2. Spatial severance and nature conservation: Apartheid histories in Etosha-Kunene

©2024 S. Sullivan, U. Dieckmann & S. Lendelvo, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.02

Abstract

We review conservation policy and legislation and its impacts under the territory’s post-World War 1 administration from Pretoria, prior to the formalisation of an Independent Namibia in 1990. We trace the history of nature conservation in Etosha-Kunene during the times of South African government. In the initial phase “game preservation” was not high on the agenda of the South African administration, which focused instead on white settlement of the territory, requiring a continuous re-organisation of space. After World War 2, the potential of tourism and the role of “nature conservation” for the economy was given more attention. Fortress conservation was the dominant paradigm, leading to the removal of local inhabitants from their land. Shifting boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2 characterised the 1950s up to the 1970s: part of Game Reserve No.2 became Etosha Game Park in 1958 and finally Etosha National Park in 1967, which in its current size was completely fenced in 1973. The arid area along the coast was proclaimed the Skeleton Coast National Park in 1971. Alongside these changes, new allocations of land following the ideal of apartheid or “separate development” were made, “perfecting” spatial-functional organisation with neat boundaries between “Homelands” for local inhabitants, the (white) settlement area and game/nature. Land, flora and fauna, and people of various backgrounds were treated as separable categories to be sorted and arranged according to colonial needs and visions. A new impetus towards participatory approaches to conservation began to be initiated in north-west Namibia in the 1980s, prefiguring Namibia’s post-Independence move towards community-based conservation.

2.1 Introduction

As outlined in Chapter 1, in 1907 the German colonial administration proclaimed a large area of north-west Namibia, which we are calling “Etosha-Kunene”, as one of three Game Reserves in German South-West Africa. This area was by no means an “untamed wilderness” but rather inhabited by Indigenous groups speaking different languages, with a diversity of animal and plant species, waters, soils, and so forth. The proclamation of Game Reserve No. 2 can be seen as the beginning of a long and varied history of colonial nature conservation in Etosha-Kunene with shifting objectives, policies and practices that had tremendous influence on its human and beyond-human inhabitants.

In this chapter, we trace the history of nature conservation in Etosha-Kunene during the post-World War 1 South African administration of “South West Africa” (SWA), formally from 1920–1990. In the initial phase (Section 2.2), nature conservation was not high on the agenda of the South West African Administration (SWAA). The focus changed gradually from the 1950s when white settlement of the territory had almost reached its limits, and nature conservation and its potential for tourism and for the economy were given more attention (Section 2.3). During the 1960s, the appointment of the Commission of Enquiry into South-West Africa Affairs (called the Odendaal Commission after its Chairman Frans Hendrik “Fox” Odendaal) changed the direction to some extent (Section 2.4). The Odendaal Plan entailed perfecting spatial-functional organisation with neat boundaries between “homelands” for the various local inhabitants, the (white) settlement area and “game”/nature. This re-organisation of space and its partly unforeseen effects necessitated more “nature management” and “game farming”, and led to increasing economic dependency, especially of those who were not allocated a “homeland” (e.g. Haiǁom). “Kaokolanders” (ovaHimba, ovaHerero, ovaTjimba, Dhimba, and others1) and oshiWambo-speakers retained access to former “Reserve-lands” (which were expanded in the case of “Kaokoland”). The new “homeland” of Damaraland (re)connected several former “Native Reserves” (Okombahe, Otjohorongo, Fransfontein, Sesfontein) inhabited by Damara/ǂNūkhoen, ovaHerero and Nama. All were subjected to heavy restrictions on mobility and property ownership.

Chapters 1 and 2 thereby provide an outline of colonial histories and legacies, the re-organisation of spaces, and the reshuffling of human and non-human inhabitants in Etosha-Kunene, comprising the conservation legacy Namibia faced after Independence in 1990, as considered in Chapter 3.

2.2 1915 until the 1940s: The initial phase of South African administration—spatial organisation, settlement and

game preservation

2.2.1 Spatial organisation: The red line, “native reserves”

and settlement

German administration in SWA was terminated during World War 1 by the peace treaty of Khorab in 1915, when South Africa imposed martial law on the former German colony.2 The German Proclamation of 1907 regarding game reserves was repealed by Ordinance 1 of 1916, which amended and reconfirmed the borders of Game Reserve No. 2.3 Alongside this ordinance, Proclamation 15 of 1916 decreed that no person can ‘cross the line marking the Police Zone [i.e. the southern and central parts of the territory under formal colonial government] without permission’.4

After the German surrender in 1915, a large number of people classified as ovaHimba, ovaHerero, ovaTjimba and Nama under the leadership of Vita Thom and Muhona Katiti (see Chapter 1) returned with their cattle from southern Angola to the Kaoko area,5 causing disruption and the dislocation of local communities. Subsequently, Major Charles N. Manning, the first Resident Commissioner of Ovamboland, undertook two administrative journeys into north-west Namibia in 1917 and 1919, continuing the pre-existing German impetus of government and control based on a typical suite of statecraft technologies. These included: reducing the availability of firearms;6 controlling the hunting of game; demarcating ethnic groups and identifying political leaders associated with them;7 and controlling movement and trade.8 Part of his mission was to disarm inhabitants of the area and to make ‘it clear that local hunting and trading in game products were to be unacceptable’.9

In 1920, South Africa was granted a League of Nations Mandate to administer South-West Africa, providing a safer foundation for the administration’s future policy. The administration was now less dependent on international opinion and could follow its actual colonial interests and the requirements of a settler economy. With the change of government, the Kaoko Land and Mining Company (Kaoko Land und Minengesellschaft, KLMG, see Chapter 1) was formally nullified:10 ‘[o]nly four farms had been surveyed and sold and they were never occupied’.11

The border of the Police Zone became clearly defined in the Prohibited Areas Proclamation 26 of 1928. Established under German colonial rule initially as a cordon of military-veterinary stations to control human and livestock mobilities following the rinderpest epidemic of 1897 (Chapter 1), by 1907 it was represented as blue line on a map,12 becoming a red line drawn on maps of the South West Africa Administration (SWAA).13 Henceforth, the Police Zone border became known as the Red Line which,

physically mark[ed] the transition between “white” European southern Africa and the “black” interior, between that which was “healthy” and that deemed “diseased” […] the line drawn between what the colonial power defined as “civilization” and what it considered “the wilderness”.14

The Red Line was ‘reinforced by a chain of police outposts placed at intervals along its length’.15 For Kaokoveld in the north-west, regulations were administered from Ondangwa and ‘enforced by numerous police patrols into the area’.16 The Red Line functioned increasingly as a veterinary border,17 not only separating settlers from “natives”, but also aimed at keeping livestock populations on both sides apart from each other.

In addition to the Red Line from east to west, other measures for the spatial segregation of inhabitants were established. A Native Reserves Commission (the body responsible for developing segregation as policy) was set up in 1920, recommending that:

(i) the country should be more clearly segregated into black and white settlement areas; (ii) squatting on white farms should be prevented; (iii) there should be more efficient control of the reserves; (iv) reserves which were recognized by German treaties should be maintained but the temporary reserves established during the military period should be closed; (v) new reserves (which did not disturb “vested rights”) should be established; and (vi) further land should be earmarked for further extension of these reserves.18

A few “native reserves” had been established by the German administration, but the number was now extended with reserves set up in most of the settler farming districts. In Etosha-Kunene, the German “native reserves” of Sesfontein and Fransfontein were retained, with some farms north and north-west of Outjo serving as reserves in the 1920s and early 1930s. The farm Aimab, for example, was used as an “Ovambo reserve” until the 1920s,19 and Otjeru, originally including several farms, was also an Ovambo reserve from German times until the late 1930s.20 In the 1930s, these reserves were dissolved21 and their inhabitants had to move to Fransfontein, native reserves in other districts, or outside the Police Zone, unless they took up regular employment.22 In 1923, three native reserves were established in Game Reserve No. 2, in the north-east of Kaokoveld near the Kunene River, with different ‘chiefs of Kaokoland’s pastoral population’: namely (from west to east) Kakurukouye, Vita Thom and Muhona Katiti.23 The Native Reserves Commission also defined the conditions for movement between native reserves, farms and urban areas. The reserves provided a necessary source of labour for settlers. Bushmen were not assigned any land, because the Native Reserves Commission considered ‘that “the Bushmen problem [...] must be left to solve itself”, and “any Bushmen found within the area occupied by Europeans should be amenable to all the laws”’.24

The native reserve policy south of the Red Line was closely connected to the settlement policy. Since the early 1920s, South Africa was interested in relocating poor white South African citizens to its new colony, and therefore set up a settlement programme offering extraordinarily favourable conditions: munificent provisions for loans, low minimal capital requirements and help with transportation into the area.25 New laws to regulate the flow of labour and control the Indigenous population were imported from South Africa.26 The Masters and Servants Proclamation (no. 2 of 1916 and amendments) aimed at the ‘systematization, formalization and centralization of labour relations’,27 and the Vagrancy Proclamation (25 of 1920 and amendments) made it an offence for black people to move around in the Police Zone, unless they could show ‘visible lawful means of support’, set at either 10 cattle or 50 small stock.28

At the end of the 1920s, about 1,900 Afrikaners who had earlier trekked from South Africa to Angola (see Chapter 1), were offered the possibility to move to South West Africa. The majority were first resettled in the so-called Osire Block, east of Otjiwarongo, but in 1937 many of them moved to the Gurugas Block in the north-west of Outjo District (now in Kunene Region),29 where farming conditions were better.30 This resettlement happened despite the fact that in the mid-1930s, the Land Settlement Commission had to admit that the generous settlement policy, initiated in 1920 and offering extensive aid to the farmers, was largely responsible for the unsound position in which the farmers often found themselves, as they had often overcapitalised their operations and lived beyond their means. Therefore, from 1935 onwards, farms were usually allocated for a period of one year without financial support, the capability of a farmer to manage the land during the first year being decisive for prospective tenure.31

The Annual Report on Land Resettlement of 1937 stated that:

[t]he rate of progress of land settlement at present cannot be maintained much longer, as most of the land suitable for settlement purposes has been disposed of. There are un-surveyed areas in the Outjo, Swakopmund, Maltahöhe and Warmbad districts which it is proposed to cut up into farms during the course of this year, and these holdings will be made available for settlement purposes. When these have been disposed of there will remain very little land for further settlement.32

Despite the concerns stated in the report, more land was made available until the early 1960s in the Outjo and Grootfontein districts through shifting the police zone and Game Reserve No. 2 boundaries and de-proclaiming Game Reserve No. 1 (see Section 2.3.2):33 the north-westerly extension of the settler farming area is reviewed in Chapter 13.

Increasing settlement had severe consequences for local inhabitants in Etosha-Kunene, both north and south of the Red Line. Many were driven from their land south of the Red Line in order to make space for white settlement.34 At the end of the 1920s, for example, a major portion of southern ‘Kaokoland’ Herero were forcibly removed from an area around Okavao situated today within Etosha National Park (ENP), north-westwards to Ombombo in the south-eastern part of Kaokoveld,35 so as to make the Police Zone border impenetrable for people and livestock:36 see

Chapter 14. In total, 1,201 people were removed, together with 7,289 cattle and 22,176 sheep and goats.37 In the SWA Annual Report of 1930 it was thus reported that,

[c]hanges in regard to the settlements of natives have recently been carried out in the Southern Kaokoveld. Scattered and isolated native families, particularly [but not only] Hereros, have been moved to places where it is possible to keep them under observation and control. With few exceptions, these natives are well satisfied with the new localities. They also realize the advantage of being controlled by one chief. […] All stock has been moved north over a considerable area in order to establish a buffer zone between the natives in the Kaokoveld and the occupied parts of the Territory which remain free of the disease [lungsickness].38

Strict boundary controls in the north-west protected the commercial farming areas, such that any move into the Kaokoveld required ‘a pass from the local administration’ and ‘Kaokolanders’ had to apply for passes to the police post at Swartbooisdrift/Tjimuhaka on the Kunene River: these applications were sent on for approval ‘to the office of the Native Commissioner at Ondangwa’, with movement of livestock across international and internal boundaries prohibited.39

Further east, in the Outjo and Grootfontein area, the so-called “Bushmen problem” that began under the German colonial regime (see Chapter 1) continued to trouble the administration: a number of proclamations were either newly enacted or amended to better handle the problem. Proclamation 11 of 1927 sought to prevent squatting by limiting the number of people allowed to reside on a farm to five ‘native families’.40 The Vagrancy Proclamation (32 of 1927) was also amended,41 and prison terms for vagrancy were inter alia increased from three to 12 months. The Arms and Ammunition Proclamation was revised to include Bushman bows and arrows under the definition of firearms, making their possession henceforth illegal (by Government Notice 2 of 1928); yet this proclamation seemed to lack the necessary precision for extensive implementation. No fees for licences were ever fixed, nor did Bushmen ever bother to apply for licences.42 During the 1930s and 1940s, discussions about where to resettle the Bushmen took place with different suggestions of “Bushman reserves”. One suggestion was of a “Bushman reserve” overlapping Game Reserve No. 2, with the Assistant Secretary of the Administration suggesting the establishment of a reserve for Bushmen should go hand in hand with maintenance of the Game Reserve, and that Bushmen should have access to game. It was thought that if Bushmen were allowed to roam and hunt over portions of the Game Reserve, it might provide a solution to the “problem” of the Bushmen’s nomadic lifestyle,43 although in 1941 this initiative was dropped.

Yet, the idea of keeping “natives” and settlers in separate areas was not only impeded by the mobility of local inhabitants with or without livestock, but also due to the grazing needs of settler farmers with their livestock, especially during periods of drought. In the 1930s, the South African Administration contemplated settling white farmers in the “neutral zone” north of the Police Zone border,44 from which local inhabitants had been progressively cleared since the early days of establishing a militarised veterinary cordon during the rinderpest epidemic of 1897 (see

Chapter 1). In the early 1940s, the administration started awarding grazing licences north of the Red Line for which farmers could apply (see Chapter 13).45 Farmers were not only dependent on sufficient grazing but also on cheap farm labourers. Ovambo and other migrant workers coming from the north strongly rejected farm labour due to poor wages, rations and bad treatment as well as the need to split up into smaller groups. They were therefore mostly channelled to mines, railway construction and the Works Department, at least prior to the depression in the early 1930s.46 Bushmen and Damara/ǂNūkhoen living in the settlement area had to fill the farm worker gap.

2.2.2 Nature conservation and Game Reserve No. 2

As can be seen, the settlement programme was the focus of the South African administration up to the 1950s, with nature conservation playing a relatively minor role.47 Joubert comments on the years from 1915–1947 that,

virtually no progress was made regarding conservation as a whole. Various Ordinances were proclaimed but enforcement in the vast area of SWA was virtually impossible, especially since no officials directly responsible for nature conservation existed.48

Nature conservation during this period mainly implied “game preservation” and was embedded in the whole colonial enterprise, meaning that the history of nature conservation needs to be read in conjunction with these other measures of spatial-political organisation. Sometimes interests related to nature conservation had to be negotiated with other branches of colonial administration due to contradicting objectives; sometimes interests went in the same direction and initiatives taken were mutually dependent.

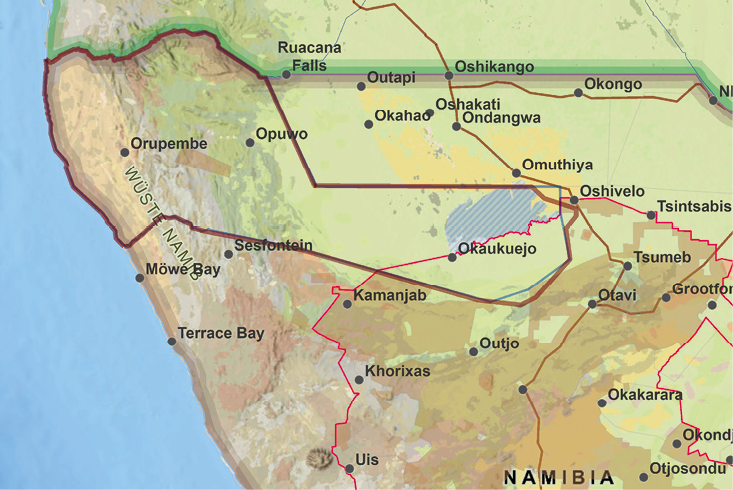

In 1921, the Union’s first Game Preservation Proclamation (13 of 1921) for South West Africa was issued, based on the legislation of the original German administration of 1902.49 This Proclamation made the South African police responsible for regulating hunting and game protection,50 as had also been the case in the German colonial period (see Chapter 1).51 The proclamation was repealed and replaced in 1926 by Game Preservation Ordinance (5 of 1926).52 The list of protected game species was extended,53 hunting on crown land ‘with exception of dignitaries and officials on duty in rural areas’ became prohibited, and hunting restrictions on settler farms were applied.54 In 1928, the Prohibited Areas Proclamation mentioned above re-proclaimed Game Reserves Nos. 1, 2 and 3 and defined their borders.55 The post of Game Ranger of Game Reserve No. 2, up to that date assumed by a Captain Nelson, was abolished and the Native Commissioner of Ovamboland, Carl Hugo Linsingen (“Cocky”) Hahn (son of the Rev. Carl Hugo Hahn mentioned in Chapter 1), took over and acted as a part-time Game Warden.56 Through border changes of Game Reserve No. 2, 47 farms in the south-east of Etosha were either created or existing farms cut out of the game reserve (see Figure 2.1).57 Only in 1935 was private farm ownership within the boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2 finally terminated (with one exception—a small piece of land close to Okaukuejo).58

Fig. 2.1 Map of the Game Reserve No. 2 boundary in 1907 (brown border) and 1928 (blue border), with the police zone border of 1937 (red), freehold farmland in this year (shaded in brown) and main roads (brown lines). © Ute Dieckmann, data: Proclamations NAN, Atlas of Namibia Team 2022, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Although the focus in the context of nature conservation during these years was mainly on wildlife, in 1937 the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (19 of 1937) was gazetted, including for the first time the protection of plants (other than Welwitschia mirabilis, which had been protected since 1916).59 Combining flora and fauna, this legislation implied that the administration had started to move towards a more holistic approach of “nature conservation” embedded in global discourses.60 World War 2, however, stopped any further developments in this regard for almost a decade.

The south-eastern area of Game Reserve No. 2, where Haiǁom continued to be accepted as inhabitants, was called Namutoni Game Reserve, Etosha Game Reserve or Etosha Pan Game Reserve in the 1920s until to the 1940s: according to Miescher the name was streamlined to Etosha Pan Game Reserve in 1948.61 Officers from the respective police stations reported on this area in their monthly reports. In the 1920s, around 1,500 Haiǁom were estimated to be living around Etosha Pan.62 At the time, the boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2 were not marked well, let alone fenced. In these years, a number of Haiǁom from Etosha Game Reserve were employed in the Bobas mine near Tsumeb, or as seasonal workers on farms.63

Some problems with regard to the frontier situation and the control of mobility had already been noticed in the early years of the South African administration. For example, the game warden of Namutoni remarked in 1924:

[s]tock thefts on the border of the Reserve and Outjo district have been going on for some years. Bushmen residing for a certain period of the year in the district of Outjo cross over to the Reserve for a time, they are all over the country, even entering the Kaokoveld.64

Hunting by Haiǁom within Etosha Game Reserve was generally not regarded as a problem, as indicated in game warden reports in 1926: ‘[t]he amount of game shot by Bushmen is by no means decreasing the game’.65 Certain limitations were officially in place: no firearms, no dogs, no shooting of giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis), eland (Taurotragus oryx), impala (Aepyceros melampus) and ‘loeffelhund’ (bat-eared fox, Otocyon megalotis),66 although hunting with rifles occasionally took place.67 Haiǁom in the reserve were also in possession of livestock but there was uncertainty among the officers about how much livestock was allowed: it was decided then that “Bushmen” should not keep more than 10 head of large and 50 head of small stock per person within the reserve.68 In October 1937 the monthly return of Namutoni reported 84 cattle, eight donkeys (excluding 40 donkeys of an Ovambo man at Osohama) and 92 goats in the vicinity of Namutoni, with two men reported to have 20 and 23 head of cattle, exceeding the allowed number of 10 head of large stock per person.69 In 1939, the number of livestock of Haiǁom at only three waterholes in the vicinity of Namutoni, within the game reserve, was reported to be 98 cattle, four donkeys, and 204 goats. The Station Commander asked the men to reduce their stock, which reportedly took place afterwards.70

The separation of game from livestock had evidently not yet taken place. The Red Line ran along the southern edge of the pan, while the southern border of the game reserve—marking also the northern border of settlement—was situated further south. Haiǁom were partly integrated into the colonial system and in general not regarded as “proper Bushmen”. Lebzelter observed in the 1920s:

[t]hese people usually dress in European rags, use Christian names without actually being proselytised, but are always ready to dance for distinguished guests in their traditional clothes and have their picture taken. They are well on the way to becoming saloon bushmen and are gradually getting into the tourist business […]71

Ironically though, they were portrayed as ‘the African Bushmen’ and ‘the most primitive race on earth’ by the Denver African Expedition,72 which visited the Etosha area from September 1925 until January 1926. The expedition’s members claimed to have discovered ‘the missing link’ in the Haiǁom residing there, making a film called ‘The Bushman’ and taking around 500 still photos.73

Indeed, the number of Haiǁom living in Etosha Game Reserve in the years before World War 2 is not clear. The monthly and annual reports were written by people responsible for different areas (e.g. Namutoni or Okaukuejo), which also included land outside the Game Reserve. Additionally, the accounts given are based entirely on estimates, since the officers were lacking detailed knowledge of Haiǁom living in their areas.74 The only ‘complete’ accounts for the Game Reserve were given in Hahn’s annual reports. In 1942, for example, he estimated around 605–770 ‘Bushmen’ to be living in Etosha Game Reserve.75

Beyond the area of Haiǁom habitation, in these years thousands of “Kaoko pastoralists”, as well as Khoekhoegowab-speaking Puros Dama, !Narenin, ǁUbun and Nama, were also living within and moving through the Kaokoveld part of Game Reserve No. 2 (see Chapters 6, 12, 13 and 14). In the late 1930s to 1940s, Africans including ‘BergDama’ (Damara/ǂNūkhoen) were repeatedly and forcibly moved out of the western areas between Hoanib and Ugab Rivers,76 although inability to police this remote area meant that people moved back as soon as the police presence left:77 see Chapters 12 and 13. OvaHerero connections with landscapes to the west of Etosha Pan were also disrupted (see Chapter 14).78 Correspondence in 1928 by Hahn to the administrator of SWA provides some indication of Hahn’s thinking regarding the connections between local inhabitants, and conservation and tourism visions for Kaokoveld. Predating by some five decades proposals in the 1980–1990s for local people and ex-‘poachers’ to become ‘Community Game Guards’ (see Chapter 3), Hahn travelled in this year to the Kunene River in the vicinity of Ruacana Falls, designating ‘the old and experienced Ovahimba hunter headman Ikandwa as an informal warden’ to support ‘the replenishment of game’.79 Historian Patricia Hayes writes that Hahn:

wanted to transform the area into a sanctuary, which would offer “fine opportunities for tourists and sportsmen to shoot trophies under special licences and instructions”. This tied in with wider objectives of policing cattle movements in the area and an attempt to stabilise groups in reserves in northern Kaokoland to act as a buffer with Angola. Hahn argued that the administration should proclaim it a reserve and protected area, and run it on similar lines to the Kruger National Park. It was capable of surpassing the best game reserve in South Africa [Kruger] and creating “a real tourists’ paradise in SW [i.e. South West Africa]”. Game was disappearing elsewhere except in the Namutoni Reserve (Etosha), but “the flat and almost colourless country is not in any way to be compared with the wonderful variety and grandeur all along the Kunene”.80

The idea to develop Game Reserve No. 2 or parts thereof along the model of the Kruger National Park had thus already started during the early phase of the South African Administration. In the 1930s, when tourism began to increase in the area around Etosha Pan, the idea was iterated for the Etosha Game Reserve. Hahn reported for the tourist season of 1937 that around 500 visitors had visited Okaukuejo:

[t]hese people [visitors] arrive there dusty and thirsty and there being no facilities for them to camp, they simply squat on his [the police sergeant stationed there] doorstep, with the result that out of sheer humanity he had to offer them a cup of coffee or tea, and some even ask for it. […] As there is such a tremendous increase of visitors annually, I consider the time has come for the Administration to consider suitable camping provisions at this place […] It is evident from the number of Union and foreign visitors visiting the pan, that its existence is becoming more and more known, and people who have visited the Kruger Park expect to find the same facilities here as exist there, consequently there is great disappointment when they come here.81

World War 2, however, put the realisation of any further development of the Game Reserve on hold.

2.2.3 Post-World War 2: Change of policy, reserves and settlement

After the war, extensive provision was made for the support of war veterans. Ex-soldiers were given land and could qualify for additional loans for such things as building houses and to purchase breeding stock. Part of Etosha Game Reserve was cut off and made available for settlement and the Police Zone border was shifted82 in order to provide more farmland for white settlers; boreholes were drilled and grazing licences could be obtained by interested settlers. A large amount of land in the western part of Outjo district—formerly one huge farm of 247,346 ha—was made accessible to settlers. Aruchab, as the farm was called, had been allotted to the Imperial Cold Storage and Supply Company in 1924, which used it for cattle. In the second half of the 1940s, the farm land was surveyed and divided into about 40 farms, most of them allotted immediately afterwards.83 Apart from the World War 2 ex-soldiers, settlers from the southern regions of Namibia moved to the district since the south had suffered from enduring drought.84 Settlement and game conservation were at times in conflict. For instance, and in stark contrast to later policies, the Chairperson of the Game Preservation Commission reportedly responded to a request that game on white farms be declared the owner’s property that this was ‘preposterous’, and that the mostly Afrikaner farmers ‘would simply destroy game’.85

Policy and practice regarding Game Reserve No. 2 also changed noticeably, probably due to reasons that included: the take-over by the National Party in South Africa and its policy of apartheid; an increasing interest in tourism; and a broader approach to nature conservation including the role of national parks. South African historian William Beinart notes that the concept of a National Park changed in the southern African context after World War 2, to increasingly denote land set aside for animals and plants and free of human habitation:

[i]nitially, the settler concept of a national park could allow for continued occupation by picturesque “native” people. But particularly after the Second World War, […] a national park came to mean a preserve for plants and animals free of human habitation. […] most of the people were removed and the park became a preserve for rangers, scientists and mostly white visitors.86

This concept also found its way to Namibia but was not yet implemented in Etosha-Kunene, where thinking about how to deal with human inhabitants and protected areas remained ambiguous.

In 1947, Kaokoveld was proclaimed a native reserve (the Kaokoland Reserve) (expanding the three reserves in the north of the territory established with separate headmen in 1923—see Section 2.2.1), but remained part of Game Reserve No. 2 for the time being.87 From this time onwards, Kaokoveld was administered from Opuwo (Ohopoho). Developments regarding tourism centred for the next decades on the area around Etosha Pan. In the same year, Andries A. Pienaar, an author of adventure stories set in the wild (known as Sangiro), was appointed as the first full-time additional Game Warden for South West Africa (additional to his role as the Secretary of State). He was supposed to write a book in order to promote the wildlife of the territory.88 Stationed in Otjiwarongo, he was in charge of Game Reserve No. 2 which previously had been managed by the Native Commissioner of Ovamboland.89

In 1948, and in a context in which Kruger National Park in South Africa had reached saturation point during peak tourism periods, a National Publicity Conference adopted a resolution for the ‘developments of smaller National Parks’, in which the conference urged the National Parks Boards, the SWAA, the Natal Provincial Administration, the Union Government Forest Department and the Orange Free State Provincial Administration:

to develop national parks (other than the Kruger National Park and the Hluhluwe Game Reserve, which are reasonably developed) so that they may be made accessible to tourists and thereby increase their knowledge and love of wild life.90

Soon afterwards in 1949, an article on the ‘Etosha Pan Game Reserve’, prepared by an officer of the SWAA for a publisher in Johannesburg, stated:

[p]erhaps one should also mention the Bushmen, although nowadays they are no longer classed as “game”! They certainly fit into the picture and help to give to the Etosha Pan something of the atmosphere of the old wild Africa that is fast disappearing everywhere [...]91

This idea to promote the ‘Bushmen’ in Etosha as the ‘old wild Africa’, however, was not pursued further.92

Also in 1949, a Commission for the Preservation of Bushmen was appointed to ‘go into the question of the preservation of Bushmen in South West Africa thoroughly and to recommend what action the Administration should take in the matter’.93 This commission was not directly linked to nature conservation or the Etosha Game Reserve but rather more generally to ‘Bushmen’ control and spatial segregation. Its impact on Haiǁom was tremendous. P.J. Schoeman, who later became Game Warden of SWA, was a member (see Section 2.3.1): his ideas and involvement were crucial for developments to come.94 The establishment of the commission was motivated in the following way:

[w]hat the Administration wanted was to create conditions where the Bushmen would be able to lead their ordinary lives with a sufficiency of the necessities of life available for them, and where they would be given every opportunity to preserve their separate identity and thereafter to work out their own destiny with the sympathetic help of the Administration.95

Moreover, the commission was asked to make ‘a survey of vagrant Bushmen in the Police Zone and to make recommendations for placing them in Reserves’.96 The proposal of a ‘Bushman reserve’, already discussed in the 1930s,97 was on the agenda again, but now against the background of the apartheid system in South Africa. In their preliminary report, the commission again suggested a ‘Bushman reserve’ overlapping the Etosha Game Reserve, proposing a location south of ‘Ovamboland’, including the Etosha Pan and to its west: areas not regularly used by Haiǁom due to the lack of permanent water.98

The investigations during two journeys of the commission led to the following description of Haiǁom given in the report under the heading ‘Who are the Bushmen’:

[a]t all the places where the Heikum Bushmen were questioned, they informed us that before even the Europeans came to the territory they had already intermarried with the Ovambos, Damaras and Hottentots [Nama]. All that has remained Bushman amongst them is their wonderful folklore, their mode of livelihood (game and veldkos), their bows and arrows and a few tribal customs, amongst others, burial ceremonies, feast of the first fruits and the initiation ceremonies for girls.99

The ideal underlying these considerations and conclusions was evidently that people must be neatly sortable into clear-cut categories: a concept that had already led early explorers and colonisers to try and impose conceptual order upon a foreign and confusing human world, as discussed in Chapter 1. For Haiǁom, it seems that an idea of purity counted against their “preservation”. Although the category “Bushmen” is now often construed as a ‘myth’,100 the message underlying the commission’s description above is self-evident. Haiǁom were not considered to be “prototypical Bushmen”, with the investigations concluding that it would not be worthwhile ‘to preserve either the Heikum or the Barrakwengwe [Khwe] as Bushmen’: ‘[i]n both cases the process of assimilation has proceeded too far’.101

2.3 1950s until 1969: The professionalisation of nature conservation, local inhabitants and shifting borders

The attention the administration placed on game, nature and the potential of both for tourism, increased gradually. By the 1950s, white settlement of the territory had almost reached its limits with environmental outcomes (for e.g. soil degradation in some contexts) becoming obvious,102 leading to game preservation/nature conservation being increasingly institutionalised and professionalised.103 During this period, the general concept of a Game Reserve was refined, implying certain limitations mainly regarding hunting. The concept of Game Parks (later also covering National Parks) was also legalised and implemented, and the question of human habitation within protected areas was re-considered. All these efforts continued to be entangled in diverging and changing ideas from various sides as to how to develop the territory. In this section we focus first on changes in direction towards “nature conservation” (Section 2.3.1), followed by an elaboration of legal boundary changes in Game Reserve No. 2 leading to the establishment of Etosha National Park in 1967, again with further boundary changes (Section 2.3.2).

2.3.1 The institutionalisation of game preservation/nature conservation and the (incomplete) severance of people from parks

In 1951, Ordinance 11 on Game Preservation was issued, providing for the establishment of a Game Preservation and Hunting Board to advise the SWA Administrator. The ordinance included the appointment of game wardens as honorary or public service officers,104 and involved regulation of hunting on freehold (white) farms including restrictions on the amount of game that could be taken, the length of the hunting season and penalties for infractions; although Article 27 allowed the administrator ‘to permit visiting dignitaries “to hunt any game in open season”’.105 It appears ‘that Africans were generally allowed to utilise wildlife resources in their communal areas’ until restrictions were imposed by this Ordinance.106

During the same year, hunter, writer and anthropologist P.J. Schoeman—a member of the Commission for the Preservation of Bushmen in South West Africa (see Section 2.2.3)—succeeded Pienaar (who had not managed to publish a book on wildlife), as Game Warden.107 In 1952, Schoeman employed the painter and artist Dieter Aschenborn as an assistant game warden, stationed in Okaukuejo.108 In 1953 he also appointed Bernabé de la Bat from the Cape, as a biologist to be stationed in Okaukuejo.109 One can regard this moment as the start of a “scientification” of conservation efforts in Namibia. Amy Schoeman writes about de la Bat:

[t]he history of formal conservation in Namibia revolves largely around one man, Bernabe de la Bat, who was appointed biologist and then chief game warden in Etosha in the early fifties. De la Bat orchestrated the birth of the country’s first official conservation body and served as its director until the 1980s. With remarkable vision, courage and foresights, he created a rich legacy of game parks, reserves and resorts on which conservationists could build in the years to come. He also laid the cornerstone for tourism in Namibia.110

Also in 1953, however, P.J. Schoeman reported that tourists expressed more and more concern that the game in Etosha had decreased and become wilder, partly due to adjacent farmers’ hunting activities, partly due to the increase in tourists, and partly due to dogs owned by Bushmen who were still allowed to live in the game reserve at this time.111

In 1954, Game Warden Schoeman provided the first Annual Report of the Division Game Preservation of S.W.A., covering the period between April 1953 and March 1954.112 Schoeman starts his paragraph on Game Reserve No. 2 with the introductory sentence ‘this area is also known as Etosha Pan Game Reserve’,113 apparently ignoring the fact that Kaokoveld was also officially part of the Game Reserve (see Figure 2.1), but illustrating the focus of the administration in the 1950s. The report provides further insights into developments during this time, including the diverging interests of the different branches of the administration, and its author’s opinion about lions (Panthera leo) and Haiǁom as well as game numbers in the reserve. Schoeman mentions in this report that one of the first challenges he had to address was the intended northwards shift of the Red Line to ‘deep in the Etosha pan’. He expressed the opinion that if the Red Line was moved according to plan,114 the actual bush area, which the wildlife needed for sheltered breeding time, as well as some of the best permanent waters between Okaukuejo and Namutoni, would be cut out from the game reserve. Schoeman noted that:

[i]t came down to the fact that a choice would have to be made between the interests of a number of farmers who would be able to get nice farms, and the preservation of the Etoshapan game reserve as something really worthwhile, because without such an ideal breeding place and good waters, the pan lost its “heart and womb”.115

Reportedly, the Administration decided in favour of the game’s future. After this decision, Schoeman started with development of the game reserve, establishing a rest camp at Okaukuejo (as decided in 1952), fire breaks, more boreholes, and so on.

In his report, Schoeman estimated that around 100 lions were living permanently in the Etosha Pan Game Reserve and noted with concern that lions were being poisoned on farms around Etosha. He hoped that with research and management the number of lions in Etosha might increase up to 1,000 in the next five years. He reckoned there was space for at least 3,000 lions in Etosha and stressed that they were essential for controlling the numbers of zebra (Equus quagga burchellii) (see Chapter 10) and wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus). Schoeman emphasised in the report that management (i.e. shooting/culling) was necessary to keep a balance between the difference species; otherwise zebra and wildebeest would dominate. In fact, Schoeman was ‘responsible for the controversial culling of large numbers of Burchell’s zebra and wildebeest in the Etosha area’ on the grounds that they were destroying vegetation.116 Remarkably, while not permitting Haiǁom to hunt, his recommendations included the suggestion to shoot zebra and wildebeest to feed the employed Bushmen and if necessary the lions too,117 a recommendation followed until at least the early 1960s. Read in the context of nature conservation developments at the time, his ideas suggest that the Etosha ecology increasingly had to be managed and “tamed”.

Under the subheading ‘Bushmen in the game reserve’, Schoeman considered that around 500 Haiǁom were living in the game reserve in 1953, a fact that was about to change. He further reported that:

they all have dogs, and continue hunting with poisoned arrows. Their favourite settlements are in the bush areas between Okaukuejo and Namutoni, around the game’s drinking places. [...] at one time or another in the past they were granted permission to hunt zebras and blue wildebeest, but after an investigation by the Police and Game Conservation it was found that their favourite game were eland, hartebeest [Alcelaphus buselaphus caama] and gemsbok [Oryx gazella]. And these species are far too rare in the game reserve to be exterminated by Bushmen.118

There seems a certain irony in Schoeman’s attitude towards lions on the one hand and Bushmen on the other. Lions were welcomed, due in part to their ability to control the number of game in the reserve, while Haiǁom were to be removed as ‘game exterminators’. Schoeman’s statement above can be certainly read as a justification for later decisions to evict Haiǁom from Etosha.

In 1953—the same year the Commission for the Preservation of Bushmen presented their recommendations with regard to the fate of Haiǁom residing in Etosha—the administration took the decision to expand and develop the game reserve as a sanctuary for game and for tourists.119 Shortly after, in 1954 the Haiǁom were evicted from the game reserve and had to choose to either move to Ovamboland or seek employment on the farms in the vicinity.120 A few were allowed to stay and found employment at the police stations and, later, the rest camps in the park, but they were no longer allowed to stay in their old settlements close to the waterholes (also see Chapters 4, 15 and 16). Schoeman’s 1953–54 annual report reads that,

[i]n 1953, Sergeant le Roux of Namutoni and Dr. Schoeman asked the administration to remove these idlers and game exterminators [the Haiǁom living in the reserve], from the game park—with the exception of the few who are employed by game conservation and the police […] It was immediately heard by the Administration, and in 1954, there were only a few groups left in the less accessible parts of the game reserve. However, there is a danger that some of the Bushmen who work on adjoining farms will from time to time run away to their hunting paradise, to hunt free again and cause wildfires. Wildlife conservation would greatly appreciate it if the necessary arrangements could be made by the Administration, in collaboration with the Police, to have such Bushmen arrested.121

A similar development took place regarding |Khomanin Damara/ǂNūkhoen in the Khomas Hochland west of Windhoek. They had been removed in various steps from the de-proclaimed native reserve Aukeigas (!Aoǁaexas) since the 1930s to create space for Daan Viljoen Game Reserve as a weekend resort for white citizens of Windhoek.122 Indicating a growing use of ideas about conservation and recreation to justify evictions, in the 1950s more |Khomanin were evicted from Aukeigas and relocated several hundred kilometres away to the farm Sorris-Sorris in today’s Kunene Region on the Ugab (!Uǂgab) River; purchased by the administration to enlarge the Okombahe Reserve.123 This was a significantly more marginal area in terms of rainfall and productivity, and many of the promises for state assistance remained unmet.124

The image of an “untamed wilderness”, highly appealing for tourists, henceforth excluded people, and the area around Etosha Pan was chosen to represent this image. Paradoxically, however, when employed for Kaokoveld this same idea seemed to include local inhabitants, namely ovaHimba.125 In Etosha as well as other areas, people and game apparently had to be separated for the sake of game preservation.

For Kaokoveld, the situation was more complicated, being at the same time part of Game Reserve No. 2 and a Native Reserve administered by the Department of Native Affairs.126 The problem caused by this ambiguous status became evident in a discussion that took place during the 1950s. A 1956 article published in the Sunday Times, Johannesburg, entitled ‘Slaughter of game in Africa’s Largest Reserve Alleged’, followed a museum expedition to game reserves in South Africa, in which Dennis Woods, member of the Western Province branch of the Wildlife Protection Society of South Africa, took part. In the article his concerns were quoted, firstly about miners and prospectors causing ‘indiscriminate killing of wild animals’ in Kaokoveld, and secondly, about the ‘6000 Natives with herds of cattle’ that were living in the northern part of Kaokoveld where most of the game could be found, ‘more than they could ever need or use’.127 Woods also wrote a letter to the Administrator of SWA with a copy of their report to the Chief Native Commissioner (Mr. Allen), saying that:

[i]t would seem to us that if South-West Africa is ever to have a National Park, Game Reserve No.2 in its entirety would be the ideal area, and it would be the one way of really safeguarding Kaokoveld for all time128 […] [t]he Kaokoveld Reserve is the best part of the only worth-while Game Reserve left in South-West Africa.129

The Chief Native Commissioner, in his reply, responded politely to the various concerns, stating:

I would ask you to remember that the Kaokoveld is in the first place a Native Reserve and it is the duty of our officials to protect the Native inhabitants against the depredations of lions and other carnivora. I can, however, assure you that these officials limit themselves to such protective measures and have no intention of undertaking any wholesale destruction of these animals.130

It becomes evident from this correspondence that: 1) the Kaokoveld was highly valued in terms of wildlife by some people; 2) the nature conservation lobby was becoming stronger; and 3) the status of Kaokoveld as both game reserve and native reserve became increasingly problematic for the administration—a situation to be solved during the 1960s (see Section 2.4 and Chapter 13).

In 1955, the Game Preservation Section was established, and biologist de la Bat became the Chief Game Warden equipped with a clerk and 28 workers. According to Amy Schoeman, this signified the end of the game protection era, and the beginning of ‘the holistic approach of conservation of Namibia’s natural assets’:131 although the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance of 1937 mentioned above suggests some prior moves towards a more holistic approach. Additionally, the SWA Publicity and Tourist Association was established in order to promote SWA as a tourist destination, resulting in an increasing number of tourists. Development in the fields of both conservation and tourism thus gained momentum.

Writing in this vein of an amplified conservation “movement”, in 1957, F. Gaerdes—a member of the Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Historical Monuments established in 1948—wrote an article for the SWA Annual entitled ‘Nature Preservation and the works of the Monuments Commission in SWA’. This article is revealing regarding the concept of nature conservation and its leadership by the “white man” in these years:

[t]he present is shaped by the past. Therefore we cherish the historical tradition embodied in the monuments which bear witness to our past. Primitive nature with her riches of plant and animal life forms part of this heritage. In many parts of the world it has of necessity had to yield to the demands of an expanding and increasing population. This process of cultivation, and the necessary impoverishment of wild life which it entails, cannot be halted, however much we may regret the loss of the irreplaceable. Not only scientists and naturalists […] have felt concern. The longing to experience nature where she still bears her original face, is alive in many people. Out of their need was born the concept of nature preservation which has gained increasing acceptance over the last 50 years. […] The nature preservation movement originated in Europe and North America, from there it spread to other continents. Primitive people are not concerned about nature preservation, and it was left to the white nations to spread the idea all over the globe. The initiative of European settlers created exemplary parks in many parts of Africa which are gaining a growing international reputation among scientists and nature lovers. [...] In South West Africa too, the idea is gaining ground that the preservation of nature is not merely a hobby-horse of utopian eccentrics, but a duty which the community owes to posterity.132

It seems a reversal of facts runs through this statement: “white nations”, i.e. mostly European traders, settlers and colonists, had been responsible for the large-scale decrease or extermination of game all over the world, including in SWA (see Chapter 1), but were now rhetorically enthroned as the champions of nature preservation.

While Gaerdes still talked about “preservation”, however, in this same year Chief Game Warden de la Bat recommended the change of name from game preservation or protection to game conservation. Following growing international usage, he considered the term conservation to be more comprehensive than preservation or protection, which only referred to the safeguarding of so-called “game” from human destruction. He suggested the Section of Game Preservation be renamed Section of Game Conservation, and that the change of name should also be applied in any new legislation.133 This suggestion was implemented shortly after. Already in 1954, the Parks Board had started operating although ‘without any proper legal status’,134 confining itself mainly to the recommendation on the game reserves, while the Game Preservation and Hunting Board attended to matters concerning game outside the reserve.135 Thus, the Game Preservation and Hunting Board and the Parks Board were operating alongside each other for four years before the merging of both institutions was formalised with Ordinance 18 of 1958 (Game Park and Private Game Reserves Ordinance), the first Annual Report of the Parks Board stating:

[p]rovision is also made for the fusion of the Game Preservation and Hunting Board with the Parks Board so that all matters concerning game may be dealt with by one board.136

The Parks Board included at least five members: ‘civil servants from agriculture, police, native affairs, the chief game warden and members of the farmers’ and hunting associations’.137 Its aims and functions were:

a) To advise the Administrator on the control, management and maintenance of game parks and private game reserves in South West Africa;

b) To investigate and report on all such matters concerning the preservation of game as the Administrator may refer to it;

c) To make such recommendations to the Administrator as it may deem fit regarding the preservation of game and any amendment to the game preservation laws of the Territory;

d) To meet in Windhoek at least once every year;

e) To perform and exercise such further functions, powers and duties as the Administrator may by regulation prescribe to the Board.138

Ordinance 18 of 1958 defined ‘Game Parks’ including ‘Etosha Game Park’; allowed for establishing Private Game Reserves; and provided for the official appointment of the Parks Board, defining its duties and members. The regulations for Game Parks (Section 5) were much more comprehensive than for Private Game Reserves. For example: entry and residence, the possession of firearms, and killing, injuring or disturbing animals in Game Parks, were not allowed without written permission; the introduction of animals and the chopping, cutting or damaging of trees were also prohibited. In Private Game Reserves, according to section 16(1), ‘no person, except the owner, may hunt any game or other wild animal or bird in any area which has been declared a private game reserve […] except under and in accordance with the written permission of the Administrator and on such conditions as he may impose in each case’.139 A major part of the ordinance focused on establishing the boundaries of Etosha Game Park around Etosha Pan, as a specific designation of Game Reserve No. 2 (see Figure 2.2 below, and discussion in Section 2.3.2). De la Bat reported that shortly after,

[w]e came to an agreement with the late Chief Kambonde to proclaim that part of the Andoni Plains which fell into his area, as his private game reserve. He saw to it that the wildebeest were undisturbed as long as he lived. Today [1982] there was none left and a border fence divides this vast plain which once teemed with game.140

In 1963, the Game Preservation Section was upgraded to the fully-fledged branch Nature Conservation and Tourism under the directorship of de la Bat141 who moved from Okaukuejo to Windhoek as the first director of the branch. The purpose of the branch was:

to extend activities in the field of nature conservation and to include, in addition to game parks, also fresh water fishing, public resorts, the protection of plants and trees, the development of nature reserves and regional services in connection with nature conservation.142

In this year, the staff of Etosha Game Park consisted of a Chief Game Ranger, ‘16 Europeans, two Coloureds, 9 Bantu and 31 Bushmen’,143 the classification and sequence of these categories reflecting the apartheid-era thinking of the time.

In 1965, a permanent research section under the Director of Nature Conservation and Tourism was established and Hym Ebedes became the first wildlife veterinarian (also due to the discovery of anthrax in Etosha in 1964), with Ken Tinley and Eugene Joubert appointed as ecologists.144 For the first time, the SWAA White Paper on the activities of the different branches of the Administration of South West Africa included a subsection on research, reporting inter alia about experiments with immobilisation drugs, the transfer of specific animals to or in-between game parks and studies in diseases and parasites.145 A direct census to determine the distribution of the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis bicornis) was carried out by Joubert in the western part of the game reserve. Joubert writes that,

[t]he study makes public disturbing information. The situation with regard to rhino is much more critical than was generally expected. The distribution of the black rhino, which used to occur throughout most of Suidwes, was now limited to the northwest corner. The total population of black rhino in 1966 were ninety animals. What was also disturbing, however, was the spread of these animals. Only 17 percent were within the amended limits of the Etosha National Park as suggested by the Odendaal Commission [see Section 2.4]. The other 83 percent were on private land or in communal or intended communal territories. It was clear that drastic steps were needed to ensure its survival.146

In 1967, the Nature Conservation Ordinance (31 of 1967) was proclaimed, providing a long-term policy consolidating former legislation and amended many times since its proclamation. It defined the powers and duties of the Nature Conservation and Tourism Branch and contained chapters on wild animals, game parks, indigenous plants, inland fisheries, protected and specially protected game, game birds and several other important subjects such as the issuing of licences, the establishment of a Nature Conservation Board (replacing the former Parks Board) and the repeal of laws.147 With the exception of protected species, the ordinance provided ownership of game to ‘owners or occupiers of a farm’ if the game was ‘lawfully upon such farm and while such farm is enclosed with a sufficient fence’.148 It thus permitted farmers to hunt on their farm throughout the year without a licence, except for protected game.149 It also allowed these farmers ‘with the written permission of the Administrator to lease his hunting rights to any competent person’.150 As Botha notes,

[this] rapidly led to the commercialisation of game hunting and farming in SWA and served as a spur to the embryonic tourist industry in the country. Trophy hunting became an increasingly lucrative enterprise and the number of game farms featuring game animals and the spectacular landscapes of the country multiplied. Many farmers, even those that did not contemplate converting their farms into private game reserves, bought game animals made available by the Department of Nature Conservation from stocks considered superfluous to the reserves.151

The exploitation of game as an economic resource became increasingly important for settlers, since cattle farming had turned out to be more challenging during the 1960s due to drought and the termination of the heavily state-supported settlement programme.152

By now, the concept of nature conservation had formally replaced the concept of game conservation,153 and the strong link with tourism was set in the formalisation of the Nature Conservation and Tourism Branch, still visible in Namibia’s current Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT).

2.3.2 Shifting borders, confusing spatial organisation and naming

The professionalisation of nature conservation, the growing significance of tourism, and the ideal of the people-and-parks divide were accompanied by shifting borders and an often-confusing spatial reorganisation during the 1950s and the 1960s. The Police Zone border was shifted ten times between 1947 and the early sixties, mainly to provide further farmland for white settlers, but also due to interests of the mining industry, tourism and veterinary concerns.154 Game Reserve No. 2 was changed significantly in size and shape and in 1958 a new legal entity, the Etosha Game Park, was created and extended (as noted in Section 2.3.1).

Ideas concerning a south-western extension of Game Reserve No. 2 emerged in the mid-1950s. The Chief Game Warden, de la Bat, reported in around 1957 that,

during 1956 the Parks Board of South West recommended that an additional nature reserve between the Hoab [ǁHuab] and the Hoanib rivers south of the Kaokoveld be created as a refuge for rhinos [...], mountain zebras [Equus zebra hartmannae] [...] and elephants [Loxodonta africana] and that it should be considered as an extension of the Etosha game park and that the Executive Committee has accepted these proposals and practical implications are currently being further investigated. The animals that are abundant in this area are relatively rare or absent in the Etosha Game Reserve.155

On 18 July 1956, the Executive Committee approved the following recommendations from a commission that had previously been asked to investigate damages caused by elephants, rhinos and giraffes on farms in the northern areas of SWA:

[t]he Commission feels satisfied that the natural shelter and protection offered to the elephants and the rhinos by the nature of the area between the present red line and the Native Area in the North and the Sea to the West is sufficient insurance for the survival of these giant animals of the jungle, provided the following steps are taken:-

i) this area must be declared a nature reserve and no one may be allowed to shoot anything there.156

ii) this area must be declared as an extension of the Etosha game park but especially with a view to the protection of elephants, rhinos and mountain zebra.157

The Surveyor General was shortly after supplied with the report of the commission and requested to furnish a point-to-point description of ‘the proposed new Nature Reserve’:158 in fact an extension of Game Reserve No. 2. He pointed out that there was a gap between the suggested new south-western portion and the old game reserve in the recommendation of the commission. He suggested:

[u]nless there are reasons which have not been disclosed I would like to suggest that the northern boundary of the new reserve be made to coincide with the southern boundary of Game Reserve No. 2. There will then be no big gap between the two.159

In doing so he was recommending that the Sesfontein Native Reserve should be included in Game Reserve No. 2. However, the Chief Native Commissioner and his department were not in favour of ‘any further portions of the Kaokoveld Native Reserve or the Sesfontein Native Reserve being included in the Game Reserve’.160

In 1958, the respective legislation was enacted. With Ordinance 18 of 1958, issued on 18 July, the south-eastern part of Game Reserve No. 2 was designated as Etosha Game Park with Kaokoveld remaining as both part of Game Reserve No. 2 and the Kaokoland Native Reserve—as established in 1947. Ordinance 18 reads:

2. The area defined in the first schedule to this Ordinance and known as game reserve No. 2, but excluding that portion which falls within a Native Reserve [i.e. the Kaokoland Reserve of 1947], is hereby declared a game park, to be known as the Etosha Game Park, for the propagation, protection and preservation therein of wild animal life, wild vegetation and objects of geological, ethnological, historical or other scientific interest for the benefit, advantage and enjoyment of the Inhabitants of the Territory.161

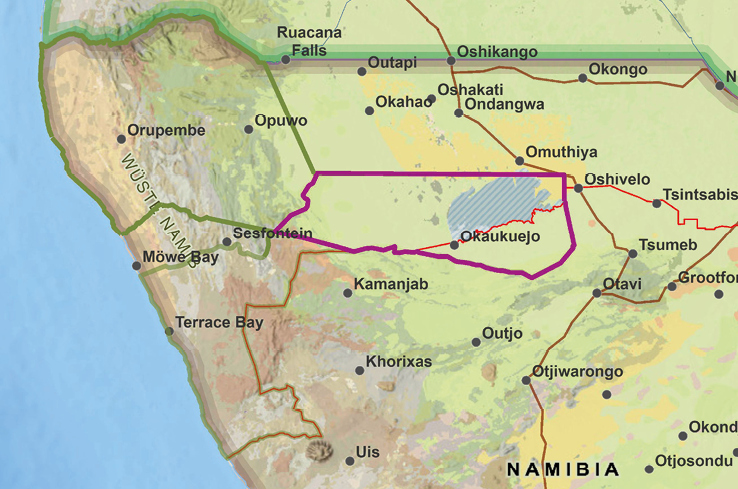

The boundaries of Etosha Game Park as defined in this ‘first schedule’ are marked in purple in Figure 2.2.

Soon afterwards (3 September 1958) in Government Notice 247 of 1958,162 the Administrator redefined the boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2, which thereby became extended for 250 km south of the Hoanib River to the Ugab (!Uǂgāb) River along the Red Line. It is important to note that this area had been iteratively emptied of former inhabitants—for example, through a north-west expansion of the commercial farming area in the 1950s (see Chapters 12 and 13). At least until the 1990s, however, people concentrated in the Hoanib valley villages would return to areas south of the Hoanib to collect foods such as sâun and bosûi (Stipagrostis spp. grass seeds and Monsonia umbellata seeds gathered from harvester ant nests) and honey. Elderly inhabitants of Hoanib valley settlements have detailed memories of dwelling places, springs and graves throughout this area.163 In this game reserve expansion, the Kaokoland and Sesfontein Native Reserves were retained where thousands of people were living (see Figure 2.2). During this time, there was neither infrastructure nor nature conservation personnel in the south-western portion of Game Reserve No. 2 to implement this redefinition: it is likely that local people had no idea about these boundaries and designations, a situation that echoes today in new boundary-making activities for conservation (see Chapter 3). In retrospect, de la Bat commented on the south-western extension of the reserve:

[i]n the course of time it became clear that Etosha [Game Park] was not big enough to accommodate rare and threatened species such as black rhino, mountain zebra and black-faced impala, migratory big game like eland and elephant and the influx of wildlife from adjacent areas where it was being harassed. In 1958, the Parks Board under the chairmanship of Simmie Frank made a calculated move. We agreed to the deproclamation of Game Reserve No. 1, north-east of Grootfontein, provided that the unoccupied state land between the Hoanib and Uchab Rivers to be added to Etosha. In doing so, we exchanged valuable farming land for a mountainous and desert area but we practically doubled the size of Etosha, safeguarded game migration routes and obtained a corridor to the sea. The new park extended from the Skeleton Coast to the Etosha Pan, nearly 500 kilometres inland.164

Fig. 2.2 Map of Etosha Game Park (purple contour) and Game Reserve No. 2 (green contour) in 1958, with the ‘red line’ of 1955 (red) and main roads (brown lines). Note that the southern boundary of Game Reserve No. 2 (in green) overlaps with the veterinary control boundary in red. © Ute Dieckmann; data: Ordinance 18 of 1958; Government Notice 247 of 1958; Atlas of Namibia Team 2022, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

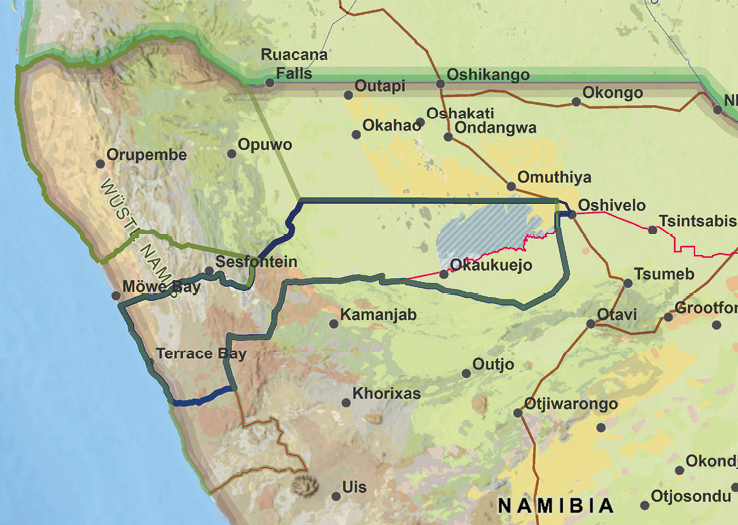

In 1962, with Government Notice 177, Etosha Game Park was itself extended across part of the 1958 south-west extension of Game Reserve No. 2 (Figure 2.3):

to a point where the western boundary line of the last mentioned farm [Werêldsend] intersects the southern side of the road from Welwitschia [Khorixas] to Torrabaai; thence westwards along the southern side of the road to Torrabaai [close to the Koigab river] to the low-water mark of the Atlantic Ocean.165

Fig. 2.3 Map of Etosha Game Park in 1962 (blue contour) and Game Reserve No. 2 in 1958 (green contour) (for which Government Notice 20 of 1966 retains the 1958 boundary); with the ‘red line’ in 1955 (red) and main roads (brown lines). Again, the southern boundary of Game Reserve No. 2 (in green) overlaps with the veterinary control boundary (in red). © Ute Dieckmann; data: Ordinance 18 of 1958; Government Notice 177 of 1962; Atlas of Namibia Team 2022, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

With this change, tourist spots along the coast were included in Etosha Game Park. The SWAA White Paper on the Activities of the Different Branches of the Administration of South West Africa for the Financial Year 1962–1963 notes:

[t]he Etosha Game Park’s boundaries were extended during the year up to the sea coast by the proclamation of part of the Game Reserve 2 as a game park. The popular fishing and holiday resort at Unjab [!Uniab] mouth [presumably Torra Bay] now falls within the game park.166

Torra Bay (south of !Uniab mouth) came under the direct supervision of the newly established branch of Nature Conservation and Tourism, yet changes to come impeded the development of the resort:

it was now decided first to determine the resort’s future popularity, as all the farms in that vicinity (from which most of the visitors always come) are now being bought up as a result of the implementation of the recommendations of the Odendaal Commission, and Torra Bay will eventually be cut off from the rest of the game reserve by a Bantu area.167

As alluded to in this quote, the extension of Etosha Game Park up to the coast was very short-lived as new plans entered the stage during this same year (as clarified in Section 2.4).

Further east, the Red Line south of Etosha Pan was shifted through Government Notice 222 of 1961, moving it southwards from along Etosha Pan to the border of Etosha Game Park and the settler farms.168 Here, the reality of the Red Line on maps gradually became reality on the ground in the form of fences which impeded the mobility of both animals and people in and out of Etosha Game Park.169 The game-proof fence along the southern boundary of Etosha Game Park had been gradually erected during the 1950s reached up to Otjovasandu in the west in 1963,170 although it needed continual repairs due to damage by wildlife, mainly elephants.171

Government Notice 20 of 1966 entitled ‘Prohibited Areas Proclamation 1928: Redefinition of the Boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2’172 delineated a coastal strip of around 20 miles to the west of the Sesfontein and Kaokoveld Native Reserve areas (Figure 2.4). Although the stated boundaries do not in fact include this coastal strip within Game Reserve No. 2 it appears that this was the intention, as indicated in a map published by Giorgio Miescher’s for 1966.173 The stretch of land around Sesfontein, which had been excluded from the Game Reserve in the 1958 definitions, thereby became an island surrounded by the Game Reserve, followed soon after by proclamation of the Skeleton Coast National Park (SCNP) in 1971. This new boundary further consolidated the already restricted local access to the Northern Namib, where diamond prospecting and mining had been taking place since at least the 1950s174 (see Chapter 12).

Fig. 2.4 Map of Game Reserve No. 2 in 1966 (green contour) showing the excluded ‘native reserve’ area around Sesfontein (brown contour), the ‘red line’ of 1955 (red) and main roads (brown lines). © Ute Dieckmann; data: Ordinance 18 of 1958, Government Notice 20 of 1966; Atlas of Namibia Team 2022, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

With Nature Conservation Ordinance 31 of 1967, Etosha Game Park became Etosha National Park,175 initially retaining the 1962 boundaries of Etosha Game Park (see Figure 2.3) and adding a small corner of land in the north-east (see Figure 2.6 in Section 2.4.1). Chapter 3 of Ordinance 31 of 1967 iterates Ordinance 18 of 1958, with some adjustments:

[t]he area defined in schedule 7 to this ordinance and known as the Etosha Game Park is hereby declared to be a game park to be known as the Etosha National Park for the propagation, protection and preservation therein of wild animal life, wild vegetation and objects of geological, ethnological, historical or other scientific interest and for the benefit and enjoyment of the inhabitants of the Territory: Provided that it shall be in the Administrator’s sole and final discretion to determine whether and when prospecting or mining activities are in the national interest.176

Evidently, the socio-ecological organisation of space was in constant flux during these years. The established entity of Game Reserve No. 2 was retained but transformed in size and shape, and new entities were created—Etosha Pan Game Reserve becoming Etosha Game Park, then extended to the south-west, then becoming Etosha National Park. There was little time, however, to implement these new legal entities with infrastructure, personnel and boundaries. They remained ideas in the minds of responsible administrative representatives, written down in Government Notices, and at times put on maps. This also explains why several published maps diverge from one another in the delineation of these entities.177 In any case, the 1967 boundaries of Etosha National Park were also short-lived, as explained in Section 2.4.