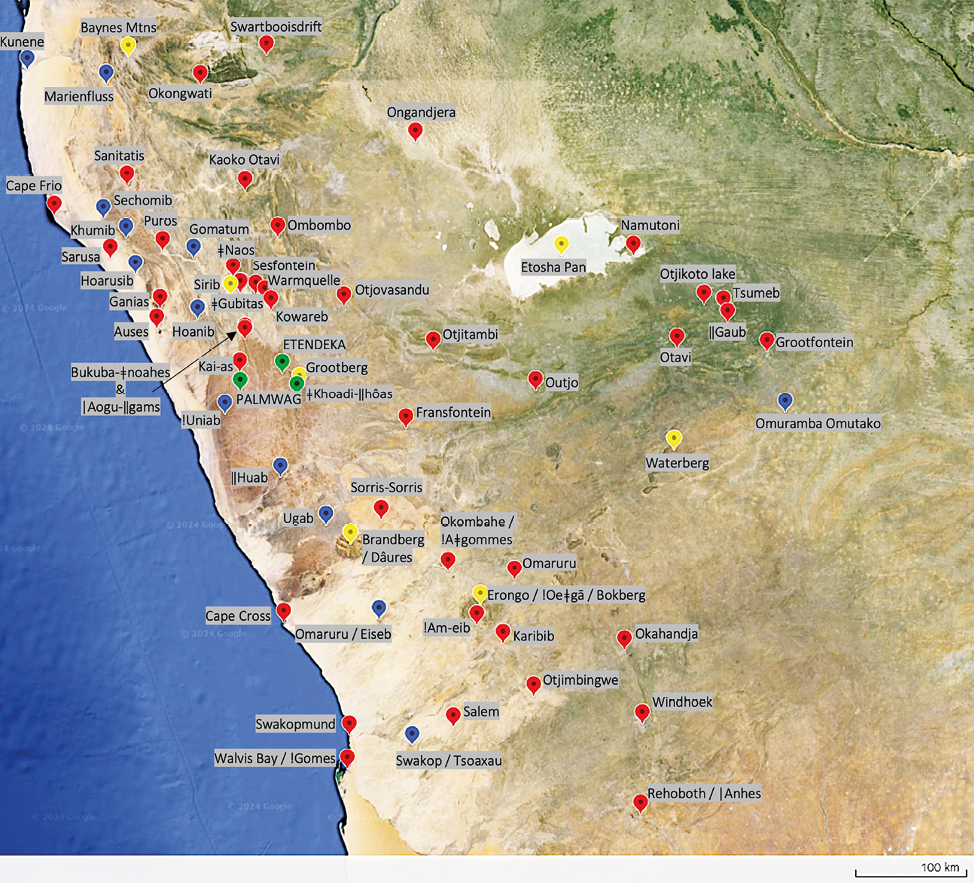

Part I of this volume provides an overview of historical circumstances that left their mark on the peoples and landscapes of “Etosha-Kunene” as a connected area of north-central and north-west Namibia. There are many ways in which we could disaggregate and periodise the history of environmental policy and nature conservation for this area. In this chapter—the first of three considering historical and contemporary factors shaping this broad area (see Chapters 2 and 3)—we focus first on the mid- to late-1800s (Section 1.2). Here we trace some of the complex shifts through multiple interactions and events that rather unexpectedly led to state colonisation by Germany through the territory’s formal annexation in 1884 (Section 1.3). This highly disruptive period of colonial reorganisation saw the emergence of the first colonial state efforts towards formal “game preservation” through various state laws, and the gazetting of a Game Reserve that included a very large part of Etosha-Kunene. For ease of reference, Figure 1.1 shows the locations of most of the places mentioned in this chapter.

1.2 Etosha-Kunene, prior to German colonisation

Given our emphasis in this volume on histories of conservation and conservation policy, we focus here on the growing impact of firearms and hunting on indigenous fauna, or so-called “game” (Section 1.2.1). We draw attention to a parallel general rise in concern about human impacts on colonised environments (and elsewhere), later manifesting in formal legislation for the territory to restrict hunting and set aside areas of land for the protection of flora and fauna (Section 1.3.3). We touch on the importance of natural history specimen collecting in the period prior to formal annexation (Section 1.2.2), and on the ways that early, mostly European, colonial-era travellers, traders, hunters and missionaries drew into focus particular perspectives on the diverse African peoples they encountered. We revisit the so-called “ovaKuena wars” dominating many contemporary representations of the north-west (Section 1.2.3), considering how representations of those encountered in the past linger to this day in conservation visioning for the area.

Fig. 1.1 Map of places (red), rivers (blue), topographical features (yellow), and tourism concessions and conservancies (green) mentioned in this chapter. Prepared by Sian Sullivan, including data from Landsat / CopernicusData SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Imagery starting from 10.4.2013. © Etosha-Kunene Histories, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

1.2.1 Firearms, hunting and indigenous fauna

Prior to the legislated establishment of Game Reserves in 1907 (Section 1.3.3), Etosha-Kunene was increasingly drawn into external focus through the perspectives and writings of diverse colonial actors from the “global north”.2 Much of what is outlined below comes from those who wrote about their experiences; as well as from historical analyses of their narratives and the impacts of these pre-1900s hunters, traders and travellers from especially the Cape Colony, Britain, Sweden, North America, and increasingly from Germany. Figure 1.2 shows the extent of travel in north-west Namibia undertaken by a selection of these actors.3 These individuals were interested in commercial opportunities, especially cattle for trading, ivory from elephant (Loxodonta africana), ostrich (Struthio camelus) feathers, animal hides and guano found along the coast. They aimed to develop transport routes that would support their interests, and increasingly to acquire land and labour for their own commercial activities.

Fig. 1.2 Selected colonial journeys through Etosha-Kunene, prior to 1900. Prepared by Sian Sullivan using Google Maps: Map data © 2024 Google, INEGI Imagery © 2024 NASA, TerraMetrics. Full annotated map linked at https://www.etosha-kunene-histories.net/wp4-spatialising-colonialities, © Etosha-Kunene Histories, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

These colonial-era travellers and traders were also curious about the natures and cultures they encountered. The collection of “natural history” specimens for review by growing scientific establishments in the metropole formed a focus of their efforts; as did the documentation and mapping of the peoples they encountered (Section 1.2.2). Whilst providing significant sources with which to understand early historical contexts, these narratives also need to be read carefully for the instrumentalising, objectifying and colonising assumptions they convey. In the latter part of the 1800s (building on earlier missionary enterprise in southern and central areas of the territory), expansion of especially the Rhenish and Finnish missionary societies occurred in conjunction with commercial and colonial acquisition in Etosha-Kunene.

The mid-1800s in southern Africa were already shaped by concerns regarding environmental damage and the decline of populations of species encountered in these lands (see Table 1.1 below)—especially associated with the decline of fauna due to commercial hunting.4 In 1850, at the Rhenish Mission Society (RMS) station at Otjimbingwe to the south of Etosha-Kunene, Francis Galton—a British explorer and later founder of eugenics—observed, for example, that hunter and trader Hans Larsen had in the preceding seven years ‘utterly shot off all the game’ in the Swakop (Tsoaxau) River area; and had also ‘shot a great many lions out of the Swakop’, making it ‘a much safer place than it used to be to drive cattle in’.5 Referring to lions, Galton commented on ‘how in a short time one or two guns would entirely exterminate them’.6 Indeed, in this pivotal mid-1800s moment, the introduction of firearms had an immense impact on wildlife in the territory that over the following 150 years would be governed as Deutsch-Südwestafrika, South West Africa, and formally as Namibia after 1990.7

These declines notwithstanding, in the mid-1800s Galton and his travelling companion—the Anglo-Swede Charles John Andersson—were able to observe large populations of diverse fauna as they travelled north-eastwards from the Swakop River towards Etosha Pan. In May 1851 they reached Otjikoto lake to the south-east of the Pan, finding ‘wildlife in large numbers, although rhinoceros was rarely encountered’.8 They were apparently the first Europeans to record the existence of Etosha Pan, later forming the focus of Namibia’s flagship protected area, Etosha National Park (ENP) (see Chapter 2). They saw a glimpse of Indigenous socioeconomic complexity in this area when they reached Omutjamatunda, now well-known as the tourism resort of Namutoni but then an important Ndonga (Owambo) cattle-post and source of salt for trade north of the Kunene River:

[w]e got water at Otchando, and came to the first Ovampo cattle-post at Omutchamatunda [Namutoni]. Travelling on, we arrived suddenly at the large salt-pan of Etosha, which is about 9 miles across from N. to S., and extends a long way to the W. […] This lake is impassable in the rainy season, but was perfectly dry when I saw it, and its surface was covered over in many parts with very good salt.9

Galton and Andersson were travelling in the company of Ndonga traders from north of Etosha Pan who in these years regularly exchanged ‘iron spearheads, knives, rings, iron and copper beads’ for Herero cattle further south; they also acquired copper mined by ‘the San community living in the Otavi area to the southeast of Etosha Pan’.10 Owambo of north-central Namibia additionally traded cattle, iron and copper items—and later muzzle-loading guns acquired from Portuguese to the north—for ostrich egg shells and ivory with ovaTjimba in the west: oral history refers to cattle-posts of Owambo11 kings in Kaoko in the north-west, probably drawing in raided cattle.12 At Namutoni, Galton and Andersson observed 3–4,000 head of cattle, as well as springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) and zebra (Equus quagga burchellii), with Andersson giving an impression of lushness:

there is a most copious fountain, situated on some rising ground, and commanding a splendid prospect of the surrounding country. It was a refreshing sight to stand on the borders of the fountain, which was luxuriantly overgrown with towering reeds, and sweep with the eye the extensive plain encircling the base of the hill, frequented as it was not only by vast herds of domesticated cattle, but with the lively springbok and troops of striped zebras.13

Galton illuminates the broader new impacts of European trade in the territory at this time, estimating that some 8–10,000 head of cattle, and many more small stock, were being sent overland annually to the Cape.14 A significant rise in commercial hunting was also unfolding in these years, particularly for ivory traded northwards following ‘the dissolution of the [Portuguese] government monopoly of the ivory trade’ in 1834.15

By the 1860s, game stocks in southern Angola were depleted, encouraging interest south of the Kunene River.16 Kaokoveld in the north-west of the territory now known as Namibia supplied ivory to traders from the east in these years.17 The scale of hunting is illustrated by a figure of over 700 elephants estimated to have been shot by Canadian trader and ‘big-game hunter’ Frederick Green, between 1854 and 1876.18 Owambo kingdoms in north-central Namibia were also engaging in commercially oriented ivory hunting, with a rule that one of each pair of tusks hunted should become the property of the relevant king, such that leaders could accumulate ivory.19 By the late 1800s, entrepreneurial interest in ‘cattle, ivory, ostrich feathers and copper from the interior’ led to ‘[r]epresentatives of various merchant houses’ negotiating ‘concessions’ with local people, involving ‘[n]umerous traders of diverse nationalities’.20

This hunting-based entrepreneurial activity was highly dependent on the specialist knowledge of local guides and hunters, with specific local actors in this enterprise having significant impacts on later historical developments in the territory. German missionaries Carl Hugo Hahn and Johannes Rath, travelling together with hunter Frederick Green, deployed Haiǁom “Bushmen” as guides in the 1850s;21 and the American trader Gerald McKiernan, travelling in the area between 1874–1879, also reports that Haiǁom acted as guides, trackers and messengers for elephant hunts.22 Swedish trader Axel Eriksson employed ‘Hottentot23 and Griqua hunters’, spending ‘some years as an elephant and ostrich hunter’, and making ‘a good profit out of it’.24

The life of Vita “Oorlog” (i.e. “war”) Thom (also “Harunga”25) is illustrative here. Born in 1863 into ‘the matrilineage of a prominent Herero family at Otjimbingwe on the Swartkop [Swakop] River’ with a Tswana father26 called Tom Bechuana (a guide of Galton’s),27 Vita Thom became involved in commercial hunting in central and northern Namibia with Andersson and Eriksson.28 In 1917, he recounted to Major Charles N. Manning, the first Resident Commissioner of Owamboland in the immediate post-German colonial period, that:

[w]hen old enough to shoot I went with my father [Tom Bechuana] under [Frederick] Green the hunter elephant shooting on OKOVANGO [sic] RIVER thence ONDONGA under OVAMBO Chief KAMBONDE where we met hunter [Axel] ERICKSON [Eriksson] known as KARAVUPA. My father had been with Green and Missionary Hahn at Ondonga before when Chief NANGORO tried to kill them [in 1857].29 Erickson, my father and I went to OVAKUANYAMA country and Green went South again.30

Sometime later Tom Bechuana and his son Vita Thom left Otjimbingwe due to conflicts between Nama/Oorlam31 and ovaHerero leadership in central Namibia, travelling northwards32 where they would have a strong effect on local politics (also see Chapter 7).

In the 1870s, hunter James Chapman is known to have made ‘several hunting trips to Kaoko and western Owambo’,33 whilst Transvaal Boers (“Trekboers”34) moving into Kaoko also participating in commercial hunting.35 In these years prior to formal colonisation (see Section 1.3) influential traders such as Charles John Andersson and Frederick Green took advantage of divisions between different Indigenous “groups”. In the 1860s, for example, they enlisted ‘Herero aid to end Oorlam-Nama control over the trade routes’, shifting the balance of power ‘from among local pastoralists to the traders themselves’, who ‘established permanent trading centres to exploit the country’s resources’ from which they made ‘enormous profits’.36

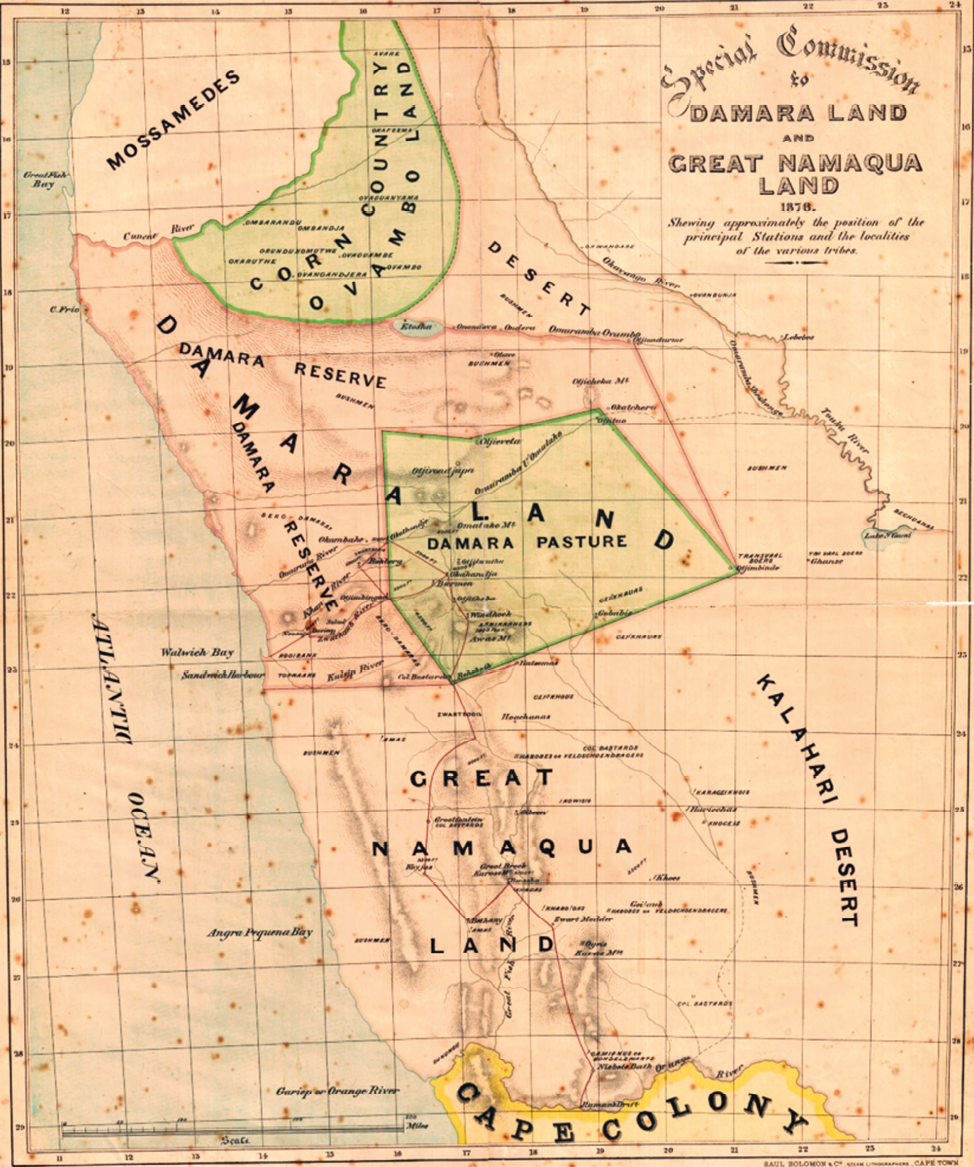

In the late 1870s, William Coates Palgrave, Special Commissioner for the British Cape Colony to “Damaraland” and “Great Namaqualand”, makes reference to ‘competing claims for Kaoko by Swartbooi and Herero leaders in central Namibia’.37 “Damaraland” in these years was a commonly used name for the swathe of central Namibia into which ovaHerero pastoralists had moved in the late 1700s from southern Angola and north-east Kaokoveld.38 By 1876, commercial European hunters and traders were known to travel from Kaokoveld in the west to Ongandjera in the Uukwambi area of ‘Owamboland’.39 Kamaherero, the ovaHerero leader based in Okahandja, stated in this year a wish that all hunting should cease whilst Palgrave was absent in the Cape because ‘[p]eople go into the hunting veldt, and live there permanently, and so drive away all the game, and we suffer in consequence’; although Palgrave resisted this proposal.40

In the presence of Palgrave, Kamaherero and other ovaHerero captains—with the help of English trader and prospector Robert Lewis41—mapped their claim to a huge area of the territory, minimising the presence of Indigenous Sān, Damara/ǂNūkhoen and Nama: see Figure 1.3. They reportedly ‘set aside a tract of country for a “Reserve” for the Government’,42 including ‘the whole Kaokoveld and the west coast as far [south] as the level of Rehoboth, as well as part of Ovamboland’.43 In doing so, they indicated that these lands were not considered central for ovaHerero livelihoods at this time, given relocations south by ovahona (wealthy herders)—such as the well-known Mureti who moved to the Omaruru area in 1861.44 Palgrave reports that the inhabitants of the so-called ‘Damara Reserve’ area on Figure 1.3 ‘consist of Berg Damaras, Bushmen and Namaquas’: estimating ‘Berg Damaras’ [ǂNūkhoen] to number around 30,000, of which half live in ‘the Reserve’, ‘their claims to the land […] disregarded by the Namaquas as well as by the Hereros’—although Okombahe was ‘granted to them by the Hereros’ around 1873 ‘upon the urgent representations of the missionaries’.45 Palgrave observes that ‘there are already in Damaraland a number of people [Europeans] who wish to hire land [e.g. in the ‘Damara Reserve’] and only wait for some guarantee that the terms of their leases will be respected’.46 Palgrave estimated the different population groups in ‘Damaraland’ as follows: ‘Herero or Cattle Damaras’ 85,000; ‘Houquain or Berg Damaras’ [[ǂNūkhoen] 30,000; ‘Bushmen’ 3,000; ‘Namaquas’ 1,500; ‘Bastards’ 1,500; ‘Europeans and other Whites (not including Boers) 150.47 Swartbooi/‘Khau-goas [ǁKhau-|gôan] or Young Red Nation’ under Abraham Zwartbooi, defined as ‘pure Namaquas’, were estimated at 1,000.48

The growing power and influence of Europeans was also contested and attacked. For example, in 1864 a miner, hunter, and trader called H. Smuts working for Andersson—as well as white hunters Robert Lewis and J. Todd—were robbed in Kaokoveld by an Oorlam Nama individual known as ‘Sammel’ (Samuel) and associates.49 Formerly a subject of Jonker Afrikaner—the Oorlam leader who dominated politics in central Namibia in the mid-1800s—Sammel had become established ‘on a high mountain called Otjironjupa50 situated about 80 miles NNE of Otjimbingwe’, as recounted in the journal of the Swedish traveller and hunter Thule Gustav Een.51 By the 1870s, however, the balance of power was shifting towards European traders. Boer and Portuguese traders and hunters in Kaoko and southern Angola, with firearms and ox wagons, started to crowd out the African/Oorlam presence.52 When Catholic missionary Carlos Duparquet reached western Etosha in 1879, he thus met ‘numerous [commercial] hunters at places such as Otjivazandu [Otjovasandu] and Ombombo’53 (see Chapter 14).

Alongside hunting and trading influences was a growing interest in establishing mission stations in the north. In late July of 1857, for example, trader and hunter Frederick Green, in the ill-fated expedition to Ondonga mentioned above, included Rhenish Missionaries Hahn and Rath who were seeking ‘new mission fields’ beyond ‘Damaraland’.54 The Trekboer presence had become increasingly significant in these years, with around one hundred Afrikaner Dorstland/Thirstland trekkers travelling with ox wagons through Nyae Nyae in the Kalahari towards Angola, via Kaokoveld springs such as Kaoko Otavi.55 Their circumstances were often vulnerable. In 1879, Trekboer Gert Alberts led a small mounted party down the valley of the Hoarusib River to the sea in an attempt to collect supplies gathered in response to an appeal by trader Axel Eriksson: becoming the first white men to traverse the Kaokoveld from east to west.56 In this decade ‘business with ivory [and cattle] from the northern areas both to Mossamedes and to Walvis Bay flourished’, although ‘traders complained that there was no longer enough ivory and cattle to buy in Owambo’.57 A published return of 40,000 lbs of gunpowder and 300,000 cartridges shipped through Walvis Bay in 1879–80 illustrates the scale of inland hunting:58 “game” was considered exhausted in central Namibia and the Kalahari, causing a withdrawal of commercial hunters around this time.59 In 1881, the last herd of elephants near Namutoni was reportedly shot by European hunters, with lion and rhino surviving only in remote and inaccessible areas.60

Fig. 1.3 ‘Map of WC Palgrave Commission to report on the people and states of Damaraland and Namaqualand and inform decision on merging Government of Cape of Good Hope with states of South West Africa’, 12.12.1876. Source: Cape Archives—Palgrave Papers. Public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/24/1876_-_map_from_Palgrave_Commission_papers.png, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Clearly colonial-era activity caused observable damage to wildlife populations in these years, providing impetus for the establishment of formal conservation policy in the Cape Colony (and elsewhere): see Table 1.1.61 Although opposed by Kamaherero, in August 1878 Palgrave introduced ‘hunting and trading licences to defray the proposed expenses of the [Cape Government Walvis Bay] magistrate’: initially welcomed by traders on the understanding that ‘they would be protected by government’.62 These rising concerns and accompanying legislation provide additional context for the later impetus to formalise state wildlife protections in Deutsch Südwestafrika, as considered in Section 1.3.3.

Table 1.1 Emerging formalisation of environmental concern and associated protection policies in the Cape Colony and elsewhere, mid- to late-1800s.

1.2.2 Cataloguing and Mapping

Alongside the processes of commercialisation and extraction documented in Section 1.2.1—with their corresponding impacts and causes for concern—the mid- to late-1800s were notable for the time, energy and resources devoted by many travellers to Etosha-Kunene to tracking down, killing and preparing natural history specimens for collections later housed in museums elsewhere, often in their home countries. Charles John Andersson’s first collections, for example, ‘including about 500 bird-skins and 1 000 insects’,63 were brought by Galton to England in 1852. More insects were donated to the South African Museum in 1860, and the rest of his collections are housed in Swedish museums and the Nottingham Museum in the UK.64 Swedish trader Axel Eriksson created a large collection of bird specimens from the territory, mostly donated to the municipal museum in his home town of Vänersborg, which as a result hosts the world’s largest exhibition of Namibian birds.65 A large collection of insect specimens was also donated by Eriksson to the South African Museum in Cape Town, and a large number of bird skins collected by him are currently housed in Uppsala’s Evolutionsmuseet. The first plant specimens from Kaokoveld were probably collected along the Kunene River in 1878 by the Rev. Duparquet.66

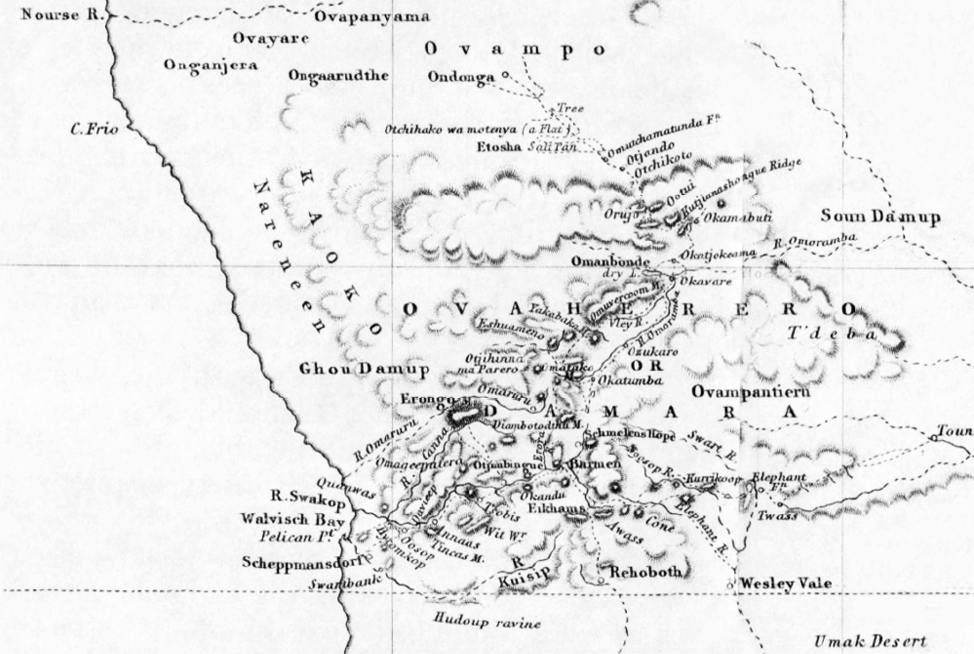

Procured as an objective and objectifying catalogue of encounter with exotic natures, these colonial collections and associated displays acted in the past as ‘imperialistic propaganda’; leaving us today with ‘a passive witness’ of past relationships with plants and animals that communicates something of how nature in the colonial encounter was approached and dealt with.67 This mapping and cataloguing of the natures of the territory was accompanied by the mapping of lands and cultures. For example, in 1852, Galton’s mapping work was ‘professionally transcribed onto a map by Livingstone, Oswell and Gassiot of London’ and published in this year.68 This map, reproduced in Figure 1.4, clearly shows people named as ‘Nareneen’, presumably referencing Khoekhoegowab-speaking !nara-harvesting !Narenin west of the ‘Kaoko’ mountains (see Chapter 12).69 Damara/ǂNūkhoen (denoted using a derogatory name ‘Ghou Damup’) are positioned north-west of Erongo, and ‘Soun Damup’ east of Outjo.70 ‘Damara’, referencing ovaHerero, dominate central Namibia, although Galton reports that they had come to inhabit these lands only around 50 years prior to his mid-1800s travels. Damara/ǂNūkhoen and Haiǁom documented in early traveller maps tend to be positioned between groups that became more dominant historically (also Figure 1.16). Such maps reflect the biases and prejudices of their authors, as well as attempts to fix otherwise fluid, overlapping and interconnected “groupings” of people in an essentialising manner,71 extended later into the establishment of so-called “Native Reserves” and “Homelands” (see Chapter 2).

Fig. 1.4 Detail from Francis Galton’s map of Africa between 10 and 30 degrees south. Source: Galton (1852: 141, out of copyright), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

1.2.3 Khoekhoegowab and otjiHerero speakers in north-west Namibia, mid-to late 1800s: Revisiting the “ovaKuena wars”

A key characterisation of north-west Namibia from the 1850s onwards is of ‘marauding bands’72 of Oorlam Nama commandos with firearms—referred to with the otjiHerero exonym ovaKuena73—raiding the livestock of ‘Bantu-speaking pastoralists of Kaokoland’.74 Vita Thom, the Tswana-Herero guide to European hunters mentioned above, thus reports to Manning in Sesfontein in 1917:

before my sons were born (about 30 years ago? CNM. [i.e. late 1880s]) an OVATSHIMBA named MUHONA KATITI being driven out from Kaokoveld by Hottentots came to me in Angola with his people for protection. He had nothing and I gave him cattle and small stock also a blanket. He wears no clothing like us. I got Portuguese authority for him to live near me. He got rich and left me to go to TSHABIKWA in Angola.75

This period of the 1800s, and how it is understood and conveyed, arguably remains a determining factor into contemporary times, underlying frictions arising in the context of post-Independence conservation praxis in Etosha-Kunene.76 For this reason, this history will be considered in some depth here. It also provides critical background for the emergence of Indigenous resistance in the north-west as German colonisation took hold in the 1890s, as outlined in Section 1.3.2.

In around the 1700s (i.e. seven to ten generations from the mid-1990s, assuming 25 years per generation), oral history reported by anthropologist Michael Bollig indicates that otjiHerero-speaking peoples began trekking westwards down the Kunene River, reportedly prompted by drought.77 They were migrating from a hill in southern Angola called Okarundu Kambeti: moving into hills on either side of the Kunene78 that, like the Orange River, is referred to as !Garib by Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples.79 Cattle and sheep are described as coming from the north, and goats from the south, the pastoral economy including hunting, gathering—especially of Hyphaene petersiana palm fruits, Cyperus fulgens corms (ozoseu) and honey—but without agriculture until the end of the 19th century,80 perhaps following interactions with immigrating Trekboers. Bollig states that ‘these early migrants did not enter an unpopulated area or an area only thinly populated by foragers (presumably of Khoisanid origin)’, but according to oral testimony ‘met with other pastoralists […] rich in livestock and culturally akin to themselves’.81 In current strategies to claim “Kaokoveld”, it is asserted that this ‘pre-Kuena War society was dominated by ovahona (rich and powerful men) such as Kaoko’—reportedly ‘the giver of the name for the entire region’—as well as ‘Kaupanga and Mureti in northern and eastern Kaokoland, Tjikurundjimbi in the western parts and Nokauua in the southern parts’; although there were reportedly ‘few ovahona’ and ‘many people had few livestock’.82 Cattle raiding was a known feature of the regional livestock economy. A significant raiding event remembered in oral histories with pastoralists of north-east Kaokoveld is recorded as the ‘War of the Shields’: cattle were seized by oshiWambo-speaking ‘Ovahuahua’ from the north, the raids named as such because these warriors ‘protected their bodies with shields against the arrows of the Herero’.83

This regional herding and raiding economy becomes shaped in the mid- to late 1800s by northwards moving Indigenous Swartbooi (ǁKhau|gôan) and Topnaar (!Gomen) Nama, often framed very negatively in contemporary literature. Echoing to some extent a 1953 narrative by popular author Lawrence Green, in 1972 well-known conservationist the late Garth Owen-Smith writes, for example, that:

[i]n the Herero/Nama wars of the last century, most of the Kaokoveld natives (Herero) lost their cattle and became known as the OvaTjimba. […] In the second half of the nineteenth century, marauding bands of Topnaar and Swartbooi Nama came to Sesfontein where they settled after driving out the Herero and subjugating the Damara [ǂNūkhoen]. In the following years the once considerable herds of cattle, belonging to these Nama, have been depleted by disease and drought and today they rely largely on crops irrigated from fountains at Sesfontein and Anabib [Anabeb].84

Recent analyses often repeat this description, for example:

as early as the 1850s, Oorlam commandos engaged in bloody stock raids in Kaokoveld, where the arid and rugged environment kept ovaHerero pastoralists decentralised and thus unable to mount a common defence. These raids pushed Kaokoveld ovaHerero as far north as Portuguese Angola [from where they had moved, some decades previously]. Among these raiders were the Swartboois who having moved north from near present-day Swakopmund, desired access to the large ovaHerero cattle herds.85

The so-called “ovaKuena” actors in these events tend to be standardised as ‘the Swartboois of Franzfontein and the Topnaar of Sesfontein’.86 ‘Access to the Kaokoveld’ is stated to have been controlled from the 1850s ‘well into the 1890s’ ‘by the well-armed Swartboois and Topnaar commando groups from their settlements at Sesfontein and Fransfontein’, these commandos also ‘preying upon elephants and trading ivory’.87 This violent raiding economy is described as being led from Sesfontein in particular, focusing on key places such Kaoko Otavi further north.88 OtjiHerero-speaking pastoralists were reportedly pushed into an ‘exodus’ across the Kunene, and a retreat into a foraging ‘Tjimba’ lifestyle in the Baynes Mountains,89 ‘later returning to NW Kaokoland in 1920 as the Himba pastoralists’.90 As ‘refugees’ requesting assistance north of the Kunene, from where ovaHerero pastoralist families had previously moved into Kaokoveld, they were named ‘Ovahimbe’ meaning ‘beggars’, the term now used as the ethnonym ‘Ovahimba’.91 Others reportedly moved southwards to Omaruru and Waterberg, or eastwards to Owambo.92 The consolidating and militarised power of the Tswana-Herero Vita Thom and his associates in the raiding economy of southern Angola and north-east Kaokoveld constituted an additional factor, stimulating later movements south-westwards by otjiHerero-speaking pastoralists.93

Without doubt, raiding occurred and was on occasion very violent. At the same time, this period of history did not only involve vicious “Oorlam Swartbooi and Topnaar Nama” and victimised “Kaoko Herero”. We revisit these histories to convey their more variegated nature: how this period is understood and represented remains relevant for conservation in north-west Namibia today.

As a starting point, consider a site of multiple graves south of Sesfontein in the land area known by Damara/ǂNūkhoen as Aogubus, crossing the northern parts of today’s Etendeka and Palmwag Tourism Concessions (see Chapter 13). Oral history identifies these graves as those of ǁKhao-a Dama (ǂNūkhoe) individuals reportedly shot by Nama alongside an ovaHerero man called ‘Buku’, hence the name of the site ‘Bukuba-ǂnoahes’: see Figure 1.5.94 In contrast, close to this site is a substantially marked grave of an Aogubu Damara/ǂNūkhoe man called |Ûsegaib: a prominent person who lived here with his three wives close to the spring known as |Aogu-ǁgams: see Figure 1.6. He was looking after goats belonging to Nama living in Sesfontein who came and built this large grave, bringing the pastor from Sesfontein to officiate at the burial.95 Clearly circumstances and alliances were highly dynamic, comprising both violence and respectful reciprocal arrangements. Fluidity and complexity is similarly reflected in a tale of the heroic actions of ǂNūkhoe warrior Tua-kuri-ǂnameb. He is famed for chasing down and attacking ovaHerero kidnappers of ǂNūkhoe children at the spring ǂNaos, which now feeds the settlement of ǂGubitas/Otjindagwe, west of Sesfontein: see Video 1.1.

Fig. 1.5 Site of around 10 graves near Bukuba-ǂnoahes in the Aogubus land area, south-east of Sesfontein, reportedly of ǁKhao-a Dama individuals. Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 22.2.2015, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Fig. 1.6 Ruben Sanib stands at the well-marked grave of the Aogubu Damara/ǂNūkhoe man |Ûsegaib, who herded livestock for Nama of Sesfontein near the spring of |Aogu-ǁgams south of Sesfontein, now in the Palmwag Tourism Concession. Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 22.2.2015, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Video 1.1 Ruben Sanib recounts the heroic actions of ǂNūkhoe warrior Tua-kuri-ǂnameb at sites that are part of the story. Video by Sian Sullivan (2015), at https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/7e9ca87f, © Future Pasts, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

As historian Lorena Rizzo writes, this period is characterised by ‘Kaoko’s instability and its shifting materiality as a territory and socio-political space’, with mobilities blurring ethnic, geographical and economic colonial boundaries.96 There are sources of complexity here that are worth making explicit: they have a bearing on contemporary concerns and biases as they play out today in conservation proposals and interventions in Etosha-Kunene. Indeed, excluded from most contemporary accounts of this period is the complexity of historical circumstances that shift the identities of those raiding in the north in the mid- to late 1800s, and add context about why later Swartbooi and Topnaar raiding occurred.

For example, the northwards migration by Topnaar and Swartbooi Nama occurred later than the 1850s and may for some have constituted a return to the north and to prior connections, rather than in-migration to an unknown area (as detailed in Chapter 12). If there were raids taking place this far north in the 1850s, they are unlikely to have been carried out by Swartbooi or Topnaar Nama specifically. Earlier Oorlam Nama raiding activity in north-east Kaokoveld was enacted by Oorlam leader Jonker Afrikaner who had form for raiding ovaHerero cattle in central Namibia (and vice versa).97 In 1857, for example, ‘Afrikaner Oorlams supported by the Rooinasie’—not Swartbooi or Topnaar Nama—undertook ‘raids into Kaoko’.98 In 1860, Jonker Afrikaner led an expedition of 40 wagons on a ‘raiding expedition to Ovamboland’, reportedly removing ‘20,000 head of cattle’ and reaching lands north-west of Etosha Pan where ovaHerero resided.99 These events no doubt contribute to assertions by ovaHimba in archive documents of an ‘Ovambo-Hottentot’ war that prompted southwards movements of ovaHerero from north-east Kaokoveld to central Namibia.100 In these years, however, ǁKhau-|gôan/Swartbooi Nama were located in southern and central Namibia at a time in which Andersson’s trading activities (led from Otjimbingwe) were ‘bring[ing] him into direct conflict with the Namaland chiefs and especially the sovereign, Jonker Afrikaner’, who claimed a monopoly on the cattle trade in central Namibia.101

In fact, in the 1860s Swartbooi were the only Nama faction to ally with ovaHerero leader Kamaherero against Oorlam Nama leader Jan Jonker Afrikaner.102 This alliance strengthened when Andersson recruited ovaHerero, including from the Kaokoveld, to attack Jan Jonker and his followers.103 In 1864, and with 2,500 men and a “national flag” designed with Thomas Baines from England, Andersson marched to Rehoboth to ‘join forces with the Swartbooi commando […] to attack the Afrikaners and their allies’, provisioning themselves from ‘Bergdamara’ werfts (settlements) along the way.104 This historical Swartbooi-Herero alliance appears to be absent in the “Kaoko literature” on Swartbooi attacks on ‘Kaoko Herero’;105 even though in 1876 Kamaherero iterates to Palgrave that ‘[t]he Rehoboth people [Swartboois] were always our friends and allies’.106 Having fought against ‘their immediate neighbours’ (Jan Jonker Afrikaner and ǁOaseb—leader of Kaiǁkhaun/Red Nation Nama), the Swartboois fled Rehoboth, trekking towards Otjimbingwe on the Swakop River: ‘just outside Rehoboth, they were surprised by an Afrikaner commando, had their cattle taken, their wagons burnt and several people wounded and killed’.107

As a consequence of this Swartbooi-Herero alliance, Swartbooi were forced to flee |Anhes (Rehoboth) under attack by a commando led by Jan Jonker Afrikaner,108 the Afrikaners having previously also acted to prevent alliance-building between Topnaar Nama of the !Khuiseb and Swartbooi Nama of Rehoboth.109 The latter eventually settled at Salem on the Swakop River, described in 1866 by Een as:

now an abandoned mission station inhabited by a Namaqua or Hottentot tribe under a chief with the name Svartberg [Swartbooi], the only Hottentot tribe living in peace with the Damara [Herero] people.110

From Salem they moved north to !Am-eib in the Erongo mountains (Figure 1.7), where Abraham Swartbooi (!Ábeb !Huisemab) was the Swartbooi leader at the time of William Coates Palgrave’s commission to the territory in 1876.111 They make it known that,

[t]hey desire to move into the Kaoko country, but are not allowed to do so by the Damaras [Herero], who are afraid of permitting the growth of a Namaqua power on their northern frontier, certain as they are that the Zwartboois would be joined by many of the others [sic] Namaquas.112

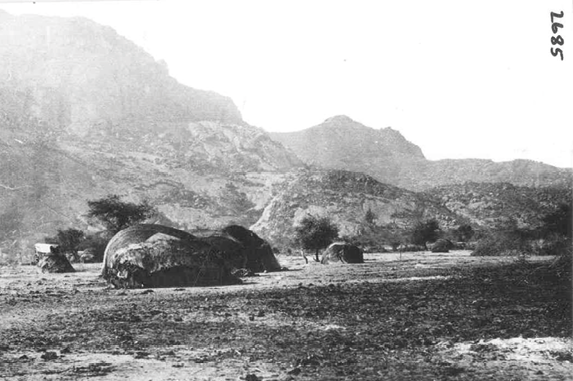

Given the lack of water at !Am-eib, the Swartboois speak of a desire to move to ‘Zesfontein’, with Palgrave trying to persuade them to stay at !Am-eib on the grounds that the Cape government will construct a dam for water provision—a promise that does not appear to have been met.113

Fig. 1.7 Swartbooi Nama huts at !Am-eib at the Erongo/!Oeǂgā mountains in 1876. Source: photograph 2685 from Special Commissoner William Coates Palgrave expedition, © National Archives of Namibia, used with permission.

Regarding Topnaar Nama who became key actors in the Sesfontein area in the late 1800s: the chronicle of Otjimbingwe for 1864 documents that Topnaar living in the !Khuiseb valley joined forces with the Swartbooi, heading northwards with missionary Johannes Böhm, settling first at !Am-eib, south of the Erongo/!Oeǂgā mountains (Figure 1.7),114 where Damara/ǂNūkhoen also resided.115 !Gomen Topnaar from south of the Walvis Bay area relocated northwards under their chief |Uixab, half of their group staying ‘in their original territory’ (i.e. !Gomes/Walvis Bay).116 It was reportedly only around 1880, when water at !Am-eib became scarce, that the Swartbooi and the Topnaar moved northwards reaching Okombahe (!Aǂgommes), Anixab, Otjitambi and Fransfontein. They also moved into Angola, via the eastern Kaokoveld and the Kunene River crossing that became known as Swartbooisdrift, and back again to settle at Otjitambi near Kamanjab in the late 1870s.117 It is in the 1880s that reportedly ‘groups led by Petrus and Abraham Zwartbooi carried out numerous raids from the Brandberg and Otjitambi against Herero in north-western Hereroland and the Kaokoveld as far as the Kunene’: in ‘an attempt to compensate for poverty, loss of power and loss of autonomy’ in a context of expansionary ovaHerero and their cattle-herds.118

Simultaneously, this was a moment when an escalating dynamic of “Herero-Nama” raiding across complex and dynamic alliances broke out.119 In the second week of August 1880, a Nama cow reportedly went missing from Gurumanus [ǁGurumâ!nâs] water-hole, west of Rehoboth, where ovaHerero and Nama cattle-posts were situated; leading to ovaHerero beating a Nama they suspected of stealing, and precipitating an armed clash in which ‘Namas got the upper hand, killed most of the cattle-herders and abscond[ed] with nearly 1,500 head of [ancestral holy] Herero cattle’.120 On hearing this news in Okahandja on 24 August, Kamaherero reportedly ‘gave instructions that all the Namas in Damaraland were to be killed in revenge’: 20 were allegedly killed that night in the Nama village at Okahandja; a few days later ‘an estimated 200 Namas had been killed by the Hereros’.121 A heavy struggle followed between Jan Jonker—fleeing Windhoek for Rehoboth—and ovaHerero in the Auas mountains, with Windhoek attacked by ovaHerero, partially destroying the mission station including the home of Rev. Schröder.122

These and other events precipitated withdrawal of the Cape Government from the “Transgariep” (i.e. the territory north of the Orange River or !Garib) and an intensification of conflict in the region. Swartboois at !Am-eib made attacks on Otjimbingwe, being joined by Topnaars at Rooibank under Piet Haibeb, and making the mobility of incoming traders very unsafe.123 In 1880 Kamaherero reported to Palgrave that ‘Kaoko Damaras’ (ovaHerero) have killed ‘some [of] Zwartbooi’s people’ in the vicinity of Sesfontein;124 in 1883 Swartboois reportedly attacked a number of Herero cattle-posts;125 and missionary Riechmann, based at Fransfontein from 1891, reports raids from Otjitambi in the 1880s to Owambo in the north and ovaHerero in the south.126 Damara/ǂNūkhoen in west Namibia also suffered in these troubled times. Hundreds are reported to have fled to Omaruru from 1879 due to starvation following drought-induced death of their cattle,127 and at times multiple Damara/ǂNūkhoen were reportedly killed by ovaHerero.128 These losses surely played a role in their submission to recruitment as indentured labourers to households and farms in the Cape Colony from 1879 into the 1880s.129

This is the context in which Jan Petrus |Unuweb |Uixamab of the !Gomen/Walvis Bay Topnaar became established as “kaptein” in Sesfontein, having succeeded his brother Hendrik Anibab |Uixamab, successor to his father |Uixab who died in the south before they moved northwards.130 Jan |Uixamab’s arrival in Sesfontein attracted ‘people from the surrounding areas, as the emerging settlement offered new economic opportunities’, causing a centralisation of people in Sesfontein.131 ‘Intensification of agricultural production’ (including of tobacco), accumulation of livestock, and the appropriation of water and grazing resources generated employment in herding and in newly established gardens; and ‘[y]oung men were enrolled into commandos, with which they engaged in raids and hunting trips and supervised herds’.132 Integration was combined with territorial expansion, through ‘intermarriage and participation in the stock economy through loans and the inheritance of cattle’, as well as through herding at stock-posts in the broader landscape.133 Rizzo reports from interviews with Herero associated with Sesfontein that forced coercion is rarely mentioned, although she also argues that Oorlam organisation of the Sesfontein economy involved ‘enforced patronage and loyalties’.134

In the 1880s and into the 1890s the Nama population in Sesfontein expanded to close to 500 including dependents (as estimated by missionary Riechmann, based in Fransfontein), a pattern mirrored in Warmquelle and Otjitambi: thriving garden economies established in Sesfontein and Fransfontein complemented Nama herd concentrations in these areas.135 Plaits of tobacco (called !nora) were used to barter for small stock and sometimes cattle;136 aromatic sâi plants were collected by Damara/ǂNūkhoen in especially the Sirib mountains west of Sesfontein (Figure 1.8) for trade elsewhere; and Damara/ǂNūkhoen were recruited to collect ǂao-haib (Caroxylon sp. formerly Salsola) to make soap for washing the fabric clothes worn by the Nama (Figure 1.9). Franz |Haen ǁHoëb of Sesfontein provides a flavour of these circumstances:

in the past people used to cook with this plant (ǂao) to make soap for washing […] they burnt the plant and took the ash to mix with cow fat, and they cook it and when it is ready for cutting they put it out, and when it is cool then they cut it with the knife into pieces and use this soap for washing the clothes. […] In the past it was only Nama people who have the material clothes that need washing. ǂNūkhoen just help, and learn from the Namas how to make the soap. They carried the wood [of ǂao] and they bring this wood and they cook that soap for the Namas. And the Nama people gave them food for this work. At that time ǂNūkhoen were only wearing skins which do not need washing with soap.137

Fig. 1.8 Sirib mountains west of Sesfontein/!Nani|aus, where aromatic plants were once gathered for sâi (perfume). Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 21.11.2015, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Fig. 1.9 ǂAo-haib (Caroxylon sp., formerly Salsola) in the Hoanib River west of Sesfontein, formerly used to make soap for clothes washing. Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 21.11.2015, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

It might be argued that accounts of historical Nama viciousness and ovaHerero victimisation in the Kaokoveld start with two biases that linger in contemporary conservation engagements in Kunene. The first is a perspective of ovaHerero historical presence and Nama/Khoekhoegowab absence in the north-west, permitting the singular narrative outlined above of Herero displacement by incoming Nama ‘hordes’.138 A number of sources, however, indicate the presence of Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples in north-western parts of Namibia prior to the mid-1800s, their lasting legacy being the numerous Khoekhoegowab names for rivers and springs throughout the region: Hoanib, Hoarusib, Gomadom, Sechomib, Khumib, !Uniab, ǁHuab and !Uǂgab for the westward flowing ephemeral rivers whose dense vegetation and subsurface water offer lifelines in this arid landscape; and Puros, Auses, Dumita, Ganias, Sarusa and Kai-as for places where springs made it possible for people to live and access important food and forage plants in this dryland area.139 Indeed, wide-diameter (around 4 m) circles of hut anchor stones with a central fireplace and room divider have been found near the !Uniab river mouth (now within the Skeleton Coast National Park, SCNP) and dated to ca. 1,000-1,300; these are consistent with Nama/Khoe reed-mat hut construction140 (as discussed in Chapter 12). Review of sources and oral history research also indicates the historical presence of Khoekhoegowab-speaking ǂNūkhoen as well as Haiǁom in many localities in Etosha-Kunene, contributing to the presence of Khoekhoegowab names throughout the area.141

The second connected bias is an almost complete absenting of Damara/ǂNūkhoen and ǁUbun histories in Etosha-Kunene, despite the presence of these peoples, sometimes in large numbers, as indicated in many historical sources.142 Some academic analyses of “the Kaokoveld” seem to downplay the histories and perspectives of Khoekhoegowab-speakers.143 As an example, Bollig and Heinemann-Bollig write that,

ephemeral rivers of the western Kaokoveld have Damara names (Hoanib, Hoarusib, Huab, Khumib), despite the fact that mainly Himba or Tjimba settled along them (perhaps with the exception of the Huab [ǁHuab]). [Georg] Hartmann already used these river names. Since there was no Damara population settled along these rivers at the time, it is possible that the travellers’ Damara servants had entered these names in the travelogues. 144

The Georg Hartmann mentioned here was a key actor in the circumstances of north-west Namibia under German colonisation, as considered in more detail in Section 1.3.1. He may indeed have deployed ‘Damara servants’ on his expeditions from Otavi to the Kaokoveld in the 1890s, but archival sources show that he definitely relied heavily on the knowledge of ‘Swartbooi Nama’ who guided him through this remote area and shared with him the known names of rivers and places in the region. For example, in a report by Hartmann to the colonial administration, which was building up to a suppression of the resistance by diverse Indigenous Africans in the so-called Swartbooi/Grootberg Uprising of 1897–1898 (see Section 1.3.2), it is a Johannes Swartbooi, based in the areas of Otjitambi and Fransfontein, who is named as a lead guide for Hartmann’s Kaokoveld expeditions.145 Multiple other sources document the presence of Khoekhoegowab-speakers in these areas of the north-west in the late 1800s, as reviewed in Chapters 12 and 13.

Indeed, historical and oral history sources indicate that a southwards movement of Nama pastoralists prior to the so-called “ovaKuena wars” of the late 1800s was itself precipitated by ovaHerero south-eastwards migration into central Namibia in around the late 1700s, reportedly stimulated by poor rains in Kaoko.146 This expansion impacted Nama and Damara/ǂNūkhoen residing in these areas, cutting off ‘[t]he more northerly Toppners [ǂAonin] […] from all communication with those about Walfisch Bay’.147 Thus, ‘[a]t the beginning of the 19th century the Topnaar are said to have reached the mouth of the Swakop (tsoa-xou-b)’, their migration perhaps ‘related to the advance of the Herero into the Kaokoveld’:148 accounts that iterate similar observations by Captain James Edward Alexander in 1837,149 and anthropologist Winifred Hoernlé in the early 1900s:150 discussed further in Chapter 12.

The erasure and delegitimising of the histories of Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples in some analyses of Namibia’s north-west contribute to contemporary marginalisation of Khoekhoegowab-speakers in Etosha-Kunene. It is arguably a reason why their concerns in relation to current conservation and land designations remain poorly understood or engaged with (see Chapters 3, 12 and 13).151 In sum, German colonisation enters the scene at a time of immense fluidity and change in Etosha-Kunene, the implications of which reverberate into the present.